Abstract

Collection of faecal samples for microbiome analysis in acutely sick patients is logistically difficult, particularly if immediate freezing is required (i.e. fresh-frozen, or FF sampling). Previous studies in healthy/non-hospitalized volunteers have shown that chemical stabilization (i.e. stabilized-frozen, or SF sampling) allows room-temperature storage with comparable results to FF samples. To test this in a hospital setting we compared FF and SF approaches across 17 patients undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) using both 16S rRNA gene and shotgun metagenomic sequencing. A paired (same stool specimen) comparison of FF and SF samples was made, with an overall comparable level in relative taxonomic abundances between the two sampling techniques. Though shotgun metagenomic sequencing found significant differences for certain bacterial genera (P < 0.001), these were considered minor methodological effects. Within-sample diversity of either method was not significantly different (Shannon diversity P16SrRNA = 0.68 and Pshotgun = 0.89) and we could not reject the null hypothesis that between-sample variation in FF and SF were equivalent (P16SrRNA = 0.98 and Pshotgun = 1.0). This indicates that SF samples can be used to reliably study the microbiome in acutely sick patient populations, thus creating and enabling further outcomes-based metagenomic studies on similarly valuable cohorts.

Subject terms: Metagenomics, Haematological cancer, Medical research

Introduction

It is becoming increasingly clear that analysis of the human gut microbiome can reveal critical aspects of human disease pathogenesis, as well as the variation of treatment responses among a variety of patient groups1–3. As a result, a growing number of hospitals are trying to establish clinical biobanks of stool samples for use in downstream research projects.

Currently, the considered “gold standard” for microbiome studies suggests that stool samples be collected and then undergo immediate DNA-extraction or at least immediate freezing at −20/−80 °C. However, it is very difficult to comply with these conditions in a hospital setting, where even refrigeration of samples is difficult due to limited resources, irregular sampling time-points or patient visits, as well as the need to prioritize patient care. Additionally, complete capture and follow-up of many patient populations would require at-home sampling of out-patients, adding further variability to the time between sampling and freezing. Therefore, the ideal sample collection method within hospitals would rather allow for samples to be kept at room temperature prior to freezing. This would enable at-home sample collection for out-patients, no need for urgent hospital carriers for sample delivery, and no requirement for same-day DNA-extraction.

Although chemical stabilization followed by a delayed time to freezing (stabilized-frozen freeze (stable-freeze, or SF) appears to be a good alternative to direct freezing (fresh-freeze, or FF) or fresh DNA-extraction (fresh-extract, or FE), all studies to date assessing its use are based on cohorts of non-hospitalized/healthy volunteers4–22. In particular, there is an open question as to the use of SF protocols when microbiomes are expected to have low diversity8. It is therefore currently uncertain whether or not results from previous method studies can be applied to samples collected in a hospital, where low diversity gut microbiomes are likely. Additionally, there have been little data evaluating the effect of SF methods using shotgun metagenomic sequencing4,7,14, which, unlike 16S rRNA gene sequencing data, provides detailed species level information. As bacterial species can differ in diseased populations, it is essential to collect this information and evaluate whether SF affects their compositions or not.

To address these remaining aspects of collection-associated bias within gut microbiomes of the diseased, we have conducted a study comparing FF samples to those collected using a SF protocol. This is the first study (to our knowledge) assessing the differences between these protocols using both 16S rRNA gene and shotgun metagenomic sequencing in a hospital setting. Our study was performed in a cohort of patients undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) at Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. Samples were delivered to the Centre of Excellence for Personalised Medicine for Infectious Complications in Immune Deficiency (PERSIMUNE)23 biobank, also located at Rigshospitalet. HSCT serves as a useful disease proxy as it is reserved for severely diseased patients and, critically, has been shown to heavily impact microbiome structure24.

Results

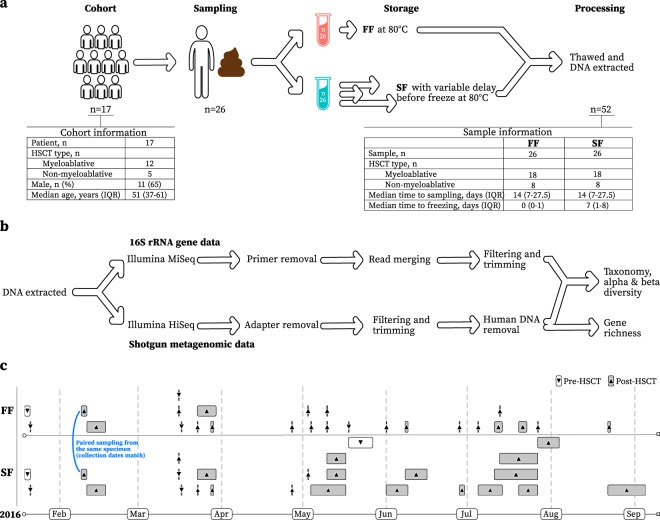

A total of 26 paired stool samples were generated from 17 haematology patients undergoing myeloablative or non-myeloablative HSCT. Each stool sample pair consisted of 1 FF sample (i.e. freshly frozen at time of sampling), and 1 SF sample (i.e. chemically stabilized prior to freezing after a variable period no greater than 16 days). An overview of the study design, summarized baseline patient and sample information, as well as time from sampling to freezing can be found in Fig. 1. Specific patient/sample numbers with time from HSCT to sampling and freezing can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 1.

