Abstract

Objectives

To identify how social return on investment (SROI) analysis—traditionally used by business consultants—has been interpreted, used and innovated by academics in the health and social care sector and to assess the quality of peer-reviewed SROI studies in this sector.

Design

Systematic review.

Settings

Community and residential settings.

Participants

A wide range of demographic groups and age groups.

Results

The following databases were searched: Web of Science, Scopus, CINAHL, Econlit, Medline, PsychINFO, Embase, Emerald, Social Care Online and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Limited uptake of SROI methodology by academics was found in the health and social care sector. From 868 papers screened, 8 studies met the criteria for inclusion in this systematic review. Study quality was found to be highly variable, ranging from 38% to 90% based on scores from a purpose-designed quality assessment tool. In general, relatively high consistency and clarity was observed in the reporting of the research question, reasons for using this methodology and justifying the need for the study. However, weaknesses were observed in other areas including justifying stakeholders, reporting sample sizes, undertaking sensitivity analysis and reporting unexpected or negative outcomes. Most papers cited links to additional materials to aid in reporting. There was little evidence that academics had innovated or advanced the methodology beyond that outlined in a much-cited SROI guide.

Conclusion

Academics have thus far been slow to adopt SROI methodology in the evaluation of health and social care interventions, and there is little evidence of innovation and development of the methodology. The word count requirements of peer-reviewed journals may make it difficult for authors to be fully transparent about the details of their studies, potentially impacting the quality of reporting in those studies published in these journals.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018080195.

Keywords: health economics, social care, social impact, social return on investment, SROI

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The first systematic review to examine the contribution of academics to social return on investment (SROI) methodology in the context of the health and social care sector.

The study reviewed the use of SROI methodology across a broad range of settings, interventions and participants in the health and social care sector.

A useful quality assessment framework tool for comparing the quality of reporting SROI studies was developed; however, refinement of the tool may be necessary to improve clarity.

The review does not incorporate findings of studies published in the grey literature or non-peer-reviewed journals, and hence cannot comment on the uptake of SROI methodology in health and social care studies more broadly.

Background

Social enterprises offer an alternative model to non-profit organisations whereby market focuses are used to provide public or community benefit. A number of social enterprise organisations operating in the health and social care sectors have seen a growth over the last decade.1–3 This includes developed countries such as the UK and Australia,4 5 as well as developing nations such as Pakistan, Ghana and Vietnam.6–9 The health and social care sector has been estimated to represent 20%–30% of all social enterprise.6–9

The measurement and valuation of outcomes can provide important information for social enterprises’ stakeholders in assessing that funding is maximising social impact.10 Social return on investment (SROI) methodology allows for values to be placed on personal, social and community outcomes which has not hitherto been possible with more established forms of economic evaluation.11 12

With SROI methodology, social value is estimated by the allocation of financial proxy values to outcomes identified in an intervention’s logic model (known as the theory of change). SROI is expressed as a ratio of the adjusted value of benefits divided by total investment. Adjustments to social value are made based on estimations of dead weight (what would have occurred anyway), displacement (what activities were displaced by the intervention), attribution (what other organisations contributed to the outcomes) and drop off (whether the outcomes experienced decline over time). Costs and benefits that occur at different time points are made comparable by adjusting for inflation in order to calculate net present value.12 As an example, an SROI ratio of 4:1 illustrates that, following appropriate adjustments, $4 of social value was created for each dollar invested.

