Abstract

Human NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase (DT-diaphorase, NQO1) exhibits negative cooperativity towards its potent inhibitor, dicoumarol. Here, we addressed the hypothesis that the effects of the two cancer-associated polymorphisms (p.R139W and p.P187S) may be partly mediated by their effects on inhibitor binding and negative cooperativity. Dicoumarol stabilized both variants and bound with much higher affinity for p.R139W than p.P187S. Both variants exhibited negative cooperativity towards dicoumarol; in both cases, the Hill coefficient (h) was approximately 0.5 and similar to that observed with the wild-type protein. NQO1 was also inhibited by resveratrol and by nicotinamide. Inhibition of NQO1 by resveratrol was approximately 10,000-fold less strong than that observed with the structurally similar enzyme, NRH quinine oxidoreductase 2 (NQO2). The enzyme exhibited non-cooperative behaviour towards nicotinamide, whereas resveratrol induced modest negative cooperativity (h = 0.85). Nicotinamide stabilized wild-type NQO1 and p.R139W towards thermal denaturation but had no detectable effect on p.P187S. Resveratrol destabilized the wild-type enzyme and both cancer-associated variants. Our data suggest that neither polymorphism exerts its effect by changing the enzyme’s ability to exhibit negative cooperativity towards inhibitors. However, it does demonstrate that resveratrol can inhibit NQO1 in addition to this compound’s well-documented effects on NQO2. The implications of these findings for molecular pathology are discussed.

Keywords: cancer-associated polymorphism, dicoumarol, DT-diaphorase, NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase, negative cooperativity, resveratrol

Introduction

Human NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1, DT-diaphorase, EC 1.6.5.2) is an oxidoreductase flavoenzyme [1–4]. It catalyses the two-electron reduction of quinone substrates through a substituted enzyme (or “ping-pong”) mechanism where the electron donor (NAD(P)H) enters the active site, reduces the FAD cofactor by donation of two hydride ions, leaves the active site in its oxidized form (NAD+) and is replaced by the quinone substrate, which is subsequently reduced [5–7]. NQO1 is a homodimer with interlocking subunits. There are two active sites located at the dimeric interface and residues from each monomer together with the FAD cofactor form the boundaries of the active sites [8–11].

The two-electron reduction catalysed by NQO1 ensures the reduction of quinones directly to hydroquinones thereby avoiding the production of semiquinones. Semiquinones can be oxidized by molecular oxygen, resulting in the formation of superoxide (O2−•) free radicals [1,12,13]. Additionally, NQO1 directly scavenges superoxide free radicals and plays a minor role in the redox cycling of vitamin K by detoxifying vitamin K3 to the corresponding hydroquinone [14–17]. NQO1 also detoxifies benzoquinones, toxins which are produced by the metabolism of benzene and, therefore, a deficiency in NQO1 leads to increased levels of benzene-induced toxicity [18–20]. NQO1 also has roles in cancer and some neurological diseases [4]. Inhibition of the proteasome is involved in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease and NQO1 helps to protect against this inhibition by reducing the endogenous proteasome inhibitor, aminochrome, to a cyclized hydroquinone [21,22]. NQO1 has also been implicated in the regulation of oxidative stress associated with Alzheimer’s disease [23–27].

In addition to protection afforded by its catalysis, NQO1 offers further chemoprotection by binding to, and stabilizing, the tumour-suppressing proteins, p53 and p73 and also the polyamine biosynthesis pathway enzyme, ornithine decarboxylase [28–32]. In its reduced state, NQO1 regulates the ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation of the tumour-suppressor proteins by association with the 20S proteasome and with p53 and p73 [31]. NQO1 also stabilizes the short-lived component of the transcription factor AP-1, c-fos. It stabilizes newly synthesised c-fos until it complexes with c-jun to form AP-1, which in turn translocates to the nucleus [33]. The transcription factor, 4GI, is also stabilized by NQO1 [34].

Additionally, the reduction catalysed by NQO1 has been exploited in the design of anti-cancer prodrugs. Generally, the reduction of quinones to hydroquinones is detoxifying because the donation of two electrons to the quinone ensures that highly reactive semiquinones are not produced. However, there are examples of quinones (natural and synthetic) whose chemical reactivity leads to the production of cytotoxic hydroquinones, for example, synthetic quinones can be designed so that, on reduction, they lose a leaving group to yield a hydroquinone which is a reactive electrophile which can alkylate DNA [35]. Such quinones can be exploited as anti-cancer prodrugs which become active when reduced by NQO1 and its high expression in tumour cells ensures that the effects of such prodrugs is largely targeted to these cells [35–37].

NQO1 is inhibited competitively by the coumarin-derivative, dicoumarol (an anticoagulant drug) which binds in the active site [5]. It π-stacks with the isoalloxazine ring of the FAD and forms hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds with residues from both subunits [11]. Dicoumarol induces negative cooperativity in NQO1 [38–40]. Negative cooperativity is a decrease in affinity when sequential molecules of ligand bind. A redistribution of the native state ensemble of conformers occurs on binding of the first ligand molecule; in the new ensemble, the geometry of the second binding site is changed [41,42]. A conformational change which occurs on binding of the first molecule is propagated through the enzyme and causes the change in geometry at the second binding site. This requires a pathway linking the two active sites and in the case of NQO1, which has been investigated by molecular dynamics and site-directed mutagenesis experiments [39]. Glycine 150 has been identified as pivotal to information transmission since alteration to the more conformationally restricting serine largely abolished negative cooperativity towards dicoumarol [39].

