Abstract

Objective:

An early decline in resting blood pressure (BP) followed by an upward climb is well documented and indicative of a healthy pregnancy course. Although BP is considered both an effector of stress and a clinically meaningful measurement in pregnancy, little is known about its trajectory in association with birth outcomes compared to other stress effectors. The current prospective longitudinal study examined BP trajectory and perceived stress in association with birth outcomes (gestational age (GA) at birth and birth weight (BW) percentile corrected for GA) in pregnant adolescents, a group at risk for stress-associated poor birth outcomes.

Methods:

Healthy pregnant nulliparous adolescents (n=139) were followed from early pregnancy through birth. At three time points (13–16, 24–27 and 34–37 gestational weeks +/−1 week), the Perceived Stress Scale was collected along with 24-hour ambulatory BP (systolic and diastolic) and electronic diary reporting of posture. GA at birth and BW were abstracted from medical records.

Results:

After adjustment for posture and pre-pregnancy body mass index, hierarchical mixed model linear regression showed the expected early decline (B=−0.18, p=.023) and then increase (B=0.01, p<.001) of diastolic BP approximating a U-shape, however systolic BP displayed only an increase (B=0.01, p=.010). Additionally, the models indicated a stronger systolic and diastolic BP U-shape for early GA at birth and lower BW percentile and an inverted U-shape for late GA at birth and higher BW percentile. No effects of perceived stress were observed.

Conclusions:

These results replicate the pregnancy BP trajectory from previous studies of adults, and indicate that the degree to which the trajectory emerges in adolescence may be associated with variation in birth outcomes, with a moderate U-shape indicating the healthiest outcomes.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Ambulatory Blood Pressure, Perceived Stress, Gestational Age at Birth, Birth Weight, Hierarchical Mixed Model Linear Regression

INTRODUCTION

During pregnancy, the maternal cardiovascular system undergoes significant remodeling to support fetal circulation via the placenta. Maternal blood pressure (BP) is one important cardiovascular marker for maternal and fetal health that has been associated with optimal birth outcomes. Indeed, serious disorders of pregnancy, such as preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, are identified by BP, and several studies have reported associations between increased maternal BP and poor birth outcomes such as low birth weight (BW), small for gestational age (GA), and preterm birth. Specifically, these studies report linear change across pregnancy trimesters, with some noting that the degree of increase toward the end of pregnancy may predict poorer outcomes (1–5).

At the same time, multiple studies indicate that BP does not uniformly increase over pregnancy, rather it declines from pre-gravid values in early gestational weeks to a nadir and then increases upward in weeks preceding delivery (3, 6–13) approximating a U-shape. This pattern has been found for both systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP). But precisely when this nadir occurs has been subject to debate. Some evidence indicates 20 weeks (mid-gestation) (7, 8) while a recent study showed a very early decline from pre-gravid values, consistent with another study (9), without a steep rise until around 30 weeks (11). That is, those with the highest tertile pre-gravid DBP declined with the greatest magnitude and later in pregnancy, while those with the lowest tertile pre-gravid DBP declined least in magnitude and early in pregnancy (11).

To our knowledge just one study has examined BP trajectory in association with birth outcomes, such as GA at birth and BW. Neelon et al. (10) characterized mean arterial pressure (MAP) trajectories in pregnant women associated with low BW and preterm birth, identifying three latent classes that differed in both their initial MAP values (in the first trimester) and trajectories. Compared to a trajectory that started with relatively high MAP and had only a slight U-shape, the class showing moderate initial MAP and a pronounced U-shape had the lowest probabilities of low BW and preterm birth, with rates near or below national averages. The comparison class (described above) had the highest rates of low BW and preterm birth, rates above national averages. The third class showed a relatively low initial MAP with only slight decline and increase across the entire pregnancy, and low BW and preterm birth rates that were higher than national averages. This study indicates that a pronounced maternal BP U-shape may be optimal for birth outcomes, at least in terms of outcomes defined in a binary fashion (i.e. preterm birth, low BW).

The maternal BP early decline occurs despite profound increases in both maternal blood volume and cardiac output needed to support the increased circulatory and metabolic demands of the mother and placenta/fetus. These pressure-increasing adaptations are thought to be compensated for by a progressive drop in maternal vascular resistance brought on by a rise in vasodilatory hormones/mediators such as nitric oxide, relaxin, prostacyclin, and progesterone. Therefore, the maternal change in BP over the first 20 or so weeks gestation is thought to reflect a balance between parallel adaptations induced by rising levels of hormones/mediators coming from the rapidly developing placenta. The progressive increase in BP in the latter part of pregnancy is thought to represent another shift in the balance of pressure-increasing vs. pressure-decreasing factors. Spontaneous uterine contractions, pain/discomfort, anxiety, and a rise in vasopressive hormones/mediators such as the renin-angiotensin system tip the BP balance as delivery draws near.

BP is an effector of stress, and it has been shown that psychosocial stress modulates maternal BP (14–17). First, relative to a non-pregnant state (within subjects comparison), and a group of non-pregnant controls (between subjects comparison), 2nd trimester pregnant women show lower average diastolic BP (DBP) reactivity to stressful task performance (16). Second, higher DBP reactivity to a stressful task, without respect to trimester, has been associated with lower BW and earlier birth (17). Third, an association between higher DBP averaged over three mid to late pregnancy timepoints and lower BW was observed only for those reporting high psychosocial stress and anxiety (15). Fourth, DBP increase between the 2nd and 3rd trimesters was associated with lower BW for those reporting higher lifetime racism (14). Interestingly, these stress and birth outcome findings seem to be observed more often with DBP than SBP.

Across multiple studies, higher psychosocial stress has been associated with poorer birth outcomes, including earlier birth and lower BW (18–28), including in adolescence (22, 26). Significant findings in these studies varied across psychosocial stressors such as perceived stress (19, 23, 25), life events appraisal (20, 28), negative mood (26), anxiety (19, 22, 27, 28) and a cumulative measure (18) or latent factor (21, 24) involving a given combination of these. One study found that both perceived stress and state anxiety decreases between mid to late pregnancy were linked to full term birth (19). Although there are exceptions (28, 29), taken together, these studies indicate that maternal perceived stress is associated with both maternal BP and birth outcomes, and also suggest that linear changes in both maternal BP and perceived stress with advancing gestation have relevance for birth outcomes.

Despite evidence for BP U-shaped trajectory associations with birth outcomes (10), questions remain whether the early decline or late upward increase is most relevant and whether maternal psychosocial stress modulates those associations, as in previous work assessing linear effects alone (14, 15, 17, 19). To our knowledge, no study to date has assessed perceived stress and the magnitude of BP U-shaped trajectory in association with birth outcomes. To examine these questions, we performed secondary analysis on a subsample of 139 pregnant nulliparous adolescents. Adolescents were chosen for the study because they were a sample expected to experience high stress. Indeed, the adolescent pregnancy rate is higher in groups who have experienced stressors like poverty (30, 31), sexual abuse (32–37) and social upheaval (38, 39). We collected 24-hour ambulatory BP (ABP) across three pregnancy timepoints (early, middle, late) in addition to scores of perceived stress via the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (40) and abstracted birth outcomes from medical records. The PSS was selected to capture the array of adolescents’ stress exposures, being reflected in self-reports of uncontrollability, unpredictability and overloading.

The entire spectrum of birth outcomes was considered, as opposed to categorically defined poor birth outcomes, with a rationale grounded in accumulating evidence that the range matters, not just the extremes. For example, one recent report found an association of GA at birth with third-grade academic achievement, even when the sample was restricted to infants born in a range that traditionally was considered as one category, ‘full term’ i.e. 37–41 weeks (41). Additionally, a recent workgroup has noted that infants born between 39 and 41 weeks tend to have the healthiest outcomes related to both mortality and morbidity, even compared to those born 37–39 weeks and those born beyond 41 weeks (42).

Based on existing literature (5, 10), we tested interactions of continuous variables in a moderation analysis. First, we predicted that a U-shape trajectory (decline, incline) would be associated with healthy birth outcomes. Second, we predicted that when stress is high, the BP increase will be steeper, and birth outcomes will be worse. When stress is low, a modest U-shape will be observed and birth outcomes will be better. We remained agnostic as to whether these associations would emerge on either SBP or DBP.

