Abstract

Two cases of surgical fenestration combined with omentalization for canine renal cysts using laparotomy and laparoscopy are described. After surgery, the cystic lesions gradually diminished in size, and a complete regression was confirmed in Case 2 by ultrasonography. The dogs maintained good condition without clinical signs of renal compromise for 14 months (Case 1) and 24 months (Case 2). Omentalization is a simple and effective procedure for canine renal cysts that conserves the remaining parenchyma and can be performed by a laparoscopic approach.

Résumé

Fenestration chirurgicale combinée à une omentalisation pour le traitement de kystes rénaux chez deux chiens. Deux cas de fenestration chirurgicale combinée à une omentalisation pour traiter des kystes rénaux canins utilisant la laparotomie et la laparoscopie sont décrits. Après la chirurgie, les lésions kystiques ont graduellement diminué en grosseur, et une régression complète fut confirmée par échographie dans le Cas 2. Les chiens ont maintenu une bonne condition sans signe clinique de complication rénale pendant 14 mois (Cas 1) et 24 mois (Cas 2). L’omentalisation est une procédure simple et efficace pour les kystes rénaux canins qui conserve le parenchyme restant et peut être réalisée par une approche laparoscopique.

(Traduit par Dr Serge Messier)

Renal cysts (RCs) are fluid-filled, epithelial-lined, benign cystic structures within the renal cortex or medulla (1,2). Renal cysts are common in humans, and a retrospective study of simple RCs in healthy individuals reported that there was an overall prevalence of 10.7% and that 35.3% of these occurred in humans who were 70 years and older (3–5). Although the etiology remains unknown, tubular obstruction and ischemia in obstructed areas have been suggested (3). Renal cysts may originate from diverticulae of the distal convoluted renal tubules or collecting tubules (6). Metabolically active epithelial cells may cause an accumulation of fluid (7). Simple RCs are solitary cysts that induce no renal compromise; they are common in humans and dogs but not in cats (8,9) and are classified as Bosniak category 1 with the following characteristics in humans: thin smooth-walled lesions without features of malignancy, such as calcification, septation, or contrast enhancement observed by computed tomography (CT) (4,6,10).

Renal cysts in dogs and cats can be congenital, such as polycystic kidney disease (PKD) in Persian cats or bull terrier dogs, with an autosomal dominant trait; RCs can also be acquired, developing secondary to chronic nephropathies (9,11). Most RCs are benign and clinically silent, are found incidentally in healthy dogs, and generally require no treatment (8,11). Clinical signs, such as anorexia, depression, abdominal pain, or vomiting, are usually nonspecific and are caused by renal failure (11). Renal failure develops from cystic compression of the renal parenchymal vasculature (11). Renal ischemia can activate the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, resulting in hypertension (2,11,12). Although rare, cystic compression can result in distortion of the renal pelvis, hematuria, or obstructive uropathy, and cystic rupture into the abdomen or pelvicalyceal system is also possible in humans (12,13). A palpable mass is occasionally identified, and mechanical mass effects may result from the presence of large space-occupying cysts (3,4). In humans, pain is the most frequent complaint and indication for treatment. The pain is caused by distension of the innervated renal capsule, stimulating nociceptive fibers, and can present as behavioral changes in dogs (11).

Ultrasonographically, RCs are round or oval anechoic lesions with thin hyperechoic walls accompanying distal acoustic enhancement (6,8). Computed tomography indicates that RCs have radiodensities similar to water [–10 to 20 Hounsfield units (HU)], which is slightly lower in density than the adjacent renal cortex (6,13). Although there is no consensus on optimal timing for intervention, treatment indications include RCs with clinical signs and associated hypertension, infection, or urinary tract obstruction, RCs that are larger than 4 cm in diameter (in human medicine) (1,3), and RCs with a risk of malignancy (14). Treatment options include percutaneous aspiration, sclerotherapy to injure the cystic wall cells, cysto-retroperitoneal shunting, percutaneous fulguration and marsupialization, and surgical fenestration (deroofing and wide excision of the cystic wall) (3,4,6,12–14). Treatment goals include symptom relief and prevention of recurrence (12). This report describes 2 canine RCs treated by surgical fenestration and omentalization by laparotomy and laparoscopy.

