Abstract

Grapevine trunk diseases have become one of the main threats to grape production worldwide, with Diaporthe species as an emerging group of pathogens in China. At present, relatively little is known about the taxonomy and genetic diversity of Chinese Diaporthe populations, including their relationships to other populations worldwide. Here, we conducted an extensive field survey in six provinces in China to identify and characterize Diaporthe species in grape vineyards. Ninety-four isolates were identified and analyzed using multi-locus phylogeny. The isolates belonged to eight species, including three novel taxa, Diaporthe guangxiensis (D. guangxiensis), Diaporthe hubeiensis (D. hubeiensis), Diaporthe viniferae (D. viniferae), and three new host records, Diaporthe gulyae (D. gulyae), Diaporthe pescicola (D. pescicola), and Diaporthe unshiuensis (D. unshiuensis). The most commonly isolated species was Diaporthe eres (D. eres). In addition, high genetic diversity was observed for D. eres in Chinese vineyards. Haplotype network analysis of D. eres isolates from China and Europe showed a close relationship between samples from the two geographical locations and evidence for recombination. In comparative pathogenicity testing, D. gulyae was the most aggressive taxon, whereas D. hubeiensis was the least aggressive. This study provides new insights into the Diaporthe species associated with grapevines in China, and our results can be used to develop effective disease management strategies.

Keywords: novel species, new host record, network analysis, phylogeography, phomopsis

Introduction

In natural ecosystems, plant pathogens play important roles such as regulating host populations and host plant geographic and ecological distributions. Consequently, they can affect the availability of food sources to other living organisms (Lindahl and Grace, 2015). Most microbial pathogens have short generation times and large population sizes, which can result in high genetic variations and rapid adaptations to environmental stresses and to human-mediated factors such as fungicide resistance (Alberts et al., 2002; Lindahl and Grace, 2015). Hence, it is important to understand the genetic diversity and population variation of plant pathogens to develop sustainable control measures.

Grape is one of the most important fruit crops in China. China is the second largest grape-cultivating country and the top producer in the world (OIV, 2016). In 2016, the total grape cultivation area was estimated at 847 kha, and 14.5 million metric tons of fresh grapes were produced in China (OIV, 2016). Therefore, infectious diseases with significant risks to grape production have drawn broad attention from the grapevine industry. Grapevines are affected by several foliar diseases (Gadoury et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2017), fruit diseases (Daykin and Milholland, 1984; Hong et al., 2008; Greer et al., 2011; Jayawardena et al., 2015), and trunk diseases (Yan et al., 2013; Dissanayake et al., 2015a,b). Grapevine trunk diseases have drawn considerable attention, as these diseases affect the perennial parts of the vine and can limit grape production for many years (Yan et al., 2013, 2015).

The genus Diaporthe Nitschke., belongs to the family Diaporthaceae, and is typified by Diaporthe eres (D. eres) Nitschke (Senanayake et al., 2017). Following the nomenclature rules Rossman et al. (2014) proposed that the genus name Diaporthe over Phomopsis as it was introduced first, represents the majority of species. In earlier species names were given to Diaporthe taxa based on their host specificity. This resulted in over 100 names listed under the genus Diaporthe (http://www.indexfungorum.org/Names/Names.asp and http://www.mycobank.org). With advances in molecular techniques, multi-locus DNA sequence data together with morphological characteristics have been extensively used for the delimitation of Diaporthe species (Udayanga et al., 2011; Gomes et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2017). The internal transcribed spacer (ITS), translation elongation factor-1a (EF-1α), β-tubulin, partial histone H3 (HIS), calmodulin (CAL), genes are the most commonly used gene regions for molecular characterization (Udayanga et al., 2011; Gao et al., 2017; Guarnaccia et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018). Multiple studies have used different gene combinations to resolve the species boundaries in this genus (Udayanga et al., 2011, 2014a,b; Gao et al., 2017; Marin-Felix et al., 2019). Species belonging to genus Diaporthe are endophytes, pathogenic, and saprobic on wide range of hosts worldwide (Liu et al., 2015; Hyde et al., 2016; Marin-Felix et al., 2019). They are well-known pathogens on economically important crops (Udayanga et al., 2011). Several common disease among those are dieback on forest trees (Yang et al., 2018), leaf spots on tea (Guarnaccia and Crous, 2017), leaf and pod blights and seed decay on soybean (Udayanga et al., 2015), melanose, stem-end rot, and gummosis on Citrus spp. (Mondal et al., 2007; Udayanga et al., 2014a; Guarnaccia and Crous, 2017, 2018) and stem canker on sunflower (Muntañola-Cvetković et al., 1981; Thompson et al., 2011).

Phomopsis cane and leaf spot caused by Diaporthe species on grapevine is one of the most complex grapevine trunk diseases worldwide (Úrbez-Torres et al., 2013; Dissanayake et al., 2015a; Guarnaccia et al., 2018). The disease symptoms of Diaporthe Dieback include shoots breaking off at the base, stunting, dieback, loss of vigor, reduced bunch set, and fruit rot (Pine, 1958, 1959; Pscheidt and Pearson, 1989; Pearson and Goheen, 1994; Wilcox et al., 2015). In woods brown to black necrotic irregular-shaped lesions could be observed. Once clusters are infected rachis necrosis and brown, shriveled berries close to harvest could be observed (Pearson and Goheen, 1994). More than one Diaporthe species is frequently reported as causative agents from one country (Dissanayake et al., 2015a; Guarnaccia et al., 2018). Currently, 27 species have been identified as causal organisms of Diaporthe dieback in grape-producing countries worldwide (Mostert et al., 2001; Van Niekerk et al., 2005; Udayanga et al., 2011, 2014a,b; White et al., 2011; Baumgartner et al., 2013; Úrbez-Torres et al., 2013; Hyde et al., 2014; Dissanayake et al., 2015a; Guarnaccia et al., 2018; Lesuthu et al., 2019). Even though these species characterized under the one disease, disease symptoms, and aggressiveness are varying according to the species. Diaporthe ampelina (D. ampelina) has a long history as the most common and severe pathogenic species together with D. amygdali (Mostert et al., 2001; Van Niekerk et al., 2005). Diaporthe ampelina and Diaporthe kyushuensis (D. kyushuensis) are the causal agent of grapevine swelling arm (Kajitani and Kanematsu, 2000; Van Niekerk et al., 2005). Diaporthe perjuncta (D. perjuncta) and D. ampelina caused cane bleaching (Kuo and Leu, 1998; Kajitani and Kanematsu, 2000; Mostert et al., 2001; Van Niekerk et al., 2005; Rawnsley et al., 2006). Lesuthu et al. (2019) showed that D. ampelina, Diaporthe novem (D. novem), and Diaporthe nebulae (D. nebulae) as the most virulent species of Diaporthe associated with grapevines in South Africa. Diaporthe eres was found as a weak to moderate pathogen in several different studies (Kaliterna et al., 2012; Baumgartner et al., 2013). These results indicate the complexity and high species richness of Diaporthe associated with the grapevines. Up to now in China four Diaporthe species have been reported causing grapevine dieback (Dissanayake et al., 2015a). Those are D. eres, Diaporthe hongkongensis (D. hongkongensis), Diaporthe phaseolorum (D. phaseolorum), and Diaporthe sojae (D. sojae). Their taxonomic placements and pathogenicity under a controlled environment were also studied.

The study conducted by Guarnaccia et al. (2018) showed that species of Diaporthe also associated as endophytes on grapes as well. In that study they observed that Diaporthe bohemiae (D. bohemiae), which was isolated from grape was unable to induce lesions. In addition to grapevines, Diaporthe have been reported on broad range of hosts (Udayanga et al., 2011). However, the most important charter is the ability of endophytic Diaporthe species to be opportunistic pathogens. Huang et al. (2015) observed that some Diaporthe species associated with citrus in China shown to act as opportunistic plant pathogens. Diaporthe foeniculina (D. foeniculina) has been found as both endophyte and opportunistic pathogen on various herbaceous weeds, ornamentals, and fruit trees (Udayanga et al., 2014a; Guarnaccia et al., 2016). So far it is not confirmed the factor that driven into pathogenicity from endophytes either due to environmental changes or the reduction of host's defense. Therefore, further studies are required to understand this in both field level and genomic level.

However, the genetic diversity of Diaporthe spp. associated with Vitis spp., relationships among isolates from different geographical regions, and relationships among isolates from China and those from other countries were not investigated. Therefore, to expand our knowledge on these issues, we performed an extensive field survey to isolate and identify Diaporthe species associated with grapevine dieback in China. We reconstructed a phylogenetic tree for the genus Diaporthe. The present study analyzed the genetic diversity of Diaporthe species associated with grapevines in China and constructed haplotype networks for Diaporthe species from different geographical origins for the first time. Finally, we analyzed the relationship between Diaporthe species from European and Chinese grape vineyards, as Diaporthe dieback is becoming an emerging trunk disease in both regions (Guarnaccia et al., 2018).

Materials and Methods

Sampling and Pathogen Isolation

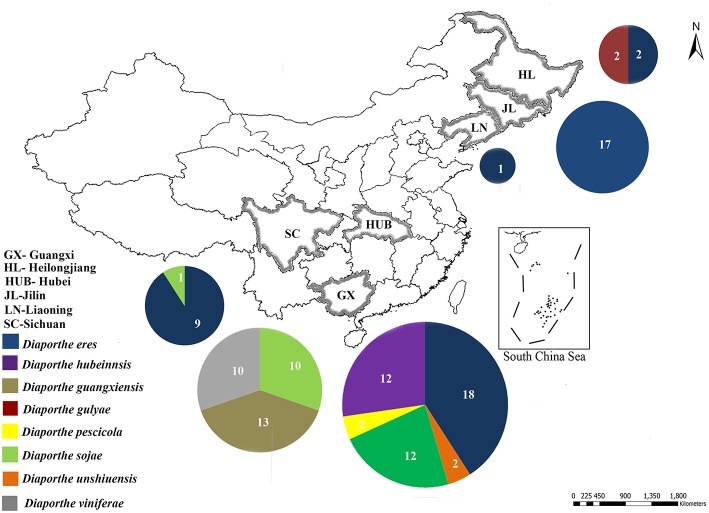

Field surveys were conducted during 2014 and 2015 in 20 vineyards in the six following provinces in China: Guangxi, Heilongjiang, Hubei, Jilin, Liaoning, and Sichuan (Figure 1). Samples were collected from symptomatic grapevine woody branches that exhibited bark discoloration, shoots breaking off at the base, stunting, wedge-shaped cankers, and light brown streaking of the wood from the following Vitis vinifera (V. vinifera) cultivars: Centennial Seedless, Red Globe, and Summer Black (Figure 2). Symptomatic tissue samples were collected into zip-lock plastic bags that contained wet sterilized tissue papers to maintain humidity. Once the samples were taken into the laboratory, infected trunks or shoots were photographed, and symptoms, location, and other relevant data were documented. The fungal pathogens were isolated using the following procedures. Infected shoots/trunks were cut into small pieces (1–3 mm thick). These pieces were then surface-sterilized by dipping into 70% ethanol for 30 s and then transferred into 1% NaOCl for 1 min. This step was followed by two washes with sterile distilled water. Once the wood pieces were dried, they were placed onto potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates supplemented with ampicillin (0.1 g L−1) and incubated at 25°C. After 5–7 days of incubation, hyphal tips of fungi immerging from wood pieces were transferred onto new PDA plates and incubated until they produce conidia. Once the conidia were developed single spore isolation was done. For the strains do not developed conidia after 4 weeks two-three times hyphal tip isolation was done. All the pure cultures obtained in this study were deposited in the culture collection of Institute of Plant and Environment Protection of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences (JZB culture collection) at 4°C.

Figure 1.

Sample collection sites of Diaporthe dieback in six provinces in China. Circles represent the association frequency of each species in each population sampled, and the number of isolates analyzed in each population is given inside the respective slice.

Figure 2.

Symptoms of Diaporthe dieback. (A,B) Field symptoms on trunks and shoots, (C) appearance of fruiting bodies on trunk surface, and (D,E) cross sections of infected trunks.

DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequence Assembly

Approximately 10 mg of aerial mycelium was scraped from 5–7 days old isolates grown on PDA (Potato Dextrose Agar) at 25°C. Total genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, QIAGEN Strasse 1, 40742 Hilden, Germany). For species confirmation, the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions were sequenced for all isolates. The obtained sequences were compared to those in GenBank using the MegaBLAST tool (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). After isolates were confirmed as belonging to the genus Diaporthe, six additional gene regions, those encoding translation elongation factor-1α (EF-1α), β-tubulin, calmodulin (CAL), partial histone H3 (HIS), partial actin (ACT), and DNA-lyase (Apn2), were sequenced. Table 1 presents the primer pairs with their respective amplification conditions for each of the above gene regions. PCR mixtures of 25 μl total volume consisted of 0.3 μl of TaKaRa Ex-Taq DNA polymerase, 2.5 μl of 10 × Ex-Taq DNA polymerase buffer, 3.0 μl of dNTPs, 2 μl of genomic DNA, 1 μl of each primer, and 15.2 ddH2O. The PCRs were conducted in a Bio-Rad C1000 thermal cycler (Germany). The resulting products were visualized on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide under UV light using a Gel DocTM XR Molecular Imager (Bio Rad, USA). All positive amplicons were sequenced by Beijing Biomed Gene Technology Co LTD. The sequence quality was confirmed by checking chromatograms using BioEdit v. 5 (Hall, 2006). Sequences were obtained using both forward and reverse primers, and consensus sequences were generated using DNAStar v. 5.1 (DNASTAR, Inc.). The sequence data generated in the present study have been deposited in GenBank (Table 2).

Table 1.

Gene regions and respective primer pairs used in the study.

| Gene region | Primers | Sequence 5′-3′ | Optimized PCR protocols | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT | ACT-512F | ATGTGCAAGGCCGGTTTCGC | 95°C: 5 min, (95°C: 30 s, 55°C: 50 s,72°C: 1 min) × 39 cycles 72°C: 10 min |

Carbone and Kohn, 1999 |

| ACT-783R | TACGAGTCCTTCTGGCCCAT | |||

| Apn2 (DNA lyase | apn2fw2 | GCMATGTTYGAMATYCTGGAG | 94°C: 1 min, (95°C: 30 s, 54°C: 50 s, 72°C: 1 min) × 39 cycles 72°C: 10 min |

Udayanga et al., 2012a,b |

| apn2rw2 | CTT GGTCTCCCAGCAGGTG AAC | |||

| CAL | CAL-228F | GAGTTCAAGGAGGCCTTCTCCC | 95°C: 5 min, (95°C: 30 s, 55°C: 50 s, 72°C: 1 min) × 34 cycles 72°C: 10 min |

Carbone and Kohn, 1999 |

| CAL-737R | CATCTTCTGGCCATCATGG | |||

| EF1-α | EF1-728F | CATCGAGAAGTTCGAGAAGG | 95°C: 5 min, (95°C: 30 s, 58°C: 30 s, 72°C: 1 min) × 34 cycles 72°C: 10 min |

Carbone and Kohn, 1999 |

| EF1-986R | TACTTGAAGGAACCCTTACC | Udayanga et al., 2012a,b | ||

| HIS | CYLH3F | AGGTCC ACTGGTGGCAAG | 96°C: 5 min, (96°C: 30 s, 58°C: 50 s, 72°C: 1 min) × 30 cycles 72°C: 5 min |

Crous et al., 2004 |

| H3-1b | GCGGGCGAGCTGGATGTCCTT | Glass and Donaldson, 1995 | ||

| ITS | ITS1 | TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG | 94°C: 5 min, (94°C: 30 s, 55°C: 50 s, 72°C: 1 min) × 34 cycles 72°C: 10 min |

White et al., 1990 |

| ITS4 | TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC | Udayanga et al., 2012a,b | ||

| β-tubulin | BT2a | GGTAACCAAATCGGTGCTGCTTTC | 94°C: 5 min, (94°C: 30 s, 58°C: 50 s, 72°C: 1 min) × 34 cycles 72°C: 10 min |

Glass and Donaldson, 1995 |

| Bt2b | ACCCTCAGTGTAGTGACCCTTGGC | Udayanga et al., 2012a,b |

Table 2.

Diaporthe species isolated and characterized in the present study.

| No | Species | Location | Year | JZB number | Sequence data | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | β-tubulin | CAL | EF-1α | |||||

| 01 | Diaporthe eres | Sichuan | 2015 | JZB320020* | – | MK500169 | MK500062 | MK523586 |

| 02 | Sichuan | 2015 | JZB320021* | MK335710 | MK500170 | MK500063 | MK523587 | |

| 03 | Sichuan | 2015 | JZB320022* | MK335711 | MK500171 | MK500064 | MK523588 | |

| 04 | Sichuan | 2015 | JZB320023* | MK335712 | MK500172 | MK500065 | MK523589 | |

| 05 | Sichuan | 2015 | JZB320024* | MK335713 | MK500173 | MK500066 | – | |

| 06 | Sichuan | 2015 | JZB320026 | MK335714 | MK500174 | MK500067 | MK523591 | |

| 07 | Sichuan | 2015 | JZB320027* | MK335715 | MK500175 | MK500068 | MK523619 | |

| 08 | Sichuan | 2015 | JZB320028* | MK335716 | MK500176 | MK500069 | MK523592 | |

| 09 | Sichuan | 2015 | JZB320029* | MK335717 | MK500177 | MK500070 | MK523620 | |

| 10 | Lioning | 2015 | JZB320030 | MK335718 | MK500178 | MK500071 | MK523621 | |

| 11 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320033* | MK335719 | MK500179 | MK500072 | MK523622 | |

| 12 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320034* | MK335720 | MK500180 | MK500073 | MK523623 | |

| 13 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320035* | MK335721 | MK500181 | MK500074 | MK523593 | |

| 14 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320036* | MK335722 | MK500182 | MK500075 | – | |

| 15 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320037* | MK335723 | MK500183 | MK500076 | – | |

| 16 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320038* | MK335724 | MK500184 | MK500077 | MK523594 | |

| 17 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320039* | MK335725 | MK500185 | MK500078 | MK523595 | |

| 18 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320040* | MK335726 | MK500186 | MK500079 | MK523596 | |

| 19 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320041* | MK335727 | MK500187 | MK500080 | – | |

| 20 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320043* | MK335728 | MK500188 | MK500081 | MK523624 | |

| 21 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320044* | MK335729 | MK500189 | MK500082 | – | |

| 22 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320045* | MK335730 | – | MK500083 | MK523597 | |

| 23 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320046* | MK335731 | MK500190 | MK500084 | MK523598 | |

| 24 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320047 | MK335732 | MK500191 | MK500085 | – | |

| 25 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320048* | MK335733 | MK500192 | MK500086 | MK523599 | |

| 26 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320049* | MK335734 | MK500193 | MK500087 | MK523625 | |

| 27 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320051* | MK335735 | MK500194 | MK500088 | MK523600 | |

| 28 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320052 | MK335736 | MK500195 | MK500089 | – | |

| 29 | Heilongjiang | 2015 | JZB320053* | MK335737 | MK500196 | MK500090 | MK523601 | |

| 30 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320054 | MK335738 | MK500197 | MK500091 | MK523602 | |

| 31 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320055* | MK335739 | MK500198 | MK500092 | MK523617 | |

| 32 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320056* | MK335740 | MK500199 | MK500093 | MK523618 | |

| 33 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320057* | MK335741 | MK500200 | MK500094 | MK523603 | |

| 34 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320058* | MK335742 | MK500201 | MK500095 | MK523604 | |

| 35 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320059* | MK335743 | MK500202 | MK500096 | MK523605 | |

| 36 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320060 | MK335744 | MK500203 | MK500097 | MK523606 | |

| 37 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320061* | MK335745 | MK500204 | MK500098 | MK523607 | |

| 38 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320062* | MK335746 | MK500205 | MK500099 | MK523614 | |

| 39 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320063* | MK335747 | MK500206 | MK500100 | MK523608 | |

| 40 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320064* | MK335748 | MK500207 | MK500101 | MK523609 | |

| 41 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320065 | MK335749 | MK500208 | MK500102 | MK523615 | |

| 42 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320066 | MK335750 | MK500209 | MK500103 | MK523610 | |

| 43 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320067 | MK335751 | MK500210 | MK500104 | MK523611 | |

| 44 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320068* | MK335752 | MK500211 | MK500105 | MK523612 | |

| 45 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320069* | MK335753 | MK500212 | MK500106 | MK523616 | |

| 46 | Jilin | 2015 | JZB320070* | MK335754 | MK500213 | – | MK523613 | |

| 47 | Diaporthe guangxiensis | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320082 | MK335760 | MK500156 | MK736715 | MK523557 |

| 48 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320083 | MK335761 | MK500157 | MK736716 | MK523558 | |

| 49 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320084 | MK335762 | MK500158 | MK736717 | – | |

| 50 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320085 | MK335763 | MK500159 | MK736718 | – | |

| 51 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320086 | MK335764 | MK500160 | MK736719 | MK523559 | |

| 52 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320087* | MK335765 | MK500161 | MK736720 | MK523560 | |

| 53 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320088 | MK335766 | MK500162 | MK736721 | MK523561 | |

| 54 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320089 | MK335767 | MK500163 | MK736722 | MK523562 | |

| 55 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320090 | MK335768 | MK500164 | MK736723 | MK523563 | |

| 56 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320091* | MK335769 | MK500165 | MK736724 | MK523564 | |

| 57 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320092 | MK335770 | MK500166 | MK736725 | – | |

| 58 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320093* | MK335771 | MK500167 | MK736726 | MK523565 | |

| 59 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320094* | MK335772 | MK500168 | MK736727 | MK523566 | |

| 60 | Diaporthe gulyae | Heilongjiang | 2015 | JZB320118 | KY400792 | KY400856 | – | KY400824 |

| 61 | Heilongjiang | 2015 | JZB320119 | KY400793 | KY400857 | – | KY400825 | |

| 62 | Diaporthe hubeiensis | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320120 | MK335806 | MK500144 | MK500232 | MK523567 |

| 63 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320121* | MK335807 | MK500146 | MK500233 | MK523568 | |

| 64 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320122* | MK335808 | MK500147 | MK500234 | MK523569 | |

| 65 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320123* | MK335809 | MK500148 | MK500235 | MK523570 | |

| 66 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320124* | MK335810 | MK500149 | MK500236 | MK523571 | |

| 67 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320125* | MK335811 | MK500150 | MK500237 | – | |

| 68 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320126 | MK335812 | MK500151 | MK500238 | – | |

| 69 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320127* | MK335813 | MK500152 | MK500239 | MK523572 | |

| 70 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320128* | MK335814 | MK500153 | MK500240 | MK523573 | |

| 71 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320139* | MK335815 | MK500154 | MK500241 | – | |

| 72 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320130 | MK335816 | MK500155 | MK500242 | – | |

| 73 | Diaporthe pescicola | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320095 | KY400784 | KY400890 | – | KY400817 |

| 74 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320096 | KY400785 | KY400891 | – | KY400831 | |

| 75 | Diaporthe sojae | Sichuan | 2015 | JZB320097 | MK335826 | MK500126 | MK500214 | MK523574 |

| 76 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320098 | MK335827 | MK500127 | MK500215 | MK523575 | |

| 77 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320099 | MK335828 | MK500128 | MK500216 | MK523576 | |

| 78 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320100 | MK335829 | – | MK500217 | – | |

| 79 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320101 | MK335830 | MK500129 | MK500218 | MK523577 | |

| 80 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320102 | MK335831 | MK500130 | MK500219 | MK523578 | |

| 81 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320103 | MK335832 | MK500131 | MK500220 | MK523579 | |

| 82 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320104 | MK335833 | MK500132 | MK500221 | MK523580 | |

| 83 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320105 | MK335834 | MK500133 | MK500222 | – | |

| 84 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320106 | MK335835 | MK500134 | MK500223 | – | |

| 85 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320107 | MK335836 | MK500135 | MK500224 | – | |

| 86 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320108 | MK335837 | MK500136 | MK500225 | MK523581 | |

| 87 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320109 | MK335838 | MK500137 | MK500226 | MK523582 | |

| 88 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320110 | MK335839 | MK500138 | MK500227 | – | |

| 89 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320111 | MK335840 | MK500139 | MK500228 | – | |

| 90 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320112 | MK335841 | MK500140 | MK500228 | MK523583 | |

| 91 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320113 | MK335842 | MK500141 | MK500230 | MK523584 | |

| 92 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320114 | MK335843 | MK500142 | MK500231 | MK523585 | |

| 93 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320115 | – | MK500143 | – | – | |

| 94 | Diaporthe unshiuensis | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320116 | KY400790 | KY400854 | – | KY400822 |

| 95 | Hubei | 2015 | JZB320117 | KY400791 | KY400855 | – | KY400823 | |

| 96 | Diaporthe viniferae | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320071* | MK341551 | MK500112 | MK500119 | MK500107 |

| 97 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320072 | MK341552 | MK500113 | MK500120 | MK500108 | |

| 98 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320076* | MK341553 | MK500115 | MK500122 | – | |

| 99 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320077 | MK341554 | MK500116 | MK500123 | MK500109 | |

| 100 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320078* | MK341555 | MK500117 | MK500124 | MK500110 | |

| 101 | Guangxi | 2015 | JZB320079* | MK341556 | MK500118 | MK500125 | MK500111 | |

JZB: Culture collection of Institute of Plant and Environment Protection, Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Beijing 100097, China. Ex-type cultures are indicated in bold. Isolates used in pathogenicity test are Italic. ITS, internal transcribed spacers 1 and 2 together with 5.8S nrDNA; β-tubulin, partial beta-tubulin gene; CAL, partial calmodulin gene; EF-1α, partial translation elongation factor 1-α gene.

Strains used in phylogenetic analysis (Figure 3).

Phylogenetic Analyses

For the phylogenetic analyses, reference sequences representing related taxa in Diaporthe were downloaded from GenBank (Guarnaccia et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Table 3) and aligned with the sequences obtained in this study (Table 2). The sequences were aligned using MAFFT (Katoh and Toh, 2010) (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/mafft/) and manually adjusted using BioEdit v. 5 (Hall, 2006) whenever necessary. Phylogenetic relationships were inferred using maximum parsimony (MP) implemented in PAUP (v4.0) (Swofford, 2003), maximum likelihood (ML) in RAxML (Silvestro and Michalak, 2010) and Bayesian analyses in MrBayes v. 3.0b4 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003). In phylogenetic analysis, single-gene trees were constructed first using ML in RAxML. The phylogenetic tree topologies for different gene fragments were compared for evidence of incongruences with a focus on comparing branches with high bootstrap values. If no conflict was observed, a combined phylogenetic tree was generated.

Table 3.

Diaporthe taxa used in the phylogenetic analysis.

| Species | Isolate | Host | Location | GenBank accession numbers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | β-tubulin | CAL | EF-1α | ||||

| D. acaciarum | CBS 138862 | Acacia tortilis | Tanzania | KP004460 | KP004509 | N/A | N/A |

| D. acaciigena | CBS 129521 | Acacia retinodes | Australia | KC343005 | KC343973 | KC343247 | KC343731 |

| D. acericola | MFLUCC 17-0956 | Acer negundo | Italy | KY964224 | KY964074 | KY964137 | KY964180 |

| D. acerigena | CFCC 52554 | Acer tataricum | China | MH121489 | N/A | MH121413 | MH121531 |

| CFCC 52555 | Acer tataricum | China | MH121490 | N/A | MH121414 | MH121532 | |

| D. acutispora | CGMCC 3.18285 | Coff sp. | China | KX986764 | KX999195 | KX999274 | KX999155 |

| D. alangii | CFCC 52556 | Alangium kurzii | China | MH121491 | MH121573 | MH121415 | MH121533 |

| D. alleghaniensis | CBS 495.72 | Betula alleghaniensis | Canada | KC343007 | KC343975 | KC343249 | KC343733 |

| D. alnea | CBS 146.46 | Alnus sp. | Netherlands | KC343008 | KC343976 | KC343250 | KC343734 |

| D. ambigua | CBS 114015 | Pyrus communis | South Africa | KC343010 | KC343978 | KC343252 | KC343736 |

| D. ampelina | STEU2660 | Vitis vinifera | France | AF230751 | JX275452 | AY745026 | AY745056 |

| D. amygdali | CBS 115620 | Prunus persica. | USA | KC343020 | KC343988 | KC343262 | KC343746 |

| CBS111811 | Vitis vinifera | South Africa | KC343019 | KC343987 | KC343261 | KC343745 | |

| CBS120840 | Prunus salicina | South Africa | KC343021 | KC343989 | KC343263 | KC343747 | |

| CBS 126679 | Prunus dulcis | Portugal | KC343022 | KC343990 | KC343264 | KC343748 | |

| D. anacardii | CBS 720.97 | Anacardium occidentale | East Africa | KC343024 | KC343992 | KC343266 | KC343750 |

| D. angelicae | CBS 111592 | Heracleum sphondylium | Austria | KC343027 | KC343995 | KC343269 | KC343753 |

| D. apiculate | CGMCC 3 17533 | Camellia sinensis | China | KP267896 | KP293476 | N/A | KP267970 |

| LC3187 | Camellia sinensis | China | KP267866 | KP293446 | N/A | KP267940 | |

| D. arengae | CBS 114979 | Arenga engleri | Hong Kong | KC343034 | KC344002 | KC343276 | KC343760 |

| D. aquatica | IFRDCC 3051 | Aquatic habitat | China | JQ797437 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| D. arctii | CBS 139280 | Arctium lappa | Austria | KJ590736 | KJ610891 | KJ612133 | KJ590776 |

| D. arengae | CBS 114979 | Arenga enngleri | Hong Kong | KC343034 | KC344002 | KC343276 | KC343760 |

| D. aseana | MFLUCC 12-0299a | Unknown dead leaf | Thailand | KT459414 | KT459432 | KT459464 | KT459448 |

| D. asheicola | CBS 136967 | Vaccinium ashei | Chile | KJ160562 | KJ160518 | KJ160542 | KJ160594 |

| D. aspalathi | CBS 117169 | Aspalathus linearis | South Africa | KC343036 | KC344004 | KC343278 | KC343762 |

| D. australafricana | CBS 111886 | Vitis vinifera | Australia | KC343038 | KC344006 | KC343280 | KC343764 |

| D. baccae | CBS 136972 | Vaccinium sp. | Italy | KJ160565 | N/A | N/A | KJ160597 |

| D. batatas | CBS 122.21 | Ipomoea batatas | USA | KC343040 | KC344008 | KC343282 | KC343766 |

| D. beilharziae | BRIP 54792 | Indigofera australis | Australia | JX862529 | KF170921 | N/A | JX862535 |

| D. benedicti | BPI 893190 | Salix sp. | USA | KM669929 | N/A | KM669862 | KM669785 |

| D. betulae | CFCC 50469 | Betula platyphylla | China | KT732950 | KT733020 | KT732997 | KT733016 |

| D. betulicola | CFCC 51128 | Betula albo-sinensis | China | KX024653 | KX024657 | KX024659 | KX024655 |

| CFCC 52560 | Betula albo- sinensis | China | MH121495 | MH121577 | MH121419 | MH121537 | |

| D. betulina | CFCC 52561 | Betula costata | China | MH121496 | MH121578 | MH121420 | MH121538 |

| D. bicincta | CBS 121004 | Juglans sp. | USA | KC343134 | KC344102 | KC343376 | KC343860 |

| D. biconispora | CGMCC 3.17252 | Citrus grandis | China | KJ490597 | KJ490418 | KJ490539 | KJ490476 |

| D. biguttulata | CFCC 52584 | Juglans regia | China | MH121519 | MH121598 | MH121437 | MH121561 |

| D. biguttusis | CGMCC 317081 | Lithocarpus glabra | China | KF576282 | KF576306 | N/A | KF576257 |

| CGMCC 317081 | Lithocarpus glabra | China | KF576283 | KF576307 | N/A | KF576258 | |

| D. bohemiae | CBS 1433477 | Vitis vinifera | Czech Republic | MG281015 | MG281188 | MG281710 | MG281536 |

| CBS 1433478 | Vitis vinifera | Czech Republic | MG281016 | MG281189 | MG281711 | MG281537 | |

| D. brasiliensis | CBS 133183 | Aspidosperma sp. | Brazil | KC343042 | KC344010 | KC343284 | KC343768 |

| D. caatingaensis | CBS 141542 | Tacinga inamoena | Brazil | KY085927 | KY115600 | N/A | KY115603 |

| D. camptothecicola | CFCC 51632 | Camptotheca sp. | China | KY203726 | KY228893 | KY228877 | KY228887 |

| D. canthii | CBS 132533 | Canthium inerme | South Africa | JX069864 | KC843230 | KC843174 | KC843120 |

| D. caryae | CFCC 52563 | Carya illinoensis | China | MH121498 | MH121580 | MH121422 | MH121540 |

| CFCC 52564 | Carya illinoensis | China | MH121499 | MH121581 | MH121423 | MH121541 | |

| D. cassines | CPC 21916 | Cassine peragua | South Africa | KF777155 | N/A | N/A | KF777244 |

| D. caulivora | CBS 127268 | Glycine max | Croatia | KC343045 | KC344013 | KC343287 | KC343771 |

| D. celeris | CBS143349 | Vitis vinifera | Czech Republic | MG281017 | MG281190 | MG281712 | MG281538 |

| CBS143350 | Vitis vinifera | Czech Republic | MG281018 | MG281191 | MG281713 | MG281539 | |

| D. celastrina | CBS 139.27 | Celastrus sp. | USA | KC343047 | KC344015 | KC343289 | KC343773 |

| D. cf nobilis | CBS 113470 | Castanea sativa | South Korea | KC343146 | KC344114 | KC343388 | KC343872 |

| CBS 587 79 | Pinus pantepella | Japan | KC343153 | KC344121 | KC343395 | KC343879 | |

| D. cercidis | CFCC 52565 | Cercis chinensis | China | MH121500 | MH121582 | MH121424 | MH121542 |

| D. chamaeropis | CBS 454.81 | Chamaerops humilis | Greece | KC343048 | KC344016 | KC343290 | KC343774 |

| D. charlesworthii | BRIP 54884m | Rapistrum rugostrum | Australia | KJ197288 | KJ197268 | N/A | KJ197250 |

| D. chensiensis | CFCC 52567 | Abies chensiensis | China | MH121502 | MH121584 | MH121426 | MH121544 |

| CFCC 52568 | Abies chensiensis | China | MH121503 | MH121585 | MH121427 | MH121545 | |

| D. cichorii | MFLUCC 17-1023 | Cichorium intybus | Italy | KY964220 | KY964104 | KY964133 | KY964176 |

| D. cinnamomi | CFCC 52569 | Cinnamomum sp. | China | MH121504 | MH121586 | N/A | MH121546 |

| D. cissampeli | CBS 141331 | Cissampelos capensis | South Africa | KX228273 | KX228384 | N/A | N/A |

| D. citri | CBS 135422 | Citrus sp. | Florida, USA | KC843311 | KC843187 | KC843157 | KC843071 |

| AR4469 | Citrus sp. | Florida, USA | KC843321 | KC843167 | KC843197 | KC843081 | |

| D. citriasiana | CGMCC 3.15224 | Citrus unshiu | China | JQ954645 | KC357459 | KC357491 | JQ954663 |

| D. citrichinensis | ZJUD34 | Citrus sp. | China | JQ954648 | N/A | KC357494 | JQ954666 |

| ZJUD85 | Citrus sp. | China | KJ490620 | KJ490441 | N/A | KJ490499 | |

| D. collariana | MFLU 17-2770 | Magnolia champaca | Thailand | MG806115 | MG783041 | MG783042 | MG783040 |

| D. compacta | CGMCC 3.17536 | Camellia sinensis | China | KP267854 | KP293434 | N/A | KP267928 |

| D. conica | CFCC 52571 | Alangium chinense | China | MH121506 | MH121588 | MH121428 | MH121548 |

| D. convolvuli | CBS 124654 | Convolvulus arvensis | Turkey | KC343054 | KC344022 | KC343296 | KC343780 |

| D. crotalariae | CBS 162.33 | Crotalaria spectabilis | USA | KC343056 | KC344024 | KC343298 | KC343782 |

| D. cucurbitae | CBS 136.25 | Arctium sp. | Unknown | KC343031 | KC343999 | KC343273 | KC343757 |

| D. cuppatea | CBS 117499 | Aspalathus linearis | South Africa | KC343057 | KC344025 | KC343299 | KC343783 |

| D. cynaroidis | CBS 122676 | Protea cynaroides | South Africa | KC343058 | KC344026 | KC343300 | KC343784 |

| D. cytosporella | FAU461 | Citrus limon | Italy | KC843307 | KC843221 | KC843141 | KC843116 |

| D. diospyricola | CPC 21169 | Diospyros whyteana | South Africa | KF777156 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| D. discoidispora | ZJUD89 | Citrus unshiu | China | KJ490624 | KJ490445 | N/A | KJ490503 |

| D. dorycnii | MFLUCC 17-1015 | Dorycnium hirsutum | Italy | KY964215 | KY964099 | N/A | KY964171 |

| D. elaeagni-glabrae | CGMCC 3.18287 | Elaeagnus glabra | China | KX986779 | KX999212 | KX999281 | KX999171 |

| D.ellipicola | CGMC 3 17084 | Lithocarpus glabra | China | KF576270 | KF576291 | N/A | KF576245 |

| D.endophytica | CBS133811 | Schinus terebinthifolius | Brazil | KC343065 | KC343065 | KC343307 | KC343791 |

| LGMF911 | Schinus terebinthifolius | Brazil | KC343066 | KC344034 | KC343308 | KC343792 | |

| D.eres | AR3519 | Corylus avellana | Austria | KJ210523 | KJ420789 | KJ435008 | KJ210547 |

| CBS 109767 = AR3538 | Acer sp. | Austria | DQ491514 KC344043 | KC343317 KC343801 | |||

| AR3560 | Viburnum sp. | Austria | JQ807425 | KJ420795 | KJ435011 | JQ807351 | |

| AR3723 | Rubus fruticosus | Austri | JQ807428 KJ420793 | KJ435024 JQ807354 | |||

| AR4346 | Prunus mume | Korea | JQ807429 | KJ420823 | KJ435003 | JQ807355 | |

| AR4373 | Ziziphus jujuba | Korea | JQ807442 | KJ420798 | KJ435013 | JQ807368 | |

| AR4348 | Prunus persica | Korea | JQ807431 | KJ420811 | KJ435004 | JQ807357 | |

| AR4363 | Malus sp. | Korea | JQ807436 | KJ420809 | KJ435033 | JQ807362 | |

| AR4369 | Pyrus pyrifolia | Korea | JQ807440 | KJ420813 | KJ435005 | JQ807366 | |

| AR4371 | Malus pumila | Korea | JQ807441 | KJ420796 | KJ435034 | JQ807367 | |

| AR5193 | Ulmus sp. | Germany | KJ210529 | KJ420799 | KJ434999 | KJ210550 | |

| AR5197 | Rhododendron sp. | Germany | KJ210531 | KJ420812 | KJ435014 | KJ210552 | |

| CBS113470 | Castanea sativa | Australia | KC343146 | KC344114 | KC343388 | KC343872 | |

| CBS135428 | Juglans cinerea | USA | KC843328 | KC843229 | KC843155 | KC843121 | |

| CBS138594 | Ulmus laevis | Germany | KJ210529 | KJ420799 | KJ434999 | KJ210550 | |

| CBS138595 | Ulmus laevis | Germany | KJ210533 | KJ420817 | KJ435006 | KJ210554 | |

| CBS138597 | Vitis vinifera | France | KJ210518 | KJ420783 | KJ434996 | KJ210542 | |

| CBS138598 | Ulmus sp. | USA | KJ210521 | KJ420787 | KJ435027 | KJ210545 | |

| CBS138599 | Acer nugundo | Germany | KJ210528 | KJ420830 | KJ435000 | KJ210549 | |

| CBS439.82 | Cotoneaster sp. | UK | FJ889450 | JX275437 | JX197429 | GQ250341 | |

| DNP128.1 | Castaneae mollissimae | China | JF957786 | KJ420801 | KJ435040 | KJ210561 | |

| DNP129 | Castanea mollissima | China | JQ619886 | KJ420800 | KJ435039 | KJ210560 | |

| DP0177 | Pyrus pyrifolia | New Zealand | JQ807450 | KJ420820 | KJ435041 | JQ807381 | |

| DP0179 | Pyrus pyrifolia | New Zealand | JQ807452 | KJ420803 | KJ43502 | JQ807383 | |

| DP0180 | Pyrus pyrifolia | New Zealand | JQ807453 | KJ420804 | KJ435029 | JQ807384 | |

| DP0438 | Ulmus minor | Austria | KJ210532 | KJ420816 | KJ435016 | KJ210553 | |

| FAU506 | Cornus florida | USA | KJ210526 | KJ420792 | KJ435012 | JQ807403 | |

| DP0590 | Pyrus pyrifolia | New Zealand | JQ807464 | KJ420810 | KJ435037 | JQ807394 | |

| DP0591 | Pyrus pyrifolia | New Zealand | JQ807465 | KJ420821 | KJ435018 | JQ807395 | |

| DP0666 | Juglans cinerea | USA | KJ210522 | KJ420788 | KJ435007 | KJ210546 | |

| FAU483 | Malus sp. | Netherlands | KJ210537 | KJ420827 | KJ435022 | KJ210556 | |

| FAU522 | Sassafras albidum | USA | KJ210525 | KJ420791 | KJ435010 | JQ807406 | |

| FAU532 | Chamaecyparis thyoides | USA | JQ807333 | KJ420815 | KJ435015 | JQ807408 | |

| LCM11401b | Ulmus sp. | USA | KJ210520 | KJ420786 | KJ435026 | KJ210544 | |

| LCM11401 | Ulmus sp. | USA | KJ210521 | KJ420787 | KJ435027 | KJ210545 | |

| M1118 | Vitis vinifera | France | KJ210519 | KJ420784 | KJ434997 | KJ210543 | |

| M1115 | Daphne laureola | France | KJ210516 | KJ420781 | KJ434994 | KJ210540 | |

| MAFF625033 | Pyrus pyrifolia | Japan | JQ807468 | KJ420814 | KJ435017 | JQ807417 | |

| MAFF625034 | Pyrus pyrifolia | Japan | JQ807469 | KJ420819 | KJ435023 | JQ807418 | |

| D. eucalyptorum | CBS 132525 | Eucalyptus sp. | Australia | NR120157 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| D. foeniculacea | CBS 123208 | Foeniculum vulgare | Portugal | KC343104 | KC344072 | KC343346 | KC343830 |

| D. fraxini- angustifoliae | BRIP 54781 | Fraxinus angustifolia | Australia | JX862528 | KF170920 | N/A | JX862534 |

| D. fraxinicola | CFCC 52582 | Fraxinus chinensis | China | MH121517 | N/A | MH121435 | MH121559 |

| D. fukushii | MAFF 625034 | Pyrus pyrifolia | Japan | JQ807469 | N/A | N/A | JQ807418 |

| D. fusicola | CGMCC 3.17087 | Lithocarpus glabra | China | KF576281 | KF576305 | KF576233 | KF576256 |

| D. ganjae | CBS 180.91 | Cannabis sativa | USA | KC343112 | KC344080 | KC343354 | KC343838 |

| D. garethjonesii | MFLUCC 12-0542a | Unknown dead leaf | Thailand | KT459423 | KT459441 | KT459470 | KT459457 |

| D. goulteri | BRIP 55657a | Helianthus annuus | Australia | KJ197290 | KJ197270 | N/A | KJ197252 |

| D. gulyae | BRIP 54025 | Helianthus annuus | Australia | JF431299 | JN645803 | N/A | KJ197271 |

| D. helianthi | CBS 592.81 | Helianthus annuus | Serbia | KC343115 | KC344083 | KC343357 | KC343841 |

| D. helicis | AR5211 | Hedera helix | France | KJ210538 | KJ420828 | KJ435043 | KJ210559 |

| D. heterophyllae | CBS 143769 | Acacia heterohpylla | France | MG600222 | MG600226 | MG600218 | MG600224 |

| D. hickoriae | CBS 145.26 | Carya glabra | USA | KC343118 | KC344086 | KC343360 | KC343844 |

| D. hispaniae | CPC 30321 | Vitis vinifera | Spain | MG281123 | MG281296 | MG281820 | MG281644 |

| D. hongkongensis | CBS 115448 | Dichroa febrífuga | China | KC343119 | KC344087 | KC343361 | KC343845 |

| D.hungariae | CBS143353 | Vitis vinifera | Hungary | MG281126 | MG281299 | MG281823 | MG281647 |

| D. incompleta | CGMCC 3.18288 | Camellia sinensis | China | KX986794 | KX999226 | KX999289 | KX999186 |

| D. inconspicua | CBS 133813 | Maytenus ilicifolia | Brazil | KC343123 | KC344091 | KC343365 | KC343849 |

| D. infecunda | CBS 133812 | Schinus sp. | Brazil | KC343126 | KC344094 | KC343368 | KC343852 |

| D. isoberliniae | CPC 22549 | Isoberlinia angolensis | Zambia | KJ869133 | KJ869245 | N/A | N/A |

| CFCC 51135 | Juglans mandshurica | China | KU985102 | KX024635 | KX024617 | KX024629 | |

| D. kadsurae | CFCC 52587 | Kadsura longipedunculata | China | MH121522 | MH121601 | MH121440 | MH121564 |

| D. kochmanii | BRIP 54033 | Helianthus annuus | Australia | JF431295 | N/A | N/A | JN645809 |

| D. kochmanii | BRIP 54034 | Helianthus annuus | Australia | JF431296 | N/A | N/A | JN645810 |

| D. kongii | BRIP 54031 | Portulaca grandifl a | Australia | JF431301 | KJ197272 | N/A | JN645797 |

| D. litchicola | BRIP 54900 | Litchi chinensis | Australia | JX862533 | KF170925 | N/A | JX862539 |

| D. lithocarpus | CGMCC 3.15175 | Lithocarpus glabra | China | KC153104 | KF576311 | KF576235 | KC153095 |

| D. longicicola | CGMCC 3.17089 | Lithocarpus glabra | China | KF576267 | KF576291 | N/A | KF576242 |

| CGMCC 3 17090 | Lithocarpus glabra | China | KF576268 | KF576292 | N/A | KF576243 | |

| D. longispora | CBS 194.36 | Ribes sp. | Canada | KC343135 | KC344103 | KC343377 | KC343861 |

| D. lonicerae | MFLUCC 17-0963 | Lonicera sp. | Italy | KY964190 | KY964073 | KY964116 | KY964146 |

| D. lusitanicae | CBS 123212 | Foeniculum vulgare | Portugal | KC343136 | KC344104 | KC343378 | KC343862 |

| D. macinthoshii | BRIP 55064a | Rapistrum rugostrum | Australia | KJ197289 | KJ197269 | N/A | KJ197251 |

| D. mahothocarpus | CGMCC 3.15181 | Lithocarpus glabra | China | KC153096 | KF576312 | N/A | KC153087 |

| D. malorum | CAA734 | Malus domestica | Portugal | KY435638 | KY435668 | KY435658 | KY435627 |

| D.momicola | MFLUCC 16-0113 | Prunus persica | Hubei, China | KU557563 | KU557587 | KU557611 | KU557631 |

| D. maritima | DAOMC 250563 | Picea rubens | Canada | N/A | KU574616 | N/A | N/A |

| D. masirevicii | BRIP 57892a | Helianthus annuus | Australia | KJ197277 | KJ197257 | N/A | KJ197239 |

| D. mayteni | CBS 133185 | Maytenus ilicifolia | Brazil | KC343139 | KC344107 | KC343381 | KC343865 |

| D. maytenicola | CPC 21896 | Maytenus acuminata | South Africa | KF777157 | KF777250 | N/A | N/A |

| D. melonis | CBS 507.78 | Cucumis melo | USA | KC343142 | KC344110 | KC343384 | KC343868 |

| D. middletonii | BRIP 54884e | Rapistrum rugostrum | Australia | KJ197286 | KJ197266 | N/A | KJ197248 |

| D. miriciae | BRIP 54736j | Helianthus annuus | Australia | KJ197282 | KJ197262 | N/A | KJ197244 |

| D. multigutullata | ZJUD98 | Citrus grandis | China | KJ490633 | KJ490454 | N/A | KJ490512 |

| D. musigena | CBS 129519 | Musa sp. | Australia | KC343143 | KC344111 | KC343385 | KC343869 |

| D. neilliae | CBS 144.27 | Spiraea sp. | USA | KC343144 | KC344112 | KC343386 | KC343870 |

| D. neoarctii | CBS 109490 | Ambrosia trifi | USA | KC343145 | KC344113 | KC343387 | KC343871 |

| D.neoraonikayaporum | MFLUCC 14-1136 | Tectona grandis | Thailand | KU712449 | KU743988 | KU749356 | KU749369 |

| D. nobilis | CBS 113470 | Castanea sativa | Korea | KC343146 | KC344114 | KC343388 | KC343872 |

| D. nothofagi | BRIP 54801 | Nothofagus cunninghamii | Australia | JX862530 | KF170922 | N/A | JX862536 |

| D. novem | CBS 127270 | Glycine max | Croatia | KC343155 | KC344123 | KC343397 | KC343881 |

| D. ocoteae | CBS 141330 | Ocotea obtusata | France | KX228293 | KX228388 | N/A | N/A |

| D. oraccinii | CGMCC 3.17531 | Camellia sinensis | China | KP267863 | KP293443 | N/A | KP267937 |

| D. ovalispora | ICMP20659 | Citrus limon | China | KJ490628 | KJ490449 | N/A | KJ490507 |

| D. ovoicicola | CGMCC 3.17093 | Citrus sp. | China | KF576265 | KF576289 | KF576223 | KF576240 |

| D. oxe | CBS 133186 | Maytenus ilicifolia | Brazil | KC343164 | KC344132 | KC343406 | KC343890 |

| D. padina | CFCC 52590 | Padus racemosa | China | MH121525 | MH121604 | MH121443 | MH121567 |

| CFCC 52591 | Padus racemosa | China | MH121526 | MH121605 | MH121444 | MH121568 | |

| D. pandanicola | MFLU 18-0006 | Pandanus sp. | Thailand | MG646974 | MG646930 | N/A | N/A |

| D. paranensis | CBS 133184 | Maytenus ilicifolia | Brazil | KC343171 | KC344139 | KC343413 | KC343897 |

| D. parapterocarpi | CPC 22729 | Pterocarpus brenanii | Zambia | KJ869138 | KJ869248 | N/A | N/A |

| D. pascoei | BRIP 54847 | Persea americana | Australia | JX862532 | KF170924 | N/A | JX862538 |

| D. passifl ae | CBS 132527 | Passifl a edulis | South America | JX069860 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| D. passifl | CBS 141329 | Passifl a foetida | Malaysia | KX228292 | KX228387 | N/A | N/A |

| D. penetriteum | CGMCC 3.17532 | Camellia sinensis | China | KP714505 | KP714529 | N/A | KP714517 |

| D. perjuncta | CBS 109745 | Ulmus glabra | Austria | KC343172 | KC344140 | KC343414 | KC343898 |

| D. perseae | CBS 151.73 | Persea gratissima | Netherlands | KC343173 | KC344141 | KC343415 | KC343899 |

| D. pescicola | MFLU 16-0105 | Prunus persica | Hubei, China | KU557555 | KU557579 | KU557603 | KU557623 |

| D. phaseolorum | AR4203 | Phaseolus vulgaris | USA | KJ590738 | KP004507 | N/A | N/A |

| D.phragmitis | CBS 138897 | Phragmites australis | China | KP004445 | KP004507 | N/A | N/A |

| D. podocarpi- macrophylli | CGMCC 3.18281 | Podocarpus macrophyllus | China | KX986774 | KX999207 | KX999278 | KX999167 |

| D. pseudomangiferae | CBS 101339 | Mangifera indica | Dominican Republic | KC343181 | KC344149 | KC343423 | KC343907 |

| D.pseudophoenicicola | CBS 462.69 | Phoenix dactylifera | Spain | KC343184 | KC344152 | KC343426 | KC343910 |

| D. pseudotsugae | MFLU 15-3228 | Pseudotsuga menziesii | Italy | KY964225 | KY964108 | KY964138 | KY964181 |

| D. psoraleae | CBS 136412 | Psoralea pinnata | South Africa | KF777158 | KF777251 | N/A | KF777245 |

| D. psoraleae- pinnatae | CBS 136413 | Psoralea pinnata | South Africa | KF777159 | KF777252 | N/A | N/A |

| D. pterocarpi | MFLUCC 10-0571 | Pterocarpus indicus | Thailand | JQ619899 | JX275460 | JX197451 | JX275416 |

| D. pterocarpicola | MFLUCC 10-0580 | Pterocarpus indicus | Thailand | JQ619887 | JX275441 | JX197433 | JX275403 |

| D. pulla | CBS 338.89 | Hedera helix | Yugoslavia | KC343152 | KC344120 | KC343394 | KC343878 |

| D. pyracanthae | CAA483 | Pyracantha coccinea | Portugal | KY435635 | KY435666 | KY435656 | KY435625 |

| D. racemosae | CBS 143770 | Euclea racemosa | South Africa | MG600223 | MG600227 | MG600219 | MG600225 |

| D. raonikayaporum | CBS 133182 | Spondias mombin | Brazil | KC343188 | KC344156 | KC343430 | KC343914 |

| D. ravennica | MFLUCC 15-0479 | Tamarix sp. | Italy | KU900335 | KX432254 | N/A | KX365197 |

| D. rhusicola | CBS 129528 | Rhus pendulina | South Africa | JF951146 | KC843205 | KC843124 | KC843100 |

| D. rosae | MFLU 17-1550 | Rosa sp. | Thailand | MG828894 | MG843878 | N/A | N/A |

| D. rosicola | MFLU 17-0646 | Rosa sp. | UK | MG828895 | MG843877 | N/A | MG829270 |

| D. rostrata | CFCC 50062 | Juglans mandshurica | China | KP208847 | KP208855 | KP208849 | KP208853 |

| D. rudis | AR3422 | Laburnum anagyroides | Austria | KC843331 | KC843177 | KC843146 | KC843090 |

| D. saccarata | CBS 116311 | Protea repens | South Africa | KC343190 | KC344158 | KC343432 | KC343916 |

| D. sackstonii | BRIP 54669b | Helianthus annuus | Australia | KJ197287 | KJ197267 | N/A | KJ197249 |

| D. salicicola | BRIP 54825 | Salix purpurea | Australia | JX862531 | JX862531 | N/A | JX862537 |

| D. sambucusii | CFCC 51986 | Sambucus williamsii | China | KY852495 | KY852511 | KY852499 | KY852507 |

| D. schini | CBS 133181 | Schinus terebinthifolius | Brazil | KC343191 | KC344159 | KC343433 | KC343917 |

| D. schisandrae | CFCC 51988 | Schisandra chinensis | China | KY852497 | KY852513 | KY852501 | KY852509 |

| D. schoeni | MFLU 15-1279 | Schoenus nigricans | Italy | KY964226 | KY964109 | KY964139 | KY964182 |

| D. sclerotioides | CBS 296.67 | Cucumis sativus | Netherlands | KC343193 | KC344161 | KC343435 | KC343919 |

| D. sennae | CFCC 51636 | Senna bicapsularis | China | KY203724 | KY228891 | KY228875 | KY228885 |

| D. sennicola | CFCC 51634 | Senna bicapsularis | China | KY203722 | KY228889 | KY228873 | KY228883 |

| D. serafi | BRIP 55665a | Helianthus annuus | Australia | KJ197274 | KJ197254 | N/A | KJ197236 |

| D. siamensis | MFLUCC 10-573a | Dasymaschalon sp. | Thailand | JQ619879 | JX275429 | N/A | JX275393 |

| D. sojae | FAU635 | Glycine max | Ohio, USA | KJ590719 | KJ610875 | KJ612116 | KJ590762 |

| BRIP 54033 | Helianthus annuus | Australia | JF431295 | KJ160528 | KJ160548 | JN645809 | |

| CBS116019 | Caperonia palustris | USA | KC343175 | KJ610862 | KJ612103 | KC343901 | |

| DP0601 | Glycine max | USA | KJ590706 | N/A | N/A | KJ590749 | |

| DP0605 | Glycine max | USA | KJ590707 | KJ610863 | KJ612104 | KJ590750 | |

| DP0616 | Glycine max | USA | KJ590715 | KJ610871 | KJ612112 | KJ590758 | |

| FAU455 | Stokesia laevis | USA | KJ590712 | KJ610870 | KJ612111 | KJ590755 | |

| FAU458 | Stokesia laevis | USA | KJ590710 | KJ610866 | KJ612107 | KJ590753 | |

| FAU459 | Stokesia laevis | USA | KJ590709 | KJ610865 | KJ612106 | KJ590752 | |

| FAU499 | Asparagus officinalis | USA | KJ590717 | KJ610873 | KJ612114 | KJ590760 | |

| FAU604 | Glycine max | USA | KJ590716 | KJ610872 | KJ612113 | KJ590759 | |

| FAU636 | Glycine max | USA | KJ590718 | KJ610874 | KJ612115 | KJ590761 | |

| ZJUD68 | Glycine max | USA | KJ490603 | KJ490424 | N/A | KJ490482 | |

| ZJUD69 | Citrus reticulata | China | KJ490604 | KJ490425 | N/A | KJ490483 | |

| ZJUD70 | Citrus limon | China | KJ490605 | KJ490426 | N/A | KJ490484 | |

| D. spartinicola | CBS 140003 | Spartium junceum | Spain | KR611879 | KC344180 | KC343454 | N/A |

| D. sterilis | CBS 136969 | Vaccinium corymbosum | Italy | KJ160579 | KJ490408 | N/A | KJ160611 |

| D. stictica | CBS 370.54 | Buxus sampervirens | Italy | KC343212 | MG746631 | N/A | KC343938 |

| D. subclavata | ICMP20663 | Citrus unshiu | China | KJ490587 | MG746634 | N/A | KJ490466 |

| D. subcylindrospora | MFLU 17-1195 | Salix sp. | China | MG746629 | KC344182 | KC343456 | MG746630 |

| D. subellipicola | MFLU 17-1197 | on dead wood | China | MG746632 | KU557591 | KU557567 | MG746633 |

| D. subordinaria | CBS 464.90 | Plantago lanceolata | New Zealand | KC343214 | KU557592 | KU557568 | KC343940 |

| D. taoicola | MFLUCC 16 0117 | Prunus persica | Hubei, China | NR154923 | KU743977 | KU712430 | KU557635 |

| D. tectonae | MFLUCC 12 0777 | Tectona grandis | Thailand | NR147590 | KU743977 | KU749345 | KU749359 |

| D. tectonigena | MFLUCC 12-0767 | Tectona grandis | China | KU712429 | JX275449 | JX197440 | KU749371 |

| D. terebinthifolii | CBS 133180 | Schinus terebinthifolius | Brazil | KC343216 | N/A | N/A | KC343942 |

| D. thunbergii | MFLUCC 10-576a | Th laurifolia | Thailand | JQ619893 | MF279873 | MF279888 | JX275409 |

| D. thunbergiicola | MFLUCC 12-0033 | Th laurifolia | Thailand | KP715097 | MF279874 | MF279889 | KP715098 |

| D. tibetensis | CFCC 51999 | Juglandis regia | China | MF279843 | KY964096 | KY964127 | MF279858 |

| D. torilicola | MFLUCC 17-1051 | Torilis arvensis | Italy | KY964212 | KR936132 | N/A | KY964168 |

| D. toxica | CBS 534.93 | Lupinus angustifolius | Australia | KC343220 | KJ610881 | KJ612122 | KC343946 |

| D. tulliensis | BRIP62248a | Theobroma cacao | Australia | KR936130 | N/A | MH121445 | KR936133 |

| D. ueckerae | FAU656 | Cucumis melo | USA | KJ590726 | N/A | MH121446 | KJ590747 |

| D. ukurunduensis | CFCC 52592 | Acer ukurunduense | China | MH121527 | KX999230 | N/A | MH121569 |

| CFCC 52593 | Acer ukurunduense | China | MH121528 | KJ490408 | N/A | MH121570 | |

| D. undulata | CGMCC 3.18293 | Leaf of unknown host | China-Laos border | KX986798 | KJ490406 | N/A | KX999190 |

| D. unshiuensis | ZJUD50 | Fortunella margarita | China | KJ490585 | KC344195 | KC343469 | KJ490464 |

| D. vaccini | CBS160 32 | Oxycoccus macrocarpos | USA | KC343228 | KJ869247 | N/A | KC343954 |

| D. vangueriae | CPC 22703 | Vangueria infausta | Zambia | KJ869137 | KX999223 | N/A | N/A |

| D. vawdreyi | BRIP 57887a | Psidium guajava | Australia | KR936126 | KP247575 | N/A | KR936129 |

| D. velutina | CGMCC 3.18286 | Neolitsea sp. | China | KX986790 | KX999216 | N/A | KX999182 |

| D. virgiliae | CMW40748 | Virgilia oroboides | South Africa | KP247566 | KX999228 | KX999290 | N/A |

| D. xishuangbanica | CGMCC 3.18282 | Camellia sinensis | China | KX986783 | KC343972 | KC343246 | KX999175 |

| D. yunnanensis | CGMCC 3.18289 | Coff sp. | China | KX986796 | N/A | KX999290 | KX999188 |

| Diaporthella corylina | CBS 121124 | Corylus sp. | China | KC343004 | KC343972 | KC343246 | KC343730 |

BRIP, Plant Pathology Herbarium, Department of Primary Industries, Dutton Park, Queensland, Australia; CPC, Culture collection of P.W. Crous, housed at Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute; CBS, Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, The Netherlands; DAOM, Canadian Collection of Fungal Cultures or the National Mycological Herbarium, Plant Research Institute, Department of Agriculture (Mycology), Ottawa, Canada; ICMP, International Collection of Microorganisms from Plants, Landcare Research, Auckland, New Zealand. MFLUCC, Mae Fah Luang University culture collection, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, 57100, Thailand. JZB, Culture collection of Institute of Plant and Environment Protection, Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Beijing 100097, China. AR, DAN, DNP, FAU, DLR, DF, DP, LCM, M, isolates in SMML culture collection, USDA-ARS, Beltsville, MD, USA, and MAFF, NIAS Genebank Project, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Japan. Ex-type and ex-epitype cultures are indicated in bold. ITS, internal transcribed spacers 1 and 2 together with 5.8S nrDNA; β-tubulin, partial beta-tubulin gene; CAL, partial calmodulin gene and EF-1α, partial translation elongation factor 1-α gene.

In PAUP, ambiguous regions in the alignment were excluded for further analyses, and gaps were treated as missing data. The stability of the trees was evaluated by 1000 bootstrap replications. Branches of zero length were collapsed, and all multiple parsimonious trees were saved. Parameters, including tree length (TL), consistency index (CI), retention index (RI), relative consistency index (RC), and homoplasy index (HI) were calculated. Differences between the trees inferred under different optimality criteria were evaluated using Kishino-Hasegawa tests (KHT) (Kishino and Hasegawa, 1989). The evolutionary models for each locus used in Bayesian analysis and ML were selected using MrModeltest v. 2.3 (Nylander, 2004). ML analyses were accomplished using RAxML-HPC2 on XSEDE (8.2.8) (Stamatakis et al., 2008; Stamatakis, 2014) in the CIPRES Science Gateway platform (Miller et al., 2010) using the GTR + I + G model of evolution with 1000 non-parametric bootstrapping iterations. Bayesian analysis was performed in MrBayes v. 3.0b4 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003), and posterior probabilities (PPs) were determined by Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling (MCMC). Six simultaneous Markov chains were run for 106 generations, sampling the trees at every 100th generation. From the 10,000 trees obtained, the first 2,000 representing the burn-in phase were discarded. The remaining 8,000 trees were used to calculate PPs in a majority rule consensus tree. Alignment generated in this study is submitted to TreeBASE (https://treebase.org/treebase-web/home.html) under the submission number 24324. Taxonomic novelties were submitted to the Faces of Fungi database (Jayasiri et al., 2015) and Index fungorum (http://www.indexfungorum.org). New species are described following Jeewon and Hyde (2016).

Morphology and Culture Characteristics

Colony morphology and conidial characteristics were examined for Diaporthe species identified by phylogenetic analysis. Colony colors were examined according to Rayner (1970) after 7 days of growth on PDA in the dark at 25°C. Digital images of morphological structures mounted in water were taken using an Axio Imager Z2 photographic microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Oberkochen, Germany). Measurements were taken using ZEN PRO 2012 (Carl Zeiss Microscopy). Conidial length and width were measured for 40 conidia per isolate, and the mean values were calculated for all measurements. Conidial shape, color, and guttulation were recorded.

Genetic Diversity and Population Structure Analysis

Among the identified species, only one, Diaporthe eres, had a count of >20 individuals. As a result, only D. eres was selected for the analysis of genetic diversity and population relationships. For the D. eres population, diversity indices were calculated for each gene region and the combined sequence dataset. DnaSP v. 6.12 (Librado and Rozas, 2009) was employed to calculate haplotype richness (hR), the total number of haplotypes, Watterson's theta (Θw), and pairwise nucleotide diversity (JI). To overcome the population size effects, hR, Θw and JI were calculated after 1,000 repetitions, and the median estimate was recorded for each parameter. To understand the potential departure from an equilibrium model of evolution, Tajima's D was calculated using DnaSP v. 6.12 with a permutation test of 1,000 replicates. The minimum numbers of recombination events (ZnS) used by Kelly (1997) and the recombination parameters Za and ZZ used by Hudson (1983) were calculated for each gene region and the combined data set. Diaporthe eres haplotype networks were constructed using Network v. 5.0 (Bandelt et al., 1999).

Network Analysis

To understand the relationship among different geographical populations, recombination parameters were calculated, and haplotype networks were constructed. In this analysis, the combined dataset of Diaporthe eres isolates from China alone and Chinese isolates combined with European isolates (Guarnaccia et al., 2018) were used. ZnS, used by Kelly (1997), and the recombination parameters Za and ZZ (Hudson, 1983; Kelly, 1997) were calculated using DnaSP v. 6.12. The haplotype data generated using DnaSP v. 6 were used to construct a median-joining network in Network v. 5.0 (Bandelt et al., 1999).

Pathogenicity Assay

The pathogenicity and aggressiveness of the Diaporthe species were tested using detached green shoots of the V. vinifera cultivar Summer Black. Healthy, 30–50 cm long green shoots (including at least two nodes) were obtained from “Shunyi Xiangyi” vineyard in Beijing, China, where Diaporthe species were not recorded. The cuttings were surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol by wiping with cotton swabs. A shallow wound (5 mm length, 2 mm deep) was made in the center of each shoot using a sterilized scalpel. Mycelial plugs were taken from the growing margin of a 5-day-old culture grown in PDA and inoculated at the wound site. Non-colonized sterile PDA plugs were used for inoculation of shoots as a negative control. To prevent drying, all inoculated areas were covered with Para-film (Bemis, USA). Inoculated shoots were kept in a growth chamber for 21 days at 25°C with a 12 h photoperiod. The experiment was organized with 10 replicates for each isolate. Pathogenicity test was repeated three times with same controlled environment. A total of 16 strains from eight species were tested. The presence of lesions advancing beyond the original 0.5 cm diameter inoculation point was considered indicative of pathogenicity. The experimental design was completely randomized. Data were analyzed with a one-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) using Minitab v. 16.0 (Minitab Inc., Boston, MA, USA), with statistical significance set at the 5% level. The pathogens were re-isolated to confirm their identity.

Results

Initial Species Identification and Phylogenetic Analyses

During our field survey on six grape-growing provinces in China (Figure 1), we collected samples with typical symptoms associated with Diaporthe dieback, such as wedge-shaped cankers, and light brown streaking of the wood (Figure 2). However, these symptoms are sometimes confused with other grape trunk disease symptoms caused by Botryosphaeria dieback, Eupta, and Esca (Mondello et al., 2018). Hence, further confirmation is required by isolating and identifying causal organisms. One hundred and eleven Diaporthe isolates were initially identified by colony characteristics, such as abundant tufted white aerial mycelia on agar medium. The ITS gene regions were sequenced for all fungi isolated from diseased shoots and compared with those in GenBank using the MegaBLAST tool in GenBank. The isolates showed 95–99% similarity to known Diaporthe species in GenBank, and these closely related known species were included in the phylogenetic analysis.

