ABSTRACT

Bacteroides fragilis is a member of the normal microbiota of the lower gastrointestinal tract, but some strains produce the putative tumourigenic B. fragilis toxin (BFT). In addition, B. fragilis can produce multiple capsular polysaccharides that comprise a microcapsule layer, including an immunomodulatory, zwitterionic, polysaccharide A (PSA) capable of stimulating anti-inflammatory interleukin-10 (IL-10) production.

It is known that the PSA promoter can undergo inversion, thereby regulating the expression of PSA. A PCR digestion technique was used to investigate B. fragilis capsular PSA promoter orientation using human samples for the first time. It was found that approximately half of the B. fragilis population in a healthy patient population had PSA orientated in the ‘ON’ position. However, individuals with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) had a significantly lower percentage of the B. fragilis population with PSA orientated ‘ON’ in comparison with the other patient cohorts studied. Similarly, the putative tumourigenic bft-positive B. fragilis populations were significantly associated with a lower proportion of the PSA promoter orientated ‘ON’.

These results suggest that the proportion of the B. fragilis population with the PSA promoter ‘ON’ may be an indicator of gastrointestinal health.

KEYWORDS: Bacteroides fragilis, inflammatory bowel disease, capsular polysaccharide, phase variation, interleukin-10, invertible promoter, mucosal colonisation

Introduction

Although Bacteroides fragilis is a common gut commensal, it is also considered an opportunistic pathogen, often isolated from abdominal abscesses, bacteraemia and peritonitis. Some B. fragilis strains, known as Enterotoxigenic B. fragilis (ETBF), can produce a putative carcinogenic toxin, Bacteroides fragilis toxin (BFT). BFT has been demonstrated to promote colonic cell proliferation1 and DNA damage2 in mammalian cell culture and animal models. Experimental mice challenged with ETBF develop acute colonic inflammation followed by hyperplastic changes to the epithelium.3

IBD is a clinical condition characterized by chronic inflammation in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and is comprised of two main types, Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).4 The two subtypes differ primarily on the GI tract location and nature of inflammation. The principal features differentiating UC and CD are that in CD inflammation can be transmural (across the entire wall of the bowel) and may be present anywhere along the length of the GI tract. In contrast, UC inflammation is limited to the mucosal layer and often starts in the rectum spreading proximally.

Bacterial capsules are extracellular structures, typically comprised of polysaccharide, outside the cell envelope. Capsule possession appears to be part of a strategy to evade the host immune system, for example, by preventing the formation of a complement attack complex, and to avoid engulfment by phagocytosis.5 They also have roles in adhesion and colonization and for these reasons can be considered virulence factors; in addition, capsular mutants are often avirulent.6

B. fragilis strains produce a polysaccharide microcapsule.7The B. fragilis pangenome is capable of synthesizing a variety of capsular polysaccharides (PS) that comprise the microcapsule layer. Each type of capsular PS has its own locus of PS biosynthesis genes.8 There is a single promoter region upstream of each of the polysaccharide biosynthetic loci. With the exception of PSC, the promoters can undergo inversion of their DNA.9This enables switching on and off of PS synthesis to alter capsular PS expression in a phenotypic switching process known as phase variation. The region of invertible DNA is flanked by repeat sequences known as fragilis inversion crossover sites (fix).10Promoter DNA inversion is mediated by a serine site-specific recombinase designated as multiple promoter invertase, Mpi.11

The first gene of all eight PS biosynthetic loci is the upxY gene where x is replaced by a to h depending on the specific PS locus. The UpxY family of proteins share homology amongst individual proteins, but contain a region of amino acid sequence in the N terminal half that are specific for the individual biosynthetic loci (a-h).12 The UpxY proteins are able to associate with RNA polymerase in the 5' untranslated region (UTR) to prevent premature termination of transcription. The adjacent upxZ genes code for a family of proteins able to prevent the transcriptional antitermination function of other PS loci UpxY proteins. Altogether the UpxZ proteins prevent simultaneous synthesis of PS types in a single bacterial cell by a hierarchical system of regulation, with PSC the default locked ‘ON’ promoter.13

The most studied of the B. fragilis capsular polysaccharides is polysaccharide A (PSA). The structure of PSA comprises a tetrasaccharide repeating unit, which unusually for a capsular polysaccharide is zwitterionic, comprising a positive amino group and a negative carboxyl group.14The repeating unit makes a right-handed helix with the charged groups externally facing allowing for interaction with other molecules.15 PSA has been studied extensively due to its immunomodulatory properties, which in part is due to its zwitterionic nature and structure.

