ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To synthesize data about the prevalence of sexual violence (SV) among refugees around the world.

METHODS

A systematic review was conducted from the search in seven bibliographic databases. Studies on the prevalence of SV among refugees and asylum seekers of any country, sex or age, whether in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese, were eligible.

RESULTS

Of the 2,906 titles found, 60 articles were selected. The reported prevalence of SV was largely variable (0% to 99.8%). Reports of SV were collected in all continents, with 42% of the articles mentioning it in refugees from Africa (prevalence from 1.3% to 100%). The rape was the most reported SV in 65% of the studies (prevalence from 0% to 90.9%). The main victims were women in 89% of the studies, all the way, especially when still in the countries of origin. The SV was perpetrated particularly by intimate partners, but also by agents of supposed protection. Few studies have reported SV in men and children; the prevalence reached up to 39.3% and 90.9%, respectively. Approximately one-third of the studies (32%) were carried out in refugee camps and more than half (52%) in health services using mental health assessment tools. No study has addressed the most recent migratory crisis. Meta-analysis was not performed due to the methodological heterogeneity of the studies.

CONCLUSIONS

SV is a prevalent problem affecting refugees of both sexes, of all ages, throughout the migratory journey, particularly those from Africa. Protection measures are urgently needed, and further studies, with more appropriate tools, may better measure the current magnitude of the problem.

Keywords: Refugees, Sex Offenses, Rape, Review, Prevalence

INTRODUCTION

The world is currently experiencing the biggest migratory crisis since World War II, with an increasing number of refugees. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) report, 65.6 million people were forced to move because of persecution, conflict, widespread violence or human rights violations in 2016. Of these, 22.5 million were refugees; 2.8 million, asylum seekers; and 40.3 million, internally displaced persons within their own countries1.

Sexual violence (SV), defined as a sexual act or attempt to obtain a sexual act without the voluntary consent of the victim or with someone unable to consent or refuse2, is considered a present threat during forced displacement and the search for asylum3,4. In times of war, women and girls are more vulnerable to rape and are at greater risk for other forms of SV, such as early or forced marriage, intimate partner abuse, child sexual abuse, sexual exploitation and trafficking4. SV has also been perpetrated against men and boys as a tactic of war or during detention and interrogation5; they may suffer rape, sexual torture, mutilation, humiliation, enslavement, and forced incest6. This risk persists during the escape journey and after the reception in apparently safe destinations7.

The consequences can be extremely serious. In women, it can lead to mental disorders, obstetric complications, sexual dysfunctions, unwanted pregnancies, unsafe abortions and sexually transmitted infections8,9. Among men, in addition to infections and mental disorders, sexual dysfunction, somatic complaints, sleep disorders, withdrawal from relationships, attempted suicide, alcohol and drug abuse, and violent behavior are common8,10. In childhood, sexual abuse may also be accompanied by guilt, shame, eating disorders, cognitive distortions, mental disorders, sexual and relationship problems, and school absenteeism11.

Two previous systematic reviews have portrayed SV in refugees and internally displaced persons in emergency humanitarian complexes12,13: a meta-analysis aimed at estimating its prevalence in women only12, and other aimed at quantifying gender-based violence in three categories: physical violence, by intimate and sexual partner13. Neither analyzed the different types, profile of perpetrators and the moment of occurrence of SV in the migratory process. No studies have been conducted on the prevalence of this violence in the total refugee population (children, adults and older adults of both sexes) in different scenarios and moments of their trajectory, for a more comprehensive understanding of the magnitude of the problem.

Thus, we aim to synthesize the literature on the prevalence of SV in refugees around the world through a systematic review, regardless of sex, age and location. With this knowledge, one may better identify the profile of refugees who are victims of SV, contributing to specific prevention, approach, treatment and monitoring strategies in the countries of origin, during migration and in the host countries.

METHODS

The bibliographic search was carried out in January 2018, using the MEDLINE (via Ovid), Embase (via Ovid), PsycINFO (via Ovid), Scopus, Web of Science, Sociological Abstracts (via ProQuest) and LILACS (via VHL) databases. No date limits or language restrictions were applied. Search strategies have involved the following MeSH and free terms: “refugee,” “asylum seek,” “exiled,” “refugee camps,” “sexual violence,” “sexual harassment,” “child abuse,” “sexual offense,” “sexual abuse,” “sexual crime,” “rape,” “sexual coercion,” “sexual assault.” Articles addressing any form of SV were included, using the connector “OR.” For the calculation by type of SV, we use the definition described in each of the articles. The search strategy is detailed in Appendix A. Articles within the bibliographic reference lists of the review studies and those included in this study were added where applicable.

Studies with data available for calculating the prevalence of SV in refugees or asylum seekers (considered as single population) in any country, sex or age, and published in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese were eligible. Chapters of books, dissertations, annals of congresses, editorials, letters, notes and comments were not included.

The selection of studies was initially conducted through the search of titles and abstracts; then by reading the full texts. Decisions on study eligibility and data extraction were performed by two independent reviewers on electronic forms constructed in EpiData 3.1 (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark), and the differences were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer. References were managed in EndNote Web software [Thomson Reuters (SCIENTIFIC), NY, USA].

Information was collected on: (1) study methods and population; (2) prevalence of SV according to sex, age, type of SV, continent/region/country of origin, host country/region, period of occurrence and profile of perpetrators.

In studies that presented additional categories of migrants (e.g. economic migrants), only information on refugees and asylum seekers was used. Likewise, in studies that reported psychological, physical and sexual violence, only SV data were used.

The calculation of global prevalence was estimated from the information on the total cases of the studies. For the calculation of specific prevalence, the following types of SV reported by the articles were considered: rape, attempted rape, unwanted sexual contact, non-contact unwanted sexual experience, sexual harassment, sexual abuse, sexual torture, sexual assault, sexual exploitation, including enforced prostitution and sex for survival, genital mutilation, forced marriage and abortion. When only the prevalence by type were informed and more than one of these forms was inflicted on the same victims, it was not possible to estimate the overall prevalence.

RESULTS

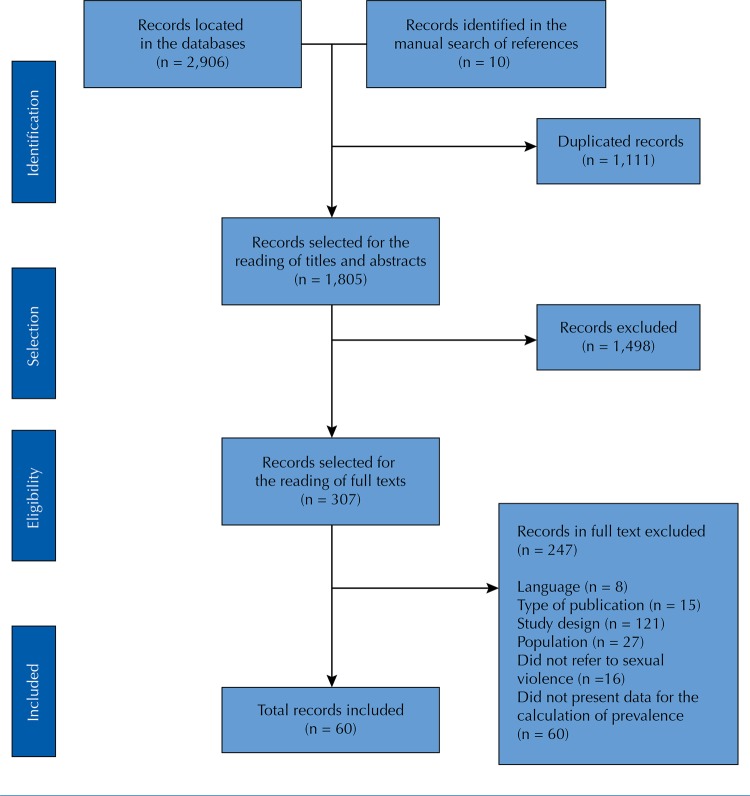

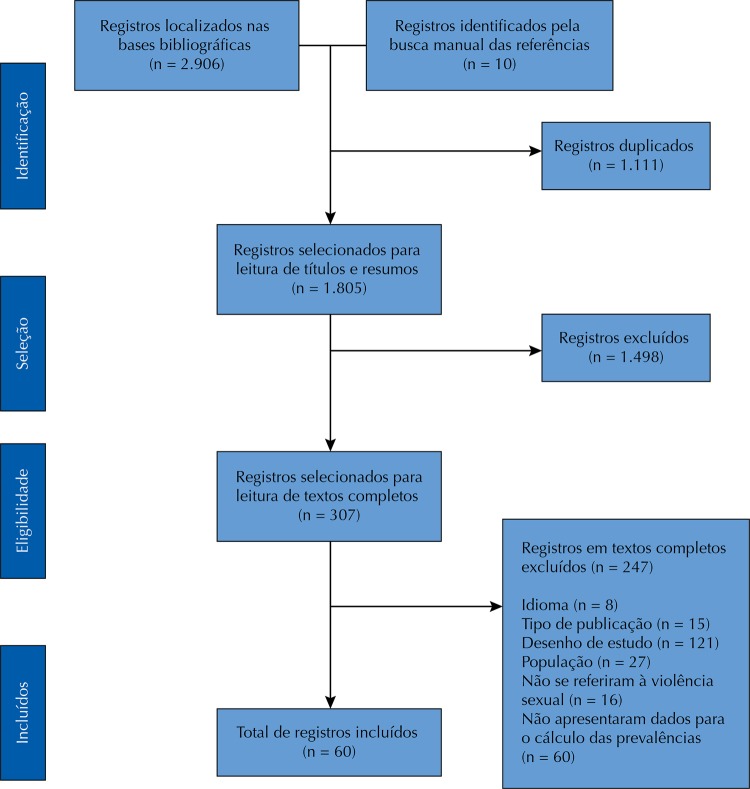

We found 2,906 studies in the databases searched and 10 in the lists of bibliographic references (Figure 1). After the duplicates were removed (n = 1,111), 1,805 studies were selected for the reading of titles and abstracts. Of these, 1,498 were excluded by the following criteria: language (n = 29), type of publication (comments, letters, books, notes, editorials, abstracts of lectures and dissertations, n = 361), study design (most qualitative or review studies, n = 521), population not composed of refugees or asylum seekers (n = 176), out of scope (did not address SV, n = 131) or both (population and scope, n = 280).

