Abstract

While the Western diet has evolved to become increasingly high in saturated fat, cholesterol, protein, sugar, and salt intake, nutrition education and training of health care professionals to counsel their patients on the hazards of such a diet has trailed behind. Primary care physicians have an opportunity to bridge the gap by providing nutrition and dietary counseling as key components in the delivery of preventive services. Increasing research points to the value of a whole-foods plant-based diet in combating chronic disease, yet the knowledge of health professionals about the topic is comparable to that of the general public. This education crisis is apparent in medical training with restricted time for dedicated lectures on nutrition, physical activity, restorative sleep, emotional well-being, and avoidance of risky substance use. Together, educators and learners are valuable catalysts for culture change in medical education, training, and clinical practice. Barriers to physician ability to counsel about lifestyle are many, but one that stands out is lack of training and comfort with counseling. This has implications for the training of health care professionals. American College of Lifestyle Medicine has a committee, Professionals in Training, composed of interprofessional and multidisciplinary students, residents, and fellows nationally and worldwide who are committed to expanding exposure to lifestyle medicine and implementation of lifestyle medicine in parallel curriculum and personal care.

Keywords: lifestyle medicine, lifestyle medicine interest groups, nutrition education, counseling, health behavior, primary care, student, learning, curriculum, public health policy, leadership

‘Medical societies have recognized the importance of lifestyle medicine interventions.’

Background

Despite lifestyle interventions being first-line treatments for many noncommunicable diseases, lifestyle medicine is underutilized in clinical practice and underemphasized in medical training.1 Eating a diet rich in plants can help reduce the risk of many leading causes of illness and death, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, some cancers, and obesity.2,3 Primary care physicians have an average length time of about 10 seconds discussing nutrition.4 Limited time spent on nutritional counseling is likely due to rising demands to reach quality measures and restricted financial reimbursement.5 In contrast, the WATCH study demonstrated the overwhelming majority of internists (94%) value physician-delivered nutrition counseling. However, less than 25% of physicians feel adequately trained to discuss dietary habits.6 After receiving 3 hours of nutritional training, doctors intentionally spent 5 more minutes to counsel on nutrition and exercise during a primary care visit resulting in weight loss and lower LDL.6

The United States has a federal requirement of 25 hours of nutritional education during medical curricula. Only 1 in 4 American medical schools meet this requirement.7 Internationally, Polish medical students reported an average of 6 hours total of dedicated lectures on nutrition and preventative health.8 While there is a 10% increase from 19% to 30% for students to residents in preparedness to discuss diet with patients, in other studies, students reported they were less confident in skills related to nutritional composition of foods, general food knowledge, and explaining antioxidant-rich produce.9,10 In more recent survey data published in the American Journal of Medicine, 22% physicians recalled receiving no nutrition education and 35% recall receiving a single lecture or section of a single lecture.11 These pooled physicians were 58% American and 30% from Asia and Europe who noted no memory of nutrition didactics.11 This gap in nutrition education has real consequences, as the medical community is underequipped to deliver lifestyle counseling. Several studies have surveyed primary care physicians and medical students’ attitudes toward nutrition in patient care, in which both groups recognize the importance of providing nutritional treatment options in conjunction with the need to integrate nutritional care into medical education.7-11

Medical societies have recognized the importance of lifestyle medicine interventions. American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) has taken the lead and revised their 2017 hypertension guidelines to expand their focus on lifestyle recommendations to prevent and manage hypertension.12 There is great need for medical curricula and training reform that invests time spent on comprehensive didactics on lifestyle modifications and behavior change theory.12

Physicians similarly suffer with regard to providing physical activity counseling to patients. Physician surveys report perceiving themselves as ineffective in their physical activity counseling.13 Physical activity prescription is a lifestyle medicine clinical skill that can easily be implemented in physician training. After receiving 1-day training for Exercise is Medicine Canada, physicians demonstrated increase physical activity knowledge, confidence, and counseling behaviors and lessen identified barriers.14 In addition, the frequency of physicians providing written exercise prescriptions increased from 20% to 74%.15 Exercise prescriptions given by physicians demonstrated increased patient activity at 6 and 12 months, and long-term quality of life at 2 year follow-up.15

