Key Points

Question

What is the symptom burden of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma in the first year following resection?

Findings

In this population-based cohort study of 615 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, we demonstrate that clinically significant symptoms are prevalent following resection, but these symptoms improve in the first 3 months following surgery and certain patient factors are associated with an increased risk of symptom reporting.

Meaning

Targeted interventions should be designed to preemptively address symptom burden for at-risk patient groups.

Abstract

Importance

Postoperative morbidity associated with pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PA) remains as high as 70%. However, to our knowledge, few studies have examined quality of life in this patient population.

Objective

To identify symptom burden and trajectories and factors associated with high symptom burden following PD for PA.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based cohort study of patients undergoing PD for PA diagnosed between 2009 and 2015 linked population-level administrative health care data to routinely prospectively collected Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) scores from 2009 to 2015, with a data analysis undertaken in 2018.

Exposures

Baseline characteristics, including age, sex, income quintile, rurality, immigration status, and comorbidity burden, as well as treatment characteristics, including year of surgery and receipt of chemotherapy.

Main Outcome and Measures

The outcome of interest was moderate to severe symptoms (defined as ESAS ≥4) for anxiety, depression, drowsiness, lack of appetite, nausea, pain, shortness of breath, tiredness, and impaired well-being. The monthly prevalence of moderate to severe symptoms was presented graphically for each symptom. Multivariable regression models identified factors associated with the reporting of moderate to severe symptoms.

Results

We analyzed 6058 individual symptom assessments among 615 patients with PA who underwent resection (285 women [46.3%]) with ESAS data. Tiredness (443 [72%]), impaired well-being (418 [68%]), and lack of appetite (400 [65%]) were most commonly reported as moderate to severe. The proportion of patients with moderate to severe symptoms was highest immediately after surgery (range, 14%-66% per symptom) and decreased over time, stabilizing around 3 months (range, 8%-42% per symptom). Female sex, higher comorbidity, and lower income were associated with a higher risk of reporting moderate to severe symptoms. Receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy was not associated with the risk of moderate to severe symptoms.

Conclusions and Relevance

There is a high prevalence of symptoms following PD for PA, with improvement over the first 3 months following surgery. In what to our knowledge is the largest cohort reporting on symptom burden for this population, we have identified factors associated with symptom severity. These findings will aid in managing patients’ perioperative expectations and designing strategies to improve targeted symptom management.

This cohort study describes symptom burdens in Canadian patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma who underwent resection.

Introduction

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a high-fatality cancer responsible for 44 000 deaths annually in the United States.1 Despite improvements in therapy, 5-year overall survival rates remain as low as 6.9% across all stages.2 Only 20% of patients with a new diagnosis are eligible for potentially curative treatment with complete resection, most often undertaken with pancreaticoduodenectomy. This surgery is associated with high postoperative morbidity in 30% to 70% of patients, even in high-volume centers.3,4,5,6,7 Major morbidity following curative-intent resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma not only substantially affects quality of life,8,9,10 but it can also delay the delivery of adjuvant chemotherapy necessary to optimize outcomes.4,11,12,13,14,15,16

Pancreatic cancer, as well as the treatments aimed at its cure, may affect patients’ quality of life. The current literature on symptom burden during postoperative recovery from pancreaticoduodenectomy is limited by small sample sizes, often fewer than 100 patients, and focuses primarily on symptom reporting only in the first few weeks following diagnosis or surgery.17,18,19 Thus, there is a lack of information regarding postoperative recovery patterns and symptoms for patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Examining patient-reported symptoms following surgery will enable the creation of better support systems, better counseling and management of patients’ expectations, and improved recovery for a better patient experience as well as optimize access to adjuvant therapy.

The integration of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) into routine clinical care can support clinical care for patients with cancer.17,18,20 Routine prospective collection of patient-reported Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) scores during all outpatient cancer clinic visits was initiated in 2007 in Ontario, Canada.21,22,23 This provides unique opportunities to appreciate patients’ symptom burden with therapies at the population level. Therefore, we leveraged this province-wide prospective patient-reported data to examine symptom trajectories over time and determine factors associated with reporting moderate to severe symptom burden in the first year following pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Methods

Study Design

This was a cohort study using prospectively collected PROMs data linked to administrative health care data sets housed at ICES. It was conducted on all patients with a valid Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) number. Under the Canada Health Act, Ontario’s 13.5 million residents benefit from universally accessible and publicly funded health care though OHIP. As this was a province-wide program occurring in all RCCs and affiliates, patients did not provide consent but were encouraged to complete the ESAS assessment but cancer center staff.

The study was approved by the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre research ethics board and adheres to the data confidentiality and privacy policy of ICES. It was conducted and reported following the Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely Collected Data statement.24

Study Cohort

Patients with a diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in the Ontario Cancer Registry were identified using the International Classification of Disease for Oncology (ICD-O) codes (ICD-O-3 codes: C25.0-C25.9). Adults (≥18 years) who received a diagnosis between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2015, who were undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy within 6 months of diagnosis and reporting at least 1 ESAS score in the 12 months from the date of surgery were included. Pancreaticoduodenectomy was identified using physician claims in OHIP (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Patients were excluded if they were not seen at a regional cancer center (RCC) or an affiliate, their date of death occurred before the date of diagnosis, they had an invalid or missing unique identification number, they had additional cancer diagnoses at any time before or after the diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma to avoid misattribution of symptom burden to pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and they received chemotherapy or radiation within 12 months before pancreaticoduodenectomy to avoid misattributing symptom burden to neoadjuvant therapy instead of resection.

