Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study is to characterise concurrent use of benzodiazepine receptor modulators and opioids among prescription opioid users in Alberta in 2017.

Design

A population based retrospective study.

Setting

Alberta, Canada, in the year 2017.

Participants

All individuals in Alberta, Canada, with at least one dispensation record from a community pharmacy for an opioid in the year 2017.

Exposure

Concurrent use of a benzodiazepine receptor modulator and opioid, defined as overlap of supply for both drugs for at least 1 day.

Main outcome measures

Prevalence of concurrency was estimated among subgroups of patient characteristics that were considered clinically relevant or associated with inappropriate medication use.

Results

Among the 547 709 Albertans who were dispensed opioid prescriptions in 2017, 132 156 (24%) also received prescriptions for benzodiazepine receptor modulators. There were 96 581 (17.6%) prescription opioid users who concurrently used benzodiazepine receptor modulators with an average of 98 days (SD=114, 95% CI 97 to 99) of total cumulative concurrency and a median of 37 days (IQR 10 to 171). The average longest duration of consecutive days of concurrency was 45 (SD=60, 95% CI 44.6 to 45.4) with a median of 24 days (IQR 8 to 59). Concurrency was more prevalent in females, patients using an average daily oral morphine equivalent >90 mg, opioid dependence therapy patients, chronic opioid users, patients utilising a high number of unique providers, lower median household incomes and those older than 65 (p value<0.001 for all comparisons).

Conclusions

Concurrent prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepine receptor modulators is common in Alberta despite the ongoing guidance of many clinical resources. Older patients, those taking higher doses of opioids, and for longer durations may be at particular risk of adverse outcomes and may be worthy of closer follow-up for assessment for dose tapering or discontinuations. As well, those with higher healthcare utilisation (seeking multiple providers) should also be closely monitored. Continued surveillance of concurrent use of these medications is warranted to ensure that safe drug use recommendations are being followed by health providers.

Keywords: opioids, benzodiazepines, concurrent use, PUBLIC HEALTH, concurrent prescribing, Z-drugs

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large population-based sample using administrative database with near complete capture of all opioid and benzodiazepine receptor modulator dispensations occurring in the community.

Analysis included prevalence of concurrency among subgroups of patient characteristics including daily oral morphine equivalents, opioid dependence treatment, duration of opioid use and number of unique providers.

This study assumed that patients took their medications as prescribed and captured in the database. This has never been validated.

This study assumed that days supply was entered correctly by pharmacies when calculating oral morphine equivalents and daily defined doses. This has never been validated.

Information on the indication for concurrent prescribing was not available from the administrative database.

Introduction

Canada has among the highest rates of opioid prescribing in the world and since 1980, the volume of opioids sold to hospitals and pharmacies has increased by 3000% despite increasing recognition of the significant prescribing risks associated with such practices, including fatal overdoses, dependency, motor vehicle collisions and falls and fractures among the elderly.1–3 Individuals older than 65 are especially prone to the consequences of opioids, with this group accounting for 63% of unintentional opioid poisonings and having the highest rate of opioid poisoning hospitalisations.3 4 A similar picture exists for benzodiazepines and Z-drugs (zopiclone and zolpidem), collectively known as benzodiazepine receptor modulators because of their effects on γ-aminobutyric acid receptors.5 6 Benzodiazepine receptor modulators are one of the most widely prescribed psychotropic compounds for anxiety disorders and insomnia.7 Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety disorders and insomnia suggest that benzodiazepine receptor modulator treatment is appropriate for short-term use in adults (aged 20to 64) and in some cases as second-line treatment.8 9 Use of benzodiazepine receptor modulators outside of these recommendations is considered ‘potentially inappropriate’ given the potential for adverse effects, especially in those over 65.7 8 10 For example, the risk of motor vehicle accidents, falls and hip fractures leading to hospitalisation and death can more than double in older adults taking benzodiazepines.11 A 2006 study in British Columbia found that 3.5% of the population were considered ‘long-term’ users of benzodiazepines and 47% were over the age of 65.12 Furthermore, a recent study reported that 10% of Albertans in 2015 received a benzodiazepine with the prevalence of use increasing with age.13

Given the similar concerns with prescribing and associated adverse outcomes, concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepine receptor modulators is strongly discouraged for most patients.1 14 15 Other studies have evaluated the characteristics of concurrent use. One American study found that concurrency was more common in chronic opioid users, women and the elderly.16 However, this study did not stratify concurrent use by daily oral morphine equivalents. Two other studies using data from the USA further described a rising trend in concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepine receptor modulators.17 18 No studies were found that used Canadian data. There are no specific clinical guidelines on indications for concurrent use of these medications and in fact, expert perspectives warn that opioids and benzodiazepines should very rarely be prescribed together.1 14 19 Furthermore, studies and safe medication use guidelines have identified concurrent use of these medications as a risk factor for fatal opioid overdose.3 14 In Canada, national and provincial initiatives have aimed at reducing inappropriate opioid and benzodiazepine prescribing, as well as decreasing the potential for harm.1 14 15

Alberta has implemented procedures around the individual prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepine receptor modulators. Both of these medication classes have been actively monitored in Alberta since 1986 through the Triplicate Prescription Program (TPP), a prescription drug monitoring programme in which prescribers must register with in order to prescribe a TPP medication. However, previous literature suggests that benzodiazepine receptor modulators and opioids cannot be targeted by safe use policies in isolation.20 There is very little published data on concurrent use, and none in Alberta, Canada. Thus, the objective of this study is to expand our understanding of concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepine receptor modulators by characterising the prevalence of concurrent use among opioid users using administrative data from the province of Alberta in 2017.