Outer-membrane vesicle (OMV)-associated PSA16 can interact with Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) on dendritic cells (DCs).17,18 DCs process PSA where it is presented on Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II (MHC II)19 molecules that interact with T-cell receptors. The consequence of this interaction is an expansion of interleukin 10 (IL-10) producing CD4+ cells.20 IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine and an increase in its production by PSA has been shown to mediate the prevention of H. hepaticus-induced colitis in mice.21 PSA signaling via TLR2 also suppresses Th17 and interleukin-17 (IL-17) production to promote mucosal colonization of B. fragilis.17 B. fragilis therefore appears to exhibit both commensal and pathogenic traits.

In this paper we determined the B. fragilis PSA promoter orientation in vivo, subsequently finding significant differences amongst patient cohorts.

Results

Identification of a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in B. fragilis UpaY

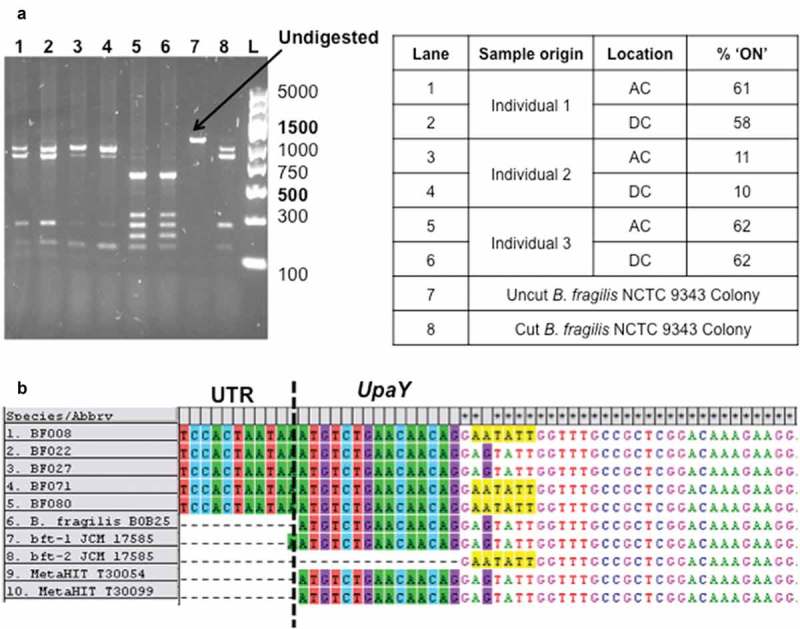

The ON/OFF status of the PSA gene was determined by analysis of the PCR-generated promoter region after SspI restriction enzyme digestion. Some isolates of B. fragilis had a different SspI digest pattern from that expected. Figure 1(a) shows lanes 5 and 6 have additional bands at approximately 200, 250 and 690 bp. DNA sequencing of undigested PCR amplicons from samples, with or without the alternative banding pattern, revealed an additional SspI recognition sequence (Figure 1(b)) in the UpaY gene due to a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP).

Figure 1.

Identification of a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in B. fragilis UpaY (a) An example agarose gel depicting PSA promoter PCR products digested with SspI restriction enzyme. PCR was performed on extracted colonic biopsy DNA from individual clinical samples and digestion products loaded in lanes 1–6. Samples were obtained from either the ascending colon (AC) or descending colon (DC) locations. GeneRuler express ladder marker sizes are given to the left of the gel with brighter reference bands labelled in bold. (b) DNA sequences aligned in MEGA of PSA Promoter PCR products from patient samples, published sequences and sequences found from the MetaHIT metagenome project. The additional SspI restriction enzyme cut sequence in some isolates is highlighted in yellow. UTR = Untranslated region.

