Abstract

It has long been established that mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients can trigger pathological changes in cell metabolism by altering metabolic enzymes such as the mitochondrial 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 10 (17β-HSD10), also known as amyloid-binding alcohol dehydrogenase (ABAD). We and others have shown that frentizole and riluzole derivatives can inhibit 17β-HSD10 and that this inhibition is beneficial and holds therapeutic merit for the treatment of AD. Here we evaluate several novel series based on benzothiazolylurea scaffold evaluating key structural and activity relationships required for the inhibition of 17β-HSD10. Results show that the most promising of these compounds have markedly increased potency on our previously published inhibitors, with the most promising exhibiting advantageous features like low cytotoxicity and target engagement in living cells.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease (AD), amyloid-beta peptide (Aβ), mitochondria, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 10 (17β-HSD10), amyloid binding alcohol dehydrogenase (ABAD), benzothiazole

1. Introduction

There is a strong, well-documented connection between Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and mitochondrial dysfunction [1,2,3]. Mitochondrial changes in AD patients are an early event, preceding the onset of amyloid plaque formation, and include morphology abnormalities and changes in metabolism stemming from alterations in the complexes of the electron transport chain, the enzymes in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), and changes in components of the mitochondrial membrane involved in import/export flux. Mitochondria are key to the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) via the metabolism of glucose and fatty acids. Mitochondrial dysfunction in AD includes activity changes in many enzymes involved in these processes and contributes to the reduction in energy metabolism in AD [4]. Mitochondrial dysfunction is also exacerbated by the presence of amyloid beta peptide (Aβ) within mitochondria [5]. One mitochondrial enzyme affected in AD is 17β-HSD10 (17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 10, also known as amyloid-β binding alcohol dehydrogenase (ABAD) or 3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase). 17β-HSD10’s primary role is to utilise several substrates to produce energy in the β-fatty acid oxidation pathway, the energy source when glucose levels are low, playing a prominent role in AD, where glucose metabolism is significantly decreased [6]. Importantly, we and others have shown that inhibition of this enzyme is beneficial in both in vitro and in vivo AD models in its own right and also protects against Aβ toxicity in both cellular and transgenic mouse models of AD [7,8,9,10,11,12]. A current working hypothesis is that by inhibiting the enzyme activity of 17β-HSD10 (a contributor to the β-fatty acid oxidation pathway) this can help re-balance alterations in glucose metabolism observed in AD (Aitken unpublished data).

17β-HSD10 was first identified as an Aβ binding protein in 1997 [13], a finding which has subsequently been confirmed using a number of techniques [5,13,14]. 17β-HSD10 is known to interact with the two major plaque forming isoforms of Aβ, namely Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42), leading to distortion of the enzyme structure and inhibition of its normal function as an energy provider for cells [15,16]. In vitro experiments have shown that the interaction between 17β-HSD10 and Aβ is cytotoxic and 17β-HSD10’s function is altered with a build-up of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and toxins leading to mitochondrial dysfunction. Using site-directed mutagenesis and surface plasmon resonance protein interaction assays (SPR), Lustbader et al. identified the LD loop of the 17β-HSD10 protein as the binding site for Aβ and subsequently synthesised a 28-amino acid peptide encompassing this region, which was termed the 17β-HSD10 decoy peptide [5]. Using SPR assays it has been shown that this 17β-HSD10 decoy peptide can prevent the binding of 17β-HSD10 to Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42). Significantly, inhibition of the interaction between 17β-HSD10 and Aβ by the 17β-HSD10-decoy peptide was shown to translate into a cytoprotective effect in cell culture experiments. Cortical neurons exposed to Aβ(1–42) showed a significant increase in cell death, as measured by cytochrome-c release, whilst those pre-incubated with the 17β-HSD10 decoy peptide did not. Critically, for the first time, this work demonstrated that inhibition of the 17β-HSD10-Aβ interaction may target potential disease- relevant mechanisms.

Other than the disruption of the 17β-HSD10/Aβ interaction, there is a second approach which may hold merit in treating AD: the direct modulation of 17β-HSD10 enzyme activity. In vitro experiments with neuronal-like SHSY-5Y cells exposed to the 17β-HSD10 inhibitor AG18051, showed a reduction in mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress associated with the interaction between 17β-HSD10 and Aβ and protected the cells from Aβ-mediated cytotoxicity [7,8]. This proved that inhibiting 17β-HSD10 activity may also be a viable therapeutic approach for the treatment of AD.

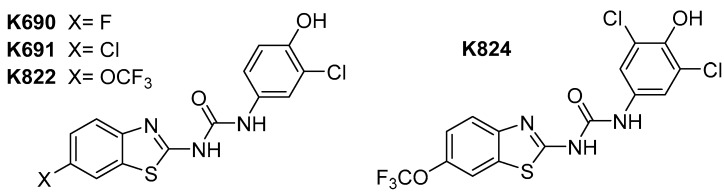

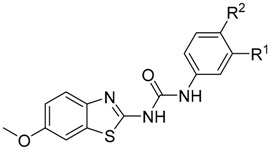

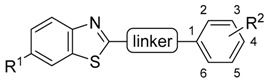

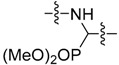

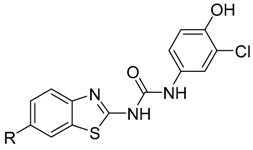

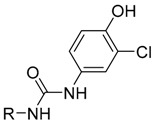

In our previously published work [9] we discuss the rationale behind utilising analogues of the FDA-approved drugs frentizole and riluzole as inhibitors of 17β-HSD10 for potential therapeutics in AD. Briefly, many benzothiazole analogues have been shown to possess various biological activities in the central nervous system, with riluzole itself highlighted as neuroprotective. Thus, we focused on generating potent 17β-HSD10 inhibitors based on the benzothiazole scaffold, identifying several potent inhibitors (Figure 1) [9].

Figure 1.

Structure of previously identified benzothiazolylurea inhibitors.

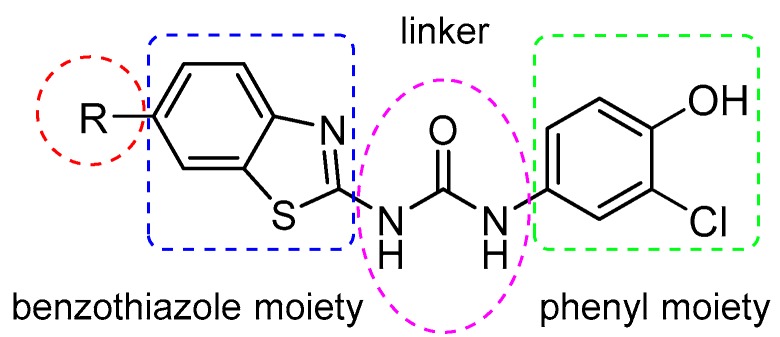

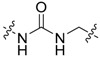

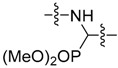

These compounds highlighted key structural features required for 17β-HSD10 inhibition with the 6-trifluromethoxy and 6-halogen substitution of the benzothiazole moiety and 3-chloro, 4-hydroxy substitution of the phenyl moiety proving the most favourable, however, with limited solubility the compounds were not optimal for cellular evaluation. The aim of this study was not only to generate benzothiazole urea scaffolds which would show improved potency, but to also generate compounds with improved tolerance and less cytotoxicity within our cellular assays, i.e., better pharmacokinetic parameters. To that end, four series of compounds have been synthesised targeting the key areas of benzothiazole moiety, phenyl ring and urea linker (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Design of benzothiazolylurea-based 17β-HSD10 inhibitors.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structural Design and Chemical Synthesis

The first series of compounds is a continuation of our previously reported work [9]. While the benzothiazole scaffold and urea linker were kept intact, further substitution changes into the distal phenyl ring were introduced, mainly at position 3 (Table 1). Methoxy substitutions at position 6 of benzothiazole were selected and based on the comparable inhibitory activity with halogenated analogues and due to the availability of starting material and improved physical chemical properties.

Table 1.

First series of prepared compounds (2–11).

| Compound ID | R1 | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | Me | -OH |

| 3 | t-butyl | -OH |

| 4 | -CN | -OH |

| 5 | -Br | -OH |

| 6 | -I | -OH |

| 7 | -NH2 | -OH |

| 8 | 6-hydroxypyridin-3-yl a | |

| 9 | - | -NH2 |

| 10 | -Cl | -NH2 |

| 11 | -Cl | -CH2OH |

a Substitution pattern replacement of whole distal phenyl ring.

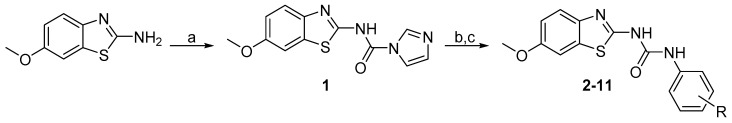

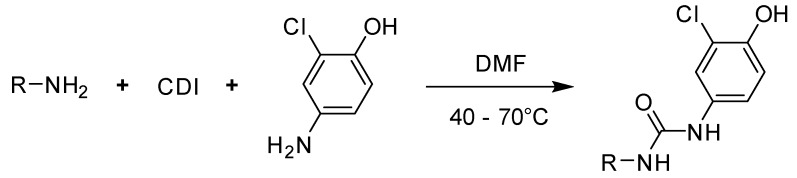

Benzothiazolylureas were formed using the two-step reaction process subsequently described. Initially, 6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-amine was activated with 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI; Scheme 1a). Subsequently, intermediate 1 was reacted with corresponding substituted aniline (resp. 5-aminopyridin-2-ol for final product 8) to give final di-substituted ureas (2–11). To obtain compounds 7, 9 and 10, N-Boc protective group was cleaved under acidic conditions (Scheme 1c) as the final step of their synthesis.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 2–11. Reagents and conditions: (a) CDI, DCM, RT; (b) aniline derivative, MeCN, reflux; (c) 4 M HCl, dioxane, RT (for N-Boc protected intermediates).

