Abstract

Pregnancy increases basal sympathetic nerve activity (SNA), but the mechanism is unknown. Insulin and leptin are two sympathoexcitatory hormones that increase during pregnancy; yet, pregnancy impairs central insulin- and leptin-induced signaling. Therefore, to test if insulin or leptin contribute to basal sympathoexcitation, or instead pregnancy induces resistance to the sympathoexcitatory effects of insulin and leptin, we studied α-chloralose anesthetized late pregnant rats, which exhibited increases in lumbar SNA (LSNA), splanchnic SNA, and heart rate (HR) compared to nonpregnant animals. In pregnant rats, transport of insulin into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and across the blood-brain barrier in some brain regions increased, but brain insulin degradation was also increased; brain and CSF insulin levels were not different between pregnant and nonpregnant rats. While icv insulin increased LSNA and HR and baroreflex control of LSNA and HR in nonpregnant rats, these effects were abolished in pregnant rats. In parallel, pregnancy completely prevented leptin’s actions to increase lumbar, splanchnic, and renal SNA and baroreflex control of SNA. Blockade of insulin receptors (with S961) in the arcuate nucleus, the site of action of insulin, did not decrease LSNA in pregnant rats, despite blocking the effects of exogenous insulin. Thus, pregnancy is associated with central resistance to insulin and leptin, and these hormones are not responsible for the increased basal SNA of pregnancy. Because increases in LSNA to skeletal muscle stimulates glucose uptake, blunted insulin- and leptin-induced sympathoexcitation reinforces systemic insulin resistance, thereby increasing delivery of glucose to the fetus.

Keywords: pregnancy, insulin resistance, sympathetic nerve activity, leptin, S961, arcuate, BBB insulin transport

INTRODUCTION

Normal pregnancy decreases arterial pressure, due to falls in systemic vascular resistance (Longo, 1983; Robson et al., 1989). To partially counteract primary vasodilation, pregnancy activates several pressor and fluid-retaining systems, including sympathetic nerve activity [SNA; for reviews, see (Fu & Levine, 2009; Reyes et al., 2018)] to the heart (Cohen et al., 1988; Brooks et al., 1997), adrenal (Anglin & Brooks, 2003), kidney (Masilamani & Heesch, 1997), gastrointestinal tract (Shi et al., 2015a), and skeletal muscle (Greenwood et al., 1998; Greenwood et al., 2001; Jarvis et al., 2012; Shi et al., 2015a). Importantly, the stark elevation in SNA observed in normal pregnancy is amplified during preeclampsia (Greenwood et al., 1998; Greenwood et al., 2001), a life-threatening hypertensive complication that occurs in 6–10% of pregnant women (Roberts & Bell, 2013). An understanding of this exaggerated SNA increase requires identification of the mechanisms underlying sympathoexcitation during normal pregnancy; however, very little information is currently available.

Recent evidence indicates that hypothalamic brain sites, such as the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and the arcuate nucleus (ArcN), contribute to the tonic drive for elevated SNA (Shi et al., 2015a). Pregnancy alters the activity of two major ArcN neuronal types that project to the PVN: it decreases the activity of Neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons, which tonically inhibit PVN presympathetic neurons, and simultaneously, it increases the excitation imparted by pro-opiomelanocorticotropin (POMC) neurons (Shi et al., 2015a). However, the mechanisms by which pregnancy alters the activity of these ArcN neuronal subtypes are unknown.

Leptin and insulin are metabolic hormones that act in the ArcN to increase SNA via inhibition of NPY neurons and activation of POMC neurons (Ward et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2015b; Cassaglia et al., 2016). Pregnancy increases leptin levels in plasma (Highman et al., 1998; Trujillo et al., 2011) and produces insulin resistance (Munoz et al., 1995; Daubert et al., 2007; Lain & Catalano, 2007), which can elevate plasma insulin levels (Hornnes, 1985; Munoz et al., 1995; Kirwan et al., 2002). However, during pregnancy, marked central resistance to the anorexic effects of leptin, and impaired leptin and insulin hypothalamic signaling, have been observed (Ladyman et al., 2010; Ladyman & Grattan, 2017). Whether sympathoexcitatory responses to insulin or leptin are similarly attenuated is unknown. Moreover, whether pregnancy increases brain insulin levels in parallel to plasma has not been investigated. Brain insulin is derived by the saturable transport of plasma insulin across the blood-brain barrier (BBB). It has been assumed that the insulin transporter is similar if not identical to the insulin receptor (Banks et al., 2012). Thus, pregnancy-induced systemic insulin resistance could reduce insulin transport across the BBB and brain insulin levels. On the other hand, recent evidence suggests that a protein distinct from the insulin-signaling receptor mediates movement of insulin from blood to brain (Rhea et al., 2018). Therefore, to test the hypothesis that insulin or leptin contribute to pregnancy-induced sympathoexcitation, we determined in late pregnant rats if: 1) pregnancy increases the transport of insulin across the blood-brain barrier or brain insulin levels; 2) insulin and leptin increase SNA normally during pregnancy; and 3) blockade of ArcN insulin receptors (InsR) decreases SNA.

METHODS

Animals and ethical approval

Experiments were performed using female virgin or pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River), for which food (LabDiet 5001, Richmond, IN) and water were provided ad libitum. Vivarium temperature was maintained at 22±1°C. Some rats were bred in house; the presence of vaginal sperm was designated pregnancy day 0. Other timed-pregnant and age-matched (11–12 weeks) virgin rats were obtained from Charles River, and arrived one week prior to experiments. Experiments were performed on pregnancy day 20. Rats were generally housed in pairs, but during pregnancy were housed singly. In some rats, vaginal epithelial cytology was examined daily to identify proestrus; at least two 4–5 day cycles were examined to establish the estrus cycle. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Health and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional (Oregon Health & Science University or Veterans Affairs) Animal Care and Use Committee.

Does pregnancy alter the transport of insulin across the blood-brain barrier (BBB)?

Radioactive Labeling of Insulin and Albumin

Human insulin (Sigma, St Louis) was radioactively labeled with 131I by the chloramine-T method and purified on a G-10 column of Sephedex G-10. Specific activity was about 55Ci/g and the purified radioactive insulin (I-Ins) was used within 24 h of labeling. Human albumin (Sigma) was radioactively labeled with 125I using the chloramine-T method and purified on a column of G-10; the purified radioactive albumin (I-Alb) used within 1 week of labeling.

Blood-to-Brain Transport: Multiple-Time Regression Analysis (MTRA)

Rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital, which preserves insulin sensitivity and plasma insulin levels (Saha et al., 2005; Guarino et al., 2013; Sano et al., 2016). The right jugular vein was exposed, and an IV bolus of 200 μl lactated Ringers containing 2(106) cpm of I-Ins and 2(106) cpm of I-Alb was given into the jugular vein. At various time points after the IV injection (1,2,3,4,5, 7.5, and 10 min; n = 2/time point), blood was obtained from the left carotid artery, the rat was decapitated, and the brain dissected into the olfactory bulb, cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and remainder of the brain. The levels of radioactivity in these brain regions and in 50 μl of the carotid artery serum were determined in a gamma counter and the brain region/serum ratios in units of μl/g was calculated. Ratios for whole brain were calculated by first adding the weights and cpm for all of the brain regions except the olfactory bulb and then dividing the composite level of radioactivity by the composite weight. The brain/serum ratios for I-Ins were corrected for vascular space by subtracting the paired brain/serum ratio for I-Alb, yielding delta I-Ins. The ratios for whole brain or the various brain regions were plotted against exposure time (Expt) in units of minutes using the equation:

where Cp(t) is the concentration of radioactivity in plasma at time t. The brain/serum ratios for I-Ins, I-Alb, and delta I-Ins were plotted against their Expt; points lying significantly outside the linear relationship (1–2 per experiment) were excluded. A statistically significant correlation between brain/serum ratios and Expt indicates transport across the BBB with the slope a measure of the unidirectional influx rate (Ki), measured in units of μl/g-min. Slopes were compared using Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Inc, San Diego, CA).

In other rats, CSF from the posterior fossa and blood from the carotid artery were collected 5 min after the iv bolus of I-Alb + I-Ins (5×106 cpm of each). Results were expressed as the CSF/serum ratio for both I-Alb and I-Ins where a 50 μl volume of both CSF and serum were counted. CSF/serum ratios were compared between pregnant and control rats by Student’s t-test, with p<0.05 taken as statistically significant.

