Abstract

Gut microbiota have important functions in the body, and imbalances in the composition and diversity of those microbiota can cause several diseases. The host fosters favorable microbiota by releasing specific factors, such as microRNAs, and nonspecific factors, such as antimicrobial peptides, mucus and immunoglobulin A that encourage the growth of specific types of bacteria and inhibit the growth of others. Diet, antibiotics, and age can change gut microbiota, and many studies have shown the relationship between disorders of the microbiota and several diseases and reported some ways to modulate that balance. In this review, we highlight how the host shapes its gut microbiota via specific and nonspecific factors, how environmental and nutritional factors affect it, and how to modulate it using prebiotics, probiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation.

Keywords: Antibiotics, miRNA, Diet, Probiotics, Gut microbiota, Prebiotics, AMPs, FMT

Introduction

The human intestines are inhabited by complex microbial communities called gut microbiota, and the number of these microbes has been estimated to exceed 1014. Studies on humans and animal models have reported the role of gut microbiota in human health (De Palma et al., 2017; Wiley et al., 2017). The gut microbiota have many important functions in body, including supporting resistance to pathogens, affecting the immune system (Chung et al., 2012; Arpaia et al., 2013), playing a role in digestion and metabolism (Rothschild et al., 2018), controlling epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation (Sekirov et al., 2010), modifying insulin resistance and affecting its secretion (Kelly et al., 2015), and affecting the behavioral and neurological functions of the host (Buffington et al., 2016; Wahlström et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2019).

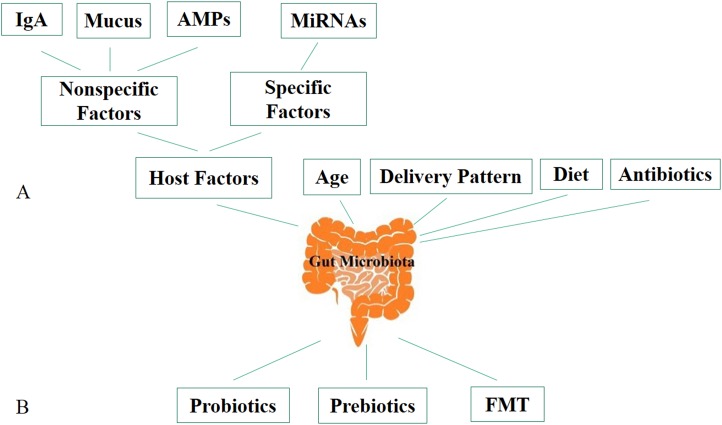

Studies have shown that transplantation of gut microbiota of the conventional zebrafish to germ-free mice and conventional mouse gut to germ-free zebrafish resulted the gut microbiota of both receivers after transplantation resembled the microbiota of their conventional species. It indicates that there are specific mechanisms used by the host to shape its own gastrointestinal microbiota and maintain its homeostasis (Liu et al., 2016; Rawls et al., 2006). There are several factors that can change gut microbiota, including host genetic, diet, age (Odamaki et al., 2016; Jandhyala et al., 2015), mode of birth (Nagpal et al., 2017; Wen & Duffy, 2017) and antibiotics (Goodrich et al., 2014; Ley et al., 2005; Turnbaugh et al., 2009) (Fig. 1A). The perturbation of the gut microbiota population associated with several human diseases that include inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) (Bien, Palagani & Bozko, 2013; Takahashi et al., 2016; Nishino et al., 2018), obesity and diabetes (Karlsson et al., 2013), allergy (Vernocchi, Del Chierico & Putignani, 2016; Bunyavanich et al., 2016), autoimmune diseases (Chu et al., 2017), cardiovascular disease (Cui et al., 2017b; Jie et al., 2017; Trøseid, 2017), hypertension (Li et al., 2017), and modulating its composition and diversity is considered a promising treatment for these diseases. There are many ways to modulate gut microbiota, including probiotics, prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) (Fig. 1B), which can cause favorable changes in the structure and functions of the gut microbiota and restore it temporarily or permanently. The present review discusses the mechanisms the host uses to shape its gut microbiota and the factors that can modulate these microbes and to improve understanding of the role of FMT, probiotics, and prebiotics in gut community modulation.

Figure 1. Factors affecting gut microbiota and ways to modulate it.

(A) Factors affecting gut microbiota. (B) Ways to modulate gut microbiota. AMPs, antimicrobial peptides; IgA, immunoglobulin A; miRNA, microRNA; FMT, fecal microbiota transplantation.

Survey methodology

Literature searching aimed at collecting any published data about cultivation, alteration, and restoration of gut microbiota. We searched literature relevant to the topic of the articles using PubMed and Google Scholar. Key words such as gut microbiota, factors shape gut microbiota, microRNA (miRNA), FMT, probiotics, antibiotic, prebiotics, and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) were used to search. Then, screened articles were used as references for this review.

Host factors that shape the human microbiota

Hosts use specific and nonspecific factors to cultivate their own gut microbiota. The host favors the type of microbes that can colonize its intestines and removes other microbes from the body.

Nonspecific host factors

The host chooses its own gut microbiota by producing several molecular signals that control the structure of the surfaces colonized by microbiota and so influences its composition. These molecules are produced by the intestinal epithelial cells (IEC) and include mucus, AMPs, and immunoglobulin A (IgA), which can encourage the growth of some microbial species and inhibit that of others. In the large intestine, mucus plays an important role in keeping the microbes far from IEC, it is constituted of two layers: the inner layer does not contain any microorganisms whereas the outer layer contains soluble mucins, which are decorated by O-glycans, provide a nutrient source and binding site for gut microbiota (Podolsky et al., 1993; Artis et al., 2004). Mucus and mucin O-glycans play a key role in shaping the gut microbiota and selecting the most appropriate microbial species for host health (Arpaia et al., 2013; Zarepour et al., 2013). Utilisation of mucin by gut microbiota is depending on glycoside hydrolases and polysaccharide lyases which are encoded by their genes (Tailford et al., 2015). Some species of gut microbiota have capacity to degrade complex carbohydrates such as Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, whose genome contains 260 glycoside hydrolases (Cockburn & Koropatkin, 2016). While there is not enough mucus in the small intestine, AMPs play an important role in shaping gut microbiota. The gut microbiota by its structural components and metabolites induce AMP production by Paneth cell through a mechanism mediated by pattern recognition receptor (PRR) (Hooper, 2009; Salzman, Underwood & Bevins, 2007), whereas PRRs are activated by different microbial components, such as flagella and lipopolysaccharide, in a system called microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMP). PRR-MAMP plays important roles in promoting the function of the mucus barrier and inducing the production of IgA, mucin glycoproteins, and AMPs (Takeuchi & Akira, 2010; Carvalho et al., 2012), and concentration of the AMPs are maximal in small intestinal crypts because of Paneth cells reside at this location. AMPs are secreted by IEC as the body's first line of defense against invaders and these proteins have a broad effect that directly kills bacteria, virus, yeast, fungi, and even cancer cells. These proteins include defensins, cathelicidins, Reg family proteins, and ribonucleases (Cash et al., 2006). It has been proven that all dominant species of gut microbiota can resist high concentrations of AMPs, and AMPs may play an important role when the host distinguishes commensal from pathogenic bacteria (Cullen et al., 2015). Bacteroides, the most abundant Gram-negative genus among the gut microbiota, had resistance to AMPs (Cullen et al., 2015). After Bacteroides strains lost their ability to produce dephosphorylate lipid A (Raetz & Whitfield, 2002), the sensitivity to AMPs is increased, suggesting that dephosphorylate lipid A gives the Bacteroides their ability to resist the high concentrations of AMPs in the intestine.

Antibacterial lectins, which can form hexameric pores in Gram-positive bacterial membranes and prevent them from reaching the intestinal mucus layer (Cash et al., 2006; Mukherjee et al., 2014), are important antibacterial factors that contribute to shaping gut microbiota. On the basis of these secreting factors, IEC promote growth of some bacterial species and inhibit that of others so the host control the shape and structure of its gut microbiota by modulating these secretors.

In addition, there are plasma cells in the intestinal mucosa that produce secretory immunoglobulin A (SIgA) that can cover the bacteria and control its numbers locally (Macpherson & Uhr, 2004). Further, SIgA plays a role in bacterial biofilm formation by binding to SIgA receptors on bacteria (Randal Bollinger et al., 2003). The presence of gut microbiota was possibly a condition to activate dendritic cells, which induce plasma cells to produce IgA (Massacand et al., 2008). The absence of IgA can lead to increases in segmental filamentous bacteria, occurs IgA-deficient mice, suggesting that the induced secretory IgA production is a form of competition between different types of gut microbiota (Suzuki et al., 2004).

