Abstract

We introduce a redox-active iron complex, Fe-PyC3A, as a biochemically responsive MRI contrast agent. Switching between Fe3+-PyC3A and Fe2+-PyC3A yields a full order of magnitude relaxivity change that is field-independent between 1.4 and 11.7 T. The oxidation of Fe2+-PyC3A to Fe3+-PyC3A by hydrogen peroxide is very rapid, and we capitalized on this behavior for the molecular imaging of acute inflammation, which is characterized by elevated levels of reactive oxygen species. Injection of Fe2+-PyC3A generates strong, selective contrast enhancement of inflamed pancreatic tissue in a mouse model (caerulein/LPS model). No significant signal enhancement is observed in normal pancreatic tissue (saline-treated mice). Importantly, signal enhancement of the inflamed pancreas correlates strongly and significantly with ex vivo quantitation of the pro-inflammatory biomarker myeloperoxidase. This is the first example of using metal ion redox for the MR imaging of pathologic change in vivo. Redox-active Fe3+/2+ complexes represent a new design paradigm for biochemically responsive MRI contrast agents.

INTRODUCTION

Biochemically specific MRI contrast agents modulate the MR signal in the presence of a specific biochemical signature, offering the possibility for noninvasive detection, quantification, and mapping of pathologic change at the molecular level.1–3 The capability to visualize biochemical change with MRI could enable differential diagnoses, therapeutic planning, and the monitoring of recovery without subjecting patients to invasive biopsy or imaging that requires ionizing radiation. As healthcare paradigms shift to increasingly personalized care, medical imaging technology must deliver information with increasing molecular specificity. Biochemically specific MRI contrast agents offer an attractive solution to this unmet clinical need.

An ideal biochemically specific contrast agent will provide positive signal enhancement in the presence of a specific biochemical target but will generate little to no signal in the surrounding tissues where the biochemical target is less abundant. One approach is to develop “activatable” contrast agents that modulate the MR signal in response to biochemical stimulation. For agents that modulate signal based on relaxation, this involves biochemically triggered changes in the hydration number,4–6 the rotational correlation time,7–9 or paramagnetism.10–12 For agents based on chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST), the exchange rate or chemical shift of the exchangeable hydrogen is modulated.13,14 For agents detected by magnetic resonance spectroscopy, changes in the relaxation times or chemical shift of the observed nuclei are detected.15,16 A large number of biochemically responsive agents have been proposed over the last two decades,17,18 such as agents that respond to enzymatic activity,4,19 pH change,5,20,21 metal ion or neurotransmitter flux,22–25 changes in redox homeostasis,3,12,16,26,27 and reactive oxygen species (ROS).6,8,15 However, very few biochemically activated agents have been shown to be effective in vivo, and none have been translated to human clinical trials.

For an activatable agent to be effective in vivo, a number of design considerations must be taken into account: (1) the agent must be present at high enough concentration to detect the signal change. CEST and chemical shift agents typically require millimolar concentrations which are difficult to achieve in many tissues, while relaxation agents require at least micromolar concentrations.17,28 (2) The change in signal between the “ off” and activated “ on” states should be as large as possible to detect activation over the background signal. (3) For relaxation agents, relaxivity and concentration are correlated, so a change in signal could be due to an increase in relaxivity (activation) or an increase in local concentration (e.g., due to the enhanced permeability of diseased tissue). Very low relaxivity of the preactivated agent is required to minimize contamination of the MR signal with contributions from the agent in the “off” state. This is not possible with Gd-based relaxation agents which have high relaxivity prior to activation and typically provide only a small percentage relaxivity increase in the presence of biochemically relevant levels of stimuli.17 (4) The kinetics of activation must be fast compared to the biological half-life of the agent and the time scale of the imaging study. (5) The contrast agent must be stable in vivo with respect to metabolism and degradation in both the inactivated and activated states. (6) The contrast agent must reach its target in vivo at sufficient concentration for detection. (7) The agent must be nontoxic.

Complexes of redox-active metal ions offer an attractive approach to developing biochemically responsive relaxation agents. Different metal oxidation states can possess distinct and disparate structural preferences and paramagnetic properties. As a result, oxidation state change can profoundly impact r1 . For example, it has been demonstrated that a large redox activatable r1 change can be achieved with rationally designed complexes of Eu3+/2+ and Mn3+/2+.10,11,29–34 These agents provide little or no MR signal enhancement in the Eu3+ or Mn3+ “ off” states but provide relaxivity comparable to that of Gd3+ complexes in the Eu2+ or Mn2+ “ on” states. For Eu3+/2+ agents, it is challenging to match the redox potentials for the detection of biochemical redox.29 It is difficult to stabilize Eu2+ outside of anaerobic handling conditions, and we are unaware of any Eu2+ agents that do not instantaneously and irreversibly stabilize Eu3+ upon intravenous injection.35 However, it has been shown that direct, intratumural injection of an Eu2+ agent can provide persistent signal enhancement at the injection site.31 Mn3+/2+ interchange can be mediated by thiols and ROS,33 but no single ligand supports both oxidation states in physiologic milieu. Our laboratory addressed this shortcoming by developing a Janus ligand that isomerizes between Mn3+ and Mn2+ binding motifs upon Mn redox.11

We hypothesized that redox-active Fe complexes could provide an effective and straightforward approach to developing biochemically responsive contrast agents. Complexes of high-spin Fe3+ are effective MRI contrast agents because of the five unpaired electrons and symmetric ground state electronic configuration and can be detected at the micromolar levels achieved using doses that are given clinically for contrast agents.36 On the other hand, we expect that Fe2+ complexes will be weak relaxation agents regardless of the spin configuration. Low-spin Fe2+ is diamagnetic. The few reported relaxometric analyses of high-spin Fe2+ are consistent with a T1 -relaxation mechanism that is severely limited by a fast electron spin relaxation.37,38 We hypothesized that the change in relaxivity between the Fe2+ and Fe3+ oxidation states would be so large that no signal change would be detected in vivo with a standard dose of the Fe2+ complex, but activation to the Fe3+ complex would result in a detectable signal.

Here we describe a redox-active Fe complex, Fe-PyC3A, as an ROS activated contrast agent that is capable of detecting tissue inflammation in vivo. Inflammation is an important pathophysiological component of many diseases, but the noninvasive detection of inflammation in internal organs can be challenging. Clinical imaging of inflammation focuses on the detection of structural and physiological changes such as edema or endothelial breakdown, but these changes are not visible in all inflammation and provide no information pertaining to the biochemical underpinnings of the disease.39 ROS imaging has been proposed as a biomarker to detect and quantify acute or chronically reactivated inflammation.15,40–42 Proinflammatory neutrophils secrete high levels of ROS via respiratory burst,43 and the resultant oxidizing microenvironment provides a unique biochemical signature that can be targeted and potentially quantified with molecular imaging. The capability to image and quantify ROS could enable noninvasive detection and differential diagnoses of interstitial edematous vs severe necrotizing pancreatitis,44–46 benign nonalcoholic fatty liver vs progressive non-alcoholic steatohepatitis,47 or inflammation vs tumor regrowth during cancer treatment,48 to name a few examples.

Below we demonstrate how Fe-PyC3A fulfills the design criteria requisite of an effective biochemically responsive contrast agent and enables specific detection of the inflammatory response in vivo in a mouse model of acute pancreatitis using noninvasive MRI.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design and Synthesis.

Appropriate ligand design will enable complexes that (1) have a coordinated, fast exchanging water co-ligand in the Fe3+ complex to ensure high relaxivity, (2) undergo rapid oxidation or reduction in response to biological oxidants or reductants, and (3) are chemically stable with respect to dissociation or reaction with endogenous metals or chelators.

