Abstract

Background

The prevention of long‐term psychological distress following traumatic events is a major concern. Systematic reviews have suggested that individual psychological debriefing is not an effective intervention at preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Over the past 20 years, other forms of intervention have been developed with the aim of preventing PTSD.

Objectives

To examine the efficacy of psychological interventions aimed at preventing PTSD in individuals exposed to a traumatic event but not identified as experiencing any specific psychological difficulties, in comparison with control conditions (e.g. usual care, waiting list and no treatment) and other psychological interventions.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and ProQuest's Published International Literature On Traumatic Stress (PILOTS) database to 3 March 2018. An earlier search of CENTRAL and the Ovid databases was conducted via the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trial Register (CCMD‐CTR) (all years to May 2016). We handsearched reference lists of relevant guidelines, systematic reviews and included study reports. Identified studies were shared with key experts in the field.

We conducted an update search (15 March 2019) and placed any new trials in the 'awaiting classification' section. These will be incorporated into the next version of this review, as appropriate.

Selection criteria

We searched for randomised controlled trials of any multiple session (two or more sessions) early psychological intervention or treatment designed to prevent symptoms of PTSD. We excluded single session individual/group psychological interventions. Comparator interventions included waiting list/usual care and active control condition. We included studies of adults who experienced a traumatic event which met the criterion A1 according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM‐IV) for PTSD.

Data collection and analysis

We entered data into Review Manager 5 software. We analysed categorical outcomes as risk ratios (RRs), and continuous outcomes as mean differences (MD) or standardised mean differences (SMDs), with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We pooled data with a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis, except where there was heterogeneity, in which case we used a random‐effects model. Two review authors independently assessed the included studies for risk of bias and discussed any conflicts with a third review author.

Main results

This is an update of a previous review.

We included 27 studies with 3963 participants. The meta‐analysis included 21 studies of 2721 participants. Seventeen studies compared multiple session early psychological intervention versus treatment as usual and four studies compared a multiple session early psychological intervention with active control condition.

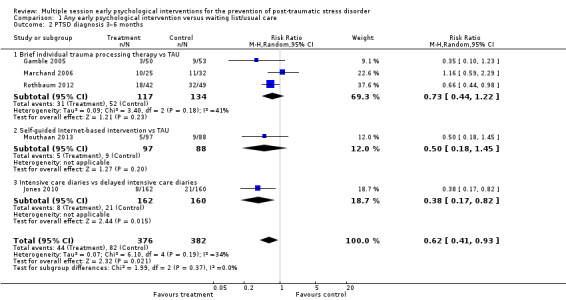

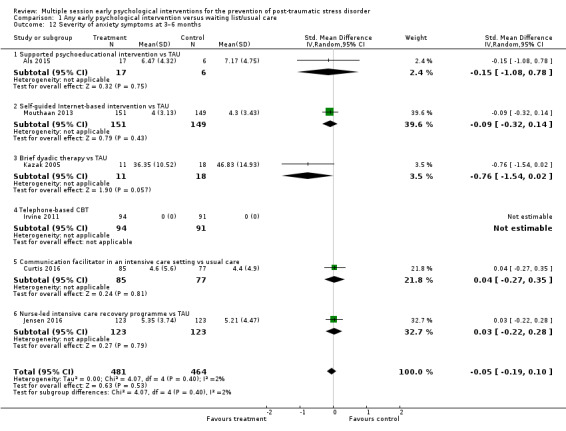

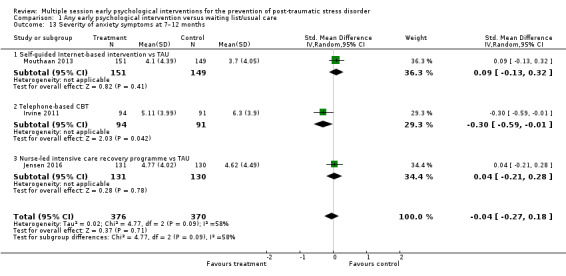

Low‐certainty evidence indicated that multiple session early psychological interventions may be more effective than usual care in reducing PTSD diagnosis at three to six months' follow‐up (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.93; I2 = 34%; studies = 5; participants = 758). However, there was no statistically significant difference post‐treatment (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.32; I2 = 0%; studies = 5; participants = 556; very low‐certainty evidence) or at seven to 12 months (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.20 to 4.49; studies = 1; participants = 132; very low‐certainty evidence). Meta‐analysis indicated that there was no statistical difference in dropouts compared with usual care (RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.95; I2 = 34%; studies = 11; participants = 1154; low‐certainty evidence) .At the primary endpoint of three to six months, low‐certainty evidence indicated no statistical difference between groups in reducing severity of PTSD (SMD –0.10, 95% CI –0.22 to 0.02; I2 = 34%; studies = 15; participants = 1921), depression (SMD –0.04, 95% CI –0.19 to 0.10; I2 = 6%; studies = 7; participants = 1009) or anxiety symptoms (SMD –0.05, 95% CI –0.19 to 0.10; I2 = 2%; studies = 6; participants = 945).

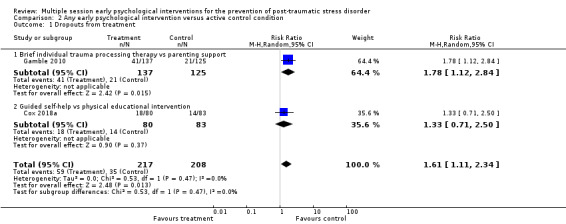

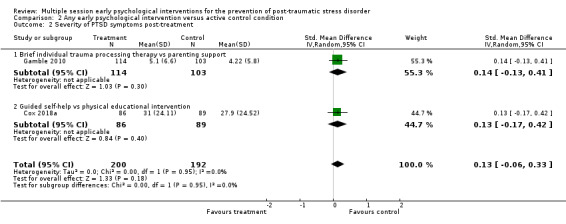

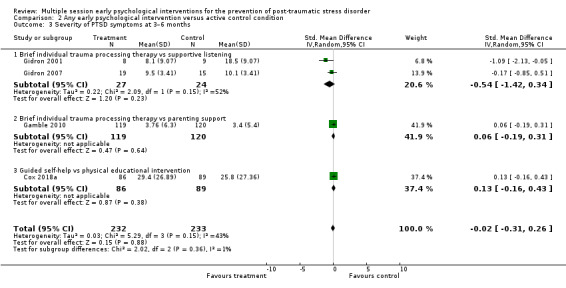

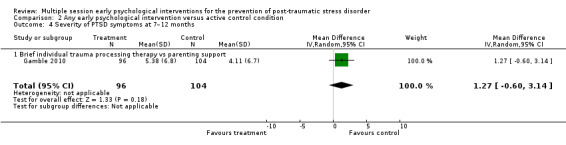

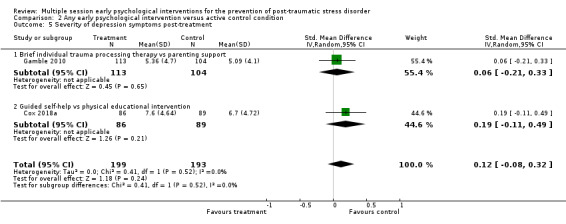

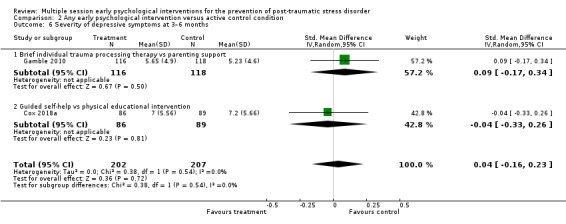

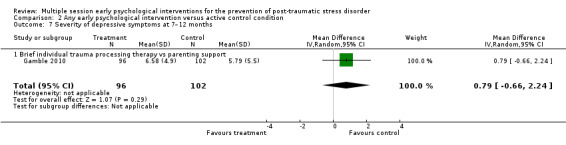

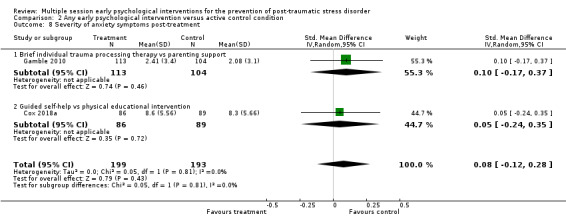

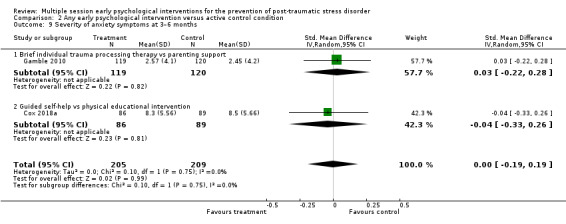

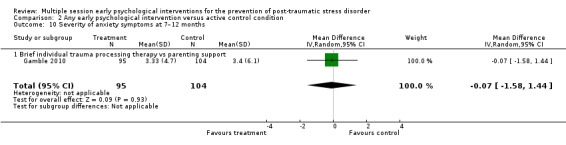

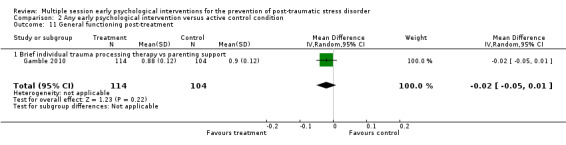

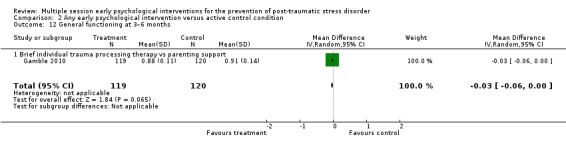

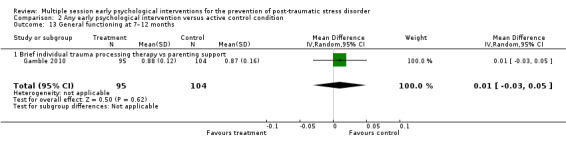

No studies comparing an intervention and active control reported outcomes for PTSD diagnosis. Low‐certainty evidence showed that interventions may be associated with a higher dropout rate than active control condition (RR 1.61, 95% CI 1.11 to 2.34; studies = 2; participants = 425). At three to six months, low‐certainty evidence indicated no statistical difference between interventions in terms of severity of PTSD symptoms (SMD –0.02, 95% CI –0.31 to 0.26; I2 = 43%; studies = 4; participants = 465), depression (SMD 0.04, 95% CI –0.16 to 0.23; I2 = 0%; studies = 2; participants = 409), anxiety (SMD 0.00, 95% CI –0.19 to 0.19; I2 = 0%; studies = 2; participants = 414) or quality of life (MD –0.03, 95% CI –0.06 to 0.00; studies = 1; participants = 239).