Methods

Participants

Nulliparous pregnant adolescents, ages 14–20, participated in the study between June 2009 and January 2012. They were recruited through the Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) and Weill Cornell Medical College and flyers posted in the CUMC vicinity. All had a healthy pregnancy at the time of recruitment. Participants were excluded if they acknowledged smoking or use of recreational drugs, lacked fluency in English, or were multiparous. Participants also were excluded on the basis of frequent use of the following: nitrates, steroids, beta blockers, triptans, and psychiatric medications. Inclusion criteria included: nulliparous, singleton pregnancy, ages 13–21 prior to 19 weeks gestation, non-smoking, self-report of good health and current enrollment in prenatal care.

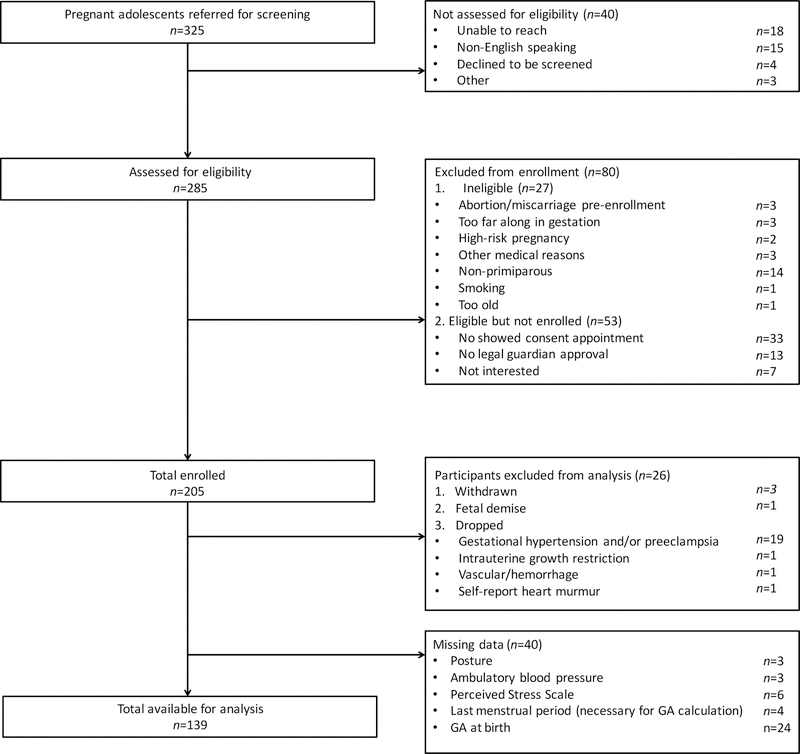

We enrolled a total of 205 participants as part of a large longitudinal study explicitly designed to observe stress response-related physiological systems during adolescent pregnancy, including BP. All participants provided written-informed consent, and all procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute/CUMC. Participants were excluded from analysis if: 1) any independent variable was missing, 2) there was fetal demise, or 3) one of the following cardiovascular-related disorders was present due to our study’s focus on BP assessment: medical record notation of intrauterine growth restriction, preeclampsia, gestational hypertension or vascular/hemorrhage, or self-report of heart murmur. The final datasets included 139 participants for assessment of GA at birth and 138 participants for assessment of BW (see Fig. 1 for the complete enrollment flow chart).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart showing complete information on participant enrollment and final number for data analyses.

We compared those included in the analyses (n=139) to those excluded due to missing data (n=40) (Fig. 1) and found that maternal age, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), PSS, BW percentile, systolic BP (SBP) and DBP did not did not differ among these two groups. Although earlier birth was found for the group with missing data, on average their GA at birth was still considered early term (37–39 gestational weeks) (42).

Study Procedure

A total of three study visits were conducted with most occurring in gestational week windows (+/−1 week) 13–16, 24–27 and 34–37, and with some occurring outside these windows due to scheduling conflicts. The earliest participant visit was 10-weeks gestation. These timepoints were selected to assess early, middle and late pregnancy, with the first visit scheduled during early second trimester for most participants (13–16 weeks). This timepoint was selected for this study to ensure full blastocyst implantation and viability as well as to maximize recruitment efforts due to possible delays in seeking prenatal care among adolescents (43).

Study sessions started generally between 10 AM and 5 PM, and ambulatory equipment was returned 24 hours later. Participants had one, randomly scheduled, urine toxicology screen to test for use of cannabinoids, amphetamines, benzodiazepines, opioids, and cotinine. One participant tested positive for cannabinoid use twice during pregnancy. In accordance with the present study’s exclusion criteria, this participant’s data were not included in analysis.

Perceived Psychological Stress

At each study visit, participants completed the PSS (40), a 14-item instrument designed to measure the degree to which participants appraise their lives as “unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloading” over the past month — i.e., high on perceived psychological stress (44). On the PSS, respondents rate the frequency of specific experiences on a 5-point scale from ‘never’ to ‘very often’ (e.g., “In the last month how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?”). The PSS has been shown to have adequate reliability, reporting a coefficient alpha of .84 to .86 (40), and has been administered previously to adolescent samples (45–47).

Blood Pressure

At each study visit, participants were outfitted with a Spacelabs Healthcare 90207 ABP Monitor (Spacelabs Healthcare, Snoqualmie, WA), an instrument with documented reliability, validity (48) and acceptability (49) in pregnant populations, with which measures of ambulatory SBP, DBP, MAP, and heart rate were collected every 30 minutes over the subsequent 24 hour period. During instrumentation, cuff size was adjusted for upper arm dimensions, and two readings were compared to an initial measurement via sphygmomanometer with the requirement that readings fall within 10 mmHg of one another.

Posture

Participants also were given an electronic diary to record posture information at each ABP measurement time point. Posture was recorded as ‘lying down’, ‘sitting’, ‘standing’, or ‘walking’, with participants providing a true/false response on each one.

Birth Outcomes

GA at birth and BW were abstracted from the medical record along with pregnancy complications (i.e. preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, intrauterine growth restriction and vascular complications) and infant sex. GA at birth was determined based on ultrasound examinations and date of last reported menstrual cycle documented in the medical record.

Data Preparation

Data were reduced based on several criteria. First, to address potential artifacts in the ABP recordings, BP values were selected for analysis according to criteria applied in previous ABP reports of non-pregnant samples (50–54) similar to other ABP pregnancy studies. The following BP ranges were accepted: 85–196 mmHg for SBP and 41–130 mmHg for DBP. If SBP or DBP observations fell outside the acceptable range, or if the difference between SBP and DBP observations at any given time point was either below 20 or above 90, those SBP and DBP observations were removed for that time point.

Second, only daytime hours were selected from the 24-hour ABP data collection based on the following: 1) there is a known circadian rhythm associated with BP that is maintained in pregnancy; 2) ABP measurements in the daytime and nighttime hours have been associated with separate health effects; 3) most studies of pregnancy BP in association with psychosocial stress and birth outcomes utilize daytime measurements including the only study of BP trajectory examining birth outcomes (10); and 4) other pregnancy ABP studies have collapsed all data into a 24-hour mean which includes daytime measurements. Therefore, daytime is a key period to study. Based on previously described wakeup and bedtime patterns of adolescents, we accepted BP samples from 10 AM to 10 PM (55).

Finally, posture data associated with an ABP reading within 5 minutes of notation were included. If participants endorsed more than one posture in an implausible combination (e.g. lying down and standing), the report was removed from data analysis. If participants endorsed more than one posture in a plausible combination (e.g. standing and walking), then the more extreme value was accepted (i.e. walking). Because BP is associated with posture, posture was included as a covariate in all models, centered at sitting.

Pre-pregnancy BMI was calculated using pre-pregnancy weight from self-report and measured height, both ascertained at the first study session. Similar to posture, BMI was included as a covariate in all models, centered at the sample mean, due to its association with BP.

Additional sample characterization.