Most aniline derivatives were commercially available, but in several cases the aniline intermediates had to be prepared as further described:

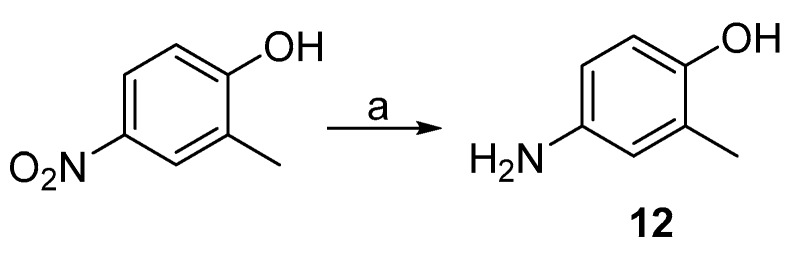

In general, reduction of substituted nitrobenzenes into the corresponding anilines (e.g., 12) was achieved with palladium on activated carbon (Pd/C) catalysed hydrogenation (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of aniline intermediate 12. Reagents and conditions: (a) Pd/C, H2, EtOH, RT.

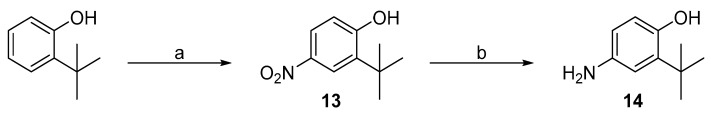

2-(Tert-butyl)phenol was selected as a starting material for introduction of tert-butyl group into the meta position of distal phenyl ring. Firstly, nitration was achieved with nitric acid in the presence of acetic acid as reaction solvent (Scheme 3a) to obtain intermediate 13. Secondly, the introduced nitro group was reduced to 4-amino-2-(tert-butyl)phenol (14). Initially, the reduction was attempted with Pd/C catalysed hydrogenation (Scheme 2). However, a complex mixture of decomposed starting material was received. Thus, reduction was accomplished using iron powder and ammonium chloride (Scheme 3b) to successfully obtain intermediate 14.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of intermediates 13 and 14. Reagents and conditions: (a) HNO3/CH3COOH, RT; (b) Fe, NH4Cl, MeOH/H2O, RT.

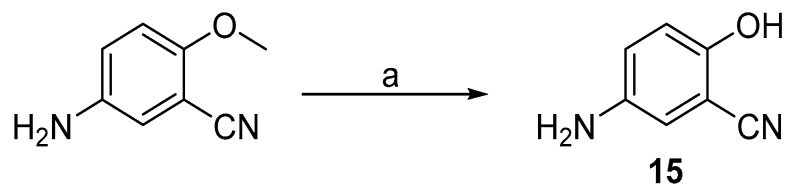

5-amino-2-hydroxybenzonitrile (15) was prepared from its methoxy analogue by demethylation using aluminium chloride (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of intermediate 15. Reagents and conditions: (a) AlCl3, DCM, reflux.

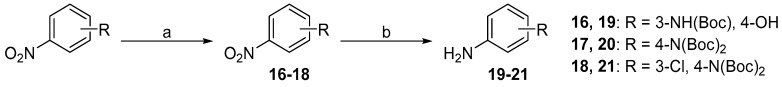

N-Boc (de)protection had to be performed in order to obtain final compounds with the free amine group on the distal phenyl ring. Firstly, the amine group of nitroaniline was protected with di-tert-butyl dicarbonate (Scheme 5a) to yield intermediates 16–18. Secondly, the nitro group was reduced with Pd/C catalysed hydrogenation to obtain intermediates 19–21 (Scheme 5b). Final N-Boc acidic deprotection was performed after the urea formation step (Scheme 1).

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of intermediates 16–21. Reagents and conditions: (a) (Boc)2O, DMAP, THF, RT; (b) Pd/C, H2, EtOH, RT.

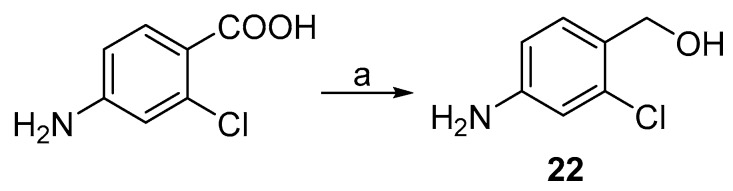

Aniline analogue with primary alcohol group in the para position (22) was generated via reduction of corresponding carboxylic acid with lithium aluminium hydride (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of intermediate 22. Reagents and conditions: (a) LiAlH4, THF, −5 °C to RT.

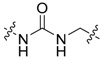

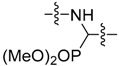

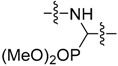

The next series was focused on selected modifications in the linker region of the scaffold, while the original distal phenyl ring substitution (3-chlorine-4-hydroxy) was selected in combination with either 6-methoxy, 6-chlorine or unsubstituted benzothiazole ring (Table 2). Additionally, to compliment recently published work [8,17], dimethyl phosphonate analogues were prepared as standards (34–36) for comparison between inter-workgroup biological evaluations along with the most promising 3-chloro, 4-hydroxy substitution pattern. Finally, methylation of either one or both nitrogen atoms of the urea linker was conducted with the aim of constraining the conjugation between the two aromatic moieties.

Table 2.

Second series of prepared compounds (23–49).

Compound ID

|

R1 | Linker | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | Cl |

|

3-Cl, 4-OH |

| 24 | OMe |

|

3-Cl, 4-OH |

| 26 | OMe |

|

3-Cl, 4-OH |

| 28 | OMe |

|

3-Cl, 4-OH |

| 29 | OMe |

|

3-OH, 4-OH |

| 34 | OMe |

|

4-F |

| 35 | OMe |

|

4-OH |

| 36 | OMe |

|

3-COOCH3, 4-OH |

| 37 | OMe |

|

3-Cl, 4-OH |

| 41 | - |

|

3-Cl, 4-OH |

| 45 | - |

|

3-Cl, 4-OH |

| 46 | OMe |

|

3-Cl, 4-OH |

| 49 | - |

|

3-Cl, 4-OH |

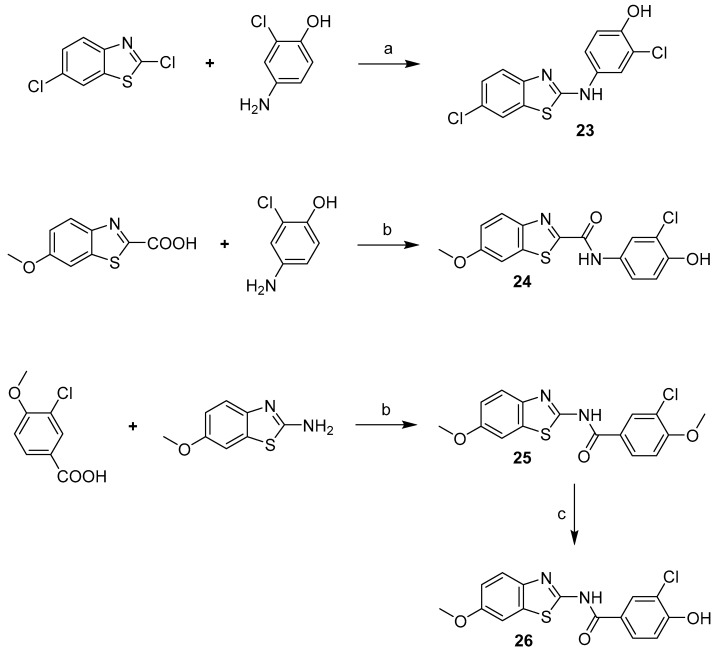

Compound 23 with linker consisting of a secondary amine group was prepared by means of simple N-alkylation, and amides 24 and 25 were prepared in a reaction of corresponding carboxylic acid with CDI and corresponding amine. Compound 25 was subsequently O-demethylated to give the final product 26 (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of compounds 23–26. Reagents and conditions: (a) NMP, 160 °C; (b) CDI, DMF, RT; (c) AlCl3, DCM, reflux.

Compounds 28 and 29 were prepared using the general procedure for urea linker synthesis in reaction with CDI (Scheme 8). In case of compound 28 synthesis, the corresponding benzylamine intermediate (27) was first prepared from its methoxy analogue by demethylation using AlCl3 (Scheme 8).

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of compounds 27–29. Reagents and conditions: (a) AlCl3, DCM, reflux; (b) MeCN, reflux.

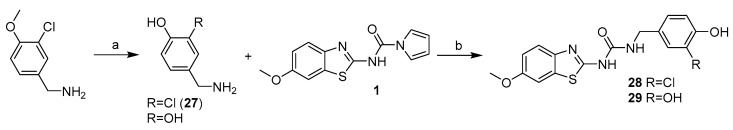

While the originally used reaction conditions proved to be troublesome to produce the desired compounds [17], dimethyl phosphonates (34–37) were instead prepared in a two-step process. Firstly, 6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-amine and corresponding aldehyde were coupled at reflux conditions to obtain imines 30–33, which were subsequently treated with dimethyl phosphite and 1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine to generate the final products in satisfactory yields (Scheme 9).

