Abstract

The aim of this study was to provide a summary estimate of depression prevalence among people with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) in comparison to those without AS. A systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, the Cochrane database library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and Wanfang Database from their inception to December 2016. The results showed that thirty-one eligible studies involving 8,106 patients were analyzed. Fifteen methods of defining depression were reported. The overall pooled prevalence of depression was 35% (95% CI, 28–43%), with high between-study heterogeneity (I2=98.8%, p<0.001). The relative risk of depression among people with AS was 1.76 (95% CI: 1.21–2.55, eight studies, n=3,006) compared with people without AS. The depression score [standardized mean difference (SMD)=0.43, 95% CI: 0.19–0.67, seven studies, n=549] was higher in AS patients than in controls. The main influence on depression prevalence was the sample size and country of origin. In conclusion, one-third of people with AS experience symptoms of depression. Depression was more prevalent in AS patients than in controls. Further research is needed to identify effective strategies for preventing and treating depression among AS patients.

Keywords: Ankylosing spondylitis, Depression, Meta-analysis, Systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease with significant effects on patients’ physical function and psychological status [1,2]. It has become increasingly clear that psychological distress, such as depression or anxiety, is common in patients with including osteoarthritis [3], lupus [4] and rheumatic arthritis [5,6]. Individuals with AS are more likely to be depressed than healthy individuals [7]. Depression is a chronic, prevalent condition, and is a leading cause of disability, affecting at least 120 million people worldwide [8]. In a population based study, doctor-diagnosed depression was found to be increased 1.81 and 1.49 fold respectively in women and men with AS [9]. It may be explained that AS is related to inflammation of depression because it is an inflammatory disease. Depressed AS patients tended to have poor long-term outcomes, including increased disease activity [10,11], fatigue [12], decreased functionality [13], sleep disturbances [14], impaired quality of life [15], and high medical costs [16]. However, estimates of the prevalence of depression in AS patients varied across studies, from 3% [17] to 66% [18]. Such discrepancy could be explained by the differences in time frames when these studies were performed, study quality, or tools used for assessing depression. It is important for rheumatologists to establish reliable estimate of depression prevalence, in order to prevent, treat, and identify causes of depression in people with AS. Recent reviews have suggested that depression was highly prevalent among people with rheumatoid arthritis [19], osteoarthritis [3], and systemic lupus erythematosus [20]. Another systematic review found that the prevalence of neuropsychiatric damage in chronic rheumatic diseases such as lupus has been significantly increasing over the past 5 decades [21]. This finding is not surprising due to reduction in white matter and grey matter volumes in the very early stage of lupus [22]. As yet no systematic review has provided pooled prevalence estimates of depression in AS. Our goal was to fill this gap. We aimed to 1) describe the pooled prevalence of depression in people with AS; 2) compare depression prevalence and score in AS patients versus healthy controls; 3) explore the influence of study characteristics on prevalence estimates.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standard [23] and followed a predetermined registered protocol (PROSPERO: 42016052590).

Search strategy

The systematic literature search was conducted by two investigators independently through the PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Cochrane database library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and Wanfang Database for pertinent studies published in English or Chinese from their inception to December 2016. The computer-based searches combined terms related to AS patients [(depress* or depress* disorder$ or affective disorder$ or mood disorder$ or adjustment disorder$ or affective symptom$ or dysthymi*) AND (Ankylosing spondylitis or AS)] (Supplementary Material 1 in the online-only Data Supplement). The search was restricted to studies in humans. In addition, the reference lists of all identified relevant publications were reviewed. Finally, where published information was unclear or inadequate, we contacted the corresponding authors for more information.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible if they met the following criteria: 1) observational studies (cross-sectional and prospective studies) and baseline data of randomized controlled trials with or without a comparison group without AS; 2) depression was measured by self-reported symptom scales, physician/clinician diagnosis, or structured clinical diagnostic interview. Table 1 presented a full list of the eligible methods of detecting depression, alongside the numbers of participants assessed.

Table 1.

Overview of prevalence studies of depression in AS patients

| Study ID | Country | Participants | Men, % | Age, mean±SD/median (range), years | Disease duration, mean±SD/median (range), years | Criteria for detection of depression (cutoff) | Prevalence, % | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aissaoui 2012 | Morocco | 110 | 68.2 | 38.52±12.62 | 9 (0–40) | HADS (≥8) | 55.5 | 2 |

| Altan 2003 | NS | 63 | NS | NS | NS | HADS (≥8) | 33.3 | 1 |

| Anyfanti 2012 | Greece | 44 | 68.8 | NS | NS | Zung SDS (≥50) | 18.2 | 1 |

| Arisoy 2013 | Turkey | 9 | 88.9 | 39.4±10.1 | 10.6±7.6 | HADS (≥7) | 33 | 2 |

| Aydin 2016 | Turkey | 37 | 62.3 | 34.67±7.90 | 7.16±2.49 | HADS (≥8) | 48.5 | 3 |

