Abstract

Colletotrichum species are plant pathogens, saprobes, and endophytes on a range of economically important hosts. However, the species occurring on pear remain largely unresolved. To determine the morphology, phylogeny and biology of Colletotrichum species associated with Pyrus plants, a total of 295 samples were collected from cultivated pear species (including P. pyrifolia, P. bretschneideri, and P. communis) from seven major pear-cultivation provinces in China. The pear leaves and fruits affected by anthracnose were sampled and subjected to fungus isolation, resulting in a total of 488 Colletotrichum isolates. Phylogenetic analyses based on six loci (ACT, TUB2, CAL, CHS-1, GAPDH, and ITS) coupled with morphology of 90 representative isolates revealed that they belong to 10 known Colletotrichum species, including C. aenigma, C. citricola, C. conoides, C. fioriniae, C. fructicola, C. gloeosporioides, C. karstii, C. plurivorum, C. siamense, C. wuxiense, and two novel species, described here as C. jinshuiense and C. pyrifoliae. Of these, C. fructicola was the most dominant, occurring on P. pyrifolia and P. bretschneideri in all surveyed provinces except in Shandong, where C. siamense was dominant. In contrast, only C. siamense and C. fioriniae were isolated from P. communis, with the former being dominant. In order to prove Koch’s postulates, pathogenicity tests on pear leaves and fruits revealed a broad diversity in pathogenicity and aggressiveness among the species and isolates, of which C. citricola, C. jinshuiense, C. pyrifoliae, and C. conoides appeared to be organ-specific on either leaves or fruits. This study also represents the first reports of C. citricola, C. conoides, C. karstii, C. plurivorum, C. siamense, and C. wuxiense causing anthracnose on pear.

Keywords: Colletotrichum, multi-gene phylogeny, pathogenicity, Pyrus

INTRODUCTION

Colletotrichum species are important plant pathogens, saprobes, and endophytes, and can infect numerous plant hosts (Cannon et al. 2012, Dean et al. 2012, Diao et al. 2017, Guarnaccia et al. 2017). In recent years, the Colletotrichum species isolated from many host plants, e.g., Camellia sinensis (Theaceae), Capsicum annuum (Solanaceae), Citrus reticulata (Rutaceae), Mangifera indica (Anacardiaceae), and Vitis vinifera (Vitaceae), have been studied at a broad geographical level, which contributed to a better understanding of the genus (Huang et al. 2013, Lima et al. 2013, Vieira et al. 2014, Liu et al. 2015, Yan et al. 2015, Diao et al. 2017, Guarnaccia et al. 2017). Although Pyrus is an important host genus for Colletotrichum spp., the Colletotrichum spp. associated with pear anthracnose remained largely unresolved, with only six individual species identified including C. acutatum, C. aenigma, C. fioriniae, C. fructicola, C. pyricola, and C. salicis (Damm et al. 2012b, Weir et al. 2012). Moreover, previous reports chiefly investigated morphology and ITS sequence data (Wu et al. 2010, Liu et al. 2013b), which is insufficient for distinguishing closely related taxa in several species complexes (Liu et al. 2016a). Additionally, most of the species reported from pear were based on small sample sizes from restricted areas, thus underestimating the species diversity on this host (Damm et al. 2012b, Weir et al. 2012).

In the genus Pyrus, P. bretschneideri, P. communis, P. pyrifolia, P. sinkiangensis, and P. ussuriensis are commercially cultivated (Wu et al. 2013). Of these, P. bretschneideri, P. communis, and P. pyrifolia represent the major cultivated species in China (Zhao et al. 2016). Pear is the third most widespread temperate fruit crop after apple and grape, with the largest production in China (Wu et al. 2013). The pear industry is also one of the most important fruit industries worldwide. Statistical data for 2016 indicated that pear-cultivation area was 1 121 675 ha, yielding 19.5 MT fruit in China, accounting for 70 % of the global pear fruit yield (FAO 2016). Furthermore, Pyrus also originated from the tertiary period (about 65 to 55 M yr ago) in western China, which represents one of the two subcentres for genetic diversity of this genus (Rubtsov 1944, Vavilov 1951, Zeven & Zhukovsky 1975, Wu et al. 2013, Silva et al. 2014).

Characterisation of the Colletotrichum spp. associated with Pyrus plants is expected to provide a better insight into the biology of this important genus. Moreover, pear anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum spp. is an important disease in major pear-cultivation areas of China, occurring in the growth and fruit maturation periods of pear, mainly damaging leaves and fruits. Pear anthracnose has led to substantial economic losses due to excessive fruit rot, or the severe suppression of tree growth. However, a detailed study and knowledge of the Colletotrichum spp. affecting pear production has been lacking in China and is also poorly documented worldwide.

The taxonomy of the genus Colletotrichum has in the past mainly relied on host range and morphological characters (Von Arx 1957, Sutton 1980), which is limited in species resolution (Cai et al. 2009, Hyde et al. 2009, Cannon et al. 2012). Recently, multi-locus phylogenetic analyses together with morphological characteristics have significantly influenced the classification and species concepts in Colletotrichum (Cai et al. 2009, Cannon et al. 2012, Damm et al. 2012a, b, 2013, 2014, 2019, Weir et al. 2012, Liu et al. 2013a, 2014, Vieira et al. 2014, Yan et al. 2015, Guarnaccia et al. 2017). Phylogenetic analyses based on multi-locus DNA sequence data and the application of Genealogical Concordance Phylogenetic Species Recognition (GCPSR) represent an enhanced ability for species resolution (Quaedvlieg et al. 2014, Liu et al. 2016a, Diao et al. 2017), e.g., C. siamense was previously assumed to be a species complex composed of several taxa (Yang et al. 2009, Wikee et al. 2011, Lima et al. 2013, Vieira et al. 2014, Sharma et al. 2015), but was shown to represent a single variable species in the C. gloeosporioides species complex (Weir et al. 2012, Liu et al. 2016a). Based on recent progress, 14 Colletotrichum species complexes and 15 singleton species have been identified (Marin-Felix et al. 2017, Damm et al. 2019).

The aims of the present study were as follows:

identify the prevalence of Colletotrichum spp. associated with Pyrus anthracnose in the major production provinces in China;

validate the taxonomy of the Colletotrichum spp. through morphology, DNA phylogenetic analysis; and

evaluate their pathogenicity by proving Koch’s postulates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling and isolation

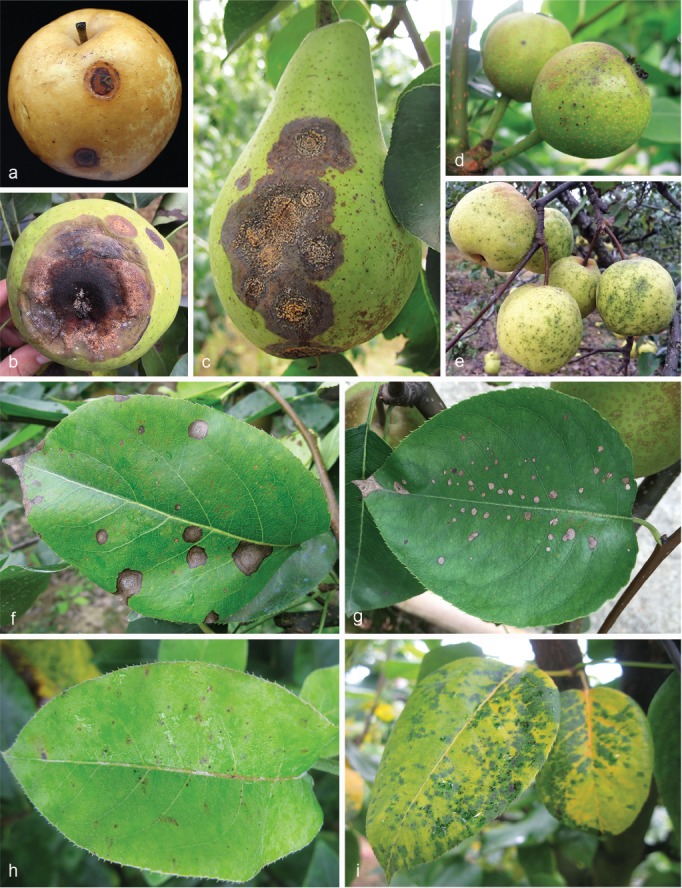

A survey was conducted in 15 commercial pear orchards and four nurseries (Aug. 2013 to Oct. 2016) in the seven major pear-cultivation provinces (Anhui, Fujian, Hubei, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Shandong, and Zhejiang) of China. Two kinds of symptoms were observed on fruit, namely 1) bitter rot showing big sunken rot lesions (BrL), 10–35 mm diam, with embedded concentric acervuli, secreting an orange conidial mass under humid conditions (Fig. 1a–c); and 2) tiny black spots (TS) less than 1 mm diam, gradually increasing in number instead of in size during the season (Fig. 1d, e). Three symptom types were observed on leaves, namely 1) big necrotic lesions (BnL); 2) small round spots (SS); and 3) TS. The BnL symptoms were characterised by sunken necrotic lesions 5–10 mm diam, brown in the centre but black along the margin, with black acervuli on the surface, secreting orange conidial tendrils under humid conditions (Fig. 1f). The SS symptoms were characterised by grey-white spots, 3–4 mm diam, circular to subcircular, grey-white in the centre, with a dark-brown margin (Fig. 1g). The TS symptoms were characterised by tiny black spots of less than 1 mm diam, which increased in number instead of in the size, accompanied by chlorosis, yellowing, and ‘green island regions’, resulting in defoliation (Fig. 1h, i).

Fig. 1.

Representative symptoms of pear anthracnose on fruits and leaves in the field. a–c. Symptoms of big sunken rot lesions (BrL; 10–35 mm diam) on fruits of P. pyrifolia (a, b) and P. communis cultivar (cv.) Gyuiot (c); d, e. symptoms of tiny black spots (TS; < 1 mm diam) on young pear fruits of P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan and mature pear fruit of P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan, respectively; f. symptoms of big necrotic lesions (BnL; 5–10 mm diam) on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Xiangnan; g. symptoms of small round spots (SS; 3–4 mm diam) on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1; h, i. initial and latter symptoms of TS on P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan.

Fruits and leaves showing the symptoms explained above were collected from pear trees of P. pyrifolia cultivars (cvs.) Cuiguan, Guanyangxueli, Hohsui, Huanghua, Huali No.1, Imamuraaki, Jinshui No. 1, Jinshui No. 2, and Xiangnan, P. bretschneideri cvs. Chili, Dangshansuli, Huangguan, Huangxianchangba, and Yali, and P. communis cv. Gyuiot in the surveyed orchards.

Fungi were isolated and linked to symptom types. Diseased tissues (neighbouring the asymptomatic regions) without sporulation were cut into small pieces (4–5 mm2) after surface sterilisation (1 % NaOCl for 45 s, 75 % ethanol for 45 s, washed three times in sterile water and dried on sterilised filter paper; Photita et al. 2005). Excised tissues were placed onto potato dextrose agar (PDA, 20 % diced potato, 2 % glucose, and 1.5 % agar, and distilled water) plates and incubated at 28 °C. For diseased tissues with sporulation, conidia were collected, suspended in sterilised water, diluted to a concentration of 1 × 104 conidia per mL, and spread onto the surface of water agar (WA, 2 % agar, and distilled water) to generate discrete colonies (Choi et al. 1999). Six single colonies of each isolate were picked up with a sterilised needle (insect pin, 0.5 mm diam) and transferred onto PDA plates. Pure cultures were stored in 25 % glycerol at -80 °C until use. Type specimens of new species from this study were deposited in the Mycological Herbarium, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China (HMAS), and ex-type living cultures were deposited in the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Centre (CGMCC), Beijing, China.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

Mycelial discs were transferred to PDA plates covered with sterile cellophane and incubated at 28 °C in the dark for 5–7 d. Fungal genomic DNA was extracted with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) buffer (2 % w/v CTAB, 1.42 M NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, 100 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, 0.2 % (w/v) β-mercaptoethanol) as previously described (Freeman et al. 1996). Six loci including the 5.8S nuclear ribosomal gene with the two flanking internal transcribed spacers (ITS), a 200-bp intron of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and partial actin (ACT), beta-tubulin (TUB2), chitin synthase (CHS-1), and calmodulin (CAL) genes were amplified using the primer pairs ITS4/ITS5 (White et al. 1990), GDF1/GDR1 (Guerber et al. 2003), ACT-512F/ACT-783R (Carbone & Kohn 1999), T1/Bt2b (Glass & Donaldson 1995, O’Donnell & Cigelnik 1997), CHS-79F/CHS-345R (Carbone & Kohn 1999), and CL1C/CL2C (Weir et al. 2012), respectively.

PCR amplification was conducted as described by Weir et al. (2012) but modified by using an annealing temperature of 56 °C for ITS, 59 °C for ACT and GAPDH, 58 °C for TUB2 and CHS-1, and 57 °C for CAL. PCR amplicons were purified and sequenced at the Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) Company, Ltd. Forward and reverse sequences were assembled to obtain a consensus sequence with DNAMAN (v. 9.0; Lynnon Biosoft). Sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of 90 representative isolates of 12 Colletotrichum spp. collected from pear in China, with details about host, symptoms, origins, and GenBank accession numbers.

