Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Fruit and vegetable (FV) intake is recommended for the prevention of coronary heart disease (CHD). FVs are also an important source of exposure to pesticide residues. Whether the relations of FV intake with CHD differ according to pesticide residue status is unknown.

OBJECTIVE:

To examine the associations of high- and low-pesticide-residue FVs with the risk of CHD.

METHODS:

We followed 145,789 women and 24,353 men free of cardiovascular disease and cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) at baseline and participating in three ongoing prospective cohorts: the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS: 1998-2012), the NHS-II (1999-2013), and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS: 1998-2012). FV intake was assessed via food frequency questionnaires. We categorized FVs as having high- or low-pesticide-residues using a validated method based on pesticide surveillance data from the US Department of Agriculture. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) of CHD in relation to high- and low-pesticide-residue FV intake.

RESULTS:

A total of 3,707 incident CHD events were identified during 2,241,977 person-years of follow-up. In multivariable-adjusted models, a greater intake of low-pesticide-residue FVs was associated with a lower risk of CHD whereas high-pesticide-residue FV intake was unrelated to CHD risk. Specifically, compared with individuals consuming <1 serving/day of low-pesticide-residue FVs, those consuming ≥4 servings/day had 20% (95CI: 4%, 33%) lower risk of CHD. The corresponding HR (comparing ≥4 servings/day to <1 serving/day) for high-pesticide-residue FV intake and CHD was 0.97 (95%CI: 0.72, 1.30).

CONCLUSIONS:

Our data suggested exposure to pesticide residues through FV intake may modify some cardiovascular benefits of FV consumption. Further confirmation of these findings, especially using biomarkers for assessment of pesticide exposure, are needed.

Keywords: Pesticide residues, fruits and vegetables, coronary heart disease

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the most common cause of death in the United States, accounting for 800,000 deaths every year (Benjamin et al., 2017). The Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the American Heart Association encourage consuming at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables (FVs) daily to reduce the risk of heart disease (Eckel et al., 2014; Millen et al., 2016). However, FVs can also act as carriers of pesticide residues. In 2016, 85% of FVs in U.S. markets had detectable pesticide residues, and nearly half of FVs had detectable levels of three or more pesticides (USDA 2016). Although the detectable residues in most FVs (>99%) in the US market (USDA 2016) did not exceed tolerance levels, it remains important to study potential health effect of these pesticide residues since chronic low-level exposure to mixtures of pesticide is common (CDC 2016).

In in vivo and ex vivo experiments, some pesticides have been shown to affect the cardiovascular system (Georgiadis et al., 2018b). Several pesticides such as organophosphate (through inhibition of acetyl-cholinesterase), organochlorine pesticides (through alteration of ligand-gated ion channel activity), pyrethroids (through modification of voltage-gated sodium channels), and atrazine (through inhibition of cardiac heme oxygenase-1 activity) have been found to induce cellular oxidative stress and increase apoptosis (Georgiadis et al., 2018a; Kalender et al., 2004; Keshk et al., 2014; Razavi et al., 2015; Vadhana et al., 2013; Zafiropoulos et al., 2014; Zaki 2012), the risk factors involved in the onset and progression of cardiovascular events (Forstermann et al., 2017; Kadioglu et al., 2016). In animal studies, chronic dietary exposure to pesticide mixtures at nontoxic doses increases oxidative stress, adiposity, and dysglycemia (Lukowicz et al., 2018; Uchendu et al., 2018). In humans, despite the known acute cardiotoxicity of organophosphate poisoning, the cardiovascular effects of chronic low-level exposure to pesticide residues are understudied (Bar-Meir et al., 2007; Saadeh et al., 1997).

We previously developed and validated a questionnaire-based method for assessment of pesticide residues in FVs: the Pesticide Residue Burden Score (PRBS) (Chiu et al., 2018b; Hu et al., 2016). Here, we used the PRBS to evaluate the association of FV intake considering their pesticide residue status with risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) in three large prospective cohorts of men and women.

Methods

STUDY POPULATION

This study included participants from three prospective cohorts: the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS; N=121,700 female registered nurses, aged 30 to 55 in 1976), the NHS-II (N=116,671 female registered nurses, aged 25 to 42 in 1989) and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS; N=51,529 male dentists, pharmacists, veterinarians, optometrists, osteopathic physicians, and podiatrists, aged 40 to 75 years in 1986) (Bao et al., 2016). In all cohorts, self-administered questionnaires are distributed every 2 years to collect information about medical history, lifestyle and health conditions. Response rates are ~90% in each cycle. For the present analysis, we followed participants from 1998 (for NHS/HPFS) or 1999 (for NHS-II), to allow matching of dietary assessments with data from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Pesticide Data Program (PDP) (USDA 2016), until the end of the 2012-14 follow-up period in NHS/HPFS and the 2013-15 follow-up period in NHS-II. We excluded participants with a history of CVD or cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) in 1998/1999, those who had died prior to 1998/1999, those who skipped over half of the questions regarding fruit and vegetable intake, and those with missing or invalid caloric intake (<800 kcal or >4200kcal/day in men; <500 or >3500kcal/day in women). The final analysis included 145,789 women and 24,353 men. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Brigham and Women's Hospital and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

DIET AND PESTICIDE RESIDUE ASSESSMENT

We assessed diet every 4 years using a validated 131-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) (Rimm et al., 1992; Salvini et al., 1989; Yuan et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2017). The PDP annually collected and tested around 10,000 samples of major agriculture commodities for more than 400 different pesticide residues, and the testing results for each sample are available on their website (USDA 2016). We classified FVs as having high- or low-pesticide-residues according to the PRBS, a validated scoring system for assessment of pesticide residues in FVs using surveillance data from the PDP (Chiu et al., 2018b; Hu et al., 2016). We used PDP data starting in 1996, when the program expanded in response to a report from the National Academy of Sciences (Council 1993) and the Food Quality Protection Act of 1996 (Congress 1996). We averaged PDP data over 4-year periods corresponding to diet assessment periods. Specifically, PDP data from 1996 to 1999 was linked to diet assessments in 1998 (NHS/HPFS) and 1999 (NHS-II); PDP data from 2000 to 2003 was linked to diet assessments in 2002 and 2003, and so forth.

The PRBS uses three measures in the PDP to classify FVs: 1) the percentage of sampled produce with detectable pesticide residues, 2) the percentage of sampled produce with pesticide residues above tolerance levels, and 3) the percentage of sampled produce with three or more different types of pesticides. We ranked FVs according to each measure and assigned a score of 0 for FVs in the lowest tertile, 1 for FVs in the middle, and 2 for FVs in the upper tertile for each measure. When an FFQ item combined fresh, frozen, or canned into a single question for which PDP reported fresh and frozen/canned data separately, we used the average of pesticide residue for each produce. The PRBS was defined as the sum of scores across three measures on a scale of 0 to 6, where high-pesticide-residue FVs had a PRBS ≥4 and low-pesticide-residue FVs had a PRBS <4. FVs without PDP data were classified as undetermined pesticide residue status. We then summed intakes of high-, low- and undetermined pesticide-residue FVs, separately, for each participant.

