Abstract

The bulk photovoltaic effect (BPVE) rectifies light into the dc current in a single-phase material and attracts the interest to design high-efficiency solar cells beyond the pn junction paradigm. Because it is a hot electron effect, the BPVE surpasses the thermodynamic Shockley–Queisser limit to generate above-band-gap photovoltage. While the guiding principle for BPVE materials is to break the crystal centrosymmetry, here we propose a magnetic photogalvanic effect (MPGE) that introduces the magnetism as a key ingredient and induces a giant BPVE. The MPGE emerges from the magnetism-induced asymmetry of the carrier velocity in the band structure. We demonstrate the MPGE in a layered magnetic insulator CrI3, with much larger photoconductivity than any previously reported results. The photocurrent can be reversed and switched by controllable magnetic transitions. Our work paves a pathway to search for magnetic photovoltaic materials and to design switchable devices combining magnetic, electronic, and optical functionalities.

Subject terms: Electronic properties and materials, Nonlinear optics

Two dimensional (2D) material with intriguing physical properties promises advanced electronic and spintronic technologies. Here the authors predict a magnetic photo-galvanic effect (MPGE) in bilayer 2D CrI3 due to the magnetism-induced asymmetry of the carrier velocity in the band-structure topology.

Introduction

Under strong light irradiation, a homogeneous non-centrosymmetric material can rectify light into a dc current, called the bulk photovoltaic effect (BPVE)1–7. The induced open-circuit voltages can be much larger than the band gap. Thus, the BPVE displayed a promising potential in the solar energy conversion in ferroelectric perovskites8–10 and triggered the interest for the application of solar cells11 beyond the p–n junction design and more recently also the application of photodetectors12. It is believed that the shift current is dominant mechanism for the BPVE2,4,13. Shift current refers to real-space shift of conduction and valence Bloch electrons upon photoexcitation by a topological quantity, the Berry phase14. Therefore, ferroelectrics that exhibit intrinsic charge polarization are a promising direction in the search of BPVE materials. Furthermore, topological Weyl semimetals15,16 have recently been investigated for promising BPVE17–23, due to the large Berry phase in the band structure.

The essential requirement of the BPVE is inversion symmetry () breaking. Thus, the present guiding principle to design BPVE materials is to break the crystal centrosymmetry and sometimes to induce a strong charge polarization24–27. The lattice asymmetry or the polarization, however, is not the necessary condition for the inversion symmetry breaking. In this work, we show a large photogalvanic effect by a magnetic ordering which breaks P but preserves the parity-time symmetry (, where represents the time-reversal symmetry); therefore, no polarization exists. This phenomenon, called magnetic photogalvanic effect (MPGE), can generate a photocurrent even upon the linearly polarized light. But it cannot be described by the shift current that applies to non-magnetic systems. The MPGE is an intrinsic current response from the band-structure topology and distinct from the previously reported spin-galvanic effect28 and magneto-gyrotropic photogalvanic effects29 in semiconductor quantum wells (see ref. 30 for review), which are driven by an external magnetic field, and also the spin BPVE that generates a spin current31,32.

The light excitation is known to generate an electron and hole pair in the solid. The velocity difference between the excited electron and hole may lead to a dc current. However, such a current usually vanishes because the velocity reverses its direction from k to −k in the momentum space. Such a symmetry in the band structure (see Fig. 1) is induced by either or . So we can realize this photocurrent by breaking both and to avoid the velocity cancellation in the band structure, which is the core of the MPGE proposed.

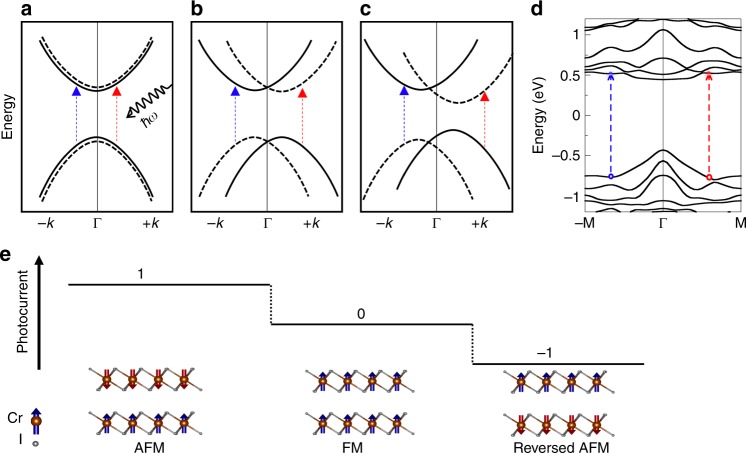

Fig. 1.