| Species | Isolate No. | Host | Symptoms | Origin | GenBank accession number |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | GAPDH | CAL | ACT | CHS-1 | TUB2 | |||||

| C. aenigma | PAFQ1 | P. pyrifolia cv. Xiangnan, leaf | BnL | Zhongxiang, Hubei | MG747997 | MG747915 | MG747769 | MG747687 | MG747833 | MG748079 |

| PAFQ5 | P. pyrifolia cv. Huali No.1, leaf | BnL | Zhongxiang, Hubei | MG747998 | MG747916 | MG747770 | MG747688 | MG747834 | MG748080 | |

| PAFQ21 | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG747999 | MG747917 | MG747771 | MG747689 | MG747835 | MG748081 | |

| PAFQ23 | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748000 | MG747918 | MG747772 | MG747690 | MG747836 | MG748082 | |

| PAFQ24 | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748001 | MG747919 | MG747773 | MG747691 | MG747837 | MG748083 | |

| PAFQ45 | P. bretschneideri cv. Yali, leaf | BnL | Yancheng, Jiangsu | MG748002 | MG747920 | MG747774 | MG747692 | MG747838 | MG748084 | |

| PAFQ47 | P. bretschneideri cv. Chili, fruit | BrL | Yancheng, Jiangsu | MG748003 | MG747921 | MG747775 | MG747693 | MG747839 | MG748085 | |

| PAFQ64 | P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan, leaf | BnL | Dangshan, Anhui | MG748004 | MG747922 | MG747776 | MG747694 | MG747840 | MG748086 | |

| PAFQ66 | P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan, fruit | BrL | Dangshan, Anhui | MG748005 | MG747923 | MG747777 | MG747695 | MG747841 | MG748087 | |

| PAFQ81 | P. pyrifolia cv. Guanyangxueli, leaf | SS | Hangzhou, Zhejiang | MG748006 | MG747924 | MG747778 | MG747696 | MG747842 | MG748088 | |

| PAFQ83 | P. pyrifolia cv. Guanyangxueli, leaf | SS | Hangzhou, Zhejiang | MG748007 | MG747925 | MG747779 | MG747697 | MG747843 | MG748089 | |

| C. citricola | PAFQ13 | P. pyrifolia, leaf | BnL | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748062 | MG747980 | MG747819 | MG747752 | MG747898 | MG748142 |

| C. conoides | PAFQ6 | P. pyrifolia, fruit | BrL | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748008 | MG747926 | MG747780 | MG747698 | MG747844 | MG748090 |

| C. fioriniae | PAFQ8 | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748047 | MG747965 | – | MG747737 | MG747883 | MG748128 |

| PAFQ9 | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748048 | MG747966 | – | MG747738 | MG747884 | – | |

| PAFQ10 | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.2, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748049 | MG747967 | – | MG747739 | MG747885 | MG748129 | |

| PAFQ11 | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.2, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748050 | MG747968 | – | MG747740 | MG747886 | MG748130 | |

| PAFQ12 | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748051 | MG747969 | – | MG747741 | MG747887 | MG748131 | |

| PAFQ17 | P. pyrifolia, fruit | BrL | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748052 | MG747970 | – | MG747742 | MG747888 | MG748132 | |

| PAFQ18 | P. pyrifolia, fruit | BrL | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748053 | MG747971 | – | MG747743 | MG747889 | MG748133 | |

| PAFQ19 | P. pyrifolia, fruit | BrL | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748054 | MG747972 | – | MG747744 | MG747890 | MG748134 | |

| PAFQ34 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jianning, Fujian | MG748055 | MG747973 | – | MG747745 | MG747891 | MG748135 | |

| PAFQ35 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jianning, Fujian | MG748056 | MG747974 | – | MG747746 | MG747892 | MG748136 | |

| PAFQ36 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jianning, Fujian | MG748057 | MG747975 | – | MG747747 | MG747893 | MG748137 | |

| PAFQ49 | P. pyrifolia, fruit | BrL | Nanjing, Jiangsu | MG748060 | MG747978 | – | MG747750 | MG747896 | MG748140 | |

| PAFQ50 | P. pyrifolia, fruit | BrL | Nanjing, Jiangsu | MG748061 | MG747979 | – | MG747751 | MG747897 | MG748141 | |

| PAFQ55 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jinxi, Jiangxi | MG748058 | MG747976 | – | MG747748 | MG747894 | MG748138 | |

| PAFQ75 | P. communis cv. Gyuiot, fruit | BrL | Yantai, Shandong | MG748059 | MG747977 | – | MG747749 | MG747895 | MG748139 | |

| C. fructicola | PAFQ20 | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748011 | MG747929 | MG747783 | MG747701 | MG747847 | MG748093 |

| PAFQ25 | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748012 | MG747930 | MG747784 | MG747702 | MG747848 | MG748094 | |

| PAFQ31 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | TS | Jianning, Fujian | MG748013 | MG747931 | MG747785 | MG747703 | MG747849 | MG748095 | |

| PAFQ32 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jianning, Fujian | MG748014 | MG747932 | MG747786 | MG747704 | MG747850 | MG748096 | |

| PAFQ33 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jianning, Fujian | MG748015 | MG747933 | MG747787 | MG747705 | MG747851 | MG748097 | |

| PAFQ46 | P. bretschneideri cv. Yali, leaf | BnL | Yancheng, Jiangsu | MG748016 | MG747934 | MG747788 | MG747706 | MG747852 | MG748098 | |

| PAFQ48 | P. bretschneideri cv. Dangshanshuli, fruit | TS | Yancheng, Jiangsu | MG748017 | MG747935 | MG747789 | MG747707 | MG747853 | MG748099 | |

| PAFQ51 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jiangxi | MG748018 | MG747936 | MG747790 | MG747708 | MG747854 | MG748100 | |

| PAFQ57 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jinxi, Jiangxi | MG748019 | MG747937 | MG747791 | MG747709 | MG747855 | MG748101 | |

| PAFQ62 | P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan, leaf | BnL | Dangshan, Anhui | MG748020 | MG747938 | MG747792 | MG747710 | MG747856 | MG748102 | |

| PAFQ63 | P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan, leaf | BnL | Dangshan, Anhui | MG748021 | MG747939 | MG747793 | MG747711 | MG747857 | MG748103 | |

| PAFQ77 | P. pyrifolia cv. Guangyangxueli, leaf | BnL | Hangzhou, Zhejiang | MG748023 | MG747941 | MG747795 | MG747713 | MG747859 | MG748105 | |

| PAFQ79 | P. pyrifolia cv. Guanyangxueli, leaf | BnL | Hangzhou, Zhejiang | MG748024 | MG747942 | MG747796 | MG747714 | MG747860 | MG748106 | |

| PAFQ84 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Tonglu, Zhejiang | MG748022 | MG747940 | MG747794 | MG747712 | MG747858 | MG748104 | |

| C. gloeosporioides | PAFQ7 | P. bretschneideri cv. Huangxianchangba, leaf | BnL | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748025 | MG747943 | MG747797 | MG747715 | MG747861 | MG748107 |

| PAFQ27 | P. pyrifolia cv. Hohsui, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748026 | MG747944 | MG747798 | MG747716 | MG747862 | MG748108 | |

| PAFQ29 | P. pyrifolia cv. Hohsui, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748027 | MG747945 | MG747799 | MG747717 | MG747863 | MG748109 | |

| PAFQ44 | P. bretschneideri cv. Yali, leaf | SS | Yancheng, Jiangsu | MG748028 | MG747946 | MG747800 | MG747718 | MG747864 | MG748110 | |

| C. gloeosporioides (cont.) | PAFQ56 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jinxi, Jiangxi | MG748029 | MG747947 | MG747801 | MG747719 | MG747865 | MG748111 |

| PAFQ58 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jinxi, Jiangxi | MG748030 | MG747948 | MG747802 | MG747720 | MG747866 | MG748112 | |

| PAFQ59 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jinxi, Jiangxi | MG748031 | MG747949 | MG747803 | MG747721 | MG747867 | MG748113 | |

| PAFQ60 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jinxi, Jiangxi | MG748032 | MG747950 | MG747804 | MG747722 | MG747868 | MG748114 | |

| PAFQ61 | P. pyrifolia cv. Huanghua, fruit | BrL | Jinxi, Jiangxi | MG748033 | MG747951 | MG747805 | MG747723 | MG747869 | MG748115 | |

| PAFQ80 | P. pyrifolia cv. Guangyangxueli, leaf | SS | Hangzhou, Zhejiang | MG748035 | MG747953 | MG747807 | MG747725 | MG747871 | MG748117 | |

| PAFQ86 | P. pyrifolia, leaf | BnL | Hangzhou, Zhejiang | MG748034 | MG747952 | MG747806 | MG747724 | MG747870 | MG748116 | |

| C. jinshuiense | PAFQ26, CGMCC 3.18903* | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748077 | MG747995 | – | MG747767 | MG747913 | MG748157 |

| PAFQ26a | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG874830 | MG874822 | – | MG874807 | MG874814 | MG874838 | |

| PAFQ26b | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG874831 | MG874823 | – | MG874808 | MG874815 | MG874839 | |

| PAFQ26c | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG874832 | MG874824 | – | – | MG874816 | MG874840 | |

| PAFQ26d | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG874833 | MG874825 | – | MG874809 | MG874817 | MG874841 | |

| C. karstii | PAFQ14 | P. pyrifolia, leaf | BnL | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748063 | MG747981 | MG747820 | MG747753 | MG747899 | MG748143 |

| PAFQ15 | P. pyrifolia, leaf | BnL | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748064 | MG747982 | MG747821 | MG747754 | MG747900 | MG748144 | |

| PAFQ16 | P. pyrifolia, leaf | BnL | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748065 | MG747983 | MG747822 | MG747755 | MG747901 | MG748145 | |

| PAFQ28 | P. pyrifolia cv. Hohsui, leaf | BnL | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748066 | MG747984 | MG747823 | MG747756 | MG747902 | MG748146 | |

| PAFQ37 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jianning, Fujian | MG748067 | MG747985 | MG747824 | MG747757 | MG747903 | MG748147 | |

| PAFQ38 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jianning, Fujian | MG748068 | MG747986 | MG747825 | MG747758 | MG747904 | MG748148 | |

| PAFQ39 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jianning, Fujian | MG748069 | MG747987 | MG747826 | MG747759 | MG747905 | MG748149 | |

| PAFQ40 | P. pyrifolia cv. Huanghua, leaf | BnL | Jianning, Fujian | MG748070 | MG747988 | MG747827 | MG747760 | MG747906 | MG748150 | |

| PAFQ41 | P. pyrifolia cv. Huanghua, leaf | BnL | Jianning, Fujian | MG748071 | MG747989 | MG747828 | MG747761 | MG747907 | MG748151 | |

| PAFQ42 | P. pyrifolia cv. Huanghua, leaf | BnL | Jianning, Fujian | MG748072 | MG747990 | MG747829 | MG747762 | MG747908 | MG748152 | |

| PAFQ43 | P. pyrifolia cv. Huanghua, leaf | BnL | Jianning, Fujian | MG748073 | MG747991 | MG747830 | MG747763 | MG747909 | MG748153 | |

| PAFQ52 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jinxi, Jiangxi | MG748074 | MG747992 | MG747831 | MG747764 | MG747910 | MG748154 | |

| PAFQ82 | P. pyrifolia cv. Guanyangxueli, leaf | BnL | Hangzhou, Zhejiang | MG748075 | MG747993 | MG747832 | MG747765 | MG747911 | MG748155 | |

| C. plurivorum | PAFQ65 | P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan, leaf | BnL | Dangshan, Anhui | MG748076 | MG747994 | – | MG747766 | MG747912 | MG748156 |

| C. pyrifolia | PAFQ22, CGMCC 3.18902* | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG748078 | MG747996 | – | MG747768 | MG747914 | MG748158 |

| PAFQ22a | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG874834 | MG874826 | – | MG874810 | MG874818 | MG874842 | |

| PAFQ22b | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG874835 | MG874827 | – | MG874811 | MG874819 | MG874843 | |

| PAFQ22c | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG874836 | MG874828 | – | MG874812 | MG874820 | MG874844 | |

| PAFQ22d | P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No.1, leaf | SS | Wuhan, Hubei | MG874837 | MG874829 | – | MG874813 | MG874821 | MG874845 | |

| C. siamense | PAFQ67 | P. communis cv. Gyuiot, fruit | BrL | Yantai, Shandong | MG748036 | MG747954 | MG747808 | MG747726 | MG747872 | MG748118 |

| PAFQ68 | P. communis cv. Gyuiot, fruit | BrL | Yantai, Shandong | MG748037 | MG747955 | MG747809 | MG747727 | MG747873 | MG748119 | |

| PAFQ69 | P. communis cv. Gyuiot, fruit | BrL | Yantai, Shandong | MG748038 | MG747956 | MG747810 | MG747728 | MG747874 | MG748120 | |

| PAFQ70 | P. communis cv. Gyuiot, fruit | BrL | Yantai, Shandong | MG748039 | MG747957 | MG747811 | MG747729 | MG747875 | MG748121 | |

| PAFQ71 | P. communis cv. Gyuiot, fruit | BrL | Yantai, Shandong | MG748040 | MG747958 | MG747812 | MG747730 | MG747876 | MG748122 | |

| PAFQ72 | P. communis cv. Gyuiot, fruit | BrL | Yantai, Shandong | MG748041 | MG747959 | MG747813 | MG747731 | MG747877 | MG748123 | |

| PAFQ73 | P. communis cv. Gyuiot, fruit | BrL | Yantai, Shandong | MG748042 | MG747960 | MG747814 | MG747732 | MG747878 | MG748124 | |

| PAFQ74 | P. communis cv. Gyuiot, fruit | BrL | Yantai, Shandong | MG748043 | MG747961 | MG747815 | MG747733 | MG747879 | MG748125 | |

| PAFQ76 | P. communis cv. Gyuiot, fruit | BrL | Yantai, Shandong | MG748044 | MG747962 | MG747816 | MG747734 | MG747880 | – | |

| PAFQ78 | P. pyrifolia cv. Guanyangxueli, leaf | BnL | Hangzhou, Zhejiang | MG748046 | MG747964 | MG747818 | MG747736 | MG747882 | MG748127 | |

| PAFQ85 | P. pyrifolia, leaf | BnL | Hangzhou, Zhejiang | MG748045 | MG747963 | MG747817 | MG747735 | MG747881 | MG748126 | |

| C. wuxiense | PAFQ53 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jinxi, Jiangxi | MG748009 | MG747927 | MG747781 | MG747699 | MG747845 | MG748091 |

| PAFQ54 | P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, leaf | BnL | Jinxi, Jiangxi | MG748010 | MG747928 | MG747782 | MG747700 | MG747846 | MG748092 | |

* = Ex-type culture.

BrL: big sunken rot lesions; BnL: big necrotic lesions; SS: small round spots; TS: tiny black spots.

Phylogenetic analyses

Multiple sequences of concatenated ACT, TUB2, CAL, CHS-1, GAPDH and ITS sequences were aligned using MAFFT v. 7 (Katoh & Standley 2013) with default settings, and if necessary, manually adjusted in MEGA v. 7.0.1 (Kumar et al. 2016). Bayesian inference (BI) was used to construct phylogenies using MrBayes v. 3.1.2 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck 2003). MrModeltest v. 2.3 (Nylander 2004) was used to carry out statistical selection of best-fit models of nucleotide substitution using the corrected Akaike information criterion (AIC) (Table 2). Two analyses of four Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains were conducted from random trees with 1 × 107 generations for the C. gloeosporioides species complex, 3 × 106 for the C. dematium species complex and the related reference species involved in the same phylogenetic tree, and 2 × 106 generations for C. acutatum and C. boninense species complexes. The analyses were sampled every 1 000 generations, which were stopped once the average standard deviation of split frequencies was below 0.01. Convergence of all parameters was checked using the internal diagnostics of the standard deviation of split frequencies and performance scale reduction factors (PSRF), and then externally with Tracer v. 1.6 (Rambaut et al. 2013). The first 25 % of trees were discarded as the burn-in phase of each analysis and posterior probabilities determined from the remaining trees. Additionally, maximum parsimony analyses (MP) were performed on the multi-locus alignment using PAUP (Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony) v. 4.0b10 (Swofford 2002). Phylogenetic trees were generated using the heuristic search option with Tree Bisection Reconnection (TBR) branch swapping and 1 000 random sequence additions. Maxtrees were set up to 5 000, branches of zero length collapsed, and all multiple parsimonious trees were saved. Clade stability was assessed using a bootstrap analysis with 1 000 replicates. Afterwards, tree length (TL), consistency index (CI), retention index (RI), rescaled consistency index (RC), and homoplasy index (HI) were calculated. Furthermore, maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were implemented on the multi-locus alignments using the RaxmlGUI v. 1.3.1 (Silvestro & Michalak 2012). Clade stability was assessed using bootstrap analyses with 1 000 replicates. A general time reversible model (GTR) was applied with an invgamma-distributed rate variation. Phylogenetic trees were visualised in FigTree v. 1.4.2 (Rambaut 2014). The alignments and phylogenetic trees were deposited in TreeBASE (study 22264).

Table 2.

