Abstract

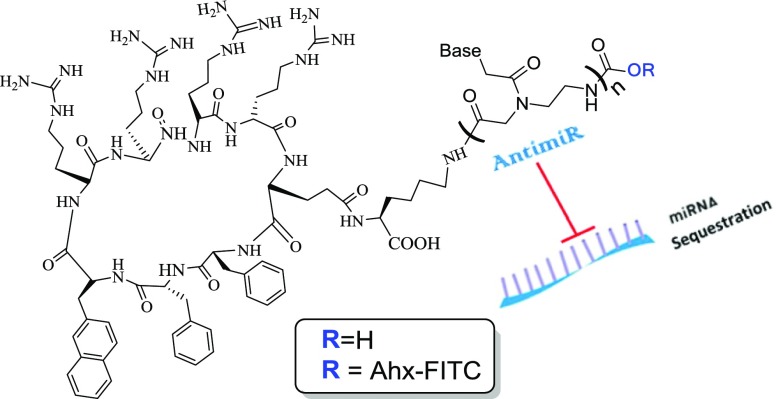

Efficient delivery of nucleic acids into cells still remains a great challenge. Peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) are DNA analogues with a neutral backbone and are synthesized by solid phase peptide chemistry. This allows a straightforward synthetic route to introduce a linear short peptide (a.k.a. cell-penetrating peptide) to the PNA molecule as a means of facilitating cellular uptake of PNAs. Herein, we have devised a synthetic route in which a cyclic peptide is prepared on a solid support and is extended with the PNA molecule, where all syntheses are accomplished on the solid phase. This allows the conjugation of the cyclic peptide to the PNA molecule with the need of only one purification step after the cyclic peptide–PNA conjugate (C9–PNA) is cleaved from the solid support. The PNA sequence chosen is an antimiR-155 molecule that is complementary to mature miR-155, a well-established oncogenic miRNA. By labeling C9–PNA with fluorescein isothiocyanate, we observe efficient cellular uptake into glioblastoma cells (U87MG) at a low concentration (0.5 μM), as corroborated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis and confocal microscopy. FACS analysis also suggests an uptake mechanism that is energy-dependent. Finally, the antimiR activity of C9–PNA was shown by analyzing miR155 levels by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and by observing a reduction in cell viability and proliferation in U87MG cells, as corroborated by XTT and colony formation assays. Given the added biological stability of cyclic versus linear peptides, this synthetic approach may be a useful and straightforward approach to synthesize cyclic peptide–PNA conjugates.

Introduction

Downregulation of RNA by chemically modified oligonucleotides (ODNs) has shown great promise in the clinic with recent FDA approvals of several ODN-based drugs for the treatment of rare orphan diseases. One such drug is Eteplirsen;1 a phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer (PMO)-based exon-skipping drug (EXONDYS 51) that is administered to children suffering from Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). Surprisingly, Eteplirsen is simply modified with a short polyethylene glycol (PEG) linker and exerts therapeutic activity after systemic administration. In recent years, there has been considerable effort put forth to improve the therapeutic potential of PMOs by conjugating specific cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) (peptide–PMO conjugates).2 PMO is a DNA mimic that consists of a morpholine ring that replaces the natural ribose. It has a neutral backbone and therefore avidly binds complementary RNA as the electrostatic repulsion between both strands (PMO and RNA) are nonexistent. Another DNA mimic that has a neutral backbone is PNA (peptide nucleic acid).3

PNA is synthesized by peptide chemistry, and therefore the introduction of a CPP to either the C- or N-terminus of the PNA sequence is straightforward.4 In addition, as CPPs are typically positively charged, there is less concern of electrostatic interactions between the CPP and the PNA (as opposed to negatively charged ODNs).

In the context of cancer therapeutics, PNAs have been shown to target cancer cells by (1) modulating splicing at the pre-mRNA level5 and by (2) sequestering oncogenic miRNAs6 and mRNAs.

In vivo, a guanidium backbone-modified PNA was shown as an effective antisense molecule targeting EGFr mRNA.7 In addition, a pH-responsive PNA conjugate (pHLIP) was shown as an effective anticancer agent targeting the oncogenic miR-155 (antimiR PNA).6a

CPPs are widely used for the cellular delivery of therapeutic agents. Peptides, however, are prone to degradation by peptidases and proteases. To increase peptide stability, several approaches have been utilized, such as the use of unnatural amino acids, d-amino acids, and peptide cyclization.8 Peptide cyclization for PNA delivery was recently reported by forming a hairpin structure of a gamma-PNA–Tat peptide–gamma-PNA extended with a gamma-PNA overhang. Using this approach, one may design other CPPs on such a hairpin scaffold, thus avoiding the need for covalent peptide cyclization.9 In an earlier study, PNA–cyclic peptide conjugates were obtained on the solid support by the formation of an S–S bond by designing peptides with selected positions of cysteines on the peptide sequence.10

Herein, we have devised a synthetic methodology to synthesize a cyclic peptide (C9) that is conjugated to the PNA via a classical amide bond where all syntheses are carried out on the solid support. This cyclic CPP was reported in the literature as the one that permeates cells by endocytosis and is by far more effective for cellular delivery than classical CPPs such as Tat and nona-arginine (R9).11 We have conjugated C9 to a PNA sequence that targets the mature form of oncogenic miRNA-155. In this report, we have studied the cellular uptake and biological activity of C9–PNA in glioblastoma cancer cells (U87MG).

