Abstract

We introduce a novel approach to model heat transport in solids, based on the Green-Kubo theory of linear response. It naturally bridges the Boltzmann kinetic approach in crystals and the Allen-Feldman model in glasses, leveraging interatomic force constants and normal-mode linewidths computed at mechanical equilibrium. At variance with molecular dynamics, our approach naturally and easily accounts for quantum mechanical effects in energy transport. Our methodology is carefully validated against results for crystalline and amorphous silicon from equilibrium molecular dynamics and, in the former case, from the Boltzmann transport equation.

Subject terms: Electronic properties and materials, Computational methods

Heat transport is a key process in designing functional materials, yet its calculations remain challenging due to large variance in material structures. Isaeva et al. introduce a unified approach counting the quantum effects, which is capable of modeling heat transport ranging from crystals to glasses.

Introduction

Heat transport in solid insulators, either crystalline or disordered, is dominated by the dynamics of lattice vibrations. Far from melting, atomic displacements from equilibrium are much smaller than interatomic distances and they can thus be treated in the (quasi-) harmonic approximation. In crystals, this observation enables a kinetic description of heat transport in terms of phonons, that can be embodied in the Peierls–Boltzmann transport equation (BTE)1,2. In disordered systems the typical phonon mean free paths may be so short that the quasi-particle picture of heat carriers breaks down and BTE is no longer applicable, making it necessary to resort to molecular dynamics (MD), in either its nonequilibrium or equilibrium (EMD) flavors2,3. MD is of general applicability to solids, either periodic or disordered, and liquids. Yet, it may require long simulation times and it is subject to statistical errors, which are at times cumbersome to evaluate especially for systems at low temperatures, where lack of ergodicity may be an issue. Most importantly, MD cannot account for quantum-mechanical effects4, which are instead easily treated in BTE, thus making the treatment of heat transport for glasses in the quantum regime, i.e. below the Debye temperature, a methodological challenge.

In this paper, we present a novel approach to heat transport in insulating solids, which combines the Green–Kubo (GK) theory of linear response3,5–8 and a quasi-harmonic description of lattice vibrations, thus resulting in a compact expression for the thermal conductivity, that unifies the BTE approach in the single-mode relaxation-time approximation (RTA) for crystals2 and a generalization of the Allen-Feldman (AF) model for disordered system9,10 that explicitly and naturally accounts for normal-mode lifetimes. The main ingredients of our approach are the matrix of the inter-atomic force constants (IFC) computed at mechanical equilibrium and the anharmonic lifetimes of the vibrational modes, as computed from the cubic corrections to the harmonic IFCs using the Fermi’s golden rule11. Our theory is thoroughly validated in crystalline and amorphous silicon by comparing its predictions with those of EMD simulations and BTE computations.

Results

Theory

The basis of our work is the GK theory of linear response3,5–8, which relates the heat conductivity to the ensemble average of the heat-flux auto-correlation function:

| 1 |

where V and T are the system volume and temperature, kB is the Boltzmann constant, Jα(t) the α-th Cartesian component of the macroscopic heat flux, which in solids coincides with the energy flux, and 〈⋅〉 indicates a canonical average over initial conditions3. Far from melting, the energy flux and the lattice Hamiltonian of a solid, both crystalline and amorphous, can be expressed as power series in the atomic displacements, and Eq. (1) can be evaluated in terms of Gaussian integrals using standard field-theoretical techniques.

The energy flux can be expressed in terms of atomic positions, Ri, and local energies, , as (ref. 3), where in the harmonic approximation can be defined as: , Mi being the mass of i-th atom, its displacement from its equilibrium position, , α and β label Cartesian components, and is the IFC matrix. By expressing the energy flux in terms of the u’s, one obtains: , where . The second term on the right-hand side of this expression is the total time derivative of a process that, in the absence of atomic diffusion, is stationary and of finite variance. A recently established gauge invariance principle for heat transport12,13 states that such a total time derivative does not contribute to the thermal conductivity. We will therefore dispose of it and express the energy flux as: J ← J°. Note that it is essential to use equilibrium atomic positions in the definition of J°, i.e. the positions describing the (metastable) mechanical equilibrium of any given model of an ordered or disordered system, rather than instantaneous ones. Otherwise, the difference J − J° would not be a total time derivative of a stationary process and the value of the transport coefficient resulting from J° would be biased. By making use of Newton’s equation of motion, the final expression for the harmonic heat flux reads9,10:

| 2 |

where the minimum-image convention is adopted for computing inter-atomic distances in periodic boundary conditions.

