Abstract

In order to understand the conformational behavior of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and their biological interaction networks, the detection of residual structure and long-range interactions is required. However, the large number of degrees of conformational freedom of disordered proteins require the integration of extensive sets of experimental data, which are difficult to obtain. Here, we provide a straightforward approach for the detection of residual structure and long-range interactions in IDPs under near-native conditions using solvent paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (sPRE). Our data indicate that for the general case of an unfolded chain, with a local flexibility described by the overwhelming majority of available combinations, sPREs of non-exchangeable protons can be accurately predicted through an ensemble-based fragment approach. We show for the disordered protein α-synuclein and disordered regions of the proteins FOXO4 and p53 that deviation from random coil behavior can be interpreted in terms of intrinsic propensity to populate local structure in interaction sites of these proteins and to adopt transient long-range structure. The presented modification-free approach promises to be applicable to study conformational dynamics of IDPs and other dynamic biomolecules in an integrative approach.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10858-019-00248-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Solvent paramagnetic relaxation enhancement, Intrinsically disordered proteins, Residual structure, p53, FOXO4, α-Synuclein

Introduction

The well-established structure–function paradigm has been challenged by the discovery of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) (Dyson and Wright 2005). It is suggested that about 40% of all proteins have disordered regions of 40 or more residues, with many proteins existing solely in the unfolded state (Tompa 2012; Romero et al. 1998). Although they lack stable secondary or tertiary structure elements, this large class of proteins plays a crucial role in various cellular processes (Theillet et al. 2014; Wright and Dyson 2015; van der Lee et al. 2014; Uversky et al. 2014). Disorder serves a biological role, where conformational heterogeneity granted by disordered regions enables proteins to exert diverse functions in response to various stimuli. Unlike structured proteins, which are essential for catalysis and transport, disordered proteins are crucial for regulation and signaling. Due to their intrinsic flexibility they can act as network hubs interacting with a wide range of biomolecules forming dynamic regulatory networks (Dyson and Wright 2005; Tompa 2012; Babu et al. 2011; Flock et al. 2014; Wright and Dyson 1999; Uversky 2011; Habchi et al. 2014). Given the plethora of potential interaction partners, it is not surprising that the interaction of IDPs with binding partners are often tightly regulated via and intricate ‘code’ of post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation, methylation, acetylation, and various others (Wright and Dyson 2015; Bah and Forman-Kay 2016). These proteins, and distortions in their interaction networks, for example by mutations and aberrant post-translational modifications (PTMs), are closely linked to a range of human diseases, including cancers, neurodegeneration, cardiovascular disorders and diabetes, they are currently considered difficult to study (Dyson and Wright 2005; Tompa 2012; Babu et al. 2011; Habchi et al. 2014; Metallo 2010; Uversky et al. 2008; Dyson and Wright 2004). Complications arise from the following factors: these proteins lack well-defined stable structure, they exist in a dynamic equilibrium of distinct conformational states, and the number of experimental techniques and observables renders IDP conformational characterization underdetermined (Mittag and Forman-Kay 2007; Eliezer 2009). Thus, an integration of new sets of experimental and analytical techniques are required to characterize the conformational behavior of IDPs.

Although IDPs are highly dynamic, they often contain transiently-folded regions, such as transiently populated secondary or tertiary structure, transient long-range interactions or transient aggregation (Marsh et al. 2007; Shortle and Ackerman 2001; Bernado et al. 2005; Mukrasch et al. 2007; Wells et al. 2008). These transiently-structured regions are of particular interest to study the biological function of IDPs as they can report on biologically-relevant interactions and encode biological function. Examples are aggregation, liquid–liquid phase separation, binding to folded co-factors, or modifying enzymes (Yuwen et al. 2018; Brady et al. 2017; Choy et al. 2012; Maji et al. 2009; Putker et al. 2013).

NMR spectroscopy is exceptionally well-suited to study IDPs, and in particular to detect transiently folded regions (Meier et al. 2008; Wright and Dyson 2009; Jensen et al. 2009). Several NMR observables provide atomic resolution, and ensemble-averaged information reporting on the conformational energy landscape sampled by each amino acid, including chemical shifts, residual dipolar couplings (RDCs), and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) (Dyson and Wright 2004; Eliezer 2009; Marsh et al. 2007; Shortle and Ackerman 2001; Meier et al. 2008; Gobl et al. 2014; Gillespie and Shortle 1997; Clore et al. 2007; Huang et al. 2014; Ozenne et al. 2012; Clore and Iwahara 2009; Otting 2010; Hass and Ubbink 2014; Gobl et al. 2016). RDCs, and PREs, either alone or in combination have been used successfully in recent years to characterize the conformations and long-range interactions of IDPs (Bernado et al. 2005; Ozenne et al. 2012; Dedmon et al. 2005; Bertoncini et al. 2005; Parigi et al. 2014; Rezaei-Ghaleh et al. 2018). However, both techniques rely on a modification of the IDP of interest, either by external alignment media in case of RDCs or the covalent incorporation of paramagnetic tags in the case of PREs.

We and others have proposed applications of soluble paramagnetic agents to obtain structural information by NMR without any modifications of the molecules of interest (Gobl et al. 2014; Guttler et al. 2010; Hartlmuller et al. 2016; Hocking et al. 2013; Madl et al. 2009, 2011; Respondek et al. 2007; Zangger et al. 2009; Pintacuda and Otting 2002; Bernini et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2012; Sun et al. 2011; Gong et al. 2017; Gu et al. 2014; Hartlmuller et al. 2017). The addition of soluble paramagnetic compounds leads to a concentration-dependent and therefore tunable increase of relaxation rates, the so-called paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (here denoted as solvent PRE, sPRE; also known as co-solute PRE, Fig. 1a). This effect depends on the distance of the spins of interest (e.g. 1H, 13C) to the biomolecular surface. The nuclei on the surface are affected the strongest by the sPRE effect, and this approach has been shown to correlate well with biomolecular structure in the case of proteins and RNA (Madl et al. 2009; Pintacuda and Otting 2002; Bernini et al. 2009; Hartlmuller et al. 2017). sPREs have gained popularity for structural studies of biomolecules, including in the structure determination of proteins (Madl et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2012), docking of protein complexes (Madl et al. 2011), and qualitative detection of dynamics (Hocking et al. 2013; Sun et al. 2011; Gong et al. 2017; Gu et al. 2014).

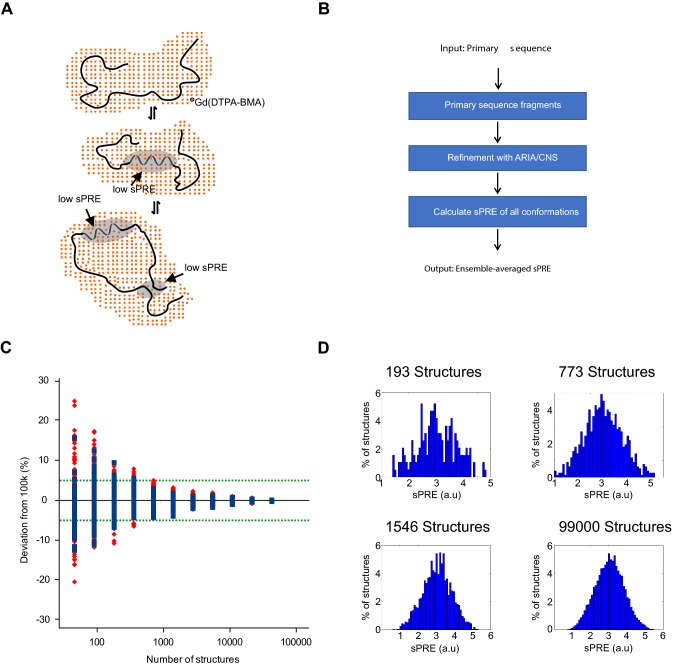

Fig. 1.