The methodology was initially developed in 2000, and the extant literature acknowledges strengths as well as challenges.3 10 13–17 Strengths include, engagement with stakeholders, the identifying and valuing of outcomes which may be unique but considered valuable to beneficiaries, how the process reinforces mission and can lead to organisational learning and the generation of a simple ratio which is easily comprehended.13 15 17 However, weaknesses at the philosophical, theoretical and practical levels have been noted. Philosophically, the monetisation of outcomes may be at odds with the values of social enterprise organisations and, given the potential high cost of implementing SROI methodology, organisations may find it challenging to justify spending on an SROI study rather than on programme development.2 4 SROI has been noted to lack cohesion from a theoretical perspective. For example, outcomes measurement aligns with a positivist approach but SROI has been noted to privilege stakeholder perspectives over other types of evidence14; such perspectives align better with social constructivist approaches. Practical challenges include the difficulties in valuing ‘soft’ outcomes as well as outcomes experienced at the societal level—particularly, when it comes to addressing ‘wicked problems’ such as societal inequity or disadvantage—the difficulties in identifying the counterfactual (what would have happened anyway), accurately accounting for overheads, and that ratios are highly context specific and cannot be compared.2 10 13–15 17–19 Aggregating outcomes into a single figure has also been as problematic in terms of contract validity and interpretability.18 20

Since its development, SROI methodology has been most commonly implemented by consultants.10 11 16 Consequently, SROI studies are more likely to be reported in the grey literature, if in the public domain at all. This potentially limits learning from previous studies as well as SROI methodological development.10 11 21 Similarly, much of the debate regarding SROI methodology, particularly around many of the practical issues, occurs outside of academia.20 There has been a call for academics to adopt the SROI approach and further develop the methodology,11 13 15 16 as well as a call for greater standardisation.11 13 One associated effect of methodological engagement by academics would be an increase in SROI studies being the subject of peer-review. According to a 2015 systematic review of public health interventions evaluated using SROI methodology, only 10% were published under peer review.15 One common feature of SROI studies to date is that of ‘assurance’; that is, the process by which information reported is verified. This process is usually conducted by an SROI consultant external to the study12 15 and at an additional cost which may be prohibitive for some organisations. With greater academic involvement in SROI, it would be expected that the peer-review process would replace assurance as being a more rigorous means of determining the appropriateness of the analysis and the assumptions on which it is based.

This paper seeks to build on the work of the previous systematic review,15 to examine academic contributions to SROI methodology in studies conducted in the health and social care sector.

The current study

This systematic review identifies (1) the extent to which academics have adopted SROI methodology in evaluating health and social care programme and interventions; (2) how academics have interpreted, used and developed SROI methodology and (3) how academics have reported SROI studies using a quality review designed for the purpose.22

Methods

This review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses guidelines.23 The protocol for this systematic review was registered with PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews and published following peer-review.22

Patient and public involvement

This paper details a systematic review and therefore there was no direct patient or public involvement. However, participants with disability in the broader research project have been involved since the inception and have contributed to the objectives outlined in this systematic review.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This systematic review focused on SROI studies in health and social care settings, including interventions providing treatment for physical or mental health conditions and non-medical interventions to support the social needs of vulnerable populations in a community setting. Any age group or population and all empirical study types were therefore included if this criteria was met. Publications that were not peer-reviewed, conference abstracts, thesis and papers not published in English were excluded.

Search strategy

The keyword search was limited to ‘social return on investment’ and ‘SROI’ to ensure that studies using SROI methodology were identified. Electronic searches were based on full text. Due to there being numerous keyword variations for health and social care, additional keywords were not added but rather all items screened for relevancy.

Searches were limited to papers published after the year 2000 to 1 October 2018. The following multidisciplinary databases were searched: Web of Science, Scopus, CINAHL, Econlit, Medline, PsychINFO, Embase, Emerald, Social Care Online and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Online supplementary appendix I).

bmjopen-2019-029789supp001.pdf (71.7KB, pdf)

Screening and data extraction

Search results were stored in Covidence systematic review software24 and duplicate items removed. Two reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria to reduce the risk of bias. A third reviewer screened all titles and abstracts where there was disagreement between reviewers. Full-text manuscripts were obtained for papers that met the inclusion criteria at initial screening and were again independently reviewed by two reviewers. Following full-text screening, the reference lists of studies shortlisted—plus the reference list of a previous systematic review15—were then hand-searched for additional eligible articles and a citation search was performed on Scopus and Google Scholar.

