Abstract

Activation of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) is critical for both short- and long-term facilitation in Aplysia sensory neurons. There are two types of the kinase, I and II, differing in their regulatory (R) subunits. We cloned Aplysia RII; RI was cloned previously. Type I PKA is mostly soluble in the cell body whereas type II is enriched at nerve endings where it is bound to two prominent A kinase-anchoring-proteins (AKAPs). Disruption of the binding of RII to AKAPs by Ht31, an inhibitory peptide derived from a human thyroid AKAP, prevents both the short- and the long-term facilitation produced by serotonin (5-HT). During long-term facilitation, RII is transcriptionally upregulated; in contrast, the amount of RI subunits decreases, and previous studies have indicated that the decrease is through ubiquitin-proteosome-mediated proteolysis. Experiments with antisense oligonucleotides injected into the sensory neuron cell body show that the increase in RII protein is essential for the production of long-term facilitation. Using synaptosomes, we found that 5-HT treatment causes RII protein to increase at nerve endings. In addition, using reverse transcription-PCR, we found that RII mRNA is transported from the cell body to nerve terminals. Our results suggest that type I operates in the nucleus to maintain cAMP response element-binding protein-dependent gene expression, and type II PKA acts at sensory neuron synapses phosphorylating proteins to enhance release of neurotransmitter. Thus, the two types of the kinase have distinct but complementary functions in the production of facilitation at synapses of an identified neuron.

Keywords: Aplysia , memory, protein kinase, sensitization, serotonin, synaptosome, cyclic nucleotide, CREB, gene expression, sensory neuron

Introduction

The cAMP second-messenger pathway is critical for learning and synaptic plasticity (Kandel and Schwartz, 1982; Goodwin et al., 1997; Hensch et al., 1998). The central component in this pathway is the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), a tetramer consisting of a homodimer of two regulatory (R) and two catalytic (C) subunits. Animals have two types of PKA, which differ in R subunits (RI and RII; Corbin et al., 1975a,b; Hofmann et al., 1975; Ebert and Finn, 1981). Even though encoded by different genes (Cadd and McKnight, 1989; McKnight, 1991), both types of R subunits from yeast to humans are conservatively built: the C-terminal two-thirds of the molecule contain two cAMP-binding sites connected to the N-terminal domain by a hinge region with the inhibitory binding site for the C subunit. The N-terminal portion of R subunits contains a variable PEST sequence and a site where the subunits dimerize; in RII subunits, it also contains a binding site for A kinase-anchoring proteins (AKAPs; Taylor et al., 1990).

The two types of PKA were first recognized by their sequence of elution during ion exchange column chromatography (Hofmann et al., 1975), and have similar biochemical and kinetic properties (substrate preference, nucleotide triphosphate specificity, and affinity for ATP), presumably because these are chiefly features of the C subunits that are shared by both types of R. Unlike RI, RII is autophosphorylated at the hinge region (Durgerian and Taylor, 1989) in a process that is independent of cAMP (Erlichman et al., 1974; Rangel-Aldao and Rosen, 1976). The intracellular distribution of the kinases differs: type I is mainly cytosolic, whereas most of type II is bound to membranes through the association of RII subunits with AKAPs (Cheley et al., 1994; Dell'Acqua and Scott, 1997; Pawson and Scott, 1997; Schwartz, 2001; Michel and Scott, 2002).

In Aplysia, behavioral sensitization of defensive reflexes is produced by presynaptic facilitation (both short- and long-term) of sensory → motor synapses (Byrne and Kandel, 1996; Kandel, 2001). PKA is essential for both forms (Castellucci et al., 1980; Kandel and Schwartz, 1982; Schacher et al., 1988; Conn et al., 1989). In short-term facilitation produced by brief application of a facilitatory neurotransmitter serotonin (5-HT), activation of PKA leads to the phosphorylation of existing synaptic proteins, resulting in enhanced transmitter release (Shimahara and Tauc, 1978; Castellucci et al., 1982; Shuster et al., 1985). During long-term facilitation produced by repeated applications of 5-HT, PKA remains activated for at least 24 hr (Greenberg et al., 1987; Sweatt and Kandel, 1989; Muller and Carew, 1998). This persistent activation, the result of ubiquitin-mediated degradation of RI subunits with no change in C (Chain et al., 1995, 1999), leads to persistent phosphorylation of the transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), which regulates the expression of genes necessary for long-lasting functional and structural synaptic changes (Bartsch et al., 1998).

The biochemical properties of PKA R subunits in Aplysia nervous tissue were first characterized by Eppler et al. (1986). Bergold et al. (1992) cloned and characterized N4, an Aplysia RI. Cheley et al. (1994) then showed that Aplysia RII subunits are autophosphorylated and bind AKAPs. Does type II PKA have distinctive roles in the synaptic facilitation produced by 5-HT? We have now cloned Aplysia RII and show that it is enriched at terminals where it binds AKAPs. Unlike RI protein, which is degraded during long-term facilitation (Greenberg et al., 1987; Bergold et al., 1992; Chain et al., 1995, 1999), RII protein and its mRNA increase. In addition, the binding of RII to AKAPs is critical for the expression of both short- and long-term facilitation. Thus, the two types of PKA play distinctive roles in producing plasticity at a behaviorally relevant synapse.

Materials and Methods

Animals and tissue preparation. Aplysia californica weighing 70-100 gm were from the Mariculture Resource Facility of the University of Miami (Miami, FL). Ganglia were dissected from animals anesthetized with Mg2+ (Schwartz and Swanson, 1987). RNA was isolated from tissues using the TRIzol reagent from Invitrogen (Rockville, MD). Reverse transcription was done with random hexamers using Superscript II reverse transcriptase from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). To stimulate animals, Aplysia was treated with 250 μm 5-HT for 2 hr at 18°C. This treatment has been used successfully to identify and study the induction and function of several important proteins shown to be critical for long-term synaptic plasticity: CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (Alberini et al., 1994), CREB isoforms (Bartsch et al., 1995, 1998), ubiquitin C terminal hydrolase (Hegde et al., 1997), ApAF (Bartsch et al., 2000), and p38 MAP kinase (Guan et al., 2003).

Synaptosomes were prepared by two-step sucrose gradient differential centrifugation (Chin et al., 1989). Protein was measured with a Micro BCA kit from Pierce (Rockford, IL) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard. Immunoblotting was performed as described previously (Liu and Schwartz, 2003).

Primers and oligonucleotides. All of the following primers and oligonucleotides were synthesized by Invitrogen: R2-DGF, 5′-GCNARRAARMGNARRATGTWYGA; R2-DGR, 5′-TTNCKYTTCATDATYTCCAT; R2-3 reverse (R), 5′-GACGCGCTCAGCTCCCAGACCTTCC; R2-5R, 5′-CTGCCAACTTCGTAACGCCCACAG; Q-R2 forward (F), 5′-GTGATTTCCCCCATCGCAGCATTAT; Q-R2R, 5′-GCACAGCAACGGTGAACTCC; Q-Aplysia cell adhesion protein (ApCAM)F, 5′-AGGATGATGTGACGCCGTTTG; Q-ApCAMR, 5′-ACCTGGTCGGAGGTTGCAGAG; Q-18SF, 5′-GATTACGTCCCTGCCCTTTG; Q-18SR, 5′-GATCGAGTTCGAGCGTCTTCT; R2-AS, 5′-CGCCGCTGTTCGTCCGACTTGGG; N4-AS, 5′-CGAAACTGCCGCCCTCGCCGATACT; GW-N4, 5′-CTTGAGGCTTTGCTCCTCGTCGGTGTTG; GW-R2, 5′-CACTTTGCACAAGAATACGTTATGAATC; B-R2, 5′-biotin-CGTAAGAACGACTAAACCGACGATAATGCTGCGAT; and B-N4, 5′-biotin-CGAAACTGCCGCCCTCGCCGATACTGGTCACAT.

Cell culture and electrophysiology. Sensory neurons were isolated from pleural ganglia dissected from adult animals (80-100 gm); L7 motor cells were isolated from juvenile (1-3 gm) abdominal ganglia and maintained in culture for 5 d (Rayport and Schacher, 1986). Cocultures consisted of one or two sensory neurons with one L7.

We used standard electrophysiological techniques to record the amplitudes of the EPSPs evoked in L7 with the stimulation of each sensory neuron (Schacher and Montarolo, 1991). Motor cells were impaled with a microelectrode (resistance, 15-20 MΩ) containing 2.0 m K+ acetate, 0.5 m KCl, and 10 mm K+-HEPES, pH 7.4, and held at -80 mV. Each sensory neuron was stimulated with a brief (0.3-0.5 msec) depolarizing pulse to evoke an action potential with an extracellular electrode near the sensory neuron cell body. Short-term facilitation was produced with a single 50 μl application of 50 μm 5-HT from a pipette placed 0.2 mm from the cells. The final concentration reaching the cells was ∼5 μm. Sensory neurons were stimulated four times at 1 min intervals, and 5-HT was applied after the third stimulus. To produce long-term facilitation in cultures, neurons were treated with bath-applied 5 μm 5-HT five times for 5 min each at 20 min intervals after testing the EPSP amplitude (Montarolo et al., 1986). Cultures were incubated at 18°C and tested again 24 hr later.