Case descriptions

Case 1

An 11-year-old, 4.2 kg, intact female Yorkshire terrier dog was referred for multiple masses on the bilateral mammary chains, except the left first gland, which was suspected to be adenocarcinoma according to cytology. Preoperative thoracic radiography showed no specific findings. Ultrasonography and CT scanning, however, revealed diffuse hypoechoic nodules in the liver and a 36 × 40 × 46 mm anechoic hypodense cyst on the cranial pole of the right kidney without contrast enhancement (HU = 6.5), which was separated from the renal pelvis (Figures 1A, B). The patient had no clinical signs associated with these lesions, and laboratory examination results [complete blood (cell) count (CBC), chemistry, electrolytes, and urinalysis] were within the normal ranges except for a mild increase in total bilirubin [25.7 μmol/L, reference range (RR): 0 to 15.4 μmol/L]; blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was 5.7 mmol/L (RR: 2.5 to 5.7 mmol/L), creatinine was 79.6 μmol/L (RR: 44.2 to 159.1 μmol/L), urine specific gravity (USG) was 1.040. There was no proteinuria. Blood pressure (BP) was 120 mmHg.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic images of renal cysts in 2 dogs using computed tomography and ultrasonography.

In Case 1, a 36 × 40 × 46 mm round, anechoic, and hypodense cyst was identified in the right kidney, which was separated from the renal pelvis (A — CT; B — ultrasonography). A 30 × 36 mm round anechoic cyst was observed in Case 2 (C — ultrasonography).

At the time of the total mastectomy, an ovariohysterectomy and liver biopsy were also performed by a laparotomy. The laparotomy facilitated open fenestration combined with omentalization of the RC (Figure 2). When the RC was explored, a pale-colored intracapsular cyst was protruding from the right kidney, and transparent cyst fluid was aspirated and analyzed as a modified transudate, which was not urine (Table 1). The inner surface of the cavity was smooth when the cyst was opened. The thin wall of the cyst was sufficiently excised, with < 5 mm of marginal tissue adjacent to renal parenchyma remaining. Then, the omentum was fixed loosely with 2 horizontal mattress sutures (3-0 polyglyconate; Maxon, Covidien, Watford, UK).

Figure 2.

Open fenestration and omentalization of a canine renal cyst (RC) by laparotomy (Case 1).

An RC occupying the cranial pole in the right kidney (A), internal view of the opened cyst after aspiration (B), omentalized renal cyst after decortication (C).

* — kidney, O — omentum.

Table 1.

Cyst fluid analysis.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gross | Clear | Turbid, yellowish orange |

| Total protein (g/L) | 39 | 42 |

| TNCC | 200 | 11 700 Mainly renal epithelial cells and rare macrophages |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 53.0 | 53.0 |

| Specific gravity | 1.009 | 1.027 |

| Modified transudate | Exudate |

TNCC — total nucleated cell count (cells/μL).

The patient recovered uneventfully and was routinely managed for mastectomy [BP: 120 mmHg, BUN: 3.9 mmol/L, creatinine: 53.0 μmol/L on postoperative day (POD) 3]. A histopathological evaluation was not performed on the RC, but a diagnosis of mammary gland adenoma and hepatic lipogranuloma was made. Postoperative ultrasonography (Figures 3A, B) on POD 28 revealed that the omentum had maintained its position, and a 19.4 × 13.2 mm anechoic cyst was present at the omentalized site. The cyst had decreased to 16 × 14 mm on POD 56 and further decreased to 7 × 7 mm on POD 213. A follow-up by telephone was conducted by the referring veterinarian 14 mo after surgery, and the patient was reported to be in good condition without any complications or clinical signs.

