Dhpr regulates mitochondrial morphology by modulating S-nitrosylation of Drp1.

Abstract

Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles. Through a large-scale in vivo RNA interference (RNAi) screen that covered around a quarter of the Drosophila melanogaster genes (4000 genes), we identified 578 genes whose knockdown led to aberrant shapes or distributions of mitochondria. The complex analysis revealed that knockdown of the subunits of proteasomes, spliceosomes, and the electron transport chain complexes could severely affect mitochondrial morphology. The loss of Dhpr, a gene encoding an enzyme catalyzing tetrahydrobiopterin regeneration, leads to a reduction in the numbers of tyrosine hydroxylase neurons, shorter lifespan, and gradual loss of muscle integrity and climbing ability. The affected mitochondria in Dhpr mutants are swollen and have fewer cristae, probably due to lower levels of Drp1 S-nitrosylation. Overexpression of Drp1, but not of S-nitrosylation–defective Drp1, rescued Dhpr RNAi-induced mitochondrial defects. We propose that Dhpr regulates mitochondrial morphology and tissue homeostasis by modulating S-nitrosylation of Drp1.

INTRODUCTION

Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles participating in energy production, metabolism, and apoptosis (1). The fusion, fission, transport, and degradation of mitochondria shape their morphology and further affect their function. Mitochondrial morphology changes have been observed in many disease conditions, such as neurodegenerative diseases (2).

Many key molecules that regulate mitochondrial fusion, fission, transport, and mitophagy were identified (1). Three large guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases), MFN1/2, and OPA1 are required for the fusion of the mitochondrial outer and inner membrane (1). In addition, MitoPLD, a member of the phospholipase D (PLD) superfamily, and Miga1/2 (3), proteins with unknown functional domains, anchor to the outer mitochondrial membrane and participate in the fusion process. The loss of these proteins led to the fragmentation of mitochondria. In mammalian cells, OPA1 activity is regulated through proteolytic cleavage by inner membrane proteases Yme1L and Oma1. The presence of the long and short forms of OPA1 is required for proper fusion of the inner membrane of mitochondria. The fission of mitochondria is mediated by a dynamin-like large GTPase, Drp1. Drp1 is recruited by receptor proteins such as Mff, Fis1, MiD49, and MiD50 to the fission sites marked by the mitochondrial endoplasmic reticulum (ER) contacts. The activity of Drp1 could be modulated by phosphorylation, S-nitrosylation, SUMOylation, and O-linked N-acetylglucosamine glycosylation. Mitochondria are actively transported along the microtubules inside cells. The motor proteins such as kinesin and dynein mediate the anterograde and retrograde transport. Interactions between Miro proteins and Milton proteins serve as adaptors to link kinesin to the mitochondria. In neurons, syntaphilin anchors axonal mitochondria to microtubules and regulates axonal mitochondrial transport together with Miro and Milton. The degradation of mitochondria is mediated by mitophagy (4). The proteins encoded by the Parkinson’s disease (PD)–related genes Pink1 and Parkin sense the mitochondrial damage, mark the damaged mitochondria, and mediate their degradation by the autophagy pathway. In flies, the loss of Pink1 and park (fly ortholog of Parkin) led to a marked change in mitochondrial morphology in multiple tissues. The mitochondria became swollen and exhibited loss of the cristae. In mammals, Nix serves as a mitophagy receptor during red blood cell maturation. FUNDC1 is another mitophagy receptor that functions in hypoxia-mediated mitophagy.

It has been shown that mitochondrial morphology changes are highly associated with their metabolic status (5). However, a systematic analysis of the factors required for mitochondrial morphology maintenance under in vivo conditions is still lacking. To understand the regulatory network of the mitochondrial morphology, we performed a systematic screen using the RNA interference (RNAi) strategy in fly fat body tissues. The fly fat body is a tissue that resembles liver and adipose tissues in human. This tissue is a great model system to study cellular organelles because it has single-layered cells, and the cell size is large. The mitochondrial morphology in fat body is stereotyped and shows very little change between different experiments. In addition, the mitochondrial morphology did not change significantly in the fat bodies from early third-instar (82 hours after egg laying) to mid–third-instar larvae (96 hours after egg laying; fig. S2, A to D). Therefore, even if there is a slight developmental delay, it will not significantly affect mitochondrial morphology. Using this in vivo system, we screened 4146 RNAi lines (6) corresponding to 4221 genes (a few RNAi lines target common regions shared by multiple genes) and identified 578 genes required for proper mitochondrial morphology maintenance. We further carried out a complex analysis and established a network that regulates mitochondrial morphology. In addition, we demonstrated that dihydropteridine reductase (Dhpr) played critical roles in maintaining mitochondrial morphology by regulating the modification of Drp1. Our study not only serves as a rich source of information to study mitochondrial morphology but also sheds light on the molecular mechanisms underlying the diseases caused by the loss of Dhpr-related genes.

RESULTS

Mitochondrial morphology screen in fly fat body tissues

To systematically identify genes essential for the maintenance of mitochondrial morphology, we conducted a large-scale RNAi screen covering about 25% of the fly genes in the fly fat body tissues. We knocked down gene expression by driving UAS-dsRNA or UAS-shRNA expression in the fat body with Cg-Gal4, a fat body expressing Gal4, and marked the mitochondria with mitoGFP. The dissected early third-instar larvae fat bodies were fixed, and the mitochondrial morphology was examined using confocal microscopy by experienced researchers in a double-blind manner (Fig. 1A).

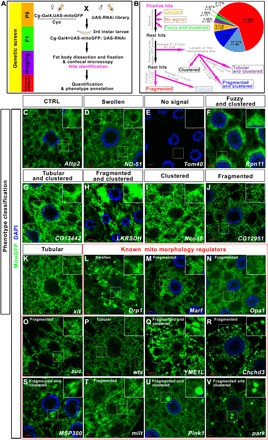

Fig. 1. Screen strategy and the classification of typical phenotypes.

(A) Diagram to show the screen strategy. (B) Diagram to show how different phenotypes were categorized. L, length; D, diameter. (C to K) The typical mitochondrial morphologies in fat body tissues were shown for each phenotype category. (L to V) Genes that were reported to regulate mitochondrial morphology were identified in this screen. The mitochondrial morphology in the fat body cells with the indicated gene knockdown is shown. Scale bars, 5 μm. Green signals were mitoGFP signals to indicate the mitochondrial morphology. Blue signals were nuclear 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. The boxed region in each image was enlarged in the inset to show the typical mitochondrial morphology. The phenotype category for each genotype was listed on the top of the image.

In total, we screened 4146 RNAi lines from the TRiP (Transgenic RNAi Project) collection (6) (table S1), which corresponded to 4221 individual genes. We found that 598 lines targeting 578 genes caused aberrant mitochondrial morphology (table S2). Then, the images of the positive hits were examined and categorized by two independent researchers in a double-blind manner (Fig. 1B). Hits with the following characteristics were categorized without further measurements: (i) The ones with mitochondria that showed apparent enlarged bubble-like shape were categorized as “Swollen” (5.71%, n = 33; Fig. 1, B and D, and table S2), (ii) the one hit that showed almost no green fluorescent protein (GFP) signal was categorized as “No signal” (0.17%, n = 1; Fig. 1, B and E, and table S2), and (iii) the ones with fuzzy mitochondria that clustered together and the outline of individual mitochondria that cannot be distinguished were categorized as “Fuzzy and clustered” (1.90%, n = 11; Fig. 1, B and F, and table S2). The rest of hits with large fluorescence patches or puncta were picked out, and the diameters of the largest patches or puncta from at least three independent images for each genotype were measured. The ones with average diameter larger than 2 μm (about five times of the average diameter of the mitochondrion in the wild-type fat body tissues) were singled out. For these hits, there were distinguishable mitochondria outside of the large fluorescence patches or puncta. We then selected an area of 64 μm2 outside of the patches and measured the length of the mitochondria. If the average mitochondrial length in these tissues was longer than that in the wild type (about 2 μm), these hits were categorized as “Tubular and clustered” (3.46%, n = 20; Fig. 1, B and G, and table S2). If the average mitochondrial length in these tissues was shorter than that in the wild type, these hits were categorized as “Fragmented and clustered” (11.94%, n = 69; Fig. 1, B and H, and table S2). If the average mitochondrial length in these tissues was comparable to that in the wild type, these hits were categorized as “Clustered” (0.87%, n = 5; Fig. 1, B and I, and table S2). For the hits that do not belong to above categories, an area of 64 μm2 was selected randomly (avoid nuclear region) and the length of mitochondria was measured. If the average mitochondrial length in these tissues was shorter than that in the wild type (L < 2 μm, P < 0.05), the hits were categorized as “Fragmented” (61.25%, n = 354; Fig. 1, B and J, and table S2). If the average mitochondrial length in these tissues was longer than that in the wild type (L > 2 μm, P < 0.05), the hits were categorized as “Tubular” (14.71%, n = 85; Fig. 1, B and K, and table S2).

