Abstract

Objective

Fostering clinical reasoning is a mainstay of medical education. Based on the clinicopathological conferences, we propose a case-based peer teaching approach called clinical case discussions (CCDs) to promote the respective skills in medical students. This study compares the effectiveness of different CCD formats with varying degrees of social interaction in fostering clinical reasoning.

Design, setting, participants

A single-centre randomised controlled trial with a parallel design was conducted at a German university. Study participants (N=106) were stratified and tested regarding their clinical reasoning skills right after CCD participation and 2 weeks later.

Intervention

Participants worked within a live discussion group (Live-CCD), a group watching recordings of the live discussions (Video-CCD) or a group working with printed cases (Paper-Cases). The presentation of case information followed an admission-discussion-summary sequence.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Clinical reasoning skills were measured with a knowledge application test addressing the students’ conceptual, strategic and conditional knowledge. Additionally, subjective learning outcomes were assessed.

Results

With respect to learning outcomes, the Live-CCD group displayed the best results, followed by Video-CCD and Paper-Cases, F(2,87)=27.07, p<0.001, partial η2=0.384. No difference was found between Live-CCD and Video-CCD groups in the delayed post-test; however, both outperformed the Paper-Cases group, F(2,87)=30.91, p<0.001, partial η2=0.415. Regarding subjective learning outcomes, the Live-CCD received significantly better ratings than the other formats, F(2,85)=13.16, p<0.001, partial η2=0.236.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the CCD approach is an effective and sustainable clinical reasoning teaching resource for medical students. Subjective learning outcomes underline the importance of learner (inter)activity in the acquisition of clinical reasoning skills in the context of case-based learning. Higher efficacy of more interactive formats can be attributed to positive effects of collaborative learning. Future research should investigate how the Live-CCD format can further be improved and how video-based CCDs can be enhanced through instructional support.

Keywords: undergraduate medical education, case-based learning, clinical reasoning, social interaction, medical decision making

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First empirical study on the implementation of clinical case discussions in undergraduate medical education.

Comparison of clinical case discussions with differing grades of social interaction to determine their effectiveness on medical students’ acquisition of clinical reasoning skills by between-group analyses.

Implementation of multidimensional and multilayered test instruments in a pre-test, post-test and delayed post-test design to measure clinical reasoning skills with a knowledge application test and self-assessment.

The knowledge application test utilised in this study did not allow for a more in-depth analysis of clinical reasoning skills (ie, a distinction of conceptual, strategic and conditional knowledge).

Introduction

Curriculum developers face the challenge of implementing competence-oriented frameworks such as CanMEDS (Canada; http://www.royalcollege.ca/canmeds), NKLM (Germany; http://www.nklm.de) or PROFILES (Switzerland; http://www.profilesmed.ch), including the need to train clinical reasoning skills as a medical doctor’s key competence.1–3 As such, clinical reasoning skills are crucial not only for appropriate medical decision making but also to avoid diagnostic errors and the associated harm for both patients and healthcare systems.4

Case-based learning has been proposed to foster clinical reasoning skills5 and is well accepted among students.6 Case-based learning found an early representation in clinicopathological conferences (CPC, first introduced by Cannon in 19007) which are practised until today. The CPC conducted at the Massachusetts General Hospital are published on a regular basis known as the Case Records series of the New England Journal of Medicine. In those CPCs, the ‘medical mystery’8 presented by the case under discussion calls readers to think about the possible diagnosis themselves, before it is finally disclosed at the last part of the CPC. Despite the absence of definitive evidence for efficacy as a teaching method, CPCs have widely been used in medical education since the early 20th century to foster clinical reasoning.9–11 While CPC case records reach lots of medical readers around the world, they have been criticised as being anachronistic with a diagnosing ‘star’ (ie, the discussant), performing, acutely aware of being the centre of attention.12

Case-based learning formats are embedded in a context, which is known to promote learning better than providing facts in an abstract, non-contextual form.13 A definition found in the review by Merseth suggests three essential elements of a case: a case is real (ie, based on a real-life situation or event); it relies on careful research and study; it is ‘created explicitly for discussion and seeks to include sufficient detail and information to elicit active analysis and interpretation by users’.14 Cases may be represented by means of text, pictures, videos and the like. Realism and authenticity are varying features of cases,15 but particularly elaborated and authentic cases provide increased diagnostic challenge, comprising added value for medical training.16

