Abstract

Combining two known antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) into a hybrid peptide is one promising avenue in the design of agents with increased antibacterial activity. However, very few previous studies have considered the effect of creating a hybrid from one AMP that permeabilizes membranes and another AMP that acts intracellularly after translocating across the membrane. Moreover, very few studies have systematically evaluated the order of parent peptides or the presence of linkers in the design of hybrid AMPs. Here, we use a combination of antibacterial measurements, cellular assays and semi-quantitative confocal microscopy to characterize the activity and mechanism for a library of sixteen hybrid peptides. These hybrids consist of permutations of two primarily membrane translocating peptides, buforin II and DesHDAP1, and two primarily membrane permeabilizing peptides, magainin 2 and parasin. For all hybrids, the permeabilizing peptide appeared to dominate the mechanism, with hybrids primarily killing bacteria through membrane permeabilization. We also observed increased hybrid activity when the permeabilizing parent peptide was placed at the N-terminus. Activity data also highlighted the potential value of considering AMP cocktails in addition to hybrid peptides. Together, these observations will guide future design efforts aiming to design more active hybrid AMPs.

Keywords: antimicrobial peptide, hybrid peptide, peptide design, membrane translocation, membrane permeabilization

1. Introduction

In the face of increasing resistance to conventional therapeutics, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are frequently considered as potential candidates for new antibiotics. AMPs are part of the innate immune response of all classes of life, and in addition to killing bacteria can have antiviral and antifungal activity [1-3]. Some AMPs, such as parasin [4] and magainin 2 [5], kill bacteria by inducing membrane permeabilization. Other AMPs, such as buforin II (BF2) [6, 7] and DesHDAP1 [8], are able to translocate across the membrane without causing significant disruption and appear to act through interactions with intracellular components, such as nucleic acids.

One strategy to design novel AMPs with enhanced potency and function is to combine two antimicrobial peptides into a single hybrid (or chimeric) AMP. One of the first examples of this strategy was the hybridization of the AMPs cecropin A and melittin to form a single hybrid peptide that was more potent than either cecropin A or melittin against certain bacterial strains, including MRSA [9-11]. Other hybrids have been subsequently designed from a wide range of AMPs including lactoferricins [12-17], microcins [18], human defensins [19-21], cecropin A or B with LL-37 with cecropin A or PI [22, 23], LL-37 with rat neutrophil peptide-1 [23], magainin or thanatin [11, 24-26] and ATCUN domains with a variety of peptides [27, 28]. Other studies have considered the effect of grafting other active domains, such as a bacteriocins [29], salivary histatins [30, 31], uperin 3.6 [32], HP [16, 33], indolicidin with LL-37 or ranalexin [23, 34].

While many studies have shown that hybridizing two AMPs often results in a peptide that is more potent than either of the “parent” peptides, few studies have systematically considered whether these hybrid peptides are more potent than a non-hybridized mix of the two parent peptide molecules. Considering this is critical because the same molar concentration of a hybrid peptide contains roughly twice the concentration of individual amino acids as a single “normal” peptide. Moreover, this is a particularly relevant question since it is typically more expensive to synthesize one longer hybrid peptide than two shorter ones. Similarly, studies often do not systematically investigate the effect of reversing the order of peptides in hybrids or including linkers between the two peptides, making it difficult to formulate generalizable principles for peptide design. This is important, as these factors can influence hybrid activity or mechanism of action [35].

Most importantly, the vast majority of studies of hybrid peptides have focused on combining two membrane permeabilizing peptides. Few studies have investigated the effect of combining one AMP that permeabilizes membranes and one AMP that translocates across the membrane to target intracellular components. The closest studies to addressing this question include an investigation into the mechanism of action and activity of hybrid peptides against Candida that combined the permeabilizing peptide, Halocidin, with the translocating peptide, Histatin 5 [30]. Another study involved a “triple-hybrid” LHP7 made from a combination of peptides that induce membrane permeabilization and target lipid II (plectasin) [16]. Additionally, Wammakok et al. combined Histatin 5 with a truncated version of the permeabilizing peptide LL-37 but did not consider the mechanism of action of the hybrid peptides [31].

Here, we aim to address these questions by characterizing a library of sixteen hybrid antimicrobial peptides that combine one AMP that causes significant membrane permeabilization (parasin or magainin 2) with one that does not (DesHDAP1 or BF2) (Tables 1 and 2). We designed this library to systematically investigate the effect of combining different peptides, placing the permeabilizing peptide at the N- versus C-terminus, and adding an alanine spacer between the sequences of the two parent peptides. Exploring these permutations is important given the known effect of cleavages and mutations near the termini of some of these peptides. For example, parasin is sensitive to mutations and cleavages near its N-terminus [4], while BF2 is more sensitive to cleavages near its C-terminus [7]. Interestingly, many previous investigations of magainin 2 hybrids with cecropin A, papiliocin and LL37 have only included an N-terminal region of the peptide [24, 26, 36]. While these studies generally did not explore altering the order of peptides in the hybrid sequence, different activities were observed when a portion of magainin 2 was N-terminal vs. C-terminal to LL37, although those effects differed between bacterial strains [24].