B. fragilis PSA promoter orientation in vivo

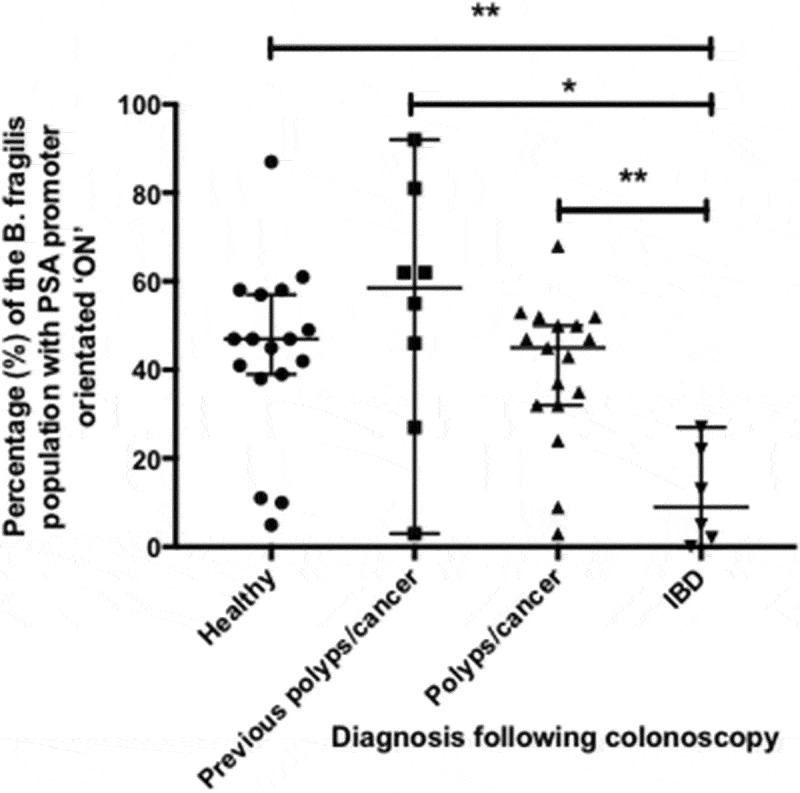

The PSA promoter orientation within a B. fragilis population was determined in vivo using DNA extracted from colonic biopsy samples. The PSA promoter orientation in healthy individuals had a 95% CI around the median of between 40% and 60% of the B. fragilis population (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of B. fragilis cells in patient samples with the PSA promoter in the ON orientation: comparison amongst patient groups percentage of B. fragilis cells with the PSA promoter in the ON orientation as separated by patient cohorts. Error bars indicate the median and 95% confidence level (C.I.). Significant differences amongst patient groups were determined using one-way ANOVA and pairwise differences between patient groups established using Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. ** = p value less than or equal to 0.01; * = p value less than or equal to 0.05.

The percentage of the B. fragilis population with the PSA promoter orientated ON was not significantly different in samples from the same individual taken from the ascending and descending colon as determined by a paired, two-tailed t test (data not shown) (p = 0.976). As a consequence, the subsequent patient group analysis used an average percentage of all samples obtained from the same individual.

PSA promoter orientation is significantly different in individuals with IBD

Individuals were grouped according to the results of the diagnostic colonoscopy. Figure 2 shows that individuals with IBD had a significantly lower proportion of B. fragilis with PSA orientated ON compared with healthy individuals (p = 0.007), those previously with colonic polyps/cancer (p = 0.002) or those with newly diagnosed polyps/cancer (p = 0.016). F-tests between patient groups determined that there was no significant difference between the variances of the different patient group populations.

In vivo Enterotoxigenic B. fragilis (ETBF) have a significant lower proportion of the population with the PSA promoter orientated ON

