Introduction

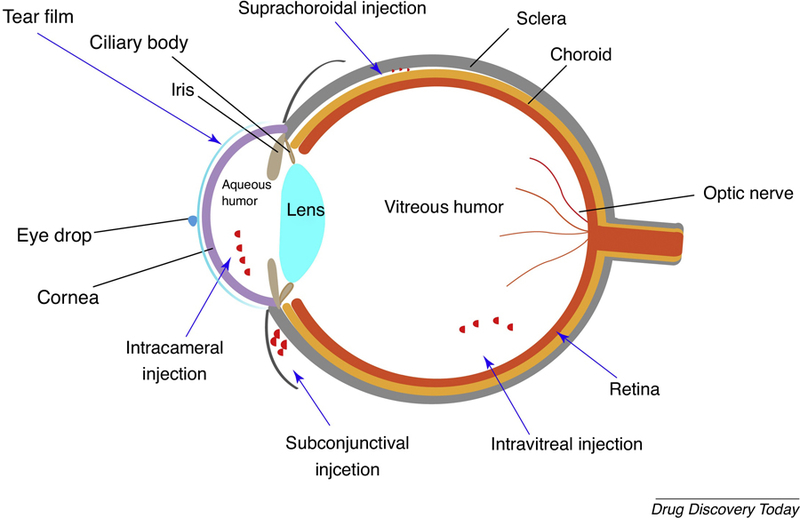

The eye is divided into the anterior segment and the posterior segment. The anterior segment includes the cornea, conjunctiva, aqueous chamber, iris, ciliary body and lens. Topical instillation of eyedrops is commonly used for treating anterior eye diseases because the front of the eye is readily accessible. However, topical eyedrops have poor ocular bioavailability owing to the corneal barrier, rapid tear film turnover and quick tear drainage. The posterior segment is composed of the choroid, retina and vitreous body [1]. Drugs delivered via eyedrops must travel a long distance and bypass various ocular barriers to reach the back of the eye, leading to minimal drug levels in the posterior segment. The presence of the blood–retinal barrier (BRB) prevents effective drug delivery via the systemic route to the eye, and very high doses are required, which can cause systemic side effects. Intravitreal (IVT) injections can directly deliver drugs to the back of the eye and are now commonly used in clinics for treating the relevant eye diseases. Free drugs can be cleared relatively quickly following IVT injections because of the vitreous humor turnover, and repeated IVT injections are needed to achieve good therapeutic efficacy (e.g., monthly IVT injections of Lucentis®, the anti-VEGF antibody Fab). Frequent IVT injections can be associated with high cost, poor patient compliance and increased risk of injection-related complications [2]. Thus, IVT drug delivery systems with prolonged drug-release profiles are needed to reduce the dosing frequency, improve therapeutic efficacy and benefit patients. Periocular administration through injecting drugs to the periocular space and/or tissue along the eyeball, such as subconjunctival (SCT), sub-tenon and peribulbar injections, is less invasive compared with IVT injections, but could still effectively deliver drugs to the back of the eye (Figure 1). Drugs need to permeate through the sclera, choroid and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) to reach the retina and vitreous. These ocular tissue layers represent drug transport barriers and significantly compromise the effective drug levels that can be delivered to the retina following periocular administration [3]. Suprachoroidal administration delivers drugs to the suprachoroidal space beyond the sclera, a crucial diffusion barrier encountered by periocular drug delivery, and is a promising strategy to deliver drugs to the back of the eye [4]. However, the suprachoroidal route can pose potential risks of retina hemorrhage and retinal detachment, and special devices (e.g., microneedles) are required for effective and safe suprachoroidal drug delivery [4].

Figure 1.

Scheme of the ocular anatomy and ocular nanomedicine administered through various routes including topical administration, subconjunctival injection, intravitreal injection, subretinal injection and suprachoroidal injection.

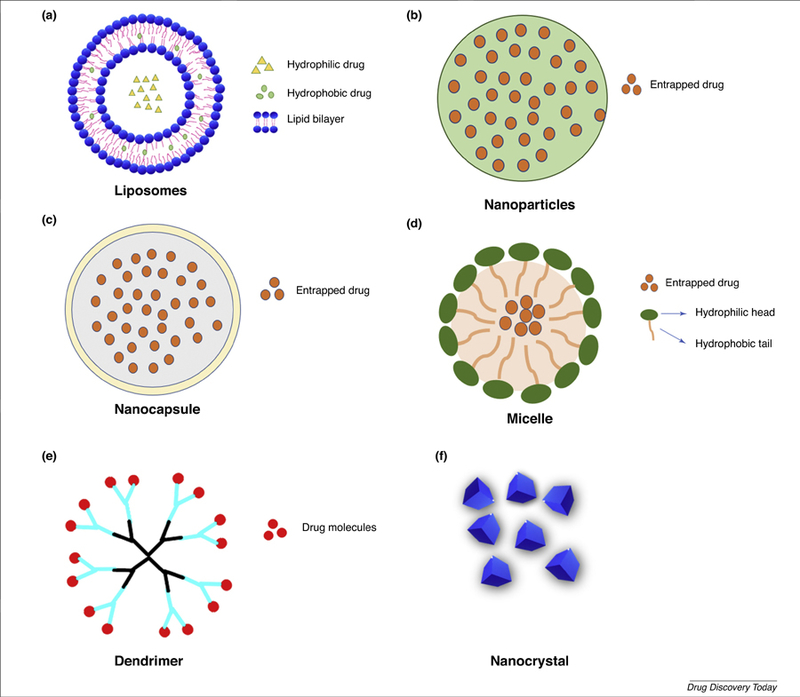

Nanomedicine can increase hydrophobic drug solubility in aqueous solution, provide sustained drug release with reduced toxicity and improved efficacy, prolong drug retention time and enhance drug penetration through ocular barriers, and even certain types of nanomedicines can target specific tissues and cells. Various nanomedicines have been developed for ocular drug delivery, such as liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles (NPs), micelles and dendrimers (Figure 2) [5]. Liposomes are lipid vesicles that are composed of phospholipids, cholesterol and other lipid-conjugated polymers with an inner aqueous phase. The liposomes can load hydrophilic drugs in the inner aqueous core and lipophilic drugs in the lipid bilayers [6]. Polymeric NPs can be engineered to load a high content of drugs and provide controlled drug release for prolonged periods of time. Dendrimers are globular, nanostructured polymers with a well-defined shape and narrow polydispersity (~3–20 nm). Drugs could be either entrapped in the dendrimer core or conjugated to the dendrimer surface functional groups. The drug-loading capacity and drug-release profile of dendrimers can be controlled by the dendrimer generation, surface chemistry and conjugation method [7]. Micelles are self-assembled spherical vesicles consisting of hydrophilic corona and a hydrophobic core, which shows the potential to solubilize and stabilize hydrophobic drugs [8]. Nanomedicines are promising for ocular disease treatment, currently there are several products either on the market (Table 1) or in clinical trials (Table 2). In this review, we focus on nanomedicines with great clinical translation potential, including liposomes, mucus-penetrating particles, polymer NPs, micelles and dendrimers [5].

Figure 2.

Scheme of representative nanomedicine platforms for ocular drug delivery. (a) Liposomes are small spherical vesicles with lipid bilayers. (b) Nanoparticles are usually made of biodegradable polymers for sustained drug release. (c) Nanocapsules typically consist of a lipid core and a protective shell with particle size from 10 nm to 1000 nm. (d) Micelles are self-assembled spherical vesicles consisting of hydrophilic corona and hydrophobic core. (e) Dendrimers are nanostructured macromolecules with uniform tree-like branches that can be used to encapsulate or conjugate drugs. (f) Drug nanocrystals are nanosized drug crystals stabilized with specific surface coatings.

Table 1.

Nanomedicine in the market for ocular disease treatment

| Trade name | Drugs/bioactives | Formulation | Disease | Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restasis® | 0.05% Cyclosporin A | Nanoemulsion | Dry eye disease | Allergan |

| Cyclokat® | 0.1% Cyclosporin A | Cationic nanoemulsion | Dry eye disease | Santen Pharmaceuticals |

| Cequa® | 0.09% Cyclosporine | Micelle | Dry eye disease | Sun Pharma |

| Lacrisek® | Vitamin A palmitate, vitamin E | Liposomal spray | Dry eye disease | BiOs Italia |

| Artelac Rebalance® | Vitamin B12 | Liposomal eyedrops | Dry eye disease | Bausch & Lomb |

| VISUDYNE® | Verteporfin | Liposomal injection | Wet AMD, myopia | Bausch & Lomb |

| Xelpros® | 0.005% Latanoprost | Microemulsion | Open-angle glaucoma | Sun Pharma |

| Dexycu® | 9% Dexamethasone | Intraocular suspension | Cataract surgery inflammation | EyePoint Pharmaceuticals |

| Inveltys® | 1% Loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension | Mucus penetration particles | Inflammation and pain after ocular surgery | Kala Pharmaceuticals |

| TIMOPTIC-XE® | Timolol maleate | Hydrogel topical eye drops | Glaucoma | Bausch & Lomb |

Table 2.