None of the included studies reported on adverse events or use of health‐related resources.

Authors' conclusions

While the review found some beneficial effects of multiple session early psychological interventions in the prevention of PTSD, the certainty of the evidence was low due to the high risk of bias in the included trials. The clear practice implication of this is that, at present, multiple session interventions aimed at everyone exposed to traumatic events cannot be recommended. There are a number of ongoing studies, demonstrating that this is a fast moving field of research. Future updates of this review will integrate the results of these new studies.

Keywords: Humans; Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Cognitive Behavioral Therapy/methods; Desensitization, Psychologic; Psychotherapy; Psychotherapy/methods; Quality of Life; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Stress Disorders, Post‐Traumatic; Stress Disorders, Post‐Traumatic/prevention & control; Time Factors; Waiting Lists

Plain language summary

Multiple session early psychological interventions for prevention of post‐traumatic stress disorder

Why was this review important?

Traumatic events can have a significant effect on the ability of individuals, families and communities to cope. In the past, single session interventions such as psychological debriefing were widely used with the aim of preventing continuing psychological difficulties. However, previous reviews have found that single session individual interventions have not been effective at preventing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). A range of other forms of intervention have been developed to try to prevent people exposed to trauma from developing PTSD.

Who will be interested in this review?

• People exposed to traumatic events and their loved ones.

• Professionals working in mental health services.

• General practitioners.

• Commissioners.

What questions did this review try to answer?

Are multiple session early psychological interventions (i.e. interventions over two or more sessions beginning within the first three months after the traumatic event) more effective than treatment as usual or another psychological intervention in:

• reducing the number of people diagnosed with PTSD;

• reducing the severity of PTSD symptoms;

• reducing the severity of depressive symptoms;

• reducing the severity of anxiety symptoms;

• improving the general functioning (e.g. social, psychological, occupational and functioning) of recipients of the intervention.

Which studies were included in the review?

We searched for randomised controlled trials (clinical studies where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) that examined multiple session early psychological interventions in the prevention of PTSD, published between 1970 and March 2018.

We included 27 studies with 3963 participants.

What did the evidence from the review tell us?

• We found low‐certainty evidence that multiple session early psychological interventions may be more effective than treatment as usual in preventing PTSD diagnosis three to six months after receiving the intervention.

• We found very low‐certainty evidence that multiple session early psychological interventions may be neither more nor less effective than treatment as usual in preventing PTSD, either immediately after, or at seven to 12 months after, the intervention. We also found very low‐certainty evidence that multiple session early psychological interventions may be neither more nor less effective than treatment as usual in reducing the severity of PTSD symptoms, either immediately or at subsequent points of follow‐up.

• We found low‐certainty evidence that multiple session early psychological interventions may be associated with a higher dropout rate than other psychological interventions.

• We found low‐certainty evidence that multiple session early psychological interventions may be neither more nor less effective than other psychological interventions in diagnosing PTSD; reducing the severity of PTSD, depression and anxiety; or in maintaining the general functioning of participants receiving the intervention.

• We found no studies that measured adverse effects.

• We found no studies that measured use of health‐related resources.

What should happen next?

The current evidence base is small. However, new studies are being conducted and future updates of this review will incorporate the results of these.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Any early psychological intervention compared to waiting list/usual care for the prevention of post‐traumatic stress disorder.

| Any early psychological intervention compared to waiting list/usual care for the prevention of post‐traumatic stress disorder | |||||

|

Patient or population: various Setting: various Intervention: any early psychological intervention Comparison: waiting list/usual care | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with waiting list/usual care | Risk difference with any early psychological intervention | ||||

| PTSD diagnosis: post‐treatment | 556 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | RR 1.06 (0.85 to 1.32) | Study population | |

| 283 per 1000 | 17 more per 1000 (42 fewer to 91 more) | ||||

| PTSD diagnosis: 3–6 months | 758 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,d | RR 0.62 (0.41 to 0.93) | Study population | |

| 215 per 1000 | 82 fewer per 1000 (127 fewer to 15 fewer) | ||||

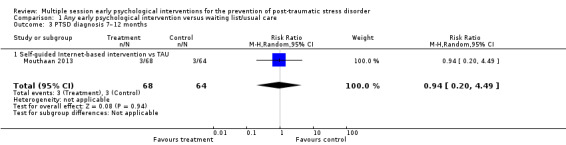

| PTSD diagnosis: 7–12 months | 132 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowe,f | RR 0.94 (0.20 to 4.49) | Study population | |

| 47 per 1000 | 3 fewer per 1000 (38 fewer to 164 more) | ||||

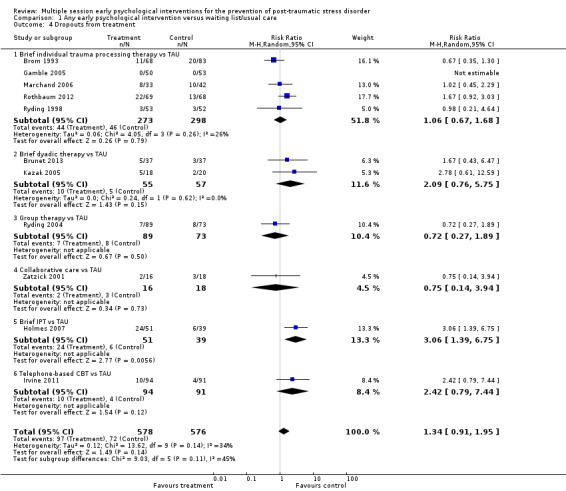

| Dropouts from treatment | 1154 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd,k | RR 1.34 (0.91 to 1.95) | Study population | |

| 125 per 1000 | 43 more per 1000 (11 fewer to 119 more) | ||||

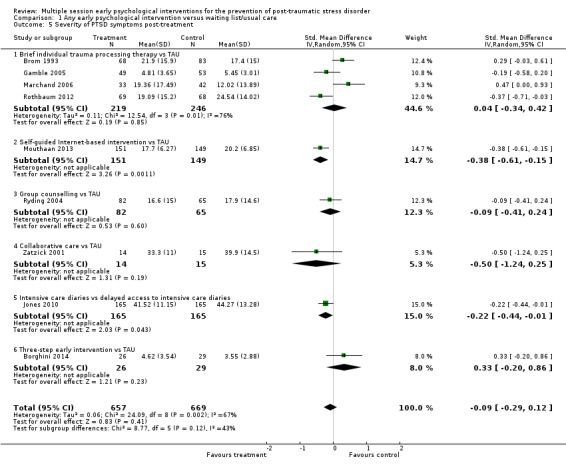

| Severity of PTSD symptoms: 3–6 months | 1921 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowg,h | — | The mean severity of PTSD symptoms: 3–6 months was 0 | SMD 0.1 lower (0.22 lower to 0.02 higher) |

| Severity of depressive symptoms: 3–6 months | 1009 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowg,i | — | The mean severity of depressive symptoms at 3–6 months was 0 | SMD 0.04 lower (0.19 lower to 0.1 higher) |

| Severity of anxiety symptoms: 3–6 months | 945 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowg,j | — | The mean severity of anxiety symptoms at 3–6 months was 0 | SMD 0.05 lower (0.19 lower to 0.10 higher) |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

aThree of the five studies were at high risk of bias (Brunet 2013; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012). bDowngraded two levels for imprecision as the total number of events was fewer than 300 and 95% CI included both little or no effect. cThree of the five studies were at high risk of bias (Jones 2010; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012). dDowngraded one level for imprecision as the total number of events was fewer than 300. eThe study was at high risk of bias (Mouthaan 2013). fDowngraded two levels as the total number of events was fewer than 300 and 95% CI included both little or no effect. gDowngraded one level for imprecision as the 95% CI includes both little or no effect. hTwelve of the 15 studies were at high risk of bias (Als 2015; Borghini 2014; Brom 1993; Brunet 2013; Curtis 2016; Holmes 2007; Jensen 2016; Jones 2010; Kazak 2005; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012; Zatzick 2001). iSix of the seven studies were at high risk of bias (Als 2015; Curtis 2016; Holmes 2007; Jensen 2016; Mouthaan 2013; Zatzick 2001). jFive of the six studies were at high risk of bias (Als 2015; Curtis 2016; Jensen 2016; Kazak 2005; Mouthaan 2013). kEight of the 11 studies were at high risk of bias (Brom 1993; Brunet 2013; Holmes 2007; Kazak 2005; Rothbaum 2012; Ryding 1998; Ryding 2004; Zatzick 2001).