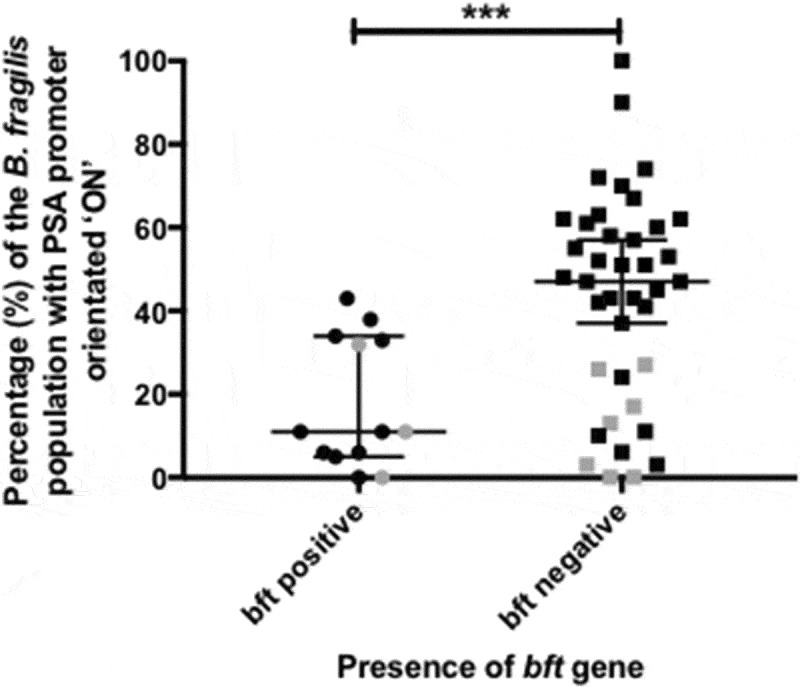

We sought to determine any relationship between PSA promoter orientation and bft positivity. The bft gene was found to be significantly associated (p = 0.0007) with a lower proportion of B. fragilis PSA promoter orientated in the ON position (Figure 3). This result appears to be independent of the association between PSA promoter orientation and IBD.

Figure 3.

Percentage of B. fragilis cells with the Polysaccharide A (PSA) promoter in the ON orientation: comparison between bft positive and negative samples Percentage of B. fragilis cells with the PSA promoter in the ‘ON’ orientation as separated by colonic biopsy samples positive for the B. fragilis toxin gene (bft). Samples from individuals with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) are highlighted in grey. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine whether differences between bft positive and negative samples were significant. Error bars indicate the median and 95% confidence level (C.I.).

PSA promoter orientation is not correlated with IL-10 levels

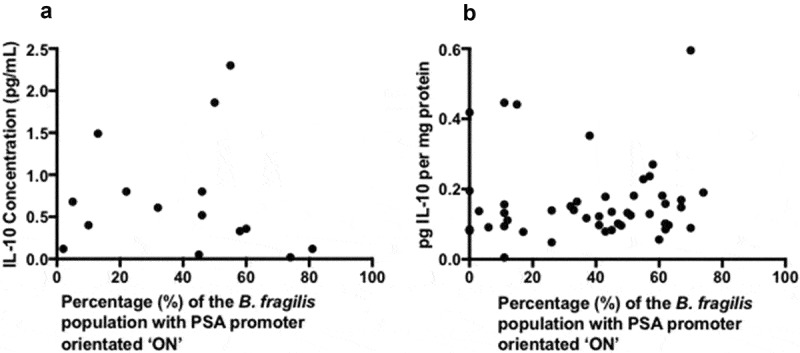

As a result of the immunomodulatory properties of PSA, the most likely downstream consequence of PSA promoter orientation is an impact on IL-10 levels. Measuring serum and biopsy tissue levels of IL-10 revealed no correlation with PSA promoter orientation (p = 0.417 and p = 0.455, respectively) (Figure 4). In addition, neither serum nor biopsy tissue IL-10 had any significant associations with the aforementioned patient groups.

Figure 4.

Correlation analysis of serum IL-10 or tissue IL-10 and B. fragilis PSA promoter orientation correlation was tested statistically using spearman’s rank correlation (a) Scatter graph to identify any correlation between serum IL-10 concentration (pg/mL) and B. fragilis PSA promoter orientation (b) Scatter graph to identify any correlation between tissue IL-10 concentration (pg/mg protein) and B. fragilis PSA promoter orientation.

Discussion

We describe here the first analysis of B. fragilis PSA promoter orientation from human samples, and their possible correlation with disease states. The analysis was conducted on DNA extracted from snap frozen samples, and therefore represents as closely as possible PSA promoter orientation in vivo. PSA promoter orientation has not previously been studied in human tissue samples. The nearest comparable research was carried out in fecal samples from various mouse models22, where it was found that in monocolonized mice after 9 weeks approximately 80% of B. fragilis has the PSA promoter orientated on, but, after 11 weeks, this value decreased towards ~50%. In the most comparable result from our study it was observed that in a healthy cohort there is a heterogeneous population of B. fragilis in terms of capsular polysaccharide. The percentage of B. fragilis with the PSA promoter orientated ON in healthy individuals had a median value of between 40% and 60% with a 95% C.I. (Figure 2). This concurs with a theory of the biological significance of phase variation, that it creates heterogeneity within a clonal population allowing for diversity to protect against sudden environmental stresses.23

Whilst determining the B. fragilis PSA promoter orientation in patient biopsies an alternative restriction enzyme cut pattern was observed, leading to the identification of a SNP in the upaY gene. The SNP is surrounded by a conserved DNA sequence (Figure 1(b)) and upaY is conserved across many Bacteroides capsular polysaccharides.9We identified the nucleotide change in multiple individuals; altogether this may suggest it is positively selected. Whether the SNP has a functional effect is as yet undetermined, although it is noteworthy that due to the degeneracy of the genetic code, the DNA sequence change observed (GAG to GAA) does not result in a difference in amino acid sequence.