Nucleotide substitution models used in the phylogenetic analyses.

| Gene | Gloeosporioides clade | Acutatum clade | Boninense clade | Dematium clade and other taxa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | GTR+I+G | GTR+I | SYM+I+G | GTR+I+G |

| ACT | GTR+G | HKY+G | HKY+G | HKY+I+G |

| GAPDH | HKY+G | GTR+G | HKY+I | HKY+I+G |

| TUB2 | SYM+G | GTR+G | HKY+I | HKY+I+G |

| CHS-1 | K80+I | SYM+G | GTR+I | GTR+I+G |

| CAL | GTR+I+G | HKY+I |

For the phylogenetically close but not clearly delimited species, sequences were analysed using the GCPSR model by performing a pairwise homoplasy index (PHI) test as described by Quaedvlieg et al. (2014). The PHI test was performed in SplitsTree 4 (Huson 1998, Huson & Kloepper 2005, Huson & Bryant 2006) to determine the recombination level within phylogenetically closely related species using a six-locus concatenated dataset (ACT, TUB2, CAL, CHS-1, GAPDH, and ITS). If the resulting pairwise homoplasy index was below a 0.05 threshold (Ôw < 0.05), it was indicative of significant recombination in the dataset. The relationship between closely related species was visualised by constructing a splits graph.

Morphological analysis

Morphological and cultural features were characterised according to Yan et al. (2015). Briefly, mycelial discs (5 mm diam) were taken from the growing edge of 5-d-old cultures in triplicate, transferred on PDA, oatmeal agar (OA; Crous et al. 2009) and synthetic nutrient-poor agar medium (SNA; Nirenberg 1976), and incubated in the dark at 28 °C. Colony diameters were measured daily for 5 d to calculate their mycelial growth rates (mm/d). The shape, colour and density of colonies were recorded after 6 d. Moreover, the shape, colour and size of sporocarps, conidia, conidiophores, asci and ascospores were observed using light microscopy (Nikon Eclipse 90i or Olympus BX63, Japan), and 50 conidia or ascospores were measured to determine their sizes unless no or less spores were produced. Conidial appressoria were induced by dropping a conidial suspension (106 conidia/mL; 50 μL) on a concavity slide, placed inside plates containing moistened filter papers with distilled sterile water, and then incubated at 25 °C in the dark. After incubating for 24 to 48 h, the sizes of 30 conidial appressoria formed at the ends of germ tubes were measured (Yang et al. 2009).

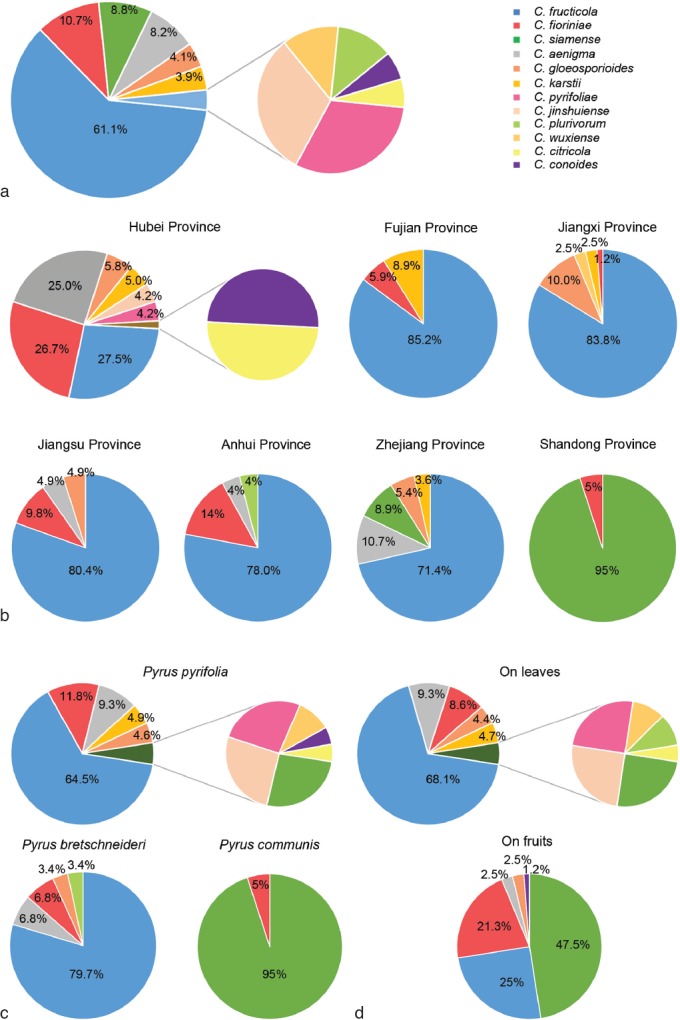

Prevalence

To determine the prevalence of Colletotrichum species in sampled provinces, the Pyrus spp. and pear organ (leaf or fruit) involved were established. The Isolation Rate (RI) was calculated for each species with the formula, RI % = (NS / NI) × 100, where NS was the number of isolates from the same species, and NI was the total number of isolates from each sample-collected province, Pyrus sp. or pear organ (Vieira et al. 2014, Wang et al. 2016). The overall RI was calculated using the NI value equal to the total number of isolates obtained from pear plants.

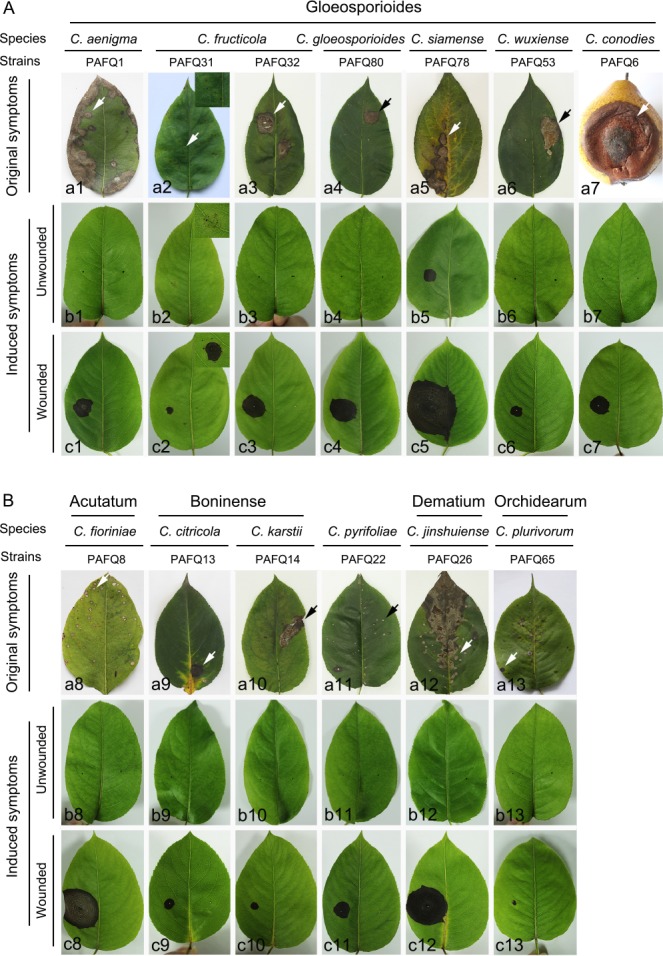

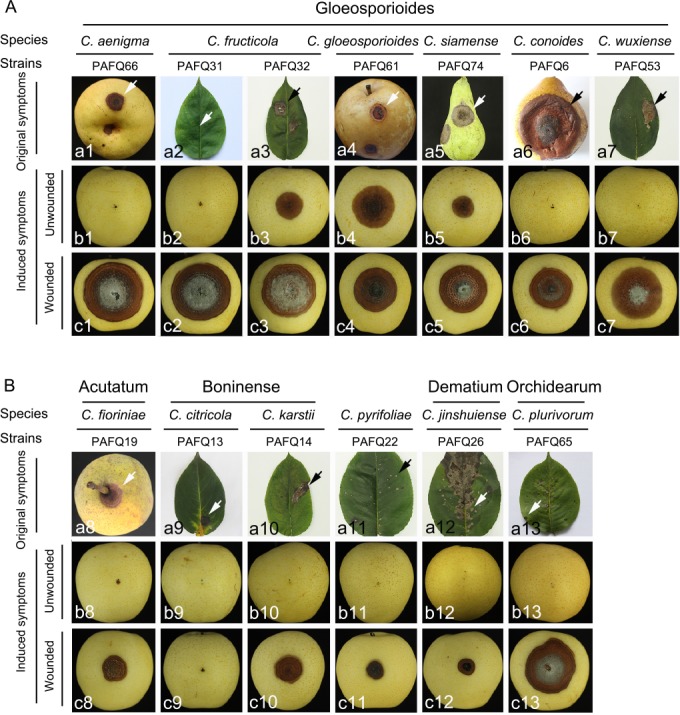

Pathogenicity tests

Representative Colletotrichum isolates were selected for pathogenicity tests with a spore suspension on detached leaves (approx. 4-wk-old) of P. pyriforia cv. Cuiguan in eight replicates as previously described (Cai et al. 2009). Briefly, tender healthy-looking leaves were collected, washed three times with sterile water, and air-dried on sterilised filter paper. The leaves are inoculated using the wound/drop and non-wound/drop inoculation methods (Lin et al. 2002, Kanchana-udomkan et al. 2004, Than et al. 2008). For the wound/drop method, an aliquot of 6 μL of spore suspension (1.0 × 106 conidia or ascospores per mL) was dropped on the left side of a leaf after wounding once by pin-pricking with a sterilised needle (insect pin, 0.5 mm diam), and sterile water on the right side of the same leaf in parallel as control. For non-wound/drop method, the spore suspension was dropped on the left side of a leaf without being unwounded, and sterile water on the right side of the same leaf in parallel as control. The infection rates were calculated using the formula (infection rate = the number of infected leaves or fruits/the number of inoculated leaves or fruits) at 14 d post inoculation (dpi) (Huang et al. 2013).

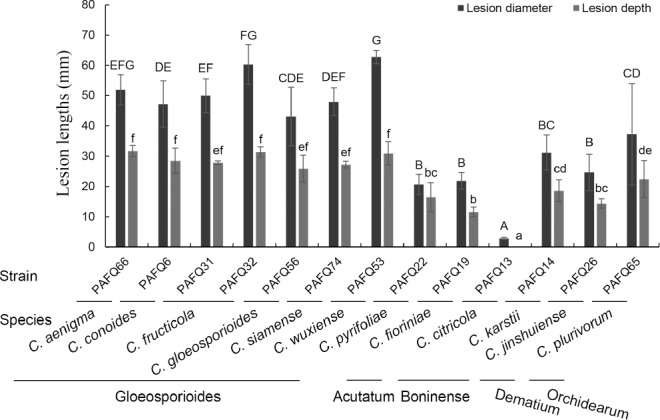

Additionally, pathogenicity was also determined on detached mature pear fruits of P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan in triplicate as previously described (Cai et al. 2009). Briefly, healthy fruits were surface-sterilised with 1 % sodium hypochlorite for 5 min, washed three times with sterile water, and air-dried. Wound/drop and non-wound/drop inoculation methods were also used (Lin et al. 2002, Kanchana-udomkan et al. 2004, Than et al. 2008). For the wound/drop method, an aliquot of 6 μL of spore suspension (1 × 106 conidia or ascospores per mL) was dropped on the fruits after wounding three times by pin-pricking with a sterilised needle (5 mm deep). For the non-wound/drop method, the same spore suspension was also directly dropped on the surface of unwounded pear fruits. Sterile water was dropped on the fruit in parallel as control. Symptom development under wounded conditions was evaluated by determining the mean lesion lengths at 10 dpi. Symptom development on fruits was studied by determining the infection rates at 30 dpi using the aforementioned formula.

After inoculation, the detached leaves and fruits were put on plastic trays, covered with plastic wrap to maintain a 99 % relative humidity, and incubated at 25 °C with a 12/12 h light/dark photoperiod. Pathogens were re-isolated from the resulting lesions and identified as described above. The pathogenicity tests were repeated once.

RESULTS

Colletotrichum isolates associated with pear anthracnose

A total of 295 pear samples (249 leaves and 46 fruits) affected by pear anthracnose, including BrL and TS on fruits, and BnL, SS, and TS on leaves were collected for fungal isolation, resulting in a total of 488 Colletotrichum isolates identified based on morphology and ITS sequence data. A total of 90 representative isolates were chosen for further analyses based on their morphology (colony shape, colour, and conidial morphology), ITS sequence data, symptom type, origin, and host cultivar involved (Table 1).

Multi-locus phylogenetic analyses

The 90 representative isolates (Table 1) together with 181 reference isolates from previously described species (Table 3) were subjected to multi-locus phylogenetic analyses with concatenated ACT, TUB2, CAL, CHS-1, GAPDH, and ITS sequences for those belonging to the C. gloeosporioides and C. boninense species complexes, or with concatenated ACT, TUB2, CHS-1, GAPDH, and ITS sequences for other species of which no CAL sequences are available. The results showed that isolates clustered together with 12 species in five Colletotrichum species complexes, including gloeosporioides (50 isolates), acutatum (15), boninense (14), dematium (5), and orchidearum (1), and one singleton species (5) (Fig. 2–5).

Table 3.

List of isolates of the Colletotrichum species used in this study, with details about host/substrate, country, and GenBank accession numbers.

| Species | Culturex | Host/Substrate | Country | GenBank accession number |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | GAPDH | CAL | ACT | CHS-1 | TUB2 | ||||

| C. abscissum | COAD 1877* | Citrus sinensis cv. Pera | Brazil | KP843126 | KP843129 | – | KP843141 | KP843132 | KP843135 |

| C. acerbum | CBS 128530* | Malus domestica | New Zealand | JQ948459 | JQ948790 | – | JQ949780 | JQ949120 | JQ950110 |

| C. acutatum | CBS 112996* | Carica papaya | Australia | JQ005776 | JQ948677 | – | JQ005839 | JQ005797 | JQ005860 |

| C. aenigma | ICMP 18608* | Persea americana | Israel | JX010244 | JX010044 | JX009683 | JX009443 | JX009774 | JX010389 |

| ICMP 18686 | Pyrus pyrifolia | Japan | JX010243 | JX009913 | JX009684 | JX009519 | JX009789 | JX010390 | |

| C. aeschynomenes | ICMP 17673* | Aeschynomene virginica | USA | JX010176 | JX009930 | JX009721 | JX009483 | JX009799 | JX010392 |

| C. agaves | CBS 118190 | Agave striate | Mexico | DQ286221 | – | – | – | – | – |

| C. alatae | CBS 304.67* | Dioscorea alata | India | JX010190 | JX009990 | JX009738 | JX009471 | JX009837 | JX010383 |

| C. alienum | ICMP 12071* | Malus domestica | New Zealand | JX010251 | JX010028 | JX009654 | JX009572 | JX009882 | JX010411 |

| C. annellatum | CBS 129826* | Hevea brasiliensis, leaf | Colombia | JQ005222 | JQ005309 | JQ005743 | JQ005570 | JQ005396 | JQ005656 |

| C. anthrisci | CBS 125334* | Anthriscus sylvestris,dead stem | Netherlands | GU227845 | GU228237 | – | GU227943 | GU228335 | GU228139 |

| CBS 125335 | Anthriscus sylvestris,dead stem | Netherlands | GU227846 | GU228238 | – | GU227944 | GU228336 | GU228140 | |

| C. aotearoa | ICMP 18537* | Coprosma sp. | New Zealand | JX010205 | JX010005 | JX009611 | JX009564 | JX009853 | JX010420 |

| C. asianum | ICMP 18580* | Coffea arabica | Thailand | FJ972612 | JX010053 | FJ917506 | JX009584 | JX009867 | JX010406 |