However, due to their setup, CPCs are often passive learning situations for participants, as they listen to the discussant laying out his or her clinical reasoning on the case under discussion. According to the ICAP framework by Chi et al,17 teaching formats increase their efficacy from passive < active < constructive < interactive learning environments. Learning is enhanced when students interactively engage in discussions among each other. Accordingly, case-based learning has been found to be particularly beneficial in collaborative settings.15 However, another important aspect to consider in collaborative learning environments is that some students may participate passively, while others contribute disproportionately much. To foster optimal learning effects, students should thus be encouraged to be interactively engaged. One prerequisite to achieve self-guided learning in groups is a low threshold for students to come forward with their questions and participate in ensuing discussions.18 To this end, peer teaching has been established as an effective tool to stimulate discussions.19 To make sure peer tutors are not overwhelmed in moderating these discussions, the presence of an experienced clinician appears to be warranted20 in addition to a specific training of the tutors.

Taken together, while traditional CPCs encompass some important dimensions of effective case-based learning environments, they are not systematically aiming at constructive or interactive learner activities that are known features of effective teaching formats.17 21 Therefore, we introduced clinical case discussions (CCD) in undergraduate medical education to account for these features. We still use the case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital,9 as these cases exemplify realistic patient encounters and fulfil the criteria for an interactive collaborative learning process as explained above. In the CCD approach, cases are typically presented with information until the admission of the patient to the hospital. This event is usually the starting point of an interactive discussion phase of the group about possible diagnoses and diagnostic strategies. After all test results have been discussed, the actual diagnosis is disclosed and the pitfalls and take-home messages of the case are summarised.

To investigate the effectiveness of the CCD approach in undergraduate medical education, we designed an intervention trial and assessed clinical reasoning skills in medical students before and after participating in live CCDs or being exposed to video recordings of live CCDs. We compared these formats and their effects on clinical reasoning with the more traditional approach of working through written cases. When carrying out this randomised trial, we hypothesised that participation in live CCD sessions would lead to a higher increase of clinical reasoning skills than simply reading the cases. To better understand possible effects of the CCD learning environment with its social components on learning outcomes, participation in live CCDs as outlined above was additionally compared with the effects of watching videos of CCDs online. This comparison also seemed relevant from an economic point of view as videostreaming of lectures and seminars is prevalent at many institutions in higher education, allowing for flexible and scalable access to learning materials.22 To investigate the potential of different CCD formats for regular curricular use, we also measured subjective learning outcomes after the intervention and correlated student self-assessments with objective changes in their clinical reasoning skills.

Methods

Participants

Initially, we recruited 106 volunteer medical students at the Medical Faculty of LMU Munich. Randomisation was performed in a two-step procedure. First, we selected a sample of roughly 100 enrolled students. Next, we stratified participants by creating triplets on the basis of the variables age, gender, year of study, prior CCD participation and performance in a knowledge application pre-test. This was done in an effort to limit the risk of random misdistribution of the selected sample. From each triplet, we randomly assigned participants to the experimental groups. A total of 90 participants eventually completed the study, 31 of them were male and 59 female. They were aged 20–41 years (M=23; SD=2.97) and in their first to eighth clinical semester (M=3.50; SD=1.78).

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of LMU Munich (approval reference no. 222–15). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants and they received a financial reimbursement of 50 Euros on completion of the trial.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or public were involved in this research.