Antisense oligonucleotides R2-AS for Aplysia RII (ApRII) and N4-AS for ApRI were pressure-injected into cell bodies 4-6 hr before 5-HT treatment (Hu et al., 2002). These two oligonucleotides, which are free of secondary structures and false priming sites, were chosen using the PrimerSelect program from DNAStar (Madison, WI). The oligonucleotides were dissolved in 0.5 m KCl and 10 mm K+-HEPES, pH 7.4, at a concentration of 0.3 mm.

To inhibit the interaction between the RII subunit and AKAP (Vijayaraghavan et al., 1997), we used the stearated form of the Ht31 inhibitory peptide (S-Ht31) and the control peptide (S-Ht31P), which is inactivated by site-specific proline mutations (both from Promega, Madison, WI). The presence of the lipid moiety makes the peptide membrane-permeable. In experiments examining the action of AKAP-RII in short-term facilitation, cultured neurons were incubated with 20 μm S-Ht31 or S-Ht31P for 30 min after testing the initial EPSP amplitude. This short incubation did not interfere with baseline synaptic transmission (data not shown). In experiments testing the role of AKAP-RII interaction in long-term facilitation, 2 μm S-Ht31 or S-Ht31P was added to the culture medium immediately after the 5-HT treatment and was left in the medium until the recording session on the next day. We used the lower concentration because preliminary experiments indicated that prolonged exposure to higher concentrations of Ht31 peptide is toxic. Long-term treatment at this lower concentration had no effect on baseline synaptic transmission. Ht31 peptide (Carr et al., 1992) (Neosystem, Strasbourg, France), which is not membrane-permeable, was injected directly into sensory neurons dissolved in 0.5 m KCl and 10 mm K+-HEPES, pH 7.4, at a concentration of 5 μm. In these experiments, the experimenter was not informed about the identity of the injected compounds.

We pressure injected peptides and oligonucleotides into sensory neurons with intracellular electrodes (resistance, 10-15 MΩ) using 50 msec pulses at 5-7 psi. The sensory neurons were hyperpolarized to -70 mV. Movement of material into the neurons was confirmed by the response of a small depolarization of 3-5 mV with each pressure pulse. Each cell was subjected to 50 pressure pulses given at 2 sec intervals.

Cloning of ApRII. The sequences of degenerate primers R2-DGF and R2-DGR were based on conserved regions of human RIIα and RIIβ and Drosophila RII (GenBank accession numbers P13861, P31323, and AAF58862). These primers were used in reverse transcription (RT)-PCR reactions with a temperature profile of 94°C (30 sec), 55°C (30 sec), and 72°C (60 sec) for 35 cycles. Random hexamer-primed Aplysia neuronal cDNA was used as template. A 400 bp DNA fragment was isolated that encoded a predicted part of RII. The full sequence was obtained by 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) performed with Aplysia sensory neuron cDNA and gene-specific primers R2-3R (for 3′ RACE) and R2-5R (for 5′ RACE) using the SMART RACE cDNA amplification kit from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). This sequence has been deposited in GenBank (accession number AY387673). The entire 5′ untranslated region of the ApRII gene was obtained using the First Choice RNA ligase-mediated RACE kit (Ambion, Austin, TX).

Antibodies. A rabbit anti-ApRII antibody was raised and affinity-purified by BioSource International (Hopkinton, MA) using a peptide (N-KLSGALRFQENDTVNI-C corresponding to Lys48-Ile63 of ApRII) conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin as an immunogen. The amino acid sequence of ApRII was analyzed using the Protean program from DNAStar to calculate the surface probability and antigenic index. The peptide was chosen to have both a high surface probability and antigenic index. The RI (N4) antibody was described by Chain et al. (1999).

The RII overlay assay was done as described by Bregman et al. (1989). Briefly, bovine heart RII (10 μg; Promega) was phosphorylated by PKA C subunits (1.4 μg; Promega) in 0.1 ml of 25 mm K+ phosphate, pH 7.0, 10 mm Mg+ acetate, 2 mm DTT, 10 μm cAMP, and 60 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, 6000 Ci/mmol. Labeled RII was purified using a G-50 column (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) equilibrated with 10 mm PBS, pH 7.4. Eluted protein was stored at -70°C. After they were separated by SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were first blocked in PBS milk-BSA (10 mm PBS, pH 7.4, containing 5% nonfat dry milk, 0.1% BSA, and 0.1% antifoam; Sigma) for 3 hr at room temperature and then incubated with labeled RII (60 μl, 0.1 μg/ml) in 10 ml of PBS milk-BSA overnight at 4°C. After they were washed three times with PBS milk-BSA and twice with PBS at room temperature, the membranes were dried and autoradiographed.

RT-PCR in neurites. Total RNA from neurites (the cell body removed by dissection) was isolated in TRIzol. Reverse transcription was done with random primers, and the resulting cDNA was used as templates for PCR. Gene-specific primer sets were used to amplify specific genes (Schacher et al., 1999). These primer sets were Q-R2F and Q-R2R for ApRII and Q-ApCAMF and Q-ApCAMR for ApCAM (Mayford et al., 1992).

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using a GeneAmp 5700 sequencing detecting system and SYBR-Green quantitative PCR kit from PE Biosystems (Foster City, CA). The amounts of RII mRNA in each tissue were normalized to an internal standard (18S ribosomal RNA, indicating the amount of total RNA). Gene-specific primer sets were used to amplify specific genes. These primer sets were: Q-R2F and Q-R2R for ApRII and Q-18SF and Q-18SR for 18 S ribosomal RNA (Medina et al., 2001).

Isolation of gene promoters. The promoters of Aplysia RI and RII genes were isolated with a Universal GenomeWalker kit (Clontech). Purified Aplysia genomic DNA was digested with blunt-end restriction enzymes and ligated to an adaptor that contained the primer sequences used for PCR amplification. The resulting ligated DNA served as templates in PCR reactions with gene-specific primers for Aplysia RI (GW-N4) and RII (GW-R2). The PCR products were cloned into the pCR 2.1 vector (Invitrogen), and the resulting plasmids were purified and sequenced to obtain the inserted DNA sequences.

Immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization. After they were fixed in 0.1 m PBS, pH 7.4, containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 30% sucrose for 1 hr and rinsed with 0.01 m PBS, pH 7.4, cultured neurons were blocked at room temperature with 0.01 m PBS, pH 7.4, containing 0.2% Triton X-100 and 3% normal goat serum for 1 hr and then incubated with anti-ApRII antibody (1:1000 dilution) overnight at 4°C in 0.01 m PBS, pH 7.4, 1% normal goat serum, and 0.2% Triton X-100. After they were washed three times with 0.01 m PBS for 5 min, the neurons were treated at room temperature with Cy3-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:200 dilution) for 4 hr and washed three times with 0.01 m PBS before photography.

In situ hybridization was done as described by Hu et al. (2002) with probes B-R2 for RII and B-N4 for RI. These probes were labeled at the 5′ end with biotin (Invitrogen). Cultures were rinsed briefly in artificial seawater and fixed in 0.1 m PBS, pH 7.4, containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 30% sucrose at room temperature for 1 hr. The cultures were washed in 0.1 m PBS three times at room temperature for 10 min, digested with 1 μg/ml proteinase K in 0.1 m Tris-HCl and 1 mm EDTA, pH 8.0, at 37°C for 20 min, and washed with 0.1 m PBS three times at room temperature for 10 min. The cells were postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m PBS at room temperature for 10 min and then washed three times at room temperature with 0.1 m PBS for 10 min. Cells were rinsed in 0.1 m triethanolamine, pH 8.0 (with 0.25% acetic anhydride) at room temperature for 10 min, equilibrated in 50% deionized formamide in 5× SSC, pH 7.2, at 42°C for 20 min, and hybridized overnight at 42°C in hybridization buffer (50% deionized formamide, 5× SSC, 0.02% SDS, and 2% blocking reagent) containing 1.5 μg/ml biotin-labeled oligonucleotide probes. Unbound probe was washed out with 2× SSC twice at 42°C for 15 min and with 0.1× SSC twice for 15 min at 50°C. After the cultures were equilibrated in buffer I (in m: 0.15 NaCl and 0.1 Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) for 2 min and with 0.15 m NaCl, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 2% normal goat serum in 0.1 m Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, at room temperature for 30 min, cells were incubated in streptavidin-FITC (1:200 dilution; Invitrogen) at 4°C for 4 hr. Unbound antibody was washed out with 0.1 m PBS three times at room temperature for 15 min.

Immunocytochemical and hybridization signals were detected directly by fluorescence microscopy and imaged with a Nikon (Tokyo, Japan) Diaphot microscope attached to a SIT (68; Dage-MTI, Michigan City, IN) video camera, processed by a Dell computer with a Vision Plus frame grabber, and then stored on compact disks. The same focal plane for each cell, centered at ∼15 μm above the surface of the dish, was photographed and analyzed. Preabsorption of the primary antibody with the antigen peptide, omitting the primary or secondary antibodies, was tested to verify the specificity of the staining for ApRII immunoreactivity. The specificity of staining with the biotin-labeled antisense oligonucleotide probe was tested either by substituting a labeled sense probe for the antisense probe or by incubating with excess unlabeled antisense probe.