The differences in PSA expression seen in individuals with IBD or bft positive B. fragilis strains may be explained by the role of capsular polysaccharides in the relationship between glycan utilization and mucosal colonization.24 It is known that B. fragilis capsular polysaccharides are important for colonisation, as an acapsular mutant was outcompeted by a strain capable of synthesizing a single capsular polysaccharide25, while a PSA knockout strain led to reduced levels of mucosally associated B. fragilis.17 The B. fragilis commensal colonisation factors (CCF) genetic locus is hypothesized to sense host-derived glycans, as the ccf locus is highly expressed during colonisation of the GI tract.26 Indeed, when the ccf locus is mutated PSA expression is increased, occupation of a nutrient niche is defective and single-strain stability is eliminated.27 In summary, CCF sensing of host glycans influences the expression of capsular polysaccharides, which encourage IgA binding resulting in stable colonization.27 ETBF strains have been shown to reduce mucus depth28, which would explain the need for expression of an alternative CPS as seen in the results presented here. Similarly, the distinctive PSA promoter orientation seen in individuals with IBD may reflect an altered glycan composition of the intestinal mucosa. Studies have revealed a reduced mucus carbohydrate content in IBD and individuals with UC have less complex glycans.29 Taken together PSA promoter orientation in B. fragilis may be an indicator for intestinal homeostasis.

The reduced PSA expression seen in the IBD group may have consequences for inflammation, given that PSA can prevent H. hepaticus-induced colitis in mice.21 As a result, we investigated IL-10 levels. No correlation was found between PSA promoter orientation and IL-10 levels. It is possible that any effect of changed PS promoter orientation was masked by other immunomodulatory molecules produced in the complex microbiological environment of the large colon. B. fragilis is able to synthesise many different types of polysaccharide, including chemically different versions of PSA, e.g. PSA215 and PSB that are also zwitterionic.14 Taxonomically diverse species, including other Bacteroides species, are predicted to produce the amino sugar acetamino-2, 4, 6-trideoxygalactose (AATGal). AATGal contains a positive charge, key for the immunomodulatory properties of zwitterionic capsular polysaccharides.30 Therefore, it is believed that other commensal gastrointestinal bacteria can produce immunomodulatory zwitterionic capsular polysaccharides. Altogether this adds to the complexity of the relationship between PSA promoter orientation and IL-10 levels.

In conclusion, in a healthy colon approximately half of the B. fragilis population have the PSA promoter oriented ON while individuals with IBD or those colonized with ETBF have a lower proportion of the B. fragilis community with the PSA promoter orientated ON. The implications of these findings on patient health remain to be discovered.

Materials and methods

Subject recruitment and ethical approval

Participants were recruited and samples collected from Endoscopy Units at Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Hospital Foundation Trust from patients undergoing a routine diagnostic colonoscopy. Ethical approval was sought from WALES REC 7 committee (REC number: 14/WA/1221) and Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust Research and Development (number: RJ115/N211). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants. Exclusion criteria for recruitment included: under the age of 18, macroscopically active inflammatory bowel disease, antibiotics within the last 4 weeks, positive stool culture for Clostridium difficile. Individuals were divided into cohorts depending on the reason for attendance for, or result of colonoscopy. Subjects were recruited into 4 groups: newly diagnosed polyps/cancer (n = 32), surveillance after previous polyps/cancer (n = 14), inflammatory bowel disease (n = 14) and healthy controls (n = 22). Healthy controls were defined as individuals with anaemia or rectal bleeding as an indication for colonoscopy with no signs of GI disease upon colonoscopy.

Colonic biopsy collection

During colonoscopy mucosal biopsies were collected using endoscopic biopsy forceps following advancement of the colonoscope to the cecum. Two mucosal biopsies from the ascending colon and two from the descending colon were collected and immediately frozen on dry ice. Biopsy samples collected from individuals with newly diagnosed tumors larger than 1 cm were collected on the tumor (x4 biopsies), 2 cm distal (x4 biopsies) and 10 cm distal (x4 biopsies).

Intestinal biopsy DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from intestinal biopsy samples using the FastDNA SPIN kit for soil (MP Biologicals, catalog no. 116560200) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA extraction included a bead-beating step using a FastPrep24 (MP Biologicals, catalog no. 116002500) homogenizer. Other DNA extraction steps were carried out in a Class II microbiological safety cabinet (Nuaire). DNA aliquots were placed into 0.5 mL DNase free DNA LoBind® microcentrifuge tubes (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. Z666548). Extracted DNA aliquots were stored at −20°C until further processing, while extracted DNA was refrigerated short-term at 4°C. Extracted DNA was initially subjected to PCR using universal primers to determine suitability of the DNA for further PCR analysis.

