Abstract

The two main types of corticostriatal neurons are those that project only intratelencephalically (IT-type), the intrastriatal terminals of which are 0.41 μm in mean diameter, and those that send their main axon into pyramidal tract and have a collateral projection to striatum (PT-type), the intrastriatal terminals of which are 0.82 μm in mean diameter. We used three approaches to examine whether the two striatal projection neuron types (striatonigral direct pathway vs striatopallidal indirect pathway) differ in their input from IT-type and PT-type neurons. First, we retrogradely labeled one striatal projection neuron type or the other with biotinylated dextran amine (BDA)-3000 molecular weight. We found that terminals making asymmetric axospinous contact with striatonigral neurons were 0.43 μm in mean diameter, whereas those making asymmetric axospinous contact with striatopallidal neurons were 0.69 μm. Second, we preferentially immunolabeled striatonigral neurons for D1 dopamine receptors or striatopallidal neurons for D2 dopamine receptors and found that axospinous terminals had a smaller mean size (0.45 μm) on D1+ spines than on D2+ spines (0.61 μm). Finally, we combined selective BDA labeling of IT-type or PT-type terminals with immunolabeling for D1 or D2, and found that IT-type terminals were twice as common as PT-type on D1+ spines, whereas PT-type terminals were four times as common as IT-type on D2+ spines. These various results suggest that striatonigral neurons preferentially receive input from IT-type cortical neurons, whereas striatopallidal neurons receive greater input from PT-type cortical neurons. This differential cortical connectivity may further the roles of the direct and indirect pathways in promoting desired movements and suppressing unwanted movements, respectively.

Keywords: basal ganglia, cortex, corticostriatal, direct pathway, indirect pathway, striatum

Introduction

The cerebral cortex gives rise to a massive excitatory glutamatergic projection that provides the striatum with the information it needs for its role in motor control (Gerfen, 1992; Wilson, 1992). This input primarily ends as terminals that make asymmetric synaptic contact with dendritic spines of striatal projection neurons, which make up ∼95% of striatal neurons (Albin et al., 1989; Reiner and Anderson, 1990; Gerfen, 1992). In each cortical region, two types of corticostriatal neuron can be distinguished (Wilson, 1987; Cowan and Wilson, 1994; Wright et al., 1999, 2001; Reiner et al., 2003). One type, which we refer to as the pyramidal tract (PT)-type, possesses 15-20 μm perikarya found primarily in lower layer V, and their striatal projection arises as a collateral of the main axon as it traverses striatum in its course to the ipsilateral pyramidal tract (Wilson, 1987; Cowan and Wilson, 1994; Levesque et al., 1996a,b; Levesque and Parent, 1998; Reiner et al., 2003). The second type projects to basal ganglia and cortex but not outside telencephalon. These neurons, which we refer to as the intratelencephalically projecting (IT)-type, possess 12-15 μm perikarya found mainly in layer III and upper layer V (Landry et al., 1984; Wilson, 1987; Cowan and Wilson, 1994; Levesque et al., 1996a,b; Levesque and Parent, 1998; Wright et al., 1999, 2001; Reiner et al., 2003).

PT-type neurons give rise to focal clusters of fine processes and terminals (each cluster being ∼250 μm in diameter) scattered in striatum over a 1-2 mm region (Cowan and Wilson, 1994). The PT input to striatum has attracted interest because it may provide striatum with a copy of the cortical motor signal transmitted to brainstem and spinal cord (Landry et al., 1984; Levesque et al., 1996a,b). IT-type neurons project to ipsilateral striatum, as well as contralateral in many cases, and have a uniform intrastriatal arborization with sparse en passant terminals over a 1.5 mm expanse (Wilson, 1987; Cowan and Wilson, 1994; Wright et al., 1999, 2001). Previously (Reiner et al., 2003), we noted that axospinous PT-type terminals in rat striatum are typically large (0.82 μm in mean diameter) and irregular in shape, whereas axospinous IT-type terminals are characteristically small (average diameter of 0.41 μm) and regular in shape (round or oval). Wright et al. (1999, 2001) reported similar findings.

Consistent with the morphological differences between them, IT-type and PT-type corticostriatal neurons carry different signals, with PT-type neurons, but not IT-type neurons, showing movement-related activity (Turner and DeLong, 2000; Beloozerova et al., 2003). To understand better how cortical input to the striatum participates in the role of the basal ganglia in movement control, it is important to know whether the two types of corticostriatal neurons project differentially to the two main types of striatal projection neurons, those of the direct pathway and those of the indirect pathway (Albin et al., 1989; DeLong, 1990). To this end, we preferentially labeled one or the other of these two striatal projection neuron types by retrograde labeling or dopamine receptor immunolabeling and examined the size of the axospinous terminals on their dendrites. Additionally, we preferentially labeled one or the other striatal projection neuron type by dopamine receptor immunolabeling in tissue in which either PT-type or IT-type input had been selectively labeled with biotinylated dextran amine (BDA) (Reiner et al., 2003). Our findings indicate that PT-type terminals preferentially contact indirect pathway striatal neurons, whereas IT-type terminals preferentially contact direct pathway neurons. These findings suggest that PT-type corticostriatal neurons may provide indirect pathway neurons with information about ongoing movements needed for their role in suppressing unwanted movements, whereas integration of IT-type input from diverse cortical areas may underlie the role of direct pathway neurons in promoting desired movements.

Materials and Methods

Animals and experimental plan. Results from 25 adult male Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) are presented here. Efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and use as few animals as possible, and all animal use was performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Society for Neuroscience Guidelines, and University of Tennessee Health Science Center Guidelines.

In the first set of studies, we characterized the size of terminals making asymmetric axospinous contact with striatal neurons projecting to the globus pallidus (GP) [the homolog of the primate external segment of globus pallidus (GPe)], that is, indirect pathway striatal neurons (Albin et al., 1989; DeLong, 1990), compared with those making asymmetric axospinous contact with striatal neurons projecting to the substantia nigra (SN) and/or the entopeduncular nucleus (EP) [the homolog of the primate internal segment of globus pallidus (GPi)], that is, direct pathway striatal neurons (Albin et al., 1989; DeLong, 1990). In three rats, the retrograde tracer BDA3k [dextran, biotinylated, 3000 molecular weight (MW), anionic, lysine fixable; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR] was injected bilaterally into GP, and in four rats BDA3k was injected bilaterally into the SN. The injection site in representative cases of each injection type is shown (see Fig. 1). Injection of retrograde tracer into GP predominantly labels striato-GP neurons (which are enkephalinergic), as well as some striatonigral and striato-EP neurons [which characteristically contain substance P (SP)] because of their slight collateralization within the GP (Kawaguchi et al., 1990; Reiner and Anderson, 1990; Wu et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2002). Injections of retrograde tracer into substantia nigra labels direct pathway striatal neurons projecting to substantia nigra, which include neurons projecting to both EP and substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) and neurons projecting to SNr but not EP (Kawaguchi et al., 1990; Reiner and Anderson, 1990; Gerfen, 1992; Wu et al., 2000). For simplicity, we will commonly refer to both types of direct pathway striatal neurons as striatonigral, because both project to nigra in rodents. Injections of retrograde tracer into the substantia nigra do not label striato-GP neurons, because these neurons do not send a collateral to nigra (Kawaguchi et al., 1990; Wu et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2002). We analyzed by electron microscopy (EM) the size and shape of terminals making asymmetric axospinous synaptic contact on spine heads of the retrogradely labeled striato-GP and striatonigral neurons in the dorsolateral somatomotor sector of the striatum. The size of terminals was determined by measuring them at their widest diameter parallel to the postsynaptic density, and spines were identifiable by their size, continuity with dendrites, prominent postsynaptic density, and/or the presence of spine apparatus (Wilson et al., 1983). We focused our attention on dorsolateral striatum so as to minimize inclusion of striosomal neurons, which project to pars compacta of the nigra (Gerfen, 1992) and are scarce in dorsolateral striatum (Gerfen, 1992; Desban et al., 1993), among the striatonigral neurons analyzed. Thus, in the analyzed sample of retrogradely labeled neurons projecting to nigra, striato-SNr neurons are likely to have been the most abundant, because they are approximately twice as common as striato-EP neurons in rats (Kawaguchi et al., 1990; Wu et al., 2000). For GP injections, by only analyzing labeled neurons in dorsolateral striatum, we were also able to avoid any neurons incidentally labeled by passage of the syringe through medial striatum in its course to GP.

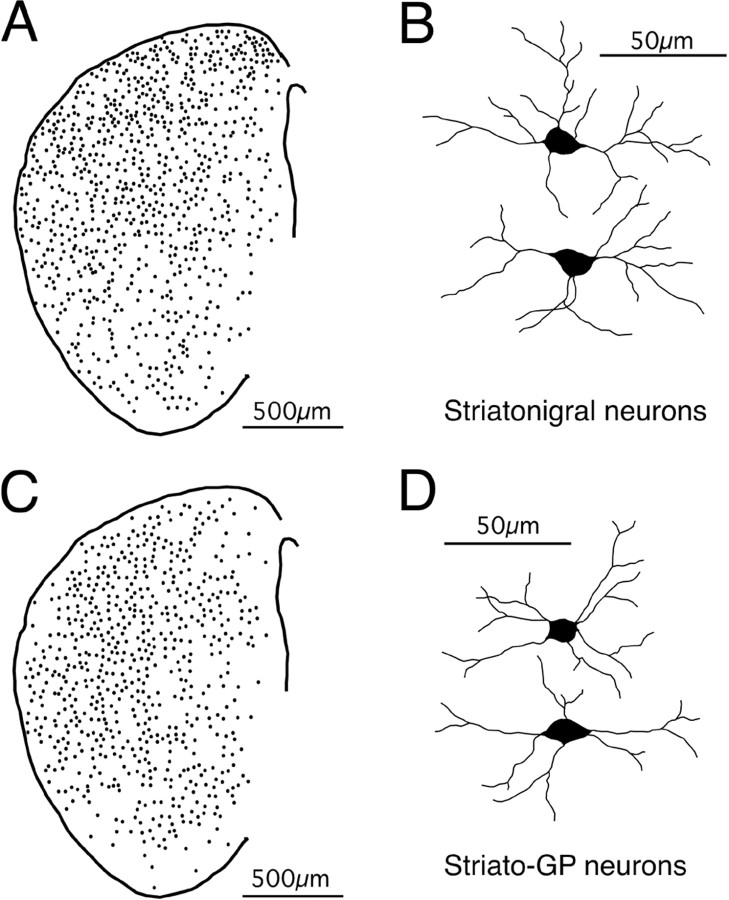

Figure 1.