On the basis of these criteria, we posited that Fe-PyC3A would provide an ideal prototype for a redox-activated Fe contrast agent (Chart 1). Acyclic hexadentate ligands such as EDTA and CDTA (Figure S1) are known to form ternary complexes with high-spin Fe3+ and a rapidly exchanging water co-ligand, enabling efficient T1 relaxation.36,49 On the basis of previously reported Fe complexes of amino/carboxylate ligands, we expected that the PyC3A ligand would support both Fe2+ and Fe3+.50–52 Our prior experience with Mn2+-PyC3A demonstrated that the PyC3A ligand is capable of forming transition-metal complexes that are kinetically inert with respect to metal release and are also resistant to metabolic degradation in vivo.53–55 Given the increased inertness and stability of high-spin Fe2+ relative to Mn2+ , we expected that the Fe2+-PyC3A complex would also be inert with respect to metal ion dissociation or metabolism in vivo.

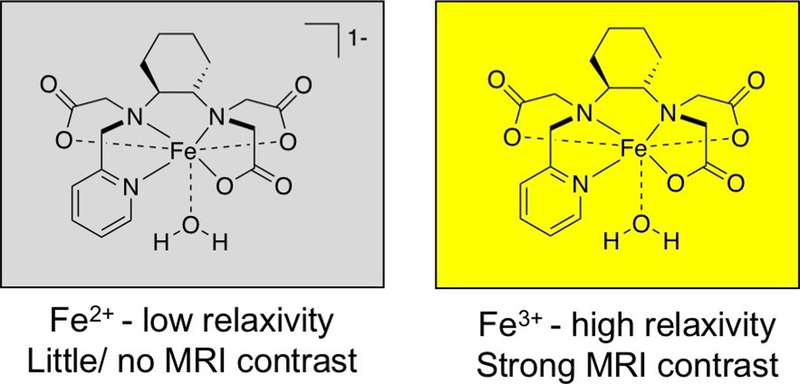

Chart 1.

Rational Design of Fe-PyC3A as a Redox-Activated MRI Contrast Agent. The Design Premise is That Fe2+ is a Very Ineffective T1 Relaxation Agent but High-Spin Fe3+ is a Potent T1 Relaxation Agent.

Fe3+-PyC3A was synthesized by combining 1 mol equiv of FeCl3 and the previously reported PyC3A ligand54 and adjusting the pH to 7.0. Pure complex was isolated after removing inorganic salts by preparative RP-HPLC (Figure S2). Fe2+ -PyC3A is metastable under aerobic conditions and oxidizes to the Fe3+ complex over the course of hours, which precluded the isolation of the pure compound (Figure S3). Instead, Fe2+ -PyC3A is prepared in situ either by the addition of FeCl2 to ligand in pH 7.4 buffer or by reduction of the Fe3+ complex by ascorbic acid (Figure S4).

Fe3+-PyC3A and Fe2+-PyC3A Are Strong and Weak MRI Contrast Agents, Respectively.

Relaxivity measurements recorded in pH 7.4 Tris buffer at 1.4, 4.7, and 11.7 T demonstrate an order of magnitude r1 difference between Fe3+- PyC3A and Fe2+-PyC3A (Table 1). As expected for a fast tumbling complex with a relaxivity activation mechanism that depends on oxidation state change, the r1Fe(3+) /r1Fe(2+) ratio is largely field-independent between 1.4 and 11.7 T. The 10- to 15-fold increase in r1 upon activation greatly exceeds what has been reported for activatable Gd-based relaxation agents within this range of field strengths. The Gd based relaxation agents that provide the greatest relaxivity change do so by protein binding or polymerization upon activation. This mechanism can provide a large (but not 10-fold) relaxivity increase at 0.47 T,7–9 but the increase in Gd relaxivity becomes less pronounced at stronger field strengths and is nearly entirely diminished by 3 T,56 which is the current state of the art for clinical MR imaging.

Table 1.

Relaxivity of Fe3+- and Fe2+-PyC3A Recorded in pH 7.4 Tris Buffer at 1.4, 4.7, and 11.7 T.

|

r1 Fe3+-PyC3A (mM−1s−1) |

r1 Fe2+-PyC3A (mM−1s−1) |

r1 Fe3+/ r1Fe2+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.4Ta | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 10.0 |

| 4.7Tb | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 13.3 |

| 11.7Ta | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 14.5 |

Recorded at 37 °C

Recorded at room temperature.

The relaxivity of Fe3+-PyC3A is comparable to values reported for Fe3+ -CDTA (r1 = 2.0 mM−1s−1 , 0.94 T, 25°)36 and Mn2+-PyC3A (r1 = 2.1 mM−1 s−1 , 1.4 T, 37 ° C),54 both of which have been demonstrated to be highly effective contrast agents for in vivo MR imaging.36,53 The comparable relaxivities of these S = 5/2 complexes of similar molecular weight imply the presence of a coordinated water ligand for Fe3+ -PyC3A. The r1 values recorded between pH 2 and 7 (1.7 to 1.8 mM−1s−1) are consistent with a q = 1 Fe3+ complex, but the r1 drops below 1.0 mM−1 s−1 as the pH is raised above 7.5 (Figure 1 A). On the basis of the pH dependent speciation of structurally similar Fe3+ complexes,49,57 deprotonation of the water coligand and slow exchange of the coordinated hydroxo ligand is the most likely explanation for the observed pH dependence on r1.

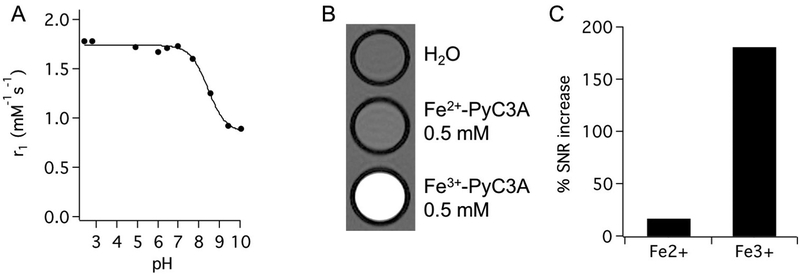

Figure 1.

(A) Relaxivity of Fe3+-PyC3A at pH 7.4 is consistent with the presence of a fast exchanging water co-ligand. A pKa of 8.5 for the water coligand was estimated from the pH dependence on Fe3+-PyC3A relaxivity at 37 °C. (B) T1-weighted 2D gradient echo images (TR = 125 ms, TE = 2.96 ms, FA = 60°) of phantoms containing neat water, 0.5 mM Fe2+-PyC3A, and 0.5 mM Fe3+-PyC3A at pH 7.4, room temperature, and 4.7 T. (C) The Fe2+-PyC3A containing sample provides a 17% increase in the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) relative to the water sample, whereas the Fe3+-PyC3A-containing solution provides a 181% SNR increase.

Fe2+ -PyC3A, on the other hand, is such a weak relaxation agent that switching between Fe2+- and Fe3+-PyC3A provides a true “turn off /turn on” effect. A comparison of T1 weighted images of phantoms containing water, 0.5 mM Fe2+-PyC3A, and 0.5 mM Fe3+-PyC3A is shown in Figure 1 B. Despite the high concentration, the Fe2+-PyC3A-containing sample provides only a 17% increase in the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) relative to the water sample, whereas the Fe3+ PyC3A containing solution provides a 181% SNR increase (Figure 1 C). The contrast between the Fe3+-PyC3A and Fe2+-PyC3A containing solutions is striking.

