Abstract

Background and Aim:

Preferences of service users is an important consideration for developing health-care services. This study aimed to assess the experiences of the patients with substance use disorders who were admitted to a tertiary health-care facility in India.

Method:

This cross-sectional sectional study recruited adult inpatients who stayed for a period of 7 days or more. The Picker Patient Experience questionnaire (PPE-15) was used to gather information about the views of the patients about the care received at the center.

Results:

Responses were available from 113 inpatients. Majority of the participants were males and were dependent on opioids. The experience was generally positive about being treated with respect and dignity and access to information. The participants were most satisfied with opportunity being given to discuss anxiety and fear about the condition or treatment (91.2% positive response) and least satisfied with differences in responses from doctors and nurses (43.4% positive response). Further attention seemed desired about communication with the staff and patients’ involvement in their own treatment-related decision-making.

Conclusion:

Efforts need to be made to involve patients in their own treatment-related decision-making and to improve communication with the treatment team. This might lead to better involvement in treatment process, which could enhance the treatment outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: patient experience, PPE-15, substance abuse, user involvement, communication, quality improvement

Introduction

Among various aspects of mental health services, inpatient care component is probably the one which brings consumers in closest contact with service providers. There is an increasing need to deliver higher quality care to all, with due regard and evaluation of the inpatient experiences of the service user (1). Patient experience reflects the occurrences and events that happen independently and collectively across the continuum of care. Currently, patient experience has gained acceptance as it provides more comprehensive and meaningful account than satisfaction surveys (2,3). Positive patient experience of care is recognized to be a proxy indicator of quality in health-care provision and is associated with improved patient outcome and better patient compliance. In turn, it reflects higher levels of morale within the health-care workforce (4).

To improve upon quality, measuring the patient experience of care fosters delivery of patient-centered services. Quality improvement efforts aimed at enhancing patient experiences may also benefit clinical quality by providing patient-centered care. Such initiatives to improve patient centeredness can be both low cost and high value. Understanding the perspective of the service users remains essential in contemporary health care in order to identify the extent to which a service is achieving its aims and purpose. It has been highlighted that users and carers are major stakeholders in the service delivery and as such must be regarded as participants rather than simply the recipients of mental health care (5).

Over the last 2 decades, there have been great efforts to involve people in their care planning through explicitly empowering the consumers in the mental health policies across the world. Legislations have advocated greater service user involvement, thereby modernizing the mental health workforce, viewing the person beyond illness, and facilitating their choice of treatments (6 –8). However, such policies have yet to find firm grounds in developing countries like India where care is quite paternalistic and involvement of patients in decision-making relating to their care process is limited (9). The care process and funding mechanisms for treatment of individuals in this country of billion plus population is quite different from other parts of the world. The new Mental Health Care Act (2017) envisages a better access to care and greater role of the patient in deciding the course of treatment. Yet, the Act has been considered too progressive and somewhat out of keeping with the present circumstances (10).

Inpatient care for patients with substance use disorders offers unique challenges and there can be instances of treatment cessation before completion due to range of issues. In this context, patients’ experience provides valuable insight about how the service users perceive the treatment in such a service provision context. Shame and a sense of personal failure may lead to postponement of accessing the service (11). However, positive experience of continuous care can lead to better compliance and ultimately provide better outcomes to these patients. Assessment of patient experiences also provides benchmarking for introduction of specific quality improvement measures in providing patient-centered care. However, evidence in relation to the patient experience of care is severely constrained from the developing world. Thus, this study was planned to assess patient experiences among inpatients at a tertiary care substance use disorder treatment facility in India.

Methodology

Setting and Participants

This was a cross-sectional observational study which was conducted at a tertiary care treatment center in North India. The center is an apex facility for the treatment of drugs and substance abuse disorders in India. The center has a role in developing service delivery models for the country, is actively engaged in training and capacity building for substance use disorders, pursues research, and has a key role in policy and planning initiatives.