Examples of BDA3k injection sites (asterisks) in the substantia nigra (A) and GP at low magnification, higher-power images showing examples of retrogradely labeled striatal neurons from such injections (C, D), and sample ultrastructural views of retrogradely labeled dendrites and spines of striatonigral (E) and striato-GP (F) neurons. Images C and D show that the perikarya and dendrites of striatonigral (C) and striato-GP (D) neurons were labeled with BDA3k, whereas images E and F show that this labeling included that of spines. BDA3k-labeled dendrites (+d) and spines (+s) are evident in E and F, and the labeled spines in each receive asymmetric synaptic contact from an unlabeled terminal (-t) containing the round vesicles characteristic of excitatory inputfrom cortex.

In our second set of studies, we sought also to characterize the size of the terminals making axospinous contact with striato-GP neurons compared with those making axospinous contact with striatonigral neurons. In this set of studies, we relied on the finding that striato-GP neurons are enriched in D2 receptors but poor in D1 receptors, whereas striatonigral neurons are enriched in D1 receptors but poor in D2 receptors (Gerfen et al., 1990; Le Moine and Bloch, 1995). We used D1 immunolabeling as an alternative way of preferentially labeling striatonigral direct pathway neurons, therefore, and D2 immunolabeling as an alternative means for preferentially labeling indirect pathway striato-GP neurons. Included among the neurons immunolabeled for D1 are those projecting primarily to the nigra, as well as those projecting both to EP and nigra (Parent et al., 1989, 1995; Kawaguchi et al., 1990; Hersch et al., 1995; Wu et al., 2000). We analyzed by EM the percentage of spines labeled for either D1 or D2 (or both) and determined the size and shape of those terminals making asymmetric axospinous synaptic contacts on immunolabeled spine heads. Terminals were again measured at their widest diameter parallel to the postsynaptic density. Note that although indirect pathway striato-GP neurons in rat characteristically contain enkephalin (ENK) and direct pathway striatonigral neurons characteristically contain SP, immunolabeling for these neuropeptides does not provide a reliable means for labeling the perikarya and dendrites of these neuron types, because they appear to rapidly ship the neuropeptides to their terminals in GP and substantia nigra, respectively, and retain little in their perikarya and dendrites (Anderson and Reiner, 1990).

Finally, to directly determine whether IT-type terminals preferentially contact either striato-GP or striatonigral neurons, nine rats received unilateral injections of BDA10k (dextran, biotinylated, 10,000 MW, anionic, lysine fixable; Molecular Probes) into motor cortex on the left side of the brain. In these cases, anterograde corticostriatal labeling in the right striatum would be limited to IT-type terminals, because PT-type corticostriatal neurons do not project to contralateral striatum, but IT-type neurons do (Cowan and Wilson, 1994; Reiner et al., 2003). Before the surgery required for the injection of the BDA10k, the animals were deeply anesthetized with 0.1 ml/100 mg of a mixture of ketamine (87 mg/kg) and xylazine (13 mg/kg). A 1 μl Hamilton microsyringe was used to inject 5% BDA10k in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4, using stereotaxic methods as described previously (Reiner et al., 2000, 2003), using coordinates from the Paxinos and Watson (1998) stereotaxic atlas of the rat brain to target the injections. To directly determine whether PT-type terminals preferentially contact either indirect pathway striato-GP or direct pathway striatonigral neurons, in seven other rats, 0.15 μl of 10% BDA3k (dextran, biotinylated, 3000 MW, anionic, lysine fixable; Molecular Probes) in 0.1 m sodium citrate-HCl, pH 3.0 (Reiner et al., 2000), was injected bilaterally, using a 1 μl Hamilton microsyringe, into the pyramidal tract at caudal pontine levels to produce selective labeling of the intrastriatal collaterals of these neurons (Reiner et al., 2003), using stereotaxic coordinates from the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1998). Alternate sections from rats with successful labeling of IT-type or PT-type terminals in right striatum were then processed for D1 or D2 immunolabeling, and all were processed for ABC visualization of the terminal labeling. As in our second line of study, D1 immunolabeling served as a way of preferentially detecting direct pathway striatonigral neurons and D2 immunolabeling as a means for preferentially detecting indirect pathway striato-GP neurons. To analyze this material, we used EM to locate BDA-labeled terminals that made asymmetric synaptic contact with spine heads in the striatum. For each such terminal, we tabulated whether the spine head contacted was immunolabeled (for D1 in D1-immunolabeled tissue or for D2 in D2-immunolabeled tissue). This information was used to determine the percentage of IT-type and PT-type terminals synaptically contacting either D1 or D2 spines. We also counted all labeled and unlabeled spines not receiving a BDA+ asymmetric synaptic input in these same fields of view. This information was used to determine the percentage of D1 and D2 spines in the fields examined that received an asymmetric synaptic contact from an IT-type or PT-type terminal. The size of the BDA+ terminals was also measured, again at the widest diameter parallel to the postsynaptic density. Synaptic contacts in all studies were identified by the presence of synaptic vesicles in the terminal and a postsynaptic density in the target spine.

Tissue fixation and processing. After 7-10 d, the rats that had been injected with BDA for ultrastructural visualization of retrogradely BDA3k-labeled striatal projection neuron spines or BDA-labeled intrastriatal corticostriatal terminals were deeply anesthetized with 0.8 ml of 35% chloral hydrate in saline and then perfused transcardially as by Reiner et al. (2003). The rats were first exsanguinated by perfusion with 30-50 ml of 6% dextran in PB, followed by 400 ml of 3.5% paraformaldehyde-0.6% glutaraldehyde-15% saturated picric acid in PB, pH 7.4. The brain of each was then removed, postfixed overnight in the same fixative without glutaraldehyde, and then sectioned at 50 μm on a vibratome. Rats without BDA injections that were to be used for studies of the size of axospinous terminals on D1- or D2-immunolabeled spines (n = 4) were similarly transcardially perfused with fixative. Tissue with retrograde BDA3k labeling of striato-GP or striatonigral neurons was next processed for visualization of the BDA. Tissue intended solely for study of the size and shape of axospinous terminals on D1-immunolabeled or D2-immunolabeled spines, on the other hand, was processed immunocytochemically with anti-D1 or anti-D2. Finally, tissue intended for simultaneous visualization of BDA labeling of corticostriatal terminals and immunolabeling of D1 and D2 dopamine receptors was processed first by the ABC procedure for BDA localization and then immunolabeled for D1 or D2. These various approaches are described in more detail in the following sections.

Visualization of dextran amines. Single-label visualization of BDA with light microscopy (LM) was used to ascertain the accuracy of injection sites, the abundance of retrogradely labeled striatonigral and striato-GP neurons in cases in which BDA had been injected into striatal target areas, or the abundance of BDA-labeled IT-type or PT-type terminals in cases in which the BDA had been injected into cortex or pons. Additional sections through the striatum from each case were processed for EM viewing. All sections were first pretreated with 1% sodium borohydride in 0.1 m PB for 30 min followed by incubation in 0.3% H2O2 solution in 0.1 m PB for 30 min. BDA was then visualized by using the ABC Elite kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) from whicha5ml volume of the ABC solution was prepared in 0.01 m PBS by adding 50 μl of avidin-DH and 50 μl of biotinylated horseradish peroxidase. Sections were incubated in this solution for 1-2 hr at room temperature or overnight at 4°C (Reiner et al., 2000). After PB rinses, the sections were immersed for 10-15 min in 0.05% diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 0.1 m PB, pH 7.2, containing 0.04% nickel-ammonium sulfate. Hydrogen peroxide was then added to the solution to a final concentration of 0.01%, and the sections were incubated in this solution for an additional 15 min. The sections were subsequently washed six times in PB. Sections to be viewed by LM were mounted onto gelatin-coated slides, dried, and then dehydrated, cleared with Pro-par (Anatech, Battle Creek, MI) or xylene, and coverslipped with Permount (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Tissue to be examined by EM was rinsed, dehydrated, and flat embedded in plastic, as described below.