To further characterize the sample, the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90-R) (56) was administered to assess depressive symptoms via the Depression t score, and the Social Support Questionnaire was administered to assess cumulative social support satisfaction from 27 items rated 1 ‘very dissatisfied’ to 6 ‘very satisfied’ (57). Socioeconomic status was measured through report of years education and family income level, though years of education was not anticipated to provide much variation given the young sample. Finally, we report moment-to-moment sampling of physical activity-level; that is, each time a self-report of posture was recorded, the following question also was answered: ‘At the time the alarm sounded, my level of physical activity was: 1 = not at all to 4 = very much.’

Analytic Plan

Model Estimation.

Hierarchical mixed model linear regression (HMMLR) was employed to estimate within-persons BP trajectories and between-persons differences in trajectories using a random effects maximum likelihood estimation approach via SPSS 23.0. This model is recommended for ABP data (58) and has been employed in several studies involving ambulatory measures during pregnancy, even with modest sample sizes (59–63). HMMLR is a robust technique because it utilizes every data point in variance estimations; with power to detect associations of interest being a function of both the number of individuals in the analysis (here, n=139) and the number of sampling moments (here, 3,852). This feature results in strengthened overall power to detect associations that is not accompanied by a multiple comparisons problem given that model significance relies only on one inferential test. After an evaluation of assumptions via preliminary analyses, we implemented a model building approach toward our final set of independent and a priori HMMLR models with the specifications that follow.

GA in weeks was considered the index of time and entered both as a linear term and as a quadratic, GA2, to assess the linear and non-linear changes in BP during pregnancy known from prior studies (7, 8) (Model 1). The present study does not focus on determining nuances of the BP shape, but instead, on whether the general U-shape changes in relation to several other variables of interest in our adolescent sample. Therefore, additional shapes were not considered.

BP data were centered at 10-weeks gestation as this was the first documented timepoint in the dataset, rendering the baseline or intercept of the model at 10 weeks. The parameter estimate for GA indicates the instantaneous slope for BP at 10-weeks gestation and the estimate for GA2 indicates BP non-linear changes from that instantaneous slope. Between subjects variables included PSS (Model 2), PSS and GA at birth (Model 3), PSS and BW percentile (Model 4), and their interaction terms, given previous work demonstrating associations between maternal psychosocial stress and birth outcomes (18–28).

SBP and DBP were tested separately in models and specified as the outcome (dependent) variables. This may at first glance appear confusing because, on a conceptual level, our outcomes of interest were birth outcomes (GA at birth and BW percentile). The statistical model, however, requires that the variable that was repeatedly measured be specified as the outcome variable. PSS, a time-varying covariate of interest, and GA at birth (or BW percentile) were assigned as independent variables. So, to be clear, our statistical models are estimating the trajectory for SBP and DBP change over the course of pregnancy, and the parameter estimates for PSS and GA at birth (and their interactions) are estimating the associations between these variables and the BP trajectories. Thus, the models are addressing our questions of how PSS and GA at birth associate with BP trajectories.

Finally, posture at every sampling moment and pre-pregnancy BMI were entered as covariates, and all independent variables were centered. In consideration of additional covariates, a priori, we first included time of day due to known circadian rhythms in BP, but found this variable did not improve model fit. Thus, it was dropped from further analysis. For the outcome (BP), as long as some data were present, missing readings were estimated using maximum likelihood. However, participants with missing data on other study variables were excluded from analyses.

Model 1: Time Only.

In the first step of the model-building approach, we examined the shape of the overall BP trajectories by including GA and GA2 during pregnancy to model BP over time (n=169). GA and GA2 are the linear and quadratic estimates, respectively, that define BP change as a function of GA during pregnancy.

Model 2: Time and PSS.

Building on Model 1, PSS and its interaction terms with GA and GA2 were added to test associations among perceived stress and BP trajectories over the course of pregnancy (n=163).

Model 3: Time and PSS and GA at Birth.

Building on Model 2, associations among perceived stress, infant GA at birth and BP trajectories over the course of pregnancy (n = 139) were modeled as follows:

where BP refers to either SBP or DBP at moment k within person j, GA and GA2 are the linear and quadratic estimates, respectively, that define BP change as a function of GA during pregnancy, PSS is the estimate for the association between perceived stress and BP trajectory, and likewise, GA at birth is the estimate for the association between GA at birth and BP trajectory.

GA at birth was entered as a continuous variable. For interpretation of GA at birth results, we turned to recent work that divides GA at birth into the following groups: late preterm (34 weeks, 0 days – 36 weeks, 6 days), early term (37 weeks, 0 days – 38 weeks, 6 days), full term (39 weeks, 0 days – 40 weeks, 6 days), late term (41 weeks, 0 days – 41 weeks, 6 days) and post term ( ≥ 42 weeks, 0 days) (42). Within this framework, it is thought that delivery at full term is most strongly associated with optimal infant health outcomes.

Model 4: Time and PSS and BW Percentile.

Building on Model 2, associations among perceived stress, infant BW percentile and BP trajectories over the course of pregnancy (n = 138) were assessed. This model was constructed similarly to Model 3 with BW percentile substituted for GA at birth. BW percentile was based on BW population norms by GA at birth separately for male and female infants (64). With this BW percentile variable, both GA at birth and infant sex were taken into account.

Results

Descriptives

As shown in Table 1, on average participants delivered infants at full term (42) and of healthy BW. Mean SBP fell into a normotensive range, and mean DBP fell into a low prehypertensive range (65–67). Perceived stress was elevated relative to healthy pregnant adult samples from prior studies (68, 69) and was similar to other adolescent cohorts (45–47), including pregnant adolescents (47). Also, PSS showed adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha Visit 1 = .66; Visit 2 = .73; Visit 3 = .58); these results are lower than some previous work (40), but closer to those of prior studies with adolescent samples (45–47). Additional descriptives characterizing the sample can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptives.

N=139; observations=3852

| Overall | Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Mean | Std Dev | Min | Max | N (%) | Mean | Std Dev | Min | Max | N (%) | Mean | Std Dev | Min | Max | N (%) | Mean | Std Dev | Min | Max | |

| Maternal Age (years) | 139 | 17.84 | 1.15 | 14.00 | 20.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Maternal Pre-Pregnancy BMI | 139 | 27.37 | 6.63 | 17.62 | 54.33 | |||||||||||||||

| Gestational Age at Birth (weeks) | 139 | 39.28 | 1.81 | 26.57 | 41.57 | |||||||||||||||

| Birth Weight (grams) | 138 | 3237.67 | 480.36 | 947.00 | 4525.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Birth Weight percentile | 138 | 39.62 | 24.96 | 1.00 | 98.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Years Education | 139 | 10.96 | 1.34 | 7.00 | 12.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Social Support Questionnaire | 134 | 143.58 | 25.02 | 30.00 | 162.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Systolic BP (Daytime) (mmHg) | 139 | 118.75 | 7.09 | 98.87 | 138.43 | 101 | 117.35 | 7.20 | 98.00 | 138.75 | 100 | 118.85 | 7.92 | 100.50 | 136.11 | 94 | 122.43 | 9.98 | 92.40 | 150.94 |

| Diastolic BP (Daytime) (mmHg) | 139 | 85.99 | 5.54 | 72.73 | 101.00 | 101 | 84.89 | 5.96 | 70.67 | 103.00 | 100 | 85.61 | 6.05 | 68.00 | 98.13 | 94 | 89.05 | 7.71 | 67.60 | 112.00 |

| Perceived Stress Scale | 139 | 27.00 | 5.49 | 13.14 | 41.00 | 101 | 27.49 | 6.18 | 12.00 | 43.00 | 100 | 25.68 | 7.09 | 5.00 | 48.00 | 94 | 26.54 | 5.37 | 12.92 | 41.00 |

| Depression (SCL-90 t score) | 122 | 54.13 | 8.60 | 34.00 | 77.00 | 81 | 55.51 | 9.32 | 35.00 | 81.00 | 84 | 53.04 | 9.31 | 29.00 | 81.00 | 80 | 53.56 | 9.36 | 34.00 | 81.00 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 139 | 23.02 | 5.53 | 12.00 | 38.00 | 101 | 14.28 | 1.92 | 10.00 | 20.00 | 100 | 25.19 | 1.78 | 22.00 | 31.00 | 94 | 35.00 | 1.63 | 31.00 | 39.00 |