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of phosphonate derivatives. Reagents and conditions: (a) toluene, reflux; (b) dimethyl phosphite, 1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine, THF, 65 °C.

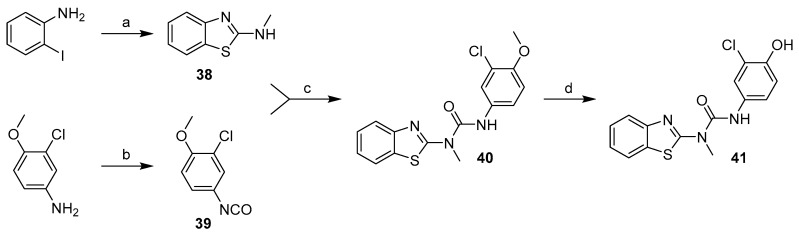

Compound 41 was prepared in four steps (Scheme 10). The benzothiazole moiety (38) was prepared from 2-iodoaniline in reaction with methylisothiocynate and tetrabutylammonium bromide catalysed by copper (I) chloride [18]. 3-chloro-4-methoxyaniline was treated with triphosgene to give the isocyanate intermediate (39), which was then reacted with the benzothiazole moiety and the resulting methoxy derivative (40) was demethylated using AlCl3 to give compound 41.

Scheme 10.

Synthesis of compound 41. Reagents and conditions: (a) MeNCS, TBABr, CuCl, DMSO, 60–80 °C; (b) triphosgene, Et3N, DCM, 0 °C–reflux; (c) THF, RT; (d) AlCl3, toluene, reflux.

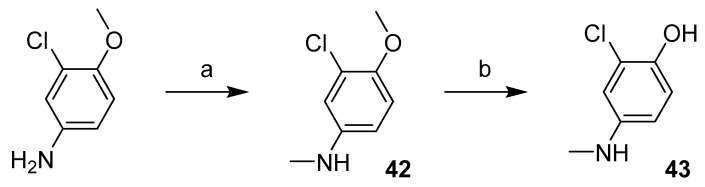

The first step in the synthesis of products 45, 46 and 49 was to prepare corresponding N-methylated phenyl moieties in one (N-methylation with methyl iodide) or actually two steps (O-demethylation using AlCl3) as shown in Scheme 11.

Scheme 11.

Synthesis of N-methylated aniline derivatives. Reagents and conditions: (a) CH3I, NaH, THF, 0 °C–RT; (b) AlCl3, toluene, reflux.

2-chloro-4-(methylamino)phenol (43) was then treated with the corresponding intermediate (44 and 1) produced in the reaction of benzothiazole-2-amine and 6-methoxybenzothiazole-2-amine with CDI (Scheme 12a) to give final products 45 and 46.

Scheme 12.

Synthesis of compound with methylated urea linker. Reagents and conditions: (a) CDI, DCM, RT. (b) amine, MeCN, reflux. (c) CH3I, NaH, DMF, 0 °C–RT; (d) AlCl3, toluene, reflux.

Synthesis of final product 49 started with preparation of 3-(benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-1-(3-chloro-4-methoxyphenyl)-1-methylurea (47) from the two previously generated intermediates 42 and 44 (Scheme 12). Compound 47 was then treated with methyl iodide to methylate the other nitrogen on the urea linker (48). Finally, O-demethylation using AlCl3 gave the desired product 49 (Scheme 12).

The third series of compounds (Table 3) focused on evaluating substitutions within the benzothiazole ring, predominantly to exploit position 6, a key area highlighted previously [9]. Our previous findings indicated that a 6-trifluromethoxy moiety and a 6-halogen moiety, led to an increased inhibitory ability towards 17β-HSD10.

Table 3.

Third series of prepared compounds (61–67).

| Compound ID | R |

|---|---|

| 61 | i-propyl |

| 62 | t-butyl |

| 63 | -OEt |

| 64 | -SCF3 |

| 65 | -SCN |

| 66 | -SO2Me |

| 67 | -SO2CF3 |

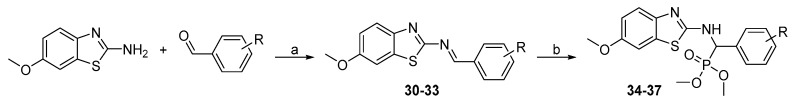

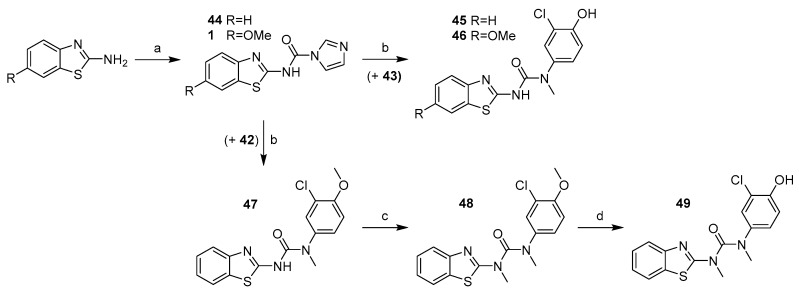

If not commercially available, the 6-substituted benzothiazole-2-amines were prepared from the corresponding 4-substituted anilines in reaction with potassium isocyanate and bromine (50, 51) or potassium isocyanate and tetramethylammonium dichloroiodate (52). 6-thiocyanatobenzothiazol-2-amine (53) was obtained as a by-product during preparation of 6-iodobenzo[d]thiazol-2-amine (Scheme 13). The synthesis proceeded according to the general procedure using CDI to give intermediates (54–60) and final products 61–67 (Scheme 13).

Scheme 13.

Synthesis of 6-substituted benzothiazoles. Reagents and conditions: (a1) KSCN, Br2, acetic acid, 10 °C–RT; (a2) KSCN, tetramethylammonium dichloroiodate, DMSO/water, RT–70 °C; (b) CDI, DCM, RT; (c) 4-amino-2-chlorophenol, MeCN, reflux.

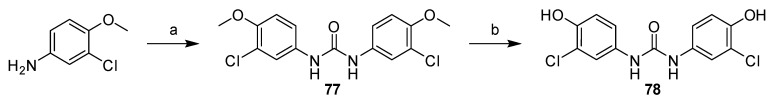

In the fourth series the benzothiazole heterocycle itself became the subject of modifications (as indicated in Table 4). The benzene ring was replaced with a saturated cyclohexane (71), separated (73) or completely removed (74), and the thiazole ring was replaced with an aliphatic cyclopentane (72) or replaced with an ethylene bridge (75). Further, the whole benzothiazole moiety was flipped and attached to urea via carbon in position 6 of the heterocycle. Moreover, the symmetric derivative (78) was prepared to find out whether the dimerized phenyl moiety alone is sufficient for 17β-HSD10 inhibition.

Table 4.

Fourth series of prepared compounds (71–78).

| Compound ID | R |

|---|---|

| 71 |

|

| 72 |

|

| 73 |

|

| 74 |

|

| 75 |

|

| 76 |

|

| 78 |

|

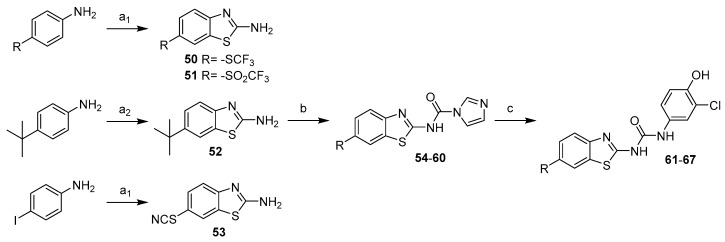

The general procedure for synthesis of the urea molecules described earlier in the text (Scheme 1) was only suitable for compounds comprising the 2-aminothiazole core (imidazolecarboxamide intermediates 68–70 and final products 71, 73 and 74). Therefore, for compounds 72, 75 and 76, the synthesis procedure had to be updated due to an increase in the solubility of imidazolecarboxamide intermediates, which did not allow for their simple isolation by filtration in satisfactory yields. Consequently, after the activation of starting compound with CDI was completed, 4-amino-2-chlorophenol was added directly to the current reaction mixture (Scheme 14).

Scheme 14.

One-pot synthesis of phenylureas 72, 75 and 76.

The symmetric 1,3-bis(3-chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)urea (78) was prepared in two steps (Scheme 15). First, 3-chloro-4-methoxyaniline was treated with CDI to give 1,3-bis(3-chloro-4-methoxyphenyl)urea (77), which was then O-demethylated in reaction with AlCl3.

Scheme 15.

Synthesis of symmetric urea derivative 78. Reagents and conditions: (a) CDI, DMF, 60 °C; (b) AlCl3, toluene, reflux.