Table 1:

Parent peptides used for hybrid peptide design

| Peptide | Sequence | Primary cellular localization pattern |

|---|---|---|

| buforin II (BF2) | TRSSRAGLQWPVGRVHRLLRK | membrane translocation |

| DesHDAP1 | ARDNKKTRIWPRHLQLAVRN | membrane translocation |

| parasin | KGRGKQGGKVRWKAKTRSS | membrane localization/permeabilization |

| magainin 2 | GIGKWLHSAKKFGKAFVGEIMNS | membrane localization/permeabilization |

Table 2:

Hybrid peptides designed and characterized. The sequences of the primarily permeabilizing parent peptide are shown in bold. Hybrids with an alanine linker between the two parent peptides are denoted with an A in their name with the linker underlined.

| Peptide | |

|---|---|

| BF2-parasin (B-P) | TRSSRAGLQWPVGRVHRLLRKKGRGKQGGKVRWKAKTRSS |

| BF2-A-parasin (B-A-P) | TRSSRAGLQWPVGRVHRLLRKAKGRGKQGGKVRWKAKTRSS |

| parasin-BF2 (P-B) | KGRGKQGGKVRWKAKTRSSTRSSRAGLQWPVGRVHRLLRK |

| parasin-A-BF2 (P-A-B) | KGRGKQGGKVRWKAKTRSSATRSSRAGLQWPVGRVHRLLRK |

| BF2-magainin (B-M) | TRSSRAGLQWPVGRVHRLLRKGIGKWLHSAKKFGKAFVGE |

| BF2-A-magainin (B-A-M) | TRSSRAGLQWPVGRVHRLLRKAGGIGKWLHSAKKFGKAFVGEIMNS |

| magainin 2-BF2 (M-B) | GIGKWLHSAKKFGKAFVGEIMNSTRSSRAGLQWPVGRVHRLLRK |

| magainin 2-A-BF2 (M-A-B) | GIGKWLHSAKKFGKAFVGEIMNSATRSSRAGLQWPVGRVHRLLRK |

| DesHDAP1-parasin (D-P) | ARDNKKTRIWPRHLQLAVRNKGRGKQGGKVRWKAKTRSS |

| DesHDAP1-A-parasin (D-A-P) | ARDNKKTRIWPRHLQLAVRNAKGRGKQGGKVRWKAKTRSS |

| parasin-DesHDAP1 (P-D) | KGRGKQGGKVRWKAKTRSSARDNKKTRIWPRHLQLAVRN |

| parasin-A-DesHDAP1 (P-A-D) | KGRGKQGGKVRWKAKTRSSAARDNKKTRIWPRHLQLAVRN |

| DesHDAP1-magainin 2 (D-M) | ARDNKKTRIWPRHLQLAVRNGIGKWLHSAKKFGKAFVGEIMNS |

| DesHDAP1-A-magainin 2 (D-A-M) | ARDNKKTRIWPRHLQLAVRNAGIGKWLHSAKKFGKAFVGEIMNS |

| magainin 2-DesHDAP1 (M-D) | GIGKWLHSAKKFGKAFVGEIMNSARDNKKTRIWPRHLQLAVRN |

| magainin 2-A-DesHDAP1 (M-A-D) | GIGKWLHSAKKFGKAFVGEIMNSAARDNKKTRIWPRHLQLAVRN |

Through a combination of cellular assays and semi-quantitative confocal microscopy we determined that our hybrid peptides primarily kill bacteria via membrane permeabilization. We also demonstrate that placing the permeabilizing parent at the N-terminus of a hybrid sequence maximized activity, and we describe other trends in hybrid activity that will be useful in future AMP design efforts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Peptide design and synthesis

The sequences of the peptides used in this study are shown in Table 2. Hybrids were designed by combining one permeabilizing parent peptide (parasin or magainin 2) with one translocating parent peptide (DesHDAP1 or BF2). The parent peptides were combined in different orientations (i.e. with the permeabilizing peptide at the N-terminus and the translocation peptide at the C-terminus, and vice versa). Additionally, a single alanine spacer was inserted between the sequence of each of the two parent peptides to change the relative position of each amino acid residue in the alpha helix thereby altering the amphipathic face of the peptide. The peptides were synthesized from NeoBioSci (Cambridge, MA) or GenScript (Piscataway, NJ) at >95% purity. Magainin 2 and parasin and their hybrid analogs contained a F5W and A12W mutation, respectively, to allow for spectroscopic protein concentration measurements.

2.2. Bacterial preparation

Top10 E. coli (Invitrogen) containing a plasmid for ampicillin resistance were used in all experiments. For propidium iodide and radial diffusion assays, an overnight culture was diluted 1:100 in 25mL of 3% trypticase soy broth (TSB) and incubated in the presence 25μg/mL ampicillin at 37°C with shaking for 2.5 hours. The culture was pelleted via centrifugation at 1500 × g (radial diffusion assay) or 880 × g (propidium iodide) for 10 minutes at 4°C, rinsed in 10mL of wash buffer (10mM sodium phosphate buffer + 10mM sodium chloride (pH=7.4)) and repelleted and re-suspended in wash buffer.

2.3. Propidium iodide (PI) uptake assay

The PI uptake assay was used to determine the relative degree of membrane permeabilization of each peptide. 3mL of bacteria (1.25 × 108 CFU/mL) was suspended in 10mL of wash buffer (10mM sodium phosphate buffer + 10mM sodium chloride (pH=7.4)) in a quartz cuvette, and PI was added to a concentration of 1mg/mL in solution. The solution equilibrated for roughly five minutes before peptide was added at a concentration of 2μM in solution. The fluorescence intensity of the solution was measured before and after the addition of the peptide using a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer (excitation wavelength: 535 nm; emission wavelength: 617 nm). The degree of membrane permeabilization was calculated using the following equation:

Each peptide was tested from ≥3 independent replicates using bacteria grown from distinct overnight cultures.