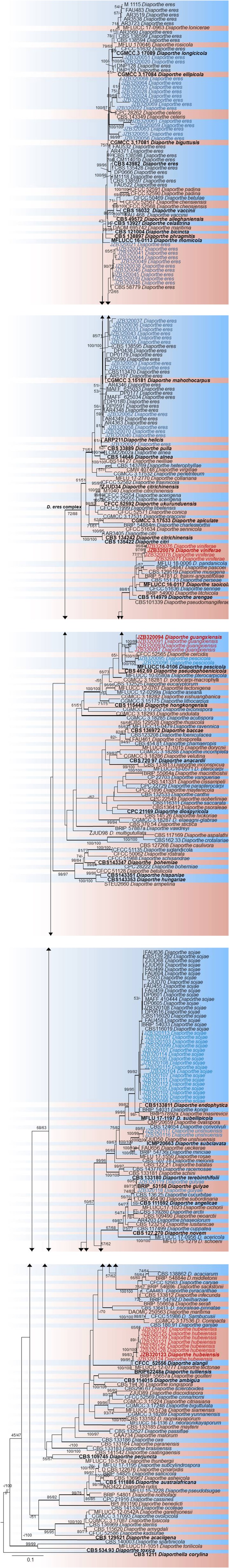

To understand the taxonomic placements of our isolates, additional gene regions, including those encoding EF-1α, β-tubulin, and CAL, were sequenced. Then, phylogenetic trees were constructed for each individual gene region. The concatenated sequence data set consisted of 94 isolates (out of 111, due to sequencing errors) from the current study (Table 3) and 197 isolates originating from GenBank (Table 2), with one outgroup taxon, Diaporthella corylina (CBS 121124). A comparison of maximum likelihood (ML) analysis results for each gene region is given in Table 4. In the ML analysis, the resulting tree of the combined data set of ITS, β-tubulin, CAL, and EF-1α genes had the best resolution of taxa (Figure 3). Therefore, in the present study, we used the combined sequence data to understand the taxonomic placements of the Diaporthe species isolated from grapevines in China. A Bayesian analysis resulted in 10,001 trees after 2,000,000 generations. The first 1,000 trees, representing the burn-in phase of the analyses, were discarded, while the remaining 9,001 trees were used for calculating posterior probabilities (PPs) in the majority-rule consensus tree. The dataset consisted of 1,494 characters with 727 constant characters and 1,006 parsimony-informative and 213 parsimony-uninformative characters. The maximum number of trees generated was 1,000, and the most parsimonious trees had a tree length of 9,862 (CI = 0.249, RI = 0.805, RC = 0.201, HI = 0.751).

Table 4.

Comparison of ML analyses results for each gene region.

| Data set | ITS | β-tubulin | CAL | EF-1α | ITS+ β-tubulin+ CAL+ EF-1α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant characters | 226 | 226 | 226 | 68 | |

| Parsimony-uninformative characters | 107 | 26 | 107 | 48 | |

| Parsimony-informative characters | 189 | 249 | 189 | 335 | |

| ML optimization likelihood value | −51,581.507970 | −9741.212701 | −7853.669691 | −16943.655728 | −50,588.257001 |

| Distinct alignment patterns | 291 | 304 | 293 | 293 | 1,330 |

| Undetermined characters or gaps | 7.18% | 26.12% | 8.74% | 28.55% | 28.70% |

| ESTIMATED BASE FREQUENCIES | |||||

| A | 0.244043 | 0.200039 | 0.211490 | 0.220112 | 0.221742 |

| C | 0.277339 | 0.349071 | 0.313694 | 0.329420 | 0.313804 |

| G | 0.247357 | 0.233934 | 0.253908, | 0.250506 | 0.235189 |

| T | 0.231261 | 0.216955 | 0.220908 | 0.220908 | 0.229264 |

| SUBSTITUTION RATES | |||||

| AC | 1.300271 | 0.791706 | 1.041213 | 1.457977 | 1.328496 |

| AG | 2.994990 | 3.761550 | 4.289330 | 3.778337 | 3.630252 |

| AT | 1.401626 | 0.962021 | 1.307157 | 1.339450 | 1.324920 |

| CG | 0.826919 | 0.668475 | 1.259772 | 1.119872 | 0.954109 |

| CT | 7.266633 | 7.266633 | 5.662938 | 3.976963 | 4.974568 |

| GT | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 |

| Proportion of invariable sites (I) | 0.274443 | 0.350656 | 0.274443 | 0.274443 | 0.269146 |

| Gamma distribution shape parameter (α) | 0.405766 | 2.208572 | 0.405766 | 0.405766 | 0.869283 |

Figure 3.

RAxML tree based on analysis of a combined dataset of ITS, β-tubulin, CAL, and EF-1α sequences. Bootstrap support values for ML and MP equal to or >50% are shown as ML/MP above the nodes. The isolates obtained for the present study are shown in blue for already known species, and novel taxa are shown in red. Ex-type strains are indicated in bold. The tree is rooted using Diaporthella corylina. The scale bar represents the expected number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

In the phylogenetic tree generated using the combined data set (Figure 3), 36 isolates from the present study clustered with Diaporthe eres in the D. eres complex. This group represents 37.5% of the total isolates, and these isolates were obtained from five provinces. Sixteen isolates (19.76% of the total isolates) clustered with Diaporthe sojae (D. sojae) species in the D. sojae complex. Two isolates from Heilongjiang province clustered together with Diaporthe gulyae (D. gulyae) (BRIP 54025). In addition, two isolates clustered with Diaporthe unshiuensis (D. unshiuensis) (ZJUD52) from Hubei province, and another two isolates that were also from Hubei province clustered with Diaporthe pescicola (D. pescicola) (MFLUCC 16-0105). The remaining isolates (35 in total) did not cluster with any known Diaporthe species. Thus, these were putatively identified as belonging to three novel species (Figure 3): D. hubeiensis, D. guangxiensis, and D. viniferae. Diaporthe hubeiensis (D. hubeiensis) was isolated from grapevines from Hubei province and represents 12.5% of the total isolates. This species is a sister taxon with Diaporthe alangi (D. alangi) (CFCC52556). The remaining two new taxa were isolated from grapevines from Guangxi Province. Diaporthe guangxiensis (D. guangxiensis) was represented by 11 isolates (13.54%), and it is closely associated with Diaporthe cercidis (D. cercidis) (CFCC5255). Diaporthe viniferae (D. viniferae) was represented by 8 isolates (10.41%), and its closest relative is Diaporthe pandanicola (D. pandanicola) (MFLU 18-0006).

Taxonomic Novelties

Diaporthe guangxiensis (D. guangxiensis) Dissanayake, X.H. Li & K.D. Hyde, sp. nov. (Figure 4).

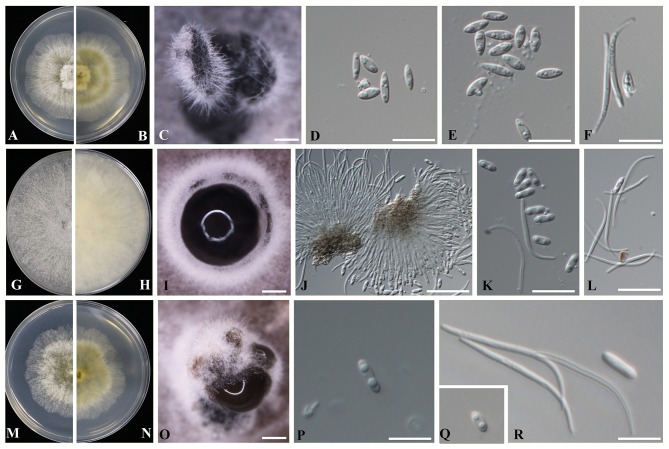

Figure 4.

Novel Diaporthe taxa identified in the present study (A–F) Diaporthe guangxiensis (A,B) Culture on PDA after 5 days; (C) Pycnidia on PDA; (D,E) Alpha conidia; and (F) Beta conidia. (G–L) Diaporthe hubeiensis (G,H) Culture on PDA after 5 days; (I) Pycnidia on PDA; (J) Conidiogenous cells for alpha and beta conidia; (K) Alpha conidia, and (L) Beta conidia. (M–R) Diaporthe viniferae (M,N) Culture on PDA after 5 days; (O) Pycnidia on PDA; (P,Q) Alpha conidia; and (R) Beta conidia. Scale bars: (D–F,J–L,P–R) = 1 mm; (C,I,O) = 10 μm.

Index Fungorum number—IF552578, Facesoffungi Number- FoF02725.

Etymology- In reference to the Guangxi Province, from where the fungus was first isolated.

Holotype—JZBH320094.

Description

Sexual morph: efforts were made to initiate sexual morphs, but various methods failed; Asexual morph: pycnidia on PDA 250-1550 μm (x = 1100 μm, n = 20) in diam., superficial, scattered on PDA, dark brown to black, globose, solitary, or clustered in groups of 3–5 pycnidia. Conidiophores aseptate, cylindrical, straight or sinuous, densely aggregated, terminal, slightly tapered toward the apex, 21–35 × 1.5–2.5 μm ( = 27 × 2 μm). Alpha conidia biguttulate, hyaline, fusiform or oval, both ends obtuse 5.3–7.8 × 1.5–3.2 μm ( = 6.8 × 2.5 μm n = 40). Beta conidia aseptate, hyaline, hamate, filiform, guttulate, tapering toward both ends 20–32 × 1–1.5 μm ( = 27 × 1.5 μm, n = 20).

Culture Characteristics

Colonies on PDA reach 70 mm diam. after 7 days at 25°C, producing abundant white aerial mycelia and reverse fuscous black.

Material Examined

CHINA, Guangxi Province, Pingguo County, on diseased trunk of V. vinifera, 3 June 2015, X.H. Li, (JZBH320094, holotype); ex-type living cultures JZB320094).

Notes: Morphological characters such as spores and colony characteristics of D. guangxiensis fit well within the species concept of Diaporthe. DNA sequence analyses of the ITS, CAL, TUB, and EF genes showed a strongly supported monophyletic lineage with 78% ML, 70% MP bootstrap values and 0.95 posterior probabilities (Figure 3). The current species has a particular neighbor relationship with D. cercidis (CFCC52566). Morphologically, D. guangxiensis has larger conidiophores (27 × 2 μm) and smaller conidia (6.8 × 2.5 μm) than D. cercidis (7–17 × 1.4–2.1 μm conidiophores; 8.6 × 3.3 μm conidia) (Yang et al., 2018). In the comparisons of five gene regions between Diaporthe guangxiensis and D. cercidis, 51.5% of 458 nucleotides across the ITS (+5.8S) had base pair differences. In addition, comparisons of the protein-coding genes showed that there were 17.3, 0.66, and 9.06% polymorphic nucleotide sites between the two species for the CAL, β-tubulin and EF-1α genes, respectively.

Diaporthe hubeiensis Dissanayake, X.H. Li & K.D. Hyde, sp. nov. (Figure 4).

Index Fungorum number—IF552579, Facesoffungi Number- FoF 02726.

Etymology- In reference to the Hubei province, from where the fungus was first isolated.

Holotype – JZBH320123.

Description

Sexual morph: efforts were made to initiate sexual morphs, but various methods failed; Asexual morph: pycnidia on PDA varying in size up to 510 μm in diam., subglobose, occurs on PDA and double-autoclaved toothpicks after 3–4 weeks, solitary or forms in groups of stroma with a blackened margin. Ostiolate, up to 100 μm black cylindrical necks. Conidiophores were reduced to conidiogenous cells. Alpha conidia hyaline, smooth, biguttulate, blunt at both ends, ellipsoidal to cylindrical, 5.6–7.1 × 1–3.1 μm ( = 6.1 × 1.8 μm n = 40). Beta conidia filiform, tapering toward both ends, scattered among the alpha conidia 17–27 × 1–1.5 μm ( = 24 × 1.5 μm n = 40).

