Abstract

Purpose:

Adherence to pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is low. This qualitative study used the PRECEDE model to identify predisposing (intrapersonal), reinforcing (interpersonal), and enabling (structural) factors acting as barriers or facilitators of adherence to PR, and elicit recommendations for solutions from COPD patients.

Methods:

Focus groups with COPD patients who had attended PR in the past year were conducted. Sessions were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and coded independently by two coders, who then jointly decided on the final coding scheme. Data were summarized across groups, and analysis used a thematic approach with constant comparative method to generate categories.

Results:

Five focus groups with 24 participants were conducted. Participants, mean age 62 yr, were 54% male, 67% Black. More than half had annual income less than $20,000, 17% were current smokers, and 54% had low adherence (less than 35% of prescribed PR sessions). The most prominent barriers included physical ailments and lack of motivation (intrapersonal), no support system (interpersonal), transportation difficulties, and financial burden (structural). The most prominent facilitators included health improvement, personal determination (intrapersonal), support from peers, family, and friends (interpersonal), and program features such as friendly staff and educational component of sessions (structural). Proposed solutions included incentives to maintain motivation, tobacco cessation support (intrapersonal), educating the entire family (interpersonal), transportation assistance, flexible program scheduling, and financial assistance (structural).

Conclusion:

Health limitations, social support, transportation and financial difficulties, and program features impact patients’ ability to attend PR. Interventions addressing these interpersonal, intrapersonal, and structural barriers are needed to facilitate adherence to PR.

Keywords: adherence, pulmonary rehabilitation, COPD, qualitative research, patient perspectives

CONDENSED ABSTRACT

This qualitative study identified barriers and facilitators to pulmonary rehabilitation from the perspective of COPD patients. Health limitations, social support, transportation, financial difficulties, and program features impact ability of patients to attend sessions. Solutions included motivational incentives, tobacco cessation support, educating the entire family, transportation services, flexible scheduling, and financial assistance.

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), recommended in international guidelines for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),1 has been associated with improvements in quality of life, dyspnea, and exercise tolerance and a decrease in exacerbations and hospitalizations.2–5 Despite demonstrated benefits, uptake of PR is low.6–8 Research has focused on clinical (oxygen use, shuttle walking distance, lung function, exacerbations, hospitalizations, depression) and demographic (sex, smoking status, marital status) predictors of PR completion.6,9,10 Socioeconomic disadvantage has also been identified as a correlate of adherence.11 Expanding on the results of a quantitative study of adherence to PR,12 this qualitative research explored barriers and facilitators of adherence to PR using focus groups with COPD patients to identify potential adherence-promoting strategies.

METHODS

Theoretical Framework

Barriers and facilitators to PR exist on multiple levels, including individual, interpersonal, and health system.13 Therefore our analysis was guided by the PRECEDE model,14 which identifies predisposing (intrapersonal), reinforcing (interpersonal), and enabling (structural) factors relevant to health behaviors and programs. Predisposing factors involve the knowledge, beliefs, and values affecting decision-making. Reinforcing factors include the influence of family, friends, and others. Enabling factors include the socioeconomic, organizational, and policy factors influencing a health behavior. The PRECEDE model has been used successfully in interventions for HPV vaccination uptake,15 asthma self-management,16 and diabetes self-care,17 among others.

Study Design

This study constituted the qualitative phase of a mixed methods investigation with sequential explanatory design,18,19 whereby the collection and analysis of qualitative data followed the collection and analysis of quantitative data to increase the interpretability of results.20 The quantitative phase reported associations between social determinants and adherence to PR. Relative to high adherence (>85% of prescribed PR), moderate adherence (35–85% of prescribed PR) was associated with neighborhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage, including poverty, public assistance, households without vehicles, cost burden, unemployment, and minority population; while low adherence (<35% of prescribed PR) was associated with current smoking and poor functional health.12 The qualitative phase explored these associations in depth. Interview questions were guided by the PRECEDE model, asking about the role of intrapersonal factors (knowledge, beliefs, health status), interpersonal factors (family, friends), and enabling factors (financial considerations, transportation, and program features) for completion of PR.