2.4. Radial diffusion assay

The radial diffusion assay was used to determine the relative potency of each peptide. 10mL of molten underlay (1% TSB, 1% agarose w/v, 10mM Sodium Phosphate Buffer +10mM Sodium Chloride, pH=7.4) was inoculated with 4 × 106 CFU of bacteria suspended in 10mL of 10mM Sodium Phosphate Buffer +10mM Sodium Chloride, pH=7.4 and poured into a sterile petri dish. After the agar solidified, wells ~1.5mm in diameter were formed in the agar using a glass Pasteur pipette attached to a bleach trap. Each well was filled with 1μL of peptide (100μM). The plate was incubated upside down for 3 hours at 37 °C after which the plate was covered with 10mL of molten overlay (6% w/v TSB, 1% w/v agarose) and incubated upside down overnight. The next day (18-24 hours), the diameter of bacterial clearance was measured.

2.5. Spheroplast preparation and imaging

Spheroplasts were prepared as described in [37]. 5μL of spheroplasts were pipetted on a poly-L-lysine coated glass slide and incubated with 2μL of 100μM FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate)-labeled peptide and 1μL of 0.03mM di-8-ANEPPS for 3 minutes. Di-8-ANEPPS is a member of the family of ANEP (aminonaphthylethenylpyridinium) dyes originally developed as membrane potential probes that can also be used to label the location of membranes. Spheroplasts were visualized using a Leica TCS SP5 II laser scanning confocal microscope with excitation at 488 nm by an argon laser at 20% power output, 20% transmission, and emission ranges of 499-532 nm (FITC-labeled peptide) and 670-745 nm (di-8-ANEPPS). 8-bit, 512×512 images were collected at 63× magnification (Leica Plan-Apochromat oil objective; numerical aperture 1.40). Composite z-stack images of 0.5μm thick slices were produced by Leica LAS AF software (Buffalo Grove, IL). Circular Regions of Interest (ROI) 0.3μm in diameter were drawn on the membrane (ROI 1), intracellular space (ROI 2), and background (ROI 3), and the fluorescence intensity of peptide was quantified in each ROI. The ratio of intracellular peptide fluorescence intensity to membrane peptide fluorescence intensity was calculated using the following equation:

Peptide localization was defined as translocating or membrane localizing when the ratio was ≥1 and <1, respectively.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Hybrids made from parent peptides with different mechanisms of action have antimicrobial activity

All hybrids designed for this study (Table 2) were made by combining one AMP that primarily kills cells via translocation with one AMP that primarily kills cells via membrane permeabilization. Thus, our initial question was whether hybrids designed in this way would retain any antimicrobial activity or whether the two peptides would lose their activity in this combination. Notably, all sixteen hybrids considered did show measurable activity against E. coli.

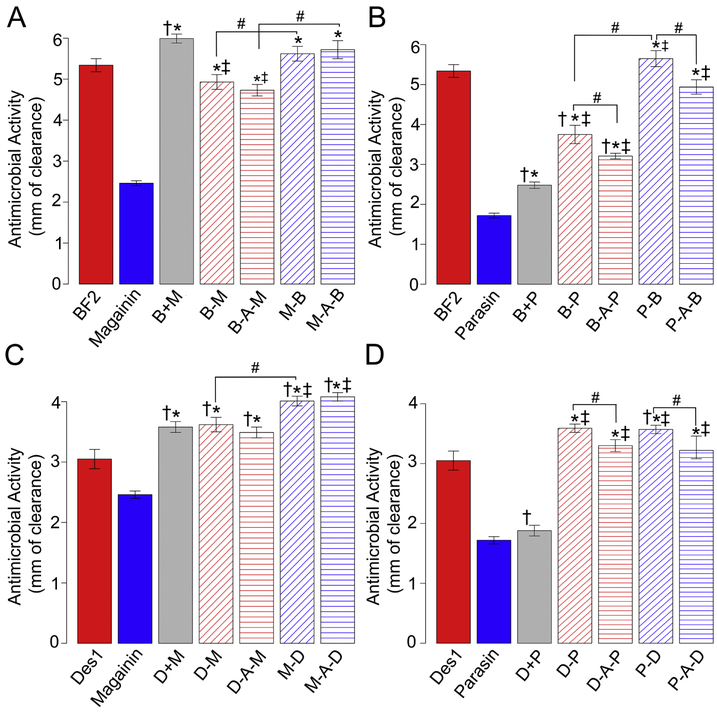

However, one can also compare the activity of a hybrid that covalently links two AMPs together through a peptide bond to the activity of a peptide “cocktail” that combines equal molar mixtures of two peptides. The activity of cocktails made from the translocating/permeabilizing peptide combinations used for hybrids are shown with + signs in Fig. 1. Interestingly, parasin seemed to have a much larger effect when used as a hybrid partner as opposed to in a cocktail (Fig. 1B and 1D), while magainin 2 was often at least as effective in cocktails (Fig. 1A and 1C). This trend seemed to depend only on the permeabilizing partner and not the translocating partner, as the same trends were seen when magainin 2 or parasin were mixed with either BF2 or DesHDAP1. This dependence on the identity of the permeabilizing partner could relate to the overall mechanism of the hybrid peptides, as discussed in the next section.

