Abstract

Objective:

To provide the first systematic review on the associations between HIV patient navigation and HIV care continuum outcomes (i.e., linkage to care, retention in care, ART uptake, medication adherence, and viral suppression) in the United States (U.S.). We identified primary research studies that addressed these associations and qualitatively assessed whether provision of patient navigation was positively associated with these outcomes, including strength of the evidence.

Methods:

A systematic review, including both electronic (MEDLINE [OVID], EMBASE [OVID], PsycINFO [OVID], and CINAHL [EBSCOhost]) online databases and manual searches, was conducted to locate studies published from January 1, 1996 through April 23, 2018.

Results:

Twenty studies met our inclusion criteria. Of these, 17 found positive associations. Patient navigation was more likely to be positively associated with linkage to care (5 of 6 studies that assessed this association), retention in care (10 of 11), and viral suppression (11 of 15) than with antiretroviral (ART) uptake (1 of 4) or ART adherence (2 of 4). However, almost two-thirds of the 17 studies were of weak study quality, and only three used a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design.

Conclusions:

Available evidence suggests that patient navigation is a potentially effective strategy to enhance engagement in care among persons with HIV (PWH). However encouraging, the evidence is still weak. Studies with more rigorous methodological designs, and research examining characteristics of navigators or navigational programs associated with better outcomes, are warranted given the current interest and use of this strategy.

Keywords: systematic review, patient navigation, HIV care continuum outcomes

INTRODUCTION

With the advent of antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV infection has become a chronic and manageable condition. Not only does ART improve the health of persons with HIV (PWH), viral suppression through ART also substantially reduces the risk of sexual transmission of HIV. PWH who take ART as prescribed and achieve and maintain an undetectable viral load pose effectively no risk of transmitting HIV to their HIV-negative sexual partners [1]. The critical question for HIV prevention planners is how to maximize the number of PWH who are linked to and retained in care for sustained viral suppression. In 2014, of all PWH (including persons with diagnosed and undiagnosed infection) in the U.S., 62% were receiving HIV medical care, less than half were retained in care (48%) and were virally suppressed (49%) [2]. Increasing access to care and improving health outcomes for PWH is one of the national goals in the U.S. [3]. Clearly, more effective strategies that link and retain PWH to HIV care are urgently needed.

Patient navigation, a patient-centered healthcare intervention developed to reduce cancer-related disparities and barriers to care [4], is increasingly being applied in HIV care to assist PWH find their way through a complex and often fragmented healthcare system. Bradford et al.’s [5] HIV system navigation study is often cited as evidence of effectiveness for patient navigation to reduce barriers to HIV care and improve health outcomes of PWH. Bradford et al., describe patient navigation as a model of care coordination that shares some characteristics with advocacy, health education, case management, and social work. However, as reflected in the literature, the field does not appear to have a clear consensus on a standard definition of patient navigation nor what constitutes the specific duties of a navigator [6]. As more studies of HIV patient navigation emerge, assessment of cumulative knowledge is needed to demonstrate its effectiveness. As the first attempt to systematically summarize and evaluate HIV patient navigation programs, we conducted a systematic review to 1) identify primary research studies that examined associations between patient navigation and HIV care continuum outcomes (i.e., linkage to care, retention in care, ART uptake, medication adherence, and viral suppression); (2) qualitatively assess whether provision of patient navigation services is positively associated with HIV care continuum outcomes, including assessment of the strength of the evidence; (3) identify component activities or characteristics of navigation programs that may be linked to the positive associations, including the assessment of a match between target population, activities of navigators, and intended/achieved outcomes; and (4) identify unanswered questions among these studies to pinpoint research gaps. Since healthcare systems vary by country, we focus on patient navigation implemented in the U.S.

METHODS

Database and search strategy

A librarian trained in systematic search methods developed database-specific search strategies using indexing terms and keywords to restrict citations to the following research areas: (1) HIV infections, HIV seropositivity, or AIDS serodiagnosis, AND (2) Patient navigation or care coordination. See Appendix for all searches. The literature search was limited to studies published from January 1, 1996 through April 23, 2018 (last date search was performed). The automated search was performed in MEDLINE (OVID), EMBASE (OVID), PsycINFO (OVID), and CINAHL (EBSCOhost) online databases. In addition, we conducted a manual supplementary search in PubMed pre-published citations, a hand search of key journals in the HIV prevention literature, reference checks of included studies and reviews identified by the search, and search in Scopus and the New York Academy of Medicine’s grey literature database (http://www.greylit.org/).

To be included in this review, studies needed to report the use of HIV patient navigation services or navigation-like services (e.g., assist PWH find their way to obtain HIV care and support services) and report quantitative data assessing an association between navigation services and an HIV care continuum outcome. Studies also needed to be conducted in the U.S., be published in English language in a peer-reviewed journal, and report primary data. Reviews, unpublished materials and conference abstracts were excluded.

Screening and data abstraction

Citations were screened in two steps. First, two coders independently screened the titles and abstracts of all citations identified from the search using the DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada). Next, for each included citation, two coders independently assessed the full report for relevancy. For each of the eligible studies, pairs of coders independently abstracted the following information using a standardized coding form developed and piloted for this review: study characteristics (e.g., location, setting, design, sample size, outcome measures, and limitations), participant characteristics, activities of patient navigators, and study findings. All discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Assessment of study quality

We used the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project [7] to assess study quality. Each study was rated by a pair of coders for selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, and withdrawals/dropout. Based on the number of components rated as “weak” (criteria defined by the tool), each study was rated as strong (no “weak” ratings), moderate (one “weak” rating), and weak (two or more “weak” ratings).

Determination of study finding per outcome

Due to the heterogeneity across studies in study designs, outcome measures, analytic approaches, and presentation of statistical results, we conducted a qualitative synthesis rather than a meta-analysis. The evidence of a positive association was determined by a statistically significant (p<0.05) association between patient navigation and an outcome. When no statistical test was reported, we determined the evidence by the direction of association (i.e., positive association). When unadjusted and adjusted findings were both reported, adjusted findings were used.

Eight studies reported more than one finding per specific outcome (average 2, minimum-maximum: 2-4 findings) as they used equally valid multiple measures [8-12] or multiple types of contrasts [5, 13-14]. For these cases, we designated the evidence as: 1) a “positive association” if >50% of the results showed statistically significant (p<0.05) positive associations between HIV patient navigation and the outcome; 2) a “mixed result” if 50% of the results showed statistically significant positive associations; and 3) a “null association” if <50% of the results showed statistically significant positive associations. With these decision rules, we had one finding per outcome for each study. We qualitatively summarized the findings.

