Abstract

Genomic selection (GS) is the one of the new method for molecular marker-assisted selection (MAS) that can improve selection efficiency and thereby accelerate selective breeding progress. In the present study, we used the exotic germplasm LK1 to improve the shelling percentage of Qi319 by GS. Genome-wide marker effects for each trait were estimated based on the performance of the testcross and SNP data for F2 progenies in the training population. The accuracy of genomic predictions was estimated as the correlation between marker-predicted genotypic values and phenotypic values of the testcrosses for each trait in the validation population. Our study result indicated that selection response for shell percentage was 33.7%, which is greater than those for grain yield, kernel number per ear, or grain moisture at harvest. Selection response for tassel branch number and weight per 100 kernels was greater than 60%. The Higher trait heritability resulted in better prediction efficiency; Prediction accuracy increased with the training population size; Prediction efficiency did not differ significantly between SNP densities of 1000 bp and 55,000 bp. The results of the present research project will provide a basis for genome-wide selection technology in maize breeding, and lay the groundwork for the application of GS to germplasms that are useful in China.

Keywords: maize, genomic selection (GS), ridge regression-best linear unbiased prediction (RR-BLUP), shelling percentage

Introduction

The rapid development of molecular biology and genomics has enabled new plant breeding technologies, such as marker-assisted selection (MAS), to emerge. MAS is a method of crop genetic improvement that synergizes phenotypic and genetic values to realize genetic direct selection and maximize genetic gain (Stuber et al. 1999). However, MAS has two flaws when the traits targeted for improvement are complex and controlled by multiple genes. First, quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping is normally used to begin selection in the progeny population. However, QTL mapping based on bi-parental populations is not universal for all germplasms of a crop and is sometimes not the most accurate for use in breeding (Moose and Mumm 2008). Second, important traits are often controlled by many genes with small effects and require appropriate statistical methods and breeding technologies to improve complex quantitative traits (Bernardo 2008). Thus, a new kind of MAS technology, genomic selection (GS), has emerged to address these shortcomings.

Meuwissen et al. (2001) first put forward the genomic selection (GS) breeding strategy, which uses a training population of individuals that have been genotyped and phenotyped. In Best Linear Unbiased Prediction (BLUP), the training population is comprised of genotyped individuals and their breeding values (mean performance of crosses with same tester). The breeding value of the candidate population is estimated by BLUP using genotypic data without testcross and phenotype information. The BLUP model produces genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) from the genotypic information for untested individuals. These GEBVs do not take into account the functions of the underlying genes, which would be an ideal selection criterion (Jannink et al. 2010). The genomic selection with GEBVs is superior to traditional breeding for increasing gains per unit time even if both models have equal efficiencies. In principle, the phenotypic values of the candidate individuals are not essential for selection, which shortens the length of the breeding cycle (Heffner et al. 2011).

Genomic selection has several advantages over traditional MAS. (1) QTL mapping is not necessary for GS. Genomic selection differs from previous strategies such as linkage and association mapping in that it abandons mapping the effects of single genes and instead of focuses on the efficient estimation of breeding values with a large number of molecular markers that ideally cover the entire genome (Jannink et al. 2010). (2) Genomic selection is more precise, especially for early selection. Genotyping uses high-density molecular markers to estimate all of the QTL effects and explain the genetic variance for most of the traits. But MAS uses only a few markers for trait selection, genomic selection is more accurate than MAS (Heffner et al. 2009). (3) Genomic selection can shorten the generation interval, accelerate genetic progress, and reduce production costs. The genetic progress achieved with GS is generally 4–25% than with phenotypic selection. GS can also cost 26–56% less than traditional breeding (Mayor and Bernardo 2009). (4) The efficiency of selection for low-heritability traits is higher with GS than with MAS. (5) Breeding values, sum of all of the allele genetic effects for each individual, are the selection criteria for GS. Because breeding values assess the mean performance of cross progeny, rather than the performance of the parents themselves, GS is more accurate (Massman et al. 2012).