Band structure symmetry-breaking and magnetic structures of the bilayer CrI3. Schematics of band structures a with both inversion symmetry () and the time-reversal symmetry (), b with only but -breaking, and c with both - and -breaking. For both a, b, the light excitation (ħω) at +k and −k is symmetric to each other. However, such a symmetry is broken in c. As a consequence, excited electrons at +k and −k do not cancel each other in velocity, giving rise to a dc photocurrent. d The band structure of antiferromagnetic(AFM) bilayer CrI3. Here both - and are broken as the case of (c), violating the k to −k symmetry. The spin-orbit coupling is included. The Fermi energy is shifted to zero. e The AFM, ferromagnetic (FM) and reversed AFM phases display three distinct responses to a linearly polarized light – positive current state(1), zero current state (0) and negative current state(−1)

We demonstrate the MPGE in a newly discovered two-dimensional ferromagnetic insulator, CrI333,34. In the antiferromagnetic (AFM) phase of a CrI3 bilayer33,35, both and are broken while the combined symmetry is preserved. We find that a giant dc photocurrent emerges in the visible-light window. Because the symmetry forces the Berry phase to vanish, such a photocurrent is distinct from the shift current. The photoconductivity is sourced from the resonant optical transition in the asymmetric band structure. We found that the spin-orbit coupling (SOC) determines the extent of the momentum-inversion symmetry breaking and thus scales the amplitude of MPGE. The magnetic phase transition, which is controllable as demonstrated in recent experiments35–39, can be utilized to control the direction and amplitude of the induced current. When reversing all spins in the AFM phase, we can switch the current direction. When switching from the AFM phase to the ferromagnetic (FM) phase, we can completely turn off the current by recovering the spatial inversion. Therefore, we realize three states with different light-matter responses—positive, zero, and negative currents (as illustrated in Fig. 1e). Thus, the MPGE provides a new pathway to control the light-matter interaction by magnetism and to design optical storage/switch devices. Our findings can be generalized to multilayers, the bulk system, and other magnetic materials.

Results

Symmetry of 2D magnetic insulator CrI3

The recent discovery of 2D van der Waals magnetic insulators, such as CrI3, brings fascinating opportunities to design 2D magnetic devices. Bulk CrI3 is an FM insulator34. The FM coupling is preserved down to the monolayer limit33,40. In the bilayer and few-layer thickness, the interlayer coupling can be switched between AFM and FM by either an external magnetic field37 or electric gating36,38, giving rise to a giant magnetoresistance effect35,39. The atomic crystal of CrI3 exhibits inversion symmetry with two inversion centers, one inside the monolayer and the other in between neighboring monolayers. The AFM order reduces the crystal symmetry by removing the interlayer inversion center. Therefore, an AFM bilayer breaks the inversion symmetry, although an FM bilayer does not. Another important feature is that the AFM ordered phase preserves symmetry while it breaks and independently; hence, no polarization exists in the ordered phase. Therefore, the bilayer CrI3 (see Fig. 1) is an ideal system to examine the photocurrent response, where the inversion symmetry is solely broken by the AFM order instead of the crystal structure. In the following, the symmetry is found to be crucial to determine the mechanism of the photocurrent response.

We show the band structures of the bilayer calculated by the density-functional theory (DFT) including the spin-orbit coupling (SOC) in Fig. 1. All bands are doubly degenerate, which is protected by the symmetry in the AFM phase. In contrast, such degeneracy is lifted in the FM phase (Supplementary Fig. 1). For the AFM phase, an important feature is the breaking of the k to −k symmetry. In a simple consequence, excited electrons (holes) at k and −k by the optical excitation (ħω) exhibit uncompensated velocities and lead to a nonzero dc current. In addition, the energy gap is slightly lower than the experimental value, which can be attributed to the known gap underestimation of DFT.