RESULTS

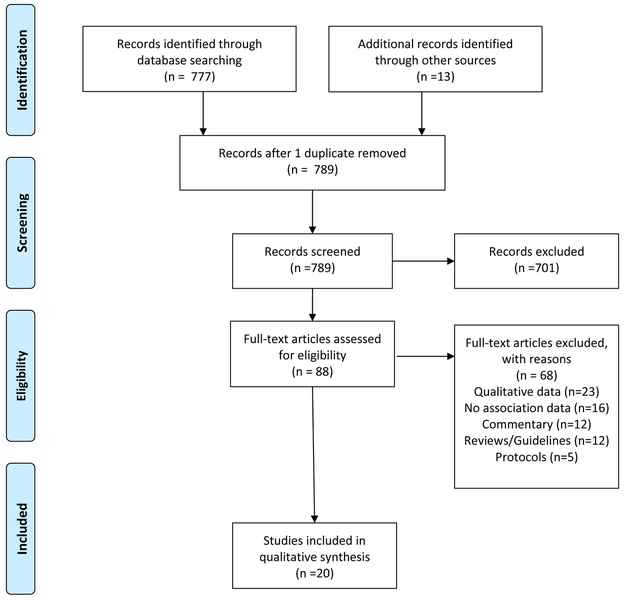

Of 789 unique citations identified through electronic and hand searches, 20 studies were included in this review. (See Figure 1 for detailed selection process.) Table 1 presents these studies’ characteristics. Studies were published from 2005 to 2018. Study locations were primarily large cities in the U.S. with high HIV prevalence. Study settings were mostly clinics (n=13) or community based organizations (n=6) but a few studies were conducted in jail settings (n=5) [11, 15-17]. Five (25%) [10-11, 13, 15, 18] were RCTs and 10 (50%) used either a pre-post one-group design or a non-RCT with a comparison group. Twelve (60%) were rated as of weak study quality.

Figure 1.

Study Flow Diagram

Table 1.

Summary of studies that assessed associations between patient navigation and HIV care continuum outcomes (Publication dates: 2005-2018, k=20)

| Lead Author Year |

Study Location |

Setting | Sample (n) | Study Design | Activities of the Navigator as Described in the Study & Amount of Time the Navigator Spent with Clients |

Outcome Measures | Study Findings | Evidence of whether patient navigation is positively associated with outcome |

Study Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andersen et al 2007 [8] | Detroit, MI | Nursing outreach clinic; CBO1 | HIV-positive women who show problems keeping their medical appointments (n=112) | Two groups non RCT2 | Made at least one home visit, accompanied the client to at least one HIV primary care visit to translate the treatment plan to her. Helped identify and address client concerns to improve client sense of well-being and eliminate access to care barriers. Referred clients to drug treatment or accompanied them to mental health appointments, using “hyperlinking” i.e., transportation and accompaniment. A client was assigned to the navigator for 6 months. |

Retention: Mean number of HIV medical visits in the past 6 months (chart review and self-report) Mean number of missed appointments in the past 6 months (self-report) |

In the intervention group, the number of charted and self-reported HIV medical visits increased. 1.08 at pre-intervention 1.60 at 6 month 1.04 at 12 month, F (2, 94)=5.60, p=0.007 (chart review) 1.45 at pre-intervention 2.16 at 6 month 2.16 at 12 month, F (2, 60)=4.444, p=0.016 (self-report) In the comparison group, no significant overall differences in the mean number of charted and self-reported HIV medical visits were observed. 1.33 at pre-intervention 1.47 at 6 month 1.09 at 12 month F(2, 112)=1.823 p=0.166 (chart review) 2.51 at pre-intervention 2.38 at 6 month 2.46 at 12 month F<1 (self-report) In the intervention group, the number of self-reported missed appointments decreased 1.68 at pre-intervention 0.90 at 6 month 0.74 at 12 month, F (2, 60)=5.103, p=0.009 In the comparison group, the number of self-reported missed appointments decreased 1.92 at pre-intervention 0.72 at 6 month 1.03 at 12 month F=11.534, p<0.001 |

Yes | Weak |

| Asamsama et al., 2017 [23] | District of Columbia | Clinic3 | HIV-positive veterans poorly engaged in care (n=84) | One group pre-post | Provided individualized care management, intensive outreach, and collaborated with existing support systems. Actively reached out to patients. Provided medication adherence and clinic engagement support (e.g., pillbox renewals, reminder calls regarding upcoming appointments and medication renewals), sent text reminders, offered same day walk-in appointments, and collaborated with family members and other medical staff. Regularly maintained a database that included medication renewal dates, upcoming appointments, and a record of most recent contact, and disseminated any relevant information to the treatment team members. Five-month duration with the navigator |

Adherence: % of completed medication renewals (clinical registry/electroni c medical record) Viral Suppression: Viral load <200 copies/mL at the most recent lab test (laboratory value) |

% of clients who renewed medication increased. 40.9% at pre-intervention 80.6% at post-intervention p<0.001 % of clients who were virally suppressed increased. 47.6% at pre-intervention 69.0% at post-intervention P=0.03 |

Yes Yes |

Moderate |

| Bove et al 2015 [9] | Seattle, WA | Clinic4 | Out of care HIV-positive patients (n=1399) | Two groups historical comparison | Attempted to contact out of care patients and assisted them with scheduling and completing a medical visit at the clinic. Worked with patients and clinic staff to schedule appointments, reminded patients of appointments as needed, and followed-up to determine whether the patients completed their re-linkage appointments. Could meet patients outside of clinic or in the inpatient unit, assisted with transportation, and tracked contact attempts and interactions with the patient in a database. 0.75 FTE5 over 12 months; Median contacts by the navigator=4 (IQR6 3-6) |

Linkage: Time to re-linkage to care (clinical data) Relinked to care at any point during the 12-month study period (clinical data) Retention: Completed ≥2 visits ≥3 months apart (clinical data) Viral suppression: HIV RNA<200 copies/mL (clinical data) |

Patients in the intervention cohort were relinked to care earlier than patients in the historical cohort. Adjusted HR7=1.7 (95% CI8: 1.2-2.3) Patients in the intervention cohort were more likely to be relinked to care than patients in the historical cohort. 15% vs. 10%, Adjusted RR9=1.6 (95% CI: 1.2-2.1) Patients in the intervention cohort were more likely to be retained in care than patients in the historical cohort. Adjusted RR=2.4 (98% CI: 1.5-3.9) No significant difference in viral suppression was observed between the two cohorts in adjusted analysis. Adjusted RR=1.6 (95% CI: 0.97-2.6) |