| C. australe | CBS 116478* | Trachycarpus fortunei | South Africa | JQ948455 | JQ948786 | – | JQ949776 | JQ949116 | JQ950106 |

| C. beeveri | CBS 128527* | Brachyglottis repanda | New Zealand | JQ005171 | JQ005258 | JQ005692 | JQ005519 | JQ005345 | JQ005605 |

| C. boninense | CBS 123755* | Crinum asiaticum var. sinicum | Japan | JQ005153 | JQ005240 | JQ005674 | JQ005501 | JQ005327 | JQ005588 |

| CBS 128506 | Solanum lycopersicum, fruit rot | New Zealand | JQ005157 | JQ005244 | JQ005678 | JQ005505 | JQ005331 | JQ005591 | |

| C. brasiliense | CBS 128501* | Passiflora edulis, fruit anthracnose | Brazil | JQ005235 | JQ005322 | JQ005756 | JQ005583 | JQ005409 | JQ005669 |

| C. brassicicola | CBS 101059* | Brassica oleracea, leaf spot | New Zealand | JQ005172 | JQ005259 | JQ005693 | JQ005520 | JQ005346 | JQ005606 |

| C. brevisporum | BCC 38876* | Neoregalia sp. | Thailand | JN050238 | JN050238 | – | JN050216 | KF687760 | JN050244 |

| C. brisbanense | CBS 292.67* | Capsicum annuum | Australia | JQ948291 | JQ948621 | – | JQ949612 | JQ948952 | JQ949942 |

| C. cairnsense | BRIP 63642* | Capsicum annuum | Australia | KU923672 | KU923704 | – | KU923716 | KU923710 | KU923688 |

| C. camelliae-japonicae | CGMCC 3.18118* | Camellia japonica | Japan | KX853165 | KX893584 | – | KX893576 | – | KX893580 |

| CGMCC 3.18117 | Camellia japonica | Japan | KX853164 | KX893583 | – | KX893575 | – | KX893579 | |

| C. carthami | SAPA100011* | Carthamus tinctorium | Japan | AB696998 | – | – | – | – | AB696992 |

| C. cattleyicola | CBS 170.49* | Cattleya sp. | Belgium | MG600758 | MG600819 | – | MG600963 | MG600866 | MG601025 |

| C. chlorophyti | IMI 103806* | Chlorophytum sp. | India | GU227894 | GU228286 | – | GU227992 | GU228384 | GU228188 |

| C. chrysanthemi | IMI 364540 | Chrysanthemum coronarium, leaf spot | China | JQ948273 | JQ948603 | – | JQ949594 | JQ948934 | JQ949924 |

| C. circinans | CBS 221.81* | Allium cepa | Serbia | GU227855 | GU228247 | – | GU227953 | GU228345 | GU228149 |

| C. citricola | CBS 134228* | Citrus unshiu | China | KC293576 | KC293736 | KC293696 | KC293616 | KC293696 | KC293656 |

| CBS 134229 | Citrus unshiu | China | KC293577 | KC293737 | KC293697 | KC293617 | KC293793 | KC293657 | |

| CBS 134230 | Citrus unshiu | China | KC293578 | KC293738 | KC293698 | KC293618 | KC293794 | KC293658 | |

| C. clidemiae | ICMP 18658* | Clidemia hirta | USA, Hawaii | JX010265 | JX009989 | JX009645 | JX009537 | JX009877 | JX010438 |

| C. cliviicola | CBS 125375* | Clivia miniata | China | JX519223 | JX546611 | – | JX519240 | JX519232 | JX519249 |

| CSSS1 | Clivia miniata | China | GU109479 | GU085867 | – | GU085861 | GU085865 | GU085869 | |

| CSSS2 | Clivia miniata | China | GU109480 | GU085868 | – | GU085862 | GU085866 | GU085870 | |

| C. colombiense | CBS 129818* | Passiflora edulis, leaf | Colombia | JQ005174 | JQ005261 | JQ005695 | JQ005522 | JQ005348 | JQ005608 |

| C. conoides | CGMCC 3.17615* | Capsicum annuum | China | KP890168 | KP890162 | KP890150 | KP890144 | KP890156 | KP890174 |

| CAUG33 | Capsicum annuum | China | KP890169 | KP890163 | KP890151 | KP890145 | KP890157 | KP890175 | |

| CAUG34 | Capsicum annuum | China | KP890170 | KP890164 | KP890152 | KP890146 | KP890158 | KP890176 | |

| C. constrictum | CBS 128504* | Citrus limon, fruit rot | New Zealand | JQ005238 | JQ005325 | JQ005759 | JQ005586 | JQ005412 | JQ005672 |

| C. cordylinicola | ICMP 18579* | Cordyline fruticosa | Thailand | JX010226 | JX009975 | HM470238 | HM470235 | JX009864 | JX010440 |

| C. cosmi | CBS 853.73* | Cosmos sp., seed | Netherlands | JQ948274 | JQ948604 | – | JQ949595 | JQ948935 | JQ949925 |

| C. costaricense | CBS 330.75* | Coffea arabica, cv. Typica, berry | Costa Rica | JQ948180 | JQ948510 | – | JQ949501 | JQ948841 | JQ949831 |

| C. curcumae | IMI 288937* | Curcuma longa | India | GU227893 | GU228285 | – | GU227991 | GU228383 | GU228187 |

| C. cuscutae | IMI 304802* | Cuscuta sp. | Dominica | JQ948195 | JQ948525 | – | JQ949516 | JQ948856 | JQ949846 |

| C. cymbidiicola | IMI 347923* | Cymbidium sp., leaf lesion | Australia | JQ005166 | JQ005253 | JQ005687 | JQ005514 | JQ005340 | JQ005600 |

| C. dacrycarpi | CBS 130241* | Dacrycarpus dacrydioides, leaf endophyte | New Zealand | JQ005236 | JQ005323 | JQ005757 | JQ005584 | JQ005410 | JQ005670 |

| C. dematium | CBS 125.25* | Eryngium campestre,dead leaf | France | GU227819 | GU228211 | – | GU227917 | GU228309 | GU228113 |

| CBS 123728 | Genista tinctoria, leaf spot | Czech Republic | GU227822 | GU228214 | – | GU227920 | GU228312 | GU228116 | |

| C. dracaenophilum | CBS 118199* | Dracaena sp. | China | JX519222 | JX546707 | – | JX519238 | JX519230 | JX519247 |

| C. euphorbiae | CBS 134725* | Euphorbia sp. | South Africa | KF777146 | KF777131 | – | KF777125 | KF777128 | KF777247 |

| C. fioriniae | CBS 125396 | Malus domestica, fruit lesion | USA | JQ948299 | JQ948629 | – | JQ949620 | JQ948960 | JQ949950 |

| IMI 324996 | Malus pumila | USA | JQ948301 | JQ948631 | – | JQ949622 | JQ948962 | JQ949952 | |

| CBS 126526 | Primula sp., leaf spots | Netherlands | JQ948323 | JQ948653 | – | JQ949644 | JQ948984 | JQ949974 | |

| CBS 124958 | Pyrus sp., fruit rot | USA | JQ948306 | JQ948636 | – | JQ949627 | JQ948967 | JQ949957 | |

| IMI 504882 | Fragaria × ananassa | New Zealand | KT153562 | KT153552 | – | KT153542 | KT153547 | KT153567 | |

| CBS 129938 | Malus domestica | USA | JQ948296 | JQ948626 | – | JQ949617 | JQ948957 | JQ949947 | |

| CBS 119292 | Vaccinium sp., fruit | New Zealand | JQ948313 | JQ948643 | – | JQ949634 | JQ948974 | JQ949964 | |

| CBS 129930 | Malus domestica | New Zealand | JQ948304 | JQ948634 | – | JQ949625 | JQ948965 | JQ949955 | |

| ATCC 28992 | Malus domestica | USA | JQ948297 | JQ948627 | – | JQ949618 | JQ948958 | JQ949948 | |

| C. fructi | CBS 346.37* | Malus sylvestris, fruit | USA | GU227844 | GU228236 | – | GU227942 | GU228334 | GU228138 |

| C. fructicola | ICMP 18581* | Coffea arabica | Thailand | JX010165 | JX010033 | FJ917508 | FJ907426 | JX009866 | JX010405 |

| ICMP 18613 | Limonium sinuatum | Israel | JX010167 | JX009998 | JX009675 | JX009491 | JX009772 | JX010388 | |

| ICMP 18645 | Theobroma cacao | Panama | JX010172 | JX009992 | JX009666 | JX009543 | JX009873 | JX010408 | |

| ICMP 18727 | Fragaria × ananassa | USA | JX010179 | JX010035 | JX009682 | JX009565 | JX009812 | JX010394 | |

| ICMP 18120 | Dioscorea alata | Nigeria | JX010182 | JX010041 | JX009670 | JX009436 | JX009844 | JX010401 | |

| C. fructicola (syn. C. ignotum) | ICMP 18646* | Tetragastris panamensis | Panama | JX010173 | JX010032 | JX009674 | JX009581 | JX009874 | JX010409 |

| C. fructicola (syn. Glomerella cingulata var. minor) | ICMP 17921* | Ficus edulis | Germany | JX010181 | JX009923 | JX009671 | JX009495 | JX009839 | JX010400 |

| C. fructivorum | CBS 133125* | Vaccinium macrocarpon | USA | JX145145 | – | – | – | – | JX145196 |

| CBS 133135 | Rhexia virginica | USA | JX145133 | – | – | – | – | JX145184 | |

| C. gloeosporioides | IMI 356878* | Citrus sinensis | Italy | JX010152 | JX010056 | JX009731 | JX009531 | JX009818 | JX010445 |

| ICMP 12939 | Citrus sp. | New Zealand | JX010149 | JX009931 | JX009728 | JX009462 | JX009747 | – | |

| ICMP 18695 | Citrus sp. | USA | JX010153 | JX009979 | JX009735 | JX009494 | JX009779 | – | |

| ICMP 18694 | Mangifera indica | South Africa | JX010155 | JX009980 | JX009729 | JX009481 | JX009796 | – | |

| C. gloeosporioides (syn. Gloeosporium pedemontanum) | ICMP 19121* | Citrus limon | Italy | JX010148 | JX010054 | JX009745 | JX009558 | JX009903 | – |

| C. godetiae | CBS 133.44* | Clarkia hybrida | Denmark | JQ948402 | JQ948733 | – | JQ949723 | JQ949063 | JQ950053 |

| C. hebeiense | JZB330024 | Vitis vinifera cv. Cabernet Sauvignon | China | KF156873 | KF377505 | – | KF377542 | – | – |

| CGMCC 3.17464* | Vitis vinifera cv. Cabernet Sauvignon | China | KF156863 | KF377495 | – | KF377532 | KF289008 | KF288975 | |

| C. hemerocallidis | CDLG5* | Hemerocallis fulva var. kwanso | China | JQ400005 | JQ400012 | – | JQ399991 | JQ399998 | JQ400019 |

| C. hippeastri | CBS 125376* | Hippeastrum vittatum, leaf | China | JQ005231 | JQ005318 | JQ005752 | JQ005579 | JQ005405 | JQ005665 |

| C. horii | ICMP 10492* | Diospyros kaki | Japan | GQ329690 | GQ329681 | JX009604 | JX009438 | JX009752 | JX010450 |

| C. insertae | MFLU 15-1895* | Parthenocissus inserta | Russia | KX618686 | KX618684 | – | KX618682 | KX618683 | KX618685 |

| C. jasminigenum | MFLUCC 10-0273 | Jasminum sambac | Vietnam | HM131513 | HM131499 | – | HM131508 | – | HM153770 |

| C. jiangxiense | CGMCC 3.17362 | Camellia sinensis, endophyte | China | KJ955198 | KJ954899 | KJ954749 | KJ954469 | – | KJ955345 |

| CGMCC 3.17363* | Camellia sinensis, pathogen | China | KJ955201 | KJ954902 | KJ954752 | KJ954471 | – | KJ955348 | |

| C. johnstonii | CBS 128532* | Solanum lycopersicum, fruit rot | New Zealand | JQ948444 | JQ948775 | – | JQ949765 | JQ949105 | JQ950095 |

| C. kahawae subsp. ciggaro | ICMP 18539* | Olea europaea | Australia | JX010230 | JX009966 | JX009635 | JX009523 | JX009800 | JX010434 |

| ICMP 18534 | Kunzea ericoides | New Zealand | JX010227 | JX009904 | JX009634 | JX009473 | JX009765 | JX010427 | |

| ICMP 12952 | Persea americana | New Zealand | JX010214 | JX009971 | JX009648 | JX009431 | JX009757 | JX010426 | |

| C. kahawae subsp. kahawae | IMI 319418* | Coffea arabica | Kenya | JX010231 | JX010012 | JX009642 | JX009452 | JX009813 | JX010444 |

| C. kahawae subsp. kahawae (cont.) | ICMP 17905 | Coffea arabica | Cameroon | JX010232 | JX010046 | JX009644 | JX009561 | JX009816 | JX010431 |

| ICMP 17915 | Coffea arabica | Angola | JX010234 | JX010040 | JX009638 | JX009474 | JX009829 | JX010435 | |

| C. karstii | CBS 113087 | Malus sp. | USA | JQ005181 | JQ005268 | JQ005702 | JQ005529 | JQ005355 | JQ005615 |

| CBS 128524 | Citrullus lanatus, rotten fruit | New Zealand | JQ005195 | JQ005282 | JQ005716 | JQ005543 | JQ005369 | JQ005629 | |

| CBS 128551 | Citrus sp. | New Zealand | JQ005208 | JQ005295 | JQ005729 | JQ005556 | JQ005382 | JQ005642 | |

| CBS 129832 | Musa sp. | Mexico | JQ005177 | JQ005264 | JQ005698 | JQ005525 | JQ005351 | JQ005611 | |

| CBS 129824 | Musa AAA, fruit | Colombia | JQ005215 | JQ005302 | JQ005736 | JQ005563 | JQ005389 | JQ005649 | |

| CBS 128552 | Synsepalum dulcificum, leaves | Taiwan | JQ005188 | JQ005275 | JQ005709 | JQ005536 | JQ005362 | JQ005622 | |

| C. kinghornii | CBS 198.35* | Phormium sp. | UK | JQ948454 | JQ948785 | – | JQ949775 | JQ949115 | JQ950105 |

| C. laticiphilum | CBS 112989* | Hevea brasiliensis | India | JQ948289 | JQ948619 | – | JQ949610 | JQ948950 | JQ949940 |

| C. ledebouriae | CBS 141284* | Ledebouria floridunda | South Africa | KX228254 | – | – | KX228357 | – | – |

| C. liaoningense | CGMCC 3.17616* | Capsicum sp. | China | KP890104 | KP890135 | – | KP890097 | KP890127 | KP890111 |

| C. lindemuthianum | CBS 144.31* | Phaseolus vulgaris | Germany | JQ005779 | JX546712 | – | JQ005842 | JQ005800 | JQ005863 |

| C. lineola | CBS 125337* | Apiaceae, dead stem | Czech Republic | GU227829 | GU228221 | – | GU227927 | GU228319 | GU228123 |

| CBS 124.25 | Trillium sp., leaf spot | Czech Republic | GU227836 | GU228228 | – | GU227934 | GU228326 | GU228130 | |