Methods

Study population

This study included all individuals in Alberta with at least one dispensation record from community pharmacies for an opioid between 1 January, 2017, to 31 December, 2017.

Data sources

Data from Alberta Netcare’s Pharmaceutical Information Network (PIN) was used for this study. PIN data includes >95% of all dispensations from community pharmacies in Alberta irrespective of insurance coverage, thus providing comprehensive data on all medication dispensations (from all prescriber types) occurring in the province outside of the hospital setting.21 Information on dispensed medication (drug identification number, dispense date, days supply, quantity, strength, name, directions), patient (age, sex, unique patient identifier) and prescriber (type and license number) was available. The validity of the days supply variable for each dispensation was evaluated to ensure it fell within a plausible clinical range based on the defined daily dose for a single dispensation; less than 0.01% of the days supply values were deemed to be outside of this range and a new days supply was imputed based on an individual’s historical average for a particular ingredient. All unique identifiers (patient, prescriber) were anonymised for the purposes of this analysis which was approved by the health ethics research board at the University of Alberta (#Pro00083807).

Study measures

All opioid and benzodiazepine receptor modulator dispensations were retrieved from PIN for 2017. An opioid user was defined as anyone who received at least one dispensation for an opioid. Patient characteristics considered in other studies,16–18 as well as any additional clinically relevant characteristics available in the administrative databases were examined to identify factors associated with concurrent use. Chronic opioid use was defined as total opioid days greater than 90, as others have,1 or more than 10 opioid dispensations in 1 year. An opioid dependence treatment (ODT) user was anyone that was dispensed a prescription for methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone. Postal codes (forward sortation index) were used to categorise individuals as rural/urban and into income categories (<50 k, 50 to 75 k, 75 to 100 k, 100 to 125 k, >125 k). Average daily oral morphine equivalents (OME’s) and number of daily defined doses (DDDs) were calculated for all opioids and benzodiazepine receptor modulators, respectively, using the conversion factors specified by the TPP.22 Methadone and buprenorphine were excluded from OME specific analyses. We used daily OME thresholds of <50, 50 to 90 and >90 as categories in our analyses since these are clinically accepted in the guidelines for determining the risk/benefit profile when prescribing opioids for pain.14

The key variable of interest was whether an opioid user also used a benzodiazepine receptor modulator concurrently in 2017. Although we were not able to directly observe utilisation of these medications by individuals, we considered ‘use’ as any day on which an individual had a supply of medication on hand based on the date and days supply of each dispensation. Using the dispensation information from PIN, we generated binary variables for each day of the year to indicate if it was ‘covered’ by an opioid or benzodiazepine receptor modulator. Beginning on the dispensation day, each day was categorised as covered until the end of the days supplied. For each patient, a day was categorised as concurrent if it was covered by both an opioid and benzodiazepine receptor modulator. We then calculated the number of days, both cumulative and consecutive, that were categorised as concurrent. For example, if a patient received a 30-day opioid dispensation on January 1st and a 20-day benzodiazepine receptor modulator dispensation on January 20th, this would be quantified as 11 days of concurrent use. In our main analyses, concurrency was defined as having one or more days categorised as concurrent.

Statistical analyses

We conducted a descriptive analysis to examine the characteristics of concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepine receptor modulators. All summary statistics were calculated using the denominator of total population of opioid users in Alberta for 2017.

The measure of interest was prevalence of concurrent use by age, sex, average daily OME thresholds (<50, 50 to 90, >90), duration of opioid use (chronic (as defined previously) vs intermittent), ODT, rural versus urban residence, number of unique providers, median annual household income thresholds and number of DDD’s of benzodiazepine receptor modulators. Analyses were also stratified by the total days of cumulative concurrency (1 to 7, 8 to 30, 31 to 90, >90) and consecutive days of concurrency (1 to 7, 8 to 30, 31 to 60, 61 to 90, >90). We used X2 tests of independence to compare prevalence proportions between the different groups in the above-named characteristics. All analyses were performed using STATA/MP 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants.