The clientele of the center comprises of patients from various states of North India. The center follows a medical model of treatment and has both outpatient and inpatient services. The patients are either referred to the center or seek services on their own accord or suggestion of family members and acquaintances. A team of doctors, nurses, psychologists, social workers, and other ancillary personnel are involved in provision of care. The clientele primarily comprises of patients with opioid use disorders and alcohol use disorders. Treatment initially focuses on detoxification followed by maintenance and relapse prevention. Treatment is substantially subsidized through government funding. The present study was conducted in the inpatient setting of the center. The inpatient facility of the center has 50 beds with average bed occupancy of 80%. The average length of stay for patients is about 12 days.

The inclusion criteria for the participants for the present study were as follows: (1) age 18 years and above, (2) patient having a diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence, (3) admitted in the ward for a period of minimum 7 days, and (4) willing to provide informed consent. Patients who were intoxicated or were in acute withdrawal or those who had severe pain were excluded from the study. Sample size in the study aimed for 113 inpatients, which was calculated with the power of 0.80 and alpha of 0.05, with sampling ratio of roughly 10:1 based upon previous findings of patient experience in a different context (12).

Procedure

Eligible service users as per the inclusion and exclusion criteria who provided informed consent were recruited in the study. Patients were recruited after at least 7 days of inpatient stay when their withdrawal symptoms were controlled. Service users, who were not experiencing significant discomfort, were offered participation. In case the family members were staying with the patient, then their concurrence was also taken. After taking informed consent, the participants filled a questionnaire handed over by the nursing staff. The participants were given due privacy for responding to the questions. The filled questionnaires were subsequently collected. Data collection was carried out between July 2016 and February 2017. The study was approved by the institute ethics committee vide Ref. No. IECPG/318/27.04.2016, RT-35/29.06.2016.

The questionnaire enquired about basic information about the demography and substance use problems. The substance use diagnoses were ascertained from the treatment records. For eliciting patient service experience, the participants were administered the Picker Patient Experience questionnaire (PPE-15). This is a 15-item questionnaire with high levels of internal consistency and reliability and promising evidence of both the face and criterion validity (12) (available online as a Supplemental file). It has been used internationally for measuring patient’s hospital experience for the purpose of benchmarking care quality. The PPE-15 assesses 8 key aspects of the care: (1) information and education, (2) coordination of care, (3) physical comfort, (4) emotional support, (5) respect for patient preference, (6) involvement of family and friends, (7) continuity and transition, and (8) overall impression. In the survey, a problem is defined as an aspect of health care that could, in the eyes of the patient, be improved upon. Questions are asked with a range of possible responses that are subsequently turned into a binary outcome reflecting the presence of a problem or not, within the questioned domain. Based on these binary responses, the proportion of patients with or without problem were calculated for each question. The advantage of using this instrument is that it not disease-specific and can be used in a host of settings. A Hindi translation of instrument was made through back-translation method as majority of the participants were conversant with Hindi language and translation was deemed adequate.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 21 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York). Descriptive statistics in the form of mean, standard deviation, frequencies, and percentages were used to represent the descriptive data. The responses to PPE-15 were segregated into dichotomous (adequate or not adequate/lacking). These responses were then compared with the variables of age, education, and substance-related diagnosis. Mann-Whitney U test and χ2 test were used for comparisons of each of the items of PPE-15 with age, education, and substance-related diagnosis (opioid or alcohol dependence), respectively. A P value of less than .05 was considered significant and missing value imputation was not conducted.

Results

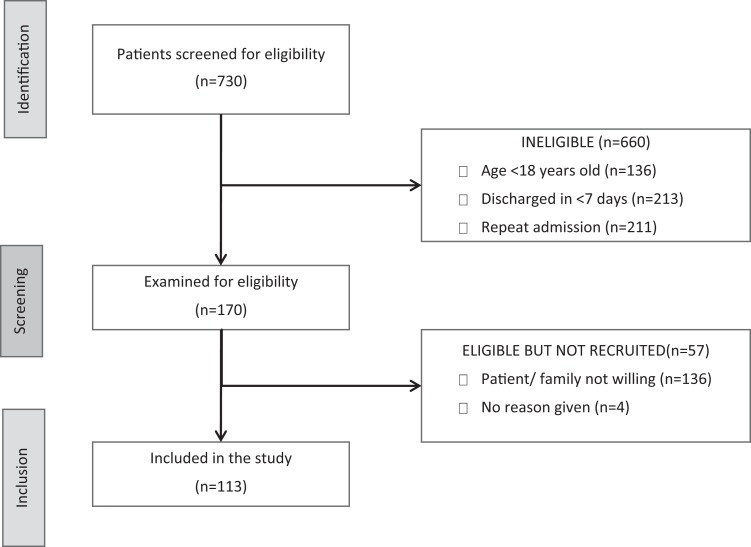

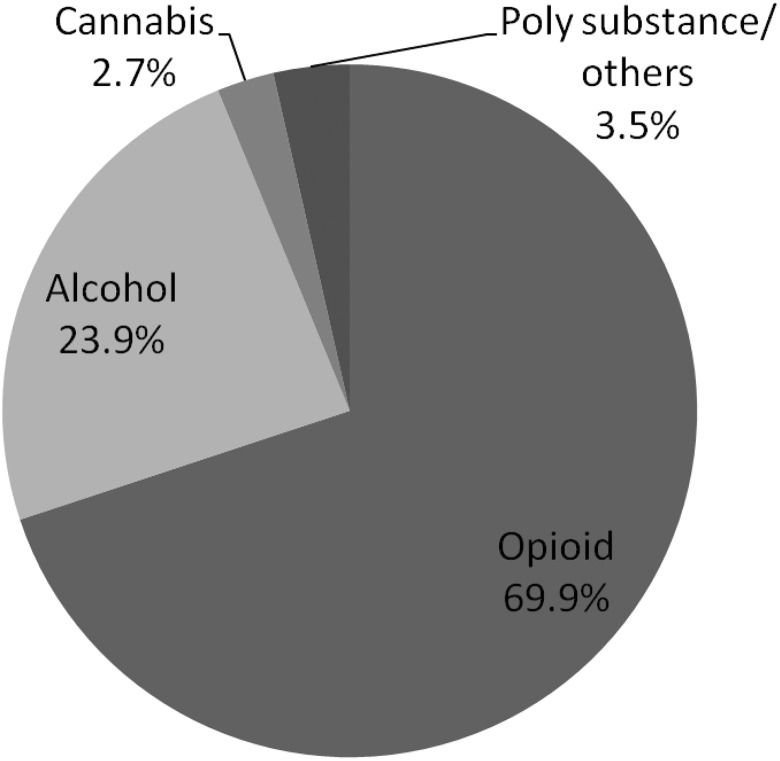

The sample comprised of 113 individuals admitted to the inpatient services (Figure 1). The key characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. An overwhelming majority of the respondents were males. About a third of the respondents were educated up to primary school, while a minority were educated till graduate and postgraduate levels. The admission diagnosis was most commonly opioid dependence syndrome, followed by alcohol dependence syndrome, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Patients.

| Variable | Mean (Standard Deviation) or Frequency (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| Age in years | 31.5 (±10.9) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 112 (99.1%) |

| Female | 1 (0.9%) |

| Education | |

| Primary | 34 (30.1%) |

| High school | 15 (13.3%) |

| Higher secondary | 48 (42.5%) |

| Graduate | 12 (10.6%) |

| Postgraduate | 4 (3.5%) |

Figure 2.

Substance use disorders.

The responses to the PPE-15 are presented in Table 2. Doctors’ and nurses’ answers to the questions were not clear in about 15% of the sample. However, conflicting information was given by staff in more than half of the patients. Also, about half of the patients reported that doctors talked in front of them as if they weren’t there. Additionally, a large majority of the participants reported that they wanted to be involved in decision-making of their care. The patients did endorse that they were treated with dignity and respect, and their anxieties and fears about treatment were allayed by the doctors and nurses. More than two-thirds of the participants did report that the hospital staff talked about their concerns and managed the pain when it emerged. Also, most patients endorsed that a family member or someone close got the opportunity to talk to the doctors and got the information as desired. Generally, the patients endorsed that they were told about the purpose of medications, the side effects to watch for, and the danger signals about the illness when they went home. The participants were most satisfied with opportunity being given to discuss anxiety and fear about the condition or treatment (91.2% “adequate” response) and least satisfied with differences in responses from doctors and nurses (43.4% “adequate” response).