Figure 1. Flowchart for the selection of studies included in the systematic review.

Three hundred and seven studies were selected for the reading of full texts. After the application of the eligibility criteria, 60 studies were included for data extraction. Of the excluded ones, 15 were not original articles, 121 were review studies or with qualitative design and in 27 studies the population was not formed by refugees or asylum seekers.

Characteristics of the Studies and their Populations

The 60 articles selected were all published in English between 1990 and 2017 (45% between 2000 and 2010) and from 31 different countries (14 from the USA). Studies were of cross-sectional design (Table 1), except for two cohort studies48,73.

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review and prevalence of sexual violence. (n = 60).

| First author and year of study | Country(ies)/ host region | Data collection location | Period of data collection | Instrument of study | Sampling (n) | Mean age of sample (years) | Female proportion (%) | Global SV prevalence (%)* | Prevalence of SV by sex | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Start | End | Female | Male | ||||||||

| Allodi14 (1990) | Canada | USS | 1979 | 1985 | NI | 56 | NI | 50.0 | NI | 64.3 | 39.3 |

| Fornazzari15 (1990) | Canada | USS | NI | NI | Collection in records | 36 | 37 | 100.0 | 22.2 | 22.2 | NA |

| Mckelvey16 (1995) | Philippines | USS | NI | NI | RQ | 102 | NI | 33.3 | 9.8 | 8.8 | 10.3 |

| Peel17 (1996) | United Kingdom | USS and detention centers | 1993 | 1994 | Collection in records | 92 | NI | 21.7 | 33.7 | 80 | 20.8 |

| Frljak18 (1997) | Bosnia and Herzegovina | USS | 1993 | 1994 | Collection in records | 241 | NI | 100.0 | 3.3 | 3.3 | NA |

| Silove19 (1998) | Australia | NI | NI | NI | HTQ | 96 | NI | NI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Gorst-Unsworth20 (1998) | United Kingdom | USS | NI | NI | HTQ | 84 | 39 | 0.0 | 14.3 | NA | 14.3 |

| Loutan21 (1999) | Switzerland | USS | 1993 | 1994 | HTQ | 573 | 27 | 36.3 | 2.3 | NI | NI |

| Blair22 (2000) | USA | USS and households | 1991 | 1991 | WTS | 124 | 37 | 60.5 | 5.6 | NI | NI |

| Hondius23 (2000) | Netherlands | USS | NI | NI | NI | 156 | NI | 34 | 23.1 | 26.4 | 21.4 |

| Petersen24 (2000) | Thailand | RC | 1999 | 1999 | RQ | 129 | 36 | 37.2 | NI | 6.3 | NI |

| Iacopino25 (2001) | Macedonia and Albania | RC | 1999 | 1999 | RQ | 11,458 | NI | NI | 0.03 | NI | NI |

| Tang26 (2001) | Gambia | RC | 1999 | 1999 | HTQ | 80 | 41.3 | 48.8 | 1.3 | NI | NI |

| Crescenzi27 (2002) | India | Villages | 1995 | 1995 | HTQ | 150 | NI | 37.3 | NI | NI | NI |

| Sabin28 (2003) | Mexico | RC | 2000 | 2000 | HTQ | 170 | 37.9 | 58.2 | 3.5 | NI | NI |

| Cardozo29 (2004) | Thailand | RC | 2001 | 2001 | HTQ | 495 | NI | 57.4 | NI | 2.8 | 2.9 |

| Sesay30 (2004) | Sierra Leone | RC and villages | 2001 | 2011 | RQ | 400 | NI | 100.0 | 11.3 | 11.3 | NA |

| Thomas31 (2004) | United Kingdom | NI | NI | NI | NI | 100 | 16 | 41 | 32 | 63.4 | 10.2 |

| Asgary32 (2006) | USA | USS | 1998 | 2002 | Istanbul Protocol | 89 | 34 | 13.5 | NI | NI | NI |

| Avdibegovic33 (2006) | Bosnia and Herzegovina | USS and RC | 2000 | 2002 | Modified DVI | 50 | NI | 100.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 | NA |

| Bradley34 (2006) | United Kingdom | USS | NI | NI | NI | 97 | 30 | 14.4 | 8.2 | 28.6 | 2.4 |

| Schweitzer35 (2006) | Australia | Community | 2003 | 2003 | HTQ | 63 | 34.2 | 33.3 | 11.1 | 19 | 7.1 |

| Olsen36 (2006) | Denmark | USS | 1991 | 1994 | RQ | 221 | 35.6 | 12.7 | 11.3 | NI | NI |

| Bogner37 (2007) | England | USS | 2004 | 2005 | RQ | 27 | NI | 59.3 | 55.6 | 68.8 | 36.4 |

| Edston38 (2007) | Sweden | USS | 1993 | 2005 | NI | 63 | 28 | 100.0 | 76.2 | 76.2 | NA |

| Hammoury39 (2007) | Lebanon | USS | 2005 | 2005 | AAS | 349 | 28 | 100.0 | 26.4 | 26.4 | NA |

| Hooberman40 (2007) | USA | USS | 2000 | 2003 | HTQ | 325 | 33.5 | 38.8 | 28.9 | NI | NI |

| John-Langba41 (2007) | Botswana | RC | NI | NI | SGBV | 402 | 29.2 | 100.0 | 99.8 | 99.8 | NA |

| Kira42 (2007) | USA | NI | NI | NI | CTS | 501 | 35.7 | 45.3 | 1.2 | NI | NI |

| Piwowarczyk43 (2007) | USA | USS | 1999 | 2002 | NI | 134 | 34 | 65.7 | 50.0 | NI | NI |

| Chang44 (2008) | USA | USS | 2001 | 2001 | NI | 243 | 10.6 | 51.9 | 4.9 | NI | NI |

| Nagai45 (2008) | Uganda | RC and villages | 1999 | 2000 | RQ | 1,216 | NI | 78.0 | NI | 18.1 | 16.9 |

| Harrison46 (2009) | Uganda | RC and villages | 2006 | 2006 | BSS | 1,158 | NI | 52.4 | NI | 3.8 | NI |

| Mitike47 (2009) | Ethiopia | RC | 2004 | 2004 | RQ | 288 | NI | 100.0 | 42.4 | 42.4 | NA |

| Williams48 (2010) | United Kingdom | USS | 2005 | 2005 | NI | 178 | 30.4 | 35.4 | 25.8 | 54.0 | 10.4 |

| Schubert49 (2011) | Finland | USS | NI | NI | HTQ | 78 | 37.6 | 37.2 | NI | NI | NI |

| Tamblym50 (2011) | USA | USS | 2004 | 2007 | HTQ modified | 58 | 34.7 | 29.3 | 20.7 | NI | NI |

| Bogic51 (2012) | Germany, Italy and United Kingdom | Households and communities | 2005 | 2006 | LSC | 854 | 41.6 | 51.3 | 5.2 | NI | NI |

| Kira52 (2012) | USA | NI | 2006 | 2006 | CTS | 209 | NI | 0.0 | 90.9 | NI | NI |

| Parmar53 (2012) | Republic of Cameroon | Villages | 2010 | 2010 | NI | 191 | 35.1 | 100.0 | 40.8 | 40.8 | NA |

| Black54 (2013) | USA | USS and Community | 2004 | 2004 | CREV SECV | 196 | 13.8 | 45.9 | 4.6 | NI | NI |

| Falb55 (2013) | Thailand | RC | 2008 | 2008 | RHA | 861 | 30.1 | 100.0 | NI | NI | NA |

| Tufan56 (2013) | Turkey | USS | 2005 | 2007 | SLESQ | 67 | 30.6 | 41.8 | 20.9 | 46.4 | 2,6 |

| Gibson-Helm57 (2014) | Australia | USS | 2002 | 2011 | NI | 1,279 | NI | 100.0 | 5.7 | 5.7 | NA |

| Idemudia58 (2014) | Polokwane, South Africa | City | NI | NI | RQ | 125 | 28.3 | 42.3 | NI | NI | NI |

| Morof59 (2014) | Uganda | NI | 2010 | 2010 | HTQ RQ | 117 | 31.6 | 100.0 | 71.8 | 71.8 | NA |

| Bell60 (2015) | Ruanda | RC | 2008 | 2008 | RHA toolkit | 810 | 29 | 100.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | NA |

| Connor61 (2015) | USA | Community | NI | NI | RQ | 30 | 31.8 | 100.0 | 93.3 | 93.3 | NA |