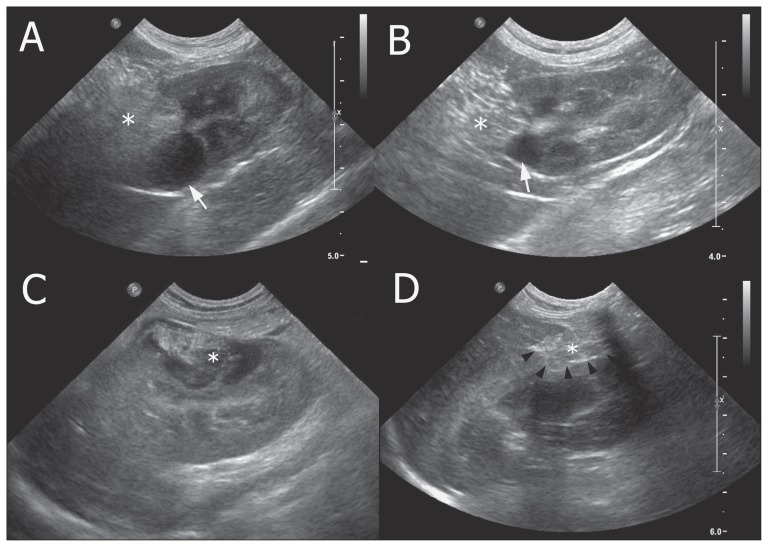

Figure 3.

Ultrasonographic images of renal cysts after surgical fenestration with omentalization in 2 dogs.

The omentum was maintained at its intended location, and the cyst regressed gradually in both patients. The lesion was 19.4 mm on post-operation day (POD) 28 (A) and 7 mm on POD 213 (B) in Case 1. In Case 2, complete regression was achieved (C — POD 1 and D — POD 156).

* — omentum; arrow — renal cyst; arrowhead — cystic wall line.

Case 2

A 14.5-year-old, 10.9 kg castrated male cocker spaniel dog was presented for surgical treatment of RC. The RC was first identified during a regular health screening 15 mo before the surgery. Ultrasonography revealed an anechoic cortical cyst (19.4 × 14.7 mm) separated by a hyperechoic septum at the caudal region of the right kidney. Although the owner complained that the dog had mild abdominal distension, there were no specific clinical signs or alterations in any of the blood examinations and urinalysis. With a tentative diagnosis of asymptomatic RC requiring no intervention, ultrasonographic monitoring was carried out because the patient had suffered from several concurrent diseases. These included mild mitral valve insufficiency (cardiac murmur grade 3), hind limb weakness associated with T12–13 intervertebral disc disease (IVDD), and lumbosacral stenosis, severe pruritus, and lichenification associated with bilateral externa otitis and hypothyroidism, bilateral keratitis/cataract, and left ocular lens luxation/glaucoma.

Eventually, the lesion developed into a large, anechoic cyst, growing up to 36 mm in diameter over the next 14 mo (Figure 1C); the cyst measured 22.6 × 18.2 mm, 28.9 × 22.5 mm, 30.8 × 28.4 mm, and 36.2 × 30 mm upon examination at 2, 9, 10, and 14 mo, respectively. The RC had expanded to the mid-kidney and was in the peripelvic area but was unrelated to the pelvis. Two new small cysts (6.4 × 3.9 mm and 1 × 1 mm) were then identified in the contralateral kidney. Urinalysis showed no proteinuria but microhematuria (> 5 cells per high-power field) and granular casts (> 2 per low-power field) were observed. The patient still showed no clinical signs, and all values of the laboratory data (CBC, chemistry, and electrolytes) were within the reference range except for mild leukocytosis (22 000 cells/μL, RR: 6000 to 17 000 cells/μL); BUN: 5 mmol/L, creatinine: 44.2 μmol/L, USG: 1.035. The BP was 140 mmHg. Nonetheless, it was decided to undertake surgery.

Two weeks later, a laparoscopic fenestration with omentalization was performed in dorsal recumbency through three 5-mm ports (Figure 4). A primary port was located using the Hasson technique, 2 cm caudal to the umbilicus. The right upper quadrant was explored with a 5 mm, 30° laparoscope (1188 HD camera; Stryker, Portage, Michigan, USA) under 11 mmHg of intra-abdominal pressure. A second port was placed 5 cm cranial to the primary, and a third port was placed in the right paramedial region, caudal to the kidney using finger indentation under laparoscopic visualization. The duodenum was retracted caudo-medially to visualize the RC on the mid-part of the right kidney. Protruding laterally from the kidney, the intracapsular RC was pale and tan-colored with less capsular vascularity than the surrounding unaffected renal parenchyma. A 22-G spinal needle was used to aspirate cystic fluid percutaneously, and the collapsed cyst was grasped and freed from the peritoneum by blunt dissection. The cyst wall was opened with a laparoscopic scissor, the area was suctioned completely with several yellow fragile debris, and the cyst wall was deroofed with an ultrasonic scalpel (Lotus ultrasonic scalpel; SRA Developments, Bremridge Ashburton, Devon, UK). The resected cyst wall, which was thin, tight, white, and pale, was retrieved by a trocar. The omentum that was placed within the right upper abdominal quadrant was packed inside the cystic pocket and sutured loosely to the trimmed edge with 2 continuous sutures (Vicryl, Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey, USA). After laparoscopic lavage and suction, the portal sites were closed routinely. The total surgery time was less than 1 h, and cytology revealed that the cystic fluid was not urine but exudate (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Laparoscopic fenestration and omentalization of a canine renal cyst (RC) (Case 2).