Results

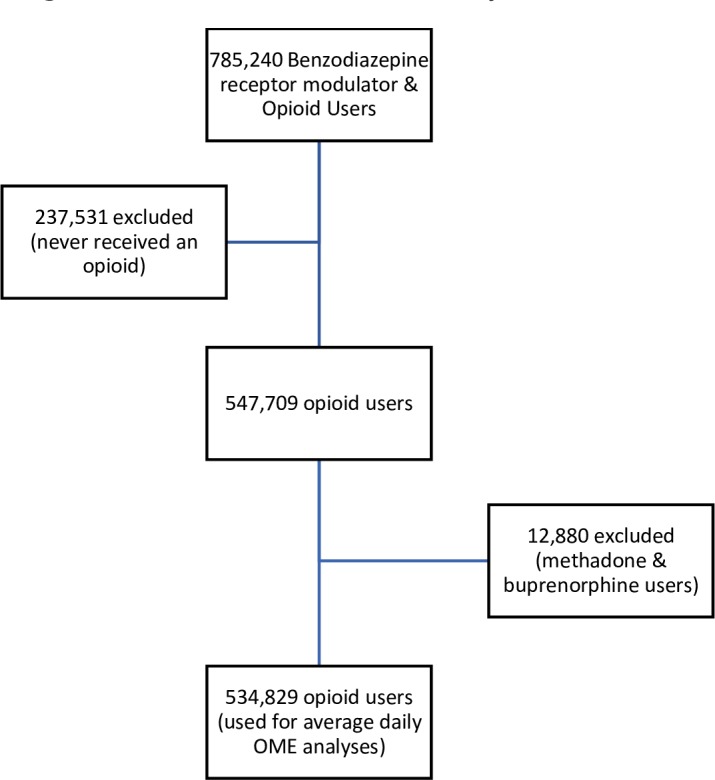

There were 547 709 Albertans who received at least one dispensation for an opioid and qualified as an opioid user (figure 1). Females represented 53% (n=292 396) of opioid users, 18% (n=98 083) were over the age of 65 and the majority of patients were from urban areas (84%) (table 1). Overall, 20% (n=108 604) of opioid users were considered chronic users and ODT patients represented 1.7% (n=9139) of opioid users. When methadone and buprenorphine were excluded, 88% (n=468 863), 9.5% (n=51 033) and 2.8% (n=14 933) represented those in the <50, 50 to 90 and >90 OME categories, respectively. A substantial number of patients received opioids from three or more pharmacies (7%) or from three or more prescribers (16%).

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram of denominator used for analyses. OME, oral morphine equivalent.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of prevalence of concurrency* among opioid users and possible high-risk markers.

| Characteristic (among opioid users) | N (%) | Prevalence of concurrency within characteristic. Percent (n)† | Prevalence of concurrency among all opioid users. Percent (n=547 709) | Percent of concurrent users (n) |

| Opioid users | 547 709 (100) | 17.6 (96 581)‡ | --- | --- |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 255 293 (46.6) | 14.9 (37 955) | 6.9 | 39.3 (37 955) |