Results and Discussion

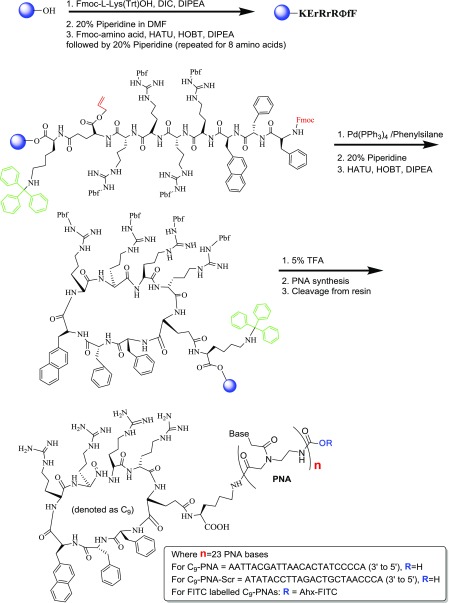

Peptide cyclization on the solid support followed by on-resin PNA synthesis was accomplished as described in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. Solid-Phase Synthesis of C9–PNAs.

The peptide of choice is 9-mer that is designed in the following manner: the amino acid at the C-terminus is l-lysine with its ε-amine protected with a trityl group. This allows the extension of the peptide via the α-amine and post on-resin cyclization, the introduction of the PNA monomers at the ε-amine following trityl group deprotection. The remaining 8-mer peptide is the peptide that is then cyclized on the solid support. This cyclic peptide has several features: (1) it has a hydrophobic (FfΦ, where Φ = l-2-naphthylalanine, F = l-phe, and f = d-phe) and a hydrophilic (RrRr, four arginines with alternating chirality of L and D) region; (2) it contains both natural and unnatural amino acids (e.g., l-2-naphthylalanine); and (3) it has been reported to be about 20-fold more efficient as a CPP in comparison to classical CPPs such as Tat and nona-l-arginine (R9).11 Cyclization on the solid support is achieved after selectively deprotecting the α-amine (Fmoc-protected) of l-phe (F) and the α-carboxylic acid (allyl-protected) of l-glu (E); both protecting groups are orthogonal to the trityl group on the ε-amine of l-lys. Once these functional groups are revealed, cyclization on the resin is carried out using standard coupling reagents (2-(1H-7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyl uronium hexafluorophosphate methanaminium (HATU), hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBT), and diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA)).

As a PNA sequence, we chose the one that is fully complementary to the mature miR-155 oncogenic miRNA. In addition, we designed a scrambled sequence to serve as a control (Table 1). This scrambled sequence consists of the same amount of four PNA monomers (as anti-miR155 PNA) and the sequence was found not to have a full complementarity to any human transcript, as verified by BLAST analysis. An additional control was synthesized that consisted of four d-lysines as the CPP. There were two criteria for this choice: (1) this peptide has four positive charges in physiological pH as does the cyclic C9 peptide (four Arg); (2) this peptide is also stable in biological medium because of the chirality (D) of all four amino acids. As an additional control, dK4–PNA was also prepared with the scrambled PNA sequence (Table 1). dK4–PNA conjugates have also been previously reported as cancer cell-permeable at a 1 μM concentration.12 Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) labeling at the N-terminus of both C9–PNA and dK4–PNA was carried out to allow us to follow the cellular uptake of both PNAs that differ only in their peptide sequence (Table 1).

Table 1. PNA Conjugates as antimiRs (antimiR-155) with/without FITC Labeling and Their Corresponding ESI Mass Assignmentsa.

| name | description | construct (N′ to C′) | mass (daltons) (calc) | mass (daltons)(found) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dK4–PNA | PNA conjugated to dK4 | 5′-ACCCCTATCACAATTAGCATTAA-3′-dK4 | 6671.70 | 6674.20 |

| dK4–PNA-Scr | scrambled PNA conjugated to dK4 | 5′-ACCCAATCGTCAGATTCCATATA-3′-dK4 | 6671.70 | 6676.70 |

| dK4–PNA–FITC | PNA conjugated to dK4 and FITC | FITC-Ahx-5′-ACCCCTATCACAATTAGCATTAA-3′-dK4 | 7174.24 | 7177.56 |

| C9–PNA | PNA conjugated to C9 | 5′-ACCCCTATCACAATTAGCATTAA-3′-C9 | 7513.63 | 7516.5 |

| C9–PNA-Scr | scrambled PNA conjugated to C9 | 5′-ACCCAATCGTCAGATTCCATATA-3′-C9 | 7513.63 | 7517.34 |

| C9–PNA–FITC | PNA conjugated to C9 and FITC | FITC-Ahx-5′-ACCCCTATCACAATTAGCATTAA-3′-C9 | 8022.22 | 8018.76 |

C9 = cyclic-(F–f−Φ–R–r–R–r−γE)K and Ahx = 6-aminohexanoic acid

miR-155 is highly expressed in a variety of cancers.13 We chose glioblastoma cells (U87MG) as the means to follow antimiR activity and cellular uptake of the PNA conjugates. These cells express high levels of miR-155 and are not easy to transfect.14 To evaluate the antisense (antimiR) activity of the PNA conjugates, we followed the effect of PNA conjugate incubation with U87MG cells by following the expression levels of miR-155. As shown by Gait and co-workers,15 PNA antimiRs sequester mature miRNA in cells. Thus, isolating miRNAs from cells after PNA treatment is anticipated to result in low levels of isolated miRNA because of PNA sequestration (and not miRNA degradation). This is related to the chemistry of PNA that does not evoke RNAse H activity.