COVARIATES

We obtained information on participant’s anthropometrics, lifestyle, and medical history, including weight, smoking status, physical activity, use of aspirin, multivitamin, menopausal status, postmenopausal hormone-replace therapy, and oral contraceptives, at questionnaire and updated it every two years. We also collected information on self-reported diagnosis of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes in follow-up questionnaires. Alcohol was assessed and updated every 4 years using an FFQ. We calculated the Alternate Healthy Eating Index-2010 on the basis of 9 food components (except FVs and alcohol because alcohol intake was modeled separately) (Chiuve et al., 2012). Description of the reproducibility and validity of physical activity and alcohol use are described elsewhere (Chasan-Taber et al., 1996; Giovannucci et al., 1991).

OUTCOME ASSESSMENT

CHD was defined as fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, and fatal CHD events. When participants reported a physician diagnosed heart disease in a follow-up questionnaire, we obtained permission of access to medical records. Study investigators blinded to participant risk factor status reviewed medical records; when medical records were not available, we performed telephone interviews instead. Non-fatal myocardial infarction was confirmed using World Health Organization criteria on the basis of symptoms plus elevated specific cardiac enzymes or electrocardiogram changes indicative of new ischemia (Mendis et al., 2011). We identified deaths by reports from next of kin, the U.S. postal system, or death certificates obtained from state vital statistics departments and the National Death Index. These methods identified more than 98% of deaths. We confirmed fatal CHD by hospital records, autopsy reports, or coronary artery disease listed as underlying cause of death on the death certificate and if evidence of the previous CHD documented in medical records.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Participants were followed from the return of the baseline questionnaire until the date of an incident event, death, or end of follow-up, whichever occurred first. Intakes of high- and low-pesticide-residue FVs were cumulatively averaged over follow-up years to better characterize long-term exposure. We created quintiles of intake within each cohort. We also categorized intake according to increments in absolute intake (<1, 1-1.9, 2-2.9, 3-3.9, ≥ 4 servings per day). We estimated hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between high- and low-pesticide-residue FV intake and subsequent risk of CHD using Cox proportional hazards regression models with age as the time scale. We adjusted for baseline covariates, including race/ethnicity, family history of myocardial infarction (<65 years in women and <60 years in men), family history of diabetes, self-reported hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes at baseline, as well as time-varying covariates, including body mass index (BMI) (<23, 23 to 24.9, 25 to 29.9, 30 to 34.9, ≥35 kg/m2), physical activity (<3, 3 to <9, 9 to <18, 18 to <27, ≥27 METs/week), smoking status (never, past, current), current multivitamin use (yes/no), current aspirin use (yes/no), intakes of alcohol (0, 0.1 to 4.9, 5 to 14.9, ≥15 g/day), total energy intake (kcal/day, quintiles), intake of FVs with undetermined residue status (quintiles), and Alternate Healthy Eating Index (quintiles). In women (NHS, NHS-II), we additionally adjusted for menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone use (premenopausal, postmenopausal never users, postmenopausal past users, postmenopausal current users). In the NHS-II study, we further adjusted for oral contraceptive use (never, past, current users). Because intake of high-pesticide-residue FVs and low-pesticide-residue FVs may confound each other, we also adjusted for low-pesticide-residue FV intake in the model of high-pesticide-residue FV intake and vice versa. To test for linear trend, we modeled quintile exposure as a continuous variable by assigning a median value to each quintile with the use of the Wald test. To test for nonlinearity, we fit a restricted cubic spline to the multivariable Cox proportional hazards models. Analyses were performed separately for each cohort and were pooled with the use of fixed-effect meta-analyses with inverse-variance weighting.

We evaluated effect modification by age (<median, ≥ median), BMI (<30, ≥30 kg/m2), smoking (never, ever), physical activity (<median, ≥ median), alcohol intake (<median, ≥ median), and family history of myocardial infarction (yes, no) adding cross-product terms between high and low pesticide residue FV intake and the effect modifier to the main effects model. Analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute), at a two-tailed alpha level of 0.05.

Results

A list of high- and low-pesticide FVs is shown in the Table 1. We identified a total of 3,707 incident CHD cases over 2,241,977 person-years of follow up. Intakes of high- and low-pesticide-residue FVs were positively correlated with each other (rSpearman= 0.63, 0.70, and 0.62 in NHS, NHS-II, and HPFS, respectively). Participants consuming more high-pesticide-residue FVs were more active, less likely to smoke, more likely to take multivitamin supplements, and had higher intakes of total FVs, fiber, antioxidant nutrients and flavonoids than participants consuming fewer high-pesticide-residue FVs (Table 2 and Supplemental Table S1). A similar pattern was observed for participants across quintiles of low-pesticide-residue FV intake except that women with greater low-pesticide-residue FV intake also had higher alcohol intake (Table 2 and Supplemental Table S2). Other characteristics were similar across quintiles of high- or low-pesticide-residue FV intake (Table 2).

Table 1.

Fruit and vegetable items in the food frequency questionnaire and pesticide data program and corresponding PRBS at mid follow-up (2004-2007).

| Definition of measure contamination | PRBS | Residue status |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Items in FFQ | Items in PDP | ||

| peas or lima beans, FFC | sweet pea, frozen | 0 | Low |

| grapefruit | grapefruit | 0 | Low |

| dried plums or prunes | dried plum | 0 | Low |

| orange juice | orange juice | 0 | Low |

| apple juice or cider | apple juice | 1 | Low |

| cauliflower | cauliflower | 1 | Low |

| tofu | soybeans | 1 | Low |

| yam or sweet potatoes | sweet potatoes | 1 | Low |

| tomatoes | tomatoes | 1 | Low |

| cantaloupe | cantaloupe | 2 | Low |

| carrot, raw or cooked | carrot | 2 | Low |

| winter squash | winter squash | 2 | Low |

| broccoli | broccoli | 3 | Low |

| oranges | oranges | 3 | Low |

| blueberry | blueberry | 3 | Low |

| eggplant, summer squash, zucchini | eggplant, summer squash (0.5: 0.5)a | 3 | Low |

| celery | celery | 4 | High |

| kale, mustard, chard | kale | 4 | High |

| fresh apple or pear | apple, pear (0.74:0.26) *a | 4 | High |

| grape or raisin | grape, raisin (0.62: 0.38)* | 4 | High |

| green/yellow/red peppers | sweet peppers | 4 | High |

| apple sauce | apple sauce | 4 | High |

| string bean | green bean | 5 | High |

| head lettuce, leaf lettuce | lettuce | 6 | High |

| peach or plum | peach, plum (0.70: 0.30)a | 6 | High |

| spinach, raw | spinach, fresh | 6 | High |

| strawberries, FFC | strawberries, fresh or frozen | 6 | High |

Abbreviations: FFC, fresh, frozen, or canned; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; PDP, pesticide data program; PRBS, pesticide residue burden score.

Ratio weighted for pesticide residue for each produce according to the ratio of consumption of each produce from the USDA report

Foods with undetermined pesticide contamination status in this period: corn, cooked spinach, cabbage, tomato pastes, brussel sprouts, mixed vegetables, and other juice.