Nanomedicine under clinical trials for ocular disease treatments

| Products | Nanomedicine | Administration method | Disease | Trial | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brimonidine Tartrate | Nanoemulsion | Eyedrops | Dry eye disease | III | |

| CsA | Hydrogel | Eyedrops | Dry eye disease | II | |

| Sunitinib malate (GB-102) | Microparticle | IVT | Wet AMD | II | |

| Dexamethasone sodium phosphate (TLC399-ProDex) | Liposome | IVT | Diabetic macular edema | II | |

| LAMELLEYE | Liposome | Eyedrops | Dry eye disease | N/A | |

| AXR159 | Micelle | Eyedrops | Dry eye disease | II | |

| Difluprednate (PRO-145) | Emulsion | Eyedrops | Cataract | III | |

| Dexamethasone (AR-1105) | PRINT technology | IVT | Macular edema due to retinal vein occlusion | II | |

| Triamcinolone | Microsphere | IVT | Diabetic macular edema, diabetic retinopathy | I, II | |

| Dexamethasone-cyclodextrin | Microparticle | Eyedrops | Diabetic macular edema | II |

Nanomedicines for anterior diseases of the eye

The diseases affecting the anterior segment include glaucoma, cataract, inflammation, infectious diseases, injury and trauma, and dry eye, ultimately leading to functional blindness [9]. Anterior eye diseases are generally treated by eyedrops, but the rapid tear film turnover (15–30 seconds) will quickly dilute the eyedrops and drain the drugs through the nasolacrimal duct, and the remaining drugs will have to penetrate the cornea to reach the anterior chamber. The cornea has a compact multilayer structure comprising epithelium, Bowman’s layer, stroma, Descemet’s membrane and endothelium. The cornea is a significant barrier for effective permeation of drug molecules owing to the epithelium and collagen matrix of the stroma. The epithelium with tight junctions is the major barrier of corneal permeability for most drugs following topical administration. Beneath the epithelium is the corneal stroma, which is a highly hydrated tissue comprising collagen fibrils with regular arrangements. Only small molecules and relatively lipophilic molecules show relative penetration into the cornea [9]. The poor corneal penetration and retention of drugs, resulting in limited ocular bioavailability, requires repeated instillations to achieve therapeutic drug concentrations in the eye. The preservatives in eyedrops and spiked drug levels from the frequent eyedrop dosing can cause ocular surface toxicity. Various nanomedicines have been developed to prolong the drug ocular surface retention and improve the drug corneal penetration, such as mucus-penetrating NPs.

Topical administration nanomedicine for anterior segment drug delivery

Topical eyedrops are still the preferred dosage form because of convenience and good patient acceptance. The drug clearance typically occurs within 15–30 s owing to the tear film turnover, resulting in the intraocular bioavailability of topically applied drugs to the anterior segment being <5% (even <1% for many cases). Nanomedicines could prolong drug retention and provide controlled drug release, and thus increase drug ocular bioavailability and provide safe products for patients [10].

Topical administration of micelles.

Cyclosporine A (CsA) eyedrops have been used for the treatment of ocular inflammatory diseases including uveitis, keratoconjunctivitis and dry eye diseases (DED). The hydrophobic nature (solubility 10 μg/ml) and large molecular weight (1202.6 Da) of CsA rendered the development of aqueous eyedrops challenging. Initial formulations attempted to use surfactants to increase CsA solubility, but the ocular preservatives (e.g., benzalkonium chloride) in the formulation cause ocular irritation [11]. To solve the ocular irritation, various vegetables oils, such as corn oil and castor oil, and oil-based vehicles were applied to improve CsA dispersion in aqueous eyedrops. Restasis® is a preservative-free 0.05% oil-in-water emulsion of CsA and was the first CsA ophthalmic product approved by the FDA for DED treatment in 2002 [12]. In Restasis®, 0.5 mg/ml CsA was dissolved in castor oil with Polysorbate 80 as the emulsifying agent. The preservative-free emulsions (particle size 100–200 nm) overcame the toxicity shown in earlier preservative-contained oil-based formulations; however, Restasis® is still associated with side-effects including ocular irritation, instillation pain and epiphora [13].

Cequa® (OTX-101) is a micelle formulation containing 0.09% CsA. The micelles have particle sizes of 12–20 nm. The micelle formulation is composed of polyoxyl hydrogenated castor oil (HCO-40) and octoxynol-40 (OC-40), which could simultaneously form thermodynamic stable micelles through H-bonding. The improved stability generates an extremely low critical micelle concentration (CMC) of 0.00707 wt%, and the low CMC obtained for micelle formulation indicates its great ability to encapsulate CsA at a lower surfactant concentration [14]. The micellar formulation allowed a tenfold increase of CsA concentration in the aqueous eyedrop solution in comparison with water. A single topical administration of CsA micelle formulation provided 3.6-fold and 3.44-fold higher CsA levels in New Zealand White rabbit conjunctiva and sclera in comparison with the commercial oil-in-water emulsion formulation Restasis®, indicating micelles promote CsA penetration through conjunctiva and sclera. In Phase II and Phase III clinical trials, the Cequa® CsA micelle formulation demonstrated superiority over placebo micelle vehicles at day 84 after twice-daily topical instillation in terms of primary endpoint (mean changes from baseline in conjunctival staining score and global symptom score) and secondary endpoint (mean changes from baseline in tear breakup time, total corneal fluorescein staining score and Schirmer’s test score). For the toxicity and tolerability of the CsA micelle solution, the majority of subjects reported no or mild discomfort at 3 and 10 min post-instillation at day 84 [15]. The Cequa® formulation was approved by the FDA for DED treatment in 2018 [14]. The Phase II and III clinical studies did not include the Restasis® emulsion (twice a day), which is a well-accepted method for treating DED, as the control to provide a head-to-head comparison in terms of efficacy and safety outcomes. The safety evaluation only lasted for 12 weeks, which is much shorter than the DED treatment time-frame of 12 months [16]. The micelle technology improved CsA transscleral diffusion but still needs frequent dosing (twice a day) for clinical use, which does not further reduce the dosing frequency for patients who take Retstasis®. Additionally, topical Cequa® 4-times daily for 5 days achieved therapeutic levels of CsA (53.7 ng/g tissue) in rabbit retina and choroid tissues, which is very promising. However, the underlining mechanism as to how the micelle formulation enabled the drug transport to the posterior segment remains unclear. The data were only achieved in rabbits, not in human patients, and the potential use of Cequa® for treating back of the eye diseases needs further extensive preclinical and clinical evaluation. Micelles are typically nanosized (5–100 nm) [10], and Cequa® was specifically named as a ‘nanomicelle’, which might over-sell the ‘nano’ concept.

Topical administration of liposomal formulation.

Liposomes are biodegradable and biocompatible nanocarriers with an aqueous core and lipophilic bilayers. The physical structure of liposomes enables delivery of lipophilic and hydrophilic drug molecules. There are several liposomal products on the market for DED treatment, such as Tears again® and Lacrisek®. These liposomal formulations are composed of phospholipid phosphatidylcholine that provides lubrication, prevents tear film evaporation and attenuates dry eye symptoms. Liposomal formulations have been demonstrated to provide improved efficacy compared with traditional eyedrops. Lacrisek® (the liposome formulation of vitamin A palmitate and vitamin E) and nonliposomal Artelac Rebalance® (the PEG and hyaluronic acid based aqueous formulation of vitamin B12) eyedrops were administrated to 15 dry eye patients separately. Both formulations improved patient blinking frequency and corneal exposure, and the effects from the liposomal formulation Lacrisek® appeared to be quicker, stronger and more stable over time than those of the nonliposomal Artelac Rebalance® formulation. In particular, the liposomal eyedrops Lacrisek® provided progressive and sustained increase of the interblink interval up to 60 min after administration; however, Artelac Rebalance® showed protective effects only by 10 min. In comparison to the nonliposomal conventional eyedrops, liposomal eyedrops can better mimic the composition of tear film lipid layers and provide sustained integration with the lipid layers of the tear film and, thus, better efficacy. The liposomal formulations can also decrease tear film osmolarity and improve tear film stability [17]. Besides the liposomal eyedrops, liposomal sprays have also been developed, and have been shown to be more convenient for patients wearing contact lenses [18]. Optrex™ ActiMist™ is a liposomal spray of vitamin A and E for DED treatment, which provides instant relief and longer effects for up to 4 h. However, none of these formulations were used to treat the disease itself but to provide relief of the discomfort caused by dry eye. The therapeutic role of the vitamins in all these liposomal formulations was not fully justified. The liposomes without vitamins could also generate a certain degree of relief in symptoms through the lipid materials. Therefore, the placebo liposomes without vitamins (or other actives) should be used as a control. The exact benefits and advantages from liposomes as topical eyedrops are still not fully established. It could make liposomes a promising ocular drug delivery platform if more therapeutic ophthalmic liposomal formulations could be approved for other antifungal, antiviral, antibiotic and anti-inflammatory drugs.

Mucus-penetrating particles for enhanced ocular drug delivery.