Specific host factors

The other host factor that can be used to assess the shape and structure of gut microbiota is miRNAs, which are small non-coding RNAs that are 18–23 nucleotides in length. MiRNAs are generated in the nucleus and then transported to the cytoplasm to effect gene silencing by hybridizing with the 3′ untranslated region of the target gene and promote mRNA degradation or inhibit translation (Djuranovic, Nahvi & Green, 2012). One miRNA can target different mRNAs (Maudet, Mano & Eulalio, 2014; Kalla et al., 2014), and it has been proven that miRNAs exist outside the cells and circulate in bodily fluids (Weber et al., 2010).

Ahmed et al. (2009) and Link et al. (2012) measured RNA in human stool and demonstrated that miRNAs as potential markers of intestinal malignancy, whereas Liu et al. (2016) investigated the gut miRNAs in intestinal contents and feces. All three works demonstrated their ability to affect the composition of the gut microbiota composition. The IEC and Hopx-positive cells are main sources of fecal miRNA. Ahmed et al. (2009) and Link et al. (2012) also investigated the relationship between the deficiency of IEC-miRNA and gut dysbiosis and studied why wild-type fecal transplantation can restore the gut microbiota, indicating that miRNAs were able to regulate the gut microbiome. Several miRNAs can then enter the gut bacterial cells and regulate their growth and gene expression. Liu et al. (2016) found that hsa miRNA-515-5P can stimulate Fusobacterium nucleatum growth and that hsa miRNA-1226-5p stimulates E. coli growth via culturing the strains with synthesized mimics miRNA in vitro and affected E. coli in vivo also when given orally to mice. In this way, miRNA was found to have specific effects on gut bacterial growth.

In addition, Liu et al. (2016) demonstrated that miRNA can enter the bacterial cell and settle near bacteria DNA in the nucleus, and then, they studied the effect of synthetic miRNAs on bacterial gene expression and growth. The presence of gut microbiota has an effect on miRNA expression in the intestine. Dalmasso et al. (2011) found that nine miRNAs in the colon and ileum had different levels of expression in the germ-free mice which are colonized with pathogen-free mice microbiota. Xue et al. (2011) found that microbiota can affect expression of miR-10a, which targets interleukin-12/ interleukin-23p40B, which is itself responsible for innate immune response of the host toward the gut microbiota, suggesting that the gut microbiota can control host innate immune responses by regulating of miRNA expression.

The gut microbiota can be shaped by administration of fecal miRNAs. The microbiota profile of the recipient becomes similar to that of the donor after transplantation of fecal RNA, as shown in the case of transfer from healthy mouse donors to IEC-deficient mice (Liu et al., 2016). This indicates an important potential of application, in the future, diseases related to changes in gut microbiota may be treated using synthetic specific miRNA.

Factors influencing homeostasis of microbiota

The gut microbiota is established early in life stage but can later be altered by various factors that affect its development and diversity.

Age and delivery pattern

Microbial intestinal colonization process begins in utero by microbiota in the amniotic fluid and placenta (Collado et al., 2016). Studies have reported that there are bacteria and bacterial products, such as DNA, in meconium (Nagpal et al., 2017; Wampach et al., 2017; Jiménez et al., 2008), amniotic fluid (Collado et al., 2016; DiGiulio et al., 2008), and the placenta (Collado et al., 2016; Friedrich, 2013). Studies on the pregnant mice have demonstrated that oral administration of labeled Enterococcus fecium resulted staring isolated it from the newborn stool samples (Jiménez et al., 2008), this result agree with the evidence maternal microbes can be transferred to the amniotic fluid (Collado et al., 2016; Jiménez et al., 2008) and the placenta (Goldenberg, Hauth & Andrews, 2000). After birth, the mode of delivery affect the early-life development of the gut microbiota. Newborns delivered vaginally have primary gut microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus and Prevotella derived from the mother's vaginal microbiota, while those born via cesarean delivery derive their gut microbiota from the skin, leading to dominance of Streptococcus, Corynebacterium, and Propionibacterium (Dominguez-Bello et al., 2010; Mackie, Sghir & Gaskins, 1999). These primary microbiota evolve over time to become more diverse and relatively stable. At the age 3 years, they become similar to an adult's gut microbiota (Yatsunenko et al., 2012).

Diet

After birth, the first effect on the gut microbiota is the infant diet (breast or formula milk). The composition of the milk affect on shaping the early gut microbiota (Guaraldi & Salvatori, 2012; Groer et al., 2014). In breast feeding infants, the species that dominate the gut microbiota are Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium; breast milk contains oligosaccharides that can be broken down easily by these species, resulting in an increase in short-chain fatty acids, which directs the immune system to increase the expression of immunoglobulin G (Ouwehand, Isolauri & Salminen, 2002). Whilst in infants raised on formula, the dominant species are Enterococcus, Enterbacteria, Bacteroides, Clostiridia, and Streptococcus (Yoshioka, Iseki & Fujita, 1983; Stark, Lee & Parsonage, 1982). The primary microbiota acquired during infancy may play an important role in initial immunity during the growth of babies, for this reason, the composition of primary microbiota during this period is very important to protect babies from diseases related to poor immunity (Groer et al., 2014; Sherman, Zaghouani & Niklas, 2014). Several studies have compared the gut microbiota population and mucosal immune response between breast and formula feeding and found that the breast feeding caused more stable population and good mucosal immune response (Grönlund et al., 2000; Bezirtzoglou, Tsiotsias & Welling, 2011).

Interestingly, human milk microbiota play important roles in immunological activities such as increasing the number of plasma cells in the intestinal environment of newborns that produce IgA (Gross, 2007), stimulation of cytotoxic Th1 cell (M'Rabet et al., 2008), motivation specific cytokines that create a balanced microenvironment (Walker & Iyengar, 2014), development of local and systemic immune system (Houghteling & Walker, 2015), and some Lactobacillus strains promote the production of Th1, cytokines and TNF-α, regulate T cell, and stimulate NK cells, CD4+ T-cells and CD8+ T-cells.

After infancy, the gut microbiota continues its development, and the diet remains key to defining the shape, structure, and diversity of the gut microbiota. Vegetarian diets have been found to be associated with healthy, diverse gut microbiota characterized by the domination of species that can metabolize insoluble carbohydrates, such as Ruminococcus, Roseburia, and Eubacterium (Walker et al., 2011), while a non-vegetarian diet (Western diet) has been associated with a decreasing number of Firmicutes and an increase in Bacteroides (David et al., 2014). Diet can cause important changes even over short periods (David et al., 2014). After consumption of a Western diet, the gut microbiota ferment amino acids, which result in production of short-chain fatty acids as energy sources, and harmful compounds can be produced (Windey, De Preter & Verbeke, 2012). The vegetarian diet inhibits this, and fosters carbohydrate fermentation as the main function of microbiota (Tang et al., 2013; Clarke et al., 2014).

Antibiotics

The use of antibiotics is a two-edged weapon: it destroys both pathological and beneficial microbes indiscriminately, allowing loss of gut microbiota or the so-called dysbiosis and growth of unwanted microbes (Klingensmith & Coopersmith, 2016). Studies on experimental mice have demonstrated the antibiotics administration affected secondary bile acid and serotonin metabolism in the colon and resulting in delayed intestinal motility by causing microbiota depletion (Ge et al., 2017). Antibiotics disrupt the competitive exclusion machinery, a basic property by which microbiota eliminate pathological microbes (Hehemann et al., 2010). This disruption promotes growth of other pathogens, such as Clostridium difficile (Ramnani et al., 2012). Studies have reported that clindamycin (Jernberg et al., 2007), clarithromycin and metronidazole (Jakobsson et al., 2010) and ciproflaxin (Dethlefsen & Relman, 2010) affect the microbiota structure for a long time.

Clindamycin causes changes in microbiota that last 2 years with no recovery in the diversity of Bacteroides (Jernberg et al., 2007). Similarly, the use of clarithromycin in Helicobacter pylori treatment causes a decrease in the population of Actinobacteria (Jakobsson et al., 2010), while ciprofloxacin has been shown to cause a decrease in that of Ruminococcus (Dethlefsen et al., 2008). Vancomycin, which is considered the best treatment option for C. difficile infection (CDI), but, like other antibiotics, it causes changes in gut microbiota that lead to recurrent C. difficile infection (rCDI) (Zar et al., 2007) or encourage growth of pathological strains of E. coli (Lewis et al., 2015). Vancomycin treatment also causes depletion of most gut microbiota, such as Bacteroidetes, and it is associated with increases in Proteobacteria species (Isaac et al., 2016), and decreases in Bacteroidetes, Fuminococcus, and Faecalibacterium (Vrieze et al., 2014). The specific effects of antibiotic administration on the gut microbiota and the recovery time are depending on individual, like effect of the changes in the gut microbiota before treatment (Dethlefsen & Relman, 2010; Jernberg et al., 2007).