Summary of findings 2. Any early psychological intervention compared to active control condition for the prevention of post‐traumatic stress disorder.

| Any early psychological intervention compared to active control condition for the prevention of post‐traumatic stress disorder | |||||

|

Patient or population: various Setting: various Intervention: any early psychological intervention Comparison: active control condition | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with active control condition | Risk difference with any early psychological intervention | ||||

| Dropouts from treatment | 425 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowe,f | RR 1.61 (1.11 to 2.34) | Study population | |

| 168 per 1000 | 103 more per 1000 (19 more to 225 more) | ||||

| Severity of PTSD symptoms: 3–6 months | 465 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,d | — | The mean severity of PTSD symptoms at 3–6 months was 0 | SMD 0.02 lower (0.31 lower to 0.26 higher) |

| Severity of depressive symptoms: 3–6 months | 409 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd,e | — | The mean severity of depressive symptoms at 3–6 months was 0 | SMD 0.04 higher (0.16 lower to 0.23 higher) |

| Severity of anxiety symptoms: 3–6 months | 414 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd,e | — | The mean severity of anxiety symptoms at 3–6 months was 0 | SMD 0 (0.19 lower to 0.19 higher) |

| General functioning: 3–6 months | 239 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowg,h | — | The mean general functioning at 3–6 months was 0 | MD 0.03 lower (0.06 lower to 0) |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

aStudy was at high risk of bias (Gidron 2001). bDowngraded two levels for imprecision as total number of events was fewer than 300 and 95% CI included both little or no effect. cAll four studies were at high risk or bias (Cox 2018a; Gamble 2010; Gidron 2001; Gidron 2007). dDowngraded one level for imprecision as 95% CI included both little or no effect. eBoth studies were at high risk of bias (Cox 2018a; Gamble 2010). fDowngraded one level for imprecision as total number of events was fewer than 300. gStudy was at high risk of bias (Gamble 2010). hDowngraded one level for imprecision as total number of participants was fewer than 400.

Background

Description of the condition

There is now a large body of literature to show that traumatic experience can cause significant psychological difficulties for large numbers of people, through events such as natural disasters (e.g. Berger 2012; Schulz 2013), human made disasters (e.g. Jenkins 2012), military combat (Brunet 2015; Richardson 2019; Stevelink 2018), rape (Dworkin 2017), violent crime (e.g. Lowe 2017; Wilson 2015), and road traffic accidents (Heron‐Delaney 2013). Many individuals show great resilience in the face of such experiences and will manifest short‐lived or subclinical stress reactions that diminish over time, although some will experience delayed onset of symptoms (Bryant 2013). Most people recover without medical or psychological assistance (McNally 2003). Nevertheless, a range of psychological difficulties may develop following trauma in some of those who have been exposed. These include depressive reactions; phobic reactions and other anxiety disorders; alcohol and other substance misuse and less frequently obsessive compulsive disorder, psychotic reactions and conversion symptoms. Some individuals display symptoms consistent with acute stress disorder (ASD) in the early phase after a traumatic event. Post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is one of the most common enduring mental health problems to occur and has probably received most attention in the research literature.

PTSD is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th edition (DSM5) as a syndrome which is comprised of four clusters of symptoms: repeated re‐experiencing of the trauma; avoidance of internal and external reminders; negative alterations in cognition and mood; and alterations in arousal and reactivity (APA 2013). For a diagnosis of PTSD to be made, symptoms have to have been present for more than one month. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 4th edition (DSM‐IV) used the term 'acute PTSD' to describe PTSD beginning before three months (APA 1994). While this term is no longer used in DSM5, the first three months continues to be seen as the priority period for early intervention. Reported rates of PTSD beginning within 12 months vary across different trauma exposed populations, with an estimated prevalence across studies at around 29% at one‐month post‐trauma and 17% at 12 months (Santiago 2013). Prevalence rates tend to be higher for people who have experienced intentional over non‐intentional trauma (Santiago 2013). Epidemiological research suggests that around 40% of people who develop early onset PTSD go on to develop a chronic disorder (Santiago 2013). The impact on social, interpersonal and occupational functioning for people who develop chronic PTSD can be very significant across the life span (Litz 2004; Kearns 2012).

Description of the intervention

To date, Cochrane Reviews have considered psychological intervention of PTSD (Bisson 2013), and pharmacological treatment of PTSD (Stein 2006). A large number of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated the effectiveness of some psychological interventions in treating chronic PTSD (Bisson 2013; NICE 2018). Trauma‐focused cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT; see Bisson 2013; Bradley 2005), and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) (NICE 2018), have the strongest evidence base. Evidence‐based interventions are not effective for everyone and many people remain symptomatic, even after treatment is completed (Bradley 2005).

Since the 1990s, clinicians have been increasingly involved in attempts to develop interventions that might mitigate against the effects of trauma and prevent the onset of chronic PTSD. For several years, single session interventions such as psychological debriefing were a widely used and popular form of intervention. Debriefing came under increasing scrutiny in the 1990s and has been the subject of one Cochrane Review first published in 1998 and subsequently updated (Rose 2002). Other reviews reported similar findings (van Emmerik 2002; Bastos 2015). The lack of evidence for the efficacy of single session individual debriefing has therefore led many experts in the field to caution against its use (e.g. NICE 2018).

How the intervention might work

Increasingly the field has turned its attention to other models of intervention (Kearns 2012; Qi 2016). These models have included multiple session interventions aimed at any individual exposed to a traumatic event with the aim of preventing the development of PTSD, interventions aimed at individuals with a known or suspected specific risk factor and interventions aimed at individuals who are clearly symptomatic. For example, psychological first aid has been increasingly prescribed as an initial form of intervention (NCTSN/NCP 2006). Psychological first aid refers to the provision of basic comfort, information, support and attendance to immediate practical and emotional needs. Brief forms of CBT offered from around two weeks' post incident have been proposed as interventions to prevent the onset of PTSD and to treat those who develop symptoms in the early stages after a trauma. Interventions aimed at enhancing social support have also been suggested (Litz 2002; Ormerod 2002). Several recent studies have been conducted to evaluate some of these forms of intervention.

Why it is important to do this review

Some experts in the field (e.g. Bisson 2003; Brewin 2008; Qi 2016) advocate interventions that are targeted at those who are most at risk of continuing psychological difficulty. However, in the immediate aftermath of a traumatic event there is often a strong imperative from healthcare services, the public and politicians to provide psychological intervention to everyone who has been exposed regardless of symptomatology. The issues of who should be offered the intervention, timing of intervention and mode of intervention are at this time still contentious. We previously published a Cochrane Review of multiple session early psychological interventions for the prevention of PTSD (Roberts 2009) in which we found 11 studies of brief psychological interventions aimed at preventing PTSD in individuals exposed to a specific traumatic event. We found no evidence to support the use of these interventions. In a second review, we found evidence for trauma‐focused CBT over a waiting list control and over supportive counselling for individuals who were displaying traumatic stress symptoms (Roberts 2010). Evidence was strongest when individuals met diagnosis for ASD or acute PTSD. This review aims to clarify the current evidence base by conducting an updated review of multiple session early interventions aimed at preventing PTSD in individuals who have been exposed to a traumatic event but have not been identified as experiencing any specific psychological difficulties.

Objectives

To examine the efficacy of psychological interventions aimed at preventing PTSD in individuals exposed to a traumatic event but not identified as experiencing any specific psychological difficulties, in comparison with control conditions (e.g. usual care, waiting list and no treatment) and other psychological interventions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs. Sample size, language and publication status were not used to determine whether or not a study should be included.

Types of participants

Any adult aged 18 years or older, exposed to a traumatic event. When a study included mixed adult and adolescent participants, we attempted to obtain separate data for adults when this was available. If this data was not available we required that at least 80% of the sample was aged 18 or over to include the study. For the purposes of the review, an event was considered traumatic if it was likely to meet criterion A1 of DSM‐IV for PTSD (APA 1994). Therefore, the majority of participants in included studies were considered to have experienced, witnessed, or been confronted with an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others.

We excluded studies that enlisted participants who met a certain symptom profile (e.g. ASD, acute PTSD, depression) or recruited participants on the basis of responses to a screening measure.

Types of interventions

This review considered any multiple session early psychological intervention designed to prevent symptoms of traumatic stress, and begun within three months of a traumatic incident. We excluded single session interventions because they are the subject of a separate Cochrane Review (Rose 2002). Early psychological interventions aimed at treating individuals who were identified as symptomatic (e.g. with ASD or acute PTSD) is subject to a separate review (Roberts 2010) conducted at the same time as this review.

For the purpose of the review, a psychological intervention included any specified non‐pharmaceutical intervention aimed at preventing the onset of PTSD offered by one or more health professional or lay person, with contact between therapist and participant on at least two occasions. We decided a priori that eligible intervention categories would include forms of psychological therapy based on a specified theoretical model. Potential intervention categories were identified from previous PTSD‐based reviews (Bisson 2013; NICE 2018). These were:

trauma‐focused cognitive behavioural therapy (TF‐CBT) – any psychological intervention that predominantly used trauma‐focused cognitive, behavioural or cognitive‐behavioural techniques. This category included exposure therapy;

stress management/relaxation – any psychological intervention that predominantly taught relaxation or anxiety/stress management techniques;

TF‐CBT group therapy – any approach delivered in a group setting that predominantly used trauma‐focused cognitive, behavioural or cognitive‐behavioural techniques;

CBT – any psychological intervention that predominantly used non‐trauma‐focused cognitive, behavioural or cognitive‐behavioural techniques. This category excluded the use of exposure therapy;

EMDR – any psychological intervention that predominantly used EMDR;

non‐trauma‐focused CBT group therapy – any approach delivered in a group that predominantly used non‐trauma‐focused cognitive, behavioural or cognitive‐behavioural techniques;

other psychological intervention – any psychological intervention that predominantly used non‐trauma‐focused techniques that would not be considered cognitive, behavioural or cognitive‐behavioural techniques. This category included non‐directive counselling, psychodynamic therapy and hypnotherapy.

We also decided a priori that eligible interventions would include non‐pharmaceutical interventions that were not based or only partially based on a specified theoretical model but that nevertheless aimed to reduce symptoms of traumatic stress, to include the following categories.

Education or information giving intervention – any intervention which predominantly provided only education or information about possible future difficulties or offered advice about constructive means of coping, or both.

Stepped care – any a priori specified care plan which offered intervention in a stepped care manner based on the continuing needs of the included participants.

