Abstract

Objective:

The goal of the present study was to deconstruct the 17 treatment arms used in the EARLY weight management trials.

Methods:

Intervention materials were coded to reflect behavioral domains and BCTs within those domains planned for each treatment arm. The Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) was employed to determine an emphasis profile of domains in each intervention.

Results:

The intervention arms used BCTs from all of the 16 domains with an average of 29.3 BCTs per intervention arm. All 12 of the interventions included BCTs from the six domains of Goals and Planning, Feedback and Monitoring, Social Support, Shaping Knowledge, Natural Consequences, and Comparison of Outcomes. Eleven of the 12 interventions shared 15 BCTs in common across those 6 domains.

Conclusions:

Weight management interventions are complex. The shared set of BCTs used in the EARLY trials may represent a core intervention that could be studied to determine the required emphases of BCTs and if additional BCTs add or detract from efficacy. Deconstructing interventions will aid in reproducibility and understanding of active ingredients.

Keywords: Obesity interventions, behavior change techniques

Introduction

Compared to other age groups, young adults (18–35 years) experience the greatest rates of weight gain (3;4), alongside increasing rates of cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, and worsening cancer risk. The public health burden due to obesity among young adults is expected to increase, accentuating the need for weight-related interventions.

EARLY (Early Adult Reduction of weight through LifestYle) was an NIH-funded cooperative agreement of seven randomized controlled weight management trials evaluating 17 different treatment arms (RFA-HL-08–007). EARLY was comprised of coordinated but diverse intervention studies, with common data elements, end points, and many inclusion/exclusion criteria; however, the specific treatment arms and target populations at each site differed. (1). Three of the studies focused on weight loss (IDEA, (2), CITY, (3), SMART, (4)). Two studies focused on weight gain prevention (SNAP, (5) CHOICES, (6)), and two studies focused on other outcomes in special populations including preventing weight gain during smoking cessation attempts (TARGIT, (7)), and gestational weight gain and post-partum weight loss (eMoms, (8)). All EARLY interventions were delivered using technology, including the internet, cell phones, apps, and exercise tracking devices.

Behavioral interventions targeting weight are characteristically multi-component including a comprehensive set of strategies to guide changes in diet and activity behaviors to shift energy balance. Weight management clinical trials usually evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment package as a whole. This ‘black box’ approach does not allow for assessing whether all of the intervention strategies are required to produce change or if a more parsimonious set of strategies would be as effective. Weight management interventions have been developed and adapted from large successful interventions such as the Diabetes Prevention Program (9,10) and Look Ahead (11,12). The published descriptions of these interventions typically include information on intervention dose, treatment format and the types of activities and skills targeted but provide little to no specificity on the behavioral techniques that are delivered and the extent to which behavioral techniques are emphasized relative to other activities.

There is a growing recognition that greater specificity of behavioral interventions is essential to the field (13). Specificity is needed in treatment delivery characteristics (e.g., mode, duration and intensity), adaptability (by whom), intervention strategies, and mechanisms of action. The latter two features have been addressed by Michie and colleagues, who have proposed using a taxonomy of well-defined behavior change techniques (BCTs) to describe interventions. A BCT is defined as an “observable, replicable, and irreducible component of an intervention designedto alter or redirect causal processes that regulate behavior; that is, a technique is proposed to be an ‘active ingredient’…” (14). The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy Version 1 (BCTTv1) includes 93 BCTs organized into 16 domains (14). Since its publication in 2013, literature reviews and syntheses have used the taxonomy to code BCTs from manuscripts reporting study outcomes (15). However, relying on manuscripts alone to code BCTs used in interventions likely results in a loss of information. For example, Lorencatto (2013) used smoking cessation interventions identified from Cochrane Reviews to compare the number of BCTs identified when intervention protocol and manuals of operations were used as compared with coding from published manuscripts. More than twice the number of BCTs were identified when coding from protocols and manuals compared to the published manuscripts (16).

The goal of the present study was to deconstruct the EARLY treatment arms using detailed descriptions of interventions, manuals of operations, and other materials provided by the study teams. Identifying BCTs used in EARLY is an important first step towards understanding the complexity of weight control interventions and how interventions differ in their approach to behavior change. As more studies identify the BCTs used in their interventions, our results will facilitate comparison with others in the literature and generate hypotheses regarding optimization.

This study also brings an innovation in intervention characterization by determining the relative emphasis of each BCT domain within each intervention. This is an important consideration as interventions may include the same techniques but emphasize them to varying degrees resulting in quite different treatment approaches. Consider two interventions with the same 4 BCTs - Self-monitoring of Behavior, Feedback on Behavior, Social Support-Unspecified, and Goal Setting (behavior). Intervention A is focused on social support from peer mentors and amongst group members through frequent in person meetings, meetups, and a robust social media platform. It also emphasizes building stronger ties to existing social support networks of family and friends to support behaviors. The other three self-regulatory BCTs are included in Intervention A, but are far less emphasized. For example, Self-Monitoring is encouraged throughout but Feedback is provided monthly and a goal setting exercise is only conducted at baseline. Intervention B, on the other hand, emphasizes the self-regulatory BCTs and is focused on daily Self-Monitoring, daily Feedback via mobile App on progress toward goals, and daily adaptive Goal Setting based on actual goal attainment. Intervention B uses the Social Support-Unspecified BCT by suggesting that participants post encouraging messages to each other on a messaging platform within the app. While including the same 4 BCTs, the utilization and emphasis within the interventions create quite different approaches. To date, these differences in emphasis and dose of BCTs has not been considered.

The present study used a novel approach to estimate the degree to which various techniques were ‘dominant’ or received greater emphasis across the 17 interventions delivered in EARLY. The approach was adapted from the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) study consortium, which successfully deconstructed interventions for caregivers of family members with Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia (17,18). To our knowledge, this is the first study to determine the relative emphasis of BCT domains.

