Abstract

Introduction

Sarcopenia in the lumbar paraspinal muscles is receiving renewed attention as a cause of spinal degeneration. However, there are few studies on the precise concept and diagnostic criteria for spinal sarcopenia. Here, we develop the concept of spinal sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults. In addition, we aim to observe the natural ageing process of paraspinal and back muscle strength and investigate the association between conventional sarcopenic indices and spinal sarcopenia.

Methods and analysis

This is a prospective observational cohort study with 120 healthy community-dwelling older adults over 4 years. All subjects will be recruited in no sarcopenia, possible sarcopenia or sarcopenia groups. The primary outcomes of this study are isokinetic back muscle strength and lumbar paraspinal muscle quantity and quality evaluated using lumbar spine MRI. Conventional sarcopenic indices and spine specific outcomes such as spinal sagittal balance, back performance scale and Sorenson test will also be assessed.

Ethics and dissemination

Before screening, all participants will be provided with oral and written information. Ethical approval has already been obtained from all participating hospitals. The study results will be disseminated in peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations.

Trial registration number

Keywords: sarcopenia, spine, paraspinal muscles, lumbosacral region

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is a prospective cohort study in healthy community-dwelling older adults, to develop the concept of spinal sarcopenia, by observing the natural ageing process of paraspinal muscle and back muscle strength and investigating the association between conventional sarcopenic indices and spinal sarcopenia.

Standardised data evaluation for sarcopenia and the function of spinal extensor muscles will be used for the analysis with an application of relevant statistical methods.

Sample size was evaluated based on calculation of feasibility study due to the absence of previous literature concerning isokinetic back muscle strength or lumbar paraspinal muscle quantity.

Introduction

Sarcopenia is the age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass and function. It is a problem of muscle mass, muscle strength and performance.1 2 It can also be defined as a syndrome characterised by progressive and generalised loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength with a risk of adverse outcomes such as physical disability, poor quality of life (QoL) and death.3 The loss of muscle mass plays an important role in the frailty process of older adults, being a key player of its latent phase and explaining many aspects of the frailty status itself.4

Does sarcopenia affect the spine? It is not difficult to answer the question if we think about the anatomy of the spine. While skeletal bone is the frame and there are neural tissues inside the spinal canal, almost all surrounding tissues are skeletal muscles. There are huge extensor muscles at the posterior part of the spine and iliopsoas muscles also exist bilaterally around the spine. Thus, it is inevitable for sarcopenia to impact the spine. Receiving renewed attention is sarcopenia of the lumbar paraspinal muscles as a cause of spinal degeneration. Both the atrophy and fatty change of paraspinal muscles originating from sarcopenia are also known to be associated with functional disorders and chronic back pain.5 We want to suggest classifying this phenomenon as ‘spinal sarcopenia’. However, there are few studies on the precise concept and diagnostic criteria for spinal sarcopenia and no clinical trials to determine whether it can be treated or prevented by strengthening exercise or nutritional support.

Classical sarcopenia indices proposed by several sarcopenia working groups6 7 to date cannot be used to diagnose spinal sarcopenia. While feasible, inexpensive and less radiation-exposed tools such as dual energy X-ray absorptiometry have been used to measure appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASM), paraspinal muscle assessment still requires the use of spinal CT or MRI. In addition, spinal extensor strength measurement is necessary to confirm the function of the lumbar paraspinal muscle, but isokinetic strength measuring equipment for accurate measurement is not as feasible as a hand-grip strength dynamometer to evaluate sarcopenia. Furthermore, many older adults may experience pain during the measurement of spinal extension strength.

Therefore, it is necessary to develop a simple, accessible and clinically meaningful measurement index to confirm the function of spinal extensor muscles. In this prospective cohort study, we will investigate the basic data of sarcopenia and physical function as well as spine imaging (MRI and X-ray), back performance, spinal sagittal balance (SSB) and back extensor strength in 120 healthy older adults. Based on this, we will analyse the correlation between baseline sarcopenia, spinal functional index, SSB index and physical function. Furthermore, we will observe the natural ageing process of these indicators through long-term follow-up over 4 years.