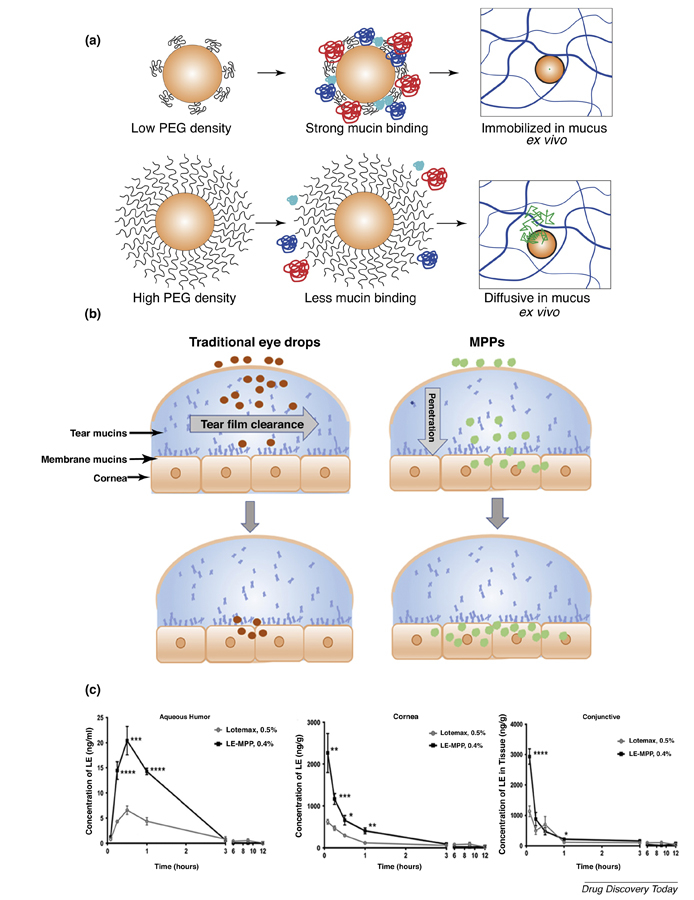

Tear film protects the cornea and conjunctiva from the external environment, and the tear film contains multiple layers with the mucus layer as the innermost layer [19]. Mucus is a viscoelastic gel that covers the surface of the eye and protects the underlying epithelium through removing foreign particles, pathogens and even particles from conventional particle-based drug delivery systems. The outer mucus layer comprises secreted mucins that can be cleared quickly by blinking and tear film turnover (15 to 30 s). The inner layer is formed by epithelium-tethered mucins (glycocalyx) that protect the corneal tissue and are cleared less rapidly [19]. The presence of carboxyl and sulfate groups on the mucin proteoglycans contributes to the negatively charged mucus layers. Mucus-penetrating particles (MPP) are NPs with sizes smaller than the mucus meshwork and dense muco-inert coatings to avoid adhesive interactions with mucins, thus can rapidly penetrate the mucus network to reach the epithelium and avoid rapid tear clearance. MPP could potentially provide improved drug retention and distribution at the ocular surface [20]. Dense surface coatings of PEG on NPs beyond a certain density threshold are crucial for MPP to achieve rapid penetration through mucus [20 and 22]. Xu et al. explored the influence of PEG density on the mucus-penetration capability of MPP [21]. PEG-coated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) NPs with different PEG coatings were prepared by blending PLGA-PEG di-block copolymer and PLGA at different ratios. PEG-coated PLGA NPs demonstrated PEG-density-dependent mucin-binding properties. Surface PEG density on NP (Γ: the number of PEG per 100 nm2) was measured by 1HNMR, and it was used to compare with the theoretical value required for full surface PEG coverage (Γ*) [21]. As the PEG density increased, the amount of bound mucin per nm2 on the NP surface was decreased and eventually reached a plateau value when the PEG density was ~10 PEG chains per 100 nm2 for PEG 5 kDa coated PLGA-PEG NPs, corresponding to Γ/Γ* of 2.4 (Γ/Γ*>2 indicating a dense brush PEG conformation) [22]. When PEG surface density is in the dense brush conformation (Γ/Γ*>2), the NPs diffused only 17-fold slower in human cervicovaginal mucus than their diffusion in water. But when the PEG density becomes only brush conformation (1<Γ/Γ*<2) the PEG-coated PLGA NPs still demonstrated significant mucin binding and their mucus penetration capability was greatly decreased by 142-fold (ten PEG chains per 100 nm2 or Γ/Γ* of 1.5 for PEG-5kDa-coated PLGA-PEG NPs) in human cervicovaginal mucus than their diffusion in water [22]. Therefore, dense brush PEG coatings are crucial for MPP.

MPP coatings can also be achieved through the noncovalent absorption of PEG-containing surfactants, such as Pluronic®. They are triblock copolymers of polyethylene oxide-polypropylene oxide-polyethylene oxide (PEO-PPO-PEO), which can form a strong coating on hydrophobic NPs through the PPO chains [23]. Certain Pluronics® (e.g., F127) have longer hydrophobic PPO chains (PPO MW >3 kDa) to provide strong hydrophobic absorption on the NP surface than other Pluronics® (e.g., F68) (PPO MW <3 kDa). The F127 coating produced NPs with nearly neutral surface charges whereas the F68 coating NPs exhibited −30 mV surface charge, indicating inadequate surface PEG coating. Besides, F127-coated NPs quickly penetrated through human cervicovaginal mucus only tenfold slower than their diffusion in water, regardless of the core materials. MPP eyedrops reduce particle adherence to mucins and lower particle elimination through tear clearance (Figure 3b), thus improving drug ocular pharmacokinetics. KPI-121 0.4%, a loteprednol etabonate (LE) drug crystal MPP formulation with F127 coatings, improved LE pharmacokinetic profiles in New Zealand White rabbit ocular tissues compared with commercial LE suspension (Lotemax® 0.5%) [24]. Single topical instillation of KPI-121 0.4% showed a threefold higher Cmax in rabbit aqueous humor, cornea and conjunctiva than Lotemax® 0.5% (Figure 3c). The MPP formulation provided nearly a 2-times higher LE bioavailability in cornea, aqueous humor and conjunctiva. With MPP, INVELTYS™ promotes LE ocular bioavailability and provides a twice-daily LE for the treatment of inflammation and pain following ocular surgery, compared with other steroids only approved for 4-times-daily dosing [25]. INVELTYS™ (MPP-LE 1% suspension) was approved by the FDA in August 2018. MPP are expected to greatly improve patient compliance and convenience with less frequent dosing. The conjunctiva possesses a 5-times greater surface area than the cornea, and the mucins associated with conjunctiva could also greatly contribute to the long retention of MPP [26]. Besides the absorbed muco-inert Pluronics® at the MPP surface, there are alsosoluble Pluronic® molecules in the solution, which could affect the ocular surface including the cornea–conjunctiva epithelium, the tear film and mucins. The MPP formulations are submicron drug crystals and are involved in the use of Pluronic® surfactants that can influence the dissolution profiles of drug crystals in comparison with the conventional drug suspension eyedrops with large particle size and different surfactant content. Extra in vitro drug dissolution studies would be helpful to understand the potential contribution from drug dissolution properties. Nevertheless, the complicated interactions between MPP formulations and the ocular surface need further investigations to fully elucidate the role of MPP toward the increased drug ocular bioavailability. Surprisingly, MPP technology was shown to increase LE concentration in the iris, ciliary body and retina in the rabbit pharmacokinetics study. The Cmax and AUC 0–12 h was threefold and twofold higher in New Zealand White rabbits treated with KPI-121 than in those treated with Lotemax® 0.5% in the iris, ciliary body and retina [24]. However, it remains unknown how MPP improved the drug penetration through so many ocular barriers to reach the back of the eye. It should be noted that the detectable drug levels in the retina were measured in rabbits, which have smaller eyes than humans. MPP formulations provide a big hope for using noninvasive eyedrops to treat the most challenging back of the eye diseases, and the future pharmacokinetic studies in human eyes following topical administration of MPP eyedrops would be the key.

Figure 3.

(a) Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)-PEG nanoparticles with low density PEG coating had strong mucin binding, which was related to immobilization within mucus. High PEG density coating avoids the adhesion of mucin on the surface of PLGA-PEG nanoparticles (MPP) in vitro, resulting in rapid diffusion in mucus ex vivo. (b) Traditional suspension eyedrops adhere to the mucins and are rapidly cleared from the tear film. MPP move through tear mucins to the epithelium-tethered mucins, allowing particle penetration to corneal epithelium. (c) Loteprednol etabonate (LE) pharmacokinetic profiles in rabbit aqueous humor, cornea and conjunctiva. Reproduced, with permission, from Refs.[76](a), and [24](c). Abbreviations: BID, twice daily; QID, 4-times daily.

Subconjunctival delivery of nanomedicines for anterior disease treatment

Nanotechnology-based eyedrops enhance drug corneal penetration and retention. Eyedrops can be quickly eliminated from the ocular surface, thus limiting the ocular bioavailability of topical drugs. SCT injection of nanomedicines can form a depot that provides sustained drug release to the anterior and posterior segments of the eye [27].

SCT administration of polymeric NPs for corneal diseases.

The sustained release of drugs from NPs, to reach the cornea or conjunctiva, enhances drug retention time at the ocular surface. However, even with MPP technology, the retention time of nanomedicine following topical instillation is short and repeated dosing is still needed. Periocular injection (e.g., SCT and sub-tenon) of nanomedicine can achieve sustained drug delivery to the anterior segment, and even to the back of the eye [28]. It was thought that drugs administered by SCT injection and sub-tenon injection penetrate the eye mainly through transscleral diffusion [29–31], a process that is limited for drugs that are poorly water-soluble [32–34]. However, the therapeutic effects of transscleral delivery of water-soluble drugs injected either SCT or sub-tenon are short-lived [35] such that frequent injections are required [36,37].