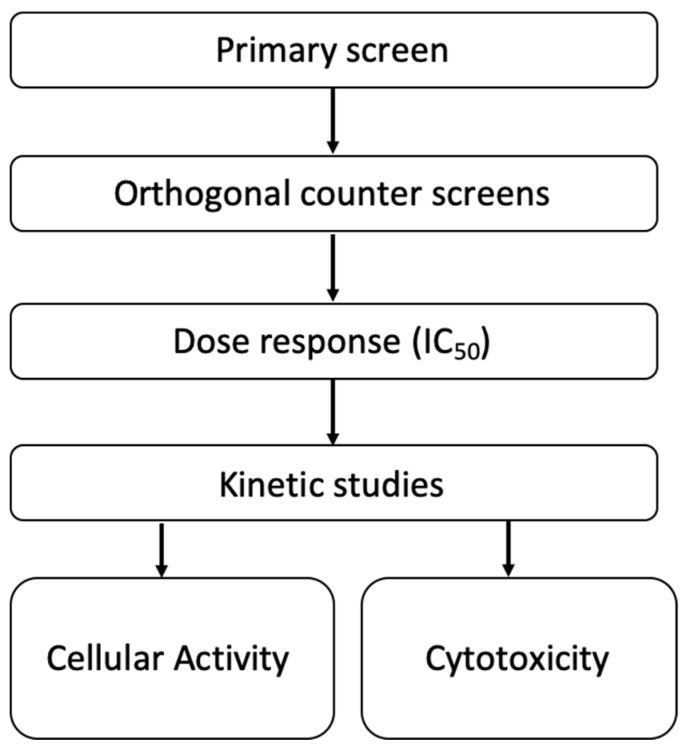

2.2. Biochemical and Biophysical Evaluation

In order to reduce attrition rates and improve assay reproducibility we have developed a high throughput screening (HTS) pipeline (Figure 3 [19]). In brief, compounds are screened in the recombinant 17β-HSD10 enzyme activity assay (Table 5, Figure 4). Our best previously published compounds have set the threshold of 40% remaining 17β-HSD10 activity as a minimum standard [9] and if compounds can better this threshold, they are further screened using our orthogonal counter assays, dose response assays and kinetic assessment (Table 5). Finally, if passing these criteria with favourable characteristics, the compounds progress into cellular evaluation through cytotoxicity testing and measuring 17β-HSD10 activity within cells (Table 6).

Figure 3.

Compound screening pipeline.

Table 5.

Biophysical characterisation of compound of interest.

| Compound ID | IC50 Values (μM) | Mechanism of Inhibition with Respect to Both Acetoacetyl-CoA and NADH | Orthogonal Counter Screens: Evidence of Aggregation or Redox Cycling |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 1.28 (95% CI 1.12–1.46) |

Mixed | None |

| 6 | 1.86 (95% CI 1.54–2.26) |

Mixed | None |

| 61 | 5.12 (95% CI 4.61–5.69) |

Mixed | None |

| 62 | 5.29 (95% CI 4.54–6.15) |

Mixed | None |

| 63 | 1.61 (95% CI 1.41–1.83) |

Mixed | 61% increase in 17β-HSD10 activity within aggregation assay |

| 64 | 5.21 (95% CI 4.42–6.13) |

Mixed | None |

| 65 | 2.61 (95% CI 2.31–2.94 |

Mixed | 28.5% increase in 17β-HSD10 activity within aggregation assay |

| 66 | 0.93 (95% CI 0.82–1.05) |

Mixed | None |

| 67 | 2.69 (95% CI 2.36–3.05) |

Mixed | 12.6% increase in 17β-HSD10 activity within aggregation assay |

| 78 | 6.83 (95% CI 5.34–8.75) |

Mixed | None |

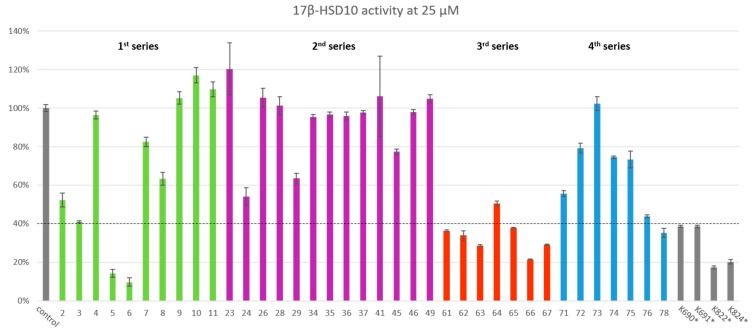

Figure 4.

Primary compound in vitro evaluation (relative remaining activity at 25 µM inhibitor concentration is displayed in percentage of six independent measurements ± SEM; detailed results in Supplementary data). * Authors’ previously published most potent enzymatic data from Hroch et al. 2016 (Design, synthesis and in vitro evaluation of benzothiazole-based ureas as potential ABAD/17β-HSD10 modulators for Alzheimer’s disease treatment) [9].

Table 6.

Cellular cytotoxicity and potency testing in HEK293 mts17β-HSD10 cells.

| Compound ID | (−)-CHANA IC50 Values (μM) | LDH Cytotoxicity with 100 μM Compound | LDH Cytotoxicity with 25 μM Compound |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 10.39 (95% CI 5.50–19.96) | 20.13 ± 4.26 | 13.28 ± 0.55 |

| 6 | 17.04 (95% CI 9.15–31.73) | 23.97 ± 3.32 | 23.54 ± 3.02 |

| 61 | 7.88 (95% CI 5.07–12.07) | 55.68 ± 2.55 | 28.83 ± 0.67 |

| 62 | 3.77 (95% CI 2.11–6.74) | 64.40 ± 3.62 | 27.25 ± 3.35 |

| 63 | 2.29 (95% CI 1.74–3.01) | 18.05± 0.96 | 15.98 ± 1.02 |

| 64 | - | 33.35 ± 2.92 | 22.83 ± 0.63 |

| 65 | 88.95 (95% CI 28.39–278.7) | 27.41 ± 2.65 | 11.27 ± 0.58 |

| 66 | - | 17.51± 0.46 | 13.59 ± 0.66 |

| 67 | - | 36.05 ± 1.75 | 22.68 ± 2.68 |

| 78 | - | 12.41 ± 0.64 | 11.34 ± 0.41 |

2.3. Primary Enzyme Assay Results

Full results for the primary nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) assay screens are shown in Figure 4 including our four best previously published compounds for comparison (Figure 1) [9].

Our first analogue series (2–11; Table 1 and Figure 4) focused on establishing how alterations to the 3 and 4 position on the distal (phenolic) ring affect inhibition potency. In this series, compounds 5 and 6 showed a huge improvement in potency with remaining 17β-HSD10 activity of 13.45% and 6.72%, respectively, at 25 μM. A significant finding from our previous work indicated that a p-hydroxy along m-chlorine substitution pattern displayed the most pronounced inhibitory activity [9], and a deviation from the 3-halogen and 4-hydroxyl pattern resulted in a dramatic decrease in 17β-HSD10 inhibition. Our findings in this series further support this, and establish that the bulkier, 3-bromo and 3-iodo substitutions are even more favourable at this position. Replacement of the phenolic hydroxyl with an amine or methylhydroxy group led to loss of activity, which further confirms the importance of the 4-positioned phenolic hydroxyl as was previously suggested [9].

The second analogue series (23–49; Table 2) focused on evaluating changes to the urea linker. Unfortunately, any variation from the urea linker resulted in a dramatic decrease of inhibitory activity (Figure 4). This was further supported by the inclusion of compounds (34–36) previously published by Valasani et al. with the inclusion of our novel phosphonate compound (37) determining that a phosphonate linker did not increase 17β-HSD10 inhibition. Indeed, all linker variations resulted in negligible changes to 17β-HSD10 activity with the exception of compound 24. Although the secondary amide substitution (with amide nitrogen attached to benzothiazole moiety) in compound 24 appeared slightly more favourable than most, it was still not as potent as the original urea moiety and just outside of the threshold for further analysis at 47.19% 17β-HSD10 activity remaining at 25 μM (Figure 4). Mono and dimethylation of the urea linker to enforce sp3, rather than sp2 character, showed a clear detrimental effect on the activity in compound 45–49.

The third series of compounds (61–67) focused on evaluating substitutions within the benzothiazole ring, predominantly to exploit position 6, a key area highlighted previously (Hroch et al. 2016). Our previous findings indicated that a 6-trifluromethoxy moiety and a 6-halogen moiety led to an increased inhibitory ability towards 17β-HSD10. This series appear to be the most promising displaying the largest decrease in 17β-HSD10 activity (indicated in Figure 4), in particular when bulky substitutions at position 6 were applied. This is particularly apparent in compounds 61 and 62 whereby, as the functional group size increases at position 6, 17β-HSD10 activity decreases with 6-t-butyl (62) inhibiting 17β-HSD10 by 78.36% and the 6-isopropyl substitution (61) inhibiting 17β-HSD10 by 77.37% at 25 μM. Other key structure activity relationships in this series have been established through 6-thiol additions (64–67). Again, bulkier substituents produce a larger inhibitory effect with the 6-sulfonyl (66) less effective than the 6-trifluoromethylsulfonyl (67) with 32.16% and 16.16% 17β-HSD10 activity remaining at 25 μM. The most potent compound in this series (65) introduced the pseudo-halogenic 6-thiocyanate moiety, which inhibited 17β-HSD10 activity by 85.69% at 25 μM.

In order to validate the importance of the benzothiazol-2-yl moiety, several structural analogues were prepared and evaluated in the fourth series (71–78; Table 4). Indeed, any deviation from the benzothiazol-2-yl moiety resulted in decreased biological activity and only the symmetrical compound (78) showed real inhibitory activity with 17β-HSD10 activity reduced to 40.69% at 25 μM (Figure 4).

Overall, after primary screening we were left with 10 compounds which would progress down the pipeline: compounds 5, 6, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 and 78.