Quantification and data analysis. We used NIH Scion software (Hu et al., 2002, 2003) to quantify average pixel intensities for hybridization and immunostaining signals of ApRII in sensory neuron cell bodies. Values for overall expression of ApRII mRNA or protein in each sample were determined by averaging pixel intensities in six areas over the cytoplasm (25 μm2 each) positioned at 12, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 o'clock. We normalized the intensity by dividing the pixel intensity obtained from each cell by the average intensity for the control population. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Changes in EPSP amplitude were normalized to the initial amplitude for each culture. The overall effects of treatments were determined by ANOVA, and specific differences between treatments were determined by the Scheffé multicomparison tests or paired t tests.

Results

Proper localization of type II PKA is essential for synaptic plasticity

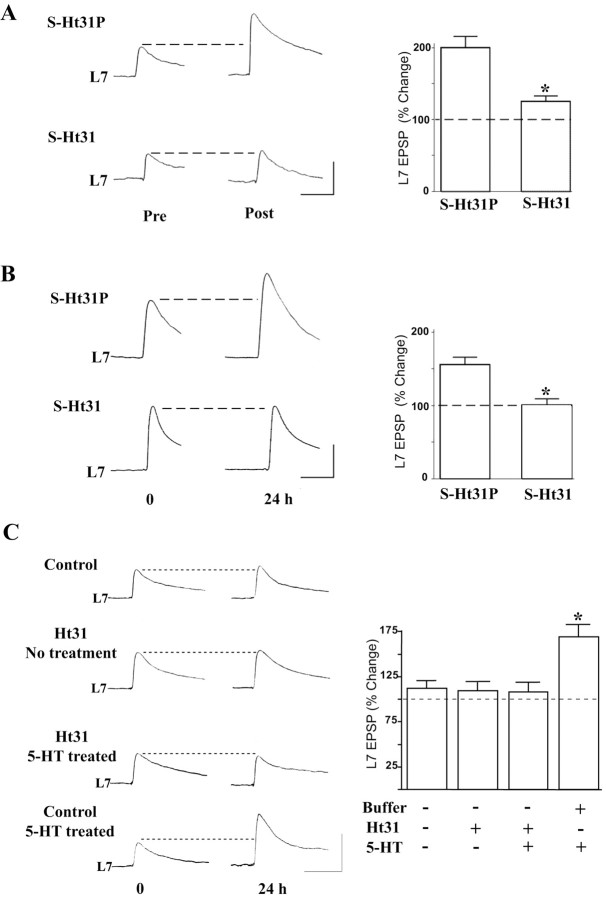

A single application of 5-HT produces short-term facilitation of sensory neuron synapses in sensory-L7 motor neuron cultures that lasts minutes (Rayport and Schacher, 1986), whereas five spaced pulses of 5-HT produce long-term facilitation lasting days (Montarolo et al., 1986; Martin et al., 1997). Cheley et al. (1994) showed that Aplysia type II PKA is bound to AKAPs, and that an AKAP peptide, Ht31, blocks the binding. We find that a membrane-permeable form of this peptide (S-Ht31) attenuates short-term facilitation (Fig. 1A). In the presence of S-Ht31, the EPSP amplitude increased by only 25.1 ± 8.1% (n = 10) after treatment with 5-HT compared with an expected increase of 95.5 ± 10.6% (n = 10) in the presence of S-Ht31P, an inactive control peptide. Because short-term facilitation is a local response restricted to sensory neuron-L7 terminals where the activity of PKA is essential (Shuster et al., 1985; Braha et al., 1990; Clark and Kandel, 1993; Emptage and Carew, 1993; Wu et al., 1995; Sun and Schacher, 1996; Sherff and Carew, 1999; Angers et al., 2002), this result suggests that disruption of the binding between RII and AKAPs at sensory neuron terminals prevents PKA from phosphorylating synaptic proteins that are critical for the plasticity.

Figure 1.

Disrupting ApRII-AKAP binding interferes with both short- and long-term facilitation. A, Incubation with S-Ht31 interferes with short-term facilitation. Representative EPSP traces were recorded in motor neuron L7 immediately before and 30 sec after the 5-HT treatment in the presence of the inactive (S-Ht31P) or inhibitory (S-Ht31) peptide. ANOVA indicates a significant effect of the treatment (df = 1, 18; F = 12.412; *p < 0.003). Individual comparison (Scheffé F test) indicates that S-Ht31 significantly reduced the change in EPSP amplitude (F = 15.597; p < 0.01). B, Incubation with S-Ht31 interferes with long-term facilitation. EPSP traces were recorded in L7 before and 24 hr after the 5-HT treatment in the presence of the control peptide (S-Ht31P) or the inhibitory peptide (S-Ht31). ANOVA indicates a significant effect of treatment (df = 1, 16; F = 32.02; p < 0.001), and individual comparison was significantly different (F = 17.063; *p < 0.01). C, Intracellular injection of Ht31 into sensory neurons blocks long-term facilitation produced by 5-HT. EPSP traces were recorded in L7 before and 24 hr after the treatment with 5-HT and sensory neurons injected with either buffer or Ht31. ANOVA indicates a significant effect of the treatment (df = 3, 24; F = 11.325; *p < 0.001). Individual comparisons (Scheffé F test) indicate that long-term facilitation was produced when 5-HT was applied to cultures whose sensory neurons were injected with buffer only (F = 3.230; p < 0.05 vs no treatment; F = 3.702; p < 0.05 vs injection of Ht31 only; and F = 4.152; p < 0.05 vs 5-HT and injection of Ht31). Calibration: 20 mV, 25 msec. The average amplitudes of the EPSP before each treatment were set as 100%.

Inhibition of the binding also abolished long-term facilitation (Fig. 1B). EPSP amplitudes measured 24 hr after starting the 5-HT treatment showed no increase in the presence of S-Ht31 (0.6 ± 8.8%; n = 9) compared with the expected increase with the inactive control peptide S-Ht31P (59.0 ± 9.7%; n = 9). Because S-Ht31 may affect the postsynaptic motor neuron, we also injected the peptide itself into sensory neurons. This nonpermeable Ht31 peptide confined to the sensory neuron also abolished long-term facilitation (Fig. 1C). The change in EPSP amplitude after treatment with 5-HT was only 8.2 ± 11% (n = 7) compared with 69.4 ± 10.4% when 5-HT was applied after injecting buffer alone (n = 7). These results indicate that inhibition of the motor neuron is not necessary for blocking the facilitation. Injection of Ht31 (9.2 ± 7.8%; n = 7) did not affect baseline synaptic transmission (buffer alone, 12.0 ± 9.7%; n = 7; Fig. 1C).

Characterization of the Aplysia type II R subunit

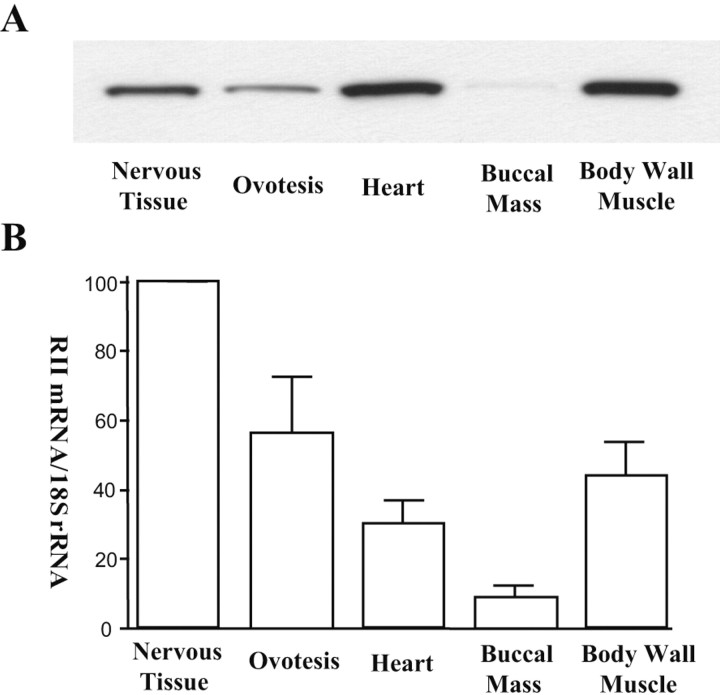

To compare the properties of the two types of R subunits and to examine their regulation as synaptic plasticity develops, we cloned an RII gene from Aplysia nervous tissue cDNA. With degenerate primers based on conserved sequences of human RIIα and RIIβ and Drosophila RII (GenBank accession numbers P13861, P31323, and AAF58862) using RT-PCR, a 400 bp fragment encoding RII was obtained. Gene-specific primers were then designed for 5′ and 3′ RACE PCR to obtain the full-length message. Aplysia RII cDNA is ∼3.2 kb long and encodes a protein with 396 amino acid residues and a calculated molecular weight of 44,600 (Fig. 2A). The predicted amino acid sequence is 67% identical to that of human RIIα and 62% identical to that of RIIβ. Phylogenetic analysis shows that ApRII is most closely related to Drosophila RII (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

The Aplysia RII gene. A, Nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequence of Aplysia RII. Autophosphorylation sites are highlighted. B, Phylogenetic analysis of R subunits. The predicated ApRII amino acid sequence was aligned using the MegAlign program from DNAStar with those of Drosophila RII (GenBank accession number AAF58862), human RIIα (P13861) and RIIβ (P31323), yeast R (CAA28726), Aplysia RI (CAA44246), human RIα (CAA01027), Caenorhabditis elegans RI (NP_508999), and Escherichia coli CAP (P03020) using the ClustralW method.