In many countries, the antibiotics are used for agriculture particularly intensive farming of poultry and beef, and low doses of antibiotics are routinely given to livestock to increase their growth and weight (Blaser, 2016). Several studies on human and rodent have indicated to an obesogenic impact of antibiotics in humans even in low doses found in food (Blaser, 2016). Pesticides and other chemicals are commonly sprayed on foods and currently, the evidence is lacking for their harm on gut health and the effects of organic food (Lee et al., 2017).

Modulation of gut microbiota

Modulation of the gut microbiota is clinically important to treat all diseases related to imbalances in gut microbiota, and methods for modulating that balance include probiotics, prebiotics, and FMT.

Probiotics

Probiotics are living microorganisms that, when taken in appropriate doses, protect human health (Kristensen et al., 2016). The most commonly used probiotic species are Lactobacillus, Bifidobacteria and yeasts, such as Saccharomyces boulardii (Rokka & Rantamäki, 2010; Dinleyici et al., 2012). The proposed mechanisms by which probiotics improve health include promotion of favorable types of gut microbes. In a study by Stratiki et al. (2007), the administration of a Bifidobacter-supplemented infant formula decreased the intestinal permeability of preterm infants and increased the abundance of fecal Bifidobacterium. Probiotics compete with harmful species for adhesion sites. For example, E. coli Nissle can move and attack pathological microbes and prevent their adhesion (Servin, 2004). Some probiotics can produce antimicrobial compounds like Lactobacillus reuteri, which produce reuterin that kills harmful microbes directly (Cleusix et al., 2007), and induces immune responses in the host. Bifidobacterium can enhance the function of mucous intestinal barrier, increase serum IgA, and reduce inflammation of the intestine (Mohan et al., 2008). Bifidobacterium has also been reported to reduce the number of harmful bacteria in stool samples (Mohan et al., 2006). Several systematic reviews analyzed the role of probiotics on clinical outcomes. The analysis showed substantial evidence for beneficial effects of probiotic supplementation in chronic periodontitis (Ikram et al., 2018), urinary tract infections (Schwenger, Tejani & Loewen, 2015), necrotizing enterocolitis (Rees et al., 2017), and reduction of total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (Wu et al., 2017). In type 2 diabetes patients, probiotic administration reduced fasting blood glucose and HbA1 (Akbari & Hendijani, 2016) and decreased cardiovascular risk (Hendijani & Akbari, 2018). A meta-analysis showed that probiotic therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes significantly decreased insulin concentration and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance score (Zhang, Wu & Fei, 2016), which was an important index to assess insulin resistance in several diseases, such as prediabetes, diabetes mellitus type 2 and metabolic syndrome. Xie et al. (2017) reported the efficiency of probiotics in vulvovaginal candidiasis in non-pregnant women indicated that probiotics increased the rate of short term clinical cure and mycological cure and decreased relapse rate at 1 month.

The utilization of mucins by gut microbiota under dietary fiber deficiency causes the erosion of the colonic mucus barrier (Desai et al., 2016) and studies on experimental mice demonstrated that administration of Akkermansia muciniphila, mucin degrade, lead to restoration of the gut barrier (Everard et al., 2013; Li et al., 2016a). A. muciniphila has probiotic properties and can prevent or treat several metabolic disorders (Zhou, 2017). Recently, studies on chow diet-fed mice showed that A. muciniphila supplementation had ability to reduce metabolic inflammation that lead to alleviating body weight gain and reduce fat mass (Zhao et al., 2017). Moreover, A. muciniphila acts as an energy sensor, its abundance increases with decreasing calories and decreases with extra energy which enables the energy uptake when available (Chevalier et al., 2015).

Many probiotic products use the microencapsulation technique to protect bacteria from environmental factors, and their effects vary depending on the type and number of bacteria (Rokka & Rantamäki, 2010). Generally, the probiotic products contain at least 106–107 CFU. The different doses of probiotics in treating antibiotic-induced diarrhea were compared, indicating that high doses of probiotics were more effective (Gao et al., 2010). This is because a large number of the probiotic organisms perish in the stomach before reaching the colon (Borody & Campbell, 2011).

Currently, researchers do not agree on the efficacy of probiotics in intestinal diseases, largely because studies have used different doses and types of probiotics (Ringel & Ringel-Kulka, 2011; Hamilton et al., 2012; Borody et al., 2004). For example, some studies have shown that probiotics mitigate traveler's diarrhea while others have found them to have no clear benefit (Ritchie & Romanuk, 2012; Huebner & Surawicz, 2006).

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are defined as selective fermentation components that cause specific changes in the activity or structure of gut microbiota and so benefit to the host (Tabibian, Talwalkar & Lindor, 2013; Rossen et al., 2014). Prebiotics usually consist of non-digestible carbohydrates, oligosaccharides, or short polysaccharides like inulin, oligofructose, galactofructose, galacto-oligosaccharides, and xylo-oligosaccharides. Prebiotics must be able to resist gastric acids but yet be degraded by digestive enzymes and become absorbed by the upper tract of the digestive system, fermentation by gut microbiota and inciting the growth or activating useful species of the gut microbiota (Quraishi et al., 2014). Prebiotics affect the microbiota species already present in the colon (Slavin, 2013). The main target species of prebiotics are Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria (Tabibian, Talwalkar & Lindor, 2013) and the effects of prebiotics include increasing production of short-chain fatty acids and decreasing pH (De Vrese & Marteau, 2007).

Dietary fiber consumption is important to maintain intact mucosal barrier function in the gut (Ray, 2018). Recently, several studies demonstrated the effect of prebiotic fibers on the modulation of the gut microbiota (Dahiya et al., 2017; Gibson et al., 2017; Holscher, 2017; Umu, Rudi & Diep, 2017; Ling et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2016). Studies showed that administration of inulin can prevent the harmful effects of high fat diets on penetrability of the mucus layer and metabolic functions (Zhou, 2017; Schroeder et al., 2018). Evidence indicates that the low fiber Western diet causes weakening in the colonic mucus barrier, that leads to microbiota crept, which results in pathogen susceptibility (Desai et al., 2016) and inflammation (Earle et al., 2015), providing a relationship between the Western diet with chronic diseases. Moreover, the mixture of galacto-oligosaccharides and fructo-oligosaccharides have ability to increasing Bifidobacteria and decreasing Clostridium in the gut whilst galacto-oligosaccharides alone increase Lactobacillus (Vandenplas, Zakharova & Dmitrieva, 2015). Additional studies showed that arabino-xylooligosaccharides and inulin alter the intestinal barrier function and immune response (Van den Abbeele et al., 2018).

FMT

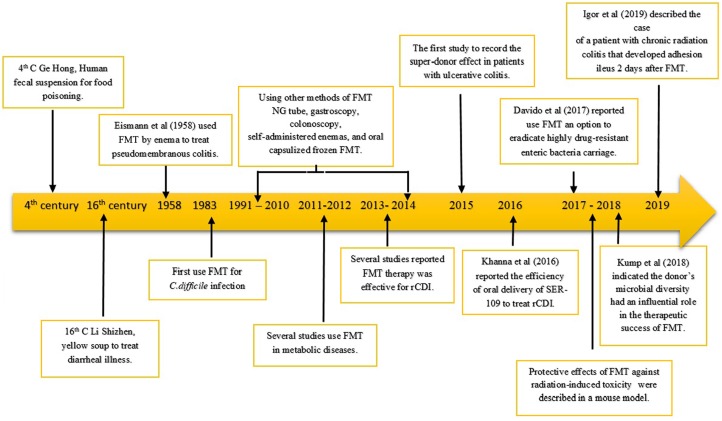

Fecal microbiota transplantation is the process of transplantation of fecal bacteria from healthy donors to patients with intestinal diseases or changes or dysbiosis in natural gut microbiota to restore the community and function of gut microbiota (Khoruts & Sadowsky, 2016). The first use of FMT took place in China during the 4th century (Fig. 2). Ge Hong reportedly used faeces to treat cases of food poisoning and diarrhea (Zhang et al., 2012). In the 16th century, Li Shizhen reportedly used fecal matter, later called yellow soup, to treat fever, pain, and several symptoms of intestinal disorders, such as diarrhea, constipation, and vomiting. In modern medicine, Eiseman first reported that FMT has successfully treated many patients with pseudomembranous colitis by enema (Eiseman et al., 1958). In the succeeding years, the use of FMT focused on the treatment of CDI and rCDI with a cure rate of 87–90% (Kassam et al., 2012; Van Nood et al., 2013; Cammarota, Ianiro & Gasbarrini, 2014; Rossen et al., 2015). Currently, because of insufficient genetic information that explains the contrast in recipient responses, investigators have studied the donor-dependent effect and suggested the existence of so-called super-donors. In 2015, Moayyedi and colleagues described the super-donor effected on the efficacy of FMT for inducing clinical remission in patients with ulcerative colitis (Moayyedi et al., 2015). Whilst Kump et al. (2018) and Vermeire et al. (2015) demonstrated that the donor's microbial diversity has an influential role in the therapeutics success of FMT (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Timeline: FMT development studies.