The ranges of PRBS are 0 to 3 for low-pesticide-residue fruits and vegetables, and 4-6 for high-pesticide residue fruits and vegetables.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participants according to quintiles of high- and low-pesticide-residue fruit and vegetable intake.

| Quintile of High-Pesticide-Residue Fruit and Vegetable Intake |

Quintile of Low-Pesticide-Residue Fruit and Vegetable Intake |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Quintile 1 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 5 | Quintile 1 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 5 |

| Nurses’ Health Study (1998) | ||||||

| Number of participants | 13,305 | 13,199 | 13,115 | 13,150 | 13,153 | 13,127 |

| High-pesticide-residue FVs (servings/d) | 0.5(0.2) | 1.3(0.1) | 3.1(1.1) | 0.9(0.7) | 1.5(0.8) | 2.3(1.2) |

| Low-pesticide-residue FVs (servings/d) | 1.4(0.9) | 2.2(1.0) | 3.1(1.4) | 0.8(0.3) | 2.0(0.2) | 4.1(1.1) |

| Total FVs (servings/d) | 2.5(1.2) | 4.5(1.3) | 7.6(2.3) | 2.4(1.1) | 4.5(1.1) | 7.7(2.2) |

| Age (y) | 63.5(7.3) | 63.6(7.0) | 63.5(6.8) | 63.7(7.3) | 63.4(7.0) | 63.4(6.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.8(5.5) | 26.7(5.2) | 26.2(5.1) | 26.8(5.4) | 26.6(5.2) | 26.3(5.2) |

| White (%) | 97.3 | 97.7 | 97.4 | 97.1 | 97.7 | 97.3 |

| Physical activity (MET/wk) | 18.0(78.5) | 22.5(75.2) | 28.7(69.6) | 19.2(78.7) | 22.0(71.7) | 27.2(69.0) |

| Family history of diabetes (%) | 28.0 | 27.7 | 28.7 | 28.8 | 29.0 | 27.6 |

| Family history of MI (%) | 20.0 | 19.9 | 20.9 | 20.3 | 20.1 | 20.4 |

| Current smoker (%) | 17.9 | 9.6 | 5.5 | 15.7 | 9.3 | 7.7 |

| Premenopausal (%) | 6.1 | 6.8 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 6.1 |

| Current menopausal users (%) | 43.8 | 47.6 | 48.5 | 45.2 | 48.3 | 48.0 |

| Baseline hypertension (%) | 42.3 | 41.8 | 40.0 | 40.7 | 41.6 | 42.7 |

| Baseline hypercholesterolemia (%) | 55.8 | 55.8 | 54.0 | 56.1 | 56.1 | 54.8 |

| Baseline diabetes (%) | 6.6 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 7.7 | 6.8 | 5.6 |

| Multivitamin supplement use (%) | 63.0 | 68.5 | 71.9 | 63.8 | 67.4 | 70.7 |

| Current aspirin use (%) | 50.2 | 54.0 | 52.7 | 48.8 | 52.9 | 54.4 |

| Total energy intake (kcal/day) | 1467(481) | 1718(495) | 2010(537) | 1410(457) | 1711(466) | 2090(533) |

| Alcohol intake (g/d) | 4.9(9.9) | 5.2(9.2) | 4.8(8.2) | 4.4(9.2) | 5.2(9.3) | 5.4(9.0) |

| Modified AHEI (score)* | 37.9(8.4) | 39.2(8.5) | 40.9(8.7) | 41.4(8.7) | 38.8(8.5) | 37.8(8.0) |

| Nurses’ Health Study II (1999) | ||||||

| Number of participants | 16,186 | 16,251 | 16,011 | 16,021 | 16,045 | 16,039 |

| High-pesticide-residue FVs (servings/d) | 0.4(0.1) | 1.2(0.1) | 2.9(1.2) | 0.7(0.6) | 1.3(0.8) | 2.2(1.3) |

| Low-pesticide-residue FVs (servings/d) | 1.2(0.8) | 1.9(0.9) | 3.0(1.5) | 0.7(0.2) | 1.8(0.1) | 3.9(1.2) |

| Total FVs (servings/d) | 2.0(1.0) | 3.7(1.2) | 7.0(2.4) | 1.9(1.0) | 3.8(1.1) | 7.0(2.4) |

| Age (y) | 43.6(4.7) | 44.0(4.6) | 44.4(4.6) | 43.9(4.7) | 44.0(4.7) | 44.2(4.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.1(6.6) | 26.3(6.1) | 25.9(5.8) | 26.9(6.5) | 26.3(6.1) | 26.0(5.9) |

| White (%) | 95.8 | 96.8 | 96.5 | 95.5 | 97.0 | 96.1 |

| Physical activity (MET/wk) | 14.0(19.4) | 20.1(26.4) | 28.5(31.6) | 15.7(21.8) | 20.0(24.5) | 26.5(32.1) |

| Family history of diabetes (%) | 25.4 | 24.4 | 24.5 | 25.1 | 24.4 | 24.0 |

| Family history of MI (%) | 21.0 | 20.0 | 20.4 | 20.7 | 20.4 | 20.1 |

| Current smoker (%) | 13.4 | 8.5 | 5.7 | 12.2 | 8.4 | 6.5 |

| Premenopausal (%) | 77.9 | 78.1 | 76.9 | 76.9 | 77.9 | 77.6 |

| Current menopausal hormone users (%) | 10.5 | 10.6 | 11.1 | 11.3 | 11.1 | 10.6 |

| Oral contraceptive use | ||||||

| Never user(%) | 11.9 | 13.2 | 14.8 | 12.9 | 13.0 | 14.7 |

| Current user (%) | 8.9 | 9.2 | 8.3 | 8.8 | 8.9 | 8.3 |

| Past user (%) | 79.2 | 77.6 | 77.0 | 78.3 | 78.1 | 77.0 |

| Baseline hypertension (%) | 14.0 | 13.2 | 13.1 | 13.8 | 12.4 | 13.9 |

| Baseline hypercholesterolemia (%) | 26.7 | 24.6 | 23.6 | 26.4 | 24.2 | 23.6 |

| Baseline diabetes (%) | 2.0 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| Multivitamin supplement use (%) | 50.4 | 57.5 | 63.5 | 50.8 | 57.9 | 63.5 |

| Current aspirin use (%) | 17.1 | 16.9 | 17.6 | 16.9 | 16.6 | 17.6 |

| Total energy intake (kcal/day) | 1547(513) | 1813 (522) | 2128(556) | 1470(477) | 1807(492) | 2217(544) |

| Alcohol intake (g/d) | 3.5(7.8) | 4.1(7.3) | 4.2(6.9) | 3.3(7.3) | 4.0(7.1) | 4.3(7.2) |

| Modified AHEI (score)* | 36.9(8.9) | 38.4(9.4) | 40.8(9.8) | 39.9(9.2) | 38.5(9.6) | 37.5(9.3) |

| Health Professionals Follow-up Study (1998) | ||||||

| Number of participants | 4,864 | 5,035 | 4,923 | 4,876 | 4,865 | 4,869 |

| High-pesticide-residue FVs (servings/d) | 0.5(0.2) | 1.4(0.1) | 3.3(1.3) | 1.0(0.8) | 1.5(0.9) | 2.4(1.4) |