Table 2.

Responses on Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire.a

| Question | Response, n (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. When you had important questions to ask a doctor, did you get answers that you could understand? | |

| Yes, always | 98 (86.7%) |

| Yes, sometimes | 13 (11.5%) |

| I had no need to ask | 2 (1.8%) |

| 2. When you had important questions to ask a nurse, did you get answers that you could understand? | |

| Yes, always | 95 (84.1%) |

| Yes, sometimes | 16 (14.2%) |

| I had no need to ask | 2 (1.8%) |

| 3. Sometimes in a hospital, one doctor or nurse will say one thing and another will say something quite different. Did this happen to you? | |

| Yes, often | 45 (39.8%) |

| Yes, sometimes | 19 (16.8%) |

| No | 49 (43.4%) |

| 4. If you had any anxieties or fears about your condition or treatment, did a doctor discuss them with you? | |

| Yes, completely | 103 (91.2%) |

| Yes, to some extent | 9 (8.0%) |

| I didn’t have any anxieties or fears | 1 (0.9%) |

| 5. Did doctors talk in front of you as if you weren’t there? | |

| Yes, often | 36 (32.1%) |

| Yes, sometimes | 18 (16.1%) |

| No | 58 (51.8%) |

| 6. Did you want to be more involved in decisions made about your care and treatment | |

| Yes, definitely | 79 (69.9%) |

| Yes, to some extent | 20 (17.7%) |

| No | 13 (11.5%) |

| 7. Overall did you feel you were treated with respect and dignity while you were in the hospital | |

| Yes, always | 97 (85.8%) |

| Yes, sometimes | 15 (13.3%) |

| No | 1 (0.9%) |

| 8. If you had any anxieties or fears about your condition or treatment, did a nurse discuss them with you? | |

| Yes, completely | 78 (69.6%) |

| Yes, to some extent | 23 (20.5%) |

| No | 3 (2.7%) |

| I didn’t have any anxieties or fears | 8 (7.1%) |

| 9. Did you find someone on the hospital staff to talk about your concerns | |

| Yes, definitely | 78 (69.6%) |

| Yes, to some extent | 18 (16.1%) |

| No | 11 (9.8%) |

| I had no concerns | 5 (4.5%) |

| 10. Were you ever in pain | |

| Yes | 100 (88.5%) |

| No | 13 (11.5%) |

| Do you think the hospital staff did everything they could to help control the pain | |

| Yes, definitely | 81 (87.1%) |

| Yes, to some extent | 11 (11.8%) |

| No | 1 (1.1%) |

| 11. If your family or someone else close to you wanted to talk to the doctor, did they have enough opportunity to do so? | |

| Yes, definitely | 91 (81.3%) |

| Yes, to some extent | 11 (9.8%) |

| No | 4 (3.6%) |

| No family or friend were involved | 3 (2.7%) |

| My family didn’t want or need information | 3 (2.7%) |

| 12. Did the doctors or nurses give your family or someone close to you all the information they needed to help you recover? | |

| Yes, definitely | 96 (87.3%) |

| Yes, to some extent | 5 (4.5%) |

| No | 3 (2.7%) |

| No family or friend were involved | 2 (1.8%) |

| My family didn’t want or need information | 4 (3.6%) |

| 13. Did a member of staff explain the purpose of the medicines you were to take at home in a way you could understand? | |

| Yes, completely | 102 (91.1%) |

| Yes, to some extent | 7 (6.3%) |

| No | 3 (2.7%) |

| 14. Did a member of staff tell you about medication side effects to watch for when you went home? | |

| Yes, completely | 95 (85.6%) |

| Yes, to some extent | 7 (6.3%) |

| No | 7 (6.3%) |

| I didn’t need an explanation | 2 (1.8%) |

| 15. Did someone tell you about the danger signals regarding your illness or treatment to watch for after you went home? | |

| Yes, completely | 98 (87.5%) |

| Yes, to some extent | 4 (3.6%) |

| No | 10 (8.9%) |

a Some of the participants did not respond to all the questions. Missing data imputation not conducted.