Study design

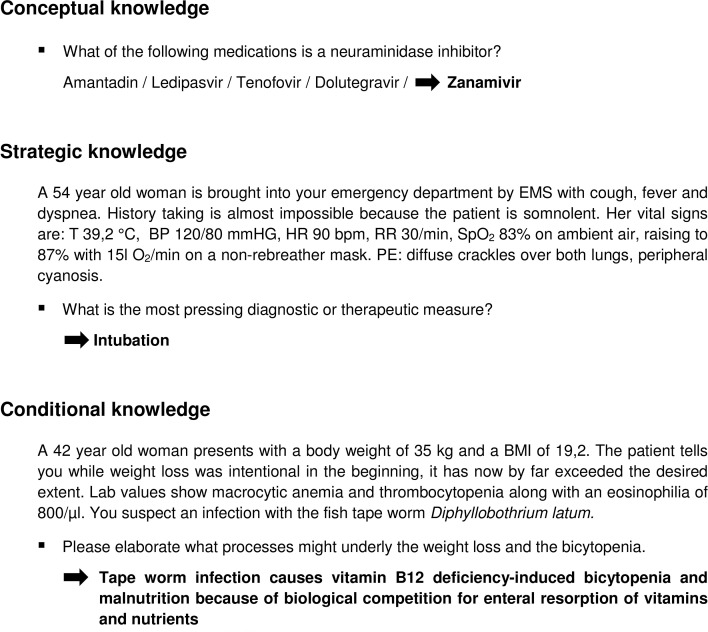

We conducted a single-centre randomised controlled trial consisting of a total of five course sessions with a parallel design (see figure 1). One week prior to the first CCD session, participants were introduced to the principles of the CCD approach and the sequence of this trial in an introductory session where they also took a knowledge application pre-test (T_0). In the experimental phase, participants attended 3 weekly interventional course sessions of 90 min each in one of three experimental groups with the respective CCD formats. Participants took a knowledge application post-test at the end of the last experimental course session (T_1), 4 weeks after pre-testing. A delayed knowledge application post-test was conducted 2 weeks after completion of the interventional courses (T_2); we deliberately chose that time interval to investigate the sustainability of possible effects while balancing the risk of postintervention confounding.23

Figure 1.

Study design. Full data sets of 90 medical students were analysed. T_0, knowledge application pre-test; T_1, knowledge application post-test; T_2, delayed knowledge application post-test.

Materials

In all experimental groups, the intervention was based on the same three, independent internal medicine cases. Chief complaints in these cases were paraesthesia (first session), fever and respiratory failure (second session) and rapidly progressive respiratory failure (third session).24–26 Cases were worked through in an iterative approach in different formats: (1) peer-moderated live case discussions in an interactive setting (Live-CCD, n=30), (2) a single-learner format utilising an interactive multimedia platform displaying video recordings of the live case discussions (Video-CCD, n=27) and (3) a single-learner format in which the students worked with the original paper cases of the NEJM (Paper-Cases, n=33). The cases were prepared in a way that participants in each format were exposed to the same case information.

Procedure

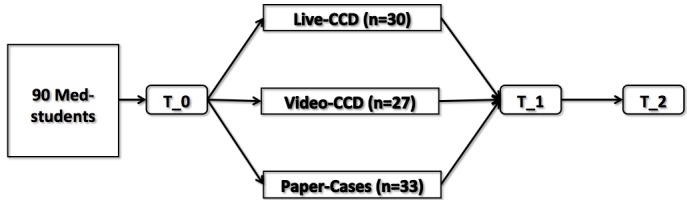

In all three groups, cases were presented in a specified structured manner similar to the original CPC (see figure 2). In each format, the students (‘discussants’) had to fill out a form after the admission in which the case had to be summarised and a list of clinical problems and working diagnoses had to be provided. Subsequently, between discussion and summary a second case summary had to be completed in which the final diagnostic test and the most likely diagnosis had to be proposed.

Figure 2.

Live-CCD structure. CCD sessions are divided into three parts. In the admission part, the presenting student shows the discussants his prepared slides (based on the original NEJM case record), after which the group has to agree on an assessment of the patient under discussion. In the interactive discussion part, the students prioritise the medical problems, link them to possible aetiologies and order tests to further corroborate or discard differential diagnoses. After all these tests have been discussed, students order the putative diagnostic test. The result is disclosed along with the pathological discussion and ‘take home messages’ on important differentials in the third part of the session. CBC, complete blood count; CC, chief complaint; CCD, clinical case discussion; CMP, comprehensive metabolic panel; CXR, chest radiograph; FH, family history; HPI, history of present illness; Meds, medications; PE, physical examination; PMH, past medical history; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; ROS, review of systems; SH, social history; UA, urine analysis; VS, vital signs.