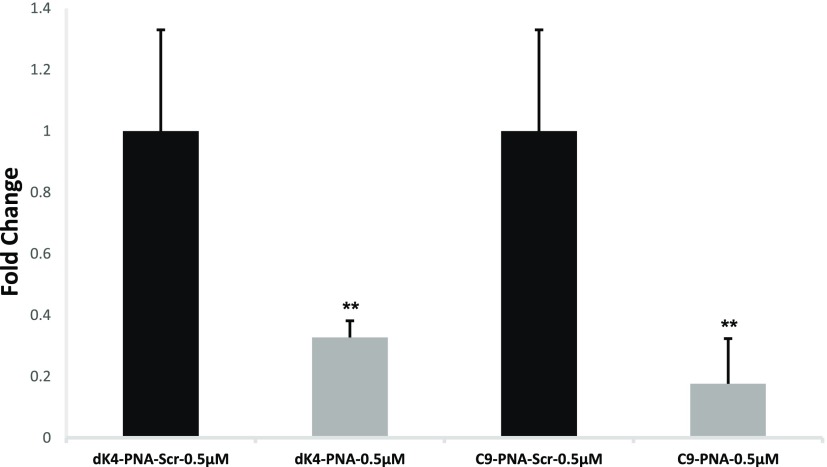

U87MG cells were treated with either C9–PNA or dK4–PNA (0.5 μM). Scrambled PNAs were also tested as controls (C9–PNA-Scr or dK4–PNA-Scr). After 24 h, total miRNA was isolated and cDNA was prepared from 1 μg of total miRNA using the qScript microRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit. The expression of miR-155 was then evaluated by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (in triplicates, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

miR-155 expression following incubation of PNA conjugates (0.5 μM) in U87MG cells for 24 h at 37 °C. miR-155 is shown in comparison to scrambled PNA controls. **P value < 0.01.

In comparison to scrambled controls, both PNA conjugates were shown to sequester miR-155, with the C9–PNA conjugate showing over 80% decrease in miR-155 in comparison to the scrambled control.

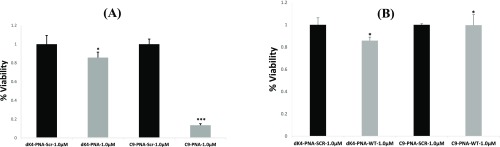

Next, we examined cell viability by the XTT assay after treating U87MG cells with 1 μM of PNA conjugates (Figure 2). U87MG cells were incubated with PNA conjugates for 72 h at 37 °C in triplicates in 96-well plates. As shown in Figure 2a, over an 80% reduction in cell viability was observed for cells treated with C9–PNA in comparison to the C9–PNA-Scr control. Both C9–PNA and C9–PNA-Scr had negligible effects on the viability of THESCs uterus (immortalized fibroblast) cells (Figure 2b) as well as on normal uterus human fibroblast cells produced from a patient (Nf08 uterus, Figure S9).

Figure 2.

Cell viability for U87GM cells and THSCs cells as determined by the XTT assay. (a) U87GM cells were treated with 1 μM PNA conjugates for 72 h at 37 °C (in triplicates in 96-well plates). Viability is shown in comparison to scrambled PNA controls. *P value < 0.05, ***P value < 0.001. (b) THSCs cells were treated with 1 μM PNA conjugates for 72 h at 37 °C (in triplicates in 96-well plates). Viability is shown in comparison to scrambled PNA controls. *P value < 0.05.

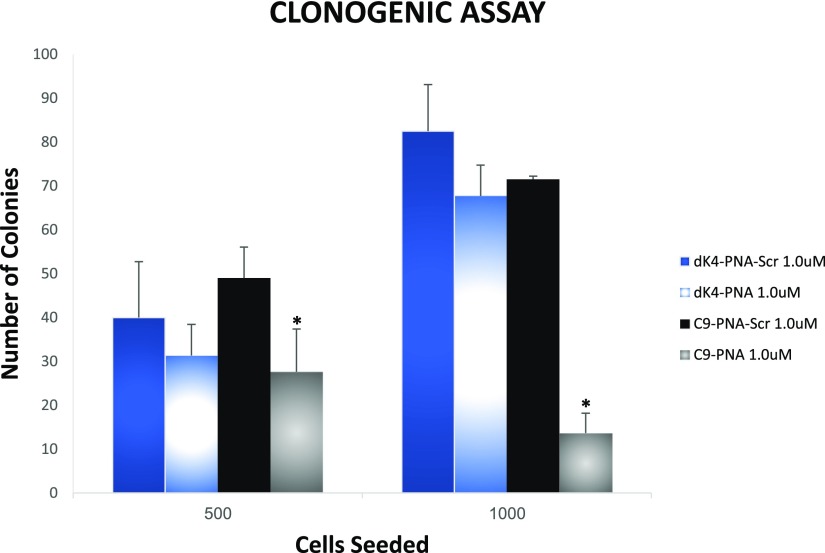

To examine the effect on cell survival and proliferation, we seeded U87MG glioblastoma cells in six-well plates, in the presence of either dK4–PNA and C9–PNA or the scrambled control PNAs (1.0 μM) for 24 h. After 2 weeks, the cell colonies were counted (Figure 3). The graph represents colony numbers in the triplicate plates. A substantial decrease in colony formation was observed for C9–PNA providing further support for the anticancer activity exerted by C9–PNA in comparison with dK4–PNA and the scrambled controls.

Figure 3.

C9–PNA reduces the colony survival of U87MG glioblastoma cells. Colony formation assay of cells treated with 1.0 μM of either dK4–PNA and C9–PNA or scrambled controls (dK4–PNA-Scr and C9–PNA-Scr). After 2 weeks, the plates were fixed and stained, and the colonies were counted (in triplicates). *P value < 0.05.