Insulin Degradation by Brain

Hemi-brains from day 20 of timed pregnant females or age matched female controls were added to 2 ml of phosphate buffer solution (0.01 M phosphate, 0.138M NaCl, 0.0027 M KCl, pH 7.4), homogenized, and serially diluted to a concentration of 1:100 of the original stock homogenate. At t = 0, insulin was added to an aliquot of 1:100 homogenate to a concentration of 10 ng/ml and immediately, 15, or 30 min later Protease inhibitor (Sigma) was added. Samples were kept at room temperature until addition of Protease inhibitor and then stored on ice. At completion of study, insulin levels were determined by radioimmunoassay (Millipore kit #SRI-13K, Burlington, Ma). Log values of insulin were regressed against time and the slopes of the lines for pregnant vs control compared using Prism 7.0.

Measurement of brain insulin concentration

Animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and serum and brains were collected. The left hemi brain was frozen on dry ice and stored at −70. The right hemi brain was minced and homogenized in 5% TFA, 80% EtOH, and centrifuged for 10 min at 5000xg at 4C. Three ml of the supernatant were collected and lyophilized. The samples were reconstituted in 0.6 ml of PBS, and insulin was measured using the sensitive rat insulin RIA kit (Millipore #SRI-13K). For serum, 0.1 ml was submitted to RIA. In a separate group of rats, CSF was collected from the posterior fossa and was pooled until 200 μl was achieved. Matching plasma from the same animals was pooled in the same proportions. These CSF and serum samples were then assayed by RIA. Mean values were compared by Student’s t-test.

Does insulin contribute to elevated basal SNA in pregnant rats?

Surgery

Anesthesia was induced and maintained with 2–5% isoflurane in 100% oxygen, while body temperature was maintained at 37 ± 1°C using a rectal thermistor and heating pad. Surgery was then performed to implant a tracheal tube, femoral arterial and venous catheters, and stainless steel electrodes around the lumbar, splanchnic or renal sympathetic nerves. A midline skin incision was made on the top of the head, and the skull was prepared for icv infusions or ArcN nanoinjections, as previously described (Li et al., 2013; Cassaglia et al., 2014). After completion of surgery, isoflurane anaesthesia was slowly withdrawn over 30 min, and a continuous intravenous infusion of α-chloralose was initiated and continued for the duration of the experiment. Virgin rats received a 50 mg•kg−1 loading dose over 30 min followed by a 25 mg•kg−1•h−1 maintenance dose; pregnant rats received a dose equivalent to the weight of a virgin rat at a similar age. Some rats were instead anesthetized with urethane (1.1 g/kg; pregnant rats received the same absolute amount of urethane as their virgin counterparts). Anesthetic depth was regularly confirmed by the lack of a pressor response to a foot or tail pinch; if necessary, additional anesthetic was administered. After completion of surgery and the administration of the α-chloralose or urethane, rats were allowed to stabilize for ≥60 min before experimentation.

Experimental Protocols

After completion of the experiment, rats were killed with an iv injection of a barbiturate (Euthasol; Virbac AH, Inc., Fort Worth, TX). (1). Does pregnancy alter the sympathoexcitatory responses to insulin? Experiments were first performed in urethane-anesthetized late pregnant and nonpregnant rats, because urethane preserves autonomic reflexes. The effects of insulin on baseline or baroreflex control of LSNA does not vary with the estrous cycle (Shi & Brooks, 2015); therefore, the cycle was not established before experimentation. Briefly, as previously described (Pricher et al., 2008; Shi & Brooks, 2015), insulin (100 μU min−1 at 0.6 μl min−1) was infused icv for 2 hours in late pregnant (n=6) and nonpregnant rats (n=4). LSNA and HR were measured just before and 1 and 2 hr after initiating the insulin infusion. Second, urethane causes insulin resistance, at least systemically; therefore, we also examined the effects of icv insulin in virgin (n=8) and late pregnant (n=4) rats anesthetized with α-chloralose. (2). Does ArcN insulin contribute to elevated SNA in pregnant rats? The ArcN is the sole central site at which insulin increases SNA (Cassaglia et al., 2011; Luckett et al., 2013). Therefore, the ArcN was targeted in these experiments. In α-chloralose-anesthetized pregnant and nonpregnant rats, ArcN nanoinjections [(Cassaglia et al., 2011; Cassaglia et al., 2016) 30 nl] were made bilaterally, with ∼2 min between injections, and each injection was conducted over approximately 5–10 s using a pressure injection system (Pressure System IIe, Toohey Company, Fairfield, NJ). In some animals, prior to nanoinjection of drugs, aCSF was injected into the ArcN as a vehicle control. Experiments were first conducted to identify a dose of the insulin receptor antagonist, S961 (Schaffer et al., 2008; Paranjape et al., 2011) (100 ng in 30nL; Novo Nordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark), that blocks the effects of exogenous insulin [60 pU in 30 nL, bilaterally (Cassaglia et al., 2016)]. S961 (n=3) or aCSF (n=6) was administered 10 min before insulin. Next, in another group of late pregnant (n=4) and virgin rats (n=6), aCSF and/or aCSF containing S961 was injected bilaterally into the ArcN, and measurements of MAP, HR and LSNA were continued for 60 min after each injection. Fluorescent polystyrene microbeads (FluoSpheres, F8803, 1:200; Molecular Probes) were included in the injectate to verify the injection sites using a standard anatomical atlas (Paxinos & Watson, 2007), as shown in Figure 5C. (3). Does pregnancy alter the sympathoexcitatory responses to leptin? Leptin also acts in the ArcN (and other hypothalamic sites) to increase SNA (Harlan & Rahmouni, 2013). Therefore, to begin to investigate the mechanisms by which pregnancy alters insulin-induced sympathoexcitation, we next determined if pregnancy modifies the SNA responses to leptin. In nonpregnant rats, the ability of leptin to increase LSNA and RSNA is only apparent during proestrus; leptin’s effects on SSNA and HR are similar throughout the estrus cycle (Shi & Brooks, 2015). Moreover, baseline control of RSNA varies with the estrous cycle (Goldman et al., 2009; Shi & Brooks, 2015). Therefore, we determined the effect of icv leptin [3 μg in 3 μL, followed by 5 μg/h (Li et al., 2013)] on LSNA, RSNA, and SSNA in α-chloralose-anesthetized pregnant rats and compared these responses to those of proestrus rats. We collected blood samples for measurements of serum estradiol, as previously described (Shi & Brooks, 2015). The results of the proestrus rats have been previously reported (Shi & Brooks, 2015). Importantly, the studies of late pregnant rats were conducted during the same time period.

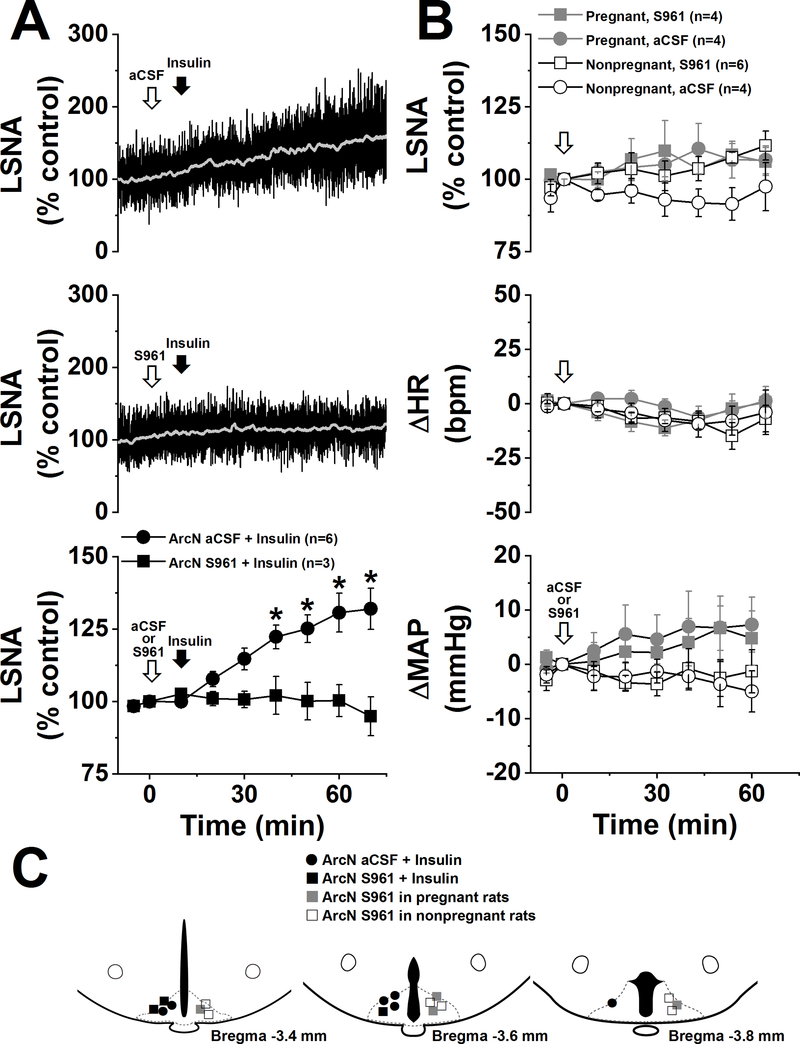

Figure 5. Blockade of ArcN InsR does not lower LSNA in pregnant or nonpregnant rats.