Like all R subunits, ApRII has two conserved cyclic nucleotide-binding sites: Ala150-Lys239 and Ala272-Asp369, distantly related to the bacterial cAMP-receptor protein (CAP) protein, and an N-terminal PEST domain, which is thought to be important for ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation (Rechsteiner and Rogers, 1996). As in its mammalian counterparts, ApRII has several putative autophosphorylation sites (Fig. 2A), one of them (Ser95) located in the hinge region between the N terminus and the cAMP-binding domains as in vertebrate RIIs (Durgerian and Taylor, 1989). The N-terminal domain of ApRII (Met1-Lys43) has sites both for dimerization and for binding AKAPs.

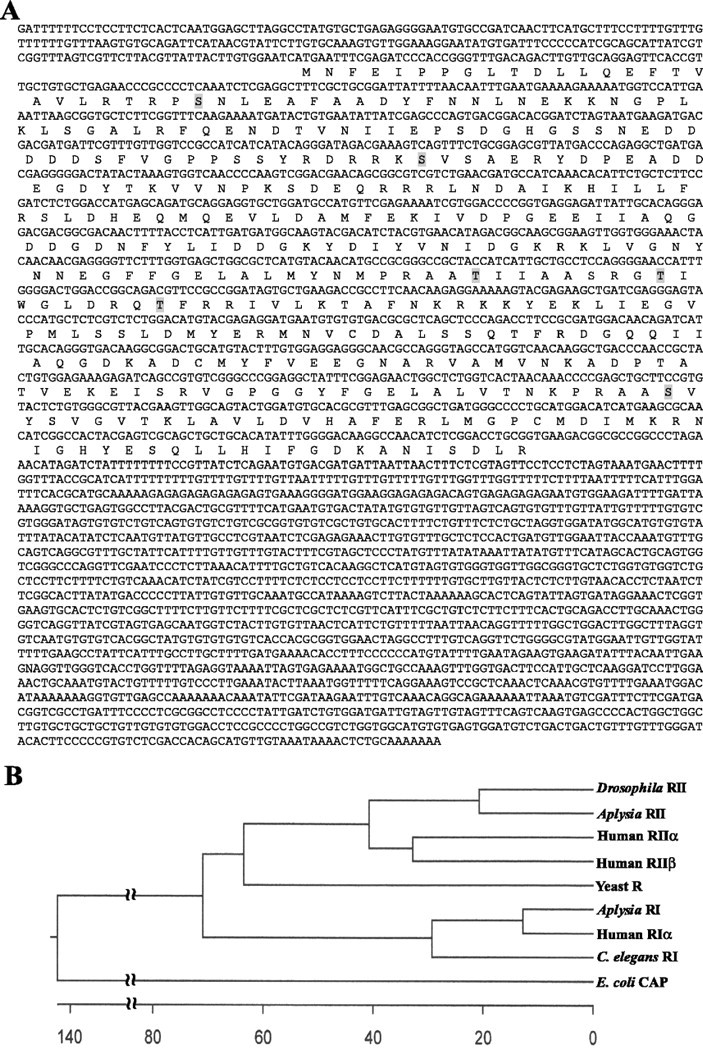

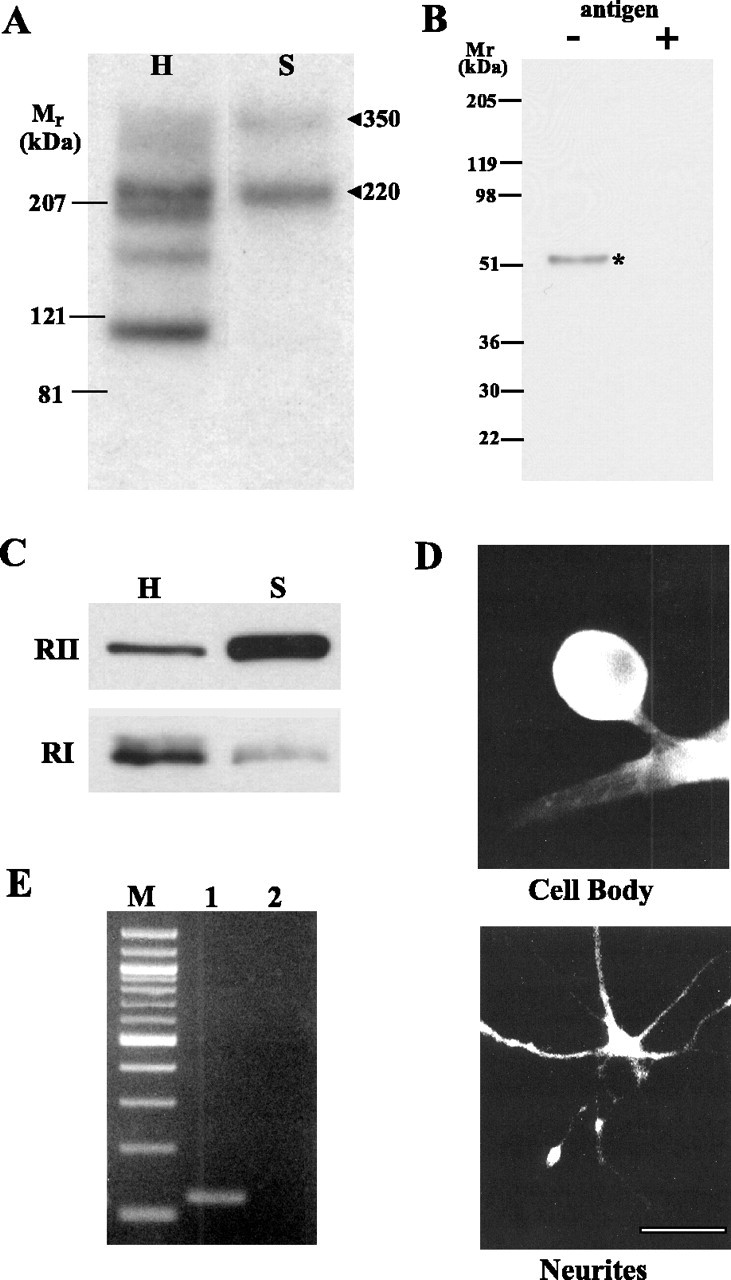

Cheley et al. (1994) showed that AKAPs and RII are present in Aplysia nervous tissue. On the basis of the apparent mobility of this protein in SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3B), the cloned Aplysia RII may be the Mr 50,000 autophosphorylated protein identified by Cheley et al. (1994). Using the RII overlay assay of Bregman et al. (1989), we also detected two AKAPs with Mr values of 220,000 and 350,000 that are enriched in synaptosomes (Fig. 3A). ApRII is also enriched in synaptosomes, but RI is not (Fig. 3C). The enrichment of ApRII in synaptosomes is greater than that in other membrane fractions (data not shown). Immunocytochemistry showed that ApRII protein is present in both the cell body and neurites of sensory neurons in culture (Fig. 3D). ApRII mRNA was also found in neurites by RT-PCR assay (Fig. 3E). These results indicate that RII is distributed differently from RI in sensory neurons. Moreover, because mRNAs transported into distal neurites of Aplysia neurons can be translated (Martin et al., 1997; Schacher and Wu, 2002; Liu et al., 2003), the RII protein may be synthesized locally at synapses.

Figure 3.

ApRII is enriched in neurites and synaptosomes along with two AKAPs. A, Autoradiographs showing the distribution of AKAPs in the nervous tissue homogenate (H) and synaptosomes (S). Synaptosomes were prepared as described by Chin et al. (1989). Proteins (80 μg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE on a 4-15% gradient gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for the overlay assay. B, An affinity-purified antibody raised against KLSGALRFQENDTVNI, a peptide from ApRII, recognizes a single Mr 52,000 component in homogenates of Aplysia nervous tissue. Preincubation of the antibody with the antigen peptide (10 μm final concentration, ∼200 times excess of the ApRII antibody) abolishes its interaction with the ApRII protein. C, Immunoblots show that ApRII is enriched in synaptosomes (S), and type I R is not. The amount of ApRII in synaptosomes is ∼2.5 times (267 ± 38%; n = 3; p < 0.05, paired Student's t test) that in the homogenate, whereas the amount of RI in synaptosomes is about one-fourth (23 ± 2.7%; n = 3; p < 0.001, paired t test) that in homogenate. H, Total homogenate from which the synaptosomes were prepared. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) from each fraction were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for immunoblotting with specific antibodies against ApRII. The same sample was also probed using Aplysia RI antibodies. These blots are representative of three similar experiments. D, Immunocytochemistry showed that ApRII protein immunoreactivity is present in both the cell body and neurites. Sensory neurons were cultured with either L7 (cell body) or alone (neurites). Detection of ApRII in neurites of sensory neurons in the presence of L7 is difficult because neurites of L7 also stain for ApRII. Scale bar, 50 μm. E, ApRII mRNA is present in neurites. Lane 1, ApRII; lane 2, ApCAM (Aplysia cell adhesion protein); M, 100 bp ladder. Total RNA was isolated from dissected neurites of cultured sensory neurons. After the synthesis of cDNA, PCR was performed with gene-specific primers. The ApCAM message was used as a negative control because it does not enter the neurites (Schacher et al., 1999; Liu and Schwartz, 2003). Its absence indicates that the RNA in a sample is not contaminated with components from the cell body.