Methods

Intervention Coding:

Each of the EARLY studies provided materials describing their interventions, including intervention descriptions, protocol, manuals of procedures, materials, and screen shots or logins for direct access to technology components. Four coders with at least Master’s level training in behavioral science were trained in BCTTv1 using the website (http://www.bct-taxonomy.com/) and app created by Michie and colleagues, as well as practice coding exercises. To develop coding plans, separate meetings were held with two of the initial taxonomy developers, Drs. Charles Abraham and Susan Michie.

Each treatment arm was coded independently by 2–3 raters. After coding, a consensus meeting was used to identify discrepancies, and additional documents were requested from the sites. Raters independently re-coded those BCTs for which there was disagreement. Following this second coding, structured interviews with study teams were completed to clarify questions and the coding team met to reach consensus. Following these interviews, the coded BCTs were sent to sites for their review and consensus. In every case, the study team indicated that additional BCTs should be coded and they were asked to provide documentation (e.g., lessons, podcasts, campaign documents) to demonstrate how the BCT was used. An average of 3.2 (range 0–12) BCTs were added to the coding following study team review. A domain was coded as present if an intervention included at least one BCT from the domain.

Analytical Hierarchy Process:

The Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) was employed to determine how much each domain was emphasized in each treatment arm relative to all other domains used. AHP is a process for analyzing complex decisions (19) using pairwise comparisons to determine relative emphasis or importance. For the present study, comparisons were made at the domain level rather than BCT level in order to manage the number of comparisons. There is a maximum of 120 pairwise comparisons for the 16 domains whereas comparing all 93 BCTs with each other would require 4278 pairwise comparisons. As an example of the comparison process, consider an intervention arm with BCTs in three domains of Goals and Planning, Feedback and Monitoring, and Social Support. Study teams were asked to judge the relative level of emphasis of each of the three domains compared to each of the other domains in their interventions, i.e., Goals and Planning compared to Feedback and Monitoring, then Goals and Planning compared to Social Support, and finally Feedback and Monitoring compared to Social Support. Study teams were trained on how to apply the AHP during a multi-day face-to-face meeting where REACH consortium members shared the REACH approach and provided training. Each study received the list of the domains and BCTs used in each of their study arms with examples of how they were employed in the intervention. Pairwise comparisons of the domains were made on an anchored scale where 1 indicated equal emphasis, and values 2 – 9 represent progressively divergent emphasis. Study team consensus was reached after independent scoring occurred. Results are presented as pie charts showing the percentage emphasis of each domain for each treatment arm.

Results

Interventions Overview

Table 1 includes a brief description of each of the treatment arms organized by intervention target: weight loss (WL); weight gain prevention (WGP); or weight management among special populations (SP). Table 1 also shows the variability of intervention dose and delivery methods as planned and the variability of average weight change after 12 months (2,4,6,7,20–22). For decomposition purposes, five arms were considered true controls hereafter called “controls”; the remaining 12 arms including active controls and intervention are called “interventions”. Five studies had true control arms comprising usual care related to weight control or general health information. In contrast, two studies used “active controls”; the IDEA study compared a standard behavioral weight loss intervention to an enhanced intervention and TARGIT included a quit-line smoking cessation intervention in their control. Both groups in TARGIT received nicotine replacement therapy. While most of the EARLY studies had main outcomes at 2 years, the 12 month data are available in the papers and reflected in Table 1 to correspond to the interventions described herein. The mean weight changes at 1 year range from +0.9 kg to −8.3 kg. Importantly, the range of weight change achieved is likely impacted by the actual interventions, including the BCTs used, intervention intensity, delivery modalities, and by participant characteristics. Little to no weight change was expected in the weight gain prevention trials. Treatment effects on weight change are detailed in each of the EARLY outcome papers (2,4,6,7,20–22).

Table 1:

Description of the EARLY Consortium Studies by Treatment Arm – 3 Weight Loss, 2 Weight Gain Prevention, 2 Special Population

| Deliver Modality and Dose | BCTs & Outcomes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Face-to-Face Sessions | Telephone Calls | SMS Text Messaging | Email Counseling or Feedback | Study Website, Podcast or App | Social Media | Total BCTs | 12 Months** Weight Change | ||

| Weight Loss Studies | |||||||||

| CITY | |||||||||

| Control (n=123) |

Information on healthy eating and physical activity from Eat Smart Move More NC program | 2 | −2.25 kg | ||||||

| Cell Phone Intervention (n=122) | Behavioral weight loss intervention delivered via study-specific Smartphone app focusing on weight, diet and activity; app used for self-monitoring, goal setting, challenges, social support and behavior prompts | ✓ | ✓ | 15 | −1.48 kg | ||||

| Personal Coaching Intervention (n=120) |

Behavioral weight loss intervention delivered via Face-Face and phone coaching focusing on weight, diet and activity using, goal setting, challenges, social support; Study-specific Smartphone used only for self-monitoring behaviors | 6 | 23 | ✓ | 24 | −3.58 kg | |||

| IDEA | |||||||||

| Standard Intervention (n=234) |

Behavioral weight loss intervention delivered Face- Face sessions and phone coaching, text message prompts focusing on weight, diet and activity; study- specific website used for self-monitoring | 42 | 17 | ✓ | ✓ | 27 | −8.3 kg | ||

| Enhanced Intervention (n=237) |

Behavioral weight loss intervention delivered via Face-Face sessions and phone coaching, text message prompts focusing on weight, diet and activity; wearable monitoring technology to assess activity and energy balance | 42 | 17 | ✓ | ✓ | 28 | −6.7 kg | ||

| SMART | |||||||||

| Control (n=202) |

Study-specific website with general health information | ✓ | 5 | +0.3 kg | |||||

| Intervention (n=202) |

Study-specific website, Facebook, text messaging, smartphone apps, phone and email coaching focusing on weight, diet and activity used for self-monitoring | 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 24 | −1.0 kg | |

| Weight Gain Prevention Studies | |||||||||

| CHOICES | |||||||||

| Control (n=217) |

Standard public health information on maintaining a healthy weight | 4 | +0.7 kg | ||||||

| Intervention (n=225) |

Online, Face-Face, and Hybrid Course focusing on eating, activity, sleep and stress management Study specific web-based social network |