PyC3A Forms a Ternary Complex with High-Spin Fe3+ and a Rapidly Exchanging Water Co-ligand.

Bulk magnetic susceptibility measurements of Fe2+-PyC3A and Fe3+-PyC3A by the Evans’ NMR method at 25 °C yield μeff values of 4.9 and 5.7 effective Bohr magnetons, respectively, which are consistent with high-spin Fe2+ (S = 2) and high-spin Fe3+ (S = 5/2).58,59

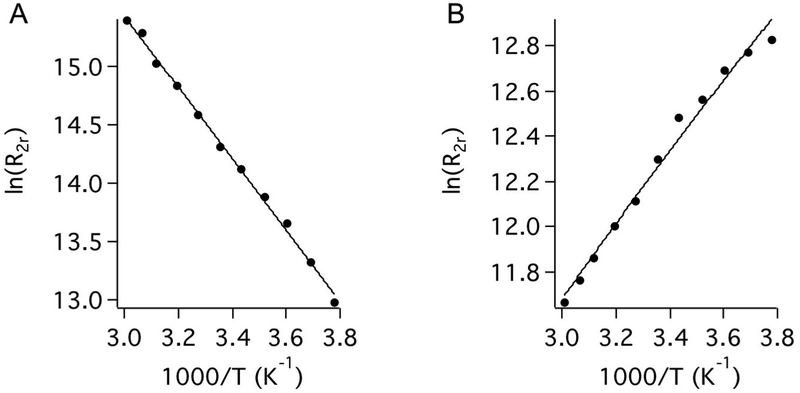

The interactions between Fe3+-PyC3A and Fe2+-PyC3A and bulk water were interrogated by measuring the T2 relaxation time and chemical shift of solvent H217O in the presence and absence of the Fe complex (Figure 2). The reduced relaxation rate, R2r, was calculated as (1/T2Fe − 1/T20)/Pm, where superscripts Fe and 0 denote the presence and absence of the iron complex and Pm is the mole fraction of water coordinated to the Fe complex, and here we assume a hydration number (q) of 1 for the water co-ligand. The data were fit to the Swift− Connick equations describing two-site exchange60 (SI). The temperature dependence on H217O relaxation in the presence of Fe3+-PyC3A is shown in Figure 2 A. Here, R2r increases with increasing temperature and does not reach a maximum over the temperature range studied. This is the so-called slow exchange condition, and here R2r = kex , the water exchange rate at each temperature. Fitting this data to the Eyring equation gives the water exchange rate at 37 ° C (kex310) and the activation enthalpy for water exchange (ΔH⧧) (Table 2 ). Although under the “slow exchange” condition with respect to T2 relaxation of H217O, kex310 = 2.5 × 106 s−1 is still quite fast and enables catalytic T1 relaxation of water 1H. Water exchange at Fe3+ -PyC3A is comparable to that for the commercially used Gd complexes.62 On the other hand, the Fe2+-PyC3A complex is in “fast exchange” over the temperature range studied. Under these conditions, R2r = (Δωm)2 /kex , where Δωm is the 17O chemical shift of the coordinated water ligand. Under fast exchange conditions, the 17O chemical shift is directly related to the Fe−17O hyperfine coupling constant, A/h, which was estimated by recording Δωm as a function of [Fe2+-PyC3A] at 40 °C.63 The chemical shift data for Fe2+-PyC3A yielded a hyperfine coupling constant of A/h = 6.8 MHz, which was in reasonable agreement with that reported for the Fe2+ -aqua ion and structurally related Fe2+ complexes50–52,64 (Table S1 ). With A/h in hand, fits to the temperature-dependent R2r data yielded kex310 = 2.8 × 108 s−1, which is 2 orders of magnitude higher than for the sister Fe3+ complex. The slower exchange rate for the Fe3+ oxidation state might be expected because of the higher positive charge on the ion.

Figure 2.

Reduced relaxation rate (R2r) for H217O as a function of temperature for Fe3+-PyC3A (A) and Fe2+-PyC3A (B) measured at pH 7.0. The solid lines are fits to the data using the Swift−Connick equations.

Table 2.

Fitting the Temperature-Dependent T2 Relaxation of Bulk H217O Data with the Swift-Connick Equations Yields the Number of Water Co-ligands (q) and Corresponding Water Exchange Parametersa Recorded for Fe3+ -PyC3A and Fe2+-PyC3A.

| q |

A/h (MHz) |

kex310 × 10−6 (s−1) |

τm310 (ns) |

ΔH‡

(kJ/mol) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3+-PyC3A | 1 | N/Da | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 394 ± 6 | 23.2 ± 0.9 |

| Fe2+-PyC3A | 1 | 6.8 | 277 ± 5 | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 5.9 ± 0.5 |

A/h is the Fe−17O hyperfine coupling constant, kex310 is the rate of water co-ligand exchange at 37 °C, and τm310 is the mean residency time of the water co-ligand at 37 °C. A/h cannot be determined for complexes that are observed solely in the slow exchange regime. See the SI.

Fe3+/2+ Interchange Is Mediated by Biochemical Processes.

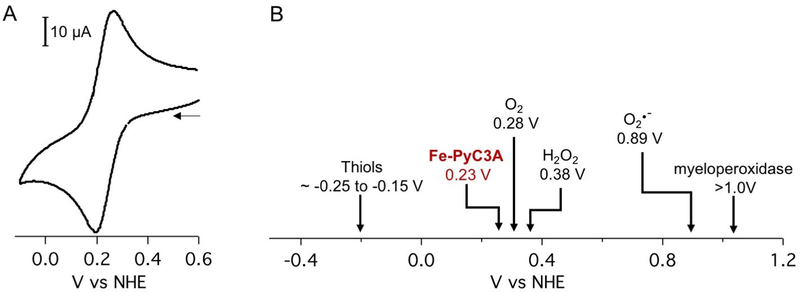

Cyclic voltammetry measurements demonstrate that Fe3+/2+-PyC3A possesses a reversible redox couple with a midpoint of 0.230 V vs NHE (Figure 3A). The Fe3+/2+ reduction and oxidation potentials are poised within range for reaction with ROS generated during oxidative stress (i.e., H2O2, Ered = 0.38 V vs NHE61) as well as reduction by thiols responsible for governing the tissue redox status (i.e., cysteine/ cysteine disulfide, E1/2 cited between −150 and 250 mV vs NHE) (Figure 3B).65

Figure 3.

(A) Fe-PyC3A has a redox potential of 230 mV versus NHE. Glassy carbon working electrode, Pt counter electrode, 0.5 M KNO3. (B) The Fe3+/2+ redox couple lies in a range that should result in oxidation by reactive oxygen species generated during oxidative stress as well as reduction by thiols responsible for governing the tissue redox status.61

To test the capability of Fe3+/2+-PyC3A to respond to biochemical reduction and oxidation, we evaluated the reactivity of the Fe3+ and Fe2+ chelates in the presence of L-cysteine and H2O2, respectively. Reaction progress was tracked spectrophotometrically by measuring the absorbance at 310 nm (ε = 5430 and 1620 M−1s−1 for Fe3+-PyC3A and Fe2+-PyC3A, respectively (Figure S6)).