| Female | 292 396 (53.4) | 20.0 (58 620) | 10.7 | 60.7 (58 620) |

| Average daily OME§ | ||||

| <50 | 468 863 (87.7) | 15.7 (73 411) | 13.7 | 80.2 (73 411) |

| 50-90 | 51 033 (9.5) | 22.1 (11 287) | 2.1 | 12.3 (11 287) |

| >90 | 14 933 (2.8) | 46.2 (6899) | 1.3 | 7.5 (6899) |

| Duration of opioid use¶ | ||||

| Chronic | 108 604 (19.8) | 47.1 (51 214) | 9.4 | 53.0 (51 214) |

| Intermittent | 439 105 (80.2) | 10.3 (45 367) | 8.3 | 47.0 (45 367) |

| ODT | 9139 (1.7) | 37.2 (3401) | 0.62 | 3.5 (3401) |

| Not on ODT | 538 570 (98.3) | 17.3 (93 180) | 17.1 | 96.5 (93 180) |

| Postal code zone | ||||

| Rural | 85 666 (15.6) | 22.0 (18 809) | 3.4 | 19.5 (18 809) |

| Urban | 462 043 (84.4) | 16.8 (77 772) | 14.2 | 80.5 (77 772) |

| Median household income (x1000) | ||||

| <50 | 107 240 (19.6) | 23.1 (24 781) | 4.5 | 25.7 (24 781) |

| 50-75 | 261 354 (47.2) | 17.9 (46 725) | 8.5 | 48.4 (46 725) |

| 75-100 | 151 352 (27.6) | 14.2 (21 496) | 3.9 | 22.3 (21 496) |

| 100-125 | 27 314 (5.0) | 12.9 (3514) | 0.6 | 3.6 (3514) |

| >125 | 448 (0.08) | 14.5 (65) | 0.01 | 0.07 (65) |

| # of unique dispensing pharmacies | ||||

| 1 | 426 557 (77.9) | 12.0 (51 413) | 9.4 | 53.2 (51 413) |

| 2 | 82 048 (15.0) | 31.1 (25 550) | 4.7 | 26.4 (25 550) |

| 3 | 23 155 (4.2) | 45.3 (10 482) | 1.9 | 11.0 (10 482) |

| 4 | 8260 (1.5) | 53.1 (4387) | 0.8 | 4.5 (4387) |

| 5+ | 7689 (1.4) | 61.8 (4749) | 0.88 | 4.9 (4749) |

| # of unique prescribers | ||||

| 1 | 352 596 (64.4) | 7.1 (25 158) | 4.6 | 26.0 (25 158) |

| 2 | 107 347 (19.6) | 25.9 (27 805) | 5.1 | 28.8 (27 805) |

| 3 | 42 656 (7.8) | 42.2 (17 990) | 3.3 | 18.6 (17 990) |

| 4 | 20 126 (3.7) | 50.5 (10 163) | 1.9 | 10.5 (10 163) |

| 5+ | 24 984 (4.6) | 61.9 (15 465) | 2.8 | 16.0 (15 465) |

| Age | ||||

| 0-17 | 20 366 (3.7) | 1.5 (307) | 0.06 | 0.3 (307) |

| 18-65 | 429 259 (78.4) | 16.3 (70 000) | 12.8 | 72.5 (70 000) |

| >65 | 98 083 (17.9) | 26.8 (26 274) | 4.8 | 27.2 (26 274) |

| Number of benzodiazepine DDD’s | ||||

| 0-1 | 94 192 (71.3) | 67.4 (63 531) | 11.6 | 65.8 (63 531) |

| 1-2 | 30 423 (23.0) | 86.7 (26 370) | 4.8 | 27.3 (26 370) |

| 2-3 | 4761 (3.6) | 89.1 (4243) | 0.77 | 4.4 (4243) |

| >3 | 2780 (2.1) | 87.7 (2437) | 0.44 | 2.5 (2437) |

*Concurrency is defined as one or more days of overlap between an opioid and benzodiazepine receptor modulator.

†P value for X2 test of independence (difference between prevalence of concurrency between groups within characteristic) <0.001 for all characteristics.

‡95% CI for prevalence of concurrency=17.5 to 17.7.

§Methadone and buprenorphine patients were excluded.

¶Chronic opioid users were defined by having at least 90 days of cumulative opioid use or at least 10 opioid prescriptions in the year. This includes ODT patients.

DDD, daily defined doses; ODT, opioid dependence treatment; OME, oral morphine equivalent.

Among the 547 709 opioid users, 24% (n=132 156) received a benzodiazepine receptor modulator and 17.6% (n=96 581) had at least 1 day of concurrent use of an opioid and a benzodiazepine receptor modulator during 2017. The mean total days of concurrency over the entire year was 98 (SD=114) days (median of 37 (IQR 10 to 171)). Among patients with concurrent use, a substantial number had high durations of concurrent use during the year; 53% had over 30 days of concurrency and 36% had over 90 days of concurrency (table 2). When we examined the duration of consecutive days of concurrency, the mean longest duration was 45 (SD=60) with a median of 24 days (IQR 8 to 59). Most concurrent patients (64%) had concurrent use for less than 30 consecutive days (table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of concurrent use (n=96 581)

| Characteristic | % |

| Total days of cumulative concurrency | |

| Mean (SD)* | 98 (114)* |

| 1–7 | 21 |

| 8–30 | 26 |

| 31–90 | 17 |

| >90 | 36 |

| Longest Duration of consecutive concurrency | |

| Mean (SD)* | 45 (60)* |

| 1–7 | 24 |

| 8–30 | 40 |

| 31–60 | 13 |

| 61–90 | 8 |

| >90 | 14 |

*Days.

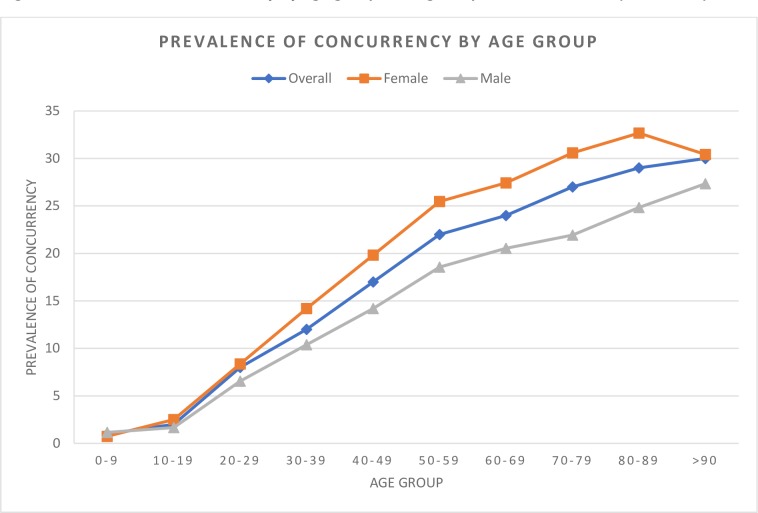

Differences in concurrency were noted based on sex, urban/rural status and median household incomes, with the prevalence of concurrency being highest among the lowest incomes, as well as a strong trend in age (table 1, figure 2). Indeed, <2% of all opioid users under the age of 20 used a benzodiazepine receptor modulator concurrently relative to nearly 30% of those over the age of 65. The highest concurrence was observed in the highest age groups, who are also most at risk of severe adverse events (table 3). Concurrency was more common in chronic opioid users compared with intermittent users (table 1). Similarly, chronic opioid users had a higher number of concurrent days in the year compared with intermittent users (table 4).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of concurrency by age group among all opioid users in 2017 (n=547 708).

Table 3.

Prevalence of concurrency by age group and total days of concurrency among opioid users (%)

| Age group | Days of concurrency | ||||

| 1–7 | 8–30 | 31–90 | >90 | Total (n=) | |

| 0– 9 | 0.76 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 1669 |

| 10– 19 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 30 551 |

| 20– 29 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 68 710 |

| 30– 39 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 92 549 |

| 40– 49 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 93 387 |

| 50– 59 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 107 917 |

| 60– 69 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 83 267 |

| 70– 79 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 10 | 43 973 |

| 80– 89 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 21 029 |

| > 90 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 4656 |

| Total (n=) | 20 503 | 25 614 | 15 940 | 34 524 | 547 708 |

Table 4.

Prevalence of concurrency by category of opioid use and total days of concurrency. (P value<0.001)

| Days of cumulative concurrency | % intermittent users (n=439 105) | % chronic users (n=108 604) |

| 1–7 | 4.1 (18 163) | 2.2 (2340) |

| 8–30 | 4.5 (19 712) | 5.4 (5902) |

| 31–90 | 1.7 (7492) | 7.8 (8448) |

| >90 | 0 (0) | 31.8 (34 524) |

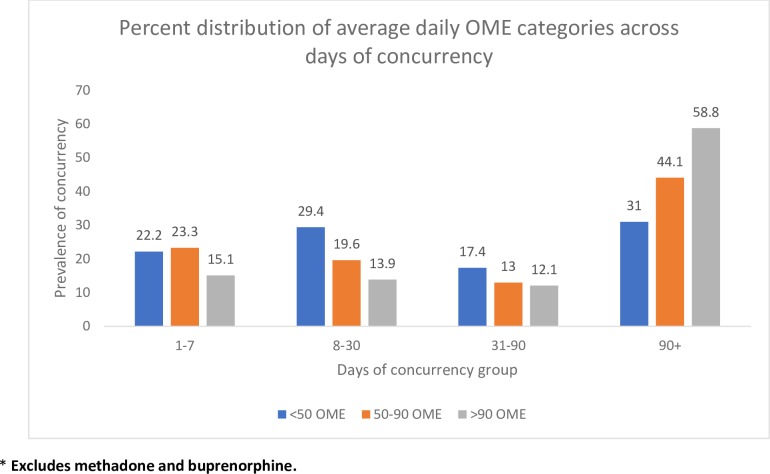

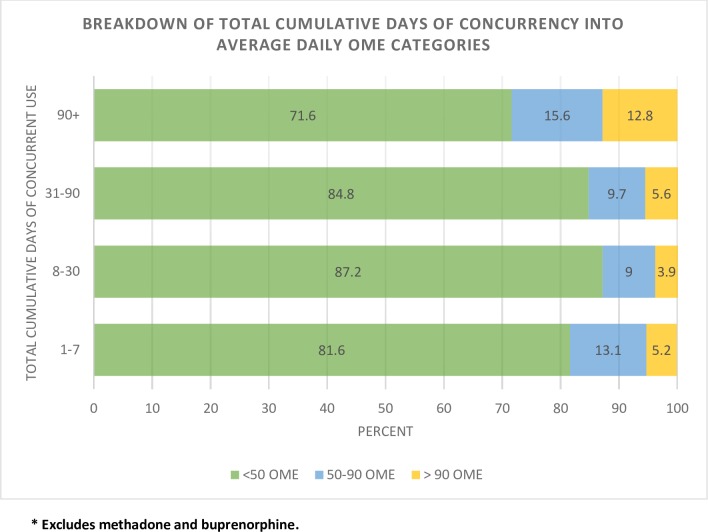

Characteristics associated with potentially inappropriate use of opioids (eg, older age, high OME’s, multiple providers) had substantially higher concurrent benzodiazepine receptor modulator use (figures 2–4, table 1). Although the absolute number of patients using an average daily OME >90 was low (2.8% of opioid users), 46% had concurrent use with a benzodiazepine receptor modulator. Among concurrent users in the >90 OME category, 58.8% had concurrent use >90 days (figure 3) and 12.8% of those with >90 days of concurrent use were also taking >90 OME per day (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of concurrency by total days of concurrency and average daily OME category in 2017 (n=91 597). OME, oral morphine equivalent.

Figure 4.

Per cent distribution of average daily OME categories within categories of total cumulative days of concurrent use (n=91 597). OME, oral morphine equivalent.