16 | ✓ | ✓ | 31 | +0.9 kg | |||

| SNAP | |||||||||

| Control (n=201) |

Usual care weight gain prevention information with introduction to both Large and Small Change techniques | 1 | 10 | −0.48 kg | |||||

| Small Change Intervention (n=200) |

Behavioral weight gain prevention intervention delivered via Face-Face sessions, web, SMS and emails focusing on daily weighing, making daily small, 100-calorie changes to diet and activity | 14 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 32 | −1.19 kg | ||

| Large Change Intervention (n=201) |

Behavioral weight gain prevention intervention delivered via Face-Face sessions, web, SMS and emails focusing on daily weighing; emphasized initial weight loss of 5–10 pounds through diet and physical activity | 14 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 32 | −2.39 kg | ||

| Special Populations | |||||||||

| TARGIT | (Smoking Cessation/Weight Gain Prevention) | ||||||||

| Active Control (n=164) |

Smoking cessation delivered via tobacco quit line and study-specific website | 1 | ✓ | 39 | +0.85 | ||||

| Intervention (n=166) |

Smoking cessation delivered via tobacco quit line and study-specific website plus behavioral weight gain prevention intervention delivered via interactive technologies, including phone calls, apps, self-monitoring, and webinars | 13 | 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 45 | +0.78 | |

| eMOMs (Pregnancy and Post-Partum Weight Control) | |||||||||

| Pregnancy and Postpartum Control (n=563) |

Study-specific website focusing on general health information | ✓ | ✓ | n/a+ | |||||

| Pregnancy Intervention Only (n=563) |

Study-specific website focusing on health information during pregnancy, including goal setting and weight tracking | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | n/a+ | ||||

| Pregnancy and Postpartum Intervention (n=563) |

Study-specific website with general health information during pregnancy and postpartum, including goal setting and weight tracking | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | n/a+ | ||||

Numbers refer to the planned number of face-to-face sessions or phone calls. Check marks indicate that this method of delivery was planned, but not able to be enumerated.

Main outcome timepoint varied across studies. Outcomes at 12 months for all studies are available in published papers and reported in this table.

Due to the study outcomes being prevention of excessive gestational weight gain and post-partum weight control the timing of measures did not include corresponding 12 month weight outcome

With regard to dose, for delivery methods for which intended dose was the same for all participants, the number of intended intervention contacts is enumerated (Table 1). For delivery methods that varied by participant, checkmarks are used to indicate the method used for intervention delivery. In every study except eMOMS (10 arms), face-to-face sessions and/or telephone calls were included. The number of planned sessions for interventions using face-to-face delivery ranged from 1–42 while the number of planned phone calls ranged from 5–23. In keeping with the intent of EARLY to reach young adults through a variety of technological approaches, all of the studies used at least one type of technology. In 9 of the arms, SMS text messaging was used; 4 used email counseling or feedback; 14 used a study website, podcast or app; and 5 used social media. Importantly, the BCTs were delivered using different combinations of these technology and human delivered components.

Domains and BCTs used across the EARLY trials

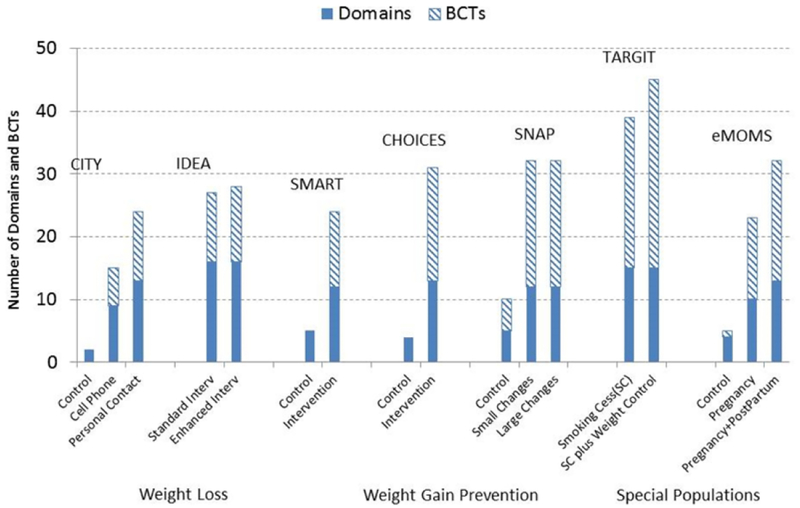

Figure 1 shows the number of domains and BCTs in each arm, organized by intervention target. The number of domains ranged from 2–16. The number of BCTs ranged from 2 to 45. Overall, control arms used fewer domains and BCTs as compared to intervention arms (Control average: Domain = 4, BCT =5.2; Intervention average: Domain =13, BCT = 29.3).

Figure 1:

Number of Domains and Behavior Change Techniques Used by EARLY Interventions

Table 2 shows the number of BCTs within domains and the specific BCTs that were used by arm and study target. The intervention arms used BCTs from all of the 16 domains while controls only used BCTs from 7 (44%). All of the intervention arms included BCTs from the 6 domains of Goals and Planning, Feedback and Monitoring, Social Support, Shaping Knowledge, Natural Consequences, and Comparison of Outcomes.

