Abstract

Objective:

To prospectively evaluate the effects of ospemifene on the vulva and vagina in postmenopausal women using vulvar-vestibular photography and direct visual assessments.

Methods:

Postmenopausal women (aged 40-80 years) with moderate to severe vaginal dryness as their most bothersome symptom (MBS) were randomized to daily ospemifene 60 mg or placebo in this 12-week, multicenter, double-blind, phase 3 study. Vulvar-vestibular photographic images were captured at baseline and week 12 and were independently assessed with the Vulvar Imaging Assessment Scale (VIAS). Changes from baseline in Vaginal and Vulvar Health Indices (VHI and VuHI) with ospemifene versus placebo were analyzed at weeks 4, 8, and 12. Correlations between VIAS, VHI, and VuHI, with vaginal dryness severity and the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) scores were also assessed.

Results:

In all, 631 eligible participants were randomized (ospemifene 316, placebo 315) and included in the intention-to-treat population. Compared with placebo, ospemifene significantly improved total scores for VIAS (P = 0.0154), VHI (P < 0.0001), and VuHI (P < 0.0001) from baseline to week 12; significant VHI (P < 0.0001) and VuHI (P = 0.002) improvements were observed at week 4. Most VHI and VuHI individual items were significantly better with ospemifene versus placebo at week 12 (P < 0.05). Most correlations between the vulvovaginal assessment total scores versus vaginal dryness severity and FSFI scores were significant (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Improvements observed in vulvovaginal health with ospemifene assessed by prospective vulvar-vestibular photography and other direct visual assessments support its efficacy in addition to the treatment of moderate to severe vaginal dryness due to menopause and the use of photographic and direct visual evaluations in future clinical trials.

Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Video Summary

Supplemental Digital Content 1

Keywords: Imaging, Menopause, Ospemifene, Photography, Vaginal dryness, Vulvovaginal atrophy

Low levels of estrogens during menopause have been associated with a constellation of vulvovaginal conditions, which characteristically progress without treatment.1 Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), a component of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM),2 is estimated to affect 50% of postmenopausal women.3

Vulvovaginal atrophy is associated with a number of symptoms including vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, burning, loss of vaginal secretions, leukorrhea, vulvar pruritus, feeling of pressure, itching, urethral discomfort, frequency and urgency of urination, hematuria, urinary tract infection, and dysuria.4,5 A recent cross-sectional, observational, multicenter study (AGATA) of over 900 postmenopausal women found that vaginal dryness and dyspareunia were two of the most frequently occurring symptoms of VVA.6 Surveys of menopausal women have confirmed the high prevalence of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, and highlight their negative impact on interpersonal relationships, sexual function, and overall quality of life.7-11

Ospemifene is an US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved oral selective estrogen receptor agonist/antagonist indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe dyspareunia, and most recently approved for moderate to severe vaginal dryness (January, 2019), symptoms of VVA, due to menopause.12 Ospemifene was shown to significantly improve the severity of vaginal dryness in a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, 12-week trial.13 Another large phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 12-week trial of ospemifene 60 mg once daily in postmenopausal women confirmed these results.14 Ospemifene significantly improved the severity of vaginal dryness, percentages of parabasal and superficial cells, and vaginal pH (P < 0.001 for all), and also dyspareunia severity and the FSFI (P < 0.05) compared with placebo.14 In addition, a recent pilot study used vulvoscopy to visually evaluate the effects of ospemifene on the vulva and vagina of postmenopausal women.15

Here, we report secondary endpoints of the confirmatory phase 3 study assessing ospemifene's impact on vaginal dryness, using visual assessments of the vulva and vagina, including vulvar-vestibular photography, for the first time, in a phase 3 VVA study, and post hoc correlations with vaginal dryness and the FSFI.

METHODS

Study design

This was a 12-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted at 68 sites in the United States between January, 2016 and July, 2017 (NCT02638337).14 The safety and efficacy of ospemifene versus placebo for the treatment of moderate to severe vaginal dryness were evaluated in postmenopausal women with VVA. Eligible participants were randomized 1:1 to once daily ospemifene 60 mg or matching placebo for 12 weeks. Further study design details have been previously reported.14

An independent Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study protocols and consent forms, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and current Good Clinical Practice.

The four co-primary efficacy endpoints included change from baseline to week 12 in the percentages of parabasal cells and superficial cells, vaginal pH, and severity of the MBS (vaginal dryness).14 Secondary endpoints presented here include changes from baseline to week 12 in vulvar-vestibular photography where images were independently evaluated using the Vulvar Imaging Assessment Scale (VIAS). Vaginal Health Index (VHI) and Vulvar Health Index (VuHI) assessments were also performed at each study site. Participants were given the option to withdraw consent or opt out of vulvar-vestibular photographic imaging at any time during the study.

Study participants

Postmenopausal women, aged 40 to 80 years, were eligible for participation if they had moderate to severe vaginal dryness as their self-reported MBS of VVA, ≤5% superficial cells in the maturation index of the vaginal smear, and vaginal pH >5.0. Women were defined as postmenopausal if they were aged ≥45 years and had ≥12 months since their last spontaneous menstrual bleeding; ≥6 weeks post bilateral oophorectomy; hysterectomized without oophorectomy with serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels >40 IU/L; or aged ≥45 years with an unknown date of their last spontaneous menstrual bleeding and FSH levels of >40 IU/L.