Interventions aimed at enhancing positive coping skills and improving overall well‐being – any non‐pharmaceutical intervention which aimed to improve well‐being such as an occupational therapy intervention, an exercise‐based intervention or a guided self‐help intervention.

We decided a priori that the trials considered would include:

psychological intervention versus waiting list or usual care control;

psychological intervention versus other psychological intervention.

From prior knowledge of the literature, it was clear that a number of different forms of intervention had been evaluated on differing participant groups. Several studies were thought to have offered intervention to all individuals exposed. Others were known to have evaluated interventions for those who met inclusion based on predictors of future risk. We decided to undertake comparison of all interventions together initially and to undertake subanalysis on specific interventions and interventions targeted at individuals meeting specific risk factors as appropriate.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Rates of PTSD among those exposed to trauma as measured by a standard classificatory system, assessed using a standardised measure such as the Clinician‐Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake 1995).

Dropout from treatment.

Secondary outcomes

Severity of traumatic stress symptoms using a standardised measure such as the CAPS (Blake 1995), Impact of Event Scale (Horowitz 1979), the Davidson Trauma Scale (Davidson 1997), or the Post‐traumatic Diagnostic Scale (Foa 1995). In circumstances where an individual study utilised both a clinician‐administered and a self‐reported measure, primacy was given to outcomes using the clinician‐administered measure, as such measures are considered to provide the 'gold standard' in the traumatic stress field (e.g. Foa 1997).

Severity of self‐reported depressive symptoms using a standardised measure such as the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1961).

Severity of self‐reported anxiety symptoms using a standardised measure such as the Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck 1988), or the Spielberger State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger 1970)

Adverse effects.

General functioning including quality of life measures such as the 36‐item Short Form (SF‐36; Ware 1993).

Use of health‐related resources.

Comparisons involving follow‐up data would only be made when outcome data were available for similar time points. These time points were decided a priori as post‐treatment, three to six months post‐trauma, seven to 12 months post‐trauma, one to two years post‐trauma, two years and beyond. Three to six months post‐trauma was the primary outcome period.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMD‐CTR)

The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders (CCMD) Group maintains a specialised register of RCTs, the CCMD‐CTR. This register contains over 40,000 reference records (reports of RCTs) for anxiety disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, self‐harm and other mental disorders within the scope of this Group. The CCMD‐CTR is a partially studies‐based register with more than 50% of reference records tagged to approximately 12,500 individually PICO‐coded study records. Reports of trials for inclusion in the register are collated from (weekly) generic searches of MEDLINE (from 1950), Embase (from 1974) and PsycINFO (from 1967); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and review specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trial registries, drug companies, the handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings, and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Details of CCMD's core search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's website, with an example of the core MEDLINE search displayed in Appendix 1. The CCMD‐CTR fell out of date in June 2016, with the move of the editorial base from the University of Bristol to York.

Searches for this review were conducted in August 2008, May 2016 and March 2018.

Search one (1 August 2008)

CCMDCTR‐Studies: Diagnosis = "stress disorder*" or PTSD and Intervention = therapy or intervention or counsel* or debriefing and Age‐group = adult or aged or "not stated" or unclear and not Duration of therapy = "1 session"

CCMDCTR‐References: Keyword = "Stress Disorder*" or "Stress‐Disorder*" or Free‐text = PTSD and Free‐text = debrief* or *therap* or intervention* or counsel*

Search two (6 May 2016)

CCMDCTR‐Studies Register: (PTSD or posttrauma* or post‐trauma* or "post trauma*" or "combat disorder*" or "stress disorder*"):sco,stc CCDMDCTR‐References Register: (PTSD or posttrauma* or post‐trauma* or "post trauma*" or "combat disorder*" or "stress disorder*"):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc [Key to field tags. ti:title; ab:abstract; kw:keywords; ky:other keywords; mh:MeSH headings; mc:MeSH check words; emt:EMTREE headings; sco:healthcare condition; stc:target condition]

Search three (3 March 2018)

CCMD's information specialist conducted additional searches on the following bibliographic databases, using relevant subject headings (controlled vocabularies) and search syntax, appropriate to each resource.

The search was for a suite of PTSD reviews and the search terms were based on population or psychological debriefing (Appendix 2).

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Issue 2 of 12, February 2018;

Ovid MEDLINE (2014 to 3 March 2018);

Ovid Embase (2014 to 3 March 2018);

Ovid PsycINFO (2014 to 3 March 2018);

Ebsco PILOTS (2014 to 3 March 2018).

Search four (15 March 2019)

In keeping with MECIR conduct standard c37 (searches to be within 12 months of publication), we ran an update search in March 2019. We screened the abstracts and placed any new trials matching our inclusion criteria as 'awaiting classification'. These will be incorporated into the next version of this review, as appropriate.

Searching other resources

Reference lists

We searched reference lists of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence PTSD guidelines (NICE 2018), and studies identified in the search and of related review articles.

Personal communication

We provided a list of included references on the website of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies and contacted the membership to ask them to identify any studies that they thought might be missing.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (NR and CL) independently read the abstracts of all potential trials. If an abstract appeared to represent an RCT, each review author independently read the full report to determine if the trial met the inclusion criteria. When agreement could not be reached about inclusion, we consulted a third review author. The studies excluded on further reading are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, with reasons for their exclusion.

Data extraction and management

We designed a data extraction sheet to capture data that was entered into Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2014). Information extracted included demographic details of participants, details of the traumatic event, the randomisation process, the interventions used, dropout rates and outcome data. Two review authors (of NR, NK and JK) independently extracted data. When agreement could not be reached, we discussed the issue a third review author.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (of NR, NK and JK) independently assessed the risk of bias for each study, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and listed below (Higgins 2011). We resolved conflicts through discussion with a third review author (JB).

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other bias (including baseline imbalances, early termination of the trial, researcher allegiance).

We did not assess blinding of participants and personnel as a double‐blind methodology for studies of psychological treatment is impossible as it is clear to participants what treatment they are receiving.

We judged each potential source of bias as high, low or unclear, and provided a supporting quotation from the study report, together with a justification for the judgement, in the 'Risk of bias' table. We summarised risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed. We considered blinding separately for different key outcomes when necessary. When information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with a trialist, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table.

When considering treatment effects, we took into account risk of bias for studies that contributed to that outcome.

Measures of treatment effect

Continuous data

We analysed continuous outcomes using mean difference (MD) when all trials had measured outcome on the same scale. When trials measured outcomes on different scales, we used the standardised mean difference (SMD).

Dichotomous data

We used the risk ratio (RR) as the main categorical outcome measure as this is more widely used than odds ratio (OR) in health‐related practice. All outcomes were presented using 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Unit of analysis issues

For trials which had a crossover design, we considered only results from the first randomisation period. If the trial was a three (or more) armed trial, consideration was given to undertaking pair‐wise meta‐analysis with each arm, depending upon the nature of the intervention in each arm and the relevance to the review objectives. Management of cluster randomised trials followed guidance provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

When intention‐to‐treat (ITT) data were available, we reported these in the results. We attempted to access ITT data wherever possible. We used completer‐only data when this was the only type of data available. In cases where there was inadequate information within a particular paper to undertake analysis, we attempted to compute missing data from other information available within the paper, using guidance provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). For example, we calculated standard deviations (SDs) for continuous data when only the standard error (SE) or t statistics or P values were reported. When imputation was not possible or when further clarification was required, we attempted to contact the authors to request additional information. In cases where no further useable data were available, the study was not included in further analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used a visual inspection of the forest plots initially to explore for possible statistical heterogeneity (variation in intervention effects or results). We measured heterogeneity between studies by observing the I2 test and the Chi2 test (P < 0.10). An I2 of less than 30% was considered to indicate that statistical heterogeneity might not be important; an I2 of 30% to 60% to indicate moderate heterogeneity; an I2 of 50% to 90% to indicate substantial heterogeneity and an I2 greater than 75% to indicate considerable heterogeneity. Clinical and methodological heterogeneity reflect issues such as differences in participant populations, intervention types, study design and methodological rigour. We anticipated that included studies would evaluate a range of different interventions in a wide variety of populations. Therefore, we used a random‐effects model for all comparisons.

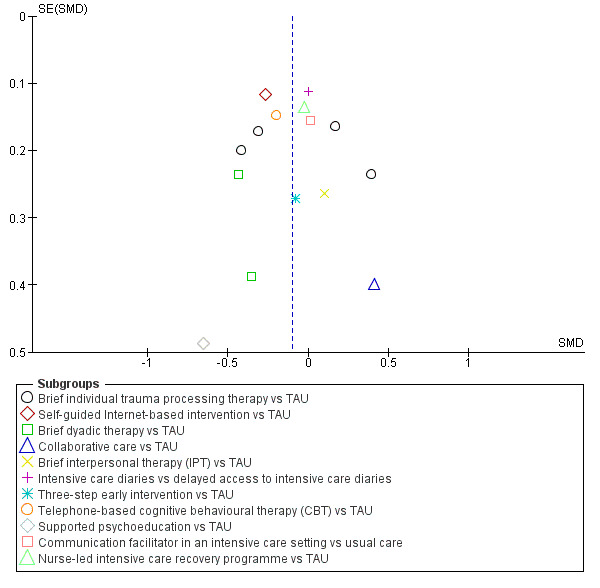

Assessment of reporting biases

It was decided a priori that if a minimum of 10 studies were available in a meta‐analysis, we would prepare funnel plots and examine them for signs of asymmetry. Where there was asymmetry, we planned to consider other possible reasons for this.

Data synthesis

We pooled data from more than one study using a fixed‐effect model, except where heterogeneity was considered to be present. In these cases, we used a random‐effects model as described below.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

It was decided a priori that we would explore the following possible causes of clinical heterogeneity if sufficient data allowed.

Number of treatment sessions taken (two to six versus seven or more).

Type of traumatic event (combat‐related trauma versus rape and sexual assault versus other civilian trauma).

