Abstract

Background & Aims

Bone morphogenetic protein 9 (BMP9) interferes with liver regeneration upon acute injury, while promoting fibrosis upon carbon tetrachloride- induced chronic injury. We have now addressed the role of BMP9 in 3,5 diethoxicarbonyl-1,4 dihydrocollidine (DDC)-induced cholestatic liver injury, a model of liver regeneration mediated by hepatic progenitor cell (known as oval cell), exemplified as ductular reaction and oval cell expansion.

Methods

WT and BMP9KO mice were submitted to DDC diet. Livers were examined for liver injury, fibrosis, inflammation and oval cell expansion by serum biochemistry, histology, RT-qPCR and western blot. BMP9 signalling and effects in oval cells were studied in vitro using western blot and transcriptional assays, plus functional assays of DNA synthesis, cell viability and apoptosis. Crosslinking assays and short hairpin RNA approaches were used to identify the receptors mediating BMP9 effects.

Results

Deletion of BMP9 reduces liver damage and fibrosis, but enhances inflammation upon DDC feeding. Molecularly, absence of BMP9 results in overactivation of PI3K/AKT, ERK-MAPKs and c-Met signalling pathways, which together with an enhanced ductular reaction and oval cell expansion evidence an improved regenerative response and decreased damage in response to DDC feeding. Importantly, BMP9 directly targets oval cells, it activates SMAD1,5,8, decreases cell growth and promotes apoptosis, effects that are mediated by Activin Receptor-Like Kinase 2 (ALK2) type I receptor.

Conclusions

We identify BMP9 as a negative regulator of oval cell expansion in cholestatic injury, its deletion enhancing liver regeneration. Likewise, our work further supports BMP9 as an attractive therapeutic target for chronic liver diseases.

Keywords: BMP9, DDC, liver regeneration, oval cell

1 |. INTRODUCTION

In chronic liver disease, extensive damage occurs in hepatocytes that promotes different mechanisms of removal and repair of damaged cells depending on the stage of the process. When hepatocytes are not capable of executing the regenerative process, hepatic progenitor cells (HPC), also known as oval cells, become the dominant cell source for regeneration. Indeed, it is well documented in humans, as well as in experimental animals that activation, expansion and differentiation of HPCs occur during chronic liver injury.1 In the last years, there has been an intense debate on the real contribution of the HPCs to liver regeneration. Although they have proved to be able to restore the liver parenchyma after extensive damage,2,3 unfortunately this process is often not efficient enough. If the regenerative response cannot replenish dead liver cells, hepatic failure soon occurs, these phenomena having important implications in clinical medicine. Evidence points to the HPC microenvironment as a major determinant of the response to liver injury and subsequent outcome.4 This underlines the need to better understand the mechanisms that regulate the behaviour of HPCs, starting from dissecting the role of specific growth factors and signalling pathways during disease progression.

While the pivotal role of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) as a master cytokine controlling the progression of chronic liver disease is well established,5 the implication of other TGF-β superfamily members such as the bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP) remains to be fully elucidated.6 Of particular interest is BMP9, a member of this family that is primarily expressed in liver, and present in serum at bioactive concentration.7,8 Our laboratory and others have shown that BMP9 promotes proliferation, survival and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma cells, supporting a protumorigenic role of BMP9 in liver.9,10 Furthermore, we and others have recently shown that BMP9 is a profibrogenic factor during carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced chronic liver damage and interferes with hepatocyte-mediated liver regeneration in response to acute insults.11,12

To further expand our knowledge of the role of BMP9 in the hepatic pathophysiology, we have used a mouse model of cholestatic liver injury, induced by 3,5 diethoxicarbonyl-1,4 dihydrocollidine (DDC). This model is appropriate for the study of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), a chronic progressive cholangiopathy characterized by biliary fibrosis and cholestasis that leads to end stage liver disease.13 Importantly, the cholestatic phenotype is accompanied by a ductular reaction (DR) and expansion of HPC/oval cells;13,14 therefore, this model is also used as a chemical liver injury model for induction of oval cell expansion having proved to be optimal to study regulation of oval cell-mediated liver regeneration.

Using the DDC diet in a BMP9 knockout mouse and cultured oval cells, we investigated the function of BMP9 in DR/HPC proliferation-mediated liver regeneration.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Animal model and treatment

BMP9 knockout mice (BMP9-KO) were supplied by Dr. Se-Jin Lee and generated as previously described.15 BMP9-KO and sibling WT mouse lines were maintained in a C57BL/6 background in the UCM animal facility allowed food and water ad libitum, in temperature-controlled rooms under a 12 hours light/dark cycle, and routinely screened for pathogens in accordance with Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations procedures.

Six- to eight-week-old male mice were fed either a control diet or a diet containing the porphyrogenic compound DDC (0.1%) for up to 6 weeks, as previously described16 (DDC from Cymit Quimica; diet produced by Envigo Laboratories; Barcelona, Spain). Experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional and Regional Committee for Animal Care and Use (PROEX 129/16).

2.2 |. Cell culture

The oval cell line used was generated as previously described.17 Early passage cells (passages 1–8) were maintained in 10% FBS supplemented DMEM in a humidified incubator (37°C, 5% CO2). Medium was replaced every 3 days and cells passaged at 90% confluency using trypsin-EDTA. Prior to stimulation with growth factor cells were serum starved for 4–12 hours.