Intra-abdominal image of the RC (arrow) in the right kidney (A) and percutaneous aspiration using a spinal needle (B). The collapsed cyst (arrow) was circumferentially separated from the peritoneal lining with perinephric fat (arrowheads), and then the cyst wall was opened (C). The turbid orange-colored fluid was completely drained (D). Cyst wall tissue was removed using an ultrasonic scalpel (E), and the kidney returned to its normal bean-like shape (F). The omentum was packed into the cystic pocket (G) and sutured to the trimmed edge (H). Omentalized kidney (I).

The patient recovered well and showed good activity and appetite after surgery. However, high C-reactive protein (CRP, RR: 0 to 190.5 mmol/L) and leukocytosis (neutrophilia with a regenerative left shift) were present: 1504.8 mmol/L and 41 000 cells/μL on POD 1, and 1352.4 mmol/L and 59 000 cells/μL on POD 2, respectively. These values subsided with cefotaxime (Cefotaxime natrium inj.; Kukje pharm, Sungnam, Korea), 3.2 mg/kg body weight (BW), loading IV followed by 5 mg/kg BW per hour constant rate infusion (CRI), and enrofloxacin (Baytril; Bayer Korea, Seoul, Korea), 5 mg/kg BW, SC, q24h during the entire hospitalization period (4 d); the patient was discharged on POD 4. Postoperative histopathology of the resected cystic wall revealed numerous sites of hyalinization, which were interpreted as laser artifacts or hyalinized collagen, likely caused by compression of the cyst wall by the cyst fluid, and rarely small aggregates of desquamated epithelial cells were observed.

The omentum remained at the intended location (Figures 3C, 3D), and the lesion was 18 × 14 mm on POD 15 with hyperechogenicity, 21 × 17 mm on POD 45, 5 × 4 mm on POD 79, and it had disappeared after the next follow-up on POD 136. The 1-year examination showed no abnormality [BP: 140 mmHg, BUN: 4.5 mmol/L, creatinine: 44.2 μmol/L, symmetric dimethylarginine: 90 μg/L (RR: 0 to 140 μg/L), USG: 1.035], with no proteinuria and no urinary casts, and the patient was in good condition 24 mo after surgery without any clinical signs or renal compromise.

Discussion

While there is an abundance of information regarding RCs in humans, information regarding the incidence, treatment, or prognosis of RCs, except for PKD, is scarce in dogs. In this report, both RCs were intracapsular, extending from the parenchyma and distorting the renal contour. At the time of diagnosis, the patients had no clinical signs, such as abdominal pain or hypertension. Nonetheless, surgery was elected despite the age of the patients and their concurrent diseases.

Percutaneous aspiration or sclerotherapy under ultrasonography, fluoroscopy, or CT guidance are alternative, simple, and noninvasive techniques (2–4,8,10,11), but in the present cases, these techniques were not considered because of their recurrence rates and their requirement for general anesthesia. The success rate of percutaneous management is variable according to cyst size, sclerosing agent, single or multiple sessions, definition of success, or duration of follow-up (10). Previous studies involving sclerotherapy with 95% ethanol in 6 dogs and 4 cats reported a 100% success rate upon reexamination at 20 d (1 dog) (2), 3 to 4 wk (4 dogs and 4 cats) (11), and 6 mo (1 dog) (8) after the procedure. However, a human study that investigated 51 laparoscopic RC surgeries reported that 15 patients (29.4%) had a previous history of cyst aspiration, and 6 of these also had sclerotherapy (11.8%) (14). With high recurrence rates (up to 95% for aspiration alone and 0% to 78% for sclerotherapy) (10,13), some researchers in human medicine have recommended that sclerotherapy be used only as an initial therapy in cases of a single, small, symptomatic cyst (10) or for patients with significant comorbidity; this procedure provides a diagnostic sample for fluid analysis and allows for monitoring for pain relief (4). Sclerotherapy can result in local pain or loss of renal function because of inadvertent leakage of the sclerosing agent outside of the cyst or into the pelvicalyceal system (12). Open fenestration may be invasive, but in Case 1, it was performed as an additional procedure during a preplanned laparotomy. The lesion was not malignant, but was not a normal structure. The laparotomy provided an opportunity to operate on the cyst greater than 4 cm, which is a criterion for intervention in human medicine. The procedure was performed in a timely manner, was straightforward, and did not result in any complications.