Yes Yes No |

Weak |

| Bradford et al., 2007 [5] | Portland, OR; Seattle, WA; Boston, MA; Washington DC | Clinic | HIV-positive patients not fully engaged in care or at risk of falling out of care (n=437) | One group pre-post | Helped clients build their provider interaction skills, helped them learn how to navigate the health and social service systems and how to address different barriers to care, and accompanied them to appointments. For the majority of sites, contacts with clients involved appointment coordination, service coordination, service provision, and relationship building. Time with the navigator was not reported. |

Retention: Receipt of ≥2 HIV primary care visits in a 6-months period (self-report) Viral suppression: Undetectable viral load (medical record) |

% of clients who were retained in care increased. 63.9% at pre-intervention 86.9% at 6 months pre-post change p<0.001 78.9% at 12 months pre-post change p<0.001 % of clients with undetectable viral load increased. 34.8% at pre-intervention 53.5% at 6 months pre-post change p<0.05 53.1% at 12 months pre-post change p<0.01 |

Yes Yes |

Weak |

| Brennan-Ing et al., 2016 [22] | New York City, NY | Non-profit managed care organization | HIV-positive managed care clients with multiple comorbid conditions (e.g., behavioral health issues) not accessing medical and supportive services (n=2072) | Observational cohort | Assisted clients in navigating the health care system. Used a team of case managers and para-professionals to provide comprehensive and intensive case management services (e.g., services to promote independence, adherence, prevention of institutionalization, HIV-related services, disease prevention and early intervention). Time with the navigator was not reported. |

ART uptake: Prescription fills for ART | No significant difference in ART prescriptions was observed over the study period. 4.55 during the first 3 months 4.89 during the last 3 months F(1, 3446)=0.98, p=0.32 | No | Weak |

| Cabral et al., 2007 [26] | East and West Coasts of the US and Midwest | Not reported | HIV-positive persons enrolled at the 10 HRSA10 funded Outreach Initiative sites. They were all at risk of non-retention in HIV care (n=773) | Observational cohort | Most sites provided outreach, advocacy, and support services, but beyond this the interventions varied across the 10 sites: behavioral interventions (2 programs); accompaniment to clinic appointments (6 programs); home-based services (1 program); literacy and life skills training (2 programs). A total of 8244 contacts for 773 clients in the first 3 months |

Retention: The time from study intake to the first 4 month gap in HIV primary care (chart review) | Participants with 9 or more intervention contacts were half as likely as those with 0 contacts to have a gap in care. Adjusted HR=0.45 (95% CI: 0.26-0.78) | Yes | Weak |

| Cabral et al., 2018 [10] | Miami, FL; Brooklyn, NY; San Juan, PR | Clinic11 | HIV-positive racial minorities out of care or new or newly diagnosed patients with a need for substance use, mental health or housing services (n=348) | RCT12 | Educated the patient about HIV, assisted the patient to obtain needed services via knowledge of resources, appointments reminders and accompaniment, provided emotional support by active listening and coaching, and linked the patient to social networks. Seven on-on-one 60-minutes educational sessions every 1-3 weeks and weekly or biweekly check-in for up to 4 months during the same period |

Retention: The time-to-first 4-month gap in HIV primary care (chart review) The occurrence of any 4-month gap in HIV primary care (chart review) Viral suppression: <200 copies/mL in the interval from baseline to 6 months (laboratory result) <200 copies/mL in the interval from greater than 6 months to 13 months (laboratory result) |

No significant difference in the time-to-first 4-month gap in care was observed between the navigation intervention participants and the standard of care participants. X2=0.002, p=0.96 No significant difference in the occurrence of any 4-month gap in care was observed between the navigation intervention participants and the standard of care participants. 40% vs. 39%, X2=0.05, p=0.83 No significant difference in the % of participants with viral suppression was observed between the navigation intervention participants and the standard of care participants in the interval from baseline to 6 months 52% vs. 52%, X2=0.02, p=0.89 % of the navigation intervention participants with viral suppression was significantly lower than % of the standard of care participants in the interval from greater than 6 months to 13 months 52% vs. 65%, X2=4.31, p=0.04 |

No No |

Strong |

| Cunningham et al., 2018 [15] | Los Angeles, CA | LA County Jail | HIV-positive men and transgender women leaving jail (n=356) | RCT | Acted as role models that walk participants through the care continuum steps (linkage or re-engagement, retention, and ART adherence.) before and after release. Taught skills for overcoming stigma and discrimination and facilitated access to care by scheduling appointments, providing appointment reminders, transportation assistance, accompaniment to visits, and assistance with meeting competing needs. Twelve (60-120 minutes) sessions over 24 weeks including accompaniment to two HIV medical care appointments after a client was released from jail |

Linkage: Report having at least one post-release HIV primary care visit at 3 months follow-up visit (self-report) Retention: Number of HIV primary care visits per 12 months, given at least one visit in the previous 12 months (self-report) ART uptake: Currently using ART (self-report) Adherence: 100% indicating perfect adherence (self-report) Viral Suppression: Undetectable viral load (<75 copies/mL) (medical record and blood draw) |

No significant difference in the % post-release linkage reported at 3 months follow-up visit 64% vs. 63%, Difference=1% (95% CI: −9%-12%, p=0.81) There was a greater increase from baseline in the number of visit per year since release in the peer navigation arm than in the control arm (standard transitional case management) over 12 months 0.61 vs. −0.10, Difference-in-difference 0.71 (95% CI: 0.01-1.40, p=0.047 No significant differences in the % using ART were observed between the arms at any time points Peer navigation arm: 98% at baseline, 95% at 12 months Control arm: 99% at baseline, 96% at 12 months, Difference-in-difference −1% (95% CI: −5%-4%, p=0.82) No significant differences in the adherence rate were observed between the arms at any time points Peer navigation arm: 85.7% at baseline, 86.7% at 12 months Control arm: 81.6% at baseline, 85.4% at 12 months, Difference-in-difference −2.8% (95% CI: −11.6%- 6.1%, p=0.20) The peer navigation arm’s adjusted probabilities of viral suppression did not change while it declined in the control arm. Peer navigation arm: 49% at baseline, 49% at 12 months Control arm: 52% at baseline, 30% at 12 months, Difference-in-difference 22% (95% CI: 3%-41%, p=0.02) |

No Yes No No Yes |

Strong |

| Gardner et al., 2005 [18] | Miami, FL; Baltimore, MD; Los Angeles, CA; Atlanta, GA | Clinic13 and CBO | Recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons not in care (n=273) | RCT | The intervention14 provided time-limited assistance to link clients to HIV care. Allowed up to five case management contacts per client; the first three built the relationship, identified and addressed client needs and barriers to care, and encouraged contact with a clinic. If needed, fourth and fifth contacts involved encouraging contact with a clinic and accompaniment to a clinic visit. A total of 350 contacts (average 2.6 per client) over a 90 day period |