Microbiology

A reference Culti-LoopTM strain (Thermo Scientific, catalog no. R4601251) of Bacteroides fragilis NCTC 9343 was streaked onto reduced Fastidious Anaerobe Agar (Lab M Limited, catalog no. LAB090) with 5% (v/v) defibrinated horse blood (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, catalog no. SR0050C) for use as a positive control. Bacteria were cultured in a MACS-MG-1000 anaerobic workstation (Don Whitley) with an atmosphere of 80% N2, 10% H2 and 10% CO2 at 37°C.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

PCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 25 μL with each reaction mixture containing: 12.5 μL 2X DreamTaq™ _polymerase mastermix (Fermentas, Waltham, USA), 10.5 μL sterile molecular grade H2O (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.5°μL forward primer 10°pmol/μL (Eurofins genomics), 0.5°μL reverse primer (10°pmol/μL) (Eurofins genomics) and 1°μL of template DNA. All PCR reactions were normalized to use 40 ng of extracted biopsy DNA. PCR reactions were carried out in a TC 412 thermal cycler using cycling conditions of an initial denaturation step of 95°C; 30 cycles of amplification consisting of denaturation (45 s at 95°C), annealing (45 s at X°C) and extension (X at 72°C); and a final extension of 15 min at 72°C where X is variable for each PCR target. A no DNA template, negative control was included in every PCR.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect bft

PCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 25°μL with each reaction mixture containing: 12.5°μL 2°X°DreamTaqTM polymerase mastermix (Thermo-Scientific catalog no. K1071) 10.5°μL sterile molecular grade H2O, 0.5°μL forward primer 10°pmol/μL (Eurofins genomics), 0.5 μL reverse primer (10 pmol/μL) (Eurofins genomics) and 1 μL of template DNA. PCR reactions were carried out in a TC 412 thermal cycler using cycling conditions of an initial denaturation step of 5 min at 95°C; 30 cycles of amplification consisting of denaturation (45 s at 95°C), annealing (45 s at 48°C) and extension (25 s at 72°C); and a final extension of 15 min at 72°C. A negative control excluding any DNA template was included in every PCR. PCR primers used to detect bft were:

BFTF2: GAACCTAAAACGGTATATGT31

BFTR1: CAGCTGGGTTGTAGACATCC

DNA agarose gel electrophoresis

PCR amplicons were visualized on 1–2% (w/v) agarose gels. Agarose gels were made using molecular grade agarose (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. A9539) dissolved in 0.5X Tris-Borate EDTA (TBE) buffer (AppliChem, catalog no. A3945) containing 0.01% (v/v) GelRedTM nucleic acid gel stain (VWR, catalog no. 41003). Individual samples were mixed with 6X loading dye (Thermo-Scientific, catalog no. R0611) and visualized on the AlphaImager HP Gel Imaging System (Alpha Innotech). The molecular size of the DNA fragments was estimated using either GeneRuler Express DNA ladder (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, catalog no. SM1553), GeneRuler 100°bp Plus DNA ladder (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, catalog no. SM0321) or Lambda DNA-Hind III Digest (New England Biolabs, catalog no. N3012S) molecular markers.

PSA PCR method

PCR reactions were performed as described previously with exception of annealing temperature at 57°C and an extension time of 70s. PCR primers used were:

PSAF1: TGTGTAAATGATAGGAGGCTAGGG

PSAR1: GTTGACGGAAATGATCGGTATAG

PSA restriction digest method

PSA promoter orientation was determined using a method adapted from references 3 and 12. PCR amplification of DNA extracted from colonic biopsies was carried out using the PSAF1 and PSAR1 primers.

A restriction digest of the PCR amplicons was set up using 19°μL sterile, DEPC treated water (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. 95284), 8°μL PCR product DNA, 2°μL FastDigest green buffer and 1°μL FastDigest SspI enzyme (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, catalog no. FD0774).