Several genes necessary for controlling mitochondrial morphology were identified in our screen, suggesting that our screen strategy is reliable (Fig. 1, L to V). Some identified genes encode the core machinery regulating mitochondrial fission or fusion, such as Drp1 (7), Marf (fly ortholog of MFN1/2) (8), Opa1 (9), and zuc (fly ortholog of MitoPLD) (10). In our screen, knockdown of Drp1 (Fig. 1L) led to swollen mitochondria, and RNAi of Marf (Fig. 1M), Opa1 (Fig. 1N), and zuc (Fig. 1O) resulted in fragmented mitochondria. Some identified genes indirectly regulated mitochondrial fusion and fission by modulating the transcription or modification of the core fusion-fission machinery. It has been reported that activation of Yorkie (Yki) causes transcriptional up-regulation of genes that regulate mitochondrial fusion, such as Opa1 and Marf (11). In our screen, we found that when warts (wts) (Fig. 1P), a gene that encodes the terminal kinase that phosphorylates and inhibits Yki, was knocked down in fat body tissues, a majority of the mitochondria became tubular. We also identified the YME1L gene, whose mammalian ortholog encodes a protease that involves proteolytic processing of OPA1 (12). In our screen, the reduction of YME1L led to fragmented and clustered mitochondria (Fig. 1Q). In addition to the genes required for proper mitochondrial fusion and fission, we identified genes required for cristae organization (Chchd3) (Fig. 1R) (13), mitochondria positioning (MSP300) (Fig. 1S) (14), mitochondria transport (milt) (Fig. 1T) (15), and mitophagy (Pink1 and park) (Fig. 1, U and V) (16). All of these genes were reported to be required for maintaining mitochondrial morphology through different means, suggesting that our screen could recover genes that regulate mitochondrial morphology by different pathways.

Several RNAi screens that have used the same collection of RNAi lines suggested that the off-target rates of this collection were low. Among 578 genes identified, the RNAi lines corresponding to 562 genes were predicted to have no off-target (17). Twenty-three genes turned out to have more than one independent short hairpin–mediated RNAi (shRNAi) lines. For 17 genes, the independent RNAi lines targeting a single gene produced progenies with similar phenotypes when they were crossed with Cg-Gal4 flies (table S3). To further validate the fidelity of the screen, we obtained independent RNAi lines for another 130 hits and performed the same experiments, and the phenotypes were confirmed for 121 genes, suggesting again that our datasets are reliable (table S3).

Mitochondrial morphology regulatory networks

To understand the regulatory network of mitochondrial morphology, we used the online software COMPLEAT and the KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway analysis to identify the protein complexes (18). Combined with manual data mining, we generated a gene-protein interaction network for the genes identified in this screen (fig. S1).

In total, we identified 312 protein complexes required for mitochondrial morphology maintenance (table S4). The major complexes identified were those participating in processes such as mitochondria respiration and metabolism, RNA splicing, and proteolysis (table S5).

In addition to the molecules such as Drp1, Marf, OPA1, and Zuc that are directly involved in mitochondrial fission and fusion, we also identified multiple molecules that encode subunits of the electron transport chain (ETC) complexes or components required for the assembly of the mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes (table S5). In total, we identified 16 subunits of mitochondrial complex I, two proteins that are required for complex I assembly, one subunit of complex II, two subunits of complex III, one subunit of complex IV, two factors required for complex IV assembly, and five subunits of complex V. We also identified an enzyme cytochrome c heme lyase (Cchl) that is involved in the synthesis of cytochrome c, a soluble electron carrier that functions in electron transport between complexes III and IV (table S5) (19). The reduction of the expression of many of these proteins often led to severe swollen mitochondria (Fig. 2, A to J). The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis of the fat body tissues showed enlarged mitochondria with few cristae (Fig. 2, M to P, R, and S). We found that the knockdown of CTPsyn, a gene encoding cytidine triphosphate (CTP) synthase (20), led to a swollen mitochondrial phenotype that was very similar to the phenotype observed in the tissues with a reduction in respiration chain complex components (Fig. 2, K and Q to S). Two independent RNAi lines were used to confirm the phenotypes (Fig. 2, K and L). We detected the reduction in adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) level (Fig. 2T) and the increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (Fig. 2, U to X) when CTPsyn expression was reduced, suggesting that CTPsyn might regulate mitochondrial morphology via regulation of ETC activities.

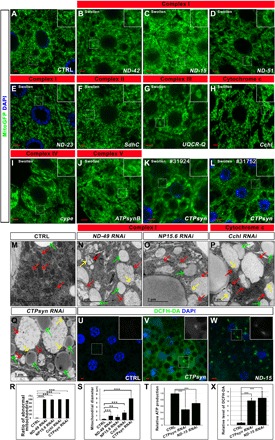

Fig. 2. The reduction of the expression of genes encoding ETC components leads to mitochondrial morphology defects.

(A) Control (CTRL). (B to J) The decrease of the ETC components led to swollen mitochondria. (K and L) The knockdown of CTPsyn by two independent RNAi lines led to a similar mitochondrial phenotype. Scale bars, 5 μm. Green signals were mitoGFP signals to indicate the mitochondrial morphology. Blue signals were nuclear DAPI staining. The boxed region in each image was enlarged and shown in the inset to present the typical mitochondrial morphology. The phenotype category for each genotype is listed on the top of the image. (M to Q) The TEM images of the fat body tissues in the animals with indicated genotypes. The swollen mitochondria (red arrows) in the RNAi tissues were identified by the remaining cristae (yellow arrows). The green arrows indicate the lipid droplets in the fat body tissues. (R) Quantification of the ratio of abnormal mitochondria (mitochondria with less cristae) in (M) to (Q). n = 4; ***P < 0.001, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (S) Quantification of the average mitochondrial diameter in (M) to (Q). n = 6 images for each genotype; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (T) ATP production in the tissues with indicated genotypes. CTPsyn or ND-15 RNAi tissues had reduced ATP production. n = 3 replicates; 20 larvae per replicate; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (U to W) ROS production was increased in the CTPsyn or ND-15 RNAi cells. The green signals of DCFH-DA staining indicated the production of ROS. DAPI staining (blue) indicated the nuclei. Scale bars, 5 μm. (X) Quantification of the relative level of DCFH-DA in (U) to (W). n = 4 images for each genotype; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test.

In this screen, we also identified other genes encoding proteins localized in the mitochondria, including genes regulating mitochondrial DNA and protein synthesis [CG33650 encoding DNApol-γ35 for mitochondrial DNA replication (fig. S2E) (21) and CG6050 encoding a mitochondrial translation elongation factor (fig. S2F) (22)], genes responsible for mitochondrial protein degradation [YME1L (Fig. 1Q) and a peptidase encoded by CG6512 (fig. S2G)], genes required for material exchange between mitochondria and cytosol and protein importing [CG10920 (fig. S2H), CG3057 (fig. S2I), CG6851 (fig. S2J), porin (fig. S2K), and Tom40 (Fig. 1E)], genes encoding electron transfer flavoproteins [CG7834 (fig. S2L) and CG12140 (fig. S2M)], genes required for metabolism [CG3140 encoding adenylate kinase 2 (fig. S2N), CG3835 encoding d-lactate dehydrogenase (fig. S2O), CG2718 encoding glutamine synthetase (fig. S2P), and CG11876 encoding pyruvate dehydrogenase (fig. S2Q)], and a gene (CG6459) whose protein product binds to mitochondrial ribosomes (fig. S2R).

Peroxisomes are organelles that are closely related to mitochondria. In this screen, we identified multiple genes encoding proteins that were required for proper peroxisome functions. For example, Pex1 (fig. S2S), Pex13 (fig. S2T), and Pex19 (fig. S2U) are genes required for peroxisome organization, and their loss led to mitochondrial morphology defects. CRAT and Mfe2 are genes required for fatty acid β-oxidation (fig. S2, V and W). Hmgcr is a gene required for nonsterol isoprenoid production (fig. S2X). The loss of these genes also resulted in abnormal mitochondrial morphology.

Twenty-seven members of nuclear mRNA splicing complexes and 16 proteins in proteolysis complexes were identified in our screen, suggesting that mRNA splicing and proteolysis are critical for mitochondrial morphology [figs. S3 (A to Q) and S4 (A to Z) and table S5].

Members that belong to the same complex tended to cause similar phenotypes when their functions were blocked. For example, the reduction in the expression of genes encoding proteasome subunits [such as Rpn1 (fig. S3B), Rpn6 (fig. S3D), Rpn7 (fig. S3E), Rpn8 (fig. S3F), Rpn11 (fig. S3H), Rpt2 (fig. S3J), Prosα5 (fig. S3M), Prosα7 (fig. S3N), Prosβ5 (fig. S3P), and Prosβ6 (fig. S3Q)] often led to a distinct fuzzy mitochondria phenotype. Under confocal microscope, the mitochondria formed clusters, and the outlines of the mitochondria became fuzzy. We used TEM to further study the morphology of the mitochondria in Prosα7 RNAi and Rpn11 RNAi tissues (fig. S3, R to T, R’ to T′, and R″ to T″). In the wild-type cells, the mitochondria were evenly distributed inside fat body cells (fig. S3, R, R′, and R″). In the Prosα7 RNAi (fig. S3, S, S′, and S″) and Rpn11 RNAi (fig. S3, T, T′, and T″) tissues, a large amount of the mitochondria tended to cluster together, although the morphology of the individual mitochondrion was relatively normal.