Further exploratory analyses were conducted to assess whether age, education, and substance-related diagnoses had a relationship with the items of PPE-15. It was seen that education had a relationship with nurses’ answers to questions being understood, and those with higher education were more likely to be dissatisfied with responses from the nurses (Mann-Whitney score, U = 451.5, P = .015). As compared to patients with alcohol dependence, patients with opioid dependence more frequently endorsed that they were not explained about the danger signals of the illness after they went home (χ2 = 5.592, Fisher exact P = .019). Other responses were not associated with age, education, and the substance-related diagnosis.

Discussion

The study aimed to present the patient experiences among those who were admitted for the treatment of substance use disorders. The findings suggest that though patients were largely satisfied with treatment, some issues were of concern to the patients. The study suggests that though patients were treated with dignity and respect, and their anxieties were allayed, certain attitudinal and procedural issues did arise. The information given by the staff seemed conflicting and a greater involvement in decision-making was desired by the patients. Furthermore, it was remarked that doctors talked in front of the patients as if they were not there. In this study, it is evident that the patient received immediate care, stated by the fact that pain was treated adequately. Also, the information about the disease and medication was provided and the health-care professionals answered queries in a manner in which the patient could understand. The other concerns of the patient, such as limited information on medication and lack of choice of treatment, are not evident in our study. This was contradictory to a study from the United Kingdom (13).

Cognizance needs to be made of underrepresentation of females in the study, as females are generally underrepresented among inpatient service users (14 -16). Also, treatment seekers primarily comprising of opioid and alcohol users reflect the substance use profile in the region.

Toward Betterment of Services

Echoing the present findings, an integrative review suggests that being valued and connected to the staff is an important component of the service users’ treatment program (8). Inpatient treatment services are sometimes considered restrictive and vulnerable to manifest power differential and use of coercion (1). Hence, there is a need to be aware of the value placed on professionalism and dealing with dignity.

It has been documented that patients want more communication with the care providers. Trust in the service provider is an important component in the improved health of the patient, as service users already are often stigmatized due to their diagnoses (17). It has been stressed that service users’ anxieties and fears can be mitigated by positive relationship with service provider (18). Health-care professionals playing a role in effectively allaying the anxiety of the patient was a positive outcome of the study.

However, concerns were raised about limited role of the service user in treatment decision-making. One has to be cautious about the power differential between service user and provider in the health-care setting and constantly guard against fear playing a role in inhibiting shared decision-making (1,13,19). Differences in viewpoints of service user and service provider can result in difficult engagement. A balance needs to be achieved between medical problem focus of the service providers and psychosocial concerns of the patients (20). The service users wanting more involvement in the care and decision-making process are also echoed in findings from Veterans Affairs Medical Centre and in Saudi Arabia (21,22). One of the reasons could be the gradual attitudinal changes with relegation of paternal attitudes of care and probably the information-based empowerment of the service users as they embrace the digital age. Health-care professionals also need to change their modes of conduct keeping pace with the current developments and encourage a collaborative care model. User involvement in decision process with regard to the treatment would also share the responsibility of outcomes on both the parties and would possibly stimulate quest for better evidence and evidence-based care.

A disconcerting finding in the present study was differences in the information provided from the care providers to the patient. Patients are likely to come into contact with different care providers as the shifts change and teams may not be updated completely about the progress in treatment or the decisions that have been made. Thus, there is a need to facilitate effective communication between the different care providers for the patient. The team approach is preferable whereby different professionals are updated about the present status and circumstances of the patient.

Implications and Future Directions

In order to achieve shared vision of better outcomes of patients with substance use disorders, good relationships and excellent communication are required with service providers, who in turn need to reflect on their communication methods. The recovery approach challenges current professional behaviors and advocates changing from being an expert to a coaching approach (23). Compassion and dignified care is central rents in mental health care as identified by Francis (24). The change processes need to be introduced gradually with sensitization of multiple stakeholders including the health-care providers.