2.4. Orthogonal Counter Screens

During our enzymatic assay development, it was noted that the assay was susceptible to false positives through redox cycling and aggregation mechanism [19], therefore, two orthogonal counter screens have been implemented to validate the primary screen results. The addition of the detergent Triton X-100 to the assay buffer prevents the hydrophobic interactions required for aggregation, by which a reduction in inhibition in the presence of Triton X-100 indicates the undesirable inhibitory mode of action whereby, the compound could be potentially inhibiting the enzyme through the indirect sequestration of the protein. Results (Table 5) identify compound 63 as a potential aggregator as it showed a 61% increase in 17β-HSD10 activity in the presence of Triton-X100. Compounds 65 and 67 also showed some reduction in activity but this is much less pronounced. Given that these three compounds were part of a small series we decided to advance them into the next step of screening.

With the inclusion of the strong reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT) in the assay buffer, compounds can appear as a false positive as DTT is capable of generating H2O2 causing indirect enzyme inhibition and assay interference. The fluorescence change during the reduction of resazurin to resorufin can be measured as an indication of any redox cycling compounds. The results indicate that none of the compounds appear to be acting via this undesirable mode of action (Table 5).

2.5. Dose Response and Kinetic Evaluation

Our most promising compounds demonstrate reasonable IC50 values of around 1–2 μM (Table 5 and graphs in Supplementary data). Significantly, these compounds all display a mixed mechanism of inhibition with respect to both substrate acetoacetyl-Coenzyme A and co-factor NADH whereby at low concentrations they appear to act in a competitive manner, but at high concentrations they are inhibiting in other sites (Table 5, Hanes–Woolf plots in Supplementary data). This is favourable over other previously published work [7,20] as the AG18051 compound irreversibly inhibits 17β-HSD10, forming a covalent adduct with NADH at the active site, thus introducing a potential specificity issue.

2.6. Cellular Screening

Compound toxicity and potency was also assessed using HEK293 mts17β-HSD10 cells; results are shown in Table 6. Our fluorogenic probe, (−)-CHANA, a 17β-HSD10 substrate [21] was used to calculate cellular IC50 values (graphs in Supplementary data) with the exception of compounds 64, 66, 67 and 78, which were precipitating within the assay media and not able to effectively penetrate into cells. Compounds 61, 62 and 63 proved to be the most potent in our cellular assay with IC50 values of 7.88, 3.77 and 2.29 μM, respectively.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is a colorimetric assay routinely used to quantitatively measure LDH released into the media from damaged cells as a biomarker for cellular cytotoxicity and cytolysis. HEK293 mts17β-HSD10 cells were treated with compound (100 and 25 μM) for 24 h before measurements were taken. At 25 μM compounds showed around 10–30% cytotoxicity, however, this concentration is substantially higher than the measured IC50 values and as such is not a cause for concern. Compound 65 showed a remarkably higher IC50 value in the (−)-CHANA assay which suggests that the uptake of compound by cells and 17β-HSD10 target engagement is not as favourable as others.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Chemistry

All reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial sources (Sigma Aldrich, Prague, Czech Republic; Activate Scientific, Prien, Germany; Alfa Aesar, Kandel, Germany; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany; Penta Chemicals, Prague, Czech Republic and VWR, Stribrna Skalice, Czech Republic) and they were used without any further purification. Low boiling point (≥90% 40–60 °C) petroleum ether (PE) was used if not stated otherwise.

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) for reaction monitoring was performed on Merck aluminium sheets, silica gel 60 F254 (Darmstadt, Germany). Visualisation was performed either via UV (254 nm) or appropriate stain reagent solutions (alternatively in combination of both). Preparative column chromatography was performed on silica gel 60 (70–230 mesh, 63–200 μm, 60 Å pore size). Melting points were determined on a Stuart SMP30 melting point apparatus and are uncorrected.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were acquired at 500/126/202 MHz (1H, 13C and 31P) on a Varian S500 spectrometer or at 300/75 MHz (1H and 13C) on a Varian Gemini 300 spectrometer (both produced by Palo Alto, CA, USA). Chemical shifts δ are given in ppm and referenced to the signal center of solvent peaks (DMSO-d6: δ 2.50 ppm and 39.52 ppm for 1H and 13C, respectively; Chloroform-d: δ 7.26 ppm and 77.16 ppm for 1H and 13C, respectively), thus indirectly correlated to TMS standard (δ 0 ppm). Chemical shifts δ for 31P are given in ppm and referenced to the phosphoric acid standard (δ 0 ppm). Coupling constants are expressed in Hz.

High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded by coupled LC-MS system consisting of Dionex UltiMate 3000 analytical LC system and Q Exactive Plus hybrid quadrupole-orbitrap spectrometer (both produced by ThermoFisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). As an ion-source, heated electro-spray ionization (HESI) was utilised (setting: sheath gas flow rate 40, aux gas flow rate 10, sweep gas flow rate 2, spray voltage 3.2 kV, capillary temperature 350 °C, aux gas temperature 300 °C, S-lens RF level 50). Positive ions were monitored in the range of 100–1500 m/z with the resolution set to 140,000. Obtained mass spectra were processed in Xcalibur 3.0.63 software (ThermoFisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany).

Further synthetic information can be found in the Supplementary material.

3.2. Final Products Characterization

The purification method is specified here only when altered from the generally used method described in Supplementary information.

1-(4-Hydroxy-3-methylphenyl)-3-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (2) Yield 85%; mp: 262–263 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.55 (br s, 1H), 9.09 (s, 1H), 8.77 (s, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 2.12 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 157.57, 155.61, 151.75, 151.47, 142.84, 132.53, 129.56, 124.11, 122.24, 120.13, 118.18, 114.64, 114.29, 104.87, 55.60, 16.12; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C16H16N3O3S [M + H]+ 330.09069, found 330.09039.

1-(3-(Tert-butyl)-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (3) Yield 73%; mp: 259–260 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.47 (br s, 1H), 9.18 (br s, 1H), 8.79 (s, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 1.35 (s, 9H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 157.50, 155.61, 151.91, 151.84, 142.82, 135.53, 132.60, 129.43, 120.20, 118.58, 118.38, 116.13, 114.28, 104.90, 55.62, 34.35, 29.25; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C19H22N3O3S [M + H]+ 372.13764, found 372.13730.

1-(3-Cyano-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (4) Yield 98%; mp: 277–279 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.86 (s, 1H), 9.37 (s, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 7.56 – 7.52 (m, 2H), 7.51 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.01 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 157.84, 156.05, 155.71, 152.44, 141.78, 132.24, 130.54, 126.52, 122.87, 119.79, 116.80, 116.73, 114.40, 105.00, 98.49, 55.61; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C16H12N4O3S [M + H]+ 341.07029, found 341.07016.

1-(3-Bromo-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (5) Yield 82%; mp: 246–247 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.71 (br s, 1H), 9.99 (s, 1H), 8.97 (s, 1H), 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (s, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 157.84, 155.67, 152.21, 149.97, 142.25, 132.33, 131.04, 123.65, 120.14, 119.87, 116.28, 114.37, 108.86, 104.95, 55.61; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H13BrN3O3S [M + H]+ 393.98555, found 393.98489.

1-(4-Hydroxy-3-iodophenyl)-3-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (6) Yield 85%; mp: 241–242 °C; 1H-NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.07 (br s, 1H), 9.05 (s, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 157.72, 155.67, 152.67, 152.10, 142.15, 132.35, 131.29, 129.42, 120.99, 119.93, 114.75, 114.38, 104.93, 84.10, 55.62; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H13IN3O3S [M + H]+ 441.97168, found 441.97049.

1-(3-Amino-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (7) Yield 53%; mp: 180–181 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.41 (br s, 1H), 8.76 (br s, 1H), 8.65 (s, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.57 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 4.61 (s, 2H), 3.79 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 157.45, 155.57, 151.34, 143.00, 140.11, 136.90, 132.57, 130.42, 122.10, 120.22, 114.24, 107.26, 106.17, 104.84, 55.58; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H15N4O3S [M + H]+ 331.08594, found 331.08527.

1-(6-Hydroxypyridin-3-yl)-3-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (8) Yield 82%; mp: 272–273 °C; 1H-NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.38 (br s, 1H), 9.08 (br s, 1H), 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 7.53 – 7.39 (m, 2H), 6.97 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.36 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 160.85, 158.50, 155.83, 153.21, 142.19, 138.04, 132.42, 127.92, 120.11, 119.28, 119.17, 114.49, 105.11, 55.78; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C14H13N4O3S [M + H]+ 317.07029, found 317.07004.

1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (9) Yield 93%; mp: 304–306 °C (decomp); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.46 (br s, 1H), 8.63 (s, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.15 – 7.10 (m, 2H), 6.96 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.57 – 6.52 (m, 2H), 4.90 (s, 2H), 3.79 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 157.58, 155.56, 151.75, 144.96, 142.74, 132.56, 127.01, 121.23, 120.12, 114.23, 114.05, 104.87, 55.58; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H15N4O2S [M + H]+ 315.09102, found 315.09058.

1-(4-Amino-3-chlorophenyl)-3-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (10) Yield 78%y mp: 310-311 °C (decomp); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.60 (br s, 1H), 8.82 (s, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 5.14 (s, 2H), 3.79 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 157.69, 155.61, 151.90, 140.78, 132.42, 128.05, 120.50, 120.23, 119.97, 116.77, 115.48, 114.29, 104.91, 55.59; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H14ClN4O2S [M + H]+ 349.05205, found 349.05154.

1-(3-Chloro-4-(hydroxymethyl)phenyl)-3-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (11) Yield 92%; mp: 229–230 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.84 (br s, 1H), 9.26 (s, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 5.29 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 4.53 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 157.75, 155.74, 152.27, 138.45, 133.63, 132.18, 131.19, 128.67, 127.18, 119.85, 118.56, 117.35, 114.44, 105.01, 59.99, 55.61; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C16H15ClN3O3S [M + H]+ 364.05172, found 364.05103.

