Abstract

Helena Legido-Quigley and colleagues examine the barriers that migrants face in accessing healthcare and argue they are counterproductive for host countries

The decision to migrate is rarely easy. For many, there is little choice because of conflict or natural disaster, and their journeys may take months or years. Finding healthcare while in transit can be extremely challenging, and migrants may be denied care once settled. Although many migrants prosper in their new homes, for others the physical and psychological traumas can be lifelong.1

The number of migrants continues to grow2 with an estimated 1000 million in the world, including 258 million international migrants.3 Of the latter, an estimated 65 million have been forcibly displaced. Nearly 26 million are refugees and asylum seekers, the highest number since the second world war.

In 2017, most migrants moving to a different country moved to countries in Asia (80 million) or Europe (78 million).3 For those with valued skills, international migration can be relatively straightforward.4 For others, and especially those lacking documentation, the challenges can be severe. Some refugees and asylum seekers may struggle to provide the necessary evidence to claim their rights enshrined in national law and international treaties.

Although the world’s governments have committed to achieving universal health coverage,5 we argue that this can be done only by including all migrants. This can be achieved where the political will exists.

Everyone has a right to health

In 2015, world leaders restated their commitment to the right to health. They included a commitment to universal health coverage in the sustainable development goals. Universal health coverage is a guarantee that all people and communities can access high quality health services, while ensuring that they are not exposed to financial hardship.6

Health coverage cannot be described as universal if it excludes migrants, but many countries do so. This is particularly true for undocumented migrants. In some countries the situation is getting worse with migrants being openly targeted.

Since 2010 the British government has established a “hostile environment” for migrants. It introduced a series of measures to make access to public services more difficult. The National Health Service was directed to enforce immigration controls. These included a requirement to inform immigration authorities of people suspected of being in the country illegally. This measure is now being withdrawn after widespread outrage.7

In the USA, a zero tolerance migration policy was instigated in April 2018. People entering the country illegally had their accompanying children removed and detained, sometimes in steel cages. United Nations experts have suggested that this policy may amount to torture.8 Measures being implemented by the Trump administration on the US-Mexico border have been linked to the deaths of young children, with allegations of a lack of adequate care.9

The case for extending the protection of the health system to all migrants is clear, but there are challenges to overcome.

Overcoming health systems barriers

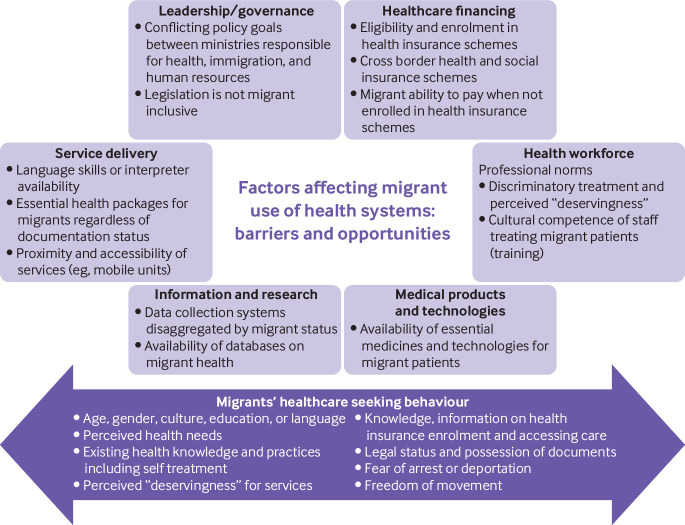

In figure 1 we depict the main barriers that prevent migrants from using health systems based on the World Health Organization’s health system building blocks.

Fig 1.

Factors contributing to barriers that prevent migrants from using health systems

One set of challenges relates to overall governance. Policies related to migrants often take place in silos, such as security, immigration enforcement, education, housing, and others. The health sector is often excluded or marginal, leading to policy incoherence.10

Many of the barriers faced by migrants arise from financing systems—in particular, eligibility and out-of-pocket payments. Enrolment in health insurance schemes often depends on citizenship or legal immigration status. Undocumented migrants are almost always excluded. Notable exceptions are Thailand and Spain.