| Low-pesticide-residue FVs (servings/d) | 1.6(1.0) | 2.4(1.1) | 3.4(1.6) | 0.9(0.3) | 2.2(0.2) | 4.5(1.3) |

| Total FVs (servings/d) | 2.7(1.2) | 4.7(1.4) | 8.1(2.5) | 2.6(1.2) | 4.7(1.2) | 8.2(2.5) |

| Age (y) | 61.6(8.6) | 62.8(8.7) | 64.2(8.7) | 62.1(8.6) | 62.9(8.7) | 63.1(8.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.3(3.6) | 26.2(3.6) | 25.7(3.5) | 26.2(3.5) | 26.0(3.5) | 25.9(3.6) |

| White (%) | 95.1 | 95.8 | 96.1 | 95.5 | 96.0 | 95.4 |

| Physical activity (MET/wk) | 26.2(33.1) | 35.0(39.1) | 47.3(46.6) | 28.6(35.3) | 35.2(38.1) | 44.8(45.5) |

| Family history of diabetes (%) | 21.7 | 22.7 | 21.8 | 21.7 | 22.4 | 22.0 |

| Family history of MI (%) | 14.8 | 15.5 | 14.8 | 13.7 | 15.4 | 14.4 |

| Current smoker (%) | 8.2 | 4.3 | 2.3 | 7.4 | 4.4 | 3.0 |

| Baseline hypertension (%) | 34.4 | 33.4 | 30.9 | 32.5 | 32.8 | 33.0 |

| Baseline hypercholesterolemia (%) | 46.5 | 44.8 | 42.8 | 44.6 | 45.1 | 42.6 |

| Baseline diabetes (%) | 5.1 | 4.8 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 5.5 | 5.2 |

| Multivitamin supplement use (%) | 55.4 | 59.4 | 62.6 | 55.6 | 59.6 | 62.9 |

| Current aspirin use (%) | 62.8 | 62.6 | 62.1 | 61.9 | 64.2 | 62.6 |

| Total energy intake (kcal/day) | 1746(558) | 1993(582) | 2309(642) | 1679(528) | 1987(548) | 2395(636) |

| Alcohol intake (g/d) | 12.0(16.4) | 11.3(14.2) | 9.9(12.5) | 11.1(15.4) | 11.4(14.1) | 10.6(13.0) |

| Modified AHEI (Score)* | 32.0(8.2) | 34.4(7.9) | 38.0(8.4) | 35.0(8.7) | 34.4(8.3) | 35.3(8.0) |

Values are means (SD) or percentages. All variables except age are age-standardized.

Abbreviations: Modified AHEI, Modified Alternate Healthy Eating Index score; BMI, body mass index; METs: metabolic equivalent tasks; FV: fruits and vegetables; MI: myocardial infarction.

Modified AHEI: AHEI-2010, excluding criteria for intakes of fruits and vegetables and alcohol.

METs are defined as the ratio of caloric needed per kilogram of body weight per hour of physical activity divided by the caloric needed per kilogram of body weight at rest.

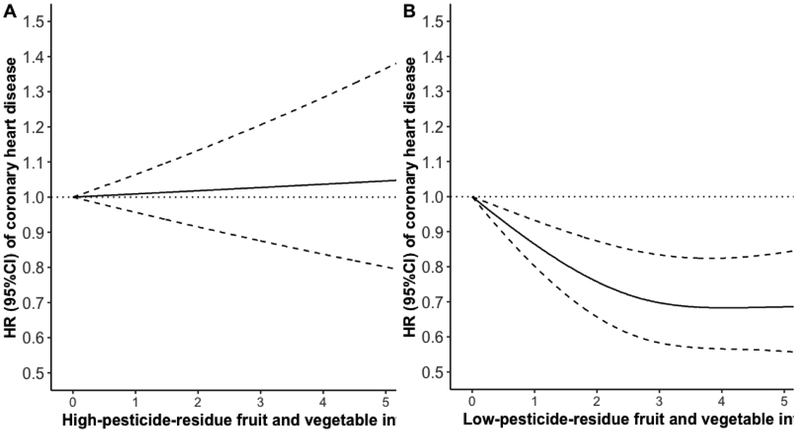

In age-adjusted models, intakes of both high- and low-pesticide-residue FVs were inversely associated with risk of CHD (Table 3). However, after adjusting for potential confounders, the associations of high- and low-pesticide-residue FV intake with CHD diverged (Table 3). Specifically, high-pesticide-residue FV intake was unrelated to risk of CHD. The pooled HRs (95% CI) for participants in increasing quintiles of high-pesticide-residue FV intake were 1 (reference), 0.99 (0.89, 1.10), 1.03 (0.92, 1.15), 1.01 (0.89, 1.14) and 1.06 (0.92, 1.21) (P, trend=0.45). In contrast, greater consumption of low-pesticide-residue FV intake was associated with a lower risk of CHD. The pooled HRs (95% CI) for participants in increasing quintiles of low-pesticide-residue FV intake were 1 (reference), 0.92 (0.83, 1.02), 0.85 (0.76, 0.95), 0.81 (0.72, 0.92), and 0.82 (0.71, 0.94) (P, trend=0.001). Similarly, when FV intake was modeled as a continuous variable in a spline model, intake of high-pesticide-residue FV was unrelated to CHD incidence (Figure. 1A), while intake of low-pesticide-residue FV intake was inversely related to CHD with the strongest association observed at ~4 servings/day and little evidence of further benefit with higher intake (P, non-linearity=0.0004) (Figure. 1B). The same divergent pattern was observed when FV intake was modeled in categories based on absolute intakes (Supplemental Figure S1). In this model, intake of 4 servings/day or more of low-pesticide-residue FVs was associated with 20% lower risk of CHD (HR: 0.80, 95%CI: 0.67, 0.96; compared to <1 serving/day) whereas the same intake of high-pesticide-residue FV intake was unrelated to CHD risk (HR: 0.97; 95%CI: 0.72, 1.30; compared to <1 serving/day).

Table 3.

Hazard ratios (95% CI) of coronary heart disease according to quintiles of high- and low-pesticide-residue fruit and vegetable intake.

| Quintiles of High-Pesticide-Residue Fruit and Vegetable Intake | P, trend | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | |||

| NHS | Median (servings/d) | 0.49 | 0.90 | 1.28 | 1.71 | 2.53 | |

| Person-years | 163,052 | 168,372 | 168,367 | 170,853 | 171,688 | ||

| Cases | 455 | 377 | 364 | 328 | 329 | ||

| Age-adjusted | 1 (Ref.) | 0.81 (0.70, 0.93) | 0.78 (0.68, 0.89) | 0.71 (0.62, 0.82) | 0.73 (0.64, 0.85) | <.0001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted*† | 1 (Ref.) | 0.93 (0.81, 1.08) | 0.99 (0.85, 1.16) | 0.95 (0.80, 1.12) | 1.03 (0.85, 1.24) | 0.70 | |