(a) Overview of study design with general patient and sample information. FF = Fresh-frozen, SF = Stabilized-frozen. (b) Overview of the bioinformatic pipeline. (c) Overview of calendar time from sample collection to freezing for all FF (fresh-frozen) and SF (stabilized-frozen) samples. Arrows indicate if pre-HSCT or post-HSCT samples.

Data quality

To ensure that data from both sampling methods were acceptable for analysis, all samples underwent quality control steps as described in the methods section.

16S rRNA gene sequencing data

One sample was removed due to a severe lack of overlap between paired-ends (a fundamental requirement of our analysis pipeline). Another sample was lost due to low sequence content (<10,000 unfiltered reads). We observed a minor batch effect across sample runs that slightly biased mean quality and read numbers by affecting reverse-end sequences. However, our pipeline largely removed this bias by merging paired ends and filtering (see Methods). All filtered samples had mean quality scores of over 34 with >10,000 reads and batch effects did not influence which samples passed quality control steps. To summarize, high quality data was collected for 24 of the 26 stool samples.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing data

Seven samples were removed as their sequenced data did not contain sufficient information for further study, either due to poor quality, human contamination, or sequencing issues (threshold of 1 million reads). All samples had final mean quality scores of over 37 with > 3.5 million reads. To summarize, high quality data was collected for 21 of the 26 stool samples, resulting in a paired sample overlap of 76% (i.e. 76% of paired samples had both 16S rRNA gene and shotgun metagenomic sequencing data after quality control steps). The other 24% of samples had either 16S rRNA gene or shotgun metagenomic sequencing data available for analysis.

Alpha-diversity

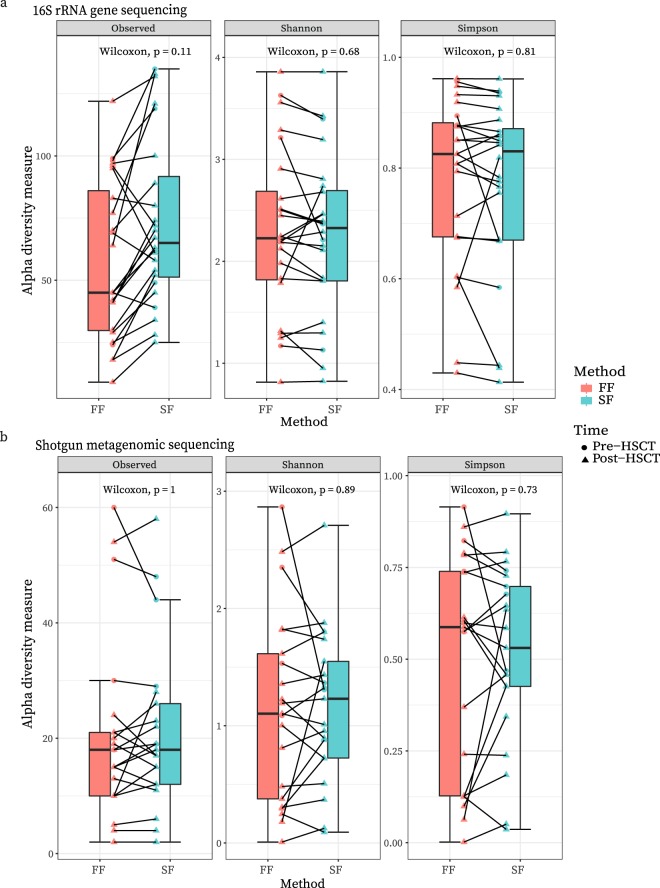

We next assessed possible differences between methods for within-sample diversity (i.e. alpha-diversity).

16S rRNA gene sequencing data

We found a general increase of observed genera in the SF versus FF samples. However, this was not significant (Wilcoxon paired test, P = 0.11) and other alpha diversity measures showed no differences (Fig. 2a). The mean Simpson index was 0.78 (IQR 0.68-0.88) vs 0.77 (IQR 0.67-0.87) in FF and SF samples respectively. Similarly, the mean Shannon indices were likewise comparable at 2.30 (IQR 1.82-2.69) vs 2.25 (IQR 1.80-2.69) in FF and SF samples respectively. Indeed, there was no statistically significant difference in either alpha diversity measure (Wilcoxon paired test, PSimpson = 0.81 and PShannon = 0.68).

Figure 2.

(a) Alpha diversity measures based on 16S rRNA gene data for each sampling method, with pairs connected by lines. Circle vs triangle shapes represent pre-HSCT vs post-HSCT samples respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between fresh-frozen (FF) and stabilized-frozen (SF) samples regarding the number of observed species, Shannon or Simpson indexes. (b) Alpha diversity measures based on shotgun metagenomic data for each sampling method, with pairs connected by lines. Circle vs triangle shapes represent pre-HSCT vs post-HSCT samples respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between fresh-frozen (FF) and stabilized-frozen (SF) samples regarding the number of observed species, Shannon or Simpson indexes. These figures have been created with help of the R(v3.5.0)29/PhyloSeq37 package.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing data

As with 16S rRNA gene sequencing, the mean Simpson and Shannon indices were similar between FF and SF samples at 0.50 (IQR 0.13-0.74) vs 0.51 (IQR 0.43-0.70) and 1.15 (IQR 0.38-1.61) vs 1.16 (IQR 0.72-1.55), respectively (Fig. 2b). As expected from the IQRs there was no significant difference in either diversity measure (Wilcoxon paired test, PSimpson = 0.73 and PShannon = 0.89).