2-Chloro-4-((6-chlorobenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)amino)phenol (23) Yield 30%; mp: 213–214.5 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.49 (br s, 1H), 9.92 (br s, 1H), 7.94 – 7.85 (m, 2H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.53, 150.83, 148.56, 132.94, 131.53, 126.01, 125.88, 120.74, 119.86, 119.74, 119.43, 118.46, 116.87; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C13H8Cl2N2OS [M + H]+ 310.98072, found 310.98016.

3-Chloro-4-hydroxy-N-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)benzamide (24) Yield 69%; mp: 301.5–302.5 °C; 1H-NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 12.51 (br s, 1H), 11.25 (br s, 1H), 8.21 (s, 1H), 7.97 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (s, 1H), 7.17 – 6.96 (m, 2H), 3.82 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 164.08, 157.27, 156.85, 156.21, 142.57, 132.85, 130.34, 128.93, 123.50, 120.96, 119.89, 116.34, 115.00, 104.66, 55.64; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H11ClN2O3S [M + H]+ 335.02517, found 335.02466.

N-(3-Chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazole-2-carboxamide (26) Yield 58%; mp: 260–261.5 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.94 (br s, 1H), 10.09 (br s, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.94 (s, 1H), 7.80 (s, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 3.88 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 161.76, 158.62, 157.88, 149.87, 147.05, 138.22, 130.34, 124.71, 122.22, 120.81, 119.09, 117.30, 116.36, 104.79, 55.84; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H11ClN2O3S [M + H]+ 335.02517, found 335.02466.

1-(3-Chloro-4-hydroxybenzyl)-3-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (28)

The crude product was purified using column chromatography.

Yield 20%; mp: 249–251 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.60 (br s, 1H), 10.08 (br s, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 6.98 – 6.90 (m, 2H), 4.25 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 3.78 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 157.80, 155.52, 153.84, 152.01, 143.16, 132.59, 131.25, 128.80, 127.18, 120.19, 119.37, 116.54, 114.15, 104.81, 55.57, 42.01; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C16H14ClN3O3S [M + H]+ 364.05172, found 364.05115.

1-(3,4-Dihydroxybenzyl)-3-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (29)

After the reaction was completed (monitored by TLC), 1M aq. HCl was poured to the reaction mixture and the product was extracted to DCM. The organic layer was concentrated and the crude product was recrystallized from MeCN.

Yield 50%; mp: 141.5–142 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 7.51 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (br s, 1H), 6.95 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.71 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.68 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.56 (dd, J = 8.0, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 3.78 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 158.51, 155.74, 153.64, 145.23, 144.41, 141.36, 131.95, 129.93, 119.61, 118.26, 115.49, 114.93, 114.45, 105.07, 55.65, 42.68; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C16H15N3O4S [M + H]+ 346.08560, found 346.08517.

Dimethyl ((4-fluorophenyl)((6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)amino)methyl) phosphonate (34) (Valasani et al. 2013).

Yield 65%; mp: 173–174 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 9.48 (s, 1H), 8.76 (dd, J = 9.7, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 7.33 – 7.27 (m, 4H), 6.82 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 5.54 (dd, J = 20.9, 9.7 Hz, 1H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 3.64 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 3H), 3.50 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 163.62 (d, J = 10.0 Hz), 161.69 (dd, J = 244.1, 2.9 Hz), 154.67, 145.52, 132.10 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 131.87, 130.02 (dd, J = 8.3, 5.5 Hz), 118.79, 115.18 (dd, J = 21.6, 1.7 Hz), 113.09, 105.58, 53.53 (d, J = 6.8 Hz), 53.25 (d, J = 6.8 Hz), 53.12 (d, J = 154.1 Hz); 31P NMR (202 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 23.56 (d, J = 4.5 Hz); HRMS (ESI) calcd for C17H19FN2O4PS [M + H]+ 397.07817, found 397.07755.

Dimethyl ((4-hydroxyphenyl)((6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)amino)methyl) phosphonate (35) (Valasani et al. 2013). Yield 76%; mp: 217–218 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 9.48 (s, 1H), 8.76 (dd, J = 9.7, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 7.33 – 7.28 (m, 4H), 6.82 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 5.54 (dd, J = 20.9, 9.7 Hz, 1H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 3.64 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 3H), 3.50 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 163.70 (d, J = 10.0 Hz), 157.06 (d, J = 2.4 Hz), 154.57, 145.64, 131.82, 129.31 (d, J = 5.7 Hz), 125.77, 118.68, 115.08, 113.01, 105.57, 55.53, 53.33 (d, J = 6.9 Hz), 53.28 (d, J = 155.2 Hz), 53.14 (d, J = 6.9 Hz); 31P NMR (202 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 24.25; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C17H20N2O5PS [M + H]+ 395.08251, found 395.08215.

Methyl 5-((dimethoxyphosphoryl)((6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)amino)methyl)-2- hydroxybenzoate (36) (Valasani et al. 2013) Yield 73%; mp: 180–181 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.53 (s, 1H), 8.90 (dd, J = 9.6, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (t, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (dt, J = 8.7, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.01 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 5.63 (dd, J = 21.3, 9.4 Hz, 1H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 3.67 (d, J = 10.6 Hz, 3H), 3.55 (d, J = 10.6 Hz, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 168.86, 163.61 (d, J = 10.1 Hz), 159.53 (d, J = 2.0 Hz), 154.65, 145.52, 135.35 (d, J = 5.1 Hz), 131.88, 129.33 (d, J = 6.0 Hz), 126.83, 118.79, 117.49, 105.58, 113.07, 113.03 (d, J = 1.9 Hz), 55.53, 53.55 (d, J = 7.1 Hz), 53.26 (d, J = 6.8 Hz), 52.90 (d, J = 155.2 Hz), 52.53; 31P NMR (202 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 23.67; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C19H22N2O7PS [M + H]+ 453.08798, found 453.08701.

Dimethyl ((3-chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)((6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)amino)methyl) phosphonate (37) Yield 65%; mp: 198–199 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.28 (s, 1H), 8.77 (dd, J = 9.7, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (t, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (dt, J = 8.5, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 5.57 (dd, J = 21.0, 9.6 Hz, 1H), 3.73 (s, 3H), 3.66 (d, J = 10.6 Hz, 3H), 3.55 (d, J = 10.6 Hz, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 163.76 (d, J = 10.1 Hz), 154.82, 152.90 (d, J = 2.4 Hz), 145.72, 132.01, 129.40 (d, J = 5.4 Hz), 128.12 (d, J = 5.9 Hz), 127.58, 119.66 (d, J = 2.2 Hz), 118.94, 116.52, 113.25, 105.76, 55.71, 53.66 (d, J = 6.8 Hz), 53.41 (d, J = 7.0 Hz), 52.95 (d, J = 155.3 Hz); 31P NMR (202 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 23.71; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C17H19ClN2O5PS [M + H]+ 429.04353, found 429.0425.

1-(Benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-3-(3-chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-methylurea (41) Yield 83%; mp: 171–172 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.02 (s, 1H), 9.47 (s, 1H), 7.94 – 7.84 (m, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.45 – 7.35 (m, 1H), 7.31 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.28 – 7.19 (m, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 3.75 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 161.45, 153.45, 149.66, 148.45, 132.76, 130.50, 125.80, 123.42, 123.09, 121.95, 121.12, 120.29, 119.01, 116.29, 34.55 (d, J = 3.0 Hz); HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H12ClN3O2S [M + H]+ 334.04115, found 334.04080.

3-(Benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-1-(3-chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-methylurea (45)

The crude product was dissolved in Et2O and filtered. To the filtrate was added PE and the solution was left to crystallize in a freezer. Filtration gave the desired pure product.

Yield 53%; mp: 139–141 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.28 (br s, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (br s, 1H), 7.38 – 7.30 (m, 2H), 7.19 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.26 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 151.90, 135.11, 128.70, 126.89, 125.94, 122.65, 121.62, 119.46, 116.66, 37.93; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H12ClN3O2S [M + H]+ 334.0412, found 334.0414.

1-(3-Chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(6-methoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-1-methylurea (46)

The crude product was purified using column chromatography.

Yield 50%; mp: 220 °C decomp.; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.28 (br s, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.25 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 155.57, 151.97, 134.94, 131.53, 128.78, 126.95, 119.52, 118.40, 116.70, 114.18, 105.12, 55.60, 37.94; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C16H14ClN3O3S [M + H]+ 364.0517, found 364.0530.

1-(Benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-3-(3-chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-1,3-dimethylurea (49) Yield 65%; mp: 227–228.5 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.09 (s, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.47 – 7.37 (m, 2H), 7.36 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 165.20, 160.92, 150.53, 137.50, 136.58, 127.60, 126.56, 125.93, 125.38, 123.01, 122.40, 118.67, 115.86, 111.35, 37.16, 31.51; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C16H14ClN3O2S [M + H]+ 348.05680, found 348.05661.

1-(3-Chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(6-isopropylbenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (61) Yield 43%; mp: 246–248 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.83 (br s, 1H), 9.91 (br s, 1H), 9.02 (s, 1H), 7.74 (s, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 2.97 (sept, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 1.23 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 6H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 159.33, 152.47, 148.89, 146.08, 143.46, 131.02, 130.84, 124.67, 120.74, 119.41, 119.33, 118.68, 116.64, 33.41, 24.17; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C17H16ClN3O2S [M + H]+ 362.0725, found 362.0721.