| NHS II | Median (servings/d) | 0.36 | 0.75 | 1.11 | 1.56 | 2.40 | |

| Person-years | 222,919 | 219,637 | 221,323 | 221,398 | 221,412 | ||

| Cases | 122 | 96 | 101 | 86 | 82 | ||

| Age-adjusted1 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.77 (0.59, 1.01) | 0.79 (0.61, 1.03) | 0.67 (0.51, 0.88) | 0.63 (0.48, 0.83) | 0.0007 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted*† | 1 (Ref.) | 0.92 (0.68, 1.23) | 1.08 (0.78, 1.49) | 1.01 (0.71, 1.45) | 1.03 (0.69, 1.55) | 0.77 | |

| HPFS | Median (servings/d) | 0.50 | 0.92 | 1.30 | 1.78 | 2.71 | |

| Person-years | 57,663 | 58,371 | 58,830 | 58,689 | 59,403 | ||

| Cases | 298 | 292 | 270 | 255 | 252 | ||

| Age-adjusted | 1 (Ref.) | 0.92 (0.78, 1.08) | 0.81 (0.69, 0.96) | 0.75 (0.63, 0.89) | 0.70 (0.59, 0.83) | <.0001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted *† | 1 (Ref.) | 1.11 (0.94, 1.32) | 1.08 (0.89, 1.30) | 1.10 (0.90, 1.34) | 1.10 (0.88, 1.38) | 0.54 | |

| Pooled | Multivariable-adjusted*†§ | 1 (Ref.) | 0.99 (0.89, 1.10) | 1.03 (0.92, 1.15) | 1.01 (0.89, 1.14) | 1.06 (0.92, 1.21) | 0.45 |

| Quintiles of Low-Pesticide-Residue Fruit and Vegetable Intake | P, trend | ||||||

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | |||

| NHS | Median (servings/d) | 0.99 | 1.69 | 2.22 | 2.83 | 3.84 | |

| Person-years | 163,820 | 168,196 | 169,571 | 170,034 | 170,710 | ||

| Cases | 444 | 398 | 350 | 317 | 344 | ||

| Age-adjusted | 1 (Ref.) | 0.87 (0.76, 0.99) | 0.75 (0.65, 0.86) | 0.66 (0.57, 0.77) | 0.74(0.64, 0.85) | <.0001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted*‡ | 1 (Ref.) | 0.97 (0.84, 1.12) | 0.87 (0.74, 1.03) | 0.82 (0.69, 0.98) | 0.92 (0.76, 1.12) | 0.23 | |

| NHS II | Median (servings/d) | 0.72 | 1.39 | 1.95 | 2.59 | 3.71 | |

| Person-years | 221,140 | 221,415 | 221,391 | 221,364 | 221,379 | ||

| Cases | 116 | 105 | 89 | 88 | 89 | ||

| Age-adjusted | 1 (Ref.) | 0.90 ( 0.69, 1.17) | 0.73( 0.55, 0.96) | 0.69 (0.52, 0.91) | 0.70 (0.53, 0.92) | 0.001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted*‡ | 1 (Ref.) | 0.96 (0.72, 1.28) | 0.82 (0.59, 1.14) | 0.82 (0.57, 1.18) | 0.81 (0.54, 1.21) | 0.22 | |

| HPFS | Median (servings/d) | 1.11 | 1.85 | 2.44 | 3.13 | 4.31 | |

| Person-years | 57,457 | 58,735 | 58,766 | 59,004 | 58,995 | ||

| Cases | 329 | 274 | 267 | 264 | 233 | ||

| Age-adjusted | 1 (Ref.) | 0.78(0.66, 0.91) | 0.73 (0.62, 0.85) | 0.69 (0.59, 0.81) | 0.58(0.49, 0.69) | <.0001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted*‡ | 1 (Ref.) | 0.84(0.71, 1.00) | 0.83 (0.69, 1.00) | 0.79 (0.65, 0.97) | 0.69 (0.55, 0.87) | 0.003 | |

| Pooled | Multivariable-adjusted*ठ| 1 (Ref.) | 0.92 (0.83, 1.02) | 0.85 (0.76, 0.95) | 0.81 (0.72, 0.92) | 0.82 (0.71, 0.94) | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; NHS II, Nurses’ Health Study II; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study.

Adjusted for age (years), ethnicity (white/non-white), body mass index (BMI) (<23, 23 to 24.9, 25 to 29.9, 30 to 34.9, ≥35 kg/m2), physical activity (<3, 3 to <9, 9 to <18, 18 to <27, ≥27 metabolic equivalents/week), smoking status (never, past, current), family history of diabetes (yes/no), family history of myocardial infarction (yes/no), history of hypertension (yes/no), history of diabetes (yes/no), history of hypercholesterolemia (yes/no), postmenopausal hormone use ( premenopausal/never/past/current, in NHS and NHS II), oral contraceptive use (never/past/current user, in NHS II), current vitamin use (yes/no), current aspirin use (yes/no), alcohol (0, 0.1 to 4.9, 5 to 14.9, ≥15 g/day), total energy intake (quintiles) and Alternate Healthy Eating Index score excluding criteria for intake of fruits and vegetables and alcohol (quintiles).

Additionally adjusted for intakes of low-pesticide-residue fruits and vegetables (quintile) and other fruits and vegetables with undetermined residues (quintile).

Additionally adjusted for intakes of high-pesticide-residue fruits and vegetables (quintile) and other fruits and vegetables with undetermined residues (quintile).

Results were combined with the use of the fixed-effect model.

Figure 1. Fruit and vegetable intake, considering pesticide residue status, and risk of coronary heart disease.

Adjusted for age (years), ethnicity (white/non-white), body mass index (<23, 23 to 24.9, 25 to 29.9, 30 to 34.9, ≥35 kg/m2), physical activity (<3, 3 to <9, 9 to <18, 18 to <27, ≥27 metabolic equivalents/week), smoking status (never, past, current), family history of diabetes (yes/no), family history of myocardial infarction (yes/no), history of hypertension (yes/no), history of diabetes (yes/no), history of hypercholesterolemia (yes/no), postmenopausal hormone use (premenopausal/never/past/current, in NHS and NHS II), oral contraceptive use (never/past/current user, in NHS II), current vitamin use (yes/no), current aspirin use (yes/no), alcohol (0, 0.1 to 4.9, 5 to 14.9, ≥15 g/day), total energy intake (quintiles), and Alternate Healthy Eating Index score excluding criteria for intake of fruits and vegetables and alcohol (quintiles).

A). Additionally adjusted for intakes of low-pesticide-residue fruits and vegetables (quintile) and other fruits and vegetables with undetermined residues (quintile).

B). Additionally adjusted for intakes of high-pesticide-residue fruits and vegetables (quintile) and other fruits and vegetables with undetermined residues (quintile).

The associations of high- and low-pesticide-residue FV intake with CHD remained similar when potatoes, fruit juice, and processed fruits (e.g, apple sauce) were not counted as FVs (Supplemental Table S3), when additionally adjusted for folate, carotenoids, and flavonoids (Supplemental Table S4), when we stopped updating diet once cancer, diabetes or angina developed, or when we used the most recent diet as exposure (Supplemental Table S5). Nonetheless, there was no association between baseline FV intake, regardless of pesticide residue status, and CHD incidence (Supplemental Table S5). Results were also consistent with the primary analysis when removing potential mediators (BMI or baseline history of hypertension, diabetes or hypercholesterolemia), and when for adjusting incident hypertension, diabetes or hypercholesterolemia (Supplemental Table S6). Finally, there was no evidence of effect modification by age, BMI, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol drinking or family history of myocardial infarction (All P> 0.10).