Linkage: Made a visit to an HIV clinician at least once within the first 6 months follow-up period (self-report) Retention: Attendance at an HIV care provider at least once in each of two consecutive 6 month periods (self-report) |

A higher proportion of the intervention participants than the standard of care participants were linked to care 78% vs. 60% Adjusted RR=1.36 (p=0.0005) A higher proportion of the intervention participants than the standard of care participants were retained in care 64% vs.49% Adjusted RR=1.41 (p=0.006) |

Yes Yes |

Moderate |

| Irvine et al., 2015 [24] | New York City, NY | Clinic15 and CBO | HIV-positive persons at high risk for or with recent history of suboptimal HIV care outcomes (n=3641) | Observational cohort | Provided all home-based care coordination services. Educated, coached, and empowered patients. Accompanied patients to primary care and other health care and social services appointments. Coordinated ongoing navigation and logistical support for appointments (e.g., reminders, transportation support, child care arrangements). Administered the health promotion curriculum and tracked the patient’s health promotion needs. Assisted the Care Coordinator and worked collaboratively with Program and Medical staff.16 Time with the navigator was not reported. |

Retention: Having at least 2 lab tests (CD4 and viral load) dated a least 90 days apart, with at least one of those tests in each half of a given 12-month review period. (HIV registry data) Viral suppression: Viral load ≤200 copies/mL at the most recent viral load test in the second half of the 12-month review period (HIV registry data) |

Among previously diagnosed clients17 (n=3176), % retained in care increased. 73.7% at the 12-month period pre-enrollment 91.3% at the 12-month period post-enrollment RR=1.24 (95% CI: 1.21-1.27) Among previously diagnosed clients18 (n=3176), % with viral suppression increased. 32.3% at the 12-month period pre-enrollment 50.9% at the 12-month period post-enrollment RR=1.58 (95% CI: 1.50-1.66) |

Yes Yes |

Moderate |

| Irvine et al., 2017 [25] | New York City, NY | Clinic19 and CBO | Newly diagnosed HIV-positive clients20 or those who have documented lapses in or barriers to HIV care (n=7058) | Observational cohort | Tasks included providing appointment reminders, assisting with scheduling appointments, providing transportation resources, and accompaniment to primary care. Time with the navigator was not reported. |

Retention: Having at least 2 lab tests dated ≥ 90 days apart with one in each half of the year (Registry) Viral suppression: Having a viral load ≤ 200 copies/mL at the latest test in the second half of the year (Registry) |

Among previously diagnosed21 (n=5941), the proportion of clients who were retained in care increased. 69.6% at the pre-enrollment period 90.7% at the post-enrollment period RR=1.30 (95% CI: 1.28-1.33) Among previously diagnosed22 (n=5941), the proportion of clients who were virally suppressed increased. 30.3% at the pre-enrollment period 54.4% at the post-enrollment period RR=1.80 (95% CI: 1.73-1.87) |

Yes Yes |

Moderate |

| Jordan et al., 2013 [16] | New York City, NY | New York City jail system | HIV-positive persons released from jails (n=2176) | Program outcome evaluation | Provided initial transitional services on the 1st day after a client was admitted to the jail, arranged with DOC23 for the client to be escorted to a private office. Assessed client’s needs and barriers to care (e.g., housing, food, clothing, primary care, health insurance), addressed the needs and documented them in the discharge plan that also included referral to behavioral health treatment for substance use or mental illness. Managed the time between jail release and linkage to community care (e.g., transportation and accompaniment to initial primary care appointments upon release), verified linkage to care, conducted home visits, located clients not confirmed to be linked within 30 days of release, and facilitated linkage to care.) Time with the navigator was not reported. |

Linkage: Linked to a community health provider within 30 days of release from jail (electronic health record [EHR]) | % linked to care among those released to the community increased. 70% (941/1345) in 2009; 75% (1259/1676) in 2010; and 73% (1336/1824) in 2011 (no statistical test) | Yes | Weak |

| Kral et al., 2018 [19] | Oakland, CA | Street settings, referrals from county jails | HIV-positive persons not in care who inject drugs or smoke crack cocaine (n=48) | Two groups non RCT | Worked in partnership with a HIV physician to provide intensive case management to the intervention participants. Met weekly with the physician about each participant’s clinical and social needs. Kept notes of these meetings, and met with the participants daily to biweekly, depending on the need (including conducting outreach if they lost contact with participants). Accompanied participants to medical, social service, and other appointments. Was also the link between jail and community settings. Visited the participant in jail and advocated for their access to HIV treatment while in jail. Also coordinated continuity of care upon the participant’s release from jail. The amount of time the navigator spent with clients varied from daily to bi-weekly check-ins, depending on the needs and housing situation of the client. |

Viral Suppression: Viral load <200 copies/mL (blood draw) | In GEE24 repeated measures analysis, intervention participants had a higher odds of achieving undetectable viral load over time than comparison group (p=0.033) Adjusted analysis did not significantly change the main association between intervention and undetectable viral load found above. (Statistics not provided). |

Yes | Weak |

| Maulsby et al., 2015 [20] | Chicago, IL; New York City, NY; New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Lake Charles, Shreveport, LA | Clinic25, CBO, Public testing sites, Medicaid managed care insurance plan | Chicago: Men who have sex with men (n=564) Louisiana: Incarcerated, newly diagnosed and out of care (n=998) New York City: Members of Medicaid managed care plan (n=1053) | One group pre-post | Across sites, the program linked out of care patients to resources, primary medical care, social support/support services, and enhanced retention in care. Using a peer health navigation approach, identified and enrolled PWH26, provided short-term peer health navigation, facilitated access to HIV care through existing services, and enhanced retention in care through peer-led group education (Chicago); Used pre-and post-release case management, peer/patient navigation, intensive case management, and case finding (Louisiana); Used outreach and health navigation. Health navigators filled a more long-term role compared to community health outreach workers (New York City). Time with the navigator was not reported. |

Retention: Two visits 60 days apart in past 12 months27 Viral suppression: Viral load ≤200 copies/mL10 |

% of clients who were retained in care increased. Chicago: 0% at baseline 75.5% at either 6 or 12-month follow-up Louisiana: 23.4% at baseline 57.2% at follow-up New York City: 28.8% at baseline 76.5% at follow up (no statistical test) % of clients with viral suppression increased. Chicago: 44.1% at baseline 50.2% at either 6 or 12-month follow-up. Louisiana: 15.2% at baseline 36.3% at follow-up New York City: 19.6% at baseline 54.1% at follow-up (no statistical test) |