Bernardo and Yu (2007) studied the application GS to maize breeding in the US (Bernardo and Yu 2007) using both simulations and empirical experiments. Piepho (2009) in Germany and Fritsche-Neto et al. (2012) in Brazil have also studied the use of GS in maize breeding. The step was a segregating maize population (F2 population) is genotyped and the testcross performance of the F3 generation is evaluated. Based on genotypic and phenotypic data, breeding values associated with a large set of markers (e.g., from 256 to 512 markers) are calculated for the traits of interest. Significance tests for markers are not used, and the effects of all markers are fitted as random effects in a linear model by best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP). Second, two or three generations of selection based on all markers are conducted in a year-round nursery (e.g., Hawaii or Puerto Rico) or greenhouse. Trait values are predicted as the sum of marker values across all markers for an individual plant, and selection is subsequently based on these genome-wide predictions. Using these methods, Combs and Bernardo (2013b) was able to introgress semi-dwarf germplasm into a U.S. Corn Belt inbred and found that genome-wide selection from Cycle 1 through Cycle 5 could either maintain or improve on the gains from phenotypic selection achieved in Cycle 1.

Shelling percentage is a key factor affecting the grain yield in maize. Although maize breeders have devoted themselves to improving shelling percentage, in China (Wang et al. 2011), there is a large performance gap between local hybrids and foreign hybrids for this trait. Maize shelling percentage is a typical quantitative trait that is controlled by genes with minor effects and is difficult to improve using traditional maize breeding approaches (Lu et al. 2011). Here, we demonstrate improvement in the shelling percentage of the inbred line Qi319 using genome-wide selection. The responses to genome-wide selection of other important traits were analyzed at the same time.

Materials and Methods

Germplasm

Inbred line Qi319 was developed at Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (SAAS) in the 1990s. It is an elite inbred line from which a series of approved fine maize crosses such as Ludan50 and others have been developed. However, Qi319 has low shelling percentage and the kernels dry slowly. The long-kerneled inbred line LK1 was introduced into China from the International Wheat and Maize Improvement Center (CIMMYT). LK1 has several merits including high shelling percentage, a high volume-to-weight ratio, and rapid rate of decrease in grain moisture after harvest. We thought that LK1 could be used to improve shelling percentage and the rate of decrease in grain moisture in Qi319.

The LK1 × Qi319 cross was made at Jinan in the summer of 2014. The resulting F1 individuals were selfed to form the F2 generation at Sanya in the winter of 2014. Random F2 plants were then selfed to form 159 F3 families at Jinan in the summer of 2015. The tester line lx03-2, from the Tangsipingtou heterotic group, a different heterotic group than Qi319, was used in this experiment.

Genotypic data and phenotypic data

DNA was extracted from leaves of individual F2 plants. Individual F2 plants were analyzed using 55K maize gene chips Affymetrix® Axiom™ at the Beijing Boao Jingdian Company. The maize 55K SNP array includes 55,229 SNPs evenly distributed across the maize genome (Cheng et al. 2017).

Testcrosses were made at Sanya in the winter of 2015 by crossing bulked pollen of 10–12 plants from each F3 family to the tester lx03-2. These 200 testcrosses were planted for evaluation at Jinan and Xinxiang on 30 May 2016 and 8 June 2017. A randomized complete block design with three replications was used at both locations. Each plot was 5 m in length and contained four rows that were 0.6 m apart. Data were collected from only the center two rows. Plant population density at both locations was 60,000 plants ha−1. Testcrosses were evaluated for eight traits including tassel branch number, grain moisture at harvest, grain yield, shelling percentage, ear length, kernel depth, kernels per spike, and hundred-grain weight (Table 1). Most traits were examined at both locations (e.g., Supplemental Data 1), except for grain moisture at harvest, which was assessed at only one location. Testcrosses were harvested by hand on 5 October 2016 and 10 October 2017.

Table 1.

Traits and measurement methods

| Trait | Measurement | Number | Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tassel branch number | Primary branches number of tassel | 10 plants | Filling stage to maturity |

| Grain moisture at harvest | During head sprouting stage, 10 spikes were bagged before silking. All bags were removed at the same time after silking. The 10 spikes were naturally pollinated. The grain moisture was measured by portable moisture meter during harvest | 10 plants | At harvest |

| Weight of dry ears | Total weight of all dry ears per whole plot | Whole plot | After harvest |

| Grain yield per plot | Total grain yield per whole plot | Whole plot | After harvest |

| Shelling percentage | Grain yield/dry ear weight | Whole plot | After harvest |

| Ear length | Length from the base to the tip of an ear | 10 ears | After harvest |

| Ear width | Width at the middle of an ear | 10 ears | After harvest |

| Cob width | Width of the cob at the middle of an ear | 10 ears | After harvest |

| Kernel depth | (Ear width–Cob width)/2 | 10 ears | After harvest |

| Ear rows | Row number per ear | 10 ears | After harvest |

| Grains per row | Kernel number of a row per ear | 10 ears | After harvest |

| Kernels per spike | Ear rows × Grains per row | 10 ears | After harvest |

| Hundred-grain weight | Weight of 100 kernels | 3 replications | After harvest |