2.3 |. Histological analysis

At sacrifice, liver lobes were thinly sectioned, fixed in 10% formalin and then embedded in paraffin and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Necroinflammatory injury was analysed based on the Knodell Histology Activity Index18 to provide a numerical score to the liver sections, as a semiquantitative assessment of the observed histological features. Histological analysis was performed by a single pathologist. Quantitative morphometric analysis of oval cells expansion was done on (H&E)-stained tissue sections using Image J software. Liver sections were stained with Sirius Red to measure collagen deposition and evaluate fibrosis.

2.4 |. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by paired Student’s t test analysis or 1-way ANOVA to calculate P-values.

For more details on these and other methods used, see Supporting Information. Primers sequences for RT-qPCR are in Table S1.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. BMP9 deletion reduces liver damage and fibrosis in DDC-fed mice

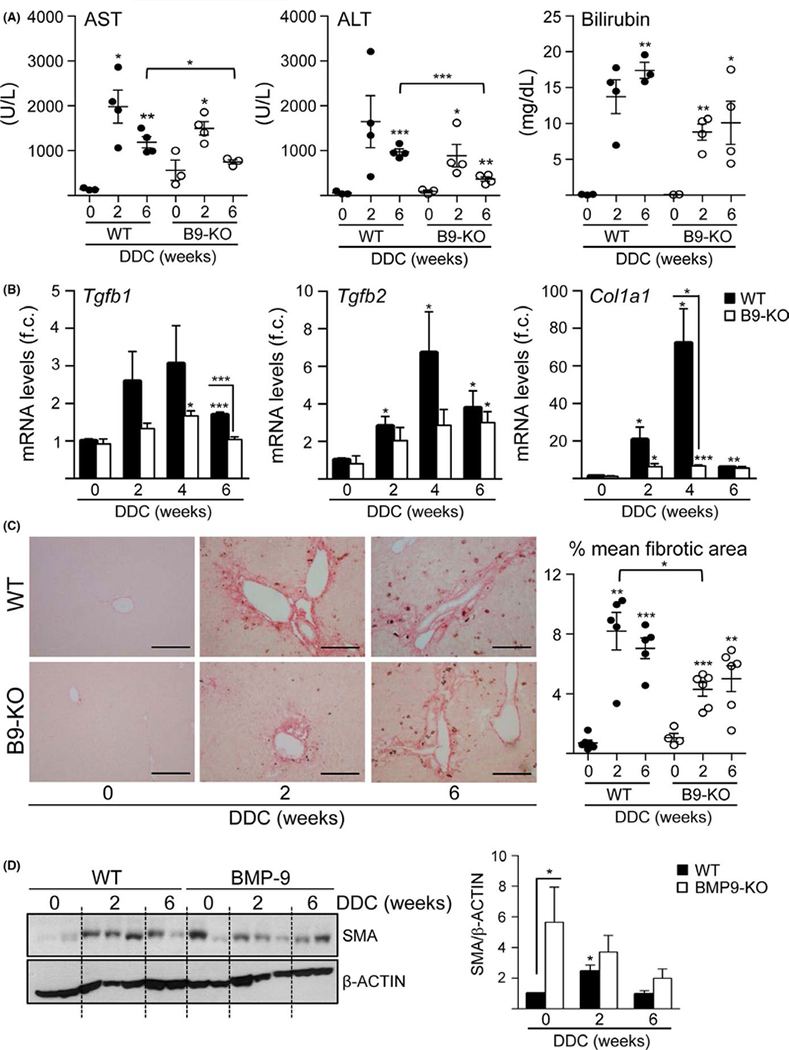

Since our recent data evidenced a role of BMP9 in different models of liver disease,12 we wondered whether BMP9 could play a relevant role in cholestatic liver injury. We fed wild type (WT) and BMP9-KO a diet containing DDC for 2, 4 and 6 weeks. Serum liver function parameters alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and total bilirubin were elevated in response to DDC indicating severe liver damage. The profile was similar in WT and BMP9-KO mice but the increase in ALT, AST and bilirubin was attenuated in BMP9-KO mice, with significantly different values after 6 weeks of diet, providing strong evidence that liver damage is decreased in BMP9-KO mice (Figure 1A). To study the degree of liver fibrosis, we analysed the expression levels of fibrogenic markers such as TGF-β1 (Tgfb1), TGF-β2 (Tgfb2) and procollagen α 1(I) (Col1a1). Consistent with an induction of hepatic damage, all markers were increased in WT mice after DDC treatment, showing a peak of induction at 4 weeks, whereas in BMP9-KO mice the increase in profibrogenic markers was very mild (Figure 1B). Analysis of sirius red staining confirmed that the degree of liver fibrosis in BMP9-KO mice under DDC diet was diminished as compared to WT mice (Figure 1C). Moreover, the hepatic levels of α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) increased in DDC-treated WT, but not BMP9-KO mice, further confirming an alteration in the fibrogenic response (Figure 1D). Interestingly, untreated BMP9-KO livers show higher basal SMA protein levels, which might be related with the stabilizing effects of BMP9 on liver epithelial cells phenotype in healthy liver.12 In conclusion, deletion of BMP9 is associated with less fibrosis in DDC cholestatic mouse model.