Yes Yes |

Weak |

| Metsch et al., 2016 [13] | Atlanta, GA; Baltimore, MD; Boston, MA; Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Dallas, TX; Los Angeles, CA; Miami, FL; New York, NY; Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, PA | Clinic28 | Hospitalized patients with HIV infection and substance use (n=801) | RCT | Worked with participants to coordinate care, review health information, and overcome challenges such as access to transportation and child care. Encouraged participant-identified sources of support and made referrals to provide psychosocial support. Also accompanied to the first substance use disorders treatment and HIV care appointments. Up to 11 sessions over a 6 month period; the median number completed in the navigation only arm=7 (IQR 5-10), and for the navigation plus financial incentive arm=11 (IQR 8-11) |

ART uptake: Having been prescribed HIV medications at 6 and 12 months (self-report)29 Adherence: % of pills taken last 30 days (self-report) Viral suppression: Viral load ≤200 copies/mL (lab report) |

No significant difference in ART uptake was observed between the navigation-only participants and the usual care participants at 6-month follow-up 84.0% (189/225) vs. 77.3% (180/223), p=0.05, and at 12-month follow-up 81.9% (177/216) vs. 81.9% (177/216) p=0.76 The navigation plus financial incentive participants were more likely than usual care participants to be prescribed ART at 6 month follow-up 91.3% (221/242) vs. 77.3% (180/223), p<0.001. No significant difference in ART uptake was observed between the navigation-plus financial incentive participants and the usual care participants at 12-month follow-up 88.8% (199/224) vs. 81.9% (177/216), p=0.06. No significant difference in adherence was observed between the navigation-only participants and the usual care participants at 6-month follow-up 81.0% vs. 82.0%, P=0.20, and at 12-month follow-up 79.9% vs, 83.1% p=0.20 No significant difference in adherence was observed between the navigation-plus financial incentive participants and the usual care participants at 6-month follow-up 86.2% vs. 82.0%, p=0.14, and at 12-month follow-up 81.3% vs, 83.1% p=0.17 No significant difference in viral suppression was observed between the navigation-only participants and the usual care participants at 6-month follow-up 43.1% (97/225) vs. 38.2% (89/253), p=0.30, and at 12-month follow-up 41.0% (89/217) vs. 38.6% (85/220) P=0.81 Navigation-plus financial incentive participants were more likely than the usual care participants to be virally suppressed at 6-month follow-up 50.4% (120/238) vs. 38.2% (89/253), p=0.03. No significant difference in viral suppression was observed between the navigation-plus financial incentive participants and the usual care participants at 12-month follow-up 43.6% (98/225) vs. 38.6% (85/220), p=0.70. |

No No No |

Strong |

| Myers et al., 2018 [11] | San Francisco, CA | San Francisco County Jail | HIV-positive persons leaving jail (n=270) | RCT | Facilitated clients’ re-entry into care in the community, referrals (for housing, employment, substance dependence, mental health treatment, legal issues, social benefits, social security insurance), discussed how to avoid re-incarceration; and provided coaching and mentoring support. Navigators worked in tandem with the case manager to monitor adherence to care and to enhance case management services post-release (e.g., securing transportation and/or accompanying clients to appointments, securing food and housing services). Time with the navigator was not reported. |

Linkage: At least one documented non-urgent medical care visit to a provider within 30 days of release from jail (electronic medical record) Retention: Had a non-urgent medical care visit between each of the study follow-up visits (2, 6, and 12 months) (electronic medical record) Viral Suppression: Viral load <50 copies/mL between 9-18 months after release (laboratory test) Having at least 2 viral load measures between 9-18 months after release with all viral load measures <200 copies/mL (laboratory test) |

The navigation-enhanced intervention participants were significantly more likely than the treatment as usual participants to be linked to care within 30 days of release AOR30=2.15 (95% CI: 1.23-3.75) The navigation-enhanced intervention participants were significantly more likely than the treatment as usual participants to be retained in care over 12 months AOR=1.95 (95% CI: 1.11-3.46) No significant difference in viral suppression was observed between the navigation-enhanced intervention participants and the treatment as usual participants (data not shown) No significant difference in sustained viral suppression was observed between the navigation-enhanced intervention participants and the treatment as usual participants (data not shown) |

Yes Yes No |

Strong |

| Shacham et al., 2017 [12] | St. Louis, MO | Clinic31, CBO, City Health Department | HIV-positive persons not in care (n=322) | One group pre-post | Met clients and accompanied clinic visits to offer support, explain the process of the visit, and describe medication adherence and care practices in detail. Time with the navigator was not reported. |

Viral suppression: Viral load≤200 copies/mL (medical record) Undetectable Viral load≤20 copies/mL (medical record) |

% of clients with viral suppression increased 12.8% at baseline 70.9% at 6 months p<0.01 % of clients with undetectable viral load increased 6% at baseline 44.9% at 6 months p<0.01 |

Yes | Weak |

| Teixeira et al., 2015 [17] | New York City, NY | New York City jails | HIV-positive persons released from jails (n=434) | One group pre-post | See Jordan et al., 2013 Time with the navigator was not reported. |

ART uptake: Currently on ART (self-report) Adherence: ART taken as directed (self-report) Viral suppression: Actual viral load values (lab report) |

% of clients currently on ART increased. 55.6% at baseline 92.6% at 6 months p<0.05 % of clients taking ART as directed increased 80.7% at baseline 93.2% at 6 months p<0.05 Actual viral load values decreased. 54,031 at baseline 13,738 at 6 months p<0.05 |

Yes Yes Yes |

Weak |

| Wohl et al., 2016 [14] | Los Angeles, CA | Clinic | HIV-positive persons not in care including newly diagnosed and those who were recently release from jail, prison, or other institutions (n=78) | One group pre-post | Located patients and provided a modified ARTAS32 intervention. Modifications included increasing the number of sessions to 10 sessions, not providing the incentive, combining the “linking to resources” and “enhancing strengths” components and providing an option to alternate between them, adding a tool to assess readiness to engage in care, and the collection of detailed information to locate participants. The program had 4 components: building the relationship; assessment; linking to resources/enhancing strengths; and disengagement. An average of 4.5 navigator sessions over 11.6 hours |

Linkage: Previously lost patients having either 2 medical visits or 1 medical and 1 case management visit Viral suppression: Not defined (HIV surveillance data) |

% of clients linked to care increased. 68% at 3 month 85% at 6 month 94% at 12 months (no statistical test) % of clients with viral suppression increased. 51% at pre-enrollment vs. 63% at time of retention X2=11.8, p<0.01 52% at the linkage appointment vs. 63% at time of retention X2=6.1, p<0.01 |