Yellow arrow showed time-base, and FMT development studies were described in text box.

Fecal microbiota transplantation has a high capacity for treating different diseases, including IBD (Ianiro et al., 2014; Anderson, Edney & Whelan, 2012; Goyal et al., 2018; Kump et al., 2018), irritable bowel syndrome (Pinn, Aroniadis & Brandt, 2014; Gibson & Roberfroid, 1995; Borody et al., 2004; Holvoet et al., 2017; Mizuno et al., 2017; Aroniadis et al., 2018; Halkjær et al., 2018; Johnsen et al., 2018) constipation (Tian et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2017), metabolic diseases (Tremaroli & Bäckhed, 2012; Tilg & Kaser, 2011; Vrieze et al., 2012), neuropsychiatric conditions (Hornig, 2013; He et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2017; Makkawi, Camara-Lemarroy & Metz, 2018), autoimmune diseases (Luckey et al., 2013; Borody et al., 2011), allergic disorders (Russell & Finlay, 2012), blood (Kakihana et al., 2016; Spindelboeck et al., 2017; DeFilipp et al., 2018), colon cancer (Wong et al., 2017), anti-tumor immunity (Sivan et al., 2015) and chronic fatigue syndrome (Borody, Nowak & Finlayson, 2012). Some studies using FMT to treat CDI and IBD are summarized in Table 1. In the most recent studies, Davido et al. (2017) reported to eradicate highly drug-resistant enteric bacteria using FMT. While Cui et al. (2017a) and Gerassy-Vainberg et al. (2018) reported the protective effects of FMT against radiation-induced toxicity in a mouse model. Recently, a non-desirable side effect of the FMT was reported. Harsch & Konturek (2019) reported that a patient with chronic radiation colitis developed adhesion ileus 2 days after FMT (Fig. 2).

Table 1. Summary of studies using FMT to treat CDI and IBD.

| Administration method | Resolution rate (%) | n | Diagnosis | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colonoscopy | 100 | 1 | CDI | Persky & Brandt, 2000 |

| Nasogastric | 83 | 18 | CDI | Aas, Gessert & Bakken, 2003 |

| Colonoscopy, enema | 93.7 | 16 | CDI | Wettstein et al., 2007 |

| Rectal catheter | 97.7 | 45 | CDI | Louie et al., 2008 |

| Colonoscopy | 100 | 1 | CDI | Hellemans, Naegels & Holvoet, 2009 |

| Colonoscopy | 92 | 37 | CDI | Arkkila et al., 2010 |

| Self-administered enema | 100 | 7 | CDI | Silverman, Davis & Pillai, 2010 |

| Colonoscopy | 100 | 13 | CDI | Wilcox, 2011 |

| Colonoscopy | 94 | 70 | CDI | Mattila et al., 2012 |

| Colonoscopy | 86 | 43 | CDI | Hamilton et al., 2012 |

| Nasogastric | 80 | 74 | CDI | Rubin et al., 2013 |

| Nasoduodenal tube | 81 | 17 | CDI | Van Nood et al., 2013 |

| Enema | 33 | 10 | IBD | Kunde et al., 2013 |

| Colonoscopy | 20 | 5 | IBD | Damman et al., 2014 |

| Oral capsule | 70 | 20 | CDI | Youngster et al., 2014b |

| Colonoscopy | 90 | 20 | CDI | Cammarota et al., 2015 |

| Various | 90–97.8 | 1,029 | CDI | Rossen et al., 2015 |

| Nasogastric infusion | 86.6 | 30 | IBD | Cui et al., 2015 |

| Nasogastric infusion | 78 | 9 | IBD | Suskind et al., 2015 |

| Enema | 30 | 81 | IBD | Paramsothy et al., 2016 |

| Colonoscopy | 90.9 | 46 | CDI | Kelly et al., 2016 |

| Colonoscopy | 70 | 30 | IBD | Uygun et al., 2017 |

Note:

CDI, Clostridium difficile infection; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; n, number of patients.

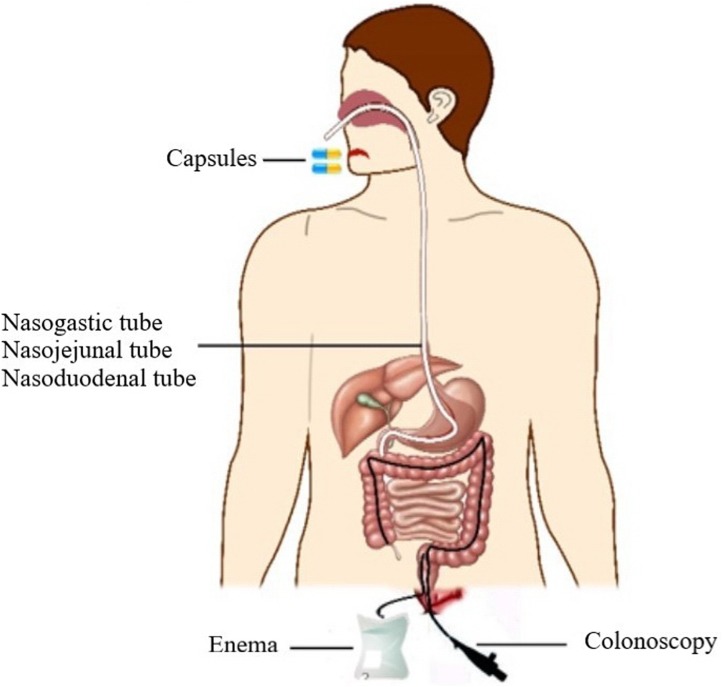

Transplantation pathway of FMT

Several pathways (Fig. 3), such as colonoscopy, and enema, have shown pronounced efficiency in FMT (Paterson, Iredell & Whitby, 1994; Borody et al., 2003; Silverman, Davis & Pillai, 2010; Kassam et al., 2012). More recently, enteric-coated capsules and capsules containing freeze dried feces or bacteria were also used and the high efficiency of FMT was confirmed (Brandt, Borody & Campbell, 2011; Tian et al., 2015).

Figure 3. The pathways of FMT.

Several pathways of FMT are shown in the schematic diagram.

Enema is still the easiest, cheapest way of effecting FMT, posing little risk to patients. Recently, colonoscopy has become an attractive option because it can deliver a large volume of fecal matter along the entire colon. However, it is less safe than rectal enemas, posing a greater risk of perforation (Kassam et al., 2013). Colonoscopy is also more expensive and time-consuming than enema.

Many recent studies have reported that the stool can be delivered via oral encapsulated FMT or stool enemas (Youngster et al., 2014a; Hirsch et al., 2015). The efficacy of the first dose was about 52–70%, which is lower than that of other methods of administration, such as colonoscopy; but after examination of several rounds of treatment are administered to the patient, the result were similar to those of colonoscopy (Youngster et al., 2014a; Hirsch et al., 2015).

SER-109, a microbiome therapeutic, is a new kind of therapy composite of commensal bacterial spores. Studies have shown that SER-109 not only relieves dysbiosis but also leads to increases in beneficial bacteria not contained in the product when treating rCDI in patients with a history of multiple relapses (Khanna et al., 2016). Several studies have also shown that spore-forming organisms isolated from stool sample, could compete metabolically with C. difficile for essential nutrients (Buffie et al., 2015; Theriot et al., 2014), and this could prevent CDI. Whilst Khanna et al. (2016) reported the efficiency of oral delivery of SER-109 to treat rCDI.

Regardless of the route of FMT, there is enough evidence supporting the conclusion that FMT is a highly efficient, and therapeutic option for several intestinal diseases, characterized by ability to restore the compositions and functions of gut microbiota which are similar to gut microbiota of recipients (Khoruts et al., 2010; Li et al., 2016b). Using next-generation sequencing techniques, changes in gut microbiota species could been identified both before and after FMT. An increasing studies have shown that FMT can lead to permanent participation of new species of gut microbiota, such as that found in healthy donor feces, and FMT can increase the number of different bacteria present in recipient feces (Khoruts et al., 2010). Currently, the safety problem of FMT is a main obstacle to use it in more patients because of the complexity of feces microbial community.