ApRII is expressed in several Aplysia tissues. Immunoblotting showed that the protein is abundant in heart and body wall muscle, less abundant in neurons and ovotestis, and present only in small amounts in buccal mass muscle (Fig. 4A). Quantitative RT-PCR revealed that nervous tissue contains the greatest amount of ApRII mRNA, heart and body wall muscle having less than half the mRNA than that of nervous tissue. This result, together with the data on the tissue distribution of ApRII protein, suggests that ApRII mRNA in neurons is under translational regulation because some mRNA must be dormant, possibly to be activated by stimulation with 5-HT.

Figure 4.

Tissue distribution of ApRII mRNA and protein. A, ApRII protein. Equal amounts of total protein (20 μg) from extracts of each tissue were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for immunoblotting using the antibody against ApRII. The gel shown is representative of four similar experiments. Compared with its level in nervous tissue (set as 100), ApRII in protein is as follows: ovotestis, 61.5 ± 14.4; heart, 157.7 ± 17.0; buccal mass, 3.6 ± 1.1; and body wall muscle, 166.0 ± 19.9. B, ApRII mRNA. ApRII mRNA was assayed by quantitative RT-PCR. The amounts of RII mRNA in each tissue were normalized with an internal standard (18S ribosomal RNA). Error bars indicate SD (n = 3).

Increase in ApRII is critical for long-term facilitation

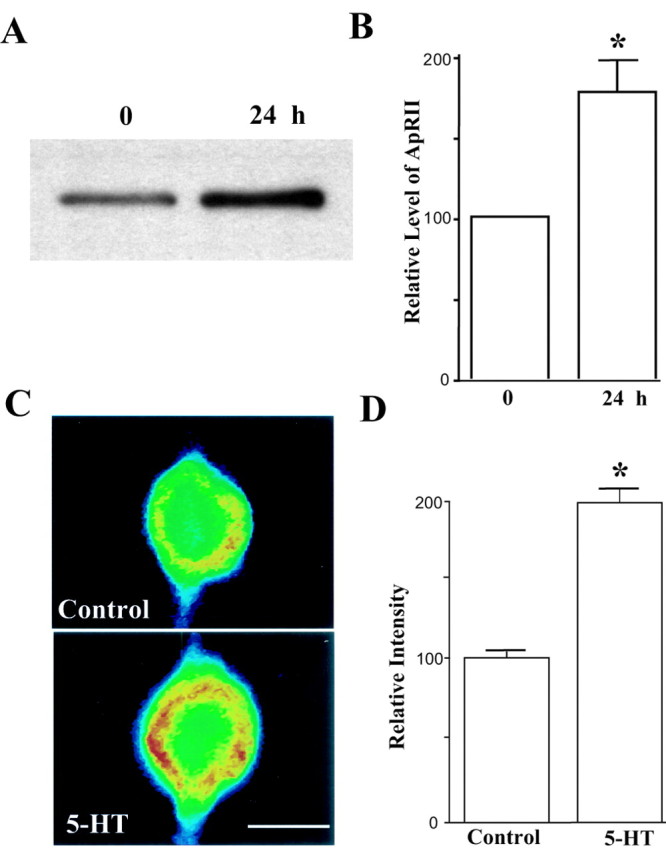

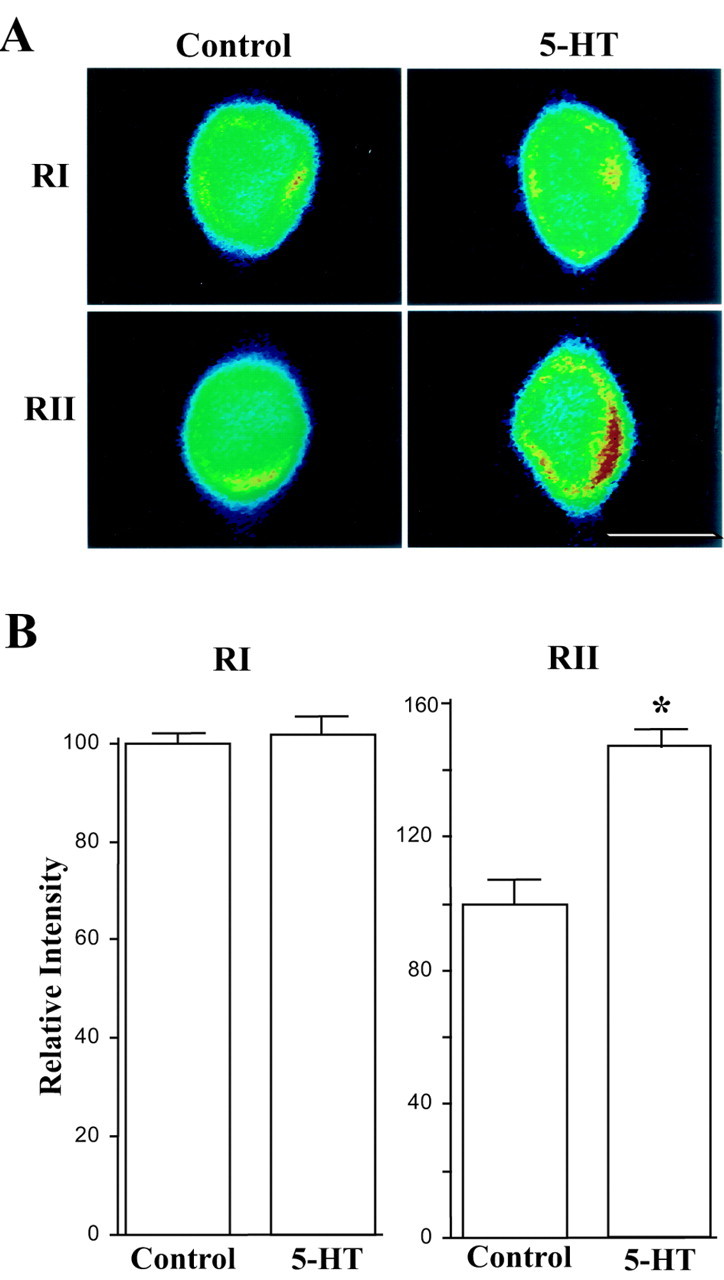

During long-term facilitation, Aplysia RI is degraded through ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated proteolysis with no change in amounts of its mRNA (Bergold et al., 1992; Chain et al., 1995, 1999). In contrast, when animals were treated with 5-HT, we found that ApRII was increased in synaptosomes isolated from pleural-pedal ganglia (Fig. 5A,B). In cultured sensory neurons ApRII-like immunoreactivity also increased 24 hr after the treatment with 5-HT, which produces long-term facilitation (Fig. 5C,D). Staining intensities for cells treated with 5-HT (n = 8) were 193.8 ± 7.8% greater than those for control treatment (n = 6). Expression of ApRII appears to be regulated by 5-HT through transcriptional control. In situ hybridization assays show that ApRII mRNA also increased 6 hr after the start of the 5-HT treatment (Fig. 6A,B). When compared with controls (n = 8), staining intensity for ApRII mRNA increased to 146.7 ± 5.0% after treatment with 5-HT (n = 11). Staining intensity for ApRI mRNA failed to increase with 5-HT (100.5 ± 2.9%; n = 11; vs 100.0 ± 1.8% for controls; n = 12). Thus, the increase of ApRII protein might result from an upregulation of transcription.

Figure 5.

ApRII protein increases after 5-HT treatment and long-term facilitation. A, ApRII increases in synaptosomes after the treatment of 5-HT. An immunoblot of ApRII in synaptosomes of pleural-pedal ganglia is shown. Samples prepared from untreated animals served as controls. The gels shown are representative of three similar experiments. B, Quantitation of relative changes in ApRII (mean ± SEM) in synaptosomes. The amounts of ApRII in controls were set as 100 (*p < 0.02, paired t test). Immunoblots were quantified using Eastman Kodak Co. (Rochester, NY) 1D gel image analysis software. C, ApRII immunoreactivity increases in sensory neurons 24 hr after treatment with 5-HT. Cocultures were fixed 24 hr after the start of the treatment and immunostained with the anti-ApRII antibody and Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Each micrograph shows the intensity of the fluorescence signals (false colors: red, high intensity; blue, low intensity). Scale bar, 50 μm. D, Quantitation of changes in ApRII (mean ± SEM) in cell bodies during long-term facilitation. The average intensity in controls was set as 100. Staining intensity after the 5-HT treatment was greater than that for the control (Scheffé F test, F = 81.094; *p < 0.01).

Figure 6.

ApRII mRNA increases with long-term facilitation. A, In situ hybridization of Aplysia RII and RI mRNAs in sensory neurons cocultured with motor neurons. Cells were fixed 6 hr after the start of the 5-HT treatment and probed using biotin-labeled Aplysia RII or RI antisense oligonucleotides. The pseudocolor micrograph shows the intensity of fluorescence (false colors: red, high; blue, low). B, Quantitation of changes in the in situ hybridization signal for ApRII and RI mRNAs during long-term facilitation. Average intensity for control cultures was set as 100%. ANOVA indicates a significant effect of treatment (df = 3, 38; F = 36.119; *p < 0.001). Individual comparisons indicate that no change in RI mRNA resulted from the treatment with 5-HT. The amounts of ApRII mRNA increased significantly after treatment with 5-HT (F = 20.775; p < 0.01).