Figure 1:

Antimicrobial activity of peptides against E. coli measured by radial diffusion assays. Hybrids were made from combining BF2 and magainin 2 (A), BF2 and parasin (B), DesHDAP1 and magainin 2 (C) or DesHDAP1 and parasin (D). Parent peptides are colored based on their primary mechanism of action; red for translocating and blue for membrane permeabilizing. Hybrid peptides are given the color of the more N-terminal peptide in the sequence. Data for an equimolar mixture of the two peptides (not in a covalently-linked hybrid) are denoted with a +. A minimum of 12 readings from at least 3 individual cultures were taken for each peptide. Symbols above bars indicate statistical significance (t-test, p<0.05) from the translocating parent (†), permeabilizing parent (*), equimolar mixture (‡), or the indicated peptide pair (#). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

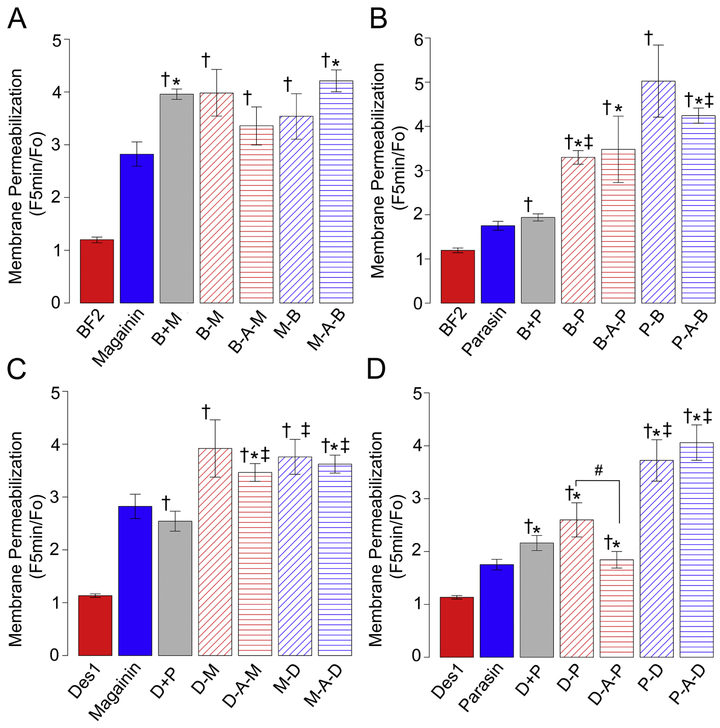

3.2. Hybrids have enhanced membrane permeabilization and reduced translocation relative to parent peptides

Since all hybrids showed antibacterial activity (Fig. 1) we considered whether all hybrids shared the same mechanism of action. To begin investigating this question, we initially measured the ability of the hybrid peptides to induce membrane permeabilization using a bacterial assay with propidium iodide (PI). PI has significantly increased fluorescence when it is able to bind intracellular nucleic acids, which can only occur if the cell membrane has been compromised. The average fluorescence increase five minutes after exposure to antimicrobial peptides is shown in Fig. 2, and representative traces for each hybrid are given in Fig. S1-S4. Strikingly, all hybrid peptides appear to induce permeabilization significantly more than their translocating parent peptide, and many induce significantly more than their permeabilizing parent peptide.

Figure 2:

Membrane permeabilization of peptides with E. coli measured by the propidium iodide (PI) assay. Permeabilization is shown as the average ratio of PI fluorescence 5 minutes after addition of peptides to cells (F5min) relative to initial fluorescence (Fo). Data is shown for hybrids made from combining BF2 and magainin 2 (A), BF2 and parasin (B), DesHDAP1 and magainin 2 (C) or DesHDAP1 and parasin (D). A minimum of 3 individual samples were measured for each average other than magainin+BF2 (n=2). Colors are as in Figure 1. Symbols above bars indicate statistical significance (t-test, p<0.05) from the translocating parent (†), permeabilizing parent (*), equimolar mixture (‡), or the indicated peptide pair (#). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

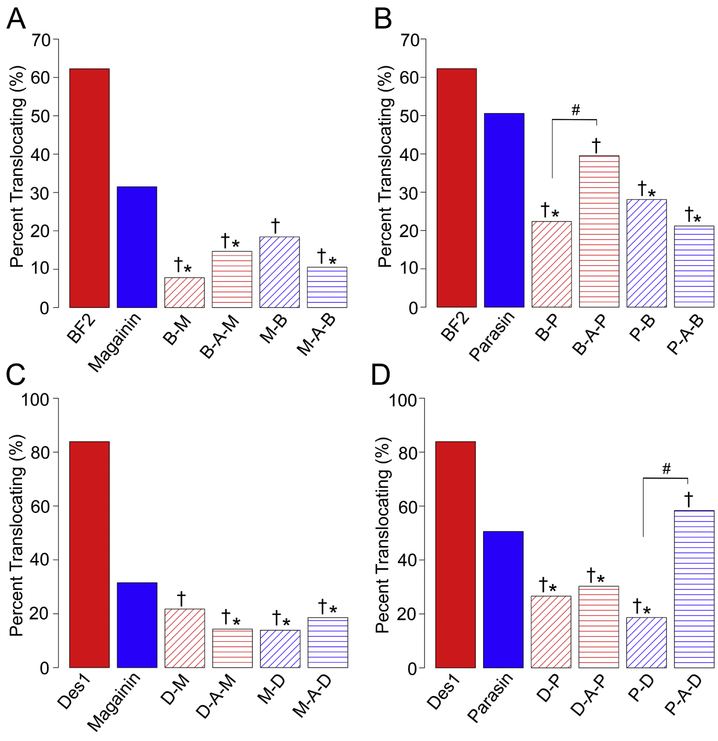

We further examined the cellular localization of hybrid peptides using confocal microscopy. In order to ensure sufficient resolution to accurately determine whether peptides were localized only to the membrane or primarily to the inside of cells, images were taken using bacterial spheroplasts following our previously described approach [37]. It is important to note that this translocation data was collected on a version of E. coli cells that has a modified membrane structure. We decided to image spheroplasts in order to overcome optical resolution issues that can make it difficult to distinguish bona fide peptide translocation when using normal bacteria. The use of spheroplasts also allows for the collection of a much larger datasets of images, allowing for more systematic comparisons. Although one should be cautious in extrapolating this data to normal cells, our previous work has shown similar translocation trends for several peptides in E. coli and spheroplasts, including for buforin II and magainin 2 [37, 38].