| Baysal 2011 | Turkey | 243 | 86.4 | 34.65±10.36 | 6.02±6.60 | HADS (≥7) | 39.8 | 3 |

| Cakar 2007 | Turkey | 52 | 100 | 32.85±12.11 | 9.09±7.36 | 21 Item-BDI (≥14/25) | 50/13.5 | 2 |

| Cooksey 2015 | UK | 348 | 77.0 | 56.0±13.0 | 22.0±15.0 | HADS (≥11) | 7.5 | 4 |

| Demir 2013 | Turkey | 22 | 0 | 39.34±6.28 | 3.3±2.6 | 21 Item-BDI (≥14) | 45.5 | 2 |

| Dhakad 2015 | India | 100 | 100 | 34.42±9.78 | 4.84±0.06 | HADS (≥8) | 66 | 2 |

| Durmus 2015 | Turkey | 80 | 63.8 | 39.33±10.98 | 10.88±10.08 | 21 Item-BDI (>17) | 22.5 | 2 |

| Ertenli 2012 | Turkey | 16 | 81.2 | 36.4 ±10.3 | 12.8±9.5 | HADS (≥8) | 43.8 | 2 |

| Ersözlü-Bozkirli 2015 | Turkey | 29 | 79.3 | 34.4±10.3 | 4.1±6.2 | 21 Item-BDI (≥30) | 37.9 | 2 |

| Fallahi 2014 | Iran | 163 | 79.1 | 37.74±9.88 | 14.49±8.47 | Structured interview | 29.4 | 2 |

| Günaydin 2009 | Turkey | 62 | 83.9 | 39.6±10.3 | 10.3±7.9 | Zung SDS (≥50) | 27.4 | 2 |

| Hakkou 2011 | Morocco | 110 | 68.2 | 38.5±12.6 | 10.3±8.1 | HADS (≥8) | 55.5 | 2 |

| Healey 2009 | UK | 612 | 71.6 | 50.8±12.2 | 10.3±8.1 | HADS (≥8) | 32.4 | 5 |

| Hyphantis 2013 | Greece | 55 | 85.5 | 42.9±10.9 | 15.3±11.5 | PHQ-9 (≥5/10) | 40.7/14.8 | 2 |

| Jiang 2015 | China | 683 | 80.4 | 27.33±8.67 | 6.47±6.47 | Zung SDS (NS) | 64 | 4 |

| Li 2012 | China | 314 | 74.5 | 27.65±8.34 | 6.07±4.90 | Zung SDS (≥50) | 41.4 | 4 |

| Lian 2003 | China | 60 | 78.0 | 36.0±12.0 | >5 years (68%) | Zung SDS (≥41) | 43.3 | 2 |

| Martindale 2006 | UK | 89 | 83.1 | 50 (18–77) | 18 (12–29) | HADS (≥11) | 12.4 | 3 |

| Meesters 2014 | Sweden | 1,738 | 65 | 54.5±14.3 | NS | Structured interview, ICD-10 | 10 | 3 |

| Rodríguez-Lozano 2012 | Spain | 190 | 75 | 48.4±11.7 | 20.2±11 | HADS (≥11) | 11 | 2 |

| Rostom 2013 | Morocco | 110 | 100 | 38.5±12.6 | 9 (0–40) | HADS (≥8) | 55.5 | 3 |

| Schneeberger 2015 | Argentina | 64 | 89.1 | 44 (33–53) | 17 (10.3–25) | CES-D (≥16) | 39.1 | 2 |

| Shen 2016 | China | 2,331 | 64.9 | 36.50 (27.25–48.18) | NS | Structured interview, ICD-9 | 3.1 | 3 |

| Xu 2016 | China | 103 | 75.7 | 32.9±10.7 | NS | Zung SDS (≥53) | 36.9 | 2 |

NS: not stated, ID: identification, SD: standard deviation, AS: ankylosing spondylitis, HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, SDS: Self-rating Depression Scale, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire, ICD: International Classification of Diseases, CES-D: Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, NOS: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

Studies were excluded if: 1) the study was not published as the full reports, such as case reports, commentaries, conference abstracts and letters to editors; 2) the study had a retrospective design; and 3) participants with depression at baseline were not excluded for the analysis.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two trained investigators independently extracted data and assess quality of the studies included in this meta-analysis. Any disagreements in data extraction and quality assessment were resolved through discussion between the two investigators or adjudication with a third reviewer. We used a standardized form to record data on the authors, year of publication, country of study, participants, percentage of male participants, average age of participants, mean disease duration, criteria for detection of depression, and reported the prevalence or score of depression. If duplicate publications from the same study were identified, we would include the result with the largest number of individuals from the study. Wherever possible, we extracted the number affected and not affected by depression in each sample (using the authors’ cut-off points for each outcome measure). If this was not available, we extracted the mean and standard deviation of the depression assessment scale. The investigators independently fulfilled the quality assessment using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) in line with previous study [24]. Studies were judged to be at low risk of bias (≥3 points) or high risk of bias (<3 points).