Principle and workflow for solvent PRE. a Transient secondary structures of IDPs are characteristic for protein–protein interaction sites and are therefore crucial for various cellular functions. NMR sPRE data provide quantitative and residue specific information on the solvent accessibility as the effect of paramagnetic probes such as Gd(DTPA-BMA) is distance dependent, which can be used to detect secondary structures within otherwise unfolded regions and long-range contacts within a protein. b Prediction of sPRE is based on an ensemble approach of a library of peptides. Each peptide has a length of 5 residues, and is flanked by triple-Ala on both termini (e.g. AAAXXXXXAAA, where XXXXX is a 5-mer fragment of the target primary sequence). Following water refinement using ARIA/CNS, sPRE values of all conformations are calculated and the average solvent PRE value of the ensemble is returned. c Predicted Cα sPRE (blue) and standard deviation (red) of AAAVVAVVAAA ensembles consisting of 99,000 down to 48 structural conformations. The green-dotted line indicates 5% deviation from the ensemble with 99,000 conformations. d Histograms of different ensemble sizes showing the distribution of predicted sPRE values

The most commonly used paramagnetic agent for measuring sPRE data is the inert complex Gd(DTPA-BMA) (gadolinium diethylenetriaminepenta-acetic acid bismethylamide, commercially available as ‘Omniscan’), that is known to not specifically interact on protein surfaces (Guttler et al. 2010; Madl et al. 2009, 2011; Pintacuda and Otting 2002; Wang et al. 2012; Respondek et al. 2007; Zangger et al. 2009; Göbl et al. 2010). Previously, we and others could show that sPRE data provide in-depth structural and dynamic data for IDP analysis (Madl et al. 2009; Sun et al. 2011; Gong et al. 2017; Emmanouilidis et al. 2017; Johansson et al. 2014). For example, sPRE data helped to characterize α-helical propensity in a previously postulated flexible region in the folded 42 kDa maltodextrin binding protein (Madl et al. 2009), and dynamic ligand binding to the human “survival of motor neuron” protein (Emmanouilidis et al. 2017). While writing this manuscript, and based on sPRE data for exchangeable amide protons, the Tjandra lab has shown that sPREs can detect native-like structure in denatured ubiquitin (Kooshapur et al. 2018).

Here, we present an integrative ensemble approach to predict the sPREs of IDPs. This ensemble representation is used to calculate conformationally averaged sPREs, which fit remarkably well to the experimentally-measured sPREs. We show for the disordered protein α-synuclein, and disordered regions of the proteins FOXO4 and p53 that deviation from random coil behavior can indicate intrinsic propensity to populate transient local structures and long-range interactions. In summary, this method provides a unique modification-free approach for studying IDPs, that is compatible with a wide range of NMR pulse sequences and biomolecules.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

For expression of human FOXO4TAD (residues 198–505), p53TAD (residues 1–94), pETM11-His6-ZZ cDNA and including an N-terminal TEV protease cleavage site coding for the respective proteins were transformed into E. coli BL21-DE3. To obtain 13C/15N isotope labeled protein, cells were grown for 1 day at 37 °C in minimal medium (100 mM KH2PO4, 50 mM K2HPO4, 60 mM Na2HPO4, 14 mM K2SO4, 5 mM MgCl2; pH 7.2 adjusted with HCl and NaOH with 0.1 dilution of trace element solution (41 mM CaCl2, 22 mM FeSO4, 6 mM MnCl2, 3 mM CoCl1, 2 mM ZnSO4, 0.1 mM CuCl2, 0.2 mM (NH4)6Mo7O17, 24 mM EDTA) supplemented with 2 g of 13C6H12O6 (Cambridge isotope) and 1 g of 15NH4Cl (Sigma). At an OD (600 nm) of 0.8, cells were induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranosid (IPTG) for 16 h at 20 °C. Cell pellets were harvested and sonicated in denaturing buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 2 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), 20% glycerol and 6 M urea. His6-ZZ proteins were purified using Ni–NTA agarose (QIAGEN) and eluted in 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 200 mM imidazole, 2 mM TCEP and subjected to TEV protease cleavage. Untagged proteins were then isolated by performing a second affinity purification step using Ni–NTA beads for removal of TEV and uncleaved substrate. A final exclusion chromatography purification step was performed in the buffer of interest on a gel filtration column (Superdex peptide (10/300) for p53 and Superdex 75 (16/600) for FOXO4, GE Healthcare).

α-Synuclein was expressed and purified as described (Falsone et al. 2011). Briefly, pRSETB vector containing the human AS gene was transformed into BL21 (DE3) Star Cells. 13C/15N-labeled α-synuclein was expressed in minimal medium (6.8 g/l Na2HPO3, 4 g/l KH2PO4, 0.5 g/l NaCl, 1.5 g/l (15NH4)2SO2, 4 g/l 13C glucose, 1 μg/l biotin, 1 μg/l thiamin, 100 μg/ml ampicillin, and 1 ml 1000 × microsalts). Cells were grown to an OD (600 nm) of 0.7. Protein was expressed by addition of 1 mM IPTG for 4 h. After harvesting cells were resuspended in 20 mM Tris–HCl, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, supplemented with a Complete® protease inhibitor mix (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Protein purification was then achieved using a Resource Q column and gel filtration using a Superdex 75 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden).

Generation of conformational ensembles

Conformational ensembles were generated using the ARIA/CNS software-package, comprising of 1500 random backbone conformations of all possible 5-mer peptides of the protein of interest, and flanked by triple-alanine. Every backbone conformation served as starting structure in a full-atom water refinement using ARIA (Bardiaux et al. 2012). For every refined structure the solvent PRE is calculated and the averaged solvent PRE of the central residue is stored in the database. To predict sPRE data, a previously published grid-based approach was used (Hartlmuller et al. 2016; Pintacuda and Otting 2002). Briefly, the structural model was placed in a regularly-spaced grid representing the uniformly distributed paramagnetic compound and the grid was built with a point-to-point distance of 0.5 Å and a minimum distance of 10 Å between the protein model and the outer border of the grid. Next, grid points that overlap with the protein model were removed assuming a molecular radius of 3.5 Å for the paramagnetic compound. To compute the sPRE for a given protein proton , the distance-dependent paramagnetic effect (Hartlmuller et al. 2016; Hocking et al. 2013; Pintacuda and Otting 2002) was numerically integrated over all remaining grid points according to Eq. (1):

| 1 |

where i is the index of a proton of the protein, j is the index of the grid point, di, j is the distance between the ith proton and the jth grid point and c is an arbitrary constant to scale the sPRE values (1000). Theoretical sPRE values were normalized by calculating the linear fit of experimental and predicted sPRE followed by shifting and scaling of the theoretical sPRE. To predict the solvent PRE of the entire IDP sequence, each peptide with the five matching amino acids is searched and the corresponding solvent PRE values are combined. sPRE data of the two N- and C-terminal residues were not predicted in this setup. All scripts and sample runs can be obtained downloaded from the homepage of the authors (https://mbbc.medunigraz.at/forschung/forschungseinheiten-und-gruppen/forschungsgruppe-tobias-madl/software/).

