Abstract

Small arteries in the body control vascular resistance, and therefore blood pressure and blood flow. Endothelial and smooth muscle cells in the arterial walls respond to various stimuli by altering the vascular resistance on a moment to moment basis. Smooth muscle cells can directly influence arterial diameter by contracting or relaxing, whereas endothelial cells that line the inner walls of the arteries modulate the contractile state of surrounding smooth muscle cells. Cytosolic calcium is a key driver of endothelial and smooth muscle cell functions. Cytosolic calcium can be increased either by calcium release from intracellular stores through IP3 or ryanodine receptors, or the influx of extracellular calcium through ion channels at the cell membrane. Depending on the cell type, spatial localization, source of a calcium signal, and the calcium-sensitive target activated, a particular calcium signal can dilate or constrict the arteries. Calcium signals in the vasculature can be classified into several types based on their source, kinetics, and spatial and temporal properties. The calcium signaling mechanisms in smooth muscle and endothelial cells have been extensively studied in the native or freshly isolated cells, therefore, this review is limited to the discussions of studies in native or freshly isolated cells.

INTRODUCTION.

Intracellular concentration of free calcium (Ca2+) plays a major role in controlling several physiological processes including gene expression, hormone secretion, cell proliferation, and muscle contraction (Berridge, Bootman, & Roderick, 2003). The cytosolic Ca2+ is maintained at a low level (~100–300 nM) by numerous Ca2+ binding proteins and Ca2+ pumping ATPases. Cytosolic Ca2+ can increase via the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores or the influx of extracellular Ca2+ through ion channels at the cell membrane. While some Ca2+ signals result in a sustained, uniform increase in whole-cell Ca2+ levels, other Ca2+ signals occur transiently and are spatially restricted or localized. Recent studies support the concept that the majority of physiological increases in cytosolic Ca2+ in the vasculature are localized to functionally important microdomains. Such signal localization not only serves to limit cellular toxicity of Ca2+, but also maintains the specificity of the downstream Ca2+-sensitive target. Spatial localization of Ca2+ signals is made possible by clustering of Ca2+ channels at important microdomains in the cell membrane. Moreover, numerous Ca2+ binding proteins and a high viscosity of the cytosol limit the diffusion of Ca2+, further contributing to signal localization.

Vascular resistance is a major controller of blood pressure and blood flow. Contractile state of small-sized arteries determines their diameter, and therefore vascular resistance to blood flow. Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and endothelial cells (ECs) are the two major cell types in the arterial wall that are known to influence vascular resistance. VSMCs can contract or relax, resulting in vasoconstriction or vasodilation, respectively. ECs line the inner walls of all arteries, and can modulate the contractile state of the surrounding VSMCs. Traditionally, increases in VSMC Ca2+ have been associated with vasoconstriction, whereas increases in endothelial Ca2+ are thought to be vasodilatory. However, some highly localized Ca2+ signals in VSMCs can couple with vasodilator effector pathways and lower vascular resistance.

HOW ARE CALCIUM SIGNALS MEASURED?

Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dyes are the most commonly used tools for studies of intracellular Ca2+. The fluorescence properties of Ca2+ dyes change when they are bound to Ca2+, thus enabling detection of intracellular Ca2+ levels. Fluorescent dyes are commonly used as membrane-permeable acetoxymethyl (AM) esters, which are cell-permeable. Intracellular esterases release the membrane-impermeable anion form of the dye that is retained within the cell. Most fluorescent dyes are derivatives of the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA (bis-[o-amino-phenoxy]-ethane-N,N,N′N′-tetraacetic acid) (Tsien, 1980). Fluorescent dyes can be ratiometric or non-ratiometric. Ratiometric dyes show a shift in excitation (fura-2) or emission (indole-1) wavelength that is dependent on the concentration of free Ca2+. Non-ratiometric dyes (fluo family) show an increase in fluorescence intensity on binding Ca2+ and are useful for qualitative changes in Ca2+. Ratiometric dyes are generally used for estimating Ca2+ concentration, but methods have been developed to calculate Ca2+ concentration using single wavelength fluorescence signals with non-ratiometric dyes (Maravall, Mainen, Sabatini, & Svoboda, 2000). Ratiometric dyes have the advantage that the ratio normalizes the variations in fluorescence with uneven dye loading, distribution, dye leakage, or photobleaching. However, the dyes require excitation in the ultraviolet range, and cannot record individual Ca2+ signals that drive many physiological functions. Non-ratiometric dyes enable the recordings of localized Ca2+ signals. However, an accurate analysis of kinetic and spatial properties of fast Ca2+ signals may require the use of high-speed Ca2+ imaging. Indeed, high-speed Ca2+ imaging has enabled detailed studies of kinetic and spatial properties of several Ca2+ signals, including rise time, duration, spatial spread, amplitudes of elementary signals, and functional coupling between neighboring signals (Ledoux, Taylor, et al., 2008; Navedo, Amberg, Votaw, & Santana, 2005; Navedo et al., 2010; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2015).

CALCIUM SIGNALS IN VSMCs.

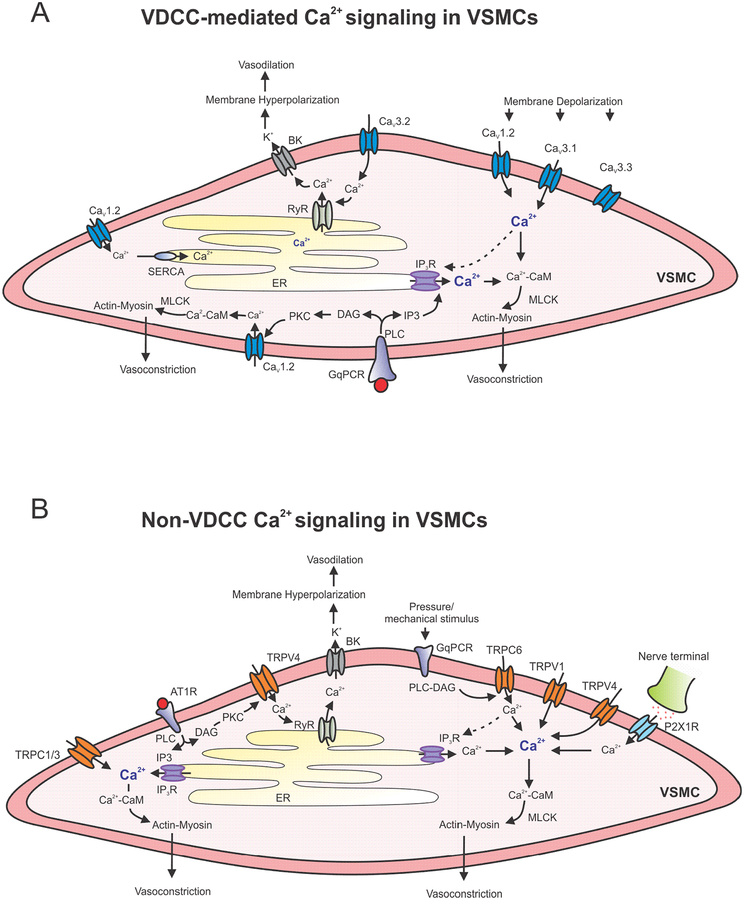

VSMCs are excitable cells that have the ability to contract in response to changes in membrane potential. Several physiological stimuli, including intravascular pressure, Gq protein coupled receptor (GqPCR) signaling, and sympathetic neurotransmitters, can contract VSMCs and increase vascular resistance. Small, resistance arteries in the body can constrict in response to intravascular pressure (Bayliss, 1902). This phenomenon, called myogenic vasoconstriction, is extremely important for the regulation of vascular resistance. VSMC Ca2+ not only plays a critical role in the development of myogenic vasoconstriction, but also contributes to vasoconstriction in response to neurohumoral mediators and other mechanical stimuli. The resting membrane potential in VSMCs is in the range of −45 mV (Dietrich et al., 2005; Knot & Nelson, 1995, 1998; Welsh & Segal, 1998). Intravascular pressure depolarizes VSMC membrane and activates voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCCs) on the membrane, resulting in Ca2+ influx through these channels (M. J. Davis & Hill, 1999). A membrane depolarization of ~ 10 mV was associated with approximately 30% constriction in cerebral arteries (Knot & Nelson, 1998). Vasoconstriction is caused by Ca2+-calmodulin (CaM) dependent activation of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) and actin-myosin cross bridge formation in VSMCs (Somlyo & Somlyo, 2003). Individual Ca2+ signals can occupy whole VSMCs, or occur in a spatially localized manner. While global or large Ca2+ signals contribute to vasoconstriction, localized Ca2+ signals couple with Ca2+-activated K+ channels and can cause vasodilation (Navedo et al., 2005; Nelson et al., 1995). Ca2+ signals in VSMCs can be divided into several classes depending on their source- inositol triphosphate receptors (IP3Rs), ryanodine receptors (RyRs), VDCCs, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, receptor-operated Ca2+ channels, store-operated Ca2+ channels, and purinergic P2X1 receptors (Figure 1). Individual Ca2+ signals in VSMCs have been variously described as sparks, sparklets, waves, or junctional transients (Table 1) depending on their spatial and kinetic properties. Thus, the changes in VSMC Ca2+ can be global or highly localized, sustained or transient, stationary or moving, or repetitive.

Figure 1. Ca2+ signaling networks in VSMCs.

A. Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel (VDCC)-mediated signaling mechanisms that regulate VSMC (vascular smooth muscle cell) contractility. Ca2+ influx through CaV1.2, CaV3.1, and CaV3.3 channels, and Ca2+ release through IP3Rs contribute to vasoconstriction. Gq protein coupled receptor (GqPCR) signaling increases Ca2+ levels via activation of IP3 receptors (IP3Rs) and CaV1.2 channels. Ca2+ influx through CaV3.2 channels couples with ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels to cause membrane hyperpolarization and vasodilation. B. Non-VDCC Ca2+ influx pathways in VSMCs include TRPC (transient receptor potential canonical) and TRPV (transient receptor potential vanilloid) channels. Ca2+ influx through VSMC TRP channel has mostly been associated with vasoconstriction. Localized Ca2+ influx through TRPV4 channels can activate RyR-BK channel signaling and contribute to vasodilation. Increase in cytosolic Ca2+ mediated by VDCCs and TRP channels is amplified by Ca2+ release through IP3 receptors (IP3Rs). ER: endoplasmic reticulum; SERCA: sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase; CaM: Calmodulin; IP3: Inositol triphospate; GqPCR: Gq protein-coupled receptor; RyR: ryanodine receptor; MLCK: myosin light-chain kinase; PLC: phospholipase C; PKC: protein kinase C; DAG: diacylglycerol; AT1R: angiotensin II receptor 1; P2X1R: purinergic receptor P2X1.