Human studies on simple RCs have reported that 74% of RCs remained unchanged in size, but the average size increase and rate of cystic enlargement for RCs that became enlarged were 1.4 to 2.8 mm and 3.2% to 5% per year, respectively (13,15). Renal cysts have also been shown to double their size over 10 y (6). In this report, the cyst in Case 2 became enlarged rapidly, and lesions developed in the contralateral kidney. The original lesion increased in size by 17 mm (89.5%) over 14 mo, which is a relatively steep growth rate compared to that in human studies. The lesion was accompanied by alterations in urinalysis; therefore, a surgical intervention with a minimally invasive approach was conducted. The growth rate in Case 1 was not evaluated because the lesion was treated immediately after diagnosis. Further investigation regarding the stability or growth rate of canine RCs is required to determine whether any similarities are shared with RCs found in human medicine.

Surgical deroofing can be performed for large recurrent RCs and has a high success rate (95% to 100%) in human patients (10). Evaluation of the communication between the cyst and the pelvicalyceal collection system should be performed before surgery, because a retroperitoneal urinoma or urinary ascites can potentially develop after decortication (4). Contrast medium studies with intravenous urography, retrograde ureteropyelography, direct instillation into the cyst after aspiration, contrast-enhanced CT, or fluoroscopic renal cystogram can be used (4,10,14). This was not performed in Case 2, but fortunately, the cystic fluid was not urine, and there was no communication with the renal pelvis. Not all investigators emphasize this procedure (8,11,14), but this could be a key to differentiating simple RC from communicating RC, calyceal diverticulum (human), or cystic neoplasm (10,13,16). Methylene blue can also be injected via the ureteric catheter for final inspection at the end of the procedure (14). Regarding decortication, an incomplete handling or insufficient excision of the cystic wall increases the recurrence rate; therefore, a surgical excision as wide as possible should be attempted. Additionally, omentum or perinephric fat can be interposed to prevent recurrence (4,14,17). Due to the physiological drainage of omentum, it has been used in the treatment of cystic diseases in various organs in veterinary medicine (18). The abundant meshwork of omental vasculature and lymphatics can absorb fluid and promote resolution of infection, and the omentum reduces dead space, provides increased blood flow, promotes angiogenesis and lymphatic drainage, adheres to the site of inflammation sealing off the diseased area, and enhances local immune function and wound healing (19).

Accordingly, in dogs and cats, omentalization has been performed for the treatment of cysts, pseudocysts and abscesses in the prostate, pancreas, liver, uterine stump, and sublumbar lymph nodes for chronic effusion in synovial cavities and for the treatment of chylothorax (18–21). Omentalization is a simple but effective treatment for lesions with concerns of high recurrence or in nonresectable lesions, while preserving not only the remaining normal parenchyma but also the adjacent vital structures (19,21). In Case 1, omentalization was performed after RC deroofing because the hilar side of the cystic wall was not removed so as to avoid damage to the renal parenchyma. The cyst did not regress immediately after surgery, but it decreased in size gradually, providing evidence that the omentum provides continuous physiological drainage of the RC. Case 1 did not develop any related clinical signs of renal compromise over the 14-month follow-up period, and based on that result, the rapidly progressing RC in Case 2 was treated with the same procedure (surgical fenestration and omentalization) by a minimally invasive approach.