Single immunolabeling for D1 and D2 dopamine receptors. Sections were first pretreated with 1% sodium borohydride in 0.1 m PB for 30 min followed by incubation in 0.3% H2O2 solution in 0.1 m PB for 30 min. Alternate sections from each rat were incubated in rat anti-D1 (product #D-187; Sigma) or rabbit anti-D2 (catalog #AB5084P Chemicon, Temecula, CA). These antibodies are selective for the 97 amino acid C-terminal fragment of human D1 and a 28 amino acid fragment within the third cytoplasmic loop (aa 284-311) of human D2 (common to short and long isoforms), respectively (Hersch et al., 1995; Wang and Pickel, 2002). To carry out conventional single-label immunohistochemistry, sections were incubated for 72 hr at 4°C in primary antiserum diluted 1:500 (D1) or 1:200 (D2) (or for some additional sections with both simultaneously) with 0.1 m Tris buffer containing 4% normal goat serum-1.5% bovine serum albumin. Sections were then rinsed and incubated in donkey anti-rat IgG or anti-rabbit IgG diluted 1:80 in 0.1 m Tris buffer, pH 7.4 (or both in cases in which the tissue had been incubated in both anti-D1 and anti-D2), followed by incubation in the appropriate rat or rabbit PAP complex diluted 1:200 in 0.1 m Tris buffer, pH 7.4 (or both in cases in which the tissue had been incubated in both anti-D1 and anti-D2), with each incubation at room temperature for 1 hr. The sections were rinsed between secondary and PAP incubations in three 5 min washes of PB. Subsequent to the PAP incubation, the sections were rinsed with three to six 10 min washes in 0.1 m PB, and a peroxidase reaction using DAB was performed. After the PB rinses, the sections were immersed for 10-15 min in 0.05% DAB (Sigma) in 0.1 m PB, pH 7.2. Hydrogen peroxide was then added to a final concentration of 0.01%, and the sections were incubated in this solution for an additional 15 min. The sections were subsequently washed six times in PB. Sections to be viewed by LM were mounted onto gelatin-coated slides, dried, and then dehydrated, cleared with Pro-par (Anatech) or xylene, and coverslipped with Permount (Fisher Scientific). Tissue to be examined by EM was rinsed, dehydrated, and flat embedded in plastic, as described below.

Combined BDA labeling of terminals and immunolabeling for D1 and D2 dopamine receptors. A two-color DAB procedure (Reiner et al., 2000, 2003) was used to double label tissue for visualization of BDA-labeled corticostriatal terminals and immunolabeled dopamine receptors, for both LM and EM viewing. The sections were first pretreated with 1% sodium borohydride in 0.1 m PB for 30 min followed by incubation in 0.3% H2O2 solution in 0.1 m PB for 30 min. BDA was then visualized by using the ABC Elite kit (Vector Laboratories), using a nickel-intensified DAB procedure as described above. These sections were subsequently washed six times in PB, and immunohistochemical labeling for D1 or D2 was performed using a brown DAB reaction to visualize the D1 or D2 immunolabeling, as described above. For each BDA-injected case used for simultaneously visualizing corticostriatal terminals and striatal dopamine receptors, some sections were prepared for LM viewing. These sections were mounted onto gelatin-coated glass slides, dried, dehydrated, cleared with Pro-par (Anatech) or xylene, and coverslipped with Permount (Fisher Scientific). Tissue to be examined at the EM level was rinsed, dehydrated, and flat embedded in plastic, as described in more detail in the following section. In the tissue prepared by such two-color DAB labeling, at the LM level, the BDA-filled corticostriatal terminals are distinctly labeled black with nickel-intensified DAB, and the dopamine receptor-bearing structures are immunolabeled with a brown DAB reaction. The LM tissue provided a means for evaluating the efficacy of the two labeling procedures in the double-labeled tissue. At the EM level, the black nickel-intensified DAB reaction product resembles the brown DAB reaction in its diffuse and flocculent appearance. Nonetheless, DAB was used to visualize both the BDA labeling and the D1 or D2 immunolabeling because of the superior sensitivity of DAB compared with other chromogens detectable at the EM level (Wouterlood et al., 1993). The similarity in appearance of the nickel-intensified and standard brown DAB reaction products at the EM level was not a hindrance to our interpretations for several reasons. First, because corticostriatal terminals and dendritic spines of striatal neurons are morphologically distinct structures, the BDA labeling of terminals could be readily distinguished from immunolabeling of spines for D1 and D2 (see Fig. 2). Second, because BDA-labeled corticostriatal terminals were intensely labeled with DAB, they could be distinguished from any rare D1 or D2 immunolabeling of excitatory axospinous synaptic terminals, because the D1- or D2-immunolabeled terminals tended to be only lightly labeled, as previously noted (Hersch et al., 1995). Moreover, D1- and D2-immunolabeled terminals were rare in our material, with only 3.1% of all asymmetric axospinous synaptic terminals labeled for D1 and 5.7% of all asymmetric axospinous synaptic terminals labeled for D2, with neither type showing an evident tendency to preferentially synapse with or avoid immunolabeled spines. Thus, any possible densely immunolabeled terminals that might have been mistaken for BDA-labeled terminals would have been infrequent and would not have biased the counts of corticostriatal synaptic targeting in favor of any particular spine type. Finally, because BDA injections into pons or cortex do not yield labeling of striatal neurons, because spiny neurons do not project to either site (Reiner et al., 1990), use of the same chromogen did not yield BDA-labeled spines that might be confused with dopamine receptor-immunolabeled spines.

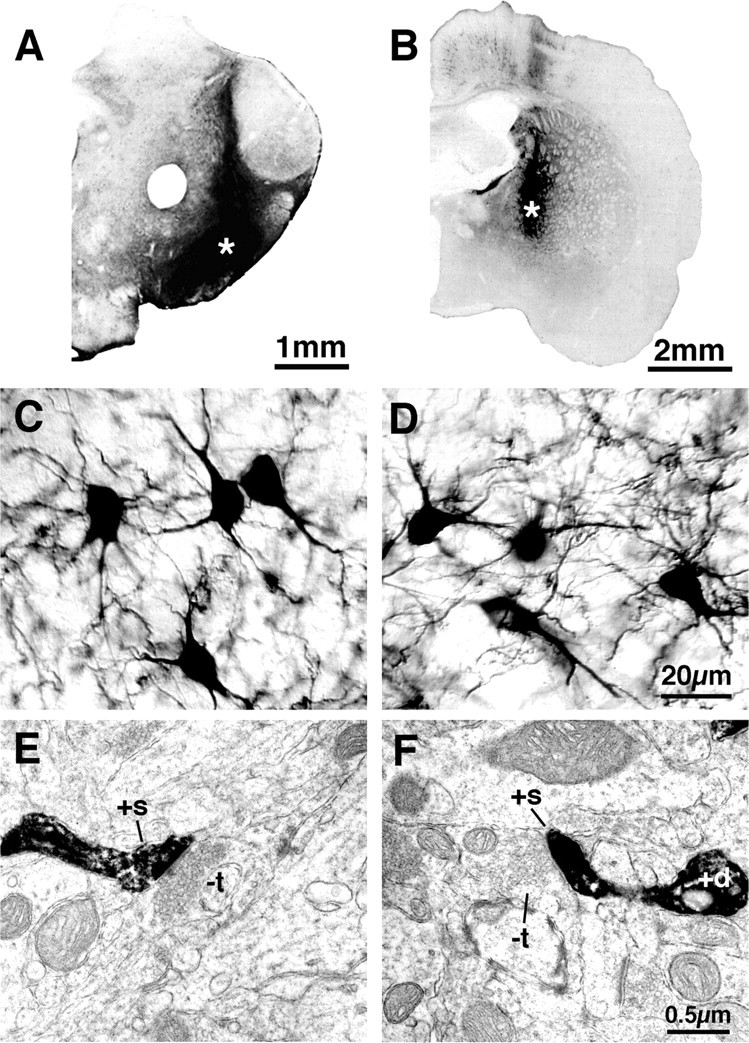

Figure 2.

Electron microscopic images of immunolabeling of rat striatum for D1 from tissue in which IT-type terminals were labeled with BDA10k (A) and for D2 from tissue in which PT-type terminals were labeled with BDA3k (B), showing representative examples (arrows) of D1-immunolabeled (A) and D2-immunolabeled (B) asymmetric axospinous synaptic terminals, with the recipient spines indicated by asterisks. The immunolabeled terminals were far less intensely labeled than BDA-labeled terminals, an example of which is indicated in A (arrowhead).

Preparation of tissue for EM. After BDA visualization as described above (in the case of BDA-labeled tissue) or immunolabeling for D1 or D2 as described above (in the case of tissue used for determination of terminal size on D1- and D2-labeled spines or tissue with concurrent dopamine receptor immunolabeling of spines and BDA labeling of corticostriatal terminals), the sections were rinsed in 0.1 m sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2, postfixed for 1 hr in 2% osmium tetroxide (OsO4) in 0.1 m sodium cacodylate buffer, dehydrated in a graded series of ethyl alcohols, impregnated with 1% uranyl acetate in 100% alcohol, and flat embedded in Spurr's resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA). For the flat embedding, the sections were mounted on microslides pretreated with liquid releasing factor (Electron Microscopy Sciences). The Spurr's resin-embedded sections were examined light microscopically for the presence of BDA-labeled axons and terminals in striatum. Pieces of embedded tissue were then cut from the striatum and glued to carrier blocks, and ultrathin sections were cut from these specimens with a Reichert ultramicrotome. The sections were mounted on mesh grids, stained with 0.4% lead citrate and 4.0% uranyl acetate using an LKB-Wallac (Gaithersburg, MD) Ultrastainer, and finally viewed and photographed with a Jeol (Peabody, MA) 1200 electron microscope. One or more series from each case used for ultrastructural analysis were also routinely processed for LM visualization of BDA labeling. Analysis and quantification was performed using the photographs of the EM labeling. LM and EM images were scanned and imported into Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) to prepare the illustrations presented here.