Table. 1.

Local Ca2+ signals in VSMCs.

| Ca2+ signal | Source | Functional effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ca2+ sparklets | Unitary Ca2+ influx signals through single VDCCs |

|

(Amberg et al., 2007; Navedo et al., 2006; Nieves-Cintron et al., 2008; Santana & Navedo, 2009; Takeda et al., 2011) |

| TRPV4 sparklets | Unitary Ca2+ influx signals through TRPV4 channel | Increased RyR-BK channel signaling that limits vasoconstriction | (Mercado et al., 2014; Tajada et al., 2017) |

| Ca2+ sparks | Unitary Ca2+ release signals through RyRs | Activation of BK channels on the VSMC membrane, membrane hyperpolarization, vasodilation | (Hogg et al., 1993; Knot, Standen, & Nelson, 1998; Nelson et al., 1995; Perez, Bonev, Patlak, & Nelson, 1999) |

| Ca2+ waves | Propagating Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release signals through IP3Rs | Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent excitation-contraction coupling, vasoconstriction | (Boittin et al., 1999; Grayson et al., 2004; Jaggar & Nelson, 2000; Miriel et al., 1999) |

| jCaTs | Ca2+ influx through P2X1Rs at nerve varicosities | Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent excitation contraction coupling, vasoconstriction | (Lamont et al., 2003; Lamont et al., 2006; Lamont & Wier, 2002) |

Release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores in VSMCs.

Ca2+ can be delivered from sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) into the cytosol via opening of IP3Rs or RyRs, two channels with distinct regulatory properties and functional effects. Cytosolic Ca2+ is transported to the SR by SR/endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ ATPases (SERCA). Under resting conditions, phospholamban inhibits the activity of SERCA (Simmerman & Jones, 1998). Phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase G (PKG) relieves the phospholamban inhibition of SERCA, thus increasing Ca2+ uptake by the SR (Simmerman & Jones, 1998). The concentration of free Ca2+ inside the SR is maintained at low levels by Ca2+ binding proteins, which retain Ca2+ inside the SR and allow continued uptake of Ca2+ by the SR (Pozzan, Rizzuto, Volpe, & Meldolesi, 1994).

A. IP3R

Three IP3R isoforms (IP3R1–3) are expressed at varying degrees in different VSMCs (Grayson, Haddock, Murray, Wojcikiewicz, & Hill, 2004; Tasker, Michelangeli, & Nixon, 1999). IP3Rs are homo- or heteromeric complexes consisting of four subunits, each with six transmembrane segments. Each segment has a large cytosolic N-terminal with an IP3 binding site, and a short cytosolic C-terminal. The channel pore is lined by transmembrane segments 5 and 6 of each subunit (Foskett, White, Cheung, & Mak, 2007). Ca2+ release by IP3Rs is controlled mainly by two second messenger ligands: IP3 and Ca2+. Activation of GqPCRs is the canonical signaling pathway that stimulates phospholipase C (PLC), which hydrolyses membrane associated phosphoinositide 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into IP3 and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 can then bind to IP3R and release Ca2+ into the cytosol. Many neurohumoral vasoconstrictors, including norepinephrine, angiotensin II (Ang II), and endothelin-1 activate their respective GqPCRs on VSMC membranes (Figure 1).

The IP3R is fundamentally a Ca2+-activated ion channel. The primary functional effect of IP3 is to relieve Ca2+ inhibition of the channel, enabling Ca2+ activation sites to open the channel. IP3Rs have several distinct Ca2+ binding sites that regulate channel activation or inhibition. As Ca2+ rises from nanomolar to micromolar levels close to the channel, the channel is activated. At higher Ca2+ levels, IP3R is inactivated. This variety of activation and inactivation patterns in combination with multiple interacting regulatory factors allow IP3Rs to generate spatially and temporally distinct Ca2+ signals (Foskett et al., 2007). At low IP3 levels, few receptors are liganded by IP3, resulting in openings of a few IP3R channels and a localized Ca2+ signal that has been labelled as a “blip”. At higher levels of IP3, more IP3Rs in a cluster are liganded and the flux of Ca2+ through these IP3Rs results in Ca2+-dependent activation of nearby IP3Rs in the cluster (Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release), resulting in a larger signal that is called a “puff”. Even higher levels of IP3 evoke propagating Ca2+ signals called waves, whereby Ca2+ released at one cluster can trigger Ca2+ release from adjacent cluster via Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. Ca2+ waves can propagate across entire VSMCs (Table 1), and are commonly seen in VSMCs exposed to vasoconstrictor GqPCR agonists including UTP and norepinephrine, and nerve-stimulation (Boittin, Macrez, Halet, & Mironneau, 1999; Jaggar & Nelson, 2000; Miriel, Mauban, Blaustein, & Wier, 1999; Ruehlmann, Lee, Poburko, & van Breemen, 2000). A continuous cycling of Ca2+ release and uptake by the SR may be sufficient to maintain Ca2+ waves (Foskett et al., 2007). Although IP3Rs are the major contributors to VSMC Ca2+ waves, RyRs have also been shown to generate Ca2+ waves in VSMCs under certain conditions (Boittin et al., 1999; Heppner, Bonev, Santana, & Nelson, 2002; Jaggar & Nelson, 2000). Ca2+ inhibition of IP3Rs has been reported for IP3R1 (Mak, McBride, & Foskett, 1998) and IP3R3 (Bezprozvanny, Watras, & Ehrlich, 1991; Mak, McBride, & Foskett, 2001). Ca2+ inhibition of IP3Rs occurs at Ca2+ concentrations in the micromolar range. While Ca2+ inhibition of IP3R1 is generally agreed, some studies have suggested that IP3R2 and IP3R3 are not inactivated by high Ca2+ (Hagar, Burgstahler, Nathanson, & Ehrlich, 1998; Ramos-Franco, Fill, & Mignery, 1998).

B. RyR

Three types of RyRs (RyR1–3) are expressed in different VSMCs at different levels (Neylon, Richards, Larsen, Agrotis, & Bobik, 1995; X. R. Yang et al., 2005). RyRs are tetrameric complexes consisting of four subunits, each with four transmembrane segments. Each of the subunits has a long cytosolic N- terminal that contains Ca2+ binding site and binding sites for several regulatory proteins, and a short C-terminal in the SR (Lanner, Georgiou, Joshi, & Hamilton, 2010; Zalk, Lehnart, & Marks, 2007).

The flux of Ca2+ through RyRs can be detected as transient, stationary Ca2+ release signals called Ca2+ sparks, which likely reflect the opening of four to six RyR channels in the SR membrane (Cheng & Lederer, 2008). RyR-induced Ca2+ sparks were first discovered in cardiac muscle (Cheng, Lederer, & Cannell, 1993), and later identified in skeletal (Klein et al., 1996) and smooth muscle (Nelson et al., 1995). Ca2+ sparks have been detected in isolated VSMCs as well as in pressurized arteries from several vascular beds. Ca2+ sparks in VSMCs exhibit a duration of 50–60 ms, rise time of 20–40 ms, and a spatial spread of ~ 13 μm2 (Nelson et al., 1995). Current evidence supports RyR2 as the major RyR responsible for Ca2+ sparks in VSMCs (Vaithianathan et al., 2010). Ca2+ sparks activate nearby Ca2+-activated, large conductance K+ (BK) channels in VSMC membrane to hyperpolarize the membrane by ~ 10 mV, deactivate VDCCs, and dilate the arteries (Jaggar et al., 1998) (Figure 1, Table 1). Ca2+ sparks can occur spontaneously and activate BK currents, known as spontaneous transient outward currents (STOC). Ca2+ sparks can also activate Ca2+ activated chloride channels (CaCl) to produce spontaneous transient inward currents (STICs) (Hogg, Wang, Helliwell, & Large, 1993). If Ca2+ sparks couple with BK channels and CaCl channels, spontaneous transient outward/inward currents (STOIC) can be seen (Hogg et al., 1993; ZhuGe, Sims, Tuft, Fogarty, & Walsh, 1998). While Ca2+ sparks have mostly been shown to be vasodilatory, Krishnamoorthy et al. indicated that RyRs in VSMCs can contribute to global increase in Ca2+ and nerve stimulation-induced constriction (Krishnamoorthy, Sonkusare, Heppner, & Nelson, 2014). Rapid addition of RyR activator caffeine can also cause global Ca2+ transients and vasoconstriction (Wellman & Nelson, 2003). Stimuli that increase SR Ca2+ load also increase the frequency of Ca2+ sparks. In VSMCs, Ca2+ currents through VDCCs activate RyRs indirectly via global increases in Ca2+ and SR Ca2+ load (Collier, Ji, Wang, & Kotlikoff, 2000; Essin & Gollasch, 2009; Essin et al., 2007; Harraz, Abd El-Rahman, et al., 2014; Harraz, Brett, et al., 2015).

Ca2+ influx through VDCC (CaV) in VSMCs.

VDCCs are required for normal excitation–contraction coupling in the heart, skeletal muscle, and various types of SMCs. Membrane depolarization-induced opening of VDCCs is an important mechanism for myogenic vasoconstriction in resistance arteries. The pressure-induced membrane depolarization is thought to be primarily caused by TRP channel activation (Earley & Brayden, 2015) and a GqPCR-dependent mechanism (Kauffenstein, Laher, Matrougui, Guerineau, & Henrion, 2012; Schleifenbaum et al., 2014). The main VDCCs known to be implicated in VSMC contraction are long lasting or L-type, and transient or T-type Ca2+ channels. Whereas L-type Ca2+ channels are high voltage activated channels due to their activation at more depolarized voltages, T-type Ca2+ channels are low voltage activated due to their activation at more hyperpolarized voltages (Catterall, 2011; Harraz & Welsh, 2013b). The relative abundance of L-type or T-type channels varies along the vascular tree. While L-type and T-type Ca2+ channels appear to be expressed to a similar extent in the aorta, the expression of T-type channels is higher than L-type channels in mesenteric arterioles (Ball, Wilson, Turner, Saint, & Beltrame, 2009; Jensen & Holstein-Rathlou, 2009). In terminal mesenteric arterioles, mRNA for T-type channels was detected, whereas L-type Ca2+ channels mRNA was undetectable (Gustafsson, Andreasen, Salomonsson, Jensen, & Holstein-Rathlou, 2001). Similarly, T-type channel expression predominates in cerebral artery VSMCs, although L-type channels are also expressed (Abd El-Rahman et al., 2013).