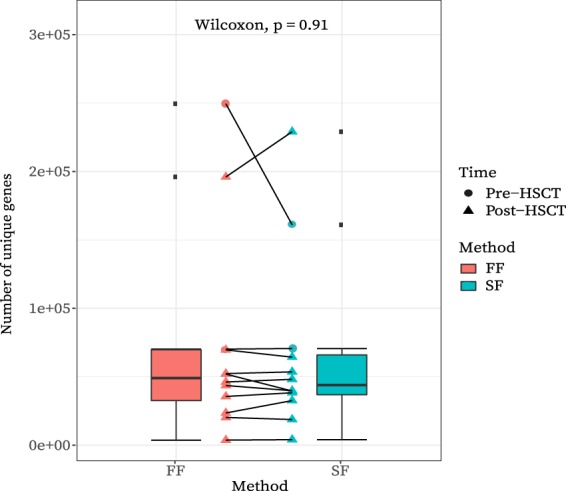

Shotgun metagenomics gene richness

As an additional measure to assess diversity we also examined gene richness (the number of unique genes) in the shotgun metagenomic sequencing data. This measure is used to divide samples into those of low versus high gene richness, with those of high gene richness generally considered to have higher diversity.

There was a median of 5,507,430 reads per sample mapping to the IGC (Integrated Gene Catalogue)25 (interquartile range (IQR) 4,460,836–6,047,576). Based on a rarefaction curve of mapped reads and the number of unique genes (Supplementary Fig. S1), samples with <5 million mapped reads were discarded for the gene richness analysis as their diversity was biased by sampling. The 12 remaining sample pairs had a median of 47,180 unique genes per sample (IQR 34,876–69,799). FF and SF samples had similar medians of 49,086 and 44,004, respectively (Fig. 3). There was no evidence of a statistically significant difference in gene richness between FF and SF samples (Wilcoxon paired test, P = 0.91). Two paired samples are notable for their unusually high gene richness (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Gene richness (i.e. the number of unique genes) for each sample per method and connected as sample pairs. Circle vs triangle shapes represent pre-HSCT vs post-HSCT samples respectively. Box plots show interquartile ranges (minimum and maximum values as whiskers) for gene richness per sampling method. A Wilcoxon paired test found no significant difference in the mean gene richness between fresh-frozen (FF) and stabilized-frozen (SF) samples. This figure has been created with help of the R(v3.5.0)29/PhyloSeq37 package.

Beta-diversity

We next assessed the beta-diversity, or between-sample diversity, looking for changes in variance between paired samples and testing whether potential differences were driven by sampling method.

16S rRNA gene sequencing data

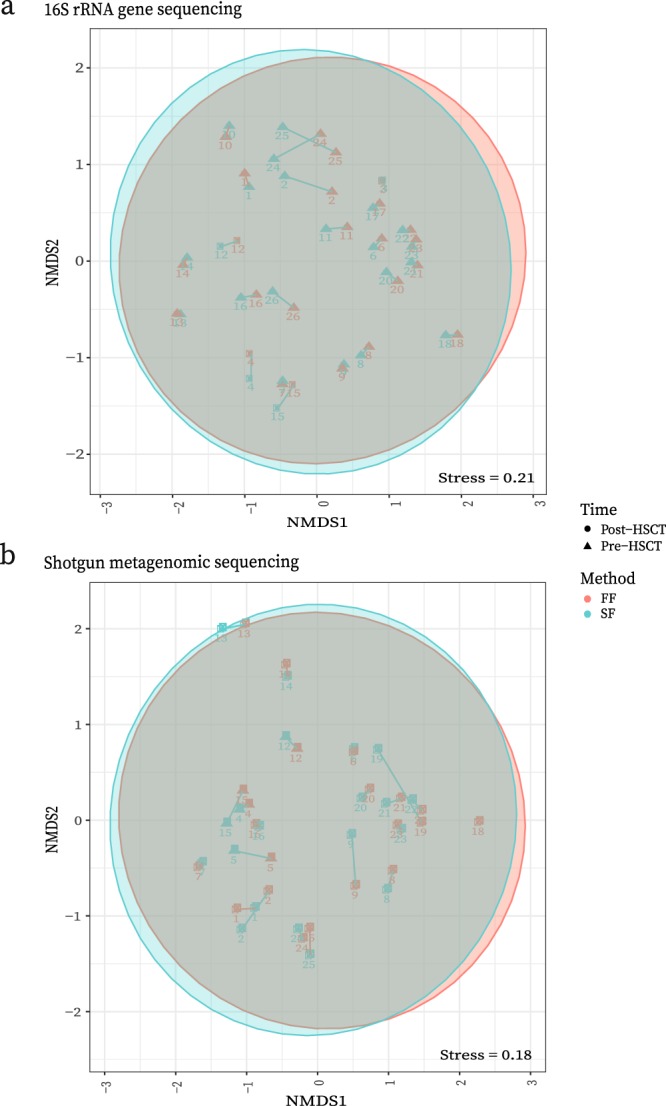

A non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot based on Bray-Curtis distances showed a strong overlap of sampling method types and clustering of sample pairs (Fig. 4a). An ADONIS test on the Bray-Curtis distances showed no evidence of differences between SF and FF samples (P = 1.00).