The restriction digest (8°μL) was loaded and visualized using DNA agarose gel electrophoresis, as described previously. Agarose gels were visualized using the ChemiDocTM MP UV transilluminator (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and DNA band intensity determined using the Image Lab (version 5.2.1) software (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Protein extraction from intestinal biopsy samples

Colonic biopsies used for IL-10 quantification were stored in RNAlater® at −80°C upon collection before processing. Biopsies were defrosted on ice before excess RNAlater® was removed and ice-cold RIPA lysis and extraction buffer (250 μL) (Thermo Fisher, catalog no. 89900). The sample was incubated on ice for 20–30°min, centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C and then aliquoted and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Interleukin-10 (IL-10) quantification

The human IL-10 ELISA kit (Invitrogen, catalog no. KHC0101) was used to quantify IL-10 concentrations in serum and intestinal biopsy tissue lysates. 15°μL of biopsy lysate diluted in 35°μL standard diluent buffer or 50°μL of serum were added in duplicate. Following a 2°hour incubation at room temperature, the 96 well plate was washed four times using 1X wash buffer. 100°μL Hu IL-10 biotin conjugate was added to all wells except chromogen blanks and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The plate was washed four times with 1 x wash buffer and 100°μL streptavidin-HRP solution was added to all wells except chromogen blanks. The plate was incubated for 30 min and washed four times with 1 x wash buffer. 100°μL stabilized chromogen was added to the plate and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The reaction was stopped using 100°μL stop solution and the plate read at an absorbance of 450 nm.

Tissue IL-10 concentration in pg/mL was normalized against total protein, as determined by Qubit protein assay (Thermo Scientific, catalog no. Q33212), i.e. ELISA IL-10 concentration (pg/mL)/total protein concentration (mg/mL) to obtain a final result in terms of pg IL-10 per mg protein.