A. L-type Ca2+ channels.

L-type Ca2+ channels of the CaV1.2 gene family are the primary pathways for voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx in VSMCs that triggers excitation-contraction coupling (Knot & Nelson, 1998; Liao et al., 2007; Nelson, Patlak, Worley, & Standen, 1990; S. Sonkusare, Fraer, Marsh, & Rusch, 2006; S. Sonkusare, Palade, et al., 2006). CaV1.2 channels are heteromultimeric structures that are composed of a pore-forming α1C subunit and regulatory β, α2δ, and γ subunits in VSMCs. While the α1 subunit determines the signature channel properties (voltage sensing, Ca2+ permeability, Ca2+-dependent inactivation, and inhibition by Ca2+ channel blockers), accessory β, α2δ, and γ subunits modulate their expression at the surface, biophysical properties, and physiological responses (Bannister et al., 2009; S. Sonkusare, Fraer, et al., 2006; S. Sonkusare, Palade, et al., 2006). The structure of α1 subunit includes four repeat domains (I-IV) each with six transmembrane segments. The domains are linked by intracellular loops that are subject to splicing and modulation by PKA and protein kinase C (PKC), which can then phosphorylate the channel. The intracellular N- and C-termini are responsible for conferring key properties including Ca2+-dependent inactivation of the channel. While β subunits are intracellular and linked to the I-II loop, γ subunits are transmembrane and α2δ subunits are described as type-I transmembrane proteins (extracellular α2 attached to transmebrane δ by a disulfide linkage) (A. Davies et al., 2010; De Jongh, Warner, & Catterall, 1990). Additionally, C-terminal is susceptible to proteolytic cleavage, and the resulting C-terminal fragment has been shown to lower channel expression and voltage sensitivity (Bannister et al., 2013).

The single channel conductance of CaV1.2 channels is ~ 25 pS with Ba2+ as a charge carrier (Church & Stanley, 1996). At least several thousand pore-forming channel subunits are expressed per cell (Nelson et al., 1990). During a sustained depolarization, CaV1.2 channels inactivate slowly, allowing a small number of channels to mediate voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx and vasoconstriction (Goligorsky, Colflesh, Gordienko, & Moore, 1995; Inscho, Cook, Mui, & Imig, 1998; Nelson et al., 1990). CaV1.2 channels not only maintain a tonic level of constriction, but also provide a mechanism for endogenous vasoactive mediators to act on and modulate arterial diameter (Catterall, 2011; Dolphin, 1998; S. Sonkusare, Palade, et al., 2006) (Figure 1A). Indeed, mice with inactivated CaV1.2 gene show reduced myogenic vasoconstriction and lower blood pressure, supporting vital roles for CaV1.2 channels in VSMCs(Moosmang et al., 2003). On the other hand, an upregulation of vascular CaV1.2 channels has been linked with excessive vasoconstriction and hypertension (Hirenallur et al., 2008; Kharade et al., 2013; Navedo et al., 2010; Navedo et al., 2008; Pesic, Madden, Pesic, & Rusch, 2004; Pratt, Bonnet, Ludwig, Bonnet, & Rusch, 2002). VSMC membranes are depolarized in various models of hypertension, and membrane depolarization not only activates L-type VDCCs, but sustained depolarization can also upregulate L-type VDCC expression, which aggravates hypertension (Pesic et al., 2004; S. Sonkusare, Fraer, et al., 2006; S. Sonkusare, Palade, et al., 2006).

Ca2+ signals caused by the influx of Ca2+ through individual L-type Ca2+ channels, termed Ca2+ sparklets, were first recorded in the cardiac muscle (S. Q. Wang, Song, Lakatta, & Cheng, 2001). Ca2+ sparklets in VSMCs have been detected using TIRF (total internal reflection fluorescence) microscopy (Amberg, Navedo, Nieves-Cintron, Molkentin, & Santana, 2007; Navedo, Amberg, Nieves, Molkentin, & Santana, 2006; Nieves-Cintron, Amberg, Navedo, Molkentin, & Santana, 2008; Santana & Navedo, 2009; Takeda, Nystoriak, Nieves-Cintron, Santana, & Navedo, 2011). Ca2+ sparklets are stationary signals, with the average area of ~ 0.8 μm2, and occur in specific regions of the plasma membrane (Table 1). Ca2+ sparklets are quantal signals, and the amplitude of a signal depends on the number of simultaneously activated channels. While some sites show a low activity, other sites show high activity that has been attributed to activation of L-type VDCCs by PKC (Santana et al., 2008).

B. T-type Ca2+ channels.

There is increasing evidence that VSMC T-type Ca2+ channels regulate myogenic vasoconstriction, particularly in small cerebral arteries. T-type Ca2+ channels are composed of a single pore-forming α1 subunit, and there are no known regulatory subunits of the channel (Catterall, 2011). Recent studies support the presence of three T-type Ca2+ channels in rodent VSMCs (CaV3.1, CaV3.2, CaV3.3) at the level of mRNA, protein, and functional channel (Bjorling et al., 2013; Harraz, Brett, et al., 2015; Harraz, Visser, et al., 2015; Mikkelsen, Bjorling, & Jensen, 2016). CaV3.1 and CaV3.3 channels contributed to myogenic vasoconstriction in rodent (Bjorling et al., 2013) and human cerebral arteries (Harraz, Visser, et al., 2015). On the contrary, CaV3.2 channels were shown to limit myogenic vasoconstriction in mesenteric and cerebral arteries (Harraz, Brett, et al., 2015; Mikkelsen et al., 2016). CaV3.2 channels localized with RyRs, and sustained depolarization activated vasodilatory CaV3.2-RyR-BK channel signaling, thus opposing myogenic constriction (Harraz, Visser, et al., 2015) (Figure 1A). CaV3.2 channels are located inside the caveolae to provide spatially restricted coupling with RyRs (Harraz, Abd El-Rahman, et al., 2014; Harraz, Brett, et al., 2015). Similar to CaV1.2 channels, T-type Ca2+ channels in VSMCs are also modulated by several physiological modulators including nitric oxide (NO) (Harraz, Brett, & Welsh, 2014), PKA (Harraz & Welsh, 2013a), and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Hashad, Sancho, Brett, & Welsh, 2018).

Ca2+ influx through TRP channels in VSMCs.

In the past two decades, TRP channels have emerged as important regulators of arterial diameter. Almost all the TRP channels are permeable to Ca2+, and many TRP channels influence Ca2+ signaling pathways that drive cellular functions (Clapham, Runnels, & Strubing, 2001). TRP channels present in perivascular sensory nerves and astrocytes are also known to participate in vasodilator responses (Bautista et al., 2005; Dunn, Hill-Eubanks, Liedtke, & Nelson, 2013; Sudhahar, Shaw, & Imig, 2009; L. H. Wang, Luo, Wang, Galligan, & Wang, 2006; Zygmunt et al., 1999). TRP channels have been described as direct Ca2+ influx pathways, receptor operated Ca2+ influx pathways, and store operated Ca2+ influx pathways, although the latter property is disputed in native vascular cells.

Mammalian TRP channels have been divided into six subfamilies based on their amino acid sequence homology- canonical (TRPC), vanilloid (TRPV), melastatin (TRPM), ankyrin (TRPA), mucolipin (TRPML), and polycystin (TRPP). Transcriptional splice variants with different functional properties have been described for almost all the TRP channels(Vazquez & Valverde, 2006). TRP channels have six transmembrane segments (S1-S6) and intracellular N- and C-termini of variable lengths. A functional channel is formed by four subunits, and the channel pore is lined by transmembrane segments 5 and 6 of each subunit. The N- and C-termini contain multiple domains that are involved in channel assembly and regulation through interaction with other proteins or enzymes. The members of TRPM, TRPC, and TRPV subfamilies have a TRP box immediately after transmembrane segment 6 that plays a role in PIP2 binding (Rohacs, Lopes, Michailidis, & Logothetis, 2005) or subunit assembly (Garcia-Sanz et al., 2004). Several Ankyrin repeat domains (ARDs) on the N-terminal of TRPC, TRPV, and TRPA channels contribute to channel regulation. A CaM-binding site at the C-terminal is responsible for feedback modulation of TRPV, TRPC, and TRPM channels (Zhu, 2005). Phosphorylation sites for protein kinases have also been identified on TRPC, TRPV, TRPA, and TRPM channels (J. Huang, Zhang, & McNaughton, 2006; X. Yao, Kwan, & Huang, 2005). Many TRP channels are known to form heteromultimeric cation channels with distinct conduction properties and regulatory mechanisms (Ma et al., 2011). It should be noted that a large fraction of the literature on TRP channels in the vasculature uses cultured cells, which may not accurately reflect the function and regulation of TRP channels in the native, contractile VSMCs. Therefore, we will focus on the studies of TRP channels in native or fresh VSMCs.

A. TRPC channels (TRPC6/TRPC1/TRPC3).

TRPC channels are non-selective cation channels. The unitary conductance of TRPC1 channel is ~ 5pS (Strubing, Krapivinsky, Krapivinsky, & Clapham, 2001), while that of TRPC3–6 is 30–60 pS (Hofmann et al., 1999; Inoue et al., 2009; Inoue et al., 2001; Kamouchi et al., 1999; Schaefer et al., 2000). Single channel activity of TRPC6 channels has been observed in freshly isolated VSMCs from portal vein (Albert & Large, 2003) and mesenteric arteries (Saleh, Albert, Peppiatt, & Large, 2006). Inoe et al. showed that TRPC6 channels are functionally in native VSMCs from portal vein myocytes (Inoue et al., 2001). TRPC6 channel activity was stimulated by GqPCR activation and subsequent PLC-DAG signaling (Spassova, Hewavitharana, Xu, Soboloff, & Gill, 2006). Moreover, DAG activated TRPC6 channels directly and did not require PKC (Helliwell & Large, 1997; Hofmann et al., 1999). Ca2+ influx through TRPC6 channels was amplified by receptor and mechanical stimulation through mechanisms that involve PLC and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (Inoue et al., 2009). Additionally, PIP2 was shown to inhibit TRPC6 channels in native VSMCs (Albert, Saleh, & Large, 2008). It was also suggested that TRPC6 channels may be inhibited by interactions with other TRPC channels including TRPC1/C5 heteromultimeric channels (Shi, Ju, Saleh, Albert, & Large, 2010).