Data Collection

The study population consisted of COPD patients who had attended PR in the previous 12 mo (n = 174). After excluding deceased and out-of-state patients, the final sample included 166 individuals. An adherence score was assigned to each individual based on the proportion of completed-to-prescribed PR sessions as described in the quantitative phase:12 high (>85% of prescribed), moderate (35–85% of prescribed), and low (<35% of prescribed). We aimed to conduct 5 focus groups with diverse representation of adherence levels. Therefore, we divided the sample (n = 166) into 5 source groups (n = 33 each with one n = 34) using the following scheme: from the low-adherence pool, every 5th individual was assigned to a source group, starting with group 1, until all were assigned; from the moderate-adherence pool, every 4th individual was similarly assigned; from the high-adherence pool, every 3rd individual was similarly assigned. A focus group was then recruited from within its respective source group. Contact was attempted with all 166 individuals. Focus group participants signed an informed consent and received a $50 gift card. A semistructured guide (Table 1) was used to prompt participants about challenges to attending PR, facilitators of completing PR, and strategies to help patients attend PR. Focus group sessions were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and de-identified for analysis. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham (Protocol X160907008).

Table 1.

Semi-structured Interview Guide

| Introductory questions | • What do you remember about your pulmonary rehab sessions? • Do you feel that it was hard to complete them all? Why or why not? • Why do you think some people complete all their sessions and others do not? |

| Overarching question | If we designed a program to help people attend all their rehab sessions,what should it include? |

| Probe questions | • What is your experience with having financial struggles or obligations? Do you think it influenced your ability to attend all sessions? • What do you think about the travel and transportation to the rehab clinic? • Does your family help your pulmonary rehab or does it make it harder? What about living alone? • Do you think your friends or neighbors influenced your ability to attend all your sessions? • What are some things that have helped you attend your rehab sessions? • If a program offered incentives to people to complete all their sessions, what would work for you? What reward or other factor would motivate you to complete all your rehab sessions? |

| Ending question | What is the most important thing we should know when designing a program to help COPD patients complete their pulmonary rehabilitation? |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Data Analysis

Data analysis used a thematic approach.21 A constant comparative method22,23 was employed to generate categories, patterns, and themes. Transcriptions were coded independently by 2 team members, then codes were discussed by the team, and the final coding scheme was decided jointly. Discussions contributed to the iterative data analysis and acted as respondent validation,24 helping achieve trustworthiness through investigator triangulation.25 Inter-rater agreement was assessed with Cohen’s Kappa (ĸ) with ĸ ≥0.81 considered to be near prefect agreement.26 Analyses were conducted with NVivo 11 (QSR International).