Delivery of lifestyle medicine treatment to manage chronic disease is optimally delivered through behavior change techniques, exercise and nutrition prescriptions, nutritional counseling, stress management, and personal connection. In a 2010 commentary in JAMA on physician competencies for prescribing lifestyle medicine, Lianov and colleagues identified 15 competencies.16 These included “Assessment Skills” such as “Lifestyle Medicine Vital Signs,” including tobacco use, alcohol consumption, diet, physical activity, body mass index, stress level, sleep, and emotional well-being.16 They also included management skills such as providing “lifestyle medicine prescriptions” to address these vital signs. To fill these gaps, the expert panel recommended several measures, including development of curricula, training materials, and evaluation methods.16

Introduction

Because of this large gap in medical education, many eager students turn to outside sources and learn through other means such as internet search, peer-reviewed scientific journals, webinars, national medical society conferences, health-related documentaries, books authored by lifestyle medicine experts, podcasts, and student-led organizations such as the American College of Lifestyle Medicine Professionals in Training (ACLM PiT) and Lifestyle Medicine Interest Groups (LMIGs). ACLM PiT and LMIGs can render updated, evidence-based, and consistent educational resources, delivering an “alternate training pathway.” These student-led, preprofessional groups can introduce students to lifestyle medicine as a clinical discipline. They serve directly to educate students about lifestyle medicine, expose students to lifestyle medicine in clinical and community setting, and increase awareness of lifestyle medicine on their respective campuses. The first student-led groups focused on lifestyle medicine were active in the 1990s at Loma Linda University.5 Historically, LMIGs have created parallel curriculum that cover lifestyle medicine concepts initiated by Harvard Medical School in 2009 with the goal to train medical students to provide doctor-directed preventive care.17 Harvard Medicine School LMIG defines doctor-directed preventative care as “To empower the next generations of physicians to tackle lifestyle related illness in an effort to reduce morbidity and mortality from coronary artery disease, diabetes, stroke, metabolic syndrome, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle.”17 Health profession students and residents can learn lifestyle medicine skills by participating and leading student wellness programs, fitness programing, culinary medicine workshops and courses, yoga, meditation, emotional well-being sessions at their institutions, local community, and their personal homes. Applying lifestyle medicine principles are basic skills for future health care providers that LMIGs can model for their fellow peers.

JAMA recognizes lifestyle medicine as an emerging field for primary care and preventative care physicians and encourages the implementation of lifestyle medicine curricula in undergraduate medical education, graduate medical education, and continuing medical education, which has improved self-perceived attitude, knowledge, and confidence toward prescribing lifestyle medicine prescriptions, behavior counseling, and self-care.16 Exercise is Medicine (EIM) launched by the American College of Sports Medicine (2007) and the American Medical Association is a transformative approach to exercise implementation in educational and clinical settings. EIM encourages health providers to assess physical activity as a vital sign and to include exercise in patient treatment plans.18 The EIM Educational Committee released milestone physical activity recommendations for graduate medical education: (a) knowledge, (b) tools, (c) skills, and (d) self-care.18 The American College of Lifestyle Medicine developed landmark lifestyle medicine competencies in education comprising nutrition, exercise, stress management, and smoking cessation, which evolved to also include stress resiliency, behavioral change, and emotional well-being.18 Lifestyle medicine focus areas are in leadership, knowledge, assessment skills, management skills, and the use of office and community support.16,18

To reduce the problem of health professionals ill-equipped to deliver lifestyle medicine interventions, interprofessional lifestyle medicine training is needed. There has been some momentum gained toward filling this need. Lifestyle Medicine Education Collaborative (LMed) founded in 2013 includes key stakeholders who amplify lifestyle medicine curricula.19 Participants include medical student deans, medical students, content experts, and representatives of professional associations, government agencies, accreditation agencies, and national assessment boards.18,19 Multiple initiatives and paradigm shifts in medical education and training have elevated lifestyle medicine as a burgeoning specialty recognized by the Association of American Medical Colleges.20

An analytic review on lifestyle medicine education emphasized the “Concentric Circle of Influence” as an impactful and sustainable reach in education. The “Concentric Circle of Influence” includes the core as lifestyle medicine medical school faculties and expands to other circumferential areas of influencers in medical schools, other health professions schools, and entire universities.19 LMIGs play a unique influence on all mentioned platforms and have organically grown to a multidisciplinary and multilevel spread, from allopathic and osteopathic medical schools, nursing, physical therapy and occupational therapy, pharmacy, and other allied health schools. LMIGs have evolved to reach various education spheres as well, from undergraduate prehealth programs, graduate schools of medicine and public health, medical residents and resident fellows. LMIGs encourage all involvement from cross health care specialties. Additionally, “Other professions such as law, business, design, industry, and engineering should be part of this reform and should learn about healthy environments during their training.”19

Value-Based Learning

Students persistently seek out meaningful contributions to health care teams. Often, they are shadows who closely follow their supervisors awaiting learning opportunities. In 2016, 32 US medical schools in the American Medical Association’s (AMA’s) Accelerating Change in Education explored value-added medical education for students and their roles in care delivery systems.21 Students are positioned with more time to engage in patient education and counseling, such as health coaching, creating engaging health educational materials, and motivational interviewing.22 Educating students with lifestyle medicine counseling skills can enhance their learning experience, additionally deliver quality patient care.

Self-Care and Health Transformations

“Healthy persons make healthy doctors” is the cornerstone for lifestyle medicine. Several studies have demonstrated that physicians who themselves exercise and practice self-care are more likely and more effectively at counseling their patients to do the same.23 This strategy has been implemented by LMIGs across the country through the creation of student led fitness groups, yoga classes, educational walking activities partnered with “Walk with the Doc,” and student-led lectures emphasizing the premise of “Exercise Is Medicine.” Rutgers New Jersey Medical School Lifestyle Medicine Interest Group is an incredibly active student organization that hosts various student wellness activities for medical students.24 The LMIG initiatives at Rutgers includes culinary medicine workshops, high-intensity interval training workouts, and yoga and meditation sessions.24 Additionally, the group hosts community service projects such as the lifestyle medicine course for high schoolers and a Walk with a Future Doc chapter to encourage active lifestyle among the Newark community.24 Ohio University Heritage College of Medicine LMIG hosts a parallel curriculum, such as lifestyle medicine educational series, plant-based culinary classes, and yoga and tai chi. University of Southern California hosts LMIG lunch time lecture series and monthly “Walk with the Doc” programs.24 These lifestyle medicine–oriented formalized activities raise the importance of self-care during healthcare training and model student wellness and healthier behaviors.

Furthermore, participating in lifestyle medicine focused curriculum has shown improvement of student health dietary choices. Surveyed results demonstrated after completing a preventive medicine and nutrition (PMN) course, 137 Harvard Medical students’ confidence in their ability to assess and counsel about diet and exercise significantly improved (P < .001). Additionally, there was a decrease in students’ self-reported consumption of saturated fat (P = .002) and trans fatty acids (P < .001) with a 72% perceived improvement in students’ diet.25

Student Leadership

Young health professionals in training have innocent and fresh perspectives but they also are historically effective advocates for cultural shifts and change. They bring enthusiasm, innovation, and can rally for health care education reform for lifestyle medicine. Students are idea generators and spread new ideas rapidly amongst their peers and other social circles.22 Students have access to other learners and experts in their own or other fields and can accelerate culture change through novel insight. Students can undertake research projects serving as meaningful learning. There are 106,000 medical students as future doctors poised to make great differences in their patient population, social sphere, and the general public. A total of 175 allopathic and osteopathic medical schools in the United States are training grounds for substantial and sustainable change in health educational reform. PiT and LMIG students and residents have contributed to well recognized and awarded lifestyle medicine scholarly projects and research. University of Utah, LMIG student leader James E Gardner, and faculty adviser Dr. Amy Locke MD, FAAFP, facilitated a variety of parallel curriculum including interactive lunch time didactic sessions about plant-based nutrition, mindful eating, and mindfulness for stress reduction.26 At Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, lifestyle medicine student champion, Elainee Poling, and faculty advisers Dr. Victoria Lucia, PhD, and Dr. Jamie Hope, MD, propelled lifestyle medicine into the classroom and clinical lifestyle medicine by increasing visibility by hosting unique and comprehensive events such as “Nutrition and the Elderly” and Lifestyle Medicine Week.”26 Alyssa Abreu along with champion faculty adviser, Dr. Mark Faries, PhD, have led other health professional students, such as kinesiology and nursing.26 They increased lifestyle medicine exposure by hosting lifestyle medicine workshops, cooking classes with lessons on food labels, smart grocery shopping and plant-based myths, and exercise classes of circuit-style body weight training and yoga.27