Objectives

To develop the concept of spinal sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults.

In addition, we aim to observe the natural ageing process of paraspinal muscle and back extensor strength and investigate the association between conventional sarcopenic indices and spinal sarcopenia.

Method and analysis

Study design

This is a prospective observational cohort study with 120 healthy community-dwelling older adults in a single centre (SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center). Individual follow-up will last 4 years.

Participants and eligibility criteria

Older adults (≥65 years old) who are community-dwellers and able to walk with or without assistive devices will be included. Participants who have experienced the following will be excluded: (1) low back pain with moderate severity (numeric rating scale8 5 and over); (2) history of any types of lumbar spine surgery; (3) history of hip fracture surgery and arthroplasty of hip or knee; (4) contraindications for MRI (such as cardiac pacemaker, implanted metallic objects and claustrophobia); (5) disorders in central nervous system (such as stroke, parkinsonism, spinal cord injury); (6) cognitive dysfunction (Mini Mental State Examination score<24); (7) communication disorder (such as severe hearing loss); (8) musculoskeletal condition affecting physical function (such as amputation of limb); (9) long-term use of corticosteroids due to inflammatory disease; (10) malignancy requiring treatment within 5 years and (11) other medical conditions which need active treatment; patients who refuse to participate in a study will also be excluded.

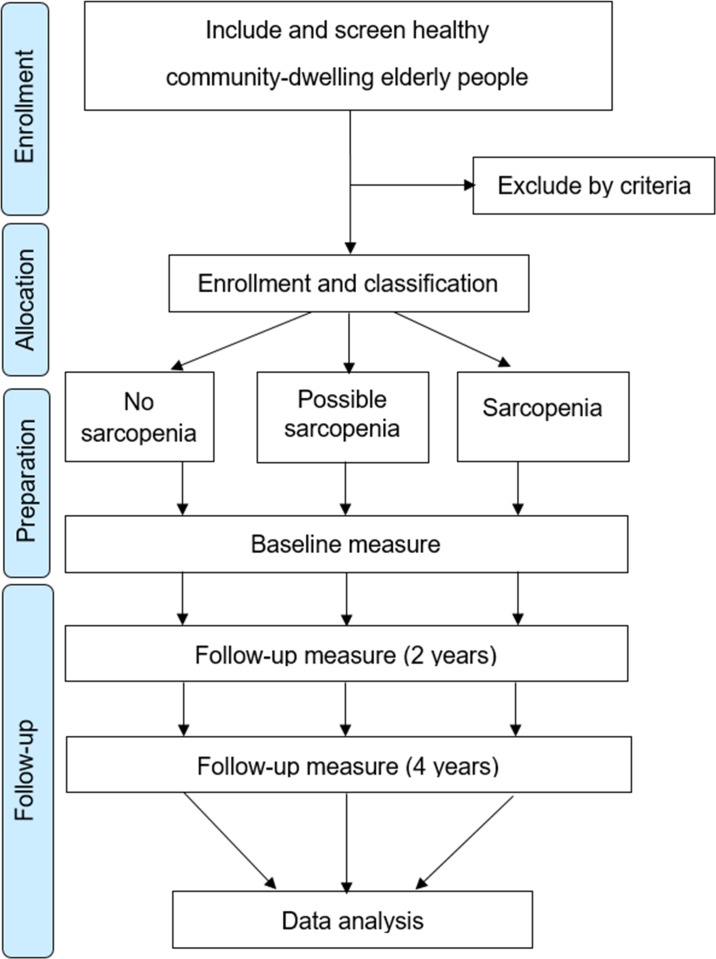

Sarcopenia can be divided into two stages: (1) possible sarcopenia (PS) defined by low handgrip strength and/or low gait speed and (2) sarcopenia (SA) confirmed by low handgrip strength and/or low gait speed and low muscle mass defined by the consensus report of the Asian working group for sarcopenia.6 A no sarcopenia (NS) group is added to this classification, and the study participants are classified into three groups (NS, PS and SA) after the screening tests (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the cohort study.