RESULTS

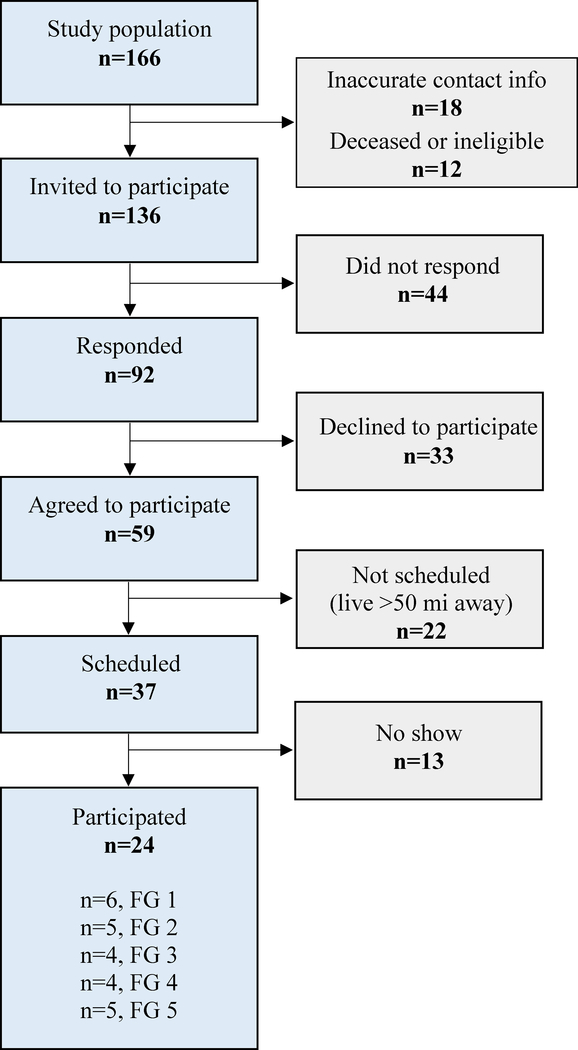

Figure 1 presents a STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) diagram of study participants. A total of 24 individuals participated in 5 focus groups (n = 6, 5, 4, 4, 5 persons/group, respectively). The characteristics of participants are presented in Table 2. Most participants were Black, with high-school education or less, household income <$20,000, and low PR adherence (<35% of prescribed PR). Focus group discussions identified barriers and facilitators to PR and recommended solutions. The themes from high-frequency codes are presented in Table 3.

Figure.

STROBE diagram of study sample. Abbreviations: FG, focus group; STROBE, STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and Adherence Characteristics of Participants (n = 24)a

| Characteristics | Total n = 24 | FG1 n = 6 | FG2 n = 5 | FG3 n = 4 | FG4 n = 4 | FG5 n = 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 62.3 ± 8.6 | 63.6 ± 11.9 | 63.0 ± 6.2 | 64.7 ± 7.2 | 59.3 ± 12.4 | 61.0 ± 4.8 |

| Male | 54.2 | 33.3 | 80.0 | 50.0 | 75.0 | 40.0 |

| Black | 66.7 | 100.0 | 80.0 | 50.0 | 25.0 | 60.0 |

| ≤ High school education | 66.7 | 83.3 | 60.0 | 40.0 | 25.0 | 60.0 |

| <$20,000/yr household income | 52.4 | 50.0 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 50.0 | 40.0 |

| Married or cohabiting | 43.4 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 50.0 | 25.0 | 60.0 |

| Current smoker | 16.7 | 16.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 20.0 |

| Adherence | ||||||

| Low (<35% of prescribed sessions) | 54.2 | 50.0 | 40.0 | 75.0 | 50.0 | 60.0 |

| Moderate (36–85% of prescribed sessions) | 20.8 | 16.7 | 20.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 20.0 |

| High (>85% of prescribed sessions) | 25.0 | 33.3 | 40.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 20.0 |

Abbreviation: FG, focus group.

Data reported as mean ± standard deviation or percent.

Table 3.

Unifying Themes, Subthemes, and Representative Codes

| Theme | Subtheme | Representative Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Barriers | Predisposing (Intrapersonal) | • Physical limitations • Lack of motivation |

| Reinforcing (Interpersonal) | • Lack of social support | |

| Enabling (Structural) | • Transportation difficulties • Financial struggles |

|

| Facilitators | Predisposing (Intrapersonal) | • Health improvement • Personal determination |

| Reinforcing (Interpersonal) | • Support from peers • Support from family and friends |

|

| Enabling (Structural) | • Flexible scheduling • Program characteristics: helpful staff, educational sessions |

|

| Proposed solutions | Predisposing (Intrapersonal) | • Incentives to maintain interest • Tobacco cessation support |

| Reinforcing (Interpersonal) | • Educating the entire family | |

| Enabling (Structural) | • Transportation assistance • Flexible scheduling • Financial assistance |

Barriers to Adherence

Predisposing (Intrapersonal) Barriers

The most frequent barrier was health limitations. Participants indicated that pain, lack of mobility, and physical ailments make it very difficult to attend PR sessions.

“I have arthritis, gout, and all combined in one. […]”

“I really don’t like getting on the Interstate, because my—I never know when my bronchitis will act up and my sugar most definitely acts up.”

Disease complications were also a prominent theme when discussing barriers to PR.

“I didn’t complete. […] And the first time that I was in it, I had pneumonia. And I really have—I have pneumonia a lot […]”

In addition to physical limitations, participants spoke of lack of motivation as a significant barrier to attending sessions:

“Like me for instance, you know the devil get in me some days, you know, some days I just don’t wanna get up. Especially on Mondays.”

Reinforcing (Interpersonal) Barriers

Participants described how lack of social and emotional support interferes with session completion.

“I really miss my wife cuz she attended all the sessions. […] You gotta have one that will be there for you.”