Participant characteristics (men versus women)

Sensitivity analysis

It was decided a priori that sensitivity analysis would explore possible causes of methodological heterogeneity if sufficient data allowed. Analysis would be based on the following criteria.

-

Trials considered most susceptible to bias would be excluded based on the following quality assessment criteria:

those with unclear allocation concealment;

high levels of postrandomisation losses (more than 40%) or exclusions;

unblinded outcome assessment or blinding of outcome assessment uncertain.

Use of ITT analysis versus completer outcomes would be undertaken depending on available data.

'Summary of findings' tables

We evaluated the certainty of available evidence using the GRADE approach. We generated 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADEpro GDT software, which imports data from Review Manager 5 (GRADEpro GDT; Review Manager 2014). These tables provided outcome‐specific information concerning the overall certainty of evidence from studies included in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined and the sum of available data on outcomes considered. We included information on the first seven outcomes of our review: PTSD diagnosis (on a clinician‐administered scale), severity of traumatic stress symptoms, severity of self‐reported depressive symptoms, severity of self‐reported anxiety symptoms, dropouts, adverse effects and general functioning. For the primary outcome of PTSD diagnosis, we reported all time points available. For the secondary outcomes, we prioritised the primary end point of three to six months' postintervention.

We assessed the certainty of evidence using five factors.

Limitations in study design and implementation of available studies.

Indirectness of evidence.

Unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results.

Imprecision of effect estimates.

Potential publication bias.

For each outcome, we classified the certainty of evidence according to the following categories.

High certainty : further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate certainty : further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect, and may change the estimate.

Low certainty : further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect, and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low certainty : we are very uncertain about the estimate.

We downgraded the evidence from high certainty by one level for serious (or by two for very serious) study limitations (risk of bias), indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

See Figure 1.

1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

The search identified 7380 titles and abstracts and two review authors independently read 297 papers in detail to establish if they met the specified inclusion criteria.

An update search (15 March 2019) identified 781 RCT records. We screened the abstracts and have added 11 new studies to those awaiting classification.

Included studies

Twenty‐seven studies, including 11 identified in Roberts 2009, evaluated brief (two or more sessions) psychological interventions aimed at preventing PTSD in people exposed to a specific traumatic event. Twenty five studies were reported in English, one in French (Andre 1997), and one in Persian (Taghizadeh 2008). The studies are described in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Study design

All included studies were two armed RCTs, apart from one study (Lindwall 2014), which included three arms, one of which evaluated intervention offered to children which was not eligible for inclusion in this review. Participants would not have been blind to their allocation group. Sample size in the included studies varied from 17 (Gidron 2001) to 386 (Jensen 2016) participants. The total number of participants randomised in the 27 studies was 3963.

Participants

Seven studies were conducted in the USA (Biggs 2016; Cox 2018a; Curtis 2016; Kazak 2005; Lindwall 2014; Rothbaum 2012; Zatzick 2001); three in Canada (Brunet 2013; Irvine 2011; Marchand 2006); three in Australia (Gamble 2005; Gamble 2010; Holmes 2007); two in the Netherlands (Brom 1993; Mouthaan 2013); two in Israel (Gidron 2001; Gidron 2007); two in Sweden (Ryding 1998; Ryding 2004); one in France (Andre 1997); one in Iran (Taghizadeh 2008); one in the UK (Als 2015); one in Switzerland (Borghini 2014); one in Denmark (Jensen 2016); one in China (Wang 2015); one in Sri Lanka (Wijesinghe 2015); and one study was conducted in various European countries including Denmark, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and the UK (Jones 2010).

Five studies evaluated interventions offered to mothers who had experienced traumatic births (Gamble 2005; Gamble 2010; Ryding 1998; Ryding 2004; Taghizadeh 2008), while another study was of mothers of babies born at less than 33 weeks' gestation (Borghini 2014). Five studies included individuals who had been involved in road traffic accidents (Brom 1993; Gidron 2001; Gidron 2007; Wang 2015; Zatzick 2001). In four studies, participants were family members (Als 2015; Curtis 2016; Kazak 2005; Lindwall 2014): one study was in relatives of patients admitted to an intensive care unit (Curtis 2016), one was in parents whose child was newly diagnosed with cancer (Kazak 2005), one was in parents whose child received a stem cell or bone marrow transplant (Lindwall 2014), and one was in parents of a child admitted to a paediatric intensive care unit (Als 2015). Three studies were in individuals who had experienced major physical trauma and had been admitted to a trauma centre (Holmes 2007; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012), while another three were in individuals who had been admitted to an intensive care unit (Cox 2018a; Jensen 2016; Jones 2010). One study included individuals who had been exposed to armed robbery, involving acts of violence (Marchand 2006). Participants in this study had to have reported experiencing intense fear, helplessness or horror during or after the robbery for inclusion. One study was conducted in individuals who had been exposed to a life‐threatening event (Brunet 2013), one included bus drivers who had been assaulted (Andre 1997), one was in people who had received an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) (Irvine 2011), one was on military mortuary workers (Biggs 2016), and one was in snakebite victims (Wijesinghe 2015).

Interventions

Twenty‐one studies compared multiple session early interventions versus treatment as usual. Five studies used an approach which we grouped as "brief individual trauma processing" (Brom 1993; Gamble 2005; Marchand 2006; Rothbaum 2012; Ryding 1998). This subgroup consisted of a number of brief therapies – lasting two or more sessions – that were theoretically diverse but shared similar core treatment components. These included: psychoeducation, therapist directed reliving of the index trauma to promote elaboration of the trauma memory and help to contextualise or reframe aspects of the experience. Two studies used CBT (Andre 1997; Irvine 2011), two used brief dyadic CBT (therapy involving a trauma exposed individual in conjunction with a significant other person, such as a partner, spouse or other family member) (Brunet 2013; Kazak 2005), one used a self‐guided Internet‐based intervention (Mouthaan 2013), one used brief interpersonal therapy (IPT) (Holmes 2007), one used a counselling intervention (Taghizadeh 2008), one used group counselling (Ryding 2004), one used psychological first aid group sessions (Biggs 2016), one used collaborative care (Zatzick 2001), one used intensive care diaries (Jones 2010), one used three‐step early intervention (Borghini 2014), one used supported psychoeducation (Als 2015), one used communication facilitator in an intensive care setting (Curtis 2016), one used nurse‐led intensive care recovery programme (Jensen 2016), and one used creative art (Wang 2015).

Six studies compared a psychological intervention with another intervention. Two studies compared memory structuring intervention with supportive listening (Gidron 2001; Gidron 2007), one study compared CBT with an education programme (Cox 2018a), one study compared a resilience programme with parenting support (Gamble 2010), one study compared a child‐targeted intervention (massage and humour therapy) with child‐targeted plus a parent‐targeted (massage, relaxation, imagery) intervention (Lindwall 2014), and one compared psychological first aid and psychoeducation and CBT versus psychological first aid and psychoeducation (Wijesinghe 2015).

Further information about specific interventions is provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Outcomes

Most of the included studies used well validated self‐report measures of PTSD, depression or anxiety as key outcomes. Measures used are listed in the Characteristics of included studies table. The most commonly used tool for measuring PTSD was the Impact of Events Scale (IES) (Als 2015; Andre 1997; Brom 1993; Marchand 2006; Rothbaum 2012; Ryding 1998; Ryding 2004; Taghizadeh 2008), followed by the Impact of Event Scale – Revised (IES‐R) (Brunet 2013; Cox 2018a; Irvine 2011; Kazak 2005; Lindwall 2014; Mouthaan 2013; Wang 2015), Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL) (Biggs 2016; Curtis 2016; Holmes 2007; Zatzick 2001), and CAPS (Brunet 2013; Mouthaan 2013; Wang 2015). Other PTSD scales used less commonly included the Mini‐International Neuropsychiatric Interview for PTSD (MINI‐PTSD) (Gamble 2005), Perinatal Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaire (PPQ) (Borghini 2014), Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) (Jensen 2016), PTSD Symptom Scale – Interview Version (PSS‐I) (Rothbaum 2012), and Post‐traumatic Stress Symptom Scale – Self Report (PSS‐SR) (Wijesinghe 2015).

Other outcomes such as anxiety, depression and quality of life were measured using Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Als 2015; Andre 1997; Cox 2018a; Holmes 2007; Irvine 2011; Jensen 2016; Mouthaan 2013; Wang 2015), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐9) (Biggs 2016; Curtis 2016), SF‐36 (Holmes 2007; Irvine 2011; Jensen 2016; Mouthaan 2013), Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD‐7) (Curtis 2016), World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (Biggs 2016), Trauma Symptom Inventory (Brom 1993), Social Constraints Scale (SCS) (Brunet 2013), Social Adjustment Scale by Self‐Report (SAS‐SR) (Brunet 2013), EuroQol (EQ‐5D) (Cox 2018a), Patient‐Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) (Cox 2018a), Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (COPE) (Cox 2018a), Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Gamble 2005; Gamble 2010; Ryding 2004), Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale‐21 (DASS‐21) (Gamble 2005; Gamble 2010), Maternity Social Support Scale (MSSS) (Gamble 2005), and health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) (Gamble 2010).

We used data from a clinician‐administered PTSD severity measure for six studies (Brunet 2013; Gamble 2005; Jones 2010; Marchand 2006; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012). Data were only available from self‐report measures from17 trials (Als 2015; Borghini 2014; Brom 1993; Cox 2018a; Curtis 2016; Gamble 2010; Gidron 2001; Gidron 2007; Holmes 2007; Irvine 2011; Jensen 2016; Kazak 2005; Lindwall 2014; Ryding 1998; Ryding 2004; Taghizadeh 2008; Zatzick 2001).

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies table.

In this update, we culled the list of excluded studies (previously reported in the first version of this review (Roberts 2009), to those studies which narrowly missed the inclusion criteria, those readers may plausibly expect to see included.