In this screen, we identified 27 genes encoding spliceosome components (fig. S4, A to Z″, and table S5). The knockdown of some of these genes resulted in very similar mitochondrial morphology defects. For example, the mitochondria in the tissues with SmB (fig. S4B), SmD3 (fig. S4C), SnRNP-U1-70K (fig. S4D), l(3)72Ab (fig. S4O), CG6841 (fig. S4P), Prp8 (fig. S4Q), CG6015 (fig. S4R), or CG9667 (fig. S4U) knockdown tended to become fragmented and clustered. Mitochondria adopted a fragmented morphology when SnRNP-U1-C (fig. S4E), U2af38 (fig. S4G), Sf3a1 (fig. S4H), Sf3b2 (fig. S4I), Sf3b5 (fig. S4J), noi (fig. S4K), LSm7 (fig. S4L), prp3 (fig. S4N), Bx42 (fig. S4S), crn (fig. S4T), Ref1 (fig. S4W), Hsc70-1 (fig. S4Y), Hsc70-2 (fig. S4Z), or Hsc70-4 (fig. S4Z′) was knocked down. Knocking down genes encoding proteins belonging to the same complex did not necessarily cause the same mitochondrial phenotypes, likely because of the functional diversity of each protein. For example, Hsc70-1, Hsc70-2, and Hsc70-4 not only are spliceosome components but also function as chaperones.

The KEGG pathway analysis (23) indicated that four (Got1, Hgo, GstZ2, and Faa) of five enzymes participating in the catabolism of tyrosine were required for proper mitochondrial morphology (fig. S5A). When their expression was reduced, mitochondria became fragmented and sometimes clustered (fig. S5, B to F). In addition, the enzyme required for hydrolyzing tyrosine to l-dopa was also necessary for maintaining mitochondrial morphology (fig. S5G). Furthermore, we found that lysine metabolism could modulate mitochondrial morphology (fig. S5H). Knocking down genes such as LKRSDH or CG9629 that encode enzymes that participate in lysine degradation affected mitochondrial morphology (fig. S5, I to K). Genes encoding enzymes involved in the synthesis of carnitine from trimethyllysine and enzymes methylating protein lysine residues were also identified in our screen (fig. S5, K to Q). Most of these proteins mentioned above are not localized on the mitochondria. Therefore, the mitochondrial morphology changes in the tissues with those proteins reduced were likely due to indirect effects.

Loss of Dhpr phenocopies the loss of PD-related genes Pink1 and park

We found that the loss of PD-related genes, Pink1 and park, led to big mitoGFP puncta formed inside fat body tissues in our screen (Fig. 3, A to C and I). Two other genes’ loss could also result in a very similar but less severe mitochondrial phenotype. Those two genes were ben and Dhpr (Fig. 3, D, E, and I). Ben encodes an E2 whose mammalian ortholog functions in the same pathway with Pink1 and parkin to regulate the mitophagy process (24). Dhpr encodes a dihydropteridine reductase, which catalyzes the reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH)–mediated regeneration of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) from dihydrobiopterin (BH2) (25). BH4 functions as a cofactor to convert amino acids such as phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan to precursors of dopamine and serotonin. It also serves as a catalyst for the production of nitric oxide (NO) (25). Overexpression of the complementary DNA (cDNA) of Dhpr could rescue the mitochondrial defects caused by Dhpr RNAi (Fig. 3, F and I), suggesting that the mitochondrial defects were caused by the reduction of Dhpr. TEM analysis indicated that many mitochondria are enlarged and have less cristae in Dhpr RNAi fat body tissues (Fig. 3, G, H, J, and J′), which is very similar to what has been observed in Pink1/park mutants. We also examined the markers for Golgi (ManII; fig. S6, A and D), peroxisomes (SKL-GFP; fig. S6, B and E), and ER (KDEL-RFP; fig. S6, C and F) in Dhpr RNAi and control fat body tissues. The patterns of Golgi and ER markers are similar in Dhpr RNAi and control fat body tissues (fig. S6, A and D, C and F, and G and H). However, SKL-GFP puncta in Dhpr RNAi tissues are larger than that in the control tissues (fig. S6, B and E, and G and H). Because peroxisomes are closely related to mitochondria, Dhpr might regulate the common regulating machinery shared by both organelles.

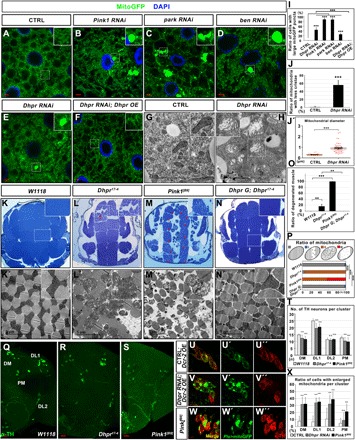

Fig. 3. The loss of Dhpr leads to mitochondrial defects similar to those in Pink1 mutant animals.

(A) Control (CTRL). (B to E) The RNAi of indicated genes in the fat body tissues led to similar mitochondrial phenotypes. (F) Dhpr overexpression (Dhpr OE) rescued the mitochondrial defects in Dhpr RNAi fat body tissues. (G and H) TEM analysis of the fat body tissues in the animals with indicated genotypes. Dhpr RNAi led to swollen of the mitochondria and the reduction of cristae in fat body tissues. (I) Quantification of the ratio of cells with large mitoGFP puncta in (A) to (F). n = 5; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (J) Quantification of the ratio of mitochondria with less cristae in (G) to (H). n = 3 images of each genotype; ***P < 0.001, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. (J′) Quantification of the average mitochondrial diameter in (G) to (H). n = 47; ***P < 0.001, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. (K to N) Toluidine blue staining of the fly thorax thick sections with indicated genotypes. The boxed region was enlarged in the inset to show the detailed defects. In the 35-day-old flies, flight muscle fragments were disorganized (red arrows) in Dhpr17-4 and Pink1[B9] flies. (N) Dhpr genomic fragment (Dhpr G) could rescue the muscle defects in Dhpr17-4 mutant. (K′ to N′) TEM analysis of the thin sections of the fly thorax. The mitochondria in Dhpr17-4 mutant muscles are swollen and have less cristae. (O) Quantification of the ratio of degenerated muscle in (K) to (N). n = 4; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (P) Quantification of the ratio of mitochondria in (K′) to (N′). The diagram on top of this panel shows the typical normal mitochondria (gray) and abnormal mitochondria. The abnormal mitochondria were categorized into three types based on cristae morphology. Type I (blue): Mitochondria lost some cristae, and there are obvious empty spaces between tightly packed cristae. Type II (orange): The cristae of the mitochondria are disorganized and loose. Type III (red): Mitochondria lost most of its cristae, and more than half of the mitochondria area was empty. n = 3 images for each genotype; ***P < 0.001, χ2 (and Fisher’s exact) test. (Q to S) Anti-TH staining (green) of the adult brains from the 35-day-old animals with indicated genotypes. The TH neurons in different brain regions were labeled in (Q). The number of TH neurons in Dhpr and Pink1 mutant animals is significantly reduced in DM, DL1, and PM regions. (T) Quantification of the number of TH neurons from the animals with indicated genotypes. n = 45; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. n.s., not significant. (U to W) The mitochondria become swollen in the TH neurons from the 5-day-old animals when Dhpr were knocked down in TH neurons. Five-day-old Pink1 mutants also had swollen mitochondria in the TH neurons. Mitochondria were labeled by mitoGFP (green). The TH neurons were labeled by anti-TH staining (red). (X) Quantification to show the ratios of cells with enlarged mitochondria per TH neuron cluster. n = 40; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test.

We then made Dhpr mutant flies using the CRISPR-Cas9 technique (26). We identified two alleles, Dhpr17-4 and Dhpr42-5, with small deletions that resulted in premature stop of the translations (fig. S6I). Both alleles have similar phenotypes, and we therefore focused on the allele Dhpr17-4 for detailed analysis. Some Dhpr17-4 flies could survive to adulthood, are fertile, and have normal wing postures (fig. S6J). However, it is very difficult to maintain a homozygous mutant stock. In addition, the heterozygous stock does not produce homozygous animals in a Mendelian ratio [41% heterozygous flies (Dhpr17-4/TM6B) and 1% homozygous (Dhpr17-4/Dhpr17-4) mutants survived to adulthood (n = 300)], suggesting that many Dhpr17-4 flies could not survive to adulthood. For those who made to the adult stage, they showed a reduced life span (fig. S6K). In the early third-instar fat body tissues, the loss of Dhpr results in an increased ROS level indicated by the elevated gstD1 GFP signals (fig. S6, L, M, and O) and 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) staining (fig. S6, P to R). The gstD1 GFP signals in Dhpr mutants are comparable to those in Pink1[B9] mutants (fig. S6, N and O). In addition, Dhpr17-4 flies showed a gradually decreased climbing ability (fig. S6S). The climbing index of Dhpr17-4 flies was very similar to that of Pink1[B9] flies (fig. S6S). Because the loss of Dhpr led to climbing defects, mitochondria in the flight muscle might have defects. To examine the mitochondrial transmembrane potential, we stained the flight muscle tissues from 15-day-old flies with JC-1. Dhpr17-4 mutants show reduced mitochondrial potential (ΔΨm) compared to the wild-type controls (fig. S6, T to V). In addition, the ROS production indicated by gstD1 GFP expression was increased in the flight muscle tissues of the 15-day-old Dhpr17-4 mutants (fig. S6, X to Z). In the 35-day-old flies, some flight muscle fragments were disorganized (Fig. 3, K, L, and O), which is similar to but less severe than what has been observed in Pink1[B9] flies (Fig. 3, M and O). We further examined the thin section of the muscles using TEM. In Dhpr mutant flies, some of the muscle fibers were lost or disorganized (Fig. 3, K′ and L′). In the affected muscle fragments, mitochondria were swollen and had less cristae (Fig. 3, K′, L′, and P). These muscle defects could be rescued by a genomic fragment containing only Dhpr (Fig. 3, N, N′, O, and P), indicating that the loss of Dhpr is responsible for the phenotypes. Using anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) antibody staining, we also found that, in 35-day-old Dhpr17-4 mutants, the numbers of TH neurons in the dorsomedial (DM), dorsolateral (DL) 1, and posteriomedial (PM) regions were reduced (Fig. 3, Q, R, and T). To examine whether there are mitochondrial defects before the loss of the TH neurons, we examined the mitochondrial morphology in the TH neurons of the 5-day-old wild-type or mutant animals. When knocking down Dhpr expression specifically in TH neurons using Ple-Gal4, we found that mitoGFP-labeled mitochondria in most of the TH neurons became enlarged and clustered (Fig. 3, U, V, and X). Similar phenotypes were also observed in the age-matched Pink1[B9] flies (Fig. 3, S and T, and W and X).