FIGURE 1.

Reduced damage and hepatic fibrosis in BMP9-KO mice under a DDC diet. A, AST, ALT and total bilirubin serum levels. Data are mean ± SEM of 3–4 animals per group. B, Tgfb1, Tgfb2 and Col1a1 mRNA levels in liver were determined by RT-qPCR. Data are mean ± SEM of 4–6 animals per group; (f.c.): fold change. C, Representative images of Sirius red staining in liver tissues after DDC treatment (left panel). Scale bar = 100 μm. Total area and fibrotic area (Sirius red-stained area) were measured in 10 regions per section, using 4–6 animals per group (right panel). Data are expressed as % mean of fibrotic area. D, SMA levels in liver were analysed by western blot. One experiment of 3 is shown (left panel). Optical density values are mean ± SEM of 4–7 animals per group (right panel). Data were compared with the untreated group or as indicated, *P < .05, **P < .01 and ***P < .001

3.2 |. Increased inflammatory response in BMP9-KO livers after DDC treatment

Inflammation is pivotal in the pathobiology of cholangiopaties19 and thus occurs in the DDC model.13,20 We performed a comparative analysis of the inflammatory status in WT and BMP9-KO mice. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, interleukin 6 (Il6) and tumour necrosis factor alpha (Tnfa), were upregulated in both WT and BMP9-KO mice after DDC treatment, but after 6 weeks upregulation was significantly stronger in BMP9-KO mice (Figure 2A). Consistently, cytokine-driven signalling, measured as the phosphorylation status of STAT3, was amplified in BMP9-KO mice in response to liver injury (Figure 2B). Furthermore, histological evaluation of the degree of liver damage and inflammation using the Knodell scoring system show that inflammation, specifically intralobular inflammation, was increased in BMP9-KO mice compared to WT mice in response to DDC. Overall, the total necroinflammatory activity shifts from score 7–9 in WT mice to score 10–12 in BMP9-KO mice after 6 weeks of treatment with DDC (Table 1 and Table S2). Collectively, our data indicate that BMP9-KO mice display a significant attenuation of liver fibrosis. This, together with an improved serum biochemistry suggests that deficiency of BMP9 enhances the regenerative process and/or decreases damage. Strikingly, this is accompanied by an accentuation of inflammation, whose consequences are still not clear.

FIGURE 2.

Enhanced hepatic inflammatory response in BMP9-KO livers upon DDC treatment. A, Il6 and Tnfa mRNA levels in liver were determined by RT-qPCR. Data are mean ± SEM of 6–7 animals per group; (f.c.): fold change. B, Phosphorylated and total STAT3 (P-STAT3 and STAT3) levels in liver were analysed by western blot. One experiment of 3 is shown (left panel). Optical density is mean ± SEM of 9 animals per group (right panel). Data were compared with the untreated group or as indicated, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

TABLE 1.

Histological analysis of necroinflammatory activity in the liver of DDC-treated mice

| Parameter |

Periportal piecemeal necrosis |

Intralobular inflammation |

Portal inflammation |

Final score |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1–3 | 4–6 | 7–9 | 10–12 | 13–18 | |

| WT | Untreated | 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 4 | - | - | 5 | 1 | - | - | 2 | 4 | - | - | - | - |

| DDC 2 wk | - | - | - | 6 | - | - | - | - | 6 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 5 | - | - | - | 6 | - | - | |

| DDC 6 wk | - | - | - | 5 | 1 | - | - | - | 5 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 6 | - | - | - | 5 | 1 | - | |

| BMP9-KO | Untreated | 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6 | - | - | 5 | 1 | - | - | - | 6 | - | - | - | - |

| DDC 2 wk | - | - | - | 6 | - | - | - | - | 6 | - | - | - | - | - | 6 | - | - | - | 6 | - | - | |

| DDC 6 wk | - | - | - | 3 | 3 | - | - | - | 3 | 3 | - | - | - | - | 6 | - | - | - | 2 | 4 | - | |

The number of mice with a particular score in each experimental group (n = 6) is indicated.

3.3 |. Increased activation of proliferative and survival signals in BMP9-KO livers after DDC treatment

Next, we aimed at elucidating whether the improved regenerative response observed in BMP9-KO mice following DDC injury could be associated with the regulation of proregenerative signals. We performed a comparative analysis of the activation of AKT and ERK1/2-MAPK, 2 pathways involved in hepatocyte- and oval cell-driven liver regeneration.21,22 Interestingly, BMP9-KO mice showed significantly increased levels of activated AKT and ERK1/2-MAPKs in hepatic tissue along the DDC treatment, suggesting a role for BMP9 on the activation of these kinases in the regenerative process upon DDC damage (Figure 3A). Among the growth factors that could mediate activation of these signals, we focused on HGF/c-Met signalling axis, because it is crucial in the liver regenerative response against different injuries, including cholestatic injury23–25. Additionally, c-Met mutant livers fail to activate AKT and ERK1/2-MAPKs upon DDC diet.25 BMP9-KO mice showed increased activation of c-Met (Figure 3B). These data suggest that genetic deletion of BMP9 increases activation of HGF/c-Met pathway, which may promote the regenerative response in the injured liver.