Data on included studies were extracted on the following categories: author, date of publication, country, intervention, study design, article word count and type of externally referenced results, if applicable. To address the second and third aims of the review, innovations or adaptations to the methodology were also identified and quality assessment scores added (Online supplementary appendix II).

Quality assessment

An SROI-specific quality framework was developed for the purpose of this systematic review, as it was identified that there was no relevant established peer-reviewed quality framework (Online supplementary appendix III). Further details of the quality framework and the processes associated with its development are presented in a separate paper.22

In brief, the quality framework consists of 21 questions in six areas: (1) research question, (2) reason for using SROI, (3) scope, (4) theory of change/impact map, (5) study design and (6) analysis. Each item can be scored according to four categories: yes, no, not clear and not applicable. Data not reported were scored as a ‘no’ and data inadequately reported were scored as ‘not clear’. If an aspect of the quality framework was not relevant to a particular study, it was marked as ‘not applicable’.

Data synthesis

Data were synthesised to address the three stated systematic review objectives. To address objective 1, the number of included studies was compared with the findings of a previous systematic review that included peer-reviewed and grey literature in public health,15 to gain an indication of whether there has been an increase or decrease in SROI studies in recent years. Data to address objective 2 were determined by a review of the adopted methodology compared with that outlined in the SROI Network’s Guide to Social Return on investment.12 This guide has been established in previous reviews as the most extensively cited resource for conducting SROI studies.11 15 Finally, we report findings from our quality review in both table and narrative formats, highlighting key strengths and weaknesses of the included studies. Only the main manuscript and permalink supplementary information were considered to be part of the peer-reviewed content. As expected, meta-analysis was not possible due to the heterogeneous nature of the results; however, we report on identified meta-biases.

Results

Search results

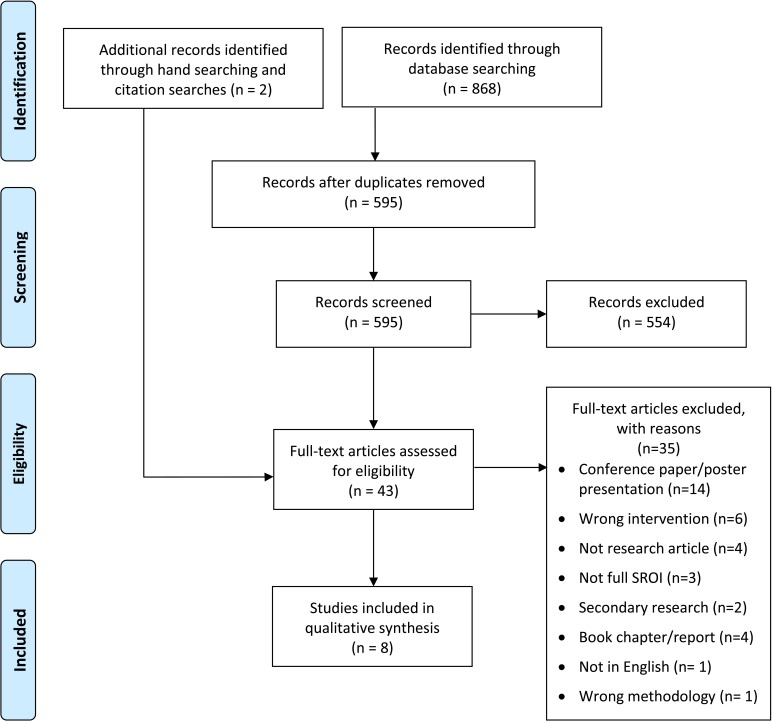

The initial searches returned 868 items, which reduced to 595 items once duplicates were removed (figure 1). Following independent title and abstract screening by two reviewers, a third reviewer screened all titles and abstracts where there was disagreement between reviewers (n=63, 10.6%). Full-text manuscripts were obtained for 41 studies that met the inclusion criteria. The full text of each study was then independently reviewed by two reviewers (CH and DF), resulting in six studies for inclusion. The searching of reference lists from the included studies and a previous systematic review,14 and an associated citation search performed on Scopus and Google Scholar, resulted in the identification of two further studies. The total number of studies included in this systematic review was eight.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses flowchart.