Figure 4.

(a) 16S rRNA gene sequencing data of beta diversity using Bray-Curtis distances to compare sampling methods represented in a NMDS plot. Sampling pairs are connected by lines with circle vs triangle shapes representing pre-HSCT vs post-HSCT samples respectively. FF = Fresh-frozen, SF = Stabilized-frozen. (b) Shotgun metagenomic sequencing data of beta diversity using Bray-Curtis distances to compare sampling methods represented in a NMDS plot. Sampling pairs are connected by lines with circle vs triangle shapes showing sampling time relative to HSCT. FF = Fresh-frozen, SF = Stabilized-frozen. These figures have been created with help of the R(v3.5.0)29/PhyloSeq37 package.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing data

As with the 16S rRNA gene sequencing data, the NMDS plot showed a strong overlap of sampling methods and clustering of sample pairs (Fig. 4b). The ADONIS again showed no evidence of differences between samples being based on sampling method (P = 0.67).

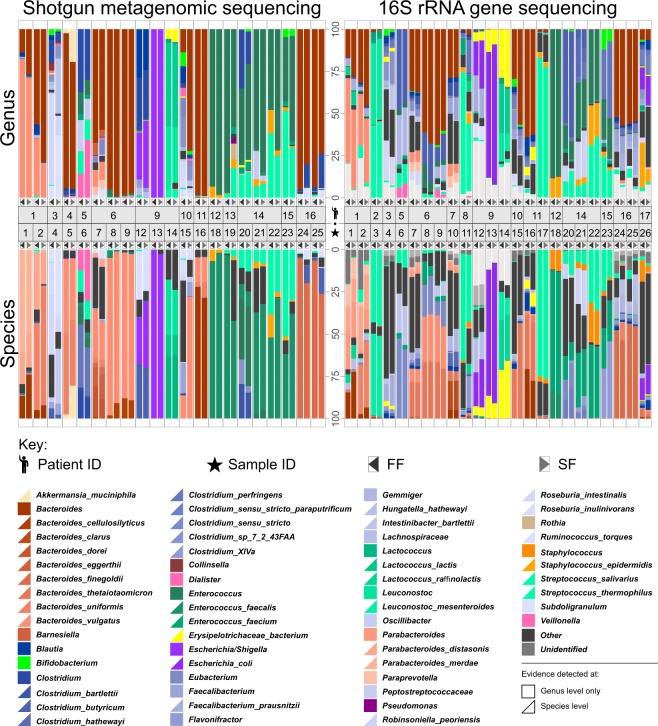

Taxonomy and relative abundance

To look more specifically at possible compositional differences, i.e. if certain bacteria were affected by sampling methods, we compared taxonomical differences between FF and SF samples by calculating the relative abundances of their genera.

16S rRNA gene sequencing data

Relative abundances of genera between FF and SF sample pairs appeared visually similar when examining bacteria present in the sample cohort (Fig. 5). This was verified statistically by paired DESeq2 analysis, which found no significant difference (α = 5%) in the relative abundances of all genera between FF and SF methods.

Figure 5.

Shotgun metagenomic and16S rRNA gene sequencing data identifying the bacterial genera and species found in the sample cohort and their relative abundances (in percent) present in each individual sample. “Other” are identified bacteria that are not in the top 30 found genera and species respectively across the cohort. “Unidentified” represent bacteria that are among the top 30 genera/species but are unidentifiable at that level. All top 30 bacterial species and genera are represented by a colour shown in the figure key. These colours are displayed as either a square or triangle: (square) evidence found at genus level, colours only map to genus panels; and (triangle) evidence found for species, colours map to both genus and species panels. There are more than 30 species/genera due to the different taxonomies used for 16S rRNA gene and shotgun metagenomic sequencing analysis. This figure has been created with help of the R(v3.5.0)29/PhyloSeq37 package. For specific values of all relative abundances used in this figure (i.e. the top 30 genera/species from all samples) please see Supplementary Table S2).

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing

As with the 16S rRNA gene sequencing data, relative abundances of genera were visually similar (Fig. 5) but the Wald test of paired DESeq2 highlighted statistically significant differences between FF and SF in the relative abundance of 7 genera (Actinomyces, Brevibacterium, Cryptobacterium, Propionibacteriaceae (unclassified), Propionibacterium, Ralstonia, Ruminococcus, P < 0.001 for all). These differences were, however, found in a maximum of 3/21 sample pairs per bacterial genus, with all but one sample pair having differences in abundancy of < 3% (Supplementary Fig. S2). This highlights the sensitivity and reproducibility of shotgun-based sequencing, but also demonstrates the lack of consistent or predictable change one would expect if driven by sampling methodology.