In the Live-CCD group, the case presentation was prepared beforehand by a voluntary discussant (‘presenter’), who presented the facts in the admission (according to the structure shown in figure 2). Electronic slides and flipcharts were used to transport case information. Original test results were revealed by the presenter during the discussion only when requested by the group of students. Furthermore, the presenter summarised the differential diagnosis, important pathophysiological features of the case at the end of the session and provided a short take home message. The moderating medical students (‘moderator’) were recruited among previous CCD participants. They had experience in CCD moderation and had had an introductory training (2 days) in higher education methods and group facilitation prior to the study. The moderator facilitated the discussion process and ensured a reasonable approach to the patient encounter (eg, with respect to timing and hierarchy of ordered tests) in close communication with the discussants. Moreover, the moderator helped students develop their diagnostic strategy by co-evaluating their requested findings and the reasoning employed. Supervision of the correctness of medical facts and the correct diagnostic approach were ultimately granted by a clinician who could stop the discussion at any point when faulty reasoning was evident or discussants explicitly requested the facilitation of an experienced physician. The clinicians’ level of involvement into the discussion was left at their own discretion. We varied the staff between each Live-CCD to minimise effects of personal teacher characteristics. Live sessions typically lasted 90 min and were recorded with multiple cameras.

Students in the Video-CCD format worked on a single-learner multimedia workstation on which a video recording of the Live-CCD was displayed. These recordings also contained the electronic slide presentation from the Live-CCD and enabled simultaneous observation of the discussion from multiple camera angles. Participants could pause and partially skip the videos.

In the Paper-Cases group, participants received the case information of each CCD section sequentially (ie, admission, discussion, summary) in a print format. In both single-learner formats, students could choose their personal working speed. There was neither a prespecified minimum nor a maximum time they were required to work on the cases. In each of the three formats, full access to the internet was permitted for additional information.

Instruments

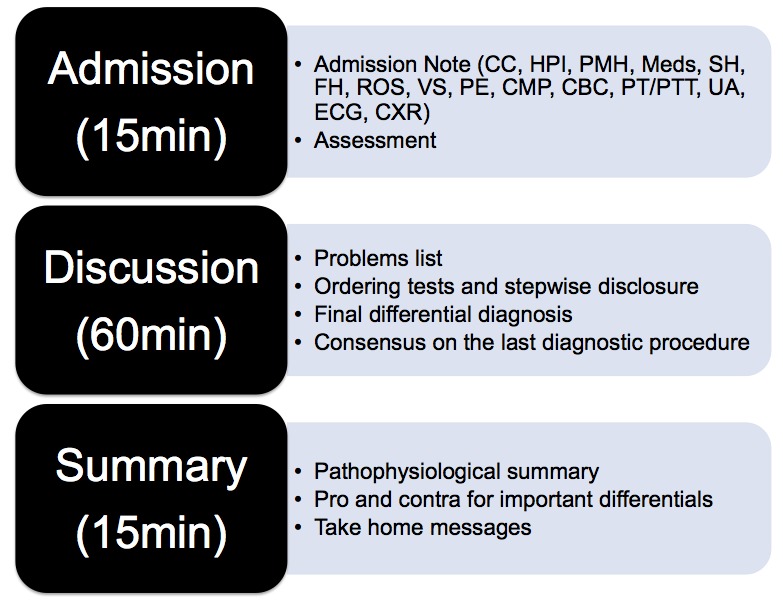

Learning outcomes with respect to clinical reasoning were measured with a knowledge application test that consisted of 29 items (ie, a maximum of 29 points could be achieved) and was to be filled out within 45 min. The knowledge application test was based on instruments previously developed at the Institute for Medical Education at LMU Munich.27–29 It comprised multiple choice items, key feature problems and problem-solving tasks, addressing the conceptual, strategic and conditional knowledge of the participants (see figure 3). Meta-analyses on retest effects suggest that score increase is higher for identical forms than for parallel test forms.30 In order to limit such effects, we applied parallel forms of the knowledge application test for premeasurement and postmeasurement (ie, topics covered by the individual items were the same, but the items were reformulated and their order was permutated). Overall test difficulty was chosen to be high in order to avoid ceiling effects, as students from all clinical years were allowed to participate in the study. Overall test reliability was satisfactory (Cronbach’s α=0.71).