Fe3+-PyC3A is rapidly reduced by L-cysteine. The kinetics of cysteine-mediated reduction were interrogated by monitoring the reaction rates under conditions of varied Fe3+ PyC3A (0.08, 0.10, 0.12, 0.14 mM) and cysteine (2.0, 4.0, and 8.0 mM) concentration at pH 7.4 and 37 °C (Figure S7). Based on the [Fe3+-PyC3A] and [L-Cys] dependences on the initial rates, the reduction obeys a second-order rate law k[Fe3+-PyC3A][L-Cys], with k = 1.5 ± 0.3 M−1s−1. Based on the Fe3+/2+ redox potential and the observation that Fe3+-PyC3A can be rapidly reduced by thiols, we expect that the low relaxivity Fe2+-PyC3A complex will predominate under conditions of normal metabolism.66

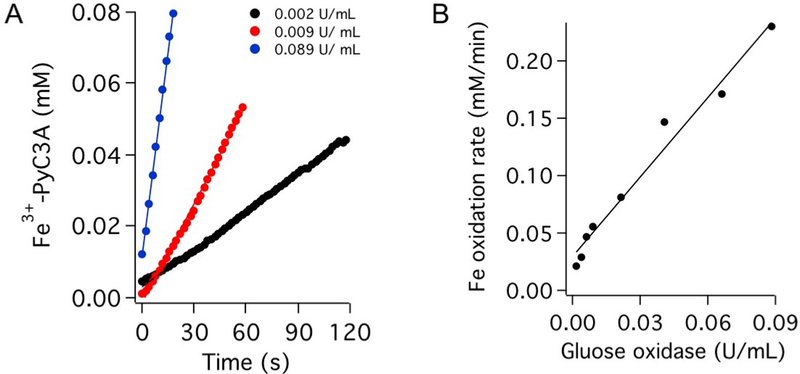

Fe2+-PyC3A is rapidly oxidized to the corresponding Fe3+ complex by H2O2. The reaction proceeds too fast for determination of the rate law. We instead measured the rate of conversion in the presence of H2O2 enzymatically generated via the glucose/glucose oxidase reaction. (See the Supporting Information for details.) Oxidation kinetics were recorded under conditions of glucose oxidase activity levels ranging from 0.02 to 0.1 U/mL (Figure 4). The rate of oxidation to Fe3+-PyC3A is strongly correlated with glucose oxidase activity (Figure 4 B).

Figure 4.

(A) Oxidation to Fe3+-PyC3A monitored via absorbance at 310 nm in the presence of varying activity levels of the H2O2-producing glucose/glucose oxidase reaction. (B) Rate of oxidation to Fe3+-PyC3A correlates linearly with the rate of enzymatic H2O2 production.

HPLC analysis of L-Cys and H2O2 treated samples confirms clean, biochemically mediated conversion between oxidation states without the formation of degradation byproducts (Figures S8 and S9A). Fe2+-PyC3A to Fe3+-PyC3A conversion also occurs cleanly in the presence of the ROS potentiating enzyme horseradish peroxidase, which amplifies the reactivity of H2O2 by the formation of ferryl heme (Figure S9B).

PyC3A Supports Stable Complexes of Both Fe3+ and Fe2+.

The thermodynamic stability of Fe3+-PyC3A was determined by a direct competition reaction with EDTA (log Kcond = 22.2 at pH 7.4 for Fe3+-EDTA).67 Quantification of Fe3+-PyC3A vs free PyC3A under equilibrium conditions at pH 7.4 yielded log Kcond = 23.2 ± 1.8 (Figure S10, eqs S12 and S13). log Kcond = 15.0 ± 1.8 at pH 7.4 was estimated for Fe2+-PyC3A from the Fe3+-PyC3A stability constant and the redox potential using a modified form of the Nernst equation, as described previously68 (eq S14).

Transmetalation with Zn2+ is the most commonly invoked mechanism for metal ion dissociation from Gd3+ and Mn2+ contrast agents.17 Zn2+ transmetalation is less of a concern for Fe3+-PyC3A, as structurally similar polyaminopolycarboxylate ligands such as EDTA typically bind Fe3+ with several orders of magnitude greater affinity than for Zn2+. Consistent with this expectation, Fe3+-PyC3A withstands a 20 mol equiv challenge at pH 4.0 with <0.4% transmetalation occurring over 72 h (Figure S11).

The Zn2+-mediated displacement of Fe2+ is a greater liability. On the basis of the Irving−Williams series, we expect the Zn2+-PyC3A complex to be more thermodynamically stable. Fe2+ is displaced from Fe2+-PyC3A by Zn2+, but the complex is kinetically inert. Under a strong challenge (20 mol equiv Zn2+ at pH 6.0, RT), transmetalation with Zn2+ occurs 18 times more slowly than the rate observed for Mn2+-PyC3A (dissociation half-life = 27 h vs 1.5 h for Fe2+-PyC3A and Mn2+-PyC3A, respectively, Figure S12). Mn2+-PyC3A has been demonstrated to be largely resistant to Mn2+ dissociation invivo,53,54 and given the greater kinetic inertness of Fe2+-PyC3A, we expect that Fe2+-PyC3A will also be inert to dissociation in vivo.

Intravenously administered Fe complexes must also compete with endogenous Fe binding ligands. PyC3A binds Fe3+ with only modestly stronger affinity than that reported for the Fe3+ transporter protein transferrin (log Kcond = 20.7 and 19.4 for the two Fe3+ binding sites of human transferrin at pH 7.4).69 Transferrin is present in blood plasma in the 30 μ M range and represents a potential cause of Fe3+-PyC3A dechelation.70 We measured the rate of Fe3+ transfer from Fe3+-PyC3A to apotransferrin over the course of 24 h by monitoring the iron to transferrin charge transfer transition at 465 nm. Under our experimental conditions (0.1 mM Fe3+ -PyC3A, 0.1 mM apotransferrin, 50 mM NaHCO3 , pH 7.4,) Fe3+ transfer occurs with kobs = (8.66 ± 1.33) × 10−4 min−1 , resulting in <3% Fe3+ transchelation occurring over the course of 24 h (Figure S13). This rate of transchelation to transferrin occurs much more slowly relative to the rate at which small-molecule contrast agents are typically eliminated. Low-molecular-weight contrast agents are nearly entirely eliminated from human patients within hours. More relevant to the imaging performed in this study, the elimination of small-molecule contrast agents from mice occurs much faster than the measured rate of Fe3+ loss to transferrin. For example, the Mn2+-PyC3A elimination half-life (t1/2 = 7.8 min)54 is 2 orders of magnitude shorter than the half-life for Fe3+ loss recorded in vitro (t1/2 = 800 ± 120 min). Transferrin competition with the Fe2+ chelate poses less of a threat, as PyC3A binds Fe2+ with nearly a trillion times greater stability than transferrin (log Kcond = 4.2 and 3.1 for transferrin Fe2+ binding).71

Fe3+-PyC3A and Fe2+-PyC3A Are Strong and Weak Contrast Agents in Vivo.