Enabling (Structural) Barriers

Most participants discussed transportation as a major barrier to attending PR. This theme included topics such as not having a car and having to rely on buses to get to sessions.

“A lotta people have problems with transportation. I’m havin’ it now. Because I ride the VIP bus and you can tell them I hafta be there at 9:15, and they don’t be on time. Sometime(s) they don’t get me to 10:30.”

The next most discussed barrier was financial struggles, including copays, costs not covered by health insurance, or lack of health insurance. Respondents described cost burden as a major hindrance to PR.

“You know, you have to come out your pocket for the copayments and all this. Sometimes I have prescriptions that run like $100, $150, you know. That’s every month. […] I have to see 3 or 4 doctors a month, you know. Sometimes, just $500 or $600 a month be just out of my pocket.”

Facilitators of Adherence

Participants were asked what helped their efforts to complete PR sessions. Again, predisposing (intrapersonal), reinforcing (interpersonal), and enabling (structural) stimuli were identified.

Predisposing (Intrapersonal) Facilitators

Seeing their health improve was the most important facilitator of adherence to PR. Participants felt motivated to complete their sessions when they saw that they could breathe better, walk more, or lost weight. Most everyone discussed the encouragement they felt when their symptoms improved, and these experiences served as powerful facilitators of treatment completion.

“Improving on my numbers. I hated the treadmill. But I’m up to a mile, and one-third of it without any oxygen. […] I’m looking at 40-something pounds that I’ve lost.”

Personal determination was discussed as an internal facilitator of adherence. Participants stated that when an individual had the will to complete their sessions they did not allow any barriers to interfere.

“Well, it’s just a mind game. If you feel like you need to do this, you’ll go and do it. But if you say I ain’t gonna do it, it ain’t gonna bother me none, you know, then you’re the one that’s losin’. […]”

Although determination was viewed mostly as an intrinsic quality of the individual (“It’s in the person”), some participants recognized that it can be externally motivated, for example by the desire to achieve a goal, such as the ability to spend time with one’s grandchildren or travel.

“For me it was the determination […] my dream is to be able to travel still. And it was frustrating sometimes but I was just determined.”

Reinforcing (interpersonal) facilitators

Participants underscored the importance of social support and emotional encouragement, and how it motivated them to remain in the program. The fellowship of and accountability to peers in the program were key to completing treatment.

“Actually, there’s some camaraderie there. […] I see what you’re doing today, and I look forward to being able to do that maybe. Or I see the struggles that maybe he has today, and I hope that I can encourage a little.”

Similarly, participants recounted the critical role their family and friends played in their treatment.

“My wife helps me a lot.”

“Family helps […] they keep reminding you to do it.”

“All my coworkers… All very supportive. Still watch after me.”

Enabling (Structural) Facilitators

Participants identified program staff as a positive driving force for attending sessions. The words “friendly,” “nice,” “encouraging,” and “smiling faces” were used to describe them. Participants were unanimous about the role of PR staff as a facilitator of adherence.

“[…] they friendly, they nice.”

Another facilitator was the educational component of sessions. Participants discussed at length the role of learning and reiterating basic information about their disease for completing the sessions.

“I learned how to take my pressure and my oxygen level and learned how to breathe. I didn’t know none of that and been goin’ in and outta the hospital all my life. But they taught me that.”

Proposed Solutions

Participants were asked what is most important in designing a program to help COPD patients complete PR. Insights into several areas was provided, with recommendations addressing predisposing (intrapersonal), reinforcing (interpersonal), and enabling (structural) factors.

Predisposing (Intrapersonal) Solutions

Participants stressed that PR sessions should be kept appealing by including group exercises, goal setting, and continued encouragement from staff. Two types of motivational incentives were suggested: (1) gift items such as food, medical samples, and free PR sessions or time with trainer; and (2) intangible incentives such as acknowledgement of progress or sharing accomplishments with peers and family. They also proposed the use of counseling, both during and after completion of the program.

“Maybe if you had a counselor around to help motivate ‘em cuz you’d be able to tell the ones that not motivated when they first come in the door.”

Second, participants recommended the inclusion of cost-free tobacco cessation services:

“But if they had more smoking cessation programs that insurances will cover.”