Discussion

In our study we show that SF is comparable to FF protocols in a diseased and hospitalized cohort using both 16S rRNA gene and shotgun metagenomic sequencing data. When comparing the alpha-diversity between sampling methods we found no significant difference between SF and FF samples. Differences between samples (based on Bray-Curtis distances) in our study were not driven by the different sampling methods. Both findings are in agreement with the current literature based on healthy cohorts5–9,16,22.

One concern with the use of chemical stabilization was the introduction of biases with regard to changes in the relative abundance of certain bacteria. Two studies using 16S rRNA gene sequencing found a significant increase in the Sutterella genus in SF versus FF samples5,9. While another study found significant differences in the relative abundances of Faecalibacterium, Sporobacter, Clostridium XVIII, and Clostridium XIVa, with differences being exacerbated in samples of low diversity8. However, we found no difference in the relative abundance of these or any other bacteria in our 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis. In our shotgun metagenomic analysis there were minor differences in several bacteria driven only by a few sample pairs. This shows that differences in taxonomical abundance between methods are inconsistent across studies and may be due to background noise. Additionally, in the case of Hill et al., differences could also stem from comparing the SF protocol with directly processed samples (i.e. direct DNA extraction prior to freezing). Moreover, previous studies in healthy subjects support our conclusion being that there is little difference between SF and FF methods5–7,14–16,18.

Limitations to our study may include the non-homogenisation of samples. It has been shown that sampling from different parts of a stool can give different microbial compositional results20. However, stool sampling is random and therefore the paired design of our study should control for the non-homogenisation. Another potential limitation to our study is the fact that a number of FF samples were not frozen directly (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table S1). However, all of these samples were kept at 4 °C until frozen. Previous studies have shown that cold storage can preserve microbial composition for a short period of time and up to 1 week6,8,9,26,27. This difficulty in direct freezing highlights the need for methodologies that allow for more flexibility between sampling and freezing, as immediate freezing is not always possible in a hospital setting. Finally, there was a slight batch effect in our 16S rRNA gene sequencing data due to an uneven distribution of FF versus SF samples in sequencing runs. This mainly affected reverse-end sequence quality and related variance between batches was minimized during processing. All reads went through the same quality control process, as described in our methods and results, and there were no observed microbial compositional differences between samples run on different batches. Importantly, batch-free shotgun metagenomic data yielded markedly similar results to the 16S rRNA gene sequencing data.

In conclusion, chemical stabilization (SF) proved to be comparable to freshly frozen (FF) stool samples in a diseased, low microbial diversity, cohort. We confirmed this by statistical examination of measurements by two independent high-throughput sequencing technologies, namely 16S rRNA gene and shotgun metagenomic sequencing. We further showed that use of stabilization techniques maintains reproducibility in cross-sectional studies by minimizing technical variance in sample handling. Our results support the use of chemical stabilization to increase the feasibility of hospital biobank stool sample collection, which will help facilitate the collection of longitudinal faecal microbiome samples from diseased patient groups.

Methods

Sample collection

Two samples (i.e. aliquots) were taken from each stool by the patient or nursing staff at the same time-point. The EasySampler® Stool Collection Kit was used to hold the stool above toilet water during collection. If patients were bedridden, samples were collected directly from stool in bedpans. No stool was stored prior to sampling (i.e. sampling was done directly after defecation) and stool material was not homogenised. FF samples were placed in a non-sterile tube without stabilization fluid and delivered to the PERSIMUNE biobank by urgent hospital carrier and frozen directly during regular working hours (i.e. Monday-Friday, 8am-3pm). If outside of regular working hours, the FF sample would still be delivered to the biobank by urgent hospital carrier but then placed in the biobank refrigerator at 4 °C until regular working hours when it would then be frozen. SF samples were placed in the OMNIgene.GUT tube (containing stabilization fluid) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and delivered to the PERSIMUNE biobank by non-urgent hospital carrier. Non-urgent hospital carrier meant that samples could be kept at room temperature for up to several days prior to freezing. Due to the need for swift delivery of FF samples, no samples were taken at patients’ homes, i.e. all stool was collected at the hospital.

All samples were handled by personnel at the PERSIMUNE biobank. Half of the SF samples (n = 13) were further aliquoted into two sterile tubes prior to freezing, whereas remaining SF samples and all FF samples were frozen directly without further aliquoting. All samples were frozen at −80 °C.

The OMNIgene.GUT (DNA Stabilized-frozen Inc., Ottawa, Canada) stabilisation tube was chosen as the best candidate for our SF protocol. No commercial influence on this decision was allowed, i.e. this decision was not made to promote a specific brand, we did not consult with marketing holders, and did not receive financial support. The decision was based on a review of available documentation and literature: OMNIgene.GUT was found to have the least effect on gut microbiome composition compared to other stabilization fluids9, with results generally being comparable to FF samples5,8,15 and differences among sampling methods being of a lower scale than those between individuals6,8,16. The OMNIgene.GUT stabilisation tube should allow samples to be kept at room temperature for up to 60 days (according to manufacturer guidelines) and a previous study (based on a healthy cohort) has shown that the OMNIgene.GUT collection kit gave similar results after 28 days at room temperature as samples with freshly-extracted DNA7. For additional information regarding the stabilizer decision process, and an overview of stabilization comparison studies please see Supplementary Methods.