Discussion

In this prospective study of 170,142 US adults followed for up to 14 years, we found that greater consumption of low-pesticide-residue FVs was associated with a lower risk of CHD, with 20% lower risk for 4 or more servings/day of intake compared to those consuming less than 1 serving/day. In contrast, high-pesticide-residue FV intake was not associated with risk of CHD. These results remained robust to adjustment of multiple confounders, different approaches of exposure modeling, and exclusion of potatoes and fruit juice from the analysis. Overall, these data suggest that the inverse association between FV intake with CHD may differ according to the burden of pesticide residues.

Our results of low-pesticide-residue FV intake are consistent with the literature on total FV intake and CVD risk. In the present study, the HR (95%CI) of CHD comparing extreme quintiles of low-pesticide-residue FV was 0.82 (0.71, 0.94), which is similar to that of our previous report on total FV intake combining data from NHS and HPFS (0.83 [0.76, 0.91]) (Bhupathiraju et al., 2013). A recent meta-analysis of prospective studies also showed that a 200 mg/day (~2.5 servings/ day) increase in total FV intake was associated with 8% (95%CI: 6%, 10%, I2=0%, n=15 studies) lower risks of CHD.

Increased rates of CVD or CVD mortality among farmers and pesticide applicators have been found in some studies (Dayton et al., 2010; Fleming et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2002), although findings have not been consistent across studies (Blair et al., 1993; Blair et al., 2005; Mills et al., 2009). However, for most individuals, chronic low-level exposure to pesticide residues through diet and other sources is more relevant in terms of exposure burden but remains vastly understudied (Tsatsakis et al., 2017). A recent study in mice evaluated the metabolic effects of chronic ingestion of chow mixed with six common pesticides (boscalid, captan, chlorpyrifos, thiofanate, thiacloprid, and ziram) at tolerable intake levels over 1 year (Lukowicz et al., 2018). Consuming pesticide-contaminated chow caused metabolic disruption including increased body weight, greater adiposity, and glucose intolerance in male mice as well as fasting hyperglycemia and greater oxidative stress in female mice (Lukowicz et al., 2018). In a separate study in Wistar rats, low-level co-exposure to chlorpyrifos and deltamethrin for 120 days increased oxidative stress, triglyceride, and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, and decreased high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels compared to a single exposure to either pesticide (Uchendu et al., 2018). We are unaware of comparable data in humans or of studies trying to disentangle the potential risks of exposure to pesticide residues from the benefits of FV consumption on cardiovascular or metabolic disease risk. However, we have previously reported diverging patterns of association of high- and low-pesticide-residue FV intake with some reproductive outcomes (Chiu et al., 2015; Chiu et al., 2016; Chiu et al., 2018a). Other studies also showed that organic culture produce was found to have higher antioxidant capacities and flavonoid contents than those from conventional culture (Dani et al., 2007; Jin et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2008). Overall, these data suggest that pesticide residues in food may modify the associations between FVs and certain health outcomes. Given the paucity of data on this topic and exploratory nature of our study using questionnaires for the assessment of dietary pesticide exposure, further evaluation in independent studies, especially using biomonitoring data (Katsikantami et al., 2019,), is essential.

Study limitations must be considered when interpreting our findings. First, the PRBS is estimated based on national pesticide surveillance data and individual diet intake data instead of individual levels of biomarkers of pesticide exposure. In addition, we did not have data on organic food consumption or data separating fresh versus frozen or canned consumption, (Whitacre 2009) thus increasing the likelihood of exposure misclassification. While the PRBS has been validated against urinary pesticide metabolites, suggesting that this method adequately characterizes habitual pesticide exposure through FVs (Chiu et al., 2018b; Hu et al., 2016), future studies should collect information on organic food consumption given a growing trend in organic sales in recent years (USDA 2017) and examine alternate methods that couple FFQ-PDP to estimate long-term dietary residue intake for a specific class or a mixture of pesticides (Curl et al., 2015; Katsikantami et al., 2019). Second, given that contamination with specific pesticides changes over time, we allowed pesticide contamination status to change over time by matching updated PDP data to updated diet assessments. This method did not allow us to classify all FVs in each period, but we were able to statistically adjust for intake of unclassified FVs in all analyses. Third, despite adjustment for a large number of potential confounders, there may be still residual and unmeasured confounding factors. However, participants with greater consumption of high- and low-pesticide-residue FVs had similar patterns of baseline characteristics and dietary behaviors including total FV intake. In addition, results remained unchanged with the additional adjustment of the nutrients that were associated with CHD in earlier studies (Aung and Htay 2018; Kim and Je 2017; Osganian et al., 2003), suggesting that the divergent associations are more likely due to differences in pesticide residues, although other differences cannot be ruled out. Finally, participants were mostly white health professionals, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. However, the homogeneity of the population minimizes confounding and enhances internal validity. Strengths of our study include its large sample size, extensive follow-up, repeated measurement of diet and lifestyle factors with validated tools, and detailed covariate information.

In conclusion, intake of low-pesticide-residue FVs was associated with a lower risk of CHD whereas high-pesticide-residue FV intake was not associated with CHD risk, suggesting that pesticide residues may modify some cardiovascular benefits of FV consumption. These findings, combined with results from other studies which showed that replacing conventional diet with an organic diet reduces exposure to organophosphate or pyrethroid pesticides (Bradman et al., 2015; Curl et al., 2019; Hyland et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2006; Oates et al., 2014), suggested that consuming organically grown FVs for the high-pesticide-residue counterparts may be beneficial. Nevertheless, given the scarcity of data on this topic, our findings should not be interpreted as contradicting current advice to consume at least 5 servings of FVs per day. Instead, they suggest that additional research on the health effects of long-term low-level exposure to pesticides through diet is needed.

Supplementary Material

Highlight.

Very little is known about whether exposure to lower levels of pesticides has any deleterious effect on coronary heart disease (CHD).

Intake of low-pesticide-residue fruits and vegetables (FVs) was inversely associated with risk of CHD.

Intake of high-pesticide-residue FVs was not associated with risk of CHD.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, the Nurses’ Health Study, the Nurses’ Health Study II, and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study for their contributions and long-term commitment to scientific research.