The laparoscopic approach did not result in any intraoperative or postoperative complications. Compared to other parenchymal organs, kidneys are covered by a capsule of thick connective tissue and are therefore relatively firm. In Case 2, moreover, the cortical lesion was a clearly compartmentalized, solitary intracapsular cyst that was not associated with the renal pelvis. Additionally, the RC had no gross inflammation, adhesions to adjacent tissues, or cystic rupture, and there were no vital structures immediately adjacent to lesion at risk of injury, as in the case of prostatic or pancreatic cysts. These findings facilitated laparoscopic omentalization; as a result, the RC was not difficult to manipulate. There was minimal hemorrhage during suture-biting adjacent to the renal parenchyma that did not require intervention for hemostasis. Laparoscopic ligating clips could facilitate the ease and speed of the procedure. Because the cyst occupied the midzone of the right kidney and we needed to maneuver the lateral or dorsal convex side of the kidney away from the renal hilus, a right-side up position could have been more convenient. However, the procedure was achieved by means of medially rotated retraction of the dorsal edge of the cystic wall and tilting the surgical table after the cyst was released from the peritoneum, and there was no need for conversion. Although the excision of the cyst wall was not as extensive as in Case 1, the cystic lesion disappeared completely.

In human medicine, complications associated with RC include infection, hemorrhage, or rupture of the cyst, which occur in 2% to 4% of patients (6). The incidence of cyst infection in human PKD patients has been reported to be 8.4% (22), with E. coli being the most commonly found pathogen. Cystic fluid culture was not performed in either of the cases, and histopathology was inadvertently excluded in Case 1. It was difficult to evaluate the postoperative morbidity of fenestration and omentalization in Case 1 because these procedures were performed in conjunction with routine procedures, although the patient recovered favorably. Although Case 2 had an excellent postoperative condition (alertness, appetite, activity, and urination), the patient experienced an acute increase in CRP and leukocytes with left shift for the next 2 d. It could contribute to his comorbidities or surgical stress, but the possibility of cystic infection could also not be ruled out. During percutaneous aspiration, the cystic content escaped due to internal pressure (a Veress needle could have been useful). Although a direct smear of the exudate showed no bacteria or inflammatory cells, it cannot be definitively diagnosed as sterile because bacterial culture was not conducted. However, the lesion did not have a markedly thickened or calcified wall, which is often identified in infected RCs (6), and the patient successfully recovered without developing peritonitis. Hyperechogenicity in the cystic lesion observed on POD 15 did not result in an intervention because the omentalization had been performed, and the lesion resolved spontaneously.

Although the artifacts in Case 2 prevented histopathological interpretation including evidence of malignancy, CT examination is warranted if any change is noted in the shape of the RC wall and clinical signs during preoperative surveillance or conservative management (15) to determine whether there is progression associated with malignancy. Clinical signs are more common with neoplastic lesions than simple cysts (6). In a study of 61 human RC patients, there were 2 cases of neoplasms that originated from the cystic wall. These cases were identified in each patient 5 and 6 y after the initial diagnosis of a simple RC, which had either a small solid component or an irregularity of the wall (15). A risk of malignancy has been correlated with findings of calcification, septation, lobulation, wall thickening or irregularity, nodularity, and contrast enhancement by CT (6).

Since it was first described in 1992, laparoscopic intervention has become a standard for the treatment of symptomatic and simple RCs in human medicine (10,12,14). Laparoscopic intervention has a high success rate, a lower level of invasiveness than open surgery, and a low complication rate (13). Various approaches, including conventional transperitoneal, retroperitoneal, single site surgery, and natural orifice pathways, have been used (10,12,14). In a study by Erdem (12), laparoscopic decortication (n = 17) achieved a symptomatic success rate of 94.2% and a radiographic success rate of 100% during a follow-up period of 12.5 mo. Three patients experienced minor complications (subcutaneous CO2 leakage and self-regressed paralytic ileus). In another study of 51 laparoscopically treated patients, complications included gonadal vessel injury (n = 1), mild ileus (n = 2), low grade fever (n = 3), and perinephric hematoma (n = 1) (14). Those patients were 100% symptomfree, without urinary tract obstruction for 6 to 12 mo after surgery, but recurrence was observed through ultrasonography in 3 patients. In addition, Okeke et al (4) reported no postoperative complications in 7 patients, except for 1 episode of refractory hemorrhage, and a 100% success rate was observed 17.7 mo after surgery. In Case 2, transperitoneal laparoscopic fenestration followed by omentalization was performed because of the rapid accumulation of cystic fluid and changes in urinalysis. Based on previously reported results, a favorable prognosis is expected.