Table 2:

BCTs Usage by Number of Study Arms

| All Study Arms (n=17) |

Interventions Only By Type (n=12) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCT Domain | BCTs Used In EARLY | Controls (n=5) |

Interventions (n=12) |

Weight Loss (n=5) |

Weight Gain Prevention (n=3) |

Special Populations (n=4) |

| 1. Goals and Planning (Total BCTs in Domain 1: 9) |

1.1 Goal setting (behavior) | 1 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| 1.2 Problem solving | 0 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1.3 Goal setting (outcome) | 1 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1.4 Action planning | 1 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1.5 Review behavior goal(s) | 0 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1.6 Discrepancy between current behavior and goal | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| 1.7 Review outcome goals(s) | 0 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1.8 Behavioral Contract | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| 1.9 Commitment | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| 2. Feedback and monitoring (Total BCTs in Domain 2: 7) |

2.2 Feedback on behavior | 1 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| 2.3 Self-monitoring of behavior | 2 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 3 | |

| 2.4 Self-monitoring of outcome (s) of behavior | 1 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 3 | |

| 2.6 Biofeedback | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2.7 Feedback on outcomes (s) of behavior | 1 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 4 | |

| 3. Social support (Total BCTs Domain 3: 3) |

3.1 Social support (unspecified) | 1 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| 3.2 Social support (practical) | 1 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 4 | |

| 3.3 Social support (emotional) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 4. Shaping knowledge (Total BCTs Domain 4: 4) |

4.1 Instruction on how to perform a behavior | 5 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| 4.2 Information about antecedents | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| 5. Natural consequences (Total BCTs Domain 5: 6) |

5.1 Information about health consequences | 4 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 5.4 Monitoring of emotional consequences | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 5.6 Information about emotional consequences | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 6. Comparison of behavior (Total BCTs Domain 6: 3) |

6.1 Demonstration of the behavior | 1 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 6.2 Social comparison | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 7. Associations (Total BCTs Domain 7: 8) | 7.1 Prompts/cues | 0 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 8. Repetition and substitution (Total BCTs Domain 8: 7) |

8.1 Behavioral practice/rehearsal | 0 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 8.2 Behavior substitution | 0 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |

| 8.3 Habit formation | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 8.4 Habit reversal | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

| 9. Comparison of outcomes (Total BCTs Domain 9: 3) |

9.1 Credible Source | 5 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| 9.2 Pros and Cons | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 10. Reward and threat (Total BCTs Domain 10: 11) |

10.1 Material incentive (behavior) | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| 10.2 Material reward (behavior) | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | |

| 10.3 Non-specific reward | 0 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 10.4 Social reward | 0 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| 10.6 Non-specific incentive | 0 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 10.7 Self-incentive | 0 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| 10.8 Incentive (outcome) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| 10.9 Self-reward | 0 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| 10.10 Reward (outcome) | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| 11. Regulation (Total BCTs Domain 11: 4) |

11.1 Pharmacological support | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 11.2 Reduce negative emotions | 0 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| 12. Antecedents (Total BCTs Domain 12: 6) |

12.1 Restructuring the physical environment | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 12.2 Restructuring the social environment | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| 12.3 Avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behavior | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| 12.4 Distraction | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 12.5 Adding objects to the environment | 0 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| 12.6 Body changes | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 13. Identity (Total BCTs Domain 13: 5) |

13.1 Identification of self as role model | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| 13.2 Framing/reframing | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 13.4 Valued self-identity | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 14. Scheduled Consequences (Total BCTs Domain 14: 10) |

14.6 Situation-specific reward | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 14.8 Reward alternative behavior | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 15. Self-Belief (Total BCTs Domain 15: 4) |

15.1 Verbal persuasion about capability | 0 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| 15.4 Self-talk | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| 16. Covert Learning (Total BCTs Domain 16: 3) |

16.2 Imaginary reward | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Of the 93 possible BCTs, 36 (39%) were not used in any of the EARLY interventions. BCTs not used are shown in Table 3. The other 57 BCTs were used in at least one of the active interventions whereas the control arms used only 13 (14%) of the BCTs. Instruction on How to Perform a Behavior (from the Shaping Knowledge domain) and Credible Source (from the Comparison of Outcomes domain) were used in all 17 arms. Credible Source emerged because each study identified the research institution associated with their study as a credible source. Aside from these, the most frequently used BCT in controls was Information about Health Consequences (from the Natural Consequences domain).

Table 3:

Behavior Change Techniques (n=36) Not Used by Any EARLY Weight Management Intervention or Control

| 2.1 Monitoring of behavior by others without feedback 2.5 Monitoring of Outcome(s) of behavior by others without feedback |

|

| 4.3 Re-attribution 4.4 Behavioral Experiments |

10.5 Social incentive 10.11 Future punishment |

| 5.2 Salience of Consequences 5.5 Anticipated Regret |

11.3 Conserving mental resources 11.4 Paradoxical instructions |

| 6.3 Information about others’ approval | 13.3 Incompatible beliefs 13.5 Identity associated with changed behavior |

| 7.2 Cue Signaling Reward 7.3 Reduce prompts/cues 7.4 Remove access to the reward 7.5 Remove aversive stimulus 7.6 Satiation 7.7 Exposure 7.8 Associative learning |

14.1 Behavior cost 14.2 Punishment 14.3 Remove reward 14.4 Reward approximation 14.5 Rewarding completion 14.7 Reward incompatible behavior 14.9 Reduce reward frequency 14.10Remove punishment |

| 8.5 Overcorrection 8.6 Generalization of a target behavior 8.7 Graded Tasks |

15.2 Mental rehearsal of successful performance 15.3 Focus on past success |

| 9.3 Comparative imagining of future outcomes | 16.1 Imaginary punishment 16.3 Vicarious consequences |

Note: All BCTs on Domains 1, 3, and 12 were used in the EARLY trials

The 15 most commonly used BCTs were used in almost all interventions (11 of 12). From the Goals and Planning domain these BCTs are Goal Setting (behavior), Problem Solving, Goal Setting (outcome), Action Planning, Review Behavior Goals, and Review Outcome Goals. From the Feedback and Monitoring domain: Feedback on Behavior, Self-monitoring of Behavior, Self-monitoring of Outcomes of Behavior, and Feedback on Outcomes of Behavior. Other BCTs that were used by at least 11 arms are Social Support-Unspecified (Social Support domain), Instructions on How to Perform a Behavior (Shaping Knowledge domain), Information on Health Consequences (Natural Consequences domain), Prompts and Cues (Associations domain), and Credible Source (Comparison of Outcomes domain).