Sources of Funding:

This work was supported by research grants [U01 HL145386, UM1 CA186107, R01 HL034594, UM1 CA176726, UM1 CA167552, R01 HL35464, P30DK046200, and P30ES000002] from the National Institute of Health (NIH). Dr. Bhupathiraju is supported by a Career Development Grant from the NIH [KOI DK107804]. Dr. Ley was supported by grant P20GM109036 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- BMI:

body mass index

- CHD:

coronary heart disease

- CVD:

cardiovascular disease

- FFQ:

food frequency questionnaire

- FVs:

fruits and vegetables

- HRs:

hazard ratios

- PDP:

Pesticide Data Program

- PRBS:

Pesticide Residue Burden Score

- USDA:

US Department of Agriculture

Footnotes

Disclosures:

The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- Aung K; Htay T Review: Folic acid may reduce risk for CVD and stroke, and B-vitamin complex may reduce risk for stroke. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:JC44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y; Bertoia ML; Lenart EB; Stampfer MJ; Willett WC; Speizer FE; Chavarro JE Origin, Methods, and Evolution of the Three Nurses' Health Studies. Am J Public Health 2016;106:1573–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Meir E; Schein O; Eisenkraft A; Rubinshtein R; Grubstein A; Militianu A; Glikson M Guidelines for treating cardiac manifestations of organophosphates poisoning with special emphasis on long QT and Torsades De Pointes. Crit Rev Toxicol 2007;37:279–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin EJ; Blaha MJ; Chiuve SE; Cushman M; Das SR; Deo R; de Ferranti SD; Floyd J; Fornage M; Gillespie C; Isasi CR; Jimenez MC; Jordan LC; Judd SE; Lackland D; Lichtman JH; Lisabeth L; Liu S; Longenecker CT; Mackey RH; Matsushita K; Mozaffarian D; Mussolino ME; Nasir K; Neumar RW; Palaniappan L; Pandey DK; Thiagarajan RR; Reeves MJ; Ritchey M; Rodriguez CJ; Roth GA; Rosamond WD; Sasson C; Towfighi A; Tsao CW; Turner MB; Virani SS; Voeks JH; Willey JZ; Wilkins JT; Wu JH; Alger HM; Wong SS; Muntner P Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;135:e146–e603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhupathiraju SN; Wedick NM; Pan A; Manson JE; Rexrode KM; Willett WC; Rimm EB; Hu FB Quantity and variety in fruit and vegetable intake and risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98:1514–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair A; Dosemeci M; Heineman EF Cancer and other causes of death among male and female farmers from twenty-three states. Am J Ind Med 1993;23:729–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair A; Sandler DP; Tarone R; Lubin J; Thomas K; Hoppin JA; Samanic C; Coble J; Kamel F; Knott C; Dosemeci M; Zahm SH; Lynch CF; Rothman N; Alavanja MC Mortality among participants in the agricultural health study. Ann Epidemiol 2005;15:279–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradman A; Quiros-Alcala L; Castorina R; Aguilar Schall R; Camacho J; Holland NT; Barr DB; Eskenazi B Effect of Organic Diet Intervention on Pesticide Exposures in Young Children Living in Low-Income Urban and Agricultural Communities. Environ Health Perspect 2015;123:1086–1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Centers for Disease Control Prevention Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals. Updated Tables, August 2014. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Chasan-Taber S; Rimm EB; Stampfer MJ; Spiegelman D; Colditz GA; Giovannucci E; Ascherio A; Willett WC Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire for male health professionals. Epidemiology 1996;7:81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu YH; Afeiche MC; Gaskins AJ; Williams PL; Petrozza JC; Tanrikut C; Hauser R; Chavarro JE Fruit and vegetable intake and their pesticide residues in relation to semen quality among men from a fertility clinic. Hum Reprod 2015;30:1342–1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu YH; Gaskins AJ; Williams PL; Mendiola J; Jorgensen N; Levine H; Hauser R; Swan SH; Chavarro JE Intake of Fruits and Vegetables with Low-to-Moderate Pesticide Residues Is Positively Associated with Semen-Quality Parameters among Young Healthy Men. J Nutr 2016;146:1084–1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu YH; Williams PL; Gillman MW; Gaskins AJ; Minguez-Alarcon L; Souter I; Toth TL; Ford JB; Hauser R; Chavarro JE Association Between Pesticide Residue Intake From Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables and Pregnancy Outcomes Among Women Undergoing Infertility Treatment With Assisted Reproductive Technology. JAMA Intern Med 2018a;178:17–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu YH; Williams PL; Minguez-Alarcon L; Gillman M; Sun Q; Ospina M; Calafat AM; Hauser R; Chavarro JE Comparison of questionnaire-based estimation of pesticide residue intake from fruits and vegetables with urinary concentrations of pesticide biomarkers. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2018b;28:31–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiuve SE; Fung TT; Rimm EB; Hu FB; McCullough ML; Wang M; Stampfer MJ; Willett WC Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr 2012;142:1009–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congress, U. Food Quality Protection Act. Public Law 1996:104–170 [Google Scholar]

- Council NR Pesticides in the Diets of Infants and Children ed^eds: National Academies Press; 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curl CL; Beresford SA; Fenske RA; Fitzpatrick AL; Lu C; Nettleton JA; Kaufman JD Estimating pesticide exposure from dietary intake and organic food choices: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Environ Health Perspect 2015;123:475–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curl CL; Porter J; Penwell I; Phinney R; Ospina M; Calafat AM Effect of a 24-week randomized trial of an organic produce intervention on pyrethroid and organophosphate pesticide exposure among pregnant women. Environ Int 2019:104957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani C; Oliboni L; Vanderlinde R; Bonatto D; Salvador M; Henriques J Phenolic content and antioxidant activities of white and purple juices manufactured with organically-or conventionally-produced grapes. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2007;45:2574–2580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton SB; Sandler DP; Blair A; Alavanja M; Beane Freeman LE; Hoppin JA Pesticide use and myocardial infarction incidence among farm women in the agricultural health study. J Occup Environ Med 2010;52:693–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckel RH; Jakicic JM; Ard JD; de Jesus JM; Houston Miller N; Hubbard VS; Lee IM; Lichtenstein AH; Loria CM; Millen BE; Nonas CA; Sacks FM; Smith SC Jr.; Svetkey LP; Wadden TA; Yanovski SZ 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:2960–2984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming LE; Gomez-Marin O; Zheng D; Ma F; Lee D National Health Interview Survey mortality among US farmers and pesticide applicators. Am J Ind Med 2003;43:227–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstermann U; Xia N; Li H Roles of Vascular Oxidative Stress and Nitric Oxide in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2017;120:713–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadis G; Mavridis C; Belantis C; Zisis IE; Skamagkas I; Fragkiadoulaki I; Heretis I; Tzortzis V; Psathakis K; Tsatsakis A; Mamoulakis C Nephrotoxicity issues of organophosphates. Toxicology 2018a;406–407:129-136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadis N; Tsarouhas K; Tsitsimpikou C; Vardavas A; Rezaee R; Germanakis I; Tsatsakis A; Stagos D; Kouretas D Pesticides and cardiotoxicity. Where do we stand? Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2018b;353:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannucci E; Colditz G; Stampfer MJ; Rimm EB; Litin L; Sampson L; Willett WC The assessment of alcohol consumption by a simple self-administered questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol 1991;133:810–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y; Chiu Y-H; Hauser R; Chavarro J; Sun Q Overall and class-specific scores of pesticide residues from fruits and vegetables as a tool to rank intake of pesticide residues in United States: A validation study. Environment International 2016;92:294–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland C; Bradman A; Gerona R; Patton S; Zakharevich I; Gunier RB; Klein K Organic diet intervention significantly reduces urinary pesticide levels in U.S. children and adults. Environ Res 2019;171:568–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P; Wang SY; Wang CY; Zheng Y Effect of cultural system and storage temperature on antioxidant capacity and phenolic compounds in strawberries. Food Chemistry 2011;124:262–270 [Google Scholar]