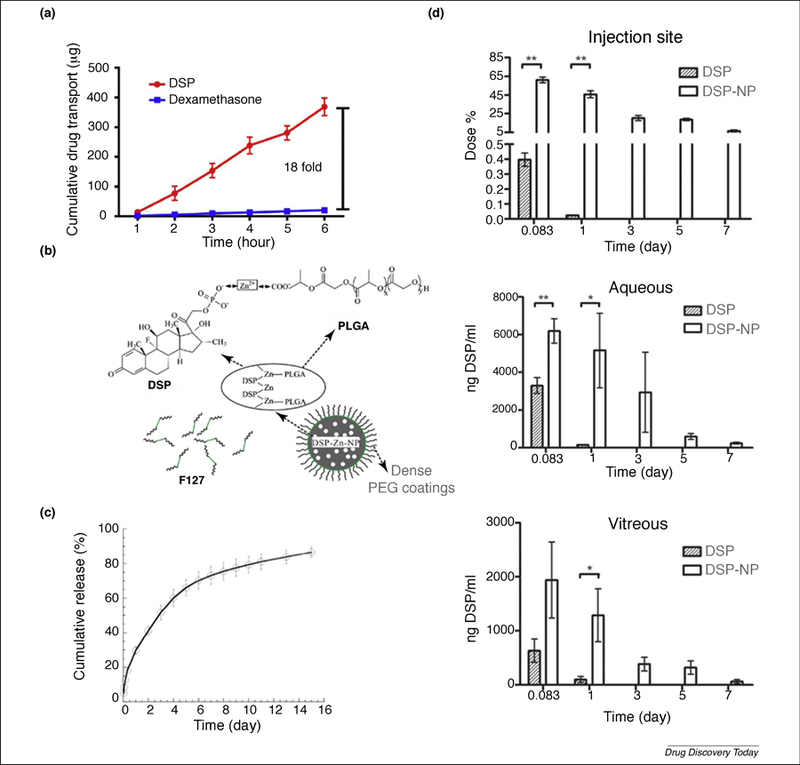

A standard approach to achieve sustained release of ophthalmic medications would be to load insoluble drugs like dexamethasone (DEX) in Ozurdex® (PLGA IVT implant) [38] or cyclosporine A in Lux201 (silicone episcleral implant) [39], although it is likely that the water-soluble version of drugs would have better transscleral penetration [32]. However, it would be more difficult to formulate water-soluble drugs for sustained release. Compared with hydrophobic DEX, the water-soluble form of DEX: dexamethasone sodium phosphate (DSP), provided an 18-fold increase of transscleral penetration (Figure 4a) [44]. Xu and colleagues developed a NP delivery system for DSP to treat corneal transplantation rejection using SCT injection without the use of frequent eyedrops [40]. The clinical standard for preventing corneal graft rejection following surgery is to prescribe topical corticosteroid eyedrops for administration 4–5-times a day for at least 1 month [37,41]. The requirement for frequent administration of corticosteroid eyedrops for extended periods is associated with low patient compliance [42]. Thus, there is a compelling need for a formulation that provides sustained release of corticosteroids to the front of the eye. The water-soluble DSP was encapsulated into PLGA NPs (DSP-NPs) using an ionic bridging method between the terminal carboxylic group on PLGA (LA:GA 50:50; MW 3.4 kDa) and the phosphate group on DSP (Figure 4b) [40]. The DSP-NPs provided sustained DSP release for >15 days at 37°C in vitro with no obvious burst release (Figure 4c). Similarly, DSP-NP (2 mg/ml DSP, 40 μl) provided delivery of DSP to the conjunctiva, aqueous humor and vitreous for >7 days, whereas DSP levels were nearly undetectable 1 day after soluble DSP solution (2 mg/ml DSP, 40 μl) injection (Figure 4d). SCT injection of DSP-NPs also achieved high DSP levels in the vitreous, indicating that SCT injection of nanomedicine can be used to treat back of the eye diseases. Observing the rat corneal allograft transplantation rejection model, when rats treated with weekly SCT injection of either free DSP solution, saline or placebo NPs, their grafts were completely rejected in less than 4 weeks. By contrast, corneal grafts in rats treated with weekly SCT DSP-NPs (100 µg DSP) remained clear and healthy and maintained 100% survival throughout the 9-week study [40]. Treatment of corneal graft immunological rejection without the need for compliance with frequent drop administration would be a great improvement in clinical management of corneal graft rejection. Achieving sustained, low but efficacious steroid levels in the eye could improve the treatment of various ocular disorders while removing the risk of noncompliance. Given the widespread application of corticosteroids, SCT DSP-NPs have the potential to treat many other ocular disorders, including corneal inflammation, corneal neovascularization [43], noninfectious uveitis [44] and post-surgical pain and inflammation.

Figure 4.

(a) Hydrophilic DSP provided 18-fold increase in transscleral diffusion over hydrophobic dexamethasone (DEX) at 6 h. (b) Scheme of encapsulation of dexamethasone sodium phosphate (DSP) into carboxyl-terminated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles using zinc ions. (c) Sustained DSP release in vitro under infinite sink conditions for DSP nanoparticles (DSP-NP). (d) Pharmacokinetic study of DSP-NP and DSP free drug solution at injection site, aqueous humor and vitreous humor after subconjunctival (SCT) injection in rats. Reproduced, with permission, from Refs. [44] (a), [43] (b), and [40] (c, d).

Weekly injection is still too often for clinical application, and long-lasting release of DSP up to 3–6 months can be potentially achieved through selecting slower degradable polymers such as more hydrophobic PLA polymers and higher molecular weight PLGA polymers. Topical use of corticosteroids always poses the risk of glaucoma and cataracts. Even no IOP increase was observed following weekly SCT injection of DSP-NPs (100 µg DSP) for 9 weeks in Lewis rats [40], the exact mechanism remains to be resolved through more-detailed studies in larger animals. Many FDA-approved ophthalmic products contain Zn2+, such as naphazoline-zinc-sulf-glycerin and zinc sulfate eyedrops. Despite being an essential nutrient and a popular supplement, zinc ions can be toxic at high concentrations. It was further demonstrated that more-frequent administration (four weekly injections), and thus higher dose, of the DSP-NP formulations did not cause retinal toxicity in healthy Lewis rats [44]. More standard pharmacokinetics and safety plus biocompatibility studies in larger animals, such as rabbits, need to be included as the next steps in development for DSP-NPs.

SCT delivery of liposomal formulations for anterior diseases.

Latanoprost is a hydrophobic drug that provides effective intraocular pressure (IOP) reduction and acts as the first-line medication for glaucoma treatment. The hydrophobic latanoprost is usually delivered as a once-daily 0.005% latanoprost solution (Xalatan®, Pfizer); however, long-term (3 months) topical administration of the Xalatan® solution leads to ocular irritation, blurriness and irreversible corneal epithelium yellow pigmentation which is caused by benzalkonium chloride, a preservative in latanoprost solution. Surprisingly, SCT injection of latanoprost-loaded liposomes demonstrated sustained IOP reduction in rabbits and non-human primates (NHPs) for up to 4 months [45–47]. Latanoprost was encapsulated into egg phosphatidylcholine (PC) liposomes with sizes of 100 nm and a drug:lipid ratio of 18.1%. The final drug loading was 1.18 mg/ml, which is 20-fold higher than the commercially available latanoprost eyedrops (50 μg/ml in Xalatan®) that need daily administration. The liposomal latanoprost formulation was reported to be stable for at least 6 months at 4℃and at least 1 month below 25℃without significant change in particle size. Latanoprost-loaded egg PC liposomes demonstrated sustained release of 60% of drugs within 2 weeks and 100% of drugs within 60 days in vitro [45]. The hydroxyl group in latanoprost and the carbonyl ester group in egg PC were believed to form favorable interactions, including H-bonding and weak van der Waals forces, which contributed to the liposome stability, and enhanced the drug loading and sustained the drug release. A single SCT injection of egg PC liposomes (0.1 ml containing 0.18 mg latanoprost) provided IOP reduction up to 90 days in New Zealand White rabbit eyes. The same liposomal formulation (0.1 ml containing 0.18 mg latanoprost), when applied to NHPs, provided sustained efficacy of lowering IOP for 120 days, much longer than the in vitro drug release, which was 60 days for complete release [46]. The average IOP reduction of latanoprost liposomes (14.99 mmHg) was comparable to the daily administration of Xalatan® eyedrops (15.03 mmHg). The second SCT injection of liposomal latanoprost formulations in NHPs conducted at day 120 resulted in sustained IOP reduction in the following 180 days. It was explained that the longer IOP reduction in NHPs was caused by the interaction between latanoprost and the pigment melanin, which is not distributed in the eyes of New Zealand White rabbits. Because melanin is an important factor for ocular drug delivery, Dutch belted rabbits with pigmented eyes should be considered at the ocular pharmacokinetics and efficacy studies. Latanoprost is a hydrophobic drug, which demonstrated very low water solubility of 40 µg/ml in saline [48], and it would be very interesting to find out how the hydrophobic latanoprost was effectively transported into the eye. A pharmacokinetics study could be added to detect the drug levels in the anterior chamber and the total dose remaining in the conjunctiva injection site with time, which would greatly support the long-term efficacy at reducing IOP following one single SCT injection of the liposomal latanoprost formulation. Currently, the latanoprost-loaded liposomal formulation has finished its Phase II clinical trials (), demonstrating clinically significant IOP reduction in glaucoma patients 6 months after one single SCT injection [46].