| C. lupini | CBS 109225* | Lupinus albus | Ulkraine | JQ948155 | JQ948485 | – | JQ949476 | JQ948816 | JQ949806 |

| C. magnum | CBS 519.97* | Citrullus lanatus | USA | MG600769 | MG600829 | – | MG600973 | MG600875 | MG601036 |

| C. menispermi | MFLU 14-0625* | Menispermum dauricum | Russia | KU242357 | KU242356 | – | KU242353 | KU242355 | KU242354 |

| C. musae | CBS 116870* | Musa sp. | USA | JX010146 | JX010050 | JX009742 | JX009433 | JX009896 | HQ596280 |

| C. musicola | CBS 132885* | Musa sp. | Mexico | MG600736 | MG600798 | – | MG600942 | MG600853 | MG601003 |

| C. neosansevieriae | CBS 139918* | Sansevieria trifasciata | South Africa | KR476747 | KR476791 | – | KR476790 | – | KR476797 |

| C. novae-zelandiae | CBS 128505* | Capsicum annuum, fruit rot | New Zealand | JQ005228 | JQ005315 | JQ005749 | JQ005576 | JQ005402 | JQ005662 |

| C. nupharicola | CBS 470.96* | Nuphar lutea subsp. Polysepala | USA | JX010187 | JX009972 | JX009663 | JX009437 | JX009835 | JX010398 |

| C. nymphaeae | CBS 515.78* | Nymphaea alba | Netherlands | JQ948197 | JQ948527 | – | JQ949518 | JQ948858 | JQ949848 |

| C. oncidii | CBS 129828* | Oncidium sp., leaf | Germany | JQ005169 | JQ005256 | JQ005690 | JQ005517 | JQ005343 | JQ005603 |

| C. orbiculare | CBS 514.97 | Cucumis sativus | Japan | JQ005778 | KF178491 | – | JQ005841 | JQ005799 | JQ005862 |

| C. orchidearum | CBS 135131* | Dendrobium nobile | Netherlands | MG600738 | MG600800 | – | MG600944 | MG600855 | MG601005 |

| C. orchidophilum | CBS 632.80* | Dendrobium sp. | USA | JQ948151 | JQ948481 | – | JQ949472 | JQ948812 | JQ949802 |

| C. paranaense | CBS 134729* | Malus domestica | Brazil, Parana | KC204992 | KC205026 | – | KC205077 | KC205043 | KC205060 |

| C. parsonsiae | CBS 128525 | Parsonsia capsularis, leaf endophyte | New Zealand | JQ005233 | JQ005320 | JQ005754 | JQ005581 | JQ005407 | JQ005667 |

| C. paxtonii | IMI 165753* | Musa sp. | Saint Lucia | JQ948285 | JQ948615 | – | JQ949606 | JQ948946 | JQ949936 |

| C. petchii | CBS 378.94* | Dracaena marginata, spotted leaves | Italy | JQ005223 | JQ005310 | JQ005744 | JQ005571 | JQ005397 | JQ005657 |

| C. phormii | CBS 118194* | Phormium sp. | Germany | JQ948446 | JQ948777 | – | JQ949767 | JQ949107 | JQ950097 |

| C. phyllanthi | CBS 175.67* | Phyllanthus acidus, anthracnose | India | JQ005221 | JQ005308 | JQ005742 | JQ005569 | JQ005395 | JQ005655 |

| C. piperis | IMI 71397* | Piper nigrum | Malaysia | MG600760 | MG600820 | – | MG600964 | MG600867 | MG601027 |

| C. plurivorum | CBS 125474* | Coffea sp. | Vietnam | MG600718 | MG600781 | – | MG600925 | MG600841 | MG600985 |

| CBS 125473 | Coffea sp. | Vietnam | MG600717 | MG600780 | – | MG600924 | MG600840 | MG600984 | |

| CGMCC 3.17358 | Camellia sinensis, endophyte | China | KJ955215 | KJ954916 | – | KJ954483 | – | KJ955361 | |

| CMM 3742 | Mangifera indica | Brazil | KC702980 | KC702941 | – | KC702908 | KC598100 | KC992327 | |

| LJTJ30 | Capsicum annuum | China | KP748221 | KP823800 | – | KP823741 | – | KP823853 | |

| MAFF 243073 | Amorphophallus rivieri | Japan | MG600730 | MG600793 | – | MG600936 | MG600847 | MG600997 | |

| MAFF 305790 | Musa sp. | Japan | MG600726 | MG600789 | – | MG600932 | MG600845 | MG600993 | |

| C. psidii | CBS 145.29* | Psidium sp. | Italy | JX010219 | JX009967 | JX009743 | JX009515 | JX009901 | JX010443 |

| C. pyricola | CBS 128531* | Pyrus communis, fruit rot | New Zealand | JQ948445 | JQ948776 | – | JQ949766 | JQ949106 | JQ950096 |

| C. queenslandicum | ICMP 1778* | Carica papaya | Australia | JX010276 | JX009934 | JX009691 | JX009447 | JX009899 | JX010414 |

| C. quinquefoliae | MFLU 14-0626* | Parthenocissus quinquefolia | Russia | KU236391 | KU236390 | – | KU236389 | – | KU236392 |

| C. rhexiae | CBS 133134* | Rhexia virginica | USA | JX145128 | – | – | – | – | JX145179 |

| C. rhexiae (cont.) | CBS 133132 | Vaccinium macrocarpon | USA | JX145157 | – | – | – | – | JX145209 |

| C. rhombiforme | CBS 129953* | Olea europaea | Portugal | JQ948457 | JQ948788 | – | JQ949778 | JQ949118 | JQ950108 |

| C. salicis | CBS 607.94* | Salix sp., leaf, spot | Netherlands | JQ948460 | JQ948791 | JQ949781 | JQ949121 | JQ950111 | – |

| C. salsolae | ICMP 19051* | Salsola tragus | Hungary | JX010242 | JX009916 | JX009696 | JX009562 | JX009863 | JX010403 |

| C. sansevieriae | MAFF 239721* | Sansevieria trifasciata | Japan | AB212991 | – | – | – | – | – |

| C. sedi | MFLUCC 14-1002* | Sedum sp. | Russia | KM974758 | KM974755 | – | KM974756 | KM974754 | KM974757 |

| C. siamense | ICMP 18578* | Coffea arabica | Thailand | JX010171 | JX009924 | FJ917505 | FJ907423 | JX009865 | JX010404 |

| ICMP 12567 | Persea americana | Australia | JX010250 | JX009940 | JX009697 | JX009541 | JX009761 | JX010387 | |

| ICMP 18574 | Pistacia vera | Australia | JX010270 | JX010002 | JX009707 | JX009535 | JX009798 | JX010391 | |

| ICMP 18121 | Dioscorea rotundata | Nigeria | JX010245 | JX009942 | JX009715 | JX009460 | JX009845 | JX010402 | |

| ICMP 17795 | Malus domestica | USA | JX010162 | JX010051 | JX009703 | JX009506 | JX009805 | JX010393 | |

| C. siamense (syn. C. hymenocallidis) | ICMP 18642* | Hymenocallis americana | China | JX010278 | JX010019 | JX009709 | GQ856775 | GQ856730 | JX010410 |

| C. siamense (syn. C. jasmini-sambac) | ICMP 19118* | Jasminum sambac | Vietnam | HM131511 | HM131497 | JX009713 | HM131507 | JX009895 | JX010415 |

| C. simmondsii | CBS 122122* | Carica papaya | Australia | JQ948276 | JQ948606 | – | JQ949597 | JQ948937 | JQ949927 |

| C. sloanei | IMI 364297* | Theobroma cacao, leaf | Malaysia | JQ948287 | JQ948617 | – | JQ949608 | JQ948948 | JQ949938 |

| C. sojae | ATCC 62257* | Glycine max | USA | MG600749 | MG600810 | – | MG600954 | MG600860 | MG601016 |

| CGMCC 3.15171 | Bletilla ochracea | China | HM751813 | KC843501 | – | KC843550 | – | KC244161 | |

| C. sonchicola | JZB330117 | Sonchus sp. | Italy | KY962756 | KY962753 | – | KY962747 | KY962750 | – |

| MFLUCC 17-1300 | Sonchus sp. | Italy | KY962758 | KY962755 | – | KY962749 | KY962752 | – | |

| C. spinaciae | CBS 128.57 | Spinacia oleracea | Netherlands | GU227847 | GU228239 | – | GU227945 | GU228337 | GU228141 |

| C. sydowii | CBS 135819 | Sambucus sp. | China, Taiwan | KY263783 | KY263785 | – | KY263791 | KY263787 | KY263793 |

| C. tamarilloi | CBS 129814* | Solanum betaceum, fruit, anthracnose | Colombia | JQ948184 | JQ948514 | – | JQ949505 | JQ948845 | JQ949835 |

| C. temperatum | CBS 133122* | Vaccinium macrocarpon | USA | JX145159 | – | – | – | – | JX145211 |

| CBS 133120 | Vaccinium macrocarpon | USA | JX145135 | – | – | – | – | JX145186 | |

| C. theobromicola | CBS 124945* | Theobroma cacao | Panama | JX010294 | JX010006 | JX009591 | JX009444 | JX009869 | JX010447 |

| C. ti | ICMP 4832* | Cordyline sp. | New Zealand | JX010269 | JX009952 | JX009649 | JX009520 | JX009898 | JX010442 |

| C. torulosum | CBS 128544* | Solanum melongena | New Zealand | JQ005164 | JQ005251 | JQ005685 | JQ005512 | JQ005338 | JQ005598 |

| C. tropicale | CBS 124949* | Theobroma cacao | Panama | JX010264 | JX010007 | JX009719 | JX009489 | JX009870 | JX010407 |

| C. tropicicola | BCC 38877* | Citrus maxima | Thailand | JN050240 | JN050229 | – | JN050218 | – | JN050246 |

| MFLUCC100167 | Paphiopedilum bellatolum | Thailand | JN050241 | JN050230 | – | JN050219 | – | JN050247 | |

| C. truncatum | CBS 151.35* | Phaseolus lunatus | USA | GU227862 | GU228254 | – | GU227960 | GU228352 | GU228156 |

| C. viniferum | GZAAS 5.08601* | Vitis vinifera cv. Shuijing | China | JN412804 | JN412798 | JQ309639 | JN412795 | – | JN412813 |

| C. vittalense | CBS 181.82* | Theobroma cacao | India | MG600734 | MG600796 | – | MG600940 | MG600851 | MG601001 |

| C. walleri | CBS 125472* | Coffea sp., leaf tissue | Vietnam | JQ948275 | JQ948605 | – | JQ949596 | JQ948936 | JQ949926 |

| C. wuxiense | CGMCC 3.17894* | Camellia sinensis | China | KU251591 | KU252045 | KU251833 | KU251672 | KU251939 | KU252200 |

| JS1A44 | Camellia sinensis | China | KU251592 | KU252046 | KU251834 | KU251673 | KU251940 | KU252201 | |

| C. xanthorrhoeae | ICMP 17903* | Xanthorrhoea preissii | Australia | JX010261 | JX009927 | JX009653 | JX009478 | JX009823 | JX010448 |

| C. yunnanense | CBS 132135* | Buxus sp. | China | JX546804 | JX546706 | – | JX519239 | JX519231 | JX519248 |

| Colletotrichum sp. | CGMCC 3.15172 | Bletilla ochracea | China | HM751816 | KC843522 | – | KC843547 | – | KC244162 |

| Q026 | Rubus glaucus | Colombia | JN715839 | KC860013 | – | KC859970 | KC859995 | KC860039 | |

| Glomerella cingulata ‘f. sp. camelliae’ | ICMP 10643 | Camellia × williamsii | UK | JX010224 | JX009908 | JX009630 | JX009540 | JX009891 | JX010436 |

| Monilochaetes infuscans | CBS 869.96* | Ipomoea batatas | South Africa | JQ005780 | JX546612 | – | JQ005843 | JQ005801 | JQ005864 |

x ATCC: American Type Culture Collection; BCC: BIOTEC Culture Collection, National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (BIOTEC), Khlong Luang, Pathumthani, Thailand; BRIP: Plant Pathology Herbarium, Department of Employment, Economic, Development and Innovation, Queensland, Australia; CBS: Culture collection of the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Utrecht, The Netherlands; CGMCC: China General Microbiological Culture Collection; CMM: Culture Collection of Phytopathogenic Fungi Prof. Maria Menezes, Federal Rural University of Pernambuco, Brazil; COAD: Coleção Octávio Almeida Drummond, Viçosa, Brazil; GZAAS: Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences Herbarium, China; ICMP: International Collection of Microorganisms from Plants, Auckland, New Zealand; IMI: Culture collection of CABI Europe UK Centre, Egham, UK; MAFF: MAFF Genebank Project, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Tsukuba, Japan; MFLU: Herbarium of Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, Thailand; MFLUCC: Mae Fah Luang University Culture Collection, Chiang Rai, Thailand.

* = ex-type culture.

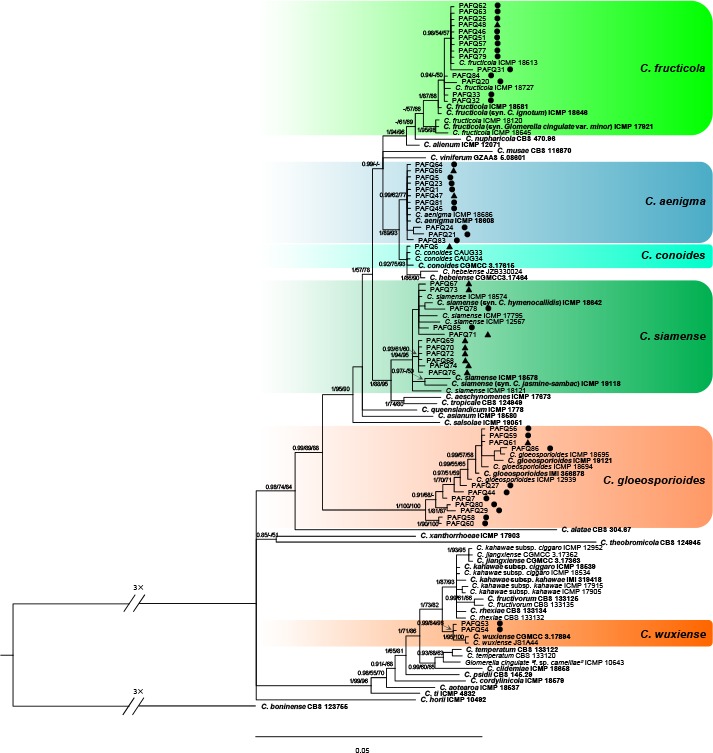

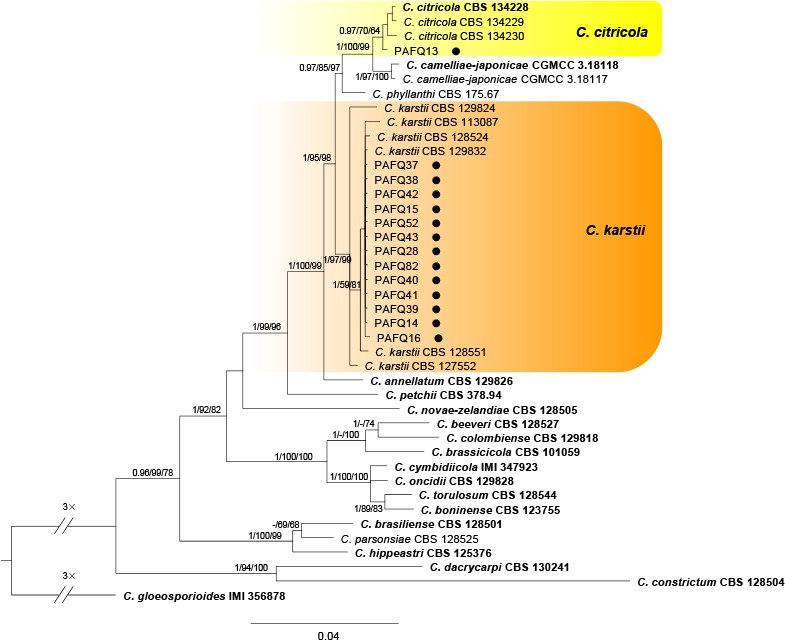

Fig. 2.