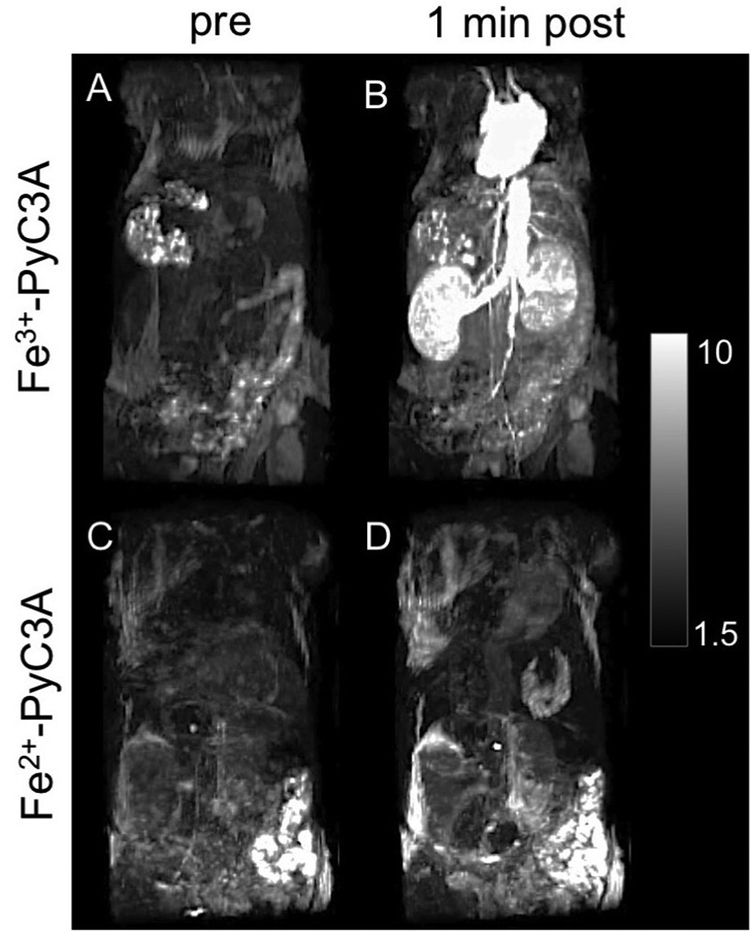

The in vivo signal-generating properties of Fe3+-PyC3A and Fe2+-PyC3A were compared in mice. Fe2+-PyC3A was formulated by the addition of 0.5 mol equiv ascorbic acid prior to injection. Figure 5 A– D shows maximum intensity projections of T1-weighted images of the thorax and abdomen recorded prior to (A, C) and 1 min after (B, D) a 0.2 mmol/kg injection of either Fe3+-PyC3A (A,B) or Fe2+-PyC3A (C, D). The heart, aorta, renal arteries, and kidneys are rendered conspicuously hyperintense after injection of the Fe3+ complex. On the other hand, signal enhancement is substantially weaker at 1 min and subsequent time points following the injection of the Fe2+ complex.

Figure 5.

Maximum intensity projections of mice prior to and 1 min after injection of 0.2 mmol/kg Fe3+-PyC3A (A, B) or 0.2 mmol/kg Fe2+-PyC3A (C, D). Strong signal enhancement of the blood pool is observed 1 min after injection of Fe3+-PyC3A, whereas Fe2+-PyC3A provides virtually no signal enhancement. The scale bar represents the signal intensity.

Fe-PyC3A Enables a Strong, Selective Contrast Enhancement of Acute Inflammation.

Fe-PyC3A embodies several criteria that are requisite of an effective contrast agent for MR imaging of ROS/oxidative stress: (1) a very large relaxivity change upon switching between the Fe2+ and Fe3+ oxidation states, (2) the low-signal-enhancing Fe2+-PyC3A will persist under conditions of normal metabolism, (3) Fe2+-PyC3A is rapidly converted to high-relaxivity Fe3+-PyC3A in the presence of ROS and we expect the rate of H2O2-mediated oxidation to exceed the rate of any competing process driving reduction back to Fe2+-PyC3A, and (4) in vitro measurements indicate that the complex is robust against oxidative degradation, Zn2+ displacement, and transchelation with endogenous Fe chelators encountered in blood plasma.

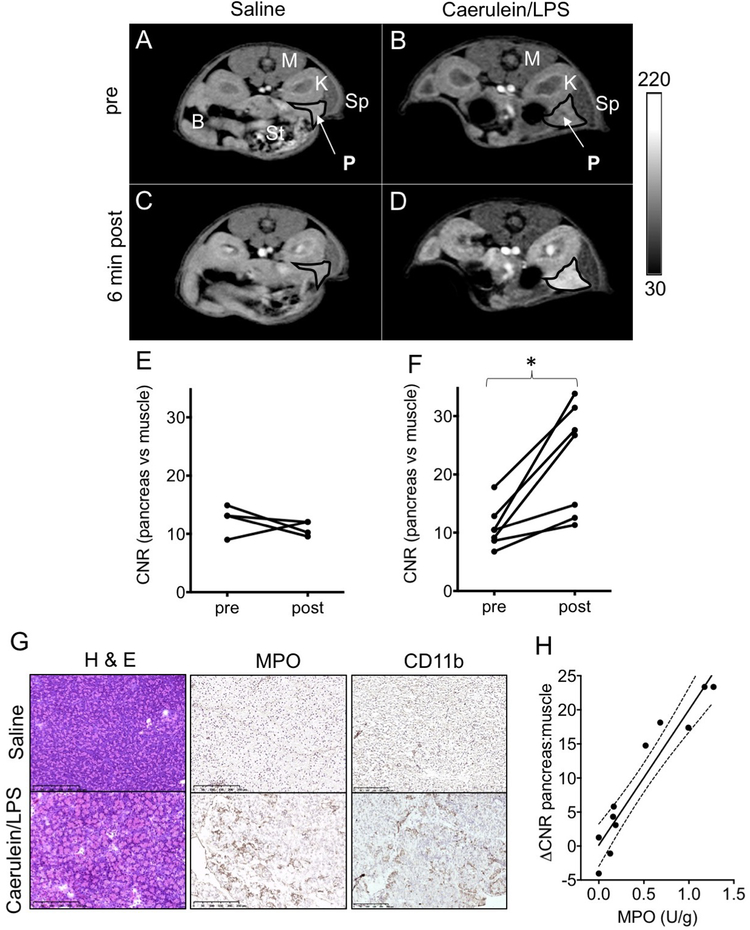

We next evaluated the capability of Fe-PyC3A to detect ROS production in a murine model of acute pancreatitis. Acutely inflamed tissue is characterized by a highly oxidizing microenvironment that results from ROS secretion by infiltrating neutrophils.43,72 We used an established model of acute pancreatitis.73,74 Mild edematous pancreatic inflammation was pharmacologically induced via six hourly intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of caerulein (50 μ g/kg in saline) initiated 18 h prior to imaging. Three hours before imaging, the mice were treated with an i.p. injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 10 mg/kg in saline) to further stimulate neutrophil activation and ROS secretion. Mice were imaged with a 2D T1-weighted gradient echo sequence prior to and out to 30 min after intravenous injection of a 0.2 mmol/kg dose of Fe2+-PyC3A. We compared pancreas-to-muscle contrast-to-noise ratios (CNR) recorded before and 6 min after intravenous contrast agent administration in mice experiencing acute pancreatitis (caerulein/ LPS treatement) and in saline-treated control mice. Another set of caerulein/LPS-treated mice were treated with Mn2+-PyC3A as a nonresponsive, negative control. Mn2+-PyC3A is isostructural and possesses charge identical to that of Fe2+-PyC3A but does not undergo r1 change in the presence of ROS (Figure S14). Mn2+-PyC3A was administered at equal volume but at a formulation that was “ T1 matched” to the Fe2+-PyC3A dose (0.02 mmol/kg total dose Mn2+ -PyC3A).54

Injection of Fe2+ -PyC3A does not provide significant signal enhancement of the pancreas in the saline-treated mice but provides strong, selective signal enhancement of the inflamed pancreas (Figure 6 A– D). Prior to injection, the pancreas is almost isointense with the neighboring kidney (A, B). The pancreas and kidney are not significantly enhanced by Fe2+-PyC3A and remain isointense 6 min after injection of Fe2+-PyC3A into the saline-treated mice (C, E). The kidney pelvis is enhanced due to a high concentration of Fe complex that collects en route to urinary excretion, consistent with the large dose of contrast agent. On the other hand, the pancreas of the caerulein/LPS-treated mouse is strongly enhanced relative to the neighboring kidney 6 min after injection (D) and is significantly enhanced vs the preinjection scan (F). Fe-PyC3A enhancement of the inflamed pancreas peaks between 6 and 12 min after injection but diminishes to near baseline levels within 30 min, consistent with washout of the low-molecular weight contrast agent (Figures S15 and S16 ). No significant pancreatic enhancement is observed following treatment of caerulein/LPS-treated mice with the “ T1 matched” dose of Mn2+-PyC3A (Figure S17). This control experiment further supports the oxidation of Fe2+-PyC3A to Fe3+-PyC3A as the mechanism of pancreatic enhancement in the caerulein/LPStreated mice. Coronal images are also shown in Figure S18. At later time points after Fe2+-PyC3A injection, strong signal enhancement in the urinary bladder and bowel are observed, consistent with excretion of the complex (Figure S19).