Women were excluded if they had a body mass index (BMI) ≥38 kg/m2, uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure [BP] ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg); endometrial thickness of ≥4 mm or any other clinically significant abnormal findings in the gynecological examination other than VVA; and/or used any of the prohibited concomitant medications. Other exclusion criteria are reported in the primary report of this study.14

Photographic assessment with VIAS

To prospectively record vulvar-vestibular appearance, photographs of the external genitalia, with fingers separating the labia minora, were taken at baseline and week 12, in women who consented, at each research site with a Canon SL1 camera system. Different filters were used during the photography to enhance the visualization of introital moisture. Photographs were sent to a dedicated secure central digital monitoring system, and uploaded to a dedicated clinical service repository accessed by each reviewer. If the quality of the photographs was not adequate, a re-shoot was scheduled as soon as possible, but not more than 7 days after the original shoot day. The reviewers (co-authors IG, JAS, AMK), clinical experts in the treatment of VVA and GSM, underwent technical/logistic training, then independently assessed vulvar images using a calibrated 27” high-resolution standardized color monitor in a blinded manner. Blinding included that of the participant, treatment, and sequence of visit in which the photographs were taken.

The three reviewers assessed the vulvar-vestibular photographs using the multi-item VIAS (not validated), which assessed 9 criteria: labia majora, labia minora, clitoris size, introital tissue elasticity, introital color, introital erythema, introital moisture, urethral glans prominence, and other findings. Investigators assessed introital moisture from the photos taken with and without a specialized filter. Introital elasticity was assessed by the opening of the introitus consequent with the opening of the vulva. The severity of each characteristic was graded on a scale of 0 (normal) to 3 (severe), or marked that it could not be evaluated. Scores for each of the 9 items were added for a total score for each woman. The possible range for the VIAS total score was 0 to 27, with lower values indicating better vulvar-vestibular health. Photography and the VIAS score were obtained at baseline and week 12. Median scores from the three reviewers were used for analyses.

VHI, VuHI, and other assessments

The health of the vagina was also prospectively evaluated by the investigator using the VHI,16 which, although is not a validated instrument, assessed five vaginal items: overall elasticity, fluid secretion, pH, condition of epithelial mucosa, and moisture. The severity of each characteristic was assessed using a 5-point scale and added for a total VHI score, which could range from 5 to 25, with higher VHI scores indicating better vaginal health.

Vulvar health was further prospectively visually evaluated by the investigator using the VuHI (not validated), which assessed the labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, introital tissue elasticity, color, discomfort and pain, and any other findings (eg, petechiae, excoriations, ulcers). The severity of each characteristic was scored from 0 (normal) to 3 (severe) and added for a total VuHI score that could range from 0 to 21, with lower VuHI scores indicating better vulvar health.

The VHI and VuHI were graded at baseline and weeks 4, 8, and 12. If any participant had a vaginal infection requiring medication at the time of randomization, visual evaluation was repeated after the infection was resolved and before randomization. Baseline value was taken from the infection-free time point. Evaluations of the VHI and VuHI were performed at the site, typically by the same assessor, who was blinded to the treatment but knew the participant and the timing of the visit.

Vaginal dryness was rated by women as their most bothersome symptom (recommended by the US FDA for a symptom indication17) on a 4-point scale (0, none; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe) using a validated, patient self-assessed, VVA questionnaire. The FSFI questionnaire is a brief, validated, reliable, patient-reported instrument used to assess sexual function over the past 4 weeks with 19 questions that are categorized into the 6 domains of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain.18 The FSFI was administered at baseline and at weeks 4, 8, and 12. Reported here are correlations of the FSFI scores from week 12 with the VIAS, VHI, and VuHI.

Statistical analyses

All statistical tests for this study were performed at the 0.05 significance level using two-sided tests, and all analyses were based on observed data (missing data were not imputed). All analyses were conducted in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, defined as randomized participants who received at least one dose of study medication. Changes from baseline to week 12 for the VIAS total score and changes from baseline to weeks 4, 8, and 12 for the VHI and VuHI total scores were analyzed using analysis of covariance. Baseline scores were included in the model as covariates. Post hoc analyses were conducted on the changes from baseline to week 12 for all of the individual items of the VIAS, VHI, and VuHI scores. As the investigator could not assess discomfort and pain the woman was experiencing, the score from severity of dyspareunia as the most bothersome symptom assessed by the participants was used for this item in the VIAS and VuHI. The Spearman correlation coefficient was also used post hoc to calculate correlations between the VIAS, VHI, and VuHI total scores versus vaginal dryness severity and the FSFI total score from data at week 12. Correlations were calculated separately for the two study arms in the event that correlations were in opposite directions for each treatment group.

RESULTS

Participant disposition and demographics

In all, 631 women were enrolled and randomized, and 627 were included in the ITT population (313 women for ospemifene and 314 for placebo). For the vulvar-vestibular photographic imaging analysis, 154 women from the ospemifene group and 150 from the placebo group had baseline images and reads for the VIAS total score. The primary reason for fewer women for the VIAS score versus the ITT population was lack of consent for photography.

Demographics and baseline characteristics were similar between groups (Table 1). Participants had a mean age of ∼60 years, mean BMI of 27.2 kg/m2, most were white (86%), and 59% did not have an intact uterus. Mean duration of symptoms associated with VVA was 8 to 9 years, and slightly over 50% reported severe vaginal dryness at baseline. Mean baseline VIAS, VHI, and VuHI total scores were similar between the ospemifene and placebo groups.

TABLE 1.

Participant demographics and baseline characteristics (ITT population)

| Ospemifene (n = 313) | Placebo (n = 314) | |

| Age, mean, y | 59.7 ± 6.6 | 59.8 ± 7.2 |

| BMI, mean, kg/m2 | 27.3 ± 4.5 | 27.1 ± 4.8 |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 273 (87.2) | 266 (84.7) |

| Black or African American | 38 (12.1) | 32 (10.2) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0.0) | 7 (2.2) |

| Asian | 1 (0.3) | 3 (1.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.3) | 6 (1.9) |

| No uterus, n (%) | 185 (59.1) | 182 (58.0) |

| Prior hormone therapy, n (%) | ||

| None | 305 (97.4) | 307 (97.8) |

| Oral | 5 (1.6) | 5 (1.6) |

| Vaginal | 4 (1.3) | 3 (1.0) |

| Severity of vaginal dryness at baseline | ||

| Moderate, n (%) | 148 (47.3) | 143 (45.5) |

| Severe, n (%) | 165 (52.7) | 171 (54.5) |

| Duration of VVA, mean, years | 8.36 ± 6.92 | 8.98 ± 7.79 |

| Baseline vulvovaginal health measures | ||

| VIAS | 14.44 (4.05) | 14.20 (3.76) |

| VHI | 12.98 (2.60) | 13.04 (2.65) |

| VuHI | 7.60 (3.71) | 7.67 (3.87) |

Data expressed as mean ± SD, unless stated otherwise.

BMI, body mass index; ITT, intention to treat; VHI, Vaginal Health Index; VuHI, Vulvar Health Index; VIAS, Vulvar Imaging Assessment Scale; VVA, vulvovaginal atrophy.

Photographic assessment with VIAS

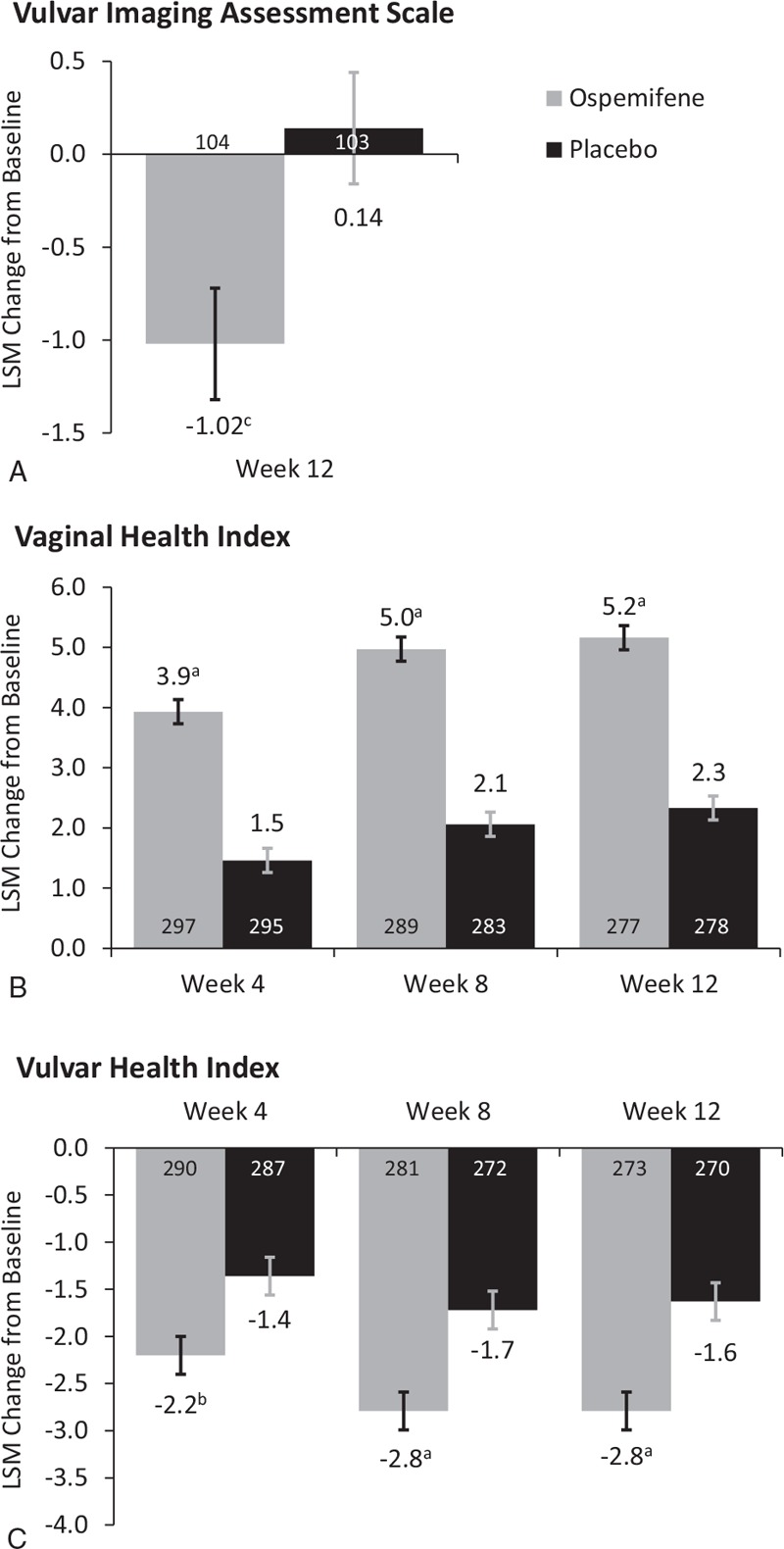

Using the VIAS, significant improvements in vulvar-vestibular health of women with ospemifene compared with placebo were seen (Fig. 1A). The difference between treatment groups in least square mean (LSM) change from baseline to week 12 in mean VIAS total score was −1.0 (P = 0.0154). Of the individual items of the VIAS, the labia minora, introital color, and introital moisture significantly improved with ospemifene versus placebo at week 12 (Table 2). The VIAS total score significantly correlated with vaginal dryness and FSFI in the placebo group but not in the ospemifene group (Table 3).

FIG. 1.

Least square mean (LSM) changes from baseline in the (A) Vulvar Imaging Assessment Scale (VIAS) total score at week 12; (B) Vaginal Health Index (VHI); and (C) Vulvar Health Index (VuHI) total scores at weeks 4, 8, and 12 (intention-to-treat population). aP < 0.0001; bP = 0.0002; cP = 0.0154 versus placebo. n's are indicated in the bars.

TABLE 2.

Least square mean (LSM) changes from baseline in total scores and individual items from the VIAS, VHI, and VuHI scores with ospemifene versus placebo at week 12

| Vulvovaginal assessments | Ospemifene (n = 313) | Placebo (n = 314) | Difference in LSM change (95% CI) | P | |

| VIAS | |||||

| Total score | Baseline mean | 14.44 ± 4.05 (n = 154) | 14.20 ± 3.76 (n = 150) | ||

| LSM change | −1.02 ± 0.31 (n = 104) | 0.04 ± 0.31 (n = 103) | −1.06 (−1.91, −0.20) | 0.0154 | |

| Labia majora | Baseline mean | 1.81 ± 0.74 (n = 172) | 1.81 ± 0.70 (n = 178) | ||

| LSM change | 0.03 ± 0.06 (n = 128) | 0.17 ± 0.06 (n = 134) | −0.14 (−0.31, 0.03) | 0.1040 | |

| Labia minora | Baseline mean | 2.15 ± 0.82 (n = 169) | 1.95 ± 0.87 (n = 178) | ||

| LSM change | −0.05 ± 0.05 (n = 126) | 0.11 ± 0.05 (n = 133) | −0.16 (−0.31, −0.01) | 0.0342 | |

| Clitoris size | Baseline mean | 1.96 ± 0.93 (n = 170) | 1.97 ± 0.95 (n = 172) | ||

| LSM change | 0.10 ± 0.08 (n = 126) | 0.04 ± 0.08 (n = 128) | 0.06 (−0.16, 0.27) | 0.6135 | |

| Introital tissue elasticity | Baseline mean | 2.06 ± 0.88 (n = 166) | 2.13 ± 0.83 (n = 177) | ||

| LSM change | −0.13 ± 0.07 (n = 119) | 0.03 ± 0.06 (n = 128) | −0.16 (−0.34, 0.02) | 0.0773 | |

| Introital color | Baseline mean | 1.70 ± 0.83 (n = 167) | 1.86 ± 0.79 (n = 175) | ||

| LSM change | −0.37 ± 0.07 (n = 121) | −0.16 ± 0.07 (n = 126) | −0.22 (−0.41, −0.03) | 0.0249 | |

| Introital erythema | Baseline mean | 1.00 ± 0.84 (n = 167) | 0.98 ± 0.81 (n = 176) | ||

| LSM change | −0.30 ± 0.06 (n = 121) | −0.19 ± 0.06 (n = 131) | −0.11 (−0.29, 0.06) | 0.2138 | |

| Introital moisture | Baseline mean | 1.68 ± 0.84 (n = 167) | 1.57 ± 0.80 (n = 175) | ||

| LSM change | −0.29 ± 0.06 (n = 124) | −0.01 ± 0.06 (n = 130) | −0.28 (−0.46, −0.10) | 0.0024 | |

| Urethral glans prominence | Baseline mean | 1.83 ± 0.74 (n = 158) | 1.92 ± 0.88 (n = 154) | ||

| LSM change | −0.21 ± 0.07 (n = 109) | −0.05 ± 0.07 (n = 105) | 0.17 (−0.36, 0.02) | 0.0862 | |

| Other findings | Baseline mean | 0.14 ± 0.49 (n = 170) | 0.20 ± 0.54 (n = 178) | ||

| LSM change | 0.10 ± 0.05 (n = 127) | 0.01 ± 0.05 (n = 132) | 0.09 (−0.04, 0.21) | 0.1849 | |

| VHI | |||||

| Total score | Baseline mean | 12.98 ± 2.60 (n = 312) | 13.04 ± 2.65 (n = 312) | ||

| LSM change | 5.16 ± 0.21 (n = 277) | 2.33 ± 0.21 (n = 278) | 2.83 (2.25, 3.41) | <0.0001 | |

| Overall elasticity | Baseline mean | 2.62 ± 0.68 (n = 312) | 2.59 ± 0.70 (n = 313) | ||

| LSM change | 0.78 ± 0.05 (n = 277) | 0.42 ± 0.05 (n = 279) | 0.36 (0.23, 0.49) | <0.0001 | |

| Fluid secretion | Baseline mean | 2.26 ± 0.77 (n = 313) | 2.34 ± 0.78 (n = 313) | ||

| LSM change | 1.10 ± 0.06 (n = 277) | 0.52 ± 0.06 (n = 278) | 0.58 (0.41, 0.74) | <0.0001 | |

| pH | Baseline mean | 1.91 ± 0.84 (n = 313) | 1.86 ± 0.86 (n = 313) | ||

| LSM change | 1.63 ± 0.07 (n = 277) | 0.52 ± 0.07 (n = 279) | 1.10 (0.90, 1.30) | <0.0001 | |

| Epithelial mucosa | Baseline mean | 3.49 ± 0.91 (n = 313) | 3.48 ± 0.89 (n = 313) | ||

| LSM change | 0.65 ± 0.04 (n = 277) | 0.35 ± 0.04 (n = 279) | 0.30 (0.18, 0.42) | <0.0001 | |

| Moisture | Baseline mean | 2.72 ± 0.76 (n = 313) | 2.76 ± 0.70 (n = 312) | ||

| LSM change | 1.00 ± 0.05 (n = 277) | 0.54 ± 0.05 (n = 278) | 0.46 (0.32, 0.60) | <0.0001 | |

| VuHI | |||||

| Total score | Baseline mean | 7.60 ± 3.71 (n = 308) | 7.67 ± 3.87 (n = 308) | ||

| LSM change | −2.79 ± 0.17 (n = 273) | −1.63 ± 0.17 (n = 270) | −1.16 (−1.63, −0.68) | <0.0001 | |

| Labia majora | Baseline mean | 0.94 ± 0.75 (n = 313) | 1.01 ± 0.83 (n = 313) | ||

| LSM change | −0.22 ± 0.03 (n = 277) | −0.11 ± 0.03 (n = 279) | −0.11 (−0.21, −0.01) | 0.0269 | |

| Labia minora | Baseline mean | 1.23 ± 0.82 (n = 313) | 1.18 ± 0.80 (n = 313) | ||

| LSM change | −0.26 ± 0.04 (n = 277) | −0.14 ± 0.04 (n = 279) | −0.11 (−0.21, −0.01) | 0.0244 | |

| Clitoris | Baseline mean | 0.94 ± 0.81 (n = 313) | 0.94 ± 0.89 (n = 313) | ||

| LSM change | −0.19 ± 0.04 (n = 277) | −0.11 ± 0.04 (n = 279) | −0.08 (−0.18, 0.02) | 0.1068 | |

| Introital tissue elasticity | Baseline mean | 1.25 ± 0.79 (n = 313) | 1.24 ± 0.78 (n = 313) | ||

| LSM change | −0.41 ± 0.04 (n = 277) | −0.22 ± 0.04 (n = 279) | −0.19 (−0.30, −0.08) | 0.0006 | |

| Color | Baseline mean | 1.22 ± 0.78 (n = 313) | 1.27 ± 0.80 (n = 313) | ||

| LSM change | −0.48 ± 0.04 (n = 277) | −0.25 ± 0.04 (n = 279) | −0.23 (−0.33, −0.12) | <0.0001 | |

| Discomfort and pain | Baseline mean | 1.72 ± 1.16 (n = 309) | 1.79 ± 1.13 (n = 309) | ||

| LSM change | −1.02 ± 0.06 (n = 274) | −0.80 ± 0.06 (n = 272) | −0.22 (−0.38, −0.06) | 0.0058 | |

| Other findings | Baseline mean | 0.36 ± 0.68 (n = 312) | 0.30 ± 0.60 (n = 311) | ||

| LSM change | −0.25 ± 0.03 (n = 276) | −0.08 ± 0.03 (n = 276) | −0.17 (−0.25, −0.10) | <0.0001 | |

Baseline mean (±SD).

LSM change, least square mean change from baseline to week 12 (±SE); SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; VHI, Vaginal Health Index; VIAS, Vulvar Imaging Assessment Scale; VuHI, Vulvar Health Index.

TABLE 3.

Correlations between VHI, VuHI, and VIAS total scores versus vaginal dryness severity or FSFI total score

| Endpoint | Treatment | Correlation (r) | P |

| Vaginal dryness severity | |||

| VIAS | Ospemifene | 0.0447 | 0.6522 |

| Placebo | 0.2008 | 0.0420 | |

| VHI | Ospemifene | −0.4134 | <0.0001 |

| Placebo | −0.2550 | <0.0001 | |

| VuHI | Ospemifene | 0.3039 | <0.0001 |

| Placebo | 0.3734 | <0.0001 | |

| FSFI total score | |||

| VIAS | Ospemifene | −0.0150 | 0.8831 |

| Placebo | −0.2648 | 0.0075 | |

| VHI | Ospemifene | 0.3029 | <0.0001 |

| Placebo | 0.3054 | <0.0001 | |

| VuHI | Ospemifene | −0.2882 | <0.0001 |

| Placebo | −0.1606 | 0.0105 | |

FSFI, Female Sexual Function Index; VHI, Vaginal Health Index; VIAS, Vulvar Imaging Assessment Scale; VuHI, Vulvar Health Index.

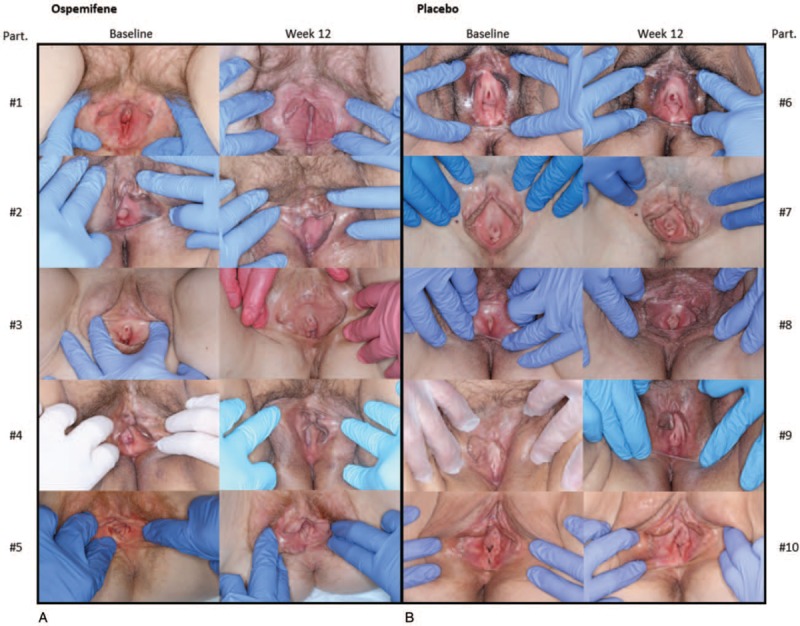

Figure 2 shows representative vulvar-vestibular images from women before and after receiving ospemifene and placebo for 12 weeks. In Fig. 2A, changes with ospemifene can be seen, including increased labia minora tissue (participants #1 and #5), reduced erythema of the distal urethral meatus (participant #1), reduced distal urethral prominence (participant #2), decreased vestibular petechiae (participant #2), decreased vestibular pallor (participant #3), resolved introital stenosis (participant #4), and reduced telescoping (prominence) of the urethra (participant #4). Images of women in the placebo group consistently showed no improvement of the clinical signs of GSM (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Representative vulvar-vestibular images for the Vulvar Imaging Assessment Scale (VIAS) assessment of participants before and after ospemifene (A) and before and after placebo (B) for 12 weeks. Part., participants.

VHI and VuHI assessments

Significantly greater improvements in mean total VHI scores with ospemifene versus placebo were observed at week 12, and were seen as early as week 4; differences in the LSM changes from baseline were 2.5 at week 4, 2.9 at week 8, and 2.8 at week 12 (all P < 0.0001; Fig. 1B). All of the individual items of the VHI, including overall elasticity, fluid secretion, pH, epithelial mucosa, and moisture significantly improved with ospemifene compared with placebo at week 12 (Table 2), and also at weeks 4 and 8 (P < 0.0001).

Similarly, VuHI significantly improved with ospemifene compared with placebo, with differences in the LSM changes of −0.8 at week 4 (P = 0.0002), −1.1 at week 8 (P < 0.0001), and −1.2 at week 12 (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1C). Ospemifene also significantly improved six of the seven individual items for the VuHI, including the labia majora, labia minora, introital tissue elasticity, color, discomfort and pain, and other findings at week 12 (Table 2). Except for the labia majora at week 4 and discomfort and pain at week 8, these six items were also significantly better with ospemifene than placebo at weeks 4 and 8 (P < 0.05).

The correlations were significant between total VHI and VuHI scores versus vaginal dryness severity in the ospemifene and placebo groups (Table 3). Similarly, significant correlations were observed between VHI and VuHI total scores versus FSFI total score with both ospemifene and placebo groups.

DISCUSSION

Ospemifene was found to prospectively improve vulvovaginal health in women with an MBS of moderate to severe vaginal dryness in a large phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial.14 Significant improvements with ospemifene versus placebo were found in the visual evaluations of VIAS with vulvar and vestibular photography, VHI, and VuHI. Noteworthy is the fact that we observed, through the use of photography, restoration of vulvar, vaginal, and urethral structures with ospemifene. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time the prospective use of vulvar-vestibular photographic imaging has been used to assess vulvar-vestibular health in a phase 3 pivotal clinical trial, and in such a large cohort of women (n = 304). In addition, the investigator-assessed outcomes of VHI and VuHI correlated with the participant-reported outcomes of vaginal dryness and FSFI.

The visual improvements in the appearance of the vulva and vagina in our phase 3 study are consistent with data published by one of the authors (IG) from a small (n = 8), open-label, single-center, 20-week, investigator-initiated, pilot research study.15 This pilot study prospectively evaluated the effects of ospemifene on the vulva, vestibule, urethral meatus, and vaginal introitus over 20 weeks using vulvoscopy in women with moderate to severe dyspareunia from menopause.15 Assessment using the Vulvoscopic Genital Tissue Appearance Scale showed that ospemifene significantly improved urethral meatal prominence, introital stenosis, vestibular pallor, vestibular erythema, mucosal moisture, vaginal rugation, and anterior wall prominence.15 Indeed, the vulvar-vestibular photographic images we have included here (Fig. 2) suggest that ospemifene may have the ability to restore or regrow some vulvar structures, specifically the labia minora. Such a benefit, to our knowledge, has not been reported with any other selective estrogen receptor modulator, and, if confirmed by others, may differentiate ospemifene from the other approved treatments for VVA and GSM. Because some vulvar and vaginal tissues have both estrogen and androgen receptors, the ability of ospemifene to stimulate synthesis of androgen-dependent structural and functional proteins through estrogen-androgen receptor cross-talk has been suggested.15,19 Whether certain anatomic improvements observed with ospemifene are estrogenic, androgenic, or growth factor-related, or reflect a combination of these elements, requires further research.