Outcomes measures

Primary outcome measures

-

Isokinetic back muscle strength

The investigators will use the isokinetic dynamometer (Biodex multi-joint system, Biodex, Shirley, New York, USA) to measure the torque of the back extensors. Briefly, the examination will be performed by seating the patient comfortably in the device, fixing both the thighs and the back to the chair using a strap and asking the patient to hold the handle placed near the front, at the chest, to measure upper limb and hip joint motions. The dynamometer axis will be located on the anterior superior iliac spine of the patient’s pelvis. All patients will be instructed to flex and extend the back five times at an angular velocity of 60°/s as a warm-up before the examination. During the examination, patients will be instructed to execute flexion and extension of the back, with a maximum effort, 10 times at an angular velocity of 60°/s. The back range of movement was 22 limited at 50°, with 30° (−30°) of trunk flexion and 20° (+20°) of trunk extension, relative to the anatomical reference position (0°).9 The device will measure the peak torque (PT) (N m) and the peak torque per body weight (PT/Bwt) (N m/kg).10

-

Lumbar paraspinal muscle quantity and quality

Lumbar spine MRI will be performed using a 1.5 T scanner (Achieva 1.5T; Philips Healthcare, Netherlands). Subjects will be placed in the supine position with the lumbar spine in a neutral position and a pillow under their head and knees. The imaging protocol will include sagittal T2-weighted fast spin echo imaging (repetition time, 3200 ms/echo; echo time, 100 ms; echo-train length, 20; section thickness, 4 mm and field of view, 300×300 mm) and axial T2-weighted fast spin echo imaging (repetition time, 3500 ms/echo; echo time, 100 ms; echo-train length, 20; section thickness, 4 mm and field of view, 200×200 mm). Axial images will be obtained for each lumbar intervertebral level (T12/L1-L5/S1) parallel to the vertebral endplates with five slices at each intervertebral level.

The measurement of the cross sectional area (CSA) and fatty infiltration ratio (FI %) of the paraspinal muscles (erector spinae (ES), multifidus (MF) and psoas major (PM)) will be performed with axial T2-weighted images using a radiological workstation (MEDIP; Medical IP, Seoul, South Korea) specially designed for such purposes. The measurement of ES and MF will be performed from the level of L1/L2 to L5/S1 and that of PM will be performed at the level of L4/5. The CSA will be measured by manually constructing free-draw points around the outer margins of the individual muscles using touch screen LCD monitor (XPS 15 9570, Dell, Round Rock, Texas, USA) and digital touch screen pen (PN556W Dell Active Pen, Dell, Round Rock, Texas, USA). The FI % is defined as the percentage of fatty infiltration area, which is obtained by dividing the fatty infiltration area by the total area. The CSA and FI % of paraspinal muscles will be separately measured on the bilateral sides, and mean values will be calculated.11

Secondary outcome measures

-

Conventional sarcopenic indices

ASM: Both dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Lunar iDXA for Bone Health; GE Healthcare, Schenectady, New York, USA) and bioimpedance analysis (InBody 720; Biospace, Seoul, South Korea) will be used to analyse body composition including lean body and fat masses. ASM will be calculated by obtaining the sum of the lean mass in bilateral upper and lower extremities12 and standardised by being divided by the squared height value (ASM/Ht,2 kg/m2).

Handgrip strength: It will be measured using a hand-grip dynamometer (T.K.K.5401; Takei Scientific Instruments, Tokyo, Japan),13 as described previously.14 Briefly, while sitting in a straight-backed chair with their feet flat on the floor, patients will be asked to adduct and neutrally rotate the shoulder, flex the elbow to 90° and place the forearm in a neutral position, with the wrist between 0° and 30° extension and between 0° and 15° ulnar deviation. Subjects will be instructed to squeeze the handle as hard as possible for 3 s and the maximum contraction force (kg) will be recorded.