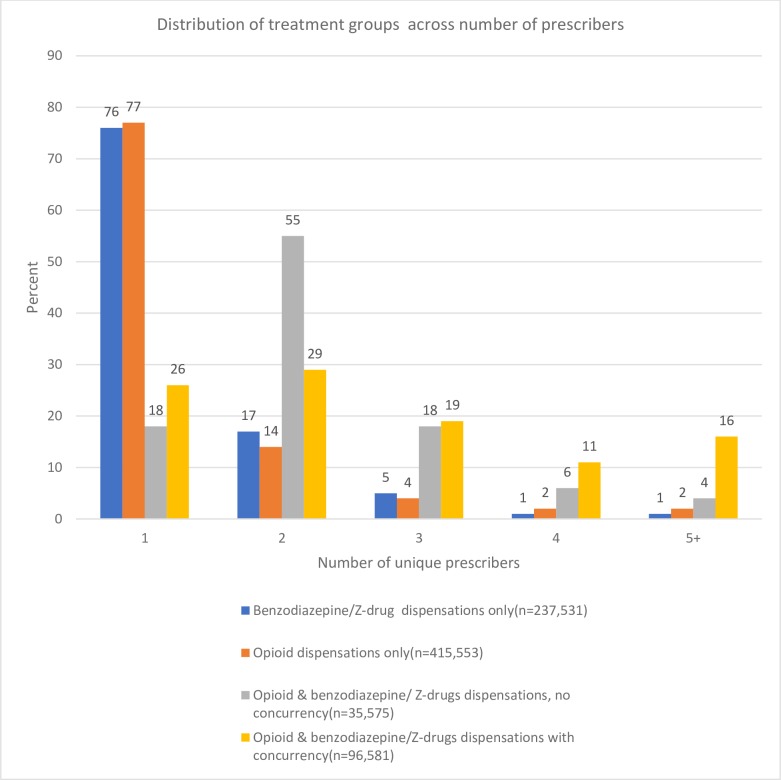

There were also clear trends with respect to providers. As the number of unique providers increased, so too did the prevalence of concurrency. Although the absolute numbers were low (<5%), the opioid users that visited more than five pharmacies or prescribers in 2017 both had a prevalence of concurrency of 62% (table 1). Opioid users who received a benzodiazepine receptor modulator, either concurrently or not, visited more providers compared with those who received only an opioid or benzodiazepine receptor modulator (figure 5). Interestingly, among concurrent users, 78% (n=74 882) received an opioid and benzodiazepine receptor modulator from the same prescriber and 94% (n=90 561) from the same pharmacy. Moreover, 58% of concurrent users (n=56 098) received an opioid and benzodiazepine receptor modulator on the same day from the same prescriber while 64% (n=61 715) received an opioid and benzodiazepine receptor modulator from the same pharmacy on the same day.

Figure 5.

Distribution (percentage) of patient categories by number of unique providers.

The trend between number of DDD’s of benzodiazepine receptor modulators and concurrency is similar to that with average daily OME’s. Most of the opioid patients concurrently used a benzodiazepine receptor modulator at the lowest number of DDD’s (66%). However, around 88% of those using >2 to 3 times the DDD were concurrent users (table 1).

Interpretation

Many reputable clinical resources indicate that benzodiazepine receptor modulators should not be combined with opioids, yet this study showed that nearly 20% of patients using an opioid did so in combination with a benzodiazepine receptor modulator in Alberta.1 14 15 Those on >90 mg OME had the highest prevalence of concurrency when compared with lower doses. Moreover, among concurrent users, total days of concurrency was high with about half of these patients using opioids and benzodiazepine receptor modulators at the same time for more than 30 days. Perhaps not so surprising is the high prevalence of concurrency in those with a greater number of distinct prescribers. In addition, our observation of a higher prevalence of concurrency in chronic opioid users compared with intermittent users was expected since prolonged opioid use provided more opportunities for concurrent use. These results should be concerning to clinicians and policymakers because the potential for adverse outcomes associated with opioid use is greatly increased since a significant proportion of opioid fatalities involve benzodiazepine receptor modulators.3 23

Our observation that concurrent use of a benzodiazepine receptor modulator occurred in 20% to 25% of opioid users was similar to the recent Vozoris study using data from the USA.18 While both studies also found a higher prevalence of concurrency in females than males, this difference was not significant after adjusting for covariates in the Vozoris study. One reason for this discrepancy may be the underlying patterns of benzodiazepine receptor modulator use; in Canada, these drugs are used more frequently in females than males.24 Our observations that concurrency increased with age and was prevalent in nearly 30% of opioid users >65 years of age contrasts with previous studies. For example, Vozoris reported a trend towards decreased concurrency among patients 60 years and older,18 and Hwang and colleagues reported concurrency in <20% of elderly patients.16 Possible reasons for the discrepancy in age-related trends include differences in study methodology (survey data vs administrative data), study population (increasing use of benzodiazepine receptor modulators among the elderly in Canada and Alberta24–26), our inclusion of Z-drugs to identify benzodiazepine receptor modulators and prescriber perception of safety of Z-drugs over benzodiazepines.27 Regardless, the high prevalence of concurrent use among those over 65 is especially concerning because they are at high-risk for adverse clinical outcomes. Indeed, many clinical guidelines advise against prescribing benzodiazepines in most seniors, let alone in combination with an opioid.28 29 Furthermore, patients aged 65 and older consistently have the highest rates of hospitalisation due to opioid poisoning.4

To date, we are unaware of other studies that have suggested those taking very high daily doses of opioids (>90 OME per day) also have high concurrency rates. Irrespective of the reason for concurrent use (ie, opioid use disorder and doctor shopping or when used for more appropriate indications) the evidence suggests that high dose opioid users have up to five times the risk of overdose and those above 100 OME have a much higher risk of fatal over dose.14 30 Combining opioids and benzodiazepine receptor modulators in these groups could certainly contribute to further adverse outcomes already at high rates.