FIGURE 3.

Increased activation of AKT, ERK1/2-MAPKs and HGF/c-Met signalling in BMP9-KO livers upon DDC treatment. A, Phosphorylated AKT (P-AKT) and ERK1/2-MAPKs (P-ERK1/2) levels in liver were analysed by western blot. One experiment of 3 is shown (left panel). Optical density values are mean ± SEM of 4–9 animals per group (right panel). B, Phosphorylated-MET (P-MET) levels in liver were analysed by western blot. One experiment of 3 is shown (left panel). Optical density values are mean ± SEM of 5–10 animals per group (right panel). Data were compared with the untreated group or as indicated, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001

3.4 |. BMP9 regulates oval cell expansion in vivo

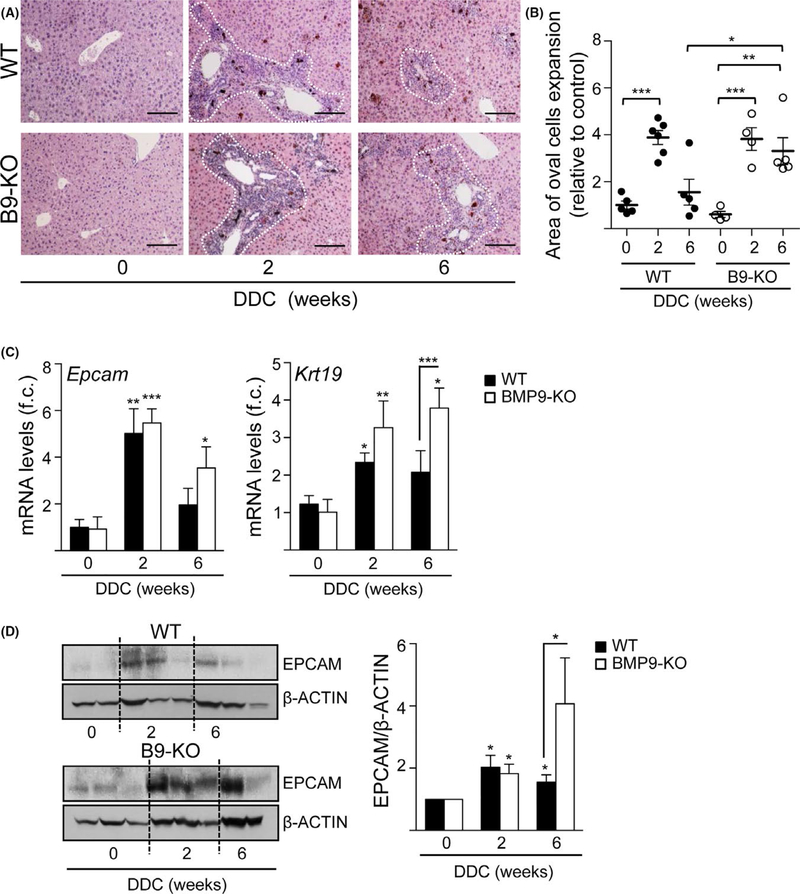

In an attempt to understand how the absence of BMP9 improves the regenerative response after DDC treatment, we analysed oval cell expansion and DR, since DDC feeding has been shown to be an appropriate model for the study of oval cell-mediated liver regeneration.16,26 A comparative quantification of oval cells, identified as small cells with an oval nucleus and scant cytoplasm expanding from the periportal regions, showed that the DR, although evident in both types of animals, was more pronounced in BMP9-KO mice after 6 weeks of DDC feeding (Figure 4A,B and Figure S1). Consistently, histological analysis of periportal areas shows a significant increase in ductal proliferation in BMP9-KO mice compared to WT (Table S3). These results are in agreement with a stronger induction of the expression of 2 oval cell markers, Epcam and cytokeratin 19 (Krt19) (Figure 4C,D). Importantly, BMP9 levels decreased during oval cells expansion (from 1 week onwards) (Figure 5A). This is accompanied by reduced expression of BMP9 type I (Alk1 and Alk2) and type II (Bmpr2) receptors and a decrease in SMAD1,5,8 phosphorylation (Figure 5B,C) suggesting that inhibition of BMP9 signalling is necessary to allow in vivo expansion of oval cells and consequently, to promote the oval cell-mediated regenerative response. All together, these data indicate a negative regulatory role for BMP9 during oval cell expansion.

FIGURE 4.

Stronger hepatic ductular response in BMP9-KO livers upon DDC treatment. A, Representative images of H&E staining in liver tissues after DDC treatment. Scale bar = 100 μm. Dotted lines mark the edges of the area of oval cell expansion. B, Quantitative morphometric analysis of oval cells expansion by measuring areas from 12 periportal regions of each animal (5–8 animals per group). C, Epcam and Krt19 mRNA levels in liver were determined by RT-qPCR. Data are mean ± SEM of 5–8 animals per group; (f.c.): fold change. D, EpCAM levels in liver were analysed by western blot. One experiment of 9 is shown (left panel). Optical density values are mean ± SEM of 10–14 animals per group (right panel). Data were compared with the untreated group or as indicated, *P < .05; **P < .01 and ***P < .001

FIGURE 5.