| Posture (self-report) | 139 | 2.04 | 0.31 | 1.14 | 3.13 | 101 | 2.10 | 0.40 | 1.20 | 3.57 | 100 | 2.05 | 0.37 | 1.17 | 2.83 | 94 | 2.03 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 3.50 |

| Physcial Activity (self-report) | 139 | 1.62 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 101 | 1.63 | 0.52 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 100 | 1.65 | 0.57 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 94 | 1.62 | 0.71 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Weight Gain | 135 | 14.79 | 11.88 | −18.50 | 48.00 | 101 | 3.18 | 8.51 | −37.00 | 25.00 | 96 | 16.26 | 10.59 | −21.00 | 38.00 | 89 | 28.13 | 14.01 | −26.00 | 58.00 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 126 (91) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 13 (9) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Infant Sex | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 82 (59) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Female | 57 (41) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Income | ||||||||||||||||||||

| $0–$15,000 | 47 (34) | |||||||||||||||||||

| $16,000–$25,000 | 46 (33) | |||||||||||||||||||

| $26,000–$50,000 | 25 (18) | |||||||||||||||||||

| $51,000–$100,000 | 2 (1) | |||||||||||||||||||

| $101,000–$250,000 | 0 (0) | |||||||||||||||||||

| > $250,000 | 0 (0) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Unknown | 19 (14) | |||||||||||||||||||

| BP Counts by Posture Self-Report | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Lying down | 1173 (30) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Standing | 372 (10) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Walking | 490 (13) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sitting | 1817 (47) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 3852 (100) | |||||||||||||||||||

Std Dev = Standard Deviation; BMI = Body Mass Index; BP = Blood Pressure

Min = Minimum; Max = Maximum

PSS = Perceived Stress Scale

SCL-90 = Symptom Checklist-90

Posture

Relative to sitting, SBP decreased by 4.50 mmHg when lying down, increased by 3.70 mmHg when standing and increased by 4.50 mmHg when walking. Including posture in the model accounted for about 9.3% of the within person variance in SBP. For DBP, there was a 4.3 mmHg decrease when lying down, a 3.9 mmHg increase when standing and a 3.6 mmHg increase when walking. Posture accounted for 10.6% of the within person variance in DBP. Pre-pregnancy BMI had a significant positive association with SBP (B = .26, p < .001), but not with DBP. Taken together, these results were expected and provide a quality control check of the data. The results support inclusion of posture and BMI in these analyses.

Model 1: Time Only.

We observed that SBP had a non-significant instantaneous slope at 10-weeks gestation (B = −.03, p = .774), indicating that SBP did not significantly decrease during the early part of pregnancy. However, the quadratic change in BP was positive and significant suggesting accelerating increases in BP with advancing gestation (B = .01, p = .010). For DBP, there was a significant instantaneous slope at 10-weeks gestation (B = −.18, p = .023) and a significant positive quadratic change (B = .01, p < .001), indicating a U-shaped trajectory over pregnancy.

Model 2: Time and PSS.

The addition of PSS and its interactions to Model 1 revealed a marginally significant result of GA x PSS (B = .03, p =.072) on SBP, suggesting that increased perceived stress was associated with increased SBP in the early part of pregnancy. That is, increased perceived stress tended to work against the expected decrease in SBP during the early phase of pregnancy. All other PSS associations were not significant.

Model 3: Time and PSS and GA at Birth.

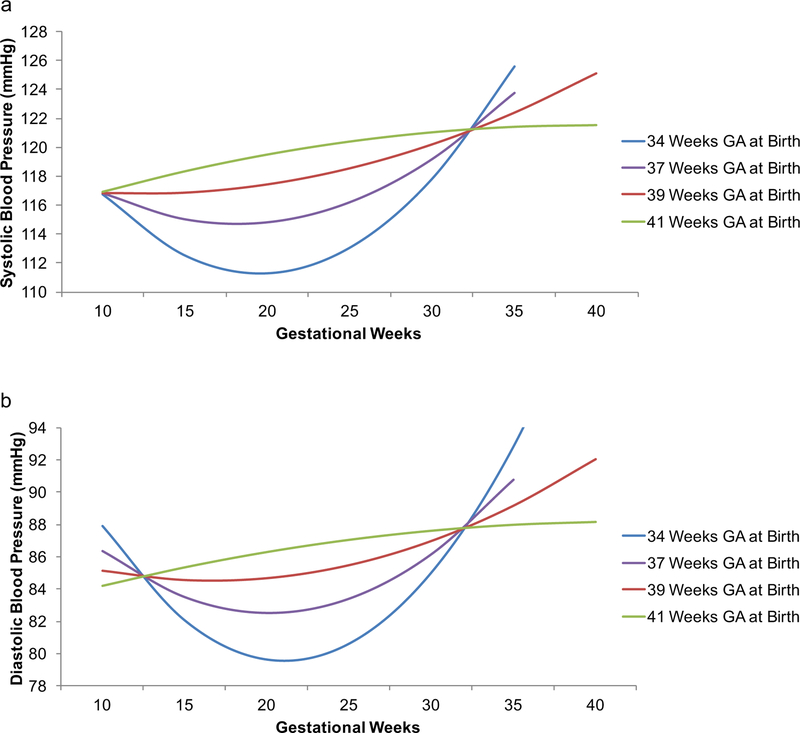

The association between GA at birth and SBP trajectory was significant for GA (B = .21, p = .047) and GA2 (B = −.01, p = .013; Table 2). The same significant associations were observed for DBP: GA (B = .25, p = .003) and GA2 (B = −.01, p = .001; Table 3). Visualized in Fig. 2, these associations show that relative to mean GA at birth (39 weeks), with earlier GA at birth the BP U-shape was more pronounced and with late term birth, it was inverted. There were no significant PSS findings.

Table 2.

Systolic Blood Pressure Trajectory over Pregnancy Hierarchical mixed model linear regression

| 1. Time Only (n=169) | 2. Time and PSS (n=163) | 3. Time and PSS and GA at Birth (n=139) | 4. Time and PSS and Birth Weight Percentile (n=138) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||||||||||||||

| Parameter | Estimate (β) | Sth Error | p- Value | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Estimate (β) | Sth Error | p- Value | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Estimate (β) | Sth Error | p- Value | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Estimate (β) | Sth Error | p- Value | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

| Intercept | 117.76 | 0.73 | < .001 | 116.33 | 119.19 | 117.69 | 0.75 | < .001 | 116.22 | 119.16 | 117.24 | 0.83 | < .001 | 115.60 | 118.88 | 117.28 | 0.82 | < .001 | 115.67 | 118.89 |

| Posture – lying down | −4.62 | 0.34 | < .001 | −5.29 | −3.95 | −4.67 | 0.35 | < .001 | −5.35 | −3.98 | −4.64 | 0.37 | < .001 | −5.38 | −3.91 | −4.70 | 0.38 | < .001 | −5.44 | −3.96 |

| Posture – standing | 3.33 | 0.49 | < .001 | 2.36 | 4.30 | 3.31 | 0.50 | < .001 | 2.32 | 4.29 | 3.40 | 0.54 | < .001 | 2.33 | 4.46 | 3.29 | 0.55 | < .001 | 2.20 | 4.37 |

| Posture – walking | 4.66 | 0.45 | < .001 | 3.78 | 5.53 | 4.60 | 0.45 | < .001 | 3.71 | 5.48 | 5.11 | 0.49 | < .001 | 4.16 | 6.06 | 5.06 | 0.49 | < .001 | 4.10 | 6.02 |

| Posture – sitting (reference category) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||

| Pre-pregnancy body mass index | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.002 | 0.09 | 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.004 | 0.08 | 0.41 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.003 | 0.09 | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.003 | 0.10 | 0.45 |

| GA | −0.03 | 0.10 | 0.774 | −0.22 | 0.16 | −0.01 | 0.10 | 0.953 | −0.20 | 0.19 | −0.05 | 0.11 | 0.667 | −0.26 | 0.17 | −0.05 | 0.11 | 0.630 | −0.26 | 0.16 |

| GA2 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.010 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.018 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.006 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.007 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| PSS | −0.13 | 0.11 | 0.216 | −0.34 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.12 | 0.387 | −0.34 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.12 | 0.938 | −0.25 | 0.23 | |||||

| GA x PSS | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.072 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.193 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.763 | −0.03 | 0.04 | |||||

| GA2 x PSS | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.151 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.302 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.909 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||

| GA at birth | 0.07 | 0.78 | 0.929 | −1.47 | 1.61 | |||||||||||||||

| GA x GA at birth | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.047 | 0.00 | 0.41 | |||||||||||||||

| GA2 x GA at birth | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.013 | −0.02 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

| GA at birth x PSS | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.251 | −0.10 | 0.39 | |||||||||||||||

| GA x GA at birth x PSS | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.745 | −0.04 | 0.03 | |||||||||||||||

| GA2 x GA at birth x PSS | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.934 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Birth weight percentile | −0.11 | 0.03 | 0.001 | −0.18 | −0.04 | |||||||||||||||

| GA Birth weight percentile | 0.02 | 0.00 | < .001 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |||||||||||||||

| GA2 x Birth weight percentile | 0.00 | 0.00 | < .001 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Birth weight percentile x PSS | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.179 | −0.02 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

| GA x Birth weight percentile x PSS | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.244 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

| GA2 x Birth weight percentile x PSS | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.279 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

Bold indicates significant effects.