1-(6-(Tert-butyl)benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-3-(3-chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)urea (62) Yield 66%; mp: 238–240 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 9.75 (s, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 1.32 (s, 9H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 159.43, 152.17, 148.89, 145.88, 145.02, 130.87, 130.77, 123.74, 120.40, 119.36, 119.08, 118.41, 117.78, 116.74, 34.62, 31.45; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C18H18ClN3O2S [M + H]+ 376.0881, found 376.0882.

1-(3-Chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(6-ethoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (63) Yield 90%; mp: 255–257 °C; 1H-NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.72 (br s, 1H), 9.92 (s, 1H), 9.00 (s, 1H), 7.60 (s, 1H), 7.57–7.36 (m, 2H), 7.18 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.04 – 6.84 (m, 2H), 4.04 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.33 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H); 13C-NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 157.76, 154.90, 152.19, 148.90, 141.98, 132.33, 130.82, 120.74, 119.89, 119.41, 119.34, 116.67, 114.76, 105.59, 63.59, 14.75; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C16H14ClN3O3S [M + H]+ 364.0517, found 364.0521.

1-(3-Chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(6-((trifluoromethyl)thio)benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (64) Yield 24%; mp: 256–258 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.04 (br s, 1H), 9.95 (br s, 1H), 9.03 (s, 1H), 8.37 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.27, 152.10, 150.64, 149.08, 134.08, 132.73, 130.61, 130.28, 129.69 (q, J = 308.1 Hz), 120.65, 120.34, 119.38, 119.33, 116.74, 115.69 (q, J = 2.1 Hz); HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H9ClF3N3O2S2 [M + H]+ 419.9850, found 419.9873.

1-(3-Chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(6-thiocyanatobenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (65) Yield 80%; mp: 251–253 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.04 (br s, 1H), 9.97 (br s, 1H), 9.13 (br s, 1H), 8.32 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 161.91, 152.15, 149.47, 149.14, 133.11, 130.46, 129.54, 125.55, 121.00, 120.73, 119.66, 119.35, 116.75, 116.66, 112.20; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H9ClN4O2S2 [M + H]+ 376.9928, found 376.9939.

1-(3-Chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(6-(methylsulfonyl)benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (66) Yield 78%; mp: 293–295 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.16 (br s, 1H), 9.94 (br s, 1H), 9.25 (s, 1H), 8.55 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 3.23 (s, 3H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 163.39, 152.08, 149.15, 134.69, 131.79, 130.45, 124.81, 121.71, 120.89, 119.56, 119.36, 116.68, 44.09; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H12ClN3O4S2 [M + H]+ 398.0031, found 398.0048.

1-(3-Chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(6-((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (67) Yield 94%; mp: 267–269 °C; 1H-NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.40 (br s, 1H), 10.01 (s, 1H), 9.10 (br s, 1H), 8.89 (s, 1H), 8.02 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H); 13C-NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 166.05, 155.92, 149.35, 133.47, 130.23, 128.07, 126.29, 121.75, 121.17, 119.85, 119.36, 117.44, 116.67, 40.35, 40.08, 39.80, 39.52, 39.24, 38.96, 38.69; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H9ClF3N3O4S2 [M + H]+ 451.9748, found 451.9749.

1-(3-Chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(4,5,6,7-tetrahydrobenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)urea (71) Yield 58%; mp: 258–260 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 9.91 (br s, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 2.59 (s, 2H), 2.54 (s, 2H), 1.75 (s, 4H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 158.38, 151.01, 149.02, 138.46, 130.54, 120.47, 120.31, 119.38, 119.00, 116.77, 24.13, 22.46, 22.07, 21.82; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C14H14ClN3O2S [M + H]+ 324.05680, found 324.05634.

1-(3-Chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-2-yl)urea (72) Yield 21%; mp: 203–205 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 9.59 (br s, 1H), 8.14 (br s, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.29 – 7.19 (m, 2H), 7.19 – 7.10 (m, 2H), 6.97 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 6.36 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 4.48 – 4.31 (m, 1H), 3.25 – 3.09 (m, 2H), 2.84 – 2.67 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 155.00, 147.38, 141.23, 132.93, 126.40, 124.56, 119.34, 119.16, 117.90, 116.55, 50.77, 39.70; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C16H15ClN2O2 [M + H]+ 303.08948, found 303.08908.

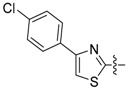

1-(3-Chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(4-(4-chlorophenyl)thiazol-2-yl)urea (73) Yield 71%; mp: 206–208 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 10.69 (s, 1H), 9.91 (s, 1H), 8.76 (s, 1H), 7.92 – 7.87 (m, 2H), 7.60 – 7.57 (m, 2H), 7.50 – 7.45 (m, 2H), 7.14 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 159.31, 151.59, 148.87, 147.41, 133.16, 132.07, 130.69, 128.67, 127.26, 120.67, 119.34, 116.66, 107.89; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C16H11Cl2N3O2S [M + H]+ 380.00218, found 380.00168.

1-(3-Chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(thiazol-2-yl)urea (74) Yield 74%; mp: 220–222 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 9.83 (s, 1H), 9.81 (s, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (dd, J = 3.9, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (dd, J = 3.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 160.49, 151.25, 149.00, 133.59, 130.64, 120.41, 119.39, 119.08, 116.78, 113.06; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C10H8ClN3O2S [M + H]+ 270.0099, found 270.0099.

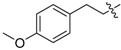

1-(3-Chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenethyl)urea (75) Yield 21%; mp: 161.5–163.5 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 9.58 (br s, 1H), 8.29 (br s, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.97 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.89–6.84 (m, 2H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 5.98 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 3.72 (s, 3H), 3.33 – 3.19 (m, 2H), 2.66 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 157.65, 155.20, 147.32, 133.06, 131.35, 129.58, 119.37, 119.14, 117.90, 116.54, 113.78, 54.97, 40.87, 34.96; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C16H17ClN2O3 [M + H]+ 321.10005, found 321.09967.

1-(Benzo[d]thiazol-6-yl)-3-(3-chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)urea (76) Yield 24%; mp: 224–226 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 9.77 (s, 1H), 9.20 (s, 1H), 8.89 (s, 1H), 8.60 (s, 1H), 8.35 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 153.69, 152.69, 148.26, 148.17, 137.64, 134.46, 131.92, 122.92, 120.22, 119.26, 118.82, 118.11, 116.63, 110.26; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C14H10ClN3O2S [M + H]+ 320.0255, found 320.0264.

1,3-Bis(3-chloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)urea (78) Yield 94%; mp: 254.5–256.5 °C; 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 9.71 (br s, 2H), 8.43 (br s, 2H), 7.54 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 2H), 7.06 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 2H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H); 13C-NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 152.77, 147.99, 132.14, 120.11, 119.22, 118.71, 116.59; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C13H10Cl2N2O3 [M + H]+ 313.01412, found 313.01361.

3.3. β-HSD10 Enzymatic Activity Assay

Purification of 17β-HSD10 protein was performed as described in our previous work [22].

Compound screening, dose response and mechanism of inhibition experiments were performed as described in Hroch et al. 2016, with the exceptions being an alteration in assay buffer (10 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.005% Tween20, 0.01% BSA) and a change in temperature to 25 °C, to improve enzyme stability and assay reliability as compound solubility improved, as outlined in our previous work [19].

Orthogonal screening (small molecule aggregation and redox cycling experiments) was carried out as described in our previous work [19].

3.4. Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Cytotoxicity Assay

Cell cytotoxicity was assessed via the measurement of lactate dehydrogenase leakage into the culture medium using a commercially available kit from Pierce (Thermo Scientific, UK, cat no. 88953). This was carried out in accordance with the kit guidelines, with the activity of LDH being calculated from the change in absorbance at 340 nm as NADH is reduced. HEK293 cells overexpressing mts17β-HSD10 were cultured in phenol-red free media (10% FBS, 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate, 100 units Penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL Streptomycin and 2 mM L-Glutamine) and seeded at a density of 10,000 cells per well (100 µL, 96-well plates). Cells were then treated with compound of interest at 2 concentrations (25 µM and 100 µM in DMSO) in triplicate. Treated cells were then incubated at 37 °C and CO2 (5%) for 24 hours before the LDH assay was performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Spontaneous control (water) and maximum control (lysis buffer) used in accordance with the kit guide. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm and 680 nm using the SpectraMaxM2e spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). The measured LDH activity was used to calculate % cytotoxicity using the following equation:

| (1) |

3.5. (−)-CHANA Assay – In Vitro Dose Response and EC50 Determination

HEK293 mts17β-HSD10 cells were seeded at a density of 10,000 cells per well (100 µL, 96-well black plates, Greiner Cat no. 655090) in phenol-red free media (10% FBS, 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate, 100 units Penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL Streptomycin and 2 mM L-Glutamine). The media was removed from the cells and replaced with fresh media containing varying concentrations of compound (100 µM–0.098 µM). The fluorogenic probe (−)-CHANA was then added to each well to give a final assay concentration of 20 µM. Fluorescence was immediately measured using the FLUOstar Optima microplate reader (excitation = 380 nm, emission = 520 nm, orbital averaging = 3 mm) and the initial reaction monitored for 3–4 hours. EC50 was calculated from the control - subtracted triplicates using non-linear regression (four parameters) of GraphPad Prism 5 software. Final EC50 and SEM value was obtained as a mean of at least 3 independent measurements.