Uninsured migrants, in particular, face barriers as few can afford payments.11 Transferability of social insurance schemes has been suggested to facilitate labour mobility.12 The free movement of labour was the initial reason for implementing cross border care within the European Union.13 It has subsequently developed into a comprehensive system giving those entitled to healthcare in one European Union member state the right to obtain it in others (subject to certain conditions). In other parts of the world, governments have been reluctant to adopt such models, as they often face challenges in ensuring financial protection for their own populations.12 A further complication is the large cost differences between many countries of origin and destination countries.

Migrants may also face obstacles arising from lack of cultural awareness by those providing care or due to language barriers, even though there is now considerable experience on how to overcome these challenges.14 There are fewer barriers related to medical products and, at least in theory, this could include medicines for certain imported diseases. Information systems are important for monitoring the health of migrants and their access to care, but strong safeguards are needed.

Policies should build on evidence of the behaviour of migrants seeking healthcare and the consequences of poor health literacy, unawareness of rights, and language and cultural differences. Migrants may avoid seeking care for fear of arrest or deportation, or they may believe that they are “undeserving.”15 Discrimination and extortion by authorities, such as police or immigration officials, adds to migrants’ stress and discourages them from seeking care.16

Several tools have been developed for assessing the inclusion and integration of migrants in health systems. One of the best known examples is the Migrant Integration Policy Index, covering 38 European countries. The health module includes entitlements to health services; accessibility of health services for migrants; responsiveness to migrants’ needs; and measures to achieve change.17 Other examples are the Health Information Assessment Tool for asylum seekers, used in Germany and the Netherlands,18 and the Health Equity Impact Assessment Tool, for newcomers to Canada.

In summary, many migrants, especially those who are undocumented, lack entitlement to healthcare, including mental health services. Even when they have a legal right, many barriers may prevent them from realising it.

Arguments for inclusion

The main argument advanced for restricting access to healthcare by migrants is the cost. This is not supported by research, however, which shows that providing healthcare for migrants has direct and indirect economic advantages for host countries and is beneficial for public health and social cohesion. For example, in Germany, policy changes created a natural experiment between 1994 and 2013. It was found that restricting the access of asylum seekers and refugees to healthcare resulted in higher costs in the long term.19 Furthermore, a study in several European countries found that extending access to primary care achieved large savings in direct medical and non-medical costs.20 Both studies concluded that inclusion of migrants in health systems reduced the risk of health conditions—which could be treated cheaply—progressing to complex and expensive illnesses.

The historical argument for extending care to migrants is based on public health considerations. Migrants rarely bring infections that pose a threat to the host population,21 22 but denying them treatment may create risks.21 22 A German study compared the costs of containing a measles outbreak in an asylum seekers’ shelter with the costs of hypothetical mass vaccination. It found that if the asylum seekers had been offered measles vaccination on arrival, 50% of the costs of managing the subsequent outbreak would have been saved owing to a reduced need for serological testing.23 In Malaysia, adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in refugees and host populations was compared. It was concluded that, if refugees were included in mainstream services, the high adherence rates achieved (equal to those in the host population) reduced onward transmission.24

A second argument derives from the growing recognition that migrants contribute to the economies of destination countries.25 This is important as many industrialised countries have declining birth rates and need continuing migration. On average, 17% of doctors and 6% of nurses in Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development countries have been trained abroad.26 Their contribution to the workforce and, thus, to the economy, depends on them being in good health, thereby justifying inclusive health policies.27

A final argument for inclusive policies is their contribution to social integration and cohesion. Some politicians complain about migrants’ lack of integration, forgetting that this should be a two way process.28 Policies strengthening inclusion in employment, education, housing, and health are well recognised as key to promoting social integration.29 The health system can have an important role in this process, creating culturally aware, migrant friendly services.29

In summary, migrant inclusive health systems reduce long term health expenditure, help to tackle shortages of workers, especially in the health and social care sectors, boost economic growth, and promote social integration in host countries.

Overcoming arguments against migration

Some countries are becoming more inclusive. For example, several Latin American countries, including Costa Rica and Argentina, have adopted specific initiatives on migrants’ access to health services using a human rights framework.30 31 Sri Lanka has implemented specialist health and welfare services for those returning migrant workers who have been subjected to abuse.7 32

Positive examples from Thailand (box 1) and Spain (box 2) highlight why a legal entitlement to healthcare is not, on its own, enough. It is necessary also to design health services that actively promote inclusion. Key factors underpinning the extension of health coverage to undocumented migrants in Thailand and Spain included explicitly stated political commitments. These were backed up by pressure from civil society, medical professional bodies, and the media.