A Bayesian inference phylogenetic tree of 111 isolates in the C. gloeosporioides species complex. The species C. boninense (CBS 123755) was selected as an outgroup. The tree was built using concatenated sequences of the ACT, TUB2, CAL, CHS-1, GAPDH, and ITS genes. Bayesian posterior probability (PP ≥ 0.90), MP bootstrap support values (ML ≥ 50 %), and RAxML bootstrap support values (ML ≥ 50 %) were shown at the nodes (PP/MP/ML). Ex-type isolates are in bold. Coloured blocks indicate clades containing isolates from Pyrus spp. in this study; circles indicate isolates isolated from leaves, triangles indicate isolates isolated from fruits. The scale bar indicates 0.05 expected changes per site.

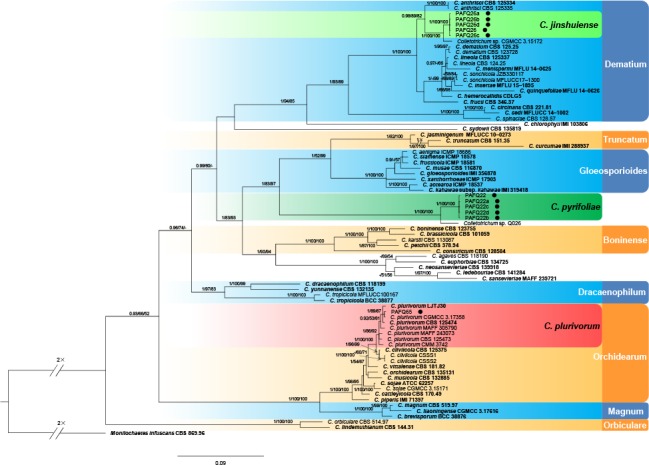

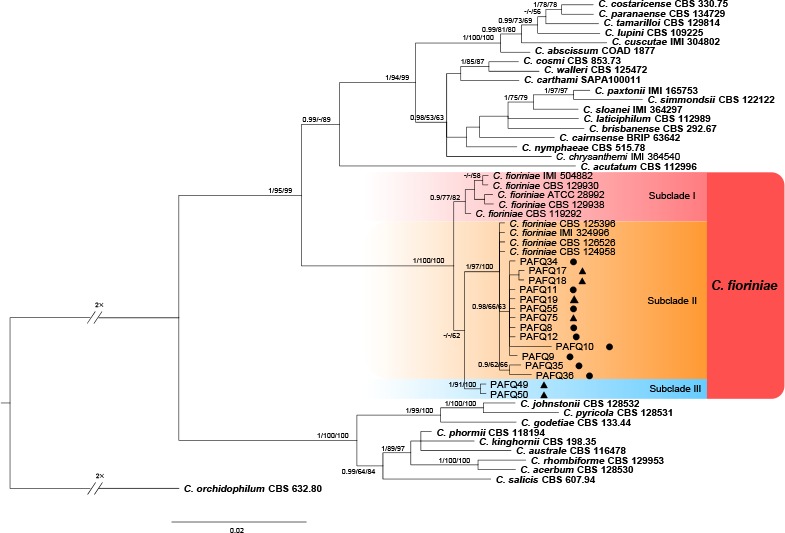

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic tree generated by Bayesian inference based on concatenated sequences of the ACT, CHS-1, GAPDH, ITS, and TUB genes. Monilochaetes infuscans (CBS 869.96) was selected as an outgroup. Bayesian posterior probability (PP ≥ 0.90), MP bootstrap support values (ML ≥ 50 %), and RAxML bootstrap support values (ML ≥ 50 %) were shown at the nodes (PP/MP/ML). Ex-type isolates are in bold. Coloured blocks are used to indicate clades containing isolates from Pyrus spp. in this study; circles indicate isolates isolated from leaves. The scale bar indicates 0.09 expected changes per site.

In the phylogenetic tree constructed for the isolates in the C. gloeosporioides species complex, 50 isolates clustered in six clades corresponding to C. fructicola (14 isolates), C. aenigma (11), C. siamense (11), C. gloeosporioides (11), C. wuxiense (2), and C. conoides (1) (Fig. 2). For the isolates in the C. acutatum species complex, 13 isolates grouped in subclade II of C. fioriniae (Bayesian posterior probabilities value 1/PAUP bootstrap support value 97/RAxML bootstrap support value 100) as defined in a previous study (Damm et al. 2012b), while two isolates (PAFQ49 and PAFQ50) formed a further subclade, which is designated as subclade III (Fig. 3). For isolates in the C. boninense species complex, 13 isolates clustered with C. karstii, and one with C. citricola (Fig. 4). For the remaining 11 isolates, PAFQ65 clustered with C. plurivorum (1/86/92), while five isolates formed a distinct clade (1/100/100) as sister to Colletotrichum sp. isolate CGMCC 3.15172 in the C. dematium species complex. In addition, the remaining five isolates, which formed a distinct clade (1/100/100), clustered distantly from any known Colletotrichum species complex (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

A Bayesian inference phylogenetic tree of 51 isolates in the C. acutatum species complex. The species C. orchidophilum (CBS 632.80) was selected as an outgroup. The tree was built using concatenated sequences of the ACT, TUB2, CHS-1, GAPDH, and ITS genes. Bayesian posterior probability (PP ≥ 0.90), MP bootstrap support values (ML ≥ 50 %), and RAxML bootstrap support values (ML ≥ 50 %) were shown at the nodes (PP/MP/ML). Ex-type isolates are in bold. Coloured blocks indicate clades containing isolates from Pyrus spp. in this study; circles indicate isolates isolated from leaves, triangles indicate isolates isolated from fruits. The scale bar indicates 0.02 expected changes per site.

Fig. 4.

A Bayesian inference phylogenetic tree of 41 isolates in the C. boninense species complex. The species C. gloeosporioides (IMI 356878) was selected as an outgroup. The tree was built using concatenated sequences of the ACT, TUB2, CAL, CHS-1, GAPDH, and ITS genes. Bayesian posterior probability (PP ≥ 0.90), MP bootstrap support values (ML ≥ 50 %), and RAxML bootstrap support values (ML ≥ 50 %) were shown at the nodes (PP/MP/ML). Ex-type isolates are in bold. Coloured blocks indicate clades containing isolates from Pyrus spp. in this study; circles indicate isolates isolated from leaves. The scale bar indicates 0.04 expected changes per site.

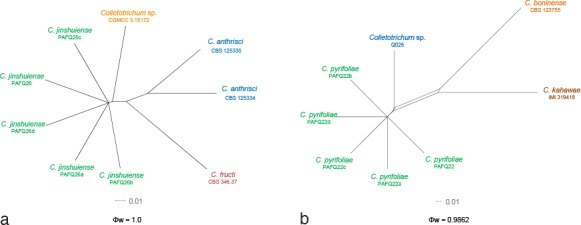

To exclude the possibility that species delimitation might be interfered by recombination among the genes used for phylogenetic analyses, the multi-locus (ACT, TUB2, CHS-1, GAPDH, and ITS) concatenated datasets were subjected to two PHI tests (Fig. 6) to determine the recombination level within phylogenetically closely related species. The results showed that no significant recombination events were observed between C. jinshuiense and phylogenetically related isolates or species (Colletotrichum sp. isolate CGMCC 3.15172, C. anthrisci and C. fructi) (Fig. 6a), and between C. pyrifoliae and phylogenetically related isolates or species (Colletotrichum sp. isolate Q026, C. boninense and C. kahawae) (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

The result of the pairwise homoplasy index (PHI) tests of closely related species using both LogDet transformation and splits decomposition. a, b. The PHI of C. jinshuiense (a) or C. pyrifoliae (b) and their phylogenetically related isolates or species, respectively. PHI test value (Φw) < 0.05 indicate significant recombination within the dataset.

Taxonomy

Based on morphology and multi-locus sequence data, the 90 isolates were assigned to 12 Colletotrichum spp. Of these, two species proved to represent new taxa that are described below. Six species are reported from pear for the first time. Eight species formed sexual morphs in vitro.

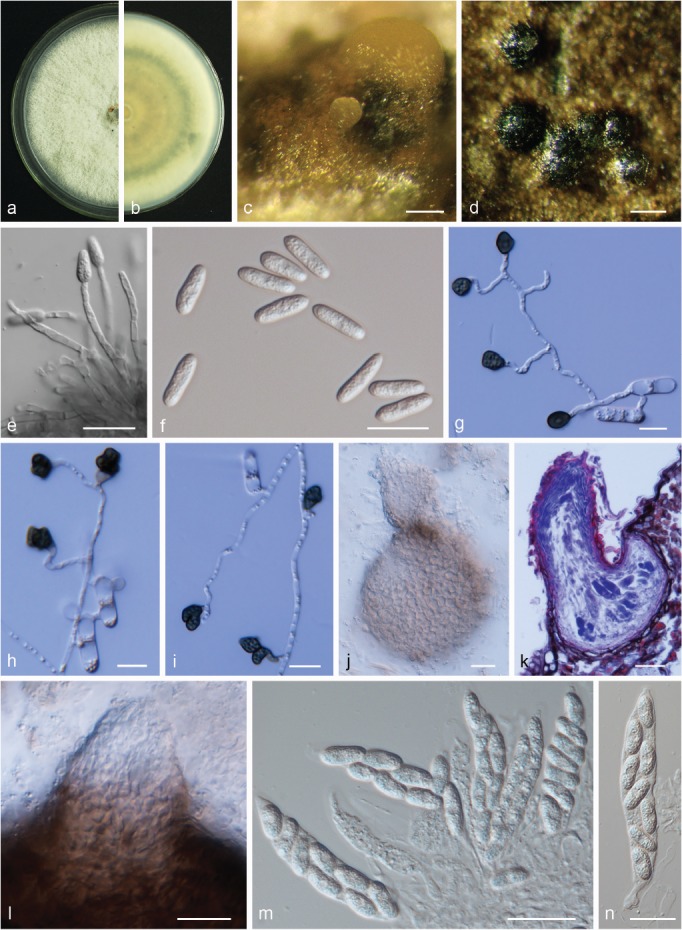

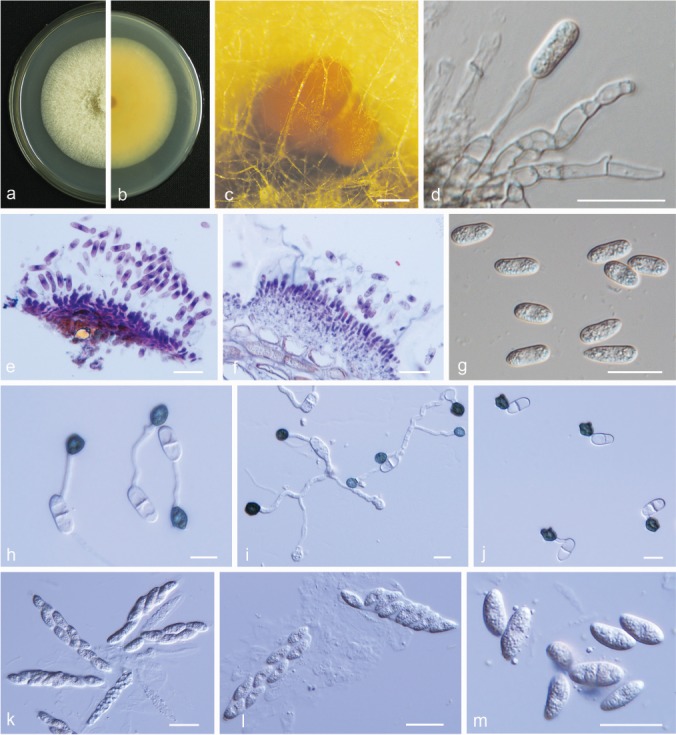

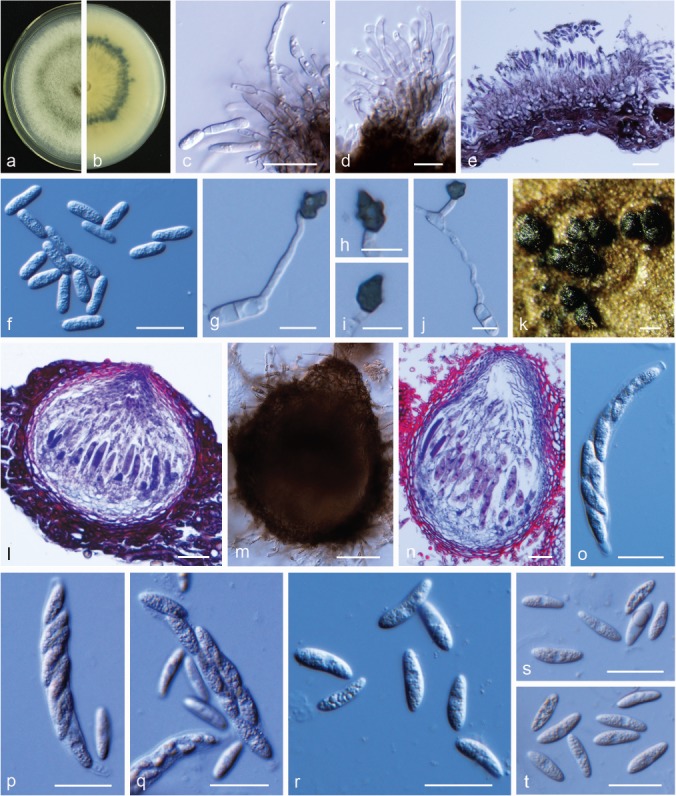

Colletotrichum aenigma B.S. Weir & P.R. Johnst., Stud. Mycol. 73: 135. 2012. — Fig. 7

Fig. 7.

Colletotrichum aenigma. a, b. Front and back view, respectively, of 6-d-old PDA culture; c. conidiomata; d. conidiophores; e. seta; f. section view of acervulus produced on pear leaf (P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan); g. conidia; h, i. appressoria; j. ascomata produced on pear leaf (P. bretschneideri cv. Dangshansuli); k. section view of ascoma produced on pear leaf (P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan); l. ascomata; m. outer surface of peridium; n, o. asci; p, q. ascospores (a–c, i–m. isolate PAFQ1; d–h. isolate PAFQ47; n, p. isolate PAFQ3; o, q. isolate PAFQ2; a–e, g, l–q produced on PDA agar medium). — Scale bars: c, l = 500 μm; d–g, k, m–q = 20 μm; h, i =10 μm; j = 100 μm.

Description & Illustration — Weir et al. (2012), Wang et al. (2016).