TRPC6 channels have been associated with myogenic vasoconstriction. TRPC6 channels on VSMC membranes were activated by mechanical forces (Spassova et al., 2006; Welsh, Morielli, Nelson, & Brayden, 2002), either via a direct activation of the channels by mechanical stimuli (Spassova et al., 2006) or via mechanosensitive GqPCR-PLC-DAG signaling (Welsh et al., 2002). Consistent with this mechanism, Gonzales et al. (Gonzales et al., 2014) suggested that intravascular pressure induces Ca2+ entry through TRPC6 channels that activates Ca2+ release through IP3Rs (Figure 1B), which then activates TRPM4 channels in the vicinity. TRPM4 channels mediate pressure-induced VSMC depolarization, thus activating VDCCs and vasoconstriction of cerebral arteries. TRPC6 channels are also involved in hypoxia-induced vasoconstriction of pulmonary arteries and increase in VSMC Ca2+ in pulmonary veins (Q. Wang, Wang, Yan, Sun, & Tang, 2016; Weissmann et al., 2006). Thus, TRPC6 channels appear to play a role in vasoconstriction in several vascular beds. Many details on the signaling mechanisms involved and the regulation of TRPC6 channel function, however, remain unknown.

TRPC1 channels have been frequently associated with store operated Ca2+ entry in VSMCs (Bergdahl et al., 2003), although several studies have disputed this function (DeHaven et al., 2009; Dietrich et al., 2007). TRPC1 and TRPC3 channels have also been linked with receptor-operated Ca2+ entry (D. Liu et al., 2009; Tai et al., 2008; Xi et al., 2008). A very low unitary conductance of TRPC1 channels suggests a small fraction of Ca2+ current under physiological conditions. Indeed, myogenic vasoconstriction, and response to adrenergic receptor signaling and membrane depolarization were unaltered in TRPC1−/− mice (Dietrich et al., 2007; Schmidt et al., 2010), suggesting that Ca2+ influx through TRPC1 channels may not be a major contributor to vasoconstriction. Ca2+ influx and vasoconstriction in response to endothelin-1 or Ang II were also reduced after TRPC3 channel downregulation (D. Liu et al., 2009; Xi et al., 2008), suggesting an involvement of TRPC3 channels in agonist-induced vasoconstriction. Another theory is that agonist-induced activation of TRPC3 channels may involve TRPC3-IP3R coupling, resulting in membrane depolarization and Ca2+ influx through VDCCs (Adebiyi, Narayanan, & Jaggar, 2011; Adebiyi et al., 2012; Adebiyi et al., 2010; Xi et al., 2008). Whether TRPC3 itself plays an important role in Ca2+ influx in VSMCs remains unclear.

B. TRPM4 channels.

Although essentially impermeable to Ca2+, TRPM4 channels play a central role in controlling membrane potential and therefore Ca2+ influx through VDCCs in VSMCs (Earley, Straub, & Brayden, 2007; Earley, Waldron, & Brayden, 2004; Gonzales, Garcia, Amberg, & Earley, 2010). Indeed, TRPC6 channel-mediated Ca2+ release from the ER was shown to be necessary for sustained activation of TRPM4 channels and myogenic vasoconstriction (Gonzales, Amberg, & Earley, 2010; Gonzales et al., 2014).

C. TRPV channels (TRPV1/TRPV4).

As opposed to TRPC channels, members of the TRPV subfamily show high unitary conductance and Ca2+ permeability, and conduct currents with significant Ca2+ fraction under physiological conditions. Recent work supports a role for TRPV1 channels in VSMCs and vasoconstriction (Cavanaugh et al., 2011). TRPV1 channels have a unitary conductance of 35–70 pS (Caterina et al., 2000; Caterina, Rosen, Tominaga, Brake, & Julius, 1999). TRPV1 channels were shown to be expressed in aortic and skeletal muscle arterial myocytes, and contributed to vasoconstriction and hindlimb vascular resistance (Kark et al., 2008; Lizanecz et al., 2006; Toth et al., 2014). TRPV1 channels were also implicated in vasoconstriction of mesenteric arteries (Porszasz et al., 2002). Moreover, TRPV1-mediated Ca2+ influx was found to be increased in pulmonary artery VSMCs from patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (Song et al., 2017). Thus, TRPV1 channels may represent an important Ca2+ influx pathway in VSMCs, at least in some vascular beds.

TRPV4 channels are one of the most studied Ca2+ influx pathways in the vasculature. TRPV4 channels carry Ca2+ with permeability ratios of 6–10 PCa/PNa (Voets et al., 2002; Watanabe, Vriens, Janssens, et al., 2003; Watanabe, Vriens, Prenen, et al., 2003; Watanabe et al., 2002). TRPV4 channels have a unitary conductance of 50–60 pS at −60 mV, and 90–100 pS at + 60 mV (Strotmann, Harteneck, Nunnenmacher, Schultz, & Plant, 2000; Strotmann, Schultz, & Plant, 2003; Watanabe, Vriens, Janssens, et al., 2003; Watanabe, Vriens, Prenen, et al., 2003; Watanabe et al., 2002). TRPV4 channels can be activated by a variety of stimuli including temperature, mechanical forces, and neurohumoral mediators (endocannabinoids, arachidonic acid, GqPCR signaling, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids or EETs) (Bagher et al., 2012; Hartmannsgruber et al., 2007; Kohler et al., 2006; Loot et al., 2008; Marrelli, O’Neil R, Brown, & Bryan, 2007; Mendoza et al., 2010; S. Sonkusare et al., 2014; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2012; Vriens et al., 2005; Watanabe, Vriens, Prenen, et al., 2003; Watanabe et al., 2002). Earley and colleagues showed for the first time that Ca2+ influx through VSMC TRPV4 channels caused vasodilation instead of vasoconstriction in cerebral arteries by activating RyR-BK channel signaling, which hyperpolarized VSMC membrane by ~ 10 mV (Earley, Heppner, Nelson, & Brayden, 2005). A recent study by Mercado et al. (Mercado et al., 2014) indicated that Ang II activates unitary Ca2+ influx signals through TRPV4 channels (“TRPV4 sparklets”, Table 1) in VSMCs via angiotensin II receptor 1 (AT1) -PLC-DAG-PKC signaling (Figure 1B). Moreover, PKC activation of TRPV4 sparklets requires PKC anchoring by A kinase anchoring protein 150 (AKAP150) close to the channel. TRPV4-RyR-BK channel signaling then limits Ang II-induced vasoconstriction. It is plausible that the functional role of VSMC TRPV4 channels varies with vascular beds. Indeed, VSMC TRPV4 channels were shown to contribute to hypoxia-induced vasoconstriction of pulmonary arteries (Xia et al., 2013; X. R. Yang et al., 2012).

Ca2+ influx through store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) in VSMCs.

Many studies have investigated the role of SOCE in SMC proliferation, differentiation, and contraction (Leung, Yung, Yao, Laher, & Huang, 2008). SOCE channels are activated by the depletion of the ER Ca2+ stores (Krause, Pfeiffer, Schmid, & Schulz, 1996; Parekh & Putney, 2005; Putney, 1990). The two main proteins involved in this mechanism are STIM and Orai. STIM (stromal interaction molecule) is located in the ER membrane (Baba et al., 2006; X. Yang, Jin, Cai, Li, & Shen, 2012), with its Ca2+-sensing N-terminal tail facing the ER lumen. The C-terminal tail faces the cell cytosol and it couples with the pore-forming Orai subunit of the channel (CRAC or Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel) (Li et al., 2007; Liou et al., 2005; Roos et al., 2005). Orai forms a Ca2+ selective channel pore that is made up of four transmembrane domains with cytosolic N- and C-termini (Ji et al., 2008; Mignen, Thompson, & Shuttleworth, 2008). The C-terminal tail of Orai has been shown to be crucial for tethering with STIM (Muik et al., 2008; Park et al., 2009). When the ER Ca2+ store is depleted, Ca2+ dissociates from the luminal side of STIM, leading to STIM oligomerization and redistribution close to the plasma membrane. The active oligomer of STIM interacts with the C-terminal tail of Orai, forming the functional channel complex that allows Ca2+ entry (Derler, Jardin, & Romanin, 2016). It has been suggested that SOCE may not be active in all native VSMCs, and its presence may be indicative of a phenotypic switch to a proliferative state or to cell culture conditions (Earley & Brayden, 2015). VSMC SOCE has been variously shown to be TRPC channel-dependent or independent by different laboratories (DeHaven et al., 2009; Potier et al., 2009). In pulmonary vasculature, SOCE through TRPC1 channels caused vasoconstriction (Kunichika et al., 2004) and contributed to hypoxia-induced pulmonary vasoconstriction (Lu, Wang, Shimoda, & Sylvester, 2008). Another study proposed that SOCE through TRPC1 channels in VSMCs activates BK channels to cause vasorelaxation (Kwan et al., 2009). Moreover, BK channels co-localized with TRPC1 channels, thus enabling TRPC1-BK spatial coupling. Similarly, TRPC5 and TRPC7 channels have also been linked with SOCE in VSMCs from pial, mesenteric, and coronary arteries (Saleh, Albert, Peppiatt-Wildman, & Large, 2008; S. Z. Xu, Boulay, Flemming, & Beech, 2006).

Junctional Ca2+ transient (jCaTs) in VSMCs.

In addition to norepinephrine, sympathetic nerve stimulation releases adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and neuropeptide Y as co-transmitters (Burnstock, 2007). ATP can activate VSMC purinergic P2X1R receptor channels, causing an influx of Ca2+ and Na+. Ca2+ influx through P2X1Rs can be seen as a junctional Ca2+ transients (jCaTs) at the varicosities of perivascular nerves (Lamont, Vainorius, & Wier, 2003; Lamont & Wier, 2002). jCaTs represent local increases in Ca2+ (Figure 1B, Table 1), but can lead to global increase in Ca2+ through IP3R -mediated Ca2+ release (Povstyan, Harhun, & Gordienko, 2011). jCaTs can be elicited by stimulation of perivascular nerves (Lamont, Vial, Evans, & Wier, 2006).