Data Sources

The Ontario Cancer Registry includes approximately 95% of patients who received a diagnosis of cancer (excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer) in Ontario since 1964.25,26 The Registered Persons Database contains vital status and demographic data on all individuals covered under OHIP.27 Immigration status was obtained from the Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada database.28 Information regarding health services provided is included in the Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI) Discharge Abstract Database for acute inpatient hospitalizations; the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System for emergency department and oncology clinic visits; the Cancer Activity Level Reporting database, which includes information on patient activity within the cancer care system, specifically radiotherapy, systemic therapy, and outpatient oncology visits; and the OHIP claims database for billing from health care clinicians, including physicians, groups, laboratories, and out-of-province clinicians.29 The ESAS scores were abstracted from the Cancer Care Ontario (CCO) Symptom Management Reporting Database, which contains the symptom screening scores, date, and location of all ESAS scores reported by patients during outpatient cancer visits in the province.30,31

Outcomes

The main outcome of interest was moderate to severe symptoms, defined as an ESAS score of 4 or greater of 10.32 The ESAS is a validated and reliable PROM tool assessing the severity of 9 common cancer-associated symptoms: anxiety, depression, drowsiness, lack of appetite, nausea, pain, shortness of breath, tiredness, and impaired well-being.33,34,35 Patients rate each symptom on a 11-point numeric scale, from 0 (absence of symptom) to 10 (worst possible symptom).33 The ESAS scores were classified by the severity to facilitate description: no symptoms (0), mild symptoms (1-3), moderate symptoms (4-6), and severe symptoms (7-10).32,36 Scores of 4 or higher have been previously shown to represent moderate to severe symptoms.32 We measured ESAS scores of 4 or higher for each month within the first 12 months following the date of surgery. If a patient reported more than 1 ESAS score in a month, the highest score was retained.

Covariates

All baseline characteristics were measured at the time of surgery. Age and sex were abstracted from the Registered Persons Database. Rural residence was defined using the Rurality Index of Ontario based on the postal code of the patients’ primary residence. Rural residence was categorized as a Rural Index of Ontario score of 40 or greater or missing.37 Neighborhood income was assessed based on the median income of a patient’s postal code of residence using national census data.38,39 Immigration status was determined from the Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada database and we defined patients as immigrants or nonimmigrants by the presence or absence of a record. Comorbidity burden was calculated using the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups system score based on health services use in the 24 months before the date of surgery, excluding diagnoses associated with malignancy. The aggregated diagnosis groups were summed in a total score that was dichotomized with a cutoff of 10 or more for high comorbidity burden, consistent with previous studies.40,41,42 The year of surgery was included to assess for secular trends in supportive care practices and was categorized as 2009 to 2012 or 2013 to 2016. To define the month from the diagnosis, we identified ESAS records in each month from diagnosis.

Treatment modality was defined as adjuvant chemotherapy, adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, or no adjuvant treatment. Adjuvant chemotherapy was defined as the presence of at least 1 OHIP physician claims billing code for chemotherapy within 120 days of surgery and at least 2 chemotherapy treatments within 150 days of surgery. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy was defined as receipt of chemotherapy plus receipt of radiation within 120 days or surgery, as captured in the Cancer Activity Level Reporting database (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Patients who have received chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy outside of the 120 days following surgery were considered palliative and categorized as no adjuvant treatment. We considered symptoms associated with the immediate effects of any type of chemotherapy using a time-varying covariate; ESAS scores were attributed to chemotherapy if they occurred within 2 weeks of the chemotherapy administration date. Chemoradiotherapy was not included in multivariable analyses because of the small sample size.

Statistical Analysis

For descriptive analyses, categorical variables were reported as absolute number and proportion (%) and continuous variables as median with interquartile ranges. The characteristics of patients who did and did not report ESAS scores following surgery were compared using χ2 tests for independence. Monthly trajectories of moderate to severe symptoms in the 12 months following surgery were presented graphically. The number of ESAS assessments reported each month was used as the denominator. We separately described symptom trajectories for patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy and surgery alone to appreciate any differences in symptom trajectory according to cancer-directed treatment.

Possible factors associated with moderate to severe symptoms were examined, including age (categorical), sex, income quintile, rurality, immigration status, comorbidity burden, year of surgery, receipt of chemotherapy around ESAS assessment, and months from surgery. These factors were identified a priori as potentially associated with symptoms based on clinical relevance (markers of complexity of care for pancreatic adenocarcinoma) and existing literature (known association with care for pancreatic adenocarcinoma and postoperative course).31,43,44,45,46 Univariable and multivariable modified Poisson regression models with robust error variance were created to assess the association between possible factors and moderate to severe symptoms for each of the 9 symptoms. Generalized estimating equations with exchangeable correlation structures were used to adjust for the clustering of repeated measurements at the patient level and an offset was used to adjust for the varying amount of follow-up time between patients.47 All predictors identified a priori were included in the models. The results were reported as relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals and statistical significance was defined as a P < .05. Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Study Cohort