Data analysis and population set

The performance of each entry was calculated using PROC GLM in SAS software version 9.1.3 for Windows 7 (SAS Institute. Cary. NC. 2009) to obtain means and standard errors for each trait. The genetic variance (VG) of testcrosses and heritability on an entry mean basis (h2) of each trait was estimated from ANOVA. F-tests were used to test whether VG and h2 were differed significantly among testcrosses for each trait.

Genome-wide marker effects for each cross were estimated based on the performance of the testcrosses for each trait and the SNP genotypes of the progenitors of F2 plants. Markers effects were estimated by ridge regression-best linear unbiased prediction (RR-BLUP) using R software version 3.4.2 (R Development Core Team 2017) for Windows 7. The accuracy of genome-wide predictions for each trait was estimated as the correlation between marker-predicted genotypic values and phenotypic values (rMP) of the testcrosses.

The RR-BLUP model was based on the phenotypic data of testcrosses and genotypic data of F2 individual plant:

Where y is an N × 1 vector of BLUEs obtained in the phenotypic analysis, b is a vector of F fixed effects and X its corresponding N × F design matrix. Z is a N × M matrix, which coded the M makers as either +1 or −1 for homozygous loci and 0 for heterozygous loci. Random marker effects were assumed to follow a normal distribution u~N (0, Iδ2u) with variance δ2u and e~N(0, Iδ2e).

Among the 159 F3 testcrosses, we randomly selected 80% crosses as a training population set and used the left-over 20% as validation population for each trait. The set program run 1000 times. Basing on the 1000 times running result, we calculated the average value as the final accuracy prediction for each trait.

Results and Discussion

ANOVA of testcrosses

ANOVA revealed significant differences between two locations, two years for all traits analyzed. The weather conditions of two years were great different, especially high temperature influencing grain development of miaze in 2017 in Jinan. Thus, all the traits were markedly different between the two years, as well as the two locations. Differences in trait means among crosses were also significant (Table 2). F3 families were early generation, remaining well separated. Thus, the testcrosses were markedly affected by environments between F3 families. There were no significant differences among replications for all traits except tassel branch number. The interaction between testcrosses and locations was also not significant for any trait except tassel branch number. The tassel development was markedly affected by weather conditions. High temperature reduced the tassel branches number. Therefore, there were significant differences in tassel branch number, not only among testcrosses, but also among replications and locations, and the genotype by environment interaction for this trait was significant.

Table 2.

Mean square of yield, shelling percentage, kernel depth, ear length, tassel branch number, hundred-grain weight, and kernels per spike for testcrosses, locations, years and replications in ANOVA

| Sources of variance | Grain yield (Kg/mu) | Shelling percentage (%) | Kernel depth (cm) | Ear length (cm) | Tassel branch number | Hundred-grain weight (g) | Kernels per spike |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | 576.59** | 868.96** | 10.05** | 178.27** | 194.02** | 162.33** | 482.77** |

| Year | 224.36** | 413.23** | 24.08** | 56.78** | 74.39** | 12.34** | 213.54** |

| Replication | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.53 | 10.03** | 1.48 | 0.67 |

| Testcross | 1.77** | 1.27* | 1.51** | 1.35* | 5.06** | 1.42** | 1.49** |

| Testcross*Location | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 1.49** | 0.39 | 1.07 |

significance at 0.05,

significance at 0.01.

Prediction of response to genome-wide selection

Testcross genetic variance (VG) and heritability (h2) was significant for all of the traits. Shelling percentage exhibited the lowest h2, only 16.26%. Shelling percentage was a quantitative trait, controlled by minor polygene. Therefore, genome-wide selection would be more suitable than conventional breeding and traditional molecular breeding for improving shelling percentage. Hundred-grain weight exhibited the highest heritability, 74.5%, among traits studied here. Tassel branch number and kernel depth each had relatively higher heritability, 64.51% and 61.42%, respectively. Grain yield, kernel number per ear, and ear length exhibited moderate heritability.