Sample shipment

All samples (26 FF and 26 SF, i.e. 52 paired samples) were transported on dry ice to the IrsiCaixa AIDS Research Institute in Spain for 16S rRNA gene and shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

DNA extraction

All samples were thawed on ice and DNA was extracted from ~200 mg of each faecal sample using the PowerSoil DNA Extraction Kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, US). Extracted DNA was then stored at −80 °C until sequencing.

Library construction and sequencing

16S rRNA gene sequencing

DNA was PCR amplified using primers for targeting regions flanking the variable regions V3-4 of the 16S rRNA gene (expected amplicon size ~460 base pairs). Primers were those described in the “MiSeq rRNA Amplicon Sequencing” protocol from Illumina, which already have the Illumina adapter overhang nucleotide sequences added to the 16S rRNA V3-V4 specific-primers, i.e.: 16S_F 5′-(TCG TCG GCA GCG TCA GAT GTG TAT AAG AGA CAG CCT ACG GGN GGC WGC AG)-3′ and 16S_R 5′-(GTC TCG TGG GCT CGG AGA TGT GTA TAA GAG ACA GGA CTA CHV GGG TAT CTA ATC C)-3′.

Amplifications were performed in triplicate 25 μL reactions, each containing 2.5 μL of non-diluted DNA template, 12.5 μL of KAPA HiFi HotStart Ready Mix (containing KAPA HiFi HotStart DNA Polymerase, buffer, MgCl2, and dNTPs, KAPA Biosystems Inc., Wilmington, MA, USA), and 5 μL of each primer at 1 μM. Thermal cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturation step (3 min at 95 °C), followed by 30 cycles of denaturation (30 sec at 95 °C), annealing (30 sec at 55 °C) and extension (30 sec at 72 °C). These were followed by a final extension step of 10 min at 72 °C. Once the desired amplicon was confirmed in 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, all three replicates were pooled and stored at −30 °C until sequencing library preparation. Amplified DNA templates were cleaned-up for non-DNA molecules and Illumina sequencing adapters and dual indices were attached using Nextera XT Index Kit (Illumina, Inc.) followed by the corresponding PCR amplification program as described in the MiSeq. 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing protocol. After a second round of clean-up, amplicons were quantified using Quant-iT™ PicoGreen® dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, MA, USA) and diluted in equimolar concentrations (4 nM) for further pooling. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeqTM platform according to the manufacturer’s specifications to generate paired-end reads of 300 base-length in each direction. Samples were sequenced in two batches (not all sample pairs were sequenced in the same batch).

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing

Whole faecal DNA was chemically fragmented using the Nextera-XT® Illumina kit. One library of approximately 300-basepair-clone insert size was constructed for each sample. Total faecal DNA was sequenced in five runs on an Illumina Hi-Seq® platform at the Institut de Medicina Predictiva del Cancer (IMPPC), Badalona, Spain.

Pre-processing and quality control

16S rRNA gene sequencing data

The FastQC software28 and the R(v3.5.0)29/DADA230 plotQualityProfile was used to assess raw sequence quality. Primer trimming and read merging was performed using Cutadapt31 and PEAR (Illumina Paired-End reAd merger)32. Non-merging reads and those with unidentified primers were discarded. Resulting reads were put into the R(v3.5.0)29/DADA230 pipeline and subsequently quality filtered and trimmed. Briefly, reads were trimmed by 6 nucleotides from the start of the read, all were truncated at the first nucleotide with a quality score of ≤5 (if there was one) and those with ≥2 expected errors in the read were discarded. Reads with <350 base pairs after filtering and trimming were removed. One million random filtered reads were used to create the error model in DADA230. Chimeric sequences were filtered off using a consensus approach. Samples with <10,000 read counts after processing were discarded. If one sample failed quality control the sample pair was removed from further analysis.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing data

Specific adapters were removed using the Illumina HiSeq software and Trimmomatic33. Trimmomatic33 was also used for quality trimming (nucleotides were trimmed from the start or end of the read if they had a quality score <30, then using a sliding window approach, reads were cut if the average quality of 4 nucleotides was <30). Reads <50 base pairs were removed. Paired reads were mapped with bowtie234 to the human genome (GRCh38). All read pairs where one or both mates mapped to the human genome were discarded. Final read quality was assessed using the R package ShortRead35 and bowtie234 output files. Samples with <1 million reads were removed from further analysis. If one sample failed quality control the sample pair was removed from further analysis.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted with approval from the Danish Ethical Committee (J.nr.H-16047481). All patients had given informed consent to the donation and storage of stool samples for microbial research. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Taxonomy and diversity measures

16S rRNA gene sequencing data

Taxonomy was assigned through alignment to the RDP (Ribosomal Database Project)36 using the R(v3.5.0)29/DADA230 program. Taxonomical annotation was used to remove all OTUs assigned as mitochondria or chloroplasts, all OTUs assigned a non-bacterial kingdom and all OTUs present in <2 samples. The filtered OTU table was used in the R(v3.5.0)29/Phyloseq37 package to calculate relative abundances (at genus and species level), alpha diversity measures (Shannon and Simpson indexes) and beta diversity measures (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity; used as input for ordination analysis using non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS)). Specifically, relative abundances were based on OTU counts and were normalised as percentages (100 * (x/sum(x))) at species and genera taxonomy levels. Alpha diversity measures were calculated based on OTU counts without prior normalisation. Beta diversity measures were calculated based on normalised (x/sum(x)) OTU counts.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing data