This report describes incidentally detected RCs in 2 dogs, and surgical fenestration and omentalization resulted in regression of the RCs. Omentalization was effective, and a laparoscopic approach was feasible in our systemically compromised patient. Further studies are warranted using a larger number of cases and long-term follow-up.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2017R1D1A1B03035022). CVJ

Footnotes

The authors report no financial or other conflicts of interest related to this report.

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Li H, Zhang L, Wang H, et al. Two-port retroperitoneal laparoscopic surgery for the treatment of simple renal cysts by a single person. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2017;10:8037–8042. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zatelli A, Bonfanti U, D’Ippolito P. Obstructive renal cyst in a dog: Ultrasonography-guided treatment using puncture aspiration and injection with 95% ethanol. J Vet Intern Med. 2005;19:252–254. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2005)19<252:orciad>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baysal T, Soylu A. Percutaneous treatment of simple renal cysts with n-butyl cyanoacrylate and iodized oil. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2009;15:148–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okeke A, Mitchelmore A, Keeley F, Timoney A. A comparison of aspiration and sclerotherapy with laparoscopic de-roofing in the management of symptomatic simple renal cysts. BJU Int. 2003;92:610–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang CC, Kuo JY, Chan WL, Chen KK, Chang LS. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of simple renal cyst. J Chin Med Assoc. 2007;70:486–491. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(08)70046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eknoyan G. A clinical view of simple and complex renal cysts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1874–1876. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008040441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murcia NS, Sweeney WE, Jr, Avner ED. New insights into the molecular pathophysiology of polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 1999;55:1187–1197. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agut A, Soler M, Laredo FG, Pallares FJ, Seva JI. Imaging diagnosisultrasound-guided ethanol sclerotherapy for a simple renal cyst. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2008;49:65–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2007.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck C, Lavelle R. Feline polycystic kidney disease in Persian and other cats: A prospective study using ultrasonography. Aust Vet J. 2001;79:181–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2001.tb14573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwal MM, Hemal AK. Surgical management of renal cystic disease. Curr Urol Rep. 2011;12:3–10. doi: 10.1007/s11934-010-0152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zatelli A, D’Ippolito P, Bonfanti U, Zini E. Ultrasound-assisted drainage and alcoholization of hepatic and renal cysts: 22 cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2007;43:112–116. doi: 10.5326/0430112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erdem MR, Tepeler A, Gunes M, et al. Laparoscopic decortication of hilar renal cysts using LigaSure. JSLS. 2014;18:301–307. doi: 10.4293/108680813X13753907291558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ali FM. Efficacy of laparoscopic retroperitoneal deroofing of simple renal cyst in comparison with open surgery. QMJ. 2014;10:192–200. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gadelmoula M, KurKar A, Shalaby MM. The laparoscopic management of symptomatic renal cysts: A single-centre experience. Arab J Urol. 2014;12:173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terada N, Arai Y, Kinukawa N, Terai A. The 10-year natural history of simple renal cysts. Urology. 2008;71:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dirim A, Hasirci E, Baskent YCA. Different treatment approaches after failure of laparascopic treatment of calyceal diverticulum confused with communicating-type renal cyst: Case report. Cent European J Urol. 2017;70:216–217. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2017.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell RT, Pinson CW. Surgical management of polycystic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5052–5059. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i38.5052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson MD, Mann F. Treatment for pancreatic abscesses via omentalization with abdominal closure versus open peritoneal drainage in dogs: 15 cases (1994–2004) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006;228:397–402. doi: 10.2460/javma.228.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell BG. Omentalization of a nonresectable uterine stump abscess in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;224:1799–1803. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.224.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stegen L, Van Goethem B, Beerden C, Grussendorf C, de Rooster H. Use of greater omentum in the surgical treatment of a synovial cyst in a cat. Tierarztl Prax Ausg K Kleintiere Heimtiere. 2015;43:115–119. doi: 10.15654/TPK-140382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bray JP, White RA, Williams JM. Partial resection and omentalization: A new technique for management of prostatic retention cysts in dogs. Vet Surg. 1997;26:202–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1997.tb01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sallée M, Rafat C, Zahar JR, et al. Cyst infections in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1183–1189. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01870309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]