Thus, educating the service users certainly has the potential to change some of the myths surrounding mental issues and to enable those responsible for delivering mental health services to gain an insight into what it is like to be on the receiving end of such services. Meaningful user involvement also requires organizations to examine their own cultural environment. Possible review and reconfiguration of existing professional structures, rather than expecting users to adapt to outmoded ways of working, is required. The approaches and values of individual practitioners are also crucial to the success of user involvement initiatives with good listening skills and valuing people key attributes (25). Above all, however, meaningful user involvement that makes a difference cannot be a one-off intervention a discrete program of work. It must be a part of the fabric of mental health services that affects every aspect of mental health provision.

Effective care is widely considered a collaborative process between all concerned stakeholders. The patient care communication and patient participation are part of a complex system which requires cooperation and respect between patients and caregivers. As such, this collaborative process should be built upon increased patient participation and dialogue in order to find common ground and understanding about the direction and goals of the care. There can be instances of marked discrepancy between the perceptions of patients and the physicians regarding the content of treatment information. Despite being stacked with information, patient still needed guidance and advice on how to follow the treatment plan. Overall, it seems that quality hospital care experience from the patients view is the one that supports the patient throughout the entire care continuum, both at the hospital and in the transition back to his or her home.

Future avenues of research include understanding the qualitative aspects of patient experience and how culture (and cultural variations) impacts such care. Studies may also look into how changes in institutional policies, training of health-care personnel, interventions to make treatment more collaborative, implementation of different inpatient care models, digital revolution, and advancement in the field of medical sciences impact the inpatient care experience for the patients.

Strengths and Limitations

This study conducted was the first of its kind which was undertaken in the Indian subcontinent. World over, the concept of patient experience with a continuous evaluation as a quality initiative is gaining momentum. Since mental health patients are among the most socially excluded within any society, understanding their concerns is important and is addressed to some extent by this study.

The limitations of the study include a single-center experience, which makes generalization to other setting difficult. Patient experiences were evaluated using a single instrument and in-depth follow-up exploration was not done. Possibility of bias favoring positive responses could not be fully eliminated though adequate privacy was ensured, and it was clarified that participation in the study would not change the treatment in any way and the responses were confidential. Possibility of Hawthorne effect exists as responses were gathered by the nursing staff.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study provides perspectives of the patients about the experiences during inpatient care during treatment of substance use disorders. Despite its constraints, the study brought forth both the favorable and not-so-favorable aspects of patient’s experience. Betterment of services would necessitate reflection on the deficiencies, especially with respect to shared decision-making, between communication between treatment providers and according due respect to the patients. Developing nations have the responsibility of not only expanding health-care infrastructure but also to embark upon building quality care where patient experience is valued and efforts are made to enhance the care process through responsive feedback.

Supplemental Material

Supplementary_table for Patient Involvement in Decision-Making: An Important Parameter for Better Patient Experience—An Observational Study (STROBE Compliant) by Namrata Makkar, Kanika Jain, Vijaydeep Siddharth and Siddharth Sarkar in Journal of Patient Experience

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants of the survey. The authors are obliged to all members of the staff who recruited patients for the project.

Author Biographies

Namrata Makkar is a medical graduate and Diplomate of National Board in Hospital Administration. She is currently working as a Deputy Medical Superintendent for a tertiary care hospital in New Delhi. Her area of interests includes public health and quality.

Kanika Jain is currently working as assistant professor of Hospital Administration at prestigious All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi. She is a medical graduate with Diplomate of National Board in Hospital Administration and Fellow of International Society for Quality In Healthcare (FISQua). Her area of interests icnludes emergency care and quality in healthcare.

Vijaydeep Siddharth is currently working as assistant professor of Hospital Administration at prestigious AIIMS, New Delhi. He has completed his Masters in Hospital Administration and is a Fellow of International Society for Quality In Healthcare (FISQua). He has won various awards including Best Post Graduate Resident in Health Administration. His area of interests include quality, patient safety, public procurement and cost analysis of healthcare services.