A. ArcN nanoinjections of insulin increase LSNA in nonpregnant rats, and this response was completely blocked by prior injection of the insulin antagonist, S961. B. Nanoinjections of aCSF or S961 do not significantly alter LSNA, HR, or MAP in pregnant (P) and nonpregnant (NP) rats. Basal values of MAP (in mmHg) were: 110±5 (NP+S961), 103±8 (NP+aCSF), 80±8 (P+S961), and 71±7 (P+aCSF). Basal values of HR (in bpm) were: 329±10 (NP+S961), 325±17 (NP+aCSF), 460±16 (P+S961), and 453±18 (P+aCSF). C. Histological maps illustrating ArcN injection sites for the experiments shown in A. and B. Note that all pregnant rats that received S961 (n=4) first received aCSF and that 4 of 6 nonpregnant rats that received S961 first received aCSF.

Data acquisition

Pulsatile and mean arterial pressure (MAP), HR and SNA were continuously recorded using a Biopac MP100 data acquisition and analysis system and a Grass tachograph amplifier. Data were sampled at 2000 Hz, and SNA was band-pass filtered (100–3000 Hz), amplified (×10,000), rectified and integrated in 1 sec bins. Mean values of MAP and HR were also calculated from the 1 sec binned data. In each rat, post-mortem SNA was determined at the end of the experiment, and this background level was subtracted from values of SNA recorded during the experiment. SNA was normalized to control SNA, which was the 30 sec average just before the first baseline baroreflex curve was produced or before experimental infusions or injections were initiated (% of control).

Measurements of baroreflex function

Pregnancy impairs gain of baroreflex control of heart rate, and icv infusion of insulin normalizes HR baroreflex gain in conscious rats (Azar & Brooks, 2011), suggesting that low brain insulin levels or actions contribute. However, whether insulin (or leptin) similarly improves baroreflex control of SNA in pregnant animals has not been determined. Therefore, complete sigmoidal baroreflex curves were also generated, before, and 1 and 2 hr after, initiating an icv insulin or leptin infusion, using the following protocol. MAP was first quickly lowered from baseline to ∼50 mmHg by iv infusion of nitroprusside (1 mg ml−1; 20μl min−1), and then steadily and smoothly raised to ∼175 mmHg over 3–5 min, by both withdrawing nitroprusside and infusing phenylephrine at increasing rates (1 mg ml−1; 1–35 μl min−1). Baroreflex curves were constructed from data obtained during the MAP upswing from 50 to 175 mmHg. The sigmoidal baroreflex relationships relating SNA to MAP were fitted and compared using the Boltzman equation: LSNA or HR = (P1 – P2)/[1 + expP4(MAP – P3)]. P1 is the maximum LSNA or HR, P2 is the minimum LSNA or HR, P3 is the MAP associated with the LSNA/HR value midway between the maximal and minimal values (BP50; denotes position of the curve on the x-axis), and P4 is the coefficient used to calculate maximum gain, – (P1 – P2)×P4×¼, which is an index of the slope of the linear part of the sigmoidal baroreflex curve. Absolute values of gain, the maximum and minimum LSNA or HR, and the BP50 are illustrated in Figures 3, 4, and 6.

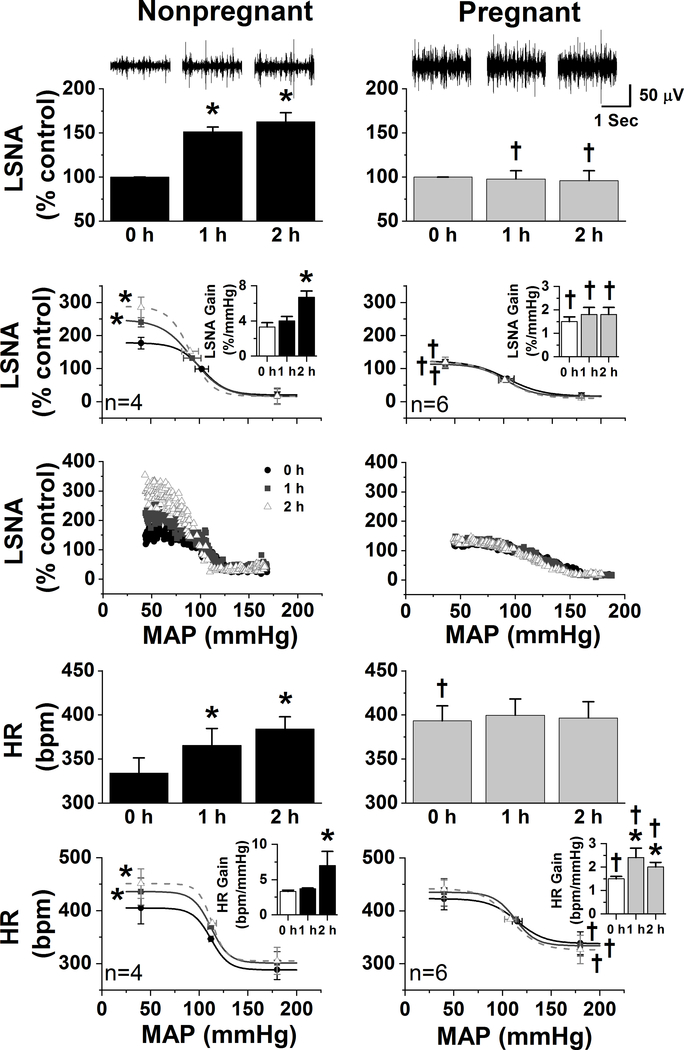

Figure 3. The sympathoexcitatory responses to insulin are abolished in urethane-anesthetized pregnant rats.

In nonpregnant rats (left column), icv insulin increased LSNA, baroreflex control of LSNA by increasing the baroreflex maximum and gain, HR, and baroreflex control of HR by increasing the maximum and gain. In contrast, insulin only increased the gain of baroreflex control of HR in pregnant rats. *: P<0.05 within group; †: P<0.05 pregnant compared to nonpregnant rats.

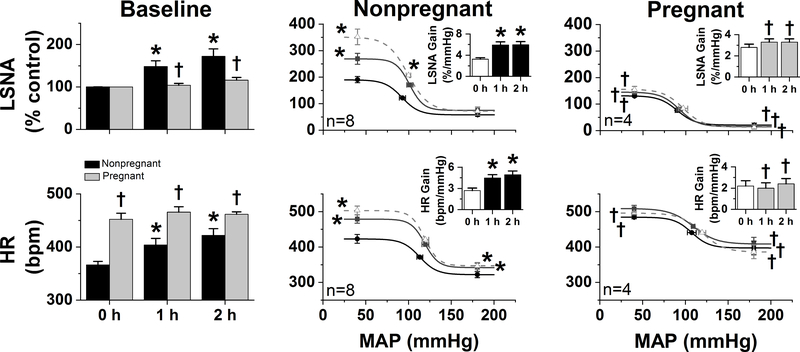

Figure 4. The sympathoexcitatory responses to insulin are abolished in α-chloralose-anesthetized pregnant rats.

In nonpregnant rats, icv insulin increased baseline and baroreflex control of LSNA and HR. In contrast, icv insulin had no effects in pregnant rats. *: P<0.05 within group; †: P<0.05 pregnant compared to nonpregnant rats.