Box 1. Thailand’s migrant insurance scheme.

Thailand, with its rapidly growing economy, has attracted many migrants from neighbouring countries—particularly, Cambodia, Lao People's Democratic Republic, and Myanmar.33 34 Thailand is celebrated for its achievement of universal health coverage at relatively low cost,35 which includes all ‘Thai nationals’ and registered migrants working in the formal sector. However, it has been more challenging to extend coverage to those with a precarious immigration status, especially undocumented migrants. In 2004 the government instigated and expanded a contributory insurance scheme for migrants from the three neighbouring countries. Managed by the Ministry of Public Health, it provided a broad benefit package without payment at point of care, although with some exclusions, such as renal replacement therapy.36 Migrants must undergo health screening and pay an annual premium of about US$ 70 (£55; €62) for each adult.37 Since 2014 this scheme has become part of the comprehensive registration measure, the so-called “one stop service”, which intends to “legalise” the undocumented status of migrants through nationality verification. The scheme is not without problems; although the government has stated clearly that failure to register leaves migrants at risk of deportation, only about 1.1 million have been enrolled, about one third of the expected total. Some providers have refused to enrol migrants as they perceived that many had pre-existing illnesses that threatened the viability of providers. A lack of legal clarity about the division of responsibility between migrants and their employers has also caused problems.36 38 39

Box 2. Free access to healthcare in Spain.

The 1986 General Health Law and the ensuing 2011 Public Health Law, granted all Spanish residents an explicit right to free healthcare. However, in 2012, in the wake of the financial crisis, the government sharply curtailed this right, using a Royal Decree. This allowed it to bypass the Cortes (parliament) and restrict access by migrants. This change limited access by undocumented migrants to emergency services only, unless they were children or pregnant women. In practice, the introduction of bureaucratic barriers and the fear of deportation made even emergency care difficult to obtain. The policy has been linked to an observed 15% increase in mortality among the migrant population in the 3 years after implementation of the decree.40

Subnational authorities and civil society acted to mitigate the effects of the new policy. Spanish regions have considerable autonomy in delivery of healthcare and some refused to comply with the national legislation, instead continuing to provide free services. In some regions, health professionals refused to comply with the new policy, citing their ethical duty.41 In July 2018, after the resignation of Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, the government signed a new Royal Decree granting undocumented migrants the right to health protection and healthcare under the same conditions as people with Spanish nationality, although barriers to successful implementation still need to be overcome.42

Recommendations and areas for further research

Although migration is high on the international policy agenda, there is scant research to inform policy. Research on migration and health is concentrated in high income countries that have been relatively unaffected by the large migration flows among countries in the global south.43 Migrants in different areas will have particular health needs, owing to previous experiences in their countries of origin and the journeys they have taken.44 To a greater extent than in other health research, it is necessary to take account of these differences. Migrants will differ in their willingness to become involved with researchers, reflecting their experiences, which may have affected their trust in others. Interventions should relate to the particular barriers to healthcare faced by migrants. These include health beliefs and cultural norms, such as gender roles, as well as legal, financial, and regulatory aspects of the health system.

We believe policy should be based on certain core principles. The first is the right to health, enshrined in various national and international laws and conventions.45 It is given added force in the sustainable development goals with their commitment to achieve universal health coverage. A health system that excludes groups such as migrants cannot be described as universal. The second is economic. The evidence that migrants make a net contribution to economic growth is compelling. So too is the evidence that providing timely care for migrants saves money in the long term. The third relates to social cohesion. Greater contact with migrants can often reduce hostility,46 47 with benefits for everyone. Inclusive health systems can play a role in this process.

Finally, there are implications for practice. Migrants, in particular undocumented migrants, should never have to fear that by accessing healthcare they risk detention or deportation. A policy which required the UK’s National Health Service to share data with immigration authorities has been abandoned but should never have been introduced.48 Health facilities should be places where everyone feels safe. There are several examples of health professionals taking responsibility to ensure that health facilities are safe spaces for migrants, such as the sanctuary hospitals in the USA or the Docs Not Cops movement in the UK.49 However, it is important to recognise that this may require civil disobedience or non-compliance with regulations in some countries.

Health professionals acting in good faith may be able to obtain protection in national law. We believe that greater clarity is needed also in international law. For example, in Europe, the European Court of Human Rights50 and the European Committee on Social Rights51 have explored some of the key questions on the rights of failed asylum seekers and migrants with irregular status, respectively. However, many issues remain unclear and selective strategic litigation may be needed to establish precedents.