Yes Yes |

Weak |

| Wohl et al., 2017 [21] | Los Angeles, CA | Clinic | Hard-to-reach HIV-positive persons who were out of care including recently diagnosed and those who were recently released from a jail, residential treatment facility or other institution (n=112) | One group pre-post | Provided a map and list of HIV care services. Scheduled an HIV care appointment and made/send reminder calls/text messages about the visit. Provided transportation vouchers and accompanied the client to the visit. Assisted the client navigate the HIV clinic system, e.g., the financial screening process. Staff spent an average of 10.3 hours to link clients to care |

Viral suppression: Viral load<200 copies/mL (HIV surveillance data) | % of clients with viral suppression increased. 26.4% at the time of linkage to care vs. 39.7% at the second viral load measurement 6-12 months after study linkage p=0.04 | Yes | Weak |

CBO=community based organization

Intervention Group: Sample=women who used heroin and/or acknowledged mental health problems; Six months of transportation service plus navigator, followed by 6 months of transportation only. Comparison Group: Sample=women who did not use heroin nor acknowledge mental health problems; Transportation only for 12 months.

VA Medical Center

HIV clinic

FTE=full time equivalent

IQR=interquartile range

HR=hazard ratio

CI=confidence interval

RR=relative risk

HRSA=Health Resources and Services Administration

Ryan White Part C clinic

RCT=randomized controlled trial

Public health clinics, testing centers, hospital inpatient, Emergency Room/walk-in clinics, drug treatment center

ARTAS (Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study)

Hospitals

Information was provided in the “Care Coordination for People with HIV Program Manual Version 5.0” Issued by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

In stratified analyses, the significant improvements for retention was generally held across subgroups.

In stratified analyses, the significant improvement for viral suppression was generally held across subgroups.

Hospitals

Only the previously diagnosed were included in the outcome analysis.

In stratified analyses, significant improvements in retention were observed in all subgroups (including those with lower mental health functioning, unstable housing, or hard drug use).

In stratified analyses, significant improvements in viral suppression were observed in all subgroups (including those with lower mental health functioning, unstable housing, or hard drug use).

DOC = Department of Correction

GEE=generalized estimating equation

Hospital system, STD clinics, primary care clinics

PWH=persons with HIV

Chicago: Administrative records, surveillance data, lab records; Louisiana: State surveillance data; New York City: Managed care plan claims data

Hospitals

The study reported ART uptake findings from medical records but medical records were not available in about 25~30% of the samples, and thus were not considered in this review.

AOR=adjusted odds ratio

Hospitals

ARTAS=Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study [21]

Target populations were primarily PWH who had challenges being engaged in HIV care. Examples include PWH with a history of incarceration (n=8) [11, 14-17, 19-21], with recent/new HIV diagnosis (n=5) [10, 14, 18, 20-21], with comorbid conditions such as substance use and mental health problems (n=4) [10, 13, 19, 22], and those who were veterans (n=1) [23], women (n=1) [8], or racial minorities (n=1) [10].

Patient navigators engaged in a range of activities that can be summarized with the categorization used in Bradford et al., 2007 [5], i.e., accompanying HIV-positive clients to appointments, coordinating their clients’ appointments, providing non-clinical services (e.g., transportation, food, clothing), providing HIV information, referring clients to HIV care or other health services, and relationship building. Five studies [10-12, 15, 20] indicated that the navigators were “peers” (e.g., being PWH and/or having similar sociodemographic characteristics as the clients), 3 studies [8, 19, 23] indicated that the navigators had professional degrees such as nursing or clinical social work, and 3 studies [5, 14, 16] indicated that the navigators had Bachelors’ degrees. In some studies there was no clear boundary between the roles of patient navigators and case managers (e.g., case management was part of the navigator’s duty or the case manager performed patient navigation [11, 13-14, 16-18]), while others had a clear separation of roles between them or reflected the idea that patient navigation and case management are two separate strategies [5, 9-10, 12, 15, 20, 24-25] (Data not shown in the table). Six studies assessed patient navigation-related associations with linkage to care, 11 with retention, 4 with ART uptake, 4 with medication adherence, and 15 with viral suppression. Studies did not uniformly report information on the duration or intensity of contacts between the patient navigator and their clients. The two studies that provided the most comprehensive information were Cabral et al., 2018 [10] and Cunningham et al., 2018 [15] (see Table 1).

Studies with any positive associations

Seventeen out of the 20 studies (85%) [5, 8-9, 11-12, 14-21, 23-26] reported any positive associations between patient navigation and any HIV care continuum outcome. Except for the three studies that did not provide statistical tests [14, 16, 20], all of the positive associations were statistically significant.

Among these 17 studies, three (18%) used an RCT design, 10 (59%) used either a pre-post one-group design or a non-RCT with a comparison group, and four (23%) were from observational, correlational, or program evaluation studies. As for study quality, two of the 17 (12%) were rated as strong, 4 (23%) as moderate, and 11 (65%) as weak. Among these 17 studies, 5 reported positive associations with linkage, i.e., 83% of the 6 total studies that assessed the association between navigation and linkage. Ten reported a positive association with retention (i.e., 91% of the 11 total that assessed this association), one with ART uptake (i.e., 25% of the 4 total), 2 with medication adherence (i.e., 50% of the 4 total), and 11 with viral suppression (i.e., 73% of the 15 total). Of these 17 citations, only 3 [9, 11, 15] reported any null associations (none reported negative associations) between patient navigation and HIV care continuum outcomes.

As for the specific activities conducted by the patient navigator of these 17 studies, 12 (71%) reported accompaniment to appointments and 10 (59%) reported appointment coordination. Service provision (e.g., transportation) was reported by almost half (n = 8, 47%) of the citations, followed by relationship building (n = 7, 41%), provision of HIV information (n = 6, 35%), and service coordination (n = 6, 35%). Referral to HIV care or other health services was reported by almost a third (n = 5, 29%).

Among these 17 studies, there was a considerable match between the target population, intended and achieved outcomes, and the activities of the patient navigators to address these outcomes. For example, a study by Gardner et al., (2005) [18] specifically targeted recently diagnosed PWH. The study aimed at and was successful in improving linkage and retention in HIV care via relationship building, addressing barriers to health care, encouraging contact with a clinic, and sometimes accompaniment to a clinic visit. Recognizing that PWH generally receive HIV care in jails but fail to do so after being released into the community, studies that solely targeted PWH who were released from jails aimed at and were successful in linking them into HIV care or promoting ART uptake after release [11, 16-17], retaining them in care after release [11, 15] and reducing vial load or maintaining viral suppression after release [15, 17]. Addressing a host of post-release issues (e.g., lack of transportation, housing, employment, social stigma, and discrimination) and accompaniment to the initial primary care visit upon release to ensure linkage were common across these programs.