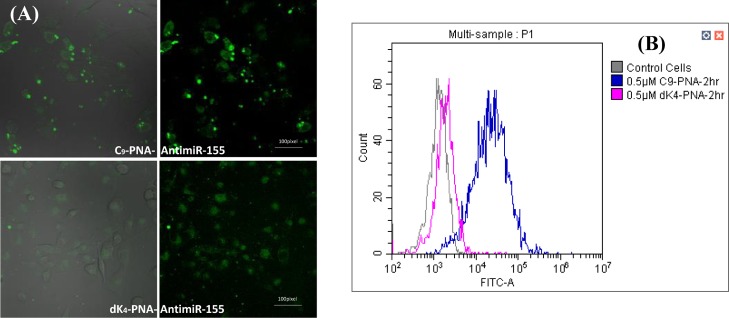

To explore the cellular uptake and distribution, both FITC-labeled PNAs (C9–PNA–FITC and dK4–PNA–FITC) were incubated (0.5 μM PNA for 3 h) with U87MG cells. Live cell images of both PNAs are shown in Figure 4A. Clearly, C9–PNA–FITC shows a dominant fluorescence in the cytoplasm which is significantly higher than that of dK4–PNA–FITC. Some punctate green fluorescence is also observed for C9–PNA–FITC; these foci are inside cells, as verified by the cross-sectional confocal images (Supporting Information, Figure S7). To further quantify the PNA–FITC uptake into U87MG cells, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis for both PNAs was performed after a 2 h incubation period at the same PNA concentration (0.5 μM). A clear and dominant change in FITC fluorescence is seen for C9–PNA–FITC (Figure 4B), whereas almost no change in fluorescence is seen for dK4–PNA–FITC. These results coincide with the confocal images presented in Figure 4A.

Figure 4.

C9–PNA–FITC shows efficient cellular uptake into U87MG cells. (A) Confocal images of C9–PNA–FITC and dK4–PNA–FITC (at 0.5 μM) after a short incubation of 3 h at 37 °C. (B) FACS analysis of C9–PNA–FITC and dK4–PNA–FITC (at 0.5 μM) cellular uptake into U87MG cells after 2 h of incubation at 37 °C.

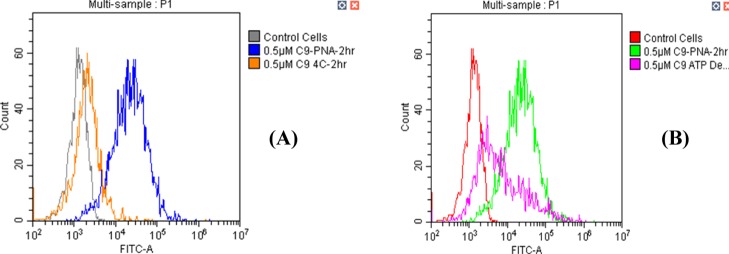

The cyclic peptide used in this study was reported by Qian and co-workers11 to enter cells via an energy-dependent endosomal mechanism. It is not clear, a priori, whether or not the introduction of the PNA sequence affects the uptake mechanism of this cyclic peptide. To answer this question, a series of flow cytometry experiments were performed. U87MG cells were incubated for 2 h with 0.5 μM C9–PNA–FITC in the presence of either 10 mM NaN3/10 mM 2-deoxy-D-glucose at 37 °C or at 4 °C. Both conditions deplete ATP that is required for endocytosis.11 As shown in Figure 5, in both conditions, a clear decrease in cellular uptake was observed. These results suggest that the cyclic peptide retains its energy-dependent cellular uptake mechanism even after PNA conjugation.

Figure 5.

C9–PNA–FITC cellular uptake is energy-dependent. C9-PNA–FITC uptake into U87MG cells after a 2 h incubation (A) at 4 °C or (B) at 37 °C with 10 mM NaN3/10 mM 2-deoxy-d-glucose.

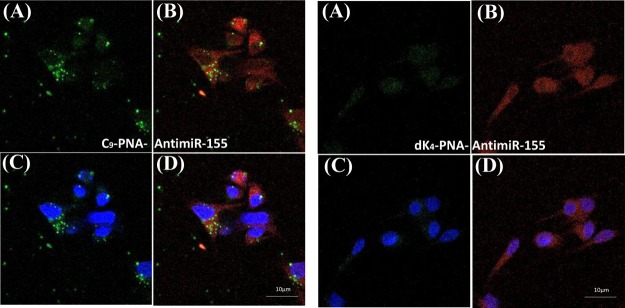

To further elaborate on the cellular uptake into U87MG cells, we stained the cells with Lyso-Tracker Red (staining lysosomes) and Hoechst (staining nuclei), following a 3 h incubation with C9-PNA–FITC or dK4–PNA–FITC, to follow the cellular localization of FITC-labeled PNAs. As shown in Figure 6, there was a negligible uptake of dK4–PNA–FITC. In contrast, we observed strong punctate green signals of C9–PNA–FITC that are predominantly found in lysosomes and, to a lesser extent, in nuclei.

Figure 6.

C9–PNA–FITC cellular uptake is predominantly in the cytoplasm. Confocal microscopy images of U87MG glioblastoma cells incubated with C9–PNA–FITC or dK4–PNA–FITC (at 0.5 μM) after an incubation of 3 h at 37 °C. (A) PNA–FITC alone (green); (B) overlay of PNA–FITC (green) with Lyso-Tracker Red (red) staining of lysosome (C); overlay of PNA–FITC (green) with Hoechst (blue) staining of nuclei; and (D) overlay of both stains with PNA–FITC.

The cross-sectional confocal images (Supporting Information, Figure S8) further confirm the presence of C9–PNA–FITC inside cells. These results further support the endocytosis-dependent mechanism of uptake for C9–PNA–FITC.

In this study, we have shown efficient blocking of miR-155 by C9–PNA conjugates. We designed and synthesized the C9 peptide from a solid support followed by PNA–antimiR-155. C9–PNA shows effective cellular uptake in comparison to the dK4–PNA conjugate, which results in higher bioavailability of PNA–antimiR-155 in the cytoplasm. Indeed, a higher effect was achieved on sequestering miR-155 as well as in inhibiting cell proliferation by C9–PNA in comparison to dK4–PNA.