Water-soluble small-molecule drugs are crucial for effective SCT administration to treat eye diseases. Wong et al. further designed a PEGylated liposomal formulation of water-soluble corticosteroid derivatives, prednisolone phosphate and triamcinolone acetonide phosphate, and evaluated SCT injection of the liposomal steroids for the treatment of noninfectious anterior uveitis [49]. Dipalmitoylphosphatidyl choline, cholesterol and PEG2000 distearoyl phosphatidylethanolamine (PEG-DSPE) were used to prepare steroid liposomes with 100 nm diameter. The cyanine 5.5 (cy5.5) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) liposomes were prepared using the same method with additional 0.2% DSPE-cy5.5 and FITC. A single SCT injection of liposomal prednisolone phosphate or triamcinolone acetonide phosphate to New Zealand White rabbits provided sustained anti-inflammatory effects for 2 weeks, similar to daily eyedrops instilled 4-times daily for 2 weeks. Compared with prednisolone phosphate eyedrops, SCT injection of liposomal prednisolone phosphate formulations could suppress rebound inflammation 3 days after antigen re-challenge. Macrophage infiltration was shown in the ciliary body 30 days after inflammation induction, and cy5.5-liposome localization at macrophages and the ciliary body was detected 24 h after SCT injection. Liposome kinetics were evaluated through SCT injection of FITC-labeled liposomes, which showed a fast elimination at the first 24 h followed by slow elimination until 4 weeks at SCT. Certain amounts of fluorescent signal were detected in the cornea and aqueous humor during the 4-week interval. Considering the potential breakdown of liposome and degradation of lipids from liposomes, fluorescently labeled PEG-lipids and the cleaved dyes can also accumulate in macrophages, thus the localization of fluorescently labeled PEG-liposomes at macrophages and the ciliary body cannot fully confirm the transscleral diffusion of liposomes. The potential influence from lipids and dye molecules would also affect the liposome kinetics in the aqueous humor and cornea following SCT injection of fluorescently labeled liposomes. A detailed in vitro drug-release study and in vivo pharmacokinetic study would be very helpful to understand the efficacy following SCT injection of PEGylated liposome formulations of prednisolone phosphate and triamcinolone acetonide phosphate.

SCT administration of dendrimer for cornea drug delivery.

Corneal inflammation remains a major obstacle for cornea diseases, including DED, alkali burn damage and corneal graft rejection. Persistent corneal inflammation induces macrophage accumulation, leading to neovascularization, edema and vision loss [50]. The current strategy to treat corneal inflammation is topical administration of corticosteroid eyedrops, but the strategy demonstrates poor ocular drug bioavailability. Rangaramanujam and colleagues found hydroxyl-terminated poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimers could selectively target corneal macrophages and enable intracellular delivery of dendrimer-conjugated DEX (D-DEX) to attenuate corneal inflammation [51]. Because hydrogel is a useful controlled-release platform, the researchers constructed an injectable D-DEX hydrogel suitable for SCT injection. DEX was conjugated with hydroxyl-terminated generation 4 dendrimer (G4-OH) through a succinate linker. The D-DEX conjugates were small (5 ±0.4 nm) with a nearly neutral surface charge (5 ±0.2 mV). The injectable hydrogel was prepared via photopolymerization of D-DEX conjugate and hyaluronic acid. The D-DEX conjugate provided sustained DEX release for >120 days in vitro, whereas the hydrogel with free DEX only lasted for 40 days. At the 24 h and 7-day time point, ~5% and ~28% DEX were released, respectively, followed by ~56% DEX being released from 7 to 15 days. Using an alkali burn corneal inflammation model, which is involved with macrophage infiltration, SCT injection of cy5-labeled D-DEX hydrogels demonstrated the localization of cy5-D-DEX within corneal macrophages in the corneas with alkali burn, but not in the normal corneas. Moreover, single SCT injection of the D-DEX hydrogel system (1.76 mg DEX) provided sustained DEX release for up to 2 weeks with significant anti-inflammatory effects in the alkali burn rat model. In this study, the DEX linker between DEX and dendrimer contributed to the long-lasting DEX release. In addition to targeting cornea macrophages, SCT injection of D-DEX could also localize at the lacrimal gland, which was inaccessible through topical administration of the anti-inflammatory drugs during DED. Lin et al. investigated D-DEX distribution in the lacrimal gland and evaluated its efficacy after a single SCT injection of D-DEX to autoimmune dacryoadenitis rabbits [52]. D-DEX (2.5 mg DEX) following SCT injection was found to be localized in inflamed lacrimal glands for at least 2 weeks and inhibited inflammatory cytokine secretion in the lacrimal glands. In both studies, corticosteroid-related side effects were not observed during the 2 weeks of observation. The work from Dr Kannan’s lab suggests that dendrimers could enhance targeted delivery of therapeutic drugs to macrophages, activated microglia and lymphocytes under inflammation conditions of various eye diseases. The dendrimers were shown to be a promising drug delivery platform for treating inflammatory eye disorders by only targeting inflammatory cells without affecting the healthy cells. The most important benefit for such targeting capability from dendrimers is to be able to reduce off-target toxicity of drugs. Only hydroxyl-terminated PAMAM dendrimers have been investigated with demonstrated targeted effects in activated microglia and macrophages in the diseased eyes. Whether other types of dendrimers with different compassion, surface property and size (generation) show similar effects remains to be further investigated. Some efforts have been carried out to understand the exact mechanism by which dendrimer–drug conjugates can target activated microglia and macrophages; but it is still not fully understood. PAMAM dendrimers are nonbiodegradable, and they would be eliminated intact from the body through renal clearance [53]. Dendrimers as a nanomedicine have entered clinical trials () for safety and tolerance studies following systemic administration of PAMAM dendrimer-N-acetyl cysteine conjugate. The potential clinical translation of dendrimers for treating eye diseases is promising, and the long-term systemic and ocular safety studies following intraocular administration will help to address many concerns regarding the safety of dendrimers as ocular drug delivery systems.

Nanomedicine application to the posterior segment of the eye

The main challenge for retinal disease treatment is the ineffective drug delivery to the posterior segment. Owing to the nonspecific absorption and blood–retinal barrier, the systemic route delivers drugs to the eye at low rates with high risk of systemic toxicity to other tissues. IVT and SCT injections can deliver drugs to the retina but the potential risks associated with increased numbers of injections require new drug delivery systems.

Intravitreal injection of nanomedicines directly delivers drug to the retina

IVT injection can directly deliver sufficient amounts of drug to the retina. However, drug molecules are rapidly cleared from the vitreous requiring repeated administration. Standard treatment of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is IVT injection of ranibizumab every 4 weeks. The frequent IVT injection increases the risk of retinal detachment, hemorrhage and endophthalmitis [54]. Nanomedicine can remain in the vitreous and provide therapeutic concentrations of drugs at the target site for prolonged periods after injection, and thus reduce the need for frequent IVT injections [55].

NP diffusion in vitreous humor.

The vitreous is a highly hydrated (98–99% water) gel that fills the space between the retina and the lens. IVT injection of biodegradable nano-or micro-particles is promising for drug delivery to treat vitreoretinal disorders, and the microstructure and microrheology of the vitreous are important parameters influencing the pharmacokinetics and efficacy of IVT drugs and drug carriers. In some cases, like gene therapy, NPs need to diffuse rapidly from the site of injection to reach targeted cell types in the back of the eye, whereas in other cases it might be preferred for the particles to remain at the injection site and slowly release drugs that can then diffuse to the site of action [56]. The vitreous is composed of a delicate mesh network of gel-forming collagen fibrils and hyaluronan molecules; and it is susceptible to liquefaction. Xu et al. developed an ex vivo method that preserves the structural integrity of the fragile vitreous gel, combined with high-resolution multiple particle tracking (MPT) to quantify the transport mechanisms of individual particles in the vitreous and calculate the vitreous microrheology [56]. The movement of model polystyrene (PS) NPs with various particle sizes and surface charges was used to calculate mesh size and microrheology of bovine vitreous. Positively charged PS NPs were immobilized in bovine vitreous gel, regardless of particle size as a result of the electrostatic interactions of positively charged NPs with the negatively charged vitreous gel components. Negatively charged NPs coated with –COOH with size 100–200 nm and concentration <0.0025% (w/v) diffused in the bovine vitreous gels, but NPs aggregated and bundled in the vitreous mesh at high concentrations (0.1% w/v). By contrast, the densely PEG-coated NPs with neutral surface charge exhibited nonadhesive interactions with bovine vitreous gels, and NPs <500 nm can rapidly diffuse in the vitreous, exhibiting a higher viscous modulus than elastic modulus, indicating that the bovine vitreous behaves as a viscoelastic liquid for particles <500 nm. NPs >1000 nm were trapped and the vitreous gel behaved as a viscoelastic solid. The vitreous undergoes a length-dependent microrheology transition, which impacts the nanomedicine or drug diffusion in the vitreous. The findings provided the basis for further development of intravitreal drug and gene delivery platforms to treat diseases of the eye. In this study, only bovine eyes were used to study particle diffusion in, and the microrheology of, the vitreous. Bovine vitreous cannot mimic the vitreous of human eyes, especially aged human eyes with a significant degree of vitreous liquefaction. However, it is not practical to get human donor vitreous samples without significant structural damage because of the delay in tissue collection and long tissue storage time required.