A strength of this study lies in the prospective visual assessment of vulvar-vestibular changes with ospemifene in the largest cohort of women who participated in photography of the vulva and vestibule. Photographic images allowed us to observe, heretofore not done, structural changes to the vulva and urethra with a treatment for GSM. Use of photographic images in clinical trials creates a permanent medical record that enables clinicians to have clear communication with women regarding their condition, and can facilitate assessment of treatment impact during follow-up visits.20 In addition, prospective photographs can be an essential component of a comprehensive clinical evaluation as they can detect even minor abnormalities or those that cannot be identified by questionnaire. Images can also be shared and discussed with postmenopausal women.21 By proactively engaging women in conversations about their symptoms such as vaginal dryness and dyspareunia through images, clinicians may enhance women's motivation to consider treatment by discussing available options.22 Most recently, based on the pilot study described above, the inclusion of vulvoscopy as a measure of genitourinary tissue health in clinical trials assessing the safety and efficacy of dyspareunia treatment for menopausal women was recommended.15 The authors of a report of vaginal estradiol use similarly concluded that visual assessments of the vagina performed by experienced healthcare professionals may be a useful tool to diagnose VVA and assess response to treatment.22

Significant correlations of visual vulvar-vestibular examinations with the severity of vaginal dryness reported here further support the use of visual inspection to assess VVA in postmenopausal women. More specifically, we found the visual assessments of VHI and VuHI to weakly-to-moderately correlate with the subjective measures of vaginal dryness severity and the FSFI questionnaire in ospemifene and placebo-treated women. Another report that included visual inspection of the vagina by the investigator after treatment with a vaginal estradiol insert found improvements in vaginal color, epithelial integrity, epithelial surface thickness, and secretions, which collectively were significantly correlated with the subjective measures of dyspareunia and vaginal dryness.22 Correlations of the VIAS with vaginal dryness and FSFI in our study were not significant in women treated with ospemifene, in contrast to the significant correlations of the VHI and VuHI with these parameters. Several differences in methodologies, and thus bias and variability, were inherent between the VHI/VuHI and VIAS assessments, and may explain the difference in their correlation results. For the VHI and VuHI, each investigator assessed them at their own site, and while blinded to treatment, they were not blinded to the sequence of the study visit or knowledge of the woman being treated. In contrast, the photographs for the VIAS were independently assessed by three consultants/co-authors with different backgrounds who were trained by a specific protocol and blinded to treatment, and also each other's image readings and the visit sequence. Furthermore, these investigators had no contact with the trial participants. In addition, correlating subjective measures with an investigator-assessed measure such as the VIAS is difficult, especially with the higher variability of an active treatment effect compared with the less variable placebo effect of declining vaginal health, consistently identified by three independent reviewers, and as seen with the significant correlation between the VIAS score and vaginal dryness severity and FSFI scores in the placebo group.

One of the primary limitations was that the VIAS, VHI, and VuHI were not validated instruments. While the VHI was developed in the 1990s16 and has been used extensively in the medical literature, use of the VuHI and VIAS is less evident. Ideally, validation of these instruments would strengthen the argument for their use in clinical studies. Another limitation of the study is the bias in the VHI and VuHI assessments, given that investigators see the patient, know the sequence of treatment, and may be able to guess the treatment administered. However, such biases are inherent in any clinical trial. Indeed, validation of the VIAS would lend further support to using vulvar and vestibular photography for diagnosing VVA in the clinical setting. Another limitation lies in the item of discomfort and pain of the VuHI. As discomfort and pain could not be assessed by the investigator, the vaginal dryness score rated by the study participants was used for that item of the VuHI. In addition, the subjectivity of some of the VIAS measures could be criticized. Visualization of introital moisture and assessing introital elasticity may be too subjective. Further, the item of “Other findings” in the VIAS and VuHI may not be useful to convey the clinical significance of the effects of ospemifene over placebo given their lack of structure. The demographic characteristics of the participants of this study may also limit the conclusions of the study as they were mostly white women in good health with a mean BMI of 27 kg/m2.14 Because these women may not represent the general population of postmenopausal women,14 the benefits and correlations observed in this study may also not be applicable to postmenopausal women in the general population. Despite the narrow inclusion criteria, our results are consistent with the improvement of vaginal dryness as the MBS of postmenopausal women with VVA reported in phase 3 studies. Finally, some physicians may not find use of photography feasible without professional-grade equipment; however, some electronic medical record applications for smartphones allow the capture of good-quality images in the clinical setting.

In our study, a new non-PRO outcome measure, prospective vulvar-vestibular photography, was assessed for the first time in this large, multicenter, phase 3 trial. Critical physical improvements with ospemifene could be noted for the first time using the 4-point scale of the VIAS (Fig. 2). Figure 2 also supports no improvement in vulvar and vestibular health with placebo, despite the participants’ ability to use moisturizers and/or lubricants during the study.14 While more research and validation of the 9-item VIAS are needed, the proposed clinical benefit of using “snap-shot” photographic views of women's vulvar and vestibular physical examinations may be of clinical interest.

CONCLUSIONS

Significant improvements observed here in the visual vulvar and vaginal outcome scores may extend the benefits of ospemifene with respect to the primary endpoints previously reported for this phase 3 study, suggesting that vulvar tissue improved in addition to the efficacy of ospemifene in treating the MBS of moderate to severe vaginal dryness due to menopause. By using the VIAS with vulvar-vestibular photography along with VHI, and VuHI to assess the effects of ospemifene on the vulva and vagina, novel visual strategies are presented that may be useful for assessing VVA in postmenopausal women in the clinic or in future VVA studies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Data presentation: Presented at The North American Menopause Society annual meeting, October 3 to 6, 2018, San Diego, CA.

Funding/support: This study was sponsored by Shionogi Inc. and Duchesnay Inc. Medical writing support was provided by Shilpa Lalchandani, PhD, and Kathleen Ohleth, PhD, of Precise Publications, LLC and was funded by Duchesnay Inc.