We also contend that professional regulatory bodies have a duty to protect health workers against enforcement action by authorities. This again recognises the duty of health workers to their patients and their right to act according to their conscience. As far as we can see, professional bodies have largely remained silent about this subject in many countries.

Health systems in which no-one is left behind can be created, but it requires political will and concerted action by everyone.

Key messages.

Millions of men, women, and children who have migrated internationally pay taxes and contribute to local economies but fail to receive the security of universal health coverage

The right to health, which underpins the commitment to universal health coverage in the sustainable development goals, includes migrant populations

Some countries are designing inclusive policies to ensure that undocumented migrants have access to health services, while other countries are becoming more restrictive and eroding the principle of universality

Governments should expand and enhance health systems, where necessary, to incorporate the needs of undocumented migrants in national and local healthcare policies and plans and health professionals should do everything necessary to make this a reality

Contributors and sources: HLQ, KP, and MM conceived the paper. HL-Q and MM prepared the initial draft. HL-Q led the writing process. All authors contributed to the original content and revisions to the text. RS and LP contributed the case studies on Thailand and Spain. HL-Q has conducted a wide range of projects on migrant health in Europe and Asia focusing on their health needs and health systems responses to migrant health and wellbeing. NP has studied and reported on migration health, particularly the needs of trafficked people. STT has been working with refugees on community empowerment in Malaysia for more than 10 years. LP was the minister of health in Spain and under her leadership the Public Health Law was approved and access to healthcare was provided to some groups that had been excluded previously. RS has conducted a wide range of studies on health system response towards migrant health in Southeast Asia, particularly in Thailand. He was also involved in the expansion of national health insurance policy for stateless people in Thailand in 2015. KW has worked on a broad spectrum of migration health programmes globally, ranging from the Ebola outbreak response in West Africa to supporting member states with migration health interventions and research. MM has written extensively on healthcare for migrants to Europe and the legal basis of the right to health. KP has studied Latin American, Rwandan, Congolese, Somali, Nepali, and Syrian refugees, and has developed based migrant health guidelines for Canada, EU/EEA, and the Cochrane Collaboration.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of a series developed by The BMJ, the UN Migration Agency (IOM), and the Migration Health and Development Research Network (MHADRI). The article was commissioned by The BMJ, which retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication of these articles. Open access fees for the initial articles in the series were funded by IOM and Bruyère Research Institute.

References

- 1. Kirmayer LJ, Narasiah L, Munoz M, et al. Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health (CCIRH) Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: general approach in primary care. CMAJ 2011;183:E959-67. 10.1503/cmaj.090292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IOM. IOM DG swing calls for greater assistance, protection for the internally displaced. Geneva: IOM, 2018. https://www.iom.int/news/iom-dg-swing-calls-greater-assistance-protection-internally-displaced.

- 3. United Nations International migration report 2017: highlights. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2017. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2017_Highlights.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mladovsky P, Rechel B, Ingleby D, McKee M. Responding to diversity: an exploratory study of migrant health policies in Europe. Health Policy 2012;105:1-9. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim SS, Allen K, Bhutta ZA et alGBD 2015 SDG Collaborators Measuring the health-related sustainable development goals in 188 countries: a baseline analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1813-50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31467-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. Tracking universal health coverage: 2017 global monitoring report. WHO, 2017. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/193371513169798347/2017-global-monitoring-report.pdf

- 7.Ministry of Health, IOM, WHO. Leaving no one behind: a call to action on migrant health. Colombo, 2017. http://www.searo.who.int/srilanka/pr_a_call_to_action_on_migrant_health.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Office of the High Commission for Human Rights. UN experts to US: “Release migrant children from detention and stop using them to deter irregular migration”. 2018. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23245&LangID=E.

- 9.Barajas J. A second migrant child died in U.S. custody this month. Here’s what we know: PBS, 2018. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/a-second-migrant-child-died-in-u-s-custody-this-month-heres-what-we-know.