Community, Networks, Mentorship, and Research

Students are brilliant users of technology and have other nonmedical-related skill sets acquired by former work experience or other advanced degrees. They offer unique problem solving and technological support with internet navigation, web-based application, social media, and smart phones. They are on the cutting edge of an ever-changing technology landscape.22 Since such technology is developed by and targeted toward younger audience, learner-focused strategies that promote educator-learner partnership can powerfully create sustainable lifestyle medicine communities, networks, and mentorship. There are nearly 25 active LMIGs domestically in the United States and globally to date. Students can plant seeds of change through creative and innovative student led lifestyle medicine campus and community programs, social media postings on lifestyle medicine programs, and designing engaging educational material. LMIGs globally have developed plant-based pop-ups and offered plant-based culinary workshops, such as at the Medical University of Warsaw LMIG International. Medical student Alijca Baska and faculty adviser Dr. Daniel Sliz, MD, PhD, developed the first LMIG in Poland, “Lifestyle Medicine Scientific Club” who hosted a well-attended (350 participants) National Lifestyle Medicine Congress.27 PiT and LMIGs can draw positive attention and gain traction with faculty and students LMIGs at their local institutions. University of North Texas Health Center’s (UNTHSC) lifestyle medicine faculty Dr. Jenny Lee, PhD, MPH, along with current psychiatry resident physician Paresh Jaini have worked together on studying epigenetic changes underlying the efficacy of lifestyle interventions in the context of depression. Dr. Lee mentors 2 Preventative and Lifestyle Medicine Interest Groups (PLMIG); in addition, she provides lifestyle medicine research student mentorship.27

Engage, Imagine, and Align

Training the next wave of clinicians calls for educational innovation, scholarship, and leadership. The University of California San Francisco created the Health Professions Education (HPE) Pathway for medical students, residents, and fellows as well as learners from other health professional schools, which was designed to address how learners learn, their level of seeking and engaging in learning, and their attitudes and beliefs as a learner.28 The HPE Pathway is an illustration and possible evolution of the current role of LMIG within ecosystem of health professions school. The HPE Pathway applied 3 strategies of (a) engagement, (b) imagination, and (c) alignment, which resulted in “engagement with the educator community of practice, confirmed their career aspirations (imagination), joined an educator-in-training community (engagement/imagination), and disseminated via scholarly meetings and peer-reviewed publications (alignment).”28 A total of 117 HPE Pathway participants from 2009 to 2014 revealed overall positive impacts on learner career development. Hence, learners interested in the emerging field of lifestyle medicine would benefit to a similar model and lifestyle medicine interest groups can expand their role in learner identity formation in order to support their eager lifestyle medicine passions throughout their career developmental stages. While many medical students do not have access to this innovative program, ACLM PiT and LMIGs are similar to educator-in-training community in the HPE pathway that provide imagination and engagement by partnering with students who are seeking worthwhile learning experiences. This model of dissemination within the confines of the education system can be the next step for ACLM PiT and LMIGs.

Professionals in Training Mission and Objectives

In the true spirit of the Hippocratic Oath, ACLM’s PiT members recognize the vital need to identify and eradicate the cause of disease, as opposed to simply prescribing pills and procedures. PiT members are committed to their “first, do no harm” oath as they immerse themselves in specialized lifestyle medicine training, so they are equipped to be on the forefront of an emerging value and outcome-based system of healthcare delivery. As young trainees, the hope is to develop the skills and knowledge to effectively prevent, treat, and reverse chronic disease using evidence-based practices.29

The ACLM PiT mission (Figure 1) is

To advance the Lifestyle Medicine movement by providing students and trainees across all healthcare fields with opportunities in education, leadership, scholarship, mentoring, and networking to support the development and sustainability of Lifestyle Medicine Interest Groups (LMIGs) on all universities, health professions campuses, and residency training programs worldwide.29

Figure 1:

Core values of American College of Lifestyle Medicine Professionals in Training

The ACLM PiT mission empowers trainees in a 2-fold approach:

- To be a champion/leader in lifestyle medicine at the forefront of the changing paradigm of effective disease management

- Learn about the foundational principles of lifestyle medicine

- Learn about the clinical application of lifestyle medicine interventions in chronic disease such as metabolic syndrome, hypertension, diabetes, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- Learn about the landmark studies and evidence supporting lifestyle medicine principles

- Learn about how preventive medicine, functional medicine, and integrative medicine as they relate to lifestyle medicine

- To bring lifestyle medicine back to one’s home community and/or school institution, improving the quality of life for the people that you care for

- Demonstrate lifestyle medicine’s value to students, as well as to seasoned practitioners

- Inspire the next generation of lifestyle medicine leaders by seeding novel lifestyle medicine projects and implementation into didactics

- Spread lifestyle medicine awareness

ACLM Annual Conference

ACLM PiT historically has a growing presence at the ACLM annual meeting for lifestyle medicine lectures, networking, and immersion experience. Under the umbrella of ACLM, health professionals in training from across the globe intently seek other like-minded individuals. It is the authors’ experience that most trainees report an overall sense of isolation at their institution and have a substantial need to partner with other health professional trainees and potential mentors. PiT annually hosts a Mixer with lifestyle medicine national leaders who volunteer their personal and professional lifestyle medicine journey. At the 2018 ACLM Conference, we nearly doubled our attendance and had key leaders from previous and current ACLM Executive Board Members. In roundtable discussions, small groups were organically created and trainees had an opportunity to ask individualized questions and to develop mentor-mentee relationships. ACLM Conference provides a positively engaging platform for PiT to facilitate a valuable sense of community and support for trainees worldwide.

Surveyed health professionals in training noted,

“I had a great experience in these events. The LMIG workshop gave me an opportunity to connect with other professionals and learned about how they incorporate Lifestyle Medicine in their workplace. Also the PIT 5K Run helped me to enjoy the nature, experience the benefits of exercise, and gain a genuine camaraderie with the PIT board and committee.” (Anonymous health care trainee)

“The fact that PiT is a thing at all is something I am overjoyed about. It was so great to stop by the table every once in awhile and discuss LM/health care reform with people closer to my age.” (Anonymous health care trainee)

Annual PiT 5K Run

PiT has partnered with ACLM to provide attendees an opportunity to have an organized activity for physical activity after conference daytime events. Traditionally, participants ranged in age and experience, ranging from beginner walk-jog to experienced competitive athletes. This 5K Run is one of the favorites commented by both attendees, conference speakers and ACLM board members. This event continues to raise the bar and models health professionals who prioritize their health, physical exercise, and wellness despite the hustle of conference activities.

LMIG Workshop

Annually, PiT host an LMIG Workshop for trainees, faculty, and administrators (Table 1). Creating LMIGs within health profession schools and training programs serves as a method to increase awareness and understanding of lifestyle medicine at the student and trainee level. LMIGs unite students, interns, residents, and fellows across all health care fields and medical specialties worldwide. The workshop provides attendees with open discussion between trainees and health professionals to help facilitate hand-to-hand partnerships and aid in idea generation for LMIGs.

Table 1.