NMR experiments

The setup of sPRE measurements using NMR spectroscopy was performed as described previously (Hartlmuller et al. 2016, 2017). To obtain sPRE data, a saturation-based approach was used. The 1H-R1 relaxation rates were determined by a saturation-recovery scheme followed by a read-out experiment such as a 1H, 15N HSQC, 1H, 13C HSQC or a 3D CBCA(CO)NH experiment. The read-out experiments were combined with the saturation-recovery scheme in a Pseudo-3D (HSQCs) or Pseudo-4D [CBCA(CO)NH] experiment, with the recovery time as an additional dimension. The CBCA(CO)NH was recorded using non-uniform sampling. Alternatively, 1H-R2 relaxation rates can be as described (Clore and Iwahara 2009).

A 7.5 ms 1H trim pulse followed by a gradient was applied for proton saturation. During the recovery, ranging from several milliseconds up to several seconds, z-magnetization is built up. The individual recovery delays are applied in an interleaved manner, with short and long delays occurring in alternating fashion. For every 1H-R1 measurement 10 delay times were recorded and for error estimation, at 1 delay time was recorded as a duplicate.

Measurement of 1H-R1 rates were repeated for increasing concentrations of the relaxation-enhancing Gd(DTPA-BMA)/Omniscan (GE Healthcare, Vienna, Austria) and the solvent PRE was obtained as the average change of the proton R1 rate per concentration of the paramagnetic agent. After each addition of Gd(DTPA-BMA), the recovery delays were shortened such that for the longest delay all NMR signals were sufficiently recovered. The interscan delay was set to 50 ms, as the saturation-recovery scheme does not rely on an equilibrium z-magnetization at the start of each scan. All NMR samples contained 10% 2H2O. Spectra were processed using NMRPipe and analyzed with the NMRView and CcpNmr Analysis software packages (Johnson 2004; Delaglio et al. 1995; Skinner et al. 2016).

Measurement of sPRE data used in this study

Assignment of p53TAD was achieved using HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH and HCAN spectra and analyzed using ccpNMR (Skinner et al. 2016). sPRE data of 300 µM samples of uniformly 13C/15N labeled p53TAD was measured on a 600 MHz Bruker Avance Neo NMR spectrometer equipped with a TXI probehead at 298 K in a buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 0.04% sodium azide, pH 7.5. 1H-R1 rates of 1HN, Hα and Hβ were determined using 1H,13C HSQC and 1H, 15N HSQC as read-out spectra (4/4 scans, 200/128 complex points in F2). For assignment of α-synuclein, previously reported chemical shifts were obtained from the BMRB (accession code 6968) and the assignment was confirmed using HNCACB and CBCA(CO)NH spectra. 1H-R1 rates of aliphatic protons and amide protons of a 100 µM sample (50 mM bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino-tris(hydroxymethyl)methane (bis–Tris), 20 mM NaCl, 3 mM sodium azide, pH 6.8) were determined using 1H, 13C HSQC and 1H, 15N HSQC read-out spectra, respectively, at 282 K in the presence of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 mM Gd(DTPA-BMA). For assignment of FOXO4TAD HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH and HCAN spectra were recorded and assigned using ccpNMR (Skinner et al. 2016). Measurements of 13C, 15N labeled FOXO4TAD at 390 µM in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.8, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT were performed on a 600 MHz magnet (Oxford Instruments) equipped with an AV III console and cryo TCI probe head (Bruker Biospin). Pseudo-4D CBCA(CO)NH spectra served as read-out for 1H-R1 rates and were recorded on a 250 µM sample on a 900 MHz Bruker Avance III spectrometer equipped with a TCI cryoprobe using non-uniform sampling (4 scans, 168/104 complex points in F1 (13C)/F2 (15N) sampled with 13.7% resulting a total number of 600 complex points). Spectra were processed using hmsIST/NMRPipe (Hyberts et al. 2014).

Analysis of NMR data

sPRE data of the model proteins was analyzed as described previously. Briefly, peak intensities were extracted using nmrglue python package and fitted to a mono-exponential build up curve the SciPy python package and Eq. (2).

| 2 |

where I(t) is the peak intensity of the saturation-recovery experiment, t is the recovery delay, A is the amplitude of the z-magnetization build-up, C is the plateau of the curve and R1 is the longitudinal relaxation rate. Duplicate recovery delays were used to determine the error for the fitted rates R1.

| 3 |

where N is the number of peaks in the spectrum, i is the index of the peak, and δi is the difference of the duplicates for the ith peak. The error of the rates R1 was then obtained using a Monte Carlo-type resampling strategy. The solvent PRE is obtained by performing a weighted linear regression using the equation

| 4 |

where c is the concentration of Gd(DTPA-BMA), R1(c) is the fitted R1 rate at the present of Gd(DTPA-BMA) with a concentration c, R01 is the R1 in the absence of Gd(DTPA-BMA) and sPRE is the slope and the desired sPRE value. For the weighted linear regression, the previously determined errors ∆ R1 for R1 was used, and the error on the concentration c was neglected.

Results and discussion

To detect transient structural elements in IDPs, an efficient back-calculation of sPREs of IDPs is essential. Whereas back-calculation of sPREs is relatively straightforward for folded rigid structures and can be carried out efficiently using a grid-based approach by integration of the solvent environment (Hartlmuller et al. 2016, 2017), this approach fails in the case of highly conformationally heterogeneous IDPs. In our approach, sPREs are best represented as an average sPRE of an ensemble. NMR observables and nuclear spin relaxation phenomena, including sPREs, directly sense chemical exchange through the distinct magnetic environments that nuclear spins experience while undergoing those exchange processes. The effects of the dynamic exchange on the NMR signals can be described by the McConnell Equations (Mcconnell 1958) In the case of a two-site exchange process, and assuming that the exchange rate is faster than the difference in the sPREs observed in both states, the observed sPRE is a linear, population-weighted average of the sPRE observed in both states, as seen for covalent paramagnetic labels (Clore and Iwahara 2009). Moreover, the correlation time for relaxation is assumed to be faster than the exchange time among different conformations within the IDP (Jensen et al. 2014; Iwahara and Clore 2010). The effective correlation time for longitudinal relaxation depends on the rotational correlation time of the biomolecule, the electron relaxation time and the lifetime of the rotationally correlated complex of the biomolecule and the paramagnetic agent (Madl et al. 2009; Eletsky et al. 2003). For ubiquitin, the effective correlation time for longitudinal relaxation was found to be in the sub-ns time scale (Pintacuda and Otting 2002), whereas that conformational exchange in IDPs typically appears at slower timescales (Jensen et al. 2014).