- 10. Zimmerman C, Kiss L, Hossain M. Migration and health: a framework for 21st century policy-making. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001034. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Asanin J, Wilson K. “I spent nine years looking for a doctor”: exploring access to health care among immigrants in Mississauga, Ontario, Canada. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:1271-83. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Banzon EP. Rising migration demands ‘roaming’ health coverage. Asian Development Bank, 2017. https://www.brinknews.com/rising-migration-demands-roaming-health-coverage [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Union. Directive 2011/24/EU on the application of patients’ rights in cross-border healthcare. EU, 2011. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32011L0024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14. Mladovsky P, Ingleby D, McKee M, Rechel B. Good practices in migrant health: the European experience. Clin Med (Lond) 2012;12:248-52. 10.7861/clinmedicine.12-3-248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Willen SS. Migration, “illegality,” and health: mapping embodied vulnerability and debating health-related deservingness. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:805-11. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harrigan NM, Koh CY, Amirrudin A. Threat of deportation as proximal social determinant of mental health amongst migrant workers. J Immigr Minor Health 2017;19:511-22. 10.1007/s10903-016-0532-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ingleby D, Petrova-Benedict R, Huddleston T, et al. The MIPEX Health strand: a longitudinal, mixed-methods survey of policies on migrant health in 38 countries. Eur J Public Health 2018;29:458-62. 10.1093/eurpub/cky233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bozorgmehr K, Goosen S, Mohsenpour A, Kuehne A, Razum O, Kunst AE. How do countries’ health information systems perform in assessing asylum seekers’ health situation? Developing a health information assessment tool on asylum seekers (HIATUS) and piloting it in two European countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:E894. 10.3390/ijerph14080894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bozorgmehr K, Razum O. Effect of restricting access to health care on health expenditures among asylum-seekers and refugees: a quasi-experimental study in Germany, 1994-2013. PLoS One 2015;10:e0131483. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ursula T, Novak-Zezula S, Renner A-T, et al. Cost analysis of health care provision for irregular migrants and EU citizens without insurance Vienna, 2016. https://eea.iom.int/sites/default/files/publication/document/Cost_analysis_of_health_care_provision_for_irregular_migrants_and_EU_citizens_without_insurance.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21. Williams GA, Bacci S, Shadwick R, et al. Measles among migrants in the European Union and the European Economic Area. Scand J Public Health 2016;44:6-13. 10.1177/1403494815610182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Odone A, Tillmann T, Sandgren A, et al. Tuberculosis among migrant populations in the European Union and the European Economic Area. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:506-12. 10.1093/eurpub/cku208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Takla A, Barth A, Siedler A, Stöcker P, Wichmann O, Deleré Y. Measles outbreak in an asylum-seekers’ shelter in Germany: comparison of the implemented with a hypothetical containment strategy. Epidemiol Infect 2012;140:1589-98. 10.1017/S0950268811002597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mendelsohn JB, Schilperoord M, Spiegel P, et al. Is forced migration a barrier to treatment success? Similar HIV treatment outcomes among refugees and a surrounding host community in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. AIDS Behav 2014;18:323-34. 10.1007/s10461-013-0494-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Noja GG, Cristea SM, Yüksel A, et al. Migrants’ role in enhancing the economic development of host countries: empirical evidence from Europe. Sustainability 2018;10:894 10.3390/su10030894 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. OECD Health Workforce Policies in OECD Countries: Right Jobs, Right Skills, Right Places. In: OECD , ed. OECD Health Policy Studies, 2016. https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Health-workforce-policies-in-oecd-countries-Policy-brief.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bloom D, Canning D. Health as human capital and its impact on economic performance. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance 2003;28:304-15 10.1111/1468-0440.00225 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Commission of the European Communities . 2000. Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on a community immigration policy.http://aei.pitt.edu/38186/1/COM_(2000)_757.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rudiger A, Spencer S. Social integration of migrants and ethnic minorities: policies to combat discrimination. The European Commission and the OECD, 2003. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260781134_Social_Integration_of_Migrants_and_Ethnic_Minorities_Policies_to_Combat_Discrimination [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cortes R. Human rights of migrants and their families in Argentina as evidence for development of human rights indicators: a case study. KNOMAD, 2017.. https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2017-04/KNOMAD%20WP%2022%20Migrant%20Rights%20in%20Argentina.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31. Noy S, Voorend K. Social rights and migrant realities: migration policy reform and migrants’ access to health care in Costa Rica, Argentina, and Chile. J Int Migr Integr 2016;17:605-29. 10.1007/s12134-015-0416-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wickramage K, De Silva M, Peiris S. Patterns of abuse amongst Sri Lankan women returning home after working as domestic maids in the Middle East: An exploratory study of medico-legal referrals. J Forensic Leg Med 2017;45:1-6. 10.1016/j.jflm.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kantayaporn T, Sinhkul N, Ditthawongsa N, et al. Estimation of transnational population for developing maternal and child health in Bangkok. HISRO: Nonthaburi, 2013. http://kb.hsri.or.th/dspace/handle/11228/3932?locale-attribute=th