By inserting Eq. (2) into Eq. (1), the integrand is cast into the canonical average of a quartic polynomial in the atomic positions and velocities. In the harmonic approximation, this average reduces to a Gaussian integral, which can be evaluated by way of the Wick’s theorem14. By doing so, the resulting time integral would diverge, thus yielding an infinite conductivity, as expected for a harmonic crystal15. In order to regularize this integral, we introduce anharmonic effects by renormalizing the single-mode correlation functions using the normal-mode lifetimes, as explained below. Our final result for the heat conductivity tensor reads:

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

where ωn and γn are the harmonic frequency and decay rate of the n-th normal mode, and is the corresponding eigenvector of the dynamical matrix, , and indicates the ratio γ/ω, which vanishes in the harmonic limit. Equations (3–5) will be dubbed as the quasi-harmonic Green-Kubo (QHGK) approximation for the heat conductivity.

In order to establish Eq. (3), we first express the energy flux in Eq. (2) in terms of normal-mode coordinates and momenta, defined as: and , reading: . It is then convenient to express these normal-mode coordinates and momenta in terms of classical complex amplitudes, reminiscent of the quantum boson ladder operators and defined as: , whose time evolution is . By doing so, the energy flux can be expressed in terms of the α amplitudes as

| 6 |

By using this expression, the integrand in Eq. (1) becomes a Gaussian integral of a fourth-order polynomial in the α’s and α*’s that, by means of the Wick’s theorem14, can be cast into a sum of products of pairs of single-mode (classical) Green’s functions, and . In the purely harmonic approximation, one would have . Anharmonic effects broaden the vibrational lines by a finite line-width, γn, which results in a finite imaginary part of the frequency and in a decay of the single-mode Green’s function, reading: . By plugging this expressions into the lengthy formula that results from applying Wick’s theorem to the integrand of Eq. (1) and performing the time integral, after some cumbersome but straightforward algebra we get Eq. (3). A full derivation of Eqs. (3–5) is presented in the Supplementary Note 1.

To lowest order in the anharmonic interactions, vibrational linewidths can be computed from the classical limit of the Fermi golden rule, = + , where nl is the Bose-Einstein occupation number of the l-th normal mode and is the third derivative of the potential energy with respect to the amplitude of the lattice distortion along the lattice normal modes11.

In order to show that our QHGK expression for the thermal conductivity, Eq. (3), reduces to the predictions of the BTE-RTA in crystals, we first notice that the vα matrices of Eq. (4) can be expressed in terms of the matrix elements of the matrices between normal-mode eigenvectors: , where the notations “(e, e′)” and “V ⋅ e” indicate scalar and matrix-vector products in the space of atomic displacements. In crystals, equilibrium atomic positions are characterized by a discrete lattice position, ai, and by an integer label, si, indicating different atomic sites within a unit cell, ds: . Likewise, in the Bloch representation, normal modes can be labeled by a quasi-discrete wavevector, q, belonging to the first Brillouin zone (BZ), and by a band index, ν: n → (qn, νn). In particular, the IFC matrix and its eigenvectors can be expressed as , where is the dynamical matrix of the system and its eigenvectors: and . When normal-mode eigenvectors are chosen to be real, the vα matrices of Eq. (4) are real and anti-symmetric. In particular, and a non-vanishing thermal conductivity results from the matrix elements of vα connecting (quasi-) degenerate normal modes, i.e. modes whose frequencies coincide within the sum of their line widths. In the Bloch representation, vα is anti-Hermitian and block-diagonal with respect to the wave-vector, q. Its diagonal elements are imaginary, though not necessarily vanishing. In this representation one has: , where . At fixed q, the vibrational spectrum is strictly discrete i.e. it remains so even in the thermodynamic limit. The number of q points for which there exists a pair of distinct modes, (q, ν) and (q, μ) with ν ≠ μ, that are degenerate within the sum of their line-widths is vanishingly small, because, in practice, this quasi-degeneracy can only occur close to high-symmetry lines. Furthemore, for such few pairs, one can prove that vνq,μq ∝ ωνq − ωμq. Hence in the periodic case the τ° matrix in Eq. (5) is strictly diagonal, , where is the anharmonic lifetime of the (q, ν) normal mode. We conclude that, for periodic systems in the Bloch representation, the double sum in Eq. (3) can be cast into a single sum over diagonal terms, reading: , where is the group velocity of the ν-th phonon branch. This is the final expression for the thermal conductivity of a crystal in QHGK, which remarkably coincides with the solution of BTE-RTA1. We tested the QHGK approach against BTE-RTA for a crystalline silicon supercell of 1728 atoms, with a lattice parameter of 5.431 Å. The two calculations, performed with different codes, give the same results, as expected by the proven equivalence of the two methods for crystalline systems (see Supplementary Fig. 1).