All variables were centered.

Sample size increased due to removal of birth outcomes from the model.

CI= confidence interval; GA = gestational age in weeks

PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; Std Error = standard error of the mean

Table 3. Diastolic Blood Pressure Trajectory over Pregnancy.

Hierarchical mixed model linear regression

| 1. Time Only (n=169) | 2. Time and PSS (n=163) | 3. Time and PSS and GA at Birth (n=139) | 4. Time and PSS and Birth Weight Percentile (n=138) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||||||||||||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||||||||||

| Parameter | Estimate (β) | Std Error | p- Value | Bound | Bound | Estimate (β) | Std Error | p- Value | Bound | Bound | Estimate (β) | Std Error | p- Value | Bound | Bound | Estimate (β) | Std Error | p- Value | Bound | Bound |

| Intercept | 85.75 | 0.58 | < .001 | 84.61 | 86.90 | 85.66 | 0.60 | < .001 | 84.49 | 86.83 | 85.55 | 0.68 | < .001 | 84.22 | 86.87 | 85.52 | 0.67 | < .001 | 84.20 | 86.83 |

| Posture – lying down | −4.29 | 0.29 | < .001 | −4.86 | −3.72 | −4.31 | 0.29 | < .001 | −4.89 | −3.74 | −4.31 | 0.32 | < .001 | −4.93 | −3.68 | −4.37 | 0.32 | < .001 | −5.01 | −3.74 |

| Posture – standing | 3.82 | 0.42 | < .001 | 2.99 | 4.64 | 3.83 | 0.43 | < .001 | 3.00 | 4.66 | 3.93 | 0.46 | < .001 | 3.02 | 4.84 | 3.81 | 0.47 | < .001 | 2.88 | 4.73 |

| Posture – walking | 3.81 | 0.38 | < .001 | 3.06 | 4.55 | 3.85 | 0.39 | < .001 | 3.09 | 4.60 | 3.99 | 0.41 | < .001 | 3.18 | 4.80 | 3.99 | 0.42 | < .001 | 3.17 | 4.81 |

| Posture – sitting (reference category) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||

| Pre-pregnancy body mass index | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.755 | −0.10 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.766 | −0.11 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.735 | −0.11 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.679 | −0.11 | 0.17 |

| GA | −0.18 | 0.08 | 0.023 | −0.33 | −0.02 | −0.15 | 0.08 | 0.067 | −0.31 | 0.01 | −0.19 | 0.09 | 0.039 | −0.36 | −0.01 | −0.17 | 0.09 | 0.053 | −0.35 | 0.00 |

| GA2 | 0.01 | 0.00 | < .001 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | < .001 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | < .001 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | < .001 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| PSS | −0.09 | 0.09 | 0.316 | −0.25 | 0.08 | −0.09 | 0.10 | 0.345 | −0.28 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.12 | 0.938 | −0.25 | 0.23 | |||||

| GA x PSS | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.238 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.578 | −0.02 | 0.04 | |||||

| GA2 x PSS | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.255 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.468 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.887 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||

| GA at birth | −0.48 | 0.63 | 0.447 | −1.73 | 0.76 | |||||||||||||||

| GA x GA at birth | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.003 | 0.08 | 0.41 | |||||||||||||||

| GA2 x GA at birth | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.001 | −0.02 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

| GA at birth x PSS | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.151 | −0.05 | 0.35 | |||||||||||||||

| GA x GA at birth x PSS | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.677 | −0.03 | 0.02 | |||||||||||||||

| GA2 x GA at birth x PSS | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.992 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Birth weight percentile | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.074 | −0.11 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

| GA x Birth weight percentile | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.013 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |||||||||||||||

| GA2 x Birth weight percentile | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.011 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Birth weight percentile x PSS | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.902 | −0.01 | 0.01 | |||||||||||||||

| GA x Birth weight percentile x PSS | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.937 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

| GA2 x Birth weight percentile x PSS | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.645 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

Bold indicates significant effects.

All variables were centered.

Sample size increased due to removal of birth outcomes from the model.

CI= confidence interval; GA = gestational age in weeks

PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; Std Error = standard error of the mean

Fig. 2. Ambulatory blood pressure over pregnancy as a function of gestational age and gestational age at birth.

Statistically adjusting for perceived stress, earlier gestational age at birth was associated with a more prominent U-shaped systolic (a) and diastolic (b) blood pressure trajectory over pregnancy. Gestational weeks were modeled continuously. Here results of the model are shown, with 34, 37, 39, and 41 weeks gestational age at birth selected based on criteria from Spong (2013) (42). 39 weeks gestational age birth was the mean of the sample. These results indicate that a subtle U-shape may be predictive of full term infants.

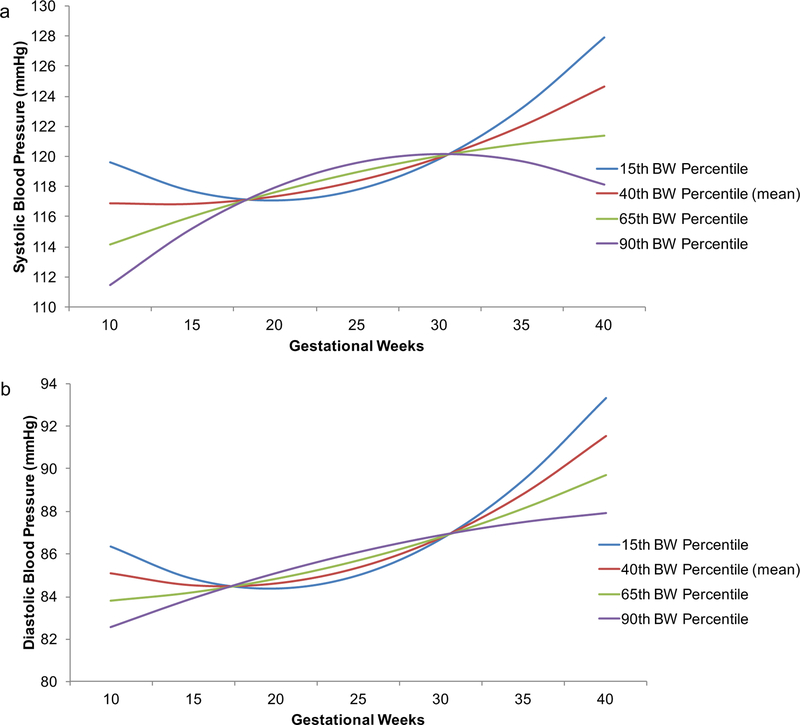

Model 4: Time and PSS and BW Percentile.

The results from both SBP and DBP models were similar to those from Model 3 with the following differences: 1) BW percentile had a negative association with SBP at 10-weeks gestation (i.e., at the intercept; B = −.11, p = .001), indicating that higher BW was associated with decreased average SBP (Table 2), and 2) the slope of DBP GA fell to marginal significance (B = −.17, p = .053; Table 3). As visualized in Fig. 3, relative to mean BW percentile (40th), lower BW percentiles were associated with more pronounced U-shaped trajectories and higher BW percentiles with linear (DBP) or inverted U-shaped (SBP) trajectories. There were no significant PSS findings.