American College of Lifestyle Medicine Professionals in Training Conference Workshop.

| Lifestyle Medicine Interest Group Workshop Objectives27 |

|---|

| • Describe the mission of a Lifestyle Medicine Interest Group

(LMIG). • Present the current state of LMIGs across the country and showcase examples of LMIGs. • Explain how to create an LMIG at your training program. • Address common challenges and pitfalls experienced during the creation and maintenance of an LMIG. • Discuss the support and materials provided by the ACLM Professionals in Training Board for LMIGs. • Highlight opportunities for LMIGs and trainees offered through the ACLM Professionals in Training. |

Call to Action

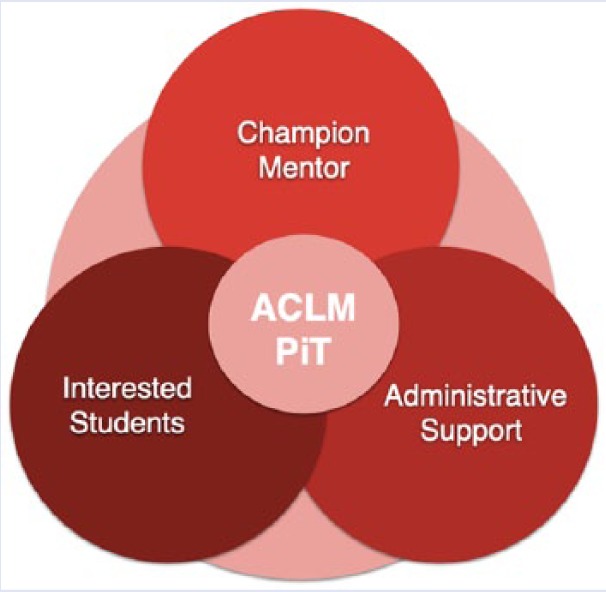

All professionals of any level and trainee/student of any field can develop a LMIG to contribute to the lifestyle medicine movement. The Harvard Medical School Lifestyle Medicine Interest Group (HMS LMIG) first developed a suggestive model for the application of HMS LMIG to other medical schools that include (a) a champion mentor who has a strong background in lifestyle medicine; (b) interested students who are strong lifestyle medicine student leaders; (c) recognition from medical student government, elective board, or program activities; and (d) lifestyle medicine syllabus based on lifestyle medicine competencies.19ACLM PiT recently participated in the ACLM Webinar series titled “How to Expand Lifestyle Medicine Interest Groups to Unite Professionals in Training” and highlighted that ACLM PiT and LMIGs flourish when there are 3 contributing roles: Champion Mentor, Administrative Support, and Interested Support.24 The Champion Mentor can connect with the ACLM, join the ACLM Membership, and optimize their personal lifestyle (Figure 2).24 Champion mentors have visible roles in the academic community and can identify and reach interested students, lead a lifestyle medicine lecture on “What Is Lifestyle Medicine?,” serve as mentor and/or advisory role for an LMIG.24 Champion mentors are typically connected with administration and can help leverage support and identify funding.24 Administrative leaders have a vital role and organizational perspective, who can connect interested students with faculty members, integrate LMIG with student wellness programs, and connect ACLM to current student organizations with similar missions, such as Exercise is Medicine, Walk with a Doc chapters, and other Fitness and Nutrition groups.24 Lifestyle medicine interested trainees can engage with their like-minded peers, identify a faculty mentor through ACLM physician directory, launch a new LMIG, develop student leadership roles, and reach out to the ACLM PiT executive board.24

Figure 2.

Key players in lifestyle medicine interest groups creation.24

Join the Lifestyle Medicine Movement

We encourage healthcare professionals to reach out to your graduate alumni office and inquire how to become a mentor or advisor of a lifestyle medicine interest group. We encourage trainees to visit your student affairs office to learn how to initiate a new LMIG or join an existing one.24

ACLM PiT Website has supplement resources that can springboard your LMIG.

ACLM Course Syllabus

“What is Lifestyle Medicine?”