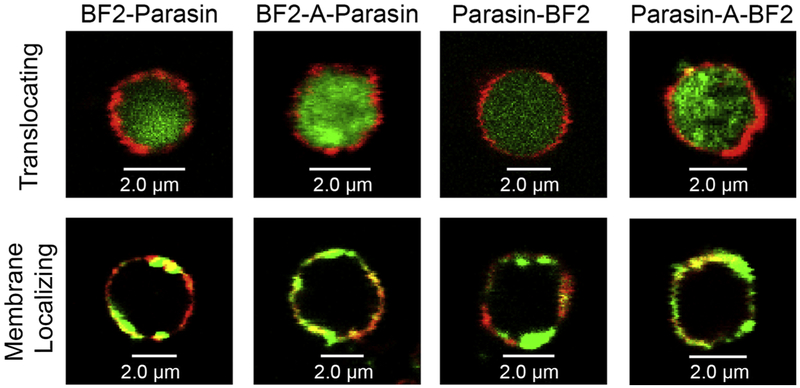

Using spheroplasts we imaged at least 69 cells for each hybrid peptide from at least 3 separate spheroplast preparations. For each image, a full z-stack was collected, and the image representing the central slice of the cell was used for analysis. The percent of spheroplast cells showing translocation for each hybrid is shown in Fig. 3, and images from one set of hybrids showing examples of both translocation and membrane localization in spheroplasts are provided in Fig. 4. With few exceptions, all hybrids showed significantly less translocation than either of the parent peptides, and no peptides showed translocation greater than the less translocating (more permeabilizing) parent peptide (Fig. 3).

Figure 3:

Cellular localization of peptides in E. coli spheroplasts measured by confocal microscopy. Data are shown as percentage of spheroplasts with internal peptide localization, or translocation into the spheroplasts. A minimum of 69 spheroplasts were visualized for each peptide. Data are shown for hybrids made from combining BF2 and magainin 2 (A), BF2 and parasin (B), DesHDAP1 and magainin 2 (C) or DesHDAP1 and parasin (D). Colors are as in Figure 1. Symbols above bars indicate statistical significance (chi-square test, p<0.05) from the translocating parent (†) or permeabilizing parent (*).

Figure 4:

Representative images of E. coli spheroplasts labeled with the membrane marker di-8-ANEPSS (red) interacting with FITC labeled BF2, Parasin, or hybrid analogs (green). Images are the middle z-stack of the cell shown at 63x magnification. Examples of a spheroplast showing both membrane translocation and membrane localizing are shown for each hybrid,

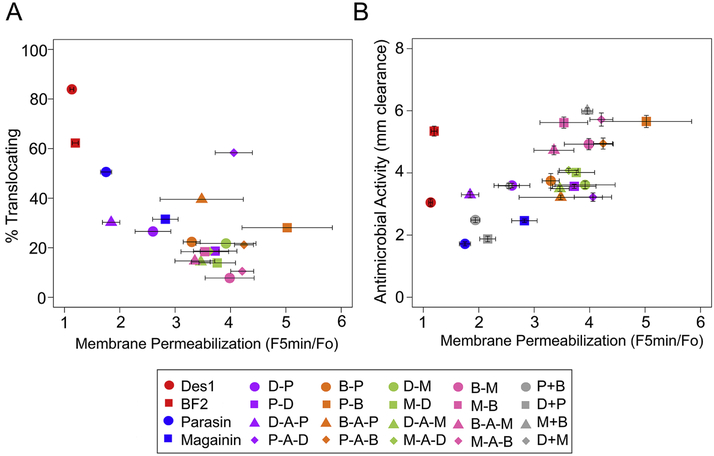

In considering these two sets of experiments together, our library of peptides showed a fairly consistent inverse relationship between the membrane permeabilization induced by a hybrid peptide and its ability to translocate into spheroplasts (Fig. 5A). This data supports the idea that a particular peptide likely functions via some combination of cell entry and membrane permeabilization when encountering bacteria [38-41], with peptides that induce more permeabilization having less translocation into cells and vice versa. Notably, even our parent peptides can be viewed on a spectrum between purely translocating and purely permeabilizing, In particular, in our measurements the parasin peptide used as a “permeabilizing” parent showed behavior somewhat between the more permeabilizing parent peptide magainin 2 and the more translocating peptides BF2 and DesHDAP1.

Figure 5.

Relationship between membrane permeabilization of AMPs and antimicrobial activity (A) or membrane translocation (B). Membrane permeabilization was measured as the average relative fluorescence increase of propidium iodide five minutes after peptide addition to an E. coli culture (A and B). Membrane translocation is shown as the average percentage of E. coli spheroplasts to show peptide entry in confocal microscopy measurements (A). Antibacterial activity was measured against E. coli using a radial diffusion assay (B). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Analysis of our library also showed the more permeabilizing peptide dominating the overall mechanism of hybrid peptides. This trend appears regardless of the relative order of peptides in the hybrid or the presence of a linker between the peptides. A similar observation arose in our previous analysis of hipposin, a naturally occurring AMP that included the sequences of parasin and BF2 [42]. As well, the LHP7 triple hybrid consisting of permeabilizing and lipid II binding peptides also mediated membrane disruption [16]. We hypothesize that this overall trend arises because the ability of a peptide to effectively translocate into a cell without causing significant membrane permeabilization requires specific structural features. This has been observed in studies showing that single-site mutations that alter secondary structure dramatically decrease the ability of BF2 and DesHDAP1 to translocate across membranes [7, 8, 40, 43]. It is quite feasible that this trend would extent to hybrids made from other AMP combinations that individually function via translocating and permeabilizing mechanisms.