We excluded 38 studies following access of full‐text articles, as they did not satisfy the inclusion criteria. Of these, participants already had PTSD symptoms in 34 trials (Ben‐Zion 2018; Bisson 2004; Bryant 1998; Bryant 1999; Bryant 2003; Bryant 2005; Bryant 2008; Bugg 2009; Cernvall 2015; Echeburua 1996; Ehlers 2003; Foa 2006; Freedman (in preparation); Freedman (submitted); Freyth 2010; Jarero 2011; Jarero 2015; Nixon 2012; Nixon 2016; O'Donnell (in preparation); O'Donnell 2012; Öst unpublished; Shalev 2012; Shapiro 2015; Shapiro 2018; Shaw 2013; Sijbrandij 2007; Skogstad 2015; van Emmerik 2008; Wagner 2007; Wu 2014; Zatzick 2004; Zatzick 2013; Zatzick 2015). Four studies evaluated single session interventions (Resnick 2005; Rose 1999; Rothbaum (submitted); Turpin 2005).

Studies awaiting classification

One study could not be accessed and has been included in studies awaiting classification (Kilpatrick 1984). A further 11 newly completed studies were identified in the most recent search of March 2019 and are awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table).

Ongoing studies

For details of ongoing studies, see Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

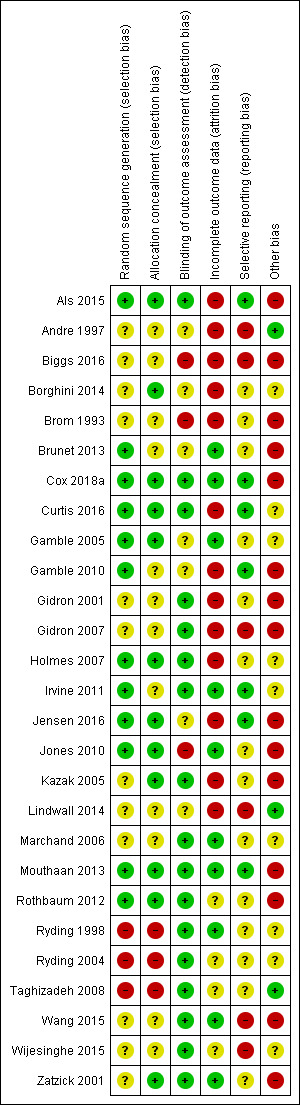

Risk of bias in included studies

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Methodological quality of many of the included studies was poor. The process of recruitment used by Brom 1993 was of particular concern as recruitment took place prior to invitation to potential participants to join the study. This may lead to significant difference in response rate, dropout rate, other dropout factors and baseline scores between the treatment and control group.

Random sequence generation

Twelve studies provided an adequate description of the randomisation process and were at low risk of selection bias (Als 2015; Brunet 2013; Cox 2018a; Curtis 2016; Gamble 2005; Gamble 2010; Holmes 2007; Irvine 2011; Jensen 2016; Jones 2010; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012). Twelve studies did not report the randomisation process and were therefore at unclear risk of selection bias (Andre 1997; Biggs 2016; Borghini 2014; Brom 1993; Gidron 2001; Gidron 2007; Kazak 2005; Lindwall 2014; Marchand 2006; Wang 2015; Wijesinghe 2015; Zatzick 2001). Three studies were at high risk of selection bias as the process was not truly random (Ryding 1998; Ryding 2004: Taghizadeh 2008). Ryding 2004 randomised women who gave birth on approximately 18 predetermined days of the month to the counselling group. Ryding 1998 selected every second emergency caesarean section patient, according to the delivery ward register, for counselling, the remainder were in the comparison group. Taghizadeh 2008 randomised participants by day of the week.

Allocation concealment

Twelve studies reported adequate concealment procedures and were at low risk of selection bias (Als 2015; Borghini 2014; Cox 2018a; Curtis 2016; Gamble 2005; Holmes 2007; Jensen 2016; Jones 2010; Kazak 2005; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012; Zatzick 2001). In 12 studies, allocation concealment was unclear or inadequate (Andre 1997; Biggs 2016; Brom 1993; Brunet 2013; Gamble 2010; Gidron 2001; Gidron 2007; Irvine 2011; Lindwall 2014; Marchand 2006; Wang 2015; Wijesinghe 2015). Three studies made no attempt to hide allocation concealment and were at high risk of selection bias (Ryding 1998; Ryding 2004; Taghizadeh 2008).

Blinding of participants and personnel

This was not assessed as a double‐blind methodology for studies of psychological treatment is impossible as it is clear to participants what treatment they are receiving.

Blinding of outcome assessors

Seventeen studies blinded outcome assessors and were at low risk of detection bias (Als 2015; Cox 2018a; Curtis 2016; Gidron 2001; Gidron 2007; Holmes 2007; Irvine 2011; Kazak 2005; Marchand 2006; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012; Ryding 1998; Ryding 2004; Taghizadeh 2008; Wang 2015; Wijesinghe 2015; Zatzick 2001). Seven studies did not report this (Andre 1997; Borghini 2014; Brunet 2013; Gamble 2005; Gamble 2010; Jensen 2016; Lindwall 2014), and three studies were at high risk of detection bias (Biggs 2016; Brom 1993; Jones 2010).

Incomplete outcome data

Ten studies fully reported loss to follow‐up and adequately dealt with missing outcome data (Brunet 2013; Cox 2018a; Gamble 2005; Irvine 2011; Jones 2010; Marchand 2006; Mouthaan 2013; Ryding 1998; Wang 2015; Zatzick 2001). Gamble 2005 included follow‐up data from all participants (one participant in the intervention group could not be contacted at initial follow‐up). Marchand 2006 and Zatzick 2001 included withdrawals in analysis by estimation of outcome by the method of 'last observation carried forward'. Thirteen studies did not adequately report missing outcome data and loss to follow‐up and were at high risk of bias (Als 2015; Andre 1997; Biggs 2016; Borghini 2014; Brom 1993; Curtis 2016; Gamble 2010; Gidron 2001; Gidron 2007; Holmes 2007; Jensen 2016; Kazak 2005; Lindwall 2014). Four studies provided data only for treatment completers and recorded withdrawals without reasons by group or the number of withdrawals was not specified and were at unclear risk of bias (Rothbaum 2012; Ryding 2004; Taghizadeh 2008; Wijesinghe 2015).

Selective reporting

Seven studies published protocols and reported on prespecified outcomes and were at low risk of reporting bias (Als 2015; Cox 2018a; Curtis 2016; Gamble 2010; Irvine 2011; Jensen 2016; Mouthaan 2013). Fourteen studies did not publish protocols and therefore it was unclear if they were free from reporting bias (Borghini 2014; Brom 1993; Brunet 2013; Gamble 2005; Gidron 2001; Holmes 2007; Jones 2010; Kazak 2005; Marchand 2006; Rothbaum 2012; Ryding 1998; Ryding 2004; Taghizadeh 2008; Zatzick 2001). One study did not report PTSD diagnosis as a primary outcome and was at high risk of reporting bias (Gidron 2007). Five other studies with null findings were at high risk of selective reporting because they did not provide data that could be used in meta‐analysis (Andre 1997; Biggs 2016; Lindwall 2014; Wang 2015; Wijesinghe 2015).

Other bias

Three studies were at low risk of other bias (Andre 1997; Lindwall 2014; Taghizadeh 2008). Nine studies were at unclear risk of other bias (Borghini 2014; Curtis 2016; Gamble 2005; Holmes 2007; Irvine 2011; Marchand 2006; Ryding 1998; Ryding 2004; Wijesinghe 2015). Fifteen studies were at high risk of other bias (Als 2015; Biggs 2016; Brom 1993; Brunet 2013; Cox 2018a; Gamble 2010; Gidron 2001; Gidron 2007; Jensen 2016; Jones 2010; Kazak 2005; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012; Wang 2015; Zatzick 2001). Reasons for studies being judged at high risk of other bias include small sample size (Als 2015; Gidron 2001; Gidron 2007; Kazak 2005; Wang 2015; Zatzick 2001), inadequate description of the intervention (Biggs 2016), evaluation of treatment adherence not reported (Biggs 2016; Gidron 2001; Gidron 2007; Jensen 2016), differences in treatment groups at baseline (Brom 1993; Gamble 2010), study authors affiliated with intervention (Brunet 2013; Gidron 2001; Gidron 2007; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012), higher‐than expected attrition rate (Cox 2018a), PTSD diagnosis based on assessor administration of PDS (Jones 2010) and intervention not manualised (Wang 2015; Zatzick 2001).

Effects of interventions

The meta‐analyses included 21 studies with 2721 participants. Results were reported for all available outcome measures specified in the methodology. None of the studies identified reported data on adverse effects or use of health‐related resources. Six studies could not be used in the meta‐analysis as they reported no useable data (Andre 1997; Biggs 2016; Lindwall 2014; Taghizadeh 2008; Wang 2015; Wijesinghe 2015).

Comparison 1: any intervention versus waiting list/usual care

Twenty‐one studies compared a psychological intervention against a waiting list or treatment as usual condition (Als 2015; Andre 1997; Biggs 2016; Borghini 2014; Brom 1993; Brunet 2013; Curtis 2016; Gamble 2005; Holmes 2007; Irvine 2011; Jensen 2016; Jones 2010; Kazak 2005; Marchand 2006; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012; Ryding 1998; Ryding 2004; Taghizadeh 2008; Wang 2015; Zatzick 2001).

Primary outcome

1. PTSD diagnosis

Six studies used a clinician‐administered scale to measure PTSD diagnosis and were entered into the meta‐analyses (Brunet 2013; Gamble 2005; Jones 2010; Marchand 2006; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012). The remaining 15 studies used a self‐reported measure and were not included in the meta‐analyses (Als 2015; Andre 1997; Biggs 2016; Borghini 2014; Brom 1993; Curtis 2016; Holmes 2007; Irvine 2011; Jensen 2016; Kazak 2005; Ryding 1998; Ryding 2004; Taghizadeh 2008; Wang 2015; Zatzick 2001).