Figure 6.

T1-weighted 2D axial images of saline and caerulein/LPS-treated mice recorded prior to and 6 min after injection of 0.2 mmol/kg Fe2+-PyC3A. Organs are labeled as follows: P, pancreas; Sp, spleen; K, kidney; M, muscle; St, stomach; and B, bowel. Note that the pancreas and neighboring kidney are virtually isointense prior to contrast agent injection (A, B). After injection of Fe2+-PyC3A to saline-treated mice, the pancreas and kidney remain isointense (C), but the pancreas is strongly and selectively enhanced after the injection of Fe2+-PyC3A to caerulein/ LPS-treated mice (D). The change in pancreas vs muscle CNR measured before contrast agent injection compared to 6 min after contrast agent injection is not significant for saline-treated mice receiving Fe2+-PyC3A, CNRpre = 13 ± 2.5, CNRpost = 11 ± 1.3, N = 4, P = 0.43, paired t-test (E), but significant enhancement is observed in caerulein/LPS-treated mice receiving Fe2+-PyC3A, CNRpre = 11 ± 3.6, CNRpost = 23 ± 9.4, N = 7, P = 0.0068, paired t-test (F). (G) Histopathologic analysis of pancreatic tissue from saline-treated control and caerulean/LPS-treated mice. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining confirms pancreatic inflammation. Immunohistochemical staining for myeloperoxidase (MPO) and CD11b confirms elevated levels of MPO and elevated leukocyte content in the acutely inflamed tissue. (H) Spectrophotometric quantitation of pancreatic MPO correlates strongly and significantly with the peak ΔCNR recorded after Fe2+-PyC3A injection, N = 11, r = 0.95, P < 0.0001.

To confirm that strong, selective Fe-PyC3A enhancement of pancreatic tissue is due to oxidation by neutrophil-generated ROS, pancreatic tissue was harvested after imaging and analyzed for inflammation by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, for myeloperoxidase (MPO) by immunohistochemical staining, and by spectrophotometric quantitation of MPO activity levels (guaiacol assay). MPO is secreted by activated neutrophils and serves to convert respiration-derived ROS into more deleterious oxidants such as ferryl heme and hypochlorous acid.75 MPO activity levels are known to correlate strongly with activated neutrophil content and oxidative stress.40,41,47 H&E staining confirmed inflammation in the pancreatic tissue of caeulein/LPS-treated mice. Saline and cearulein/LPS-treated mice stained negative and positive for MPO, respectively (Figure 6 G). Spectrophotometric quantitation reveals a significant, 10-fold increase in pancreatic MPO activity levels for caerulein/LPS-treated mice (0.71 ± 0.46 U/g) compared to that for saline-treated mice (0.078 ± 0.094 U/g), P = 0.0262, two-sided t-test. The MPO activity levels correlate strongly with peak recorded pancreas vs muscle ΔCNR, r = 0.95, P < 0.0001 (Figure 6 H).

CONCLUSIONS

We demonstrated that the redox-active Fe complex, Fe3+/2+-PyC3A, is a very effective contrast agent for molecular MR imaging of oxidative microenvironments. The Fe2+ complex possesses such low relaxivity that signal change is barely perceptible at concentrations as high as 0.5 mM, whereas Fe3+-PyC3A possesses an order of magnitude greater relaxivity and is a very strong contrast agent. The “ off /on” effect achieved by changing oxidation states far supersedes that possible with Gd-based relaxation agents. The effect is field-independent over a wide range, 1.4 to 11.7 T. Fe-PyC3A can rapidly toggle between the Fe2+ and Fe3+ oxidation states in response to L-Cys and H2O2, respectively. Cyclic voltammetry measurements and in vivo imaging data indicate that the Fe2+ oxidation state is favored under conditions of normal metabolism but that the complex is rapidly converted to the high relaxivity Fe3+ oxidation state in the presence of reactive oxygen species. We demonstrated the capability of Fe-PyC3A to detect oxidative stress in a murine model of pancreatitis. Fe2+-PyC3A provided strong, selective contrast enhancement of inflamed pancreatic tissue as a result of ROS mediated oxidation to the high relaxivity Fe3+ oxidation state. Pancreas vs muscle ΔCNR correlates positively and significantly with ex vivo quantification of the proinflammatory biomarker MPO.

To our knowledge, the Fe-PyC3A-enhanced detection of pancreatic inflammation demonstrated in this article is the first example of using metal ion redox to visualize pathologic change with MRI. Redox-active Fe complexes offer a new paradigm for the design of biochemically responsive MRI contrast agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K25HL128899) and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (R01EB009062 and R21EB022804) and by instrumentation funded by the National Center for Research Resources and the Office of the Director (P41RR014075, S10RR023385, and S10OD010650).

Footnotes

Supporting Information.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.9b00603 .

Experimental details, synthesis procedures, compound characterization, structures not depicted in the main text, additional spectra, HPLC

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): P.C. and E.M.G. are co-founders and hold equity in Reveal Pharmaceuticals, a company that is developing Mn-based MRI contrast agents and has a licensing agreement for the patents covering Mn2+ -PyC3A.