Although our hybrid peptides clearly permeabilized membranes, we wanted to further consider whether this trend actually related to the antimicrobial activity of the peptides. To evaluate this question we considered the relationship between the activity of the hybrid peptides and their ability to permeabilize membranes in the PI assay (Fig. 5B). For the hybrids, causing greater membrane permeabilization generally relates to showing more activity, implying that membrane permeabilization is likely one of the primary factors in their activity. Notably, BF2 and DesHDAP1 have much greater activity than one would predict based on their ability to permeabilize membranes (Fig. 5B), emphasizing their ability to target cells via a different mechanism [6-8].

3.3. Trends in the activity of hybrid peptides

Our library also allowed us to systematically evaluate several trends in hybrid peptide activity that could be potentially generalized in the future design of novel, hybrid AMPs.

3.3.1. More active hybrids had permeabilizing parent sequences placed at the N-terminus

In all panels of Fig. 1, hybrids in which the primarily translocating parent is placed at the N-terminal region are shown in red and those where there primarily permeabilizing parent is placed at the N-terminal region are shown in blue. In any cases where differences arose in the activity between these permutations, the more active hybrids had the permeabilizing peptide (parasin or magainin 2) at the N-terminus. This trend likely stems from the hybrid peptides utilizing a permeabilizing mechanism. Previous work has found that the ability of both BF2 and DesHDAP1 to translocate relates to structural deformations in their N-terminal regions induced by a central proline residue [7, 40, 41, 43]. In particular, mutations that stabilize the N-terminal region, such as converting the proline residue to an alanine, increase the membrane permeabilization induced by BF2 and DesHDAP1 [7, 8, 40]. We suspect that placing BF2 or DesHDAP1 at the C-terminal portion of a hybrid similarly stabilizes the deformed region found on the N-terminal side of the proline by placing it next to a more stable region of the partner peptide, increasing the ability of the BF2 or DesHDAP1 portion to promote permeabilization and antimicrobial activity.

3.3.2. Hybridization enhances DesHDAP1 but not buforin II activity

We initially evaluated whether combining two peptides that utilize a different mechanism of action would result in an active hybrid, which we assessed by measuring the activity of all hybrids against E. coli in a radial diffusion assay (Fig. 1). Although all hybrids did show antibacterial activity, it was interesting to note that hybrids containing buforin II (BF2) with either parasin or magainin 2 generally did not show significantly greater activity than BF2 alone (Fig. 1A-B). Conversely, all DesHDAP1 hybrids with magainin and Parasin-Des1 showed significantly greater activity than DesHDAP1 (Fig. 1C-D). Although BF2 was the most active of any parent peptide used, the fact that hybrid peptides generally acted via a permeabilizing mechanism suggests the inherent activity of BF2 may have been lost in the hybrids. Although DesHDAP1 also operates via a translocating mechanism, its relatively lower activity against E. coli may indicate that loss of DesHDAP1 translocating activity may not have as notable of an adverse impact on the activity of its hybrids.

3.3.3. Linkers can alter hybrid activity

We also used our data to consider the potential role of linkers in hybrid peptides. In most cases, the difference in activity between hybrids with and without an alanine linker was relatively minor. Nonetheless, there were a few cases where the linker had a small effect, such as a slight decrease in activity upon introduction of an alanine linker into parasin-BF2 and BF2-parasin (Fig. 1B). Although the presence of linkers did not exhibit any clear generalizable trend, these results do not preclude other linkers having a more marked effect. In particular, it would be useful for future work to systematically consider a wider variety of linkers in the development of hybrid peptides, particularly those with more chemical diversity and structural flexibility.

4. Conclusions

While previous studies have shown the potential of hybrids in AMP design, few studies have attempted to compare the activity of hybrids in a systematic manner. Moreover, no previous work has considered the effect of creating hybrid peptides from one peptide that works by permeabilizing membranes and another peptide that targets intracellular components without inducing permeabilization. The characterization of sixteen hybrid peptides (a full permutation set) in this study allows us to address these unanswered questions.

Our data has several implications for the design of hybrid peptides. First, hybrids containing at least one permeabilizing AMP are likely to kill bacteria primarily through membrane permeabilization. This could be observed through both the high membrane permeabilization caused by the hybrid peptides (Fig. 2) as well as the overall correlation between antimicrobial activity and permeabilization for the hybrids (Fig. 5). Our data also implied that it may be more effective to place permeabilizing peptides at the N-terminus in hybrids that contain only one membrane-active peptide. Although this study considered only a simple single-alanine linker, future work should consider the effect of more chemically diverse linkers on hybrid activity.

Another interesting observation in our work was where mixtures of two individual parent peptides showed equivalent, or even greater, activity than a hybrid made of the same two peptides (Fig. 1A and 1C). Due to the increased cost of synthesizing longer peptides, this type of “cocktail” approach warrants more thorough consideration, and some researchers have begun to consider their effect [11, 44, 45].

In summary, our observations will help to promote the further design of more active antimicrobial peptides. The ability to more predictably design active AMPs will be critical in developing these molecules for therapeutic applications.

Supplementary Material

Highlights for Wade et al.

Hybrid antimicrobial peptides made by combining one membrane permeabilizing and one membrane translocating peptide show antimicrobial activity

These hybrid peptides demonstrate increased membrane permeabilization and decreased membrane translocation relative to parent peptides

Hybrid peptides have activity equivalent to or greater than peptide “cocktails,” mixtures of membrane permeabilizing and membrane translocating peptides

Systematic evaluation of peptide sequence ordering and the inclusion or absence of linkers provide guidance for future peptide engineering efforts

5. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an award from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH-NIAID) award R15AI079685.