We have shown that the cyclic peptide retains its energy-dependent cellular uptake mechanism even after PNA conjugation. Using this synthetic strategy, one may covalently link the C9 peptide to any PNA sequence, thus providing the PNA–peptide conjugate with high stability and cellular uptake.

Experimental Procedure

Materials

Fmoc-PNA monomers were purchased from PolyOrg, Inc. (USA) and used as received. Amino acids (Fmoc-Lys-(BOC) (K), Fmoc-Lys(MTT)OH (K), Fmoc-d-Arg(pbf)-OH (r), Fmoc-Arg(pbf)-OH (R), Fmoc-l-2-naphthylalanine (ϕ), Fmoc-d-phenylalanine (f), Fmoc-phenylalanine (F)), and N-9-fluoromethoxycarbonyl chloride were purchased from GL Biochem (Shanghai) Ltd. N-Fmoc-l-glutamic acid 1-allyl ester, 98%, was purchased from Alfa Aesar. Ahx was purchased from Acros Organics. Tetrakis(triphenylphosphine) was purchased from Strem Chemicals. Phenylsilane was purchased from Merck. FITC was purchased from Chem-Impex Int’l Inc. Solvents and reagents for peptide chemistry were purchased from Bio-lab (Israel).

Solid-Phase Synthesis of Linear PNA–Peptide Conjugates

PNAs (as anitimiR-155 and scrambled sequence) with a short dK4 peptide were synthesized on the solid phase (as full constructs of peptide and PNA, with/without FITC) in a continuous manner.5 NovaSynTGA resin (Merck, Germany, 0.25 mmol/g) was used as the solid support material, and PNA cleavage leads to the free carboxylic acid at the C-terminus. For FITC labeling, Fmoc-Ahx was introduced on the N-terminus of the PNA, followed by Fmoc deprotection and addition of 20 μmol FITC and 40 μmol DIEA in 0.2 mL dimethylformamide (DMF) for 48 h (×2). The addition of a linker, Fmoc-Ahx-OH, between the PNA and FITC prevents its binding to the α-NH position, thereby avoiding its elimination during sequence cleavage.16

C9–PNA Conjugate Synthesis and FITC Labeling

The linear version of the C9 peptide was synthesized as described above (linear form). After the addition of the last amino acid (Phe, F), the allyl group of (Glu, E) on the C-terminal was removed by the treatment of the resin-bound peptide with Pd(PPh3)4 and phenylsilane (0.1 and 24 equiv, respectively) in 0.02 M anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM) (2 × 20 min). The N-terminal Fmoc group (Phe, F) was then removed by treatment with 20% piperidine in DMF, and the peptide was cyclized on the solid support by treatment with HATU (6 equiv), HOBT (6 equiv), and DIPEA (10 equiv) in 0.15 M DMF for 3 h. To allow the introduction of the PNA sequence to the cyclic peptide on the solid support, the first amino acid on the C-terminus (N-α-Fmoc-N-ε-trityl-l-lysine) was used as a handle (Scheme 1). After the on-resin cyclization of the peptide, the trityl group was selectively deprotected using 5% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in dry DCM, followed by the addition of Fmoc-PNA-monomers as previously described.5

Cleavage of PNAs from Resin

The antimiR-155 peptide–PNA conjugates and antimiR-155 PNA labeled with FITC were deprotected and released from the resin (as a free acid on C-terminus) by treatment with 90:10 (v/v) TFA/m-cresol for the dK4–PNAs and with 82:5:5:5:5:2.5 (v/v) TFA/thioanisole/water/phenol/ethanedithiol for C9–PNAs for 3 h. The PNA conjugates were triturated with cold ethyl ether, and the precipitate was collected. The PNA samples were analyzed on RP-HPLC (Shimadzu LC2010), using a semipreparative C18 reverse-phase column (Phenomenex, Jupiter 300 Å) at a flow rate of 4 mL/min. Mobile phase: 0.1% TFA in H2O (A) and acetonitrile (B) (see Supporting Information, Figures S1 and S5). The authenticity of each peptide–PNA conjugate was confirmed by using a ThermoQuest Finnigan LCQ-Duo ESI mass spectrometer (Table 1, and Supporting Information Figures S2, S3, and S6). The final solutions were measured at 260 nm and calculated based on the extinction coefficients of the nucleobases.

Cell Culture

All cell lines (U87MG, Nf08 uterus, and THESCs uterus) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin, and streptomycin.

miR-155 Reverse Transcription Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total microRNA was isolated from cells using the mirPremier microRNA Isolation Kit from Sigma, and cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg RNA using the qScript microRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit in a final volume of 20 μL according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Quantabio). Real-time PCR was performed on a real time-PCR Connect ST System BioRad, and PCR parameters were adjusted as recommended by the manufacturer (PerfeCTa SYBR Green SuperMix, Quantabio). Primers for miR-155 were purchased from Hylabs (See Supporting Information, Table S1)

Cell Proliferation Assay

Cells [U87MG glioblastoma cells, THESCs uterus cells, and Nf08 uterus cells (3 × 103)] were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated for 24 h for cell attachment. Next, dK4–PNA (and its scrambled control) and C9–PNA (and its scrambled control) were added after medium replacement and incubated (37 °C, humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2) for 72 h. Cell proliferation was then measured using the XTT (sodium 3-[1-(phenylamino-carbonyl)-3,4-tetrazolium]-bis(4-methoxy-6-nitro) benzene sulfonic acid hydrate)] proliferation assay, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Biological Industries, Israel).

Clonogenic Assay

After 24 h of transfection, 1000 and 500 U87MG cells were seeded in triplicates in six-well plates with 2 mL of medium (DMEM, 10% FCS). After 14 days, the cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution for 10 min, stained with 1% methylene blue solution, and counted.