Calculating the average of sPREs over an ensemble of protein conformations presents serious practical difficulties that affect both the accuracy and the portability of the calculation. For RDCs it has been shown that convergence to the average requires an unmanageably large number of structures (e.g. 100,000 models for a protein with 100 amino acids), and that the convergence strictly depends on the length of the protein (Bernado et al. 2005; Nodet et al. 2009). To simplify the back-calculation of sPREs we use a strategy proposed for RDCs by the Forman-Kay and Blackledge groups (Marsh et al. 2008; Huang et al. 2013).

To back-calculate the sPRE from a given primary sequence of an IDP we generated fragments of five amino acids of the sequence of interest and flanked them with triple-alanine sequences at the N- and C-termini to simulate the presence of upstream/downstream amino acids (Fig. 1b). An ensemble of structures for these sequences is then generated using ARIA/CNS including water refinement (Bardiaux et al. 2012). To predict the solvent PRE of the entire IDP, the peptide with the five matching residues is searched and the corresponding solvent PREs averaged for the entire conformational ensemble are returned. This approach is highly parallelizable and dramatically reduces the computational effort compared to simulating the conformations of the full-length IDP.

To determine the number of conformers necessary to converge the back-calculated sPRE of the defined 11-mers, we generated an ensemble of 100,000 structures for a 11-mer AAAVVAVVAAA peptide using ARIA/CNS (Bardiaux et al. 2012) and back-calculated the sPRE for subsets with decreasing number of structures. We find that 1500 conformers are sufficient to reproduce the sPRE with a deviation compared to the maximum ensemble below 5% (Fig. 1c, d).

Back-calculation of the sPRE by fast grid-based integration has some advantages compared to alternative approaches relying on surface accessibility (Kooshapur et al. 2018). First, sPREs can be obtained for atoms without any surface accessibility in grid-based integration approaches as they still take into account the distance-dependent paramagnetic effect. This is expected to provide more accurate predictions for regions with a high degree of bulky side chains or transient folding.

To validate our computational approach, we recorded several sets of experimental 1H-sPREs for the disordered regions of the human proteins FOXO4, p53, and α-synuclein. Similar to many other transcription factors, p53 and FOXO4 are largely disordered outside their DNA binding domains.

In order to demonstrate that surface accessibility data can be obtained for a challenging IDP, we recorded sPRE data for the 307 residue transactivation domain of FOXO4. The FOXO4 transcription factor is a member of the forkhead box O family of proteins that share a highly conserved DNA-binding motif, the forkhead box domain (FH). The FH domain is surrounded by large N- and C-terminal intrinsically disordered regions which are essential for the regulation of FOXO function (Weigel and Jackle 1990). FOXOs control a plethora of cellular functions, such as cell growth, survival, metabolism and oxidative stress, by regulating the expression of hundreds of target genes (Burgering and Medema 2003; Hornsveld et al. 2018). Expression and activity of FOXOs are tightly controlled by PTMs such as phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation and ubiquitination, and these modifications impact on FOXO stability, sub-cellular localization and transcriptional activity (Essers et al. 2004; de Keizer et al. 2010; van den Berg et al. 2013). Because of their anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic functions, FOXOs have been considered as bona fide tumor suppressors. However, FOXOs can also support tumor development and progression by maintaining cellular homeostasis, facilitating metastasis and inducing therapeutic resistance (Hornsveld et al. 2018). Thus, targeting FOXO activity might hold promise in cancer therapy.

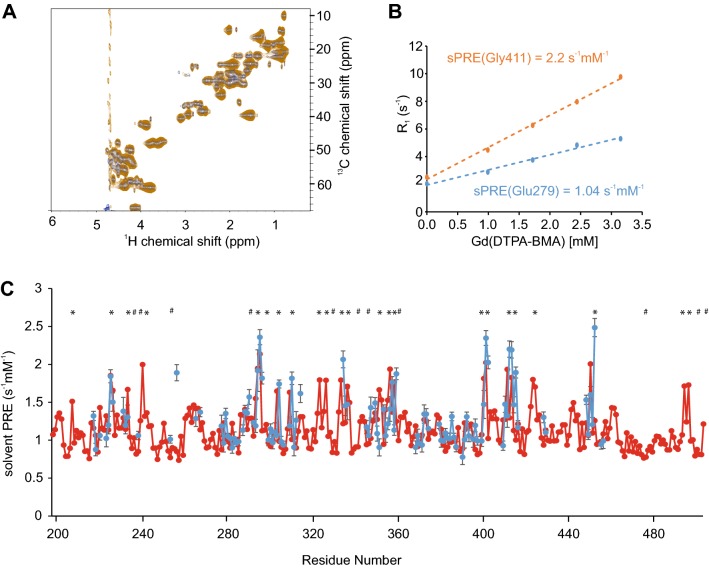

The C-terminal FOXO4 transactivation domain has been suggested to be largely disordered and to be the binding site for many cofactors. Because it also harbors most of the post-translational modifications (Putker et al. 2013; Burgering and Medema 2003; Hornsveld et al. 2018; Bourgeois and Madl 2018), we set off to study this biologically important domain using our sPRE approach. 1H,15N and 1H, 13C HSQC NMR spectra of FOXO4TAD are of high quality and showed no detectable 1H, 13C, or 15N chemical shift changes between the spectra recorded in the absence or presence of Gd(DTPA-BMA) (Fig. 2a). sPRE data of FOXO4 had to be recorded in pseudo-4D saturation-recovery CBCA(CO)NH spectra due to the severe signal overlap observed in the 2D HSQC spectra. It should be noted that any kind of NMR experiment could be combined in principle with a sPRE saturation recovery measurement block in order to obtain 1H- or 13C sPRE data. The sPRE data of FOXO4TAD yield differential solvent accessibilities in a residue-specific manner (Fig. 2b, c). Hα atoms located in regions rich in bulky residues are showing lower sPREs and Hα atoms located in more exposed glycine-rich regions display higher sPREs. Hβ sPRE data was obtained for a limited number of residues and shows overall elevated sPREs due to the higher degree of exposure and a reasonable agreement of predicted and experimental data (Supporting Fig. 1). A comparison of the predicted sPRE data with a bioinformatics bulkiness prediction shows that some features are reproduced by the bioinformatics prediction (Supporting Fig. 2A). However, the experimental sPRE is better described by our approach. Strikingly, the predicted sPRE pattern reproduces the experimental sPRE pattern exceptionally well, indicating that the FOXO4TAD is largely disordered and does not adopt any stable or transient tertiary structure in the regions for which sPRE data could be obtained.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of predicted and measured solvent PRE of FOXO4TAD. a Overlay of 1H,13C HSQC spectra, with full recovery time of a 390 µM 13C,15N labeled FOXO4TAD sample in the absence (blue) and presence of 3.25 mM Gd(DTPA-BMA) (orange). b1H-R1 rates of two selected residues of FOXO4TAD at different Gd(DTPA-BMA) concentrations. c Predicted (red) and experimentally-determined (blue) solvent PRE values using CBCA(CO)NH as readout spectrum, of assigned Hα peaks of FOXO4TAD. Experimental sPRE values are calculated by fitting the data with a linear regression equation. Predicted sPRE values are based on the previously described ensemble approach. Residues with bulky side chains (Phe, Trp, Tyr) are labeled with #, and exposed glycine residues are labeled with * (see Supporting Fig. 2A for a bulkiness profile). Errors of the measured 1H-R1 rates were calculated using a Monte Carlo-type resampling strategy and are shown in the diagram as error bars