The accuracy of prediction for testcrosses ranged from 18.6 to 66.2% among all the traits. Although the h2 of shelling percentage was only 16.76%, lower than those of grain yield and kernel number per ear, the prediction accuracy for shelling percentage (33.7%) was higher than for grain yield (29.6%) and kernel number per ear (28.7%). This result indicated that genome-wide selection is more suitable than other methods for improving shelling percentage. The rMP of grain yield was lower than in previous studies (Combs and Bernardo 2013b, Zhao et al. 2012). Grain yield was a complex trait, and the prediction accuracy was not stable among different experiments. Here, the accuracy of prediction of grain moisture in testcrosses was only 18.6%, which was lower than those for other traits. However, Combs and Bernardo (2013b) determined the prediction of response for grain moisture at harvest as 57%. The testcrosses in the present study were harvested late on 5 October 2016 after a growing season of 127 days. There was little difference in grain moisture among testcrosses. The rMP for hundred-grain weight and tassel branch number were higher, 63.9% and 66.2%, respectively. Thus, we confirmed that higher trait heritability improves prediction of the response to selection.

Analysis of the factors affecting genome-wide selection

Factors known to affect prediction accuracy of GS include trait heritability (Heffner et al. 2009), calibration population size (Jannink et al. 2010), statistical model used (Heslot et al. 2012), the number and type of molecular markers used (Chen and Sullivan 2003, Poland and Rife 2012), linkage disequilibrium (Habier et al. 2007), the relationship between calibration and test set (TS) (Albrecht et al. 2011, Clark et al. 2011, Pszczola et al. 2012), and population structure (Guo et al. 2014, Saatchi et al. 2011, Windhausen et al. 2012). We analyzed three factors affecting predication accuracy, including the heritability of the trait, the number of molecular markers, and the size of the calibration population.

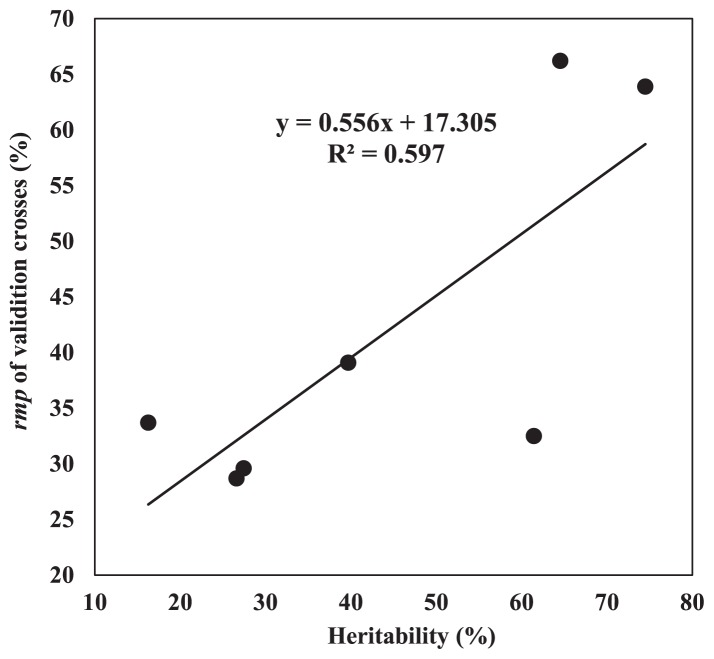

We made the regression analysis on the genomic selection accuracy and the heritability for all the traits (Table 3). The result indicated that the correlation coefficient between trait heritability and prediction response was 0.77. Regression analysis between trait heritability and prediction response indicated a regression coefficient (b) of 0.556 and a decision coefficient of 0.597 (Fig. 1). This reveals that prediction response increases with trait heritability, consistent with the result of Combs and Bernardo (2013a). For an increment in trait heritability of 1%, rMP increases by 0.556%.

Table 3.