Photocurrent of bilayer CrI3

In general, the photocurrent is a nonlinear effect. In this work, we provide a proper formalism (Equation (2)) to describe -breaking photocurrent by the second-order response theory (see Sec.2). We first evaluate the photocurrent response of the bilayer CrI3 using the general formalism based on Bloch wave functions of the realistic material. Then we prove that this formalism can be reduced to a simple form of the resonant optical transition (Equation (6)) in the presence of the symmetry.

Under the irridation of the linearly polarized light, the FM bilayer exhibits vanishing photocurrent due to inversion symmetry. However, the AFM phase displays a large photocurrent conductivity (more than 200 μAV−2 for a relaxation time τ ≈ 0.4 ps, i.e., ħ/τ = 1 meV) in the visible-light range (see Fig. 2). This value is higher than that of many known BPVE materials reported so far6,24,26,41–46. We note that the value of the photocurrent is proportional to the relaxation time (see Supplementary Fig. 3). Here we choose the τ value according to the magnitude of experimental reports on other transition metal dichalcogenides47,48. We note that the photocurrent reverses its direction when reversing all spins in the AFM phase. Therefore, the FM, AFM, and reversed AFM represent three photocurrent states, 0 (no current), 1 (positive current), and −1 (negative current), respectively, as illustrated in Fig. 1. In addition, for circularly polarized light, we do not observe any photocurrent for both AFM and FM bilayers, which is constrained by the 2D point group symmetry.

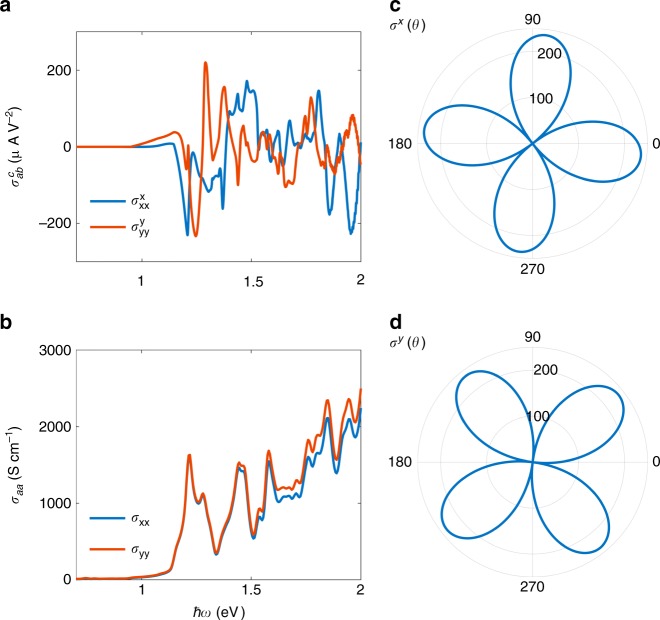

Fig. 2.

Calculated photoconductivity in response to the linearly polarized light. a The photon energy (ħω) dependence of and . b The linear-response optical conductivity σxx and σyy. c, d The angle dependent photoconductivity σx(θ),σy(θ) [cf. Eq. (3)] in the same unit as a for ħω = 1.2 eV and ħ/τ = 1 meV. x and y are the directions of the current and θ is the angle between the electric field of light and the x-axis

Discussion

We describe the BPVE response by the general second-order Kubo formalism2 and then drive the MPGE in the condition of -breaking. The general theory accounts for the steady-state short-circuit photocurrent with the relaxation time approximation. The conductivity (a, b, c = x, y in 2D) represents the photocurrent Jc generated by the dipole electrical field of light, E = (Ea(ω), Eb(ω), 0),

| 1 |

| 2 |

where , is the velocity operator, τ is the relaxation time, d is the system dimension, fln = f(El) − f(En), f(En) is the Fermi-Dirac distribution, Enm = En − Em, En ≡ En(k), and |n, k〉 are energy and wave functions, respectively, at k for the nth band.