Two polymorphic forms of human NQO1 have been associated with increased cancer risk: the NQO1*2 allele (rs1800566) and the NQO1*3 allele (rs1131341). These encode a proline to serine substitution at position 187 (p.P187S) and an arginine to tryptophan substitution at position 139 (p.R139W), respectively [43–45]. Arginine 139 forms part of a solvent-exposed loop located in the larger, N-terminal domain of the enzyme. Proline 187 is also located in the N-terminal domain and is part of a loop close to the surface of the protein [8]. Neither position occurs within the pathway involved in communication between the active sites that results in negative cooperativity towards dicoumarol [39]. Biochemical and biophysical studies have established that p.P187S has a much reduced affinity for FAD when compared with the wild-type protein [32,46–50]. Both cancer-associated variants have reduced overall stability compared with wild-type and p.P187S has been shown to be partially unfolded [46,47,51,52].

Here, we studied the effects of the two cancer-associated polymorphisms on dicoumarol binding and its inhibition, to address the hypothesis that the cancer-associated variants might respond differently to these inhibitors, particularly in regards to their negative cooperativity. Other potential inhibitors, resveratrol and nicotinamide, were also investigated in terms of binding, inhibition of oxidoreductase activity and ability to induce cooperativity in NQO1.

Materials and methods

NQO1 expression, purification and enzyme kinetics analysis

Hexahistidine-tagged human wild-type NQO1 and the two cancer-associated variants (p.R139W and p.P187S) were expressed in, and purified from, Escherichia coli as previously described [47]. Rates of reaction were measured using NADH or NADPH as a reducing agent and DCPIP as the second substrate [47]. Briefly, rates were measured at 37°C in Hepes-OH buffer (pH 7.3) and were obtained from the linear section at the beginning of each progress curve. Each inhibitor was added into the reaction (dicoumarol: 0–20 nM for wild-type and p.R139W and 0-50 nM for p.P187S; resveratrol: 0–500 μM; nicotinamide: 0–80 mM) and the effect on the enzyme-catalysed rate measured at, at least two concentrations of NAD(P)H and one DCPIP concentration (70 μM). Dicoumarol was dissolved in 0.13 M NaOH and the final concentration of NaOH was in all reactions (including those with zero inhibitor) was 0.65 mM. Resveratrol was dissolved in DMSO and the final volume of DMSO in each reaction was 0.5% v/v including reactions for zero inhibitor. Nicotinamide was dissolved in the buffer used for the reaction. Dixon plots (1/v against [Inhibitor]) were constructed and the apparent inhibition constant, Ki,app calculated [53]. Plots of [S]/v were also constructed for each concentration of NAD(P)H and, together with the corresponding Dixon plot, were used to determine whether the inhibition was strictly competitive or whether it was mixed [54]. A range of inhibitor concentrations were used (in triplicate of triplicate) to construct a Hill plot using 70 μM DCPIP and 300 μM NADH. Linearized Hill plots of (−log10(v/(v0 − v))) against (-log10[Inhibitor]) (where v is the rate and v0 is the rate in the absence of inhibitor) were plotted for each inhibitor, the gradient of this linearized plot is the Hill coefficient, h [55–57]. Experiments to investigate inhibition by dicoumarol were repeated in the presence of excess FAD. For these reactions, enzyme was pre-diluted using a buffered solution of FAD such that the concentration of FAD was 10 times the concentration of active sites in the diluted stock.

Differential scanning fluorimetry

Differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) was carried out using a Rotor-Gene Q cycler (Qiagen). The natural fluorescence resulting from the release of FAD on thermal denaturation was exploited as previously described [39,58–60]. An initial experiment ([wild-type NQO1] and [p.R139W] = 0.25–5 μM dimer; [p.P187S] = 0.25–20 μM dimer) identified an enzyme concentration which gave an optimal fluorescent signal. The apparent binding constants were determined by plotting the change in melting temperature (ΔTm) of each variant at each concentration of inhibitor against the corresponding inhibitor concentration. The data were fitted to (eqn 1) using non-linear curve fitting in GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, U.S.A.).

| (1) |

Where ΔTm,max is the maximum, limiting change in Tm and KD,app is the apparent dissociation constant for the inhibitor and protein.

Results

Both cancer-associated variants show negative cooperativity towards some inhibitors