Finally, participants proposed expanding the educational component of PR programs because learning about their disease helped them understand their symptoms and make decisions about care:

“We could learn more about what COPD is […] and it can help you and affect you in your everyday life activities.”

“I think, explain why you take certain medications. […] I keep doing this every day and I don’t feel any different. You’re gonna save some money so you don’t get this prescription refilled. Then someone says, why aren’t you taking it? […]”

Reinforcing (Interpersonal) Solutions

Participants expressed a desire to see their entire family included in PR sessions and educated about COPD.

“Sometimes I wish though that they have some requirements for the program where my children who are in their 30s to sit in a session and maybe get a better understanding cuz I don’t sometimes think well they fully understand what I’m going through.”

Enabling (Structural) Solutions

Transportation services, flexible scheduling, and financial assistance were the main recommendations for structural solutions. In terms of transportation, suggestions included carpool, door-to-door escort service, and bus vouchers, among others:

“You know, you set your time up for your sessions to be as a group and you just come, you know, carpool together.”

“So, it wouldn’t be no problem if you maybe had somebody with a van […] that could go to her house […] and bring ‘em and take ‘em there.”

“Maybe by some of these transportation buses that pick you up and take you to the doctor and pick you up and take you to your rehab visits. You have a voucher for the bus and something like that.”

Participants also stated that PR programs should consider flexible scheduling or offer sessions in multiple locations. Expanded hours of operation and additional locations would also help alleviate transportation difficulties.

“Include scheduling that would accommodate everybody […] because everybody is on a different time.”

“If they schedule them in the evening time, I have no problem getting to them. Morning appointments, I have a problem getting to them.”

Participants further recommended financial assistance for patients who cannot afford PR.

“Work on establishing a fund to help people to remain in this program if it wasn’t covered by insurance. […] And if there were some funds available to cover cases where someone’s insurance wouldn’t cover.”

DISCUSSION

Guided by the PRECEDE model, this qualitative study used focus groups with COPD patients to identify barriers and facilitators to completion of PR. Study results showed that health limitations, social support, transportation, financial difficulties, and program features impact the willingness and ability of patients to attend PR. Our data also outline patient-proposed solutions to improve adherence to PR.

PR is a demanding task for COPD patients, who experience shortness of breath, limited mobility, and multiple comorbidities.27 Our results corroborate previous findings that poor functional health is a risk factor for non-adherence.28 They also suggest that personal determination is key for completing sessions. Although resolve has been identified as a predictor of adherence to PR, it has been discussed in the context of readiness as defined by the Transtheoretical Model.29 In our study, participants viewed determination as a personal disposition indicative of empowerment.30,31 The commonality of statements such as, “It’s got to be within the individual that’s willing to complete that program” and “You just have to have the will power to wanna do it,” coupled with the lack of references to powerful others, chance, or God, indicates a strong internal locus of control regarding PR.32 Nevertheless, more than half of participants had low adherence, suggesting that internal locus of control may be moderated by other factors, such as self-efficacy.33

Our data highlight the important role of health education for adherence to PR. Patient education is central to most PR programs and has been associated with improvement in dyspnea34 as well as self-efficacy and self-management skills.35 Our participants, while corroborating previous evidence, felt that education should be provided not only to the patient but also to his/her family to promote understanding of the disease and facilitate emotional and social support. Family involvement is a gold standard for effective treatments and interventions in tobacco cessation,36 substance use,37 and obesity.38,39 Harnessing the influence of family members through enhanced understanding of the benefits of PR and a broader understanding of the COPD disease can be a fruitful approach in PR programs.

Living alone or not having a support system, which have been found impactful for participation in PR,29 were identified as major barriers. Conversely, the fellowship of PR peers and staff served as a motivating factor and alleviated the social isolation commonly seen in COPD patients.40 Although home-based PR, or telerehabilitation, can reduce barriers related to access,41–43 it may not adequately address social isolation or may even exacerbate it. Future studies of home-based PR need to consider this potentially limiting aspect of tele-rehabilitation. Psychological well-being is an important correlate of quality of life and health outcomes in COPD,44,45 therefore it should be part of the long-term evaluation of distance-based programs.