Outcome measures

The outcomes of interest were major depression diagnosed with a structured clinical assessment [e.g., International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10] or depression assessed with a validated assessment tool or screening measure [e.g., the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)].

Statistical analyses

Three analyses were undertaken. First, we pooled studies reporting the prevalence of depression in the AS sample using a random-effects models [25,26]. Second, we used a pooled relative risk (RR) analysis with random-effect model. Third, we conducted a pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) analysis to investigate differences between those with and without AS. Statistical heterogeneity among studies was evaluated with I2 statistics with the values of 25%, 50%, and 75% respectively denoted cut-off points for low, moderate and high degrees of heterogeneity [27]. The influence of individual studies on the overall prevalence estimate was explored by serially excluding each study in a sensitivity analysis. Subgroup analyses were planned by overall study quality, sample size, country of origin and publication year to explore the sources of potential heterogeneity. Finally, we used Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation analyses to assess the association between variables and prevalence of depression in people with AS. Potential publication bias was evaluated with a funnel plot [28] and the Egger’s test [29]. Statistical analyses were all conducted on Statistical analyses were all conducted on STATA version 12.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Search results

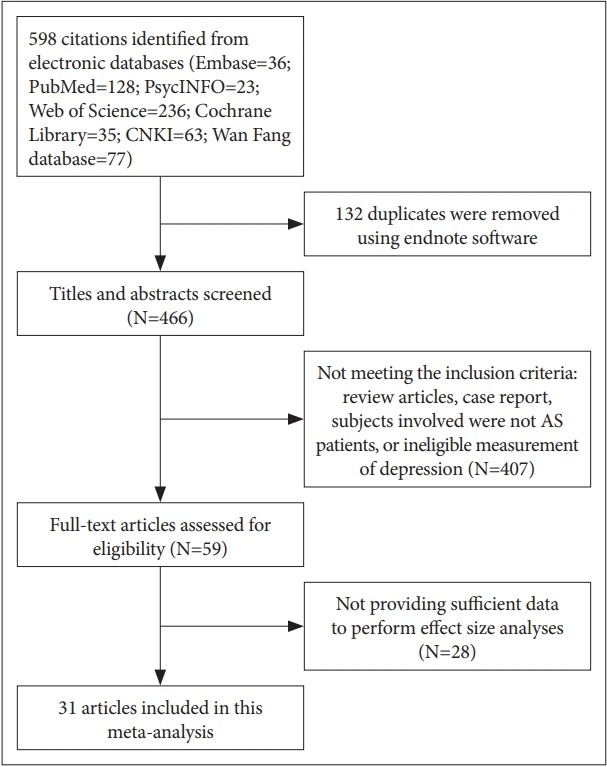

A total of 598 citations were identified. After removal of duplicates, titles and then abstracts were screened for potential eligibility. From this, 59 were potentially eligible and considered in the full-text review. Twenty-eight articles were excluded; thus, 31 records met the eligibility criteria and were included (Figure 1), and a full reference list was shown in Supplementary Material 2 (in the online-only Data Supplement). Inter-observer agreement (κ) between two investigators was 0.89.

Figure 1.

Search results and study selection.

Study characteristics

Table 1 and 2 presented the characteristics of the included studies. Thirty-one eligible studies consisted of 8,106 patients were reported. Nineteen studies were conducted in Asia, 7 studies in Europe, 3 studies in Africa, and 1 study in South America. The mean age was 39.2 years, and the mean percentage of males represented in the sample was 75.9%. In addition, the mean number of participants per study was 261, and the mean disease duration was 10.64 years. Table 3 described the methods defined depression and the frequency of their use. Depression was assessed in 15 different ways. Thirteen studies assessed for depression using the HADS; three different cut-off points were presented, the most commonly used being 8. Five studies assessed for depression using the 21 Item-BDI, with four different thresholds were presented in the articles. Six used the Zung Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS), and three used other screening tools. Three assessed for depression using structured interview (e.g., ICD). Supplementary Table 1 (in the online-only Data Supplement) summarized the quality assessment using a modified version of the NOS, which indicated that 1 study received 5 points, 3 studies received 4 points, 6 studies received 3 points, 18 studies received 2 points, and 3 studies received 1 point.

Table 2.