Siddharth Sarkar is an assistant professor at the National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre, AIIMS, New Delhi. He has been working in the field of addiction psychiatry and has presented nationally and internationally. He has won several awards including the Young Psychiatrist Award of the Indian Psychiatric Society. His research interests includes access to care and drop-out from treatment.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Gilburt H, Rose D, Slade M. The importance of relationships in mental health care: a qualitative study of service users’ experiences of psychiatric hospital admission in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:92 doi:10.1186/1472-6963-8-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anhang Price R, Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, Hays RD, Lehrman WG, Rybowski L, et al. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev. 2014;71:522–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bleich SN, Özaltin E, Murray CJ. How does satisfaction with the health-care system relate to patient experience? Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:271–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3 doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bee P, Brooks H, Fraser C, Lovell K. Professional perspectives on service user and carer involvement in mental health care planning: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1834–45. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mental Health Act 2007. Retrieved September 22, 2017, from: www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2007/12/contents.

- 7. National Health Service (NHS), England. Implementing the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health. NHS England; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Newman D, O’Reilly P, Lee SH, Kennedy C. Mental health service users’ experiences of mental health care: an integrative literature review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2015;22:171–82. doi:10.1111/jpm.12202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saraceno B, van Ommeren M, Batniji R, Cohen A, Gureje O, Mahoney J, et al. Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Lond Engl. 2007;370:1164–74. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61263-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kala A. Time to face new realities; mental health care bill-2013. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jones A, Crossley D. In the mind of another shame and acute psychiatric inpatient care: an exploratory study. A report on phase one: service users. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15:749–57. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S. The picker patient experience questionnaire: development and validation using data from in-patient surveys in five countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002:14:353–8. 10.1093/intqhc/14.5.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taylor TL, Hawton K, Fortune S, Kapur N. Attitudes towards clinical services among people who self-harm: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2009;194:10410 doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.046425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nebhinani N, Sarkar S, Gupta S, Mattoo SK, Basu D. Demographic and clinical profile of substance abusing women seeking treatment at a de-addiction center in north India. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22:12–16. doi:10.4103/0972-6748.123587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sarkar S, Balhara YPS, Gautam N, Singh J. A retrospective chart review of treatment completers versus noncompleters among in-patients at a tertiary care drug dependence treatment centre in India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38:296–301. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.185943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, et al. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gallagher A, Arber A, Chaplin R, Quirk A. Service users’ experience of receiving bad news about their mental health. J Ment Health Abingdon Engl. 2010;19:34–42. doi:10.3109/09638230903469137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hopkins JE, Loeb SJ, Fick DM. Beyond satisfaction, what service users expect of inpatient mental health care: a literature review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2009;16:927–37. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Storm M, Davidson L. Inpatients’ and providers’ experiences with user involvement in inpatient care. Psychiatry. 2010;81:111–25. doi:10.1007/s11126-009-9122-6. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mgutshini T. Risk factors for psychiatric re-hospitalization: an exploration. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2010;19:257–67. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matthias MS, Fukui S, Salyers MP. What factors are associated with consumer initiation of shared decision making in mental health visits? Adm Policy Ment Health. 2017;44:133–40. doi:10.1007/s10488-015-0688-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mobeireek AF, Al-Kassimi F, Al-Zahrani K, Al-Shimemeri A, al-Damegh S, Al-Amoudi O, et al. Information disclosure and decision-making: the Middle East versus the Far East and the West. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:225–9. doi:10.1136/jme.2006.019638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Slade M. Personal Recovery and Mental Illness: A Guide for Mental Health Professionals. Cambridge: University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. London: The Stationary Office; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Breeze JA, Repper J. Struggling for control: the care experiences of “difficult” patients in mental health services. J Adv Nurs. 1998;28:1301–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary_table for Patient Involvement in Decision-Making: An Important Parameter for Better Patient Experience—An Observational Study (STROBE Compliant) by Namrata Makkar, Kanika Jain, Vijaydeep Siddharth and Siddharth Sarkar in Journal of Patient Experience