Results

Size of terminals making asymmetric synaptic contact with spines of retrogradely labeled striatonigral versus striato-GP neurons

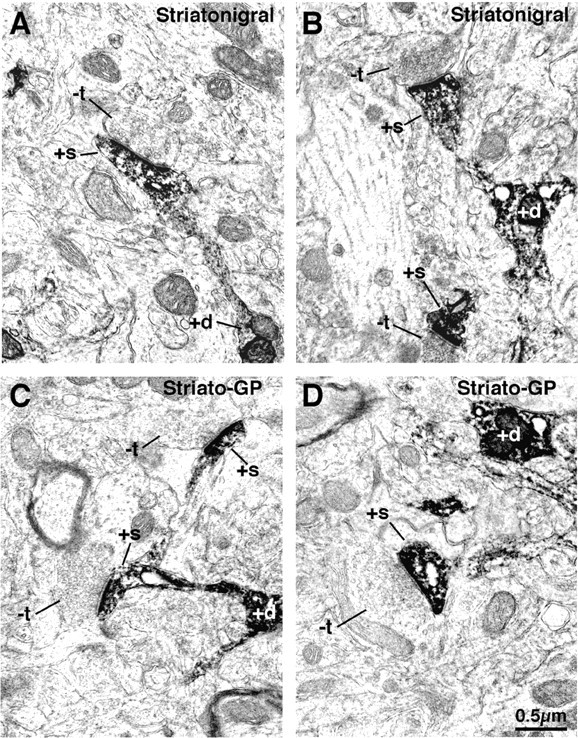

In three rats, numerous neurons were labeled in the ipsilateral striatum after accurate BDA3k injection into the substantia nigra on one side of the brain (Figs. 1A,C, 2A,B). In one additional rat, numerous neurons were labeled on each side after accurate BDA3k injection into each nigra. Similarly, in one rat, many neurons were labeled in the ipsilateral striatum after accurate BDA3k injection in the GP, on one side of the brain, and in two additional rats, numerous neurons were labeled on each side after accurate BDA3k injection into each GP (Figs. 1B,D, 3C,D). Camera lucida drawings of retrogradely labeled striatonigral and striato-GP neurons indicated that the perikaryal size of the two neuron types and the dendritic labeling of the two neuron types was indistinguishable, typically including evident labeling of tertiary and quaternary branches (Fig. 3B,D). Electron microscopic analysis revealed labeling of dendritic spines of both neuron types as well (Fig. 4). Statistical analysis (by t tests) indicated no significant difference in the number and length of primary or higher-order dendritic branches between the two types of neurons or in perikaryal size. Analysis at the EM level revealed that asymmetric axospinous synaptic terminals on BDA-labeled striatonigral neuron spines were characteristically small (average of 0.43 ± 0.003 μm in diameter for 309 such terminals) and regular in shape (see Table 2, Fig. 4A,B). In contrast, asymmetric axospinous synaptic terminals on BDA3k-labeled striato-GP neuron spines were characteristically larger (average of 0.69 ± 0.017 μm in diameter for 342 such terminals) and more commonly irregular in shape (Table 1, Fig. 4C,D). Additionally, the synaptic zone in many cases (as judged by the postsynaptic density) tended to be lengthy and discontinuous. Thus, retrogradely labeled striatonigral and striato-GP neurons commonly differed in the size and shape of the terminals making asymmetric synaptic contact with their spines, with the terminal size difference being highly significant (Table 1, Fig. 5). Given that the dendrites of the two neuron types were labeled to a similar extent, it seems unlikely that the difference in terminal size and shape stemmed from a bias toward sampling different parts of the dendritic tree of the two neuron types.

Figure 3.

Camera lucida drawings showing the comparable distributions of BDA3k retrogradely labeled striatonigral (A) and striato-GP (C) neurons and the similar extent of labeling for each neuron type (B, D) in representative cases for each.

Figure 4.

Electron microscopic images of dendrite (+d) and spine (+s) labeling of striatonigral (A, B) and striato-GP (C, D) neurons that had been retrogradely labeled with BDA3k. Note that the labeled striatonigral (A, B) spines receive asymmetric synaptic contact from smaller unlabeled terminals (-t) than do the striato-GP neuron spines (C, D).

Table 2.

Percentage of BDA-labeled IT-type versus PT-type terminals making axospinous synaptic contact with striatonigral versus striato-GP neurons, as identified by dopamine receptor immunolabeling

|

Type of spine targeted by BDA + synaptic terminal |

Percentage of BDA + IT-type terminal synapsing on given spine type |

Percentage of BDA + PT-type terminal synapsing on given spine type |

Significance of IT-type versus PT-type frequency difference by t test |

Mean ± SEM size of BDA + IT-type axospinous synaptic terminal |

Mean ± SEM size of BDA + PT-type axospinous synaptic terminal |

Significance of IT-type versus PT-type size difference by t test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 + (striatonigral) | 50.9% (based on 75 BDA + IT-type synaptic terminals on D1 + spines in six striata) | 21.3% (based on 39 BDA + PT-type synaptic terminals on D1 + spines in seven striata) | IT versus PT frequency on D1 + spines significantly different at p = 0.008 | 0.40 ± 0.016 μm (n = 6 striata) | 0.68 ± 0.077 μm (n = 5 striata) | IT versus PT size significantly different on D1 + spines at p = 0.002 |

| D2 + (striato-GP) | 12.6% (based on 29 BDA + IT-type synaptic terminals on D2 + spines in five striata) | 50.5% (based on 68 BDA + PT-type synaptic terminals on D2 + spines in five striata) | IT versus PT frequency on D2 + spines significantly different at p = 0.0003 | 0.43 ± 0.057 μm (n = 3 striata) | 0.72 ± 0.041 μm (n = 5 striata) | IT versus PT size significantly different on D2 + spines at p = 0.003 |

| Significance of D1 versus D2 difference by t test |

D1 versus D2 frequency of IT synaptic input significantly different at p = 0.002 |

D1 versus D2 frequency of PT synaptic input significantly different at p = 0.005 |

|

IT-type size not significantly different; p = 0.391 |

PT-type size not significantly different; p = 0.578 |

|

Table 1.

Comparison of axospinous synaptic terminal size on striatonigral and striato-GP neurons identified by retrograde labeling or dopamine receptor immunolabeling

|

Approach used to label striatal projection neuron type |

Mean ± SEM size of axospinous synaptic terminals on striatonigral neurons |

Mean ± SEM size of axospinous synaptic terminals on striato-GP neurons |

Significance by t test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retrograde BDA3k labeling from nigra (striatonigral neurons) or GP (striato-GP neurons) | 0.43 ± 0.003 μm (n = 309 terminals in five striata) | 0.69 ± 0.017 μm (n = 342 terminals in five striata) | Significant at p = 0.0000005 |

| Immunolabeled for D1 (striatonigral neurons) or D2 (striato-GP neurons) | 0.45 ± 0.02 μm (n = 867 terminals in four striata) | 0.61 ± 0.05 μm (n = 519 terminals in four striata) | Significant at p = 0.02 |

| Significance of retrograde labeling versus immunolabeling difference in terminal size by t test |

Terminal size for striatonigral neurons retrogradely labeled versus D1 immunolabeled not significantly different at p = 0.193 |

Terminal size for striato-GP neurons retrogradely labeled versus D2 immunolabeled not significantly different at p = 0.154 |

|

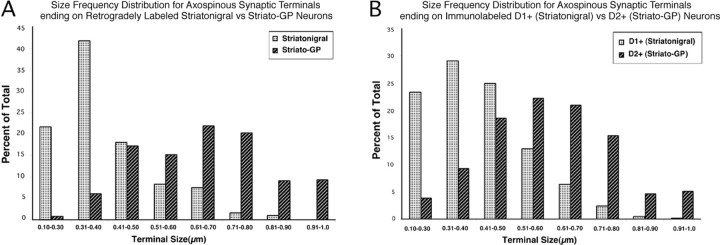

Figure 5.

Histograms comparing the size frequency distribution of asymmetric synaptic terminals on striatonigral spines to the size frequency distribution of asymmetric synaptic terminals on striato-GP spines, with spine types based on either retrogradely labeling with BDA3k (A) or immunolabeling for D1 or D2 dopamine receptors (B). In both A and B, the frequency for each spine type is expressed as a percentage of the total number of asymmetric axospinous contacts counted for that spine type (309 BDA3k+ striatonigral spines, 342 BDA3k+ striato-GP spines, 867 D1+ striatonigral spines, and 519 D2+ striato-GP spines). Note that the size range is lower and peak frequency less for terminals on labeled striatonigral neuron spines than on striato-GP neuron spines by either the retrograde labeling or immunolabeling method of identifying such spines. As shown in Table 2, the mean size of the asymmetric axospinous synaptic terminals on striatonigral neurons is also significantly less than on striato-GP neurons.