The differences observed in the regulation of the two R subunits suggest that different transcriptional mechanisms regulate their expression. Examination of the promoter regions of these two genes supports this idea. We found a consensus cAMP response element (CRE) upstream of the transcription start site (TGACGTCA, -29 from the transcription starting site, GenBank accession number AY387674) in the promoter region of the ApRII gene, suggesting that transcription is initiated by the phosphorylation of CREB. In contrast, the upstream promoter region of the Aplysia RI gene (GenBank accession number AY387675) has no CRE but contains GC-rich elements (SP1 and AP2). Aplysia RI therefore appears to be a housekeeping gene like R subunit genes in other animals whose transcription normally is not regulated (Tasken et al., 1997).

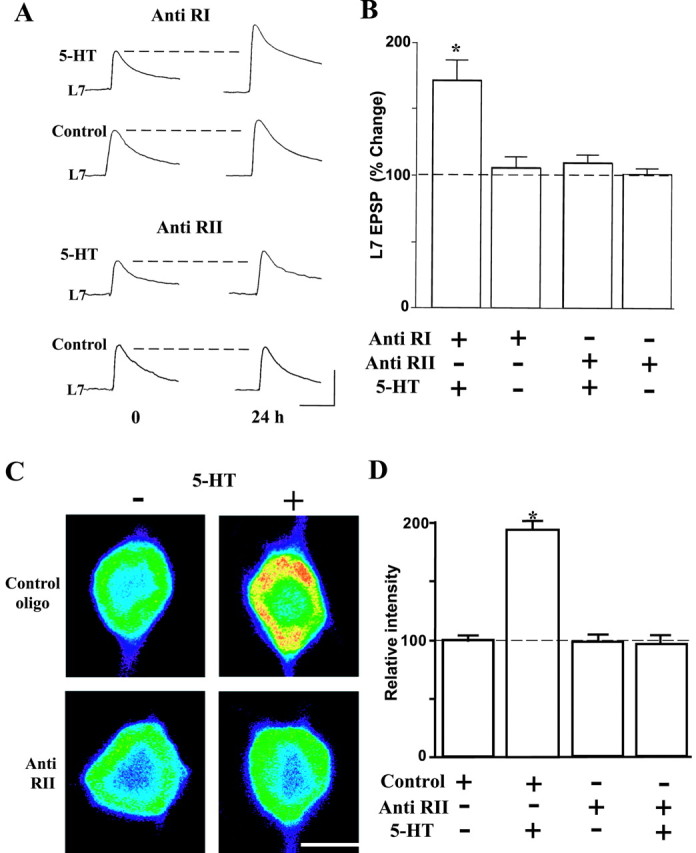

We find that the synthesis of new RII subunits is required for the expression of long-term facilitation (Fig. 7). Injection of antisense oligonucleotides complementary to ApRII mRNA prevented the long-term facilitation induced by 5-HT (EPSP changes of 9.1 ± 6.4%; n = 8; Fig. 7A,B). In contrast, injection of antisense oligonucleotides of the RI molecule had no effect on synaptic facilitation produced by 5-HT (EPSP changes of 71.3 ± 15.8%; n = 8). Neither RI nor RII antisense oligonucleotides had any effect on short-term facilitation when injected into sensory neurons (data not shown), nor did they block baseline synaptic transmission (Fig. 7; antisense oligonucleotides of RI, 3.6 ± 6.4%; n = 6; antisense oligonucleotides of RII, 1.0 ± 2.8%; n = 6). Using immunocytochemistry, we found that injection of antisense oligonucleotides complimentary to RII blocked the increase in ApRII protein produced by 5-HT (Fig. 7C,D). The average staining intensity for ApRII immunoreactivity in cells injected with control oligonucleotides and treated with 5-HT was 194.5 ± 5.9% (n = 6), greater than the staining intensity observed after injection of control oligonucleotide alone (100.0 ± 3.9%; n = 8). After injecting the antisense oligonucleotide, 5-HT failed to increase the intensity of ApRII immunoreactivity (95.8 ± 5.8%; n = 6) compared with control injections. Injection of antisense oligonucleotide without 5-HT treatment (n = 7) did not affect ApRII immunoreactivity (98.0 ± 4.5%). Thus, the increase in ApRII expression caused by 5-HT is important for long-term facilitation.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of ApRII synthesis by antisense oligonucleotides blocks long-term Facilitation. A, Injection of antisense oligonucleotides of ApRII blocked long-term facilitation produced by 5-HT. Shown are representative EPSP traces before and 24 hr after the start of the 5-HT treatment. Treatment with 5-HT began 4-5 hr after injections of antisense oligonucleotides (anti-RI, corresponding to a gene-specific region of the cAMP-binding domain-A, or anti RII, corresponding to a gene-specific region between the PEST region and cAMP-binding domain-A) into sensory neurons. Calibration: 20 mV, 25 msec. B, Summary of changes in EPSP amplitude (mean ± SEM) in L7 at 24 hr produced by the indicated treatments. ANOVA indicates significant effects of antisense oligonucleotide injection (df = 3, 24; F = 11.724; p < 0.001). Long-term facilitation was produced when 5-HT was applied to cultures whose sensory neurons were injected with anti RI oligonucleotides (F = 5.976; p < 0.01 vs injection of anti RI alone). No long-term facilitation occurred by 5-HT when anti RII oligonucleotides were injected. C, Injection of antisense oligonucleotides of ApRII blocked the increase in ApRII protein immunoreactivity produced by 5-HT. Injection of the control oligonucleotide failed to block the increase. Cultures were treated with or without 5-HT 4-5 hr after injection of antisense or control oligonucleotide. Cultures were fixed 24 hr after the start of the treatment and immunostained with the anti-ApRII antibody and Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Each micrograph represents the intensity of the fluorescence signals (false colors: red, high; blue, low). Long-term facilitation with 5-HT was detected only in cultures injected with the control oligonucleotide (data not shown). Scale bar, 50 μm. D, Quantitation of changes in ApRII immunoreactivity (mean ± SEM) in sensory neuron cell bodies during long-term facilitation. The average intensity in cultures injected with the control oligonucleotide was set as 100%. ANOVA indicated a significant effect of treatment (df = 3, 23; F = 88.194; p < 0.001). Cultures treated with 5-HT after injection with control oligonucleotides showed significantly greater signals than nontreated cultures (F = 62.615; p < 0.01) or cultures injected with antisense oligonucletides followed by 5-HT (F = 59.171; p < 0.01).

Discussion

We show that the activities of the two types of PKA in Aplysia sensory neurons have different but complimentary roles in producing synaptic plasticity at an identified synapse that underlies behavioral sensitization. The two types are distributed differently within sensory neurons, with type I primarily in cell bodies and type II at nerve endings. The two R subunits are regulated bidirectionally during long-term facilitation: RI decreases through ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated protein degradation without changes in the amounts of mRNA (Bergold et al., 1992), whereas RII appears to increase through transcription. The different base sequences of the regulatory promoter regions of the two Aplysia R genes suggest that transcription of RII is controlled by cAMP-dependent protein phosphorylation, whereas transcription of the RI gene is not regulated. Because type I PKA is persistently activated during long-term facilitation (Greenberg et al., 1987; Sweatt and Kandel, 1989; Muller and Carew, 1998; Chain et al., 1999), the upregulation of the RII gene may result from the persistent phosphorylation of CREB by type I PKA.

RII-AKAP binding and the compartmentalization of the cAMP-PKA cascade

A major long-recognized difference between the two PKA types is that type II associates with AKAPs to anchor the kinase, and type I is soluble. AKAPs constitute a family of functionally but not structurally related proteins. Each anchoring protein has a tethering site that strongly binds to the RII dimers and a distinct targeting domain that docks the AKAP-type II PKA complex to the plasmalemma or to organelles (Dell'Acqua and Scott, 1997; Pawson and Scott, 1997; Feliciello et al., 2001; Michel and Scott, 2002). Binding to AKAPs is thought to compartmentalize the kinase together with a functionally important substrate as well as effector proteins, for example, ion channels, other protein kinases, and adenylyl cyclase (for review, see Bers and Ziolo, 2001; Schwartz, 2001). This compartmentalization allows PKA to phosphorylate specific substrates rapidly often in concert with other kinases when cAMP is generated and to regulate different parts of a cell differently. In the hippocampus, for example, type II PKA is targeted to synaptic glutamate receptors, and phosphorylation of the Glu1 receptor subunit by type II PKA has been shown to regulate internalization and turnover of AMPA receptors (Colledge et al., 2000; Esteban et al., 2003). Docking of type II PKA at sensory neuron synapses may be critical for the expression of both short- and long-term facilitation because enhanced phosphorylation of the synaptic proteins that regulate neurotransmitter release is required.

Two likely synaptic substrates for PKA in Aplysia are the S-type K+ channel (Shuster et al., 1985) and synapsin (Angers et al., 2002). Phosphorylation of the channel by PKA produces hyperexcitability and broadening of the action potential (Shuster et al., 1985; Belardetti et al., 1987). In mammals, the functional homolog of the Aplysia S-type K+ channel (Twick-related K+ channel) is also modulated by PKA phosphorylation (Patel et al., 1998). The other substrate, synapsin, tethers synaptic vesicles to the cytoskeleton, providing a constraint for vesicle exocytosis that is relieved by phosphorylation (Hay et al., 2001; Ferreira and Rapoport, 2002). During the development of long-term facilitation, new connections form primarily by the growth of new branches and synapses (Hatada et al., 2000). PKA activity has been shown to be crucial for this neurite outgrowth (Schacher et al., 1993; Wu et al., 1995; Yao et al., 2000; Kao et al., 2002), as well as for the formation and maintenance of the new synapses (Wu et al., 1995). It is likely that type II PKA mediates these functions because this type is enriched and selectively positioned in neurites and nerve endings and because we found that disruption of RII-AKAP binding and blockade of RII synthesis prevents long-term facilitation.