Studies that included PWH with poor engagement in care as evidenced by, for example, lapse in documented HIV care, aimed to and successfully re-linked and/or retained them in HIV care [5, 8-9, 14, 20, 24-26]. Many of these programs also reported significant positive associations with viral suppression [5, 12, 14, 19-21, 23-25]. Outreach to those who are out of care, assisting with scheduling appointments, appointment reminders, assistance with transportation and accompaniment to a clinic visit were common across these programs.

Studies that did not find any positive associations

Three [10, 13, 22] out of the 20 studies did not find any positive associations between patient navigation and HIV care continuum outcomes. Two of the 3 studies used a RCT design [10, 13] and the other was an observational study. With respect to study quality, two were rated as of strong study quality [10, 13] and one as weak [22],

The target population of these studies were those with comorbid conditions such as substance use and mental health/behavioral health issues. Two of these studies [10, 13] reported accompaniment to appointments, appointment coordination, concrete service provision, and provision of HIV information. In addition, Cabral et al., 2018 [10] reported relationship building (e.g., connecting the patient with social networks) and Metsch et al., 2016 [13] reported referral to non-HIV health services and accompaniment to the first substance disorders treatment appointment.

DISCUSSION

Only 20 out of 789 unique citations identified by systematic search have examined associations between patient navigation and HIV care continuum outcomes. Among these 20 studies, 17 (85%) found one or more positive associations, showing some evidence supporting patient navigation as a potentially effective strategy to enhance engagement in care among PWH. However, only three of the 17 studies were RCTs, and many of them (65%) were rated as being of weak study quality. On the other hand, 2 of the 3 studies that reported no positive findings were RCTs and one was rated as of weak quality. Taken together, these data suggests that positive findings were more likely to be found in studies with weaker study designs/quality. It is clear that more studies with rigorous design are needed to establish a solid evidence base.

Overall, fewer studies assessed ART uptake and adherence than assessed linkage to care, retention in care and viral suppression. Keeping the above caveat in mind, patient navigation was more likely to be positively associated with linkage (5 out of the 6 studies that assessed associations between patient navigation and linkage to care found positive associations), retention (10 out of 11), and viral suppression (11 out of 15) than with ART uptake (1 out of 4) or ART adherence (2 out of 4). Positive associations with linkage to and retention in care suggest that patient navigation may be successful in moving PWH through the complexities of the medical system and keep them from falling out of care. Associations with viral suppression are a welcome finding. Achieving viral suppression is the ultimate clinical goal, but is often considered a distal outcome that may not necessarily be achieved even when earlier steps in the continuum are reached. These findings may support the notion that the key to increasing the proportion of PWH who are virally suppressed is to get them and keep them in HIV care. Appointment accompaniment and appointment coordination were the most frequently reported activities of patient navigators in the programs that had positive associations but the nature of the data did not allow us to determine if outcomes could be directly attributed to any of these or other specific navigational activities.

Few included studies reported the characteristics of patient navigators, for example, whether they were paid staff vs. volunteers, whether they met educational and other training requirements, or whether they were demographically matched with their clients. It should be noted that a few recently published studies specifically did mention whether the patient navigators were peers [10-12, 15, 20] or professionals (i.e., nurse or clinical social worker) [8, 19, 23]. All of those that utilized “professional” navigators found positive associations with HIV care continuum outcomes, but four out of the five that utilized peer navigators [11-12, 15, 20] also found positive associations. At this point, the number of studies is still too small to make a conclusive statement about effectiveness of certain types of navigators. More studies with additional focus on navigator’s characteristics will help answer important implementation questions such as whether it is equally effective to use peer vs. professional or paid vs. unpaid patient navigators, what are the most critical components of patient navigator training, and how important is it to match demographic characteristics, such as race and gender of patient navigators and clients. We also found that some patient navigation programs had navigators performing case management [11, 13, 14, 18] while other programs had a clear separation of roles between navigators and case managers [5, 9-10, 12, 15, 20, 24-25], but it is still unknown which of these models is more effective. These findings suggest that HIV patient navigation requires a standard definition for it to be implemented and evaluated consistently. In addition, very few studies provided comprehensive information about the duration/frequencies of contact between patient navigators and clients. Such information would help inform the cost and cost effectiveness of a patient navigation program, and again, is an important consideration for the field to implement this strategy to scale.

Most of the participants in the reviewed studies were PWH who were out of care or at risk for falling out of care. Few studies had specific focus on participant’s characteristics such as race, gender identity, and mode of HIV acquisition, and asked the question of whether patient navigation is a particularly important strategy among certain demographic groups. Among the ones that did, the results are inconclusive. For example, Cunningham et al., 2018 [15] found that the navigation program was most effective among the homeless while Cabral et al., 2018 [10] found a “suggestive” (non-significant) positive effect among the stably-housed. Irvine et al. [24-25] found improvements in the outcomes in almost all the subgroups including those with lower mental functioning, unstable housing, or hard drug use. Clearly, more research is warranted to tackle this question.

In the studies with any positive associations between patient navigation and HIV care continuum outcomes, we observed a considerable match between how patient navigators’ activities (e.g., providing transportation, accompanying the post-release initial primary care visit) addressed the purpose and intended outcomes (e.g., to promote post-release linkage to care) for a specific target population (e.g., PWH being released from jails). It is noteworthy that all four studies that solely targeted PWH who were released from jails [11, 15-17] reported positive findings. On the other hand, the three studies with no positive associations [10, 13, 22] specifically targeted PWH with comorbid conditions such as substance use and mental health/behavioral health issues. The patient navigators in these studies did provide many of the same activities as those with any positive associations, suggesting that PWH with comorbidities may need additional strategies to improve their outcomes.

This review is subject to some limitations. Although we conducted a comprehensive search, we may have missed studies that evaluated navigation services, but did not use the term navigation to describe their interventions or programs. To address this situation, we broadened our search terms to be more inclusive of navigation-like studies, but we may have introduced some bias by including studies that might not be considered patient navigation by some. This highlights the need for a standardized definition of patient navigation in the research literature. Another limitation is our method to determine the evidence per study outcome for each study. We used a statistically significant positive finding(s) as the evidence of a positive association when a statistical test was conducted and the direction of association when no statistical test was conducted in a given study, but we may have inflated the number of positive findings for the three studies [14, 16, 20] that did not provide statistical tests. Reflecting the state of the science in the published literature on the topic of HIV patient navigation in the U.S., this review presents a broad qualitative overview of effectiveness. As the field matures with more publications of studies with stronger study designs, meta-analysis of RCTs, for example, to determine the impact of patient navigation on HIV care continuum outcomes should be a next step. Lastly, we did have many more positive findings than null findings, indicating that there could be some publication bias of papers (i.e., null results may not have been published and thus were not captured in our review.)