Abbreviations:

- AMP

antimicrobial peptide

- BF2

buforin II

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- PI

propidium iodide

- TSB

trypticase soy broth

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Jenssen H, Hamill P, Hancock RE, Peptide antimicrobial agents, Clin Microbiol Rev, 19 (2006) 491–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gordon YJ, Romanowski EG, A review of antimicrobial peptides and their therapeutic potential as anti-infective drugs, Curr Eye Res, 30 (2005) 505–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zasloff M, Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms, Nature, 415 (2000) 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Koo YS, Kim JM, Park IY, Yu BJ, Jang SA, Kim KS, Park CB, Cho JH, Kim SC, Structure–activity relations of parasin I, a histone H2A-derived antimicrobial peptide, Peptides, 29 (2008) 1102–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ludtke SJ, He K, Heller WT, Harroun TA, Yang L, Huang HW, Membrane pores induced byMagainin, Biochemistry, 35 (1996) 13723–13728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Park CB, Kim HS, Kim SC, Mechanism of action of the antimicrobial peptide Buforin II: Buforin II kills microorganisms by penetrating the cell membrane and inhibiting cellular functions, Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 244 (1998) 253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Park CB, Yi K-S, Matsuzaki K, Kim MS, Kim SC, Structure-activity analysis of buforin II, a histone H2A-derived antimicrobial peptide: The proline hinge is responsible for the cell-penetrating ability of buforin II, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 97 (2000) 8245–8250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pavia KE, Spinella SA, Elmore DE, Novel histone-derived antimicrobial peptides use different antimicrobial mechanisms, Biochim Biophys Acta, 1818 (2012) 869–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Andreu D, Ubach J, Boman A, Wathlin B, Wade D, Merrifield RB, Boman HG, Shortened cecropin A-melittin hybrids significant size reduction retains potent antibiotic activity, FEBS Lett, 296 (1992) 190–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Boman HG, Wade D, Boman LA, Wihlin B, Merrifield RB, Antibacterial and antimalarial properties of peptides that are cecropin-melittin hybrids, FEBS Lett, 259 (1989) 103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yu G, Baeder DY, Regoes RR, Rolff J, Combination effects of antimicrobial peptides, Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 60 (2016) 1717–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bolscher JG, Adao R, Nazmi K, van den Keybus PA, van 't Hof W, Nieuw Amerongen AV, Bastos M, Veerman EC, Bactericidal activity of LFchimera is stronger and less sensitive to ionic strength than its constituent lactoferricin and lactoferrampin peptides, Biochimie, 91 (2009) 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Flores-Villasenor H, Canizalez-Roman A, Reyes-Lopez M, Nazmi K, de la Garza M, Zazueta-Beltran J, Leon-Sicairos N, Bolscher JG, Bactericidal effect of bovine lactoferrin, LFcin, LFampin and LFchimera on antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, Biometals, 23 (2010) 569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lopez-Soto F, Leon-Sicairos N, Nazmi K, Bolscher JG, de la Garza M, Microbicidal effect of the lactoferrin peptides lactoferricin 17-30, lactoferrampin265-284, and lactoferrin chimera on the parasite Entamoeba histolytica, Biometals, 23 (2010) 563–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Xu G, Xiong W, Hu Q, Zuo P, Shao B, Lan F, Lu X, Xu Y, Xiong S, Lactoferrin-derived peptides and Lactoferricin chimera inhibit virulence factor production and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, J Appl Microbiol, 109 (2010) 1311–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Xi D, Wang X, Teng D, Mao R, Zhang Y, Wang X, Wang J, Mechanism of action of the tri-hybrid antimicrobial peptide LHP7 from lactoferricin, HP and plectasin on Staphylococcus aureus, BioMetals, 27 (2014) 957–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ptaszynska N, Gucwa K, Legowska A, Debowski D, Gitlin-Domagalska A, Lica J, Heldt M, Martynow D, Olszewski M, Milewski S, Ng TB, Rolka K, Antimicrobial activity of chimera peptides composed of Human Neutrophil Peptide 1 (HNP-1) truncated analogues and Bovine Lactoferrampin, Bioconjugate Chem, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Azpiroz MF, Lavina M, Modular structure of microcin H47 and colicin V, Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 51 (2007) 2412–2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jung S, Mysliwy J, Spudy B, Lorenzen I, Reiss K, Gelhaus C, Podschun R, Leippe M, Grotzinger J, Human beta-defensin 2 and beta-defensin 3 chimeric peptides reveal the structural basis of the pathogen specificity of their parent molecules, Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 55 (2011) 954–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Spudy B, Sonnichsen FD, Waetzig GH, Grotzinger J, Jung S, Identification of structural traits that increase the antimicrobial activity of a chimeric peptide of human beta-defensins 2 and 3, Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 427 (2012) 207–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Olli S, Nagaraj R, Motukupally SR, A hybrid cationic peptide composed of Human β-Defensin-1 and Humanized Θ-Defensin sequences exhibits salt-resistant antimicrobial activity, Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 59 (2015) 217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wei XB, Wu RJ, Si DY, Liao XD, Zhang LL, Zhang RJ, Novel hybrid peptide Cecropin A (1-8)-LL37 (17-30) with potential antibacterial activity, Int J Mol Sci, 17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dong N, Li