Study characteristics

Of the eight SROI studies, the majority were undertaken in developed nations with half conducted in the UK, two in Canada and one each in the USA and Kenya. One intervention was aimed at children,25 two at pregnant or post-partum women,26 27 two at adults overcoming addiction,28 29 one at adults and families transitioning from homelessness30 and two at older people.31 32 In conducting their analysis, all but one study31 referred extensively to the Guide to SROI.12

Though it was expected that peer-reviewed publications would be authored by academics, one paper was written by a consultant and an organisational representative.28 The remaining papers were published by affiliated academics, though some were published in partnership: academics and consultants,26 and academics and an organisational representative.30 Two papers highlighted that their findings had also been assured by an SROI consultant.25 32

The eight SROI peer-reviewed studies were published relatively recently (between 2011 and 2018) with three of these published in 2015. Thereby indicating that academics have thus far been slow to adopt SROI methodology in the evaluation of health and social care interventions given that the methodology was initially developed in 2000.2

Potentially, due to the limitations imposed by resource constraints, it was observed that data were gathered from a limited number of stakeholder groups in many studies, most commonly intervention beneficiaries, though inclusion of some other groups was noted: families or carers,25 32 volunteers25 26 32 and paid staff.25 30 31 One exception was Goudet et al, whose study included a broad range of stakeholders and a large sample size (over 400) including beneficiaries, different types of family members, healthcare providers and local businesses.27

For studies that included previous beneficiaries of an intervention,25–29 31 32 there was the potential for positive sample bias, as those for whom the intervention was a success may be more willing to participate in an evaluation or may be more likely to be put forward for inclusion by the organisation offering the intervention. Most studies25–28 30 32 collected data at only one time point (retrospectively), which limits our understanding of the impact of the intervention, as opposed to pre–post data collection, for example, and also increases the likelihood of memory bias. There was also a potential positivity bias in the reporting of outcomes, as few studies reported negative outcomes.26 32

Other than focusing on a limited range of stakeholders, another way to reduce scope and therefore costs associated with conducting an SROI analysis is to focus on a limited range of outcomes, and to attribute values based on those identified in the existing literature. Goudet et al was the only study that reported using value games with participants to develop bespoke values for outcomes. Value games are a revealed preference approach whereby participants rank an outcome without a market value with several items that can be purchased. In this way, the value of the outcome can be estimated as somewhere between the value of the items on either side of it in the ranking. Goudet et al identified 34 outcomes, which may have impacted on the final SROI ratios, as the authors reported a significantly higher SROI than all other papers (US$71 social return for every US$1 invested).27 Other papers reported between 2 outcomes30 and 10 outcomes,28 and SROI ratios were between 1.17:132 and 6.09:1.28 Notably, there was no evidence that authors had used SROI value banks such as HACT33 or Global Value Exchange34 in identifying suitable financial proxies.

Although it was expected that the adoption of SROI methodology by academics may lead to innovation and development of the methodology,13 15 there was little evidence of this. However, some relatively minor adaptations or additions were made (Online supplementary appendix II). For example, Iafrati attempted to overcome positive sampling bias by weighting outcome values at 65%; this estimate equating to the centre’s overall reported success rate at helping people overcome addiction during the relevant time period.29 Furthermore, the analysis for this study adopted a sociopolitical approach which focused on monetary savings at the societal level rather than personal outcomes. This approach was adopted in recognition that, under the prevailing neo-liberalism ideology in the UK, funding interventions aimed at those considered by society to be less ‘deserving’ may make it challenging to attract ongoing funding unless a convincing case can be made for a reduction in welfare and other types of government spending (eg, court costs, doctor and emergency room visits).