Table 2 also shows the BCTs used according to intervention target. SP interventions used 49 of the BCTs (88%), while the WGP and WL interventions used 39 (68%) and 38 (67%) of the BCTs, respectively. While most (n=45) of the BCTs were used sporadically across all intervention sub-types, some BCTs were unique to WL studies while others were used in only WGP or SP studies. Seven BCTs were used only by the SP interventions: Social Support-Emotional (Social Support domain); Pharmacological Support (Regulation domain); Restructuring the Social Environment, Avoidance/Reducing Exposure to Cues for the Behavior, Distraction, and Body Changes (Antecedents domain); and Framing and Reframing (Identity domain). The 4 BCTS used only in the WL interventions are Biofeedback (Feedback and Monitoring domain); Valued Self-Identity (Identity domain); Situation Specific Rewards and Reward Alternate Behavior (Scheduled Consequences domain). Information about Social and Environmental Consequences (Natural Consequences domain) was used solely by the WGP interventions.

Frequency of BCT Use

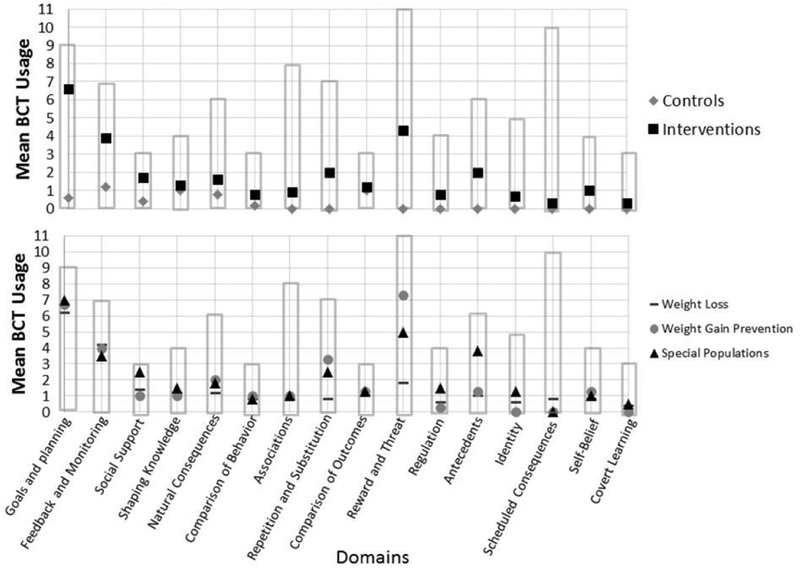

The top of Figure 2 shows the average usage of each BCT by arm – controls vs. interventions. The bars for each domain show the number of individual BCTs in that domain. Intervention arms used, on average, more BCTs per domain compared to control arms. The biggest differences in the average number of BCTs between control and intervention arms occurred for Goals and Planning (mean 6.6 I vs 0.6 C) and Reward and Threat (mean 4.3 I vs 0 C). Importantly, Figure 2 also illustrates the relatively small average number of BCTs used within some domains in the intervention arms. On average, most interventions used fewer than 50% of the available BCTs within a domain; at least 50% of the potential BCTs within a domain were used in only three domains (Goals and Planning (73%); Feedback and Monitoring 56%); and Social Support (56%).

Figure 2:

Average BCT Usage per Domain by EARLY Interventions

The bottom half of Figure 2 shows differences in the average use of BCTs per domain by intervention target. While the average number of BCTs used was fairly consistent by intervention target, differences in mean number used are evident for Social Support, Repetition and Substitution, Reward and Threat, and Antecedents. The WGP interventions used, on average, more BCTs from Repetition and Substitution and Reward and Threat compared to the other intervention types while the SP interventions used more BCTs from the Social Support and Antecedents domains.