Moving to the quantum regime is straightforward in our approach. To this end, we start from the quantum GK formula3,5–8, reading:

| 7 |

where are quantum heat-flux operators and 〈⋅〉 indicates quantum canonical averages. A quantum expression for the heat flux is obtained from its classical counterpart, Eq. (6), by making the substitutions: and , and being normal-mode creation/annihilation operators, satisfying the standard commutation relations for bosons: . Note that no ordering ambiguities arise when quantizing Eq. (6) because the matrices are antisymmetric, and they therefore vanish for n = m. The resulting expression for the quantum heat flux is:

| 8 |

The computation of the heat conductivity proceeds exactly as in the classical case, except for the expressions for the single-mode Green’s functions. In the quantum case they read: and , being the Bose-Einstein distribution function. The final quantum-mechanical expression for the heat conductivity in the QHGK is:

| 9 |

with . For n = m this term reduces to the modal heat capacity . The other symbols are the same as in Eqs. (4) and (5) for the classical case. , in particular, is only different from zero for . Following the same derivation as for the classical case, one can prove that for periodic crystals Eq. (9) reduces to BTE-RTA. Furthermore, in the classical limit, one has limT→∞ cnn = kB and the quantum formula, Eq. (9), reduces to Eq. (3). Further details are given in Supplementary Note 2.

Simulations

We validate our QHGK approach by testing the results of Eqs. (3) and (9) against MD simulations for amorphous silicon. Interatomic interactions are modeled using the empirical bond-order Tersoff potential16, which describes well the thermal conductivity of bulk and nanostructured silicon, including a-Si9,10,17–19. We consider a 1728-atom model of a-Si, generated by MD by quenching from the melt. Several EMD simulations where then run at different temperatures, as described in SM20,21. The integral of the heat flux autocorrelation function in Eq. (1) can then be efficiently evaluated via cepstral analysis, as described in refs. 3,22, which can be enhanced by averaging over multiple trajectories at low temperature (T ≤ 300 K). Details on the data analysis procedure followed here and on the estimate of the statistical errors is given in the Supplementary Note 3. The results of these calculations are reported in Fig. 1 and exhibit a weak non-monotonic dependence on T. Performing similar MD simulations on models of increasing size (4096 and 13,824 atoms) generated with the same protocol, we have verified that size effects on κ at 300 K amount to less than 15%, which is of the same order as the variation κ among different models with the same size. The computation of the IFC matrix, normal-mode frequencies and lifetimes is described in detail in SM, where we also display the resulting dependence of lifetimes on temperature (Supplementary Fig. 2). The resulting strongly diagonally dominant form of the τ° matrices in Eq. (5) is also displayed in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Classical thermal conductivity. Comparison between the thermal conductivity of a-Si computed for a 1728-atom supercell by the classical Green–Kubo theory of linear response using either our QHGK approach (Eq. (3), green) or equilibrium molecular dynamics (purple). The vertical bars indicate statistical errors obtained by means of cepstral analysis, as explained in Ref. 22. The kxx, kyy and kzz components of thermal conductivity tensor κ are averaged to obtain a value corresponding to an isotropic amorphous media

The thermal conductivity obtained by QHGK is in excellent agreement with that computed by EMD for T ≤ 600 K (Fig. 1). At higher temperatures QHGK overestimates κ, as it neglects higher-order anharmonic effects. We point out that, in spite of the formal analogies with the AF model9,10,23 and recent refinements thereof24,25, Eq. (3) entails no empirical parameters. It thus allows one to predict temperature trends dictated by anharmonic effects in good agreement with MD, without making any a priori distinction among propagating, diffusive, or localized vibrational modes. Conversely, in the AF model the temperature dependence lies only in the heat capacity term, therefore in the classical limit κ is temperature independent.

Similarly to the GK modal analysis approach26, based on classical MD, the transport character of the modes is dictated by the relative contribution from the diagonal and slightly off-diagonal terms of the matrix, weighted by (Supplementary Fig. 2). The generality of QHGK is expected to have a major impact for the study of weakly disordered systems, which are beyond the scope of applicability of approaches based on the BTE and the AF model.