Summary and Conclusions- Ca2+ signals in VSMCs

Ca2+ signals in VSMCs can occur via activation of multiple ion channels, including IP3Rs and RyRs in the ER/SR membrane and VDCCs, TRP channels, STIM/Orai, and P2X1Rs at the plasma membrane. The VSMC Ca2+ signals can occur in a spatially restricted or whole-cell manner. Although individual Ca2+ signals have been associated with distinct functional effects (vasodilation or vasoconstriction), the observed functional effect often reflects an interplay among different Ca2+ signals. For example, VDCCs and TRP channels can signal to one another, or to intracellular RyRs and IP3Rs to either amplify or limit the functional effect. Physiological stimulus-Ca2+ signal coupling is another key determinant of the downstream signaling mechanisms and functional effects, as seen with RyRs, which can dilate or constrict the arteries depending on the intensity of the stimulus. The functional effect also depends on the Ca2+ signal-target coupling, which in turn is determined by the spatial localization of Ca2+ channels with Ca2+-sensitive targets, as seen with differential effects of VSMC TRPV4 channels on vascular diameter in cerebral and pulmonary circulations. There appears to be a significant amount of heterogeneity among vascular beds with respect to the expression of ion channels that underlie the Ca2+ signals (Table 2). For example, L-type Ca2+ channels contribute to myogenic tone in some vascular beds, whereas T-type Ca2+ channels dominate in other vascular beds. Moreover, some T-type Ca2+ channels contribute to the development of myogenic constriction, whereas other T-type Ca2+ channels oppose myogenic constriction. Thus, the overall functional effect of a VSMC Ca2+ signal may be determined by its source, physiological stimulus, spatial nature, and preferential coupling with the effector mechanisms.

Table 2.

Heterogeneity of Ca2+ signaling mechanisms.

| Channel | Heterogeneity in different vascular beds |

|---|---|

| T-type and L-type Ca2+ |

|

| TRPV4 |

|

| TRPC6 |

|

| TRPV1 |

|

| TRPC1 |

|

| TRPA1 |

|

CALCIUM SIGNALS IN ECs

ECs line the inner walls of all the blood vessels, where they control vascular resistance, permeability, inflammation, and angiogenesis (G. E. Davis, Stratman, Sacharidou, & Koh, 2011; Furchgott & Zawadzki, 1980; Vandenbroucke, Mehta, Minshall, & Malik, 2008). ECs are directly exposed to the mechanical forces exerted by the blood, including shear stress and pressure. Physiological function of ECs is also modulated by mediators in the bloodstream and those released by VSMCs or nerves (Busse & Fleming, 2003; P. F. Davies, 2009; Erkens et al., 2017; Faraci & Heistad, 1991; Garland et al., 2017; Griffith, 2002; Harrison, Treasure, Mugge, Dellsperger, & Lamping, 1991; Helmke & Davies, 2002; Hong, Cope, Marziano, & Sonkusare, 2016; Nausch et al., 2012; Takahashi, Ishida, Traub, Corson, & Berk, 1997; Tran et al., 2012). ECs send projections to VSMCs (myoendothelial projections or MEPs) that couple the two cell types via myoendothelial gap junctions or MEGJs (Sandow & Hill, 2000; Sandow, Tare, Coleman, Hill, & Parkington, 2002). The resting membrane potential of ECs has been shown to be in the range of −35 to −45 mV (Gauthier & Rusch, 2001; He & Curry, 1995; Ledoux, Bonev, & Nelson, 2008; Welsh & Segal, 1998; Weston et al., 2005). Activation of Ca2+ signaling pathways hyperpolarizes ECs by ~ 10–15 mV. Endothelium-dependent vasodilation of resistance arteries involves a direct transmission of hyperpolarization across the MEGJs (Dora et al., 2003; Fleming, 2000; Sandow et al., 2002; Yamamoto, Imaeda, & Suzuki, 1999) or release of substances/factors that activate vasodilatory signaling in VSMCs in a paracrine manner including NO, K+ ions, EETs, and H2O2 (Campbell, Gebremedhin, Pratt, & Harder, 1996; Edwards, Dora, Gardener, Garland, & Weston, 1998; Gebremedhin, Harder, Pratt, & Campbell, 1998; Y. Liu, Bubolz, Mendoza, Zhang, & Gutterman, 2011; Matoba et al., 2000). Direct transmission of hyperpolarization is referred to as endothelium-derived hyperpolarization (EDH), and involves activation of endothelial Ca2+-activated small and intermediate conductance K+ (SK and IK, respectively) channels (Burnham et al., 2002; Bychkov et al., 2002; Eichler et al., 2003; Feletou & Vanhoutte, 2006) and inward rectifier K+ (Kir) channels (Jackson, 2005, 2017; S. K. Sonkusare, Dalsgaard, Bonev, & Nelson, 2016).

Intracellular Ca2+ is a key signaling molecule in endothelium-dependent vasodilation and therefore, endothelial control of vascular resistance. Many physiological stimuli activate distinct Ca2+ signals in ECs, including flow/shear stress (Hill-Eubanks, Gonzales, Sonkusare, & Nelson, 2014; Kohler et al., 2006; Mendoza et al., 2010), intravascular pressure (Bagher et al., 2012), GqPCR signaling (acetylcholine or ACh, bradykinin, ATP) (Marziano et al., 2017; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2014), hydrogen sulfide (Naik, Osmond, Walker, & Kanagy, 2016), and nerve-stimulation (Garland et al., 2017; Hong et al., 2018; Nausch et al., 2012; Tran et al., 2012). Ca2+-sensitive vasodilatory pathways in ECs include: 1) endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activation and NO release (Fleming, 2010; Fleming & Busse, 1999a, 1999b; Forstermann & Sessa, 2012); 2) activation of IK and SK channels and membrane hyperpolarization; and 3) release of prostaglandins through phospholipase A2-dependent activation of cyclooxygenase. Studies over the past decade support the idea that physiological increases in endothelial Ca2+ are spatially restricted, and occur at functionally important microdomains including MEPs (Bagher et al., 2012; Garland et al., 2017; Ledoux, Taylor, et al., 2008; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2012; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2014; Sullivan et al., 2015; Tran et al., 2012). This has resulted in discoveries of distinct local Ca2+ signals, including Ca2+ puffs (Huser & Blatter, 1997; Mumtaz, Burdyga, Borisova, Wray, & Burdyga, 2011), Ca2+ pulsars (Ledoux, Taylor, et al., 2008; Nausch et al., 2012), Ca2+ waves (Bagher, Davis, & Segal, 2011; Emerson & Segal, 2000; Kansui, Garland, & Dora, 2008; McCarron, Chalmers, MacMillan, & Olson, 2010; Tallini et al., 2007; Wilson, Saunter, Girkin, & McCarron, 2016), Ca2+ wavelets (Tran et al., 2012), TRPV4 sparklets (Hong et al., 2016; Marziano et al., 2017; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2012; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2014), TRPA1 sparklets (Sullivan et al., 2015), and TRPV3 sparklets (Pires, Sullivan, Pritchard, Robinson, & Earley, 2015). Regardless of the source, most localized Ca2+ signals cause Ca2+-CaM–dependent activation of IK and SK channels to dilate resistance arteries. IK/SK channel activation results in EC membrane hyperpolarization, which is then transmitted to VSMCs via the MEGJs, thereby hyperpolarizing VSMC membranes, deactivating VDCCs, and dilating the arteries (Nelson & Quayle, 1995). Small pulmonary arteries appear to be an exception to this rule as localized Ca2+ signals in these arteries activate eNOS instead of IK/SK channels, although IK/SK channels are present and are activatable (Marziano et al., 2017). In large, conduit arteries, EC Ca2+ has been linked with eNOS activation. Resulting NO diffuses to surrounding VSMCs and activates guanylyl cyclase (GC)-PKG-dependent vasodilatory mechanisms (Fleming & Busse, 1999a; Furchgott & Vanhoutte, 1989; Ignarro, Buga, Wood, Byrns, & Chaudhuri, 1987; Moncada & Higgs, 2006; Murad, 1999; Vanhoutte, Zhao, Xu, & Leung, 2016).

Several recent studies have devised approaches to describe spatiotemporal nature of Ca2+ signals in ECs (Francis et al., 2012; Francis et al., 2016; Wilson, Lee, & McCarron, 2016; Wilson, Saunter, et al., 2016). These studies reveal a striking heterogeneity among ECs with respect to Ca2+ activity. While some ECs show increased Ca2+ activity in response to a stimulus, other ECs remain silent (Lee et al., 2018). This has been attributed to differential receptor expression. It should also be emphasized that Ca2+ imaging data in the literature present snapshots of a few minutes. During this snapshot, some of the ion channels could be in their closed state. Since Ca2+ signals are a result of openings of ion channels, the signal activity may depend on the open state probability of the channels and closed state durations. Therefore, imaging for a longer duration at high frame rates may be needed for a more complete picture on EC heterogeneity.

Ca2+ release from intracellular stores through IP3Rs in ECs: pulsars, waves, wavelets, and puffs.

IP3Rs are the most studied intracellular Ca2+ release channels in ECs. All three IP3R isoforms (IP3R1–3) are expressed in ECs (Grayson et al., 2004; Iwai, Michikawa, Bosanac, Ikura, & Mikoshiba, 2007; Ledoux, Taylor, et al., 2008), although only IP3R1 and IP3R2 were found at the MEPs (Toussaint, Charbel, Blanchette, & Ledoux, 2015). RyR channels are also expressed in various ECs, however, the evidence for a functional role of endothelial RyR-mediated Ca2+ release is sparse (Kohler et al., 2001; Lesh, Marks, Somlyo, Fleischer, & Somlyo, 1993; X. Wang, Lau, Li, Yoshikawa, & van Breemen, 1995).