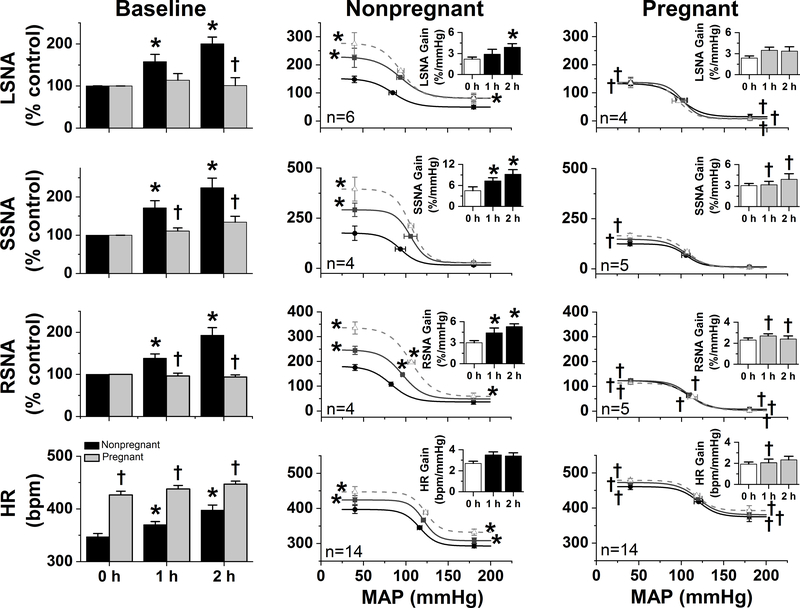

Figure 6. The sympathoexcitatory responses to leptin are abolished in α-chloralose-anesthetized pregnant rats.

In nonpregnant rats, icv leptin increased baseline and baroreflex control of LSNA, SSNA, RSNA, and HR. These effects were not evident in pregnant rats. *: P<0.05 within group; †: P<0.05 pregnant compared to nonpregnant rats.

Serum estrogen levels

In some rats, arterial blood was collected for analysis of serum estrogen (E2) levels by radioimmunoassay (Goodman, 1978; Anglin & Brooks, 2003). After collection, serum was stored at –80°C until assayed by the OHSU Endocrine Technology and Support Core, as previously described (Shi & Brooks, 2015).

Statistics

Differences in baseline values between pregnant and nonpregnant rats were assessed using a t-test. The effects of blockade of ArcN InsR in pregnant and nonpregnant rats was assessed with 3-way ANOVA for repeated measures [factors are condition (pregnant or nonpregnant), treatment (ArcN aCSF or S961), and time]. Between group differences in the changes in baseline levels of MAP, HR, and SNA, as well as baroreflex function, in response to icv insulin or leptin infusions were determined using 2-way repeated measures ANOVA. Specific between and within group differences were determined using the post-hoc Newman-Keuls test.

RESULTS

Baseline values

Pregnancy markedly altered baseline sympathetic and hemodynamic values (Table 1). MAP was reduced and HR, LSNA, and SSNA were increased. However, a significant increase in basal RSNA was not observed.

Table 1.

Effect of pregnancy on baseline MAP, HR, and SNA.

| MAP (mmHg) | HR (bpm) | LSNA (μV) | SSNA (μV) | RSNA (μV) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonpregnant | 105 ± 2 (n = 41) |

345 ± 4 (n = 41) |

1.1 ± 0.1 (n = 33) |

0.8 ± 0.2 (n = 4) |

4.0 ± 0.8 (n = 4) |

| Pregnant | 85 ± 2* (n = 32) |

429 ± 6* (n = 32) |

3.1 ± 0.4* (n = 21) |

4.0 ± 0.6* (n = 5) |

6.4 ± 1.2 (n = 5) |

P<0.05, pregnant compared to nonpregnant.

Pregnancy increases brain transport of insulin, but also increases brain insulin degradation

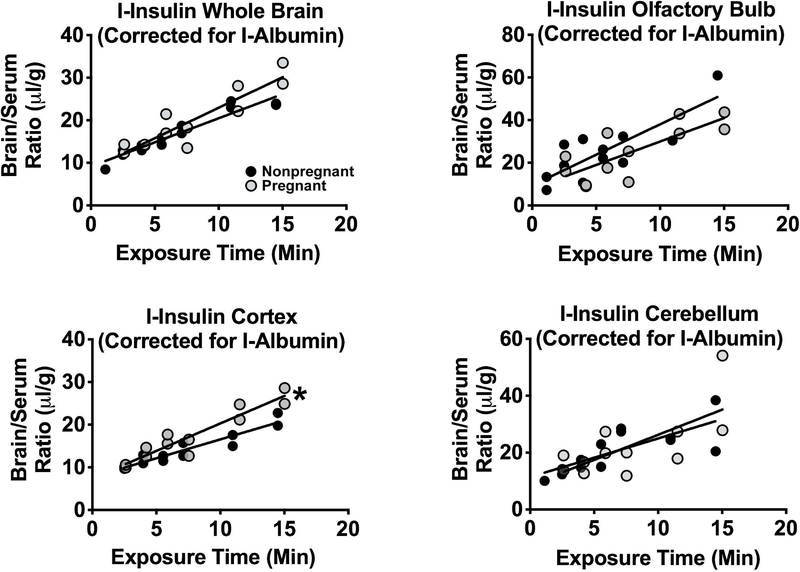

Figure 1 shows the effects of pregnancy on insulin uptake by whole brain, cerebellum, cerebral cortex, and olfactory bulb. These results are for delta insulin; that is, the brain/serum ratio corrected for the vascular space as measured by albumin. For all groups and regions, there was a statistically significant relation between delta brain/serum ratios and Expt, indicating that insulin was being transported into all of these regions. Comparison of the rates of entry between pregnant and nonpregnant females showed no difference for olfactory bulb or cerebellum, a significant increase in the cerebral cortex (Control Ki = 0.88±0.10 μl/g-min; Pregnant Ki = 1.29±0.14 μl/g-min; p<0.05), and insignificant increments in whole brain (Control Ki = 1.13±0.10 μl/g-min; Pregnant Ki 1.43±0.20 μl/g-min; P=0.096).

Figure 1. Insulin transport into brain.

The rate of transport across the blood-brain barrier of radioactive insulin after correction for vascular space using radioactive albumin was determined by the multiple-time regression analysis method. The transport rate into cortex (lower left panel; n=12, pregnant; n=13, nonpregnant) was significantly increased (*: P<0.05). However, significant differences for whole brain (upper left panel; P=0.096; n=12, pregnant; n=13, nonpregnant) olfactory bulb (upper right panel; n=12; pregnant; n=12, nonpregnant) and for cerebellum (lower right panel; n=12, pregnant; n=13, nonpregnant) were not observed.

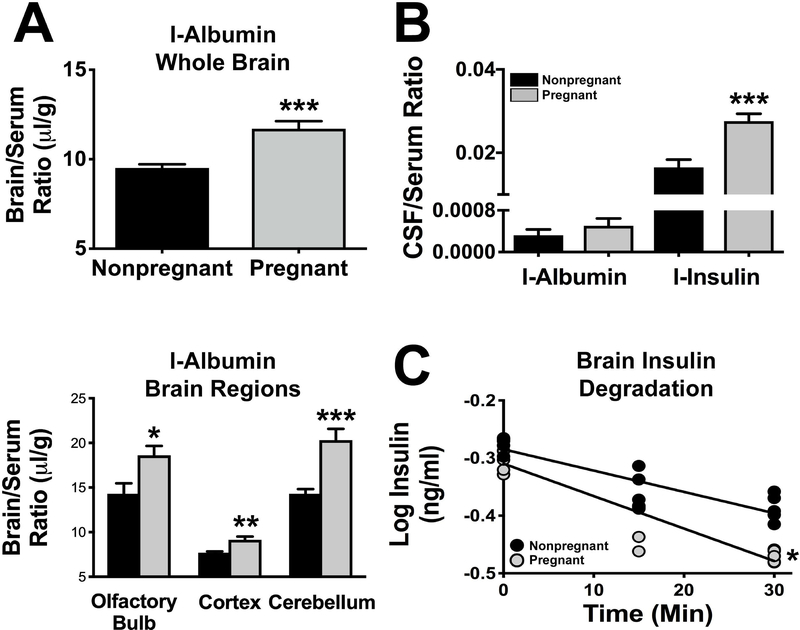

There was no correlation between the brain/serum ratio values for I-Alb and Expt, indicating that there was no measurable penetration of albumin into brain at this time. The albumin space, therefore, is a measure of the vascular space of the brain. When the data were collapsed across time, a statistically significant increase in brain vascular space with pregnancy was found for whole brain (P<0.001), cerebellum (P<0.001), cerebral cortex (P<0.01), and olfactory bulb (P<0.05); Figure 2A.

Figure 2. Vascular space, insulin transport into the CSF, and brain degradation of insulin in pregnant and nonpregnant rats.