Decreased BMP9 expression and signalling in liver upon DDC treatment. A, Bmp9 mRNA levels in liver of WT animals after DDC treatment were determined by RT-qPCR. Data are mean ± SEM of 3–7 animals per group; (f.c.): fold change. B, Alk1, Alk2 and Bmpr2 mRNA levels in liver of WT animals were determined by RT-qPCR. Data are mean ± SEM of 3 animals per group; (f.c.): fold change. C, BMP9 and phosphorylated SMAD1,5,8 (P-SMAD1,5,8) levels in liver were analysed by western blot. One experiment of 2–3 is shown (left panel). Optical density values are mean ± SEM of 4–10 animals per group (right panel). Data were compared with the untreated group or as indicated, *P < .05 and ***P < .001

3.5 |. BMP9 requires ALK2 to activate Smad signalling and to induce oval cell loss in vitro

To directly address the potential regulatory role of BMP9 on oval cells and to characterize the molecular mechanisms mediating its effects, we performed additional experiments using an established in vitro model of oval cells.17 Oval cells responded to BMP9 with activation of the canonical Smad signalling. BMP9 induced SMAD1,5,8 phosphorylation early (30 minutes), with a maximum at 2 hours and in a dose dependent manner (Figure 6A). Additionally, BMP9 increased BRE-luciferase activity in oval cells and upregulated Id1 mRNA expression, a major downstream transcriptional target of BMP signalling (Figure 6B,C) demonstrating a functional SMAD-dependent transcriptional response to BMP9. Since our data in the DDC model suggest that BMP9 negatively regulates oval cell expansion and our previous data show that BMP9 regulates hepatocellular carcinoma cells and hepatocytes proliferation and survival,9,27 we next analysed whether BMP9 could modulate oval cell proliferation in vitro. Data show that BMP9 moderately but significantly decreases oval cell number in culture (Figure 6D) by inhibiting cell proliferation, measured by [3H] thymidine incorporation, and by inducing apoptotic cell death (Figure 6E–F).

FIGURE 6.

BMP9-induced signalling and response in oval cells in vitro. A, Activation of SMAD1,5,8 by BMP9 was analysed by western blot. For time course analysis, BMP9 2 ng/mL was utilized. One experiment of 6 is shown (left panel). Optical density values are mean ± SEM of 6 independent experiments (right panel). B, (BRE)-Luciferase activity in oval cells treated with BMP9 (2 ng/mL) for 8 h. Data are mean ± SEM of 3 experiments (n = 6). (f.c.): fold change. C, Id1 mRNA levels were determined by RT-qPCR in oval cells treated with BMP9 (2 ng/mL). Data are mean ± SEM of 3 experiments (n = 6); (f.c.): fold change. D, Cells were counted after BMP9 treatment (2 ng/mL). Data are mean ± SEM of 5 experiments (n = 3). E, Thymidine incorporation in cells cultured for 24 h with BMP9 (2 ng/mL). Data are mean ± SEM of 3 experiments; (f.c.): fold change. F, Cells were treated with BMP9 (2 ng/mL) for 24 h and apoptotic nuclei were counted. Data are mean ± SEM of 4 experiments (n = 3); (f.c.): fold change. Data were compared with the untreated condition or as indicated. *P < .05 and ***P < .001

In an effort to further elucidate the BMP9 signalling pathway in oval cells, we next studied the receptors involved. ALK1 is the high affinity receptor for BMP9.28 However, BMP9 also binds ALK2 in non-endothelial cells when ALK1 expression is weak or absent.29,30 Oval cells do express both receptors, although ALK2 expression levels are greater than those of ALK1 (Figure 7A). To define which receptors participate in the BMP9 signalling complex in oval cells, we incubated cells with 125I_BMP9 and immunoprecipitated crosslinked receptor complexes with ALK1, ALK2 and BMPRII specific antibodies. Results show that in oval cells BMP9 binds to ALK2 and BMPRII but not ALK1 (Figure 7B). To further confirm these data, we generated shALK2 oval cells. A 60% knock down of ALK2 expression levels was achieved (Figure 7C). shALK2 oval cells displayed strongly reduced phosphorylation of SMAD1,5,8 in response to BMP9 and inhibition of SMAD-dependent transcriptional activity (Figure 7D,E). Moreover, in shALK2 cells, the suppressor effect of BMP9 on oval cell proliferation was strongly abolished (Figure 7F). In parallel, we knocked down ALK1 in oval cells and found that BMP9 was still able to trigger SMAD-dependent transcriptional activity and to decrease oval cell number (Figure S2). All together, these data indicate that ALK2, but not ALK1, mediates BMP9 signalling and the decrease in oval cell number.

FIGURE 7.

