Abstract

Instructor Talk—noncontent language used by instructors in classrooms—is a recently defined and promising variable for better understanding classroom dynamics. Having previously characterized the Instructor Talk framework within the context of a single course, we present here our results surrounding the applicability of the Instructor Talk framework to noncontent language used by instructors in novel course contexts. We analyzed Instructor Talk in eight additional biology courses in their entirety and in 61 biology courses using an emergent sampling strategy. We observed widespread use of Instructor Talk with variation in the amount and category type used. The vast majority of Instructor Talk could be characterized using the originally published Instructor Talk framework, suggesting the robustness of this framework. Additionally, a new form of Instructor Talk—Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk, language that may discourage students or distract from the learning process—was detected in these novel course contexts. Finally, the emergent sampling strategy described here may allow investigation of Instructor Talk in even larger numbers of courses across institutions and disciplines. Given its widespread use, potential influence on students in learning environments, and ability to be sampled, Instructor Talk may be a key variable to consider in future research on teaching and learning in higher education.

INTRODUCTION

Instructor Talk is a recently defined and promising variable for better understanding classroom dynamics and student outcomes (Seidel et al., 2015). The initial study of Instructor Talk in a purposefully chosen, single introductory biology course found more than 650 instances of noncontent language during recordings of class sessions during a single semester. These instances were termed “Instructor Talk” and were then categorized into five overarching categories or types of language that could be further dissected into 17 subcategories (see Table 1). Previous researchers have hypothesized that noncontent language that frames and rationalizes the use of active learning and other innovative teaching strategies is likely essential and prevalent in classrooms (e.g., Silverthorn, 2006; Science Education Initiative, 2013). Unexpectedly, however, the most prevalent categories of Instructor Talk in its initial research description—the category of Building the Instructor/Student Relationship and the category of Establishing Classroom Culture—were not about framing pedagogy, but rather were grounded in building relationships in the classroom. While most often asserted as key to implementation of active-learning strategies, language related to Explaining Pedagogical Choices was far less prevalent in that initial description than was widely expected. The least prevalent categories of Instructor Talk in the initial research description in a single course were Sharing Personal Experiences and Unmasking Science. While there may be variations among instructors in the extent to which they share more personal aspects of themselves and their lives, it was surprising that Unmasking Science—which includes being explicit about the nature of science and discovery and highlighting the diverse perspectives of the people who do science—was not more prevalent.

TABLE 1.

Instructor Talk framework: Categories and subcategories reprinted from Seidel et al. (2015)

| Category | Subcategory |

| Building the Instructor/Student Relationship | Demonstrating Respect for Students |

| Revealing Secrets to Success | |

| Boosting Self-Efficacy | |

| Establishing Classroom Culture | Preframing Classroom Activities |

| Practicing Scientific Habits of Mind | |

| Building a Biology Community among Students | |

| Giving Credit to Colleagues | |

| Indicating That It Is Okay to Be Wrong or Disagree | |

| Explaining Pedagogical Choices | Supporting Learning through Teaching Choices |

| Using Student Work to Drive Teaching Choices | |

| Connecting Biology to the Real World and Career | |

| Discussing How People Learn | |

| Fostering Learning for the Long Term | |

| Sharing Personal Experiences | Recounting Personal Information/Anecdotes |

| Relating to Student Experiences | |

| Unmasking Science | Being Explicit about the Nature of Science |

| Promoting Diversity in Science |

So, how might this recently described noncontent instructor language be influential in teaching and learning? Three divergent lines of research from multiple disciplines would all suggest that noncontent language used by instructors in classrooms may influence student engagement and learning and be a key variable in pressing issues in science education. In this article, we explore how the noncontent language of Instructor Talk could impact student success through stereotype threat; influence the culture of the learning environment through instructor immediacy; and/or support instructor implementation of effective, evidence-based teaching strategies.

First, previous research in social psychology has demonstrated that language can have dramatic effects in student performance on high-stakes assessments (e.g., Steele and Aronson, 1995; Croizet and Claire, 1998; Spencer et al., 1999). While originally described in a laboratory setting, this phenomenon of “stereotype threat” may be an underappreciated variable influencing classrooms widely, potentially driving achievement gaps that have been identified for some student populations in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) courses (Lauer et al., 2013; Madsen et al., 2013; Eddy and Hogan, 2014). Stereotype threat occurs when individuals who identify with a group sense that there is a negative stereotype associated with being affiliated with that group, which can then lead to underperformance in high-stakes situations (Steele and Aronson, 1995). While stereotype threat can be induced in a variety of ways, noncontent language used by instructors is one candidate variable for how negative stereotypes and expectations could be conveyed in classrooms. Importantly, multiple researchers have gone on to demonstrate that signaling that stereotypes are not embraced, either in laboratory investigations or in classroom situations, can combat underperformance due to stereotype threat (Croizet and Claire, 1998; Spencer et al., 1999). In STEM courses in particular, the use of value affirmation activities—engaging students in exploring their personal values in the course context itself—have shown preliminary promise as interventions to reduce stereotype threat (Miyake et al., 2010; Jordt et al., 2017; Lewis et al., 2017). Given that students spend dozens of hours in course environments where learning is choreographed by the instructor’s language, one wonders how noncontent language like Instructor Talk might either contribute to or mitigate affective phenomena like stereotype threat.

Second, the relationship between instructor and student has long been acknowledged as an important aspect of teaching and learning at all cognitive levels, but has perhaps received less attention in higher education. In particular, communication studies researchers, as well as social psychologists, have explored the phenomenon of “instructor immediacy,” which represents the apparent social distance between an instructor and his or her students (Mehrabian, 1971). Instructor immediacy appears to be related to a variety of instructor characteristics, including nonverbal behaviors (e.g., gestures, location in classroom, movement in classroom, facial expressions) and verbal behaviors (e.g., tonality of voice, use of humor, use of students’ names). Research on the classroom variable of instructor immediacy has revealed correlations between instructor immediacy and some aspects of learning (Witt and Wheeless, 2001), though more investigations are needed (Estrada et al., 2018). More recent studies published since the initial Instructor Talk investigation have increased interest in this classroom variable. In one study, “teacher trust” was shown to be correlated with student success for Black college students (McClain and Cokley, 2017). In addition, there has been an increased focus on the role of microaggressions in classrooms and how this language may negatively impact students’ sense of belonging, motivation, and even their experience of stereotype threat (reviewed in Harrison and Tanner, 2018). Given the central role of language in the social contract of teaching and learning, one wonders how the overall extent of Instructor Talk present in a course, as well as the categories of noncontent language most often used, may influence instructor immediacy in higher education classrooms.

Third, active-learning pedagogies have been repeatedly demonstrated to produce superior learning gains with large effect sizes compared with lecture-based pedagogies (e.g., Halloun and Hestenes, 1985; Hake, 1999; Freeman et al., 2014). However, the potential for student resistance to any teaching strategies beyond traditional lecture may discourage some instructors from adopting these more effective, evidence-based teaching approaches (reviewed in Seidel and Tanner, 2013). While much is yet to be discovered about the origins of student resistance, one might hypothesize that the noncontent language used by instructors in introducing new teaching and learning strategies could either mitigate or cultivate student resistance in classrooms (Finelli et al., 2018). Additionally, the mechanisms by which active-teaching approaches produce higher learning gains is just beginning to be investigated in more detail (e.g., Freeman et al., 2014). Some would assert that active-learning approaches are more efficacious due to cognitive and conceptual mechanisms, whereby teachers are more effective cognitive coaches and students are more effectively conceptually challenged. Relatedly, others would suggest that active learning promotes student behaviors—including deliberative practice and connecting new ideas to prior ideas—that would drive neural synaptic plasticity, which is thought to underlie learning and memory (reviewed in Owens and Tanner, 2017). However, another rarely asserted potential mechanism of the gains achieved through active learning is a shift in the social psychology of students, namely increases in their sense of belonging, their sense of self-efficacy, and their development of a science identity due to increased classroom interactions (reviewed in Trujillo and Tanner, 2014). Instructor Talk—depending on the category of language being used—could be a key variable in each of these candidate mechanisms.

Because Instructor Talk is an underexplored aspect of science classroom environments in higher education that has the potential to influence student motivation, engagement, resistance, learning, and a host of other outcomes, we embarked upon investigating the presence and character of noncontent language in dozens of novel contexts to address the following research questions: To what extent is Instructor Talk even present in other courses? If present, to what extent can instances of Instructor Talk be characterized with the existing Instructor Talk framework? What new categories, subcategories, and novel flavors of Instructor Talk emerge from investigations of new classroom contexts? And how might Instructor Talk, possibly a key variable in promoting student success, be more efficiently sampled and analyzed to enable large-scale investigation of noncontent language in hundreds of classrooms?

METHODS

This investigation of Instructor Talk in novel contexts included two distinct studies. The first study—Whole-Course Analysis of Instructor Talk in New Courses—focused on testing the utility of the current Instructor Talk framework in characterizing noncontent language in novel course settings by analyzing all instances of Instructor Talk in all class sessions in eight new course contexts. The second study—Developing a Sampling Method for Analysis of Instructor Talk—evaluated a method for sampling a subset of Instructor Talk in courses to enable larger-scale studies of Instructor Talk in the future. Both studies used the Instructor Talk framework, and the methods associated with each are detailed in the following sections.

Study 1: Whole-Course Analysis of Instructor Talk in New Courses

Study Design and Approach.

The aim of this study was to investigate the extent to which the Instructor Talk framework was applicable in classrooms other than the initial one characterized (Seidel et al., 2015). Below, we describe the methods used to investigate Instructor Talk in eight community college biology classrooms, including 1) identifying participants and collecting Instructor Talk data; 2) defining, categorizing, and quantifying instances of Instructor Talk; 3) testing the applicability of the Instructor Talk framework in these new contexts; 4) developing an emergent framework for previously undetected “Negatively Phrased” Instructor Talk; and 5) measuring interrater reliability of our coding. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at San Francisco State University under protocol number E14-141.

Identifying Collaborators and Collecting Instructor Talk Data.

To obtain a data set to test the applicability of the current Instructor Talk framework in novel contexts, we invited community college instructors who met the following criteria to collaborate on the study: 1) they had completed a specific 5-day professional development workshop in scientific teaching; 2) they were teaching at least one biology lecture course during the term of the study (Spring 2014); and 3) they taught in an institution on the quarter system. This was a sample of both convenience and trust. While it is becoming increasingly common for instructors to video- or audio-record a class session for professional development or research, it requires a higher level of trust to share recordings of an entire course and have all statements analyzed by a team of researchers. Trust was accomplished by assurance of anonymity, with only the primary researcher—a scientific trainee—having access to identified data and codes that could reveal which language came from which instructor. Additionally, this sample population was a benefit in terms of moving beyond a single 4-year university classroom and answering the recent call to broaden participation in biology education research to include more community college classrooms (Schinske et al., 2017). Each collaborator was given a handheld audio recorder and was asked to record every class session during the 11-week quarter term. Unrecorded class sessions, which were less than 20% of total class sessions, were attributed to in-class exam days in which recordings were not made or by instructor user errors with the audio recorder.

Defining and Categorizing Instances of Instructor Talk.

Instructor Talk was categorized as previously described (Seidel et al., 2015). Briefly, a statement was considered Instructor Talk if it was: 1) spoken out loud by an instructor, 2) addressed to the class as a whole, 3) not specific to course content, 4) not an analogy for course content, and 5) not focused on course logistics or agenda items. To identify instances of Instructor Talk, we listened to all audio recordings of each class session for each instructor. Statements that met the criteria were transcribed by one of the coders (T.A.N.) and later coded as Instructor Talk instances. To avoid missing instances of Instructor Talk, the coder transcribed inclusively, and some instances were later excluded as logistics or content.

For characterizing the types and prevalence of Instructor Talk, each Instructor Talk instance was coded into one of five categories described previously (see Table 1; Seidel et al., 2015; and detailed working rubrics in Appendix Table A in the Supplemental Material). Although rare instances could have fit into more than one category, we chose the single category that would be a best fit the particular instance through consensus of multiple coders. If an instance of Instructor Talk did not fall into one of the five previously developed categories or 17 subcategories, it was marked as “Other.” After all instances of Instructor Talk were examined, major themes from these distinctive instances that fell into the Other group were analyzed and discussed. From these Other Instructor Talk instances, new categories and subcategories were collaboratively developed using an approach similar to the development of the previous framework (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). Only one new subcategory within the existing Instructor Talk Framework—Fostering Wonder—in the category of Unmasking Science was detected in these novel contexts.

Developing a Framework for Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk.

In analyzing the Other Instructor Talk instances, a new form of Instructor Talk not previously detected in the initial study was evident in this larger number of courses. This noncontent language used by instructors included language that appeared to be discouraging to students or at odds with promoting learning. To categorize this new type of Instructor Talk, we developed a parallel framework that we have chosen to term the “Negatively Phrased” Instructor Talk framework (see Table 4 later in this article). The initial framework of Instructor Talk (Seidel et al., 2015) will now be referred to as the “Positively Phrased” Instructor Talk framework. While Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk included instances of noncontent language that could discourage students or compromise class culture, as well as instances that conveyed negative views about teaching and learning, it also included instances of self-effacing talk by the instructor. If coders were uncertain whether an instance was considered Negatively Phrased, it was assumed to be Positively Phrased.

TABLE 4.

Negatively Phrased and Positively Phrased Instructor Talk frameworks

| Negatively Phrased category | Negatively Phrased subcategory | Positively Phrased subcategory | Positively Phrased category |

| Dismantling the Instructor/Student Relationship | Ignoring Student Challenges | Demonstrating Respect for Students | Building the Instructor/Student Relationship |

| Assuming Poor Behaviors from Students | Revealing Secrets to Success | ||

| Making Public Judgments about Students | Boosting Self-Efficacy | ||

| Disestablishing Classroom Culture | Expecting Students to Know What to Do | Preframing Classroom Activities | Establishing Classroom Culture |

| Practicing Scientific Habits of Mind | |||

| Discouraging Community Among Students | Building a Biology Community among Students | ||

| Criticizing Colleagues | Giving Credit to Colleagues | ||

| Encouraging Only the Right Answer | Indicating That It Is Okay to Be Wrong or Disagree | ||

| Compromising Pedagogical Choices | Expressing Doubt in Pedagogical Choice | Supporting Learning through Teaching Choices | Explaining Pedagogical Choices |

| Using Convenience to Drive Teaching Choices | Using Student Work to Drive Teaching Choices | ||

| Connecting Biology to the Real World and Career | |||

| Teaching to a Subset of Students | Discussing How People Learn | ||

| Focusing on the Grade/Short Term | Fostering Learning for the Long Term | ||

| Sharing Personal Judgment | Sharing Self-Judgment/Self-Pity | Recounting Personal Information/Anecdotes | Sharing Personal Experiences |

| Distancing from Student Experiences | Relating to Student Experiences | ||

| Masking Science | Being Implicit about the Nature of Science | Being Explicit about the Nature of Science | Unmasking Science |

| Intimidating Students from Science | Promoting Diversity in Science | ||

| Fostering Wonder |

Quantifying Instances of Instructor Talk.

To compare the prevalence and nature of Instructor Talk between Instructors A and B from the initial Seidel et al. (2015) study and the eight instructors in the new whole-course data set, we developed two metrics. First, because the community college instructors had varying numbers of class session lengths and total hours of recording, a rate of Instructor Talk (instances per hour) was calculated for each instructor and class session. Because the Seidel et al. (2015) study described only the total number of quotes throughout the semester-long term and the number of instances per class session, we calculated rates of Instructor Talk for Instructors A and B, based on previously published data (Seidel et al., 2015). Second, we calculated the percentage of class sessions within each course that evidenced each category of Instructor Talk as an additional metric to describe prevalence.

Measuring Interrater Reliability.

To determine the accuracy of assigned Instructor Talk categories and subcategories in the whole-course data set, a second coder (K.D.T.) familiar with Instructor Talk categorized 10% of the data set both at the category and subcategory levels. When deciding whether instances of Instructor Talk were considered Negatively Phrased, we coded instances to agreement of researchers involved in coding. Whenever it was questionable whether an instance was Positively Phrased or Negatively Phrased, we coded the instance as Positively Phrased. At the category level of the initial Positively Phrased Instructor Talk framework, the two coders (T.A.N. and K.D.T.) showed 80% agreement, and at the subcategory level, 73% agreement. Within the Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk framework, the two coders showed 95% agreement at the category level, and 83% agreement at the subcategory level.

Reanalyzing the Original Study for Newly Emergent Categories and Subcategories.

To determine the extent to which the newly emergent subcategory of Fostering Wonder within the Unmasking Science category and new categories of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk were present in the original study, we used a two-phase approach. First, two coders who were not involved in the original study (M.M. and C.D.H.) individually reanalyzed all 666 instances from the original study, coding each instance as either Positively Phrased or Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk. When the instance was determined to be Positively Phrased, the coders disregarded it and moved on to the next instance, unless it could be coded into the emergent subcategory, Fostering Wonder. When an instance was identified as Negatively Phrased, coders assigned it a category and a subcategory. Coders then discussed these decisions with a third coder (S.B.S.) who had been involved in the original study to reach complete consensus on the categories and subcategories for all instances.

In a second phase of analysis, two coders (M.M. and C.H.) reviewed all 29 original transcripts from the Seidel et al. (2015) study to search for instances of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk that might have previously been overlooked and not yet included in the 666 instances that had already been reanalyzed. Instances identified by either coder were collected. Again, these two coders and the same third coder (S.B.S.) discussed each instance and reached complete consensus on a category and subcategory assignment using the newly developed Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk framework (see Table 4 later in this article).

Comparative Statistical Analyses.

Comparative statistical analyses were performed to compare the extent of instructors’ use of Instructor Talk. We performed one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the use of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk among instructors, followed by Tukey-Kramer pairwise comparisons. We used the same approach to compare the use of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk among instructors.

Study 2: Developing a Sampling Method for Analysis of Instructor Talk

Developing a Strategy to Measure Instructor Talk in Large Numbers of Courses.

Due to the time-consuming nature of identifying and categorizing Instructor Talk instances, we aspired to develop a method for sampling a subset of time in a course to gauge and characterize use of Instructor Talk. Based on preliminary analyses of the data set collected in the original Instructor Talk study (Seidel et al., 2015), we hypothesized that the first 15 minutes of class time would contain a representative or enriched amount of overall Instructor Talk compared with later time windows during a class session. In addition, we hypothesized that Instructor Talk would be more prevalent earlier in the course term, but we also aspired to sample at least two class sessions during the term. As such, we investigated the use of a sampling strategy that examined the presence and nature of Instructor Talk in the first 15 minutes of the first recorded class session and in the first 15 minutes of a class session in the middle of the term.

To test these predictions, we conducted a systematic analysis of Instructor Talk using this sampling method on the original Instructor Talk data set (Seidel et al., 2015), as well as on the whole-course data sets from the eight additional courses in study 1, described earlier. For these analyses, we included any recorded course with >90% of expected class time recorded. For the original study, we compared the total amount of Instructor Talk and the total amount of each individual category in the first 15 minutes of class session with the anticipated 33.3% that would be expected if Instructor Talk instances were equally distributed throughout an individual class session (which for this course was 50 minutes). For the eight additional whole-course data sets, we similarly compared the sampled amount Instructor Talk in the first 15 minutes of a class session with the anticipated 14.3% that would be expected if Instructor Talk instances were equally distributed throughout these class sessions (which were 105 minutes). After confirming that this method yielded representative or enriched samples of Instructor Talk, investigation of larger numbers of courses became possible.

Identifying Collaborators and Sampling Instructor Talk across a Large Number of Courses.

To investigate Instructor Talk using the developed sampling method in a large number of courses, we recruited instructor collaborators in Spring 2015 from the biology departments of multiple community colleges and a comprehensive, urban university. All instructors who had completed a specific 5-day professional development workshop in scientific teaching were invited to collaborate no matter what course type they were teaching and whether their institution was on a semester or quarter system. In total, 56 of 59 invited biology instructors agreed to collaborate. These 56 biology instructors represented 14 community colleges and the comprehensive, urban university. Courses with incomplete transcripts due to recording errors or guest lectures were omitted from analysis. This led to the exclusion of three instructors, leaving 53 instructors in this sampled data set. Of these instructors, 31 identified as women and 22 identified as men, and 35 of the instructors had more than 5 years of teaching experience. Instructors from the university included 13 lecturers and 14 tenured or tenure-track faculty. Of the community college instructors, 18 identified as part-time and eight as full-time. Altogether, these 53 instructors taught and recorded 61 courses with six instructors teaching two courses and one teaching three courses. Biology major and nonmajor courses accounted for 31 and 30 of the courses analyzed, respectively. Class size varied from 4 to 287 students.

As in study 1, courses were recorded throughout the term using a handheld Sony audio recorder. Two samples from audio files for each course were sent to a private company for transcription. These samples were the first 15 minutes from the first recording from each course (referred to as the “early-course sample”) and from a second class session that occurred approximately halfway through the course term (e.g., first class session of week 8 for a 15-week semester-system course or week 5 for a 10-week quarter-system course; referred to as the “midcourse sample”). These two 15-minute samples from each course were analyzed to quantify and characterize Instructor Talk for the 53 instructor collaborators in their 61 courses. Early-course sample and midcourse sample means were compared using a two-tailed t test.

Identifying and Coding Instructor Talk Instances within the 61 Sampled Courses.

Initial identification of Instructor Talk instances and coding was performed by one researcher (C.D.H.). Subsequently, three additional researchers (A.M.E., K.L., K.S.L.) independently coded one-third of the transcripts each. Differences in coding (∼15% of quotes) were discussed and resolved by coming to a consensus among all coders, and a final code was assigned by one of the authors (C.D.H.).

Measuring Interrater Reliability.

Interrater reliability for this sampled data set was checked to confirm the accuracy of coding. A second coder who had not been involved with the initial coding process (K.D.T.) was given 10% of the data set to code. Fifty-one quotes were chosen by a random number generator and coded. Both percent agreement and Cohen’s kappa were calculated to assess interrater reliability, as recommended by McHugh (2012). At the category level, the raters showed 83% agreement, and at the subcategory level, 75% agreement. To determine the statistical reliability of the agreement, we measured the Cohen’s kappa for the category (0.763) and subcategory levels (0.788). These values represent substantial agreement between raters as interpreted by McHugh (2012).

RESULTS

These studies of Instructor Talk were designed to identify and characterize the noncontent language used by college biology instructors in multiple novel course contexts. The Results are divided into two sections for the two distinct studies described in the Methods: 1) Study 1: Whole-Course Analysis of Instructor Talk in New Courses, which focused on testing the utility of the current Instructor Talk framework in novel course settings by analyzing all instances of Instructor Talk in all class sessions in eight new course contexts; and 2) Study 2: Developing a Sampling Method for Analysis of Instructor Talk, which evaluated a method for sampling a subset of Instructor Talk in 61 courses taught by 53 different instructors.

Study 1: Whole-Course Analysis of Instructor Talk in New Courses

Whole-Course Analysis of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk in Eight Community College Courses.

To investigate the applicability of the original Instructor Talk framework presented in Seidel et al. (2015) in novel course contexts, we performed whole-course analysis of Instructor Talk from eight community college classrooms. