Abstract

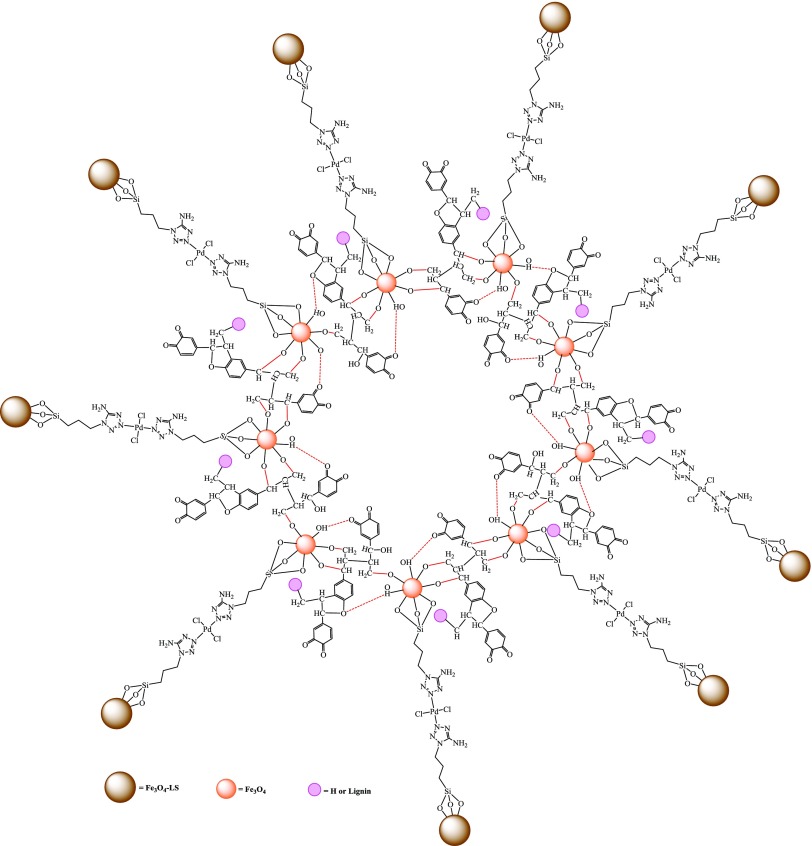

A novel strategy is described to prepare magnetic Pd nanocatalyst by conjugating lignin with Fe3O4 nanoparticles via activation of calcium lignosulfonate, followed by combination with Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Tethering 5-amino-1H-tetrazole to calcium lignosulfonate-magnetite hybrid through 3-chloropropyl triethoxysilane enabled coordination of Pd salt with Fe3O4-lignosulfonate@5-amino-1H-tetrazole. The underlying changes of the lignosulfonate are identified, and the structural morphology of attained Fe3O4-lignosulfonate@5-amino-1H-tetrazole-Pd(II) (FLA-Pd) is characterized by Fourier transform infrared, thermogravimetry differential thermal analysis, energy-dispersive spectrometry, field-emission scanning electron microscopy, transmission electron microscopy, and vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM). The synthesized FLA-Pd displayed high activity for phosphine-free C(sp2)–C(sp2) coupling in water, and the catalyst could be reused for seven successive cycles.

Introduction

Lignin is an amorphous polymer that comprise three main monomer blocks, namely coniferyl, p-coumaryl, and sinapyl alcohol1,2 and is the second most plentiful biomass on the planet earth after cellulose. One of the most important sources of commercial lignin is the byproduct from biorefineries and pulp industries,3,4 and its conversion to a high value-added products has been continually explored.5 Because of the attendance of phenolic, hydroxyl, methoxy, carbonyl, carboxyl, and aldehyde groups, lignin and its derivatives are endowed with exclusive uses such as antioxidants, antimicrobial agents, in removal of heavy metal ions and toxic dyes, carbon precursors, UV adsorbents, and biomaterials for gene therapy and tissue engineering;6−12 progressive lignin modification has created various functional lignin-based materials with unique properties.13

The preparation of heterogeneous catalysts has been extensively investigated in contrast to homogeneous counterparts because of recyclability, facile work-up, and ease of handling.14,15 Among heterogeneous catalysts, magnetite nanoparticles (MNPs) have garnered abundant attention owing to their low cost, stability and toxicity, high reactivity, good biocompatibility, easy separation by an external magnet, and importantly, the small size, large surface area, and good magnetic permeability.16−21

The C–C coupling reactions22 like Sonogashira,23 Suzuki–Miyaura,24 Hiyama,25 and Heck26 represent strong synthetic tools to generate new natural products, heterocycles, molecular electronics, dendrimers, and conjugated polymers. Among these, Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reactions offer an effective process for the preparation of pharmaceuticals because of compatibility of functional groups and accessibility of organoboron compounds under mild reaction conditions;27,28 Pd-catalyzed C–C coupling reactions are one of the most important advancements in synthetic organic chemistry due to high production yields, fast reaction rates, high turnover frequency, and selectivity.29,30

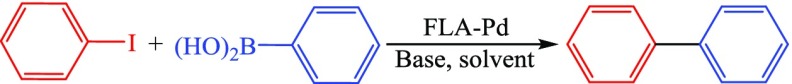

We envisioned an efficient method for the fabrication of the Pd(II) complex supported on Fe3O4-lignosulfonate (FLA-Pd) (Scheme 1) and demonstrate its prowess for the phosphine-free Suzuki–Miyaura reaction (Scheme 2) in water as a non-toxic solvent wherein lignin biopolymer, a renewable resource, functions as a natural support for the immobilization of Pd complex.

Scheme 1. Schematic Representation of the Structure of Fe3O4@Lignosulfonate@5-Amino-1H-tetrazole@Pd(II) (FLA-Pd).

Scheme 2. Step-wise Synthesis of Fe3O4-Lignosulfonate@5-Amino-1H-tetrazole Monohydrate-Pd(II) (FLA-Pd).

Results and Discussion

FLA-Pd Characterization

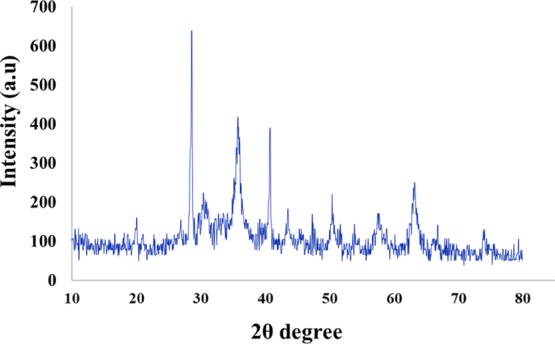

The characterization of the FLA-Pd was carried out using X-ray diffraction (XRD), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), energy-dispersive spectrometry (EDS), Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR), vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM), and thermogravimetry differential thermal analysis (TG-DTA) techniques. An XRD pattern of the prepared FLA-Pd was applied for lignosulfonate adsorption on the Fe3O4 surface (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of the FLA-Pd.

The XRD pattern of FLA-Pd was very similar to that of the magnetic NPs, implying that the crystal Fe3O4 did not change, and magnetic NPs have been coated with lignosulfonate.

The patterns at 2θ values 28.6°, 35.8°, 50.4°, 57.6°, and 63.1° can be attributed to (2 2 0), (3 1 1), (4 2 2), (5 1 1), and (4 4 0) planes of the cubic structure of Fe3O4 (JCPDS 19-0629), demonstrating the crystalline structure of Fe3O4. In addition, the presence of palladium and its immobilization on the Fe3O4-lignosulfonate@5-amino-1H-tetrazole was confirmed with the diffraction peaks at 2θ = 40.8°, 47.3°, 68.5° attributed to (1 1 1), (2 0 0), and (2 2 0) crystal planes of face-centered Pd.

FT-IR spectroscopy was applied for the characterization of the functionality of calcium lignosulfonate (A), Fe3O4-lignosulfonate (B), Fe3O4-lignosulfonate@(CH2)3–Cl (C), FLA (D), and FLA-Pd (E) (Figure 2). In Figure 2A–E, the peak at 3000–3500 and 1000–1200 and 1050–1200 cm–1 is because of stretching vibrations of the O–H, C–O, and O=S=O in calcium lignosulfonate, respectively. The peak appeared at 1400 cm–1 is attributed to aromatic carbons that exist in calcium lignosulfonate (Figure 2A). The formation of Fe3O4-lignosulfonate and its sustainability until the last stage was approved by the peak appeared at 585 cm–1, which is ascribed to the vibration of Fe–O in the Fe3O4 MNPs (Figure 2B–E). The peak at 1600 cm–1 is also linked to the C=O stretching mode in Fe3O4-lignosulfonate (Figure 2B). The peaks at 2800–3000 and 1400–1500 cm–1 may be assigned to C–H stretching and bending vibrations of CH2 groups (Figure 2C). Finally, the band around 1450 cm–1 indicated the N=N stretching vibrations of the 5-amino-1H-tetrazole (Figure 2D,E).

Figure 2.

FT-IR spectra of calcium lignosulfonate (A), Fe3O4-lignosulfonate (B), Fe3O4@lignosulfonate–(CH2)3–Cl (C), FLA (D), and FLA-Pd (E).

The chemical composition of calcium lignosulfonate, Fe3O4-lignosulfonate, and the FLA-Pd was analyzed at each stage by the EDS analysis (Figure 3), which confirms the existence of the desired elements in their chemical structure; the EDS spectrum of the lignosulfonate confirmed that it comprised S, C, O, and Ca (Figure 3A). Figure 3 confirmed that C, O, S, Fe, and Ca were main components present in both Fe3O4-lignosulfonate and FLA-Pd along with N, Si, Pd, Cl, K, and I elements, which were present only in the FLA-Pd (Figure 3C), further reaffirming the formation of the final catalyst. Additionally, the existence of C, N, O, Fe, and Pd was emphasized with elemental mapping images (Figure 4); which showed that Pd is dispersed uniformly on the FLA surface.

Figure 3.

EDS images of lignosulfonate (A), Fe3O4-lignosulfonate (B), and FLA-Pd (C).

Figure 4.

Elemental mapping of the FLA-Pd.

FESEM images of calcium lignosulfonate, Fe3O4-lignosulfonate, and the FLA-Pd are presented in Figure 5. According to the FESEM analysis results, the shapes of the calcium lignosulfonate are irregular (Figure 5A), while Fe3O4-lignosulfonate has a spherical morphology (Figure 5B). Also, the FLA-Pd show an average particle size in the 20–27 nm range with a spherical morphology. The morphology of the FLA-Pd was also investigated using TEM images (Figure 6), which corroborates FESEM findings.

Figure 5.

Surface morphology as apparent from FESEM images of lignosulfonate (A), Fe3O4-lignosulfonate (B), and the FLA-Pd (C).

Figure 6.

TEM images of the FLA-Pd.

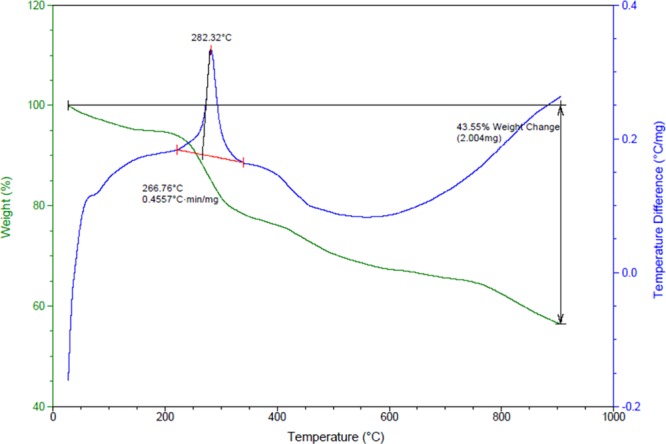

The results of TG-DTA analysis of FLA-Pd are shown in Figure 7. There are six clear weight loss peaks discernible in the TG-DTA curves. The first weight loss, in the range 30–200 °C, was caused by the elimination of physically absorbed H2O within the Ca lignosulfonate and desorption of organic solvents. The second loss occurred in range 200–290 °C, which is attributed to the cleavage of C–O–C and C–C chemical bonds and other organic moieties. The next weight loss in 300 is due to the decomposition of the calcium lignosulfonate framework, which was associated with the release of small molecules including oxygen, calcium, carbon, sulfur, and hydrogen. The fourth stage, in 400 °C range, corresponds to the disintegration of 5-amino-1H-tetrazole monohydrate. Further, a weight loss was detected in 600 °C, which is caused by the carbonization and decomposition of calcium lignosulfonate and its aromatic rings. The last stage was found in 800 °C, attributed to decomposition of the nanocatalyst.

Figure 7.

TG-DTA analysis of the FLA-Pd.

The magnetic hysteresis loop of the FLA-Pd is illustrated in Figure 8; a magnetic behavior was investigated with the field sweeping in the range of −15 000 to +15 000 Oe. The results acknowledge that the FLA possessed sensitive magnetic responsiveness, which can be easily removed by deploying an external magnet.

Figure 8.

Magnetization curves of the FLA-Pd.

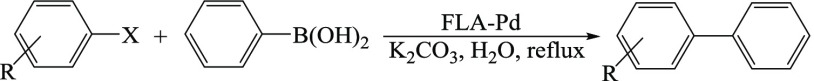

FLA-Pd-Catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura Reaction

The catalytic applicability of the FLA-Pd was examined for the Suzuki–Miyaura reaction of iodobenzene with C6H5B(OH)2 as a model reaction. The reaction was carried out deploying 0.05 g of the FLA-Pd and 2.0 mmol of K2CO3 under reflux conditions in H2O as a green solvent; the absence of the FLA-Pd did not produce any coupling reaction, and no coupling product could be observed.