Relative Emphasis or Importance of Domains

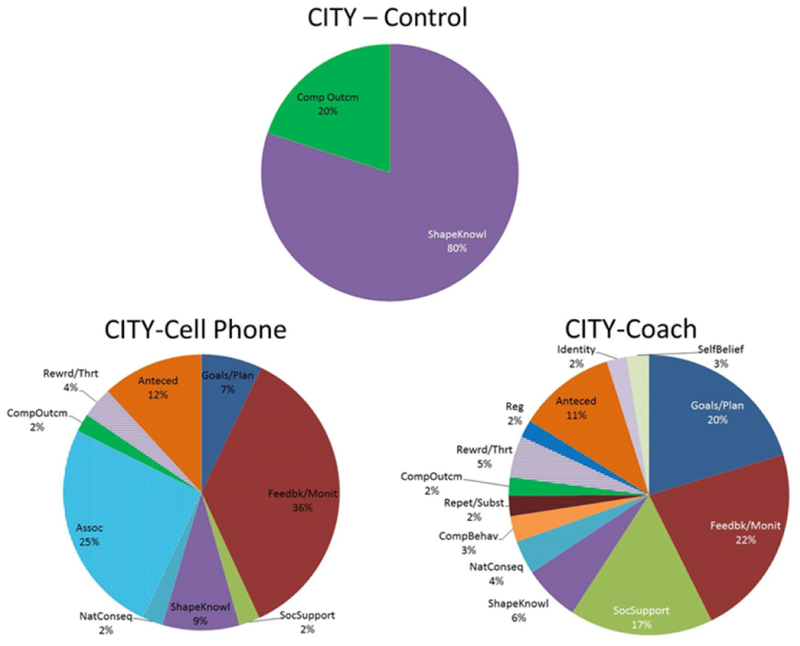

Figure 3 shows the AHP results using pie charts to show relative domain emphasis using one study, CITY’s two interventions and one control arm, as an example. The CITY control used only two domains (Shaping Knowledge and Comparison of Outcomes) and 80% of the emphasis in the control group was on Shaping Knowledge. The CITY cell phone intervention used BCTs from nine domains with more than half of the emphasis occurring from BCTs from the Feedback and Monitoring (36%) and the Associations (25%) domains. The CITY personal coaching intervention included BCTs from 13 domains with more than half of the emphasis from BCTs from Goals and Planning (20%), Feedback and Monitoring (22%), and Social Support (17%). Thus, differences in personal coaching and cell phone were more than delivery modality and technology vs. coach; emphasis on BCT domains differed as well. The AHP results for all other studies are available as Supplementary File S1. Supporting Information.

Figure 3:

CITY AHP Results

Table 4 shows the most emphasized domains for intervention vs. control arms and by intervention type. The most emphasized domains were similar for WL and WGP trials. Feedback and Monitoring and Goals and Planning were ranked in the top four domains by emphasis for all 8 of the active interventions and 7/8 of the active interventions targeting WL or WGP, respectively. Social Support, Shaping Knowledge, Antecedents, and Comparison of Behavior were the next most commonly emphasized domains for the WL and WGP interventions. While the exact pattern of emphasis of domains used in the interventions targeting special populations differed, Feedback and Monitoring or Goals and Planning were most emphasized in three of the four interventions targeting other outcomes. Other top domains were Antecedents in smoking cessation and Associations in the pregnancy study. The fourth most emphasized domain among interventions with other special populations was Social Support.

Table 4:

Top Domains by Intervention Type from AHP analysis

| # Domains | Most Emphasized | 2nd Most Emphasized | 3rd Most Emphasized | 4th Most Emphasized* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions | Weight Loss | |||||

| CITY Cell Phone | 9 | Feedback Monitoring | Association | Antecedents | ||

| CITY Personal Coach | 13 | Feedback Monitoring | Goals Planning | Social Support | Antecedents | |

| IDEA Standard | 16 | Feedback Monitoring | Goals Planning | Shaping Knowledge | Comparison Behavior | |

| IDEA Enhanced | 16 | Feedback Monitoring | Goals Planning | Shaping Knowledge | Comparison Behavior | |

| SMART Intervention | 12 | Feedback Monitoring | Goals Planning | Social Support | Reward Threat | |

| Weight Gain Prevention | ||||||

| Choices Intervention | 13 | Feedback Monitoring | Goals Planning | Social Support | Rewards Threat | |

| SNAP Small Changes | 12 | Feedback Monitoring | Goals Planning | Repetition Substitution | ||

| SNAP Large Changes | 12 | Feedback Monitoring | Goals Planning | Repetition Substitution | ||

| Special Populations | ||||||

| Targit Active Control | 15 | Goals Planning | Antecedents | Repetition Substitution | Social Support | |

| Targit Intervention | 15 | Antecedents | Goals Planning | Feedback Monitoring | Social Support | |

| eMOMs Pregnancy | 10 | Feedback Monitoring | Goals Planning | Association | Social Support | |

| eMOMs Pregnancy Post-Partum | 13 | Goals Planning | Feedback Monitoring | Association | Social Support | |

| Controls | Choices Control | 4 | Feedback Monitoring | Natural Consequences | Shaping Knowledge | |

| CITY Control | 2 | Shaping Knowledge | Comparison Outcomes | |||

| SMART Control | 5 | Shaping Knowledge | Natural Consequences | Comparison Outcomes | ||

| SNAP Control | 5 | Feedback Monitoring | Goals Planning | Shaping Knowledge | ||

| eMOMs Control | 4 | Social Support | Natural Consequences | Comparison Outcome | ||

Note to be included domain must comprise at least 10% of total intervention

Discussion

The EARLY trials provide a unique opportunity to increase understanding the behavioral strategies used in weight-related interventions. While all of the studies targeted young adults, their approaches varied from intensive face-to-face interventions to entirely technology-based approaches, and the study arms varied in the BCTs they used. Considering the most commonly used 6 domains and 15 BCTs, a “common EARLY intervention” emerges. Participants in EARLY were encouraged to self-monitor their behavior and were provided with feedback on their behaviors and how they were working in terms of outcome (weight). They were instructed on how to perform behaviors, given information about health consequences of obesity, provided with social support by the program and/or from other participants, and prompted (primarily through the use of technology) to continue working toward their goals. They were taught about cues in their environment or cued via text message or app and encouraged to set goals (both behavioral and weight goals) with more specific action planning and problem solving when needed. While this common set of 15 BCTs was used across the active interventions, the delivery methods and the dose of the interventions varied, as well as the additional BCTs that were used by specific interventions. On average, an additional unique set of 14 BCTs were used in each study.