Fig. 3. Ambulatory blood pressure over pregnancy as a function of gestational age and birth weight percentile.

Statistically adjusting for perceived stress, lower birth weight percentile was associated with a more prominent U-shaped systolic (a) and diastolic (b) blood pressure trajectory over pregnancy. Gestational weeks were modeled continuously, and birth weight percentile was selected as an index with the effects of gestational age at birth and infant sex removed (64). Here results of the model are shown. 40th percentile was the sample mean and other percentiles shown are −1 SD, +1 SD and +2 SDs relative to the mean. These results indicate that a subtle U-shape may be predictive of healthy birth weight.

Sensitivity analyses.

Other covariates such as weight gain over pregnancy may influence BP trajectories (8). Additionally, because socioeconomic status and physical activity were associated with BP in previous work with adults, we wondered to what extent these may play a role in BP patterns in our adolescent sample. In initial analyses, we entered each covariate separately into a model with just GA and GA2 (i.e., Model 1 described above) to determine if these covariates were associated with BP trajectories. Socioeconomic status was not associated with BP trajectories (note that there is little variability in socioeconomic status in Table 1) but both weight gain (SBP: B = .09, p = .015 and DBP: B = .10, p < .001) and physical activity were (SBP: with Level 4 ‘very much’ as reference, Level 1 ‘not at all’ B = −1.85, p = .004, Levels 2 and 3 ns and DBP: Level 1 B = −1.88, p = .001, Level 2 B = −1.18, p = .030, Level 3 B = −1.04, p = .065). After adding weight gain and activity level to our full models (i.e. Models 3 and 4 described above), the primary results were unchanged, with the exception that the linear term of time (GA) x GA at birth interaction on SBP became marginally significant (p=.062). Our a priori inclusion of the posture covariate––indicating 77 percent of samples occurred during lying down or sitting (Table 1)–– already may have accounted for much of the variance in self-report of physical activity leve

Discussion

The present study characterized BP trajectories in healthy pregnant nulliparous adolescents in association with birth outcomes (GA at birth and BW) and perceived stress to ask whether maternal BP early decline and/or late incline in association with stress was related to birth outcomes. It employed ABP and electronic diary methodology over three time points (early, middle, late pregnancy) and HMMLR, a powerful statistical model that utilizes every observation, to estimate both within and between subject variance without multiple testing. Statistically adjusting for posture and pre-pregnancy-BMI, an overall U-shaped BP curve was observed –– specifically, DBP showed significant decline and incline over pregnancy, whereas SBP showed only significant incline.

For both SBP and DBP, decline and incline of the U-shaped curve were associated with GA at birth and BW. Visualization of the trajectories showed a slight BP U-shape for full term infants (39 weeks), which was the sample mean. With decreasing GA at birth, including early term (37 weeks) and late preterm (34 weeks) pregnancies, the U-shape was more pronounced. However, with increasing GA at birth (i.e. in late term at 41 weeks), the U-shape inverted. For BW percentile, an index that controlled for both GA at birth and infant sex, results were similar –– for those infants whose BW decreased relative to the sample mean (40th percentile), the U-shaped pattern was more pronounced. However, for those infants whose BW exceeded the sample mean, the curve inverted.

Maternal BP early decline has been observed previously (3, 6, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16) as well as BP associations with birth outcomes such as preterm birth, low BW and small for GA (1–5, 10). In contrast to previous work that found a lack of mid-gestation nadir in association with poor health outcomes (7, 10), we observed a more pronounced U-shape trajectory in association with earlier GA at birth and lower BW, with both decline and incline parameters being significant for SBP and DBP in all models. We also observed an inverted U-shape for those pregnancies that resulted in late term birth and high BW (i.e. 90th percentile).

These differences in study results may reflect methodological variation. Here, we: 1) examined adolescent SBP and DBP via ABP technology, 2) excluded on poor health outcomes such as preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, 3) performed an analysis that afforded estimating both decline and incline parameters and 4) entered our variables of interest in a continuous manner examining the entire range of birth outcomes. In contrast, Neelon et al. (10) examined adult normotensive MAP via readings acquired at doctors’ visits and performed growth mixture modeling that entered birth outcomes categorically (i.e. preterm birth or not, low BW or not). Hermida et al. (7) studied adult ABP, but included those with pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia and gestational hypertension. Taken together, the results suggest that BP trajectories may be useful for predicting, and potentially understanding, poor birth outcomes, yet work remains to be done to identify the most valid methodological approaches.

Discussion of the prehypertensive range, a category relatively understudied, has emerged in the literature defined as SBP of 120–139 mmHg and DBP of 80–89 mmHg, and we note here that our participants on average were categorized in the prehypertensive DBP range (65–67). Interestingly, a recent study reported that a steeper DBP slope in the prehypertensive range in late pregnancy associated with small for GA (5), a finding that is consistent with the BW results here. Prehypertensive and hypertensive women were not distinguished from others in Neelon et al. (10). It could be that the prehypertensive range provides additional insight into the prediction of healthy birth outcomes beyond the binomial distinction between hypertensive and non-hypertensive. (New American College of Cardiology guidelines released in November 2017 have split prehypertension into two categories: Elevated Blood Pressure (120–129 / <80 mmHg) and Hypertension Stage 1 (130–139 mmHg SBP or 80–89 mmHg DBP) (70). Also, adolescent guidelines for hypertension now match those of adults (71).)

This is the first study, to our knowledge, that assessed associations between perceived stress and prenatal BP trajectories in relation to birth outcomes. Stress effects on prenatal BP have been documented including acute laboratory stress (16, 17), chronic long term psychosocial exposure associated with lifetime racism (14) and cumulative psychosocial stress capturing socioenvironmental resources, perceived stress and anxiety (15). We selected the PSS to measure perceived stress given its use in previous investigations of maternal pregnancy BP (15), birth outcomes (19) and adolescent women (45–47). Despite evidence suggesting elevated levels of perceived stress in the current sample, we did not find that individual differences in stress were related to differences in BP mean or trajectory.

Similar to the present study, an investigation focusing on maternal race, pre-pregnancy BMI, weight gain and PSS in association with BP trajectory over pregnancy determined a final model that included significant linear and quadratic parameters estimating BP trajectory but no effects of PSS (8). Taken together, perceived stress as measured by the PSS may not be the form of psychosocial stress influencing maternal BP trajectory in pregnancy. Nonetheless, given that BP is an effector of stress and that both BP and stress have been found to affect birth outcomes, the implications of stress in association with maternal pregnancy BP trajectory should be examined further.

The mechanism underlying associations between maternal BP trajectories and birth outcomes is largely unknown, but it is has been established that maternal cardiovascular health indices and birth outcomes are connected. First, pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia present with maternal hypertension and often with earlier birth and lower birthweight, and second, multiple maternal cardiac aberrations have been found in normotensive women with pregnancies complicated by fetal growth restriction (72). Maternal systemic cardiovascular indices (including BP) and eventual birth outcomes may be linked through maternal immune system reactivity of pregnancy, which is implicated in processes such as uteroplacental circulatory structuring and placental feedback to the maternal blood. In light of the robust documentation of the maternal pregnancy BP U-shape to date (3, 6–13), it is intriguing to consider whether the U-shape’s distinct components (early decline, late incline) might individually signal information about uteroplacental health. Specifically, BP increases after mid-gestation at least in part may be linked to maternal immune activation resulting from placental debris deposit (73, 74). The early BP decline is thought to be a function of reduced lower vascular resistance, which occurs both systemically and locally at the level of the uterus and placenta, though how this connects to later sharp BP increases and birth outcomes must be investigated further.

The present study includes both methodological strengths and limitations. One strength is its prospective longitudinal design utilizing ABP monitors, enabling the collection of multiple BP recordings in participants’ daily lives in early, middle and late pregnancy. Second, electronic diary methodology was employed to collect posture information to remove the known profound associations of posture with BP. Third, HMMLR was selected to assess pregnancy BP trajectory, not only linear change alone, that allowed the intercept and slope to vary for each participant with the specification of random effects and estimated missing data in the outcome, which in turn enabled the inclusion of more participants; it also allowed for the assessment of both linear and quadratic changes in a single model. Finally, recognizing that GA at birth and BW are important pregnancy outcomes predictive of offspring health and achievement across the lifespan, our study included these as continuous variables.