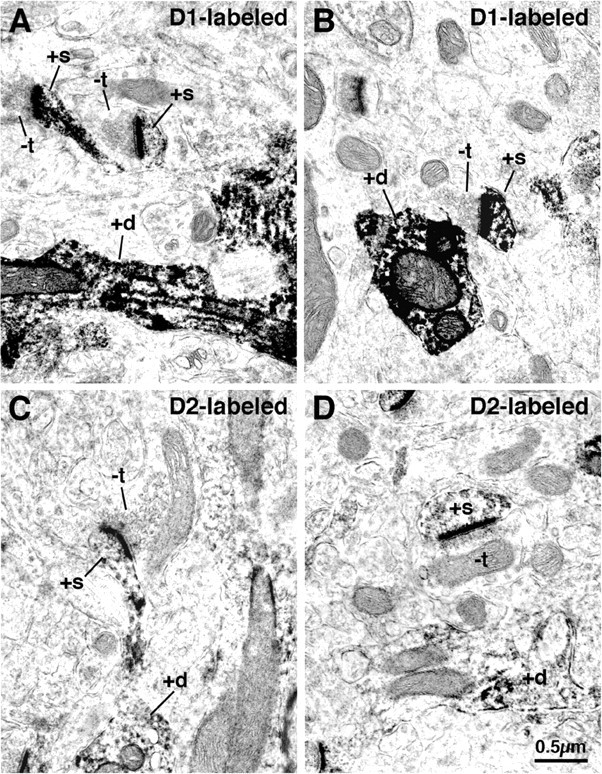

Size of terminals making asymmetric synaptic contact with D1-versus D2-immunolabeled spines

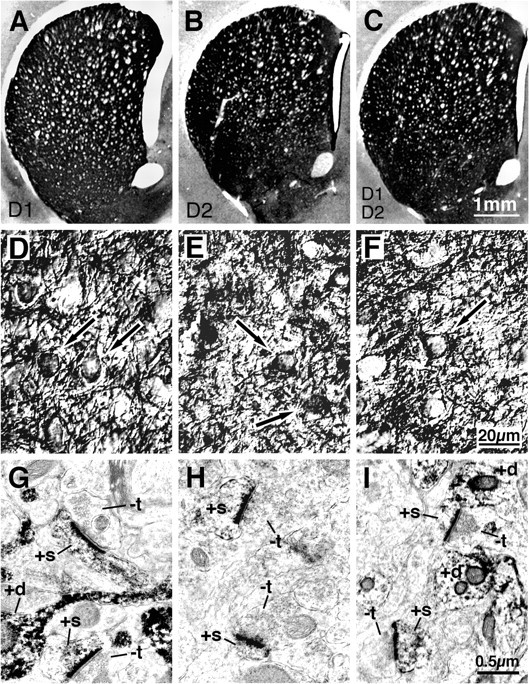

Immunostaining for D1, D2, and D1 plus D2 was intense in striatum, with little labeling in cortex (Fig. 6A-C). High-magnification LM viewing revealed the immunostaining to be localized to striatal neuronal perikarya and dendrites, primarily along the cell membrane inner surfaces (Fig. 6D-F). EM additionally revealed labeling of spines (Figs. 6G-I). Counts of labeled spines at the EM level in random fields showed that the mean percentage (±SEM) of spines labeled for D1 was 47.2 ± 2.4%, for D2 was 46.2 ± 1.6%, and for D1 plus D2 was 89.4 ± 0.7% (based on 1605 spines). Similar results have been reported previously by Hersch et al. (1995) for the relative frequencies of striatal spine immunolabeling for D1, D2, and D1 plus D2. The finding that the sum of the D1-immunolabeled and D2-immunolabeled spine frequencies only slightly exceeds that in the tissue simultaneously labeled for D1 plus D2 suggests D1 and D2 to be primarily localized to the spines of separate neuron types in our tissue. Studies by others suggest these separate neuron types to be striatonigral (D1) versus striato-GP (D2) projection neurons (Gerfen et al., 1990; Gerfen, 1992; Le Moine and Bloch, 1995). The mean size of terminals making asymmetric synaptic contact with D1-immunolabeled spines (0.45 ± 0.02 μm, based on 867 spines in four rats) was significantly smaller than the mean size of terminals making asymmetric synaptic contact with D2-immunolabeled spines (0.61 ± 0.05 μm, based on 519 spines in the same four rats) (Table 1, Figs. 5, 7).

Figure 6.

LM and EM images of immunolabeling of rat striatum for D1 (A,D,G), D2 (B,E,H), or D1 plus D2 (C,F,I) dopamine receptors. The immunostaining for D1, D2, and D1 plus D2 was intense in striatum, with little in cortex, as revealed by the low-power LM images (A-C). High magnification LM viewing revealed the immunostaining to be localized to striatal neuron perikarya (arrows) and dendrites (+d) (D-F). EM viewing additionally revealed labeling of spines (+s) receiving asymmetric synaptic contacts from terminals containing the round vesicles characteristic of the excitatory input from the cerebral cortex (G-I). -t, Unlabeled terminals.

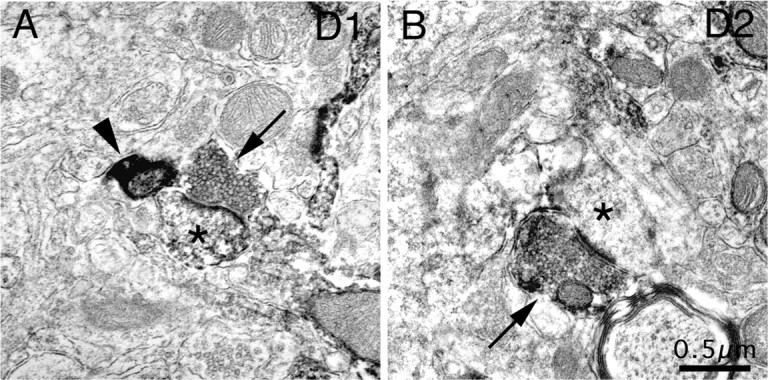

Figure 7.

D1-immunolabeled spines (A, B) and D2-immunolabeled spines (C, D) in rat striatum at the EM level. Note that the D1-immunolabeled spines (+s), which presumptively primarily belong to striatonigral neurons, receive asymmetric synaptic contact from smaller unlabeled terminals (-t) than do the D2-immunolabeled spines, which presumptively primarily belong to striato-GP neurons. Labeled dendrites (+d) are also evident in the fields of view shown.

Targetting of BDA-labeled IT-type and PT-type terminals to D1-versus D2-immunolabeled spines