“LMIG Starter Kit”

“LM Article Library”

“LMIG Leader Presentations”

“Handouts & Infographics”

“Past LMIG Event Ideas (by school)”

Conclusion

Physicians and health professionals have potential to address the lifestyle medicine deficiency in health professional education. Patients highly trust their healthcare providers to provide nutritional counseling and recommend practical advice regarding dietary recommendations.8 It has been estimated that US Medical Schools have a national average of 19.6 hours of nutrition teaching.19 However, lifestyle medicine education in medical schools today is composed of superficial topics, such as calculation of body mass index, waist-hip ratio, significance of moderate weight loss with type 2 diabetes, and importance of decreasing alcohol consumption.30 Comprehensive and practical lifestyle medicine principles and lifestyle behavior counseling are tremendously lacking in medical curricula and clinical training. This is a real medical gap that leads to apparent challenges in performing a lifestyle assessment and relaying effective lifestyle medicine recommendations to patients.9,10

Lifestyle medicine is foundational for prevention and reversal of many chronic diseases. The current pandemic of noncommunicable diseases calls for a paradigm shift from treating the disease to treating the cause.31,32 The aim of lifestyle medicine is to prescribe lifestyle medicine as first line therapy and use medication as supplement.33 Lifestyle medicine creates an opportunity for health professionals in training to gain competence in evidence-based nutritional and physical activity recommendations, tobacco and substance cessation counseling, social determinants of health, health literacy, behavioral interventions, and emotional well-being. Educators and learners in health care have the potential to increase awareness of lifestyle medicine through multiple avenues, including the development of lifestyle medicine interest groups in the health professions schools. Student and resident learners are mediums for change. Trainees are great change agents in leadership, advocacy, and scholarship.34 They are not only great supporters of the lifestyle medicine movement, but they are at the forefront running toward change through their well-rounded skills, high spirited inquiries, and progressive leadership roles. Trainees and health professionals are able to support lifestyle medicine by supporting and creating LMIGs at any type of health professions school and at any level of training. There have been recent calls for professional and scientific societies to collaborate to support the dissemination and implementation of lifestyle counseling approaches. Supporting LMIGs can provide one such avenue for systems change.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the 2018-2019 Executive Board officers of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine’s Professionals in Training Committee. We acknowledge Paresh Jaini, DO, Richard Wolferz, MS3, Lucas Shanholtzer, MD, who contributed to the PiT Mission Statement, PiT Webinar, and ACLM PiT Student/training website content. We would like to acknowledge all previous PiT Executive Board Members for their outstanding contributions, idea creation, and paving the way for health education reform.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This article is based on a workshop given at the Annual Meeting of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine 2018 in Indiana, IN.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

References

- 1. Katz DL. How to improve clinical practice and medical education about nutrition. AMA J Ethics. 2018;20:E994-E1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tuso PJ, Ismail MH, Ha BP, Bartolotto C. Nutritional update for physicians: plant-based diets. Perm J. 2013;17:61-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. Strategies to prevent obesity and other chronic diseases—the CDC guide to strategies to increase the consumption of fruits and vegetables. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/fandv_2011_web_tag508.pdf. Accessed April 5, 2019.