Calculations and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism v. 7.0 for Mac OS (GraphPad Software). The percentage of the B. fragilis population with the PSA promoter orientated on was calculated as follows: = (Total band intensity of ‘ON’ fragments/Total band intensity of all fragments) x 100. Significant differences in PSA promoter orientation amongst patient groups were determined using one-way ANOVA and pairwise differences between patient groups established using Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine whether differences between bft positive and negative samples were significant. Correlation between PSA promoter orientation and IL-10 (serum or tissue) was determined statistically using Spearman’s rank correlation.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity; ImmBio.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wu S, Morin PJ, Maouyo D, Sears CL.. Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin induces c-Myc expression and cellular proliferation. Gastroenterol. 2003;124:392–400. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodwin AC, Destefano Shields CE, Wu S, Huso DL, Wu X, Murray-Stewart TR, Hacker-Prietz A, Rabizadeh S, Woster PM, Sears CL, et al. Polyamine catabolism contributes to enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis-induced colon tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:15354–15359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010203108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhee KJ, Wu S, Wu X, Huso DL, Karim B, Franco AA, Rabizadeh S, Golub JE, Mathews LE, Shin J, et al. Induction of persistent colitis by a human commensal, enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis, in wild-type C57BL/6 mice. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1708–1718. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00814-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fakhoury M, Negrulj R, Mooranian A, Al-Salami H. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and treatments. J Inflamm Res. 2014;7:113–120. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S65979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns SM, Hull SI. Loss of resistance to ingestion and phagocytic killing by O-and K-mutants of a uropathogenic Escherichia coli O75: k5strain. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3757–3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Propst KL, Mima T, Choi KH, Dow SW, Schweizer HP. A Burkholderia pseudomallei ΔpurM mutant is avirulent in immunocompetent and immunodeficient animals: candidate strain for exclusion from select-agent lists. Infect Immun. 2010;78:3136–3143. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01313-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasper DL, Hayes ME, Reinap BG, Craft FO, Onderdonk AB, Polk BF. Isolation and identification of encapsulated strains of Bacteroides fragilis. J Infect Dis. 1977;136:75–81. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Comstock LE, Coyne MJ, Tzianabos AO, Pantosti A, Onderdonk AB, Kasper DL. Analysis of a capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis locus of Bacteroides fragilis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3525–3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krinos CM, Coyne MJ, Weinacht KG, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL, Comstock LE. Extensive surface diversity of a commensal microorganism by multiple DNA inversions. Nature. 2001. doi: 10.1038/35107092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patrick S, Parkhill J, McCoy LJ, Lennard N, Larkin MJ, Collins M, Sczaniecka M, Blakely G. Multiple inverted DNA repeats of Bacteroides fragilis that control polysaccharide antigenic variation are similar to the hin region inverted repeats of Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiology. 2003;149:915–924. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coyne MJ, Weinacht KG, Krinos CM, Comstock LE. Mpi recombinase globally modulates the surface architecture of a human commensal bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:10446–10451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832655100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chatzidaki-Livanis M, Coyne MJ, Comstock LE. A family of transcriptional antitermination factors necessary for synthesis of the capsular polysaccharides of Bacteroides fragilis. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:7288–7295. doi: 10.1128/JB.00500-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feria BAB, Weinacht KG, Comstock LE. Trans locus inhibitors limit concomitant polysaccharide synthesis in the human gut symbiont Bacteroides fragilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11976–11980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005039107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baumann H, Tzianabos AO, Brisson JR, Kasper DL, Jennings HJ. Structural elucidation of two capsular polysaccharides from one strain of Bacteroides fragilis using high-resolution NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4081–4089. doi: 10.1021/bi00131a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Kalka-Moll WM, Roehrl MH, Kasper DL. Structural basis of the abscess-modulating polysaccharide A2 from Bacteroides fragilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13478–13483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.25.13478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen XJ, Rawls JF, Randall T, Burcal L, Mpande CN, Jenkins N, Jovov B, Abdo Z, Sandler RS, Keku TO. Molecular characterization of mucosal adherent bacteria and associations with colorectal adenomas. Gut Microbes. 2010;1:138–147. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.3.12360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Round JL, Lee SM, Li J, Tran G, Jabri B, Chatila TA, Mazmanian SK. The toll-like receptor 2 pathway establishes colonization by a commensal of the human microbiota. Science. 2011;332:974–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1206095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dasgupta S, Erturk-Hasdemir D, Ochoa-Reparaz J, Reinecker HC, Kasper DL. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells mediate anti-inflammatory responses to a gut commensal molecule via both innate and adaptive mechanisms. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duan J, Avci FY, Kasper DL. Microbial carbohydrate depolymerization by antigen-presenting cells: deamination prior to presentation by the MHCII pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:5183–5188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800974105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell. 2005;122:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazmanian SK, Round JL, Kasper DL. A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature. 2008;453:620–625. doi: 10.1038/nature07008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Troy EB, Carey VJ, Kasper DL, Comstock LE. Orientations of the Bacteroides fragilis capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis locus promoters during symbiosis and infection. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5832–5836. doi: 10.1128/JB.00555-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Der Woude MW, Bäumler AJ. Phase and antigenic variation in bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:581–611. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.3.581-611.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martens EC, Roth R, Heuser JE, Gordon JI. Coordinate regulation of glycan degradation and polysaccharide capsule biosynthesis by a prominent human gut symbiont. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18445–18457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coyne MJ, Chatzidaki-Livanis M, Paoletti LC, Comstock LE. Role of glycan synthesis in colonization of the mammalian gut by the bacterial symbiont Bacteroides fragilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13099–13104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804220105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SM, Donaldson GP, Mikulski Z, Boyajian S, Ley K, Mazmanian SK. Bacterial colonization factors control specificity and stability of the gut microbiota. Nature. 2013;501:426–429. doi: 10.1038/nature12447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donaldson GP, Ladinsky MS, Yu KB, Sanders JG, Yoo BB, Chou WC, Conner ME, Earl AM, Knight R, Bjorkman PJ, et al. Gut microbiota utilize immunoglobulin a for mucosal colonization. Science. 2018;360:795–800. doi: 10.1126/science.aaq0926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dejea CM, Fathi P, Craig JM, Boleij A, Taddese R, Geis AL, Wu X, DeStefano Shields CE, Hechenbleikner EM, Huso DL, et al. Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis harbor colonic biofilms containing tumorigenic bacteria. Science. 2018;359:592–597. doi: 10.1126/science.aah3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Theodoratou E, Campbell H, Ventham NT, Kolarich D, Pučić-Baković M, Zoldoš V, Fernandes D, Pemberton IK, Rudan I, Kennedy NA, et al. The role of glycosylation in IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:588–600. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neff CP, Rhodes ME, Arnolds KL, Collins CB, Donnelly J, Nusbacher N, Jedlicka P, Schneider JM, McCarter MD, Shaffer M, et al. Diverse intestinal bacteria contain putative zwitterionic capsular polysaccharides with anti-inflammatory properties. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:535–547. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kato N, Liu CX, Kato H, Watanabe K, Tanaka Y, Yamamoto T, Suzuki K, Ueno K. A new subtype of the metalloprotease toxin gene and the incidence of the three bft subtypes among Bacteroides fragilis isolates in Japan. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;182:171–176. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(99)00585-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]