Short physical performance battery (SPPB): Functional examination using SPPB derived from three objective physical function tests (ie, the time taken to cover 4 m at a comfortable walking speed, time taken to stand from sitting in a chair five times without stopping and ability to maintain balance for 10 s in three different foot positions at progressively more challenging levels).15 A score from 0 to 4 will be assigned to performance on each task, with higher scores indicating better lower body function.

-

Spine-specific outcomes

Isometric back muscle strength: In addition to the isokinetic back muscle strength test, we will perform the isometric back muscle strength test using a handheld dynamometer (PowerTrack II; JTECH Medical, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA). This will involve the participant standing in full extension with their back to a wall, midway between two vertically oriented anchor rails and feet flat on the floor with heels touching the wall. An inelastic belt will be looped through the anchor rails and secured firmly around the participant, 1 cm below the anterior superior iliac spines, in order to restrain movement and maintain participant contact with the wall during the test. To standardise posture, arms will be crossed over the chest, with fingertips level with the contralateral shoulders. The participant will be instructed to flex forward approximately 15° at the hips so the handheld dynamometer can be positioned posterior to the spinous process of the seventh thoracic vertebrae. In this way, counter pressure will be provided by the fixed wall behind the participants’ back so that variations in resistance by an examiner will be avoided.16

SSB: For each participant, one lateral radiograph of the whole spine will be made and digitised. All measurements will be performed by means of imaging software (INFINITT PACS M6; INFINITT Healthcare, Seoul, South Korea), as previously described.17 18 Briefly, the following spinopelvic radiographic parameters will be analysed: sacral slope, pelvic incidence (PI), pelvic tilt, lumbar lordosis (LL), thoracic kyphosis (TK), the ratio of LL to PI (LL/PI), PI-LL mismatch (PI-LL; the difference between the PI and LL) and sagittal vertical axis. PI-LL will be used as the primary outcomes of SSB.19

Back performance scale (BPS): BPS consists of five tests: Sock Test, the Pick-up Test, the Roll-up Test, the Fingertip-to-Floor Test and the Lift Test. The five tests comprising the BPS demonstrate associations with each other, and each test contributes to high internal consistency, implying that the tests share a common characteristic in measuring physical performance.20 The BPS sum score (0–15) is calculated by adding the individual scores of the five tests.

Sorensen test: It is the most widely used test in published studies evaluating the isometric endurance of the trunk extensor muscles. The test consists of measuring the amount of time a person can hold the unsupported upper body in a horizontal prone position with the lower body fixed to the examining table.21

-

Other functional outcomes

Berg balance scale (BBS): Balance and fall risk will be assessed using BBS (range: 0–56; a lower score indicates a worse outcome).22

QoL: It will be evaluated using the Euro Quality of Life Questionnaire five-dimensional classification (range: 0–1; a lower score indicates a worse outcome).23

Activities of daily living (ADLs): ADLs will be determined using the Korean version of the modified Barthel index24 (K-MBI; range: 0–100; a lower score indicates a worse outcome) and the Korean version of the Instrumental ADL (K-IADL; range: 0–3; a higher score indicates a worse outcome).25

Frailty: It will be assessed based on fatigue, resistance, ambulation, illnesses and loss of weight (FRAIL) using the Korean version of the FRAIL scale (K-FRAIL; range: 0–5; a lower score indicates a worse outcome).26

-

Serum examination

Serum chemistry, complete blood counts, blood urea nitrogen and creatinine will be obtained.

Interleukin-6 level will be quantified by Green-Cross laboratory (GC lab, Seoul, Korea) using standard procedures.