Pink1/park functions in parallel with Dhpr

Because Pink1 and Dhpr mutants have similar phenotypes (Fig. 3, B and E, L and M, R and S, and V and W), we suspected that they might function in a same pathway to regulate mitochondrial morphology and tissue homeostasis. Therefore, we performed the epistasis analysis between Dhpr, Pink1, and park. In fly fat body tissues, Dhpr RNAi leads to big mitochondrial puncta formed inside cells (Fig. 4, A and B). Pink1 or park overexpression alone does not cause marked mitochondrial morphology changes (Fig. 4, C and D). However, when Pink1 or park was overexpressed in Dhpr RNAi tissues, the big mitochondrial puncta disappeared, and the mitochondria looked grossly normal (Fig. 4, E, F, and I). Fat body tissues with Pink1 RNAi accumulate large mitochondrial puncta (Fig. 3B). The mitochondrial puncta remained when Dhpr was overexpressed in Pink1 RNAi tissues (Fig. 4, G to I). These data suggested that Dhpr functions either upstream or in parallel with Pink1/park. In the flight muscles, Dhpr RNAi results in disorganized muscle fibers in some muscle fragments (Fig. 4, J, K, and P) in the 3-day-old animals. Some of the mitochondria have less cristae (Fig. 4, J′, K′, and Q). The toluidine blue staining of the thick section of the thorax indicated that Pink1 or park overexpression could rescue the muscle integrity of the Dhpr RNAi animals (Fig. 4, K to P). However, the TEM analysis indicated that Pink1 overexpression in wild-type animals slightly reduced the mitochondrial size and led to mild cristae abnormality (Fig. 4, L′, Q, and Q′). The overexpression of Pink1 also reduced the mitochondrial size of the Dhpr RNAi animals (Fig. 4, M′ and Q′). When Pink1 was overexpressed in Dhpr RNAi muscles, the mitochondrial cristae density was increased compared with that in Dhpr RNAi muscles (Fig. 4, K′, M′ and Q). park overexpression in wild-type animals did not cause any obvious defects in muscles (Fig. 4, N and N′). When park was overexpressed in Dhpr RNAi muscles, although the mitochondria in some muscle fragments look normal (Fig. 4, O and O′), those in the other muscle fragments still have defective cristae morphology (Fig. 4, O″ and Q). Although it could partially rescue the mitochondrial morphology, Pink1 and park overexpression could not rescue the climbing defects caused by the reduction of Dhpr in 3-day-old flies (fig. S7A). We also examined the muscle integrity and the mitochondrial morphology in 35-day-old flies (fig. S7, B to J). The muscle degeneration in the 35-day-old Dhpr RNAi flies was more severe than that in the 3-day-old ones (Fig. 4K and fig. S7C), indicating that the muscle degeneration is progressing with aging. The size of the mitochondria became irregular, and the cristae organization was severely damaged in the old Dhpr RNAi animals (fig. S7, C′, C″, and I). When Pink1 was overexpressed, the muscle fibers look grossly normal in 35-day-old animals (fig. S7, D and H), but the mitochondria become round and the spaces between mitochondria and the myotubes are larger than that in controls (fig. S7, B′ and D′). Pink1 overexpression could largely rescue muscle fiber organization in Dhpr RNAi animals (fig. S7, F and H). However, the cristae in some mitochondria were not well organized, and mitochondria sizes were irregular (fig. S7, F′, F″, I, and J). When Park was overexpressed, the overall muscle organization was normal in 35-day-old animals (fig. S7, E and H). However, the distribution of mitochondria was different from that in wild-type controls (fig. S7, B′ and E′). When park was overexpressed in Dhpr RNAi muscles, although the overall muscle degeneration looks less severe than that in Dhpr RNAi alone animals, many of the muscle fragments still have small lesions (fig. S7, G and H). A small fraction of mitochondria has defective cristae organization, and the size of the mitochondria is variable (fig. S7, G′, G″, I, and J). These data suggest that the overexpression of Pink1 and park could partially rescue the muscle defects caused by Dhpr RNAi in both young and old animals. We then knocked down Dhpr expression in Pink1[B9] animals and examined the muscle integrity in the 3-day-old animals. In the young Pink1[B9] animals, many muscle fibers are disorganized, but there are some fibers that still look normal (Fig. 4, R and T). Similarly, mitochondria with less cristae exist in the Pink1[B9] mutant muscle fibers (Fig. 4R″), and there are also normal-looking mitochondria with dense cristae resembling those of the wild-type animals (Fig. 4R′). Dhpr knockdown in the muscle of Pink1[B9] mutant animals significantly enhanced the muscle defects of the Pink1[B9] mutant animals (Fig. 4, S, S′, T, and U). In these animals, the flight muscle fibers in the 3-day-old animals are severely disorganized, and all the mitochondria have abnormal cristae. These data suggested that Dhpr functions in parallel with Pink1/park to regulate mitochondrial morphology.

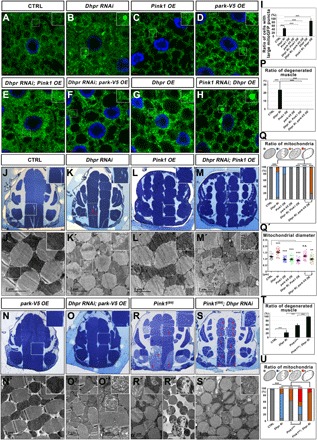

Fig. 4. Pink1 and park overexpression could partially rescue mitochondrial defects in Dhpr mutants.

(A to H) Mitochondrial morphology in the fat body tissues of the animals with indicated genotypes was accessed through confocal microscopy by examining the mitoGFP signals (green). The nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). The boxed regions were enlarged in the insets to show the detailed mitochondrial morphology. Dhpr RNAi led to large mitoGFP puncta formed inside the fat body cells. Pink1/park overexpression could reduce the large mitoGFP puncta formation in Dhpr RNAi tissues. However, Dhpr overexpression could not rescue the mitochondrial defects in Pink1 RNAi tissues. (I) Quantification of the ratio of cells with large mitoGFP puncta in (A) to (H). Ri, RNAi; OE, overexpression; n = 5; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (J to O) Toluidine blue staining of the fly thorax thick sections from 3-day-old flies with indicated genotypes. The boxed regions were enlarged in the insets to show the detailed defects. Muscle-specific knockdown of Dhpr led to disorganized muscle fragments indicated by the holes (red arrows) on the muscle fragments. Pink1 and park overexpression largely rescued the muscle defects. (P) Quantification of the ratio of degenerated muscles in (J) to (O). n = 4; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (J′ to O″) The thin sections of the fly thorax were examined by TEM. Dhpr RNAi led to the enlargement of mitochondria and the reduction of cristae. Pink1 overexpression in wild-type animals reduced the mitochondrial size and led to mild cristae abnormality. The overexpression of Pink1 also reduced the mitochondrial size of the Dhpr RNAi animals and largely rescued the mitochondrial cristae defects caused by Dhpr RNAi. park overexpression could rescue the mitochondrial morphology defects in some muscle fragments (O′) but could not do so in the other muscle fragments (O″). (Q) Quantification of the ratio of mitochondria in (J′) to (O″). The diagram on top of this panel showed the typical normal mitochondria (gray) and abnormal mitochondria. The abnormal mitochondria were categorized into three types based on cristae morphology. Type I (blue): Mitochondria lost some cristae, and there are obvious empty spaces between tightly packed cristae. Type II (orange): The cristae of the mitochondria are disorganized and loose. Type III (red): Mitochondria lost most of its cristae, and more than half of the mitochondria area was empty. n = 3 images of each genotype; ***P < 0.001, χ2 (and Fisher’s exact) test. (Q′) Quantification of the mitochondrial diameters in (J′) to (O″). n = 27; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (R and S) Toluidine blue staining of the fly thorax thick sections from 3-day-old flies with indicated genotypes. The boxed regions were enlarged in the insets to show the detailed defects. Pink1[B9] had severe muscle degeneration, and Dhpr knockdown further enhanced the muscle defects of Pink1[B9]. (R′ and S′) Thin sections of the fly thorax were examined by TEM. Three-day-old Pink1[B9] mutants had both intact mitochondria (R′) and severely damaged mitochondria (R″). Almost all of the mitochondria were abnormal when knocking down Dhpr in Pink[B9] mutant background. (T) Quantification of the ratio of degenerated muscles in (J), (K), (R), and (S). n = 7 to 10; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (U) Quantification of the ratio of mitochondria in (J′), (K′), (R′), and (S′). n = 3 images for each genotype; ***P < 0.001, χ2 (and Fisher’s exact) test. The categories of mitochondria are the same as those in (Q). The scale bars in the immunofluorescence images are 5 μm. The scale bars in the TEM images are as indicated.