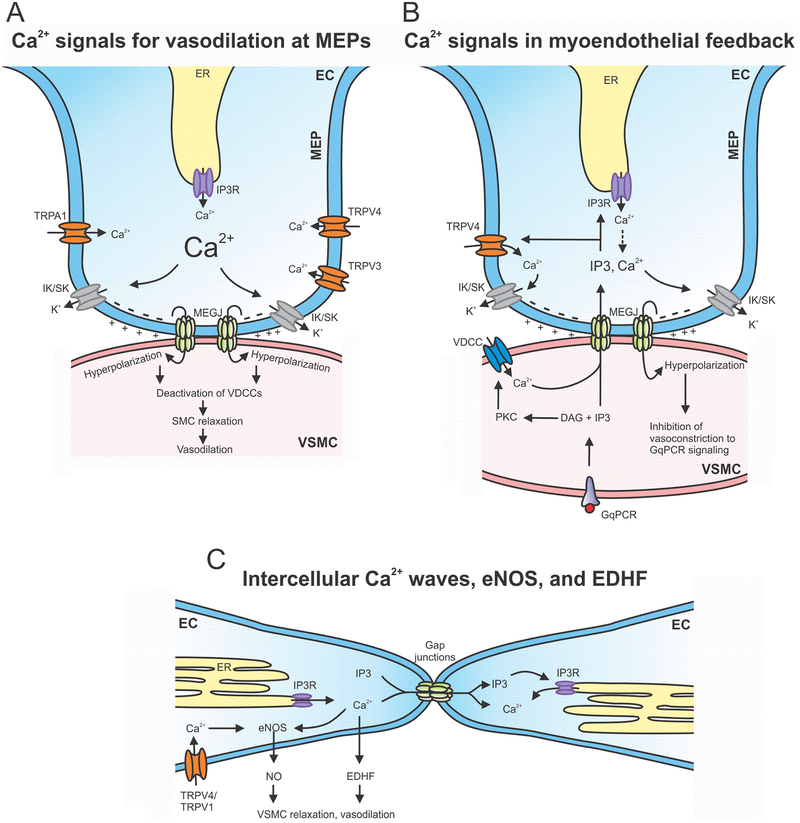

Using mice that express Ca2+ biosensor GCaMP2 selectively in the endothelium, Ledoux and colleagues showed that majority of the spontaneous Ca2+ release in ECs occurs at MEPs in the form of spatially fixed, repetitively occurring signals. These signals, termed Ca2+ pulsars (Table 3), are mediated by IP3Rs on ER membrane at the MEPs (Ledoux, Taylor, et al., 2008). Ca2+ pulsars have a spatial spread of ~ 14 μm2, and show kinetic properties that are different from Ca2+ “puffs” described earlier in Xenopus oocytes and cultured cells (Thomas et al., 2000; Y. Yao, Choi, & Parker, 1995). Multiple reports suggest localization of IK channels at the MEPs (Bagher et al., 2012; Sandow, Neylon, Chen, & Garland, 2006). Spatial proximity of Ca2+ pulsars and IK channels results in the activation of IK channels, thereby hyperpolarizing the EC membrane and dilating the arteries (Figure 2A). Bagher et al. showed that both IK and SK channels are localized at the MEPs (Bagher et al., 2012), whereas Sandow et al. found that SK channels are concentrated at the EC borders (Sandow et al., 2006). CaM is tethered to the C-termini of both the IK and SK channels, and confers the sensitivity to cytosolic Ca2+. Regardless of their spatial location, both IK and SK channels play important roles in the modulation of vasoconstriction and blood pressure (Brahler et al., 2009; Si et al., 2006; Taylor et al., 2003).

Table 3.

Local Ca2+ signals in endothelial cells.

| Ca2+ signal | Source | Functional effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRPV4 sparklets | Unitary Ca2+ influx signals through TRPV4 channels |

|

(Hong et al., 2018; Marziano et al., 2017; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2012; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2014; Sullivan & Earley, 2013) |

| TRPA1 sparklets | Ca2+ influx signals through TRPA1 channel | Activation of IK/SK channels, endothelium-dependent vasodilation | (Pires & Earley, 2018; Sullivan et al., 2015) |

| TRPV3 sparklets | Unitary Ca2+ influx signals through TRPV3 channels | Activation of IK/SK channels, endothelium-dependent vasodilation | (Earley et al., 2010; Pires et al., 2015) |

| Ca2+ pulsars | Ca2+ release from the ER through IP3Rs | Activation of IK/SK channels, endothelium-dependent vasodilation | (Ledoux, Taylor, et al., 2008; Nausch et al., 2012; Toussaint et al., 2015) |

| Ca2+ waves | Propagating Ca2+ induced Ca2+ release from SR through IP3Rs | Activation of eNOS and IK/SK channels, endothelium-dependent vasodilation | (Kansui et al., 2008; McCarron et al., 2010; Tallini et al., 2007) |

| Ca2+ wavelets | Ca2+ release through SR at MEPs through IP3Rs | Negative regulation of α1-adrenergic activation-induced vasoconstriction through myoendothelial feedback | (Tran et al., 2012) |

Figure 2. Ca2+ signaling networks in ECs.

A. Ca2+ influx through TRPV4, TRPA1, and TRPV3 channels, and IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release from the ER at myoendothelial projections (MEPs) activate IK (intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated potassium) and SK (small conductance Ca2+-activated potassium) channels. IK/SK channel activation results in membrane hyperpolarization that is transmitted to VSMCs (vascular smooth muscle cell) via myoendothelial gap junctions (MEGJs). VSMC hyperpolarization then deactivates VDCCs, resulting in vasodilation. B. IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release from the ER and Ca2+ influx through TRPV4 channels at the MEPs have been associated with myoendothelial feedback mechanism that limits VSMC contraction. Activation of VSMC GqPCR signaling results in the flux of IP3 and/or Ca2+ from VSMCs to ECs via MEGJs. IP3/Ca2+ can activate IP3Rs and TRPV4 channels at the MEPs, resulting in IK/SK channel-dependent vasodilation. C. Increase in endothelial Ca2+ can also activate the release of nitric oxide or hyperpolarizing factors that can act on VSMCs. Additionally, intercellular propagation of Ca2+ waves involves the transfer of IP3 and/or Ca2+ between the neighboring ECs (endothelial cell) and Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. MEP: myoendothelial projection; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; GqPCR: G-protein coupled receptor; PKC: protein kinase C; DAG: diacylglycerol; VDCC: voltage dependent Ca2+ channel; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; NO: nitric oxide; EDHF: endothelial derived hyperpolarization factor.

Endothelial Ca2+ signaling also plays a requisite role in limiting α1 adrenergic receptor-induced VSMC contraction through a phenomenon called myoendothelial feedback (Garland et al., 2017; Hong et al., 2018; Nausch et al., 2012; Tran et al., 2012) (Figure 2B). Myoendothelial feedback is thought to be mediated by the flux of Ca2+ and IP3 from VSMCs to ECs across the MEGJs (Garland et al., 2017; Hong et al., 2018; Kansui et al., 2008). Nausch et al. showed that nerve stimulation-induced activation of VSMC α1 adrenergic receptor promotes VSMC-EC communication and activates Ca2+ pulsars at MEPs, thereby opposing nerve stimulation-induced vasoconstriction. Tran et al. indicated that activation of α1 adrenergic receptors with phenylephrine (PE) results in IP3 flux from VSMCs to ECs across MEGJs. The resulting IP3R-mediated Ca2+ signals in ECs, termed Ca2+ wavelets, were localized at the MEPs. Ca2+ wavelets activated IK and SK channels to limit PE-induced vasoconstriction (Tran et al., 2012). Interestingly, Garland and colleagues proposed that VSMC Ca2+, elevated by PE-induced opening of L-type VDCCs, moved across MEGJs and activated IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release in ECs (Garland et al., 2017). In another recent study, Hong et al. discovered that Ca2+ influx through TRPV4 channels at the MEPs is predominantly responsible for the feedback inhibition of PE-induced vasoconstriction at higher levels of α1-adrenergic activation (Hong et al., 2018). In this study, activation of TRPV4 channels at the MEPs was dependent on IP3, but was not affected by Ca2+, supporting the flux of IP3 across MEGJs (Figure 2B). Additionally, Biwer et al. showed that endothelial calreticulin, a Ca2+ binding protein, is necessary for PE-induced Ca2+ signaling at the MEPs (Biwer et al., 2017). Thus, SMC-EC communication at MEGJs and flux of IP3/Ca2+ are necessary for myoendothelial feedback.

Spontaneous IP3R-mediated Ca2+ oscillations, Ca2+ puffs, and Ca2+ waves have also been described in ECs (Burdyga, Shmygol, Eisner, & Wray, 2003; Huser & Blatter, 1997; Kansui et al., 2008; McSherry et al., 2006; Mumtaz et al., 2011) (Table 3). Ca2+ waves that propagate from one EC to another have been reported by several groups (Emerson & Segal, 2000; McCarron et al., 2010; Wilson, Saunter, et al., 2016) (Figure 2C). Local application of ACh was shown to activate Ca2+ waves that travelled for over 1 mm (Bagher et al., 2011; Tallini et al., 2007), indicating propagation across several ECs. As expected, these Ca2+ waves coincided with arteriolar dilation. Intercellular transmission of Ca2+ waves is blocked by gap junction inhibitors (Emerson & Segal, 2000), suggesting that gap junction transmission is necessary for the propagation of Ca2+ waves. Intercellular Ca2+ waves also appear to require both Ca2+ and IP3 for propagation (McCarron et al., 2010) (Figure 2C). Studies on intercellular propagation of Ca2+ waves support the concept that endothelium is a network of interconnected cells that communicate with one another. One theory is that intensity of the stimulus determines the coordination between Ca2+ signals in neighboring cells (Wilson, Lee, et al., 2016). It is also plausible that ECs with similar sensitivity cluster together, which may create patches of ECs that show coordinated Ca2+ activity (McCarron, Lee, & Wilson, 2017). In another type of intercellular communication termed conducted hyperpolarization, Ca2+-induced hyperpolarization of one EC can be transmitted to the neighboring EC via gap junctions. This results in the spreading of dilatory signal along blood vessels, which can play a crucial role in the autoregulation of blood flow (Behringer & Segal, 2012; Emerson, Neild, & Segal, 2002).

Ca2+ influx through TRP channels in ECs.

Ca2+ influx through TRP channels at the plasma membrane plays a crucial role in EC Ca2+ signaling. Multiple TRP channels have been reported in ECs, although a functional role has been shown for only some of the TRP channels in the native endothelium.