Figure 3.

Knowledge application test. Exemplary items are shown for each of the knowledge types addressed (arrows point to the correct answers). The test included 11 items on conceptual knowledge, nine items on strategic knowledge and nine items on conditional knowledge. BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; EMS, emergency medical service; HR, heart rate; PE, physical examination; RR, respiratory rate; SpO2, oxygen saturation; T, temperature;

Subjective learning outcomes were measured at T_1 with a short questionnaire consisting of nine items (eg, ‘I learnt a lot during the CCD course’, ‘The CCD course increased my learning motivation’ or ‘I recommend the implementation of the CCD teaching format into the curriculum’; the full questionnaire is available as an online supplementary file). Participants were asked to rate these items on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (I don’t agree) to 5 (I fully agree). Reliability of the corresponding scale was good (Cronbach’s α=0.95). Additionally, study participants were asked to share their views on positive and negative aspects of the respective training format through open items at the end of the questionnaire.

bmjopen-2018-025973supp001.pdf (58.9KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

The required sample size (N=128) was estimated to detect medium effect sizes with a power of 80% and a significance level of α=0.05. For between-group analyses, one-way analyses of variances were conducted with post hoc Bonferroni tests for multiple comparisons.

Results

Effects of the CCD format on learning outcomes related to clinical reasoning

Experimental groups differed significantly with respect to the knowledge application post-test (see table 1), F(2,87)=27.07, p<0.001, partial η2=0.384. The Live-CCD group (M=14.10; SD=3.32) outperformed both the Video-CCD (M=11.69; SD=3.34) and the Paper-Cases group (M=8.50; SD=2.44). Post hoc Bonferroni tests revealed significant differences between Live-CCD and Video-CCD (p=0.011) as well as the Paper-Cases group (p<0.001). The difference in the knowledge application post-test between Video-CCD and the Paper-Cases group was also significant (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Overview of the findings of the study

| Teaching format | |||

| Live-CCD | Video-CCD | Paper-Cases | |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Knowledge application pre-test | 5.34 (1.92) | 4.76 (1.90) | 5.76 (2.24) |

| n=30 | n=27 | n=33 | |

| Knowledge application post-test | 14.10 (3.32) | 11.69 (3.34) | 8.50 (2.44) |

| n=30 | n=27 | n=33 | |

| Delayed knowledge application post-test | 13.36 (3.23) | 11.84 (2.92) | 7.89 (2.41) |

| n=30 | n=27 | n=33 | |

| Subjective learning outcomes | 4.20 (0.63) | 3.18 (1.24) | 3.00 (0.99) |

| n=30 | n=27 | n=31 | |

CCD, clinical case discussion.

Two weeks after course completion, the effect of the teaching format was still found in a delayed knowledge application post-test, F(2,87)=30.91, p<0.001, partial η2=0.415. Both Live-CCD (M=13.36; SD=3.23) and Video-CCD (M=11.84; SD=2.92) outperformed the Paper-Cases group (M=7.89; SD=2.41). Post hoc Bonferroni tests revealed significant differences between the Live-CCD and Paper-Cases group (p<0.001) as well as between the Video-CCD and Paper-Cases group (p<0.001). However, the difference between Live-CCD and Video-CCD was not significant in the delayed knowledge application post-test (p=0.146).

Effects of the CCD format on subjective learning outcomes

Experimental groups differed significantly with respect to subjective learning outcomes (see table 1), F(2,85)=13.16, p<0.001, partial η2=0.236. Participants of the Live-CCD group (M=4.20; SD=0.63) assigned better ratings to their course format than participants in the Video-CCD group (M=3.18; SD=1.24) and the Paper-Cases group (M=3.00; SD=0.99). Post hoc Bonferroni tests showed that the Live-CCD differed from the Video-CCD (p=0.001) and the Paper-Cases group (p<0.001) in this regard. An additional Duncan post hoc test confirmed that the Video-CCD and the Paper-Cases group did not differ from each other in this regard (p=0.48).

To investigate the relations between the subjective assessment and the knowledge application tests applied at the end and 2 weeks after the course, we calculated correlations between the different outcome measures. Subjective learning outcomes correlated on a medium level with both the knowledge application post-test (r=0.343, n=88, p=0.001) and the delayed knowledge application post-test (r=0.339, n=88, p=0.001).