This review suggests that overall, patient navigation, as is presented by the included studies, is positively associated with HIV care continuum outcomes, particularly linkage to and retention in HIV care and viral suppression. However, 65% of the studies that found any associations were of weak quality, and it is still unknown if there is a causal association between patient navigation and HIV care continuum outcomes because only three of the studies that found any positive associations used an RCT design. More research studies with rigorous designs, and that compare patient navigators with different characteristics across different patient populations are warranted in order to increase the confidence in patient navigation as an effective tool to improve HIV care continuum outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authorship: YM and LJK conceptualized the overall navigation project; YM conceptualized the systematic review and analysis with assistance from DHH, CAL and KBR, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. YM, DHH, CAL, KBR and LJK screened and coded the studies. JBD undertook the comprehensive literature search and contributed to the review methodology. All authors contributed to data interpretation and edited the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1).Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evidence of HIV treatment and viral suppression in preventing the sexual transmission of HIV. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/art/cdc-hiv-art-viral-suppression.pdf. Published December 2017. Accessed March 13, 2018.

- 2).Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the HIV care continuum. Fact Sheet. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/factsheets/cdc-hiv-care-continuum.pdf. Published July 2017. Accessed May 29, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3).National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States: updated to 2020. http://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas-update. Published July 2015. Accessed March 12, 2018.

- 4).Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. The history and principles of patient navigation. Cancer 2011; 117:3539–3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Bradford JD, Coleman S, Cunningham W. HIV system navigation: An emerging model to improve HIV care access. AIDS Patient Care and STDs 2007; 21(Suppl 1): S49–S58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Koester KA, Morewitz M, Pearson C, Weeks J, Packard R, Estes M, et al. Patient navigation facilitates medical and social services engagement among HIV-infected individuals leaving jails and returning to the community. AID Patient Care and STDs 2014; 28:82–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Effective Public Health Practice Project. Quality assessment tools for quantitative studies. Hamilton, ON: Effective Public Health Practice Project; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8).Andersen M, Hockman E, Smereck G, Tinsley J, Milfort D, Wilcox R, et al. Retaining women in HIV medical Care. Journal of Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2007; 18: 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Bove JM, Golden MR, Dhanireddy S, Harrington RD, Dombrowski JC. 2015. Outcomes of a clinic-based surveillance-informed intervention to relink patients to HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2015; 70: 262–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Cabral HJ, Davis-Plourde K, Sarango M, Fox J, Palmisano J, Rajabiun S. Peer support and the HIV continuum of care: Results from a multi-site randomized clinical trial in three urban clinics in the United States. AIDS Behav 2018; 10.1007/s10461-017-1999-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Myers JJ, Dufour MK, Koester KA, Morewitz M, Packard R, Klein KM, et al. The effects of patient navigation on the likelihood of engagement in clinical care for HIV-infected individuals leaving jail. AJPH 2018;108: 385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Shacham E, Lopez JD, Brown TM, Tippit K, Ritz A. Enhancing adherence to care in the HIHV care continuum: The Barrier Elimination And Care Navigation (BEACON) Project evaluation. AIDS Behav 2017; DOI 10.1007/s10461-017-1819-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Metsch LR, Feastser DJ, Gooden L, Matheson T, Stitzer M, Das M, et al. Effects of patient navigation with or without financial incentives on viral suppression among hospitalized patients with HIV infection and substance use. JAMA 2016; 316:156–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Wohl AR, Dierst-Davies R, Victoroff A, James S, Bendetson J, Bailey J, et al. The Navigation Program: An intervention to reengage lost patients at 7 HIV clinics in Los Angeles County, 2012-2014. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 71, e44–e50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Cunningham WE, Weiss RE, Nakazono T, Malek MA, Shoptaw SJ, Ettner SL, et al. Effectiveness of a peer navigation intervention to sustain viral suppression among HIV-positive men and transgender women release from jail. The LINK LA randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178: 542–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Jordan AO, Cohen LR, Harriman G, Teixeira PA, Cruzado-Quinones J, Venters H. Transitional care coordination in New York City Jails: Facilitating linkage to care for people with HIV returning home from Rikers Island. AIDS Behav 2013; 17:S212–S219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Teixeira PA, Jordan AO, Zaller N, Shah D, Venters H. Health outcomes for HIV-infected persons released from the New York City jail system with a transitional care-coordination plan. AJPH 2015; 105:351–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, Loughlin AM, del Rio C, Strathdee S, et al. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS 2005; 19:423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Kral AH, Lambdin BH, Comfort M, Powers C, Chen H, Lopez AM, et al. A strength-based case management intervention to reduce HIV viral load among people who use drugs. AID Behav 2018; 22:146–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Maulsby C, The Positive Charge Intervention Team, Charles V, Kingsky S, Riordan M, Jain K, et al. Positive Charge: Filling the gaps in the U.S. HIV continuum of care. AIDS Behav 2015; 19:2097–2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Wohl AR, Ludwig-Barron N, Dierst-Davies R, Kulkarni S, Bendetson J, Jordan W, et al. Project Engage: Snowball sampling and direct recruitment to identify and link hard-to-reach HIV-infected persons who are out of care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; D0I: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Brennan-Ing M, Seidel L, Rodgers L, Ernst J, Wirth D, Tietz D, et al. The impact of comprehensive case management on HIV client outcomes. PLOS One 2016; 11: e0148865 Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Asamsama OH, Squires L, Tessema A, Rae E, Hall K, Williams R, et al. HIV nurse navigation: Charting the course to improve engagement in care and HIV virologic suppression. Journal of the International Assoc of Providers of AIDS Care 2017; 16(6): 603–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Irvine MK, Chamberlin SA, Robbins RS, Myers JE, Braunstein SL, Mitts BJ, et al. Improvements in HIV care engagement and viral load suppression following enrollment in a comprehensive HIV care coordination program. CID 2015; 60:298–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Irvine MK, Chamberlin SA, Robbins RS, Kulkarni SG, Robertson MM, Nash D. Come as you are: Improving care engagement and viral load suppression among HIV care coordination clients with lower mental health functioning, unstable housing, and hard drug use. AIDS Behav 2017; 21:1572–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Cabral HJ, Tobias C, Rajabuin S, Sohler N, Cunningham C, Wong M, et al. Outreach program contacts: Do they increase the likelihood of engagement and retention in HIV primary care for hard-to-reach patients? AIDS Patient Care and STDs 2007; 21(Suppl 1): S59–S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.