The format and schedule of support groups needs to be carefully considered. For example, the clinical program from which study participants were recruited offers a monthly support group, but attendance is low. On the other hand, educational sessions have assumed some functions of support groups by connecting participants and giving them an opportunity to share experiences while learning about lung disease, respiratory devices, nutrition, or yoga. For the success of support groups, a prior assessment of needs and preferences may be necessary. Finally, in our clinical program, the introduction of a COPD order set for automatic PR referral at hospital discharge has increased the number of referred and enrolled patients, but has decreased adherence to PR, as larger proportion of participants are smokers, have multiple co-morbidities, and diagnosed depression.12 Referral, while essential for access, needs to go hand-in-hand with programs that address barriers to PR completion.

Along with intra and interpersonal factors, structural barriers such as transportation difficulties and financial burden were discussed. Participants deliberated on the challenges of getting to appointments and the prohibitive out-of-pocket costs that discourage participation. Transportation challenges46 and high Medicare copays for PR47 have been reported previously. Our results underscore the importance of socioeconomic factors for completion of PR.12

The study has several limitations. Although participants were sociodemographically diverse and included all levels of adherence, data may not be applicable to patients in other programs or geographic areas. As the interviews were retrospective, it may have been difficult for some to recall their experiences. Additionally, we did not interview caregivers or providers. While providers’ perspectives in PR have been studied,29 caregivers’ perspectives have not been explored, to the best of our knowledge. Hence, caregiver studies may be beneficial, particularly for addressing intra- and interpersonal barriers. The impact of out-of-pocket expenses also remains an understudied factor in uptake and completion of PR.

We previously reported that, relative to high adherence, low adherence is associated with markers of limited functional capacity and current smoking, while moderate adherence is associated with socioeconomic disadvantage.12 This study expands the understanding of factors that promote or inhibit adherence to PR. Together these 2 investigations highlight the synergistic role of health and socioeconomic status as independent predictors of suboptimal adherence to PR and point to the need for targeted approaches to optimize access to PR for all patients with COPD.

Conclusion

Both health limitations and socioeconomic disadvantage impact the ability of patients to attend PR. Interventions tailored to the needs of patient subgroups should be tested. PR programs should be flexible, accessible, family-centered and should promote patient engagement.