In the Live-CCD group, 83% of the students were in favour of implementing routine Live-CCD into the medical curriculum. Only 45% and 31% of students from the Video-CCD and Paper-Cases groups voted for an implementation of their respective course in the curriculum. With respect to the open items from the subjective learning outcomes questionnaire, participants from all groups praised the quality of the cases. Participants from the Live-CCD group particularly valued their course format for providing an opportunity to practice ‘diagnostic thinking’ and the ‘focus on practice elements’. They also mentioned that ‘you can look up theoretical knowledge, but you cannot look up applied knowledge’. Students in the Video-CCD group, on the other hand, praised features of the digital learning environment as they could ‘pause, reflect or quickly do a Google search’ when watching the case discussions. However, they also criticised it was not possible for them to ‘participate in a more active way’.

Discussion

This randomised controlled study shows that even relatively short CCD interventions can lead to improved and sustainable learning outcomes with respect to clinical reasoning. This provides evidence that the CCD approach, which is based on CPCs, is an effective teaching resource to foster clinical reasoning skills in medical students. We had hypothesised that a more interactive course format would result in an improvement of clinical reasoning skills when compared with less interactive formats. Results show that the Live-CCD indeed leads to the highest learning outcomes in medical students compared with less interactive formats. Consistent with our hypothesis, clinical reasoning skills, as measured with our knowledge application test, had the highest gain in the Live-CCD group. These positive effects of the CCD teaching format on clinical reasoning skills proved sustainable as shown by the results in the delayed knowledge application post-test. Overall, these results are in line with a recently published study on diagnostic reasoning31 where students who worked in pairs were more accurate in their diagnosis than individual students despite having comparable knowledge. Collaborative clinical reasoning has thus far been under-represented in the literature and yet, seems to solve many of the educational problems regarding diagnostic errors.32

The significant difference between the Live-CCD and the Video-CCD group can be explained by the findings of a meta-analysis that showed technology-assisted single-person learning to be inferior to group learning because of the decreased social interaction.33 However, it is important to note that 2 weeks after the course, participants of the Live-CCD and Video-CCD groups did not differ significantly anymore while both groups still clearly outperformed the Paper-Cases group. In other words, watching a video of the live case discussion was found to be more beneficial for learners regarding their clinical reasoning skills than just reading the printed cases. We cannot rule out that Live-CCD and Video-CCD groups did not differ in the delayed knowledge application post-test due to underpowering of the study. As our trial was not designed to detect smaller effect sizes, this finding has to be treated with caution. Subjective learning outcomes suggest that students prefer the live discussion over the other formats. The subjective assessment correlated with the students’ performance in both knowledge application post-tests. Additional qualitative data from the open item answers suggests that the Live-CCD format supported students in performing clinical reasoning and that the active discussion of cases was particularly valued by the students.

Generalisability

The conclusions of this study are applicable to a broader audience of medical students. The CCD approach and its respective formats can easily be implemented in routine medical education. Peer teaching courses hold the promise of being more easy to install and more easy to staff than courses led by faculty. Of course, Live-CCDs still come with certain personnel requirements, as faculty as well as a moderator need to be present. Extensive preparation was not necessary for the clinicians involved though as they served as facilitators and provided guidance only in situations when they were explicitly asked for their clinical judgement or when they felt that the discussion went astray. Total time requirements might still be lower compared with other teaching formats. Likewise, the implementation of a singular 2-day training for moderators should not require extensive resources. The study population consisting of students with heterogeneous levels of clinical experience implies that the CCD is an effective teaching format not only for students at the beginning of their clinical career but also for intermediate students. Generalisability is potentially limited as only students from one medical school participated in our study.