| Sipsma62 (2015) | Ruanda | RC | NI | NI | RHA toolkit | 548 | 32 | 100.0 | 38.1 | 38.1 | NA |

| Al-Modallal63 (2016) | Jordan | RC | NI | NI | AAS | 238 | 32.7 | 100.0 | 21.0 | 21.0 | NA |

| Chu64 (2016) | USA | Communities and households | 2014 | 2014 | RQ | 15 | NI | 100.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | NA |

| Lerner65 (2016) | USA | USS | 2010 | 2013 | RQ | 267 | 34 | 33.0 | 33.3 | NI | NI |

| Um66 (2016) | South Korea | NI | 2010 | 2010 | CTS2 | 180 | 39.8 | 100.0 | 25.6 | 25.6 | NA |

| Wirtz67 (2016) | Ethiopia | RC | 2012 | 2012 | ASIST-GBV | 487 | NI | 100.0 | NI | NI | NA |

| Gušić68 (2017) | Sweden | Schools USS | NI | NI | WRGTI | 77 | NI | 35.0 | 12.0 | NI | NI |

| Hopkinson69 (2017) | USA | USS | 2008 | 2013 | HTQ RQ | 61 | 28.8 | 37.7 | 62.3 | NI | NI |

| Logie70 (2017) | Canada | Communities and social networks | 2013 | 2015 | RQ | 42 | NI | 100.0 | 52.0 | 52.0 | NA |

| Riley71 (2017) | Bangladesh | RC | NI | NI | HTQ | 148 | 34 | 52.8 | 13.0 | NI | NI |

| Stark72 (2017) | Ethiopia | RC | 2015 | 2015 | NI | 919 | 14.6 | 100.0 | 65.3 | 65.3 | NA |

| Wright73 (2017) | USA | Agencies of settlement | 2011 | 2012 | HTQ | 298 | NI | 45.0 | NI | 1.5 | NI |

SV: sexual violence; NA: not applicable; NI: not informed; RC: refugee camps; USA: Unites States of America; USS: health services units; RQ: research questionnaire; HTQ: Harvard Trauma Questionnaire; STAR: Resettlement Stressor Scale; WTS: War Trauma Scale; DVI: Domestic Violence Inventory; AAS: Abuse Assessment Screen; SBGV: Sexual and Gender-based Violence Scale; CTS: Revised Conflict Tactics Scales; CREV: Children’s Report of Exposure to Violence; SECV: Survey of Exposure to Community Violence; BSS: Behavioral Surveillance Surveys Questionnaire; SLESQ: Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire; LEC: Life Events Checklist; ASIST-GBV: Assessment Screen to Identify Survivors Toolkit for Gender Based Violence; LSC: Life Stressor Checklist; RHA: Reproductive Health Assessment; WRGTI: War/refugee and general trauma inventory

* The global prevalence of SV was calculated from the total number of cases reported by the studies or, when there was no such information, by the total sum of the specific cases reported (e.g. cases of rape, sexual harassment, etc.). However, in five studies32,49,55,58,67, the global prevalence could not be estimated since the authors did not report the total number of cases. It was not possible to calculate it from the sum of the typified prevalence because there were victims who suffered more than one type of SV, which would overestimate the calculation of the global prevalence.

The most frequent sites of data collection, according to the 54 articles that contained this information, were health services (n = 28.52%) and refugee camps (n = 17.32%). Most studies (87%) were conducted to evaluate outcomes in mental health, without the main objective of measuring the prevalence of SV cases. Among the 49 studies that informed the instrument used, the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) was the most frequently validated instrument (n = 15, corresponding to 31%), while 29% (n = 14) used questionnaires designed specifically for the research.

Studies involved 28,101 refugees and asylum seekers. The population of each study varied between 15 and 11,458 individuals. In 33% (n = 20) of the studies, the sample included less than 100 people, and in 18% (n = 11), more than 500 people. The mean age of participants ranged from 10.6 to 41.6 years old; 42% (n = 25) of the studies included those younger than 18 years. There was a general predominance of women; in 37% (n = 21) of the studies, the sample was exclusively female. The predominant religion was Muslim, in 12 (63%) of the 19 studies with data about it.

Prevalence of Sexual Violence

The global prevalence variation presented a large amplitude, regardless of the sample size: from 0% to 99.8%, with a total of 2,859 cases of SV. In 15 studies (31%), the prevalence was less than 10% (samples from 80 to 11,458 people), and in 11 (23%), more than 50% (samples from 15 to 919 people), as shown in Table 1. This wide variation occurred independently of the data collection scenario – in refugee camps (n = 12, 0.03% to 99.8%), health units (n = 25, 2.3% to 76.2%) and communities/villages (n = 6, 5.2% to 93.3%) – and assessing form – validated instruments (n = 25%; 0.0% to 99.8%) or questionnaires of the own research (n = 14; 0.03% to 93.3%).

Six studies reported SV in children and adolescents, with prevalence varying between 4.6% and 90.9%16,44,47,52,54,72. In 32 of the 36 (89%) studies that showed prevalence by sex, the main victims were women. Of these, 12 studies reported SV in both sexes, with a difference of up to 59.2% more of prevalence in women17. Two studies reported the opposite, but with disparities less than 2%16,29. In men, the prevalence reached 39.3%14.

Africa was the most frequent continent of origin in 13 (42%) of the 31 studies with information about it (Table 2). As to the moment of occurrence, approached by 18 studies, 17 (94%) reported that SV occurred in the country of origin (prevalence between 1% and 92%); in two studies (11%), it occurred during the course (prevalence of 5.2% in both)53,68; and two (11%) reported SV at the host site (prevalence of 39% in Cameroon53 and 46.1% in Uganda59).

Table 2. Prevalence of sexual violence in refugees according to place of origin. (n = 31).

| Continent(s) of origin | Region of origin | Country of origin | First author and year of study | Sampling (n) | Prevalence of SV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa (n = 13) | NI | NI | Thomas31 (2004) | 65 | 24.6 |

| NI | NI | Chu64 (2016) | 15 | 60.0 | |

| Central Africa | RDC | Peel17 (1996) | 92 | 33.7 | |

| RDC | Edston38 (2007) | 3 | 100.0 | ||

| Central African Republic | Parmar53 (2012) | 77 | 57.1 | ||

| RDC | Bell60 (2015) | 810 | 8.0 | ||

| RDC | Sipsma62 (2015) | 548 | 38.1 | ||

| West Africa | Senegal | Tang26 (2001) | 80 | 1.3 | |

| Sierra Leone | Sesay30 (2004) | 400 | 11.3 | ||

| NI | Gibson-Helm57 (2014) | 45 | 6.7 | ||

| North Africa | Sudan | Schweitzer35 (2006) | 63 | 11.1 | |

| Sudan and South Sudan | Stark72 (2017) | 919 | 65.3 | ||

| NI | Gibson-Helm57 (2014) | 1,147 | 5.1 | ||

| East Africa | Uganda | Edston38 (2007) | 9 | 66.7 | |

| Somalia | Mitike47 (2009) | 248 | 49.2 | ||

| NI | Gibson-Helm57 (2014) | 87 | 13.8 | ||

| Asia (n = 8) | Southern Asia | Sri Lanka | Silove19 (1998) | 92 | 0.0 |

| Bangladesh | Edston28 (2007) | 13 | 84.6 | ||

| South Asia | Myanmar | Petersen24 (2000) | 129 | 2.3 | |

| Myanmar | Riley71 (2017) | 148 | 13.0 | ||

| Southeastern Asia | Vietnam | McKelvey16 (1995) | 102 | 9.8 | |

| Cambogia | Blair22 (2000) | 124 | 5.6 | ||

| Cambogia | Chang44 (2008) | 243 | 4.9 | ||

| East Asia | North Korea | Um66 (2016) | 180 | 25.6 | |

| Europe Asia Africa (n = 8) | Middle East | NI | Olsen36 (2006) | 221 | 11.3 |

| NI | Wright73 (2017) | 133 | 1.5 | ||

| Europe Asia Africa (n = 8) | Middle East | Iraq | Gorst-Unsworth20 (1998) | 84 | 14.3 |

| Iraq | Kira42 (2007) | 501 | 1.2 | ||

| Iraq | Kira52 (2012) | 209 | 90.9 | ||

| Iraq | Black54 (2013) | 196 | 4.6 | ||

| Iran | Edston38 (2007) | 11 | 45.5 | ||

| Syria | Edston38 (2007) | 3 | 66.7 | ||

| Turkey | Bradley34 (2006) | 97 | 8.2 | ||

| Turkey | Edston38 (2007) | 3 | 100.0 | ||

| NA (n = 2) | Palestine | NA | Hammoury39 (2007) | 349 | 26.4 |

| NA | Al-Modallal63 (2016) | 238 | 21.0 | ||

| America (n = 1) | Central America | Guatemala | Sabin28 (2003) | 170 | 3.5 |

| Europe (n = 1) | Bosnia | Frljak18 (1997) | 241 | 3.3 |

SV: sexual violence; NI: not informed; NA: not applicable; DRC: Democratic Republic of the Congo

The most frequent type of SV was rape (65%) (Table 3). The perpetrators were identified in 18 studies: 10 (55%) reported the occurrence of SV by intimate partner (prevalence from 4.3% to 30%)33,39,45,53,55,59,62,63,66,72, five by military personnel (prevalence from 1% to 74.6%)38,45,55,58,72, four by acquaintances51,53,55,72, four by relatives45,54,58,72, two by unknowns 51,53, two by rebel soldiers 31,53, one by police officers58, one by armed groups72, and one by guards in prison17.

Table 3. Prevalence according to the type of sexual violence in refugees. (n = 51).

| Type of sexual violence | First author and year of study | Continent/region/country of origin | Host country/region | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rape (n = 33) | Allodi14 (1990) | Latin America | Canada | 30.4 |

| Fornazzari15 (1990) | Latin America | Canada | 22.2 | |

| Peel17 (1996) | RDC | United Kingdom | 33.7 | |

| Frljak18 (1997) | Bosnia | Bosnia | 3.3 | |

| Silove19 (1998) | Sri Lanka | Australia | 0.0 | |

| Loutan21 (1999) | Africa, Asia and Europe | Switzerland | 2.3 | |

| Petersen24 (2000) | Myanmar | Thailand | 2.3 | |

| Tang26 (2001) | Senegal | Gambia | 1.3 | |

| Crescenzi27 (2002) | Tibet | India | 0.7 | |

| Cardozo29 (2004) | Myanmar | Thailand | 2.8 | |

| Sesay30 (2004) | Sierra Leone | Sierra Leone | 11.3 | |

| Thomas31 (2004) | Africa, Middle East, Western Europe and Asia | United Kingdom | 32.0 | |

| Asgary32 (2006) | Africa and Asia | USA | 6.7 | |

| Bradley34 (2006) | Turkey | United Kingdom | 1.0 | |

| Schweitzer35 (2006) | Sudan | Australia | 11.1 | |

| Avdibegovic33 (2006) | NI | Bosnia | 34.0 | |

| Bogner37 (2007) | Middle East, Europe, Africa and Latin America | England | 44.4 | |

| Edston38 (2007) | Africa, Asia and Middle East | Sweden | 76.2 | |

| Hammoury39 (2007) | Palestine | Lebanon | 26.4 | |

| Hooberman40 (2007) | Africa, Asia, Europe and Central and South America | USA | 18.2 | |

| Harrison46 (2009) | Africa | Uganda | 2.0 | |

| Williams48 (2010) | Africa and Middle East | United Kingdom | 16.3 | |

| Rape (n = 33) | Schubert49 (2011) | Middle East, Southeast Europe, South Asia and Central Africa | Finland | 21.8 |

| Kira52 (2012) | Iraq | USA | 90.9 | |

| Falb55 (2013) | Myanmar | Thailand | 0.3 | |

| Morof59 (2014) | Somalia and DRC | Uganda | 54.7 | |

| Idemudia58 (2014) | Zimbabwe | Polokwane, South Africa | 56.8 | |

| Bell60 (2015) | RDC | Ruanda | 8.0 | |

| Lerner65 (2016) | Africa, America and Western Europe | USA | 33.3 | |

| Wirtz67 (2016) | Somalia | Ethiopia | 20.1 | |

| Hopkinson69 (2017) | Africa, Asia, America and Eastern Europe | USA | 42.6 | |

| Logie70 (2017) | NI | Canada | 52.0 | |

| Stark72 (2017) | Sudan and South Sudan | Ethiopia | 16.1 | |

| Unwanted sexual contact (n = 7) | Asgary32 (2006) | Africa and Asia | USA | 6.7 |

| Avdibegovic33 (2006) | NI | Bosnia | 2.0 | |

| Schubert48 (2011) | Middle East, Southeast Europe, South Asia and Central Africa | Finland | 46.2 | |

| Falb55 (2013) | Southeastern Asia | Thailand | 0.7 | |

| Idemudia58 (2014) | Zimbabwe | Polokwane, South Africa | 63.2 | |

| Hopkinson69 (2017) | Africa, Asia, America and Eastern Europe | USA | 24.6 | |

| Stark72 (2017) | Sudan and South Sudan | Ethiopia | 22.0 | |

| Sexual coercion (n = 1) | Stark72 (2017) | Sudan and South Sudan | Ethiopia | 27.3 |

| Attempted rape (n = 2) | Idemudia58 (2014) | Zimbabwe | Polokwane, South Africa | 44.8 |

| Morof59 (2014) | Somalia and DRC | Uganda | 64.1 | |

| Forced pregnancy (n = 1) | Wirtz67 (2016) | East Africa | Ethiopia | 15.6 |

| Sexual torture (n = 6) | Hondius23 (2000) | Turkey and Iran | Netherlands | 23.1 |

| Asgary32 (2006) | Africa and Asia | USA | 9.0 | |

| Bradley34 (2006) | Turkey | United Kingdom | 2.1 | |

| Olsen36 (2006) | Middle East | Denmark | 11.3 | |

| Bogner37 (2007) | Middle East, Europe, Africa and Latin America | England | 11.1 | |

| Tamblyn50 (2011) | Africa | USA | 20.7 | |

| Sexual Assault (n = 5) | Gorst-Unsworth20 (1998) | Iraq | United Kingdom | 14.3 |

| Iacopino25 (2001) | Kosovo | Macedonia | 0.03 | |

| Bradley34 (2006) | Turkey | United Kingdom | 8.2 | |

| Hooberman40 (2007) | Africa, Asia, Central and South America and Europe | USA | 10.8 | |

| Williams48 (2010) | Africa and Middle East | United Kingdom | 12.9 | |

| Genital mutilation (n = 6) | Asgary32 (2006) | Africa and Asia | USA | 2.2 |

| Bradley34 (2006) | Turkey | United Kingdom | 1.0 | |

| Mitike47 (2009) | Somalia | Ethiopia | 42.4 | |

| Gibson-Helm57 (2014) | Africa and Middle East | Australia | 5.7 | |

| Connor61 (2015) | Somalia and Ethiopia | USA | 93.3 | |

| Chu64 (2016) | Africa | USA | 60.0 | |

| Sexual exploitation (n = 4) | Cardozo29 (2004) | Myanmar | Thailand | 1.0 |

| Nagai45 (2008) | Sudan | Uganda | 82.0 | |

| Idemudia58 (2014) | Zimbabwe | South Africa | 44.0 | |

| Wirtz67 (2016) | Somalia | Ethiopia | 27.3 | |

| Non-contact unwanted sexual experiences (n = 5) | Crescenzi27 (2002) | Tibet | India | 24.6 |

| Asgary32 (2006) | Africa and Asia | USA | 4.5 | |

| Avdibegovic33 (2006) | NI | Bosnia | 2.0 | |

| Falb55 (2013) | Myanmar | Thailand | 1.5 | |

| Hopkinson69 (2017) | Africa, Asia, America and Eastern Europe | USA | 29.8 | |

| Sexual Abuse (n = 8) | Allodi14 (1990) | Latin America | Canada | 21.4 |

| McKelvey16 (1995) | Vietnam | Philippines | 9.8 | |

| Blair22 (2000) | Cambodia | USA | 5.6 | |

| Kira42 (2007) | Iraq | USA | 1.2 | |

| Chang44 (2008) | Cambodia | USA | 4.9 | |

| Nagai45 (2008) | Sudan | Uganda | 85.0 | |

| Black54 (2013) | Iraq | USA | 4.6 | |

| Riley71 (2017) | Myanmar | Bangladesh | 13.0 | |

| Forced marriage (n = 2) | Asgary32 (2006) | Africa and Asia | USA | 2.2 |

| Wirtz67 (2016) | Somalia | Ethiopia | 19.5 | |

| Sexual Harassment (n = 4) | Asgary32 (2006) | Africa and Asia | USA | 12.4 |

| Bogic51 (2012) | Bosnia | Germany, Italy and United Kingdom | 5.2 | |

| Idemudia58 (2014) | Zimbabwe | Polokwane, South Africa | 52.8 | |

| Wright73 (2017) | Middle East | USA | 1.5 |

NI: not informed; USA: United States of America; DRC: Democratic Republic of the Congo

In five studies32,49,55,58,67, the authors did not report the number of victims, and it was not possible to estimate the overall prevalence. Estimating the sum of prevalence by specific type would overestimate the overall prevalence due to cases that suffered more than one type of SV.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have shown that SV is a constant threat throughout the refugee migration pathway3,12,13, which has been confirmed in the present review. Although most of the studies identified here revealed a higher prevalence among adult women, SV was also a serious problem in men and children. In addition, we observed the SV is perpetrated mainly by intimate partners, but also by military, guards and police. Most cases occur in the country of origin, in the form of rape and in refugees from Africa. In some refugee camps, such as Uganda and Cameroon, the frequency was alarming.

It is possible that prevalence may be underestimated in some studies, since many victims – especially men – do not report SV because of shame, threats by perpetrators, fear of being found guilty or suffering from stigma and exclusion from family and community6,74, with consequent low demand for health care and case records75. In addition, the humanitarian crisis caused by armed conflicts in the refugees’ countries of origin leads to large displacements of people and demands incompatible with the availability of health services and resources76, which may further reduce the chances of case identification. On the other hand, studies focused on the evaluation of mental trauma in health services may overestimate the prevalence.

In the meta-analysis of SV prevalence in women in emergency humanitarian complex scenarios, which also included internally displaced persons and excluded genital mutilation, the mean prevalence was 21.4% and higher in refugees from Africa12. In our review, we found several studies with a much higher prevalence. Regardless of the actual prevalence, SV was frequent in the populations studied, and deserves special attention in the health services and the reception of this population already weakened by traumas of war and persecution.