- Kadioglu E; Tacoy G; Ozcagli E; Okyay K; Akboga MK; Cengel A; Sardas S The role of oxidative DNA damage and GSTM1, GSTT1, and hOGG1 gene polymorphisms in coronary artery disease risk. Anatol J Cardiol 2016;16:931–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalender S; Kalender Y; Ogutcu A; Uzunhisarcikli M; Durak D; Agikgoz F Endosulfan-induced cardiotoxicity and free radical metabolism in rats: the protective effect of vitamin E. Toxicology 2004;202:227–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsikantami I; Colosio C; Alegakis A; Tzatzarakis MN; Vakonaki E; Rizos AK; Sarigiannis DA; Tsatsakis AM Estimation of daily intake and risk assessment of organophosphorus pesticides based on biomonitoring data - The internal exposure approach. Food Chem Toxicol 2019;123:57–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshk WA; Soliman NA; Abo El-Noor MM; Wahdan AA; Shareef MM Modulatory Effects of Curcumin on Redox Status, Mitochondrial Function, and Caspace-3 Expression During Atrazin-Induced Toxicity. Journal of biochemical and molecular toxicology 2014;28:378–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y; Je Y Flavonoid intake and mortality from cardiovascular disease and all causes: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2017;20:68–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E; Burnett CA; Lalich N; Cameron LL; Sestito JP Proportionate mortality of crop and livestock farmers in the United States, 1984-1993. Am J Ind Med 2002;42:410–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C; Barr DB; Pearson MA; Waller LA Dietary intake and its contribution to longitudinal organophosphorus pesticide exposure in urban/suburban children. Environ Health Perspect 2008;116:537–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C; Toepel K; Irish R; Fenske RA; Barr DB; Bravo R Organic diets significantly lower children's dietary exposure to organophosphorus pesticides. Environ Health Perspect 2006;114:260–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukowicz C; Ellero-Simatos S; Regnier M; Polizzi A; Lasserre F; Montagner A; Lippi Y; Jamin EL; Martin JF; Naylies C; Canlet C; Debrauwer L; Bertrand-Michel J; Al Saati T; Theodorou V; Loiseau N; Mselli-Lakhal L; Guillou H; Gamet-Payrastre L Metabolic Effects of a Chronic Dietary Exposure to a Low-Dose Pesticide Cocktail in Mice: Sexual Dimorphism and Role of the Constitutive Androstane Receptor. Environ Health Perspect 2018;126:067007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendis S; Thygesen K; Kuulasmaa K; Giampaoli S; Mahonen M; Ngu Blackett K; Lisheng L World Health Organization definition of myocardial infarction: 2008-09 revision. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millen BE; Abrams S; Adams-Campbell L; Anderson CA; Brenna JT; Campbell WW; Clinton S; Hu F; Nelson M; Neuhouser ML; Perez-Escamilla R; Siega-Riz AM; Story M; Lichtenstein AH The 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report: Development and Major Conclusions. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md) 2016;7:438–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KT; Blair A; Freeman LE; Sandler DP; Hoppin JA Pesticides and myocardial infarction incidence and mortality among male pesticide applicators in the Agricultural Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170:892–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates L; Cohen M; Braun L; Schembri A; Taskova R Reduction in urinary organophosphate pesticide metabolites in adults after a week-long organic diet. Environ Res 2014;132:105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osganian SK; Stampfer MJ; Rimm E; Spiegelman D; Manson JE; Willett WC Dietary carotenoids and risk of coronary artery disease in women. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;77:1390–1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razavi B; Hosseinzadeh H; Imenshahidi M; Malekian M; Ramezani M; Abnous K Evaluation of protein ubiquitylation in heart tissue of rats exposed to diazinon (an organophosphate insecticide) and crocin (an active saffron ingredient): role of HIF-1αα. Drug research 2015;65:561–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimm EB; Giovannucci EL; Stampfer MJ; Colditz GA; Litin LB; Willett WC Reproducibility and validity of a expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:1114–1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadeh AM; Farsakh NA; al-Ali MK Cardiac manifestations of acute carbamate and organophosphate poisoning. Heart 1997;77:461–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvini S; Hunter DJ; Sampson L; Stampfer MJ; Colditz GA; Rosner B; Willett WC Food-based validation of a dietary questionnaire: the effects of week-to-week variation in food consumption. Int J Epidemiol 1989;18:858–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsatsakis AM; Kouretas D; Tzatzarakis MN; Stivaktakis P; Tsarouhas K; Golokhvast KS; Rakitskii VN; Tutelyan VA; Hernandez AF; Rezaee R; Chung G; Fenga C; Engin AB; Neagu M; Arsene AL; Docea AO; Gofita E; Calina D; Taitzoglou I; Liesivuori J; Hayes AW; Gutnikov S; Tsitsimpikou C Simulating real-life exposures to uncover possible risks to human health: A proposed consensus for a novel methodological approach. Hum Exp Toxicol 2017;36:554–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchendu C; Ambali SF; Ayo JO; Esievo KAN Chronic co-exposure to chlorpyrifos and deltamethri pesticides induces alterations in serum lipids and oxidative stress in Wistar rats: mitigating role of alpha-lipoic acid. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2018; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Pesticide Data Program (PDP), annual sumary. URL: https://www.ams.usda.gov/datasets/pdp. Agricultural Marketing Service; 2000-2016. 2016; [Google Scholar]

- USDA. U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), 2016 Certified Organic Survey, September 2017. www.nass.usda.gov/organics. 2017;

- Vadhana MD; Arumugam SS; Carloni M; Nasuti C; Gabbianelli R Early life permethrin treatment leads to long-term cardiotoxicity. Chemosphere 2013;93:1029–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SY; Chen C-T; Sciarappa W; Wang CY; Camp MJ Fruit quality, antioxidant capacity, and flavonoid content of organically and conventionally grown blueberries. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2008;56:5788–5794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitacre DM Reviews of environmental contamination and toxicology ed^eds: Springer; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Yuan C; Spiegelman D; Rimm EB; Rosner BA; Stampfer MJ; Barnett JB; Chavarro JE; Rood JC; Harnack LJ; Sampson LK; Willett WC Relative Validity of Nutrient Intakes Assessed by Questionnaire, 24-Hour Recalls, and Diet Records as Compared With Urinary Recovery and Plasma Concentration Biomarkers: Findings for Women. Am J Epidemiol 2018;187:1051–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan C; Spiegelman D; Rimm EB; Rosner BA; Stampfer MJ; Barnett JB; Chavarro JE; Subar AF; Sampson LK; Willett WC Validity of a Dietary Questionnaire Assessed by Comparison With Multiple Weighed Dietary Records or 24-Hour Recalls. Am J Epidemiol 2017;185:570–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafiropoulos A; Tsarouhas K; Tsitsimpikou C; Fragkiadaki P; Germanakis I; Tsardi M; Maravgakis G; Goutzourelas N; Vasilaki F; Kouretas D; Hayes A; Tsatsakis A Cardiotoxicity in rabbits after a low-level exposure to diazinon, propoxur, and chlorpyrifos. Hum Exp Toxicol 2014;33:1241–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki NI Evaluation of profenofos intoxication in white rats. Nat Sci 2012;10:67–77 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.