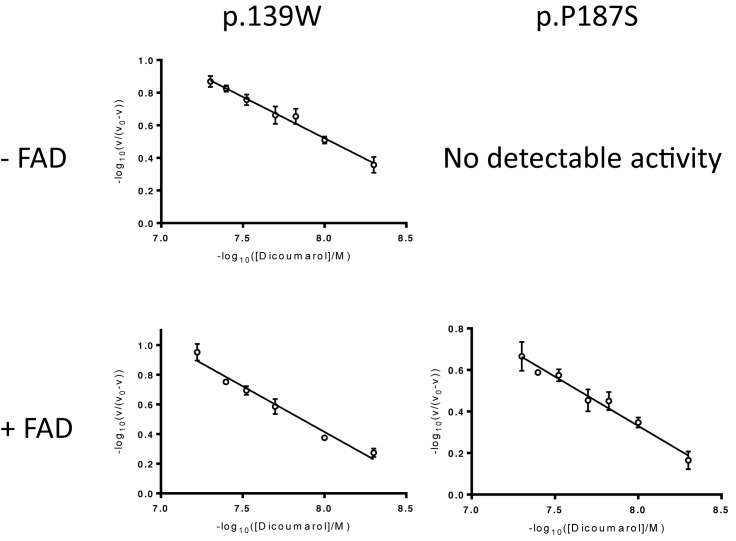

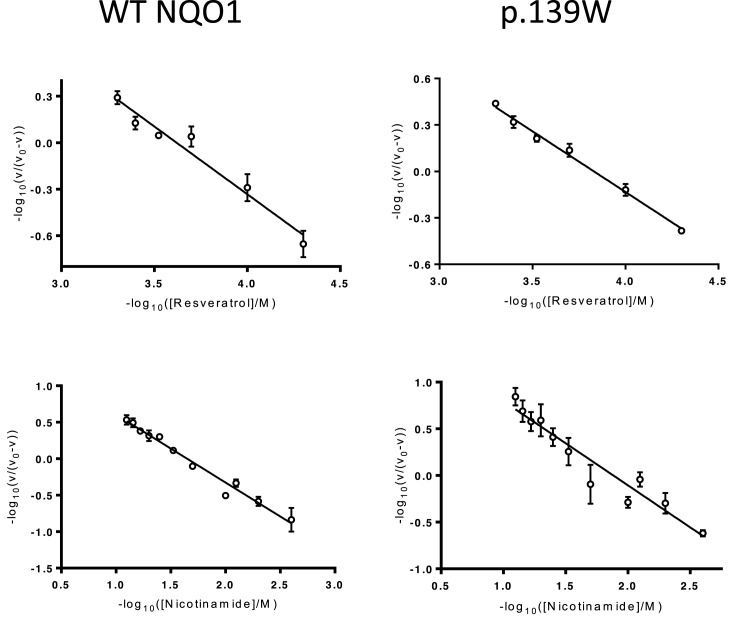

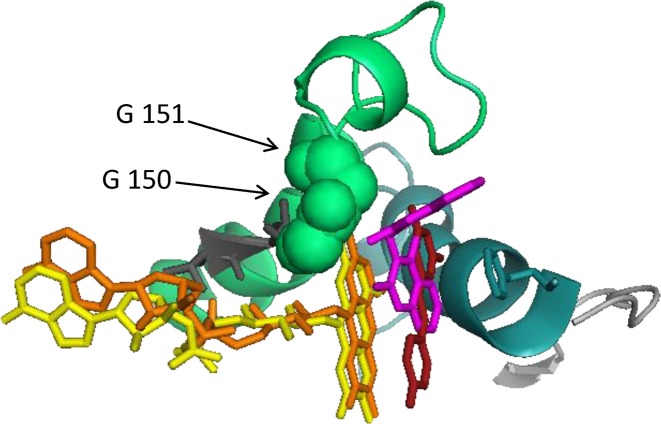

Both cancer-associated variants are competitively inhibited by dicoumarol with Ki,app values in the nM range (Table 1). Interestingly, p.P187S is inhibited less by dicoumarol (Ki,app value approximately ten times higher than wild-type). This most likely reflects the lower thermal stability of this variant: a greater fraction of the protein molecules are likely to be partly unfolded and only properly folded protein is likely to be able to bind to the inhibitor. This inhibition exhibited negative cooperativity towards dicoumarol with Hill coefficients close to 0.5 for all three forms of the protein (Figure 1 and Table 1). Dicoumarol-induced negative cooperativity also occurred when the experiment was repeated after premixing the variants with excess FAD (Figure 1 and Table 1). This ruled out the possibility that the results were due to the different FAD content of the variants. Resveratrol also inhibited the oxidreductase activity of NQO1. The strength of inhibition (as estimated from the Ki,app values determined under similar conditions) is approximately 10,000-fold less than that observed for the structurally related enzyme NRH quinine oxidoreductase 2 (NQO2; EC 1.10.5.1) (Table 1) [58]. In contrast with dicoumarol, resveratrol’s inhibition of NQO1 was not wholly competitive. Dixon plots and corresponding [S]/v plots for the wild-type enzyme indicate that the inhibition was competitive with respect to the electron donor, NADPH but mixed with respect to NADH (data not shown). Resveratrol inhibition of the p.R139W variant was mixed with respect to NADPH and uncompetitive with respect to NADH (data not shown). The wild-type enzyme and p.R139W exhibited slight negative cooperativity towards resveratrol, although not to the same extent as dicoumarol, with Hill coefficients close to 0.85 (Table 1 and Figure 2). Moreover, based on structural alignment with human NQO2 in complex with resveratrol (PDB: 1SG0) [61], the probable binding orientation of resveratrol to human NQO1 suggests that it is unlikely to bind in close contact to the glycine residues at positions 149 and 150 since it is flat and not hinged like dicoumarol (Figure 3); this may explain why, unlike dicoumarol, it only induces slight negative cooperativity.

Table 1. Inhibition constants (Ki,app), Hill coefficients (h) and apparent dissociation constants derived from DSF experiments (KD,app) for wild-type NQO1 and the variants p.R139W and p.P187S.

| Inhibitor | Wild-type NQO1 | p.R139W | p.P187S |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ki,app | |||

| Dicoumarol | 1.15 ± 0.51 nM | 2.98 ± 1.04 nM | 10.95 ± 1.11 nM2 |

| Nicotinamide | 14.01 ± 4.34 mM | 13.55 ± 3.22 mM | nd |

| Resveratrol | 375 ±129 μM | nd | nd |

| Hill coefficient (h) | |||

| Dicoumarol | 0.56 ± 0.09 | 0.51 ± 0.09 | Inactive |

| Dicoumarol + excess FAD | 0.47 ± 0.091,2 | 0.60 ± 0.042 | 0.48 ± 0.022 |

| Resveratrol | 0.89 ± 0.08 | 0.85 ± 0.12 | nd |

| Nicotinamide | 0.91 ± 0.06 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | nd |

| KD,app | |||

| Dicoumarol | 54 ± 4 nM | 66 ± 11 nM | 1100 ± 280 nM |

| Nicotinamide | 6.0 ± 0.9 mM | 18.2 ± 5.2 mM | nd |

h is the mean value from three separate linear Hill plots ± the standard deviation of this mean.