BMP9 requires ALK2 to activate Smad signalling and induce cell loss in oval cells. A, RNA from oval cells was isolated and Alk1 and Alk2 levels were analysed by RT-qPCR. Data are expressed as relative gene expression and are mean ± SEM of 8 experiments. B, Oval cells were affinity-labelled with 125I_BMP9 and crosslinked ligand-receptor complexes were immunoprecipitated with specific antisera as indicated and subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. C-F, Alk2 knockdown (shALK2) and non-target control (NT) oval cells were generated and treated with BMP9 (2 ng/mL). C, Alk2 mRNA levels determined by RT-qPCR. (f.c.): fold change. D, Analysis of P-SMAD1,5,8 by western blot. One experiment of 3 is shown (upper panel). Optical density values are mean ± SEM of 3 experiments (lower panel). E, (BRE)-luciferase activity. Data are mean ± SD of 1 representative experiment (n = 6); (f.c.): fold change. F, Cell count (2 d of BMP9 treatment). Data are mean ± SEM of 3 experiments (n = 3). Data were compared with the untreated condition or as indicated. *P < .05, **P < .01 and ***P < .001

4 |. DISCUSSION

Understanding signalling pathways and molecular regulation of liver regeneration is of high interest, because it provides the basis to improve or modulate the liver regenerative capacity, thus opening new avenues on therapeutic intervention in chronic liver diseases, apart from orthotopic liver transplantation. Here, we have studied the role of BMP9, a BMP family member mainly expressed in liver7,8 and with an emergent role in liver disease and regeneration,9,10,12 in an animal model of chronic cholestatic liver injury which represents an example of liver regeneration associated with oval cell expansion. We have therefore explored the regulatory role of BMP9 on oval cells.

Our data show that genetic deletion of BMP9 ameliorates DDC-induced liver damage, evidenced by better liver function tests in serum and a reduced fibrogenic response (Figure 1). The decrease in liver damage and fibrosis is concomitant with an amplified DR (Figure 4), suggesting that enhanced oval cell expansion is contributing to improve liver regeneration and liver function restoration in this model. Although the regenerative potential of oval cells has been demonstrated in some contexts,31–33 in others, oval cells have shown to actually drive fibrogenesis.34,35 Our data support a beneficial, rather than detrimental role of oval cell expansion in liver regeneration upon DDC-induced biliary fibrosis. Importantly, the fact that BMP9-KO mice show a reduced degree of fibrosis in response to DDC feeding (Figure 1) reinforces the idea that BMP9 acts as a profibrogenic factor in the liver, not only in toxic liver fibrosis (CCl4 model) as we have described before but also in cholestatic liver fibrosis caused by biliary injury.

Strikingly, the analysis of hepatic inflammatory parameters revealed an enhanced hepatic inflammatory response on DDC-fed BMP9-KO mice (Figure 2). Putting together all in vivo data, we hypothesize that the increased inflammation could have a positive role in oval cell expansion during the DDC-induced regenerative response. Supporting this, other studies have evidenced that inflammatory cytokines are critical regulators of oval cell expansion.36,37 Most notably, recent work demonstrated that modulation of the inflammatory niche and hepatic stellate cell production of macrophages-mobilizing chemokines, like CCL2, is required for oval cell expansion after DDC feeding. It is not known whether and how BMP9 mediates the production of inflammatory signals. Nevertheless, it is already known that BMP9 represses CCL2 expression in endothelial cells38 and that CCL2 is upregulated in regenerating rat liver and enhances oval cell proliferation.39 These data stimulate further studies on the role of BMP9 in regulation of inflammation upon DDC-induced cholestatic injury and oval cell expansion, and on how this might influence liver regeneration.

In concordance with a beneficial effect of BMP9 deletion on the hepatic regenerative process, we show a strong activation of PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 signalling after DDC diet in BMP9-KO mice (Figure 3A), pathways that play a major role in liver regeneration, including oval cell-mediated liver regeneration.25 But more remarkable is the finding of an overactivated HGF/c-Met pathway in DDC-treated BMP9-KO mice (Figure 3B), which suggests a role for this pathway in controlling oval cell expansion and the efficacy of regeneration. Supporting this concept, absence of c-Met signalling severely impairs DDC-induced liver regeneration25 and increases liver damage and fibrosis in bile duct ligation-induced cholestatic injury.40 Activation dynamics of c-Met in BMP9-KO mice upon DDC-induced chronic injury coincides with the peak of oval cell expansion and concurs with AKT activation, while preceding ERKs-MAPK activation. Both PI3K/AKT and ERKs-MAPKs activation have been associated with c-Met-triggered responses in oval cells.41,42 It is therefore tempting to speculate that HGF/c-Met signalling is responsible for the strong activation of PI3K/AKT and ERKs-MAPK seen in BMP9-KO mice. Nevertheless, possible contributions from other growth factors remain to be investigated.

We provide in vivo and in vitro evidence showing that BMP9 is a novel regulator of oval cell biology. Firstly, genetic deletion of BMP9 results in an amplified oval cell expansion (Figure 4). This is consistent with the fact that BMP9 expression and signalling are down- regulated upon DDC treatment (Figure 5), concomitant with oval cell expansion. Data showing that oval cells in culture respond to BMP9 activating SMAD1,5,8 and upregulating Id1, together with the BMP9-mediated decrease in cell number and induction of apoptosis (Figure 6), are the unequivocal demonstration that oval cells are a direct target of BMP9 actions. Interestingly, both crosslinking and knockdown approaches indicate that BMP9 effects in oval cells are mediated by ALK2 type I receptor (Figure 7), which despite not being considered a BMP9-high affinity receptor, it has shown to mediate BMP9 signalling in other epithelial cells.29,30

Thus, oval cells now join the group of BMP9 responsive hepatic cell types, together with hepatocytes, hepatocellular carcinoma cells9,10,27 and also hepatic stellate cells.11,12 More than that, since stellate cells also produce BMP9,12 BMP9 raises as an important component of the liver progenitor cell niche and hence as a paracrine regulator of oval cell expansion.