The photocurrent conductivity matrix is shaped by the symmetry of the AFM bilayer. The three-fold rotational symmetry and lead to only six nonzero tensor elements, and . Here only two of them (such as and ) are independent, since x and y directions are not equivalent in a hexagonal lattice. For a linearly polarized light E = (cosθ, sinθ, 0)E0cos(ωt), according to Eq. (1) the photocurrent along the x and y direction is

| 3 |

The photocurrent is sensitive to the polarization direction θ, as we show in Fig. 2c, d. Following Eq. (3), if is zero, the maxima of σx(θ) is located at θ = 0, 180°. Because is generically nonzero at a given frequency; however, the maxima of σx shift away from θ = 0, 180° in Fig. 2c. Such an anisotropy is usually measured to deduce the conductivity tensor elements in experiment.

In contrast, for the circularly polarized light, the photocurrent is forced to vanish by the 2D point group symmetry (C3) despite that it may appear in a 3D material. In other words, = = = for a circular polarized light with Ey = iEx. Such a dramatic distinction between light polarization provides a simple, useful hallmark to verify these results on 2D materials. We will focus our discussions mainly on the linearly polarized light in the following.

The general formalism (Equation second-kubo) can be simplified when special symmetries appear. The BPVE arises as a consequence of the three-band (l, m, n) interference in the optical excitation. (i) The response function vanishes to zero if the inversion exists, because the numerator , the product of three matrix elements, is odd to k. (ii) If is broken but appears, Nlmn(k) = −Nlmn(−k)*. Then only the imaginary part of Nlmn(k) contributes nonzero values to the photocurrent. Therefore, the linearly and circularly polarized lights are related to the imaginary and real parts of the energy denominator, respectively, in Eq. (2). For a -symmetric insulator, Eq. (2) can be simplified to the shift current and injection-current formalisms2,4,49 for the linearly and circularly polarized lights, respectively. In non-magnetic systems, this implies that the circular photocurrent scales linearly with the scattering rate, while the linear photocurrent is independent of the scattering rate. Here, the velocity matrix is commonly transformed to the length gauge49.

For the bilayer AFM CrI3 that respects but breaks and independently, the response function exhibits a unique symmetry. Because requires , the numerator [] in Eq. (2) is always real, where l′, m′, n′ are partners (degenerate in energy) of l, m, n, respectively. Therefore, the linearly and circularly polarized lights are related to the real and imaginary parts of the energy denominator, respectively, opposite to the -symmetric case.

To establish the intuitive correlation between the band structure and the BPVE, we decompose Eq. (2) into two-band and three-band process2,21. The former corresponds to a direct resonant transition from |l〉 to |n〉, where n = m. By considering (En − Em − iħ/τ)−1 = −iτ/ħ in Eq. (2), the response function can be derived,

| 4 |

where and the δ-function is derived from the imaginary part of (Enl − ħΩ − iħ/τ)−1. Such two-band photocurrent is proportional to the relaxation time τ and decided by the resonant transition according the selection rule Enl = ±ħω. We further transform Eq. (4) to the length gauge,

| 5 |

where is the position matrix element and if Enl − ħΩ = 0, and . This formula is very similar to the the known -symmetric injection-current expression(Equation (56) in ref. 4), except that in ref. 4 the injection current is integrated over the imaginary part of the position matrix due to . In contrast, Eq. (5) evaluates its real part due to . Suppose a linearly polarized light with the polarization along x, Eq. (5) looks more intuitive in the following form,

| 6 |

It represents an excitation from l to n with dipole transition rate . The excited electron (hole) with finite velocity () induces a dc current. If at k and −k cancel each other exactly when or exists, the photocurrent from Eq. (5) or (6) vanishes. Only when both and are broken, a nonzero photocurrent may exist.

The three-band contribution refers to n ≠ m. We can exclude a trivial case that |n〉 and |m〉 are degenerate in energy for example protected by , because if so. When En ≠ Em, the real part of the denominator in Eq. (2) is τ-independent. Thus the three-band process generates a photocurrent that is robust against scattering, different from the two-band transition. The three-band process evaluate (Enm − iħ/τ)−1 in the denominator. Thus, the ratio between the three-band and two-band contributions are (ħ/τ)/Enm that is usually in the order of meV/eV. Then the three-band contribution is much smaller than the two-band one. In calculations, we indeed find that the photoconductivity is predominantly produced by the two-band transition (the three-band contribution is less than 0.5%, See the supplementary Fig. 2).