- 4. Eaton CB, Goodwin MA, Stange KC. Direct observation of nutrition counseling in community family practice. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:174-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clarke CA, Frates J, Frates EP. Optimizing lifestyle medicine health care delivery through enhanced interdisciplinary education. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;10:401-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ockene IS, Hebert JR, Ockene JK, et al. Effect of physician-delivered nutrition counseling training and an office-support program on saturated fat intake, weight, and serum lipid measurements in a hyperlipidemic population: Worcester Area Trial for Counseling in Hyperlipidemia (WATCH). Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:725-731. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.7.725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vetter ML, Herring SJ, Sood M, Shah NR, Kalet AL. What do resident physicians know about nutrition? An evaluation of attitudes, self-perceived proficiency and knowledge. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27:287-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Powell M, Zeisel SH. Nutrition in Medicine: Nutrition Education for Medical Students and Residents. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25(5):471-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shai I, Shahar D, Fraser D. Attitudes of physicians and medical students toward nutrition’s place in patient care and education at Ben-Gurion University. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2001;14:405-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Crowley J, Ball L, Han DY, Arroll B, Leveritt M, Wall C. New Zealand medical students have positive attitudes and moderate confidence in providing nutrition care: a cross sectional survey. J Biomed Educ. 2015;2015:259653. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aggarwal M, Devries S, Freeman AM, et al. The deficit of nutrition education of physicians. Am J Med. 2018;131:339-345. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Janke EA, Richardson C, Schneider KL; Society of Behavioral Medicine Executive Committee. Beyond pharmacotherapy: lifestyle counseling guidance needed for hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:195-196. doi: 10.7326/M18-2361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tulloch H, Fortier M, Hogg W. Physical activity counseling in primary care: who has and who should be counseling? Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64:6-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fowles JR, O’Brien MW, Solmundson K, Oh PI, Shields CA. Exercise is Medicine Canada physical activity counseling and exercise prescription training improves counselling, prescription, and referral practices among physicians across Canada. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2018;43:535-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rödjer L, Jonsdottir IH, Börjesson M. Physical activity on prescription (PAP): self-reported physical activity and quality of life in a Swedish primary care population, 2-year follow-up. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2016;34:443-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lianov L, Johnson M. Physician competencies for prescribing lifestyle medicine. JAMA. 2010;304:202-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pojednic R, Frates E. A parallel curriculum in lifestyle medicine. Clin Teach. 2017;14:27-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Trilk JL, Muscato D, Polak R. Advancing lifestyle medicine education in undergraduate medical school curricula through the Lifestyle Medicine Education Collaborative (LMEd). Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;12:412-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Polak R, Pojednic RM, Phillips EM. Lifestyle medicine education. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2015;9:361-367. doi: 10.1177/1559827615580307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Howard B. Five emerging medical specialties you’ve never heard of—until now. https://news.aamc.org/medical-education/article/five-emerging-medical-specialties/. Published July 24, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2019.

- 21. American Medical Association. Accelerating change in medical education. https://www.ama-assn.org/education/accelerating-change-medical-education. Accessed February 20, 2019.

- 22. Gonzalo JD, Dekhtyar M, Hawkins RE, Wolpaw DR. How can medical students add value? identifying roles, barriers, and strategies to advance the value of undergraduate medical education to patient care and the health system. Acad Med. 2017;92:1294-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Florindo AA, Brownson RC, Mielke GI, et al. Association of knowledge, preventive counseling and personal health behaviors on physical activity and consumption of fruits or vegetables in community health workers. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mondala M, Wolferz R. Upcoming ACLM Educational Webinars. How to expand lifestyle medicine interest groups to unite professionals in training. https://www.lifestylemedicine.org/Webinars. Accessed April 5, 2019.

- 25. Conroy MB, Delichatsios HK, Hafler JP, Rigotti NA. Impact of a preventive medicine and nutrition curriculum for medical students. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:77-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stiegmann RA, Abreu A, Gardner JE, Hipple JM, Poling PE, Frates EP. Planting the seeds of change: growing lifestyle medicine interest groups with the Donald A. Pegg Award. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2017;11:443-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jaini PA, Stiegmann RA, Barrera A, et al. Nurturing the seeds of change: strengthening the lifestyle medicine movement with the Donald A. Pegg Student Leadership Award. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2018;12:476-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen HC, Wamsley MA, Azzam A, Julian K, Irby DM, O’Sullivan PS. The health professions education pathway: preparing students, residents, and fellows to become future educators. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29:216-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. American College of Lifestyle Medicine. Student/trainee. https://lifestylemedicine.org/ACLM/About/Student___Trainee/ACLM/About/Student_Trainee/Student_Trainee.aspx?hkey=8876d3da-5fa6-4f68-a005-86eef8dd91cc. Accessed February 21, 2019.

- 30. Schoendorfer N, Gannaway D, Jukic K, Ulep R, Schafer J. Future doctors’ perceptions about incorporating nutrition into standard care practice. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017;36:565-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nowson CA, O’Connell SL. Nutrition knowledge, attitudes, and confidence of Australian General Practice Registrars. J Biomed Educ. 2015;2015:219198. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hyman MA, Ornish D, Roizen M. Lifestyle medicine: treating the causes of disease. Altern Ther Health Med. 2009;15:12-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kushner RF, Mechanick JI. Lifestyle medicine—an emerging new discipline. US Endocrinology. 2015;11:36-40. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Burk-Rafel J, Jones RL, Farlow JL. Engaging learners to advance medical education. Acad Med. 2017;92:437-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]