Comparison of the efficiency of FMT and probiotics

Fecal microbiota transplantation has been found to outperform probiotics. Probiotic treatments contain specific bacteria and there is some doubt whether a sufficient quantity survives the stomach acids to reach the gut. To become established in the gut, the probiotic strains must outcompete the resident microbiota and occupy an ecological niche. Because the resident microbiota is inherently resistant to outside colonizer (Stecher & Hardt, 2008), the probiotic strains may fail to colonize and function in the gut. In addition, probiotics restore microbiota for an interim period (Tannock et al., 2000). FMT treatment delivered plenty of fecal bacteria to the colon and caused permanent restoration of microbiota (Grehan et al., 2010). Cammarota, Ianiro & Gasbarrini (2014) found that FMT administered to the lower intestinal track was more effective with rCDI than delivery to the upper tract. This may be because the growth of many kinds of fecal microbiota is affected by their administration route, for example, Bacteroidetes is sensitive to digestive acids, and the lower tract offers it a gentler environment (Burns, Heap & Minton, 2010). Probiotics rarely remain in the colon more than 14 days after the patient ceases taking them, while the effects of FMT on the gut microbiota can persist for 24 weeks (Pepin et al., 2005; Kelly & LaMont, 2008), indicating that FMT can cause pronounced changes in the gut microbiota (Mattila et al., 2012).

Future work

Several studies have investigated the role of gut microbiota in many diseases, including colorectal cancer, liver disease, and others (Dicksved et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009; Claud et al., 2013; Couturier-Maillard et al., 2013; Udayappan et al., 2014; Llopis et al., 2014; Buie, 2015). In the last few years, gut microbiota has been studied using metagenomic methodologies (Qin et al., 2010). Zheng et al. (2019) reported that the gut microbiome from patients with schizophrenia might be relevant to pathology of schizophrenia via altering neurochemistry and neurologic function. Currently, methods of modulating gut microbiota, including FMT, probiotics, and prebiotics, have come to be considered suitable treatment options for these diseases.

Future studies of probiotics and prebiotics should focus on the effect on different diseases with an agreement regarding the doses and the kind of bacteria used under each set of pathological conditions. High-throughput technologies allow researchers to easily find answers to many questions surrounding probiotics and prebiotics. This may help us to design new probiotics that more efficient with a higher quality and may lead to find new bacterial strains with probiotics properties.

Many studies have confirmed the ability of the gut microbiota to modify the expression of the host genes, and the impact of microbiota on miRNA expression was discovered using miRNA arrays, supporting the fact that gut microbiota affects the expression of hundreds of genes in the host (Dalmasso et al., 2011; Watson & Hall, 2013). More studies are needed to understand miRNA-microbiota interactions and determine which kinds of microbiota can modulate miRNA expression by combining high-throughput technologies.

Recently, FMT has been found to be a perfect treatment for rCDI cases that are nonresponsive to antibiotic therapy. Its high efficiency in many diseases has been confirmed, but FMT treatment suffers from a lack of information about the safety of long- and short-term administration. More and safer synthetic bacteria products (e.g., encapsulated formulations and full-spectrum stool-based products) and methods of transplantation need be developed to make FMT easier to use and more acceptable to patients. SER109, the mixture of bacterial spores, has shown high efficiency with rCDI diarrhea, and other similar products are being developed. The synthetic bacteria products may be able to replace traditional fecal treatment. In the future, various bacterial products may contain complicated mixtures of different bacterial species tailored using microbial ecological principles, and doctors may choose the suitable synthetic bacteria mixtures to a specific disease. FMT, probiotics, and other treatments meant to modulate a healthy microbiota may come to be considered suitable alternative treatments to antibiotics for diseases related to imbalances of gut microbiota.

Conclusions

Maintaining gut microbiota homeostasis is very important to the health. Several factors can directly or indirectly effect on the gut microbiota composition and species abundance. Other factors, different from that mentioned in this review, such as geographical location, maternal lifestyle (urban or rural), and fetal swallowing amniotic fluid (Thursby & Juge, 2017; Chong, Bloomfield & O'Sullivan, 2018; Nagpal et al., 2017), are also probable to contribute to gut microbiota development. The disorder of the gut microbiota is associated with several diseases and manipulating its composition and diversity is important element to control the development of these diseases. Based on data published, it can be concluded that manipulating the gut microbiota, either by prebiotics, probiotics or FMT, seem to be attractive options for the prevention and treatment of disease.

However, further studies need a full understanding on how manipulating gut microbiota can enhance health. In addition, studies for detecting the missing functions in the gut microbiota during disease will help to select the potential prebiotic, probiotic, or FMT that achieve the desired benefit.

Funding Statement

The study was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central universities (2572017DA07), and the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province, China (LC2016005). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Nihal Hasan conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Hongyi Yang conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

This is a review article; no data was collected.

References

- Aas, Gessert & Bakken (2003).Aas J, Gessert CE, Bakken JS. Recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis: case series involving 18 patients treated with donor stool administered via a nasogastric tube. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;36(5):580–585. doi: 10.1086/367657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed et al. (2009).Ahmed FE, Jeffries CD, Vos PW, Flake G, Nuovo GJ, Sinar DR, Naziri W, Marcuard SP. Diagnostic microRNA markers for screening sporadic human colon cancer and active ulcerative colitis in stool and tissue. Cancer Genomics-Proteomics. 2009;6(5):281–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbari & Hendijani (2016).Akbari V, Hendijani F. Effects of probiotic supplementation in patients with type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition Reviews. 2016;74(12):774–784. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuw039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Edney & Whelan (2012).Anderson JL, Edney RJ, Whelan K. Systematic review: faecal microbiota transplantation in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2012;36(6):503–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkkila et al. (2010).Arkkila PE, Uusitalo-Seppälä R, Lehtola L, Moilanen V, Ristikankare M, Mattila EJ. 29 Fecal bacteriotherapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(5):S-5. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(10)60023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroniadis et al. (2018).Aroniadis OC, Brandt LJ, Oneto C, Feuerstadt P, Sherman A, Wolkoff AW, Downs IA, Zanetti-Yabur A, Ramos Y, Cotto CL, Kassam Z, Elliott RJ, Rosenbaum R, Budree S, Sadovsky RG, Timberlake S, Swanson P, Kim M, Keller MJ. 742-A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fecal microbiota transplantation capsules (FMTC) for the treatment of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):S-154–S-155. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(18)30932-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arpaia et al. (2013).Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, Dikiy S, Van Der Veeken J, deRoos P, Liu H, Cross JR, Pfeffer K, Coffer PJ, Rudensky AY. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013;504(7480):451–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artis et al. (2004).Artis D, Wang ML, Keilbaugh SA, He W, Brenes M, Swain GP, Knight PA, Donaldson DD, Lazar MA, Miller HRP, Schad GA, Scott P, Wu GD. RELMβ/FIZZ2 is a goblet cell-specific immune-effector molecule in the gastrointestinal tract. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(37):13596–13600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404034101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezirtzoglou, Tsiotsias & Welling (2011).Bezirtzoglou E, Tsiotsias A, Welling GW. Microbiota profile in feces of breast-and formula-fed newborns by using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) Anaerobe. 2011;17(6):478–482. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bien, Palagani & Bozko (2013).Bien J, Palagani V, Bozko P. The intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and Clostridium difficile infection: is there a relationship with inflammatory bowel disease? Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology. 2013;6(1):53–68. doi: 10.1177/1756283X12454590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser (2016).Blaser MJ. Antibiotic use and its consequences for the normal microbiome. Science. 2016;352(6285):544–545. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borody & Campbell (2011).Borody TJ, Campbell J. Fecal microbiota transplantation: current status and future directions. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2011;5(6):653–655. doi: 10.1586/egh.11.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borody et al. (2011).Borody TJ, Campbell J, Torres M, Nowak A, Leis S. Reversal of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura [ITP] with fecal microbiota transplantation [FMT] American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;106:S352. [Google Scholar]

- Borody, Nowak & Finlayson (2012).Borody TJ, Nowak A, Finlayson S. The GI microbiome and its role in chronic fatigue syndrome: a summary of bacteriotherapy. Journal of the Australasian College of Nutritional and Environmental Medicine. 2012;31:3. [Google Scholar]