All outcome variables will be collected at baseline, 2 and 4 years. However, L-S spine MRI for lumbar paraspinal muscle quantity and quality will be performed only at baseline (table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of the outcome measures and time points of assessment

| Screening | Baseline | 2 years | 4 years | |

| Eligibility | X | |||

| Eligibility confirmation | X | |||

| Informed consent | X | |||

| Demographic information | X | |||

| Medical history | X | X | X | |

| Body composition (image study) | ||||

| Wholebody DEXA and BIA | BIA | DEXA | X | X |

| Whole spine X-ray (lateral) | X | X | X | |

| L-S spine MRI | X | |||

| Function and performance | ||||

| Handgrip strength | X | X | X | X |

| Gait function | X | X | X | X |

| SPPB | X | X | X | |

| Physical activity | X | X | X | |

| Balance function | X | X | X | |

| Spine performance | ||||

| Isokinetic back muscle strength | X | X | X | |

| Isometric back muscle strength | X | X | X | |

| Sorenson test | X | X | X | |

| Back performance scale | X | X | X | |

| Others | ||||

| Frailty | X | X | X | |

| QoL questionnaire | X | X | X | |

| Activity daily living | X | X | X | |

| Laboratory test with biomarker | X | X | X | |

BIA, bio-impedance analysis;DEXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry;QoL, quality of life; SPPB, short physical performance battery.

Data analysis

Data will be collected using a standardised data entry form and entered into the data management system. Participant characteristics will be described using means and SD for continuous data and frequencies and percentages for categorical data. The three groups will be compared using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the non-parametric equivalence, a Kruskal–Wallis test, if required. To compare paired data (intragroup) between two different points, we will use repeated-measures ANOVA and Friedman tests for continuous and non-parametric data, respectively. Statistical significance will be defined as a p<0.05. All statistical analyses will be performed using SPSS V.19.0 for Windows (IBM, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Sample size

We intended to perform the sample size calculation based on the difference in mean of isokinetic back muscle strength or lumbar paraspinal muscle quantity among groups. However, there was no literature available concerning isokinetic back muscle strength or lumbar paraspinal muscle quantity in general practices or hospitals, let alone effect sizes. Therefore, we based our sample size calculation on feasibility. A total of 120 subjects will be recruited in order to ensure 20 male and 20 female participants per group, in three groups (NS, PS and SA groups) based on sarcopenia.

Patient and public involvement

While participants were not involved in the development of the research question and the selection of outcome measures, their needs and preferences were considered throughout the process. Feedback to the participants regarding scientific results, will be organised on each study site.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol is approved by the institutional review board of Seoul Metropolitan Government Seoul National University (SMG-SNU) Boramae Medical Centre (IRB No. 20-2019-19). The study will be performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, 1964, as amended in Tokyo, 1975; Venice, 1983; Hong Kong, 1989 and Somerset West, 1996.27 Written informed consent for all interventions and examinations will be obtained at patient admission. The Ethics Board will be informed of all serious adverse events and any unanticipated adverse effects that occur during the study. The study protocol has been registered at Clinicaltrials.gov and will be updated. Direct access to the source data will be provided for monitoring, audits, Research Ethics Committee (REC)/Institutional Review Board (IRB) review and regulatory authority inspections during and after the study. All patient information will be coded anonymously, with only the study team having access to the original data. The study results will be disseminated in peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations.

Discussion

Skeletal muscle mass measurement to define sarcopenia has mainly been based on the sum of muscle mass in the limbs (appendicular limb muscle mass). However, the question remains whether this sum of limb muscle mass is associated with muscle function throughout the whole body. Lee et al reported that degenerative arthritis of the knee joint was associated with only lower limb muscle mass, but not with upper limb muscle mass.28 Recently, Jeon et al also suggested that the sum of limb muscle mass was not correlated with the radiological degenerative changes of the lumbar spine and hip joint.29 Therefore, site-specific muscle mass investigation is necessary to evaluate the effect of skeletal muscle on specific regions.