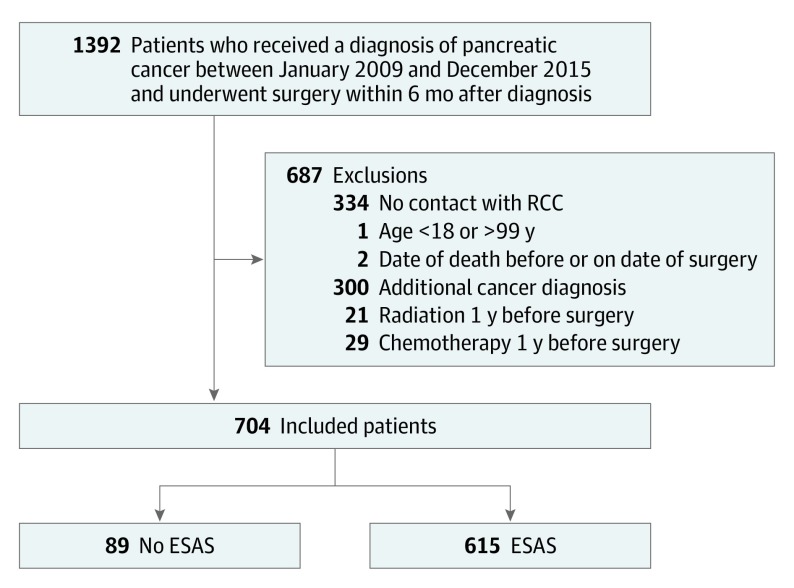

A total of 704 patients received a diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma between January 2009 and December 2015 and underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy within 6 months of diagnosis; of these patients, 615 (87%) recorded at least 1 ESAS assessment (Figure 1). Patient characteristics are described in Table 1. Most patients received adjuvant chemotherapy (412 [67%]). Characteristics of patients with and without ESAS records at the time of surgery are outlined in eTable 2 in the Supplement. Those who completed ESAS were more likely to be younger and nonimmigrants.

Figure 1. Cohort Exclusions.

ESAS indicates Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; RCC, regional cancer centre.

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients With Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Undergoing Pancreaticoduodenectomy Who Reported at Least 1 ESAS Score Following Surgery.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age category, y | |

| <55 | 106 (17.2) |

| 55-64 | 190 (30.9) |

| 65-74 | 217 (35.3) |

| ≥75 | 102 (16.6) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 330 (53.7) |

| Female | 285 (46.3) |

| Income quintile | |

| First (lowest) | 94 (15.3) |

| Second | 128 (20.8) |

| Third | 137 (22.3) |

| Fourth | 124 (20.2) |

| Fifth (highest) | 129 (21.0) |

| Residence | |

| Urban | 540 (87.8) |

| Rural | 75 (12.2) |

| Immigration status | |

| Nonimmigrants | 581 (94.5) |

| Immigrants | 34 (5.5) |

| Comorbidity burden | |

| Low (ADG <10) | 339 (55.1) |

| High (ADG ≥10) | 276 (44.9) |

| Year of surgery | |

| 2009-2012 | 290 (47.2) |

| 2013-2016 | 325 (52.8) |

| Treatment course | |

| No adjuvant therapy | 122 (19.8) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 410 (66.7) |

| Adjuvant chemoradiation | 83 (13.5) |

Abbreviations: ADG, aggregate diagnosis group; ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System.