A. The vascular space, as measured with radioactive albumin, was increased in pregnant compared to nonpregnant rats in whole brain (upper panel; n=14, pregnant; n=14, nonpregnant) and in specific brain regions (lower panel; n=14, pregnant; n=14 nonpregnant). B. The CSF/serum ratio for radioactive insulin (n=10, pregnant; n=8, nonpregnant), but not for radioactive albumin (n=8, pregnant; n=8, nonpregnant), was increased in pregnancy. The uptake of radioactive insulin was about 50 times greater than that of radioactive albumin consistent with its saturable transport across the BBB. C. Brain degradation of insulin increased during pregnancy. Grey circles indicate pregnant animals (n=14) and black circles indicate nonpregnant (n=14) animals. *: P<0.05; ***: P<0.001.

The CSF/serum ratio for I-Ins was about 60% higher in pregnant than nonpregnant females (P<0.001); Figure 2B. The CSF/serum I-Alb ratio was not statistically different between pregnant and nonpregnant females. The ratio for I-Ins was about 50 times greater than the ratio for I-Alb.

Serum, CSF, and brain insulin levels (as measured by RIA in ng/ml) did not differ between pregnant (serum, 3.1±0.5, n=15; CSF, 0.046±0.004, n=17; brain, 0.16±0.02, n=16) and nonpregnant (serum, 3.2±0.3,n=15; CSF, 0.045±0.005, n=14; brain, 0.16±0.05, n=10) rats.

Degradation of insulin by brain homogenates was faster in pregnant than nonpregnant female rats. Figure 2C shows the regression line for log insulin concentration vs time for pregnant (m = −0.00563±0.00059, n=15, r=0.935, p<0.0001) and control (m=−0.0037±0.00056, n = 15, r = 0.877, p<0.0001) rats. These lines were different (P<0.05) with a calculated half-life in nonpregnant rats of 81 min and in pregnant rats of 53 min.

Collectively, these data reveal that pregnancy does not significantly alter brain insulin concentrations.

Pregnancy abolishes the sympathoexcitatory responses to insulin

In urethane-anesthetized rats before insulin infusion (Figure 3), pregnancy reduced the gain of baroreflex control of HR and LSNA (gain is the change in HR/LSNA for a given change in MAP). In addition, during pregnancy, the HR minimum was elevated (i.e. HR at high MAP was increased compared to nonpregnant rats) and the LSNA maximum was decreased (i.e. LSNA achieved at low MAP was suppressed). As a result, the reflex-induced ranges of HR (84±6 bpm, pregnant; 117±8 bpm, nonpregnant) and LSNA (107±16 % control, pregnant; 158±18 % control, nonpregnant) were both reduced (P<0.05). In nonpregnant rats, insulin increased LSNA, HR, and baroreflex control of LSNA and HR, by increasing the maximal LSNA and HR achieved at low MAP, as well as baroreflex gain. In sharp contrast, in pregnant rats, icv insulin infusion did not increase LSNA or baroreflex control of LSNA. However, insulin did increase gain of baroreflex control of HR, as we observed previously in conscious pregnant rats (Azar & Brooks, 2011), without altering any other baroreflex parameters.

In chloralose-anesthetized rats (Figure 4), pregnancy again modified the HR and LSNA baseline baroreflex curves, but in different ways. Decreases in baroreflex gain or range were not observed. Instead, pregnancy increased both the HR maximum and minimum, and suppressed the LSNA maximum and minimum. Most importantly, while in nonpregnant rats icv insulin again increased HR, LSNA, and baroreflex control of HR and LSNA (by increasing baroreflex gain and the baroreflex maximum), none of these effects were observed in pregnant rats. Collectively, these data indicate that pregnancy almost completely blocks the effects of central insulin to increase HR, LSNA, and baroreflex control of HR and LSNA.

During pregnancy, endogenous insulin does not support elevated basal SNA via an action in the ArcN

As shown in Figure 5, 100 ng of the insulin receptor antagonist, S961 (Schaffer et al., 2008; Paranjape et al., 2010) was sufficient to block the effects of a modest dose of insulin into the ArcN (Figure 5A). Therefore, we next administered S961 into the ArcN of late pregnant and virgin rats. As shown in Figure 5B, neither S961 nor aCSF significantly altered LSNA, MAP or HR in either pregnant or nonpregnant rats. These data do not support the hypothesis that endogenous insulin contributes to basal SNA via an action in the ArcN in either pregnant or nonpregnant rats.

Pregnancy abolishes the sympathoexcitatory responses to leptin

As expected, late pregnancy increased serum estrogen levels compared to rats in diestrus [66±7 pg/ml (pregnant, n=5); 34±3 pg/ml (diestrus, n=8); P<0.05], although remained lower than proestrus rats [96±11 pg/ml (n=8); P<0.05]. Importantly, however, the estrogen levels achieved in rats on gestational day 20 were not different from the levels produced in ovariectomized rats treated with estrogen, in which leptin was capable of producing significant sympathoexcitation (Shi & Brooks, 2015).

As in the insulin-treated cohort, in leptin-treated rats (Figure 6) at baseline, pregnancy increased the HR baroreflex maximum and minimum and decreased the LSNA baroreflex maximum and minimum. In parallel, the maximums of baroreflex control of SSNA and RSNA were also suppressed, as was the minimum of baroreflex control of RSNA. Baroreflex gain did not differ significantly between nonpregnant and pregnant rats. In nonpregnant rats, leptin increased HR, LSNA, SSNA, and RSNA. Leptin also enhanced baroreflex function, by enhancing gain of baroreflex control of LSNA, SSNA, and RSNA. The maximal levels of HR, LSNA, SSNA, and RSNA at low MAP were also elevated. Finally, leptin increased the minimums of baroreflex control of HR, LSNA, and RSNA. In sharp contrast, leptin had no effects in pregnant rats (Figure 6).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to test if insulin or leptin contributes to the increased basal SNA characteristic of pregnancy. Our major new findings are that, in late pregnant rats: 1) Transport of insulin across the BBB in some brain regions, and into CSF, were increased, but brain insulin degradation was also increased; brain and CSF insulin levels were not different; 2) The brain vascular space was increased; 3) The sympathoexcitatory responses to insulin and leptin were abolished; and 4) Blockade of ArcN InsR did not lower SNA. Collectively, these data suggest that pregnancy renders the brain resistant to the sympathoexcitatory effects of insulin and leptin and that these hormones do not mediate pregnancy-induced sympathoexcitation.

Pregnancy increases plasma leptin levels (Highman et al., 1998; Trujillo et al., 2011), in part secondary to increased adipose deposition. Pregnancy also induces systemic insulin resistance (Hornnes, 1985; Munoz et al., 1995; Brooks et al., 2010b), which increases plasma insulin concentrations in pregnant women (Hornnes, 1985; Kirwan et al., 2002). However, in experimental animals, the changes in plasma insulin have been variable. In fed rats or animals after glucose administration, plasma insulin is elevated during pregnancy (relative to nonpregnant animals) (Munoz et al., 1995). In contrast, in pentobarbital anesthetized (Leturque et al., 1980; Leturque et al., 1984) and fasted conscious animals (Nolan & Proietto, 1994; Daubert et al., 2007; Storlien et al., 2016), increments in plasma insulin are usually not significant, similarly to the present results. Collectively, this information suggests that, in pregnant animals, insulin resistance causes frank increases in plasma insulin only after eating or a glucose challenge, which could abrogate a role for insulin in pregnancy-induced sympathoexcitation, at least in animals.

We therefore next investigated whether pregnancy increases brain insulin levels, which is a function of insulin entry into brain across the BBB versus parenchymal insulin degradation. We used MTRA, a well-established method to calculate the rate of transport of substances across the BBB, and corrected for the albumin space of the brain, to greatly increase the statistical robustness of the measures. We found a significant increase of about 47% in the transport rate of insulin into the cortex; however, insulin transport into whole brain, olfactory bulb, or the cerebellum was not significantly altered, although insulin transport was measurable into these areas. Interestingly, these changes in insulin transport differ from leptin transport, which is reduced during pregnancy, in part due to increased binding of plasma leptin (Seeber et al., 2002), but also to decreased trans-endothelial leptin transport (Trujillo et al., 2011). Pregnancy markedly increases plasma triglycerides (Scow et al., 1964), which both inhibit leptin BBB transport and increase insulin BBB transport (Banks et al., 2004; Urayama & Banks, 2008). Therefore, plasma triglycerides are a plausible candidate mechanism for the divergent impact of pregnancy on leptin versus insulin transport across the BBB.