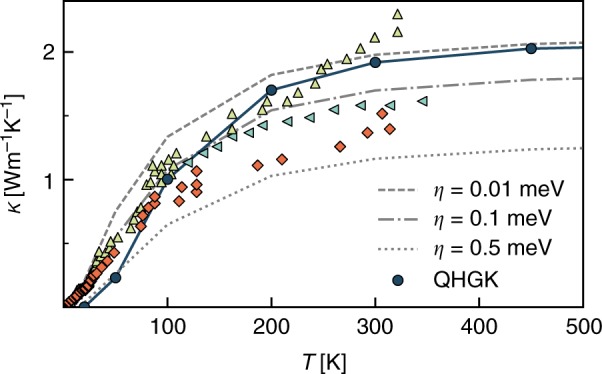

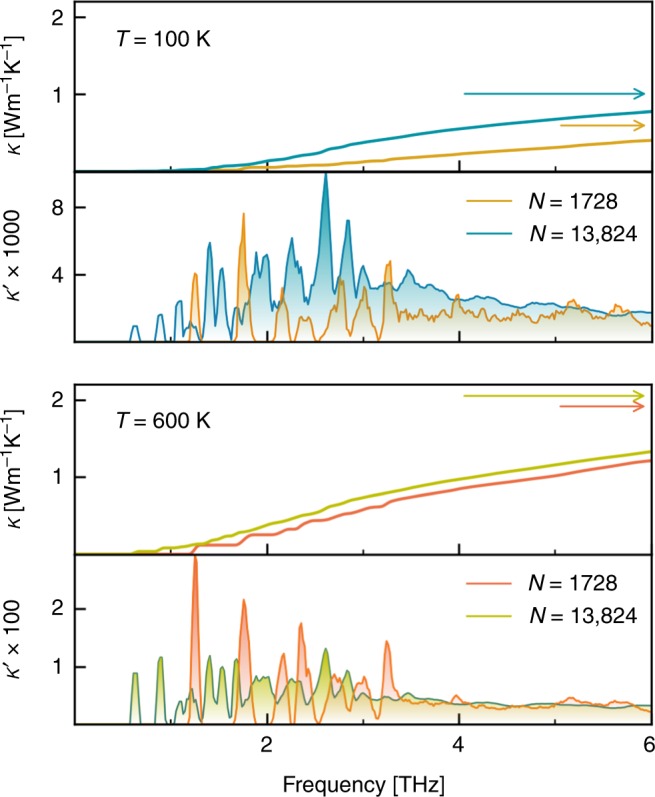

QHGK is a general theory that allows one to accurately calculate thermal transport in both crystals and glasses at a full quantum mechanical level. In Fig. 2 we report our results from quantum QHGK calculation for an amorphous Si model of 13824 atoms along with three sets of experimental data27,28. QHGK results are in excellent agreement with the measurements in Ref. 27 above 100 K. At lower temperature the estimate of κ is affected by finite size effects, related to insufficient sampling of low-frequency acoustic modes: at 25 K these effects are so important, as to make the estimated conductivity almost vanish (see below). Specifically, we see a significant improvement in the estimate of κ at 50 K from the 1728-atom model (κ = 0.027 Wm−1 K−1) to the 13824 model (κ = 0.25 Wm−1 K−1 see Fig. 3). However, at 50 K and lower temperatures the latter is not converged yet. In fact, in order to eliminate finite-size effects, in our approach it would be necessary that in any relevant frequency range the density of vibrational states is larger than the normal-mode lifetimes, so that as many quasi-discrete normal modes as possible fall withing a line-width. In the low-frequency region, which is the most populated one in the quantum regime, this condition is hindered by the vanishing of both the density of states per unit volume and normal-mode line-widths. This effect is showcased in Fig. 3, where we compare for different temperatures and model sizes the frequency-resolved differential conductivity,

| 10 |

where Δ(ω) is a broadened approximation of the δ function and the other symbols have the same meaning as in Eq. (9), and the conductivity accumulation function defined as:

| 11 |

Fig. 2.

Quantum thermal conductivity. Thermal conductivity computed for a 13824-atom supercell of a-Si using the quantum QHGK approach in the quantum regime (Eq. (9)), compared with the Allen-Feldman approach9,10,23 and experimental data (yellow triangles and orange diamonds ref. 27), (green triangles ref. 28). The broadening η used in Allen-Feldman calculations is set equal for every normal mode

Fig. 3.