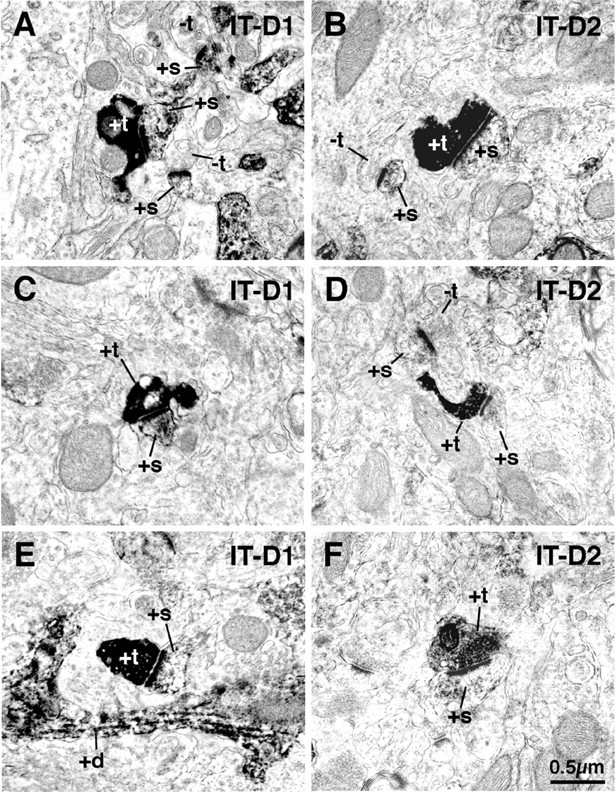

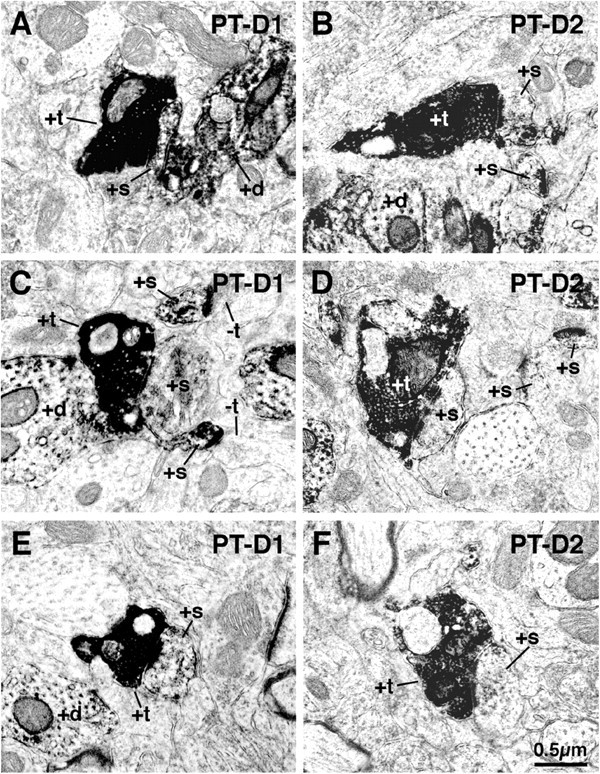

Counts of labeled spines at the EM level in the fields used for the analysis of BDA-labeled terminals on dopamine receptor immunolabeled spines showed that the mean percentage (±SEM) of spines labeled for D1 in the D1-immunolabeled tissue was 50.7 ± 1.7% (based on 1023 spines), and for D2 in the D2-immunolabeled tissue was 47.1 ± 4.4% (based on 799 spines). Thus, the percentage of spines labeled for D1 or D2 in the double-labeled material closely resembled that in the immunolabeling-alone material, suggesting that combining BDA labeling and immunolabeling did not significantly alter the dopamine receptor immunolabeling of spines. Double labeling for IT-type corticostriatal terminals and the spines of direct pathway striatonigral neurons (via D1 immunolabeling) or of indirect pathway striato-GP neurons (via D2 immunolabeling) showed that of all axospinous asymmetric IT-type synaptic terminals labeled with BDA in tissue immunolabeled for D1, a mean 50.9% of the IT-type terminals (for six striata in six rats) contacted D1 spines (Table 2, Fig. 8). In contrast, of all axospinous asymmetric IT-type synaptic terminals labeled with BDA in tissue immunolabeled for D2, only an average of 12.6% (for seven striata in six rats) contacted D2 spines. Thus, IT-type terminals labeled with BDA contacted D1 spines four times more commonly than they contacted D2 spines (significantly different at the 0.002 level by t test). Double labeling for PT-type corticostriatal terminals and the spines of direct pathway striatonigral neurons (via D1 immunolabeling) or of indirect pathway striato-GP neurons (via D2 immunolabeling) showed a different trend; of all axospinous asymmetric PT-type synaptic terminals labeled with BDA in tissue immunolabeled for D1, only a mean of 21.3% of PT-type terminals (in five striata in five rats) contacted D1 spines, whereas of all axospinous asymmetric PT-type synaptic terminals labeled with BDA in tissue immunolabeled for D2, a mean of 50.5% (in five striata in four rats) contacted D2 spines (Table 2, Fig. 9). This difference for PT-type terminals was significantly at the 0.005 level by t test. Thus, IT-type terminals preferentially contact D1 spines, whereas PT-type terminals preferentially contact D2 spines. The data also show that IT-type terminals (Table 2) are significantly smaller (0.40-0.43 μm) than PT-type terminals (Table 2) on both D1-immunolabeled and D2-immunolabeled spines (0.68-0.72 μm), as would be expected from our previous findings on the mean size of IT-type and PT-type terminals on striatal spines (Reiner et al., 2003).

Figure 8.

EM images showing double labeling for BDA10k-labeled IT-type corticostriatal terminals and D1-immunolabeled (+s) (striatonigral) spines in rat striatum (A, C, E) and for BDA10k-labeled IT-type corticostriatal terminals and D2-immunolabeled (striato-GP) spines (B, D, F). These images show that IT-type terminals make asymmetric synaptic contact with D1-immunolabeled spines, as well as D2-immunolabeled spines. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, however, the IT-type terminals far more commonly contact D1 than D2 spines. +d, Labeled dendrites; -t, unlabeled terminals; +t, labeled terminals.

Figure 9.

EM images showing double labeling for BDA3k-labeled PT-type corticostriatal terminals and D1-immunolabeled (striatonigral) spines (+s) in rat striatum (A, C, E) and for BDA3k-labeled PT-type corticostriatal terminals and D2-immunolabeled (striato-GP) spines (B, D, F). These images show that PT-type terminals make asymmetric synaptic contact with both D1-immunolabeled spines, as well as D2-immunolabeled spines. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, however, the PT-type terminals far more commonly contact D2 than D1 spines. +t, Labeled terminals; -t, unlabeled terminals; +d, labeled dendrites.

The preference of IT-type terminals for D1 spines and PT-type terminals for D2 spines is also evident when the data are used to calculate the percentage of spines of a given type that were observed to receive asymmetric IT-type or PT-type synaptic input (Table 3). For example, in the fields examined (i.e., all fields containing a labeled IT-type corticostriatal terminal making asymmetric synaptic contact with a spine head), a mean of 23.7% of D1+ spines (in six striata in six rats) received IT input, whereas significantly fewer D2+ spines (a mean of only 10.2% in five striata in five rats) received IT-type input. For PT-type terminals, a significant D2+ spine preference was evident. In the fields examined (i.e., all fields containing a labeled PT-type corticostriatal terminal making asymmetric synaptic contact with a spine head), a mean of 40.1% of D2+ spines received PT-type synaptic input (in five striata in four rats), whereas a mean of only 12.4% of D1+ spines (in seven striata in six rats) received PT input. The corticostriatal terminal difference for D2 spines was significant at the p = 0.0003 level, whereas the difference for D1 spines was nearly significant (p = 0.06). Thus, regardless of how the results of this study combining anterograde labeling of terminal types with immunolabeling of spines for D1 or D2 are examined, the findings consistently indicate that IT-type terminals preferentially contact the spines of direct pathway striatonigral neurons (preferentially possessing D1), and PT-type terminals preferentially target the spines of indirect pathway striato-GP neurons (preferentially possessing D2).

Table 3.

Percentage of striatonigral versus striato-GP neuron spines, as identified by dopamine receptor immunolabeling, receiving axospinous synaptic contact from BDA-labeled IT-type versus PT-type terminals

|

Type of spine targeted by BDA + synaptic terminal |

Percentage of spines with IT-type axospinous synaptic terminal |

Percentage of spines with PT-type axospinous synaptic terminal |

Significance of IT versus PT frequency difference on spine type by t test |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1 + (striatonigral) | 23.7% (based on 75 BDA + IT-type synaptic terminals on D1 + spines in six striata) | 12.4% (based on 39 BDA + PT-type synaptic terminals on D1 + spines in seven striata) | IT versus PT frequency on D1 + spines not significantly different; p = 0.06 |

| D2 + (striato-GP) | 10.2% (based on 29 BDA + IT-type synaptic terminals on D2 + spines in five striata) | 40.1% (based on 68 BDA + PT-type synaptic terminals on D2 + spines in five striata) | IT versus PT frequency on D2 + spines significantly different at p = 0.0003 |

| Significance of D1 versus D2 difference in corticostriatal input type by t test |

Frequency of IT input significantly different on D1 versus D2 spines at p = 0.05 |

Frequency of PT input significantly different on D1 versus D2 spines at p = 0.0003 |

|

Discussion

Our three lines of study in rats suggest that IT input preferentially ends on direct pathway striatonigral neurons, whereas PT input preferentially ends on indirect pathway striato-GP neurons. This conclusion is consistent with previous evidence that although all striatal neurons respond to glutamatergic cortical input, the input to indirect pathway striatal neurons somehow differs from that to direct pathway neurons (Uhl et al., 1988; Zemanick et al., 1991; Berretta et al., 1997; Parthasarathy and Graybiel 1997).

Main conclusions and technical considerations

Selective retrograde labeling of striatonigral and striato-GP neurons

In our first line of study, we found the mean size of terminals making axospinous asymmetric synaptic contact with spines of striatal neurons retrogradely labeled with BDA3k from the substantia nigra (0.43 μm) closely matched that previously reported by us for IT-type terminals (0.41 μm) (Reiner et al., 2003). The uniformly small size of asymmetric axospinous terminals on neurons retrogradely labeled from nigra suggests that both striato-SNr (the predominant type projecting to nigra) and striato-EP neurons preferentially receive IT-type input. Because asymmetric axospinous thalamostriatal terminals are commonly closer in size to IT-type than PT-type terminals (Sadikot et al., 1992; Lei et al., 2004), our study suggests direct pathway neurons may receive thalamostriatal input as well. Sidibe and Smith (1996), in fact, reported that thalamostriatal terminals in monkey preferentially contact striato-GPi direct pathway rather than striato-GPe indirect pathway neurons.

Only one type of striatal neuron projects exclusively to GP, and these contain ENK (Parent et al., 1989, 1995; Kawaguchi et al., 1990; Reiner and Anderson, 1990; Wu et al., 2000). Although striatal neurons that project to nigra or EP, which commonly contain SP, have slight collateralization to GP (Kawaguchi et al., 1990; Wu et al., 2000), the sparseness of these collaterals makes it likely that true striato-GP neurons predominated among our striatal neurons retrogradely labeled from GP. This interpretation is consistent with our finding by single-cell reverse transcription (RT)-PCR that 70% of striatal neurons retrogradely labeled from GP in rat contain ENK but not SP (Wang et al., 2002). Interestingly, the mean size of axospinous synaptic terminals on striatal neurons labeled from GP (0.69 μm) is as would be expected if 70% of labeled neurons were striato-GP neurons receiving 0.82 μm PT-type terminals and 30% were striato-EP-SNr neurons receiving 0.41 μm IT-type terminals [(0.82 μm × 70%) + (0.41 μm × 30%) = 0.69 μm]. Thus, our studies of retrogradely labeled striatal projection neurons suggest that PT-type terminals end preferentially on striato-GP neurons, and IT-type preferentially on striato-EP-SNr neurons.

Selective detection of striatonigral neurons by D1 immunolabeling and striato-GP neurons by D2 immunolabeling

The localization of D1 and D2 receptors to striatal projection neurons has been controversial, with immunolabeling and in situ hybridization histochemistry (ISHH) favoring segregation of D1 to direct pathway neurons and D2 to indirect pathway neurons (Gerfen et al., 1990; Gerfen, 1992; Hersch et al., 1995; Le Moine and Bloch, 1995), and physiological, single-cell RT-PCR and some ISHH studies providing evidence for significant D1-D2 colocalization (Lester et al., 1993; Surmeier et al., 1993, 1996; Aizman et al., 2000). Although functionally significant D1-D2 colocalization may occur in some striatal projection neurons, our EM immunolabeling indicates that the D1-immunolabeled and D2-immunolabeled spines in our sample primarily belonged to different striatal projection neuron populations, with under 10% of D1 spines possessing D2 and under 10% of D2 spines possessing D1. In this light, our findings that the mean size of terminals making asymmetric synaptic contact with D1 spines (0.45 μm) was similar to that of IT-type terminals (0.41 μm), whereas the mean size of terminals making asymmetric synaptic contact with D2 spines (0.61 μm) was more similar to that of PT-type terminals (0.82 μm) suggests, at the very least, that striato-EP-SNr neurons receive predominantly IT-type terminals, and striato-GP neurons receive many more PT-type terminals than do striato-EP-SNr neurons. The disparity between mean terminal size on D2+ spines and PT-type terminal size may not be as great as appears, because the mean size of PT-type terminals was less (0.70 μm) in the current study combining spine immunolabeling with BDA terminal labeling than in our previous study of PT labeling alone (0.82 μm) (Reiner et al., 2003). Using the measured mean size of PT-type terminals in the current D1- and D2-immunolabeled tissue, it can be algebraically deduced from the size of the terminals on D1-immunolabeled spines that only 12.5% of the D1 spines immunolabeled in our second line of study received PT-type input. This slight PT input to D1 spines may reflect the existence of PT-recipient D1+ striato-GP neurons (possibly also possessing D2), which would be consistent with reports that 10-20% of striatal enkephalinergic neurons possess D1 (Surmeier et al., 1996; Waszczak et al., 1998). The minor PT input to D1 spines could also mean that some D1+ striatonigral neurons possess PT-recipient spines, which is consistent with our findings from our third line of study combining D1 spine immunolabeling with BDA-labeling of PT-type terminals.