In order to demonstrate that surface accessibility data can be obtained for a IDP with potential formation of transient local secondary structure we recorded sPRE data for the 94-residue transactivation domain of p53. p53 is a homo-tetrameric transcription factor composed of an N-terminal trans-activation domain, a proline-rich domain, a central DNA-binding domain followed by a tetramerization domain and the C-terminal negative regulatory domain. p53 is involved in the regulation of more than 500 target genes and thereby controls a broad range of cellular processes, including apoptosis, metabolic adaptation, DNA repair, cell cycle arrest, and senescence (Vousden and Prives 2009). The disordered N-terminal p53 transactivation domain (p53TAD) is a key interaction motif for regulatory protein–protein interactions (Fernandez-Fernandez and Sot 2011): it possesses two binding motifs with α-helical propensity, named p53TAD1 (residues 17–29) and p53TAD2 (residues 40–57). These two motifs act independently or in combination in order to allow p53 to bind to several proteins regulating either p53 stability or transcriptional activity (Shan et al. 2012; Jenkins et al. 2009; Rowell et al. 2012). Because of its pro-apoptotic function, p53 is recognized as tumor suppressor, and is found mutated in more than half of all human cancers affecting a wide variety of tissues (Olivier et al. 2010). Within this biological and disease context the N-terminal p53-TAD plays a key role: it mediates the interaction with folded co-factors, and comprises most of the regulatory phosphorylation sites.

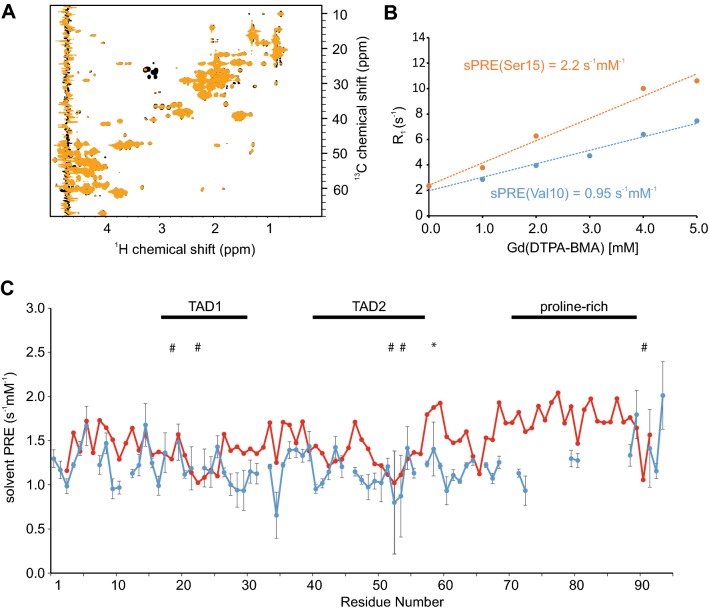

1H, 15N and 1H, 13C HSQC NMR spectra recorded of p53TAD are of high quality and showed no detectable 1H, 13C, or 15N chemical shift changes between the spectra recorded in the absence or presence of Gd(DTPA-BMA) (Fig. 3a, Supporting Fig. 3A). The sPRE data of p53TAD display differential solvent accessibilities in a residue-specific manner: due to different excluded volumes for the paramagnetic agent Hα atoms located in regions rich in bulky residues show lower sPREs and Hα atoms located in more exposed regions show higher sPREs (Fig. 3b, c, Supporting Fig. 2B).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of predicted and measured solvent PRE of p53TAD. a Overlay of 1H, 13C HSQC read-out spectra, with full recovery time of a 300 µM 13C, 15N labeled p53TAD in absence (black) and presence of 5 mM Gd(DTPA-BMA) (orange). b Gd(DTPA-BMA)-concentration-dependent R1 rates of two selected residues. c Diagram showing predicted (red) and measured (blue) solvent PRE values of each Hα atom of p53TAD. Experimental sPRE values are calculated by fitting the data with a linear regression equation. Predicted sPRE values are based on the previously described ensemble approach. Regions binding to co-factors (TAD1, TAD2) and the proline rich region are labeled. Residues with bulky side chains (Phe, Trp, Tyr) are labeled with #, and exposed glycine residues are labeled with * (see Supporting Fig. 2B for a bulkiness profile). Errors of the measured 1H-R1 rates were calculated using a Monte Carlo-type resampling strategy and are shown in the diagram as error bars

sPRE data of structured proteins are often recorded for amide protons. However, chemical exchange of the amide proton with fast-relaxing water solvent protons might lead to an increase of the experimental sPRE, as has been observed for the disordered linker regions in folded proteins and in RNA (Hartlmuller et al. 2017; Gobl et al. 2017). For imino and amino protons of the UUCG tetraloop RNA and a GTP class II aptamer, for example, the increase of 1H-R1 rates is larger at small concentrations of the paramagnetic compound, and becomes linear at higher concentrations. Thus, we decided to focus here on experimental and back-calculated sPRE data of Hα protons. Nevertheless, 1HN-sPREs are shown for comparison in the supporting information (Supporting Fig. 4A).

Comparison of the back-calculated and experimental p53TAD-sPREs shows that several regions within p53TAD yield lower sPREs than predicted, indicating that p53TAD populates residual local structure or shows long-range tertiary interactions. In line with this, 15N NMR relaxation data and 13C secondary chemical shift data display reduced flexibility of p53TAD and transient α-helical structure (Supporting Fig. 5). This is in line with previous studies which found that the p53TAD1 domain adopts a transiently populated α-helical structure formed by residues Phe19-Leu26 and that the p53TAD2 domain adopts a transiently populated turn-like structure formed by residues Met40-Met44 and Asp48-Trp53 (Lee et al. 2000). Given that p53TAD has been reported to interact with several co-factors, our data indicate that sPRE data can indeed provide important insight into the residual structure of this key interaction motif (Bourgeois and Madl 2018; Raj and Attardi 2017).

In order to address the question of whether sPREs can be used to detect transient long-range interactions in disordered proteins we recorded 1H sPRE data for the 141-residue IDP α-synuclein using 1H, 13C and 1H, 15N, HSQC-based saturation recovery experiments at increasing concentrations of Gd(DTPA-BMA). α-Synuclein controls the assembly of presynaptic vesicles in neurons and is required for the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine (Burre et al. 2010). The aggregation of α-synuclein into intracellular amyloid inclusions coincides with the death of dopaminergic neurons, and therefore constitutes a pathologic signature of synucleinopathies such as Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and multiple system atrophy (Alafuzoff and Hartikainen 2017). Formation of transient long-range interactions has been proposed to protect α-synuclein from aggregation.