Materials examined. CHINA, Hubei Province, Zhongxiang City, on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Xiangnan, 1 Sept. 2015, M. Fu (culture PAFQ1); ibid., on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Huanghua, 1 Sept. 2015, M. Fu (PAFQ3); ibid., on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Huali No.1, 1 Sept. 2015, M. Fu (PAFQ5); Jiangsu Province, Yancheng City, on fruits of P. bretschneideri cv. Renli, 1 Sept. 2015, M. Fu (PAFQ47); ibid., on leaves of P. bretschneideri cv. Yali, 1 Sept. 2015, M. Fu (PAFQ45); Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou City, on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Guanyangxueli, 18 Aug. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ81); Anhui Province, Dangshan County, on fruits of P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan, 4 Aug. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ66).

Notes — A total of 40 isolates were collected. Colletotrichum aenigma has been reported to cause anthracnose diseases of P. pyrifolia from Japan (Weir et al. 2012), and P. communis from Italy (Schena et al. 2014). This is the first report of C. aenigma causing anthracnose on P. bretschneideri and on Pyrus in China.

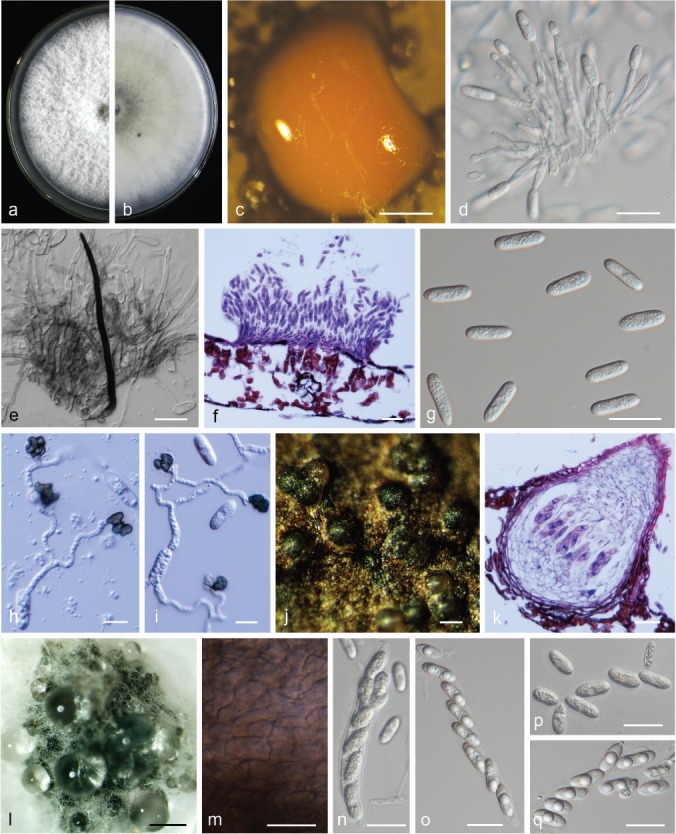

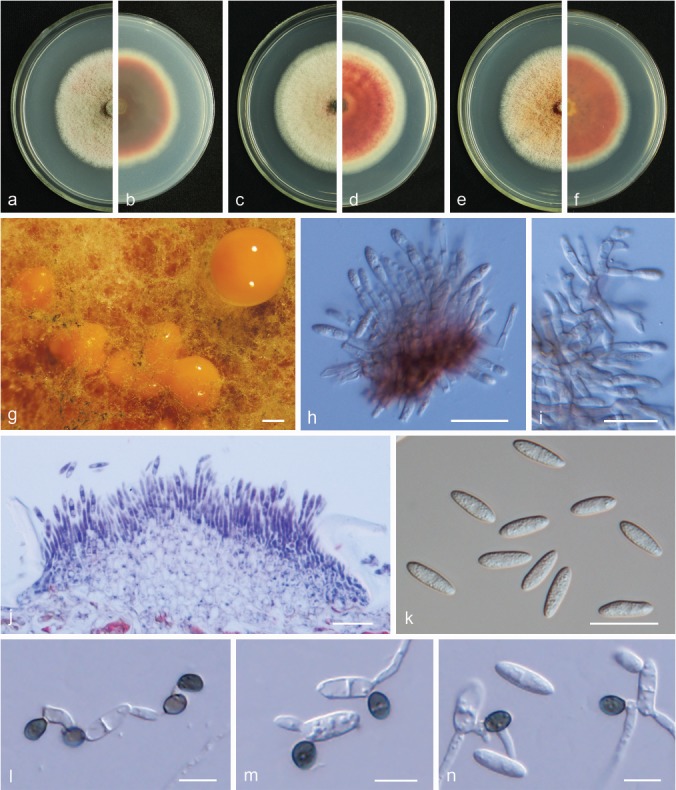

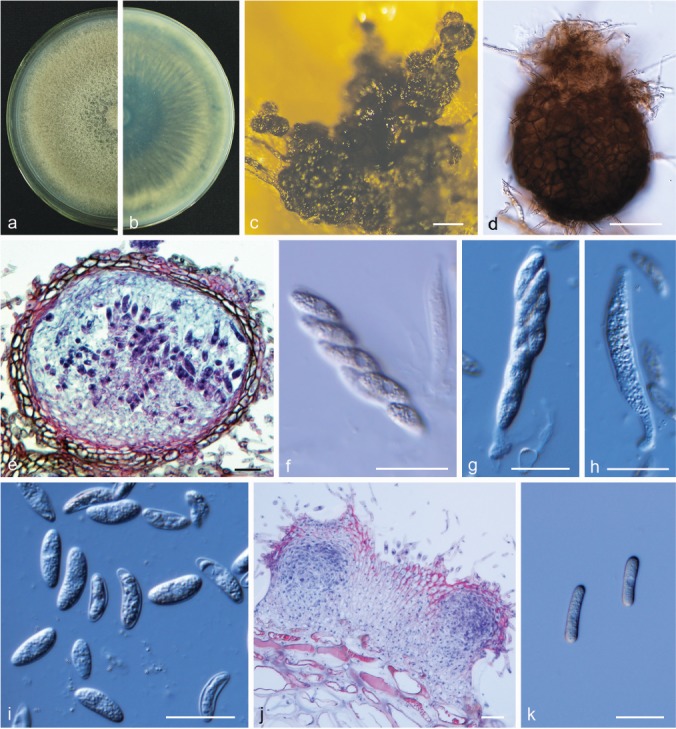

Colletotrichum citricola F. Huang et al., Fung. Diversity 61: 67. 2013. — Fig. 8

Fig. 8.

Colletotrichum citricola. a, b. Front and back view, respectively of 6-d-old PDA culture; c, d. conidiomata; e–g. conidiophores; h. section view of acervulus produced on pear leaf (P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan); i. conidia; j, k. appressoria; l. ascoma; m, n. asci; o. ascospores (a–o. isolate PAFQ13; a–c, e–g, i, l–o. produced on PDA agar medium, d. produced on pear leaf (P. bretschneideri cv. Dangshansuli)). — Scale bars: d = 100 μm; e–i, l–o = 20 μm; j, k = 10 μm.

Description & Illustration — Huang et al. (2013).

Materials examined. CHINA, Hubei Province, Wuhan City, on leaves of P. pyrifolia, 1 Sept. 2015, P.F. Zhang (culture PAFQ13).

Notes — Colletotrichum citricola was first reported as a saprobe from Citrus unshiu in China (Huang et al. 2013). Isolate PAFQ13 was isolated from pear leaves, and clustered together with the ex-type culture of C. citricola (CBS 134228) in the multi-locus phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4). This is the first report of C. citricola causing anthracnose on P. pyrifolia.

Ascospores of the isolate PAFQ13 (13.5–20 × 5–8 μm, mean ± SD = 17.4 ± 1.4 × 7.1 ± 0.7 μm) are slightly larger than those of the ex-type isolate CBS 134228 (12.8–18.4 × 5.3–6.7 μm, mean = 15.8 × 6.1 μm) of C. citricola. Setae were observed in the acervuli formed on pear leaves, being brown, smooth-walled, 2-septate, 41–84 μm long, base rounded, 6 μm diam, tip more or less acute.

Colletotrichum conoides Y.Z. Diao et al., Persoonia 38: 27. 2017. — Fig. 9

Fig. 9.

Colletotrichum conoides. a, b. Front and back view, respectively, of 6-d-old PDA culture; c. conidiomata; d. ascomata produced on pear leaf (P. bretschneideri cv. Dangshansuli); e. conidiophores; f. conidia; g–i. appressoria; j. ascoma; k. section view of ascoma produced on pear leaf (P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan); l. neck of ascoma; m, n. asci (a–n. isolate PAFQ6; a–c, e, f, j, l–n. produced on PDA agar medium). — Scale bars: c, d = 100 μm; e, f, j–n = 20 μm; g–i =10 μm.

Sexual morph developed on PDA. Ascomata ovoid to obpyriform, light to dark brown, 77–180 × 69–159 μm, ostiolate. Asci cylindrical to clavate, 59.5–99 × 13.5–18.5 μm, 8-spored. Ascospores hyaline, smooth-walled, aseptate, cylindrical, sometimes slightly curved, both sides rounded, contents granular, 12.5–21 × 5.5–7.5 μm, mean ± SD = 15.9 ± 1.3 × 6.8 ± 0.5 μm, L/W ratio = 2.3.

Asexual morph developed on PDA. Conidiophores hyaline, smooth-walled, septate, branched. Conidiogenous cells hyaline, cylindrical to clavate, 18–34.5 × 2–3 μm. Conidia hyaline, aseptate, smooth-walled, cylindrical, both ends round or one end slightly acute, usually broader towards one side, contents granular, 16–20 × 4.5–6 μm, mean ± SD = 18.4 ± 0.8 × 5.6 ± 0.3 μm, L/W ratio = 3.3. Appressoria dark brown, irregular, but often square to ellipsoid in outline, the margin lobate, 7–12.5 × 5–8.5 μm, mean ± SD = 9.7 ± 1.3 × 6.9 ± 1.1 μm, L/W ratio = 1.4.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA flat with entire margin, aerial mycelium white, cottony, dense; reverse light grey in the centre and pale white margin, olivaceous coloured pigments formed in the shape of a concentric ring pattern; colony diam 77–78 mm in 5 d. Conidia in mass orange.

Materials examined. CHINA, Hubei Province, Wuhan City, on fruits of P. pyrifolia, 1 Sept. 2015, M. Fu (culture PAFQ6).

Notes — Colletotrichum conoides was first reported on Capsicum annuum (chili) from China (Diao et al. 2017). In the present study, one isolate (PAFQ6) from pear fruit clustered together with the ex-type culture of C. conoides (CGMCC 3.17615) in the multi-locus phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2). This is the first report of C. conoides to cause anthracnose on P. pyrifolia and the first description of its sexual morph.

Conidia of the isolate PAFQ6 (16–20 × 4.5–6 μm, mean ± SD = 18.4 ± 0.8 × 5.6 ± 0.3 μm) are longer than those of the ex-type isolate CGMCC 3.17615 (13–17.5 × 5–6.5 μm, mean = 15.9 × 5.9 μm) of C. conoides.

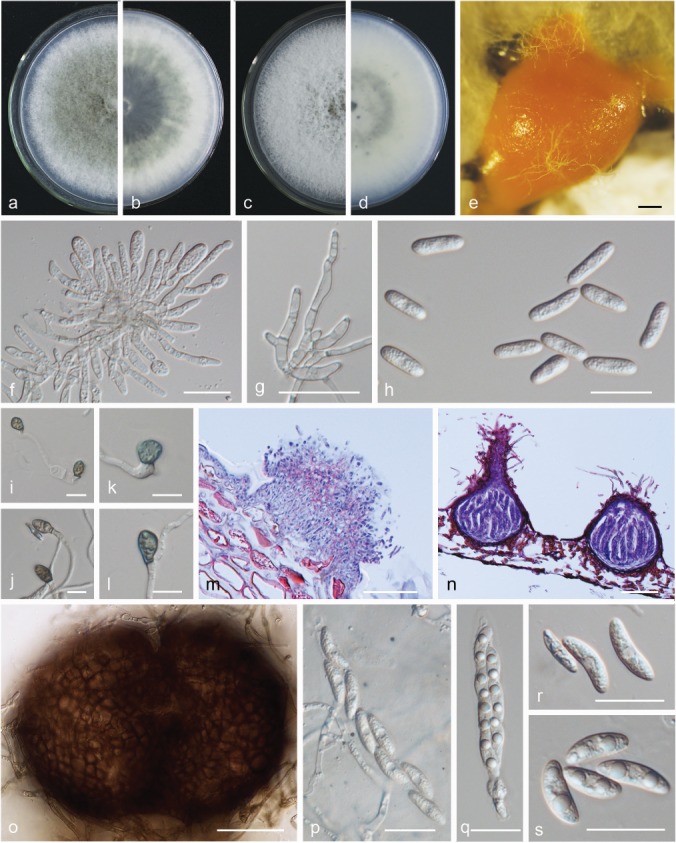

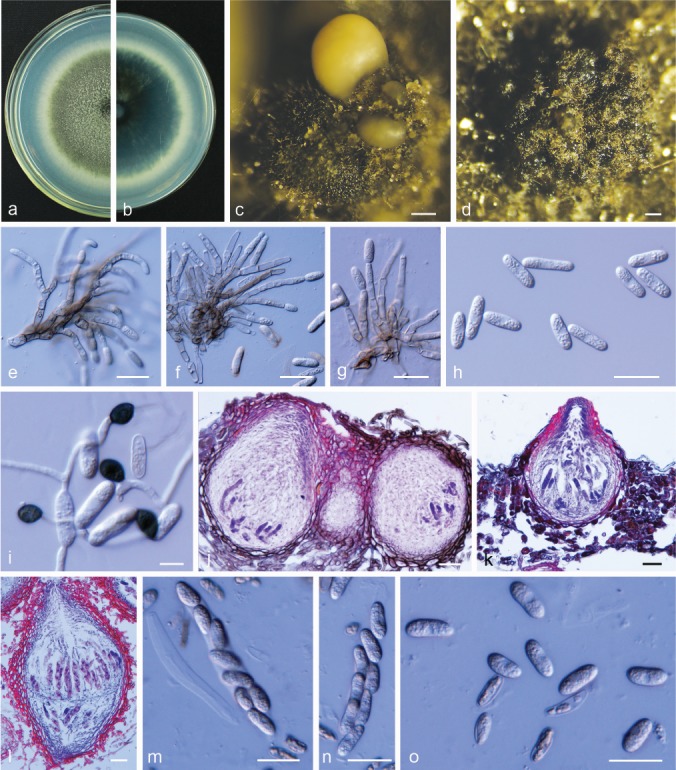

Colletotrichum fioriniae (Marcelino & Gouli) Pennycook,

Mycotaxon 132: 150. 2017. — Fig. 10

Fig. 10.

Colletotrichum fioriniae. a, c, e. Front views of 6-d-old PDA culture; b, d, f. back views of 6-d-old PDA culture; g. conidiomata; h, i. conidiophores; j. section view of acervulus produced on pear fruit (P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan); k. conidia; l–n. appressoria (a, b, g–l. isolate PAFQ8, c, d, m. isolate PAFQ36, e, f, n. isolate PAFQ49; a–i, k produced on PDA agar medium). — Scale bars: g = 400 μm; h–k = 20 μm; l–n = 10 μm.

Description & Illustration — Damm et al. (2012b).