The fact that interventions averaged 13 domains and 29 BCTs suggests that the interventions were complex. McSharry et al. examined published physical activity interventions among participants with obesity that targeted either multiple behaviors (e.g. exercise and diet) or a single behavior (e.g. exercise alone). A greater number of techniques, 11 vs. 8, were used to change multiple behaviors vs. a single behavior, respectively (23). While all of the EARLY interventions had primary behavioral targets of diet, physical activity and self-weighing, some also targeted sleep, sedentary behavior, and smoking. The average of 29 techniques in EARLY was almost triple the 11 BCTs found in the McSharry study of diet and exercise interventions (23). It is possible that the EARLY interventions used more techniques because of the additional behavioral targets or based on their duration. Longer interventions may introduce additional techniques over time to provide new content or develop new skills. However, it is also possible that coding the intervention manuals and study materials resulted in a more in-depth understanding of the interventions and more techniques to be captured. It is also likely that the large array of techniques included is an attempt to provide exposure to skills and techniques that might only be useful for subsets of participants. Regardless of rationale, an intervention that uses 29 BCTs is complex and might be difficult to implement broadly or translate for dissemination to other settings. Future work is needed to determine whether a more parsimonious set of techniques might be as effective and more easily disseminated.

While BCTs from all 16 domains were used across the 12 intervention arms, 36 of the 93 BCTs identified in the Michie taxonomy were never used by any of the EARLY intervention arms. While it is not expected that interventions targeting obesity would use all BCTs as the taxonomy was compiled across many behavioral medicine topic areas, it is instructive to examine those BCTs not used as they might offer other applicable techniques to consider in developing future weight management interventions. For example, EARLY studies used BCTs from the Self-Belief domain such as Verbal Persuasion about Capability likely in an effort to promote or preserve self-efficacy. However another technique on the Self-Belief domain (Focus on Past Success) might have been very useful toward this goal. Examination of Table 3 also shows that many of the BCTs from two domains, Assocations and Scheduled Consequences, were not used. This is perhaps surprising since theoreteical underpinnings of obesity point to the environment and associative learning for many eating and activity habits. BCTs from these two specific domains are derived from operant and classical conditioning which are very applicable to WL and WGP. Thus, thoughtful examination of the full complement of techniques may help insure sufficient coverage of techniques to target key constructs during intervention design.

Only three of the 16 domains (Goals and Planning, Feedback and Monitoring, and Social Support) had an average of at least half of the BCTs within the domain used by the interventions suggesting that the EARLY trials emphasized breadth across domains over depth within domains. However, since these three domains emerged from the AHP as the domains most emphasized, it makes sense that more BCTs from within these domains were used. During intervention development, designers should pay attention to the domains they believe are most important and consider using more BCTs from those domains.

Differences in the use of BCTs were observed across the three targets of interventions tested in EARLY. Interventions targeting Special Populations tended to include more BCTs than Weight Loss or Weight Gain Prevention interventions, and may be the result of attempting to simultaneously change multiple behaviors (i.e. diet, exercise, and smoking). Some BCTs used were unique to the smoking cessation interventions. For example, discussion of pharmacological support, avoidance of exposure cues, framing and reframing, were used in both TARGIT arms. Both SP studies also used more BCTs from the Social Support domains, likely due to the belief that during these times (smoking cessation, and pregnancy/post-partum) social support may be particularly important for behavior change. Likewise, the WGP interventions used more BCTs from Repetition and Substitution and Reward and Threat compared to the others, possibly building in more rewards for behavioral progress because weight gain prevention lacks the natural rewards of weight loss. The differences in BCTs used across intervention type may reflect the perceived need to tailor intervention strategies based on the population of interest and specific nuances of the behaviors targeted. It may also highlight the BCTs that are being under-or over-utilized by some types of interventions. As an example, targeting BCTs from the Repetition and Substitution Domain may deserve greater emphasis in WL interventions.

To date, the literature on BCTs has focused on the presence or absence of the BCTs, not on how much they are emphasized relative to other techniques within an intervention. The use of the AHP process in this study allows the deconstruction to take into account the relative emphasis the BCT domains contribute to an intervention. Among WL and WGP interventions, Feedback and Monitoring and Goals and Planning domains were the most emphasized relative to other domains with remarkable consistency and, perhaps because of their perceived importance, more BCTs from these domains were included. The BCTs used in these two domains are consistent with control theory (24). This is encouraging given that a review of diet and activity interventions coded from an earlier version of the Michie taxonomy showed that interventions including control theory BCTs were associated with larger effects (25).

The AHP in EARLY was performed after the interventions were developed and being delivered, however, future utilization of the approach at the earliest stages of intervention development may allow developers to ensure that for domains they perceive important, careful consideration is given to the BCTs within that domain so a sufficient dose has been planned. Future work will report on findings of the use of the AHP process to compare the relative emphasis of individual BCTs and dose of BCTs received to weight change; this research was beyond the scope of this manuscript.

This study has numerous strengths including analysis across 17 treatment arms in seven unique weight control interventions and the use of a well-established taxonomy to describe the content of the interventions. The deconstruction process coded for content using manuals of operations and intervention materials rather than published manuscripts. The final coding was derived from consensus with intervention developers to affirm the accuracy of the coding, and the novel use of the AHP considers the emphasis of domains relative to others. However, the study also has important limitations, including the fact that coding was based on the interventions as planned rather than as delivered. Prior studies have shown that interventions often deliver fewer techniques than are planned (26,27).

Conclusion

This research represents a unique attempt to deconstruct 17 large and complex weight management interventions using a taxonomy of behavior change techniques. Though we found a common set of domains and techniques were emphasized across WL and WGP interventions, these interventions tended to be complex including 29 techniques. Beyond identifying BCTs, the use of the AHP identified domains whose BCTs were most emphasized by the interventions and include Feedback and Monitoring, Goals and Planning and Social Support. These methods and results add to reproducibility and rigor and suggest testable hypotheses for optimization of weight related interventions.

Supplementary Material

Study Importance.

What is already known about this subject?

Weight management interventions are complex and involve many components.

Most study designs do not permit for determination of essential intervention components.

Obesity studies that have examined the Behavior Change Techniques (BCTTv1) to date, have coded from published manuscripts, not from detailed material provided by the investigators.