Culture Characteristics

Colonies on PDA reach 90 mm after 10 days at 25°C (covers total surface), abundant tufted white aerial mycelia, buff, numerous black pycnidia 0.5 mm in diam. occur in the mycelium, typically in the direction of the edge of the colony; reverse buff with concentric lines.

Material Examined

CHINA Hubei Province, Wuhan, on diseased trunk of V. vinifera, 30 June 2015, X. H Li (JZBH320123, holotype); ex-type living cultures JZB320123.

Notes: In phylogenetic analysis, D. hubeiensis was placed in a well-supported clade together with D. alangi (CFCC52556), D. tectonae (MFLUCC 12- 0777) and D. tulliensis (BRIP62248b) with 100% ML, 100% MP bootstrap values and 0.99 posterior probabilities. Diaporthe hubeiensis developed sister clade with D. alangi (CFCC52556) with 99% ML, 83% MP bootstrap values and 0.99 posterior probabilities. Morphologically, Diaporthe hubeiensis has smaller conidiophores and smaller conidia (6.1 × 1.8 μm) than D. alangi (7 × 2 μm), and it has no beta conidia in D. alangi (Yang et al., 2018). Diaporthe hubeiensis differs from D. tectonae by developing wider but shorter conidia (6.1 × 1.8 μm vs 5.5 × 2.6 μm) (Doilom et al., 2017). Compared to D. tulliensis, D. hubeiensis has smaller conidia (6.1 × 1.8 μm vs 5.5–6 μm) (Yang et al., 2018). In the ITS sequence comparison between D. hubeiensis and D. alangi, 44.6% of the 461 nucleotides across the ITS (+5.8S) were different. Of the three protein-coding genes, the two species showed 4.26% and 1.16% and 5.3% polymorphic nucleotide site differences for CAL, β-tubulin and EF-1α genes, respectively.

Diaporthe viniferae Dissanayake, X.H. Li & K.D. Hyde, sp. nov.

Index Fungorum number—IF552002, Facesoffungi Number- FoF 05981.

Etymology- In reference to the host V. vinifera.

Holotype—JZBH320071.

Description

Sexual morph: efforts were made to initiate sexual morphs, but various methods failed; Asexual morph: Pycnidia on PDA 363–937 μm (x = 529 μm, n = 20) in diam., superficial, scattered, dark brown to black, globose, solitary in most. Conidiophores were not observed. Conidiogenous cells were not observed. Alpha conidia biguttulate, hyaline, fusiform or oval, both ends obtuse 5–8.3 × 1.3–2.5 μm ( = 6.4 × 2.1 μm). Beta conidia aseptate, hyaline, hamate, filiform, tapering toward both ends 23–35 × 1–1.5 μm ( = 28 × 1.3 μm n = 40).

Culture Characteristics

Colonies on PDA reach 70 mm diam. after 7 days at 25°C, producing abundant white aerial mycelia and reverse fuscous black.

Material Examined

CHINA, Guangxi Province, Pingguo County, on the diseased trunk of V. vinifera, 3 June 2015, X.H. Li, (JZBH320071 holotype); ex-type living cultures JZB320071).

Notes: In the phylogenetic analysis of D. viniferae, a strongly supported monophyletic lineage with strong 77% ML and 71% MP bootstrap values and 0.95 PP was developed (Figure 3). The current species has a particular close relationship with D. pandanicola (MFLUCC 18-0006). In the original description of D. pandanicola, morphological characteristics were not given (Tibpromma et al., 2018). Therefore, these two species were compared based on only DNA sequence data. ITS sequence comparison between D. viniferae and D. pandanicola revealed that 2.9% of the 478 nucleotide sites across the ITS (+5.8S) regions were different. Similarly, 1.7% of the β-tubulin gene fragment was different.

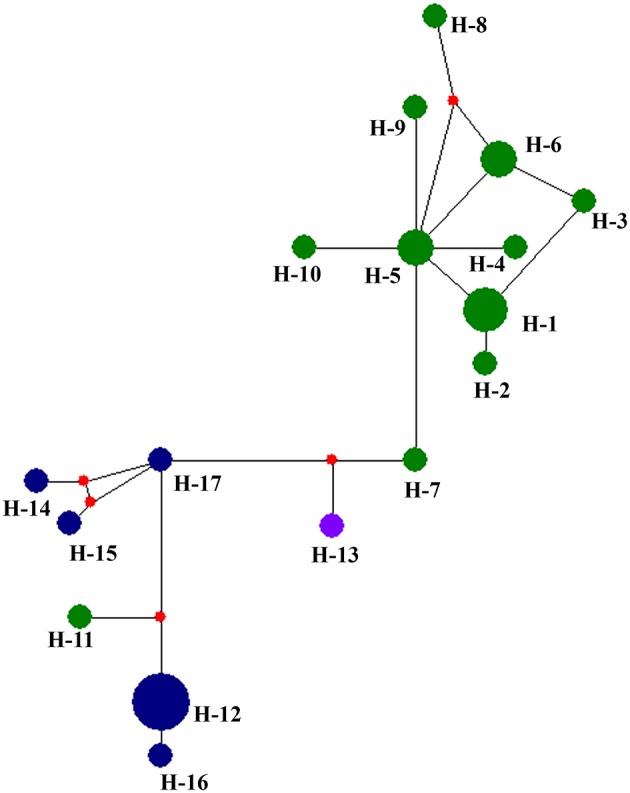

Genetic Diversity and Population Structure Analysis

Table 5 summarized the genetic diversity data of D. eres associated with grapevines which were estimated using DnaSP V.6. In the analysis, the combined data set of ITS, β-tubulin, HIS, APN, and CAL gene sequences showed 0.16226 segregation sites per sequence and a haplotype diversity of 0.955. A haplotype network was developed for the D. eres species isolated from China using Network v. 5.0 (Figure 5). The resulting network combining ITS, β-tubulin, HIS, EF-1α, and CAL gene sequences gave two main clusters according to geographic origin. In the network, isolates from Hubei province were clustered into two main clades. A single haplotype (H-11) was clustered within the main Jilin clade. Haplotype 7 (from Hubei) and h-13 (from Sichuan Province) were connected with one intermediate haplotype to the two main clusters.

Table 5.

Polymorphism and genetic diversity of Diaporthe eres strains associated with Chinese grapevines.

| Species | Gene | na | bpb | Theta-w | Sc | hd | hde | pif | TDg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. eres | ITS | 28 | 491 | 12.766 | 33 | 10 | 0.852 | 0.020 | 1.05556 |

| β-tubulin | 28 | 481 | 6 | 26 | 10 | 0.869 | 0.01362 | −0.35308 | |

| HIS | 15 | 244 | 0.04088 | 3 | 4 | 0.776 | 0.00167 | −0.5791 | |

| CAL | 17 | 399 | 0.03590 | 15 | 11 | 0.845 | 0.01391 | 0.63457 | |

| APN | 16 | 680 | 0.00906 | 11 | 5 | 0.8 | 0.00445 | −0.33503 | |

| Combine | 25 | 3247 | 0.01576 | 60 | 17 | 0.958 | 0.020 | 0.20416 |

Sample size (n).

Total number of sites (bp).

Number of segregating sites (S).

Number of alleles (nA).

Haplotypic (allelic) diversity (hd).

Average nucleotide diversity (pi).

Tajima's D (TD), (R) Estimate of R (Rm) minimum recombination events.

Figure 5.

Haplotype network generated for the Diaporthe eres isolates obtained in the present study using Network v 6.0. At each node, sizes are propionate to the number of isolates. Blue, haplotypes from Jilin; Green, haplotypes from Hubei; purple, haplotypes from Sichuan; red, Median vectors.

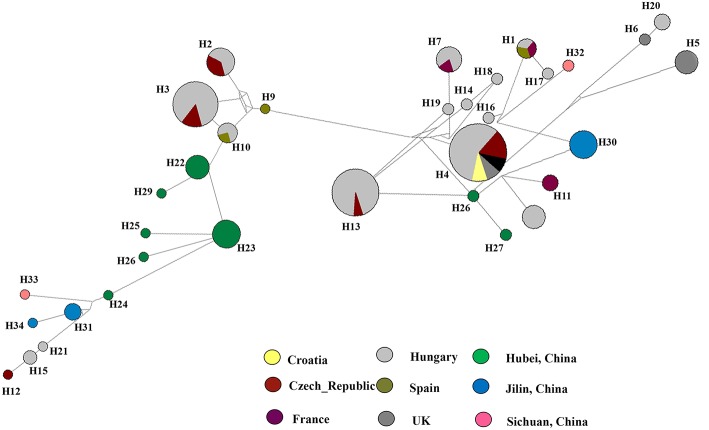

To understand the relationship between Diaporthe isolates from Chinese vineyards and those from European vineyards, we calculated recombination parameters Z and ZnS. The combined data set consists of 135 sequences with 2203 sites. The estimate of R per gene was 6.6, and the minimum number of recombination events (Rm) was 15. Median-joining networks were constructed using both single-gene data files and a combined data set of ITS, β-tubulin, HIS, EF-1α, and CAL genes. The single-gene networks differed from each other, and the resulting patterns did not give a significant grouping. Therefore, in this study, only the combined network was considered (Figure 6). A total of 33 haplotypes were identified using DnaSP, and the haplotype data file was used to generate the haplotype network. In the resulting network, we found that Chinese haplotypes and Europe haplotypes were not shared and that there was no sharing of haplotypes among different provinces in China. However, the Chinese haplotypes were dispersed in the combined network, with the majority of isolates from Hubei located in two related clusters surrounded by European haplotypes. Similarly, the haplotypes from Sichuan and Jilin provinces were also dispersed in the network and close to both European and Chinese haplotypes.

Figure 6.

Haplotype network generated for the Diaporthe eres isolates from China and European countries using Network v 6.0. At each node, sizes are proportionate to the number of isolates.

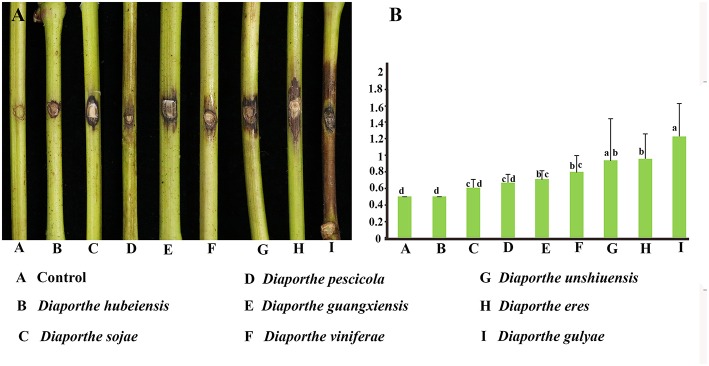

Comparative Aggressiveness Among Diaporthe Species

Pathogenicity and aggressiveness among eight Diaporthe species isolated in our study were compared by inoculating them into the V. vinifera cultivar Summer Black. The inoculated shoots did not show significant lesion development within the first 2 weeks after inoculation. Brown necrotic lesions were detected both on the tissue surface and internally, advancing upwards, and downwards through the inoculation point. Twenty-one days after inoculation, D. gulyae developed the largest lesions (1.23 cm), followed by D. eres (0.94 cm). The remaining species, D. unshiuensis, D. viniferae, D. guangxiensis, D. pescicola, and D. sojae, exhibited similar levels of aggressiveness on grape shoots (Figure 7). Diaporthe hubeiensis was the least aggressive (0.5 cm) among the eight species.

Figure 7.

Pathogenicity test results for eight Diaporthe species associated with Chinese grapevines. (A) Variation in the development of lesions. (B) Mean lesion length (cm) at 21 days after inoculation of wounded detached healthy Vitis vinifera (V. vinifera) shoots (n = 10 per species).

Discussion