The inputs for SROI for beneficiaries is rarely calculated in SROI studies. However, Kennedy and Philips added beneficiaries’ travel expenses to intervention inputs in recognition of the financial contributions beneficiaries made towards their own recovery.28 Scharlach went a step further, calculating the social return for beneficiaries based on their membership fees to a volunteer-assisted service for vulnerable, predominantly low-income, community-dwelling older people.31 In another minor adaption for an SROI based on three interventions by different organisations to support people with dementia, Willis et al calculated weightings for all financial proxies to address differences in the frequency and duration of support across the intervention groups.32

Quality assessment

The quality assessment focused on the quality of reporting and was undertaken independently by two reviewers (CH and DF). The degree of inter-rater reliability was measured using Cohen’s Kappa, which considers the role of chance in inter-rater agreement.35 The degree of agreement between the two reviewers was calculated before and after discussion. Kappa prior to discussion scored 0.557 (moderate agreement), while following discussion substantial agreement was reached (0.738). Any item with remaining disagreement between raters following discussion was scored as ‘not clear’. As not all items in the quality assessment were relevant for each paper, quality scores are also reported as a percentage. The overall quality ratings of the studies ranged from 38% to 90% with a mean of 65%.

In overview, papers were strong in several areas, including, posing a well-defined research question (all), their reason for using SROI (all), providing relevant background literature to justify their study (all), selecting an appropriate study design (7), clearly valuing inputs (7) and reporting limitations and biases (7). There was more variation, and most studies were poorer, at justifying the range of stakeholders included (4), justifying their sample sizes (3) (or clearly reporting sample sizes) and reporting whether informed consent was obtained (3). Furthermore, there was a strong bias towards positive outcomes with negative or unintended outcomes rarely reported (2). Only two papers reported the details of their sensitivity analysis.27 30 An additional paper reported that they had conducted sensitivity analysis but reported no details other than that ‘the SROI ratio did not change substantially’ (Kennedy, p 18).28 The lack of sensitivity analysis raises the likelihood of bias in the final reported SROI ratio as the impact of various assumptions on the SROI estimate throughout a study is unknown.

There was an issue with scoring some of the quality framework criteria, as some criteria had two aspects and one might be met but not the other (eg, a study may have listed the range of stakeholders included but not justified why certain stakeholders were included and others excluded). In the review, both aspects of the criteria had to be met before a point was awarded. Unlike in the grey literature where the majority of SROI studies are published,11 word count limitations are a reality of academic publishing. The included papers varied from approximately 2900 words,25 to approximately 7500 words.27 However, we identified no relationship between word count and quality ratings (Online supplementary appendix II).

Discussion

Our study closely followed the associated published systematic review protocol.19 Overall, it was found that there has been little uptake of SROI methodology by academics in the health and social care sector to date. Predominantly, academics, like SROI consultants and organisations, have used the existing and well-established guide to SROI methodology by Nicholls et al as a framework for conducting their studies.12 There has been little evidence of academics developing the SROI methodology with only a range of small adaptations or additions to the usual methodology. Perhaps, due to budgetary constraints/limited resources available to conduct SROI studies, the majority used financial proxies identified from the existing literature. Though there have been considerable efforts by SROI practitioners to collate social value banks such as HACT33 and Global Value Exchange,34 these studies did not access these resources. Only one study conducted value games in order to derive financial proxies that considered the values of stakeholders.27 However, given that this study was the only eligible study conducted in a developing country, existing financial proxies from developed countries would likely be less relevant and appropriate in this context, necessitating this additional work to develop bespoke financial proxies.