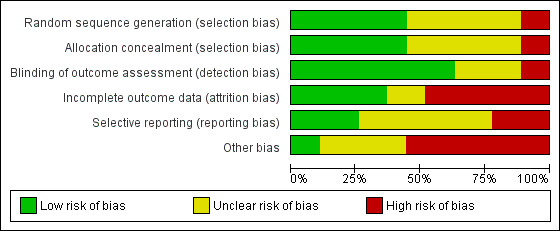

Post‐treatment

Five studies provided data on clinician‐administered diagnosis of PTSD (Brunet 2013; Gamble 2005; Marchand 2006; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012). Post‐treatment there was a lack of evidence for difference between intervention and control conditions (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.32; I2 = 0%; studies = 5; participants = 556; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any early psychological intervention versus waiting list/usual care, Outcome 1 PTSD diagnosis post‐treatment.

When analysed by type of psychological intervention, there was a lack of evidence for difference between treatment as usual and brief individual trauma processing therapy (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.40; I2 = 0%; studies = 3; participants = 262). There was uncertainty in estimating differences between treatment as usual and self‐guided Internet‐based interventions (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.40 to 2.06; studies = 1; participants = 228), brief dyadic CBT (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.61; studies = 1; participants = 66) reflected by the very wide confidence intervals.

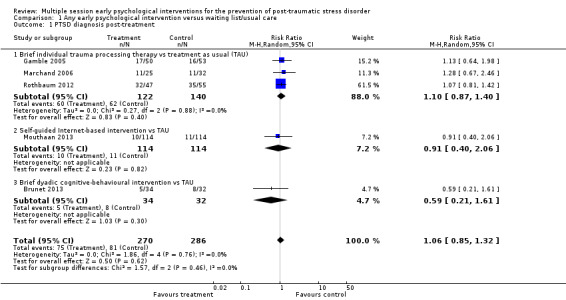

Three to six months' follow‐up

Five studies provided data on clinician‐administered diagnosis of PTSD at three to six months' follow‐up (Gamble 2005; Jones 2010; Marchand 2006; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012). Multiple session early psychological interventions were associated with a reduction in PTSD symptoms compared to treatment as usual (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.93; I2 = 34%; studies = 5; participants = 758; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any early psychological intervention versus waiting list/usual care, Outcome 2 PTSD diagnosis 3–6 months.

When analysed by type of intervention, meta‐analysis of three studies identified uncertainty for the difference between treatment as usual and brief individual trauma processing therapy reflected in the wide confidence interval (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.22; I2 = 41%; studies = 3; participants = 251). There was considerable imprecision in estimating the difference between self‐guided Internet‐based interventions and treatment as usual (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.18 to 1.45; studies = 1; participants = 185). Evidence from one study of 322 participants showed that intensive care diaries were more effective than delayed access to diaries (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.82).

Seven to 12 months' follow‐up

One study measured clinician‐administered PTSD at seven to 12 months' follow‐up (Mouthaan 2013). There was very high imprecision in estimating differences between self‐guided Internet‐based intervention and treatment as usual (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.20 to 4.49; studies = 1; participants = 132; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any early psychological intervention versus waiting list/usual care, Outcome 3 PTSD diagnosis 7–12 months.

2. Dropout from treatment

Eleven studies provided data on the number of participants who left the study early (Brom 1993; Brunet 2013; Gamble 2005; Holmes 2007; Irvine 2011; Kazak 2005; Marchand 2006; Rothbaum 2012; Ryding 1998; Ryding 2004; Zatzick 2001). Meta‐analysis indicated that there was no significant difference in dropouts (RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.95; I2 = 34%; studies = 11; participants = 1154; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any early psychological intervention versus waiting list/usual care, Outcome 4 Dropouts from treatment.

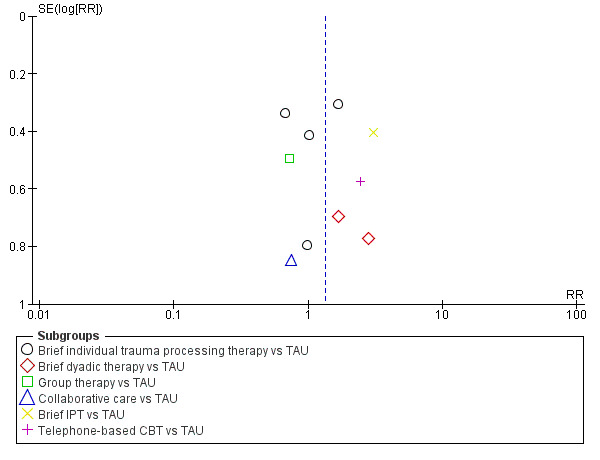

When analysed by type of intervention, evidence from one study indicated brief IPT was associated with a higher dropout rate than TAU (RR 3.06, 95% CI 1.39 to 6.75; participants = 90). There was no significant difference, and wide confidence intervals, in the dropout rates between treatment as usual and brief individual trauma processing therapy (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.68; I2 = 26%; studies = 5; participants = 571), brief dyadic therapy (RR 2.09, 95% CI 0.76 to 5.75; I2 = 0%; studies = 2; participants = 112), group therapy (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.89; studies = 1; participants = 162), collaborative care (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.14 to 3.94; studies = 1; participants = 34), or telephone‐based CBT (RR 2.42, 95% CI 0.79 to 7.44; studies = 1; participants = 185).

Secondary outcomes

1. Severity of PTSD symptoms

Post‐treatment

Nine studies provided data on the severity of PTSD symptoms post‐treatment (Borghini 2014; Brom 1993; Gamble 2005; Jones 2010; Marchand 2006; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012; Ryding 2004; Zatzick 2001). Meta‐analysis showed no evidence of a difference between multiple session early psychological interventions and treatment as usual (SMD –0.09, 95% CI –0.29 to 0.12; studies = 9; participants = 1326; Analysis 1.5). There was a high degree of heterogeneity in this result (I2 = 67%).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any early psychological intervention versus waiting list/usual care, Outcome 5 Severity of PTSD symptoms post‐treatment.

When analysed by type of intervention, evidence from one study of 300 participants indicated that self‐guided Internet‐based CBT may be more effective than treatment as usual (SMD –0.38, 95% CI –0.61 to –0.15). Another study of 330 participants showed that intensive care diaries may be more effective than delayed access to diaries in reducing severity of PTSD symptoms postintervention (SMD –0.22, 95% CI –0.44 to –0.01). There was very high imprecision (wide confidence intervals) in estimating differences between treatment as usual and brief individual trauma processing therapy (SMD 0.04, 95% CI –0.34 to 0.425; I2 = 76%; studies = 4; participants = 46), group counselling (SMD –0.09, 95% CI –0.41 to 0.24; studies = 1; participants = 147), collaborative care (SMD –0.50, 95% CI –1.24 to 0.25; studies = 1; participants = 29), three‐step early intervention (SMD 0.33, 95% CI –0.20 to 0.86; studies = 1; participants = 55).

It is evident that the heterogeneity in the group of participants who received brief individual trauma processing therapy contributed to the overall heterogeneity observed. It was not possible to investigate heterogeneity by number of sessions of the intervention, time between trauma exposure and intervention or type of traumatic event. However, it was possible to undertake a sensitivity analysis to look into gender of participants. Of the four studies on brief individual trauma processing therapy, one was done in women only (Gamble 2005). However, removing this study from the meta‐analysis had little effect on the heterogeneity within this group (I2 = 82%). In the subgroup analysis, there was no evidence (Χ2=0.89, P=0.35) of difference between studies of brief individual trauma processing therapy targeting women only (SMD –0.19, 95% CI –0.58 to 0.20; studies = 1; participants = 102) and studies where gender was mixed (SMD 0.12, 95% CI –0.39 to 0.62; studies = 3; participants = 363). But the small number of studies limits the ability to identify differences between subgroups.

We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis excluding studies with unclear allocation concealment, high levels of post‐randomisation losses (greater than 40%) and unblinded outcome assessment or blinding of outcome assessment uncertain. However, this was not possible as three studies were at unclear risk of selection bias (Brom 1993; Gamble 2005; Marchand 2006), two studies were at high risk of attrition bias (Brom 1993; Rothbaum 2012), and two studies failed to blind or failed to report the blinding of outcome assessors (Brom 1993; Gamble 2005).

One study measured severity of PTSD symptoms using the PCL‐17 (Biggs 2016). Data were not in a usable format for meta‐analysis. Authors reported that the severity of PTSD symptoms did not differ significantly between the intervention and control group at one or two months' post‐treatment.

Three to six months' follow‐up

Fifteen studies provided data on the severity of PTSD symptoms at three to six months' follow‐up (Als 2015; Borghini 2014; Brom 1993; Brunet 2013; Curtis 2016; Gamble 2005; Holmes 2007; Irvine 2011; Jensen 2016; Jones 2010; Kazak 2005; Marchand 2006; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012; Zatzick 2001). There was no significant difference in severity of PTSD symptoms between multiple session early psychological interventions and treatment as usual (SMD –0.10, 95% CI –0.22 to 0.02; I2 = 34%; studies = 15; participants = 1921; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any early psychological intervention versus waiting list/usual care, Outcome 6 Severity of PTSD symptoms: 3–6 months.

When analysed by type of intervention, evidence from one study (300 participants) indicated that self‐guided Internet‐based CBT may be more effective than treatment as usual (SMD –0.27, 95% CI –0.50 to –0.04). Two studies on a total of 103 participants showed that brief dyadic therapy may be more effective in reducing severity of PTSD symptoms three to six months' post‐treatment (SMD –0.41, 95% CI –0.81 to –0.02). None of the other interventions (brief individual trauma processing therapy, collaborative care, brief IPT, intensive care diaries, three‐step early intervention, telephone‐based CBT, supported psychoeducation, communication facilitation in an ICU setting and nurse‐led ICU recovery programme), showed any evidence of effectiveness over treatment as usual in the severity of PTSD symptoms three to six months' postintervention.