Braeckmans and colleagues explored diffusion rates and RPE cell uptake of nonviral polymeric gene nanomedicines, which are composed of cationic, N,N′-cystaminebisacrylamine-4-aminobutanol and plasmid DNA coated with differing MW hyaluronic acids (HAs) [57]. Low MW HA (20 kDa and 200 kDa) increased the intravitreal mobility of noncoated cationic polyplexes but no improvement was observed if polyplexes were coated with high MW HA (>1.8 MDa). HA is a ligand for the CD44 receptor which is expressed on RPE cells, and HA coatings could lead to CD44-regulated RPE cell uptake. NPs coated with low MW HA have small particles size, <600 nm, which could contribute to the increased diffusion rates in the vitreous humor. High MW HA coatings might contribute to particle aggregation that limits particle mobility. HA coatings facilitated NP diffusion in vitreous gel to reach the RPE cells without reduced RPE cell uptake, which would be common for NPs with dense PEG coatings. RPE is the inner layer in the retina and these HA-coated polyplexes must still penetrate many other retinal layers (e.g., photoreceptor layer) before reaching the RPE. In vivo studies are needed to prove the concept to use IVT injection of HA-coated polyplexes for RPE gene therapy.

Intravitreal injection of NPs for retinal diseases.

Over 40% of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) [58] and wet AMD [59] patients do not fully respond to the current antiangiogenic therapies of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antagonists, such as bevacizumab (Avastin®), ranibizumab (Lucentis®) and aflibercept (Eylea®). Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 is a transcription factor and controls the expression of several proteins involved in neovascularization (NV), such as VEGF, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), their receptor and many other proangiogenic molecules. Doxorubicin (DXR) is a HIF-1 inhibitor that inhibits HIF-1 transcriptional activity and downregulates expression of proangiogenic factors causing strong suppression and regression of ocular NV. However, free DXR is rapidly cleared following intraocular injection, so the effects are too short-lived to be a viable alternative to current frontline therapeutics. Also, DXR caused reductions in b-wave amplitudes on electroretinograms (ERGs) and damaged the retina when doses were increased to elongate the duration of the activity [60]. To maintain low-level and safe DXR concentrations in the eye for long periods of time, injectable NPs were developed using a new biodegradable polymer DXR-poly(sebacic acid)-(polyethylene glycol)3 (DXR-PSA-PEG3), in which DXR was covalently conjugated [61]. The polymer contains a ‘tri-PEG’ on every chain resulting in dense PEG surface coatings on NPs, which were confirmed to be able to eliminate inflammatory responses to injected particles [62,63]. The dense PEG coatings enabled particles with neutral surface charge to avoid macrophage infiltration and reduced inflammatory reactions caused by injection [63]. The 650 nm DXR-PSA-PEG3 NPs with 23.6% DXR content provided sustained in vitro drug release for 7 days without an initial burst release. The IVT DXR-PSA-PEG3 NPs (10 μg DXR) provided prolonged suppression of subretinal neovascularization for at least 35 days. Pharmacokinetic studies in rabbit eyes following IVT injection of DXR-PSA-PEG3 NPs (650 nm, 2.7 mg DXR) demonstrated that NPs provided an effective DXR concentration (>200 nM DXR concentration) in the vitreous and aqueous humor for at least 105 days. When the particle size was further increased to 23 μm, the drug loading was 17.2% and the in vitro drug release greatly increased to nearly 50 days. The particles with bigger particle size achieved more-sustained drug release owing to the slower polymer surface erosion [64]. It would be expected to have more sustained efficacy from 23 μm microparticles at treating retinal neovascularization because 650 nm NPs achieved 105 days effective drug levels in mouse eyes. The NP system provided sustained release of DXR which significantly inhibited neovascularization without showing obvious retinal toxicity. However, the toxicity was only evaluated on mice for 2 weeks, and a detailed long-term dose-dependent ocular toxicity study of DXR-PSA-PEG3 nano-and micro-particles in large animals would be helpful to address the safety issues as the next steps of development.

Fenofibrate is a peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR)α agonist and has shown its therapeutic potential in PDR and wet AMD. Fenofibrate suffers from poor water-solubility and low ocular bioavailability following systemic administration, and can be quickly cleared from rat eyes after IVT injection (only lasts 4 days) [65]. Qiu et al. developed fenofibrate-loaded PLGA NPs (Feno-NPs) to provide sustained release of fenofibrate for treating ocular neovascularization [66]. Fenofibrate was encapsulated in PLGA (50:50) 34 kDa polymer with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) as an emulsifier using the emulsification solvent evaporation method. Feno-NPs exhibited ~6 wt% drug loading, 250 nm particle size and nearly neutral surface charge. Feno-NPs provided sustained drug release for 2 months in vitro. A single IVT injection of 5 μl Feno-NPs (30 μg fenofibrate) exhibited sustained levels of fenofibric acid (the parent drug of fenofibrate) in rat eye cups for 2 months. Feno-NPs significantly attenuated retinal vascular leakage and retinal edema in STZ-induced diabetic rats and laser-induced choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in rats for at least 8 weeks. The drug-loading and drug-release periods can be further increased by using polymers with different compositions and MWs, or through constructing particles with larger particle sizes.

Sunitinib malate is a multiple receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) that selectively inhibits VEGF receptors, PDGF receptors, colony-stimulating factor receptors and Fms-related tyrosine kinase receptors [67]. TKI inhibition provides blockage of multiple neoangiogenesis processes associated with wet AMD and provides better effects than selective blockage of VEGF alone. Sunitinib malate is an FDA-approved anticancer drug and can provide neuroprotective effects to retina ganglion cells in choroidal neovascularization [68]. GB102 is a sunitinib-malate-loaded PLGA-PEG microparticle delivery system, which aggregates into a biodegradable depot and localizes at the periphery of the inferior vitreous without visual interference after IVT injection [69]. The hydrophilic coatings avoided the toxicity and inflammatory reactions caused by IVT injection of PLGA particles [62,63]. IVT injection of GB102-containing 0.2 mg sunitinib malate through a 27G needle provided >20 ng/ml sunitinib in the retina and >2000 ng/ml in the RPE at 4 months, which were 10-and 1000-fold higher than the plasma level of free sunitinib (~2 ng/ml) needed for anticancer therapy. Preclinical studies have already proven the long-term efficacy of sunitinib release from PLGA-PEG microparticles following IVT injection in rabbit choroidal neovascularization models [70]. The injectable particulate depot provided sustained choroidal neovascularization inhibition in Dutch belted rabbits for 6 months. GB102 is in a Phase I/IIa clinical trial () as a potential therapy for twice-yearly IVT injections, thus reducing the burden of repeated IVT injection to patients. Currently, the second-generation formulation GB103 which is expected to provide once-yearly treatment is under preclinical evaluation. The technical details about GB102 and GB103 PLGA-PEG formulations are not fully available to the public. However, we should appreciate the strength of using PLGA and PLGA-PEG polymers with higher MW and a higher percentage of lactic acid to adjust sustained drug-release profiles. The wide spectrum of available PLGA and PLGA-PEG polymers gives the field a lot of freedom to develop more-sophisticated formulations with desired in vitro and in vivo properties. If GB102 and GB103 become successful through clinical trials, it would be very promising to use similar platforms to sustain release of many other drugs for treating various back of the eye diseases.

Intravitreal injection of dendrimers for retinal disease treatment.

Retinal microglia activation occurs in ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury, diabetic retinopathy and AMD. Hydroxyl-terminated PAMAM dendrimer can target activated microglial cells or macrophages under neuroinflammation [71]. Kambhampati et al. evaluated the uptake of cy5 chemically labeled hydroxyl terminated PAMAM G4 dendrimers in rabbit retina and other tissues following IVT injection. The localization and retention of dendrimers in activated microglia in I/R rabbit eyes was observed, and IVT injection of dendrimers provided 21 days retention in activated microglia in I/R rabbit eyes [72]. By contrast, dendrimers were almost completely cleared from normal eyes within 72 h after IVT injection. Intriguingly, G4-OH PAMAM dendrimers were shown to target and be retained in activated microglia in I/R rabbit eyes only, not the normal eyes, for 21 days following intravenous (i.v.) injection [72]. The effective microglial targeting and rapid clearance from off-target tissues suggests that systemic i.v. injection of dendrimers might provide effective drug delivery to the retina with minimum nonspecific dendrimer toxicity to other tissues, improving patient compliance by avoiding IVT injections. However, the exact mechanism of why hydroxyl-terminated PAMAM dendrimers can target activated microglia is still not clear, and more studies need to be done.

Hydroxyl-terminated G4-dendrimer fluocinolone acetonide (D-FA) was delivered through IVT administration to attenuate retinal inflammation of macular degeneration in rats [73]. To reduce the steric hinderance and provide better drug release, glutaric acid was used as a linker to synthesize FA carboxylic acid prodrug which was reacted with G4-OH to get the final G4-FA with ~5.5 FA molecules per dendrimer. FA was released from D-FA through the hydrolysis of the ester bond between the drug and dendrimer. D-FA provided sustained drug release of FA for 90 days in vitro. Dendrimers were selectively localized within activated outer retinal microglia in Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) retinal degeneration rats and transgenic S334ter retinal degeneration rats, whereas dendrimers were not found in the outer retinal layer of healthy rats. In the RCS retina degeneration model, IVT injection of D-FA (1 µg FA) provided significant therapeutic effects for 1 month when peak retina degeneration occurred, evidenced by the reduced outer nuclear layer, preserved ERG b-wave amplitude and inhibited microglia activation, which were not shown in free-FA-treated groups at the same dosage. The D-FA provided targeted attenuation of inflammatory responses during retinal degeneration, but microglia activation is not the only cause of AMD, which involves RPE dysregulation.