Overview of studies of depression in AS patients and control group

| Study ID | Country | Study design | Participants | % of male in AS group | % of male in control group | Mean/median age (years) in AS group±SD (range) | Mean/median age (years) in control group±SD (range) | Mean disease duration of AS (years)±SD | Depression measures | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altan 2003 | NS | Case control | 63 AS and 60 control | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | HADS | 1 |

| Baysal 2011 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 243 AS and 118 control | 86.4 | 78.8 | 34.65±10.36 | 36.53±9.26 | 6.02±6.60 | HADS | 3 |

| Demir 2013 | Turkey | Case control | 22 AS and 27 control | 0 | 0 | 39.34±6.28 | 37.58±9.58 | 3.3±2.6 | 21 Item-BDI | 2 |

| Dhakad 2015 | India | Case control | 100 AS and 100 control | 100 | 100 | 34.42±9.78 | 36.39±8.07 | 4.84±0.06 | HADS | 2 |

| Dincer 2007 | Turkey | Case control | 68 AS and 45 control | 100 | 100 | 32.9±11.0 | 30.1±6.24 | NS | 21 Item-BDI | 1 |

| Durmus 2015 | Turkey | Case control | 80 AS and 80 control | 63.8 | 71.2 | 39.33±10.98 | 36.41±10.84 | 10.88±10.08 | 21 Item-BDI | 2 |

| Ortancil 2010 | Turkey | Case control | 29 AS and 20 control | 69 | 60 | 42.0±9.7 | 38.2±12.5 | 9.4±7.7 | SCL-90-R | 2 |

| Ozkorumak 2011 | Turkey | Case control | 43 AS and 43 control | 100 | 100 | 36.25±8.76 | 36.53±6.54 | 7.51±7.22 | 21 Item-BDI | 2 |

| Schneeberger 2015 | Argentina | Case control | 64 AS and 95 control | 89.1 | 89.5 | 44 (33–53) | 40 (32–53) | 17 (10.3–25) | CES-D | 2 |

| Shen 2016 | China | Cohort | 2,331 AS and 9324 control | 64.9 | 64.9 | 36.50 (27.25–48.18) | 36.50 (27.25–48.18) | NS | ICD-9 | 3 |

| Xu 2016 | China | Cross-sectional | 103 AS and 121 control | 75.7 | 60.3 | 32.9±10.7 | 37.0±12.5 | NS | Zung SDS | 2 |

NS: not stated, ID: identification, SD: standard deviation, AS: ankylosing spondylitis, HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, SCL-90-R: Symptoms Checklist-90-Revised, CES-D: Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, ICD: International Classification of Diseases, SDS: Self-rating Depression Scale, NOS: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

Table 3.

Methods of detecting depression and summary of prevalence and heterogeneity findings

| Tool | Definition/cutoff | No. of studies | No. of participants | Prevalence, % (95% CI) | Heterogeneity I2, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADS | ≥7 | 2 | 252 | 40 (34–46) | 0 |

| ≥8 | 8 | 1,158 | 42 (39–45) | 91.1 | |

| ≥11 | 3 | 627 | 9 (6–12) | 29.6 | |

| 21 Item-BDI | ≥14 | 2 | 74 | 49 (34–60) | 0 |

| >17 | 1 | 80 | 22 (13–32) | - | |

| ≥25 | 1 | 52 | 14 (4–23) | - | |

| ≥30 | 1 | 29 | 38 (20–56) | - | |

| Zung SDS | >41 | 1 | 60 | 43 (31–56) | - |

| ≥50 | 3 | 420 | 30 (15–44) | 87.0 | |

| ≥53 | 1 | 103 | 37 (28–46) | - | |

| NS | 1 | 683 | 64 (60–68) | - | |

| Structured interview (e.g., ICD) | 3 | 4,232 | 13 (6–20) | 98.4 | |

| CES-D | ≥16 | 1 | 64 | 39 (27–51) | - |

| PHQ-9 | ≥5 | 1 | 55 | 41 (28–54) | - |

| ≥10 | 1 | 55 | 15 (5–24) | - |

NS: not stated, HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, SDS: Self-rating Depression Scale, ICD: International Classification of Diseases, CES-D: Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire

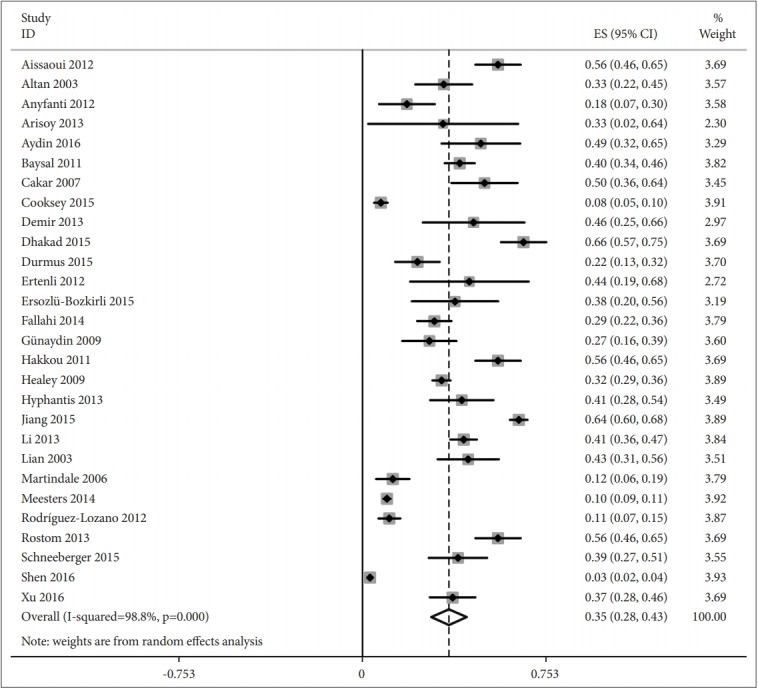

Prevalence of depression among AS patients

Prevalence estimates of depression varied from 3% to 66% in individual studies (Table 1). The overall pooled prevalence of depression was 35% (95% CI, 28–43%), with high betweenstudy heterogeneity (I2=98.8%, p<0.001) (Figure 2). Table 3 presented the summary of meta-analyses and heterogeneity assessments. Prevalence estimates ranged from 9% (95% CI, 6–12%, I2=29.6%) according to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale with thresholds of 11% to 49% (95% CI, 34–60%, I2=0%) for the 21-Item Beck Depression Inventory with a cutoff of 14 or more. Prevalence of major depressive disorder to be 13% (95% CI, 6–20%) according to the structured interview, with high heterogeneity (I2=98.4%).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of depression in ankylosing spondylitis patients.

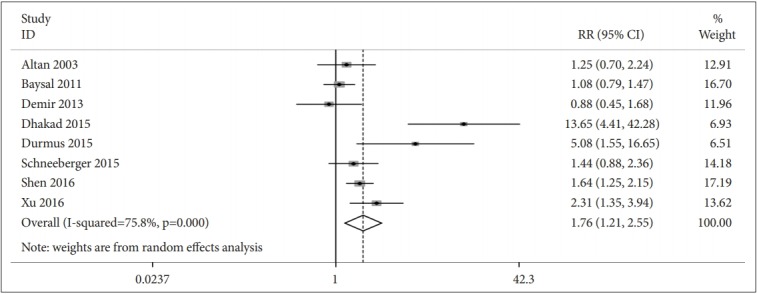

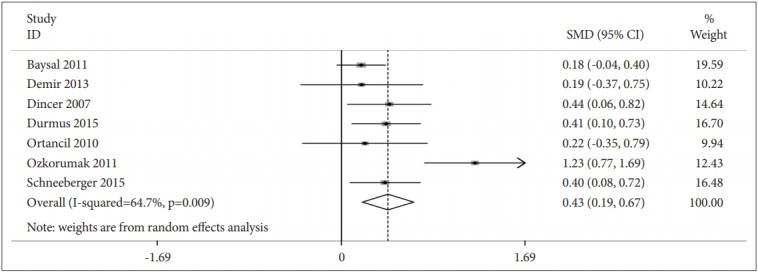

Depression in AS versus non-AS cohorts

Eight studies included data on the prevalence estimates of depression for people with AS compared with those without AS. A pooled RR of 1.76 (95% CI: 1.21–2.55, n=3006) (Figure 3). Seven studies (n=549) presented data comparing depression scores for people with AS compared with those without AS. The depression score (SMD=0.43, 95% CI: 0.19–0.67) was higher in AS patients than in controls (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Association between prevalence of depression in ankylosing spondylitis patients versus control group.

Figure 4.

Association between score of depression in ankylosing spondylitis patients versus control group.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

Table 4 showed the prevalence estimates of depression according to each sensitivity and subgroup analysis, in comparison with the primary analysis. Sensitivity analyses found that the exclusion of studies with less sample representativeness tended to decrease depression prevalence estimates according to structured interview. The pooled SMD tended to decrease in AS patients verse controls by exclusion of studies only using male sample. The subgroup analyses were conducted by sample size, overall quality, publication year, and country of origin. The results showed that studies with sample size <200 had higher depression prevalence estimates [52% (95% CI, 44–60%) vs. 42% (95% CI, 39–45%)] compared with primary analysis according to the HADS with thresholds of 8, and higher pooled RR [3.72 (95% CI, 1.33–10.38) vs. 1.48 (95% CI, 1.06–2.06)] in AS patients verse controls compared with the studies with sample size ≥200. When evaluated by Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), studies with lower total overall quality scores yielded higher depression estimates [52% (95% CI, 41–63%) vs. 45% (95% CI, 28–62%)] according to the HADS with thresholds of 8, and higher pooled RR [3.72 (95% CI, 1.33–10.38) vs. 1.48 (95% CI, 1.06–2.06)] compared with the studies with higher total overall quality scores. More recent publications and developing country tended to yield higher depression prevalence estimates according to the HADS with a cutoff of 8 or more. There was no particular trend or pattern in any other sensitivity analyses or subgroup analyses.

Table 4.