Our study was limited to healthy pregnant adolescents living in an urban environment so that generalizability of these findings must be determined. We note that given the lower than expected internal consistency found our perceived stress measurement, our stress results should be viewed with caution. A second limitation concerns the first measurement timepoint at 13–16 weeks gestation and a total of three study visits overall. A recent study, reliant on pre-gravid BP values, has indicated that maternal BP decline begins very early in pregnancy with the magnitude and the timing of the decline associated with pre-gravid values (11). In the current study, it could be that those pregnancies resulting in earlier GA at birth occurred in women with higher pre-gravid BP. Nonetheless, measurement at 13–16 gestation, though early in second trimester, was early enough to capture declining BP (though likely at its end) as upward incline begins around 20–30 weeks gestation. Future research should explore the nature of pre-gravid baseline and early pregnancy within BP trajectory effects —as well as alternative trajectory shapes estimated with the addition of more study timepoints—on birth outcomes though this will be hard to accomplish in an adolescent sample with largely unplanned pregnancies.

Our study showed that BP trajectory became less strongly pronounced as birth moved from late preterm, to early term to full term and that it inverted in late term. As indicated by Spong et al. (42), these GA at birth categories are distinct beyond what was traditionally labeled full term (> 37 weeks) because they have consequences for infant health. In line with this conceptualization, our findings here demonstrate that a moderate (or ‘just right’ Goldilocks) inflection shape may be associated with the healthiest pregnancy outcomes. Future studies might indicate, as the current one does, that a strong dip followed by a sharp incline is associated with early GA at birth or low BW. The dip (or lack thereof) from early to mid-pregnancy, along with monitoring of increases thereafter, might be a window of time when intervention one day could be applied.

Acknowledgements:

Thanks to Dr. Elizabeth Werner, Sophie Foss, Laura Kurzius, and Willa Marquis who led data collection in this study, to Melissa Huang for assistance with assembling the STROBE diagram, and Dr. Carolyn Salafia for providing helpful input on the manuscript.

Source of Funding This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01 MH093677–03 to C.M. and K99 HD07966802 to J.S.].

Abbreviations:

- ABP

ambulatory blood pressure

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BMI

body mass index

- BP

blood pressure

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- GA

gestational age

- HMMLR

hierarchical mixed model linear regression

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- PSS

perceived stress scale

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- SD

standard deviation

- SE

standard error

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bakker R, Steegers EA, Hofman A, Jaddoe VW. Blood pressure in different gestational trimesters, fetal growth, and the risk of adverse birth outcomes: the generation R study. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:797–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Churchill D, Perry IJ, Beevers DG. Ambulatory blood pressure in pregnancy and fetal growth. Lancet 1997;349:7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macdonald-Wallis C, Tilling K, Fraser A, Nelson SM, Lawlor DA. Associations of blood pressure change in pregnancy with fetal growth and gestational age at delivery: findings from a prospective cohort. Hypertension 2014;64:36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steer PJ, Little MP, Kold-Jensen T, Chapple J, Elliott P. Maternal blood pressure in pregnancy, birth weight, and perinatal mortality in first births: prospective study. BMJ 2004;329:1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wikstrom AK, Gunnarsdottir J, Nelander M, Simic M, Stephansson O, Cnattingius S. Prehypertension in Pregnancy and Risks of Small for Gestational Age Infant and Stillbirth. Hypertension 2016;67:640–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grindheim G, Estensen ME, Langesaeter E. Changes in blood pressure during healthy pregnancy: a longitudinal cohort study. Journal of Hypertension 2012;30:342–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Iglesias M. Predictable blood pressure variability in healthy and complicated pregnancies. Hypertension 2001;38:736–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magriples U, Boynton MH, Kershaw TS, Duffany KO, Rising SS, Ickovics JR. Blood pressure changes during pregnancy: impact of race, body mass index, and weight gain. Am J Perinatol 2013;30:415–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahendru AA, Everett TR, Wilkinson IB, Lees CC, McEniery CM. Maternal cardiovascular changes from pre-pregnancy to very early pregnancy. J Hypertens 2012;30:2168–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neelon B, Swamy GK, Burgette LF, Miranda ML. A Bayesian growth mixture model to examine maternal hypertension and birth outcomes. Stat Med 2011;30:2721–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen MX, Tan HZ, Zhou SJ, Smith GN, Walker MC, Wen SW. Trajectory of blood pressure change during pregnancy and the role of pre-gravid blood pressure: a functional data analysis approach. Sci Rep-Uk 2017;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson ML, Williams MA, Miller RS. Modelling the association of blood pressure during pregnancy with gestational age and body mass index. Paediatr Perinat Ep 2009;23:254–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thornburg KL, Jacobson S-L, Giraud GD, Morton MJ. Hemodynamic changes in pregnancy. Seminars in Perinatology 2000;24:11–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hilmert CJ, Dominguez TP, Schetter CD, Srinivas SK, Glynn LM, Hobel CJ, Sandman CA. Lifetime racism and blood pressure changes during pregnancy: Implications for fetal growth. Health Psychol 2014;33:43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hilmert CJ, Schetter CD, Dominguez TP, Abdou C, Hobel CJ, Glynn L, Sandman C. Stress and Blood Pressure During Pregnancy: Racial Differences and Associations With Birthweight. Psychosomatic medicine 2008;70:57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews KA, Rodin J. Pregnancy Alters Blood Pressure Responses to Psychological and Physical Challenge. Psychophysiology 1992;29:232–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCubbin Lawson, Cox Sherman, Norton Read. Prenatal maternal blood pressure response to stress predicts birth weight and gestational age: A preliminary study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996;175:706–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Das A, Elder N, Swain M, Norman G, Ramsey R, Cotroneo P, Collins BA, Johnson F, Jones P, Meier A, Northern A, Meis PJ, MuellerHeubach E, Frye A, Mowad AH, Miodovnik M, Siddiqi TA, Bain R, Thom E, Leuchtenburg L, Fischer M, Paul RH, Kovacs B, Rabello Y, Caritis S, Harger JH, Cotroneo M, Stallings C, McNellis D, Yaffee S, Catz C, Klebanoff M, Iams JD, Landon MB, Thurnau GR, Carey JC, VanDorsten JP, Neuman RB, LeBoeuf F, Sibai B, Mercer B, Fricke J, Bottoms SF, Dombrowski MP. The preterm prediction study: Maternal stress is associated with spontaneous preterm birth at less than thirty-five weeks’ gestation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1996;175:1286–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glynn LM, Schetter CD, Hobel CJ, Sandman CA. Pattern of perceived stress and anxiety in pregnancy predicts preterm birth. Health Psychol 2008;27:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedegaard M, Henriksen TB, Secher NJ, Hatch MC, Sabroe S. Do stressful life events affect duration of gestation and risk of preterm delivery? Epidemiology 1996;7:339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lobel M, Dunkelschetter C, Scrimshaw SCM. Prenatal Maternal Stress and Prematurity - a Prospective-Study of Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Women. Health Psychol 1992;11:32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCool WF, Dorn LD, Susman EJ. The relation of cortisol reactivity and anxiety to perinatal outcome in primiparous adolescents. Research in Nursing and Health 1994;17:411–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Misra DP, O’Campo P, Strobino D. Testing a sociomedical model for preterm delivery. Paediatr Perinat Ep 2001;15:110–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rini CK, Dunkel-Schetter C, Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA. Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: the role of personal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Health Psychol 1999;18:333–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sable MR, Wilkinson DS. Impact of perceived stress, major life events and pregnancy attitudes on low birth weight. Family Planning Perspectives 2000;32:288–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spicer J, Werner E, Zhao Y, Choi CW, Lopez-Pintado S, Feng T, Altemus M, Gyamfi C, Monk C. Ambulatory assessments of psychological and peripheral stress-markers predict birth outcomes in teen pregnancy. J Psychosom Res 2013;75:305–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tegethoff M, Greene N, Olsen J, Meyer AH, Meinlschmidt G. Maternal Psychosocial Adversity During Pregnancy Is Associated With Length of Gestation and Offspring Size at Birth: Evidence From a Population-Based Cohort Study. Psychosomatic Medicine 2010;72:419–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA, Porto M, Dunkelschetter C, Garite TJ. The Association between Prenatal Stress and Infant Birth-Weight and Gestational-Age at Birth - a Prospective Investigation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1993;169:858–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smew AI, Hedman AM, Chiesa F, Ullemar V, Andolf E, Pershagen G, Almqvist C. Limited association between markers of stress during pregnancy and fetal growth in ‘Born into Life’, a new prospective birth cohort. Acta Paediatr 2018;107:1003–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darroch JE. Adolescent pregnancy trends and demographics. Curr Womens Health Rep 2001;1:102–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felice ME, Feinstein RA, Fisher MM, Kaplan DW, Olmedo LF, Rome ES, Staggers BC. Adolescent pregnancy--current trends and issues: 1998 American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence, 1998–1999. Pediatrics 1999;103:516–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyer D, Fine D. Sexual abuse as a factor in adolescent pregnancy and child maltreatment. Fam Plann Perspect 1992;24:4–11, 9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dietz PM, Spitz AM, Anda RF, Williamson DF, McMahon PM, Santelli JS, Nordenberg DF, Felitti VJ, Kendrick JS. Unintended pregnancy among adult women exposed to abuse or household dysfunction during their childhood. Jama 1999;282:1359–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiscella K, Kitzman HJ, Cole RE, Sidora KJ, Olds D. Does child abuse predict adolescent pregnancy? Pediatrics 1998;101:620–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hillis SD, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA, Marks JS. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics 2004;113:320–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saewyc EM, Magee LL, Pettingell SE. Teenage pregnancy and associated risk behaviors among sexually abused adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2004;36:98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stock JL, Bell MA, Boyer DK, Connell FA. Adolescent pregnancy and sexual risk-taking among sexually abused girls. Fam Plann Perspect 1997;29:200–3, 27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stevens-Simon C, Beach RK, McGregor JA. Does incomplete growth and development predispose teenagers to preterm delivery? A template for research. J Perinatol 2002;22:315–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szigethy EM, Ruiz P. Depression among pregnant adolescents: an integrated treatment approach. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:22–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noble KG, Fifer WP, Rauh VA, Nomura Y, Andrews HF. Academic Achievement Varies With Gestational Age Among Children Born at Term. Pediatrics 2012;130:E257–E64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spong CY. Defining “term” pregnancy: recommendations from the Defining “Term” Pregnancy Workgroup. JAMA 2013;309:2445–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Osterman M, Martin J. Timing and Adequacy of Prenatal Care in the United States, 2016 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2018. Contract No.: 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen S Contrasting the Hassles Scale and the Perceived Stress Scale - Whos Really Measuring Appraised Stress. Am Psychol 1986;41:716–8. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finkelstein DM, Kubzansky LD, Capitman J, Goodman E. Socioeconomic differences in adolescent stress: The role of psychological resources. J Adolescent Health 2007;40:127–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodman E, McEwen BS, Dolan LM, Schafer-Kalkhoff T, Adler NE. Social disadvantage and adolescent stress. J Adolescent Health 2005;37:484–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koniak-Griffin D, Anderson NLR, Brecht ML, Verzemnieks I, Lesser J, Kim S. Public health nursing care for adolescent mothers: Impact on infant health and selected maternal outcomes at 1 year postbirth. J Adolescent Health 2002;30:44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown MA, Robinson A, Bowyer L, Buddle ML, Martin A, Hargood JL, Cario GM. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in pregnancy: what is normal? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;178:836–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walker SP, Permezel MJ, Brennecke SP, Tuttle LK, Higgins JR. Patient satisfaction with the SpaceLabs 90207 ambulatory blood pressure monitor in pregnancy. Hypertens Pregnancy 2004;23:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brondolo E, colleagues. Racism and ambulatory blood pressure in a community sample. Psychosomatic medicine 2008;70:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brondolo E, Karlin W, Alexander K, Bobrow A, Schwartz J. Workday communication and ambulatory blood pressure: Implications for the reactivity hypothesis. Psychophysiology 1999;36:86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brondolo E, Rieppi R, Erickson SA, Bagiella E, Shapiro PA, McKinley P, Sloan RP. Hostility, interpersonal interactions, and ambulatory blood pressure. Psychosomatic Medicine 2003;65:1003–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jamner LD, Shapiro D, Goldstein IB, Hug R. Ambulatory Blood-Pressure and Heart-Rate in Paramedics - Effects of Cynical Hostility and Defensiveness. Psychosomatic Medicine 1991;53:393–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Karlin WA, Brondolo E, Schwartz J. Workplace social support and ambulatory cardiovascular activity in New York City traffic agents. Psychosomatic Medicine 2003;65:167–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carskadon MA, Wolfson AR, Acebo C, Tzischinsky O, Seifer R. Adolescent sleep patterns, circadian timing, and sleepiness at a transition to early school days. Sleep 1998;21:871–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R: Administration, Scoring of Proce- dures Manual-II for the R(evised) Version and Other Instru- ments of the Psychopathology Rating Scale Series Towson, MD: Clinical Psychometric Research Incorporated; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sarason IG, Levine HM, Basham RB, Sarason BR. Assessing Social Support - the Social Support Questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol 1983;44:127–39. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Edwards LJ, Simpson SL. An analysis of 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring data using orthonormal polynomials in the linear mixed model. Blood Press Monit 2014;19:153–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giesbrecht GF, Campbell T, Letourneau N, Kaplan BJ. Advancing gestation does not attenuate biobehavioural coherence between psychological distress and cortisol. Biological Psychology 2013;93:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Giesbrecht GF, Campbell T, Letourneau N, Kooistra L, Kaplan B. Psychological distress and salivary cortisol covary within persons during pregnancy. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012;37:270–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Giesbrecht GF, Granger DA, Campbell T, Kaplan B. Salivary alpha‐amylase during pregnancy: Diurnal course and associations with obstetric history, maternal demographics, and mood. Dev Psychobiol 2012;55:156–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Giesbrecht GF, Letourneau N, Campbell T, Kaplan BJ. Affective experience in ecologically relevant contexts is dynamic and not progressively attenuated during pregnancy. Archives of women's mental health 2012;15:481–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Giesbrecht GF, Poole JC, Letourneau N, Campbell T, Kaplan BJ, Team ftAS. The Buffering Effect of Social Support on Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Function During Pregnancy. Psychosomatic medicine 2013;75:PSY.0000000000000004–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards J, Gillman MW. A nearly continuous measure of birth weight for gestational age using a United States national reference. BMC Pediatr 2003;3:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brown MA, Lindheimer MD, de Swiet M, Van Assche A, Moutquin JM. The classification and diagnosis of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: Statement from the International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP). Hypertension in Pregnancy 2001;20:Ix–Xiv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Roccella EJ, Prog NHBPE. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure - The JNC 7 Report. Jama-J Am Med Assoc 2003;289:2560–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gifford RW, August PA, Cunningham G, Green LA, Lindheimer MD, McNellis D, Roberts JM, Sibai BM, Taler SJ, Pro NHBPE. Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;183:S1–S22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.DiPietro JA, Novak MFSX, Costigan KA, Atella LD, Reusing SP. Maternal psychological distress during pregnancy in relation to child development at age two. Child Dev 2006;77:573–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Evans LM, Myers MM, Monk C. Pregnant women’s cortisol is elevated with anxiety and depression - but only when comorbid. Arch Women Ment Hlth 2008;11:239–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr., Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr., Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:e127–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Samuels J, Samuel J. New guidelines for hypertension in children and adolescents. J Clin Hypertens 2018;20:837–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Melchiorre K, Sutherland GR, Liberati M, Thilaganathan B. Maternal Cardiovascular Impairment in Pregnancies Complicated by Severe Fetal Growth Restriction. Hypertension 2012;60:437–+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Redman CWG, Sargent IL. Placental debris, oxidative stress and pre-eclampsia. Placenta 2000;21:597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Redman CWG, Sargent IL. Immunology of Pre-Eclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol 2010;63:534–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]