It is useful to find a simple indicator for the nonlinear photoconductivity. Because the photocurrent is proportional to the resonant transition rate, the imaginary dielectric function or the optical conductivity may provide such an indicator. In other words, the optical conductivity is the sum of all allowed transitions equally while the photoconductivity is to sum them with the velocity weight (see Eq. (6)). As shown in Fig. 2c, the optical conductivity σxx is strongly correlated to . In addition, the photoconductivity indeed scales linearly to the relaxation time τ in our calculations (Supplementary Fig. 3).

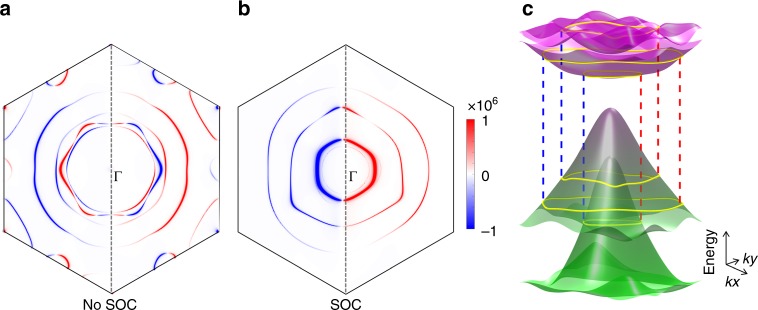

Figure 3 shows the distribution in the momentum space for the AFM bilayer at ħω = 1.2 eV. It is clear that the photoconductivity is contributed by resonant transition channels between the valence and conduction bands. Because of the breaking of both and , these channels are not symmetric between k and −k anymore. We point out that SOC play a significant role here despite that it is less obvious from Eq. (6). The strength of SOC represents the amount of the k to −k symmetry breaking in the band structure. When SOC is absent, the AFM band structure is still symmetric (see the supplementary Fig. 1). This is because of the spin rotation symmetry SU(2). Therefore, the net photocurrent vanishes, as shown in Fig. 3a. Finite SOC locks the the spin orientation with respect to the lattice and breaks the momentum-inversion symmetry (see Fig. 3b), resulting in a nonzero photocurrent. The SOC modifies the band structure by opening a gap at the band crossing points. So peaks of usually correspond to the transitions involving these anti-crossing gap regions.

Fig. 3.

a, b Distribution of the photoconductivity in the first Brillouin zone. Without including the spin-orbit coupling (SOC), the k to −k symmetry appears while finite SOC breaks such a symmetry. The ring-like shape indicates the resonant optical transition between valence (El) and conduction (En) bands by the selection rule En − El = ħω (1.2 eV). c Transitions from top two valence bands to the bottom two conduction bands. The yellow rings indicate the transition paths and correspond to the large--amplitude rings in (b)

In reality, the substrate or the gate may modify the bilayer electronic structure by breaking the crystal inversion between two layers. It is practical to investigate how robust the -symmetry-induced photocurrent behaves in the presence of such perturbation. We apply an out-of-plane electric field E to represent the perturbation. E induces a potential drop between two layers and breaks the symmetry of the bilayer. We calculate the photoconductivity using Eq. (2), where both the real and imaginary parts of Nlmn(k) contribute. The photoconductivity remains relatively robust even for a large E = 0.005 V/a.u. (1 a.u. = 0.53 Å) for the AFM bilayer (see the Supplementary Fig. 4). On the other hand, the FM phase starts to exhibit nonzero photocurrent when E breaks its inversion symmetry. At E = 0.005 V/a.u., the photoconductivity is of the same order as in the AFM case.