Financial disclosure/conflicts of interest: Dr Goldstein has received research support from AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Endoceutics, Ipsen, Strategic Science & Technologies, and Valeant; has received fees for consulting/advisory boards from Duchesnay Inc, Ipsen, Shionogi Inc, Sprout, and Strategic Science & Technologies; and is on the speakers bureau of AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Deka, and Duchesnay Inc. Dr. Simon has served (within the past year or current) as consultant/advisor to AbbVie, Allergan plc, AMAG, Amgen, Ascend Therapeutics, Bayer Healthcare, CEEK Enterprises, Covance, Dare Bioscience, Duchesnay, Hologic, KaNDy/NeRRe Therapeutics, Mitsubishi Tanage, ObsEva SA, Palatin Technologies, Sanofi SA, Shionogi, Sprout, and TherapeuticsMD; has received (within the past year or current) grant/research support from AbbVie, Agile Therapeutics, Allergan plc, Bayer Healthcare, Endocuetics, GTx, Ipsen, Myovant Sciences, New England Research Institute, ObsEva SA, Palatin Technologies, Symbio Research, TherapeuticsMD, and Viveve Medical; has served (within the past year or current) on the speaker's bureaus of AbbVie, AMAG, Duchesnay, Novo Nordisk, Shionogi, and TherapeuticsMD; and is a stockholder (direct purchase) in Sermonix. Dr. Kaunitz has served (within the past three years or current) as a consultant to or on the advisory boards of Allergan, AMAG, Mithra, Pfizer; and Shionogi and has received research support (to University of FL) from Bayer Healthcare, Endoceutics and TherapeuticsMD. Dr. Altomare and Yuki Yoshida are employees of Shionogi, and Dr. Zhu was an employee of Shionogi at the time of the study. Drs. Schaffer and Soulban are employees of Duchesnay Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kingsberg S, Kellogg S, Krychman M. Treating dyspareunia caused by vaginal atrophy: a review of treatment options using vaginal estrogen therapy. Int J Womens Health 2010; 1:105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarrel PM, Portman D, Lefebvre P, et al. Incremental direct and indirect costs of untreated vasomotor symptoms. Menopause 2014; 22:260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon JA, Altomare C, Cort S, Jiang W, Pinkerton JV. Overall safety of ospemifene in postmenopausal women from placebo-controlled phase 2 and 3 trials. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018; 27:14–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nappi RE, Panay N, Bruyniks N, Castelo-Branco C, De Villiers TJ, Simon JA. The clinical relevance of the effect of ospemifene on symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Climacteric 2015; 18:233–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jannini EA, Nappi RE. Couplepause: a new paradigm in treating sexual dysfunction during menopause and andropause. Sex Med Rev 2018; 6:384–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palma F, Xholli A, Cagnacci A. as the writing group of the Agata study. The most bothersome symptom of vaginal atrophy: Evidence from the observational AGATA study. Maturitas 2018; 108:18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kingsberg S, Krychman M, Graham S, Bernick B, Mirkin S. The Women's EMPOWER Survey: Identifying women's perceptions on vulvar and vaginal atrophy (VVA) and its treatment. J Sex Med 2017; 14:413–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nappi RE, Palacios S, Panay N, Particco M, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in four European countries: evidence from the European REVIVE Survey. Climacteric 2016; 19:188–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon JA, Kokot-Kierepa M, Goldstein J, Nappi RE. Vaginal health in the United States: results from the Vaginal Health: Insights, Views and Attitudes survey. Menopause 2013; 20:1043–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women's VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med 2013; 10:1790–1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Vaginal health: Insights, views & attitudes (VIVA): results from an international survey. Climacteric 2012; 15:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osphena( [(Ospemifene) Tablets, for Oral Use] Prescribing Information. Florham Park, NJ: Shionogi Inc; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portman D, Palacios S, Nappi RE, Mueck AO. Ospemifene, a non-oestrogen selective oestrogen receptor modulator for the treatment of vaginal dryness associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Maturitas 2014; 78:91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Archer DF, Goldstein SR, Simon JA, et al. Efficacy and safety of ospemifene in postmenopausal women with moderate-to-severe vaginal dryness: a phase 3, randamized, double-blind placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Menopause 2019; 26:611–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein SW, Winter AG, Goldstein I. Improvements to the vulva, vestibule, urethral meatus, and vagina in women treated with ospemifene for moderate to severe dyspareunia: a prospective vulvoscopic pilot study. Sex Med 2018; 6:154–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bachmann G. Urogenital ageing: an old problem newly recognized. Maturitas 1995; 22 Suppl:S1–S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Department of Health and Human Services (FDA). Guidance for Industry: Estrogen and Estrogen/Progestin Drug Products to Treat Vasomotor Symptoms and Vulvar and Vaginal Atrophy Symptoms: Recommendations for Clinical Evaluation; 2003. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/informationbyDrugClass/UCM135338.pdf Accessed December 21, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther 2000; 26:191–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traish AM, Vignozzi L, Simon JA, Goldstein I, Kim NN. Role of androgens in female genitourinary tissue structure and function: implications in the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Sex Med Rev 2018; 6:558–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hossam DAS, Wagih A, Malik M. Clinical photography of skin diseases. Egypt Dermatol Online J 2015; 11:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhattacharya S. Clinical photography and our responsibilities. Indian J Plast Surg 2014; 47:277–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon JA, Archer DF, Kagan R, et al. Visual improvements in vaginal mucosa correlate with symptoms of VVA: data from a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Menopause 2017; 24:1003–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.