The action of the two PKAs is complementary

Mechanisms for regulating the amounts of R and C subunits in cells have been investigated for the past two decades (Steinberg and Agard, 1981; Montminy, 1997; Amieux and McKnight, 2002). An important feature of this regulation is that the amounts of R should be kept approximately equimolar with the amounts of C because any great deviation would result in loss of regulation by cAMP. During long-term facilitation of sensory neuron synapses, C subunits remain constant, RII is induced, and RI decreases through ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. In sensory neuron cell bodies, the proteolysis of R subunits during long-term facilitation results in some C that is unregulated. The new synthesis of the RII subunit may be induced through phosphorylation of CREB by this persistently active kinase activity. If so, the molecular mechanism underlying learning makes use of a general compensatory mechanism evolved for maintaining the balance between R and C subunits.

It is not yet clear whether all of the new RII protein molecules are made in the cell body. Because RII mRNA is transported to synapses, some RII protein may be synthesized locally. This synthesis can be synapse-specific (Schacher et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2003) and need not occur at all connections of a neuron. Rather, it could occur selectively at synapses that have been previously activated. Thus newly synthesized type II PKA may be a molecular mark suggested by Casadio et al. (1999) that distinguishes previously active synapses from all the other synapses of a neuron.

Our experiments provide evidence for the novel idea that two isoforms of the same enzyme, each with distinctive functions within a cell, cooperate to produce a common physiological end (facilitation). Distinctive responses of the two types of PKA to ethanol treatment were seen in cultured neuroblastoma-X-glioma cells by Constantinescu et al. (2002), who found that type II PKA is translocated to the nucleus to phosphorylate CREB, whereas type I remains in the cytoplasm to activate other transcription cofactors that then interact with phosphorylated CREB. In Aplysia sensory neurons, the functions of the two types of R differ primarily because of the polarity of neurons, type I PKA operating in the cell body and type II at nerve terminals. Anchoring of RII subunits at terminals by AKAPs appears to be responsible for the chief difference between the targets of the two types of PKA. We suggest that type II kinase, enriched at synapses, phosphorylates synaptic components selectively. Type I kinase may also phosphorylate these components, but less efficiently: its special function is likely to be in the nucleus to phosphorylate transcription factors for initiating and maintaining the gene expression cascade required for long-term facilitation. One component of that cascade, the induction of new RII subunits, provides sensory neuron synapses with more type II PKA.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grant MH15174 (J.L.), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant MH48850 (J.H.S.), and NIMH Grant MH60387 (S.S.). Animals were provided by the National Center for Research Resources National Resource for Aplysia at the University of Miami under National Institutes of Health Grant RR1029. We thank Dr. Hagan Bayley, Dr. Ivan Diamond, and Dr. Wayne Sossin for reading this manuscript critically, Jason Tsai and Fang Wu for technical help, and Eve Vagg and Rachel Yarmolinsky for artwork.

Correspondence should be addressed to James H. Schwartz at the above address. E-mail: jhs6@columbia.edu.

Copyright © 2004 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/04/242465-10$15.00/0