Trait means, testcross genetic variance (VG), heritability on an entry-mean basis (h2), and correlation between marker-predicted genotypic values and phenotypic values (rMP) during cross-validation of testcrosses

| Trait | Mean | VG | VE | h2 | rMP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grain yield (Mg ha−1) | 8.48 | 390.35** | 1033.10 | 27.42%** | 29.6% |

| Shelling percentage (%) | 82.02 | 1575.43* | 8109.85 | 16.26%* | 33.7% |

| Kernel depth (cm) | 0.98 | 1.64** | 1.03 | 61.42%** | 32.5% |

| Tassel branch number | 11.82 | 1416.04** | 779.09 | 64.51%** | 66.2% |

| Ear length (cm) | 18.04 | 484.51* | 736.20 | 39.69%** | 39.1% |

| Kernel number per ear | 473.73 | 259,708.83** | 717,038.2 | 26.59%** | 28.7% |

| Grain moisture at harvest (%) | 31.33 | – | – | – | 18.6% |

| 100 kernels weight (g) | 34.99 | 2538.43** | 752.22 | 74.5%** | 63.9% |

significance at 0.05,

significance at 0.01.

Fig. 1.

Regression analysis on the genomic selection prediction accuracy and the heritability for all the traits.

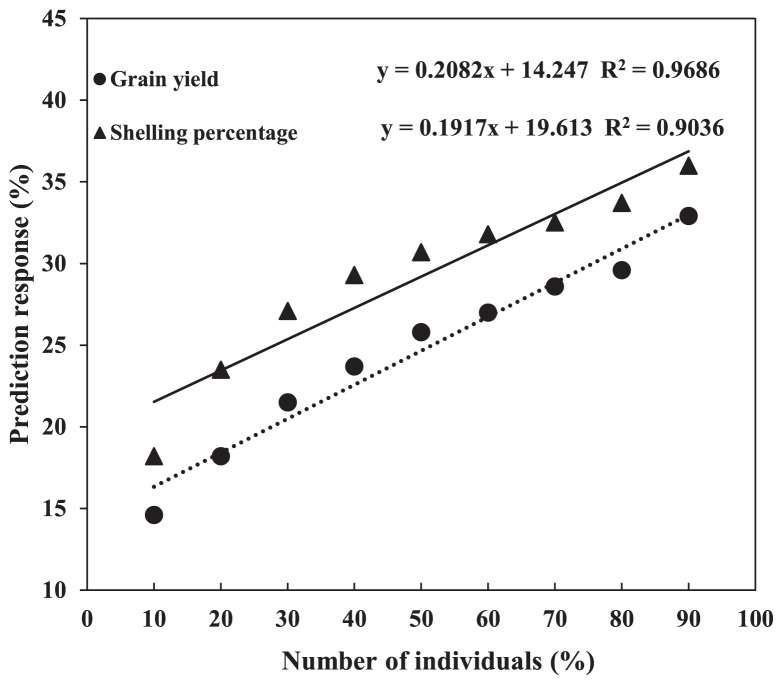

Simulations indicated that the size of the calibration population is crucial for prediction accuracy in genome-wide selection (Habier et al. 2007). We compared the prediction accuracy with different numbers of individuals in the training populations (from 10% to 90% of total individuals) for grain yield and shelling percentage and found that prediction accuracy increased with the increases in the size of the training population for both grain yield and shelling percentage. The prediction accuracy for grain yield varied from 14.6% to 32.9% and that for shelling percentage varied from 18.2% to 36%. Further, the prediction response increased linearly. The rMP for grain yield would increase 0.21% for a 1% increase in the size of the training population (decision coefficient R2 = 0.9686). The rMP for shelling percentage would increase 0.19% for a 1% increase in the size of the training population (decision coefficient R2 = 0.9036) (Fig. 2), similar to the results of Zhao et al. (2012). Meanwhile, we also found that overestimation occurred when the training population was too small. Consequently, our result for grain yield and shelling percentage clearly underline the importance of the size of the training population in genomic selection.

Fig. 2.

Regression of prediction accuracy on the size of the training population varied from 10% to 90% of the total population size, shown for grain yield and shelling percentage.