A. TRPV4 channels

TRPV4 channels are thought to be a major Ca2+ influx pathway in ECs. Endothelial TRPV4 channels can be activated by mechanical stimuli including changes in shear stress/pressure (Hartmannsgruber et al., 2007; Kohler et al., 2006; Loot et al., 2008; Mendoza et al., 2010; Vriens et al., 2004), GqPCR activation (Marziano et al., 2017; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2012; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2014), and hydrogen sulfide (Naik et al., 2016). Several studies have implicated endothelial TRPV4 channels in mechanotransduction (X. Gao, Wu, & O’Neil, 2003; Hartmannsgruber et al., 2007; Kohler et al., 2006; Loot et al., 2008; Mendoza et al., 2010; Vriens et al., 2004), although direct mechanosensitivity of TRPV4 channels remains in doubt. One theory is that TRPV4 channels may not be inherently mechanosensitive, but are activated by a mechanosensitive signaling cascade that involves activation of cytochrome P450 epoxygenases and release of EETs, which in turn activate TRPV4 channels (Loot et al., 2008; Marrelli et al., 2007). The major physiological inhibitors of TRPV4 channels include NO and PIP2. While NO lowered the functional coupling among TRPV4 channels in a PKG-dependent manner (Marziano et al., 2017), PIP2 exerted a tonic inhibitory effect on TRPV4 channel function in capillary ECs (Harraz, Longden, Hill-Eubanks, & Nelson, 2018). Intracellular Ca2+ also modulates TRPV4 channel activity in a CaM-dependent manner (Strotmann et al., 2003; Strotmann, Semtner, Kepura, Plant, & Schoneberg, 2010); Ca2+ potentiates TRPV4 channel activity at low concentrations and inhibits it at high concentrations (Strotmann et al., 2003). Ca2+-dependent potentiation of TRPV4 channel activity contributes to functional coupling/cooperativity among TRPV4 channels in a cluster, whereby Ca2+ influx through one channel results in the activation of the neighboring TRPV4 channel in the same cluster (S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2012; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2014). The functional coupling among TRPV4 channels serves to amplify Ca2+ influx through a small number of channels per EC (S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2012; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2014).

Recent discoveries have identified TRPV4 channels as a key regulator of Ca2+ influx at the MEPs (Figure 2A, 2B). Sonkusare et al. discovered unitary Ca2+ influx signals through TRPV4 channels, termed TRPV4 sparklets, in native endothelium from resistance mesenteric arteries (S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2012; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2014). The majority of baseline and agonist-induced TRPV4 sparklet activity occurred at the MEPs, and could be distinguished from Ca2+ pulsar activity based on different kinetic properties (Hong et al., 2018; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2012; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2014). Consistent with the localization of IK and SK channels at the MEPs (Bagher et al., 2012), TRPV4 sparklets activated IK and SK channels, resulting in membrane hyperpolarization and vasodilation (S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2012). Additionally, ACh was shown to dilate resistance mesenteric arteries predominantly via activation of endothelial TRPV4-IK/SK pathway, suggesting that Ca2+ influx through TRPV4 channels may be necessary for EDH signaling (Saliez et al., 2008; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2012; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2014; D. X. Zhang et al., 2009). IK/SK channel-mediated K+ efflux and membrane hyperpolarization activated endothelial inward rectifier Kir2.1 channels, which served as boosters of hyperpolarization (Jackson, 2017; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2016). Marziano et al. showed that TRPV4 sparklets preferentially coupled with eNOS in pulmonary arteries (Marziano et al., 2017), emphasizing the different Ca2+ signaling mechanisms in ECs from systemic and pulmonary arteries.

ACh activation of TRPV4 sparklets was PKC-dependent, and required anchoring of PKC by AKAP150, which is also concentrated at the MEPs (Adapala et al., 2011; S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2014). AKAP150 was also found to be important for functional coupling among TRPV4 channels in a cluster, although the precise mechanism for this interaction remains unknown (S. K. Sonkusare et al., 2014). Hong et al. showed that TRPV4 sparklets at the MEPs play an important role in limiting PE-induced vasoconstriction of mesenteric arteries (Hong et al., 2018). In response to α1 adrenergic receptor activation by PE, IP3 flux from SMCs to ECs resulted in a direct activation of Ca2+ influx through TRPV4 channels at the MEPs (Figure 2B). In a separate study, Ca2+ influx through TRPV4 channels was shown to couple with IP3Rs to mediate endothelium-dependent vasodilation in response to changes in intravascular pressure (Bagher et al., 2012). Consistent with TRPV4 channel-mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilation, several studies reported that TRPV4 channel agonists lower systemic arterial pressure (Willette et al., 2008) and pulmonary arterial pressure (Pankey, Zsombok, Lasker, & Kadowitz, 2014), effects that were attributed to lowering of vascular resistance. The resting pressure, however, was unchanged in global TRPV4−/− mice (Hong et al., 2018; D. X. Zhang et al., 2009). It is plausible that a compensatory upregulation of other Ca2+ influx pathways contributes to the confounding results in global TRPV4−/− mice. Therefore, a definitive assessment of a role for endothelial TRPV4 channels in the regulation of resting blood pressure may require inducible endothelium-specific TRPV4−/− mice.

B. TRPV3 channels.

TRPV3 channels show a high unitary conductance of ~ 150 pS, and can be activated by many dietary compounds (Table 4) (Chung, Lee, Mizuno, Suzuki, & Caterina, 2004a, 2004b; H. Xu, Delling, Jun, & Clapham, 2006). Earley et al. provided the first functional evidence for TRPV3 channels in cerebral artery endothelium and showed that when activated with carvacrol (a substance found in oregano, Table 4), TRPV3 channels dilated cerebral arteries (Earley, Gonzales, & Garcia, 2010). Very recently, Pires et al. identified carvacrol-induced TRPV3 sparklets in ECs from brain parenchymal arterioles and showed that TRPV3 sparklets dilated these arterioles (Pires et al., 2015). The unitary amplitude of TRPV3 sparklets was greater than that of TRPV4 and TRPA1 sparklets, consistent with unitary conductances of these channels. There are no studies of endothelial TRPV3 channels in global or cell-specific TRPV3 knockout mice. Therefore, the contribution of TRPV3 channels in regulating physiological functions of ECs remains unclear.

Table 4.

Pharmacological tools that target Ca2+ release and Ca2+ influx channels.

C. TRPV1 channels.

TRPV1 channels have also been shown to play a role in EC Ca2+ influx. TRPV1 channel agonist capsaicin activated eNOS and dilated mesenteric arteries (D. Yang et al., 2010). Bratz et al. showed that capsaicin (Table 4)-induced vasodilation of coronary arteries was dependent on NO release, supporting the concept that Ca2+ influx through TRPV1 channels activates eNOS (Bratz et al., 2008). Other studies also support the role of TRPV1-eNOS signaling in endothelium-dependent vasodilation (L. Chen et al., 2015; Ching et al., 2011; Torres-Narvaez et al., 2012). Moreover, there is in vivo evidence for a possible role of TRPV1 channels in controlling blood flow (Guarini et al., 2012; Ives et al., 2017). Surprisingly, TRPV1 reporter mouse showed expression of TRPV1 channels in VSMCs, but not in ECs (Cavanaugh et al., 2011). Thus, the role of TRPV1 channels in endothelium-dependent vasodilation remains unclear.

D. TRPA1 channels.

TRPA1 channels show high Ca2+ permeability and a unitary conductance of ~ 98 pS under physiological conditions (Nagata, Duggan, Kumar, & Garcia-Anoveros, 2005). TRPA1 channels are activated by dietary compounds including allicin, allyl isothiocyanate, and cinnamaldehyde (Earley & Brayden, 2015) (Table 4). The activity of TRPA1 channels is also modulated by Ca2+ in a biphasic manner (Latorre, Brauchi, Orta, Zaelzer, & Vargas, 2007; Y. Y. Wang, Chang, Waters, McKemy, & Liman, 2008), showing channel potentiation at low Ca2+ levels and inhibition at high Ca2+ levels.

Vasodilatory and hypotensive responses to natural compounds that activate TRPA1 channels have been mostly attributed to activation of the channel in sensory nerves and subsequent release of dilatory neuropeptides (Aubdool et al., 2014; Bautista et al., 2005; Pozsgai et al., 2010). Earley and colleagues showed that TRPA1 channels are expressed in cerebral endothelium, but not in mesenteric, coronary, or renal arteries (Earley, Gonzales, & Crnich, 2009; Sullivan et al., 2015). Moreover, Ca2+ influx through TRPA1 channels selectively activated IK/SK and Kir channels in cerebral arteries, pointing to the involvement of EDH signaling in TRPA1-induced vasodilation. In a separate study, TRPA1 channel activator allyl isothiocyanate was shown to induce large IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release signals in cerebral arteries, supporting TRPA1-IP3R functional coupling (Qian, Francis, Solodushko, Earley, & Taylor, 2013). TRPA1 channels can be activated by ROS and ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation products (Andersson, Gentry, Moss, & Bevan, 2008). In a recent study, Sullivan et al. revealed that TRPA1 channels co-localize with ROS generating enzyme NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) and were activated by NOX2 (Sullivan et al., 2015). Endothelial TRPA1 channels can also be activated by mitochondrial ROS in response to hypoxia (Pires & Earley, 2018). Therefore, it appears that ROS and ROS-derived products may modulate the function of endothelial TRPA1 channels, and therefore endothelium-dependent vasodilation in cerebral arteries under normal and disease conditions.

E. TRPC channels.

Non-selective TRPC cation channels have been associated with Ca2+ influx in ECs. TRPC1 channels were found to localize with TRPV4 channels in freshly isolated ECs from mesenteric arteries, and dilation to TRPV4 agonist was lowered by TRPC1 inhibition (H. Z. E. Greenberg et al., 2017). Moreover, Ma et al. proposed that TRPC1/TRPV4 subunits form heteromeric channels that are responsible for SOCE in aortic ECs (Ma et al., 2011). Additionally, TRPC3 channels have been shown to contribute to ACh-induced vasodilation of human mammary arteries (G. Gao et al., 2012). ACh-induced relaxation was also impaired in the aorta from TRPC3−/− mice (Kochukov, Balasubramanian, Noel, & Marrelli, 2013). A recent study by Sandow et al. suggested that TRPC3 channels localize at the MEPs and TRPC3 inhibitor Pyr3 (Table 4) lowers ACh-induced vasodilation in rat mesenteric arteries (Senadheera et al., 2012). In another study, endothelial TRPC3 channels were shown to couple with SK channels to cause membrane hyperpolarization and vasodilation, suggesting a role for TRPC3 channels in EDH signaling (Kochukov, Balasubramanian, Abramowitz, Birnbaumer, & Marrelli, 2014). Considering the DAG-activatable nature of TRPC channels, it is conceivable that these channels contribute to vasodilation induced by endothelial GqPCR-PLC-DAG signaling. Additionally, it has been proposed that heteromeric channels with TRPC1 and TRPC3 subunits may also be involved in endothelium-dependent vasodilation (Kochukov et al., 2013). ACh-induced relaxation of aortic rings was also lower in TRPC4−/− mice (Senadheera et al., 2012). Overall, endothelial TRPC channels appear to be important for endothelial Ca2+ signaling, at least in some vascular beds.