Acknowledgement

This project was supported by grant number K12HS023009 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rabe KF. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, Murphy K, Murphy E, Lacasse Y. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD003793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puhan M, Scharplatz M, Troosters T, Walters EH, Steurer J. Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(1):CD005305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schroff P, Hitchcock J, Schumann C, Wells JM, Dransfield MT, Bhatt SP. Pulmonary rehabilitation improves outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease independent of disease burden. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(1):26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayton C, Clark A, Olive S, et al. Barriers to pulmonary rehabilitation: characteristics that predict patient attendance and adherence. Respir Med. 2013;107(3):401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boutou AK, Tanner RJ, Lord VM, et al. An evaluation of factors associated with completion and benefit from pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2014;1(1):e000051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogg L, Garrod R, Thornton H, McDonnell L, Bellas H, White P. Effectiveness, attendance, and completion of an integrated, system-wide pulmonary rehabilitation service for COPD: prospective observational study. COPD. 2012;9(5):546–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heerema-Poelman A, Stuive I, Wempe JB. Adherence to a maintenance exercise program 1 year after pulmonary rehabilitation: what are the predictors of dropout? J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2013;33(6):419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown AT, Hitchcock J, Schumann C, Wells JM, Dransfield MT, Bhatt SP. Determinants of successful completion of pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:391–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiner MC, Lowe D, Beckford K, et al. Socioeconomic deprivation and the outcome of pulmonary rehabilitation in England and Wales. Thorax. 2017;72(6):530–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oates GR, Hamby BW, Stepanikova I, et al. Social determinants of adherence to pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2017:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox NS, Oliveira CC, Lahham A, Holland AE. Pulmonary rehabilitation referral and participation are commonly influenced by environment, knowledge, and beliefs about consequences: a systematic review using the Theoretical Domains Framework. J Physiother. 2017;63(2):84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green L, M K. Health Program Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dilley SE, Peral S, Straughn JM Jr., Scarinci IC. The challenge of HPV vaccination uptake and opportunities for solutions: Lessons learned from Alabama. Prev Med. 2018;113:124–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bailey WC, Richards JM Jr., Manzella BA, Windsor RA, Brooks CM, Soong SJ. Promoting self-management in adults with asthma: an overview of the UAB program. Health Educ Q. 1987;14(3):345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dizaji MB, Taghdisi MH, Solhi M, et al. Effects of educational intervention based on PRECEDE model on self care behaviors and control in patients with type 2 diabetes in 2012. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2014;13:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL, Gutmann M, Hanson W. Advanced mixed methods research desings In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, eds. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003:209–240. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greene JC, Caracelli VJ, Graham WF. Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 1989;11(3):255–274. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology: an overview In: Handbook of Qualitative Research. Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds.Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994:273–285. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research Procedures and Techniques for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bloor M Techniques of validation in qualitative research: a critical commentary In Context and Method in Qualitative Research. Miller G, Dingwall R, eds. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage;1997:37–50. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information. 2004;22(2):63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37(5):360–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noteboom B, Jenkins S, Maiorana A, Cecins N, Ng C, Hill K. Comorbidities and medication burden in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease attending pulmonary rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2014;34(1):75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selzler AM, Simmonds L, Rodgers WM, Wong EY, Stickland MK. Pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: predictors of program completion and success. COPD. 2012;9(5):538–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo S-E, Bruce A. Improving understanding of and adherence to pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD: a qualitative inquiry of patient and health professional perspectives. PloS One. 2014;9(10):e110835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rissel C, Perry C, Finnegan J. Toward the assessment of psychological empowerment in health promotion: initial tests of validity and reliability. J R Soc Health. 1996;116(4):211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nafradi L, Nakamoto K, Schulz PJ. Is patient empowerment the key to promote adherence? A systematic review of the relationship between self-efficacy, health locus of control and medication adherence. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rotter JB. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol Monogr. 1966;80(1):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallston KA. The validity of the multidimensional health locus of control scales. J Health Psychol. 2005;10(5):623–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ries AL, Bauldoff GS, Carlin BW, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2007;131(5):4S–42S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cosgrove D, Macmahon J, Bourbeau J, Bradley JM, O’Neill B. Facilitating education in pulmonary rehabilitation using the living well with COPD programme for pulmonary rehabilitation: a process evaluation. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hubbard G, Gorely T, Ozakinci G, Polson R, Forbat L. A systematic review and narrative summary of family-based smoking cessation interventions to help adults quit smoking. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Ryzin MJ, Roseth CJ, Fosco GM, Lee YK, Chen IC. A component-centered meta-analysis of family-based prevention programs for adolescent substance use. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;45:72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berge JM, Everts JC. Family-based interventions targeting childhood obesity: a meta-analysis. Child Obes. 2011;7(2):110–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skelton JA, Buehler C, Irby MB, Grzywacz JG. Where are family theories in family-based obesity treatment?: conceptualizing the study of families in pediatric weight management. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012;36(7):891–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anzueto A Impact of exacerbations on COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2010;19(116):113–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benzo RP, Kramer KM, Hoult JP, Anderson PM, Begue IM, Seifert SJ. Development and feasibility of a home pulmonary rehabilitation program with health coaching. Respir Care. 2018;63(2):131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bernocchi P, Vitacca M, La Rovere MT, et al. Home-based telerehabilitation in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2018;47(1):82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Selzler AM, Wald J, Sedeno M, et al. Telehealth pulmonary rehabilitation: a review of the literature and an example of a nationwide initiative to improve the accessibility of pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis. 2018;15(1):41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garrod R, Marshall J, Barley E, Jones P. Predictors of success and failure in pulmonary rehabilitation. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(4):788–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Putman-Casdorph H, McCrone S. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anxiety, and depression: state of the science. Heart Lung. 2009;38(1):34–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keating A, Lee AL, Holland AE. Lack of perceived benefit and inadequate transport influence uptake and completion of pulmonary rehabilitation in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative study. J Physiother. 2011;57(3):183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rajagopal A, Casaburi R. Pulmonary Rehabilitation: Improvement with movement. COPD. 2016;3(1):479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]