Impact of study characteristics on prevalence estimates for depression in AS: sensitivity and subgroup analyses

| Prevalence estimates for depression in AS patients |

Prevalence of depression in AS patients versus control group (RR) | Scores of depression in AS patients versus control group (SMD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADS (≥8) | HADS (≥11) | Zung SDS (≥50) | Structured interview | |||

| Primary analysis | 42 (39, 45) | 9 (6, 12) | 30 (15, 44) | 13 (6, 20) | 1.76 (1.21, 2.55) | 0.43 (0.19, 0.67) |

| I2=91.1% | I2=29.6% | I2=87.0% | I2=98.4% | I2=75.8% | I2=64.7% | |

| 8 studies | 3 studies | 3 studies | 3 studies | 8 studies | 7 studies | |

| 1,158 AS | 627 AS | 420 AS | 4,232 AS | 3,006 AS/9,925 control | 549 AS/428 control | |

| Sensitivity analyses | ||||||

| Excluding studies with less sample representativeness | - | - | - | 7 (0, 13) | - | - |

| I2=98.6% | ||||||

| 2 studies | ||||||

| 4,069 AS | ||||||

| Excluding studies with less comparable respondent and non-respondent comparability | 45 (28, 62) | 9 (5, 13) | - | - | - | - |

| I2=91.3% | I2=40.9% | |||||

| 3 studies | 2 studies | |||||

| 759 AS | 437 AS | |||||

| Excluding studies only using male sample | 45 (34, 56) | 9 (6, 12) | 30 (15, 44) | 13 (6, 20) | 1.85 (1.24, 2.75) | 0.28 (0.13, 0.43) |

| I2=87.0% | I2=29.6% | I2=87.0% | I2=98.4% | I2=64% | I2=0% | |

| 6 studies | 3 studies | 3 studies | 3 studies | 7 studies | 5 studies | |

| 948 AS | 627 AS | 358 AS | 4,232 AS | 2,906 AS/9,825 control | 438 AS/340 control | |

| Subgroup analyses | ||||||

| Sample size | ||||||

| <200 | 52 (44, 60) | 11 (8, 15) | 23 (14, 32) | - | 3.72 (1.33, 10.38) | 0.49 (0.22, 0.75) |

| I2=70.0% | I2=0% | I2=22.1% | I2=87% | I2=59% | ||

| 7 studies | 2 studies | 2 studies | 6 studies | 6 studies | ||

| 546 AS | 279 AS | 108 AS | 432 AS/483 control | 306 AS/310 control | ||

| ≥200 | - | - | - | 7 (0, 13) | 1.48 (1.06, 2.06) | - |

| I2=98.6% | I2=40% | |||||

| 2 studies | 2 studies | |||||

| 4,069 AS | 2574 AS/9442 control | |||||

| Overall quality | ||||||

| <3 points (low quality) | 52 (41, 63) | - | 23 (14, 32) | - | 3.72 (1.33, 10.38) | 0.49 (0.22, 0.75) |

| I2=79.4% | I2=22.1% | I2=87% | I2=59% | |||

| 5 studies | 2 studies | 6 studies | 6 studies | |||

| 399 AS | 108 AS | 432 AS/483 control | 306 AS/310 control | |||

| ≥3 points (high quality) | 45 (28, 62) | 9 (5, 13) | - | 7 (0, 13) | 1.48 (1.06, 2.06) | - |

| I2=91.3% | I2=40.9% | I2=98.6% | I2=40% | |||

| 3 studies | 2 studies | 2 studies | 2 studies | |||

| 759 AS | 437 AS | 4,069 AS | 2,574 AS/9,442 control | |||

| Publication year | ||||||

| 2000s | 32 (29, 32) | - | - | - | - | - |

| I2=0% | ||||||

| 2 studies | ||||||

| 675 AS | ||||||

| 2010– | 57 (52, 62) | 9 (5, 12) | 30 (8, 53) | 7 (0, 13) | 2.98 (1.47, 6.06) | 0.43 (0.15, 0.70) |

| I2=18.2% | I2=41.7% | I2=92.3% | I2=98.6% | I2=88% | I2=70% | |

| 6 studies | 2 studies | 2 studies | 2 studies | 7 studies | 6 studies | |

| 483 AS | 538 AS | 358 AS | 4,069 AS | 2,943 AS/9,865 control | 481 AS/383 control | |

| Country of origin | ||||||

| Asia | 55 (41, 70) | - | 35 (22, 49) | 16 (-10, 12) | 3.27 (1.41, 7.58) | 0.44 (0.15, 0.72) |

| I2=62.0% | I2=79.7% | I2=98.1% | I2=90% | I2=70% | ||

| 3 studies | 2 studies | 2 studies | 6 studies | 6 studies | ||

| 153 AS | 376 AS | 2,494 AS | 2,879 AS/9,770 control | 485 AS/333 control | ||

| Europe | - | 9 (6, 12) | - | - | - | - |

| I2=29.6% | ||||||

| 3 studies | ||||||

| 627 AS | ||||||

| Africa | 56 (50, 61) | - | - | - | - | - |

| I2=0% | ||||||

| 3 studies | ||||||

| 330 AS | ||||||

AS: ankylosing spondylitis, HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, SDS: Self-rating Depression Scale, RR: relative risk, SMD: standardized mean difference