Previously reported and included here for comparison [39].

In excess FAD (10×[active site]).

nd, not determined.

Figure 1. Inhibition of cancer-associated variants of human NQO1 by dicoumarol.

Top row: linear Hill plots constructed using inhibition data in the absence of additional FAD. Rates were measured HEPES-OH buffer pH 7.3 at 37°C in the presence of 0.9 μM lysozyme (as a crowding agent) with 70 μM DCPIP and 300 μM NADH; [p.R139W] = 1nM dimer. Bottom row: Hill plots constructed using inhibition data in the presence of excess FAD (10x [active sites]); [p.R139W] = 1.0 nM dimer; [p.P187S] = 20 nM dimer. Each point represents the mean of three separate determinations and the error bars show the standard error of these means. One representative Hill plot is shown from a triplicate set.

Figure 2. Inhibition of wild-type NQO1 and p.R139W by resveratrol.

Linear Hill plots constructed using resveratrol and nicotinamide inhibition data. Rates were measured in HEPES-OH buffer, pH 7.3, at 37°C in the presence of 0.9 μM lysozyme with 70 μM DCPIP and 300 μM NADH. [WT-NQO1] = 1.0 nM dimer; [p.R139W] = 1.0 nM dimer. Each point represents the mean of three separate determinations and the error bars the standard error of these means. One representative Hill plot is shown from a triplicate set.

Figure 3. Structural alignment of NQO1 with NQO2.

Dicoumarol is shown in pink, resveratrol in red, FAD from NQO2 in orange and FAD from NQO1 in yellow. Resveratol is flat and does not make contact with the glycine residues at position 150 and whereas dicoumarol is bent and does make contact with these residues. The alignment was made using PyMol (www.pymol.org), the command used aligns all atoms but includes an outlier rejection to ignore parts that deviate by more than 2 Å. Structures were taken from: NQO1, PDB 2F1O [11] with FAD from PDB 1QBG [9] and resveratrol from PDB 1SG0 [61].

Nicotinamide inhibited NQO1 and the type of inhibition was mixed. Wild-type NQO1 and the p.R139W variant did not exhibit cooperativity towards nicotinamide (Table 1 and Figure 2). This is expected since nicotinamide is a building block of the electron donors, NADH and NADPH, neither of which induce cooperativity [38,39]. This may be because the nicotinamide moiety does not make the required contacts with glycines at position 149 and 150 to induce cooperativity [10].

Inhibitor binding affects the stability of wild-type and variant NQO1

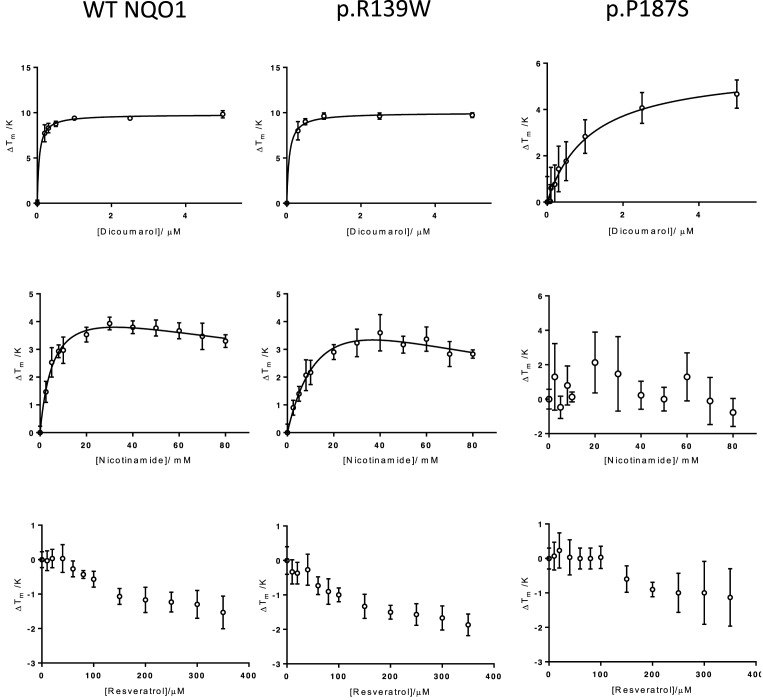

Dicoumarol bound to and stabilized each variant towards thermal denaturation in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4). The KD,app values for dicoumarol determined by differential scanning fluorimetry are unlikely to reflect the true equilibrium constants for the inhibitor–protein interaction. Indeed, they are several order of magnitude different from the apparent inhibition contains derived from kinetic analyses (Table 1). However, there is good reason to believe that they do enable the ranking of affinities and the trend follows that of the apparent inhibition constants. Both sets of values indicate comparably tight binding to the wild-type enzyme and the p.R139W variant and less tight binding to the p.P187S variant (Table 1). This is consistent with previous studies using isothermal titration calorimetry [49].