Currently, SSB is an important indicator of outcomes of lumbar spine surgery,30 and even non-operative treatment of spinal stenosis.31 While SSB can be affected by sex32 and ethnicity,33 ageing is the most important cause of spinal sagittal imbalance.34 Decreased LL is an important cause of spinal sagittal imbalance, and it is known to originate from the wedging or decreased height of the intervertebral discs in the absence of vertebral compression fractures.35 36 However, spinal sagittal imbalance is difficult to explain only by the height of the intervertebral discs or vertebral bodies. Therefore, we can hypothesise that spinal sarcopenia is one of the causes of spinal sagittal imbalance which the current cohort study will prove.

Several specific assessments such as CSA of paraspinal muscles, back muscle strength and back performance test are required to evaluate spinal sarcopenia. However, unlike limb skeletal muscles, the functional evaluation of the spine corresponding to the centre of the body is not practical. Thus, this cohort study will investigate the value of SSB as a substitute for back muscle strength and performance measurement. In other words, if back muscle strength and functional impairment are directly related to the spinal sagittal imbalance, a simple measurable SSB may be a useful index to represent spinal muscle function.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SYL conceived the study and is the principal investigator. JCK, S-UL, SHJ, J-YL and DHK contributed to the development of the study. All authors approved the version to be published and are responsible for its accuracy.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2019R1C1C100632).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Doherty TJ. Invited review: aging and sarcopenia. J Appl Physiol 2003;95:1717–27. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00347.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morley JE. Sarcopenia: diagnosis and treatment. J Nutr Health Aging 2008;12:452–6. 10.1007/BF02982705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Delmonico MJ, Harris TB, Lee J-S, et al. Alternative definitions of sarcopenia, lower extremity performance, and functional impairment with aging in older men and women. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:769–74. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01140.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pedone C, Costanzo L, Cesari M, et al. Are performance measures necessary to predict loss of independence in elderly people? GERONA 2016;71:84–9. 10.1093/gerona/glv096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Masaki M, Ikezoe T, Fukumoto Y, et al. Association of sagittal spinal alignment with thickness and echo intensity of lumbar back muscles in middle-aged and elderly women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2015;61:197–201. 10.1016/j.archger.2015.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen L-K, Liu L-K, Woo J, et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian Working group for sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:95–101. 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European Working group on sarcopenia in older people. Age Ageing 2010;39:412–23. 10.1093/ageing/afq034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Childs JD, Piva SR, Fritz JM. Responsiveness of the numeric pain rating scale in patients with low back pain. Spine 2005;30:1331–4. 10.1097/01.brs.0000164099.92112.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Juan-Recio C, Lopez-Plaza D, Barbado Murillo D, et al. Reliability assessment and correlation analysis of 3 protocols to measure trunk muscle strength and endurance. J Sports Sci 2018;36:357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee HJ, Lim WH, Park J-W, et al. The relationship between cross sectional area and strength of back muscles in patients with chronic low back pain. Ann Rehabil Med 2012;36:173–81. 10.5535/arm.2012.36.2.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sasaki T, Yoshimura N, Hashizume H, et al. Mri-Defined paraspinal muscle morphology in Japanese population: the Wakayama spine study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0187765 10.1371/journal.pone.0187765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baumgartner RN, Koehler KM, Gallagher D, et al. Epidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New Mexico. Am J Epidemiol 1998;147:755–63. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pedrero-Chamizo R, Albers U, Tobaruela JL, et al. Physical strength is associated with Mini-Mental state examination scores in Spanish institutionalized elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2013;13:1026–34. 10.1111/ggi.12050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ro HJ, Kim D-K, Lee SY, et al. Relationship between respiratory muscle strength and conventional sarcopenic indices in young adults: a preliminary study. Ann Rehabil Med 2015;39:880–7. 10.5535/arm.2015.39.6.880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, et al. Lower-Extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med 1995;332:556–62. 