Similarly, we algebraically deduced that only 32% of our D2-immunolabeled spines received terminals in the size range of IT-type or thalamic. This minor IT or thalamic input to D2 spines may stem from spines belonging to D2+ striatonigral-EP neurons (possibly also possessing D1), which would be consistent with reports that ∼20% of striatonigral neurons possess D2 (Gerfen et al., 1990; Surmeier et al., 1993). It is also possible that the minority axospinous input to D2 spines from small terminals reflects D2+ striato-GP neurons receiving IT input, which is consistent with our finding combining D2 immunolabeling with BDA-labeling of IT-type terminals that at least 10.2% of D2 spines receive IT-type input. The predominance of PT-type terminals relative to IT-type on D2+ spines revealed in our third line of study (Table 3), however, suggests that many of the small terminals on D2+ spines may arise from thalamus. In any event, our findings on the size of terminals on D2-immunolabeled spines in our second line of study indicate that PT-type terminals predominate on striato-GP neurons.

Selective BDA labeling of IT-type and PT-type terminals

Because not all IT-type neurons of motor cortex project to contralateral striatum (Wilson, 1987; Cowan and Wilson, 1994; Reiner et al., 2003), the synaptic targets of the contralateral IT-type terminals revealed in our third line of study may not be representative of all IT-type terminals. Two considerations argue against this possibility. First, although contralateral cortical projections differ from ipsilateral in their topographic organization and targeting of dendrites (Flaherty and Graybiel, 1993; Hersch et al., 1995), there is no evidence they differ in size, physiology, or the cell type targeted (Wilson, 1987; Cowan and Wilson, 1994; Wright et al., 1999, 2001). Second, the conclusion from our study of contralateral BDA10k-labeled IT-type terminals that IT-type terminals prefer striatonigral (i.e., D1+) spines is consistent with our studies of terminal size on retrogradely labeled or D1-immunolabeled striatonigral spines. To selectively label PT-type terminals, we relied on the ability of BDA3k to label the intrastriatal collaterals of retrogradely labeled PT-type neurons (Reiner et al., 2000) and on the fact that IT-type neurons do not project extratelencephalically (Wilson, 1987; Cowan and Wilson, 1994). This approach, however, does not allow us to be sure of the cortical region giving rise to any particular BDA3k-labeled PT-type terminal. Although we overcame this limitation to some extent by examining only dorsolateral striatum, which receives its major input from somatomotor-somatosensory cortex (Alloway et al., 1998; Hoffer and Alloway, 2001), we do not know whether PT-type neurons of somatosensory and motor cortex equally prefer striato-GP neurons.

Combining BDA labeling of terminals with immunolabeling of spines

The double-labeling approach of our third line of study showed that IT-type terminals commonly contact D1 spines, whereas PT-type terminals commonly contact D2 spines. We also found that a higher percentage of D1 spines received IT terminals than received PT, whereas a higher percentage of D2 spines received PT than IT. We presume that not all D1-immunolabeled or D2-immunolabeled spines received BDA-labeled terminals because not all corticostriatal terminals of a given type were BDA-labeled (notably IT-type terminals of ipsilateral origin were unlabeled), and some spines may have received thalamic input. One potential problem is that combining BDA labeling and immunolabeling could have decreased the frequency of D1- and D2-immunolabeled spines from that in our study involving dopamine receptor immunolabeling alone, so as to lead to underrepresentation of one type of spine or the other. Our counts of D1- or D2-immunolabeled spines in the double-labeled tissue revealed, however, that this was not the case. Finally, Hersch et al. (1995) reported findings similar to ours for the percentage of contralateral BDA-labeled terminals (IT-type) arising from primary motor cortex (M1) that synapse on D1-immunolabeled spines, 47% in their study compared with 50.9% in ours. They, however, reported a much higher percentage of contralateral BDA-labeled terminals from M1 to synapse on D2-immunolabeled spines than we did, 52% versus 12.6%. The basis of this disparity is uncertain, but may lie in the different anti-D2 used, which could have differed in their specificities in some manner not reflected in the frequency of spine labeling. Nonetheless, our conclusions about the target preference of IT-type and PT-type terminals from our double-label study are consistent with those of our first two lines of study.

Functional implications

Striato-EP-SNr neurons are thought to promote desired movement, and striato-GP neurons to inhibit unwanted movement (Albin et al., 1989; DeLong, 1990). Because PT-type input conveys a copy of the cortical motor signal (Miller, 1975; Oka and Jinnai, 1978; Landry et al., 1984; Mink, 1996), it may enable striato-GP neurons to inhibit behaviors that might otherwise conflict with movements initiated by the motor signal to brainstem. This may explain why striatal neurons that fire in association with movement commonly do not fire before movement onset (Jaeger et al., 1995; Mink, 1996). The larger size of PT-type terminals than IT-type and their tendency to be apposed to perforated postsynaptic densities may augment their synaptic efficacy (Geinisman, 1993; Sulzer and Pothos, 2000). This might explain why striato-GP neurons appear more responsive to cortical input than striato-EP-SNr neurons (Uhl et al., 1988; Parthasarathy and Graybiel 1997) and more avidly take up and anterogradely transmit the cortically injected H129 strain of herpes simplex virus (Zemanick et al., 1991). Perforated postsynaptic densities also indicate sites of synaptic potentiation (Geinisman, 1993; Geinisman et al., 1996; Sulzer and Pothos, 2000; Topni et al., 2001). Because the basal ganglia is involved in motor learning (Calabresi et al., 1992; Marsden and Obeso, 1994; Gabrieli, 1995; Graybiel and Kimura, 1995), the PT input to striato-GP neurons may participate in learned suppression of conflicting movements. Finally, the small size of the IT-type terminals and the diffuse nature of the IT projection to striatum may require synchrony of firing from diverse cortical areas for IT input to activate striato-EP-SNr neurons (Wilson, 1992). This is consistent with the presumed role of direct pathway neurons in promoting movement based on integration of diverse cortical input and with evidence for convergent projections from related cortical areas to individual striatal domains (Flaherty and Graybiel, 1991; Brown et al., 1998; Hoffer and Alloway, 2001).

Footnotes

This research was supported by NS-19620 and NS-28721 (A.R.) and The University of Tennessee Center for Excellence in Neuroscience (Y.J.). We thank Drs. C. Meade, Y.P. Deng, and Z. Sun for their helpful comments during the course of this study, and we are grateful to J.C. Lopez, S.L. Cuthbertson, Kathy Troughton, Raven Babcock, Amanda Valencia, Toya Kimble, and Yunping Deng for technical assistance and advice.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Anton Reiner, Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, The University of Tennessee Health Science Center, 855 Monroe Avenue, Memphis, TN 38163. E-mail: areiner@utmem.edu.

Y. Jiao's present address: Department of Developmental Neurobiology, Saint Jude Children's Research Hospital, 332 North Lauderdale, Memphis, TN 38105.

Copyright © 2004 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/04/248289-11$15.00/0

References

- Aizman O, Brismar H, Uhlen P, Zettergren E, Levey AI, Forssberg H, Greengard P, Asperia A (2000) Anatomical and physiological evidence for D1 and D2 dopamine receptor colocalization in neostriatal neurons. Nat Neurosci 3: 226-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB (1989) The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci 12: 366-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloway KD, Mutic JJ, Hoover JE (1998) Divergent corticostriatal projections from a single cortical column in the somatosensory cortex of rats. Brain Res 788: 341-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KD, Reiner A (1990) Extensive co-occurrence of substance P and dynorphin in striatal projection neurons: an evolutionarily conserved feature of basal ganglia organization. J Comp Neurol 295: 339-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beloozerova IN, Sirota MG, Swadlow HA, Orlovsky GN, Popova LB, Deliagina TG (2003) Activity of different classes of neurons of the motor cortex during postural corrections. J Neurosci 23: 7844-7853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berretta S, Parthasarathy HB, Graybiel AM (1997) Local release of GABAergic inhibition in the motor cortex induces immediate-early gene expression in indirect pathway neurons of the striatum. J Neurosci 17: 4752-4763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LL, Smith DM, Goldbloom LM (1998) Organizing principles of cortical integration in the rat neostriatum: corticostriate map of the body surface is an ordered lattice of curved laminae and radial points. J Comp Neurol 392: 468-488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, Pisani A, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G (1992) Long-term potentiation in the striatum is unmasked by removing the voltage-dependent magnesium block of NMDA receptor channels. Eur J Neurosci 4: 929-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan RH, Wilson CJ (1994) Spontaneous firing patterns and axonal projections of single corticostriatal neurons in the rat medial agranular cortex. J Neurophysiol 71: 17-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong MR (1990) Primate models of movement disorders of basal ganglia origin. Trends Neurosci 13: 281-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desban M, Kemel ML, Glowinski J, Gauchy C (1993) Spatial organization of patch and matrix compartments in the rat striatum. Neuroscience 57: 661-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty AW, Graybiel AM (1991) Corticostriatal transformations in the primate somatosensory system. Projections from physiologically mapped body-part representations. J Neurophysiol 66: 1249-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty AW, Graybiel AM (1993) Two input systems for body representations in the primate striatal matrix: experimental evidence in the squirrel monkey. J Neurosci 13: 1120-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrieli J (1995) Contributions of the basal ganglia to skill learning and working memory in humans. In: Models of information processing in the basal ganglia (Houk JC, Davis JL, Beiser DG, eds), pp 277-294. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