Although concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepine receptor modulators is often deemed clinically inappropriate, beyond substance use disorder situations, one has to question why the observed prevalence is so high despite the numerous efforts across the country, and in Alberta, to mitigate this high-risk prescribing. In the groups with the highest concurrent use (females, ODT patients, chronic and high dose opioid users, elderly, etc), most, if not all, are known to have a higher prevalence of conditions related to pain and mental health.31–33 Our results showed that 78% of concurrent users received both medications from the same prescriber and 94% from the same pharmacy with over half receiving these drugs on the same day. There is an opportunity here to educate providers about the risks of concurrent use and to verify if concurrent use is truly appropriate. Furthermore, treatment emphasis in chronic pain and mental health patients is changing where opioids and benzodiazepines are no longer first-line treatment options and where integrated and multidisciplinary treatments are preferred.34 Connecting patients with these preferred treatment modalities is often difficult because of cost and time and often opioids and/or benzodiazepines are used to address the unmet needs of patients.

The strengths of our study included the large population-based sample with near complete capture of all opioid and benzodiazepine receptor modulator dispensations occurring in community pharmacies within the province. Pharmacies in Alberta are mandated by the College of Pharmacy to ensure accurate prescription records such that use of PIN data can accurately capture most, if not all, of the opioid and benzodiazepine receptor modulator dispensations and the information provided with each of these dispensations. Another strength is that our analyses included average daily OME’s when characterising concurrent use, something that we have not seen in other studies. There are, however, some limitations in our study. First, we are assuming that patients took their medications as dispensed. Medication adherence in opioid users is a challenging issue.35 We assumed that days supply was entered correctly by pharmacies when calculating our OME and DDD values, however no validation of the PIN days supply field has been completed to date. Second, our study was limited to descriptive analyses and does not provide outcomes data from concurrent use. Clinically, there are instances where concurrent use may be considered appropriate, especially in palliative care and cancer treatment settings. Information on the indications for concurrent prescribing were not available in the PIN database used for this study.

Despite these limitations, Alberta still has an alarming prevalence of concurrent use. The opioid crisis in Alberta and Canada is being driven in part, by prescription opioids.36 However, due to widespread attention to the opioid crisis, the number of opioid prescriptions and morphine milligram equivalents prescribed sharply declined in all provinces in 2016 and 2017, including Alberta.37 38 It is clear that continued efforts are required to curb the concurrent utilisation of opioids and benzodiazepine receptor modulators in the province, and elsewhere as it is unlikely Alberta is unique in this regard. Furthermore, as increasing clinical emphasis is being placed on non-pharmacological management of chronic pain and not prescribing opioids to patients with mental-health disorders, as well as ongoing monitoring and educational campaigns, we will hopefully see a decrease in concurrent use.14 15 33 39

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study is based in part on data provided by Alberta Health and was commissioned by the College of Physicians & Surgeons of Alberta (CPSA). The interpretation and conclusions contained herein are those of the researchers and do not necessarily represent the views of the Government of Alberta or CPSA. Neither the Government of Alberta nor Alberta Health expresses any opinion in relation to this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: VS, DE, SS and DLW were involved in the conception and design of the study. VS and DE analysed the data. VS and DE drafted the article. EJ, SS, FG, DLW and SS revised the article. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. DE is the guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. . Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ 2017;189:E659–66. 10.1503/cmaj.170363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guan Q, Khuu W, Martins D, et al. . Evaluating the early impacts of delisting high-strength opioids on patterns of prescribing in Ontario. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2018;38:256–62. 10.24095/hpcdp.38.6.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Belzak L, Halverson J. Evidence synthesis - The opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada 2018;38:224–33. 10.24095/hpcdp.38.6.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O'Connor S, Grywacheski V, Louie K. At-a-glance - Hospitalizations and emergency department visits due to opioid poisoning in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2018;38:244–7. 10.24095/hpcdp.38.6.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rudolph U, Möhler H. GABA-based therapeutic approaches: GABAA receptor subtype functions. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2006;6:18–23. 10.1016/j.coph.2005.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roy-Byrne PP. The GABA-benzodiazepine receptor complex: structure, function, and role in anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66(Suppl 2):14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. CPSA Clinical toolkit benzodiazepines: use and taper. CPSA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Katzman MA, Bleau P, Blier P, et al. . Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14(Suppl 1):S1 10.1186/1471-244X-14-S1-S1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Canadian Pharmacists Association RxTx, 2019. Available: https://www.e-therapeutics.ca/search