What is not clear at all is why BMP9 effects are so cell type or context-dependent. Further research will clarify whether it is a matter of activation of different receptors and signals, balance between canonical and non-canonical signalling, crosstalk with other growth factors, among other potential explanations.

Overall, our data render a picture in which BMP9, by exerting its action in different hepatic cell populations, could act as a major regulator of liver pathophysiology. Its double action as profibrogenic factor and negative regulator of the oval cell regenerative activity could have a significant impact on cell fate and outcome following liver injury. As already mentioned, the DDC model is a model for PSC,13 a liver disease with very limited treatment possibilities nowadays.43 Information on BMP9 signalling in human chronic cholestatic diseases is very scarce. We found a public data set (GSE61256) including liver samples from subjects with PSC and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), the 2 major types of chronic cholestatic liver disease in human. No changes in Bmp9 expression are seen in the PSC cohort. However, Smad1 is downregulated, and contrarily, Smad6 and 7, 2 inhibitory Smads of BMP signalling, are upregulated, which overall suggest a negative regulation of BMP pathway. In PBC, Bmp9 and Alk2 are strikingly upregulated. However, similarly to PSC, Smad1 and Smad5 are downregulated, whereas Smad7 is upregulated. No conclusions can yet be drawn with such limited data, but it provides a hint towards regulation of BMP(9)/Smad1,5 signalling in cholestatic diseases, encouraging further studies to clarify the clinical significance of our findings.

Full characterization of the mechanisms mediating BMP9 responses is also pending. Awaiting for all this, data presented here, together with previous work uncovering BMP9 role in liver fibrosis, lead us to propose BMP9 as an attractive target in the therapy of chronic liver diseases.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

Genetic deletion of BMP9 reduces DDC-induced cholestatic liver fibrosis and damage

Absence of BMP9 is associated with increased oval cell expansion during DDC-induced cholestatic injury

BMP9 decreases cell growth and promotes apoptosis in oval cells in vitro

Smad activation and cell loss induced by BMP9 in oval cells are mediated via ALK2 type I receptor

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Financial support statement provided before. A.A. was recipient of a Marie Curie ESR contract from IT-LIVER. L.A. was recipient of a predoctoral contract from UCM. M.G-A was recipient from a research contract from the MITOLAB consortium. Authors thank Patricia Saperas and Maarten van Dinther for their technical assistance with histological analysis and crosslinking assay respectively. Financial sources had no involvement in study design or in data analysis.

Funding Information

This work was supported by a Marie Curie Action of FP7–2012 (Grant #PITN-GA-2012–316549; IT-LIVER); Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Spain (Grant #SAF2015–69145-R); Health Research Fund-Institute of Health Carlos III, Spain (Grant #PI10/00274); and General Direction of Universities and Research of the Autonomous Community of Madrid, Spain (Grant #S2010/BMD-2402).

Abbreviations

- ALK

Activin receptor-like kinase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- BMP