Symptom Severity Following Surgery

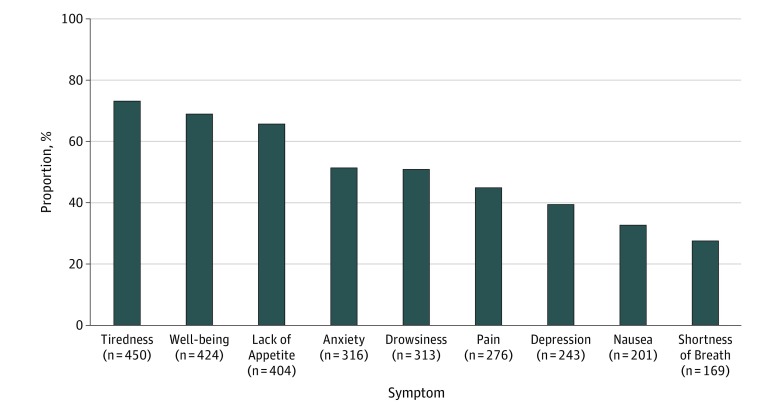

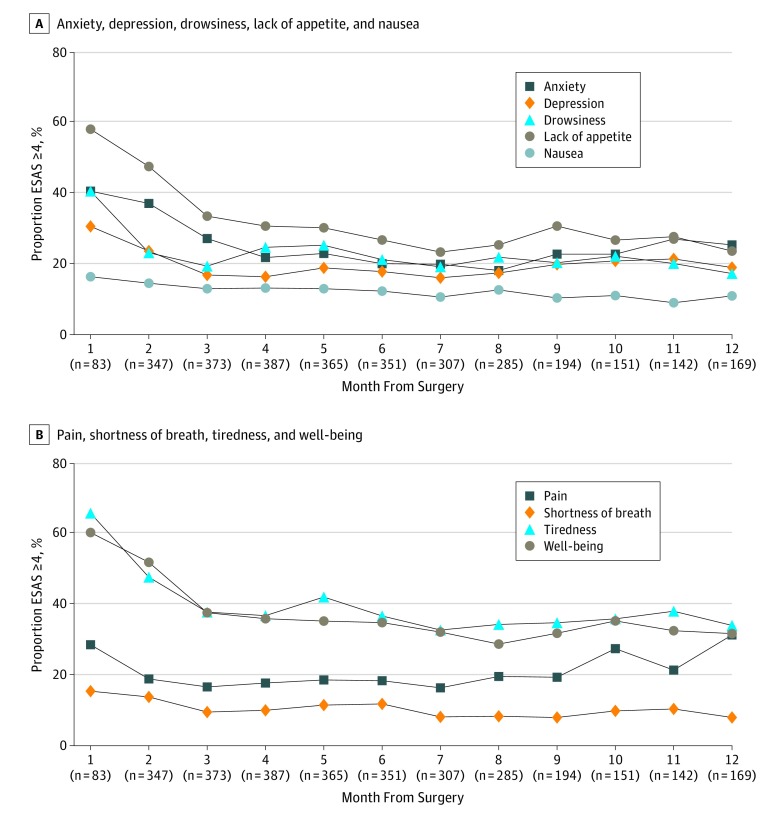

A total of 6058 symptom assessments were included in the analysis. Each patient contributed a median of 8 ESAS assessments (interquartile range, 4-14). The symptoms most frequently reported as moderate to severe were tiredness (449 [73%] reported at least 1 score of ≥4 in the year following date of surgery), impaired well-being (424 [69%]), and lack of appetite (406 [66%]) (Figure 2). When looking specifically at patients undergoing surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and patients undergoing surgery alone, these symptoms were similarly seen as most frequently reported (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Trajectories for moderate to severe symptoms in each month following pancreaticoduodenectomy are depicted in Figure 3. For most symptoms, trajectories began high immediately after surgery (range, 14%-66% per symptom), decreasing rapidly in the first 2 months and eventually plateauing between 3 to 10 months (range, 8%-42% per symptom). Anxiety, depression, and pain increased again at around 10 to 12 months. When looking only at patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy, similar patterns were observed. In patients undergoing surgery alone, a similar pattern was also seen, although this subgroup experienced greater variability in the proportion of patients reporting symptoms given its smaller size (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Proportion of Patients Reporting at Least 1 Moderate to Severe Edmonton Symptom Assessment Score (ESAS) Following Surgery.

Numbers under the x-axis indicate the total number of patients reporting at least 1 moderate to severe ESAS (>4) for each symptom while numbers within bars represent the proportion (%) of patients within the cohort reporting at least 1 moderate to severe ESAS for each symptom (N = 615).

Figure 3. Proportion of All Patients Reporting Moderate to Severe Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scores (ESAS) for All Symptoms by Month of Assessment Following Surgery.

Trendlines facilitate the visualization of trends over time but do not represent continuous data. Numbers under the x-axis indicate the denominator for each month. A moderate to severe ESAS is a score of more than 4.

Factors Associated With Reporting Moderate to Severe Symptoms

There were significant variations in the risk of reporting moderate to severe symptom scores based on patient characteristics (Table 2). Patient characteristics associated with symptom burden included age, sex, comorbidity burden, rural living, and income quintile. Women were at a 1.2 to 1.5 times increased risk of reporting moderate to severe scores for all symptoms except drowsiness (RR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.97-1.46) and shortness of breath (RR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.61-1.16) compared with men. Patients with a higher comorbidity burden and in lower income quintiles were at 1.2 and 1.5 times greater risk of reporting moderate to severe tiredness (high comorbidity: RR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.02-1.35; lowest income quintile: RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.91-1.45) and pain (high comorbidity: RR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.96-1.51; lowest income quintile: RR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.08-1.71), respectively. Conversely, older patients and those living in more rural communities were 0.6 times less likely to report moderate to severe symptoms for nausea (>75 years: RR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.34-0.92; rural: RR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.40-1.13) and drowsiness (>75 years: RR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.62-1.23; rural: RR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.47-0.97), respectively.

Table 2. Multivariable Modified Poisson Regression Analysis of the Association Between Patient and Treatment Characteristics and Moderate to Severe ESAS Score in the 12 Months Following Surgery for All Symptoms.

| Characteristic | RR (95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Depression | Drowsiness | Lack of Appetite | Nausea | Pain | Shortness of Breath | Tiredness | Well-being | |

| Age category, y | |||||||||

| <55 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 55-64 | 0.81 (0.62-1.06) | 0.90 (0.64-1.26) | 0.81 (0.60-1.11) | 1.07 (0.83-1.31) | 0.68 (0.46-0.99)a | 0.97 (0.71-1.32) | 1.03 (0.63-1.69) | 0.86 (0.69-1.06) | 0.95 (0.76-1.20) |

| 65-74 | 0.79 (0.61-1.02) | 0.75 (0.54-1.05) | 0.82 (0.60-1.11) | 1.09 (0.86-1.23) | 0.63 (0.43-0.93)a | 0.76 (0.55-1.05) | 0.94 (0.57-1.54) | 0.91 (0.74-1.11) | 1.01 (0.81-1.26) |

| ≥75 | 0.74 (0.54-1.03) | 0.74 (0.49-1.12) | 0.87 (0.62-1.23) | 1.21 (0.92-1.59) | 0.56 (0.34-0.92)a | 0.79 (0.54-1.15) | 1.45 (0.84-2.52) | 0.99 (0.78-1.25) | 0.99 (0.76-1.28) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 1.50 (1.24-1.82)a | 1.32 (1.03-1.68)a | 1.19 (0.97-1.46) | 1.31 (1.11-1.53)a | 1.53 (1.14-2.04)a | 1.25 (1.00-1.56)a | 0.84 (0.61-1.16)a | 1.17 (1.02-1.35)a | 1.23 (1.06-1.43)a |

| Income quintile | |||||||||

| First (lowest) | 1.08 (0.77-1.53) | 1.18 (0.77-1.79) | 1.22 (0.84-1.77) | 0.96 (0.75-1.25) | 1.05 (0.65-1.71) | 1.55 (1.08-2.24)a | 1.09 (0.65-1.81) | 1.15 (0.91-1.45) | 0.94 (0.73-1.22) |

| Second | 1.23 (0.90-1.67) | 1.22 (0.82-1.81) | 1.33 (0.95-1.85) | 0.97 (0.76-1.18) | 1.41 (0.88-2.26) | 1.46 (1.02-2.09)a | 1.15 (0.71-1.88) | 1.10 (0.88-1.38) | 1.08 (0.86-1.36) |

| Third | 1.10 (0.82-1.49) | 1.14 (0.79-1.65) | 1.30 (0.93-1.83) | 0.84 (0.67-1.06) | 1.29 (0.83-2.01) | 1.15 (0.81-1.61) | 0.95 (0.58-1.55) | 1.10 (0.88-1.37) | 0.97 (0.77-1.21) |