Reduction of Nos enhanced mitochondrial defects caused by Dhpr RNAi

The gene products of Dhpr’s human ortholog QDPR are listed in the inventory of proteins localized to mitochondria (MitoMax and MitoCarta) (27, 28). We therefore investigate whether Dhpr localizes on the mitochondria. We expressed V5-tagged Dhpr in S2 cells. Dhpr showed a diffused cytosolic pattern with no specific colocalization with mitochondria (fig. S7, K, K′, and K″). To avoid the possibility that the diffused pattern of Dhpr is due to overexpression, we transfected a genomic fragment with Dhpr tagged at the C terminus with V5 into S2 cells and examined Dhpr’s pattern with anti-V5 staining. Although the expression level was much lower than the overexpression experiments, Dhpr was still diffused inside the cell (fig. S7, L, L′, and L″). We also examined Dhpr pattern in the fat body tissues with the expression of a genomic rescue construct that had a V5 tag at the C terminus of the Dhpr coding sequence. Again, there was no specific mitochondria-localized V5 signals, and the overall pattern of Dhpr was diffused (fig. S7, M, M′, and M″). To examine whether quinoid dihydropteridine reductase (QDPR), the mammalian counterpart of Dhpr, was localized specifically on the mitochondria, we cotransfected Hela cells with GFP-tagged QDPR (C-terminal tag) and MitoRFP. Similar to Dhpr, QDPR also had a diffused pattern without specific mitochondrial localization (fig. S7, N, N′, and N″). It suggested that Dhpr might indirectly regulate mitochondrial morphology. Dhpr is an enzyme catalyzing the regeneration of BH4 from BH2. We then wanted to test whether the enzyme activity of Dhpr is required for mitochondrial integrity. QDPR is the mammalian ortholog of Dhpr. QDPRG23D mutation is a recurrent mutation in human patients, which renders the enzyme completely inactive (29). The 23rd glycine in QDPR corresponds to the 16th glycine in fly Dhpr (fig. S8A). We therefore made a transgene expressing the mutant form of Dhpr, DhprG16D, and expressed it in fat body and muscles alone or together with Dhpr shRNA (short hairpin RNA). As a control, the wild-type Dhpr was overexpressed in the same manner. Overexpression of wild-type Dhpr or DhprG16D alone did not cause obvious mitochondrial defects in both fat bodies (Fig. 5, A, C, D, Q, and Q′) and flight muscles (Fig. 5, E, G, H, and R, and E′, G′, H′, and S). Wild-type Dhpr overexpression could rescue the mitochondrial defects induced by Dhpr RNAi in both fat bodies (Fig. 5, B, I, Q, and Q′) and flight muscles (Fig. 5, F, M, and R, and F′, M′, and S). However, mitochondrial defects became worse when DhprG16D was overexpressed in Dhpr RNAi tissues (Fig. 5, B, J, Q, and Q′; F, N, and R; and F′, N′, and S), suggesting that the enzyme activity of Dhpr is required for maintaining mitochondrial morphology and that DhprG16D likely has weak dominant negative effects. When we assessed the climbing activity, we found that wild type but not DhprG16D rescued the climbing defects caused by the reduction of Dhpr (fig. S7A).

Fig. 5. The catalytic activity of Dhpr is required for its mitochondrial function.

(A to D and I to L) Confocal images showing mitochondrial morphology in the fat body tissues of the third-instar larvae with indicated genotypes. The green signals from mitoGFP labeled the mitochondria, and the blue signals were nuclei labeled with DAPI. Scale bars, 5 μm. Wild-type Dhpr overexpression rescued the mitochondrial defects in Dhpr RNAi fat bodies. DhprG16D overexpression did not rescue the mitochondrial defects but worsened it in Dhpr RNAi tissues. Nos RNAi did not cause obvious mitochondrial defects in wild-type fat body tissues but greatly enhanced the mitochondrial defects in Dhpr RNAi fat body tissues. (E to H and M to P) Toluidine blue staining of the fly thorax thick sections from 3-day-old flies with indicated genotypes. The red arrows indicated the disorganized muscle fragments. (E′ to H′ and M′ to P′) TEM images of thorax thin sections showing the detailed morphology of mitochondria and muscle fibers. The scale bars are as indicated. (Q) Quantification of the ratio of cells with large mitoGFP puncta in (A) to (D) and (I) to (L). n = 5; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (Q′) Quantification of the average number of large mitoGFP puncta per affected cell in (A) to (D) and (I) to (L). n = 10; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (R) Quantification of the ratio of degenerated muscle in (E) to (H) and (M) to (P). n = 4 to 10; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (S) Quantification of the ratio of mitochondria in (E) to (H) and (M) to (P). The diagram on top of this panel shows the typical normal mitochondria (gray) and abnormal mitochondria. The abnormal mitochondria were categorized into three types based on cristae morphology. Type I (blue): Mitochondria lost some cristae, and there are obvious empty spaces between tightly packed cristae. Type II (orange): The cristae of the mitochondria are disorganized and loose. Type III (red): Mitochondria lost most of its cristae, and more than half of the mitochondria area was empty. n = 3 images for each genotype; ***P < 0.001, χ2 (and Fisher’s exact) test.

Punch (Pu) encodes an enzyme that is required for de novo BH4 synthesis (fig. S8B). The knockdown of Pu expression alone did not cause obvious mitochondrial morphology defects in fat body tissues (fig. S8, C, E, and O). However, knocking down Pu expression in Dhpr RNAi tissues greatly enhanced the mitochondrial defects caused by Dhpr RNAi alone (fig. S8, F, O, and P). The mitochondria became swollen and severely damaged, indicating that BH4 is critical for maintaining the proper mitochondrial morphology.

BH4 functions as a cofactor to produce NO and synthesis of the precursors of dopamine and serotonin (25). Nitric oxide synthase (Nos) encodes a NO synthase that produces NO using arginine and converts BH4 to BH2 at the same time (fig. S8B). Henna (Hn) uses BH4 as a cofactor to hydroxylate both phenylalanine to form tyrosine and tryptophan to generate the precursor for peripheral serotonin (fig. S8B). Pale (Ple) then uses BH4 as a cofactor to catalyze tyrosine to form l-dopa (fig. S8B). Tryptophan hydroxylase (Trh) catalyzes the conversion of tryptophan to 5-hydroxytryptophan and converts BH4 to BH2 at the same time. Trh has also a phenylalanine 4-monooxygenase activity to catalyze the conversion of phenylalanine to tyrosine (fig. S8B). To distinguish which pathway that required BH4 is critical for mitochondrial morphology, we knocked down the expression of Nos, hn, ple, and Trh individually, or each together with Dhpr, and examined the mitochondrial morphology in fat bodies. The knockdown of Nos (Fig. 5, K, Q, and Q′), hn (fig. S8, G, O, and P), and Trh (fig. S8, H, O, and P) alone did not cause obvious mitochondrial defects. As mentioned before, ple knockdown led to fragmentation of the mitochondria (fig. S8I), a phenotype that was distinct from the phenotypes that were observed in Dhpr RNAi tissues. When we reduced the expression of Nos and Dhpr together (Fig. 5, L, P, and P′), the mitochondrial morphology defects were greatly enhanced (Fig. 5, L, Q, and Q′; P and R; and P′ and S). However, the knockdown of hn, Trh, or ple together with Dhpr does not enhance Dhpr RNAi phenotypes (fig. S8, J to L, O, and P). The synergistic effect of the Nos and Dhpr double RNAi suggests that Nos might function together with BH4 regenerated by Dhpr to regulate mitochondrial morphology.