To optimize the catalytic reaction conditions of the PhI (1.0 mmol) with PhB(OH)2 (1.1 mmol) using FLA-Pd, various bases such as K2CO3, NaOAc, NaHCO3, n-Pr3N, Et3N, and solvents namely tetrahydrofuran (THF), toluene, H2O, and EtOH were screened (Table 1); high yield of the favorable product was discerned when the reaction was performed in water using FLA-Pd (0.05 g) and K2CO3 (2.0 mmol) at 100 °C for 1 h (entry 1).

Table 1. Preparation of Biphenyl under Different Conditionsa.

| entry | solvent | FLA-Pd (g) | base | T (°C) | time (min) | yield (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | THF | 0.05 | K2CO3 | reflux | 120 | 65 |

| 2 | toluene | 0.05 | K2CO3 | reflux | 120 | 42 |

| 3 | H2O | 0.05 | – | rt | 240 | 0 |

| 4 | H2O | 0.05 | – | reflux | 240 | 0 |

| 5 | EtOH | 0.05 | K2CO3 | reflux | 60 | 70 |

| 6 | H2O | 0.05 | K2CO3 | reflux | 60 | 93 |

| 7 | H2O | 0.05 | NaOAc | reflux | 120 | 50 |

| 8 | H2O | 0.05 | NaHCO3 | reflux | 120 | 76 |

| 9 | H2O | 0.05 | Et3N | reflux | 120 | 61 |

| 10 | H2O | 0.05 | n-Pr3N | reflux | 120 | 62 |

| 11 | H2O | 0.03 | K2CO3 | reflux | 120 | 70 |

| 12 | H2O | 0.07 | K2CO3 | reflux | 60 | 93 |

Reaction conditions: PhI (1.0 mmol); PhB(OH)2 (1.1 mmol); base (2.0 mmol); solvent (10.0 mL).

Isolated yield of the pure product.

The reaction between PhB(OH)2 and aryl halides bearing electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups was performed, and they all afforded biphenyl derivatives in 81–93% yields within 1–2 h using 0.05 g of the FLA-Pd in H2O (Table 2); chlorobenzene produced the corresponding product in good yield as well (entry 13). The melting points of all of biaryls were consistent with the recorded literature values.

Table 2. FLA-Pd-Catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura Coupling Reaction of C6H5B(OH)2 with Various Aryl Halidesa.

| entry | R | X | time (min) | yield (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | I | 60 | 93 |

| 2 | 4-OMe | I | 60 | 92 |

| 3 | 2-OMe | I | 60 | 90 |

| 4 | 4-Me | I | 60 | 91 |

| 5 | 4-CHO | I | 60 | 90 |

| 6 | 4-NO2 | I | 70 | 90 |

| 7 | 4-COOH | I | 60 | 89 |

| 8 | H | Br | 90 | 90 |

| 9 | 4-OMe | Br | 90 | 89 |

| 10 | 4-Me | Br | 90 | 88 |

| 11 | 4-NO2 | Br | 100 | 88 |

| 12 | 4-COOH | Br | 90 | 87 |

| 13 | H | Cl | 240 | 81 |

Reaction conditions: C6H5B(OH)2 (1.1 mmol), aryl halide (1.0 mmol), FLA-Pd (0.05 g), K2CO3 (2.0 mmol), H2O (10.0 mL), reflux.

Isolated yield.

Furthermore, we checked the catalytic superiority and remarkable features of FLA-Pd in comparison to reported catalytic systems in the literature for Suzuki–Miyaura reaction in H2O or H2O/EtOH and H2O/DMF mixture (Table 3). Clearly, the FLA-Pd provided higher yields in a shorter reaction time and higher catalytic activity in comparison to other catalysts.

Table 3. Comparison of the FLA-Pd with Other Reported Catalysts in the Reaction of Bromobenzene with C6H5B(OH)2.

| entry | catalyst | solvent | T (°C) | time (h) | yield (%)a | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pd@Nf-G | EtOH/H2O | 80 | 3 | 88 | (31) |

| 2 | Pd@aminoclay | H2O | 100 | 4 | 87 | (32) |

| 3 | Pd NPs/PS | H2O/DMF | 100 | 12 | 80 | (33) |

| 4 | Pd NPs | H2O | 100 | 12 | 85 | (34) |

| 5 | Fe3O4@RGO@Au@C | H2O | 100 | 18 | 88 | (35) |

| 6 | Au NPs@HS-G-PMS hybrid | H2O | 110 | 6 | 86 | (36) |

| 7 | Fe3O4@SiO2-4-AMTT-Pd(II) | H2O | 50 | 3.5 | 68 | (37) |

| 8 | Pd(OAc)2/L1 | H2O | 90 | 2 | 86 | (38) |

| 10 | Mag-IL-Pd | H2O | 60 | 7.5 | 82 | (39) |

| 11 | Pd(OAc)2 | H2O | 100 | 12 | 42 | (40) |

| 12 | Pd(0)-MCM-41 | EtOH/H2O | 80 | 12 | 90 | (41) |

| 13 | CuO/Pd-3 | DMF | 110 | 10 | 80 | (42) |

| 14 | Pd–CoFe2O4 MNP | EtOH | reflux | 12 | 79 | (43) |

| 15 | Pd2+-sepiolite | DMF | 100 | 1 | 81 | (44) |

| 16 | Ni/Pd core/shell NPs/graphene | DMF/H2O | 110 | 30 min | 78 | (45) |

| 17 | Pd NPs/ionic polymer-doped graphene | EtOH/H2O | 60 | 24 | 24 | (46) |

| 18 | Pd–Co (1:1)/graphene | EtOH/H2O | 80 | 4 | 76b | (47) |

| 19 | FLA-Pd | H2O | 100 | 1 | 90 | this work |

Isolated yield of the pure product.

Conversion.

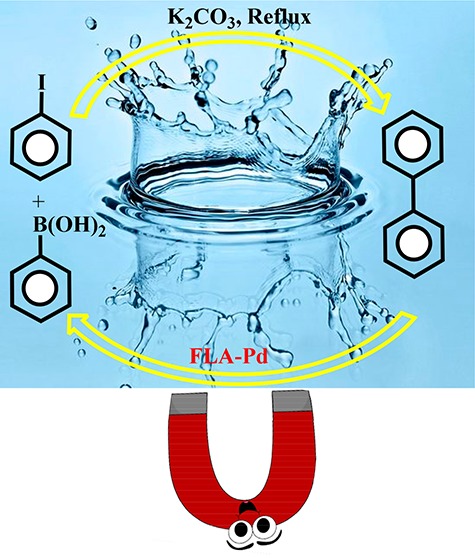

Catalyst Recyclability

The recyclability of the catalyst system is one of the prominent issues from the standpoint of cost-effectiveness and environmental impact. The FLA-Pd nanocatalyst could be collected via an external magnet because of its magnetic properties. The recyclability of the as-prepared FLA-Pd was next examined using the Suzuki coupling reaction of PhB(OH)2 with PhI in the presence of K2CO3 under reflux conditions in water. As shown in Figure 9, the FLA-Pd can be reused at least seven times, with minor fluctuation in yields. As shown in the TEM and FESEM images of the recycled FLA-Pd (Figures S1 and S2), no clear variation in the morphology of the FLA-Pd and its size was discerned.

Figure 9.

Recycling experiments of the FLA-Pd for Suzuki coupling.

Conclusions

This study introduces a new, efficient, and eco-friendly approach for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction through the fabrication of a highly active and sustainable catalytic system using a calcium lignosulfonate biopolymer as a renewable resource and natural support for the immobilization of the 5-amino-1H-tetrazole-Pd(II) complex. The Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction was performed for an assorted array of aryl halides in H2O as a greener solvent, and consistently high yields of the biaryls were obtained. In addition, the synthesized catalyst could be reused for successive seven cycles with high efficiency. The use of renewable and abundant resource materials bodes well for its application in other heterogeneous catalytic systems.

Experimental Section

Reagents and Methods

All chemicals were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co. and were directly used for the fabrication of catalyst and biaryls. FT-IR spectra using a Thermo Nicolet 370 FT-IR spectrometer were used to record the functional groups in the 400–4000 cm–1 range. TEM and FESEM analyses were used to determine the particle size and morphology using Philips CM120 and Cam scan Mv2300, respectively. The chemical composition analysis of the FLA-Pd was performed using EDS in the FESEM system. XRD analysis was obtained by using a Philips PW 1373 X-ray diffractometer (Cu Kα = 1.5406 Å) in a 2θ range 10°–80° to evaluate the structure of the FLA-Pd. TG-DTG and VSM measurements were performed by using a STA 1500 Rheometric Scientific (England) and Quantum Design MPMS 5XL SQUID magnetometer, respectively.

Preparation of Fe3O4-Lignosulfonate

For the synthesis of Fe3O4-lignosulfonate, calcium lignosulfonate was activated with potassium periodate (KIO4) as its functional groups (CHO, OMe, PhOH, and OH) are occupied in interunit linkages; functional group activation help assist its binding to the surface of Fe3O4. Calcium lignosulfonate was dissolved in the dioxane/water (9:1, v/v) (solution 1) to which aqueous solution of potassium periodate (solution 2) was added in the dark; solution 2 was added with a peristaltic pump into solution 1. Then, Fe3O4 nanoparticles (NPs) were added to the preactivated calcium lignosulfonate at pH = 6.4, in mass ratios 5:1 for 2 h. The final solution was filtered, and the ensuing Fe3O4-lignosulfonate was washed with EtOH and dried at 110 °C (Scheme 2A).

Preparation of Fe3O4@Lignosulfonate@5-Amino-1H-tetrazole

Fe3O4@lignosulfonate@5-amino-1H-tetrazole (FLA) was obtained by adding (3-chloropropyl)trimethoxysilane (3.0 mL) to 1.0 g Fe3O4-lignosulfonate taken in dry toluene (80.0 mL) under reflux conditions and a nitrogen atmosphere for 12 h (Scheme 2B). The synthesized Fe3O4-lignosulfonate@(CH2)3–Cl was decanted via a magnet, washed with diethyl ether, and then dried under vacuum at 70 °C for 5 h. Next, 5.0 mmol of 5-amino-1H-tetrazole, 2.0 g of the Fe3O4-lignosulfonate@(CH2)3–Cl, 5.0 mmol of K2CO3, and 50.0 mL of DMF were admixed in a flask and refluxed for 24 h. The ensuing Fe3O4-lignosulfonate@(CH2)3–Cl can be easily collected and used for the next stage (Scheme 2C).

Preparation of the FLA-Pd Complex

Finally, the Fe3O4-lignosulfonate@(CH2)3–Cl (1.0) and 0.5 g of PdCl2 were mixed in EtOH (50.0 mL) and heated at 80 °C for 24 h. Then, the obtained complex was collected with an external magnet, washed with EtOH, dried, and then used as a new magnetic catalyst in the next cycle (Scheme 2D).

Suzuki–Miyaura Coupling Reaction

A round-bottomed flask was filled with 1.1 mmol of C6H5B(OH)2, 1.0 mmol of aryl halide, 2.0 mmol of K2CO3, 0.05 g of FLA-Pd, and 10 mL of water and stirred under reflux conditions for the adequate time. The conversion of aryl halide was checked by thin-layer chromatography. When the reaction was completed, the catalyst was decanted using an external magnetic field, and the coupling product was then purified by flash chromatography. The obtained biaryls were characterized by melting point and confirmed by NMR.

Acknowledgments

The support provided by the University of Qom is appreciated.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.9b01640.

TEM and FESEM images for the recovered FLA-Pd catalyst (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kai D.; Tan M. J.; Chee P. L.; Chua Y. K.; Yap Y. L.; Loh X. J. Towards lignin-based functional materials in a sustainable world. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 1175–1200. 10.1039/c5gc02616d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S.; Patil S.; Argyropoulos D. S. Thermal properties of lignin in copolymers, blends, and composites: a review. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 4862–4887. 10.1039/c5gc01066g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Upton B. M.; Kasko A. M. Strategies for the conversion of lignin to high-value polymeric materials: review and perspective. Chem. Rev. 2015, 116, 2275–2306. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur V. K.; Thakur M. K.; Raghavan P.; Kessler M. R. Progress in green polymer composites from lignin for multifunctional applications: a review. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1072–1092. 10.1021/sc500087z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S.; Nadagouda M.; Varma R. S. Visible light-mediated and water-assisted selective hydrodeoxygenation of lignin-derived guaiacol to cyclohexanol. Green Chem 2019, 21, 1253. 10.1039/C8GC03951H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-Y.; Johnston P. A.; Lee J. H.; Smith R. G.; Brown R. C. Improving lignin homogeneity and functionality via ethanolysis for production of antioxidants. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 3520–3526. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b05769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larrañeta E.; Imízcoz M.; Toh J. X.; Irwin N. J.; Ripolin A.; Perminova A.; Domínguez-Robles J.; Rodríguez A.; Donnelly R. F. Synthesis and characterization of lignin hydrogels for potential applications as drug eluting antimicrobial coatings for medical materials. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 9037–9046. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b01371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y.; Li Z. Application of lignin and its derivatives in aqdsorption of heavy metal ions in water: a review. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 7181–7192. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b01345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Culebras M.; Sanchis M. J.; Beaucamp A.; Carsí M.; Kandola B. K.; Horrocks A. R.; Panzetti G.; Birkinshaw C.; Collins M. N. Understanding the thermal and dielectric response of organosolv and modified kraft lignin as a carbon fibre precursor. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 4461–4472. 10.1039/c8gc01577e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zong E.; Huang G.; Liu X.; Lei W.; Jiang S.; Ma Z.; Wang J.; Song P. A lignin-based nano-adsorbent for superfast and highly selective removal of phosphate. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 9971–9983. 10.1039/c8ta01449c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Huang X.; Han K.; Dai Y.; Zhang X.; Zhao Y. High-performance lignin-based water-soluble macromolecular photoinitiator for the fabrication of hybrid hydrogel. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 4004–4011. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b05357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat W.; Venditti R.; Mignard N.; Taha M.; Becquart F.; Ayoub A. Polysaccharides and lignin based hydrogels with potential pharmaceutical use as a drug delivery system produced by a reactive extrusion process. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 564–575. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C.; He H.; Yao X.; Yu P.; Zhou L.; Jia D. The aggregation structure regulation of lignin by chemical modification and its effect on the property of lignin/styrene-butadiene rubber composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 45759. 10.1002/app.45759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C.; Nasrollahzadeh M.; Sajjadi M.; Maham M.; Luque R.; Puente-Santiago A. R. Benign-by-design nature-inspired nanosystems in biofuels production and catalytic applications. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2019, 112, 195–252. 10.1016/j.rser.2019.03.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baig R. B. N.; Varma R. S. Copper on chitosan: a recyclable heterogeneous catalyst for azide-alkyne cycloaddition reactions in water. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 1839–1843. 10.1039/c3gc40401c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baig R. B. N.; Varma R. S. Magnetically retrievable catalysts for organic synthesis. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 752–770. 10.1039/c2cc35663e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrollahzadeh M.; Issaabadi Z.; Sajadi S. M. Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticle supported ionic liquid for green synthesis of antibacterially active 1-carbamoyl-1-phenylureas in water. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 27631–27644. 10.1039/c8ra04368j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoli M.; Gaudino E. C.; Cravotto G.; Tabasso S.; Baig R. B. N.; Colacino E.; Varma R. S. Microwave-assisted reductive amination with aqueous ammonia: sustainable pathway using recyclable magnetic nickel-based nanocatalyst. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 5963–5974. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b06054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baig R. B. N.; Verma S.; Varma R. S.; Nadagouda M. N. Magnetic Fe@gC3N4: a photoactive catalyst for the hydrogenation of alkenes and alkynes. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 1661–1664. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b01610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gawande M. B.; Branco P. S.; Varma R. S. Nano-magnetite (Fe3O4) as a support for recyclable catalysts in the development of sustainable methodologies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 3371–3393. 10.1039/c3cs35480f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasir Baig R. B.; Varma R. S. Organic synthesis via magnetic attraction: benign and sustainable protocols using magnetic nanoferrites. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 398–417. 10.1039/c2gc36455g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrollahzadeh M.; Issaabadi Z.; Tohidi M. M.; Sajadi S. M. Recent progress in application of graphene supported metal nanoparticles in C-C and C-X coupling reactions. Chem. Rec. 2018, 18, 165–229. 10.1002/tcr.201700022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou J.; Saha A.; Bennett-Stamper C.; Varma R. S. Inside-out core-shell architecture: controllable fabrication of Cu2O@Cu with high activity for the Sonogashira coupling reaction. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 5862–5864. 10.1039/c2cc31577g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feizi Mohazzab B.; Jaleh B.; Issaabadi Z.; Nasrollahzadeh M.; Varma R. S. Stainless steel mesh-GO/Pd NPs: catalytic applications of Suzuki-Miyaura and Stille coupling reactions in eco-friendly media. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 3319–3327. 