As academics have only recently started to use SROI methodology, there was only a relatively small number of qualifying studies included in this systematic review. As such, it is perhaps too early to be determining the extent to which SROI methodology has been adopted by academics working in health and social care. This review included only peer-reviewed papers due to the focus on academic contribution to the methodology, so we were not able to determine the proportion of SROI studies in health and social care that were peer-reviewed rather than published as grey literature. However, we note that other authors have identified peer-reviewed SROI studies to be between 1% of all SROI studies11 and 10% of those in public health.15 There may be other sectors in which academics have been earlier adopters of this methodology but, perhaps due to concerns about the value and relevancy of SROI methodology, which can be highly context-specific,15 health and social care academics has been slow to adopt this as part of their toolkit for developing an evaluation evidence base.

The quality assessment framework developed for the assessment of SROI studies was a useful tool for comparing the quality of reporting among studies.22 However, our study suggested that further refinement may be necessary. In particular, some items may need to be broken down into two items or half points awarded (eg, ‘were the proxies valid and comprehensive?’, ‘was the sample described in detail/was the sample justified?’). Overall, we observed a number of positivity biases in the studies, relating to sampling and the outcomes that were included in SROI calculations. Few studies noted negative outcomes as the result of the interventions under study, or even unexpected outcomes, whether positive or negative. Furthermore, few studies reported having undertaken sensitivity analysis and therefore this decreases confidence in the SROI ratios presented.

Common weaknesses in reporting (eg, justifying stakeholder scope, reporting sample sizes and whether consent had been obtained) related to papers of different word counts. Weaknesses in reporting clarity therefore did not seem to relate to word count limitations with some shorter papers scoring higher than more lengthy ones. Given that most papers cited supplementary materials, appendices and external links, it seems that full transparency of how SROI was conducted is challenging to achieve within peer-reviewed journals’ word count limits, though clarity for readers is likely improved by the more detailed components of the analysis not being included in the main text. It may be that the positivist evidence hierarchies of academia do not align with SROI methodology in which personal experiences and outcomes are privileged.13 However, if SROI methodology becomes as accepted in other countries as it has been in the UK by government and policy-making bodies,11 this may drive wider take-up and adoption of SROI methodology by academics and other stakeholders in Australia and elsewhere.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CH, AB and JR conceived the study and were responsible for the design and search strategy, which was approved by SGH and SG. DF was responsible for conducting the search. CH, DF and SGH conducted the screening. CH and DF extracted the data, conducted the data analysis and quality assessment. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by CH and DF and then circulated to all authors for critical revision. All authors approved the final draft for submission.

Funding: This study was funded by Lifetime Support Authority (grant number: GA00040).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Department of Health Measuring social value - how five social enterprises did it. London: The Stationery Office, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Millar R, Hall K. Social return on investment (SROI) and performance measurement: the opportunities and barriers for social enterprises in health and social care. Public Management Review 2013;15:923–41. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roy MJ, Donaldson C, Baker R, et al. Social enterprise: new pathways to health and well-being? J Public Health Policy 2013;34:55–68. 10.1057/jphp.2012.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miller R, Hall K, Millar R. Right to Request social enterprises: a welcome addition to third sector delivery of English healthcare? Voluntary Sector Review 2012;3:275–85. 10.1332/204080512X649414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. UK Government, Media and Sport, and Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy . Social enterprise: market trends 2017. London: department for digital. Culture 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Australia Government, Research and Tertiary Education, Canberra: department of industry innovation . Australian innovation system report: chapter 5: public sector and social innovation. Sciences 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barraket J, Collyer N, O’Connor M. Finding Australia’s social enterprise sector. Report for the Australian Centre for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Studies, Social Traders, Melbourne 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8. British Council Social enterprise in Vietnam: concept, context and policies, 2012. Available: https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/vietnam_report.pdf

- 9. British Council The state of social enterprise in Bangladesh, Ghana, India and Pakistan, 2016. Available: https://www.britishcouncil.org/society/social-enterprise/news-events/reports-survey-social-enterprise-BGD-GHA-IND-PAK2016

- 10. Moody M, Littlepage L, Paydar N. Measuring social return on investment: lessons from organisational implementation of SROI in the Netherlands and the United States. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 2015;26:19–37. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krlev G, Münscher R, Mülbert K. Social return on investment (SROI): state-of-the-art and perspectives-a meta-analysis of practice in social return on investment (SROI) studies published 2013:2002–12.