Young women are the main victims of SV, but men, children and adolescents are also victims, a reality little discussed in the literature. Men and unaccompanied minors are also exposed to the risk of sexual exploitation and abuse during migration and arrival in destination countries3. Nevertheless, the predominance in women is not surprising. The immigration process is accompanied by difficulties such as economic insecurity, language barriers and acculturation, which lead to the imbalance of power between women and partners, leading to increased tensions77. Because of economic, political, and social changes during wars and postwar periods, many men use violence to control women and reestablish their status of power78. Such conditions may explain the higher frequency of SV perpetrated by intimate partners.

SV occurs mainly before migration, in the countries of origin of the refugees. This suggests a relation with the conditions generated by the armed conflicts, which potentiate cultural norms of superiority of the masculine power present in these places, even before the condition of search of refuge. High prevalence in Africa supports this view. The Democratic Republic of Congo, where armed conflicts over natural resource reserves have lasted since independence in 196079, is marked by atrocities including group rape, sexual slavery, forced family involvement in rape, genital mutilation, among others80. More shocking is the fact that, even when hosted in refugee camps, this already fragile population still faces insecurity and suffers SV perpetrated by those from whom they expect protection, such as officers and police.

Rape was the most mentioned form of this violence. This can be explained by the more concrete definition, by the most remarkable experience, and because most studies have used the HTQ instrument, which has a specific question about rape and sexual abuse, but not about other forms of SV. Rape is considered the cruelest type because it brings serious and severe consequences to the health of the victims. War survivors diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder and rape victims report more somatic symptoms than those without a rape experience81. Rape also increases the chances of acquiring HIV infection, as reported in sub-Saharan African refugee women in Paris, and is related to social difficulties and lack of fixed residence due to the risk of transactional sex or sexual harassment during lodging by relatives or acquaintances82.

Several studies included in this review had many limitations, such as lack of detail on the population, outcome of interest, timing of the occurrence, profile of the perpetrators, gender and age of the victims. In addition, the studies did not include victims of the most recent migratory crisis, which began in 2015.

Our review also has limitations. The literature search did not include the terms “sexual torture” and “genital mutilation,” which may have resulted in low sensitivity and explained the number of articles found in reference lists. We did not include the gray literature and no methodological quality evaluation of the selected studies was performed. In addition, we did not restrict the sample size of the articles, which resulted in imprecise estimates in studies with few individuals38. Finally, methodological differences between the studies (different data collection sites, such as mental health services and refugee camps; different data collection instruments; studies focusing on mental disorders rather than SV prevalence; and unequal sampling) have contributed to the diversity of the rates found and heterogeneity between the studies, which prevented a meta-analysis to summarize the information.

In summary, results of this review show that SV is a frequent problem among refugees, both women and men, mainly those from Africa, and occurs at all times in the migratory process, including in places of supposed reception and protection. The SV problem among refugees from the most recent migratory crisis must be investigated in unselected scenarios and with more appropriate methods to better guide the necessary protection measures.

REFERENCES

- 1.1. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Global trends: forced displacement in 2016. Geneva: UNHCR; 2017.; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees . Global trends: forced displacement in 2016. Geneva: UNHCR; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.2. Basile KC, Smith SG, Breiding MJ, Black MC, Mahendra RR. Sexual violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements. Version 2.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014 [cited 2017 Jun 29]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/sv_surveillance_definitionsl-2009-a.pdf ; Basile KC, Smith SG, Breiding MJ, Black MC, Mahendra RR. Sexual violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements. Version 2.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [cited 2017 Jun 29]. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/sv_surveillance_definitionsl-2009-a.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.3. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Working with men and boy survivors of sexual and gender-based violence in forced displacement. Geneva: UNHCR; 2012.; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees . Working with men and boy survivors of sexual and gender-based violence in forced displacement. Geneva: UNHCR; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.4. Ward J, Vann B. Gender-based violence in refugee settings. Lancet. 2002 [cited 2017 Jun 29];360 Suppl:13-14. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140673602118022.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]; Ward J, Vann B. Gender-based violence in refugee settings. [cited 2017 Jun 29];Lancet. 2002 360(Suppl):13–14. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11802-2. https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140673602118022.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.5. United Nations. Sexual violence in conflict: General Assembly Security Council Report of the Secretary General. New York: UN; 2013.; United Nations . Sexual violence in conflict: General Assembly Security Council Report of the Secretary General. New York: UN; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.6. Women’s Refugee Commission. Mean streets: identifying and responding to urban refugees’ risks of gender-based violence male survivor and member of men of hope. New York: WRC; 2016.; Women’s Refugee Commission . Mean streets: identifying and responding to urban refugees’ risks of gender-based violence male survivor and member of men of hope. New York: WRC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.7. Sheehy I. Sexual assault in refugee camps. Havard Political Review. 2016 Oct 17 [cited 2017 Jun 29]. Available from: http://harvardpolitics.com/hprgument-posts/sexual-assault-in-refugee-camps/ ; Sheehy I. Sexual assault in refugee camps. Havard Political Review. 2016. Oct 17, [cited 2017 Jun 29]. http://harvardpolitics.com/hprgument-posts/sexual-assault-in-refugee-camps/

- 8.8. World Health Organization. World report on violence and health. Geneva: WHO; 2002. Sexual violence; p.147-74.; World Health Organization . World report on violence and health. Geneva: WHO; 2002. pp. 147–174. Sexual violence. [Google Scholar]

- 9.9. Jina R, Thomas LS. Health consequences of sexual violence against women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;27(1):15-26. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed]; Jina R, Thomas LS. Health consequences of sexual violence against women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;27(1):15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.10. Tewksbudy R. Effects of sexual assaults on men: physical, mental and sexual consequences. Int J Mens Health. 2007;6(1):22-35. 10.3149/jmh.0601.22 [DOI]; Tewksbudy R. Effects of sexual assaults on men: physical, mental and sexual consequences. Int J Mens Health. 2007;6(1):22–35. doi: 10.3149/jmh.0601.22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.11. Haal M, Hall J. The long-term effects of childhood sexual abuse: counseling implications. Vistas Online. 2011 [cited 2017 Jun 29]: Article 19. Available from: https://www.counseling.org/docs/disaster-and-trauma_sexual-abuse/long-term-effects-of-childhood-sexual-abuse.pdf?sfvrsn=2 ; Haal M, Hall J. The long-term effects of childhood sexual abuse: counseling implications. [cited 2017 Jun 29];Vistas Online. 2011 Article 19. https://www.counseling.org/docs/disaster-and-trauma_sexual-abuse/long-term-effects-of-childhood-sexual-abuse.pdf?sfvrsn=2. [Google Scholar]

- 12.12. Vu A, Adam A, Wirtz A, Pham K, Rubenstein L, Glass N, et al. The prevalence of sexual violence among female refugees in complex humanitarian emergencies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Curr. 2014;6. 10.1371/currents.dis.835f10778fd80ae031aac12d3b533ca7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Vu A, Adam A, Wirtz A, Pham K, Rubenstein L, Glass N, et al. The prevalence of sexual violence among female refugees in complex humanitarian emergencies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 6PLoS Curr. 2014 doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.835f10778fd80ae031aac12d3b533ca7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.13. Stark L, Ager A. A systematic review of prevalence studies of gender-based violence in complex emergencies. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2011;12(3):127-34. 10.1177/1524838011404252 [DOI] [PubMed]; Stark L, Ager A. A systematic review of prevalence studies of gender-based violence in complex emergencies. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2011;12(3):127–134. doi: 10.1177/1524838011404252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.14. Allodi F, Stiasny S. Women as torture victims. Can J Psychiatry. 1990;35(2):144-8. 10.1177/070674379003500207 [DOI] [PubMed]; Allodi F, Stiasny S. Women as torture victims. Can J Psychiatry. 1990;35(2):144–148. doi: 10.1177/070674379003500207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.15. Fornazzari X, Freire M. Women as victims of torture. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;82(3):257-60. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb03062.x [DOI] [PubMed]; Fornazzari X, Freire M. Women as victims of torture. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;82(3):257–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb03062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.16. McKelvey RS, Webb JA. A pilot study of abuse among Vietnamese Amerasians. Child Abuse Negl. 1995;19(5):545-53. 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00014-Y [DOI] [PubMed]; McKelvey RS, Webb JA. A pilot study of abuse among Vietnamese Amerasians. Child Abuse Negl. 1995;19(5):545–553. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00014-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.17. Peel MR. Effects on asylum seekers of ill treatment in Zaire. Br Med J. 1996;312(7026):293-4. 10.10.1136/bmj.312.7026.293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Peel MR. Effects on asylum seekers of ill treatment in Zaire. Br Med J. 1996;312(7026):293–294. doi: 10.10.1136/bmj.312.7026.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.18. Frljak A, Cengic S, Hauser M, Schei B. Gynecological complaints and war traumas: a study from Zenica, Bosnia-Herzegovina during the war. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76(4):350-4. 10.1111/j.1600-0412.1997.tb07991.x [DOI] [PubMed]; Frljak A, Cengic S, Hauser M, Schei B. Gynecological complaints and war traumas: a study from Zenica, Bosnia-Herzegovina during the war. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76(4):350–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.1997.tb07991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.19. Silove D, Steel Z, McGorry P, Mohan P. Trauma exposure, postmigration stressors, and symptoms of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress in Tamil asylum-seekers comparison with refugees and immigrants. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;97(3):175-81. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb09984.x [DOI] [PubMed]; Silove D, Steel Z, McGorry P, Mohan P. Trauma exposure, postmigration stressors, and symptoms of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress in Tamil asylum-seekers comparison with refugees and immigrants. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;97(3):175–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb09984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.20. Gorst-Unsworth C, Goldenberg E. Psychological sequelae of torture and organised violence suffered by refugees from Iraq. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172(1):90-4. https:// 10.1192/bjp.172.1.90 [DOI] [PubMed]; Gorst-Unsworth C, Goldenberg E. Psychological sequelae of torture and organised violence suffered by refugees from Iraq. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172(1):90–94. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.21. Loutan L, Bollini P, Pampallona S, Haan DB, Garazzo F. Impact of trauma and torture on asylum-seekers. Eur J Public Health.1999;9(2):93-6. 10.1093/eurpub/9.2.93 [DOI]; Loutan L, Bollini P, Pampallona S, Haan DB, Garazzo F. Impact of trauma and torture on asylum-seekers. Eur J Public Health. 1999;9(2):93–96. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/9.2.93. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.22. Blair RG. Risk factors associated with PTSD and major depression among Cambodian refugees in Utah. Health Soc Work. 2000;25(1):23-30. 10.1093/hsw/25.1.23 [DOI] [PubMed]; Blair RG. Risk factors associated with PTSD and major depression among Cambodian refugees in Utah. Health Soc Work. 2000;25(1):23–30. doi: 10.1093/hsw/25.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.23. Hondius AJK, Willigen LHM, Kleijn WC, Ploeg HM. Health problems among Latin-American and Middle Eastern refugees in the Netherlands: relations with violence exposure and ongoing sociopsychological strain. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13(4):619-34. 10.1023/A:1007858116390 [DOI] [PubMed]; Hondius AJK, Willigen LHM, Kleijn WC, Ploeg HM. Health problems among Latin-American and Middle Eastern refugees in the Netherlands: relations with violence exposure and ongoing sociopsychological strain. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13(4):619–634. doi: 10.1023/A:1007858116390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.24. Petersen HD, Worm L, Olsen MZ, Hartling OJ. Human rights violations in Burma/Myanmar: a two year follow-up examination. Dan Med Bull. 2000;47(5):359-62. [PubMed]; Petersen HD, Worm L, Olsen MZ, Hartling OJ. Human rights violations in Burma/Myanmar: a two year follow-up examination. Dan Med Bull. 2000;47(5):359–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.25. Iacopino V, Frank MW, Bauer HM, Keller AS, Fink SL, Ford D, et al. A population-based assessment of human rights abuses committed against ethnic Albanian refugees from Kosovo. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(12):2013-8. 10.2105/AJPH.91.12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Iacopino V, Frank MW, Bauer HM, Keller AS, Fink SL, Ford D, et al. A population-based assessment of human rights abuses committed against ethnic Albanian refugees from Kosovo. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(12):2013–2018. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.26. Tang SS, Fox SH. Traumatic experiences and the mental health of Senegalese refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189(8):507-12. 10.1097/00005053-200108000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed]; Tang SS, Fox SH. Traumatic experiences and the mental health of Senegalese refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189(8):507–512. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200108000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.27. Crescenzi A, Ketzer E, Ommeren M, Phuntsok K, Komproe I, Jong JTVM. Effect of political imprisonment and trauma history on recent Tibetan refugees in India. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15(5):369-75. 10.1023/A:1020129107279 [DOI] [PubMed]; Crescenzi A, Ketzer E, Ommeren M, Phuntsok K, Komproe I, Jong JTVM. Effect of political imprisonment and trauma history on recent Tibetan refugees in India. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15(5):369–375. doi: 10.1023/A:1020129107279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.28. Sabin M, Cardozo BL, Nackerud L, Kaiser R, Varese L. Factors associated with poor mental health among Guatemalan refugees living in Mexico 20 years after civil conflict. JAMA. 2003;290(5):635-42. 10.1001/jama.290.5.635 [DOI] [PubMed]; Sabin M, Cardozo BL, Nackerud L, Kaiser R, Varese L. Factors associated with poor mental health among Guatemalan refugees living in Mexico 20 years after civil conflict. JAMA. 2003;290(5):635–642. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.29. Cardozo BL, Talley L, Burton A, Crawford C. Karenni refugees living in Thai–Burmese border camps: traumatic experiences, mental health outcomes, and social functioning. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(12):2637-44. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed]; Cardozo BL, Talley L, Burton A, Crawford C. Karenni refugees living in Thai–Burmese border camps: traumatic experiences, mental health outcomes, and social functioning. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(12):2637–2644. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.30. Sesay FL. Where there is no ‘safe haven’: human rights abuses of Sierra Leonean women at home and in exile. Agenda Empower Women Gender Equity. 2004;(59):22-31.; Sesay FL. Where there is no ‘safe haven’: human rights abuses of Sierra Leonean women at home and in exile. Agenda Empower Women Gender Equity. 2004;(59):22–31. [Google Scholar]

- 31.31. Thomas S, Thomas S, Nafees B, Bhugra D. ‘I was running away from death’: the pre-flight experiences of unaccompanied asylum seeking children in the UK. Child Care Health Dev. 2004;30(2):113-22. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2003.00404.x [DOI] [PubMed]; Thomas S, Thomas S, Nafees B, Bhugra D. ‘I was running away from death’: the pre-flight experiences of unaccompanied asylum seeking children in the UK. Child Care Health Dev. 2004;30(2):113–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2003.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.32. Asgary R, Metalios EE, Smith CL, Paccione GA. Evaluating asylum seekers/torture survivors in urban primary care: a collaborative approach at the Bronx Human Rights Clinic. Health Hum Rights. 2006;9(2):164-79. 10.2307/4065406 [DOI] [PubMed]; Asgary R, Metalios EE, Smith CL, Paccione GA. Evaluating asylum seekers/torture survivors in urban primary care: a collaborative approach at the Bronx Human Rights Clinic. Health Hum Rights. 2006;9(2):164–179. doi: 10.2307/4065406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.33. Avdibegovic E, Sinanovic O. Consequences of domestic violence on women’s mental health in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Croat Med J. 2006;47(5):730-41. [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Avdibegovic E, Sinanovic O. Consequences of domestic violence on women’s mental health in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Croat Med J. 2006;47(5):730–741. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.34. Bradley L, Tawfiq N. The physical and psychological effects of torture in Kurds seeking asylum in the United Kingdom. Torture. 2006;16(1):41-7. [PubMed]; Bradley L, Tawfiq N. The physical and psychological effects of torture in Kurds seeking asylum in the United Kingdom. Torture. 2006;16(1):41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.35. Schweitzer R, Melville F, Steel Z, Lacherez P. Trauma, post-migration living difficulties, and social support as predictors of psychological adjustment in resettled Sudanese refugees. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(2):179-87. 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01766.x [DOI] [PubMed]; Schweitzer R, Melville F, Steel Z, Lacherez P. Trauma, post-migration living difficulties, and social support as predictors of psychological adjustment in resettled Sudanese refugees. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(2):179–187. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.36. Olsen DR, Montgomery E, Bojhom S, Foldspang A. Prevalent musculoskeletal pain as a correlate of previous exposure to torture. Scand J Public Health. 2006;34(5):496-503. 10.1080/14034940600554677 [DOI] [PubMed]; Olsen DR, Montgomery E, Bojhom S, Foldspang A. Prevalent musculoskeletal pain as a correlate of previous exposure to torture. Scand J Public Health. 2006;34(5):496–503. doi: 10.1080/14034940600554677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.37. Bögner D, Herlihy J, Brewin CR. Impact of sexual violence on disclosure during Home Office interviews. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:75-81. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.030262 [DOI] [PubMed]; Bögner D, Herlihy J, Brewin CR. Impact of sexual violence on disclosure during Home Office interviews. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:75–81. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.030262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.38. Edston E, Olsson C. Female victims of torture. J Forensic Leg Med. 2007;14(6):368-73. 10.1016/j.jflm.2006.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed]; Edston E, Olsson C. Female victims of torture. J Forensic Leg Med. 2007;14(6):368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.39. Hammoury N, Khawaja M. Screening for domestic violence during pregnancy in an antenatal clinic in Lebanon. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17(6):605-6. 10.1093/eurpub/ckm009 [DOI] [PubMed]; Hammoury N, Khawaja M. Screening for domestic violence during pregnancy in an antenatal clinic in Lebanon. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17(6):605–606. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.40. Hooberman JB, Rosenfeld B, Lhewa D, Rasmussen A, Keller A. Classifying the torture experiences of refugees living in the United States. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(1):108-23. 10.1177/0886260506294999 [DOI] [PubMed]; Hooberman JB, Rosenfeld B, Lhewa D, Rasmussen A, Keller A. Classifying the torture experiences of refugees living in the United States. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(1):108–123. doi: 10.1177/0886260506294999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.41. John-Langba J. The relationship of sexual and gender-based violence to sexual-risk behaviour among refugee women in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Health Popul. 2007;9(2):26-37. 10.12927/whp.2007.18957 [DOI] [PubMed]; John-Langba J. The relationship of sexual and gender-based violence to sexual-risk behaviour among refugee women in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Health Popul. 2007;9(2):26–37. doi: 10.12927/whp.2007.18957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.42. Kira I, Hammad A, Lewandowski L, Templin T, Ramaswamy V, Ozkan B, et al. The physical and mental status of Iraqui refugees and its etiology. Ethn Dis. 2007;17 Suppl 3:S3-79-S3-82. [PubMed]; Kira I, Hammad A, Lewandowski L, Templin T, Ramaswamy V, Ozkan B, et al. The physical and mental status of Iraqui refugees and its etiology. Ethn Dis. 2007;17(Suppl 3):S3–79-S3-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.43. Piwowarczyk L. Asylum seekers seeking mental health services in the United States: clinical and legal implications. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(9):715-22. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318142ca0b [DOI] [PubMed]; Piwowarczyk L. Asylum seekers seeking mental health services in the United States: clinical and legal implications. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(9):715–722. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318142ca0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.44. Chang J, Rhee S, Berthold SM. Child abuse and neglect in Cambodian refugee families: characteristics and implications for practice. Child Welfare. 2008;87(1):141-60. [PubMed]; Chang J, Rhee S, Berthold SM. Child abuse and neglect in Cambodian refugee families: characteristics and implications for practice. Child Welfare. 2008;87(1):141–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.45. Nagai M, Karunakara U, Rowley E, Burnham G. Violence against refugees, non-refugees and host populations in southern Sudan and northern Uganda. Glob Public Health. 2008;3(3):249-70. 10.1080/17441690701768904 [DOI]; Nagai M, Karunakara U, Rowley E, Burnham G. Violence against refugees, non-refugees and host populations in southern Sudan and northern Uganda. Glob Public Health. 2008;3(3):249–270. doi: 10.1080/17441690701768904. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.46. Harrison KM, Claass J, Spiegel PB, Bamuturaki J, Patterson N, Muyonga M, et al. HIV behavioural surveillance among refugees and surrounding hots communities in Uganda, 2006. Afr J AIDS Res. 2009;8(1):29-41. 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.1.4.717 [DOI] [PubMed]; Harrison KM, Claass J, Spiegel PB, Bamuturaki J, Patterson N, Muyonga M, et al. HIV behavioural surveillance among refugees and surrounding hots communities in Uganda, 2006. Afr J AIDS Res. 2009;8(1):29–41. doi: 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.1.4.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.47. Mitike G, Deressa W. Prevalence and associated factors of female genital mutilation among Somali refugees in eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:264. 10.1186/1471-2458-9-264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Mitike G, Deressa W. Prevalence and associated factors of female genital mutilation among Somali refugees in eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. 264BMC Public Health. 2009;9 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.48. Williams ACC, Peña CR, Rice ASC. Persistent pain in survivors of torture: a cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(5):715-22. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed]; Williams ACC, Peña CR, Rice ASC. Persistent pain in survivors of torture: a cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(5):715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.49. Schubert CC, Punamäki RL. Mental health among torture survivors: cultural background, refugee status and gender. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65(3):175-82. https://di.org/10.3109/08039488.2010.514943 [DOI] [PubMed]; Schubert CC, Punamäki RL. Mental health among torture survivors: cultural background, refugee status and gender. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65(3):175–182. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2010.514943. https://di.org/10.3109/08039488.2010.514943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.50. Tamblyn JM, Calderon AJ, Combs S, O’Brien MM. Patients from abroad becoming patients in everyday practice: torture survivors in primary care. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13(4):798-801. 10.1007/s10903-010-9429-2 [DOI] [PubMed]; Tamblyn JM, Calderon AJ, Combs S, O’Brien MM. Patients from abroad becoming patients in everyday practice: torture survivors in primary care. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13(4):798–801. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9429-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.51. Bogic M, Ajdukovic D, Bremner S, Franciskovic T, Galeazzi GM, Kucukalic A, et al. Factors associated with mental disorders in long-settled war refugees: refugees from the former Yugoslavia in Germany, Italy and the UK. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(3):216-23. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084764 [DOI] [PubMed]; Bogic M, Ajdukovic D, Bremner S, Franciskovic T, Galeazzi GM, Kucukalic A, et al. Factors associated with mental disorders in long-settled war refugees: refugees from the former Yugoslavia in Germany, Italy and the UK. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(3):216–223. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.52. Kira I, Lewandowski L, Somers CL, Yoon JS, Chiodo L. The effects of trauma types, cumulative trauma, and PTSD on IQ in two highly traumatized adolescent groups. Psychol Trauma. 2012; 4(1):128-139.; Kira I, Lewandowski L, Somers CL, Yoon JS, Chiodo L. The effects of trauma types, cumulative trauma, and PTSD on IQ in two highly traumatized adolescent groups. Psychol Trauma. 2012;4(1):128–139. [Google Scholar]

- 53.53. Parmar P, Agrawal P, Greenough PG, Goyal R, Kayden S. Sexual violence among host and refugee population in Djohong District, Eastern Cameroon. Glob Public Health. 2012;7(9):974-94. 10.1080/17441692.2012.688061 [DOI] [PubMed]; Parmar P, Agrawal P, Greenough PG, Goyal R, Kayden S. Sexual violence among host and refugee population in Djohong District, Eastern Cameroon. Glob Public Health. 2012;7(9):974–994. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2012.688061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.54. Black BM, Chiodo LM, Weisz NA, Elias-Lambert N, Kernsmit PD, Yoon JS, et al. Iraqi American refugee youths’ exposure to violence: relationship to attitudes and peers’ perpetration of dating violence. Violence Against Women. 2013;19(2):202-21. 10.1177/1077801213476456 [DOI] [PubMed]; Black BM, Chiodo LM, Weisz NA, Elias-Lambert N, Kernsmit PD, Yoon JS, et al. Iraqi American refugee youths’ exposure to violence: relationship to attitudes and peers’ perpetration of dating violence. Violence Against Women. 2013;19(2):202–221. doi: 10.1177/1077801213476456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.55. Falb KL, McCormick MC, Hemenway D, Anfinson K, Silverman JG. Suicide ideation and victimization among refugee women along the Thai-Burma border. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(5) 631-5. 10.1002/jts.21846 [DOI] [PubMed]; Falb KL, McCormick MC, Hemenway D, Anfinson K, Silverman JG. Suicide ideation and victimization among refugee women along the Thai-Burma border. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(5):631–635. doi: 10.1002/jts.21846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.56. Tufan AE Alkin M.; Bosgelmez S. Post-traumatic stress disorder among asylum seekers and refugees in Istanbul may be predicted by torture and loss due to violence. Nord J Psychiatry. 2013;67(3):219-24. 10.3109/08039488.2012.732113 [DOI] [PubMed]; Tufan AE, Alkin M, Bosgelmez S. Post-traumatic stress disorder among asylum seekers and refugees in Istanbul may be predicted by torture and loss due to violence. Nord J Psychiatry. 2013;67(3):219–224. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2012.732113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.57. Gibson-Helm M, Teed H, Block A, Knight M, East C, Wallace EM, et al. Maternal health and pregnancy outcomes among women of refugee background from African countries: a retrospective, observational study in Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:382. 10.1186/s12884-014-0392-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Gibson-Helm M, Teed H, Block A, Knight M, East C, Wallace EM, et al. Maternal health and pregnancy outcomes among women of refugee background from African countries: a retrospective, observational study in Australia. 382BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/s12884-014-0392-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.58. Idemudia ES. Displaced, homeless and abused: the dynamics of gender-based sexual and physical abuses of homeless Zimbabweans in South Africa. Gender Behav. 2014;12(2):6312-6.; Idemudia ES. Displaced, homeless and abused: the dynamics of gender-based sexual and physical abuses of homeless Zimbabweans in South Africa. Gender Behav. 2014;12(2):6312–6316. [Google Scholar]