Live Cell Imaging

Twelve hours prior to FITC-labeled PNA conjugate addition, U87MG cells were plated on an eight-well chamber removable microscope-sterilized glass slide (NBT New Bio Technology Ltd.). The cells were grown until reaching 70–80% confluence. Before adding the PNAs, the medium was replaced and the cells were incubated (37 °C, humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2) with 0.5 μM of dK4–PNA–FITC or C9–PNA–FITC in complete medium, over a period of 3 h, followed by two washings with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For negative control, untreated cells were used. Cell fluorescence analysis was performed using a confocal laser scanning microscope, Olympus FV300.

Cell Staining for Colocalization Studies

The initial procedure was carried out as described for live cell imaging. For lysosome staining, a solution of 50 nM Lyso-Tracker Red (LysoTracker Red DND-99 1 mM Eugene, Oregon USA) was prepared in a cell culture medium and was added to the cells and incubated at 37 °C for 20–30 min. To achieve nuclear staining, the cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with 0.01 mM Hoechst (bis-benzimide H 33342 trihydrochloride, Merck) at 37 °C for 15 min. Thereafter, the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde (Biolab, Israel) and washed three times with PBS prior to imaging. Cell fluorescence analysis was performed using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal laser scanning system (Carl Zeiss Micro Imaging GmbH, Jena, Germany).

FACS Analysis of FITC-Labeled PNA Conjugates

Flow cytometry studies were performed by plating 2.0 × 105 U87MG cells/well prepared in six-well plates, and the cells were allowed to adhere overnight under normal culture conditions. The medium (DMEM, 10% FCS) was replaced and the cells were incubated (37 °C, humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2) with 0.5 μM of dK4–PNA–FITC or with C9–PNA–FITC in a complete medium, over 2 h. The medium with the PNA conjugate was removed, and the cells were washed with PBS. Then, the cells were detached from the wells with 400 μL of 0.25% trypsin– ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid solution for 5 min at room temperature. The cells were collected into 1.5 mL polypropylene vials and then sedimented for 5 min at 4.186g at room temperature. The supernatant was discarded. The samples were resuspended with 800 μL cold PBS, filtered by Falcon cell strainers, 70 μm nylon, and analyzed by a Beckman Coulter CytoFLEX flow cytometer (488 nm excitation laser), with gating based on normalized fluorescence of untreated cells to evaluate the percentage of cells which internalized the fluorescently labeled PNA conjugates. To assess the endocytosis-dependent uptake of C9–PNA–FITC, the cells were pretreated with endocytosis inhibitors. U87MG cells were treated with C9–PNA–FITC (0.5 μM) for 2 h at 37 °C in the presence of 10 mM NaN3 and 2-deoxy-d-glucose or at 4 °C prior to flow cytometry analysis. Control cells were incubated with C9–PNA–FITC (0.5 μM) without the addition of endocytosis inhibitors or incubation at low temperature (4 °C). The cell treatment and uptake mechanism were followed by FACS analysis as mentioned above, using two repeats for each experimental condition.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant no. 476/17). E.Y. acknowledges the David R. Bloom Center for Pharmacy and the Alex Grass Center for Drug Design and Synthesis of Novel Therapeutics for financial support. THESCs uterus cells and Nf08 uterus cells were generously provided by Prof. R. Reich (Hebrew University).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PNA

peptide nucleic acid

- CPP

cell-penetrating peptide

- WT

wild type

- SCR

scrambled

- C9

cyclic-(F-f-Φ-R-r-R-r-γE)K

- PMO

phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer

- DMD

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- pHLIP

pH low insertion peptide

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.9b01697.