4. Conclusions

In summary, four novel series of benzothiazolylureas were designed and synthesised. All compounds were evaluated for 17β-HSD10 inhibitory ability in vitro, where compounds 5, 6, and 63 showed the most promising 17β-HSD10 inhibitory activity in our enzymatic assays, although the orthogonal screens appear to indicate that 63 could be inhibiting 17β-HSD10 in an unfavourable manner. Key structure–activity relationships have been established and further validated with a urea linker and a 4-phenolic moiety with a 3-halogen substitution confirmed to be essential for compound 17β-HSD10 inhibitory ability. Furthermore, a bulky substitution (e.g., t-butyl) in position 6 of the benzothiazole moiety appears to be the most promising, potentially occupying the chemical space more effectively within the binding site.

Positively the most promising compounds were also shown to have an inhibitory effect at a cellular level with limited cytotoxicity and all hit compounds display a more favourable kinetic mechanism of action (reversible mixed inhibition) to other previously published work.

These findings provide significant structural activity insight into our 17β-HSD10 inhibitor compound design and are our most promising observations to date. With further hit optimisation and neuronal cellular evaluation to determine if these compounds are protective against Aβ-mediated cytotoxicity, this could potentially lead to novel class of therapeutics for AD.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online, Figure S1: IC50 Graphs for compounds 5, 6, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 and 78, Figure S2: Hanes-Woolf kinetic plots for compounds 5, 6 and 61. Figure S3: Hanes-Woolf kinetic plots for compounds 62, 63 and 64. Figure S4: Hanes-Woolf kinetic plots for compounds 65, 66, 67 and 61. Figure S5: Cellular IC50 Graphs for compounds 5, 6, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 and 78. Table S1: Full primary screen compound in vitro evaluation. The research data supporting this publication can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.17630/a9bb5ff9-b6cf-4175-9840-961d4c47651a [23].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A., O.B., K.M. and F.J.G.-M.; Data curation, L.A. and O.B.; Formal analysis, L.A., B.E.M., R.E.H. and L.L.M.; Funding acquisition, L.A., T.K.S., K.M. and F.J.G.-M.; Investigation, L.A., O.B., B.E.M., R.E.H., L.H., M.S., L.L.M. and L.V.; Methodology, L.A., O.B. and L.H.; Resources, K.K., T.K.S., K.M. and F.J.G.-M.; Supervision, L.A., O.B., T.K.S., K.M. and F.J.G.-M.; Visualization, L.A.; Writing—original draft, L.A. and O.B.; Writing—review & editing, L.A., O.B., T.K.S. and K.M.

Funding

In the UK, this work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (204821/Z/16/Z), Alzheimer’s Society (specifically The Barcopel Foundation), Scottish Universities Life Science Alliance (SULSA), The Rosetrees Trust and RS MacDonald Charitable Trust. In the Czech Republic, this work was supported by Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of Czech Republic (project ESF no. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/18_069/0010054), Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic (no. NV19-09-00578) and University of Hradec Kralove (Faculty of Science, no. VT2019-2021, SV2115-2018, and Postdoctoral job positions at UHK).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of all the final compounds are available from the authors.

References

- 1.Muirhead K.E.A., Borger E., Aitken L., Conway S., Gunn-Moore F.J. The consequences of mitochondrial amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem. J. 2010;426:255–270. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borger E., Aitken L., Muirhead K., Ainge J., Conway S., Gunn-Moore F.J. Models for mitochondrial involvement in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochem Soc. Trans. 2011;39:868–873. doi: 10.1042/BST0390868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benek O., Aitken L., Hroch L., Kuca K., Gunn-Moore F., Musilek K. A Direct interaction between mitochondrial proteins and amyloid-β peptide and its significance for the progression and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015;22:1056–1085. doi: 10.2174/0929867322666150114163051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao J., Irwin R.W., Zhao L., Nilsen J., Hamilton R.T., Brinton R.D. Mitochondrial bioenergetic deficit precedes Alzheimer’s pathology in female mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:14670–14675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903563106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lustbader J.W., Cirilli M., Lin C., Xu H.W., Takuma K., Wang N., Caspersen C., Chen X., Pollak S., Chaney M., et al. ABAD Directly Links Aß to Mitochondrial Toxicity in Alzheimer’s Disease. Science. 2004;304:448–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1091230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lauretti E., Li J.-G., Di Meco A., Praticò D. Glucose deficit triggers tau pathology and synaptic dysfunction in a tauopathy mouse model. Transl. Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1020. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim Y.-A., Grimm A., Giese M., Mensah-Nyagan A.G., Villafranca J.E., Ittner L.M., Eckert A., Götz J. Inhibition of the Mitochondrial Enzyme ABAD Restores the Amyloid-β-Mediated Deregulation of Estradiol. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valasani K.R., Sun Q., Hu G., Li J., Du F., Guo Y., Carlson E.A., Gan X., Yan S.S. Identification of Human ABAD Inhibitors for Rescuing Aβ-Mediated Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2014;11:128–136. doi: 10.2174/1567205011666140130150108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hroch L., Benek O., Guest P., Aitken L., Soukup O., Janockova J., Musil K., Dohnal V., Dolezal R., Kuca K., et al. Design, synthesis and in vitro evaluation of benzothiazole-based ureas as potential ABAD/17β-HSD10 modulators for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;26:3675–3678. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.05.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hroch L., Guest P., Benek O., Soukupb O., Janockovab J., Dolezal R., Kuca K., Aitken L., Smith T.K., Gunn-Moore F., et al. Synthesis and evaluation of frentizole-based indolyl thiourea analogues as MAO/ABAD inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2017;25:1143–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benek O., Hroch L., Aitken L., Dolezal R., Guest P., Benkova M., Soukup O., Musil K., Hughes R., Kuca K., et al. 6-benzothiazolyl ureas, thioureas and guanidines are potent inhibitors of ABAD/17β-HSD10 and potential drugs for Alzheimer’s disease treatment: Design, synthesis and in vitro evaluation. Med. Chem. 2017;13:345–358. doi: 10.2174/1573406413666170109142725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao X., Chen Q., Zhu X., Wang Y. ABAD/17β-HSD10 reduction contributes to the protective mechanism of huperzine a on the cerebral mitochondrial function in APP/PS1 mice. Neurobiol. Aging. 2019;81:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du Yan S., Fu J., Soto C., Chen X., Zhu H., Al-Mohanna F., Collison K., Zhu A., Stern E., Saido T., et al. An intracellular protein that binds amyloid-β peptide and mediates neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1997;389:689–695. doi: 10.1038/39522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao J., Taylor M., Davey F., Ren Y., Aiton J., Coote P., Fang F., Chen J.X., Yan S.D., Gunn-Moore F.J. Interaction of amyloid binding alcohol dehydrogenase/Abeta mediates up-regulation of peroxiredoxin II in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients and a transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2007;35:377–382. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oppermann U.C.T., Salim S., Tjernberg L.O., Terenius L., Jörnvall H. Binding of amyloid β-peptide to mitochondrial hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (ERAB): Regulation of an SDR enzyme activity with implications for apoptosis in Alzheimer’s disease. FEBS Lett. 1999;451:238–242. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00586-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du Yan S., Shi Y., Zhu A., Fu J., Zhu H., Zhu Y., Gibson L., Stern E., Collison K., Al-Mohanna F., et al. Role of ERAB/l-3-Hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A Dehydrogenase Type II Activity in Aβ-induced Cytotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:2145–2156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valasani K.R., Hu G., Chaney F.O., Yan W.S.S. Structure Based Design and Synthesis of Benzothiazole Phosphonate Analogues with Inhibitors of Human ABAD-Aβ for Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2013;81:238–249. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan J.G., Tang R.Y., Zhong P., Li J.H. Copper-catalysed tandem reactions of 2-halobenzenamines with isothiocyanates under ligand- and base-free conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:649–652. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aitken L., Baillie G., Pannifer A., Morrison A., Jones P., Smith T., McElroy S., Gunn-Moore F. In Vitro Assay Development and HTS of Small Molecule Human ABAD/17β-HSD10 Inhibitors as Therapeutics in Alzheimer’s Disease. SLAS Discov. 2017;22:676–685. doi: 10.1177/2472555217697964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kissinger C.R., Rejto P.A., Pelletier L.A., Thomson J.A., Showalter R.E., Abreo M.A., Agree C.S., Margosiak S., Meng J.J., Aust R.M., et al. Crystal Structure of Human ABAD/HSD10 with a Bound Inhibitor: Implications for Design of Alzheimer’s Disease Therapeutics. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;342:943–952. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muirhead K.E.A., Froemming M., Li X., Musilek K., Conway S.J., Sames D., Gunn-Moore F.J. (−)-CHANA, a Fluorogenic Probe for Detecting Amyloid Binding Alcohol Dehydrogenase HSD10 Activity in Living Cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010;5:1105–1114. doi: 10.1021/cb100199m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aitken L., Quinn S.D., Perez Gonzalez D.C., Samuel I.D.W., Penedo-Esteiro J.C., Gunn-Moore F.J. Morphology-specific inhibition of β-amyloid aggregates by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 10. ChemBioChem. 2016;17:1029–1037. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201600081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aitken L., Benek O., McKelvie B., Hughes R., Hroch L., Major L.L., Kuca K., Smith T.K., Musilek K., Gunn-Moore F.J. Data Underpinning: Novel Benzothiazole-Based Ureas as 17β-HSD10 Inhibitors, a Potential Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment. Dataset. University of St. Andrews, Research Portal; St. Andrews, Scotland: 2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.