What does your study add?

To allow comparison of interventions, we examine similarities and differences in what, how, and how much techniques were delivered across seven weight management trials.

We used the Behavior Change Techniques (BCTTv1) taxonomy to code the 17 EARLY treatment arms using manuals plus intervention team involvement and report BCTs used, and the domains in which they are found, separately for active and control arms, and by study target (e.g., weight loss, weight gain prevention and weight management in special populations).

We utilized the Analytical Hierarchy Process to determine the relative emphasis of domains and summarized our findings across the trials. Notably, this allowed comparisons of the importance and amount of emphasis of the BCT domains across different treatment arms characterized by active/control and study target.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Susan Michie and Dr. William Riley for input on the study design, the coding assistance of Sarah Mye, MPH and Lara Balian, MPH, and interventionists who assisted with AHP ratings including Stacey Moe, Meredith Graham, and Kelliann Davis, Ph.D.

Funding: Funding for this work comes from a research grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute HL122144 (Tate and Belle), HL096760–02 (Fernandez and Olson), HL096770–01 (Jakicic), HL096628–01 (Johnson), HL096767–01 (Lytle), HL096715–01 (Patrick), HL096720–01 (Svetkey), HL090864 (Wing), and HL090875 (Espeland).

Footnotes

Disclosure: Drs. Tate and Jakicic report being members of the Scientific Advisory Board for Weight Watcher’s International. The other authors have no Conflicts of Interest to report.

Clinical Trial Registration:

All of the trials are registered as clinical trials: (CHOICES), (CITY), (e-MomsRoc), (IDEA), (SMART), (SNAP), and (TARGIT).

References

- 1.Lytle LA, Svetkey LP, Patrick K, et al. The EARLY trials: a consortium of studies targeting weight control in young adults. Transl Behav Med. 2014;4(3):304–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jakicic JM, Davis KK, Rogers RJ, et al. Effect of Wearable Technology Combined With a Lifestyle Intervention on Long-term Weight Loss: The IDEA Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. 2016;316(11):1161–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin PH, Intille S, Bennett G, et al. Adaptive intervention design in mobile health: Intervention design and development in the Cell Phone Intervention for You trial. Clin Trials. 2015;12(6):634–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godino JG, Merchant G, Norman GJ, et al. Using social and mobile tools for weight loss in overweight and obese young adults (Project SMART): a 2 year, parallel-group, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(9):747–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wing RR, Tate D, Espeland M, et al. Weight gain prevention in young adults: design of the study of novel approaches to weight gain prevention (SNAP) randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lytle LA, Laska MN, Linde JA, et al. Weight-Gain Reduction Among 2-Year College Students: The CHOICES RCT. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(2):183–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson KC, Thomas F, Richey P, et al. The Primary Results of the Treating Adult Smokers at Risk for Weight Gain with Interactive Technology (TARGIT) Study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(10):1691–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez ID, Groth SW, Reschke JE, Graham ML, Strawderman M, Olson CM. eMoms: Electronically-mediated weight interventions for pregnant and postpartum women. Study design and baseline characteristics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;43:63–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(12):2165–2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diabetes Prevention Program Research G. Reduction in the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes with Lifestyle Intervention or Metformin. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(6):393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan DH, Espeland MA, Foster GD, et al. Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24(5):610–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wing RR. Long-term effects of a lifestyle intervention on weight and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: four-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(17):1566–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulz R, Czaja SJ, McKay JR, Ory MG, Belle SH. Intervention taxonomy (ITAX): describing essential features of interventions. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34(6):811–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prestwich A, Sniehotta FF, Whittington C, Dombrowski SU, Rogers L, Michie S. Does theory influence the effectiveness of health behavior interventions? Meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2014;33(5):465–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorencatto F, West R, Seymour N, Michie S. Developing a method for specifying the components of behavior change interventions in practice: the example of smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(3):528–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Czaja SJ, Schulz R, Lee CC, Belle SH. A methodology for describing and decomposing complex psychosocial and behavioral interventions. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(3):385–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wisniewski SR, Belle SH, Coon DW, et al. The Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH): project design and baseline characteristics. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(3):375–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saaty TL. The analytic hierarchy process: planning, priority setting, resource allocation 1980.

- 20.Wing RR, Tate DF, Espeland MA, et al. Innovative Self-Regulation Strategies to Reduce Weight Gain in Young Adults: The Study of Novel Approaches to Weight Gain Prevention (SNAP) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(6):755–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Svetkey LP, Batch BC, Lin PH, et al. Cell phone intervention for you (CITY): A randomized, controlled trial of behavioral weight loss intervention for young adults using mobile technology. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(11):2133–2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olson CM, Groth SW, Graham ML, Reschke JE, Strawderman MS, Fernandez ID. The effectiveness of an online intervention in preventing excessive gestational weight gain: the emoms roc randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mc Sharry J, Olander EK, French DP. Do single and multiple behavior change interventions contain different behavior change techniques? A comparison of interventions targeting physical activity in obese populations. Health Psychol. 2015;34(9):960–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardner B, Whittington C, McAteer J, Eccles MP, Michie S. Using theory to synthesise evidence from behaviour change interventions: the example of audit and feedback. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(10):1618–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michie S, Ashford S, Sniehotta FF, Dombrowski SU, Bishop A, French DP. A refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: the CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychol Health. 2011;26(11):1479–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorencatto F, West R, Bruguera C, Michie S. A method for assessing fidelity of delivery of telephone behavioral support for smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(3):482–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. NHLBI and the NIH Office of Disease Prevention Working Group On Obesity Intervention Taxonomy and Pooled Analysis Working Group Meeting. 2013; August 29–30, 2013 Executive Summary. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/events/2013/combining-data-clinical-trials-obesity, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.