XR, Xu XY, Lv YF, Li ZY, Shan AS, Wang JL, Characterization of bactericidal efficiency, cell selectivity, and mechanism of short interspecific hybrid peptides, Amino Acids, 50 (2018) 453–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fox MA, Thwaite JE, Ulaeto DO, Atkins TP, Atkins HS, Design and characterization of novel hybrid antimicrobial peptides based on cecropin A, LL-37 and magainin II, Peptides, 33 (2012) 197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hongbiao W, Baolong N, Mengkui X, Lihua H, Weifeng S, Zhiqi M, Biological activities of cecropin B-thanatin hybrid peptides, J Pept Res, 66 (2005) 382–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shin A, Lee E, Jeon D, Park YG, Bang JK, Park YS, Shin SY, Kim Y, Peptoid-substituted hybrid antimicrobial peptide derived from Papiliocin and Magainin 2 with enhanced bacterial selectivity and anti-inflammatory activity, Biochemistry, 54 (2015) 3921–3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Libardo MD, Cervantes JL, Salazar JC, Angeles-Boza AM, Improved bioactivity of antimicrobial peptides by addition of amino-terminal copper and nickel (ATCUN) binding motifs, ChemMedChem, 9 (2014) 1892–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Libardo MD, Paul TJ, Prabhakar R, Angeles-Boza AM, Hybrid peptide ATCUN-sh-Buforin: Influence of the ATCUN charge and stereochemistry on antimicrobial activity, Biochimie, 113 (2015) 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Silva T, Claro B, Silva BFB, Vale N, Gomes P, Gomes MS, Funari SS, Teixeira J, Uhrikova D, Bastos M, Unravelling a mechanism of action for a Cecropin A-Melittin hybrid antimicrobial peptide: the induced formation of multilamellar lipid stacks, Langmuir, 34 (2018) 2158–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Han J, Jyoti MA, Song HY, Jang WS, Antifungal activity and action mechanism of Histatin 5-Halocidin hybrid peptides against Candida ssp, PLoS One, 11 (2016) e0150196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wanmakok M, Orrapin S, Intorasoot A, Intorasoot S, Expression in Escherichia coli of novel recombinant hybrid antimicrobial peptide AL32-P113 with enhanced antimicrobial activity in vitro, Gene, (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lum KY, Tay ST, Le CF, Lee VS, Sabri NH, Velayuthan RD, Hassan H, Sekaran SD, Activity of novel synthetic peptides against Candida albicans, Sci Rep, 5 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kim Y-M, Kim N-H, Lee J-W, Jang J-S, Park Y-H, Park S-C, Jang M-K, Novel chimeric peptide with enhanced cell specificity and anti-inflammatory activity, Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 463 (2015) 322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jindal HM, Zandi K, Ong KC, Velayuthan RD, Rasid SM, Samudi Raju C, Sekaran SD, Mechanisms of action and in vivo antibacterial efficacy assessment of five novel hybrid peptides derived from Indolicidin and Ranalexin against Streptococcus pneumoniae, PeerJ, 5 (2017) e3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tiwari SK, Sutyak Noll K, Cavera VL, Chikindas ML, Improved antimicrobial activities of synthetic-hybrid bacteriocins designed from enterocin E50-52 and pediocin PA-1, Appl Environ Microbiol, 81 (2015) 1661–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Oh D, Shin SY, Lee S, Kang JH, Kim SD, Ryu PD, Hahm KS, Kim Y, Role of the hinge region and the tryptophan residue in the synthetic antimicrobial peptides, cecropin A(1-8)-magainin 2(1-12) and its analogues, on their antibiotic activities and structures, Biochemistry, 39 (2000) 11855–11864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Figueroa DM, Wade HM, Montales KP, Elmore DE, Darling LEO, Production and Visualization of Bacterial Spheroplasts and Protoplasts to Characterize Antimicrobial Peptide Localization, J Vis Exp, 138 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wei L, LaBouyer MA, Darling LEO, Elmore DE, Bacterial spheroplasts as a model for visualizing membrane translocation of antimicrobial peptides, Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 60 (2016) 6350–6352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Cutrona KJ, Kaufman BA, Figueroa DM, Elmore DE, Role of arginine and lysine in the antimicrobial mechanism of histone-derived antimicrobial peptides, FEBS Lett, 589 (2015) 3915–3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kobayashi S, Takeshima K, Park CB, Kim SC, Matsuzaki K, Interactions of the Novel Antimicrobial Peptide Buforin 2 with Lipid Bilayers: Proline as a Translocation Promoting Factor, Biochemistry, 39 (2000) 8648–8654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Xie Y, Fleming E, Chen JL, Elmore DE, Effect of proline position on the antimicrobial mechanism of buforin II, Peptides, 32 (2011) 677–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Bustillo ME, Fischer AL, LaBouyer MA, Klaips JA, Webb AC, Elmore DE, Modular analysis of hipposin, a histone-derived antimicrobial peptide consisting of membrane translocating and membrane permeabilizing fragments, Biochim Biophys Acta, 1838 (2014) 2228–2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kobayashi S, Chikushi A, Tougu S, Imura Y, Nishida M, Yano Y, Matsuzaki K, Membrane translocation mechanism of the antimicrobial peptide Buforin 2, Biochemistry, 43 (2004) 15610–15616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mohan KV, Rao SS, Gao Y, Atreya CD, Enhanced antimicrobial activity of peptide-cocktails against common bacterial contaminants of ex vivo stored platelets, Clin Microbiol Infect, 20 (2014) O39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kobayashi S, Hirakura Y, Matsuzaki K, Bacteria-selective synergism between the antimicrobial peptides R-Helical Magainin 2 and cyclic-sheet tachyplesin I: toward cocktail therapy, Biochemistry, 40 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.