In addition, the MPGE can be easily generalized to multilayers and other magnetic materials (such as Cr2Ge2Te650 and VSe251). Some magnetic orders of a trilayer CrI3, for example, ↑↑↓ or ↑↓↓, can break the inversion symmetry and generate the MPGE. Different from a bilayer, is broken here. Then the real and imaginary parts of Nlmn(k) contribute to the photoconductivity in Eq. (2). Magnetic orders such as ↑↑↑ and ↑↓↑ preserve the inversion symmetry and produce no photocurrent. Further, hetero-structures of layered materials and twisted layers provide vast possibilities. Beyond 2D materials, the MPGE may also exist in 3D systems, specially AFM materials with the symmetry and strong SOC, such as Cr2O352, Mn2Au53, and CuMnAs54,55.

To summarize, we discover a magnetic photogalvanic effect to generate the photocurrent by breaking the momentum-inversion symmetry in the band structure. This mechanism induces a large photoconductivity in the AFM phase of the bilayer CrI3 despite no electric polarization. The photocurrent appears for the linearly polarized light but vanishes for the circularly polarized one in the 2D system. It exhibits an injection-current-like feature and is proportional to the relaxation time, the resonant transition rate and SOC. Tuning the magnetic structure is a sensitive handle to manipulate the photocurrent. Although the bilayer CrI3 exhibits a record photoconductivity, it seems possible to design even better nonlinear magnetic materials, for example by considering stronger SOC and longer relaxation time. There are plenty of AFM and FM materials, such as magnetoelectric multiferroic compounds56,57, waiting for exploration.

Methods

We obtain the DFT band structure and Bloch wave functions from the Full-Potential Local-Orbital program (FPLO)58 within the generalized gradient approximation59. By projecting the Bloch wave functions onto atomic-like (Cr-d and I-sp) Wannier functions, we obtain a tight-binding Hamiltonian with sixty-eight bands that well reproduce the DFT band structure. We employ this material specific tight-binding Hamiltonian for accurate evaluation of the photocurrent. We use ħ/τ = 1 meV in our calculations. For the integrals of Eq. 1b, the 2D Brillouin zone was sampled by a grid of 400 × 400. Increasing the grid size to 960 × 960 varied the conductivity by less than 5%.The spin-orbit coupling was included in a self-conssistent way for the DFT calculations. The FPLO band structure is well consistent with other DFT methods.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Liang Wu, Markus Mittnenzweig, Adolfo G. Grushin, and Liang Fu for helpful discussions. N.N. was supported by JST CREST Grant Number JPMJCR1874 and JPMJCR16F1, Japan, and JSPS KAKENHI Grant numbers 18H03676 and 26103006. H.I. was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP18H04222, JP19K14649, and JP18H03676. C.F. was funded by the DFG through SFB 1143 (project ID 247310070) and thanks the Wuerzburg-Dresden Cluster of Excellence on Complexity and Topology in Quantum Matter - ct.qmat (EXC 2147, project ID 39085490). B.Y. acknowledges the financial support by the Willner Family Leadership Institute for the Weizmann Institute of Science, the Benoziyo Endowment Fund for the Advancement of Science, Ruth and Herman Albert Scholars Program for New Scientists, the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 815869) and by the collaborative Max Planck Lab on Topological Materials.

Author contributions

B.Y. conceived the project. Y.Z. did the DFT and photocurrent calculations. Y.Z. and B.Y. performed the derivation of photocurrent response. Y.Z., T.H., F.d.J., H.I., and B.Y. analyzed the results. Y.Z. and B.Y. wrote the manuscript with the input from all other authors. N.N., C.F., and B.Y. supervised the project.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-11832-3.

References

- 1.Belinicher VI, Sturman BI. The photogalvanic effect in media lacking a center of symmetry. Sov. Phys. Usp. 1980;23:199–223. doi: 10.1070/PU1980v023n03ABEH004703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Baltz R, Kraut W. Theory of the bulk photovoltaic effect in pure crystals. Phys. Rev. B. 1981;23:5590. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.23.5590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sturman, P. J. Photovoltaic and Photo-refractive Effects in Noncentrosymmetric Materials, volume 8. (CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, 1992).