| Fourth | 1.14 (0.84-1.53) | 1.10 (0.75-1.62) | 1.28 (0.92-1.78) | 0.87 (0.69-1.11) | 1.42 (0.90-2.23) | 1.28 (0.90-1.82) | 1.17 (0.72-1.89) | 1.03 (0.82-1.30) | 0.98 (0.78-1.23) |

| Fifth (highest) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Residence | |||||||||

| Urban | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Rural | 0.76 (0.55-1.04) | 0.85 (0.57-1.28) | 0.68 (0.47-0.97)a | 1.04 (0.81-1.32) | 0.67 (0.40-1.13) | 0.73 (0.51-1.06) | 0.69 (0.39-1.24) | 0.83 (0.66-1.05) | 0.79 (0.61-1.03) |

| Immigration status | |||||||||

| Nonimmigrants | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Immigrants | 1.00 (0.67-1.50) | 1.00 (0.64-1.58) | 0.49 (0.26-0.93)a | 1.06 (0.75-1.49) | 1.20 (0.71-2.02) | 1.21 (0.82-1.79) | 0.72 (0.35-1.47) | 0.89 (0.66-1.05) | 1.05 (0.77-1.45) |

| Comorbidity burden | |||||||||

| Low (ADG <10) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| High (ADG ≥10) | 1.19 (0.98-1.44) | 1.22 (0.96-1.57) | 1.09 (0.88-1.34) | 1.11 (0.95-1.30) | 1.10 (0.82-1.48) | 1.20 (0.96-1.51) | 1.35 (0.99-1.85) | 1.17 (1.02-1.35) | 1.13 (0.97-1.31) |

| Year of surgery | |||||||||

| 2009-2012 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 2013-2016 | 0.95 (0.78-1.15) | 1.05 (0.82-1.35) | 1.09 (0.88-1.34) | 0.81 (0.69-0.95)a | 0.84 (0.63-1.12) | 0.94 (0.75-1.18) | 0.94 (0.68-1.29) | 0.97 (0.84-1.12) | 0.99 (0.85-1.16) |

| Month from surgery | |||||||||

| 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 2 | 0.92 (0.72-1.17) | 0.86 (0.63-1.16) | 0.54 (0.41-0.72)a | 0.80 (0.66-0.98)a | 0.85 (0.55-1.33) | 0.72 (0.50-1.04) | 0.93 (0.54-1.58) | 0.71 (0.60-0.84)a | 0.83 (0.69-1.00)a |

| 3 | 0.71 (0.55-0.92)a | 0.69 (0.49-0.96)a | 0.48 (0.36-0.64)a | 0.58 (0.47-0.72)a | 0.73 (0.46-1.15) | 0.66 (0.44-0.98)a | 0.65 (0.36-1.16) | 0.58 (0.48-0.69)a | 0.62 (0.51-0.76)a |

| 4 | 0.58 (0.44-0.76)a | 0.67 (0.47-0.96)a | 0.57 (0.42-0.76a) | 0.52 (0.41-0.66)a | 0.72 (0.45-1.14) | 0.76 (0.51-1.13) | 0.72 (0.40-1.28) | 0.54 (0.44-0.65)a | 0.58 (0.47-0.72)a |

| 5 | 0.57 (0.43-0.75)a | 0.71 (0.50-1.00)a | 0.56 (0.42-0.75)a | 0.51 (0.40-0.64)a | 0.67 (0.42-1.06) | 0.76 (0.51-1.13) | 0.81 (0.45-1.47) | 0.60 (0.50-0.72)a | 0.56 (0.45-0.69)a |

| 6 | 0.52 (0.39-0.70)a | 0.70 (0.49-0.99)a | 0.49 (0.37-0.66)a | 0.46 (0.36-0.58)a | 0.64 (0.40-1.03) | 0.74 (0.50-1.09) | 0.81 (0.45-1.46) | 0.54 (0.45-0.65)a | 0.55 (0.45-0.69)a |

| 7 | 0.52 (0.39-0.69)a | 0.65 (0.46-0.91)a | 0.46 (0.34-0.63)a | 0.42 (0.33-0.54)a | 0.59 (0.35-0.97)a | 0.69 (0.47-1.03) | 0.65 (0.37-1.14) | 0.48 (0.40-0.59)a | 0.53 (0.43-0.66)a |

| 8 | 0.49 (0.37-0.65)a | 0.68 (0.48-0.96)a | 0.55 (0.42-0.74)a | 0.43 (0.34-0.55)a | 0.70 (0.43-1.14) | 0.78 (0.54-1.14) | 0.62 (0.34-1.15) | 0.51 (0.42-0.62)a | 0.48 (0.39-0.60)a |

| 9 | 0.57 (0.43-0.75)a | 0.75 (0.54-1.06) | 0.50 (0.37-0.67)a | 0.50 (0.39-0.64)a | 0.57 (0.34-0.98)a | 0.69 (0.46-1.06) | 0.60 (0.32-1.12) | 0.51 (0.42-0.63)a | 0.51 (0.41-0.63)a |

| 10 | 0.59 (0.44-0.80)a | 0.78 (0.55-1.11) | 0.51 (0.38-0.70)a | 0.46 (0.35-0.61)a | 0.61 (0.36-1.06) | 0.97 (0.65-1.43) | 0.76 (0.42-1.39) | 0.53 (0.43-0.65)a | 0.61 (0.49-0.75)a |

| 11 | 0.68 (0.51-0.92)a | 0.80 (0.56-1.14) | 0.49 (0.35-0.67)a | 0.45 (0.34-0.60)a | 0.49 (0.28-0.87)a | 0.73 (0.47-1.12) | 0.80 (0.43-1.47) | 0.56 (0.46-0.70)a | 0.54 (0.43-0.68)a |

| 12 | 0.65 (0.49-0.87)a | 0.78 (0.55-1.10) | 0.50 (0.36-0.69)a | 0.45 (0.35-0.58)a | 0.62 (0.37-1.06) | 1.22 (0.84-1.78) | 0.73 (0.40-1.35) | 0.55 (0.45-0.67)a | 0.57 (0.45-0.71)a |

| Chemotherapy received 2 wk before ESAS assessment | |||||||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 0.93 (0.81-1.06) | 0.98 (0.84-1.14) | 1.15 (0.99-1.33) | 1.00 (0.88-1.14) | 1.13 (0.92-1.40) | 0.86 (0.74-1.01) | 1.02 (0.81-1.29) | 1.08 (0.98-1.19) | 1.05 (0.95-1.15) |

Abbreviations: ADG, aggregated diagnosis group; ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; RR, relative risk.