Bone morphogenetic protein

- CCl4

carbon tetrachloride

- DDC

3,5 diethoxicarbonyl-1,4 dihydrocollidine

- DR

ductular reaction

- HPC

hepatic progenitor cells

- PBC

primary biliary cirrhosis

- PSC

primary sclerosing cholangitis

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor beta

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors do not have any disclosures to report.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kohn-Gaone J, Gogoi-Tiwari J, Ramm GA, Olynyk JK, Tirnitz-Parker JE. The role of liver progenitor cells during liver regeneration, fibrogenesis, and carcinogenesis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2016;310:G143–G154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alison MR, Lin WR. Regenerative medicine: hepatic progenitor cells up their game in the therapeutic stakes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:610–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu WY, Bird TG, Boulter L, et al. Hepatic progenitor cells of biliary origin with liver repopulation capacity. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:971–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J, Chen L, Zern MA, et al. The diversity and plasticity of adult hepatic progenitor cells and their niche. Liver Int 2017;37:1260–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giannelli G, Mikulits W, Dooley S, et al. The rationale for targeting TGF-beta in chronic liver diseases. Eur J Clin Invest. 2016;46:349–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrera B, Addante A, Sanchez A. BMP signalling at the crossroad of liver fibrosis and regeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2017;19:pii: E39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bidart M, Ricard N, Levet S, et al. BMP9 is produced by hepatocytes and circulates mainly in an active mature form complexed to its prodomain. Cell Mol Life Sci 2012;69:313–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller AF, Harvey SA, Thies RS, Olson MS. Bone morphogenetic protein-9. An autocrine/paracrine cytokine in the liver. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17937–17945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrera B, Garcia-Alvaro M, Cruz S, et al. BMP9 is a proliferative and survival factor for human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e69535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Q, Gu X, Weng H, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein-9 (BMP-9) induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:398–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li P, Li Y, Zhu L, et al. Targeting secreted cytokine BMP9 gates the attenuation of hepatic fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1864:709–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breitkopf-Heinlein K, Meyer C, Konig C, et al. BMP-9 interferes with liver regeneration and promotes liver fibrosis. Gut. 2017;66:939–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fickert P, Stoger U, Fuchsbichler A, et al. A new xenobiotic-induced mouse model of sclerosing cholangitis and biliary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:525–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jakubowski A, Ambrose C, Parr M, et al. TWEAK induces liver progenitor cell proliferation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2330–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ricard N, Ciais D, Levet S, et al. BMP9 and BMP10 are critical for postnatal retinal vascular remodeling. Blood. 2012;119:6162–6171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preisegger KH, Factor VM, Fuchsbichler A, et al. Atypical ductular proliferation and its inhibition by transforming growth factor betal in the 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine mouse model for chronic alcoholic liver disease. Lab Invest. 1999;79:103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.del Castillo G, Factor VM, Fernandez M, et al. Deletion of the Met tyrosine kinase in liver progenitor oval cells increases sensitivity to apoptosis in vitro. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1238–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knodell RG, Ishak KG, Black WC, et al. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology. 1981;1:431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollheimer MJ, Fickert P, Stieger B. Chronic cholestatic liver diseases: clues from histopathology for pathogenesis. Mol Aspects Med. 2014;37:35–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamazaki Y, Moore R, Negishi M. Nuclear receptor CAR (NR1I3) is essential for DDC-induced liver injury and oval cell proliferation in mouse liver. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1624–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitade M, Factor VM, Andersen JB, et al. Specific fate decisions in adult hepatic progenitor cells driven by MET and EGFR signaling. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1706–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morales-Ruiz M, Santel A, Ribera J, Jimenez W. The Role of Akt in Chronic Liver Disease and Liver Regeneration. Semin Liver Dis. 2017;37:11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomez-Quiroz LE, Seo D, Lee YH, et al. Loss of c-Met signaling sensitizes hepatocytes to lipotoxicity and induces cholestatic liver damage by aggravating oxidative stress. Toxicology. 2016;361–362:39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huh CG, Factor VM, Sanchez A, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor/c-met signaling pathway is required for efficient liver regeneration and repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4477–4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishikawa T, Factor VM, Marquardt JU, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor/c-met signaling is required for stem-cell-mediated liver regeneration in mice. Hepatology. 2012;55:1215–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson MD, Wickline ED, Bowen WB, et al. Spontaneous repopulation of beta-catenin null livers with beta-catenin-positive hepatocytes after chronic murine liver injury. Hepatology. 2011;54:1333–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Alvaro M, Addante A, Roncero C, et al. BMP9-Induced Survival Effect in Liver Tumor Cells Requires p38MAPK Activation. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:20431–20448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown MA, Zhao Q, Baker KA, et al. Crystal structure of BMP-9 and functional interactions with pro-region and receptors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25111–25118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herrera B, van Dinther M, Ten Dijke P, Inman GJ. Autocrine bone morphogenetic protein-9 signals through activin receptor-like kinase-2/Smad1/Smad4 to promote ovarian cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9254–9262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scharpfenecker M, van Dinther M, Liu Z, et al. BMP-9 signals via ALK1 and inhibits bFGF-induced endothelial cell proliferation and VEGF-stimulated angiogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:964–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papp V, Rokusz A, Dezso K, et al. Expansion of hepatic stem cell compartment boosts liver regeneration. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strick-Marchand H, Weiss MC. Embryonic liver cells and permanent lines as models for hepatocyte and bile duct cell differentiation. Mech Dev. 2003;120:89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Foster M, Al-Dhalimy M, et al. The origin and liver repopulating capacity of murine oval cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(Suppl 1):11881–11888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clouston AD, Powell EE, Walsh MJ, et al. Fibrosis correlates with a ductular reaction in hepatitis C: roles of impaired replication, progenitor cells and steatosis. Hepatology. 2005;41:809–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pi L, Robinson PM, Jorgensen M, et al. Connective tissue growth factor and integrin alphavbeta6: a new pair of regulators critical for ductular reaction and biliary fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2015;61:678–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weng HL, Feng DC, Radaeva S, et al. IFN-gamma inhibits liver progenitor cell proliferation in HBV-infected patients and in 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine diet-fed mice. J Hepatol. 2013;59:738–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiang S, Dong HH, Liang HF, et al. Oval cell response is attenuated by depletion of liver resident macrophages in the 2-AAF/partial hepatectomy rat. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young K, Tweedie E, Conley B, et al. BMP9 Crosstalk with the Hippo Pathway Regulates Endothelial Cell Matricellular and Chemokine Responses. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0122892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao WM, Qin YL, Niu ZP, et al. Branches of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway regulate proliferation of oval cells in rat liver regeneration. Genet Mol Res 2016;15:gmr7750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giebeler A, Boekschoten MV, Klein C, et al. c-Met confers protection against chronic liver tissue damage and fibrosis progression after bile duct ligation in mice. Gastroenterology 2009;137:297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Factor VM, Seo D, Ishikawa T, et al. Loss of c-Met disrupts gene expression program required for G2/M progression during liver regeneration in mice. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e12739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez-Palacian A, del Castillo G, Suarez-Causado A, et al. Mouse hepatic oval cells require Met-dependent PI3K to impair TGF-beta- induced oxidative stress and apoptosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e53108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wagner M, Trauner M. Recent advances in understanding and managing cholestasis. F1000Res. 2016;5:705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.