- 34.Office of Foreign Workers Administration. Statistics of cross-border migrants with work permit in Thailand as of May 2015 (figure 13). Department of Employment, 2015. https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/3817560/1/2017_PHP_PhD_Suphanchaimat_R.pdf

- 35. Balabanova D, Mills A, Conteh L, et al. Good health at low cost 25 years on: lessons for the future of health systems strengthening. Lancet 2013;381:2118-33. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62000-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tangcharoensathien V, Thwin AA, Patcharanarumol W. Implementing health insurance for migrants, Thailand. Bull World Health Organ 2017;95:146-51. 10.2471/BLT.16.179606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Prasitsiriphol O, Sakulpanich T, Nipaporn S, et al. Review of the health insurance premium for migrant populations who are not covered by the social health insurance (according to the Cabinet Resolution on 15 January 2013) Nonthaburi. Health Insurance System Research Office, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Suphanchaimat R, Putthasri W, Prakongsai P, Tangcharoensathien V. Evolution and complexity of government policies to protect the health of undocumented/illegal migrants in Thailand - the unsolved challenges. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2017;10:49-62. 10.2147/RMHP.S130442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Suphanchaimat R, Wisaijohn T, Seneerattanaprayul P, et al. Evaluation on system management and service burdens on health facilities under the Health Insurance for People with Citizenship Problems. International Health Policy Programme, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mestres AJ, Casasnovas GL, Castello JV. The deadly effects of losing health insurance. UPF-CRES, 2018. https://ep00.epimg.net/descargables/2018/04/13/617bc3f9263d9a0dbcf3704f8d75a095.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 41. Legido-Quigley H, Otero L, la Parra D, Alvarez-Dardet C, Martin-Moreno JM, McKee M. Will austerity cuts dismantle the Spanish healthcare system? BMJ 2013;346:f2363. 10.1136/bmj.f2363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Legido-Quigley H, Pajin L, Fanjul G, Urdaneta E, McKee M. Spain shows that a humane response to migrant health is possible in Europe. Lancet Public Health 2018;3:e358. 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30133-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sweileh WM, Wickramage K, Pottie K, et al. Bibliometric analysis of global migration health research in peer-reviewed literature (2000-2016). BMC Public Health 2018;18:777. 10.1186/s12889-018-5689-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Odone A, McKee C, McKee M. The impact of migration on cardiovascular diseases. Int J Cardiol 2018;254:356-61. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.11.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Forman L, Beiersmann C, Brolan CE, Mckee M, Hammonds R, Ooms G. What do core obligations under the right to health bring to universal health coverage?. Health Hum Rights 2016;18:23-34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dovidio JF, Love A, Schellhaas FMH, et al. Reducing intergroup bias through intergroup contact: twenty years of progress and future directions. Group Process Intergroup Relat 2017;20:606-20. 10.1177/1368430217712052 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McKee R. Love thy neighbour? Exploring prejudice against ethnic minority groups in a divided society: the case of Northern Ireland. J Ethn Migr Stud 2016;42:777-96. 10.1080/1369183X.2015.1081055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hiam L, Steele S, McKee M. Creating a ‘hostile environment for migrants’: the British government’s use of health service data to restrict immigration is a very bad idea. Health Econ Policy Law 2018;13:107-17. 10.1017/S1744133117000251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Docs Not Cops 2018. http://www.docsnotcops.co.uk/.

- 50.European Court of Human Rights. Gadaa Ibrahim Hunde v the Netherlands. Case 17931/16. Strasbourg, 2016. https://www.inlia.nl/storage/files/5b0ff84dcd55a_ehrm-uitspraak-17931-16-bbb-28-juli-2016-hunde-v-the-netherlands-eng-18-pags-pdf.pdf

- 51.European Committee on Social Rights. European Federation of National Organisations working with the Homeless (FEANTSA) v. the Netherlands (complaint No. 86/2012). Brussels, 2012. https://www.refworld.org/cases,COEECSR,54e353f24.html [Google Scholar]