Materials examined. CHINA, Hubei Province, Wuhan City, on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui No. 1, 1 Sept. 2015, M. Fu (cultures PAFQ8 and PAFQ9); ibid., on fruits of P. pyrifolia, 1 Aug. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ17); Fujian Province, Jianning County, on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, 1 Apr. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ35, PAFQ36); Jiangxi Province, Jinxi County, on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, 23 July 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ55); Shandong Province, Yantai City, on fruits of P. communis cv. Gyuiot, 27 Aug. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ75); Jiangsu Province, Nanjing City, on leaves of P. pyrifolia, 20 Aug. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ49).

Notes — Colletotrichum fioriniae was first reported on Persea americana and Acacia acuminata from Australia (Shivas & Tan 2009) and also caused fruit rot on Pyrus sp. in the USA (Damm et al. 2012b). In the study of Damm et al. (2012b), isolates clustered in two subclades, here designated as I and II. In the current study, an additional subclade (III) was detected (Fig. 3), which differs from subclade I in 2–3 bp in ACT, 1 bp in CHS, 1 bp in GAPDH, and 1 bp in TUB2, and subclade II in 3 bp in CHS, 4 bp in GAPDH, and 2 bp in TUB2.

Colletotrichum fructicola Prihast. et al., Fung. Diversity 39: 96. 2009. — Fig. 11

Fig. 11.

Colletotrichum fructicola. a, c. Front views of 6-d-old PDA culture; b, d. back views of 6-d-old PDA culture; e. conidiomata; f, g. conidiophores; h. conidia; i–l. appressoria; m. section view of acervulus produced on pear fruit (P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan); n. section view of ascomata produced on pear leaf (P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan); o. ascomata; p, q. asci; r, s. ascospores (a, b, h–l, o, q, r. isolate PAFQ31, c–e, m, n. isolate PAFQ32, p, s. isolate PAFQ48, f, g. isolate PAFQ30; a–h, o–s produced on PDA agar medium). — Scale bars: e = 500 μm; f–h, p–s = 20 μm; i–l = 10 μm; m–o = 50 μm.

Description & Illustration — Prihastuti et al. (2009).

Materials examined. CHINA, Fujian Province, Jianning County, on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, Apr. 2014, P.F. Zhang (cultures PAFQ30 and PAFQ31); ibid., 1 Sept. 2015, M. Fu (PAFQ32, PAFQ33); Jiangxi Province, Jinxi County, on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, 23 July 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ88); Hubei Province, Wuhan City, on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Jingshui, 1 Aug. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ20, PAFQ25); Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou City, on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Guanyangxueli, 18 Aug. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ79); ibid., Tonglu County, on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, 18 Aug. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ84); Jiangsu Province, Yancheng City, on fruits of P. bretschneideri cv. Dangshanshuli, 1 Sept. 2015, M. Fu (PAFQ48); ibid., on leaves of P. bretschneideri cv. Yali, 1 Sept. 2015, M. Fu (PAFQ46); Anhui Province, Dangshan County, on leaves of P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan, 4 Aug. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ62); ibid., on fruits of P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan, 4 Aug. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ90).

Notes — Colletotrichum fructicola was first reported on Coffea arabica in Thailand (Prihastuti et al. 2009), and subsequently reported on Pyrus pyrifolia in Japan (Weir et al. 2012), Citrus reticulata in China (Huang et al. 2013), Pyrus bretschneideri in China (Li et al. 2013), and other plants (e.g., Lima et al. 2013, Liu et al. 2015, Diao et al. 2017). The species was identified as responsible for pear anthracnose, causing TS symptoms on P. pyrifolia leaves (Zhang et al. 2015) and P. bretschneideri fruits in China (Jiang et al. 2014).

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Penz.) Penz. & Sacc., Atti Reale Ist. Veneto Sci. Lett. Arti., ser. 6, 2: 670. 1884. — Fig. 12

Fig. 12.

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. a, c, e. Front views of 6-d-old PDA culture; b, d, f. back views of 6-d-old PDA culture; g. conidiomata; h. conidiophores; i. section view of acervulus produced on pear fruit (P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan); j–l. conidia; m–p. appressoria (a, b, j, m. isolate PAFQ80, c, d, k, n. isolate PAFQ7, e–i, l, o, p. isolate PAFQ56; a–h, j–l produced on PDA agar medium). — Scale bars: g = 200 μm; h–l = 20 μm; m–p = 10 μm.

Description & Illustration — Cannon et al. (2008), Liu et al. (2015).

Materials examined. CHINA, Jiangxi Province, Jinxi County, on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan, 23 July 2016, M. Fu (culture PAFQ56); ibid., on fruits of P. pyrifolia cv. Huanghua, 23 July 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ61); Hubei Province, Wuhan City, on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Hohsui, 1 Aug. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ27); ibid., on leaves of P. bretschneideri cv. Huangxianchangba, 1 Sept. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ7); Jiangsu Province, Yancheng City, on leaves of P. bretschneideri cv. Yali, 1 Sept. 2015, M. Fu (PAFQ44); Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou City, on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Guanyangxueli, 18 Aug. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ80); ibid., on leaves of Pyrus sp., 18 Sept. 2016, M. Fu (PAFQ86).

Notes — Although C. gloeosporioides has been identified as responsible for pear anthracnose in China, these identifications were chiefly based on morphology and/or ITS sequence data (Wu et al. 2010, Liu et al. 2013b). In this study, 20 isolates of C. gloeosporioides isolated from fruits and leaves of pear were identified as C. gloeosporioides based on multi-loci phylogenetic analyses and confirmed as responsible for pear anthracnose following Koch’s postulates.

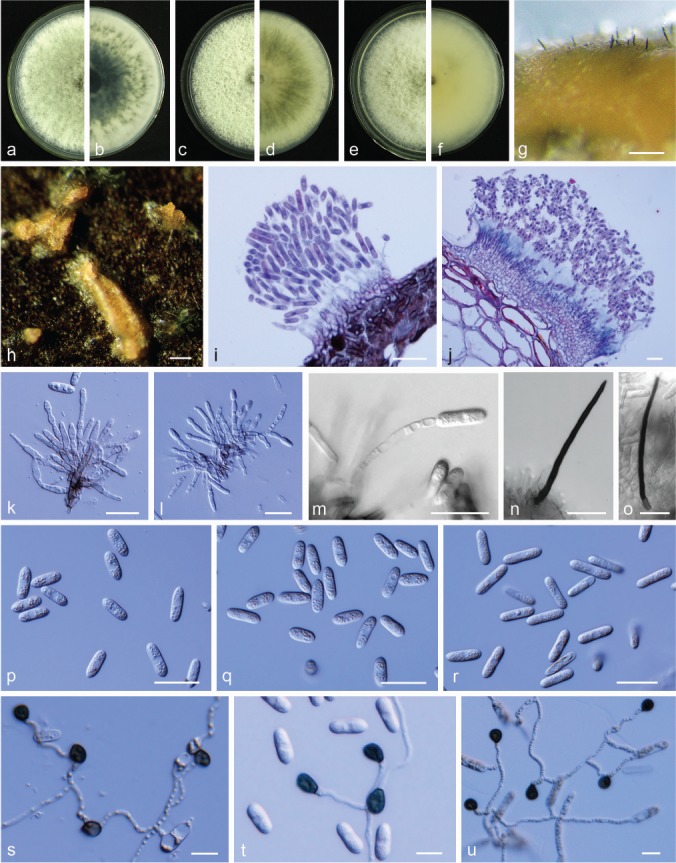

Colletotrichum jinshuiense M. Fu & G.P. Wang, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB824216; Fig. 13

Fig. 13.

Colletotrichum jinshuiense. a, b. Front and back view, respectively, of 6-d-old PDA culture; c. acervuli produced on pear leaf (P. bretschneideri cv. Dangshansuli); d. acervuli produced on pear fruit; e, f. section view of acervulus produced on pear leaf and fruit, respectively; g, h. conidiophores; i. setae; j, k. conidia; l, m. appressoria (a–m. isolate PAFQ26; a, b. produced on PDA agar medium; c, e, j, l. from pear leaf (P. pyrifoliae cv. Cuiguan), d, f–i, k–m. from pear fruit (P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan)). — Scale bars: c = 200 μm; d = 100 μm; e–k = 20 μm; l, m = 10 μm.

Etymology. Referring to the host variety (P. pyrofolia cv. Jinshui) from which the fungus was isolated.

Sexual morph not observed. Asexual morph on pear leaves and fruit. Conidiomata acervular, conidiophores and setae formed from a brown stroma. Setae dark brown to black, opaque, tip acute, base cylindrical, 1–4-septate, 59–363 (on leaf surface) and 70–272 μm long (on fruit surface). Conidiophores pale brown to hyaline, simple to 2-septate, unbranched. Conidiogenous cells (on fruit surface) hyaline, smooth-walled, cylindrical, 12.5–27 × 3.5–4.5 μm, opening 1–2 μm. Conidia, hyaline, smooth-walled, aseptate, curved, base subtruncate, apex acute, contents with 1–2 guttules, on leaf surface: 25–29.5 × 3.5–4.5 μm, mean ± SD = 27.1 ± 1.7 × 4.0 ± 0.3 μm, L/W ratio = 6.8; on fruit surface: 21–30.5 × 3–4.5 μm, mean ± SD = 24.4 ± 2.1 × 4.0 ± 0.3 μm, L/W ratio = 6.2. Appressoria pale brown, smooth-walled, ellipsoidal to clavate, 8–17 × 5–7.5 μm, mean ± SD = 10.7 ± 1.7 × 6.0 ± 0.5 μm, L/W ratio = 1.8.

Culture characteristics — Colonies on PDA flat with entire margin, aerial mycelium sparse, cottony, surface pale grey-black with white margin; reverse black to dark grey-green in centre with white margin. Colony diam 56–57 mm in 5 d. Conidia in mass not observed on PDA or SNA.

Materials examined. CHINA, Hubei Province, Wuhan City, on leaves of P. pyrifolia cv. Jinshui, 1 Aug. 2016, M. Fu (holotype HMAS 247824, culture ex-type CGMCC 3.18903 = PAFQ26); ibid., culture PAFQ26a, PAFQ26b, PAFQ26c, and PAFQ26d.

Notes — Isolates of C. jinshuiense are phylogenetically closely related to Colletotrichum sp. isolate CGMCC 3.15172 (Fig. 5), which was reported as an endophytic Colletotrichum species from Bletilla ochracea (Orchidaceae) in China (Tao et al. 2013), whereas they are different in GAPDH (94.98 %), and TUB2 (98.12 %). Furthermore, the PHI test (Φw = 1) did not detect recombination between these isolates and Colletotrichum sp. isolate CGMCC 3.15172 (Fig. 6a). In this study, C. jinshuiense clustered in the C. dematium species complex, which is often associated with herbaceous plants (Damm et al. 2009). The asexual and sexual morphs of C. jinshuiense were not observed on PDA or SNA, while they easily developed on pear fruit and leaves, indicating that pear tissue plays an important part in the epidemiology and life cycle of C. jinshuiense.

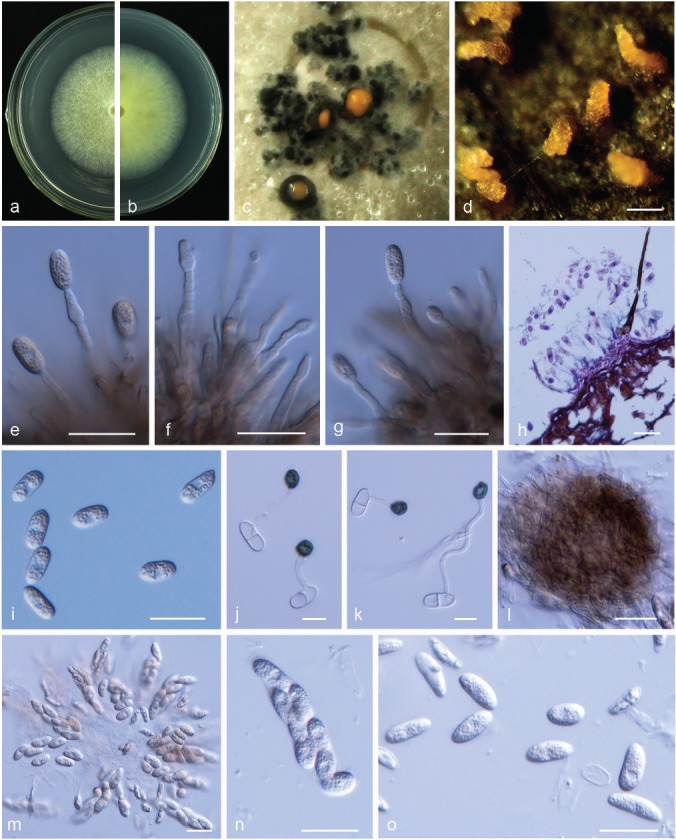

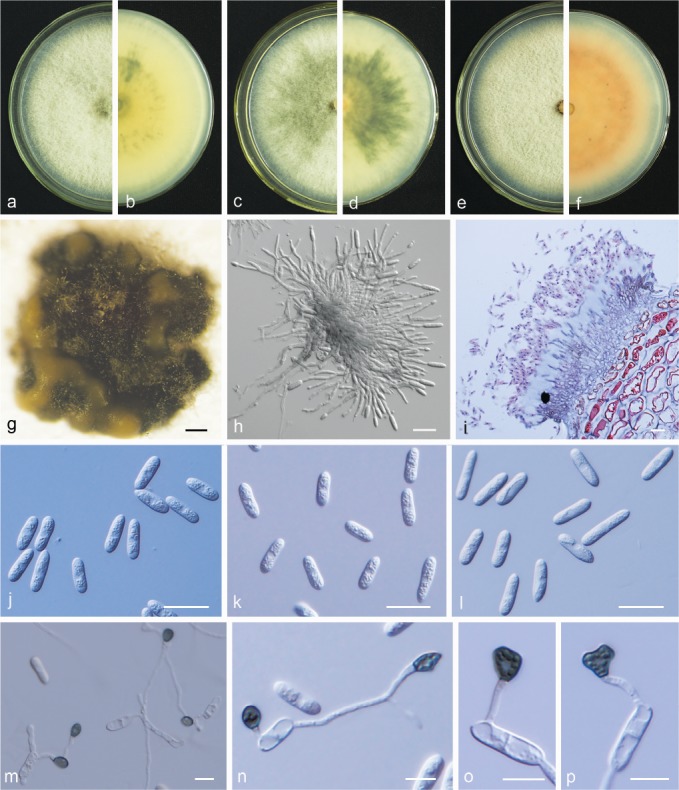

Colletotrichum karstii Yan L. Yang et al., Cryptog. Mycol. 32: 241. 2011. — Fig. 14

Fig. 14.

Colletotrichum karstii. a, b. Front and back view, respectively, of 6-d-old PDA culture; c. conidiomata; d. conidiophores; e, f. section view of acervulus produced on pear leaf (P. pyrifolia cv. Cuiguan) and fruit (P. bretschneideri cv. Huangguan), respectively; g. conidia; h–j. appressoria; k, l. asci; m. ascospores (a–h. isolate PAFQ14, i, k–m. isolate PAFQ40, j isolate PAFQ52; a–d, g, k–m produced on PDA agar medium). — Scale bars: c = 200 μm; d–g, k–m = 20 μm; h–j = 10 μm.

Description & Illustration — Yang et al. (2011).