REFERENCES

- (1).Angelovski G What We Can Really Do with Bioresponsive MRI Contrast Agents. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55 (25), 7038–7046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).De Leon-Rodriguez LM; Lubag AJM; Malloy CR; Martinez GV; Gillies RJ; Sherry AD Responsive MRI Agents for Sensing Metabolism in Vivo. Acc. Chem. Res 2009, 42 (7), 948–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Du K; Waters EA; Harris TD Ratiometric quantitation of redox status with a molecular Fe-2 magnetic resonance probe. Chemical Science 2017, 8 (6), 4424–4430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Moats RA; Fraser SE; Meade TJA “Smart” Magnetic Resonance Imaging Agent That Reports on Specific Enzymatic Activity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 1997, 36 (7), 726–727. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Lowe MP; Parker D; Reany O; Aime S; Botta M; Castellano G; Gianolio E; Pagliarin R pH-Dependent Modulation of Relaxivity and Luminescence in Macrocyclic Gadolinium and Europium Complexes Based on Reversible Intramolecular Sulfonamide Ligation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123 (31), 7601–7609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Yu M; Ambrose SL; Whaley ZL; Fan S; Gorden JD; Beyers RJ; Schwartz DD; Goldsmith CR A Mononuclear Manganese(II) Complex Demonstrates a Strategy To Simultaneously Image and Treat Oxidative Stress. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 12836–12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Yu J; Martins AF; Preihs C; Jordan VC; Chirayil S; Zhao P; Wu Y; Nasr K; Kiefer GE; Sherry AD Amplifying the Sensitivity of Zinc(II) Responsive MRI Contrast Agents by Altering Water Exchange Rates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137 (44), 14173– 14179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Rodríguez E; Nilges M; Weissleder R; Chen JW Activatable Magnetic Resonance Imaging Agents for Myeloperoxidase Sensing: Mechanism of Activation, Stability, and Toxicity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 168–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Nivorozhkin AL; Kolodziej AF; Caravan P; Greenfield MT; Lauffer RB; McMurry TJ Enzyme-Activated Gd3+ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agents with a Prominent Receptor-Induced Magnetization Enhancement. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2001, 40, 2903–2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Aime S; Botta M; Gianolio E; Terreno E A p(O2)-Responsive MRI Contrast Agent Based on the Redox Switch of Manganese(ii/iii) ± Porphyrin Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2000, 39 (4), 747–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Gale EM; Jones CM; Ramsay I; Farrar CT; Caravan P A Janus Chelator Enables Biochemically Responsive MRI Contrast with Exceptional Dynamic Range. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138 (49), 15861–15864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ekanger LA; Polin LA; Shen Y; Haacke EM; Martin PD; Allen MJ A EuII Containing Cryptate as a Redox Sensor in Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Living Tissue. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2015, 54 (48), 14398–14401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Tsitovich PB; Spernyak JA; Morrow JR A redoxactivated MRI Contrast Agent that Switches between Paramagnetic and Diamagnetic States. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2013, 52, 13997–14000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ratnakar SJ; Viswanathan S; Kovacs Z; Jindal AK; Green KN; Sherry AD Europium(III) DOTA-tetraamide Complexes as Redox-Active MRI Sensors. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 5798–5800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Yu M; Bouley BS; Xie D; Enriquez JS; Que EL 19F PARASHIFT Probes for Magnetic Resonance Detection of H2O2 and Peroxidase Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140 (33), 10546–10552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Xie D; Kim S; Kohli V; Banerjee A; Yu M; Enriquez JS; Luci JJ; Que EL Hypoxia-Bioresponsive 19F MRI Probes with Improved Redox Properties and Biocompatibility. Inorg. Chem 2017, 56 (11), 6429–6437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wahsner J; Gale EM; Rodriguez-Rodriguez A; Caravan P Chemistry of MRI Contrast Agents: Current Challenges and New Frontiers. Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Hingorani DV; Bernstein AS; Pagel MD A review of responsive MRI contrast agents: 2005–2014. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2015, 10, 245–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Mizukami S; Takikawa R; Sugihara F; Hori Y; Tochio H; Wälchi M; Shirakawa M; Kikuchi K. Paramagnetic Relaxation-Based 19F MRI Probe To Detect Protease Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 794–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Woods M; Kiefer GE; Bott S; Castillo-Muzquiz A; Eshelbrenner C; Michaudet L; McMillan K; Mudigunda SDK; Ogrin D; Tircsó G; Zhang S; Zhao P; Sherry AD. Synthesis, Relaxometric and Photophysical Properties of a New pH-Responsive MRI Contrast Agent: The Effect of Other Ligating Groups on Dissociation of a p-Nitrophenolic Pendant Arm. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126 (30), 9248–9256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zhang S; Wu K; Sherry AD A Novel pH-Sensitive MRI Contrast Agent. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1999, 38 (21), 3192–3194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lee T-Y; Cai LX; Lelyveld VS; Hai A; Jasanoff A Molecular-level functional magnetic resonance imaging of dopaminergic signaling. Science 2014, 344 (6183), 533–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Esqueda AC; Ló;pez JA; Andreu-de-Riqure G; Alvarado-Monzón JC; Ratnakar SJ; Lubag AJM; Sherry AD; De Leó;n-Rodríguez LM. A New Gadolinium-Based MRI Zinc Sensor. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 11387–11391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Oukhatar F; Meme S; Meme W; Szeremeta F; Logothetis NK; Angelovski G; Toth E MRI Sensing of Neurotransmitters with a Crown Ether Appended Gd3+ Complex. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2015, 6 (2), 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Que EL; Gianolio E; Baker SL; Wong AP; Aime S; Chang CJ Copper Responsive Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast Agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131 (24), 8527–8536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Tsitovich PB; Burns PJ; McKay AM; Morrow JR Redox-activated MRI contrast agents based on lanthanide and transition metal ions. J. Inorg. Biochem 2014, 133, 143–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Tu C; Nagao R; Louie AY Multimodal Magnetic-Resonance/Optical-Imaging Contrast Agent Sensitive to NADH. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2009, 48, 6547–6551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Boros E; Gale EM; Caravan P MR imaging probes: design and applications. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44 (11), 4804–4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Seibig S; Toth E; Merbach AE Unexpected differences in the dynamics and in the nuclear and electronic relaxation properties of the isoelectronic Eu-II(DTPA)(H2O) (3-) and Gd III(DTPA)-(H2O) (2-) complexes (DTPA = diethylenetriamine pentaacetate). J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122 (24), 5822–5830. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Ekanger LA; Ali MM; Allen MJ Oxidation-responsive Eu2+/3+-liposomal contrast agent for dual-mode magnetic resonance imaging. Chem. Commun 2014, 50, 14835–14838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Gamage NDH; Mei YJ; Garcia J; Allen MJ Oxidatively Stable, Aqueous Europium(II) Complexes through Steric andElectronic Manipulation of Cryptand Coordination Chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2010, 49 (47), 8923–8925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Gale EM; Mukherjee S; Liu C; Loving GS; Caravan P Structure-redox-relaxivity relationships for redox responsive manganese- based magnetic resonance imaging probes. Inorg. Chem 2014, 53 (19), 10748–10761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Loving GS; Mukherjee S; Caravan P Redox-Activated Manganese-Based Contrast Agent. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 4623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Basal LA; Bailey MD; Romero J; Ali MM; Kurenbekova L; Yustein J; Pautler RG; Allen MJ Fluorinated EuII-based multimodal contrast agent for temperature- and redox-responsive magnetic resonance imaging. Chem. Sci 2017, 8 (12), 8345–8350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Ekanger LA; Polin LA; Shen YM; Haacke EM; Allen MJ Evaluation of Eu-II based positive contrast enhancement after intravenous, intraperitoneal, and subcutaneous injections. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2016, 11 (4), 299–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Boehm-Sturm P; Haeckel A; Hauptmann R; Mueller S; Kuhl CK; Schellenberger EA Low-Molecular-Weight Iron Chelates May Be an Alternative to Gadolinium-based Contrast Agents for T1-weighted Contrast-enhanced MR Imaging. Radiology 2018, 286 (2), 537–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Gore JC; Kang YS Measurement of radiation dose distributions by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) imaging. Phys. Med. Biol 1984, 29 (10), 1189–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Bertini I; Luchinat C NMR of Paramagnetic Substances; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 1996; Vol. 150. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Hammoud DA Molecular Imaging of Inflammation: Current Status. J. Nucl. Med 2016, 57 (8), 1161–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Su HS; Nahrendorf M; Panizzi P; Breckwoldt MO; Rodriguez E; Iwamoto Y; Aikawa E; Weissleder R; Chen JW Vasculitis: Molecular Imaging by Targeting the Inflammatory Enzyme Myeloperoxidase. Radiology 2012, 262 (1), 181–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Nahrendorf M; Sosnovik D; Chen JW; Panizzi P; Figueiredo J-L; Aikawa E; Libby P; Swirski FK; Weissleder R Activatable Magnetic Resonance Imaging Agent Reports Myeloperoxidase Activity in Healing Infarcts and Noninvasively Detects the Antiinflammatory Effects of Atorvastatin on Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Circulation 2008, 117, 1153–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Breckwoldt MO; Chen JW; Stangenberg L; Aikawa E; Rodriguez E; Qiu S; Moskowitz MA; Weissleder R Tracking the inflammatory response in stroke in vivo by sensing the enzyme myeloperoxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2008, 105 (47), 18584–18589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Mittal M; Siddiqui MR; Tran K; Reddy SP; Malik AB Reactive Oxygen Species in Inflammation and Tissue Injury. Antioxid. Redox Signaling 2014, 20 (7), 1126–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Thoeni RF The Revised Atlanta Classification of Acute Pancreatitis: Its Importance for the Radiologist and Its Effect on Treatment. Radiology 2012, 262 (3), 751–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Busireddy KK; AlObaidy M; Ramalho M; Kalubowila J; Baodong L; Santagostino I; Semelka RC Pancreatitis-imaging approach. World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiol 2014, 5 (3), 252–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Chooklin S; Pereyaslov A; Bihalskyy I Pathogenic role of myeloperoxidase in acute pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis. Int 2009, 8 (6), 627–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Pulli B; Wojtkiewicz G; Iwamoto Y; Ali M; Zeller MW; Bure L; Wang CH; Choi Y; Masia R; Guimaraes AR; Corey KE; Chen JW Molecular MR Imaging of Myeloperoxidase Distinguishes Steatosis from Steatohepatitis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Radiology 2017, 284 (2), 390–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Kleijn A; Chen JW; Buhrman JS; Wojtkiewicz GR; Iwamoto Y; Lamfers ML; Stemmer-Rachamimov AO; Rabkin SD; Weissleder R; Martuza RL; Fulci G Distinguishing Inflammation from Tumor and Peritumoral Edema by Myeloperoxidase Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Clin. Cancer Res 2011, 17 (13), 4484–4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Schneppensieper T; Seibig S; Zahl A; Tregloan P; van Eldik R Influence of Chelate Effects on the Water-Exchange Mechanism of Polyaminecarboxylate Complexes of Iron(III). Inorg. Chem 2001, 40 (15), 3670–3676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Maigut J; Meier R; Zahl A; van Eldik R Effect of chelate dynamics on water exchange reactions of paramagnetic aminopolycarboxylate complexes. Inorg. Chem 2008, 47 (13), 5702–5719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Maigut J; Meier R; Zahl A; Eldik R, van Triggering Water Exchange Mechanisms via Chelate Architecture. Shielding of Transition Metal Centers by Aminopolycarboxylate Spectator Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 14556–14569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Maigut J; Meier R; Zahl A; Eldik R, van Elucidation of the Solution Structure and Water-Exchange Mechanism of Paramagnetic [FeII(edta)(H2O)]2-. Inorg. Chem 2007, 46 (13), 5361–5371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Gale EM; Wey HY; Ramsay I; Yen YF; Sosnovik D; Caravan P A Manganese Based Alternative to Gadolinium: Contrast Enhanced MR Angiography, Pharmacokinetics, and Metabolism. Radiology 2018, 286 (3), 865–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Gale EM; Atanasova I; Blasi F; Ay I; Caravan P A Manganese Alternative to Gadolinium for MRI Contrast. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137 (49), 15548–15557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Wang J; Wang H; Ramsay IA; Erstad DJ; Fuchs BC; Tanabe KK; Caravan P; Gale EM Manganese-Based Contrast Agents for Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Liver Tumors: Structure-Activity Relationships and Lead Candidate Evaluation. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61 (19), 8811–8824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Caravan P; Farrar CT; Frullano L; Uppal R Influence of molecular parameters and increasing magnetic field strength on relaxivity of gadolinium- and manganese-based T1-contrast agents. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2009, 4, 89–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Brausam A; Maigut J; Meier R; Szilagyi PA; Buschmann H-J; Massa W; Homannay Z; van Eldik R Detailed Spectroscopic, Thermodynamic, and Kinetic Studies on the Protolytic Equilibria of FeIIIcydta and the Activation of Hydrogen Peroxide. Inorg. Chem 2009, 48 (16), 7864–7884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Hoselton MA; Wilson LJ; Drago RS Substituent effects on the spin equilibrium observed with hexadentate ligands on iron(II). J. Am. Chem. Soc 1975, 97 (7), 1722–1729. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Crawford TH; Swanson J TEMPERATURE DEPENDENT MAGNETIC MEASUREMENTS AND STRUCTURAL EQUILIBRIA IN SOLUTION. J. Chem. Educ 1971, 48 (6), 382. [Google Scholar]