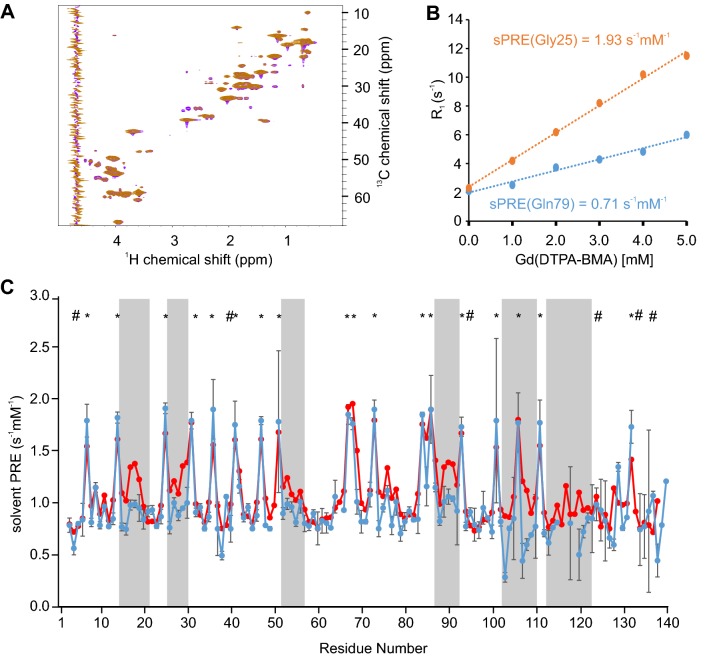

1H, 15N and 1H, 13C HSQC NMR spectra of α-synuclein are of high quality and showed no detectable 1H, 13C, or 15N chemical shift changes between the spectra recorded in the absence or presence of 5 mM Gd(DTPA-BMA) (Fig. 4a). The sPRE data of α-synuclein display variable solvent accessibilities in a residue-specific manner (Fig. 4b), with Hα atoms located in regions rich in bulky residues showing lower sPREs and Hα atoms located in more exposed regions showing higher sPREs (see also Supporting Fig. 2C for a comparison with the bioinformatics bulkiness profile and Supporting Fig. 4B for the 1HN sPRE data). Thus, the sPRE value provides local structural information about the disordered ensemble. Strikingly, we observed decreased sPREs, and therefore lower surface accessibility, in several regions, such as between residues 15–20, 26–30, 52–57, 74–79, 87–92, 102–110, and 112–121, respectively (Fig. 4c). Comparison of these regions with recently–published ensemble modeling using extensive sets of RDC and PRE data (Salmon et al. 2010) shows that the previously–observed transient intra-molecular long-range contacts involving mainly the regions 1–40, 70–90, and 120–140 within α-synuclein are reproduced by the sPRE data. Thus, sPRE data are highly sensitive to low populations of residual structure in disordered proteins.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of predicted and measured solvent PRE of α-synuclein. a Overlay of 1H, 13C HSQC Read-out spectra, with full recovery time of 100 µM 13C,15N labeled α-synuclein in absence (violet) and presence of 5 mM Gd(DTPA-BMA) (orange). b Linear fit of relaxation rate 1H-R1 and Gd(DTPA-BMA) concentration of two selected residues of α-synuclein. c Predicted (red) and experimentally determined (blue) sPRE values from 1H,13C HSQC read-out spectra. Regions of strong variations between predicted and measured sPRE values are highlighted by grey boxes. Experimental sPRE values are calculated by fitting the data with a linear regression equation. Predicted sPRE values are based on the previously described ensemble approach. Residues with bulky side chains (Phe, Trp, Tyr) are labeled with #, and exposed glycine residues are labeled with * (see Supporting Fig. 2C for a bulkiness profile). Errors of the measured 1H-R1 rates were calculated using a Monte Carlo-type resampling strategy and are shown in the diagram as error bars

Conclusions

In order to understand the conformational behavior of IDPs and their biological interaction networks, the detection of residual structure and long-range interactions is required. The large number of degrees of conformational freedom of IDPs require extensive sets of experimental data. Here, we provide a straightforward approach for the detection of residual structure and long-range interactions in IDPs and show that sPRE data contribute important and easily-accessible restraints for the investigation of IDPs. Our data indicate that for the general case of an unfolded chain with a local flexibility described by the overwhelming majority of available combinations, sPREs can be accurately predicted through our approach. It can be envisaged that a database of all potential combinations of the 20 amino acids within the central 5-mer peptide can be generated in the future. Nevertheless, generation of sPRE datasets for the entire 3.2 million possible combinations is beyond the current computing capabilities.

Our approach promises to be a straightforward screening tool to exclude potential specific interactions of the soluble paramagnetic agent with IDPs and to guide positioning of covalent paramagnetic spin labels which are often used to detect long-range interactions within IDPs (Gobl et al. 2014; Clore and Iwahara 2009; Otting 2010; Jensen et al. 2014). Paramagnetic spin labels are preferable placed close to, but not within regions involved in transient interactions in order to avoid potential interference of the spin label with weak and dynamic interactions.