The increased efficacy and specific targeting at retinal cells suggested that dendrimers might be a favorable carrier for retinal delivery. Compared with IVT injection, systemic i.v. injection could be more acceptable and safer for some patients. The D-TA and dendrimer-N-acetyl cysteine (D-NAC) conjugates were found to selectively localize in activated microglia and macrophages upon i.v. injection to rats with choroid neovascularization (CNV) [74]. D-NAC and D-TA via i.v. injection were found to be retained in the retina and choroid for >30 days. D-NAC injection suppressed 78% CNV growth and reduced 63% microglia and macrophage activation occurring in early AMD. The combination treatment of D-NAC and D-TA promoted 72% CNV regression in late AMD. The efficacy of D-NAC in the eye through IVT injection was not reported, and the long-term systemic toxicity from i.v. injection of D-NAC has not been demonstrated yet. Currently, D-NAC has moved to a Phase I clinical trial for treating childhood cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy and Parkinson’s disease (), in which D-NAC will be administrated through i.v. injection.

SCT delivery of nanomedicines for the back of the eye diseases

SCT injection is less invasive and commonly used for treating ocular inflammation and infection. It can deliver drug to anterior and posterior segments of the eye [75]. Clinical research found that SCT injection of DSP solution (2.5 mg DSP) resulting in 72.5 ng/ml DEX in patient vitreous 3 h after injection, which is 3-times and 12-times higher than that through peribulbar injection of 5 mg DSP and oral administration of 7.5 mg DEX, respectively. Besides, the estimated maximum DEX in aqueous humor was 852 ng/ml at 2.5 h after administration [35]. Drug administered by SCT injection is thought to penetrate into the eye through transscleral diffusion which is limited for drugs with poor water solubility [34].

Pan-uveitis is an intraocular inflammation that affects anterior and posterior segments of the eye. Clinical treatment includes systemic application of a high dose of corticosteroids, which can cause severe side effects, such as hypertension, diabetes and secondary glaucoma [77]. Luo et al. explored The SCT injection of DSP-NPs for treating rat experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU) [44]. DSP-PLGA-NPs made of carboxyl-terminated PLGA (50:50) 5.6 kDa exhibited >6% DSP loading and provided sustained DSP release for up to 4 weeks in vitro; and achieved detectable DSP in the anterior and vitreous for at least 3 weeks in healthy Sprague–Dawley rats. In a rat EAU model, a single SCT injection of DSP-NPs significantly reduced inflammation in the anterior and posterior segments of the eye compared with DSP solutions. DSP-NP efficacy was evidenced by a reduced clinical disease score, decreased expression of various inflammatory cytokines and preserved retinal structure and function. DSP-NP formulation provided protection in an acute rat uveitis model; however, the DSP-NP efficacy in chronic autoimmune uveitis models in which inflammation lasts for up to 4 months still needs to be evaluated. More-detailed pharmacokinetics and efficacy evaluation on large animals would be helpful to demonstrate the capability of SCT injection of DSP-NPs for treating diseases affecting anterior and posterior segments of the eye. Clinical studies have already revealed high concentrations of DEX in aqueous and vitreous humor after SCT injection of DSP in human eyes [35]. Therefore, SCT injections of biodegradable NP formulations serve as a less invasive route for treating anterior and posterior eye diseases.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

Nanomedicine is a promising platform for ocular disease treatment; but it is still challenging for translation from the bench into clinical products. There are several aspects associated with nanomedicine development: to prepare uniform NPs with reproducible characteristics on a large scale and control potential toxicity and safety issues associated with ocular nanomedicine.

Scale-up and reproducible production of ocular nanomedicines

Advanced nanofabrication technologies, such as particle replication in non-wetting template (PRINT) [78] and the hydrogel template method [79], have been introduced to manufacture nanomedicine for ocular use. PRINT technology is a nanofabrication method capable of producing monodispersed NPs and microparticles with a certain size, shape and modulus using manufacturing roll-to-roll [78]. There are three steps for the NP fabrication using PRINT technology: the first step is to fabricate micromolds with precise micro-or nano-cavities; the second step is to mold pharmaceutical materials into cavities; and then PRINT particles can be removed from the mold after being solidified. PRINT particle physiochemical properties could be modified by changing matrix composition or through post-functionalization, thus preparing reproducible particles with controlled shape, size and surface modification at a large scale using a continuous process [78]. The PRINT technology has shown its compatibility with a variety of biocompatible polymers and drugs including nucleic acids, proteins and antibodies [78]. With PRINT technology, different ocular formulations, including SCT implants, intracameral implants, IVT implants, nano-and micro-suspensions, have been developed for controlled drug delivery to the eye. AR13503 is a potent Rho kinase and protein kinase C (PKC) that is under development for treating retinal neovascularization. The AR13503 implant was manufactured by PRINT technology by using various biodegradable polymers PLGA/PDLA/poly(ester amide) (PEA) with a rod-shape and size suitable for injection through a 27 gauge needle [80]. PRINT-based AR13503 implants provided sustained release for >60 days in vitro. The PRINT-based AR13503 implant is expected to enter clinical trials in 2019 for treating diabetic macular edema (DME) and wet AMD. PRINT technology has shown its potential for GMP production of kg quantities of NPs.

The hydrogel template method can fabricate large quantities of homogenous nano-and micro-particles that can be delivered while they are still in the template. Nanowafer is an ultra-thin transparent lens containing nanodrug reservoirs that were prepared via a hydrogel template technology [79]. A silicon wafer template was fabricated using e-beam lithography, and PVA solution was poured onto a silicon wafer to prepare the PVA template containing arrays of wells. Drug-loaded nanowafers were prepared by filling drug solutions into the PVA template. Drug loading and particle size can be controlled through adjusting the size of drug reservoirs. Nanowafers can be directly placed on the ocular surface to provide sustained drug release. Compared with conventional contact lenses, which need to be removed from the eye to avoid bacterial infection, nanowafers are made of dissoluble PVA that can be dissolved away automatically.

Safety and toxicity profiles of ocular nanomedicines

With multiple neuron cells, the retina can be a potential target of nanomedicines to induce neurotoxicity. To promote clinical translation of nanomedicines, the safety and toxicity profiles need to be fully investigated [81]. Nanomedicine toxicity is influenced by many factors including but not limited to administration dose, particle shape, surface charge and functional groups. The disease pathophysiology conditions have significant influence on nanomedicine safety profiles. G4-OH dendrimer was shown to selectively localize in inflamed tissues while quickly being cleared from normal tissues. G4-OH-modified PAMAM dendrimers have shown safety profiles in different neuroinflammation models following IVT, SCT and i.v. injections [51,73,74]. The selective localization of dendrimers reduced the chances of off-target systemic and ocular toxicities, whereas the potential toxicity on the target tissues after cell uptake of dendrimer drugs still needs to be considered. Drug loading could also affect the dendrimer surface properties, and high drug loading could shield the hydroxyl-PAMAM dendrimer surface and change the dendrimer drug solubility, both factors that could potentially influence the targeting capability of the dendrimer. Therefore, a balance between the high drug loading and the potential toxicity should be carefully investigated. It still requires further investigation on the long-term safety of the ocular use of dendrimer drugs because PAMAM dendrimers are not biodegradable. Nowadays, many new biodegradable dendrimers have been designed and they could be potentially used for ocular drug delivery with a better safety profile [82,83].

Biodegradable polyesters (e.g., PLGA, PLA) have been depicted as safe polymers for drug delivery. After being injected into the eye, PLGA undergoes degradation and forms biocompatible metabolites (lactic acid and glycolic acid) and eventually gets removed from the body via the Krebs cycle by conversion to carbon dioxide and water [38]. PLGA has been applied to deliver DEX (Ozurdex® implant) for the treatment of DME, noninfectious posterior uveitis and wet AMD [84]. It has been observed that PLGA implant materials at some rare cases could remain after the complete release of drugs in patient eyes [85], which poses the concerns of material build-up, especially for repeated dosing. Many other factors also need to be addressed in detail, including the polymer purity, NP manufacturing technology, solvent residue, potential local acidic environment during polymer degradation, material buildup in the eye after repeated dosing, foreign-body reactions and the potential snow globe effects in the vitreous to disturb the visual axis. Success in the translation of nanomedicine efforts would require a careful risk:benefit analysis, which is often skewed toward risk when it comes to novel therapeutics [86].

Highlights:

Ocular nanomedicine with great clinical translational potential

Nanomedicine can be used for treating anterior and posterior eye diseases

The principles of nanomedicine for targeted and sustained ocular drug delivery

The perspectives of ocular nanomedicine include scale-up manufacturing and safety profiles

Teaser:

Ocular nanomedicine poses a promising therapeutic potential and offers many advantages over conventional ophthalmic medications for effective ocular drug delivery; because nanomedicine can overcome ocular barriers, improve drug-release profiles and reduce potential drug toxicity.

Delivering therapeutics to the eye is challenging on multiple levels: rapid clearance of eyedrops from the ocular surface requires frequent instillation, which is difficult for patients; transport of drugs across the blood–retinal barrier when drugs are administered systemically, and the cornea when drugs are administered topically, is difficult to achieve; limited drug penetration to the back of the eye owing to the cornea, conjunctiva, sclera and vitreous barriers. Nanomedicine offers many advantages over conventional ophthalmic medications for effective ocular drug delivery because nanomedicine can increase the therapeutic index by overcoming ocular barriers, improving drug-release profiles and reducing potential drug toxicity. In this review, we highlight the therapeutic implications of nanomedicine for ocular drug delivery.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01EY027827), FDA (HHSF223201810114C) and the Ralph E. Powe Junior Faculty Award from ORAU.