We also measured insulin entry into CSF, which was increased by about 60% in pregnant rats, although CSF insulin levels did not differ between pregnant and nonpregnant rats. Previously, we reported that pregnancy decreases CSF insulin levels in pregnant conscious rabbits and anesthetized rats (Daubert et al., 2007; Azar & Brooks, 2011). The explanation for these different observations is not clear, although the disparity suggests that factors that increase CSF insulin levels (i.e. insulin transport) and loss both may be elevated in pregnant individuals. Indeed, the brain degraded insulin significantly faster during pregnancy. Thus, regional increases in the rate of transport of insulin may be counter-balanced by increased degradation rates. In support, we found that pregnancy did not alter brain insulin levels, in parallel to the unchanged CSF insulin levels.

Pregnancy induces central leptin and insulin resistance, as indicated by impaired leptin and insulin signaling and the reduced anorexic effects of leptin (Ladyman et al., 2010; Ladyman & Grattan, 2017). Like pregnancy, obesity in males is associated with both systemic and central insulin and leptin resistance, marked increases in plasma leptin levels, and elevations in basal SNA. Yet, despite global brain leptin and insulin resistance, these hormones produce normal or exaggerated increases in SNA in obese males (Prior et al., 2010; Shi et al., 2019), so called “selective insulin or leptin resistance” (Mark, 2013). Moreover, infusion of insulin or leptin antagonists icv decrease SNA, indicating that these metabolic proteins contribute to the elevated SNA in obese males (Lim et al., 2013). However, whether pregnancy similarly selectively impairs the anorexic, but not the sympathoexcitatory, effects of insulin or leptin had not been investigated. A key observation in the present study was that icv insulin failed to increase SNA in late pregnant rats, studied using two anesthetics. One interpretation of this result is that brain insulin levels or actions are maximal during pregnancy, such that further increases are ineffective. However, counter to this possibility, we found that brain insulin levels were not elevated and that blockade of ArcN insulin receptors did not lower SNA in pregnant rats, unlike its effect in obese males [unpublished observations and (Lim et al., 2013)]. Thus, pregnancy renders the brain resistant to the sympathoexcittory effects of insulin. Collectively, the normal levels of brain insulin, the abolished SNA responses to insulin, and the failure of ArcN S961 to lower SNA, indicate that insulin does not contribute to increased SNA during pregnancy.

We therefore next investigated leptin responses. We have previously shown that the sympathoexcitatory effects of leptin require elevated estrogen levels (Shi & Brooks, 2015), and, as confirmed here, pregnancy increases plasma estrogen levels. Nevertheless, leptin, like insulin, failed to increase SNA to several organs. The effect of pregnancy to block insulin- and leptin-induced increases in LSNA is teleologically significant. Normally, after a meal, insulin- (and leptin-) induced increases in sympathetic nerve activity to skeletal muscle enhance glucose uptake (Nonogaki, 2000), in parallel to the direct actions of these metabolic hormones. During pregnancy, peripheral insulin resistance coupled with blunted insulin- and leptin-induced sympathoexcitation, ensures adequate delivery of this nutrient to the fetus.

We did not investigate the mechanisms by which pregnancy eliminates the sympathoexcitatory responses to insulin and leptin, but the literature offers several possibilities. Insulin increases SNA by acting in one brain site, the ArcN, via a neuropathway that includes stimulation of PVN presympathetic neurons by ArcN-derived α-MSH, and glutamatergic activation of presympathetic neurons in the RVLM (Stocker & Bardgett, 2007; Bardgett et al., 2010; Cassaglia et al., 2011; Ward et al., 2011; Luckett et al., 2013). Pregnancy likely impairs the anorectic effects of insulin in part via disruption of PVN α-MSH-induced signaling (Ladyman et al., 2009). However, ArcN POMC neurons, via release of α-MSH in the PVN, contribute to elevated SNA during pregnancy (Shi et al., 2015a). Therefore, central resistance to the sympathoexcitatory effects of insulin do not appear to involve reduced activation of MC3/4R in PVN presympathetic neurons. Alternatively, pregnancy may disrupt insulin signaling in presympathetic neurons in the ArcN (Ladyman & Grattan, 2017); however, if so, the mechanisms are unclear. In females, another insulin resistant state, obesity, also completely blocks the sympathoexcitatory effects of insulin (Shi et al., 2019). Yet, while pregnancy reduces tonic NPY inhibition, and increases α-MSH stimulation, of presympathetic neurons in the PVN (Shi et al., 2015a), obesity in females has the opposite effect: NPY inhibition is maintained and not inhibitable by insulin, and activation of ArcN POMC neurons by insulin may be reduced (Shi et al., 2019). Thus, like the anorexic effects of leptin (Ladyman et al., 2010), the cellular mechanisms underlying central insulin resistance in pregnancy versus obesity appear to be distinct.

Leptin also binds to receptors in the ArcN to increase SNA. Therefore, like insulin, it is unlikely that the inability of leptin to increase SNA during pregnancy is related to reduced sensitivity of PVN pre-sympathetic neurons to α-MSH (Ladyman et al., 2009), but could involve attenuated leptin signaling in the ArcN (Ladyman & Grattan, 2004). However, unlike insulin, leptin acts in several other sites and neuronal pathways to increase SNA (Harlan & Rahmouni, 2013), some of which retain leptin sensitivity (Ladyman & Grattan, 2004). Therefore, transmission of excitation downstream also may be muted; indeed, pregnancy increases GABAergic inhibition of the RVLM (Brooks et al., 2010a). If so, then how can forebrain mechanisms underlie the marked increased basal sympathoexcitation? First, while RVLM (e.g. baroreflex) control of SNA is attenuated, it is not abolished, suggesting that upstream sympathoexcitation could still be relayed via the RVLM. Alternately, factors that drive increased basal SNA via forebrain sites could also proceed through direct projections to the spinal cord.

A major conclusion of the present study is that normal pregnant animals become resistant to the sympathoexcitatory effects of leptin and insulin. However, this finding does not preclude a role for these metabolic hormones in pregnancy-induced hypertensive states, like preeclampsia. At least two scenarios are possible [for reviews, see (Spradley et al., 2015; Cornelius et al., 2018; Lopez-Jaramillo et al., 2018)]. First, obese pregnant individuals exhibit even greater insulin resistance and increments in the plasma levels of insulin and leptin concentrations; both hormones can impair placentation, a known precursor to preeclampsia. Second, preeclampsia is an inflammatory state, which elevates cytokines like TNF-α and induces the formation of angiotensin II autoantibodies. These factors could counteract the resistance to, and even sensitize, the responses of hypothalamic pre-sympathetic neurons to the sympathoexcitatory effects of insulin and leptin, similarly to the sequelae that leads to exaggerated leptin- and insulin-induced sympathoexcitation in obese males (Johnson & Xue, 2018; Shi et al., 2019). However, future investigation is required to test if either leptin or insulin contribute to pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders.

Pregnancy markedly suppresses baroreflex control of HR (Brooks et al., 2010a). Deficits in baroreflex control of SNA have also been observed [Figure 4; (Brooks et al., 2010a)]. Indirect evidence led us to previously hypothesize that, during pregnancy, impaired baroreflex function and insulin resistance are mechanistically related (Daubert et al., 2007; Azar & Brooks, 2011): 1) Multiple insulin resistance states, including obesity, aging, and Alzheimer’s Disease also exhibit impaired baroreflex function; 2) Pregnancy decreases HR baroreflex gain primarily by attenuating central sympathetic control of the heart (Brooks et al., 1997; Lumbers & Yu, 1999), and insulin increases HR baroreflex gain (Pricher et al., 2008) by enhancing cardiac sympathetic nerve activity (Siani et al., 1990); and 3) In pregnant rats, changes in insulin sensitivity and cardiac baroreflex gain correlate temporally during gestation (Brooks et al., 2012). We proposed several mechanisms by which insulin sensitivity and baroreflex function could be related (Azar & Brooks, 2011): 1) Like in other insulin resistant states, pregnancy reduces transport of insulin across the BBB (or increases brain insulin degradation), to decrease brain insulin levels; 2) Pregnancy decreases responsiveness of the brain insulin receptor and insulin-induced signaling; and 3) A factor that promotes systemic insulin resistance also impairs the baroreflex. In support of the first hypothesis, icv insulin infusion in conscious pregnant rats (and in the present study, urethane-anesthetized rats) improved HR baroreflex gain, without normalizing other deficits in baroreflex function (Azar & Brooks, 2011). In opposition to this hypothesis, however, the present results show that icv insulin did not improve baroreflex control of SNA. In addition, while brain insulin degradation was increased, brain insulin levels were not significantly altered during pregnancy. Instead, the data suggest that desensitization of forebrain insulin receptors (or downstream pathways) may be a link between insulin resistance and decreases in the function of the baroreceptor reflex during pregnancy.