- (60).Swift TJ; Connick RE NMR-Relaxation Mechanisms of O17 in Aqueous Solutions of Paramagnetic Cations and the Lifetime of Water Molecules in the First Coordination Sphere. J. Chem. Phys 1962, 37 (2), 307–320. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Wood PM THE POTENTIAL DIAGRAM FOR OXYGEN AT PH-7. Biochem. J 1988, 253 (1), 287–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Caravan P; Ellison JJ; McMurry TJ; Lauffer RB Gadolinium(III) chelates as MRI contrast agents: structure, dynamics and applications. Chem. Rev 1999, 99 (9), 2293–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Djanashvili K; Peters JA, How to determine the number of inner-sphere water molecules in Lanthanide(III) complexes by 17O NMR spectroscopy. A technical note. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2007, 2, 67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Ducommun Y; Newman KE; Merbach AE High-pressure 170 NMR Evidence for a Gradual Mechanistic Changeover from I, to Id for Water Exchange on Divalent Octahedral Metal Ions Going from Manganese(II) to Nickel(II). Inorg. Chem 1980, 19, 3696–3703. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Poole LB The Basics of Thiols and Cysteines in Redox Biology and Chemistry. Free Radical Biol. Med 2015, 148–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Turell L; Radi R; Alvarez B The thiol pool in human plasma: The central contribution of albumin to redox processes. Free Radical Biol. Med 2013, 65, 244–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Ma R; Motekaitis RJ; Martell AE Synthesis of Nhydroxybenzylethylenediamine- N,N’,N’-triacetic acid and the stabilities of its complexes with divalent and trivalent metal ions. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1995, 233, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- (68).Rorabacher DB Electron Transfer by Copper Centers. Chem. Rev 2004, 104, 651–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Aisen P; Leibman A; Zweier JL Stoichiometric and Site Characteristics of the Binding of Iron to Human Transferrin. J. Biol. Chem 1978, 253 (6), 1930–1937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Gkouvatsos K; Papanikolaou G; et al. Regulation of iron transport and the roleof transferrin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj 2012, 1820, 188–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Harris WR Estimation of the Ferrous-Transferrin Binding Constants Based on Thermodynamic Studies of Nickel(II)-Transferrin. J. Inorg. Biochem 1986, 27, 41–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Daugherty A; Dunn JL; Rateri DL; Heinecke JW Myeloperoxidase, a Catalyst for Lipoprotein Oxidation, Is Expressed in Human Atherosclerotic Lesions. J. Clin. Invest 1994, 94 (1), 437–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Ding S-P; Jin C A mouse model of severe acute pancreatitis induced with caerulein and lipopolysaccharide. World J. Gastroenterol 2003, 9 (3), 584–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Lerch MM; Gorelick FS Models of Acute and Chronic Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2013, 144 (6), 1180–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Davies MJ Myeloperoxidase-derived oxidation: mechanisms of biological damage and its prevention. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr 2010, 48 (1), 8–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.