Taxonomical annotation was assigned using MetaPhlAn v2.038. The relative proportions calculated from MetaPhlAn v2.038 on genus and/or species level were used to calculate relative abundances, alpha diversity measures (Shannon and Simpson indexes) and beta diversity measures (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity; used as input for ordination analysis using non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS)) in the R(v3.5.0)29/Phyloseq37 package. Relative abundances were calculated as percentages (i.e. relative proportions were multiplied by 100) at both species and genera taxonomy levels. Due to alpha diversity measures often being calculated based on unnormalized data, we used the rounded fraction of the relative proportions of bacterial species from MetaPhlAn v2.038 (i.e. relative proportion * 10,000 rounded up to the closest integer) to calculate these measures. For beta diversity measures the relative proportion values of bacterial species could be used directly (i.e. values did not need to be re-normalised prior to calculation).

MetaPhlAn v2.038 also provided estimations of the number of reads that should come from a given species by considering the coverage of the species’ markers and the length of the genome (taken from reference genomes). Using the estimated number of reads per genera a count table was created for shotgun taxonomical data compatible with the R(v3.5.0)29/PhyloSeq37 package. This count table, based on the estimation of reads from bacterial genera, was used for later DESeq239 analyses.

Gene richness was calculated using bowtie234 to map filtered reads to the IGC (Integrated Gene Catalogue)25. Based on a rarefaction curve of number of new unique genes and number of mapped reads (counting forward reads only), a cut-off of 5 million mapped reads was decided to calculate gene richness (Supplementary Fig. S1). Only forward reads were used to calculate the number of unique genes, with a maximum of 1 unique gene per read.

Statistical analysis

The following statistical analyses were performed for both 16S rRNA gene and shotgun metagenomic sequencing data. Detection of differentially abundant bacterial genera between methods was performed using the R(v3.5.0)29/PhyloSeq37 and R(v3.5.0)29/DESeq239 packages. Using the Wald test in DESeq239, SF and FF methods were compared for potential statistical differences in their geometric means of bacterial genera. PERMANOVA (adonis) tests (via the R(v3.5.0)29/vegan package40) were also performed using Bray-Curtis distances to test for a potential association between sampling methods and microbiota composition. For all statistical analyses, P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

16S rRNA gene sequencing data

The filtered OTU count table created through R(v3.5.0)29/DADA230 with taxonomy down to genera-level was used for the DESeq239 analysis. Normalised (x/ (sum (x)) OTU values from the same table were used for the PERMANOVA (adonis) test.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing data

Values from the created count table (based on the estimated number of reads from bacterial genera calculated by MetaPhlAn v2.038) was used for the DESeq239 analysis. For the PERMANOVA (adonis) test, proportional abundances (calculated by MetaPhlAn v2.038) were used. Gene richness differences between methods (shotgun metagenomic sequencing data only) were assessed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the IGTP Genomics and Bioinformatics Core Facilities (Maria Pilar Armengol, Lauro Sumoy and Iñaki Martínez) for their contribution to this publication. IrsiCaixa is supported by the RED de SIDA RD16/0025/0041 co-financed by the ISCIII and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), “Investing in your future”. We would also like to thank those involved at the PERSIMUNE biobank situated at Rigshospitalet (Erik Sørensen, Betina Poulsen and Charlotte Matthews) for their contribution to this publication. In addition, we thank the staff and patients at the haematological department, Rigshospitalet, for their contribution to sample collection. This study was funded by the Danish Research Foundation [grant number DNRF126], the Svend Andersen Foundation and the Lundbeck Foundation [grant number R218-2016-1482]. None of the funding bodies had any influence on the study design, the collection, analysis or interpretation of data or the writing of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

H.S., J.L., M.H. and E.I. designed the study. M.N.-J. and R.P. performed the sequencing. M.J., M.N.-J., C.M. and E.I. wrote the computer pipeline. M.J., M.N.-J., C.M., D.M., R.P., J.L. and E.I. contributed to the framework and statistical plan of the study. E.I. wrote the first draft of the paper, with M.J. and C.M. contributing to all figures. All authors made substantial contributions to the analysis of data, have been involved in drafting the manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analysed during this study are derived from patients treated in Denmark. The datasets contain sensitive patient data governed by GDPR and Danish law. Due to Danish legislation (Act No. 502 of 23 May 2018) and approvals granted by the Danish Data Protection Agency, it is not possible to upload raw data to a publicly available database. However, access to these data can be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, provided a data transfer agreement is entered into according to current regulations.

Competing Interests

The authors state that there is no conflict of interest in the work presented. OMNIgene.GUT kits were purchased from DNA Genotek and none of the authors owned stock, were under the employment or consulted for the DNA Genotek company.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Henrik Sengeløv and Cameron MacPherson jointly supervised this work.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-49956-7.