- Borody et al. (2003).Borody TJ, Warren EF, Leis S, Surace R, Ashman O. Treatment of ulcerative colitis using fecal bacteriotherapy. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2003;37(1):42–47. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200307000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borody et al. (2004).Borody TJ, Warren EF, Leis SM, Surace R, Ashman O, Siarakas S. Bacteriotherapy using fecal flora: toying with human motions. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2004;38(6):475–483. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000128988.13808.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, Borody & Campbell (2011).Brandt LJ, Borody TJ, Campbell J. Endoscopic fecal microbiota transplantation: first-line treatment for severe Clostridium difficile infection? Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2011;45(8):655–657. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182257d4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffie et al. (2015).Buffie CG, Bucci V, Stein RR, McKenney PT, Ling L, Gobourne A, No D, Liu H, Kinnebrew M, Viale A, Littmann E, Van Den Brink MRM, Jenq RR, Taur Y, Sander C, Cross JR, Toussaint NC, Xavier JB, Pamer EG. Precision microbiome reconstitution restores bile acid mediated resistance to Clostridium difficile. Nature. 2015;517(7533):205–208. doi: 10.1038/nature13828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffington et al. (2016).Buffington SA, Di Prisco GV, Auchtung TA, Ajami NJ, Petrosino JF, Costa-Mattioli M. Microbial reconstitution reverses maternal diet-induced social and synaptic deficits in offspring. Cell. 2016;165(7):1762–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buie (2015).Buie T. Potential etiologic factors of microbiome disruption in autism. Clinical Therapeutics. 2015;37(5):976–983. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunyavanich et al. (2016).Bunyavanich S, Shen N, Grishin A, Wood R, Burks W, Dawson P, Jones SM, Leung DYM, Sampson H, Sicherer S, Clemente JC. Early-life gut microbiome composition and milk allergy resolution. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2016;138(4):1122–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Heap & Minton (2010).Burns DA, Heap JT, Minton NP. Clostridium difficile spore germination: an update. Research in Microbiology. 2010;161(9):730–734. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota, Ianiro & Gasbarrini (2014).Cammarota G, Ianiro G, Gasbarrini A. Fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2014;48(8):693–702. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammarota et al. (2015).Cammarota G, Masucci L, Ianiro G, Bibbò S, Dinoi G, Costamagna G, Sanguinetti M, Gasbarrini A. Randomised clinical trial: faecal microbiota transplantation by colonoscopy vs. vancomycin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2015;41(9):835–843. doi: 10.1111/apt.13144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho et al. (2012).Carvalho FA, Aitken JD, Vijay-Kumar M, Gewirtz AT. Toll-like receptor-gut microbiota interactions: perturb at your own risk! Annual Review of Physiology. 2012;74(1):177–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash et al. (2006).Cash HL, Whitham CV, Behrendt CL, Hooper LV. Symbiotic bacteria direct expression of an intestinal bactericidal lectin. Science. 2006;313(5790):1126–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.1127119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier et al. (2015).Chevalier C, Stojanović O, Colin DJ, Suarez-Zamorano N, Tarallo V, Veyrat-Durebex C, Rigo D, Fabbiano S, Stevanović A, Hagemann S, Montet X, Seimbille Y, Zamboni N, Hapfelmeier S, Trajkovski M. Gut microbiota orchestrates energy homeostasis during cold. Cell. 2015;163(6):1360–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong, Bloomfield & O'Sullivan (2018).Chong C, Bloomfield F, O'Sullivan J. Factors affecting gastrointestinal microbiome development in neonates. Nutrients. 2018;10(3):274. doi: 10.3390/nu10030274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu et al. (2017).Chu DM, Ma J, Prince AL, Antony KM, Seferovic MD, Aagaard KM. Maturation of the infant microbiome community structure and function across multiple body sites and in relation to mode of delivery. Nature Medicine. 2017;23(3):314–326. doi: 10.1038/nm.4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung et al. (2012).Chung H, Pamp SJ, Hill JA, Surana NK, Edelman SM, Troy EB, Reading NC, Villablanca EJ, Wang S, Mora JR, Umesaki Y, Mathis D, Benoist C, Relman DA, Kasper DL. Gut immune maturation depends on colonization with a host-specific microbiota. Cell. 2012;149(7):1578–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke et al. (2014).Clarke G, Stilling RM, Kennedy PJ, Stanton C, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Minireview: gut microbiota: the neglected endocrine organ. Molecular Endocrinology. 2014;28(8):1221–1238. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claud et al. (2013).Claud EC, Keegan KP, Brulc JM, Lu L, Bartels D, Glass E, Chang EB, Meyer F, Antonopoulos DA. Bacterial community structure and functional contributions to emergence of health or necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Microbiome. 2013;1(1):20. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleusix et al. (2007).Cleusix V, Lacroix C, Vollenweider S, Duboux M, Le Blay G. Inhibitory activity spectrum of reuterin produced by Lactobacillus reuteri against intestinal bacteria. BMC Microbiology. 2007;7(1):101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn & Koropatkin (2016).Cockburn DW, Koropatkin NM. Polysaccharide degradation by the intestinal microbiota and its influence on human health and disease. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2016;428(16):3230–3252. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado et al. (2016).Collado MC, Rautava S, Aakko J, Isolauri E, Salminen S. Human gut colonisation may be initiated in utero by distinct microbial communities in the placenta and amniotic fluid. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1):23129. doi: 10.1038/srep23129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier-Maillard et al. (2013).Couturier-Maillard A, Secher T, Rehman A, Normand S, De Arcangelis A, Haesler R, Huot L, Grandjean T, Bressenot A, Delanoye-Crespin A, Gaillot O, Schreiber S, Lemoine Y, Ryffel B, Hot D, Nùñez G, Chen G, Rosenstiel P, Chamaillard M. NOD2-mediated dysbiosis predisposes mice to transmissible colitis and colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2013;123(2):700. doi: 10.1172/JCI62236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui et al. (2015).Cui B, Li P, Xu L, Zhao Y, Wang H, Peng Z, Xu H, Xiang J, He Z, Zhang T, Nie Y, Wu K, Fan D, Ji G, Zhang F. Step-up fecal microbiota transplantation strategy: a pilot study for steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2015;13(1):298. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0646-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui et al. (2017a).Cui M, Xiao H, Li Y, Zhou L, Zhao S, Luo D, Zheng Q, Dong J, Zhao Y, Zhang X, Zhang J, Lu L, Wang H, Fan S. Faecal microbiota transplantation protects against radiation-induced toxicity. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2017a;9(4):448–461. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui et al. (2017b).Cui L, Zhao T, Hu H, Zhang W, Hua X. Association study of gut flora in coronary heart disease through high-throughput sequencing. BioMed Research International. 2017b;2017:3796359. doi: 10.1155/2017/3796359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen et al. (2015).Cullen TW, Schofield WB, Barry NA, Putnam EE, Rundell EA, Trent MS, Degnan PH, Booth CJ, Yu H, Goodman AL. Antimicrobial peptide resistance mediates resilience of prominent gut commensals during inflammation. Science. 2015;347(6218):170–175. doi: 10.1126/science.1260580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya et al. (2017).Dahiya DK, Renuka, Puniya M, Shandilya UK, Dhewa T, Kumar N, Kumar S, Puniya AK, Shukla P. Gut microbiota modulation and its relationship with obesity using prebiotic fibers and probiotics: a review. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2017;8:563. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmasso et al. (2011).Dalmasso G, Nguyen HTT, Yan Y, Laroui H, Charania MA, Ayyadurai S, Sitaraman SV, Merlin D, DeLeo FR. Microbiota modulate host gene expression via microRNAs. PLOS ONE. 2011;6(4):e19293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damman et al. (2014).Damman C, Brittnacher M, Hayden H, Radey M, Hager K, Miller S, Zisman TL. Su1403 single colonoscopically administered fecal microbiota transplant for ulcerative colitis-a pilot study to determine therapeutic benefit and graft stability. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):S-460. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(14)61646-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- David et al. (2014).David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA, Biddinger SB, Dutton RJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davido et al. (2017).Davido B, Batista R, Michelon H, Lepainteur M, Bouchand F, Lepeule R, Salomon J, Vittecoq D, Duran C, Escaut L, Sobhani I, Paul M, Lawrence C, Perronne C, Chast F, Dinh A. Is faecal microbiota transplantation an option to eradicate highly drug-resistant enteric bacteria carriage? Journal of Hospital Infection. 2017;95(4):433–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Palma et al. (2017).De Palma G, Lynch MDJ, Lu J, Dang VT, Deng Y, Jury J, Umeh G, Miranda PM, Pigrau Pastor M, Sidani S, Pinto-Sanchez MI, Philip V, McLean PG, Hagelsieb M-G, Surette MG, Bergonzelli GE, Verdu EF, Britz-McKibbin P, Neufeld JD, Collins SM, Bercik P. Transplantation of fecal microbiota from patients with irritable bowel syndrome alters gut function and behavior in recipient mice. Science Translational Medicine. 2017;9(379):eaaf6397. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vrese & Marteau (2007).De Vrese M, Marteau PR. Probiotics and prebiotics: effects on diarrhea. Journal of Nutrition. 2007;137(3):803S–811S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.3.803S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFilipp et al. (2018).DeFilipp Z, Peled JU, Li S, Mahabamunuge J, Dagher Z, Slingerland AE, Del Rio C, Valles B, Kempner ME, Smith M, Brown J, Dey BR, El-Jawahri A, McAfee SL, Spitzer TR, Ballen KK, Sung AD, Dalton TE, Messina JA, Dettmer K, Liebisch G, Oefner P, Taur Y, Pamer EG, Holler E, Mansour MK, Van den Brink MRM, Hohmann E, Jenq RR, Chen Y-B. Third-party fecal microbiota transplantation following allo-HCT reconstitutes microbiome diversity. Blood Advances. 