Dhpr regulates mitochondrial morphology by modulating S-nitrosylation of Drp1

The big mitochondrial puncta in Pink1 and park mutant could be rescued by reducing the expression of Marf or increasing the expression of Drp1 (30, 31). We therefore tested whether manipulating the expression of the key molecules regulating mitochondrial fusion or fission could modify the mitochondrial phenotypes in Dhpr RNAi tissues. The knockdown of Marf or Opa1 in Dhpr RNAi tissues results in increased clusters of mitochondria compared with that in the tissues with Dhpr RNAi alone (fig. S9, A to F, K, and L). When Myc-tagged Marf was overexpressed in the Dhpr RNAi tissues (fig. S9, H, K, and L), the size of mitochondrial puncta was greatly increased compared with that in Dhpr RNAi alone (fig. S9, B, H, K, and L) or Marf overexpression alone (fig. S9, G, K, and L). We found that the overexpression of Drp1 could rescue the mitochondrial defects observed in Dhpr RNAi fat body tissues (Fig. 6, A to D and I). In addition, the overexpression of Drp1 also partially rescued the mitochondrial morphology defects in Dhpr, Pu or Dhpr, Nos double RNAi animals (Fig. 5L and fig. S8, F and M to P). The decreased Drp1 expression in tissues with Dhpr RNAi led to mitochondrial defects similar to that in Drp1 RNAi alone, and the defects were more severe compared to those in Dhpr RNAi alone (fig. S9, B and I to L). We further tested whether Drp1 overexpression could also rescue the mitochondrial defects in fly muscles. We used Mef-Gal4 to drive the expression of UAS-Drp1 and UAS-shRNA targeting Dhpr in fly muscles and examined muscle mitochondrial morphology using TEM. Drp1 expression could rescue the defects in both the muscle fiber (Fig. 6, E to H and J) and mitochondria (Fig. 6, E′ to H′, K, and K′). Consistent with these data, Drp1 expression also rescued the climbing defects in Dhpr RNAi flies (fig. S7A). We then tested whether the expression of Drp1 in Dhpr RNAi tissues was reduced. The thorax tissues from the control or Dhpr RNAi tissues were dissected, and the expression of Drp1 and Marf was examined by Western blot (fig. S9M). As a control, the tubulin level was also assessed for the same samples. Unexpectedly, the Drp1 level was not reduced but slightly increased in Dhpr RNAi tissues (fig. S9, M and N). The expression of Marf was not changed (fig. S9, M and N). This suggested that Dhpr RNAi might reduce the activity, but not the level, of Drp1, and the overexpression of Drp1 could compensate for the reduction of its activity.

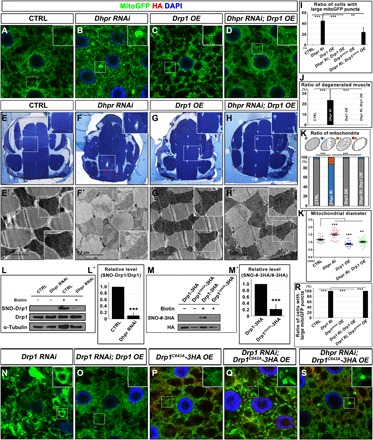

Fig. 6. Dhpr regulates mitochondrial morphology by modulating S-nitrosylation of Drp1.

(A to H and E′ to H′) Drp1 overexpression could rescue Dhpr RNAi-induced mitochondrial defects in fat body tissues (A to D) and muscles (E to H and E′ to H′). (I) Quantification of the ratio of cells with large mitoGFP puncta in (A) to (D), (P), and (S). n = 5; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (J) Quantification of the ratio of degenerated muscle in (E) to (H). n = 4 to 10; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (K) Quantification of the ratio of mitochondria in (E′) to (H′). The diagram on top of this panel shows the typical normal mitochondria (gray) and abnormal mitochondria. The abnormal mitochondria were categorized into three types based on cristae morphology. Type I (blue): Mitochondria lost some cristae, and there are obvious empty spaces between tightly packed cristae. Type II (orange): The cristae of the mitochondria are disorganized and loose. Type III (red): Mitochondria lost most of its cristae, and more than half of the mitochondria area was empty. n = 3 images for each genotype; ***P < 0.001, χ2 (and Fisher’s exact) test. (K′) Quantification of the average mitochondrial diameter in (E′) to (H′). n = 27; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. (L and L′) Dhpr RNAi reduced S-nitrosylation of Drp1. (L′) Quantification of (L). n = 3 replicates; 15 individual flies per replicate; ***P < 0.001, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. (M and M′) C643 site was a major S-nitrosylation site of Drp1 in vivo. C643A mutation in Drp1 greatly reduced S-nitrosylation of Drp1. (M′) Quantification of (M). n = 3 replicates; 15 individual flies per replicate; ***P < 0.001, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. (N to Q) Overexpression of Drp1, but not Drp1C643A, could rescue mitochondrial defects caused by Drp1 RNAi. (S) Drp1C643A overexpression cannot rescue Dhpr RNAi-induced mitochondrial defects in fat body tissues. (A to D, N to Q, and S) Images of fat body cells with indicated genotypes. Mitochondria were marked by mitoGFP signals (green), and nuclei were marked by DAPI staining (blue). Drp1C643A-3HA expression was indicated by anti-HA staining (red). Scale bars, 5 μm. (E to H) Toluidine blue staining of the 3-day-old fly thorax thick sections with indicated genotypes. The red arrows indicated the disorganized muscle fragments. (E′ to H′) TEM images of thorax thin sections showing the detailed morphology of mitochondria and muscle fibers. The scale bars are as indicated. (R) Quantification of the ratio of cells with large mitoGFP puncta in (A) and (N) to (S). n = 7; ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test.

It has been reported that Drp1 was activated by NO-mediated S-nitrosylation (32). We therefore examined whether the S-nitrosylation of Drp1 (SNO-Drp1) was reduced in Dhpr RNAi animals. We used Mef-Gal4 to drive the expression of Dhpr shRNA in muscles and dissected adult thorax muscle tissues for the S-nitrosylation assays. We found that the knockdown of Dhpr reduced the SNO-Drp1 level (Fig. 6, L and L′). It has been reported that the mammalian Drp1 was S-nitrosylated at Cys644, a site that is conserved and corresponds to Cys643 in fly Drp1 (fig. S9O) (32). To examine whether Cys643 is the key S-nitrosylation site, we expressed hemagglutinin (HA)–tagged wild-type Drp1 or DrpC643A in fly muscles and examined the S-nitrosylation level of the ectopically expressed Drp1. The SNO-Drp1 level was greatly reduced when Cys643 was mutated to alanine (Fig. 6, M and M′). The expression of DrpC643A transgene could not rescue Drp1 RNAi defects as the wild type does (Fig. 6, N to Q and R), suggesting that it is an inactive form of Drp1. We expressed this mutant form of Drp1 in fat body tissues alone or together with Dhpr shRNA. The overexpression of Drp1C643A alone did not produce obvious mitochondrial morphology changes (Fig. 6P). When Drp1C643A was expressed in the Dhpr RNAi tissues (Fig. 6S), it could not rescue the mitochondrial defects caused by the reduction of Dhpr (Fig. 6, B, S, and I). Together, these data suggested that Dhpr regulates mitochondrial morphology by promoting the S-nitrosylation of Drp1.

DISCUSSION

Several cell culture–based large-scale RNAi screens have been conducted to investigate molecules regulating Pink1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy (17). Until now, no systematical analysis of the regulatory network of mitochondrial morphology has been performed. Here, we identified 578 genes that regulate mitochondrial morphology, many of which were identified for the first time. The large number of the genes identified in this screen indicates that many cellular events are linked to the regulation of mitochondrial morphology. Because RNAi might have off-target effects, further confirmations are needed to validate the effects of the hits.

Using COMPLEAT and the KEGG pathway analysis, we identified multiple important pathways and built up a network of the regulators of mitochondrial morphology under in vivo conditions. Some mitochondrial phenotypes, such as fragmented, fragmented and clustered, tubular, and tubular and clustered, are common phenotypes. On the contrary, swollen and fuzzy mitochondria are rather specific phenotypes, and the affected genes often function in the same pathway. For example, the reduction of the expression of proteasome subunits results in fuzzy and clustered mitochondria, a phenotype that we seldom see when genes other than the ones encoding proteasome subunits were knocked down. Similarly, the reduction of the expression of ETC components often leads to the swollen mitochondria. Therefore, these mitochondrial phenotypes might be an indication of the involvement of a particular pathway. In this study, we found that the loss of CTPsyn results in a mitochondrial phenotype that is very similar to the phenotype observed in tissues with a reduction in ETC components. The increase in ROS and reduction in ATP synthesis were also observed in CTPsyn RNAi tissues. CTPsyn forms filamentous polymers in the cytosol and is the rate-limiting enzyme for the synthesis of CTP from both the de novo and uridine salvage pathways. In flies, CTPsyn is an essential gene required for brain development. Although the biochemical activity, structure, and subcellular distribution of CTPsyn are well studied, CTPsyn functions have never been linked to mitochondrial respiration (33). Because CTP is a precursor required for the metabolism of DNA, RNA, and phospholipids, it would be interesting to test whether the reduction of CTPsyn affects these processes in mitochondria. CTP:phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase (PCYT2) is a rate-limiting enzyme that uses CTP as a precursor to synthesize cytidine diphosphate (CDP)–ethanolamine Kennedy pathway intermediates. It has been shown that inhibition of PCYT2 results in the buildup of its substrate, phosphoethanolamine (PEtn), which directly inhibits mitochondrial respiration (34). The synthesis of other phospholipids such as cardiolipin, a mitochondria-specific phospholipid, also requires CTP (35). Determining whether the mitochondrial defects in CTPsyn RNAi tissues were due to the accumulation of PEtn or the lack of key phospholipids such as cardiolipin requires further investigation.