References

- 1.Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;375:2369–2379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1600266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert JA, et al. Microbiome-wide association studies link dynamic microbial consortia to disease. Nature. 2016;535:94–103. doi: 10.1038/nature18850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young VB. The role of the microbiome in human health and disease: an introduction for clinicians. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2017;356:j831. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han M, et al. A novel affordable reagent for room temperature storage and transport of fecal samples for metagenomic analyses. Microbiome. 2018;6:43. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0429-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panek M, et al. Methodology challenges in studying human gut microbiota - effects of collection, storage, DNA extraction and next generation sequencing technologies. Scientific reports. 2018;8:5143. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23296-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penington JS, et al. Influence of fecal collection conditions and 16S rRNA gene sequencing at two centers on human gut microbiota analysis. Scientific reports. 2018;8:4386. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22491-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson EL, et al. A robust ambient temperature collection and stabilization strategy: Enabling worldwide functional studies of the human microbiome. Scientific reports. 2016;6:31731. doi: 10.1038/srep31731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill CJ, et al. Effect of room temperature transport vials on DNA quality and phylogenetic composition of faecal microbiota of elderly adults and infants. Microbiome. 2016;4:19. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0164-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choo JM, Leong LE, Rogers GB. Sample storage conditions significantly influence faecal microbiome profiles. Scientific reports. 2015;5:16350. doi: 10.1038/srep16350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehta RS, et al. Stability of the human faecal microbiome in a cohort of adult men. Nature microbiology. 2018;3:347–355. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0096-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogtmann E, et al. Comparison of Collection Methods for Fecal Samples in Microbiome Studies. American journal of epidemiology. 2017;185:115–123. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathay C, et al. Method optimization for fecal sample collection and fecal DNA extraction. Biopreservation and biobanking. 2015;13:79–93. doi: 10.1089/bio.2014.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dominianni C, Wu J, Hayes RB, Ahn J. Comparison of methods for fecal microbiome biospecimen collection. BMC microbiology. 2014;14:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voigt AY, et al. Temporal and technical variability of human gut metagenomes. Genome biology. 2015;16:73. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0639-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szopinska JW, et al. Reliability of a participant-friendly fecal collection method for microbiome analyses: a step towards large sample size investigation. BMC microbiology. 2018;18:110. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1249-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z, et al. Comparison of Fecal Collection Methods for Microbiome and Metabolomics Studies. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2018;8:301. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song, S. J. et al. Preservation Methods Differ in Fecal Microbiome Stability, Affecting Suitability for Field Studies. mSystems1, 10.1128/mSystems.00021-16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Wu GD, et al. Sampling and pyrosequencing methods for characterizing bacterial communities in the human gut using 16S sequence tags. BMC microbiology. 2010;10:206. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al KF, Bisanz JE, Gloor GB, Reid G, Burton JP. Evaluation of sampling and storage procedures on preserving the community structure of stool microbiota: A simple at-home toilet-paper collection method. Journal of microbiological methods. 2018;144:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorzelak MA, et al. Methods for Improving Human Gut Microbiome Data by Reducing Variability through Sample Processing and Storage of Stool. PloS one. 2015;10:e0134802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angebault C, et al. Combined bacterial and fungal intestinal microbiota analyses: Impact of storage conditions and DNA extraction protocols. PloS one. 2018;13:e0201174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ezzy AC, et al. Storage and handling of human faecal samples affect the gut microbiome composition: A feasibility study. Journal of microbiological methods. 2019;164:105668. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2019.105668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centre of Excellence for Personalised Medicine for Infectious Complications in Immune Deficiency (PERSIMUNE), http://www.persimune.dk/ (2019).

- 24.Wang H, et al. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet. 2015;388:1459–1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, et al. An integrated catalog of reference genes in the human gut microbiome. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32:834–841. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tedjo DI, et al. The effect of sampling and storage on the fecal microbiota composition in healthy and diseased subjects. PloS one. 2015;10:e0126685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franzosa EA, et al. Relating the metatranscriptome and metagenome of the human gut. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:E2329–2338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319284111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrews, S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data, http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc 2010).

- 29.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (2018).

- 30.Callahan BJ, et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin, M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences From High-Throughput Sequencing Reads, http://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/stable/index.html (2019).

- 32.Zhang J, Kobert K, Flouri T, Stamatakis A. PEAR: a fast and accurate Illumina Paired-End reAd mergeR. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2014;30:614–620. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langmead Ben, Salzberg Steven L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods. 2012;9(4):357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan M, et al. ShortRead: a bioconductor package for input, quality assessment and exploration of high-throughput sequence data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2009;25:2607–2608. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/aem.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PloS one. 2013;8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Truong DT, et al. MetaPhlAn2 for enhanced metagenomic taxonomic profiling. Nat Methods. 2015;12:902–903. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome biology. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oksanen JBF, et al. R package vegan: Community Ecology Package. version. 2018;2:5–2. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during this study are derived from patients treated in Denmark. The datasets contain sensitive patient data governed by GDPR and Danish law. Due to Danish legislation (Act No. 502 of 23 May 2018) and approvals granted by the Danish Data Protection Agency, it is not possible to upload raw data to a publicly available database. However, access to these data can be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, provided a data transfer agreement is entered into according to current regulations.