- 10. TOP T.O.P. Guideline for Adult Primary Insomnia [Internet], 2010. Available: http://www.topalbertadoctors.org/download/439/insomnia_management_guideline.pdf

- 11. ChooseWiselyCanada The Canadian Geriatrics Society has developed a list of 5 things physicians and patients should question in geriatrics [Internet]. Available: https://choosingwiselycanada.org/geriatrics/

- 12. Cunningham CM, Hanley GE, Morgan S. Patterns in the use of benzodiazepines in British Columbia: examining the impact of increasing research and guideline cautions against long-term use. Health Policy 2010;97:122–9. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weir DL, Samanani S, Gilani F, et al. . Benzodiazepine receptor agonist dispensations in Alberta: a population-based descriptive study. CMAJ Open 2018;6:E678–84. 10.9778/cmajo.20180121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. ismp Canada Essential clinical skills for opioid prescribers, 2017. Available: https://www.ismp-canada.org/download/OpioidStewardship/Opioid-Prescribing-Skills.pdf

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain, 2016. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/Guidelines_Factsheet-a.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16. Hwang CS, Kang EM, Kornegay CJ, et al. . Trends in the concomitant prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines, 2002-2014. Am J Prev Med 2016;51:151–60. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hirschtritt ME, Delucchi KL, Olfson M. Outpatient, combined use of opioid and benzodiazepine medications in the United States, 1993-2014. Prev Med Rep 2018;9:49–54. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vozoris NT. Benzodiazepine and opioid co-usage in the US population, 1999-2014: an exploratory analysis. Sleep 2019;42. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy264. [Epub ahead of print: 01 Apr 2019]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gudin JA, Mogali S, Jones JD, et al. . Risks, management, and monitoring of combination opioid, benzodiazepines, and/or alcohol use. Postgrad Med 2013;125:115–30. 10.3810/pgm.2013.07.2684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jones JD, Mogali S, Comer SD. Polydrug abuse: a review of opioid and benzodiazepine combination use. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012;125:8–18. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Government of Alberta Alberta Netcare EHR usage statistics, 2016. Available: http://www.albertanetcare.ca/Statistics.htm

- 22. College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta Ome and DDD conversion factors. Available: http://www.cpsa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/OME-and-DDD-Conversion-Factors.pdf

- 23. Sun EC, Dixit A, Humphreys K, et al. . Association between concurrent use of prescription opioids and benzodiazepines and overdose: retrospective analysis. BMJ 2017;356 10.1136/bmj.j760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kassam A, Patten SB. Canadian trends in Benzodiazepine & Zopiclone use. J Popul Therapeutic Clin Pharmacol 2006;13. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kassam A, Carter B, Patten SB. Sedative hypnotic use in Alberta. Can J Psychiatry 2006;51:287–94. 10.1177/070674370605100504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brandt J, Alessi-Severini S, Singer A, et al. . Novel measures of benzodiazepine and Z-Drug utilisation trends in a Canadian provincial adult population (2001-2016). J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol 2019;26:e22–38. 10.22374/1710-6222.26.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoffmann F. Perceptions of German GPs on benefits and risks of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. Swiss Med Wkly 2013;143:w13745 10.4414/smw.2013.13745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Farrell KP, et al. Deprescribing benzodiazepine receptor agonists 2018.

- 29. Gallagher P, O'Mahony D, O'Mahony, STOPP D. STOPP (screening tool of older persons' potentially inappropriate prescriptions): application to acutely ill elderly patients and comparison with beers' criteria. Age Ageing 2008;37:673–9. 10.1093/ageing/afn197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ismp Canada Available: navigating-opioids-11x17-canada.pdf

- 31. Pinkhasov RM, Wong J, Kashanian J, et al. . Are men shortchanged on health? perspective on health care utilization and health risk behavior in men and women in the United States. Int J Clin Pract 2010;64:475–87. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02290.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. . Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. results from the National comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994;51:8–19. 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. National Opioid Use Guideline Group (NOUGG) Canadian guidelines for safe and effective use of opioids for CNCP-Part B 2010.

- 34. Centre for Effective Practice Management of chronic non cancer pain, 2017. Available: thewellhealth.ca/cncp

- 35. Graziottin A, Gardner-Nix J, Stumpf M, et al. . Opioids: how to improve compliance and adherence. Pain Pract 2011;11:574–81. 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2011.00449.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gomes T, Khuu W, Martins D, et al. . Contributions of prescribed and non-prescribed opioids to opioid related deaths: population based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMJ 2018;362 10.1136/bmj.k3207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Abdesselam K, Dann MJ, Alwis R, et al. . At-a-glance - Opioid surveillance: monitoring and responding to the evolving crisis. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2018;38:312–6. 10.24095/hpcdp.38.9.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta Prescribing Trends. 2018, 2018. Available: http://www.cpsa.ca/physician-prescribing-practices/

- 39. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Checklist for prescribing opioids for chronic pain, 2016. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/PDO_Checklist-a.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.