In summary, we used three highly disease-relevant biological model systems for determining the solvent accessibility information provided by sPREs. This information can be easily determined experimentally and agrees well with the sPREs predicted for non-exchangeable protons using our grid-based approach. Our method proves to be highly sensitive to low populations of residual structure and long-range contacts in disordered proteins. This approach can be easily combined with ensemble-based calculations such as implemented in flexible-meccano/ASTEROIDS (Mukrasch et al. 2007; Nodet et al. 2009), Xplor-NIH (Kooshapur et al. 2018), or other programs (Estana et al. 2019) to interpret residual structure of IDPs quantitatively and in combination with complementary restraints obtained from RDCs and PREs. In particular for IDP ensemble calculations relying on sPRE data it is essential to exclude specific interactions of the paramagnetic agent with the IDP of interest which would lead to an enhanced experimental sPRE compared to the predicted sPRE.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Austrian Science Fund (FWF). This research was supported by the Austrian Science Foundation (P28854, I3792, DK-MCD W1226 to TM), the President’s International Fellowship Initiative of CAS (No. 2015VBB045, to TM), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31450110423, to TM), the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG: 864690, 870454), the Integrative Metabolism Research Center Graz, the Austrian infrastructure program 2016/2017, the Styrian government (Zukunftsfonds) and BioTechMed/Graz. E.S. was trained within frame of the PhD program Molecular Medicine. We thank Dr. Vanessa Morris for carefully reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Christoph Hartlmüller and Emil Spreitzer are the shared first authors.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alafuzoff I, Hartikainen P. Alpha-synucleinopathies. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017;145:339–353. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-802395-2.00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu MM, van der Lee R, de Groot NS, Gsponer J. Intrinsically disordered proteins: regulation and disease. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:432–440. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bah A, Forman-Kay JD. Modulation of intrinsically disordered protein function by post-translational modifications. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:6696–6705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.695056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardiaux B, Malliavin T, Nilges M. ARIA for solution and solid-state NMR. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;831:453–483. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-480-3_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernado P, Bertoncini CW, Griesinger C, Zweckstetter M, Blackledge M. Defining long-range order and local disorder in native alpha-synuclein using residual dipolar couplings. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17968–17969. doi: 10.1021/ja055538p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernini A, Venditti V, Spiga O, Niccolai N. Probing protein surface accessibility with solvent and paramagnetic molecules. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2009;54:278–289. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2008.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoncini CW, et al. Release of long-range tertiary interactions potentiates aggregation of natively unstructured alpha-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1430–1435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407146102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois B, Madl T. Regulation of cellular senescence via the FOXO4-p53 axis. FEBS Lett. 2018;592:2083–2097. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady JP, et al. Structural and hydrodynamic properties of an intrinsically disordered region of a germ cell-specific protein on phase separation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E8194–E8203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706197114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgering BM, Medema RH. Decisions on life and death: FOXO Forkhead transcription factors are in command when PKB/Akt is off duty. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:689–701. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1202629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burre J, et al. Alpha-synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science. 2010;329:1663–1667. doi: 10.1126/science.1195227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy MS, Page R, Peti W. Regulation of protein phosphatase 1 by intrinsically disordered proteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:969–974. doi: 10.1042/BST20120094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clore GM, Iwahara J. Theory, practice, and applications of paramagnetic relaxation enhancement for the characterization of transient low-population states of biological macromolecules and their complexes. Chem Rev. 2009;109:4108–4139. doi: 10.1021/cr900033p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clore GM, Tang C, Iwahara J. Elucidating transient macromolecular interactions using paramagnetic relaxation enhancement. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:603–616. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Keizer PL, et al. Activation of forkhead box O transcription factors by oncogenic BRAF promotes p21cip1-dependent senescence. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8526–8536. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedmon MM, Lindorff-Larsen K, Christodoulou J, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM. Mapping long-range interactions in alpha-synuclein using spin-label NMR and ensemble molecular dynamics simulations. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:476–477. doi: 10.1021/ja044834j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F, et al. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Unfolded proteins and protein folding studied by NMR. Chem Rev. 2004;104:3607–3622. doi: 10.1021/cr030403s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eletsky A, Moreira O, Kovacs H, Pervushin K. A novel strategy for the assignment of side-chain resonances in completely deuterated large proteins using 13C spectroscopy. J Biomol NMR. 2003;26:167–179. doi: 10.1023/A:1023572320699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliezer D. Biophysical characterization of intrinsically disordered proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouilidis L, et al. Allosteric modulation of peroxisomal membrane protein recognition by farnesylation of the peroxisomal import receptor PEX19. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14635. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essers MA, et al. FOXO transcription factor activation by oxidative stress mediated by the small GTPase Ral and JNK. EMBO J. 2004;23:4802–4812. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estana A, et al. Realistic ensemble models of intrinsically disordered proteins using a structure-encoding coil database. Structure. 2019;27:381–391e2. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2018.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falsone SF, et al. The neurotransmitter serotonin interrupts alpha-synuclein amyloid maturation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814:553–561. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Fernandez MR, Sot B. The relevance of protein-protein interactions for p53 function: the CPE contribution. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2011;24:41–51. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flock T, Weatheritt RJ, Latysheva NS, Babu MM. Controlling entropy to tune the functions of intrinsically disordered regions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;26:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JR, Shortle D. Characterization of long-range structure in the denatured state of staphylococcal nuclease. I. Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement by nitroxide spin labels. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:158–169. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobl C, Madl T, Simon B, Sattler M. NMR approaches for structural analysis of multidomain proteins and complexes in solution. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2014;80:26–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobl C, et al. Increasing the chemical-shift dispersion of unstructured proteins with a covalent lanthanide shift reagent. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:14847–14851. doi: 10.1002/anie.201607261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobl C, et al. Flexible IgE epitope-containing domains of Phl p 5 cause high allergenic activity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:1187–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göbl C, Kosol S, Stockner T, Rückert HM, Zangger K. Solution structure and membrane binding of the toxin fst of the par addiction module. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6567–6575. doi: 10.1021/bi1005128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z, Gu XH, Guo DC, Wang J, Tang C. Protein structural ensembles visualized by solvent paramagnetic relaxation enhancement. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2017;56:1002–1006. doi: 10.1002/anie.201609830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu XH, Gong Z, Guo DC, Zhang WP, Tang C. A decadentate Gd(III)-coordinating paramagnetic cosolvent for protein relaxation enhancement measurement. J Biomol NMR. 2014;58:149–154. doi: 10.1007/s10858-014-9817-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttler T, et al. NES consensus redefined by structures of PKI-type and Rev-type nuclear export signals bound to CRM1. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1367–1376. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habchi J, Tompa P, Longhi S, Uversky VN. Introducing protein intrinsic disorder. Chem Rev. 2014;114:6561–6588. doi: 10.1021/cr400514h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartlmuller C, Gobl C, Madl T. Prediction of protein structure using surface accessibility data. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:11970–11974. doi: 10.1002/anie.201604788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartlmuller C, et al. RNA structure refinement using NMR solvent accessibility data. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5393. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05821-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hass MA, Ubbink M. Structure determination of protein-protein complexes with long-range anisotropic paramagnetic NMR restraints. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2014;24:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking HG, Zangger K, Madl T. Studying the structure and dynamics of biomolecules by using soluble paramagnetic probes. ChemPhysChem. 2013;14:3082–3094. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201300219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornsveld M, Dansen TB, Derksen PW, Burgering BMT. Re-evaluating the role of FOXOs in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018;50:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JR, Ozenne V, Jensen MR, Blackledge M. Direct prediction of NMR residual dipolar couplings from the primary sequence of unfolded proteins. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:687–690. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JR, et al. Transient electrostatic interactions dominate the conformational equilibrium sampled by multidomain splicing factor U2AF65: a combined NMR and SAXS study. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:7068–7076. doi: 10.1021/ja502030n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyberts SG, Arthanari H, Robson SA, Wagner G. Perspectives in magnetic resonance: NMR in the post-FFT era. J Magn Reson. 2014;241:60–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwahara J, Clore GM. Structure-independent analysis of the breadth of the positional distribution of disordered groups in macromolecules from order parameters for long, variable-length vectors using NMR paramagnetic relaxation enhancement. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13346–13356. doi: 10.1021/ja1048187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins LM, et al. Two distinct motifs within the p53 transactivation domain bind to the Taz2 domain of p300 and are differentially affected by phosphorylation. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1244–1255. doi: 10.1021/bi801716h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MR, et al. Quantitative determination of the conformational properties of partially folded and intrinsically disordered proteins using NMR dipolar couplings. Structure. 2009;17:1169–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MR, Zweckstetter M, Huang JR, Blackledge M. Exploring free-energy landscapes of intrinsically disordered proteins at atomic resolution using NMR spectroscopy. Chem Rev. 2014;114:6632–6660. doi: 10.1021/cr400688u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson H, et al. Specific and nonspecific interactions in ultraweak protein-protein associations revealed by solvent paramagnetic relaxation enhancements. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:10277–10286. doi: 10.1021/ja503546j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA. Using NMRView to visualize and analyze the NMR spectra of macromolecules. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;278:313–352. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-809-9:313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooshapur H, Schwieters CD, Tjandra N. Conformational ensemble of disordered proteins probed by solvent paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (sPRE) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57:13519–13522. doi: 10.1002/anie.201807365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, et al. Local structural elements in the mostly unstructured transcriptional activation domain of human p53. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29426–29432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madl T, Bermel W, Zangger K. Use of relaxation enhancements in a paramagnetic environment for the structure determination of proteins using NMR spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:8259–8262. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madl T, Bermel W, Zangger K. Use of relaxation enhancements in a paramagnetic environment for the structure determination of proteins using NMR spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:8259–8262. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madl T, Guttler T, Gorlich D, Sattler M. Structural analysis of large protein complexes using solvent paramagnetic relaxation enhancements. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:3993–3997. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maji SK, et al. Functional amyloids as natural storage of peptide hormones in pituitary secretory granules. Science. 2009;325:328–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1173155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JA, et al. Improved structural characterizations of the drkN SH3 domain unfolded state suggest a compact ensemble with native-like and non-native structure. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:1494–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JA, Baker JM, Tollinger M, Forman-Kay JD. Calculation of residual dipolar couplings from disordered state ensembles using local alignment. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7804–7805. doi: 10.1021/ja802220c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcconnell HM. Reaction rates by nuclear magnetic resonance. J Chem Phys. 1958;28:430–431. doi: 10.1063/1.1744152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meier S, Blackledge M, Grzesiek S. Conformational distributions of unfolded polypeptides from novel NMR techniques. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:052204. doi: 10.1063/1.2838167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metallo SJ. Intrinsically disordered proteins are potential drug targets. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.06.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittag T, Forman-Kay JD. Atomic-level characterization of disordered protein ensembles. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukrasch MD, et al. Highly populated turn conformations in natively unfolded tau protein identified from residual dipolar couplings and molecular simulation. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5235–5243. doi: 10.1021/ja0690159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nodet G, et al. Quantitative description of backbone conformational sampling of unfolded proteins at amino acid resolution from NMR residual dipolar couplings. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:17908–17918. doi: 10.1021/ja9069024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001008. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otting G. Protein NMR using paramagnetic ions. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010;39:387–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozenne V, et al. Flexible-meccano: a tool for the generation of explicit ensemble descriptions of intrinsically disordered proteins and their associated experimental observables. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1463–1470. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parigi G, et al. Long-range correlated dynamics in intrinsically disordered proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:16201–16209. doi: 10.1021/ja506820r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintacuda G, Otting G. Identification of protein surfaces by NMR measurements with a paramagnetic Gd(III) chelate. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:372–373. doi: 10.1021/ja016985h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintacuda G, Otting G. Identification of protein surfaces by NMR measurements with a pramagnetic Gd(III) chelate. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:372–373. doi: 10.1021/ja016985h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putker M, et al. Redox-dependent control of FOXO/DAF-16 by transportin-1. Mol Cell. 2013;49:730–742. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj N, Attardi LD. The transactivation domains of the p53 protein. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017;7:a026047. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Respondek M, Madl T, Gobl C, Golser R, Zangger K. Mapping the orientation of helices in micelle-bound peptides by paramagnetic relaxation waves. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5228–5234. doi: 10.1021/ja069004f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Respondek M, Madl T, Gobl C, Golser R, Zangger K. Mapping the orientation of helices in micelle-bound peptides by paramagnetic relaxation waves. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5228–5234. doi: 10.1021/ja069004f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei-Ghaleh N, et al. Local and global dynamics in intrinsically disordered synuclein. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018;57:15262–15266. doi: 10.1002/anie.201808172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero P, et al. Thousands of proteins likely to have long disordered regions. Pac Symp Biocomput. 1998;3:437–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell JP, Simpson KL, Stott K, Watson M, Thomas JO. HMGB1-facilitated p53 DNA binding occurs via HMG-Box/p53 transactivation domain interaction, regulated by the acidic tail. Structure. 2012;20:2014–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon L, et al. NMR characterization of long-range order in intrinsically disordered proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8407–8418. doi: 10.1021/ja101645g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan B, Li DW, Bruschweiler-Li L, Bruschweiler R. Competitive binding between dynamic p53 transactivation subdomains to human MDM2 protein: implications for regulating the p53. MDM2/MDMX interaction. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:30376–30384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.369793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortle D, Ackerman MS. Persistence of native-like topology in a denatured protein in 8 M urea. Science. 2001;293:487–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1060438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner SP, et al. CcpNmr AnalysisAssign: a flexible platform for integrated NMR analysis. J Biomol NMR. 2016;66:111–124. doi: 10.1007/s10858-016-0060-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Friedman JI, Stivers JT. Cosolute paramagnetic relaxation enhancements detect transient conformations of human uracil DNA glycosylase (hUNG) Biochemistry. 2011;50:10724–10731. doi: 10.1021/bi201572g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theillet FX, et al. Physicochemical properties of cells and their effects on intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) Chem Rev. 2014;114:6661–6714. doi: 10.1021/cr400695p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa P. Intrinsically disordered proteins: a 10-year recap. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky VN. Intrinsically disordered proteins from A to Z. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:1090–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky VN, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Intrinsically disordered proteins in human diseases: introducing the D2 concept. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:215–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky VN, et al. Pathological unfoldomics of uncontrolled chaos: intrinsically disordered proteins and human diseases. Chem Rev. 2014;114:6844–6879. doi: 10.1021/cr400713r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg MC, et al. The small GTPase RALA controls c-Jun N-terminal kinase-mediated FOXO activation by regulation of a JIP1 scaffold complex. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:21729–21741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.463885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Lee R, et al. Classification of intrinsically disordered regions and proteins. Chem Rev. 2014;114:6589–6631. doi: 10.1021/cr400525m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the Light: The Growing Complexity of p53. Cell. 2009;137:413–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Schwieters CD, Tjandra N. Parameterization of solvent-protein interaction and its use on NMR protein structure determination. J Magn Reson. 2012;221:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Schwieters CD, Tjandra N. Parameterization of solvent–protein interaction and its use on NMR protein structure determination. J Magn Reson. 2012;221:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel D, Jackle H. The fork head domain: a novel DNA binding motif of eukaryotic transcription factors? Cell. 1990;63:455–456. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90439-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells M, et al. Structure of tumor suppressor p53 and its intrinsically disordered N-terminal transactivation domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5762–5767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801353105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically unstructured proteins: re-assessing the protein structure-function paradigm. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:321–331. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Linking folding and binding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:18–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuwen T, et al. Measuring solvent hydrogen exchange rates by multifrequency excitation (15)N CEST: application to protein phase separation. J Phys Chem B. 2018;122:11206–11217. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b06820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangger K, et al. Positioning of micelle-bound peptides by paramagnetic relaxation enhancements. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:4400–4406. doi: 10.1021/jp808501x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangger K, et al. Positioning of micelle-bound peptides by paramagnetic relaxation enhancements. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:4400–4406. doi: 10.1021/jp808501x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.