- 59.59. Morof DF, Sami S, Mangeni M, Blanton C, Cardozo BL, Tomczyk B. A cross-sectional survey on gender-based violence and mental health among female urban refugees and asylum seekers in Kampala, Uganda. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;127(2):138-43. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed]; Morof DF, Sami S, Mangeni M, Blanton C, Cardozo BL, Tomczyk B. A cross-sectional survey on gender-based violence and mental health among female urban refugees and asylum seekers in Kampala, Uganda. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;127(2):138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.60. Bell SA, Lori J, Redman R, Seng J. Psychometric validation and comparison of the Self-Reporting Questionnaire-20 and Self-Reporting Questionnaire-Suicidal Ideation and Behavior among Congolese refugee women. J Nurs Meas. 2015;23(3):393-408. 10.1891/1061-3749.23.3.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Bell SA, Lori J, Redman R, Seng J. Psychometric validation and comparison of the Self-Reporting Questionnaire-20 and Self-Reporting Questionnaire-Suicidal Ideation and Behavior among Congolese refugee women. J Nurs Meas. 2015;23(3):393–408. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.23.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.61. Connor JJ, Hunt S, Finsaas M, Ciesinski A, Ahmed A, Robinson BB. Sexual health care, sexual behaviors and functioning, and female genital cutting: perspectives from Somali women living in the United States. J Sex Res. 2016;53(3):346-59. 10.1080/00224499.2015.1008966 [DOI] [PubMed]; Connor JJ, Hunt S, Finsaas M, Ciesinski A, Ahmed A, Robinson BB. Sexual health care, sexual behaviors and functioning, and female genital cutting: perspectives from Somali women living in the United States. J Sex Res. 2016;53(3):346–359. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2015.1008966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.62. Sipsma HL, Falb KL, Willie T, Bradley EH, Bienkowski L, Meerdink N, et al. Violence against Congolese refugee women in Rwanda and mental health: a cross-sectional study using latent class analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e006299. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Sipsma HL, Falb KL, Willie T, Bradley EH, Bienkowski L, Meerdink N, et al. Violence against Congolese refugee women in Rwanda and mental health: a cross-sectional study using latent class analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e006299. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.63. Al-Modallal H, Abu-Zayed I, Abujilban S, Shehab T, Atoum M. Prevalence of Intimate partner violence among women visiting health care centers in Palestine refugee camps in Jordan. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36(2):137-48. 10.1080/07399332.2014.948626 [DOI] [PubMed]; Al-Modallal H, Abu-Zayed I, Abujilban S, Shehab T, Atoum M. Prevalence of Intimate partner violence among women visiting health care centers in Palestine refugee camps in Jordan. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36(2):137–148. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.948626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.64. Chu T, Akinsulure-Smith AM. Health outcomes and attitudes toward female genital cutting in a community-based sample of West African immigrant women from high-prevalence countries in New York City. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2016;25(1):63-83. 10.1080/10926771.2015.1081663771.2015.1081663 [DOI]; Chu T, Akinsulure-Smith AM. Health outcomes and attitudes toward female genital cutting in a community-based sample of West African immigrant women from high-prevalence countries in New York City. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2016;25(1):63–83. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2015.1081663771.2015.1081663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.65. Lerner E, Bonanno GA, Kaeatley E, Joscelyne A, Keller AS. Predictors of suicidal ideation in treatment-seeking survivors of torture. Psychol Trauma. 2016;8(1):17-24. 10.1037/tra0000040 [DOI] [PubMed]; Lerner E, Bonanno GA, Kaeatley E, Joscelyne A, Keller AS. Predictors of suicidal ideation in treatment-seeking survivors of torture. Psychol Trauma. 2016;8(1):17–24. doi: 10.1037/tra0000040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.66. Um M, Kim H, Palinkas LA. Correlates of domestic violence victimization among North Korean refugee women in South Korea. J Interpers Violence. 2018;33(13):2037-58. 10.1177/0886260515622297 [DOI] [PubMed]; Um M, Kim H, Palinkas LA. Correlates of domestic violence victimization among North Korean refugee women in South Korea. J Interpers Violence. 2018;33(13):2037–2058. doi: 10.1177/0886260515622297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.67. Wirtz, A, Glass N, Pham K, Perrin N, Rubenstein LS, Singh S, et al. Comprehensive development and testing of the ASIST-GBV, a screening tool for responding to gender-based violence among women in humanitarian settings. Confl Health. 2016;10:7. 10.1186/s13031-016-0071-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Wirtz A, Glass N, Pham K, Perrin N, Rubenstein LS, Singh S, et al. Comprehensive development and testing of the ASIST-GBV, a screening tool for responding to gender-based violence among women in humanitarian settings. 7Confl Health. 2016;10 doi: 10.1186/s13031-016-0071-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.68. Gušić S, Cardeña E, Bengtsson H, Søndergaard HP. Dissociative experiences and trauma exposure among newly arrived and settled young war refugees. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2017;26(10):1132-49. 10.1080/10926771.2017.1365792 [DOI]; Gušić S, Cardeña E, Bengtsson H, Søndergaard HP. Dissociative experiences and trauma exposure among newly arrived and settled young war refugees. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2017;26(10):1132–1149. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2017.1365792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.69. Hopkinson R, Keatley E, Glaeser E, Erickson-Schroth L, Fattal O, Sullinam NM. Persecution experiences and mental health of LGBT asylum seekers. J Homosex. 2017;64(12):1650-66. 10.1080/00918369.2016.1253392 [DOI] [PubMed]; Hopkinson R, Keatley E, Glaeser E, Erickson-Schroth L, Fattal O, Sullinam NM. Persecution experiences and mental health of LGBT asylum seekers. J Homosex. 2017;64(12):1650–1666. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2016.1253392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.70. Logie CH, Kaida A, Pokomandy A, O’Brien N, O’Campo P, MacGillivray J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of forced sex as a self-reported mode of HIV acquisition among a cohort of women living with HIV in Canada. J Interpers Violence. 2017 Jul 1:886260517718832. 10.1177/0886260517718832 [DOI] [PubMed]; Logie CH, Kaida A, Pokomandy A, O’Brien N, O’Campo P, MacGillivray J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of forced sex as a self-reported mode of HIV acquisition among a cohort of women living with HIV in Canada. J Interpers Violence. 2017 Jul 1;:886260517718832. doi: 10.1177/0886260517718832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.71. Riley A, Varner A, Ventevogel P, Hasan MMT, Welton-Mitchell C. Daily stressors, trauma exposure and mental health among stateless Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Transcul Psychiatry. 2017;54(3):304-31. 10.1177/1363461517705571 [DOI] [PubMed]; Riley A, Varner A, Ventevogel P, Hasan MMT, Welton-Mitchell C. Daily stressors, trauma exposure and mental health among stateless Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Transcul Psychiatry. 2017;54(3):304–331. doi: 10.1177/1363461517705571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.72. Stark l, Sommer M, Davis K, Asghar K, Assazenew Baysa A, Abdela G, et al. Disclosure bias for group versus individual reporting of violence amongst conflict affected adolescent girls in DRC and Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0174741. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; l Stark, Sommer M, Davis K, Asghar K, Assazenew Baysa A, Abdela G, et al. Disclosure bias for group versus individual reporting of violence amongst conflict affected adolescent girls in DRC and Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0174741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.73. Wright AM, Talia YR, Aldhalimi A, Broadbridge CL, Jamil H, Lumley MA, et al. Kidnapping and mental health in Iraqi refugees: the role of resilience. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19(1):98-107. 10.1007/s10903-015-0340-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Wright AM, Talia YR, Aldhalimi A, Broadbridge CL, Jamil H, Lumley MA, et al. Kidnapping and mental health in Iraqi refugees: the role of resilience. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19(1):98–107. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0340-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.74. Hynes M, Cardozo BL. Sexual violence against refugee women. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(8):819-23. https://doi.og/10.1089/152460900750020847 [DOI] [PubMed]; Hynes M, Cardozo BL. Sexual violence against refugee women. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(8):819–823. doi: 10.1089/152460900750020847. https://doi.og/10.1089/152460900750020847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.75. Alcorn T. Responding to sexual violence in armed conflict. Lancet. 2014;383(9934):2034-7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60970-3 [DOI] [PubMed]; Alcorn T. Responding to sexual violence in armed conflict. Lancet. 2014;383(9934):2034–2037. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60970-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.76. Checci F, Warsame A, Treacy-Wong V, Polonsky J, Ommerem M, Prudhon C. Public health information in crisis-affected populations: a review of methods and their use for advocacy and action. Lancet. 2017;390(10109):2297-313. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30702-X [DOI] [PubMed]; Checci F, Warsame A, Treacy-Wong V, Polonsky J, Ommerem M, Prudhon C. Public health information in crisis-affected populations: a review of methods and their use for advocacy and action. Lancet. 2017;390(10109):2297–2313. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30702-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.77. Hilsdon AM, Rozario S. Special issue on Islam, gender and human rights. Women’s Stud Int Forum. 2006 29(4):331-8. 10.1016/j.wsif.2006.05.009 [DOI]; Hilsdon AM, Rozario S. Special issue on Islam, gender and human rights. Women’s Stud Int Forum. 2006;29(4):331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2006.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.78. Guruge S, Ford-Gilboe M, Varcoe C, Jayasuriya-Illesingh V, Ganesan M, Sivayogan S, et al. Intimate partner violence in the post-war context: women’s experiences and community leaders’ perceptions in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0174801. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Guruge S, Ford-Gilboe M, Varcoe C, Jayasuriya-Illesingh V, Ganesan M, Sivayogan S, et al. Intimate partner violence in the post-war context: women’s experiences and community leaders’ perceptions in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0174801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.79. Bastik M, Grimm K, Kunz R. Sexual violence in armed conflict: global overview and implications for the security sector. Geneva: Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces; 2007.; Bastik M, Grimm K, Kunz R. Sexual violence in armed conflict: global overview and implications for the security sector. Geneva: Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 80.80. Peterman A, Palermo T, Bredenkamp C. Estimates and determinants of sexual violence against women in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1060-7. 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Peterman A, Palermo T, Bredenkamp C. Estimates and determinants of sexual violence against women in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1060–1067. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.81. Gola H, Engler H, Schauer M, Adenauer H, Riether C, Kolassa S, et al. Victims of rape show increased cortisol responses to trauma reminders: a study in individuals with war- and torture-related PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(2):213-20. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed]; Gola H, Engler H, Schauer M, Adenauer H, Riether C, Kolassa S, et al. Victims of rape show increased cortisol responses to trauma reminders: a study in individuals with war- and torture-related PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(2):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.82. Pannetier J, Ravalihasy A, Lydié N, Lert F, Desgrées du Loû A. Prevalence and circumstances of forced sex and post-migration HIV acquisition in sub-Saharan African migrant women in France: an analysis of the ANRS-PARCOURS retrospective population-based study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(1):e16-23. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30211-6 [DOI] [PubMed]; Pannetier J, Ravalihasy A, Lydié N, Lert F, Desgrées du Loû A. Prevalence and circumstances of forced sex and post-migration HIV acquisition in sub-Saharan African migrant women in France: an analysis of the ANRS-PARCOURS retrospective population-based study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(1):e16–e23. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]