Associated study variables

Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation analyses were employed to examine the relationship between variables including proportion of male participants, mean/medium age, mean/medium disease duration, sample size, representativeness, comparability, overall quality, country of origin, publication year, and the prevalence of depression. We found that small sample size (r=-0.45, p=0.016) and developing country (r=0.613, p=0.001) of the sample were significantly associated with increased depression prevalence (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pearson’s and Spearmen’s correlation between study characteristics and prevalence estimates

| Study characteristic | Depression prevalence estimate |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | r | p | |

| Male, % | 27 | 0.153 | 0.445 |

| Mean/medium age, year | 27 | -0.054 | 0.790 |

| Mean/medium disease duration, year | 27 | -0.035 | 0.861 |

| Sample size | 28 | -0.450* | 0.016 |

| Representativeness | 28 | -0.215 | 0.272 |

| Comparability | 28 | -0.066 | 0.737 |

| Overall quality | 28 | -0.055 | 0.780 |

| Country of origin | 27 | -0.613† | 0.001 |

| Publication year | 28 | 0.108 | 0.585 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01

Assessment of publication bias

According to the Egger’s test, assessment of publication bias suggested significant publication bias in studies reporting depression [Egger: bias=7.87 (95% CI: 4.77–10.97), p<0.001] (Supplementary Figure 1 in the online-only Data Supplement).

DISCUSSION

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of depression in AS. This study indicated that depression were more prevalent in AS patients than in controls. In this study, the pooled prevalence of depression in AS patients is 35% and higher than other chronic medical illnesses such as asthma (27%) [30], chronic obstructive lung disease (24.6%) [31], lupus (24%) [20] and rheumatoid arthritis (15%) [32]. This meta-analysis also revealed that small sample size and developing country of the studies conducted were significantly associated with increased depression prevalence, which might be explained that small studies often led to high prevalence estimates, and people with low socio-economic status (SES) in developing country was associated with increased susceptibility to depression [19].

Our sensitivity analyses indicated that depression prevalence estimates were relatively stable. Apart from the measurement tool used to ascertain depression, study quality and study population had impacts on the estimates detected. Our subgroup analyses found that variation in study sample size contributed importantly to the observed heterogeneity in the data. Studies with sample size <200 had higher depression estimates according to the HADS with a cutoff of 8 or more. Study quality might be a further explanation for the variance in prevalence estimates. Studies with lower total overall quality scores yielded higher depression estimates using the HADS with thresholds of 8.

We used rigorous methods to conduct the review and a reproducible, structured approach to data extraction and synthesis. The gold standard method was diagnostic interviews using ICD criteria, which were often time consuming and expensive, therefore, it was not ideal for investigating patients in a busy hospital environment [33]. Alternatively, self-report screening tools might be used. Although such self-reported questionnaires were quick and easy to complete and cheaper to use than diagnostic interviews in psychiatric practices, the different scales and cutoffs used to define the presence or the absence of depression could vary [33]. Such nature would lead to information bias and methodological heterogeneity when combining these data in a meta-analysis. It indicated that the rheumatologists should report prevalence at conventional cut-points, and screen for depression among AS patients according to the social and cultural contexts of the rheumatologists and patients in clinical practice.

However, this study still had some limitations. Firstly, a substantial amount of the heterogeneity among the studies remained unexplained by the variables examined. And there was inadequate data to conduct subgroup analyses according to variables of interest such as gender, disease duration and impact of age. A better understanding of social and cultural contexts of AS patients may help elucidate some of the root causes of depressive symptoms. Secondly, the data were derived from studies that used different designs and involved different groups of patients (e.g., different countries and years of publication), which might result in heterogeneity among the studies. Thirdly, the analysis relied on aggregated published data, which might result in potential publication bias.

CONCLUSIONS

One-third of people with AS experienced symptoms of depression. Depression was more prevalent in AS patients than in controls. Further research is needed to identify effective strategies for preventing and treating depression among AS patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the subjects for completing the article. This study was supported by Grants from the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (Grant no. 71904118).

Footnotes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Lijuan Zhang. Data curation: Yaping Wu. Formal analysis: Lijuan Zhang. Methodology: Lijuan Zhang. Project administration: Weiyi Zhu. Resources: Shiguang Liu. Software: Yaping Wu. Supervision: Shiguang Liu. Validation: Weiyi Zhu. Writing—original draft: Lijuan Zhang. Writing—review & editing: Weiyi Zhu.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2019.06.05.