Limitations of the study

There are certain limitations of this study that have to be addressed. One important limitation is the single-centre nature of this study and the relatively small sample size. Before the CCD approach can be implemented on a larger scale, a validation of our findings is therefore required. Caution is clearly warranted with the effect sizes shown in this trial, as it has been shown that effect sizes of learning intervention trials tend to be inflated compared with the effectiveness of the intervention when used in routine education.34 Since we did not limit the time students had to work on the cases, we cannot entirely rule out that less time was spent on task in the single-learner formats and particularly the Paper-Cases group. Against this backdrop, we suggest replication to further validate the results found in this study and strengthen the outlined implications. The knowledge application test utilised in this study did not allow for a more in-depth analysis of clinical reasoning skills (ie, a distinction of conceptual, strategic and conditional knowledge). Larger item numbers could facilitate a reliable assessment of changes on the level of corresponding subscales. Finally, we cannot relate the underlying reasoning process with the measured knowledge gains. Further studies on clinical reasoning processes of individuals and groups are methodologically challenging but urgently needed for the advancement of a model of clinical reasoning and for improving teaching clinical reasoning.35

Future research questions

Based on our findings, the CCD approach is a useful asset for medical educators to widen the range of clinical reasoning teaching tools. Live-CCD can thus be seen as a prime candidate for routine implementation in clinical reasoning curricula. Future research should aim to identify which Live-CCD elements (roles, case contents or course structure) contribute in which way to the improvement of clinical reasoning skills in medical students. The question if and to what extent such skills are applicable across domains is currently being discussed.36 Future studies may also address the issue of transfer (ie, to what extent can clinical reasoning skills obtained in case-based training later be applied to different cases?).37 Regarding the Video-CCD, means of instructional support to increase the effectiveness and interactivity of the video-based format should be investigated in an attempt to exploit its full potential.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Johanna Huber and her team for technical support with the evaluation, Thomas Brendel and Thomas Bischoff for help with the video production and Mark S Pecker for critical reading of our manuscript and valuable suggestions. The authors also thank the CCD student discussants and moderators for their contributions. We wish to sincerely address our gratitude to the CCD team for organisational support with the study: Nora Koenemann, Simone Reichert, Sandra Petrenz, Fabian Haak, Bjoern Stolte, Simon Berhe, Bastian Brandt and Thomas Lautz. Marc Weidenbusch wishes to express special thanks to Bernd Gansbacher for introduction to CCDs.