Figure 4. Thermal stability of wild-type human NQO1 and its cancer-associated variants.

The change in melting temperature (ΔTm) was plotted against the corresponding inhibitor concentration. Each point represents the mean of three values and the error bars the standard error of these means. Top row: stabilization by dicoumarol. Triplicate samples of wild-type NQO1, p.R139W and p.P187S (2, 2 and 15 μM dimer, respectively) in HEPES-OH buffer (pH 7.3) mixed with increasing concentrations of dicoumarol (in 0.13 M NaOH; final [NaOH] constant in each sample (0.65 mM). Middle row: stabilization by nicotinamide. Triplicate samples of wild-type NQO1, p.R139W and p.P187S (2, 2 and 15 μM dimer, respectively) in HEPES-OH buffer (pH 7.3) mixed with increasing concentrations of nicotinamide. Bottom row: destabilization by resveratrol Triplicate samples of wild-type NQO1, p.R139W and p.P187S (2, 2 and15 μM dimer, respectively) in HEPES-OH buffer (pH 7.3) mixed with increasing concentrations of resveratrol (resveratrol dissolved in DMSO; [DMSO] constant in all reactions at 0.5% (v/v)).

Nicotinamide stabilized the wild-type enzyme and p.R139W towards thermal denaturation in a concentration-dependent manner but had no detectable effect on p.P187S (Figure 4). Since wild-type and p.R139W are active and folded [47], nicotinamide’s stabilization of these variants indicates that it binds preferentially to the folded state [62]. This may also explain its inability to stabilise p.P187S: the entropic cost to this variant on binding ligand may be greater than that for wild-type or p.R139W and the enthalpically favourable contacts which would occur on binding nicotinamide may not outweigh the entropic cost for p.P187S.

The effects of resveratrol on thermal stability were less clear. This compound destabilised wild-type NQO1 and both cancer-associated variants (Figure 4). While the effect was clearly concentration dependent, it could not be fitted to any simple model (data not shown). This is in contrast with the related human enzyme, NQO2, which is stabilised by resveratrol [58]. Destabilization by a ligand can indicate that the ligand binds more favourably to partially unfolded molecules [62].

Discussion

The physiological significance of the negative cooperativity towards inhibitors in NQO1 is not known. It has been postulated that it may be involved in regulating NQO1’s cellular activity by an as yet unidentified inhibitor or that it may be important in modulating the protein’s interactions with molecules such as p53 [39]. It may also partly reflect the recently documented negative cooperativity towards the cofactor, FAD since dicoumarol binding requires contacts with FAD as well as the protein itself [11,49,63].

However, the data presented here demonstrate that the cancer-associated polymorphisms in NQO1 do not affect the enzyme’s ability to exhibit negative cooperativity towards the inhibitor dicoumarol. This implies that neither polymorphism exerts its pathological effect by alteration of the enzyme’s negative cooperativity towards inhibitors. Since changing the residues at positions 139 and 187 had no effect on cooperativity, it can be concluded that arginine and proline at these respective positions are not involved in the mechanism of communication between each active site. This is consistent with previous work: these residues are not located within, or close to, residues predicted to be involved in the communication between active sites [39].

Inhibition of NQO1 has been suggested as a cancer therapy [64,65]. Dicoumarol inhibits the growth of some cancer cell lines, (e.g. pancreatic cancer cells [66]). This compound caused an increase in superoxide production (resulting from the one-electron reduction of quinones by cytochrome p450 reductase [66]) as a consequence of its inhibition of NQO1 and its activity as a mitochondrial uncoupling agent [67]. Thymoquinone (TQ) causes the production of superoxide radicals which induce apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Inhibition of NQO1 prevents it from scavenging these radicals [68]. The stabilization of the p.P187S variant by pharmacological chaperones has been suggested as a therapy for patients who are homozygous for the corresponding mutation [46,69]. Such reagents would restore FAD binding activity of this variant and, thus, its activity.

We have shown, for the first time, that resveratrol binds to NQO1 destabilizing it and inhibiting its oxidoreductase activity. The mixed nature of this inhibition may reflect a combination of two effects: competition for the substrate in the active site and reduction in protein stability. This inhibition by resveratrol could be exploited in the search for novel inhibitors of NQO1. However, the inhibition of NQO1 is much weaker than that of NQO2 (approximately 105-fold) and so its physiological significance may be less important. Nevertheless, this effect should be considered in in vitro experiments. Where high (μM to mM) concentrations of resveratrol are used, it cannot be assumed that all effects are due to the inhibition of NQO2. At these concentrations, there will also be some effect on NQO1.

Taken together, our data demonstrate that modulation of negative cooperativity is unlikely to be involved in the molecular pathology of these cancer-associated polymorphisms. However, the reduction in dicoumarol affinity may be important. These suggest that other inhibitors based on dicoumarol may be less effective in patients with these polymorphisms (especially p.P187S). Furthermore, the lower thermal stability of the two variants reported here (and elsewhere [44,47,51,70]) will influence NQO1’s ability to interact with, and regulate, molecules such as p53, p73 and the 20S proteasome. It seems likely that this is the most important, underlying, biochemical reason why these variants lead to increased cancer risk.

Abbreviations

- DSF

differential scanning fluorimetry

- NQO1

NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1

- TQ

thymoquinone

Author Contribution

C.F.M.: experimental work and data analysis. D.J.T.: overall concept of the project and supervision of C.F.M. C.F.M. and D.J.T.: preparation and writing of this paper.