- 4.Sipe JE, Shkrebtii AI. Second-order optical response in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B. 2000;61:5337–5352. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.61.5337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fridkin VM. Bulk photovoltaic effect in noncentrosymmetric crystals. Crystallogr. Rep. 2001;46:654–658. doi: 10.1134/1.1387133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young SM, Rappe AM. First principles calculation of the shift current photovoltaic effect in ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;109:116601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.116601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morimoto T, Nagaosa N. Topological nature of nonlinear optical effects in solids. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1501524. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi T, Lee S, Choi YJ, Kiryukhin V, Cheong S-W. Switchable ferroelectric diode and photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3. Science. 2009;324(April):63–66. doi: 10.1126/science.1168636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang SY, et al. Above-bandgap voltages from ferroelectric photovoltaic devices. Nat. Nanotech. 2010;5:143–147. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grinberg I, et al. Perovskite oxides for visible-light-absorbing ferroelectric and photovoltaic materials. Nature. 2013;503:509–512. doi: 10.1038/nature12622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spanier JE, et al. Power conversion efficiency exceeding the Shockley–Queisser limit in a ferroelectric insulator. Nat. Photonics 2018 12:2. 2016;10:611–616. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daranciang D, et al. Ultrafast photovoltaic response in ferroelectric nanolayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;108:087601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.087601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan LZ, et al. Shift current bulk photovoltaic effect in polar materials—hybrid and oxide perovskites and beyond. NPJ Comput. Mater. 2016;2:16026. doi: 10.1038/npjcompumats.2016.26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao D, Chang M-C, Niu Q. Berry phase effects on electronic properties. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010;82:1959–2007. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.82.1959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan B, Felser C. Topological materials: Weyl semimetals. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2017;8:337–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-031016-025458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armitage, N. P., Mele, E. J. & Vishwanath, A. Weyl and Dirac semimetals in three dimensional solids. Reviews of Modern Physics, 90, 015001 (2018).

- 17.Wu L, et al. Giant anisotropic nonlinear optical response in transition metal monopnictide Weyl semimetals. Nat. Phys. 2016;13:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nphys3969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma Q, et al. Direct optical detection of weyl fermion chirality in a topological semimetal. Nat. Phys. 2017;13:842. doi: 10.1038/nphys4146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan C-K, Lindner NH, Refael G, Lee PA. Photocurrents in weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B. 2017;95:041104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.95.041104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Juan F, Grushin AG, Morimoto T, Moore JE. Quantized circular photogalvanic effect in weyl semimetals. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15995. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, et al. Photogalvanic effect in Weyl semimetals from first principles. Phys. Rev. B. 2018;97:241118(R). doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.97.241118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Sun Y, Yan B. Berry curvature dipole in Weyl semimetal materials: an ab initio study. Phys. Rev. B. 2018;97:041101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.97.041101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osterhoudt, G. B. et al. Colossal photovoltaic effect driven by the singular berry curvature in a weyl semimetal. arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.04951 (2017).