Footnotes

Contributors: MW, BL, MRF and JMZ planned the study. MW, BL and CS were responsible for data acquisition. MW, BL, MS, RK, JK, MRF and JMZ analysed and interpreted the data. MW, BL and JMZ drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the significant intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant no. 01PL12016) and an intramural grant of the Medical Faculty of the University of Munich (Lehre@LMU).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. . Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach 2010;32:638–45. 10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fischer MR, Bauer D, Mohn K, et al. . Finally finished! National competence based catalogues of learning objectives for undergraduate medical education (NKLM) and dental education (NKLZ) ready for trial. GMS Z Med Ausbild 2015;32:Doc35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harasym PH, Tsai T-C, Hemmati P. Current trends in developing medical students' critical thinking abilities. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2008;24:341–55. 10.1016/S1607-551X(08)70131-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Donaldson MS, Corrigan JM, Kohn LT. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington: National Academies Press, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kassirer JP. Teaching clinical medicine by iterative hypothesis testing. Let's preach what we practice. N Engl J Med 1983;309:921–3. 10.1056/NEJM198310133091511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hege I, Kopp V, Adler M, et al. . Experiences with different integration strategies of case-based e-learning. Med Teach 2007;29:791–7. 10.1080/01421590701589193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cannon WB. The case method of teaching systematic medicine. Boston Med Surg J 1900;142:31–6. 10.1056/NEJM190001111420202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eva KW. What every teacher needs to know about clinical Reasoning. Med Educ 2005;39:98–106. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01972.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harris NL. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital– continuing to learn from the patient. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2252–4. 10.1056/NEJMe030079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cabot RC. Case teaching in medicine: a series of graduated exercises in the differential diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of actual cases of disease. Boston: Heath, 1906. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sturdy S. Knowing cases: biomedicine in Edinburgh, 1887-1920. Social Studies of Science 2007;37:659–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Relman AS. Two views. N Engl J Med 1979;301:1112–3. 10.1056/NEJM197911153012009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ertmer PA, Newby TJ. Behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism: comparing critical features from an instructional design perspective. Performance Improvement Quarterly 1993;6:50–72. 10.1111/j.1937-8327.1993.tb00605.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Merseth KK. Cases and case methods in teacher education : Sikula J, Buttery TJ, Guyton R, Handbook of research on teacher education. 2nd ed New York, NY: Macmillan, 1996: p. 722–744. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zottmann JM, Stegmann K, Strijbos J-W, et al. . Computer-supported collaborative learning with digital video cases in teacher education: the impact of teaching experience on knowledge convergence. Comput Human Behav 2013;29:2100–8. 10.1016/j.chb.2013.04.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Powers BW, Navathe AS, Jain SH. Medical education's authenticity problem. BMJ 2014;348:g2651 10.1136/bmj.g2651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chi MTH, Wylie R. The ICAP framework: linking cognitive engagement to active learning outcomes. Educational Psychologist 2014;49:219–43. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duncan RG, Rivet AE. Science learning progressions. Science 2013;339:396–7. 10.1126/science.1228692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Menezes S, Premnath D. Near-peer education: a novel teaching program. Int J Med Educ 2016;7:160–7. 10.5116/ijme.5738.3c28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ince-Cushman D, Rudkin T, Rosenberg E. Supervised near-peer clinical teaching in the ambulatory clinic: an exploratory study of family medicine residents' perspectives. Perspect Med Educ 2015;4:8–13. 10.1007/s40037-015-0158-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chi MTH. Active-constructive-interactive: a conceptual framework for differentiating learning activities. Top Cogn Sci 2009;1:73–105. 10.1111/j.1756-8765.2008.01005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ruiz JG, Mintzer MJ, Leipzig RM. The impact of e-learning in medical education. Acad Med 2006;81:207–12. 10.1097/00001888-200603000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miller DC, Salkind NJ. Handbook of research design and social measurement. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kotton DN, Muse VV, Nishino M. Case 2-2012. N Engl J Med 2012;366:259–69. 10.1056/NEJMcpc1109274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marks PW, Zukerberg LR. Case 30-2004. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1333–41. 10.1056/NEJMcpc040921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Uyeki TM, Sharma A, Branda JA. Case 40-2009. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2558–69. 10.1056/NEJMcpc0905545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Braun LT, Zottmann JM, Adolf C, et al. . Representation scaffolds improve diagnostic efficiency in medical students. Med Educ 2017;51:1118–26. 10.1111/medu.13355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kopp V, Stark R, Kühne-Eversmann L, et al. . Do worked examples foster medical students' diagnostic knowledge of hyperthyroidism? Med Educ 2009;43:1210–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03531.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schmidmaier R, Eiber S, Ebersbach R, et al. . Learning the facts in medical school is not enough: which factors predict successful application of procedural knowledge in a laboratory setting? BMC Med Educ 2013;13:28 10.1186/1472-6920-13-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hausknecht JP, Halpert JA, Di Paolo NT, et al. . Retesting in selection: a meta-analysis of coaching and practice effects for tests of cognitive ability. J Appl Psychol 2007;92:373–85. 10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hautz WE, Kämmer JE, Schauber SK, et al. . Diagnostic performance by medical students working individually or in teams. JAMA 2015;313:303–4. 10.1001/jama.2014.15770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schmidt HG, Mamede S. How to improve the teaching of clinical Reasoning: a narrative review and a proposal. Med Educ 2015;49:961–73. 10.1111/medu.12775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lou Y, Abrami PC, d’Apollonia S. Small group and individual learning with technology: a meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res 2001;71:449–521. 10.3102/00346543071003449 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Springer L, Stanne ME, Donovan SS. Effects of small-group learning on undergraduates in science, mathematics, engineering, and technology: a meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res 1999;69:21–51. 10.3102/00346543069001021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heitzmann N, Fischer MR, Fischer F. Towards more systematic and better theorised research on simulations. Med Educ 2017;51:129–31. 10.1111/medu.13239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fischer F, Chinn C, Engelmann K. Scientific Reasoning and argumentation. The roles of general and specific knowledge. New York, NY: Routledge, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Keemink Y, Custers EJFM, van Dijk S, et al. . Illness script development in pre-clinical education through case-based clinical reasoning training. Int J Med Educ 2018;9:35–41. 10.5116/ijme.5a5b.24a9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025973supp001.pdf (58.9KB, pdf)