References

- Alberini CM, Ghirardi M, Metz R, Kandel ER (1994) C/EBP is an immediate-early gene required for the consolidation of long-term facilitation in Aplysia. Cell 76: 1099-1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amieux PS, McKnight GS (2002) The essential role of RI alpha in the maintenance of regulated PKA activity. Ann NY Acad Sci 968: 75-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angers A, Fioravante D, Chin J, Cleary LJ, Bean AJ, Byrne JH (2002) Serotonin stimulates phosphorylation of Aplysia synapsin and alters its subcellular distribution in sensory neurons. J Neurosci 22: 5412-5422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch D, Ghirardi M, Skehel PA, Karl KA, Herder SP, Chen M, Bailey CH, Kandel ER (1995) Aplysia CREB2 represses long-term facilitation: relief of repression converts transient facilitation into long-term functional and structural change. Cell 83: 979-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch D, Casadio A, Karl KA, Serodio P, Kandel ER (1998) CREB1 encodes a nuclear activator, a repressor, and a cytoplasmic modulator that form a regulatory unit critical for long-term facilitation. Cell 95: 211-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch D, Ghirardi M, Casadio A, Giustetto M, Karl KA, Zhu H, Kandel ER (2000) Enhancement of memory-related long-term facilitation by ApAF, a novel transcription factor that acts downstream from both CREB1 and CREB2. Cell 103: 595-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardetti F, Kandel ER, Siegelbaum SA (1987) Neuronal inhibition by the peptide FMRFamide involves opening of S K+ channels. Nature 325: 153-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergold PJ, Beushausen SA, Sacktor TC, Cheley S, Bayley H, Schwartz JH (1992) A regulatory subunit of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase down-regulated in Aplysia sensory neurons during long-term sensitization. Neuron 8: 387-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers DM, Ziolo MT (2001) When is cAMP not cAMP? Effects of compartmentalization. Circ Res 89: 373-375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braha O, Dale N, Hochner B, Klein M, Abrams TW, Kandel ER (1990) Second messengers involved in the two processes of presynaptic facilitation that contribute to sensitization and dishabituation in Aplysia sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 2040-2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bregman DB, Bhattacharyya N, Rubin CS (1989) High affinity binding protein for the regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase II-B: cloning, characterization, and expression of cDNAs for rat brain P150. J Biol Chem 264: 4648-4656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne JH, Kandel ER (1996) Presynaptic facilitation revisited: state and time dependence. J Neurosci 16: 425-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadd G, McKnight GS (1989) Distinct patterns of cAMP-dependent protein kinase gene expression in mouse brain. Neuron 3: 71-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DW, Hausken ZE, Fraser ID, Stofko-Hahn RE, Scott JD (1992) Association of the type II cAMP-dependent protein kinase with a human thyroid RII-anchoring protein: cloning and characterization of the RII-binding domain. J Biol Chem 267: 13376-13382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadio R, Polverini E, Mariani P, Spinozzi F, Carsughi F, Fontana A, Polverino de Laureto P, Matteucci G, Bergamini CM (1999) The structural basis for the regulation of tissue transglutaminase by calcium ions. Eur J Biochem 262: 672-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellucci VF, Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Wilson FD, Nairn AC, Greengard P (1980) Intracellular injection of the catalytic subunit of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase simulates facilitation of transmitter release underlying behavioral sensitization in Aplysia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 77: 7492-7496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellucci VF, Nairn A, Greengard P, Schwartz JH, Kandel ER (1982) Inhibitor of adenosine 3′:5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase blocks presynaptic facilitation in Aplysia. J Neurosci 2: 1673-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chain DG, Hegde AN, Yamamoto N, Liu-Marsh B, Schwartz JH (1995) Persistent activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase by regulated proteolysis suggests a neuron-specific function of the ubiquitin system in Aplysia. J Neurosci 15: 7592-7603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chain DG, Casadio A, Schacher S, Hegde AN, Valbrun M, Yamamoto N, Goldberg AL, Bartsch D, Kandel ER, Schwartz JH (1999) Mechanisms for generating the autonomous cAMP-dependent protein kinase required for long-term facilitation in Aplysia. Neuron 22: 147-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheley S, Panchal RG, Carr DW, Scott JD, Bayley H (1994) Type II regulatory subunits of cAMP-dependent protein kinase and their binding proteins in the nervous system of Aplysia californica. J Biol Chem 269: 2911-2920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin GJ, Shapiro E, Vogel SS, Schwartz JH (1989) Aplysia synaptosomes. I. Preparation and biochemical and morphological characterization of subcellular membrane fractions. J Neurosci 9: 38-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark GA, Kandel ER (1993) Induction of long-term facilitation in Aplysia sensory neurons by local application of serotonin to remote synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 11411-11415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colledge M, Dean RA, Scott GK, Langeberg LK, Huganir RL, Scott JD (2000) Targeting of PKA to glutamate receptors through a MAGUK-AKAP complex. Neuron 27: 107-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn PJ, Strong JA, Azhderian EM, Nairn AC, Greengard P, Kaczmarek LK (1989) Protein kinase inhibitors selectively block phorbol ester- or forskolin-induced changes in excitability of Aplysia neurons. J Neurosci 9: 473-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu A, Gordon AS, Diamond I (2002) cAMP-dependent protein kinase types I and II differentially regulate cAMP response element-mediated gene expression: implications for neuronal responses to ethanol. J Biol Chem 277: 18810-18816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JD, Keely SL, Park CR (1975a) The distribution and dissociation of cyclic adenosine 3′:5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinases in adipose, cardiac, and other tissues. J Biol Chem 250: 218-225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JD, Keely SL, Soderling TR, Park CR (1975b) Hormonal regulation of adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Adv Cyclic Nucleotide Res 5: 265-279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Acqua ML, Scott JD (1997) Protein kinase A anchoring. J Biol Chem 272: 12881-12884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durgerian S, Taylor SS (1989) The consequences of introducing an autophosphorylation site into the type I regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 264: 9807-9813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert RF, Finn FM (1981) Isolation and characterization of two adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinases from bovine adrenal cortex. Endocrinology 109: 197-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emptage NJ, Carew TJ (1993) Long-term synaptic facilitation in the absence of short-term facilitation in Aplysia neurons. Science 262: 253-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppler CM, Bayley H, Greenberg SM, Schwartz JH (1986) Structural studies on a family of cAMP-binding proteins in the nervous system of Aplysia. J Cell Biol 102: 320-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlichman J, Rosenfeld R, Rosen OM (1974) Phosphorylation of a cyclic adenosine 3′:5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase from bovine cardiac muscle. J Biol Chem 249: 5000-5003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban JA, Shi SH, Wilson C, Nuriya M, Huganir RL, Malinow R (2003) PKA phosphorylation of AMPA receptor subunits controls synaptic trafficking underlying plasticity. Nat Neurosci 6: 136-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciello A, Gottesman ME, Avvedimento EV (2001) The biological functions of A-kinase anchor proteins. J Mol Biol 308: 99-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A, Rapoport M (2002) The synapsins: beyond the regulation of neurotransmitter release. Cell Mol Life Sci 59: 589-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin SF, Del Vecchio M, Velinzon K, Hogel C, Russell SR, Tully T, Kaiser K (1997) Defective learning in mutants of the Drosophila gene for a regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Neurosci 17: 8817-8827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg SM, Castellucci VF, Bayley H, Schwartz JH (1987) A molecular mechanism for long-term sensitization in Aplysia. Nature 329: 62-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Z, Kim JH, Lomvardas S, Holick K, Xu S, Kandel ER, Schwartz JH (2003) p38 MAP kinase mediates both short-term and long-term synaptic depression in Aplysia. J Neurosci 23: 7317-7325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatada Y, Wu F, Sun ZY, Schacher S, Goldberg DJ (2000) Presynaptic morphological changes associated with long-term synaptic facilitation are triggered by actin polymerization at preexisting varicositis. J Neurosci 20: RC82(1-5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay M, Hoang CJ, Pamidimukkala J (2001) Cellular mechanisms regulating synaptic vesicle exocytosis and endocytosis in aortic baroreceptor neurons. Ann NY Acad Sci 940: 119-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde AN, Inokuchi K, Pei W, Casadio A, Ghirardi M, Chain DG, Martin KC, Kandel ER, Schwartz JH (1997) Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase is an immediate-early gene essential for long-term facilitation in Aplysia. Cell 89: 115-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK, Gordon JA, Brandon EP, McKnight GS, Idzerda RL, Stryker MP (1998) Comparison of plasticity in vivo and in vitro in the developing visual cortex of normal and protein kinase A RI beta-deficient mice. J Neurosci 18: 2108-2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann F, Beavo JA, Bechtel PJ, Krebs EG (1975) Comparison of adenosine 3′:5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinases from rabbit skeletal and bovine heart muscle. J Biol Chem 250: 7795-7801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JY, Meng X, Schacher S (2002) Target interaction regulates distribution and stability of specific mRNAs. J Neurosci 22: 2669-2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JY, Meng X, Schacher S (2003) Redistribution of syntaxin mRNA in neuronal cell bodies regulates protein expression and transport during synapse formation and long-term synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci 23: 1804-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER (2001) The molecular biology of memory storage: a dialogue between genes and synapses. Science 294: 1030-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER, Schwartz JH (1982) Molecular biology of learning: modulation of transmitter release. Science 218: 433-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao HT, Song HJ, Porton B, Ming GL, Hoh J, Abraham M, Czernik AJ, Pieribone VA, Poo MM, Greengard P (2002) A protein kinase A-dependent molecular switch in synapsins regulates neurite outgrowth. Nat Neurosci 5: 431-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Schwartz JH (2003) The cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein and polyadenylation of messenger RNA in Aplysia neurons. Brain Res 959: 68-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Hu JY, Wang D, Schacher S (2003) Protein synthesis at synapse versus cell body: enhanced but transient expression of long-term facilitation at isolated synapses. J Neurobiol 56: 275-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin KC, Casadio A, Zhu H, Yaping E, Rose JC, Chen M, Bailey CH, Kandel ER (1997) Synapse-specific, long-term facilitation of Aplysia sensory to motor synapses: a function for local protein synthesis in memory storage. Cell 91: 927-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayford M, Barzilai A, Keller F, Schacher S, Kandel ER (1992) Modulation of an NCAM-related adhesion molecule with long-term synaptic plasticity in Aplysia. Science 256: 638-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight GS (1991) Cyclic AMP second messenger systems. Curr Opin Cell Biol 3: 213-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina M, Collins AG, Silberman JD, Sogin ML (2001) Evaluating hypotheses of basal animal phylogeny using complete sequences of large and small subunit rRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 9707-9712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel JJ, Scott JD (2002) AKAP mediated signal transduction. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 42: 235-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montarolo PG, Goelet P, Castellucci VF, Morgan J, Kandel ER, Schacher S (1986) A critical period for macromolecular synthesis in long-term heterosynaptic facilitation in Aplysia. Science 234: 1249-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montminy M (1997) Transcriptional regulation by cyclic AMP. Annu Rev Biochem 66: 807-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller U, Carew TJ (1998) Serotonin induces temporally and mechanistically distinct phases of persistent PKA activity in Aplysia sensory neurons. Neuron 21: 1423-1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AJ, Honore E, Maingret F, Lesage F, Fink M, Duprat F, Lazdunski M (1998) A mammalian two pore domain mechano-gated S-like K+ channel. EMBO J 17: 4283-4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson T, Scott JD (1997) Signaling through scaffold, anchoring, and adaptor proteins. Science 278: 2075-2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-Aldao R, Rosen OM (1976) Mechanism of self-phosphorylation of adenosine 3′:5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase from bovine cardiac muscle. J Biol Chem 251: 7526-7529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayport SG, Schacher S (1986) Synaptic plasticity in vitro: cell culture of identified Aplysia neurons mediating short-term habituation and sensitization. J Neurosci 6: 759-763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechsteiner M, Rogers SW (1996) PEST sequences and regulation by proteolysis. Trends Biochem Sci 21: 267-271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacher S, Montarolo PG (1991) Target-dependent structural changes in sensory neurons of Aplysia accompany long-term heterosynaptic inhibition. Neuron 6: 679-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacher S, Wu F (2002) Synapse formation in the absence of cell bodies requires protein synthesis. J Neurosci 22: 1831-1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacher S, Castellucci VF, Kandel ER (1988) cAMP evokes long-term facilitation in Aplysia sensory neurons that requires new protein synthesis. Science 240: 1667-1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacher S, Kandel ER, Montarolo P (1993) cAMP and arachidonic acid simulate long-term structural and functional changes produced by neurotransmitters in Aplysia sensory neurons. Neuron 10: 1079-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacher S, Wu F, Panyko JD, Sun ZY, Wang D (1999) Expression and branch-specific export of mRNA are regulated by synapse formation and interaction with specific postsynaptic targets. J Neurosci 19: 6338-6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JH (2001) The many dimensions of cAMP signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 13482-13484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JH, Swanson ME (1987) Dissection of tissues for characterizing nucleic acids from Aplysia: isolation of the structural gene encoding calmodulin. Methods Enzymol 139: 277-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherff CM, Carew TJ (1999) Coincident induction of long-term facilitation in Aplysia: cooperativity between cell bodies and remote synapses. Science 285: 1911-1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimahara T, Tauc L (1978) The role of cyclic AMP in the modulation of synaptic efficacy. J Physiol (Paris) 74: 515-519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuster MJ, Camardo JS, Siegelbaum SA, Kandel ER (1985) Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase closes the serotonin-sensitive K+ channels of Aplysia sensory neurones in cell-free membrane patches. Nature 313: 392-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg RA, Agard DA (1981) Turnover of regulatory subunit of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in S49 mouse lymphoma cells: regulation by catalytic subunit and analogs of cyclic AMP. J Biol Chem 256: 10731-10734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun ZY, Schacher S (1996) Tetanic stimulation and cyclic adenosine monophosphate regulate segregation of presynaptic inputs on a common postsynaptic target neuron in vitro. J Neurobiol 29: 183-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweatt JD, Kandel ER (1989) Persistent and transcriptionally-dependent increase in protein phosphorylation in long-term facilitation of Aplysia sensory neurons. Nature 339: 51-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasken K, Skalhegg BS, Tasken KA, Solberg R, Knutsen HK, Levy FO, Sandberg M, Orstavik S, Larsen T, Johansen AK, Vang T, Schrader HP, Reinton NT, Torgersen KM, Hansson V, Jahnsen T (1997) Structure, function, and regulation of human cAMP-dependent protein kinases. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res 31: 191-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SS, Buechler JA, Yonemoto W (1990) cAMP-dependent protein kinase: framework for a diverse family of regulatory enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem 59: 971-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaraghavan S, Goueli SA, Davey MP, Carr DW (1997) Protein kinase A-anchoring inhibitor peptides arrest mammalian sperm motility. J Biol Chem 272: 4747-4752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Friedman L, Schacher S (1995) Transient versus persistent functional and structural changes associated with facilitation of Aplysia sensorimotor synapses are second messenger dependent. J Neurosci 15: 7517-7527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao WD, Rusch J, Poo M, Wu CF (2000) Spontaneous acetylcholine secretion from developing growth cones of Drosophila central neurons in culture: effects of cAMP pathway mutations. J Neurosci 20: 2626-2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]