REFERENCES

- 1.Braun J, Sieper J. Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet. 2007;369:1379–1390. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60635-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen B, Zhang A, Liu J, Da Z, Xu X, Liu H, et al. Body image disturbance and quality of life in Chinese patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Psychol Psychother. 2014;87:324–337. doi: 10.1111/papt.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stubbs B, Aluko Y, Myint PK, Smith TO. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and anxiety in osteoarthritis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Age Ageing. 2016;45:228–235. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mak A, Tang CS, Chan MF, Cheak AA, Ho RC. Damage accrual, cumulative glucocorticoid dose and depression predict anxiety in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:795–803. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1651-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L, Xia Y, Zhang Q, Fu T, Yin R, Guo G, et al. The correlations of socioeconomic status, disease activity, quality of life, and depression/anxiety in Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22:28–36. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2016.1198817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Y, Ho RC, Mak A. The role of interleukin (IL)-17 in anxiety and depression of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15:183–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2011.01673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu X, Shen B, Zhang A, Liu J, Da Z, Liu H, et al. Anxiety and depression correlate with disease and quality-of-life parameters in Chinese patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:879–885. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S86612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lépine JP, Briley M. The increasing burden of depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:3–7. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S19617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durmus D, Sarisoy G, Alayli G, Kesmen H, Çetin E, Bilgici A, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in ankylosing spondylitis: their relationship with disease activity, functional capacity, pain and fatigue. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;62:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batmaz I, Sariyildiz MA, Dilek B, Bez Y, Karakoc M, Cevik R. Sleep quality and associated factors in ankylosing spondylitis: relationship with disease parameters, psychological status and quality of life. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:1039–1045. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brionez TF, Assassi S, Reveille JD, Green C, Learch T, Diekman L, et al. Psychological correlates of self-reported disease activity in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:829–834. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunaydin R, Goksel Karatepe A, Cesmeli N, Kaya T. Fatigue in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: relationships with disease-specific variables, depression, and sleep disturbance. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:1045–1051. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brionez TF, Assassi S, Reveille JD, Learch TJ, Diekman L, Ward MM, et al. Psychological correlates of self-reported functional limitation in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R182. doi: 10.1186/ar2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aissaoui N, Rostom S, Hakkou J, Berrada Ghziouel K, Bahiri R, Abouqal R, et al. Fatigue in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: prevalence and relationships with disease-specific variables, psychological status, and sleep disturbance. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:2117–2124. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-1928-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hakkou J, Rostom S, Aissaoui N, Berrada KR, Abouqal R, Bahiri R, et al. Psychological status in Moroccan patients with ankylosing spondylitis and its relationships with disease parameters and quality of life. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:424–428. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31823a498e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho RC, Mak KK, Chua AN, Ho CS, Mak A. The effect of severity of depressive disorder on economic burden in a university hospital in Singapore. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;13:549–559. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2013.815409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen CC, Hu LY, Yang AC, Kuo BI, Chiang YY, Tsai SJ. Risk of psychiatric disorders following ankylosing spondylitis: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:625–631. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dhakad U, Singh BP, Das SK, Wakhlu A, Kumar P, Srivastava D, et al. Sexual dysfunctions and lower urinary tract symptoms in ankylosing spondylitis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;18:866–872. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matcham F, Rayner L, Steer S, Hotopf M. The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:2136–2148. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Fu T, Yin R, Zhang Q, Shen B. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:70. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1234-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mak A, Cheung MW, Chiew HJ, Liu Y, Ho RC. Global trend of survival and damage of systemic lupus erythematosus: meta-analysis and meta-regression of observational studies from the 1950s to 2000s. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41:830–839. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mak A, Ho RC, Tng HY, Koh HL, Chong JS, Zhou J. Early cerebral volume reductions and their associations with reduced lupus disease activity in patients with newly-diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22231. doi: 10.1038/srep22231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panic N, Leoncini E, de Belvis G, Ricciardi W, Boccia S. Evaluation of the endorsement of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement on the quality of published systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, Khan R, Guille C, Di Angelantonio E, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314:2373–2383. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1:97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung MW, Ho RC, Lim Y, Mak A. Conducting a meta-analysis: basics and good practices. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu Y, Mak KK, van Bever HP, Ng TP, Mak A, Ho RC. Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescents with asthma: a metaanalysis and meta-regression. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:707–715. doi: 10.1111/pai.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang MW, Ho RC, Cheung MW, Fu E, Mak A. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ho RC, Fu EH, Chua AN, Cheak AA, Mak A. Clinical and psychosocial factors associated with depression and anxiety in Singaporean patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2011;14:37–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hotopf M, Chidgey J, Addington-Hall J, Ly KL. Depression in advanced disease: a systematic review Part 1. Prevalence and case finding. Palliat Med. 2002;16:81–97. doi: 10.1191/02169216302pm507oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.