HPLC chromatograms, mass spectra, primer sequences, cross-sectional confocal images, and XTT assay (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lim K. R.; Maruyama R.; Yokota T. Eteplirsen in the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2017, 11, 533–545. 10.2147/dddt.s97635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Betts C.; Saleh A. F.; Arzumanov A. A.; Hammond S. M.; Godfrey C.; Coursindel T.; Gait M. J.; Wood M. J. A. Pip6-PMO, A New Generation of Peptide-oligonucleotide Conjugates With Improved Cardiac Exon Skipping Activity for DMD Treatment. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2012, 1, e38 10.1038/mtna.2012.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Clayton N. P.; Nelson C. A.; Weeden T.; Taylor K. M.; Moreland R. J.; Scheule R. K.; Phillips L.; Leger A. J.; Cheng S. H.; Wentworth B. M. Antisense Oligonucleotide-mediated Suppression of Muscle Glycogen Synthase 1 Synthesis as an Approach for Substrate Reduction Therapy of Pompe Disease. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2014, 3, e206 10.1038/mtna.2014.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Echigoya Y.; Nakamura A.; Nagata T.; Urasawa N.; Lim K. R. Q.; Trieu N.; Panesar D.; Kuraoka M.; Moulton H. M.; Saito T.; Aoki Y.; Iversen P.; Sazani P.; Kole R.; Maruyama R.; Partridge T.; Takeda S. i.; Yokota T. Effects of systemic multiexon skipping with peptide-conjugated morpholinos in the heart of a dog model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114, 4213–4218. 10.1073/pnas.1613203114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Gait M. J.; Arzumanov A. A.; McClorey G.; Godfrey C.; Betts C.; Hammond S.; Wood M. J. A. Cell-Penetrating Peptide Conjugates of Steric Blocking Oligonucleotides as Therapeutics for Neuromuscular Diseases from a Historical Perspective to Current Prospects of Treatment. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2019, 29, 1–12. 10.1089/nat.2018.0747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Goyenvalle A.; Babbs A.; Powell D.; Kole R.; Fletcher S.; Wilton S. D.; Davies K. E. Prevention of Dystrophic Pathology in Severely Affected Dystrophin/Utrophin-deficient Mice by Morpholino-oligomer-mediated Exon-skipping. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 198–205. 10.1038/mt.2009.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Greenberg D. E.; Marshall-Batty K. R.; Brinster L. R.; Zarember K. A.; Shaw P. A.; Mellbye B. L.; Iversen P. L.; Holland S. M.; Geller B. L. Antisense Phosphorodiamidate Morpholino Oligomers Targeted to an Essential Gene Inhibit Burkholderia cepacia Complex. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 201, 1822–1830. 10.1086/652807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Hammond S. M.; Hazell G.; Shabanpoor F.; Saleh A. F.; Bowerman M.; Sleigh J. N.; Meijboom K. E.; Zhou H.; Muntoni F.; Talbot K.; Gait M. J.; Wood M. J. A. Systemic peptide-mediated oligonucleotide therapy improves long-term survival in spinal muscular atrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016, 113, 10962–10967. 10.1073/pnas.1605731113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Jearawiriyapaisarn N.; Moulton H. M.; Buckley B.; Roberts J.; Sazani P.; Fucharoen S.; Iversen P. L.; Kole R. Sustained dystrophin expression induced by peptide-conjugated morpholino oligomers in the muscles of mdx mice. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 1624–1629. 10.1038/mt.2008.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Jearawiriyapaisarn N.; Moulton H. M.; Sazani P.; Kole R.; Willis M. S. Long-term improvement in mdx cardiomyopathy after therapy with peptide-conjugated morpholino oligomers. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 85, 444–453. 10.1093/cvr/cvp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Lai S.-H.; Stein D. A.; Guerrero-Plata A.; Liao S.-L.; Ivanciuc T.; Hong C.; Iversen P. L.; Casola A.; Garofalo R. P. Inhibition of respiratory syncytial virus infections with morpholino oligomers in cell cultures and in mice. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 1120–1128. 10.1038/mt.2008.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Lebleu B.; Moulton H. M.; Abes R.; Ivanova G. D.; Abes S.; Stein D. A.; Iversen P. L.; Arzumanov A. A.; Gait M. J. Cell penetrating peptide conjugates of steric block oligonucleotides. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2008, 60, 517–529. 10.1016/j.addr.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l Leger A. J.; Mosquea L. M.; Clayton N. P.; Wu I.-H.; Weeden T.; Nelson C. A.; Phillips L.; Roberts E.; Piepenhagen P. A.; Cheng S. H.; Wentworth B. M. Systemic Delivery of a Peptide-Linked Morpholino Oligonucleotide Neutralizes Mutant RNA Toxicity in a Mouse Model of Myotonic Dystrophy. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2013, 23, 109–117. 10.1089/nat.2012.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m Ma W.; Lin Y.; Xuan W.; Iversen P. L.; Smith L. J.; Benchimol S. Inhibition of p53 expression by peptide-conjugated phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers sensitizes human cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drugs. Oncogene 2012, 31, 1024–1033. 10.1038/onc.2011.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n Morse M. A.; Hobeika A.; Serra D.; Aird K.; McKinney M.; Aldrich A.; Clay T.; Mourich D.; Lyerly H. K.; Iversen P. L.; Devi G. R. Depleting regulatory T cells with arginine-rich, cell-penetrating, peptide-conjugated morpholino oligomer targeting FOXP3 inhibits regulatory T-cell function. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 30–37. 10.1038/cgt.2011.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o Moulton H. M.; Moulton J. D. Morpholinos and their peptide conjugates: Therapeutic promise and challenge for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2010, 1798, 2296–2303. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; p Passini M. A.; Gan L.; Wood J. A.; Yao M.; Estrella N. L.; Treleaven C. M.; Wentworth B. M.; Charleston J. S.; Rutkowski J. V.; Hanson G. J. Development of PPMO for the Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Neurology 2018, 90. [Google Scholar]; q Wu B.; Moulton H. M.; Iversen P. L.; Jiang J.; Li J.; Li J.; Spurney C. F.; Sali A.; Guerron A. D.; Nagaraju K.; Doran T.; Lu P.; Xiao X.; Lu Q. L. Effective rescue of dystrophin improves cardiac function in dystrophin-deficient mice by a modified morpholino oligomer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 14814–14819. 10.1073/pnas.0805676105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; r Yin H.; Moulton H. M.; Betts C.; Merritt T.; Seow Y.; Ashraf S.; Wang Q.; Boutilier J.; Wood M. J. Functional Rescue of Dystrophin-deficient mdx Mice by a Chimeric Peptide-PMO. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 1822–1829. 10.1038/mt.2010.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Egholm M.; Buchardt O.; Christensen L.; Behrens C.; Freier S. M.; Driver D. A.; Berg R. H.; Kim S. K.; Norden B.; Nielsen P. E. PNA hybridizes to complementary oligonucleotides obeying the Watson-Crick hydrogen-bonding rules. Nature 1993, 365, 566–568. 