Thermal conductivity accumulation function. Conductivity accumulation function, κ(ω), and frequency-resolved differential conductivity, κ′(ω) (Eqs. (10) and (11)), computed for two different model sizes (N = 1,728 and N = 13,824 atoms) at temperatures T = 100 K and T = 600 K. Horizontal arrows in the upper panels indicate cumulative values of κ. κ′ is in units of WK−1 m−1 ps

The AF model can also reproduce κ for a-Si, but it is extremely sensitive to the empirical choice of the line broadening parameter (η). The impact of η on the resulting κ(T) is also shown in Fig. 2, which shows that the value of κAF varies by a factor two by varying η between 0.01 and 0.5 meV in the temperature range considered. Whatever value is chosen for η, the AF model cannot reproduce the correct κQM(T) of a-Si over the whole temperature range, in which we deem QHGK accurate (T ≤ 600 K), and it cannot give the correct decreasing trend at high temperature by construction. The predictions of the QHGK for the thermal conductivity of a-Si in the classical and fully quantum-mechanical regimes are compared in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have introduced a unified approach to compute the lattice thermal conductivity of both amorphous and crystalline systems. This quasi harmonic approach connects in a seamless fashion the AF model for disordered systems and the BTE-RTA for crystals. QHGK provides a significant improvement in generality over the Allen-Feldman model for disordered systems and is analytically proven to be equivalent to BTE for periodic systems. Classical QHGK calculations were validated against MD simulations for a-Si, and yield satisfactory agreement over a wide temperature range. Quantum QHGK can be deemed predictive at low temperature, not only for glasses and crystals but also for partially disordered systems, for which parameter-free models were up to now unavailable. Although the numerical results of this work were obtained by evaluating Eqs. (3)–(5) using equilibrium positions , second order force constants , and line-widths γn, computed at mechanical equilibrium (T = 0), it is possible to evaluate these same quantities through temperature-dependent statistical sampling approaches29–31, thus extending the reach of QHGK to systems with strong anharmonicity and high-temperature phases. The technique proposed in this work paves the way to robust calculations of heat transport in systems with any kind of structural order, including materials with point defects, extended defects and nanostructuring, without relying on any implicit knowledge of either their underlying symmetry, or the character of the vibrational modes, and without empirical parameters. While this paper was being written we learnt that conclusions similar to ours were reached by Simoncelli et al., following a different approach based on a generalization of the BTE32.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Zheyong Fan for providing the GPUMD code and helping to set up the MD simulations. This work was partially funded by the EU through the MaX Centre of Excellence for supercomputing applications (Projects No. 676598 and 824143).

Author contributions

This work was started by S.B. and jointly supervised by S.B. and D.D. Analytical work was performed mostly by L.I. Computer codes were partly developed by L.I. and partly provided by D.D. Computer simulations were run and analyzed by L.I. and G.B. The paper was jointly written by all the authors.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Computer codes are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information: Nature Communications thanks Rodolphe Vuilleumier and other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-11572-4.

References

- 1.Ziman, J. Electrons and Phonons: The Theory of Transport Phenomena in Solids (Clarendon Press, 1960).

- 2.Fugallo G, Colombo L. Calculating lattice thermal conductivity: a synopsis. Phys. Scr. 2018;93:043002. doi: 10.1088/1402-4896/aaa6f3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baroni, S, Bertossa, R, Ercole, L, Grasselli, F. & Marcolongo, A. Heat Transport in Insulators from Ab Initio Green-Kubo Theory. 2edn, 1–36 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2018). .