Summary and Conclusions- ECs

Ca2+ signals in native ECs represent Ca2+ release from the ER via IP3Rs or the influx of Ca2+ through TRP channels at the plasma membrane. Although several TRP channels are thought to be important for Ca2+ influx in the native ECs, Ca2+ influx through only TRPV4, TRPA1, and TRPV3 channels has been directly recorded. It is highly likely that the extent of endothelium-dependent vasodilation is determined by the interactions between Ca2+ influx and intracellular Ca2+ release pathways. The physiological increases in endothelial Ca2+ occur in a spatially localized and repetitive manner. Endothelial Ca2+ signals can be activated by intravascular pressure, flow/shear stress, or GqPCR signaling. A significant heterogeneity in Ca2+ signal activity has been observed among ECs from the same vascular bed or among ECs from different vascular beds (Table 2). This heterogeneity has been attributed to differential expression of TRP channels or GqPCRs on EC membranes. Moreover, EC Ca2+ signals can couple with distinct downstream effector mechanisms. In conduit arteries, Ca2+ signals appear to selectively activate eNOS, whereas in small resistance arteries they activate IK and SK channels. Interestingly, localized Ca2+ signals activate eNOS in pulmonary resistance vasculature. The majority of the signaling elements involved in endothelium-dependent vasodilation are localized at the MEPs, thus increasing the spatial proximity of the Ca2+ signals with its effector mechanisms. Thus, ECs in different vascular beds use differential stimulus-Ca2+ signal and Ca2+ signal-effector coupling to cause endothelium-dependent vasodilation.

Perspective.

Numerous Ca2+ signals control vascular diameter, thereby influencing vascular resistance. Understanding the molecular basis for heterogeneity in Ca2+ signaling mechanisms among different vascular beds will provide crucial insights into the functional differences among these vascular beds. Although the functional roles for most of the Ca2+ signals have been identified, their physiological roles in controlling vascular resistance and blood pressure remain unknown. Developing cell-specific knockout mouse models will assist in identifying the physiological roles for individual EC and VSMC Ca2+ signals. Under physiological conditions, distinct Ca2+ signals in close proximity can interact with one another to regulate the vascular resistance. Interactions between distinct Ca2+ signals can serve to amplify or limit their effects on vascular resistance. Knowing the source of individual Ca2+ signals is of utmost importance for studying their physiological roles. Abnormal Ca2+ signaling mechanisms in VSMCs and ECs have been shown to contribute to excessive vascular resistance under disease conditions. Identification of the ion channels and regulatory proteins that underlie an abnormal Ca2+ signal will enable future attempts at targeting the Ca2+ signal to restore vascular resistance and blood pressure in cardiovascular disorders.

Acknowledgements.

We acknowledge Eric Cope and Corina Marziano for their constructive comments on this review article.

Funding. This work was supported by the grants from the NIH (HL121484 and HL138496) to SKS.

References.

- Abd El-Rahman RR, Harraz OF, Brett SE, Anfinogenova Y, Mufti RE, Goldman D, & Welsh DG (2013). Identification of L- and T-type Ca2+ channels in rat cerebral arteries: role in myogenic tone development. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 304(1), H58–71. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00476.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adapala RK, Talasila PK, Bratz IN, Zhang DX, Suzuki M, Meszaros JG, & Thodeti CK (2011). PKCalpha mediates acetylcholine-induced activation of TRPV4-dependent calcium influx in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 301(3), H757–765. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00142.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adebiyi A, Narayanan D, & Jaggar JH (2011). Caveolin-1 assembles type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors and canonical transient receptor potential 3 channels into a functional signaling complex in arterial smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem, 286(6), 4341–4348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.179747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adebiyi A, Thomas-Gatewood CM, Leo MD, Kidd MW, Neeb ZP, & Jaggar JH (2012). An elevation in physical coupling of type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors to transient receptor potential 3 (TRPC3) channels constricts mesenteric arteries in genetic hypertension. Hypertension, 60(5), 1213–1219. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.198820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adebiyi A, Zhao G, Narayanan D, Thomas-Gatewood CM, Bannister JP, & Jaggar JH (2010). Isoform-selective physical coupling of TRPC3 channels to IP3 receptors in smooth muscle cells regulates arterial contractility. Circ Res, 106(10), 1603–1612. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.216804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, & Large WA (2003). Synergism between inositol phosphates and diacylglycerol on native TRPC6-like channels in rabbit portal vein myocytes. J Physiol, 552(Pt 3), 789–795. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.052977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Saleh SN, & Large WA (2008). Inhibition of native TRPC6 channel activity by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in mesenteric artery myocytes. J Physiol, 586(13), 3087–3095. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amann R, & Maggi CA (1991). Ruthenium red as a capsaicin antagonist. Life Sci, 49(12), 849–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberg GC, Navedo MF, Nieves-Cintron M, Molkentin JD, & Santana LF (2007). Calcium sparklets regulate local and global calcium in murine arterial smooth muscle. J Physiol, 579(Pt 1), 187–201. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson DA, Gentry C, Moss S, & Bevan S (2008). Transient receptor potential A1 is a sensory receptor for multiple products of oxidative stress. J Neurosci, 28(10), 2485–2494. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5369-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appendino G, Harrison S, De Petrocellis L, Daddario N, Bianchi F, Schiano Moriello A, … Di Marzo V (2003). Halogenation of a capsaicin analogue leads to novel vanilloid TRPV1 receptor antagonists. Br J Pharmacol, 139(8), 1417–1424. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubdool AA, Graepel R, Kodji X, Alawi KM, Bodkin JV, Srivastava S, … Brain SD (2014). TRPA1 is essential for the vascular response to environmental cold exposure. Nat Commun, 5, 5732. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba Y, Hayashi K, Fujii Y, Mizushima A, Watarai H, Wakamori M, … Kurosaki T (2006). Coupling of STIM1 to store-operated Ca2+ entry through its constitutive and inducible movement in the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 103(45), 16704–16709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608358103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagher P, Beleznai T, Kansui Y, Mitchell R, Garland CJ, & Dora KA (2012). Low intravascular pressure activates endothelial cell TRPV4 channels, local Ca2+ events, and IKCa channels, reducing arteriolar tone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 109(44), 18174–18179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211946109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagher P, Davis MJ, & Segal SS (2011). Intravital macrozoom imaging and automated analysis of endothelial cell calcium signals coincident with arteriolar dilation in Cx40(BAC) -GCaMP2 transgenic mice. Microcirculation, 18(4), 331–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2011.00093.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball CJ, Wilson DP, Turner SP, Saint DA, & Beltrame JF (2009). Heterogeneity of L- and T-channels in the vasculature: rationale for the efficacy of combined L- and T-blockade. Hypertension, 53(4), 654–660. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.125831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang S, Yoo S, Yang TJ, Cho H, & Hwang SW (2010). Farnesyl pyrophosphate is a novel pain-producing molecule via specific activation of TRPV3. J Biol Chem, 285(25), 19362–19371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.087742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang S, Yoo S, Yang TJ, Cho H, & Hwang SW (2012). 17(R)-resolvin D1 specifically inhibits transient receptor potential ion channel vanilloid 3 leading to peripheral antinociception. Br J Pharmacol, 165(3), 683–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01568.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister JP, Adebiyi A, Zhao G, Narayanan D, Thomas CM, Feng JY, & Jaggar JH (2009). Smooth muscle cell alpha2delta-1 subunits are essential for vasoregulation by CaV1.2 channels. Circ Res, 105(10), 948–955. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister JP, Leo MD, Narayanan D, Jangsangthong W, Nair A, Evanson KW, … Jaggar JH (2013). The voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ (CaV1.2) channel C-terminus fragment is a bi-modal vasodilator. J Physiol, 591(12), 2987–2998. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.251926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista DM, Movahed P, Hinman A, Axelsson HE, Sterner O, Hogestatt ED, … Zygmunt PM (2005). Pungent products from garlic activate the sensory ion channel TRPA1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 102(34), 12248–12252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505356102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss WM (1902). On the local reactions of the arterial wall to changes of internal pressure. J Physiol, 28(3), 220–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behringer EJ, & Segal SS (2012). Spreading the signal for vasodilatation: implications for skeletal muscle blood flow control and the effects of ageing. J Physiol, 590(24), 6277–6284. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.239673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergdahl A, Gomez MF, Dreja K, Xu SZ, Adner M, Beech DJ, … Sward K (2003). Cholesterol depletion impairs vascular reactivity to endothelin-1 by reducing store-operated Ca2+ entry dependent on TRPC1. Circ Res, 93(9), 839–847. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000100367.45446.A3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, & Roderick HL (2003). Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 4(7), 517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I, Watras J, & Ehrlich BE (1991). Bell-shaped calcium-response curves of Ins(1,4,5)P3- and calcium-gated channels from endoplasmic reticulum of cerebellum. Nature, 351(6329), 751–754. doi: 10.1038/351751a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi BR, El Kouhen R, Neelands TR, Lee CH, Gomtsyan A, Raja SN, … Puttfarcken PS (2007). [3H]A-778317 [1-((R)-5-tert-butyl-indan-1-yl)-3-isoquinolin-5-yl-urea]: a novel, stereoselective, high-affinity antagonist is a useful radioligand for the human transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1) receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 323(1), 285–293. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.124305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi CP (1997). Conformation state of the ryanodine receptor and functional effects of ryanodine on skeletal muscle. Biochem Pharmacol, 53(7), 909–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biwer LA, Good ME, Hong K, Patel RK, Agrawal N, Looft-Wilson R, … Isakson BE (2017). Non-Endoplasmic Reticulum-Based Calr (Calreticulin) Can Coordinate Heterocellular Calcium Signaling and Vascular Function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorling K, Morita H, Olsen MF, Prodan A, Hansen PB, Lory P, … Jensen LJ (2013). Myogenic tone is impaired at low arterial pressure in mice deficient in the low-voltage-activated CaV 3.1 T-type Ca(2+) channel. Acta Physiol (Oxf), 207(4), 709–720. doi: 10.1111/apha.12066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]