10.1038/365566a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nielsen P.; Egholm M.; Berg R.; Buchardt O. Sequence-selective recognition of DNA by strand displacement with a thymine-substituted polyamide. Science 1991, 254, 1497–1500. 10.1126/science.1962210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Abes S.; Turner J. J.; Ivanova G. D.; Owen D.; Williams D.; Arzumanov A.; Clair P.; Gait M. J.; Lebleu B. Efficient splicing correction by PNA conjugation to an R-6-Penetratin delivery peptide. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 4495–4502. 10.1093/nar/gkm418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b El-Andaloussi S.; Johansson H. J.; Lundberg P.; Langel Ü. Induction of splice correction by cell-penetrating peptide nucleic acids. J. Gene Med. 2006, 8, 1262–1273. 10.1002/jgm.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hassane F. S.; Ivanova G. D.; Bolewska-Pedyczak E.; Abes R.; Arzumanov A. A.; Gait M. J.; Lebleu B.; Gariépy J. A Peptide-Based Dendrimer That Enhances the Splice-Redirecting Activity of PNA Conjugates in Cells. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009, 20, 1523–1530. 10.1021/bc900075p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ivanova G. D.; Arzumanov A.; Abes R.; Yin H.; Wood M. J. A.; Lebleu B.; Gait M. J. Improved cell-penetrating peptide-PNA conjugates for splicing redirection in HeLa cells and exon skipping in mdx mouse muscle. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 6418–6428. 10.1093/nar/gkn671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Koppelhus U.; Shiraishi T.; Zachar V.; Pankratova S.; Nielsen P. E. Improved cellular activity of antisense peptide nucleic acids by conjugation to a cationic peptide-lipid (CatLip) domain. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008, 19, 1526–1534. 10.1021/bc800068h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Turner J. J.; Ivanova G. D.; Verbeure B.; Williams D.; Arzumanov A. A.; Abes S.; Lebleu B.; Gait M. J. Cell-penetrating peptide conjugates of peptide nucleic acids (PNA) as inhibitors of HIV-1 Tat-dependent trans-activation in cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 6837–6849. 10.1093/nar/gki991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soudah T.; Mogilevsky M.; Karni R.; Yavin E. CLIP6-PNA-Peptide Conjugates: Non-Endosomal Delivery of Splice Switching Oligonucleotides. Bioconjugate Chem. 2017, 28, 3036–3042. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cheng C. J.; Bahal R.; Babar I. A.; Pincus Z.; Barrera F.; Liu C.; Svoronos A.; Braddock D. T.; Glazer P. M.; Engelman D. M.; Saltzman W. M.; Slack F. J. MicroRNA silencing for cancer therapy targeted to the tumour microenvironment. Nature 2015, 518, 107–110. 10.1038/nature13905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gupta A.; Quijano E.; Liu Y.; Bahal R.; Scanlon S. E.; Song E.; Hsieh W.-C.; Braddock D. E.; Ly D. H.; Saltzman W. M.; Glazer P. M. Anti-tumor Activity of miniPEG-gamma-Modified PNAs to Inhibit MicroRNA-210 for Cancer Therapy. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2017, 9, 111–119. 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sajadimajd S.; Yazdanparast R.; Akram S. Involvement of Numb-mediated HIF-1 alpha inhibition in anti-proliferative effect of PNA-antimiR-182 in trastuzumab-sensitive and -resistant SKBR3 cells. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 5413–5426. 10.1007/s13277-015-4297-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S. M.; Sahu B.; Rapireddy S.; Bahal R.; Wheeler S. E.; Procopio E. M.; Kim J.; Joyce S. C.; Contrucci S.; Wang Y.; Chiosea S. I.; Lathrop K. L.; Watkins S.; Grandis J. R.; Armitage B. A.; Ly D. H. Antitumor Effects of EGFR Antisense Guanidine-Based Peptide Nucleic Acids in Cancer Models. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 345–352. 10.1021/cb3003946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorzi A.; Deyle K.; Heinis C. Cyclic peptide therapeutics: past, present and future. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017, 38, 24–29. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X.; Bruchez M. P.; Armitage B. A. Closing the Loop: Constraining TAT Peptide by gammaPNA Hairpin for Enhanced Cellular Delivery of Biomolecules. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018, 29, 2892–2898. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X.; Wickstrom E. Continuous solid-phase synthesis and disulfide cyclization of peptide-PNA-peptide chimeras. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 4013–4016. 10.1021/ol026676b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Z.; Martyna A.; Hard R. L.; Wang J.; Appiah-Kubi G.; Coss C.; Phelps M. A.; Rossman J. S.; Pei D. Discovery and Mechanism of Highly Efficient Cyclic Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 2601–2612. 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kolevzon N.; Hashoul D.; Naik S.; Rubinstein A.; Yavin E. Single point mutation detection in living cancer cells by far-red emitting PNA-FIT probes. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 2405–2407. 10.1039/c5cc07502e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hashoul D.; Shapira R.; Falchenko M.; Tepper O.; Paviov V.; Nissan A.; Yavin E. Red-emitting FIT-PNAs: “On site” detection of RNA biomarkers in fresh human cancer tissues. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 137, 271–278. 10.1016/j.bios.2019.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayraktar R.; Van Roosbroeck K. miR-155 in cancer drug resistance and as target for miRNA-based therapeutics. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2018, 37, 33–44. 10.1007/s10555-017-9724-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Marsigliante S.; Storelli O. F.; Mallardo C. D.; Montinaro A.; Cimmino A.; Pietro C.; Marsigliante S.; Pietro C.; Marsigliante S. miR-155 is up-regulated in primary and secondary glioblastoma and promotes tumour growth by inhibiting GABA receptors. Int J Oncol 2012, 41, 228–34. 10.3892/ijo.2012.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ling N.; Gu J.; Lei Z.; Li M.; Zhao J.; Zhang H.-T.; Li X. microRNA-155 regulates cell proliferation and invasion by targeting FOXO3a in glioma. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 30, 2111–2118. 10.3892/or.2013.2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres A. G.; Fabani M. M.; Vigorito E.; Gait M. J. MicroRNA fate upon targeting with anti-miRNA oligonucleotides as revealed by an improved Northern-blot-based method for miRNA detection. RNA 2011, 17, 933–943. 10.1261/rna.2533811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jullian M.; Hernandez A.; Maurras A.; Puget K.; Amblard M.; Martinez J.; Subra G. N-terminus FITC labeling of peptides on solid support: the truth behind the spacer. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 260–263. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.10.141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.