Biography

Tuo Meng

Tuo Meng is currently a PhD candidate at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, USA. Her research focuses on designing novel drug delivery system for age-related macular degeneration.

Qingguo Xu

Qingguo Xu, DPhil, is an Assistant Professor of Pharmaceutics (primary) and Ophthalmology, at Massey Cancer Center at the Virginia Commonwealth University, USA. Dr Xu has experience in materials science, drug delivery, nanotechnology and physiochemical characterization of mucosal and tissue barriers to drug delivery systems. A significant portion of his current work has involved the design and development of new methods for safe, effective drug delivery to treat ocular disorders.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kels BD et al. (2015) Human ocular anatomy. Clin. Dermatol 33, 140–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonas JB et al. (2008) Short-term complications of intravitreal injections of triamcinolone and bevacizumab. Eye 22, 590–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bochot A and Fattal E (2012) Liposomes for intravitreal drug delivery: a state of the art. J. Control. Release 161, 628–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiang B et al. (2018) The suprachoroidal space as a route of administration to the posterior segment of the eye. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 126, 58–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weng Y et al. (2017) Nanotechnology-based strategies for treatment of ocular disease. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 7, 281–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lalu L et al. (2017) Novel nanosystems for the treatment of ocular inflammation: current paradigms and future research directions. J. Control. Release 268, 19–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez Villanueva J et al. (2016) Dendrimers as a promising tool in ocular therapeutics: latest advances and perspectives. Int. J. Pharm 511, 359–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandal A et al. (2017) Polymeric micelles for ocular drug delivery: from structural frameworks to recent preclinical studies. J. Control. Release 248, 96–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachu RD et al. (2018) Ocular drug delivery barriers – role of nanocarriers in the treatment of anterior segment ocular diseases. Pharmaceutics 10, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lallemand F et al. (2017) Cyclosporine A delivery to the eye: a comprehensive review of academic and industrial efforts. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 117, 14–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelderblom H et al. (2001) Cremophor EL: the drawbacks and advantages of vehicle selection for drug formulation. Eur. J. Cancer 37, 1590–1598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ames P and Galor A (2015) Cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsions for the treatment of dry eye: a review of the clinical evidence. Clin. Invest 5, 267–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boujnah Y et al. (2018) [Prospective, monocentric, uncontrolled study of efficacy, tolerance and adherence of cyclosporin 0.1 % for severe dry eye syndrome]. J. Fr. Ophtalmol 41, 129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandal A et al. (2019) Ocular pharmacokinetics of a topical ophthalmic nanomicellar solution of cyclosporine (Cequa(R)) for dry eye disease. Pharm. Res 36, 36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tauber J et al. (2018) A Phase II/III, randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled, dose-ranging study of the safety and efficacy of OTX-101 in the treatment of dry eye disease. Clin. Ophthalmol 12, 1921–1929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su MY et al. (2011) The effect of decreasing the dosage of cyclosporine A 0.05% on dry eye disease after 1 year of twice-daily therapy. Cornea 30, 1098–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garrigue JS et al. (2017) Relevance of lipid-based products in the management of dry eye disease. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther 33, 647–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan W et al. (2012) Cyclosporin nanosphere formulation for ophthalmic administration. Int. J. Pharm 437, 275–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodges RR and Dartt DA (2013) Tear film mucins: front line defenders of the ocular surface: comparison with airway and gastrointestinal tract mucins. Exp. Eye Res 117, 62–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai SK et al. (2009) Mucus-penetrating nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to mucosal tissues. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 61, 158–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu Q et al. (2013) Scalable method to produce biodegradable nanoparticles that rapidly penetrate human mucus. J. Control. Release 170, 279–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suk JS et al. (2016) PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 99, 28–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang M et al. (2011) Biodegradable nanoparticles composed entirely of safe materials that rapidly penetrate human mucus. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 50, 2597–2600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schopf L et al. (2014) Ocular pharmacokinetics of a novel loteprednol etabonate 0.4% ophthalmic formulation. Ophthalmol. Ther 3, 63–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schopf LR et al. (2015) Topical ocular drug delivery to the back of the eye by mucus-penetrating particles. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol 4, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajasekaran A et al. (2010) A comparative review on conventional and advanced ocular drug delivery formulations. Int. J. Pharm. Tech. Res 2 668–674 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agban Y et al. (2019) Depot formulations to sustain periocular drug delivery to the posterior eye segment. Drug Discov. Today doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang D et al. (2018) Overcoming ocular drug delivery barriers through the use of physical forces. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 126, 96–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leibowitz HM and Kupferman A (1977) Periocular injection of corticosteroids – experimental evaluation of its role in treatment of corneal inflammation. Arch. Ophthalmol 95, 311–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCartney HJ et al. (1965) An autoradiographic study of the penetration of subconjunctivally injected hydrocortisone into the normal and inflamed rabbit eye. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 4, 297–302 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGhee CNJ (1992) Pharmacokinetics of ophthalmic corticosteroids. Br. J. Ophthalmol 76, 681–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malik P et al. (2012) Hydrophilic prodrug approach for reduced pigment binding and enhanced transscleral retinal delivery of celecoxib. Mol. Pharm 9, 605–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.Thakur A et al. (2011) Influence of drug solubility and lipophilicity on transscleral retinal delivery of six corticosteroids. Drug Metab. Dispos 39, 771–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prausnitz MR and Noonan JS (1998) Permeability of cornea, sclera, and conjunctiva: a literature analysis for drug delivery to the eye. J. Pharm. Sci 87, 1479–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weijtens O et al. (1999) High concentration of dexamethasone in aqueous and vitreous after subconjunctival injection. Am. J. Ophthalmol 128, 192–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalina RE (1969) Increased intraocular pressure following subconjunctival corticosteroid administration. Arch. Ophthalmol 81, 788–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guilbert E et al. (2013) Long-term rejection incidence and reversibility after penetrating and lamellar keratoplasty. Am. J. Ophthalmol 155, 560–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SS et al. (2010) Biodegradable implants for sustained drug release in the eye. Pharm. Res 27, 2043–2053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee SS et al. (2007) A pharmacokinetic and safety evaluation of an episcleral cyclosporine implant for potential use in high-risk keratoplasty rejection. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 48, 2023–2029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan Q et al. (2015) Corticosteroid-loaded biodegradable nanoparticles for prevention of corneal allograft rejection in rats. J. Control. Release 201, 32–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Price FW Jr et al. (2009) Survey of steroid usage patterns during and after low-risk penetrating keratoplasty. Cornea 28, 865–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen NX et al. (2007) Long-term topical steroid treatment improves graft survival following normal-risk penetrating keratoplasty. Am. J. Ophthalmol 144, 318–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang B et al. (2019) Controlled release of dexamethasone sodium phosphate with biodegradable nanoparticles for preventing experimental corneal neovascularization. Nanomedicine 17, 119–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo L et al. (2019) Controlled release of corticosteroid with biodegradable nanoparticles for treating experimental autoimmune uveitis. J. Control. Release 296, 68–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Natarajan JV et al. (2012) Nanomedicine for glaucoma: liposomes provide sustained release of latanoprost in the eye. Int. J. Nanomedicine 7, 123–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jayaganesh V et al. (2014) Sustained drug release in nanomedicine: a long-acting nanocarrier-based formulation for glaucoma. ACS Nano 8, 419–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Natarajan JV et al. (2011) Sustained release of an anti-glaucoma drug: demonstration of efficacy of a liposomal formulation in the rabbit eye. PLoS One 6, e24513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eveleth D et al. (2012) A 4-week, dose-ranging study comparing the efficacy, safety and tolerability of latanoprost 75, 100 and 125 μg/ml to latanoprost 50 μg/ml (xalatan) in the treatment of primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. BMC Ophthalmol 12, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong CW et al. (2018) Evaluation of subconjunctival liposomal steroids for the treatment of experimental uveitis. Sci. Rep 8, 6604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Z et al. Activated macrophages induce neovascularization through upregulation of MMP-9 and VEGF in rat corneas. Cornea, 31(2012), pp. 1028–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soiberman U et al. (2017) Subconjunctival injectable dendrimer-dexamethasone gel for the treatment of corneal inflammation. Biomaterials 125, 38–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin H et al. (2018) Subconjunctival dendrimer-drug therapy for the treatment of dry eye in a rabbit model of induced autoimmune dacryoadenitis. Ocul. Surf 16, 415–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sadekar S et al. (2011) Comparative biodistribution of PAMAM dendrimers and HPMA copolymers in ovarian-tumor-bearing mice. Biomacromolecules 12, 88–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Duvvuri S et al. (2003) Drug delivery to the retina: challenges and opportunities. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther 3, 45–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shelke NB et al. (2011) Intravitreal poly(L-lactide) microparticles sustain retinal and choroidal delivery of TG-0054, a hydrophilic drug intended for neovascular diseases. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res 1, 76–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu Q et al. (2013) Nanoparticle diffusion in, and microrheology of, the bovine vitreous ex vivo. J. Control. Release 167, 76–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martens TF et al. (2015) Coating nanocarriers with hyaluronic acid facilitates intravitreal drug delivery for retinal gene therapy. J. Control. Release 202, 83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]