Statistically significant (P < .05).

Regarding treatment characteristics, patients undergoing surgery between 2013 and 2016 had a lower risk of reporting lack of appetite (RR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.69-0.95) compared with those undergoing surgery earlier between 2009 and 2012. Patients reporting symptoms in months 2 and onwards following surgery were at a decreased risk of reporting moderate to severe symptom scores compared with month 1 for all symptoms except nausea (month 2: RR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.55-1.33), pain (month 2: RR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.50-1.04), and shortness of breath (month 2: RR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.54-1.58). This effect did not persist with all symptoms, specifically the proportion of patients reporting moderate to severe depression returned to baseline at month 9 (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.54-1.06). However, the overall pattern of initial symptom improvement mirrors the pattern observed in Figure 3 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement. Finally, receiving chemotherapy within 2 weeks of symptom screening was not associated with the reporting of moderate to severe symptoms.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the largest to describe symptom burden in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma who underwent resection. It echoes the results of prior work describing the experience of patients with pancreatic cancer, with tiredness and lack of appetite symptoms most commonly reported following surgery.10,48,49 We further described the symptom trajectories, with a rapid decrease and subsequent plateau following surgery. Younger age, female sex, higher comorbidity burden, urban living, and lower income were associated with reporting moderate to severe symptoms.

Peak symptoms during the initial 2 months following surgery were likely secondary to patients’ postoperative recovery. This initial finding may appear intuitive owing to the typical challenges faced by patients when attempting to cope with a recent surgery.50 However, the rapid improvement in symptoms within 3 months following surgery is encouraging for patients and health care clinicians and contrasts with previous studies on quality-of-life indicators in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma who underwent resection, for whom symptoms consistently are reported as being progressively worse following surgery.9,17,48 This rapid improvement in symptoms observed in this study could be because of better symptom management in the more contemporary study period as clinicians turn their focus to patient-centered medicine or the longer longitudinal observation period and larger sample size that may allow for more time and power to observe an improvement. Alternatively, the observed rapid symptom improvement may be a product of patient selection, whereby regionalization results in better care and thus these patients may have more appropriately managed symptoms.51 However, improvement in symptom control was also reflected in the multivariable analysis, which demonstrated that from month 2 onwards there was a reduced risk of reporting elevated symptoms.

Encouragingly, our results show that receiving adjuvant chemotherapy did not worsen symptom profiles following surgery, which is consistent with prior data.16,52 This finding is important to highlight to patients on referral to adjuvant therapy. The idea that adjuvant chemotherapy does not necessarily worsen symptoms, as might be expected, can further support the initiation of this therapy known to improve survival for pancreatic adenocarcinoma.4,53 These findings project a more optimistic outlook on symptom control in pancreatic cancer treatment than is typically discussed.

Previous studies have shown that administering PROMs improves clinical outcomes, including fewer presentations to the emergency department, fewer admissions to hospitals, and a longer duration of chemotherapy.21,54 Indeed, the findings in this study have several implications. The knowledge that symptom severity is expected to improve in the first few months following surgery is promising and will aid health care clinicians in identifying patients who veer off the anticipated trajectory and may require extra supportive care and resources. Knowledge of at-risk groups, including women, patients with comorbidities, and patients of lower socioeconomic status, will preemptively identify patients who need these supports from the outset, perhaps even before they undergo surgery. This information will be particularly important in regions where the use of PROMs is less established. Furthermore, this information can aid in the development of targeted interventions for patients and their families. For example, patients who have self-identified to have an elevated symptom burden or patient groups known to be high risk may be flagged and automatically connected to social support networks or psychotherapists, considered for special funding requests, booked for earlier follow-up appointments, or scheduled for more frequent phone call follow-ups. Coordinating these services has previously been demonstrated to improve patient satisfaction and reduce health care costs.55,56,57 These findings are thus important in informing health care policy.

This study represents the largest assessment of PROMs in pancreatic adenocarcinoma, with 6058 unique symptom assessments in 615 patients. It relies on prospectively collected symptom scores, with a high screening rate of 87% of patients treated at RCCs.17,48,58,59,60,61 This large proportion of patients contributing symptom assessments represents a remarkable finding, as this is significantly higher than that reported in other cancer types using the same ESAS database as well as in previous other studies on pancreatic adenocarcinoma.31 Although there is a focus on symptom control in patients with palliative cancer, symptom surveillance and management can often be overlooked in a curative-intent population. This latter subgroup of patients thus warrants particular attention to improve symptom tracking and management. We focused specifically on curative-intent patients by identifying those undergoing definitive resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma, thereby filling a gap in the pancreatic cancer literature. Beyond demonstrating that patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma treated with a curative intent carry a substantial symptom burden, we provide the first longitudinal assessment of symptom severity over time following surgery and identified risk factors for higher symptom burden. This information on patient-reported symptoms is better powered than previous reports using quality-of-life instruments, as it represents an assessment of patients’ experiences that is actionable in the clinical setting.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the variation in rates of patient-reported symptom screenings. Although collected across the province, ESAS score collection in Ontario is opportunistic and was not uniformly collected at all clinical institutions over the study period, reflecting the implementation of the provincial symptom assessment program whereby routine screening was initially focused on specialized cancer clinics. Although we did observe that 87% of our cohort contributed symptom screening scores, this may affect the generalizability of the results. When comparing those within RCCs who did and did not complete ESAS, patients who contributed ESAS scores were younger and more likely to be nonimmigrants. Thus, older patients and immigrants may be under-represented, patient demographics often representing a more vulnerable group who may report more elevated symptoms.62 Furthermore, administration of ESAS in the outpatient setting favors patients who make frequent clinic visits and may exclude patients with greater illness severity admitted to hospital, a palliative care unit, or the emergency department. This would potentially underestimate symptom severity and give a higher quality-of-life estimate in our study population. For this reason, it would be interesting to explore the association between symptoms and complications prompting admissions to hospital, and this should be the focus of future work.