In this screen, we found that four of five genes participating in the catabolism of tyrosine were required for the maintenance of proper mitochondrial morphology. The reduction in these genes’ expression led to the fragmentation of the mitochondria, a phenotype that usually results from the increase in mitochondrial fission or the reduction of mitochondrial fusion. Tyrosine is an aromatic amino acid important in the synthesis of thyroid hormones, catecholamines, and melanin. The end products of tyrosine catabolism are acetoacetate and fumarate, two molecules that can then enter into the citric acid cycle. How the lack of these enzymes led to misregulation of mitochondrial morphology requires elucidation. Impaired catabolism of tyrosine is a feature of several acquired and genetic disorders. It would be interesting to evaluate whether there is a mitochondrial defect in those patients.

Notably, knocking down genes encoding proteins belonging to the same complex sometime causes different mitochondrial phenotypes, which is consistent with the phenotypic heterogeneity observed in diseases that are caused by mutations in different nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes. There are several potential explanations for these phenomena: (i) For the genes working in the same pathway, some of them might be positive regulators and others might be negative regulators; therefore, their effects could be different. (ii) Even the factors work in the same pathway and regulate the process in the same direction, and the RNAi or mutation of these genes might cause different effects. For example, the reduction of one gene could lead to the increase in activity of another gene product in the same pathway. Therefore, interpreting a phenotype needs a case-by-case analysis. (iii) Although some gene products work in the same pathway, each gene could have its own specific functions independent on its functions in this pathway.

Mitochondria have diverse morphology in different tissues. However, their regulations were largely conserved. The tissue-specific regulators of mitochondrial morphology usually have tissue-specific expression pattern, such as fzo (36). In this study, we used fly fat body as a model system to identify the regulators for mitochondrial morphology. Some regulators that we identified here might have tissue-specific functions. Because most hits have broad expression patterns, most of them likely play similar roles in other tissues.

In this study, we found that the lack of Dhpr led to muscle degeneration, TH neuron loss, and locomotive defects that were very similar to those observed with the loss of Pink1/park. In some patients, Dhpr mutation causes movement disorders and psychiatric disorders similar to PD (37). Dhpr is the key enzyme that catalyzes the recycling of BH4, a cofactor required for DOPA synthesis. The loss of Dhpr leading to mitochondrial defects was an unexpected result. Mitochondria became swollen and had less cristae. We found that the catalytic activity of Dhpr is critical for its mitochondrial functions. Further reduction of BH4 by knocking down the expression of Pu, the key enzyme for de novo BH4 biosynthesis, enhanced the mitochondrial defects caused by the reduction of Dhpr. The lack of obvious mitochondrial phenotypes for Pu RNAi alone tissues is probably due to insufficient knockdown efficiency. BH4 functions as a cofactor to produce NO and synthesizes the precursors of dopamine and serotonin. We found that the reduction of Nos, the NO synthase, but not hn, ple, or Trh, could enhance the mitochondrial defects caused by Dhpr RNAi. In addition, the loss of Dhpr reduced the S-nitrosylation of Drp1, a modification mediated by NO. This suggests that Dhpr probably regulates Drp1 activity by modulating NO synthesis (fig. S10). S-nitrosylation is frequently dysregulated in disease and aging (38). The steady-state concentration of protein S-nitrosylation was maintained by the equilibration between the rates of S-nitrosylation and denitrosylation of the protein. The excessive S-nitrosylation of Drp1 could be induced by β-amyloid (Aβ) protein oligomers and other pathological conditions (39). Our data suggested that certain amount of Drp1 S-nitrosylation is required during physiological conditions. The RNAi of Nos alone only reduces the Nos RNA level by 40% (fig. S9P), which may explain why there are no obvious mitochondrial defects in the Nos RNAi alone tissues. Mutation on the S-nitrosylation site of Drp1 abolished Drp1 activity, suggesting that this modification is critical. It is possible that the ectopically expressed Drp1 could still be modified by NO produced by the remaining Dhpr activity in Dhpr RNAi tissues. Our data also suggested that Pink1/park probably functions in parallel with Dhpr. Pink1 or park overexpression partially rescued Dhpr RNAi-induced mitochondrial defects, probably by affecting mitochondrial fusion and fission or regulating mitophagy (fig. S10). Further efforts are needed to dissect whether Dhpr participates in mitophagy under physical conditions. The reduction of Dhpr activity leads to multiple human diseases. It would be interesting to investigate whether mitochondrial defects contribute to disease progression and whether increasing Drp1 or Pink1/Parkin activity could be beneficial treatments.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Fly strains and RNAi screen strategies

The transgenic RNAi files were ordered from TsingHua Fly Center (THFC; Beijing, China), which is the same RNAi collection as the TRiP collection. Marf (BL: 31157), Pink1 (BL: 31170), and park (BL: 31259) RNAi lines were missing in THFC collections; we therefore ordered those lines from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) and mixed them into the collection, coded them randomly, and screened them without knowing the genotypes. The other fly strains used in this study were UAS-Drp1 (BL: 51647), UAS-Pink1 (BL: 51648), UAS-ManII-GFP, UAS-GFP-SKL (BL: 28881), UAS-RFP-KDEL (BL: 30909), UAS-MitoGFP (BL: 8442), UAS-Dcr-2 (BL: 24650), gstD1-GFP, Cg-Gal4 (BL: 7011), Ple-Gal4 (BL: 8848), Mef2-Gal4 (BL: 27390), and Pink1[B9] (BL: 34749). The mutant Dhpr (Dhpr17-4 and Dhpr42-5) lines were generated by using the CRISPR-Cas9 technique.

All the flies were raised in a humidified, temperature-controlled incubator (25°C). Two to three males carrying Cg-Gal4 divers were crossed to about 15 virgin females carrying UAS-RNAi transgenes. Six hours after egg laying, flies were transferred to fresh food and the eggs were cultured in the incubator for 90 hours. Fat body tissues were dissected for further analysis.

The screen was conducted in three rounds in a double blind manner. For the first two rounds, at least two biological replicas for each genotype were examined each time. The hits from the first round were retested by independent researchers in the second round. For some samples, if the results from the first and second rounds are different, the third-round analysis was done and at least four biological replicas were examined. Only the ones that have been confirmed twice to have aberrant mitochondrial morphology during the screen were listed as positive hits.

Molecular cloning

Drp1 cDNA was cloned into the pUAS attB vector with a C-terminal 3× HA tag. Dhpr cDNA was cloned into the pUAS attB vector with a C-terminal V5 tag. DhprG16D- and Drp1C643A-expressing vectors were generated by site-directed mutagenesis. Park cDNA was cloned into the pUAS attB vector with a C-terminal V5 tag. Marf cDNA was cloned into the pUAS attB vector with a C-terminal 6× Myc tag. QDPR cDNA was cloned into the pEGFP-N1 vector. To generate Dhpr genomic rescue construct, Dhpr genomic DNA fragment with its upstream and downstream 1-kb sequences were cloned into the pattB vector, and a V5 tag was inserted before the stop codon of Dhpr coding sequence.

Biotin-switch assay

To analyze the level of SNO-Drp1, the biotin-switch assay was performed as described previously (40). Briefly, the adult fly thoraxes were dissected and homogenized in HEN buffer [250 mM Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.7), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mM neocuproine]. Then, the free thiols in the tissue extracts were blocked with 20 mM methyl methanethiosulfonate (64306, Sigma) for 20 min at 50°C, and tissue extracts were precipitated with acetone. The pellets were harvested and resuspended in HEN buffer with 1% SDS. SNO was selectively reduced by ascorbate to reform the thiol group and subsequently biotinylated with N-[6-(biotinamido)hexyl]-3′-(2′pyridyldithio)-propionamide] (A35390, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The biotinylated proteins were pulled down with streptavidin-agarose beads (S1638, Sigma). Drp1 was detected by Western blotting with anti-Drp1 antibody (8570S, Cell Signaling Technology). Drp1-3HA and Drp1C643A-3HA were detected by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody (3724S, Cell Signaling Technology). Relative levels of S-nitrosylated proteins were determined by a comparison of S-nitrosylated Drp1 to the total amount of Drp1 in the extract for each sample.

Bioinformatic analysis and statistics

We queried available databases that contained information on protein-protein interactions, genetic interactions, two-hybrid interactions, text mining, and other data. We further used the online software COMPLEAT and the KEGG pathway analysis to identify the protein complexes (18). We also performed extensive data mining and manually added proteins missed in the COMPLEAT analysis into complexes.

The classification of hits was judged by the similarity of the mitochondrial morphology, complex analysis, and genetic network. According to precious studies (18), complex analysis was performed by using the online software COMPLEAT (www.flyrnai.org/compleat/). Using COMPLEAT, 312 nonredundant protein complexes overrepresented among the genes were scored comparing to the experimental background with a P value cutoff of 0.05. An interaction matrix was first established among all genes scored in the screen, and then the resulting network was visualized by the software Cytoscape.