- 4.Bedoya-Martinez ON, Barrat JL, Rodney D. Computation of the thermal conductivity using methods based on classical and quantum molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. B. 2014;89:014303. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.89.014303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green MS. Markoff random processes and the statistical mechanics of time-dependent phenomena. J. Chem. Phys. 1952;20:1281–1295. doi: 10.1063/1.1700722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green M. Markoff random processes and the statistical mechanics of time-dependent phenomena. ii. irreversible processes in fluids. J. Chem. Phys. 1954;22:398–413. doi: 10.1063/1.1740082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubo R. Statistical-mechanical theory of irreversible processes. I. General theory and simple applications to magnetic and conduction problems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1957;12:570–586. doi: 10.1143/JPSJ.12.570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubo R, Yokota M, Nakajima S. Statistical-mechanical theory of irreversible processes. ii. response to thermal disturbance. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1957;12:1203–1211. doi: 10.1143/JPSJ.12.1203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen P, Feldman J. Thermal conductivity of glasses: theory and application to amorphous si. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1989;62:645. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.62.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen P, Feldman J. Thermal conductivity of disordered harmonic solids. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;48:12581. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.48.12581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fabian J, Allen PB. Anharmonic decay of vibrational states in amorphous silicon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3839. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcolongo A, Umari P, Baroni S. Microscopic theory and ab initio simulation of atomic heat transport. Nat. Phys. 2016;12:80–84. doi: 10.1038/nphys3509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ercole L, Marcolongo A, Umari P, Baroni S. Gauge invariance of thermal transport coefficients. J. Low. Temp. Phys. 2016;185:79. doi: 10.1007/s10909-016-1617-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Negele, J. W. & Orland, H. Quantum Many-particle Systems (Perseus Books, 1988).

- 15.Rieder Z, Lebowitz JL, Lieb E. Properties of a harmonic crystal in a stationary nonequilibrium state. J. Math. Phys. 1967;8:1073–1078. doi: 10.1063/1.1705319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tersoff J. Modeling solid-state chemistry: interatomic potentials for multicomponent systems. Phys. Rev. B. 1989;39:5566–5568. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.39.5566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He Y, Donadio D, Galli G. Heat transport in amorphous silicon: Interplay between morphology and disorder. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011;98:144101. doi: 10.1063/1.3574366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He Y, Savic I, Donadio D, Galli G. Lattice thermal conductivity of semiconducting bulk materials: atomistic simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012;14:16209–16222. doi: 10.1039/c2cp42394d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larkin J, McGaughey A. Thermal conductivity accumulation in amorphous silica and amorphous silicon. Phys. Rev. B. 2014;89:144303. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.89.144303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan Z, et al. Force and heat current formulas for many-body potentials in molecular dynamics simulations with applications to thermal conductivity calculations. Phys. Rev. B. 2015;92:094301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.92.094301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan Z, Chen W, Vierimaa V, Harju A. Efficient molecular dynamics simulations with many-body potentials on graphics processing units. Comp. Phys. Commun. 2017;218:10. doi: 10.1016/j.cpc.2017.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ercole L, Marcolongo A, Baroni S. Accurate thermal conductivities from optically short molecular dynamics simulations. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:15835. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15843-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feldman JL, Kluge MD, Allen PB, Wooten F. Thermal conductivity and localization in glasses: numerical study of a model of amorphous silicon. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;48:12589–12602. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.48.12589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donadio D, Galli G. Temperature dependence of the thermal conductivity of thin silicon nanowires. Nano Lett. 2010;10:847–851. doi: 10.1021/nl903268y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu T, Ertekin E. Generalized Debye-Peierls/Allen-Feldman model for the lattice thermal conductivity of low-dimensional and disordered materials. Phys. Rev. B. 2016;93:155414–11. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.93.155414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lv W, Henry A. Direct calculation of modal contributions to thermal conductivity via Green–Kubo modal analysis. New J. Phys. 2016;18:013028–12. doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/18/1/013028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zink B, Pietri R, Hellman F. Thermal conductivity and specific heat of thin-film amorphous silicon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;96:55902. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.055902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cahill DG, Katiyar M, Abelson JR. Thermal conductivity of a-Si:H thin films. Phys. Rev. B. 1994;50:6077. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.50.6077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hellman O, Steneteg P, Abrikosov IA, Simak SI. Temperature dependent effective potential method for accurate free energy calculations of solids. Phys. Rev. B. 2013;87:1–8. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.87.104111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Errea I, Calandra M, Mauri F. Anharmonic free energies and phonon dispersions from the stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation: Application to platinum and palladium hydrides. Phys. Rev. B. 2014;89:422–16. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.89.064302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bianco R, Errea I, Paulatto L, Calandra M, Mauri F. Second-order structural phase transitions, free energy curvature, and temperature-dependent anharmonic phonons in the self-consistent harmonic approximation: Theory and stochastic implementation. Phys. Rev. B. 2017;96:014111–014126. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.96.014111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simoncelli, M., Marzari, N. & Mauri, F. Unified theory of thermal transport in crystals and disordered solids. Nature Phys. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41567-019-0520-x (2019).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the plots within this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Computer codes are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.