10.1039/c9gc00889f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Modak S.; Gangwar M. K.; Nageswar Rao M.; Madasu M.; Kalita A. C.; Dorcet V.; Shejale M. A.; Butcher R. J.; Ghosh P. Fluoride-free Hiyama coupling by palladium abnormal N-heterocyclic carbene complexes. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 17617–17628. 10.1039/c5dt02317c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen C.; Shen H.; Yang M.; Xia C.; Zhang P. A novel D-glucosamine-derived pyridyl-triazole@palladium catalyst for solvent-free Mizoroki-Heck reactions and its application in the synthesis of Axitinib. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 225–230. 10.1039/c4gc01606h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chemler S. R.; Trauner D.; Danishefsky S. J. The B-alkyl Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction: development, mechanistic study, and applications in natural product synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 4544–4568. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torborg C.; Beller M. Recent applications of palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions in the pharmaceutical, agrochemical, and fine chemical industries. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 3027–3043. 10.1002/adsc.200900587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R.; Buchwald S. L. Palladium-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions employing dialkylbiaryl phosphine ligands. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1461–1473. 10.1021/ar800036s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S.; Nolan S. P.; Szostak M. Well-defined palladium (II)-NHC precatalysts for cross-coupling reactions of amides and esters by selective N-C/O-C cleavage. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2589–2599. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shendage S. S.; Patil U. B.; Nagarkar J. M. Electrochemical synthesis and characterization of palladium nanoparticles on nafion-graphene support and its application for Suzuki coupling reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 3457–3461. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.04.092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Firouzabadi H.; Iranpoor N.; Ghaderi A.; Ghavami M.; Hoseini S. J. Palladium nanoparticles supported on aminopropyl-functionalized clay as efficient catalysts for phosphine-free C-C bond formation via Mizoroki-Heck and Suzuki-Miyaura reactions. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2011, 84, 100–109. 10.1246/bcsj.20100219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karami K.; Ghasemi M.; Haghighat Naeini N. Palladium nanoparticles supported on polymer: an efficient and reusable heterogeneous catalyst for the Suzuki cross-coupling reactions and aerobic oxidation of alcohols. Catal. Commun. 2013, 38, 10–15. 10.1016/j.catcom.2013.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrollahzadeh M.; Sajadi S. M.; Maham M. Green synthesis of palladium nanoparticles using Hippophae rhamnoides Linn leaf extract and their catalytic activity for the Suzuki-Miyaura coupling in water. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2015, 396, 297–303. 10.1016/j.molcata.2014.10.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dabiri M.; Lehi N. F.; Movahed S. K. Fe3O4@RGO@Au@C composite with magnetic core and Au enwrapped in double-shelled carbon: an excellent catalyst in the reduction of nitroarenes and Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling. Catal. Lett. 2016, 146, 1674–1686. 10.1007/s10562-016-1792-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Movahed S. K.; Shariatipour M.; Dabiri M. Gold nanoparticles decorated on a graphene-periodic mesoporous silica sandwich nanocomposite as a highly efficient and recyclable heterogeneous catalyst for catalytic applications. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 33423–33431. 10.1039/c5ra00062a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hajipour A. R.; Kalantari Tarrari M.; Jajarmi S. Synthesis and characterization of 4-AMTT-Pd(II) complex over Fe3O4@SiO2 as supported nanocatalyst for Suzuki-Miyaura and Mizoroki-Heck cross-coupling reactions in water. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2018, 32, e4171 10.1002/aoc.4171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amini M.; Tarassoli A.; Yousefi S.; Delsouz-Hafshejani S.; Bigdeli M.; Salehifar M. Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions in water using in situ generated palladium (II)-phosphazane complexes. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2014, 25, 166–168. 10.1016/j.cclet.2013.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi B.; Mansouri F.; Vali H. A highly water-dispersible/magnetically separable palladium catalyst based on a Fe3O4@SiO2 anchored TEG-imidazolium ionic liquid for the Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction in water. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 2587–2596. 10.1039/c3gc42311e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; Li X.; Wang X.; Qiu J. Palladium-catalyzed ligand-free and efficient Suzuki-Miyaura reaction of N-methyliminodiacetic acid boronates in water. Turk. J. Chem. 2015, 39, 1208–1215. 10.3906/kim-1505-97. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jana S.; Haldar S.; Koner S. Heterogeneous Suzuki and Stille coupling reactions using highly efficient palladium(0) immobilized MCM-41 catalyst. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 4820–4823. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.05.098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay K.; Dey R.; Ranu B. C. Shape-dependent catalytic activity of copper oxide-supported Pd(0) nanoparticles for Suzuki and cyanation reactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 3164–3167. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.01.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Senapati K. K.; Roy S.; Borgohain C.; Phukan P. Palladium nanoparticle supported on cobalt ferrite: An efficient magnetically separable catalyst for ligand free Suzuki coupling. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2012, 352, 128–134. 10.1016/j.molcata.2011.10.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K.-i.; Kan-no T.; Kodama T.; Hagiwara H.; Kitayama Y. Suzuki cross-coupling reaction catalyzed by palladium-supported sepiolite. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 5653–5655. 10.1016/s0040-4039(02)01132-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Metin Ö.; Ho S. F.; Alp C.; Can H.; Mankin M. N.; Gültekin M. S.; Chi M.; Sun S. Ni/Pd core/shell nanoparticles supported on graphene as a highly active and reusable catalyst for Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction. Nano Res. 2013, 6, 10–18. 10.1007/s12274-012-0276-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon T. H.; Cho K. Y.; Baek K.-Y.; Yoon H. G.; Kim B. M. Recyclable palladium–graphene nanocomposite catalysts containing ionic polymers: efficient Suzuki coupling reactions. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 11684–11690. 10.1039/c6ra26998b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y.-S.; Lin X.-Y.; Hao J.; Xu H.-J. Pd–Co bimetallic nanoparticles supported on graphene as a highly active catalyst for Suzuki–Miyaura and Sonogashira cross-coupling reactions. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 5249–5253. 10.1016/j.tet.2014.05.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.