The statistical analysis was performed using Prism 5 (GraphPad). The results were analyzed by the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test, one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test, χ2 (and Fisher’s exact) test, and log-rank test, as indicated in the figure legends. All the results were presented as mean values + SEM. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

For confidence of identified genes from the screen, if the RNAi lines were predicted with no off-target effects or if two or more independent RNAi lines have similar phenotypes, we considered the genes to be high-confidence hits. If the RNAi lines were predicted with potential off-target effects or phenotypes only exist in one RNAi line but not in the other, and the corresponding genes were co-complexed with high-confidence hits, we considered the genes to be medium-confidence hits. If the RNAi lines were predicted with potential off-target effects and the gene is not co-complex with high-confidence hits, we considered them as low-confidence hits. The confidence of identified genes is listed in table S2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to THFC, BDSC, and DGRC (Drosophila Genetic Resource Center) for providing fly strains and cDNA clones. Funding: C.T. was supported by the National Key Research & Developmental Program of China (2017YFC1001500 and 2017YFC1001100); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31622034, 31571383, and 91754103); the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (LR16C070001); the National Basic Research Program of China (2014CB943100); and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. L.W. was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (LY19H040014). Author contributions: C.T., J.Zho., L.X., X.D., W.L., X.Z., X.W., J.Zha., and L.W. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. C.T. obtained financial support and was responsible for the study design and the interpretation of results. H.Y., L.J., X.F., and J.B. conducted fly screen. W.S. performed the TEM analysis. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/9/eaax0365/DC1

Supplementary Materials and Methods

Fig. S1. The complex analysis of the hits from the mitochondrial morphology screening.

Fig. S2. The mitochondrial morphology in the fat body tissues with indicated gene RNAi is shown.

Fig. S3. Sixteen genes encoding proteasome components were identified in this mitochondrial morphology screening.

Fig. S4. Twenty-seven genes encoding spliceosome components were identified in this mitochondrial morphology screening.

Fig. S5. The reduction of the enzymes involved in tyrosine and lysine metabolism led to abnormal mitochondrial morphology.

Fig. S6. Loss of Dhpr leads to the reduction of life span and increase of the ROS production.

Fig. S7. The overexpression of Pink1 or park partially rescues muscle defects caused by Dhpr RNAi.

Fig. S8. The genetic interaction between Dhpr and genes whose products consume or produce BH4.

Fig. S9. The genetic interaction between Dhpr and other core machinery of mitochondrial fusion and fission.

Fig. S10. The model of how Dhpr regulates mitochondrial morphology.

Table S1. The list of the RNAi lines used in this screening and their corresponding genes.

Table S2. The annotation of the phenotypes and the quantification data.

Table S3. The list of genes that had two or three independent RNAi lines and genes that had been reported to be involved in regulating mitochondria.

Table S4. The list of protein complexes required for mitochondrial morphology maintenance.

Table S5. The lists of genes encoding spliceosome, proteasome, and electron transfer chain components that have been identified in this screen.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Mishra P., Chan D. C., Mitochondrial dynamics and inheritance during cell division, development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 634–646 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nunnari J., Suomalainen A., Mitochondria: In sickness and in health. Cell 148, 1145–1159 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y., Liu X., Bai J., Tian X., Zhao X., Liu W., Duan X., Shang W., Fan H.-Y., Tong C., Mitoguardin regulates mitochondrial fusion through MitoPLD and is required for neuronal homeostasis. Mol. Cell 61, 111–124 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickles S., Vigie P., Youle R. J., Mitophagy and quality control mechanisms in mitochondrial maintenance. Curr. Biol. 28, R170–R185 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra P., Chan D. C., Metabolic regulation of mitochondrial dynamics. J. Cell Biol. 212, 379–387 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perkins L. A., Holderbaum L., Tao R., Hu Y., Sopko R., McCall K., Yang-Zhou D., Flockhart I., Binari R., Shim H.-S., Miller A., Housden A., Foos M., Randkelv S., Kelley C., Namgyal P., Villalta C., Liu L.-P., Jiang X., Huan-Huan Q., Wang X., Fujiyama A., Toyoda A., Ayers K., Blum A., Czech B., Neumuller R., Yan D., Cavallaro A., Hibbard K., Hall D., Cooley L., Hannon G. J., Lehmann R., Parks A., Mohr S. E., Ueda R., Kondo S., Ni J.-Q., Perrimon N., The Transgenic RNAi Project at Harvard Medical School: Resources and validation. Genetics 201, 843–852 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verstreken P., Ly C. V., Venken K. J., Koh T. W., Zhou Y., Bellen H. J., Synaptic mitochondria are critical for mobilization of reserve pool vesicles at Drosophila neuromuscular junctions. Neuron 47, 365–378 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandoval H., Yao C. K., Chen K., Jaiswal M., Donti T., Lin Y. Q., Bayat V., Xiong B., Zhang K., David G., Charng W. L., Yamamoto S., Duraine L., Graham B. H., Bellen H. J., Mitochondrial fusion but not fission regulates larval growth and synaptic development through steroid hormone production. eLife 3, e03558 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McQuibban G. A., Lee J. R., Zheng L., Juusola M., Freeman M., Normal mitochondrial dynamics requires rhomboid-7 and affects Drosophila lifespan and neuronal function. Curr. Biol. 16, 982–989 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi S.-Y., Huang P., Jenkins G. M., Chan D. C., Schiller J., Frohman M. A., A common lipid links Mfn-mediated mitochondrial fusion and SNARE-regulated exocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1255–1262 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagaraj R., Gururaja-Rao S., Jones K. T., Slattery M., Negre N., Braas D., Christofk H., White K. P., Mann R., Banerjee U., Control of mitochondrial structure and function by the Yorkie/YAP oncogenic pathway. Genes Dev. 26, 2027–2037 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song Z., Chen H., Fiket M., Alexander C., Chan D. C., OPA1 processing controls mitochondrial fusion and is regulated by mRNA splicing, membrane potential, and Yme1L. J. Cell Biol. 178, 749–755 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darshi M., Mendiola V. L., Mackey M. R., Murphy A. N., Koller A., Perkins G. A., Ellisman M. H., Taylor S. S., ChChd3, an inner mitochondrial membrane protein, is essential for maintaining crista integrity and mitochondrial function. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 2918–2932 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S., Reuveny A., Volk T., Nesprin provides elastic properties to muscle nuclei by cooperating with spectraplakin and EB1. J. Cell Biol. 209, 529–538 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stowers R. S., Megeath L. J., Górska-Andrzejak J., Meinertzhagen I. A., Schwarz T. L., Axonal transport of mitochondria to synapses depends on milton, a novel Drosophila protein. Neuron 36, 1063–1077 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo M., Drosophila as a model to study mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, a009944 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeng X., Han L., Singh S. R., Liu H., Neumuller R. A., Yan D., Hu Y., Liu Y., Liu W., Lin X., Hou S. X., Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies networks involved in intestinal stem cell regulation in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 10, 1226–1238 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vinayagam A., Hu Y., Kulkarni M., Roesel C., Sopko R., Mohr S. E., Perrimon N., Protein complex-based analysis framework for high-throughput data sets. Sci. Signal. 6, rs5 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.San Francisco B., Bretsnyder E. C., Kranz R. G., Human mitochondrial holocytochrome c synthase’s heme binding, maturation determinants, and complex formation with cytochrome c. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E788–E797 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noree C., Sato B. K., Broyer R. M., Wilhelm J. E., Identification of novel filament-forming proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Biol. 190, 541–551 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iyengar B., Luo N., Farr C. L., Kaguni L. S., Campos A. R., The accessory subunit of DNA polymerase gamma is essential for mitochondrial DNA maintenance and development in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 4483–4488 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alonso J., Rodriguez J. M., Baena-López L. A., Santarén J. F., Characterization of the Drosophila melanogaster mitochondrial proteome. J. Proteome Res. 4, 1636–1645 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du J., Yuan Z., Ma Z., Song J., Xie X., Chen Y., KEGG-PATH: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes-based pathway analysis using a path analysis model. Mol. Biosyst. 10, 2441–2447 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geisler S., Vollmer S., Golombek S., Kahle P. J., The ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes UBE2N, UBE2L3 and UBE2D2/3 are essential for Parkin-dependent mitophagy. J. Cell Sci. 127, 3280–3293 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Werner E. R., Blau N., Thony B., Tetrahydrobiopterin: Biochemistry and pathophysiology. Biochem. J. 438, 397–414 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu Z., Ren M., Wang Z., Zhang B., Rong Y. S., Jiao R., Gao G., Highly efficient genome modifications mediated by CRISPR/Cas9 in Drosophila. Genetics 195, 289–291 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen C.-L., Hu Y., Udeshi N. D., Lau T. Y., Wirtz-Peitz F., He L., Ting A. Y., Carr S. A., Perrimon N., Proteomic mapping in live Drosophila tissues using an engineered ascorbate peroxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 12093–12098 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calvo S. E., Clauser K. R., Mootha V. K., MitoCarta2.0: An updated inventory of mammalian mitochondrial proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D1251–D1257 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smooker P. M., Howells D. W., Cotton R. G., Identification and in vitro expression of mutations causing dihydropteridine reductase deficiency. Biochemistry 32, 6443–6449 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng H., Dodson M. W., Huang H., Guo M., The Parkinson’s disease genes pink1 and parkin promote mitochondrial fission and/or inhibit fusion in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14503–14508 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y., Ouyang Y., Yang L., Beal M. F., McQuibban A., Vogel H., Lu B., Pink1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics through interaction with the fission/fusion machinery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 7070–7075 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho D.-H., Nakamura T., Fang J., Cieplak P., Godzik A., Gu Z., Lipton S. A., S-nitrosylation of Drp1 mediates β-amyloid-related mitochondrial fission and neuronal injury. Science 324, 102–105 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J.-L., The cytoophidium and its kind: Filamentation and compartmentation of metabolic enzymes. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 32, 349–372 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]