Our studies provide additional information about the impact of pregnancy on the brain vasculature. The brain/serum ratio for albumin was higher in pregnancy in all the brain regions measured (whole brain, cortex, cerebellum, olfactory bulb). The brain/serum ratios for albumin did not increase over time, suggesting that the increased albumin levels were due to an increased vascular space of the brain, rather than leakage across the BBB. This perspective is consistent with the work of Cipolla and colleagues (Johnson & Cipolla, 2015), which documents that BBB permeability and cerebral blood flow are unaltered in pregnant rats. On the other hand, the vascular space for the whole body is markedly increased by pregnancy, and these results indicate that this expansion includes the brain.

The CSF/serum ratios for radioactive albumin were about 2% of those found for insulin and did not differ between pregnant and controls rats. This low CSF/serum ratio for albumin indicates that the posterior fossa taps were not contaminated with blood and so the values for insulin reliable. The lack of difference for CSF/serum I-Alb between pregnant and nonpregnant animals again suggest that those events that can produce increases in CSF levels of albumin, such as disruption of the BBB or altered CSF production and uptake, are not occurring in normal pregnancy.

In summary, our data indicate that during pregnancy insulin and leptin do not contribute to basal sympathoexcitation. More specifically: 1) brain insulin levels are unaltered; 2) neither insulin nor leptin are capable of eliciting increased SNA in late pregnant rats; and 3) blockade of ArcN InsR does not lower SNA. The development of central resistance to the sympathoexcitatory effects of insulin and leptin aids in the maintenance of sufficiently high glucose in plasma for adequate transport into the fetus. Future work is required to identify the (likely) hormonal factors that underlie this teleologically relevant change, in part because counteraction of the mechanism(s) producing central insulin and leptin resistance may drive the even higher levels of SNA that occur with pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders.

KEY POINTS SUMMARY.

Pregnancy increases sympathetic nerve activity (SNA), but the mechanisms are unknown. We tested if insulin or leptin, two sympathoexcitatory hormones increased during pregnancy, contribute.

Transport of insulin across the blood-brain barrier in some brain regions, and into the CSF, was increased, but brain insulin degradation was also increased. As a result, brain and CSF insulin levels were not different between pregnant and nonpregnant rats.

The sympathoexcitatory responses to insulin and leptin were abolished in pregnant rats.

Blockade of arcuate nucleus insulin receptors did not lower SNA in pregnant or nonpregnant rats.

Collectively, these data suggest that pregnancy renders the brain resistant to the sympathoexcitatory effects of insulin and leptin and that these hormones do not mediate pregnancy-induced sympathoexcitation. Increased muscle SNA stimulates glucose uptake. Therefore, during pregnancy, peripheral insulin resistance coupled with blunted insulin- and leptin-induced sympathoexcitation ensures adequate delivery of glucose to the fetus.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance provided by Jennifer Wong.

Sources of funding. This work was supported in part by funding from the NIH (HL088552 and HL128181) and the AHA (15POST23040042).

Footnotes

Competing or conflicts of interests. None.