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harding AT, Weeks BK, Horan SA, et al. Validity and test–retest reliability of a novel simple back extensor muscle strength test. SAGE Open Med 2017;5 10.1177/2050312116688842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vialle R, Levassor N, Rillardon L, et al. Radiographic analysis of the sagittal alignment and balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:260–7. 10.2106/JBJS.D.02043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buckland AJ, Ramchandran S, Day L, et al. Radiological lumbar stenosis severity predicts worsening sagittal malalignment on full-body standing stereoradiographs. Spine J 2017;17:1601–10. 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koller H, Pfanz C, Meier O, et al. Factors influencing radiographic and clinical outcomes in adult scoliosis surgery: a study of 448 European patients. Eur Spine J 2016;25:532–48. 10.1007/s00586-015-3898-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Strand LI, Moe-Nilssen R, Ljunggren AE. Back performance scale for the assessment of mobility-related activities in people with back pain. Phys Ther 2002;82:1213–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Demoulin C, Vanderthommen M, Duysens C, et al. Spinal muscle evaluation using the Sorensen test: a critical appraisal of the literature. Joint Bone Spine 2006;73:43–50. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2004.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Berg K, Wood-Dauphinee S, Williams JI. The balance scale: reliability assessment with elderly residents and patients with an acute stroke. Scand J Rehabil Med 1995;27:27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Group TE EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jung HY, Park BK, Shin HS, et al. Development of the Korean version of modified Barthel index (K-MBI): multi-center study for subjects with stroke. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med 2007;31:283–97. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Won CW, Yang KY, Rho YG, et al. The development of Korean activities of daily living (K-ADL) and Korean instrumental activities of daily living (K-IADL) scale. J Korean Geriatr Soc 2002;6:107–20. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jung H-W, Yoo H-J, Park S-Y, et al. The Korean version of the frail scale: clinical feasibility and validity of assessing the frailty status of Korean elderly. Korean J Intern Med 2016;31:594–600. 10.3904/kjim.2014.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dale O, Salo M. The Helsinki Declaration, research guidelines and regulations: present and future editorial aspects. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1996;40:771–2. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1996.tb04530.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee SY, Ro HJ, Chung SG, et al. Low skeletal muscle mass in the lower limbs is independently associated to knee osteoarthritis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0166385 10.1371/journal.pone.0166385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jeon H, Lee S-U, Lim J-Y, et al. Low skeletal muscle mass and radiographic osteoarthritis in knee, hip, and lumbar spine: a cross-sectional study. Aging Clin Exp Res 2019;41 10.1007/s40520-018-1108-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hikata T, Watanabe K, Fujita N, et al. Impact of sagittal spinopelvic alignment on clinical outcomes after decompression surgery for lumbar spinal canal stenosis without coronal imbalance. J Neurosurg 2015;23:451–8. 10.3171/2015.1.SPINE14642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Beyer F, Geier F, Bredow J, et al. Influence of spinopelvic parameters on non-operative treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. Technol Health Care 2015;23:871–9. 10.3233/THC-151032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sinaki M, Itoi E, Rogers JW, et al. Correlation of back extensor strength with thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis in estrogen-deficient WOMEN1. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1996;75:370–4. 10.1097/00002060-199609000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhu Z, Xu L, Zhu F, et al. Sagittal alignment of spine and pelvis in asymptomatic adults: norms in Chinese populations. Spine 2014;39:E1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gelb DE, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, et al. An analysis of sagittal spinal alignment in 100 asymptomatic middle and older aged volunteers. Spine 1995;20:1351–8. 10.1097/00007632-199520120-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Takeda N, Kobayashi T, Atsuta Y, et al. Changes in the sagittal spinal alignment of the elderly without vertebral fractures: a minimum 10-year longitudinal study. J Orthop Sci 2009;14:748–53. 10.1007/s00776-009-1394-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Frobin W, Brinckmann P, Kramer M, et al. Height of lumbar discs measured from radiographs compared with degeneration and height classified from Mr images. Eur Radiol 2001;11:263–9. 10.1007/s003300000556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.