Funding

C.F.M. was supported by a Department of Employment and Learning, Northern Ireland (DELNI, UK) studentship.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

References

- 1.Dinkova-Kostova A.T. and Talalay P. (2010) NAD(P)H:quinone acceptor oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), a multifunctional antioxidant enzyme and exceptionally versatile cytoprotector. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 501, 116–123 10.1016/j.abb.2010.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lind C., Cadenas E., Hochstein P. and Ernster L. (1990) DT-diaphorase: purification, properties, and function. Methods Enzymol. 186, 287–301 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86122-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen S., Wu K. and Knox R. (2000) Structure-function studies of DT-diaphorase (NQO1) and NRH: quinone oxidoreductase (NQO2). Free radical Biol. Med. 29, 276–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaver S.K., Mesa-Torres N., Pey A.L. and Timson D.J. (2019) NQO1: A target for the treatment of cancer and neurological diseases, and a model to understand loss of function disease mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteomics 1867, 663–676 10.1016/j.bbapap.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosoda S., Nakamura W. and Hayashi K. (1974) Properties and reaction mechanism of DT diaphorase from rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 249, 6416–6423 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tedeschi G., Chen S. and Massey V. (1995) DT-diaphorase. Redox potential, steady-state, and rapid reaction studies. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 1198–1204 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tedeschi G., Chen S. and Massey V. (1995) Active site studies of DT-diaphorase employing artificial flavins. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2512–2516 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li R., Bianchet M.A., Talalay P. and Amzel L.M. (1995) The three-dimensional structure of NAD(P)H:quinone reductase, a flavoprotein involved in cancer chemoprotection and chemotherapy: mechanism of the two-electron reduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 8846–8850 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skelly J.V., Sanderson M.R., Suter D.A., Baumann U., Read M.A., Gregory D.S.. et al. (1999) Crystal structure of human DT-diaphorase: a model for interaction with the cytotoxic prodrug 5-(aziridin-1-yl)-2,4-dinitrobenzamide (CB1954). J. Med. Chem. 42, 4325–4330 10.1021/jm991060m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faig M., Bianchet M.A., Talalay P., Chen S., Winski S., Ross D.. et al. (2000) Structures of recombinant human and mouse NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductases: species comparison and structural changes with substrate binding and release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3177–3182 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asher G., Dym O., Tsvetkov P., Adler J. and Shaul Y. (2006) The crystal structure of NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 in complex with its potent inhibitor dicoumarol. Biochemistry 45, 6372–6378 10.1021/bi0600087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cadenas E. and Sies H. (1984) Low-level chemiluminescence as an indicator of singlet molecular oxygen in biological systems. Methods Enzymol. 105, 221–231 10.1016/S0076-6879(84)05029-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lind C., Hochstein P. and Ernster L. (1982) DT-diaphorase as a quinone reductase: a cellular control device against semiquinone and superoxide radical formation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 216, 178–185 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90202-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegel D., Gustafson D.L., Dehn D.L., Han J.Y., Boonchoong P., Berliner L.J.. et al. (2004) NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1: role as a superoxide scavenger. Mol. Pharmacol. 65, 1238–1247 10.1124/mol.65.5.1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu H., Jia Z., Mahaney J.E., Ross D., Misra H.P., Trush M.A.. et al. (2007) The highly expressed and inducible endogenous NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 in cardiovascular cells acts as a potential superoxide scavenger. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 7, 202–211 10.1007/s12012-007-9001-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong X., Gutala R. and Jaiswal A.K. (2008) Quinone oxidoreductases and vitamin K metabolism. Vitam. Horm. 78, 85–101 10.1016/S0083-6729(07)00005-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timson D.J. (2017) Dicoumarol: A Drug which Hits at Least Two Very Different Targets in Vitamin K Metabolism. Curr. Drug Targets 18, 500–510 10.2174/1389450116666150722141906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauer A.K., Faiola B., Abernethy D.J., Marchan R., Pluta L.J., Wong V.A.. et al. (2003) Genetic susceptibility to benzene-induced toxicity: role of NADPH: quinone oxidoreductase-1. Cancer Res. 63, 929–935 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross D., Zhou H. and Siegel D. (2011) Benzene toxicity: The role of the susceptibility factor NQO1 in bone marrow endothelial cell signaling and function. Chem. Biol. Interact. 192, 145–149 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iskander K. and Jaiswal A.K. (2005) Quinone oxidoreductases in protection against myelogenous hyperplasia and benzene toxicity. Chem. Biol. Interact. 153-154, 147–157 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zafar K.S., Siegel D. and Ross D. (2006) A potential role for cyclized quinones derived from dopamine, DOPA, and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid in proteasomal inhibition. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1079–1086 10.1124/mol.106.024703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herrera-Soto A., Diaz-Veliz G., Mora S., Munoz P., Henny P., Steinbusch H.W.M.. et al. (2017) On the Role of DT-Diaphorase Inhibition in Aminochrome-Induced Neurotoxicity In Vivo. Neurotox. Res. 32, 134–140 10.1007/s12640-017-9719-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SantaCruz K.S., Yazlovitskaya E., Collins J., Johnson J. and DeCarli C. (2004) Regional NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase activity in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 25, 63–69 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00117-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raina A.K., Templeton D.J., Deak J.C., Perry G. and Smith M.A. (1999) Quinone reductase (NQO1), a sensitive redox indicator, is increased in Alzheimer’s disease. Redox Rep. 4, 23–27 10.1179/135100099101534701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma Q.L., Yang J.F., Shao M., Dong X.M. and Chen B. (2003) Association between NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase and apolipoprotein E gene polymorphisms in Alzheimer’s disease. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 83, 2124–2127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raina A.K., Templeton D.J., Deak J.C., Perry G. and Smith M.A. (1999) Quinone reductase (NQO1), a sensitive redox indicator, is increased in Alzheimer’s disease. Redox Rep. 4, 23–27 10.1179/135100099101534701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.SantaCruz K.S., Yazlovitskaya E., Collins J., Johnson J. and DeCarli C. (2004) Regional NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase activity in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 25, 63–69 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00117-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anwar A., Dehn D., Siegel D., Kepa J.K., Tang L.J., Pietenpol J.A.. et al. (2003) Interaction of human NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) with the tumor suppressor protein p53 in cells and cell-free systems. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 10368–10373 10.1074/jbc.M211981200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gong X., Kole L., Iskander K. and Jaiswal A.K. (2007) NRH:quinone oxidoreductase 2 and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 protect tumor suppressor p53 against 20s proteasomal degradation leading to stabilization and activation of p53. Cancer Res. 67, 5380–5388 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asher G., Bercovich Z., Tsvetkov P., Shaul Y. and Kahana C. (2005) 20S proteasomal degradation of ornithine decarboxylase is regulated by NQO1. Mol. Cell 17, 645–655 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asher G., Tsvetkov P., Kahana C. and Shaul Y. (2005) A mechanism of ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation of the tumor suppressors p53 and p73. Genes Dev. 19, 316–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medina-Carmona E., Neira J.L., Salido E., Fuchs J.E., Palomino-Morales R., Timson D.J.. et al. (2017) Site-to-site interdomain communication may mediate different loss-of-function mechanisms in a cancer-associated NQO1 polymorphism. Sci. Rep. 7, 44532 10.1038/srep44532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adler J., Reuven N., Kahana C. and Shaul Y. (2010) c-Fos proteasomal degradation is activated by a default mechanism, and its regulation by NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 determines c-Fos serum response kinetics. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 3767–3778 10.1128/MCB.00899-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alard A., Fabre B., Anesia R., Marboeuf C., Pierre P., Susini C.. et al. (2010) NAD(P)H quinone-oxydoreductase 1 protects eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4GI from degradation by the proteasome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 1097–1105 10.1128/MCB.00868-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siegel D., Yan C. and Ross D. (2012) NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) in the sensitivity and resistance to antitumor quinones. Biochem. Pharmacol. 83, 1033–1040 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey S.M., Lewis A.D., Knox R.J., Patterson L.H., Fisher G.R. and Workman P. (1998) Reduction of the indoloquinone anticancer drug EO9 by purified DT-diaphorase: a detailed kinetic study and analysis of metabolites. Biochem. Pharmacol. 56, 613–621 10.1016/S0006-2952(97)00661-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parkinson E.I., Bair J.S., Cismesia M. and Hergenrother P.J. (2013) Efficient NQO1 substrates are potent and selective anticancer agents. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 2173–2183 10.1021/cb4005832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rase B., Bartfai T. and Ernster L. (1976) Purification of DT-diaphorase by affinity chromatography. Occurrence of two subunits and nonlinear Dixon and Scatchard plots of the inhibition by anticoagulants. Arch. Biochem. Biophysics. 172, 380–386 10.1016/0003-9861(76)90089-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Megarity C.F., Bettley H.A., Caraher M.C., Scott K.A., Whitehead R.C., Jowitt T.A.. et al. (2019) Negative cooperativity in NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1). ChemBioChem. in press 10.1002/cbic.201900313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pey A.L., Megarity C.F. and Timson D.J. (2019) NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1): an enzyme which needs just enough mobility, in just the right places. Biosci. Rep. 39, BSR20180459 10.1042/BSR20180459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gunasekaran K., Ma B. and Nussinov R. (2004) Is allostery an intrinsic property of all dynamic proteins? Proteins 57, 433–443 10.1002/prot.20232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goodey N.M. and Benkovic S.J. (2008) Allosteric regulation and catalysis emerge via a common route. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 474–482 10.1038/nchembio.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Traver R.D., Horikoshi T., Danenberg K.D., Stadlbauer T.H., Danenberg P.V., Ross D.. et al. (1992) NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase gene expression in human colon carcinoma cells: characterization of a mutation which modulates DT-diaphorase activity and mitomycin sensitivity. Cancer Res. 52, 797–802 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Traver R.D., Siegel D., Beall H.D., Phillips R.M., Gibson N.W., Franklin W.A.. et al. (1997) Characterization of a polymorphism in NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase (DT-diaphorase). Br. J. Cancer 75, 69–75 10.1038/bjc.1997.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu L.T., Stamberg J. and Pan S. (1996) The NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase locus in human colon carcinoma HCT 116 cells resistant to mitomycin C. Cancer Res. 56, 5253–5259 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pey A.L., Megarity C.F., Medina-Carmona E. and Timson D.J. (2016) Natural small molecules as stabilizers and activators of cancer-associated NQO1 polymorphisms. Curr. Drug Targets 17, 1506–1514 10.2174/1389450117666160101121610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pey A.L., Megarity C.F. and Timson D.J. (2014) FAD binding overcomes defects in activity and stability displayed by cancer-associated variants of human NQO1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1842, 2163–2173 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Medina-Carmona E., Fuchs J.E., Gavira J.A., Mesa-Torres N., Neira J.L., Salido E.. et al. (2017) Enhanced vulnerability of human proteins towards disease-associated inactivation through divergent evolution. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26, 3531–3544 10.1093/hmg/ddx238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Medina-Carmona E., Palomino-Morales R.J., Fuchs J.E., Esperanza P.G., Noel M.T., Salido E.. et al. (2016) Conformational dynamics is key to understanding loss-of-function of NQO1 cancer-associated polymorphisms and its correction by pharmacological ligands. Sci. Rep. 6, 20331 10.1038/srep20331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Munoz I.G., Morel B., Medina-Carmona E. and Pey A.L. (2017) A mechanism for cancer-associated inactivation of NQO1 due to P187S and its reactivation by the consensus mutation H80R. FEBS Lett. 591, 2826–2835 10.1002/1873-3468.12772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lienhart W.D., Gudipati V., Uhl M.K., Binter A., Pulido S.A., Saf R.. et al. (2014) Collapse of the native structure caused by a single amino acid exchange in human NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase. FEBS J. 281, 4691–4704 10.1111/febs.12975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lienhart W.D., Strandback E., Gudipati V., Koch K., Binter A., Uhl M.K.. et al. (2017) Catalytic competence, structure and stability of the cancer-associated R139W variant of the human NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1). FEBS J. 284, 1233–1245 10.1111/febs.14051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dixon M. (1953) The determination of enzyme inhibitor constants. Biochem. J. 55, 170–171 10.1042/bj0550170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cornish-Bowden A. (1974) A simple graphical method for determining the inhibition constants of mixed, uncompetitive and non-competitive inhibitors. Biochem. J. 137, 143–144 10.1042/bj1370143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hill A.V. (1910) The possible effects of the aggregation of molecules of haemoglobin on its dissociation curve. J. Physiol. (London) 40, 4–7 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Engel P.C. (1996) Chapter 3: Enzyme Kinetics. In Enzymology LabFax, Bio Scientific Publishers, Oxford, U.K. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Timson D.J. (2015) Quantitative enzymology. Current Enzyme Inhibit. 11, 12–31 10.2174/157340801101150707124226 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Megarity C.F., Gill J.R., Caraher M.C., Stratford I.J., Nolan K.A. and Timson D.J. (2014) The two common polymorphic forms of human NRH-quinone oxidoreductase 2 (NQO2) have different biochemical properties. FEBS Lett. 588, 1666–1672 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.02.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Megarity C.F., Looi H.K. and Timson D.J. (2014) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae quinone oxidoreductase Lot6p: stability, inhibition and cooperativity. FEMS Yeast Res. 14, 797–807 10.1111/1567-1364.12167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Forneris F., Orru R., Bonivento D., Chiarelli L.R. and Mattevi A. (2009) ThermoFAD, a Thermofluor-adapted flavin ad hoc detection system for protein folding and ligand binding. FEBS J. 276, 2833–2840 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07006.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Buryanovskyy L., Fu Y., Boyd M., Ma Y., Hsieh T.C., Wu J.M.. et al. (2004) Crystal structure of quinone reductase 2 in complex with resveratrol. Biochemistry 43, 11417–11426 10.1021/bi049162o [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cooper A., Nutley M.A. and Wadood A. (2001) Differential scanning microcalorimetry. In Protein-Ligand Interactions: A Practical Approach(Harding S.E. and Chowdhury B., eds), Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 63.Claveria-Gimeno R., Velazquez-Campoy A. and Pey A.L. (2017) Thermodynamics of cooperative binding of FAD to human NQO1: Implications to understanding cofactor-dependent function and stability of the flavoproteome. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 636, 17–27 10.1016/j.abb.2017.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nolan K.A., Timson D.J., Stratford I.J. and Bryce R.A. (2006) In silico identification and biochemical characterization of novel inhibitors of NQO1. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 16, 6246–6254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reigan P., Colucci M.A., Siegel D., Chilloux A., Moody C.J. and Ross D. (2007) Development of indolequinone mechanism-based inhibitors of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1): NQO1 inhibition and growth inhibitory activity in human pancreatic MIA PaCa-2 cancer cells. Biochemistry 46, 5941–5950 10.1021/bi700008y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cullen J.J., Hinkhouse M.M., Grady M., Gaut A.W., Liu J., Zhang Y.P.. et al. (2003) Dicumarol inhibition of NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase induces growth inhibition of pancreatic cancer via a superoxide-mediated mechanism. Cancer Res. 63, 5513–5520 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nolan K.A., Zhao H., Faulder P.F., Frenkel A.D., Timson D.J., Siegel D.. et al. (2007) Coumarin-Based Inhibitors of Human NAD(P)H:Quinone Oxidoreductase-1. Identification, Structure-Activity, Off-Target Effects and In Vitro Human Pancreatic Cancer Toxicity. J. Med. Chem. 50, 6316–6325 10.1021/jm070472p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sutton K.M., Doucette C.D. and Hoskin D.W. (2012) NADPH quinone oxidoreductase 1 mediates breast cancer cell resistance to thymoquinone-induced apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 426, 421–426 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.08.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Betancor-Fernandez I., Timson D.J., Salido E. and Pey A.L. (2018) natural (and unnatural) small molecules as pharmacological chaperones and inhibitors in cancer. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 245, 155–190 10.1007/164_2017_55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Siegel D., Anwar A., Winski S.L., Kepa J.K., Zolman K.L. and Ross D. (2001) Rapid polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of a mutant form of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1. Mol. Pharmacol. 59, 263–268 10.1124/mol.59.2.263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]