- 12. Nicholls J, Lawlor E, Neitzert E, et al. A guide to social return on investment. The office of the third sector (OTS): government of Scotland, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arvidson M, Lyon F, McKay S, et al. The ambitions and challenges of SROI. Birmingham: TSRC, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arvidson M, Lyon F. Social impact measurement and non-profit organisations: compliance, resistance, and promotion. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 2014;25:869–86. 10.1007/s11266-013-9373-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Banke-Thomas AO, Madaj B, Charles A, et al. Social return on investment (SROI) methodology to account for value for money of public health interventions: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2015;15:582 10.1186/s12889-015-1935-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mulgan G, value Msocial. Stanford social innovation review 2010;8:38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pathak P, Dattani P. Social return on investment: three technical challenges. Social Enterprise Journal 2014;10:91–104. 10.1108/SEJ-06-2012-0019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gibbon J, Dey C. Developments in social impact measurement in the third sector: scaling up or Dumbing down? Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 2011;31:63–72. 10.1080/0969160X.2011.556399 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Farr M, Cressey P. The social impact of advice during disability welfare reform: from social return on investment to evidencing public value through realism and complexity. Public Management Review 2019;21:238–63. 10.1080/14719037.2018.1473474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fujiwara D. The seven principle problems of SROI. London: Simetrica Ltd, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Social ventures Australia consulting. social return on investment: lessons learned in Australia, 2012.

- 22. Hutchinson CL, Berndt A, Gilbert-Hunt S, et al. Valuing the impact of health and social care programmes using social return on investment analysis: how have academics advanced the methodology? A protocol for a systematic review of peer-reviewed literature. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022534 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Covidence systematic review software, veritas health innovation. Melbourne, Australia. Available: www.covidence.org

- 25. Laing CM, Moules NJ. Social return on investment: a new approach to understanding and Advocating for value in healthcare. Jona: The Journal of Nursing Administration 2017;47:623–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arvidson M, Battye F, Salisbury D. The social return on investment in community befriending. International Journal of Public Sector Management 2014;27:225–40. 10.1108/IJPSM-03-2013-0045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goudet S, Griffiths PL, Wainaina CW, et al. Social value of a nutritional counselling and support program for breastfeeding in urban poor settings, Nairobi. BMC Public Health 2018;18 10.1186/s12889-018-5334-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kennedy R, Phillips J. Social return on investment (SROI): a case study with an expert patient programme. SelfCare 2011;2:10–20. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Iafrati S. The investment and regenerative value of addiction treatment. Drugs and Alcohol Today 2015;15:12–20. 10.1108/DAT-10-2014-0037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mook L, Chan A, Kershaw D. Measuring social enterprise value creation. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 2015;26:189–207. 10.1002/nml.21185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Scharlach AE. Estimating the value of Volunteer-Assisted community-based aging services: a case example. Home Health Care Serv Q 2015;34:46–65. 10.1080/01621424.2014.999902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Willis E, Semple AC, de Waal H. Quantifying the benefits of peer support for people with dementia: a social return on investment (SROI) study. Dementia 2016;1471301216640184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. HACT social value bank. London. Available: https://www.hact.org.uk/social-value-bank

- 34. Global Value Exchange Liverpool: social value UK. Available: http://www.globalvaluexchange.org/

- 35. Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull 1968;70:213 10.1037/h0026256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029789supp001.pdf (71.7KB, pdf)