2018;2(7):745–753. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018017731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai et al. (2016).Desai MS, Seekatz AM, Koropatkin NM, Kamada N, Hickey CA, Wolter M, Pudlo NA, Kitamoto S, Terrapon N, Muller A, Young VB, Henrissat B, Wilmes P, Stappenbeck TS, Núñez G, Martens EC. A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility. Cell. 2016;167(5):1339–1353.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dethlefsen et al. (2008).Dethlefsen L, Huse S, Sogin ML, Relman DA. The pervasive effects of an antibiotic on the human gut microbiota, as revealed by deep 16S rRNA sequencing. PLOS Biology. 2008;6(11):e280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dethlefsen & Relman (2010).Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;108:4554–4561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicksved et al. (2009).Dicksved J, Lindberg M, Rosenquist M, Enroth H, Jansson JK, Engstrand L. Molecular characterization of the stomach microbiota in patients with gastric cancer and in controls. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2009;58(4):509–516. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.007302-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiulio et al. (2008).DiGiulio DB, Romero R, Amogan HP, Kusanovic JP, Bik EM, Gotsch F, Kim CJ, Erez O, Edwin S, Relman DA, Fisk NM. Microbial prevalence, diversity and abundance in amniotic fluid during preterm labor: a molecular and culture-based investigation. PLOS ONE. 2008;3(8):e3056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding et al. (2017).Ding C, Fan W, Gu L, Tian H, Ge X, Gong J, Nie Y, Li N. Outcomes and prognostic factors of fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with slow transit constipation: results from a prospective study with long-term follow-up. Gastroenterology Report. 2017;6(2):101–107. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gox036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinleyici et al. (2012).Dinleyici EC, Eren M, Ozen M, Yargic ZA, Vandenplas Y. Effectiveness and safety of Saccharomyces boulardii for acute infectious diarrhea. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2012;12(4):395–410. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.664129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djuranovic, Nahvi & Green (2012).Djuranovic S, Nahvi A, Green R. miRNA-mediated gene silencing by translational repression followed by mRNA deadenylation and decay. Science. 2012;336(6078):237–240. doi: 10.1126/science.1215691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Bello et al. (2010).Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N, Knight R. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(26):11971–11975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earle et al. (2015).Earle KA, Billings G, Sigal M, Lichtman JS, Hansson GC, Elias JE, Amieva MR, Huang KC, Sonnenburg JL. Quantitative imaging of gut microbiota spatial organization. Cell Host & Microbe. 2015;18(4):478–488. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiseman et al. (1958).Eiseman B, Silen W, Bascom GS, Kauvar AJ. Fecal enema as an adjunct in the treatment of pseudomembranous enterocolitis. Surgery. 1958;44(5):854–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everard et al. (2013).Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, Ouwerkerk JP, Druart C, Bindels LB, Guiot Y, Derrien M, Muccioli GG, Delzenne NM, De Vos WM, Cani PD. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the Unites States of America. 2013;110(22):9066–9071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219451110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich (2013).Friedrich MJ. Genomes of microbes inhabiting the body offer clues to human health and disease. JAMA. 2013;309(14):1447–1449. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao et al. (2010).Gao XW, Mubasher M, Fang CY, Reifer C, Miller LE. Dose-response efficacy of a proprietary probiotic formula of Lactobacillus acidophilus CL1285 and Lactobacillus casei LBC80R for antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea prophylaxis in adult patients. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105(7):1636–1641. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge et al. (2017).Ge X, Ding C, Zhao W, Xu L, Tian H, Gong J, Zhu M, Li J, Li N. Antibiotics-induced depletion of mice microbiota induces changes in host serotonin biosynthesis and intestinal motility. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2017;15(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-1105-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerassy-Vainberg et al. (2018).Gerassy-Vainberg S, Blatt A, Danin-Poleg Y, Gershovich K, Sabo E, Nevelsky A, Daniel S, Dahan A, Ziv O, Dheer R, Abreu MT, Koren O, Kashi Y, Chowers Y. Radiation induces proinflammatory dysbiosis: transmission of inflammatory susceptibility by host cytokine induction. Gut. 2018;67(1):97–107. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-313789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson et al. (2017).Gibson GR, Hutkins R, Sanders ME, Prescott SL, Reimer RA, Salminen SJ, Scott K, Stanton C, Swanson KS, Cani PD, Verbeke K, Reid G. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2017;14(8):491–502. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson & Roberfroid (1995).Gibson GR, Roberfroid MB. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: introducing the concept of prebiotics. Journal of Nutrition. 1995;125(6):1401–1412. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.6.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, Hauth & Andrews (2000).Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(20):1500–1507. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich et al. (2014).Goodrich JK, Waters JL, Poole AC, Sutter JL, Koren O, Blekhman R, Beaumont M, Van Treuren W, Knight R, Bell JT, Spector TD, Clark AG, Ley RE. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell. 2014;159(4):789–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal et al. (2018).Goyal A, Yeh A, Bush BR, Firek BA, Siebold LM, Rogers MB, Kufen AD, Morowitz MJ. Safety, clinical response, and microbiome findings following fecal microbiota transplant in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2018;24(2):410–421. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izx035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grehan et al. (2010).Grehan MJ, Borody TJ, Leis SM, Campbell J, Mitchell H, Wettstein A. Durable alteration of the colonic microbiota by the administration of donor fecal flora. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2010;44(8):551–561. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181e5d06b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groer et al. (2014).Groer MW, Luciano AA, Dishaw LJ, Ashmeade TL, Miller E, Gilbert JA. Development of the preterm infant gut microbiome: a research priority. Microbiome. 2014;2(1):38. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grönlund et al. (2000).Grönlund MM, Arvilommi H, Kero P, Lehtonen OP, Isolauri E. Importance of intestinal colonisation in the maturation of humoral immunity in early infancy: a prospective follow up study of healthy infants aged 0-6 months. Archives of Disease in Childhood—Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2000;83(3):F186–F192. doi: 10.1136/fn.83.3.F186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross (2007).Gross L. Microbes colonize a baby’s gut with distinction. PLOS Biology. 2007;5(7):e191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guaraldi & Salvatori (2012).Guaraldi F, Salvatori G. Effect of breast and formula feeding on gut microbiota shaping in newborns. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2012;2:94. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkjær et al. (2018).Halkjær SI, Christensen AH, Lo BZS, Browne PD, Günther S, Hansen LH, Petersen AM. Faecal microbiota transplantation alters gut microbiota in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: results from a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Gut. 2018;67(12):2107–2115. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton et al. (2012).Hamilton MJ, Weingarden AR, Sadowsky MJ, Khoruts A. Standardized frozen preparation for transplantation of fecal microbiota for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107(5):761–767. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harsch & Konturek (2019).Harsch IA, Konturek PC. Adhesion ileus after fecal microbiota transplantation in long-standing radiation colitis. Case Reports in Gastrointestinal Medicine. 2019;2019(6):1–4. doi: 10.1155/2019/2543808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He et al. (2017).He Z, Li P, Zhu J, Cui B, Xu L, Xiang J, Zhang T, Long C, Huang G, Ji G, Nie Y, Wu K, Fan D, Zhang F. Multiple fresh fecal microbiota transplants induces and maintains clinical remission in Crohn’s disease complicated with inflammatory mass. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):4753. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04984-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehemann et al. (2010).Hehemann J-H, Correc G, Barbeyron T, Helbert W, Czjzek M, Michel G. Transfer of carbohydrate-active enzymes from marine bacteria to Japanese gut microbiota. Nature. 2010;464(7290):908–912. doi: 10.1038/nature08937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans, Naegels & Holvoet (2009).Hellemans R, Naegels S, Holvoet J. Fecal transplantation for recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis, an underused treatment modality. Acta Gastro-Enterologica Belgica. 2009;72:269–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendijani & Akbari (2018).Hendijani F, Akbari V. Probiotic supplementation for management of cardiovascular risk factors in adults with type II diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Nutrition. 2018;37(2):532–541. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch et al. (2015).Hirsch BE, Saraiya N, Poeth K, Schwartz RM, Epstein ME, Honig G. Effectiveness of fecal-derived microbiota transfer using orally administered capsules for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2015;15(1):191. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0930-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holscher (2017).Holscher HD. Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2017;8(2):172–184. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1290756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holvoet et al. (2017).Holvoet T, Joossens M, Wang J, Boelens J, Verhasselt B, Laukens D, Van Vlierberghe H, Hindryckx P, De Vos M, De Looze D, Raes J. Assessment of faecal microbial transfer in irritable bowel syndrome with severe bloating. Gut. 2017;66(5):980–982. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper (2009).Hooper LV. Do symbiotic bacteria subvert host immunity? Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2009;7(5):367–374. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornig (2013).Hornig M. The role of microbes and autoimmunity in the pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric illness. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2013;25(4):488–795. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32836208de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghteling & Walker (2015).Houghteling PD, Walker WA. Why is initial bacterial colonization of the intestine important to the infant’s and child’s health? Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2015;60(3):294–307. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu et al. (2016).Hu Z, Zhang Y, Li Z, Yu Y, Kang W, Han Y, Geng X, Ge S, Sun Y. Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection on chronic periodontitis by the change of microecology and inflammation. Oncotarget. 2016;7:66700. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner & Surawicz (2006).Huebner ES, Surawicz CM. Probiotics in the prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal infections. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 2006;35(2):355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ianiro et al. (2014).Ianiro G, Bibbò S, Scaldaferri F, Gasbarrini A, Cammarota G. Fecal microbiota transplantation in inflammatory bowel disease: beyond the excitement. Medicine. 2014;93(19):e97. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikram et al. (2018).Ikram S, Hassan N, Raffat MA, Mirza S, Akram Z. Systematic review and meta-analysis of double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trials using probiotics in chronic periodontitis. Journal of Investigative and Clinical Dentistry. 2018;9(3):e12338. doi: 10.1111/jicd.12338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac et al. (2016).Isaac S, Scher JU, Djukovic A, Jiménez N, Littman DR, Abramson SB, Pamer EG, Ubeda C. Short-and long-term effects of oral vancomycin on the human intestinal microbiota. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2016;72(1):128–136. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson et al. (2010).Jakobsson HE, Jernberg C, Andersson AF, Sjölund-Karlsson M, Jansson JK, Engstrand L. Short-term antibiotic treatment has differing long-term impacts on the human throat and gut microbiome. PLOS ONE. 2010;5(3):e9836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jandhyala et al. (2015).Jandhyala SM, Talukdar R, Subramanyam C, Vuyyuru H, Sasikala M, Reddy DN. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015;21(29):8787. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i29.8787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernberg et al. (2007).Jernberg C, Löfmark S, Edlund C, Jansson JK. Long-term ecological impacts of antibiotic administration on the human intestinal microbiota. ISME Journal. 2007;1(1):56–66. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jie et al. (2017).Jie Z, Xia H, Zhong S-L, Feng Q, Li S, Liang S, Zhong H, Liu Z, Gao Y, Zhao H, Zhang D, Su Z, Fang Z, Lan Z, Li J, Xiao L, Li J, Li R, Li X, Li F, Ren H, Huang Y, Peng Y, Li G, Wen B, Dong B, Chen J-Y, Geng Q-S, Zhang Z-W, Yang H, Wang J, Wang J, Zhang X, Madsen L, Brix S, Ning G, Xu X, Liu X, Hou Y, Jia H, He K, Kristiansen K. The gut microbiome in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nature Communications. 2017;8(1):845. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00900-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez et al. (2008).Jiménez E, Marín ML, Martín R, Odriozola JM, Olivares M, Xaus J, Fernández L, Rodríguez JM. Is meconium from healthy newborns actually sterile? Research in Microbiology. 2008;159(3):187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen et al. (2018).Johnsen PH, Hilpüsch F, Cavanagh JP, Leikanger IS, Kolstad C, Valle PC, Goll R. Faecal microbiota transplantation versus placebo for moderate-to-severe irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, single-centre trial. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2018;3(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakihana et al. (2016).Kakihana K, Fujioka Y, Suda W, Najima Y, Kuwata G, Sasajima S, Mimura I, Morita H, Sugiyama D, Nishikawa H, Hattori M, Hino Y, Ikegawa S, Yamamoto K, Toya T, Doki N, Koizumi K, Honda K, Ohashi K. Fecal microbiota transplantation for patients with steroid-resistant acute graft-versus-host disease of the gut. Blood. 2016;128(16):2083–2088. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-717652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalla et al. (2014).Kalla R, Ventham NT, Kennedy NA, Quintana JF, Nimmo ER, Buck AH, Satsangi J. MicroRNAs: new players in IBD. Gut. 2014;64(3):504–517. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang et al. (2017).Kang D-W, Adams JB, Gregory AC, Borody T, Chittick L, Fasano A, Khoruts A, Geis E, Maldonado J, McDonough-Means S, Pollard EL, Roux S, Sadowsky MJ, Lipson KS, Sullivan MB, Caporaso JG, Krajmalnik-Brown R. Microbiota transfer therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: an open-label study. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0225-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson et al. (2013).Karlsson F, Tremaroli V, Nielsen J, Backhed F. Assessing the human gut microbiota in metabolic diseases. Diabetes. 2013;62(10):3341–3349. doi: 10.2337/db13-0844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassam et al. (2012).Kassam Z, Hundal R, Marshall JK, Lee CH. Fecal transplant via retention enema for refractory or recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012;172(2):191–193. doi: 10.1001/archinte.172.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassam et al. (2013).Kassam Z, Lee CH, Yuan Y, Hunt RH. Fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108(4):500–508. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly et al. (2016).Kelly CR, Khoruts A, Staley C, Sadowsky MJ, Abd M, Alani M, Bakow B, Curran P, McKenney J, Tisch A, Reinert SE, Machan JT, Brandt LJ. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on recurrence in multiply recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2016;165(9):609–616. doi: 10.7326/M16-0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly & LaMont (2008).Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile—more difficult than ever. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(18):1932–1940. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly et al. (2015).Kelly CJ, Zheng L, Campbell EL, Saeedi B, Scholz CC, Bayless AJ, Wilson KE, Glover LE, Kominsky DJ, Magnuson A, Weir TL, Ehrentraut SF, Pickel C, Kuhn KA, Lanis JM, Nguyen V, Taylor CT, Colgan SP. Crosstalk between microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and intestinal epithelial HIF augments tissue barrier function. Cell Host & Microbe. 2015;17(5):662–671. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna et al. (2016).Khanna S, Pardi DS, Kelly CR, Kraft CS, Dhere T, Henn MR, Lombardo M-J, Vulic M, Ohsumi T, Winkler J, Pindar C, McGovern BH, Pomerantz RJ, Aunins JG, Cook DN, Hohmann EL. A novel microbiome therapeutic increases gut microbial diversity and prevents recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016;214(2):173–181. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoruts et al. (2010).Khoruts A, Dicksved J, Jansson JK, Sadowsky MJ. Changes in the composition of the human fecal microbiome after bacteriotherapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2010;44:354–360. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181c87e02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoruts & Sadowsky (2016).Khoruts A, Sadowsky MJ. Understanding the mechanisms of faecal microbiota transplantation. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2016;13(9):508–516. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingensmith & Coopersmith (2016).Klingensmith NJ, Coopersmith CM. The gut as the motor of multiple organ dysfunction in critical illness. Critical Care Clinics. 2016;32(2):203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen et al. (2016).Kristensen NB, Bryrup T, Allin KH, Nielsen T, Hansen TH, Pedersen O. Alterations in fecal microbiota composition by probiotic supplementation in healthy adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Genome Medicine. 2016;8(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0300-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kump et al. (2018).Kump P, Wurm P, Gröchenig HP, Wenzl H, Petritsch W, Halwachs B, Wagner M, Stadlbauer V, Eherer A, Hoffmann KM, Deutschmann A, Reicht G, Reiter L, Slawitsch P, Gorkiewicz G, Högenauer C. The taxonomic composition of the donor intestinal microbiota is a major factor influencing the efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation in therapy refractory ulcerative colitis. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2018;47(1):67–77. doi: 10.1111/apt.14387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunde et al. (2013).Kunde S, Pham A, Bonczyk S, Crumb T, Duba M, Conrad H, Jr, Cloney D, Kugathasan S. Safety, tolerability, and clinical response after fecal transplantation in children and young adults with ulcerative colitis. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2013;56(6):597–601. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318292fa0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee et al. (2017).Lee Y-M, Kim K-S, Jacobs DR, Jr, Lee D-H. Persistent organic pollutants in adipose tissue should be considered in obesity research. Obesity Reviews. 2017;18(2):129–139. doi: 10.1111/obr.12481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis et al. (2015).Lewis BB, Buffie CG, Carter RA, Leiner I, Toussaint NC, Miller LC, Gobourne A, Ling L, Pamer EG. Loss of microbiota-mediated colonization resistance to Clostridium difficile infection with oral vancomycin compared with metronidazole. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2015;212(10):1656–1665. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley et al. (2005).Ley RE, Backhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(31):11070–11075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]