REFERENCES

- Anglin JC & Brooks VL. (2003). Tyrosine hydroxylase and norepinephrine transporter in sympathetic ganglia of female rats vary with reproductive state. AutonNeurosci 105, 8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azar AS & Brooks VL. (2011). Impaired baroreflex gain during pregnancy in conscious rats: role of brain insulin. Hypertension 57, 283–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Coon AB, Robinson SM, Moinuddin A, Shultz JM, Nakaoke R & Morley JE. (2004). Triglycerides induce leptin resistance at the blood-brain barrier. Diabetes 53, 1253–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Owen JB & Erickson MA. (2012). Insulin in the brain: there and back again. Pharmacol Ther 136, 82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardgett ME, McCarthy JJ & Stocker SD. (2010). Glutamatergic receptor activation in the rostral ventrolateral medulla mediates the sympathoexcitatory response to hyperinsulinemia. Hypertension 55, 284–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks VL, Cassaglia PA, Zhao D & Goldman RK. (2012). Baroreflex function in females: changes with the reproductive cycle and pregnancy. GendMed 9, 61–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks VL, Dampney RA & Heesch CM. (2010a). Pregnancy and the endocrine regulation of the baroreceptor reflex. AmJPhysiol RegulIntegrComp Physiol 299, R439–R451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks VL, Kane CM & Van Winkle DM. (1997). Altered heart rate baroreflex during pregnancy: role of sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. AmJPhysiol 273, R960–R966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks VL, Mulvaney JM, Azar AS, Zhao D & Goldman RK. (2010b). Pregnancy impairs baroreflex control of heart rate in rats: role of insulin sensitivity. AmJPhysiol RegulIntegrComp Physiol 298, R419–R426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassaglia PA, Hermes SM, Aicher SA & Brooks VL. (2011). Insulin acts in the arcuate nucleus to increase lumbar sympathetic nerve activity and baroreflex function in rats. JPhysiol 589, 1643–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassaglia PA, Shi Z & Brooks VL. (2016). Insulin increases sympathetic nerve activity in part by suppression of tonic inhibitory neuropeptide Y inputs into the paraventricular nucleus in female rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 311, R97–R103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassaglia PA, Shi Z, Li B, Reis WL, Clute-Reinig NM, Stern JE & Brooks VL. (2014). Neuropeptide Y acts in the paraventricular nucleus to suppress sympathetic nerve activity and its baroreflex regulation. JPhysiol 592, 1655–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen WR, Galen LH, Vega-Rich M & YounG JB. (1988). Cardiac sympathetic activity during rat pregnancy. Metabolism 37, 771–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius DC, Cottrell J, Amaral LM & LaMarca B. (2018). Inflammatory mediators: a causal link to hypertension during preeclampsia. Br J Pharmacol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daubert DL, Chung MY & Brooks VL. (2007). Insulin resistance and impaired baroreflex gain during pregnancy. AmJPhysiol RegulIntegrComp Physiol 292, R2188–R2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q & Levine BD. (2009). Autonomic circulatory control during pregnancy in humans. SeminReprodMed 27, 330–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman RK, Azar AS, Mulvaney JM, Hinojosa-Laborde C, Haywood JR & Brooks VL. (2009). Baroreflex sensitivity varies during the rat estrous cycle: role of gonadal steroids. AmJPhysiol RegulIntegrComp Physiol 296, R1419–R1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RL. (1978). A quantitative analysis of the physiological role of estradiol and progesterone in the control of tonic and surge secretion of luteinizing hormone in the rat. Endocrinology 102, 142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood JP, Scott EM, Stoker JB, Walker JJ & Mary DA. (2001). Sympathetic neural mechanisms in normal and hypertensive pregnancy in humans. Circulation 104, 2200–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood JP, Stoker JB, Walker JJ & Mary DA. (1998). Sympathetic nerve discharge in normal pregnancy and pregnancy-induced hypertension. JHypertens 16, 617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarino MP, Santos AI, Mota-Carmo M & Costa PF. (2013). Effects of anaesthesia on insulin sensitivity and metabolic parameters in Wistar rats. In Vivo 27, 127–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlan SM & Rahmouni K. (2013). Neuroanatomical determinants of the sympathetic nerve responses evoked by leptin. ClinAutonRes 23, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highman TJ, Friedman JE, Huston LP, Wong WW & Catalano PM. (1998). Longitudinal changes in maternal serum leptin concentrations, body composition, and resting metabolic rate in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 178, 1010–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornnes PJ. (1985). On the decrease of glucose tolerance in pregnancy. A review. Diabete Metab 11, 310–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis SS, Shibata S, Bivens TB, Okada Y, Casey BM, Levine BD & Fu Q. (2012). Sympathetic activation during early pregnancy in humans. JPhysiol 590, 3535–3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AC & Cipolla MJ. (2015). The cerebral circulation during pregnancy: adapting to preserve normalcy. Physiology (Bethesda) 30, 139–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AK & Xue B. (2018). Central nervous system neuroplasticity and the sensitization of hypertension. Nature reviews Nephrology 14, 750–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan JP, Hauguel-De Mouzon S, Lepercq J, Challier JC, Huston-Presley L, Friedman JE, Kalhan SC & Catalano PM. (2002). TNF-alpha is a predictor of insulin resistance in human pregnancy. Diabetes 51, 2207–2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladyman SR, Augustine RA & Grattan DR. (2010). Hormone interactions regulating energy balance during pregnancy. J Neuroendocrinol 22, 805–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladyman SR & Grattan DR. (2004). Region-specific reduction in leptin-induced phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) in the rat hypothalamus is associated with leptin resistance during pregnancy. Endocrinology 145, 3704–3711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladyman SR & Grattan DR. (2017). Region-Specific Suppression of Hypothalamic Responses to Insulin To Adapt to Elevated Maternal Insulin Secretion During Pregnancy. Endocrinology 158, 4257–4269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladyman SR, Tups A, Augustine RA, Swahn-Azavedo A, Kokay IC & Grattan DR. (2009). Loss of hypothalamic response to leptin during pregnancy associated with development of melanocortin resistance. JNeuroendocrinol 21, 449–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lain KY & Catalano PM. (2007). Metabolic changes in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 50, 938–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leturque A, Burnol AF, Ferre P & Girard J. (1984). Pregnancy-induced insulin resistance in the rat: assessment by glucose clamp technique. AmJPhysiol 246, E25–E31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leturque A, Ferre P, Satabin P, Kervran A & Girard J. (1980). In vivo insulin resistance during pregnancy in the rat. Diabetologia 19, 521–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Shi Z, Cassaglia PA & Brooks VL. (2013). Leptin acts in the forebrain to differentially influence baroreflex control of lumbar, renal, and splanchnic sympathetic nerve activity and heart rate. Hypertension 61, 812–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K, Burke SL & Head GA. (2013). Obesity-related hypertension and the role of insulin and leptin in high-fat-fed rabbits. Hypertension 61, 628–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo LD. (1983). Maternal blood volume and cardiac output during pregnancy: a hypothesis of endocrinologic control. AmJPhysiol(RegIntegCompPhysiol) 245, R720–R729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Jaramillo P, Barajas J, Rueda-Quijano SM, Lopez-Lopez C & Felix C. (2018). Obesity and Preeclampsia: Common Pathophysiological Mechanisms. Front Physiol 9, 1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckett BS, Frielle JL, Wolfgang L & Stocker SD. (2013). Arcuate nucleus injection of an anti-insulin affibody prevents the sympathetic response to insulin. AmJPhysiol Heart CircPhysiol 304, H1538–H1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumbers ER & Yu ZY. (1999). A method for determining baroreflex-mediated sympathetic and parasympathetic control of the heart in pregnant and non-pregnant sheep. JPhysiol 515, 555–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark AL. (2013). Selective leptin resistance revisited. AmJPhysiol RegulIntegrComp Physiol 305, R566–R581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masilamani S & Heesch CM. (1997). Effects of pregnancy and progesterone metabolites on arterial baroreflex in conscious rats. AmJPhysiol 272, R924–R934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz C, Lopez-Luna P & Herrera E. (1995). Glucose and insulin tolerance tests in the rat on different days of gestation. BiolNeonate 68, 282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan CJ & Proietto J. (1994). The feto-placental glucose steal phenomenon is a major cause of maternal metabolic adaptation during late pregnancy in the rat. Diabetologia 37, 976–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonogaki K (2000). New insights into sympathetic regulation of glucose and fat metabolism. Diabetologia 43, 533–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranjape SA, Chan O, Zhu W, Horblitt AM, Grillo CA, Wilson S, Reagan L & Sherwin RS. (2011). Chronic reduction of insulin receptors in the ventromedial hypothalamus produces glucose intolerance and islet dysfunction in the absence of weight gain. AmJPhysiol EndocrinolMetab 301, E978–E983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranjape SA, Chan O, Zhu W, Horblitt AM, McNay EC, Cresswell JA, Bogan JS, McCrimmon RJ & Sherwin RS. (2010). Influence of insulin in the ventromedial hypothalamus on pancreatic glucagon secretion in vivo. Diabetes 59, 1521–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pricher MP, Freeman KL & Brooks VL. (2008). Insulin in the brain increases gain of baroreflex control of heart rate and lumbar sympathetic nerve activity. Hypertension 51, 514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior LJ, Eikelis N, Armitage JA, Davern PJ, Burke SL, Montani JP, Barzel B & Head GA. (2010). Exposure to a high-fat diet alters leptin sensitivity and elevates renal sympathetic nerve activity and arterial pressure in rabbits. Hypertension 55, 862–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes LM, Usselman CW, Davenport MH & Steinback CD. (2018). Sympathetic Nervous System Regulation in Human Normotensive and Hypertensive Pregnancies. Hypertension 71, 793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhea EM, Rask-Madsen C & Banks WA. (2018). Insulin transport across the blood-brain barrier can occur independently of the insulin receptor. J Physiol 596, 4753–4765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JM & Bell MJ. (2013). If we know so much about preeclampsia, why haven’t we cured the disease? J Reprod Immunol 99, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson SC, Hunter S, Boys RJ & Dunlop W. (1989). Serial study of factors influencing changes in cardiac output during human pregnancy. AmJPhysiol 256, H1060–H1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha JK, Xia J, Grondin JM, Engle SK & Jakubowski JA. (2005). Acute hyperglycemia induced by ketamine/xylazine anesthesia in rats: mechanisms and implications for preclinical models. ExpBiolMed(Maywood) 230, 777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano Y, Ito S, Yoneda M, Nagasawa K, Matsuura N, Yamada Y, Uchinaka A, Bando YK, Murohara T & Nagata K. (2016). Effects of various types of anesthesia on hemodynamics, cardiac function, and glucose and lipid metabolism in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311, H1360–h1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer L, Brand CL, Hansen BF, Ribel U, Shaw AC, Slaaby R & Sturis J. (2008). A novel high-affinity peptide antagonist to the insulin receptor. BiochemBiophysResCommun 376, 380–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scow RO, Chernick SS & Brinley MS. (1964). HYPERLIPEMIA AND KETOSIS IN THE PREGNANT RAT. Am J Physiol 206, 796–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeber RM, Smith JT & Waddell BJ. (2002). Plasma leptin-binding activity and hypothalamic leptin receptor expression during pregnancy and lactation in the rat. BiolReprod 66, 1762–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z & Brooks VL. (2015). Leptin differentially increases sympathetic nerve activity and its baroreflex regulation in female rats: role of oestrogen. JPhysiol 593, 1633–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z, Cassaglia PA, Gotthardt LC & Brooks VL. (2015a). Hypothalamic Paraventricular and Arcuate Nuclei Contribute to Elevated Sympathetic Nerve Activity in Pregnant Rats: Roles of Neuropeptide Y and alpha-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone. Hypertension 66, 1191–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z, Cassaglia PA, Pelletier NE & Brooks VL. (2019). Sex differences in the sympathoexcitatory response to insulin in obese rats: role of neuropeptide Y. J Physiol 597, 1757–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z, Li B & Brooks VL. (2015b). Role of the Paraventricular Nucleus of the Hypothalamus in the Sympathoexcitatory Effects of Leptin. Hypertension 66, 1034–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siani A, Strazzullo P, Giorgione N, De Leo A & Mancini M. (1990). Insulin-induced increase in heart rate and its prevention by propranolol. EurJClinPharmacol 38, 393–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradley FT, Palei AC & Granger JP. (2015). Increased risk for the development of preeclampsia in obese pregnancies: weighing in on the mechanisms. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 309, R1326–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker SD & Bardgett ME. (2007). Hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus contributes to the sympathoexcitatory effects of hyperinsulinemia. Hypertension 50, e79. [Google Scholar]

- Storlien LH, Lam YY, Wu BJ, Tapsell LC & Jenkins AB. (2016). Effects of dietary fat subtypes on glucose homeostasis during pregnancy in rats. Nutr Metab (Lond) 13, 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo ML, Spuch C, Carro E & Senaris R. (2011). Hyperphagia and central mechanisms for leptin resistance during pregnancy. Endocrinology 152, 1355–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urayama A & Banks WA. (2008). Starvation and triglycerides reverse the obesity-induced impairment of insulin transport at the blood-brain barrier. Endocrinology 149, 3592–3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward KR, Bardgett JF, Wolfgang L & Stocker SD. (2011). Sympathetic response to insulin is mediated by melanocortin 3/4 receptors in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Hypertension 57, 435–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]