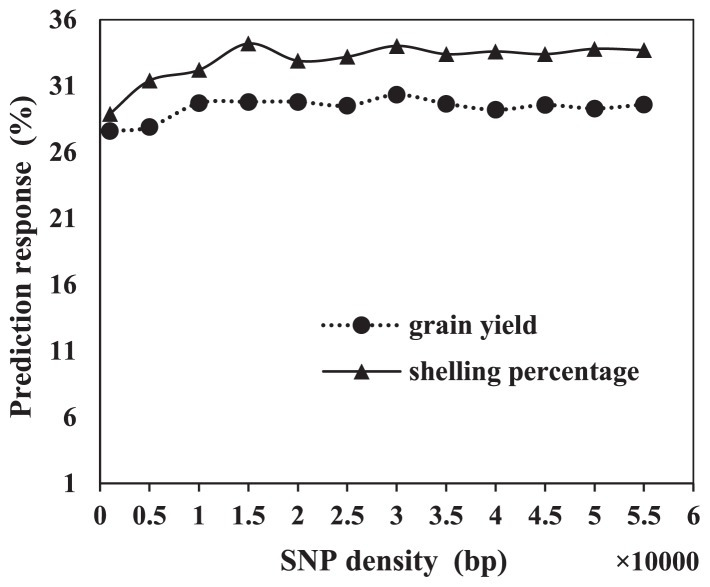

In the present study, we used 55k gene chips. However, in a previous study Zhao et al. (2012) used only 960 SNP markers to genotype elite maize breeding populations. We set up 11 SNP densities (from 1000 bp to 55,000 bp) to test the prediction accuracy of different SNP markers for grain yield and shelling percentage. Prediction accuracy changed little at SNP marker densities ranging from 1000 to 55,000 bp. The prediction effect for grain yield varied from 27.6% to 30.3% and the prediction effect for shelling percentage varied from 28.9% to 33.7% across SNP densities (Fig. 3). Thus, prediction accuracy did not significantly change with SNP densities ranging from 1000 to 55,000 bp.

Fig. 3.

Regression of prediction accuracy on the SNP densities varied from 1000 bp to 55000 bp, shown for grain yield and shelling percentage.

Genomic selection is the new molecular marker-assisted selection (MAS) model that can accelerate selective breeding progress and improve selection efficiency. We used the exotic germplasm LK1 to try to improve the shelling percentage of Qi319 by GS. Genome-wide marker effects for each cross were estimated based on the performance of testcrosses for each trait and SNP genotypes for the progenitors of F2 plants. The accuracy of genome-wide predictions was estimated as the correlation between marker-predicted genotypic values and phenotypic values of the testcrosses for each trait. Our results indicate that the selection response of shelling percentage is 33.7%, which was greater than that for grain yield, kernel number per ear, and grain moisture at harvest. The selection responses of tassel branch number and weight per 100 kernels were both above 60%. Higher trait heritability and larger training population sizes lead to better prediction accuracy. However, prediction accuracy did not significant change from with SNP densities ranging from 1000 to 55,000 bp. The results of this research will improve genomic selection breeding technology in maize and lay the groundwork for improvement of other traits in this important crop by GS.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgment

The present study was supported by the following organizations: the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31401457); the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-02-07); and the Taishan Scholar Seed Industry Talent Plan.

Literature Cite

- Albrecht, T., Wimmer, V., Auinger, H.J., Erbe, M., Knaak, C., Ouzunova, M., Simianer, H. and Schön, C.C. (2011) Genome-based prediction of testcross values in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 123: 339–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo, R. and Yu, J. (2007) Prospects for genome-wide selection for quantitative traits in maize. Crop Sci. 47: 1082–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo, R. (2008) Molecular markers and selection for complex traits in plants: learning from the last 20 years. Crop Sci. 48: 1649–1664. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. and Sullivan, P.F. (2003) Single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping: biochemistry, protocol, cost and throughput. Pharmacogenomics J. 3: 77–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X., Ren, Y.H., Jian, Y.Q., Guo, Z.F., Zhang, Y., Xie, C.X., Fu, J.J., Wang, H.W., Wang, G.Y., Xun, Y.B.et al. (2017) Development of a maize 55 K SNP array with improved genome coverage for molecular breeding. Mol. Breed. 37: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S., Hickey, J. and Werf, J. (2011) Different models of genetic variation and their effect on genomic evaluation. Genet. Sel. Evol. 43: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs, E. and Bernardo, R. (2013a) Accuracy of genomewide selection for different traits with constant population size, heritability, and number of markers. Plant Genome 6: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Combs, E. and Bernardo, R. (2013b) Genomewide selection to introgress semidwarf maize germplasm into U.S. Corn Belt inbreds. Crop Sci. 53: 1427–1436. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsche-Neto, R., DoVale, J.C., Malta de Lanes, E.C., Vilela de Resende, M.D. and Miranda, G.V. (2012) Genome wide selection for tropical maize root traits under conditions of nitrogen and phosphorus stress. Acta Sci. Agron. 34: 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z., Tucker, D.M., Basten, C.J., Gandhi, H., Ersoz, E., Guo, B., Xu, Z., Wang, D. and Gay, G. (2014) The impact of population structure on genomic prediction in stratified populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 127: 749–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habier, D., Fernando, R.L. and Dekkers, J.C.M. (2007) The impact of genetic relationship information on genome-assisted breeding values. Genetics 177: 2389–2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, E.L., Sorrells, M.E. and Jannink, J.L. (2009) Genomic selection for crop improvement. Crop Sci. 49: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, E.L., Jannink, J.L., Iwata, H., Souza, E. and Sorrells, M.E. (2011) Genomic selection accuracy for grain quality traits in biparental wheat populations. Crop Sci. 51: 2597–2606. [Google Scholar]