- 24.Cook AM, Fregoso BM, De Juan F, Coh S, Moore JE. Design principles for shift current photovoltaics. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14176. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura M, et al. Shift current photovoltaic effect in a ferroelectric charge-transfer complex. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:281. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00250-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rangel T, et al. Large bulk photovoltaic effect and spontaneous polarization of single-layer monochalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017;119:067402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.067402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang M-M, Kim DJ, Alexe M. Flexo-photovoltaic effect. Science. 2018;360:904–907. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ganichev SD, et al. Spin-galvanic effect. Nature. 2002;417:153–156. doi: 10.1038/417153a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ganichev SD, et al. Zero-bias spin separation. Nat. Phys. 2006;2:609–613. doi: 10.1038/nphys390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bel’kov VV, Ganichev SD. Magneto-gyrotropic effects in semiconductor quantum wells. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2008;23:114003–114011. doi: 10.1088/0268-1242/23/11/114003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganichev SD, et al. Conversion of spin into directed electric current in quantum wells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;86:4358–4361. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young SM, Zheng F, Rappe AM. Prediction of a linear spin bulk photovoltaic effect in antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013;110:057201. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.057201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang B, et al. Layer-dependent ferromagnetism in a van der Waals crystal down to the monolayer limit. Nature. 2017;546:270. doi: 10.1038/nature22391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGuire MA, Dixit H, Cooper VR, Sales BC. Coupling of crystal structure and magnetism in the layered, ferromagnetic insulator cri3. Chem. Mater. 2015;27:612–620. doi: 10.1021/cm504242t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song T, et al. Giant tunneling magnetoresistance in spin-filter van der waals heterostructures. Science. 2018;360:1214–1218. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang S, Shan J, Mak KF. Electric-field switching of two-dimensional van der Waals magnets. Nat. Mater. 2018;17(May):406–410. doi: 10.1038/s41563-018-0040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klein DR, et al. Probing magnetism in 2d van der waals crystalline insulators via electron tunneling. Science. 2018;360:1218–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang S, Li L, Wang Z, Mak KF, Shan J. Controlling magnetism in 2D CrI3 by electrostatic doping. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018;13:1. doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Z, et al. Very large tunneling magnetoresistance in layered magnetic semiconductor CrI3. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2516. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04953-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seyler KL, et al. Ligand-field helical luminescence in a 2D ferromagnetic insulator. Nat. Phys. 2018;14(March):277–281. doi: 10.1038/s41567-017-0006-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young SM, Zheng F, Rappe AM. First-principles calculation of the bulk photovoltaic effect in bismuth ferrite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;109(Dec):236601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.236601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng F, Takenaka H, Wang F, Koocher NZ, Rappe AM. First-principles calculation of the bulk photovoltaic effect in CH3NH3PbI3 and CH3NH3PbI3−xClx. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014;6:31–37. doi: 10.1021/jz502109e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brehm JA, Young SM, Zheng F, Rappe AM. First-principles calculation of the bulk photovoltaic effect in the polar compounds LiAsS2, LiAsSe2, and NaAsSe2. J. Chem. Phys. 2014;141:204704. doi: 10.1063/1.4901433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sotome M, et al. Spectral dynamics of shift current in ferroelectric semiconductor SbSI. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:1929–1933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1802427116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fei, R., Tan, L. Z. & Rappe, A. M. Shift current bulk photovoltaic effect influenced by quasiparticles and excitons. arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.05287. https://arxiv.org/abs/1811.05287 (2018).

- 46.Chan, Y. H., Qiu, D. Y., da Jornada, F. H. & Louie, S. G. Exciton shift currents: DC conduction with sub-bandgap photo excitations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.12813. https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.12813 (2019).

- 47.Kozawa D, et al. Photocarrier relaxation pathway in two-dimensional semiconducting transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4543. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sohier T, Campi D, Marzari N, Gibertini M. Mobility of two-dimensional materials from first principles in an accurate and automated framework. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2018;2:114010. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.2.114010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aversa C, Sipe JE. Nonlinear optical susceptibilities of semiconductors: results with a length-gauge analysis. Phys. Rev. B. 1995;52:14636. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.52.14636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gong C, et al. Discovery of intrinsic ferromagnetism in two-dimensional van der Waals crystals. Nature. 2017;546:265–269. doi: 10.1038/nature22060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bonilla M, et al. Strong room-temperature ferromagnetism in VSe2 monolayers on van der Waals substrates. Nat. Nanotech. 2018;13(April):289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fiebig M, Fröhlich D, Krichevtsov BB, Pisarev RV. Second harmonic generation and magnetic-dipole-electric-dipole interference in antiferromagnetic Cr2O3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994;73:2127–2130. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barthem VMTS, Colin CV, Mayaffre H, Julien MH, Givord D. Revealing the properties of Mn2Au for antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2892. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olejnik K, et al. Antiferromagnetic CuMnAs multi-level memory cell with microelectronic compatibility. Nat. Commun. 2017;8(May):15434. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emmanouilidou E, et al. Magnetic order induces symmetry breaking in the single-crystalline orthorhombic CuMnAs semimetal. Phys. Rev. B. 2017;96:224405. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.96.224405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fiebig M. Revival of the magnetoelectric effect. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2005;38:R123. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/38/8/R01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spaldin NA, Fiebig M. The renaissance of magnetoelectric multiferroics. Science. 2005;309:391–392. doi: 10.1126/science.1113357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koepernik K, Eschrig H. Full-potential nonorthogonal local-orbital minimum-basis band-structure scheme. Phys. Rev. B. 1999;59:1743. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.