- Geinisman Y (1993) Perforated axospinous synapses with multiple, completely partitioned transmission zones: probable structural intermediates in synaptic plasticity. Hippocampus 3: 417-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geinisman Y, de Toledo-Morrell L, Morrell F, Persina IS, Beatty MA (1996) Synapse restructuring associated with the maintenance phase of hippocampal long-term potentiation. J Comp Neurol 368: 413-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR (1992) The neostriatal mosaic: multiple levels of compartmental organization in the basal ganglia. Annu Rev Neurosci 15: 285-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Engber TM, Mahan LC, Susel Z, Chase TN, Monsma Jr FJ, Sibley DR (1990) D1 and D2 dopamine receptor-regulated gene expression of striatonigral and striatopallidal neurons. Science 250: 1429-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM, Kimura M (1995) Adaptive neural networks in the basal ganglia. In: Models of information processing in the basal ganglia (Houk JC, Davis JL, Beiser DG, eds), pp 103-116. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

- Hersch SM, Ciliax BJ, Gutekunst CA, Rees HD, Heilman CJ, Yung KK, Bolam JP, Ince E, Yi H, Levey AI (1995) Electron microscopic analysis of D1 and D2 dopamine receptor proteins in the dorsal striatum and their synaptic relationships with motor corticostriatal afferents. J Neurosci 15: 5222-5237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffer ZS, Alloway KD (2001) Organization of corticostriatal projections from the vibrissal representations in the primary motor and somatosensory cortical areas of rodents. J Comp Neurol 439: 87-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger DJ, Gilman S, Aldridge JW (1995) Neuronal activity in the striatum and pallidum of primates related to the execution of externally cued reaching movements. Brain Res 694: 111-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Wilson CJ, Emson PC (1990) Projection subtypes of rat neostriatal matrix cells revealed by intracellular injection of biocytin. J Neurosci 10: 3421-3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry P, Wilson CJ, Kitai ST (1984) Morphological and electrophysiological characteristics of pyramidal tract neurons in the rat. Exp Brain Res 57: 177-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei WL, Deng YP, Laverghetta AV, Reiner A (2004) Thalamic input to striatonigral and striatopallidal projection neurons in rats. Soc Neurosci Abstr, in press.

- Le Moine C, Bloch B (1995) D1 and D2 dopamine receptor gene expression in the rat striatum: sensitive cRNA probes demonstrate prominent segregation of D1 and D2 mRNAs in distinct neuronal populations of the dorsal and ventral striatum. J Comp Neurol 355: 418-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester J, Fink S, Aronin N, DiFiglia M (1993) Colocalization of D1 and D2 dopamine receptor mRNAs in striatal neurons. Brain Res 621: 106-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque M, Parent A (1998) Axonal arborization of corticostriatal and corticothalamic fibers arising from prelimbic cortex in the rat. Cereb Cortex 8: 602-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque M, Charara A, Gagnon S, Parent A, Descenes M (1996a) Corticostriatal projections from layer V cells in rat are collaterals of long-range corticofugal axons. Brain Res 709: 311-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque M, Gagnon S, Parent A, Descenes M (1996b) Axonal arborizations of corticostriatal and corticothalamic fibers arising from the second somatosensory area in the rat. Cereb Cortex 6: 759-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden CD, Obeso JA (1994) The functions of the basal ganglia and the paradox of stereotaxic surgery in Parkinson's disease. Brain 117: 877-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R (1975) Distribution and properties of commissural and other neurons in cat sensorimotor cortex. J Comp Neurol 164: 361-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mink JW (1996) The basal ganglia: focused selection and inhibition of competing motor programs. Prog Neurobiol 50: 381-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka H, Jinnai K (1978) Common projection of the motor cortex to the caudate nucleus and the cerebellum. Exp Brain Res 31: 31-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent A, Smith Y, Filion M, Dumas J (1989) Distinct afferents to the internal and external pallidal segments in the squirrel monkey. Neurosci Lett 96: 140-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent A, Charara A, Pinault D (1995) Single striatofugal axons arborizing in both pallidal segments and in the substantia nigra in primates. Brain Res 698: 280-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy HB, Graybiel AM (1997) Cortically driven immediate early gene expression reflects modular influence of sensorimotor cortex on identified striatal neurons in the squirrel monkey. J Neurosci 17: 2477-2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C (1998) The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates, Ed 4. New York: Academic.

- Reiner A, Anderson KD (1990) The patterns of neurotransmitter and neuropeptide co-occurrence among striatal projection neurons: conclusions based on recent findings. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 15: 251-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Veenman CL, Medina L, Jiao Y, Del Mar N, Honig MG (2000) Pathway tracing using biotinylated dextran amines. J Neurosci Methods 103: 23-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Jiao Y, Del Mar N, Laverghetta AV, Lei WL (2003) Differential morphology of pyramidal-tract type and intratelencephalically-projecting type corticostriatal neurons and their intrastriatal terminals in rats. J Comp Neurol 457: 420-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadikot AF, Parent A, Smith Y, Bolam JP (1992) Efferent connections of the centromedian and parafascicular thalamic nuclei in the squirrel monkey: a light and electron microscopic study of the thalamostriatal projection in relation to striatal heterogeneity. J Comp Neurol 320: 228-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidibe M, Smith Y (1996) Differential synaptic innervation of striatofucal neurones projecting to the internal or external segments of the globus pallidus by thalamic afferents in the squirrel monkey. J Comp Neurol 365: 445-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Pothos EN (2000) Regulation of quantal size by presynaptic mechanisms. Rev Neurosci 11: 159-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmeier DJ, Reiner A, Ariano MA, Levine MS (1993) Are neostriatal dopamine receptors co-localized? Trends Neurosci 16: 299-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmeier DJ, Song WJ, Yan Z (1996) Coordinated expression of dopamine receptors in neostriatal medium spiny neurons. J Neurosci 16: 6579-6591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topni N, Buchs PA, Nikonenko I, Povilaitite P, Parisi L, Muller D (2001) Remodeling of synaptic membranes after induction of long-term potentiation. J Neurosci 21: 6245-6251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RS, DeLong MR (2000) Corticostriatal activity in primary motor cortex of the macaque. J Neurosci 20: 7096-7108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl GR, Navia B, Douglas J (1988) Differential expression of PPE and preprodynorphin mRNAs in striatal neurons: high levels of PPE expression depend on cerebral cortical afferents. J Neurosci 8: 4755-4764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Pickel VM (2002) Dopamine D2 receptors are present in prefrontal cortical afferents and their targets in patches of the rat caudateputamen nucleus. J Comp Neurol 442: 392-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HB, Foehring R, Deng YP, Sun Z, Yamamoto K, Reiner A (2002) Single-cell RT-PCR and in situ hybridization histochemistry (ISHH) of substance P (SP) and enkephalin (ENK) co-occurrence in striatal projection neurons in rats. Soc Neurosci Abstr 28: 359.15. [Google Scholar]

- Waszczak BL, Martin LO, Greif GJ, Freedman JE (1998) Expression of a dopamine D2 receptor-activated K+ channel on identified striatopallidal and striatonigral neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 11440-11444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CJ (1987) Morphology and synaptic connections of crossed corticostriatal neurons in the rat. J Comp Neurol 263: 567-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CJ (1992) Dendritic morphology, inward rectification and the functional properties of neostriatal neurons. In: Single neuron computation (McKenna T, J Davis, Kornetzer SF, eds), pp 141-171. San Diego: Academic.

- Wilson CJ, Groves PM, Kitai ST, Linder JC (1983) Three-dimensional structure of dendritic spines in the rat neostriatum. J Neurosci 3: 383-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouterlood FG, Pattiselanno A, Jorritsm-Byham B, Arts MPM, Meredith GE (1993) Connectional, immunocytochemical and ultrastructural characterization of neurons injected intracellularly in fixed brain tissue. In: Morphological investigations of single neurons in vitro (Meredith GE, Arbuthnott GW, eds), pp 47-169. New York: Wiley.

- Wright AK, Norrie L, Ingham CA, Hutton AM, Arbuthnott GW (1999) Double anterograde tracing of the outputs from adjacent “barrel columns” of rat somatosensory cortex neostriatal projection patterns and terminal ultrastructure. Neuroscience 88: 119-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AK, Ramanthan S, Arbuthnott GW (2001) Identification of the source of the bilateral projection system from cortex to somatosensory neostriatum and an exploration of its physiological actions. Neuroscience 103: 87-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Richard S, Parent A (2000) The organization of the striatal output system: a single-cell juxtacellular labeling study in the rat. Neurosci Res 38: 49-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemanick MC, Strick PL, Dix RD (1991) Direction of transneuronal transport of herpes simplex virus 1 in the primate motor system is strain-dependent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 8048-8051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]