- Heslot, N., Yang, H.P., Sorrells, M.E. and Jannink, J.L. (2012) Genomic selection in plant breeding: a comparison of models. Crop Sci. 52: 146–160. [Google Scholar]

- Jannink, J.L., Lorenz, A.J. and Iwata, H. (2010) Genomic selection in plant breeding: from theory to practice. Brief. Funct. Genomics 9: 166–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M., Xie, C.X., Li, X.H., Hao, Z.F., Li, M.S., Weng, J.F., Zhang, D.G., Bai, L. and Zhang, S.H. (2011) Mapping of quantitative trait loci for kernel row number in maize across seven Environments. Mol. Breed. 28: 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Massman, J.M., Jung, H.J.G. and Bernardo, R. (2012) Genomewide selection versus marker-assisted recurrent selection to improve grain yield and stover-quality traits for cellulosic ethanol in maize. Crop Sci. 53: 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mayor, P.J. and Bernardo, R. (2009) Genomewide selection and marker-assisted recurrent selection in doubled haploid versus F2 populations. Crop Sci. 49: 1719–1725. [Google Scholar]

- Meuwissen, T.H., Hayes, B.J. and Goddard, M.E. (2001) Prediction of total genetic value using genome-wide dense marker maps. Genetics 157: 1819–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moose, S.P. and Mumm, R.H. (2008) Molecular plant breeding as the foundation for 21st century crop improvement. Plant Physiol. 147: 969–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piepho, H.P. (2009) Ridge regression and extensions for genomewide selection in maize. Crop Sci. 49: 1165–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Poland, J.A. and Rife, T.W. (2012) Genotyping-by-sequencing for plant breeding and genetics. Plant Genome 5: 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Pszczola, M., Strabel, T., Mulder, H.A. and Calus, M.P.L. (2012) Reliability of direct genomic values for animals with different relationships within and to the reference population. J. Diary Sci. 95: 389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Deveolopment Core Team (2017) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Release 3.4.2 Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Saatchi, M., McClure, M.C., McKay, S.D., Rolf, M.M., Kim, J.W., Decker, J.E., Taxis, T.M., Chapple, R.H., Ramey, H.R., Northcutt, S.L.et al. (2011) Accuracies of genomic breeding values in American Angus beef cattle using K-means clustering for cross-validation. Genet. Sel. Evol. 43: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute (2009) The SAS system for windows. Release 9.1.3 SAS Inst. Cary, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Stuber, C.W., Polacco, M. and Senior, M.L. (1999) Synergy of empirical breeding, marker-assisted selection, and genomics to increase crop yield potential. Crop Sci. 39: 1571–1583. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.Y., Ma, X L., Li, Y., Bai, D.P., Liu, C., Liu, Z.Z., Tan, X.J., Shi, Y.S., Song, Y.C., Carlone, M.et al. (2011) Changes in yield and yield components of single-cross maize hybrids released in China between 1964 and 2001. Crop Sci. 51: 512–525. [Google Scholar]

- Windhausen, V.S., Atlin, G.N., Crossa, J., Hickey, J.M., Jannink, J.-L., Sorrells, M.E., Raman, B., Cairns, J.E., Tarekegne, A., Semagn, K.et al. (2012) Effectiveness of genomic prediction of maize hybrid performance in different breeding populations and environments. G3 (Bethesda) 2: 1427–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.S., Gowda, M.C., Liu, W.X., Würschum, T., Maurer, H.P., Longin, F.H., Ranc, N. and Reif, J.C. (2012) Accuracy of genomic selection in European maize elite breeding populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 124: 769–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.