One study measured severity of PTSD at six months but could not be entered in the meta‐analysis as authors did not report SDs (Andre 1997). The mean IES in the group receiving CBT decreased from 21.7 to 17.2, while the mean IES in the control group decreased from 15.6 to 12.0. However, data were only available for 39/65 participants in the intervention group and 45/67 in the control group.

One study measured severity of PTSD symptoms using the PCL‐17 (Biggs 2016). Data were not in a usable format for meta‐analysis. Authors reported that the severity of PTSD symptoms did not differ significantly between the intervention and control group at three or four months' post‐treatment.

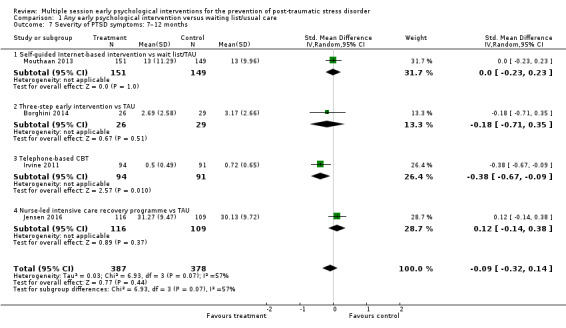

Seven to 12 months' follow‐up

Four studies provided data on the severity of PTSD symptoms at seven to 12 months' follow‐up (Borghini 2014; Irvine 2011; Jensen 2016; Mouthaan 2013). There was no evidence of difference in severity of PTSD symptoms between multiple session early psychological interventions and treatment as usual (SMD –0.09, 95% CI –0.32 to 0.14; I2 = 57%; studies = 4; participants = 765; Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any early psychological intervention versus waiting list/usual care, Outcome 7 Severity of PTSD symptoms: 7–12 months.

It was not possible to investigate heterogeneity by number of sessions of the intervention, time between trauma exposure and intervention, or type of traumatic event. One study was conducted in women only, but excluding this from the meta‐analysis had little effect on the heterogeneity (I2 = 70%) (Borghini 2014). We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias. However, this was not possible as three of the four studies which measured this outcome at seven to 12 months were at unclear risk of selection bias (Irvine 2011), unclear risk of detection bias (Borghini 2014; Jensen 2016), and high risk of attrition bias (Borghini 2014; Jensen 2016).

When analysed by type of intervention, evidence from one study (185 participants) indicated that telephone‐based CBT may be more effective than treatment as usual (SMD –0.38, 95% CI –0.67 to –0.09). For all other comparisons, confidence intervals were wide reflecting uncertainty in differences between treatment as usual and self‐guided Internet‐based CBT (SMD 0.00, 95% CI –0.23 to 0.23; studies = 1; participants = 300), three‐step early intervention (SMD –0.18, 95% CI –0.71 to 0.35; studies = 1; participants = 55), or nurse‐led intensive care recovery programme (SMD 0.12, 95% CI –0.14 to 0.38; studies = 1; participants = 225).

The study by Wang 2015 measured severity of PTSD symptoms at 12 months' follow‐up. Authors did not report SDs and, therefore, it could not be used in a meta‐analysis. There were no significant differences between group in terms of PTSD severity as measured by the CAPS score (P = 0.74) or the IES‐R score (P = 0.68).

One study measured severity of PTSD symptoms using the PCL‐17 (Biggs 2016). Data were not in a usable format for meta‐analysis. Authors reported that the severity of PTSD symptoms did not differ significantly between the intervention and control group at seven or 10 months' post‐treatment.

2. Severity of depressive symptoms

Post‐treatment

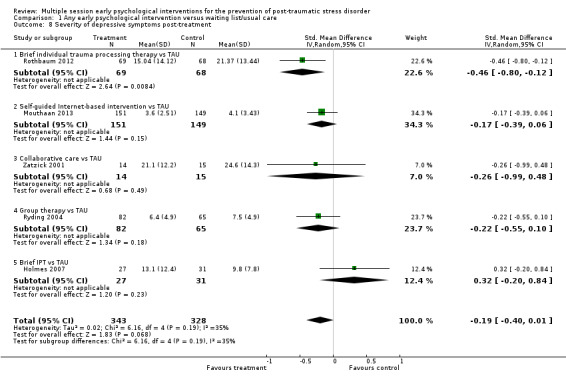

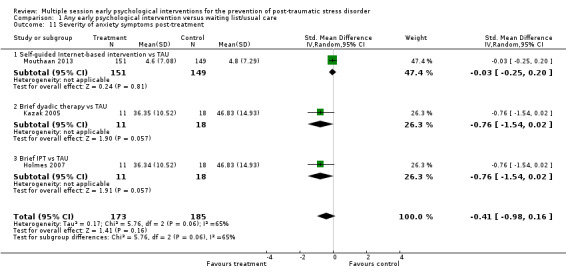

Five studies reported data on severity of depressive symptoms post‐treatment (Holmes 2007; Mouthaan 2013; Rothbaum 2012; Ryding 2004; Zatzick 2001). Meta‐analysis indicated a lack of evidence of difference between multiple session early psychological interventions and treatment as usual at postintervention (SMD –0.19, 95% CI –0.40 to 0.01; I2 = 35%; studies = 5; participants = 671; Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any early psychological intervention versus waiting list/usual care, Outcome 8 Severity of depressive symptoms post‐treatment.

When analysed by type of intervention, evidence from one study (137 participants) indicated that brief individual trauma processing therapy may be more effective than treatment as usual (SMD –0.46, 95% CI –0.80 to –0.12). There was a lack of evidence of a difference between treatment as usual and self‐guided Internet‐based CBT (SMD –0.17, 95% CI –0.39 to 0.06; studies = 1; participants = 300), group therapy (SMD –0.22, 95% CI –0.55 to 0.10; studies = 1; participants = 147). There were very wide confidence intervals when comparing treatment as usual with collaborative care (SMD –0.26, 95% CI –0.99 to 0.48; studies = 1; participants = 29), or brief IPT (SMD 0.32, 95% CI –0.20 to 0.84; studies = 1; participants = 58).

One study measured severity of depression using the PHQ‐9 (Biggs 2016). Data were not in a usable format for meta‐analysis. Authors reported that the severity of PTSD symptoms did not differ significantly between the intervention and control group at one or two months' post‐treatment.

Three to six months' follow‐up

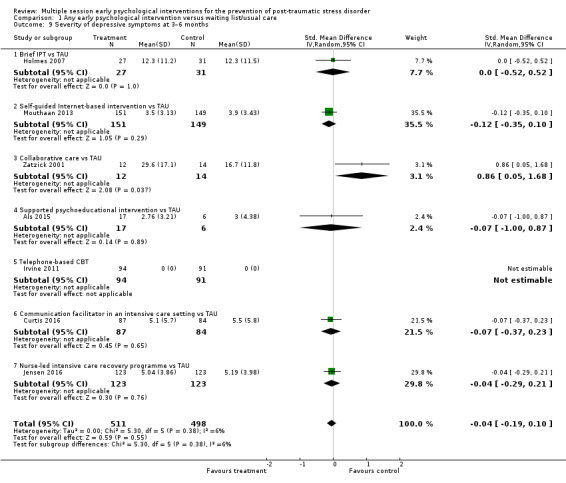

Seven studies reported data on severity of depressive symptoms at three to six months' follow‐up (Als 2015; Curtis 2016; Holmes 2007; Irvine 2011; Jensen 2016; Mouthaan 2013; Zatzick 2001). Meta‐analysis indicated no difference between multiple session early psychological interventions and treatment as usual (SMD –0.04, 95% CI –0.19 to 0.10; I2 = 6%; studies = 7; participants = 1009; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any early psychological intervention versus waiting list/usual care, Outcome 9 Severity of depressive symptoms at 3–6 months.

When analysed by type of intervention, there was no statistically significant difference between any specific intervention and treatment as usual.

One study measured depression at six months (Andre 1997). However, SDs were not reported and the study could not be entered in the meta‐analysis. Authors reported that the mean change in HAD score was 3.2 in the intervention group and 3.3 in the control group. There was a large loss to follow‐up in this study; data were only available for 39/65 participants in the intervention group and 45/67 in the control group.

One study measured severity of depression using the PHQ‐9 (Biggs 2016). Data were not in a usable format for meta‐analysis. Authors reported that the severity of PTSD symptoms did not differ significantly between the intervention and control groups at three or four months' post‐treatment.

Seven to 12 months' follow‐up

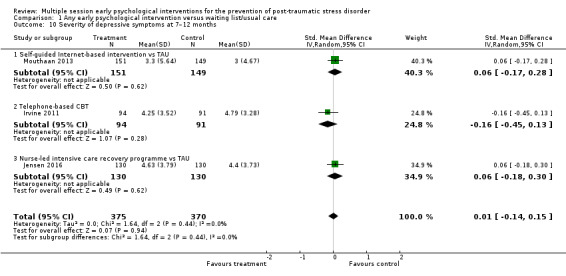

Three studies reported data on severity of depressive symptoms at seven to 12 months' follow‐up (Irvine 2011; Jensen 2016; Mouthaan 2013). Meta‐analysis indicated no evidence of difference between multiple session early psychological interventions and treatment as usual (SMD 0.01, 95% CI –0.14 to 0.15; I2 = 0%; studies = 3; participants = 745; Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any early psychological intervention versus waiting list/usual care, Outcome 10 Severity of depressive symptoms at 7–12 months.

When analysed by type of intervention, there was no difference between any specific intervention and treatment as usual.

One study measured severity of depression at 12 months' follow‐up (Wang 2015). Authors did not report SDs and, therefore, it could not be used in a meta‐analysis. The mean change in depression according to HADS was 3.29 in the treatment and 3.15 in the control group (P = 0.64).