Conclusions

This study provides a detailed assessment of symptom burden in pancreatic adenocarcinoma treated with curative-intent surgery during a critical period of care for surgically and medically aggressive therapy. We have identified the prevalence, trajectories, and risk factors for patient-reported symptom severity in what is to our knowledge the largest cohort with the highest response rates to date. Long-term applications of these data include the sharing of expected trajectories with patient and families during preoperative and postoperative counseling and the development of patient-centered interventions to improve quality of life in a highly morbid disease.

eTable 1. OHIP and CIHI codes

eTable 2. Characteristics of pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy, stratified by recording of ESAS in the twelve months following surgery

eFigure 1. Proportion of patients undergoing surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy (N=410) and undergoing surgery alone (N=122) reporting at least one moderate to severe ESAS score (>4) following surgery

eFigure 2. Proportion of patients undergoing surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy (A) and undergoing surgery alone (B) reporting moderate to severe ESAS scores (≥4) for all symptoms

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):-. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun H, Ma H, Hong G, Sun H, Wang J. Survival improvement in patients with pancreatic cancer by decade: a period analysis of the SEER database, 1981-2010. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6747. doi: 10.1038/srep06747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenblatt DY, Kelly KJ, Rajamanickam V, et al. . Preoperative factors predict perioperative morbidity and mortality after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(8):2126-2135. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1594-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oettle H, Neuhaus P, Hochhaus A, et al. . Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1473-1481. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.279201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(22):2140-2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sirri E, Castro FA, Kieschke J, et al. . Recent trends in survival of patients with pancreatic cancer in Germany and the United States. Pancreas. 2016;45(6):908-914. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2011;378(9791):607-620. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62307-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belyaev O, Herzog T, Chromik AM, Meurer K, Uhl W. Early and late postoperative changes in the quality of life after pancreatic surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398(4):547-555. doi: 10.1007/s00423-013-1076-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crippa S, Domínguez I, Rodríguez JR, et al. . Quality of life in pancreatic cancer: analysis by stage and treatment. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(5):783-793. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0391-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark KL, Loscalzo M, Trask PC, Zabora J, Philip EJ. Psychological distress in patients with pancreatic cancer—an understudied group. Psychooncology. 2010;19(12):1313-1320. doi: 10.1002/pon.1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Correa-Gallego C, Gonen M, Fischer M, et al. . Perioperative complications influence recurrence and survival after resection of hepatic colorectal metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(8):2477-2484. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2975-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lohrisch C, Paltiel C, Gelmon K, et al. . Impact on survival of time from definitive surgery to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(30):4888-4894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.6089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biagi JJ, Raphael MJ, Mackillop WJ, Kong W, King WD, Booth CM. Association between time to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305(22):2335-2342. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. ; Groupe Tumeurs Digestives of Unicancer; PRODIGE Intergroup . FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1817-1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, et al. ; European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer . Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10073):1011-1024. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32409-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, et al. . Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297(3):267-277. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eaton AA, Gonen M, Karanicolas P, et al. . Health-related quality of life after pancreatectomy: results from a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(7):2137-2145. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-5077-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun V, Ferrell B, Juarez G, Wagman LD, Yen Y, Chung V. Symptom concerns and quality of life in hepatobiliary cancers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(3):E45-E52. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.E45-E52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reyes-Gibby CC, Chan W, Abbruzzese JL, et al. . Patterns of self-reported symptoms in pancreatic cancer patients receiving chemoradiation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(3):244-252. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reilly CM, Bruner DW, Mitchell SA, et al. . A literature synthesis of symptom prevalence and severity in persons receiving active cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(6):1525-1550. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1688-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. . Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. . Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(2):197-198. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotronoulas G, Kearney N, Maguire R, et al. . What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? a systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(14):1480-1501. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.5948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. ; RECORD Working Committee . The Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely-collected Health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robles SC, Marrett LD, Clarke EA, Risch HA. An application of capture-recapture methods to the estimation of completeness of cancer registration. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(5):495-501. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90052-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clarke EA, Marrett LD, Kreiger N. Cancer registration in Ontario: a computer approach. IARC Sci Publ. 1991;(95):246-257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iron K, Zagorski B, Sykora K, et al. Living and dying in Ontario: an opportunity for improved health information. https://www.ices.on.ca/Publications/Atlases-and-Reports/2008/Living-and-dying-in-Ontario. Accessed February 21, 2019.

- 28.Chiu M, Lebenbaum M, Lam K, et al. . Describing the linkages of the immigration, refugees and citizenship Canada permanent resident data and vital statistics death registry to Ontario’s administrative health database. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s12911-016-0375-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juurlink D, Preyra C, Croxford R, et al. . Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database: A Validation Study. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barbera L, Seow H, Howell D, et al. . Symptom burden and performance status in a population-based cohort of ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2010;116(24):5767-5776. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bubis LD, Davis L, Mahar A, et al. . Symptom burden in the first year after cancer diagnosis: an analysis of patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(11):1103-1111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.0876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selby D, Cascella A, Gardiner K, et al. . A single set of numerical cutpoints to define moderate and severe symptoms for the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(2):241-249. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7(2):6-9. doi: 10.1177/082585979100700202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nekolaichuk C, Watanabe S, Beaumont C. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System: a 15-year retrospective review of validation studies (1991-2006). Palliat Med. 2008;22(2):111-122. doi: 10.1177/0269216307087659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richardson LA, Jones GW. A review of the reliability and validity of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. Curr Oncol. 2009;16(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oldenmenger WH, de Raaf PJ, de Klerk C, van der Rijt CC. Cut points on 0-10 numeric rating scales for symptoms included in the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale in cancer patients: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(6):1083-1093. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kralj B. Measuring Rurality—RIO2008_BASIC: Methodology and Results. Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Ontario Medical Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilkins R. Use of postal codes and addresses in the analysis of health data. Health Rep. 1993;5(2):157-177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alter DA, Naylor CD, Austin P, Tu JV. Effects of socioeconomic status on access to invasive cardiac procedures and on mortality after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(18):1359-1367. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiner JP, Starfield BH, Steinwachs DM, Mumford LM. Development and application of a population-oriented measure of ambulatory care case-mix. Med Care. 1991;29(5):452-472. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199105000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reid RJ, MacWilliam L, Verhulst L, Roos N, Atkinson M. Performance of the ACG case-mix system in two Canadian provinces. Med Care. 2001;39(1):86-99. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200101000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reid RJ, Roos NP, MacWilliam L, Frohlich N, Black C. Assessing population health care need using a claims-based ACG morbidity measure: a validation analysis in the Province of Manitoba. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1345-1364. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, et al. . Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. SAGE Study Group. systematic assessment of geriatric drug use via epidemiology. JAMA. 1998;279(23):1877-1882. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheung WY, Le LW, Gagliese L, Zimmermann C. Age and gender differences in symptom intensity and symptom clusters among patients with metastatic cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(3):417-423. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0865-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarfati D, Koczwara B, Jackson C. The impact of comorbidity on cancer and its treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):337-350. doi: 10.3322/caac.21342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, Zafar SY, Ayanian JZ, Schrag D. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15):1732-1740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lipsitz SR, Kim K, Zhao L. Analysis of repeated categorical data using generalized estimating equations. Stat Med. 1994;13(11):1149-1163. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780131106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burrell SA, Yeo TP, Smeltzer SC, et al. . Symptom clusters in patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing surgical resection: part I. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2018;45(4):E36-E52. doi: 10.1188/18.ONF.E36-E52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yount S, Cella D, Webster K, et al. . Assessment of patient-reported clinical outcome in pancreatic and other hepatobiliary cancers: the FACT Hepatobiliary Symptom Index. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(1):32-44. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00422-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2-3):343-351. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simunovic M, Rempel E, Thériault ME, et al. . Influence of hospital characteristics on operative death and survival of patients after major cancer surgery in Ontario. Can J Surg. 2006;49(4):251-258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carter R, Stocken DD, Ghaneh P, et al. ; European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer (ESPAC) . Longitudinal quality of life data can provide insights on the impact of adjuvant treatment for pancreatic cancer—subset analysis of the ESPAC-1 data. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(12):2960-2965. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, et al. . Unicancer GI PRODIGE 24/CCTG PA.6 trial: a multicenter international randomized phase III trial of adjuvant mFOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine (gem) in patients with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.18_suppl.LBA4001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barbera L, Sutradhar R, Howell D, et al. . Does routine symptom screening with ESAS decrease ED visits in breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy? Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(10):3025-3032. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2671-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rocque GB, Pisu M, Jackson BE, et al. ; Patient Care Connect Group . Resource use and Medicare costs during lay navigation for geriatric patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(6):817-825. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fischer K, Hogan V, Jager A, von Allmen D. Efficacy and utility of phone call follow-up after pediatric general surgery versus traditional clinic follow-up. Perm J. 2015;19(1):11-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Healy P, McCrone L, Tully R, et al. . Virtual outpatient clinic as an alternative to an actual clinic visit after surgical discharge: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(1):24-31. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gerritsen A, Jacobs M, Henselmans I, et al. ; Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group . Developing a core set of patient-reported outcomes in pancreatic cancer: a Delphi survey. Eur J Cancer. 2016;57:68-77. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Rijssen LB, Gerritsen A, Henselmans I, et al. . Core Set of Patient-reported Outcomes in Pancreatic Cancer (COPRAC): an international Delphi study among patients and health care providers. Ann Surg. 2019;270(1):158-164. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reni M, Bonetto E, Cordio S, et al. . Quality of life assessment in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: results from a phase III randomized trial. Pancreatology. 2006;6(5):454-463. doi: 10.1159/000094563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Romanus D, Kindler HL, Archer L, et al. ; Cancer and Leukemia Group B . Does health-related quality of life improve for advanced pancreatic cancer patients who respond to gemcitabine? analysis of a randomized phase III trial of the cancer and leukemia group B (CALGB 80303). J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43(2):205-217. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luckett T, Goldstein D, Butow PN, et al. . Psychological morbidity and quality of life of ethnic minority patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(13):1240-1248. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70212-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. OHIP and CIHI codes

eTable 2. Characteristics of pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy, stratified by recording of ESAS in the twelve months following surgery

eFigure 1. Proportion of patients undergoing surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy (N=410) and undergoing surgery alone (N=122) reporting at least one moderate to severe ESAS score (>4) following surgery

eFigure 2. Proportion of patients undergoing surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy (A) and undergoing surgery alone (B) reporting moderate to severe ESAS scores (≥4) for all symptoms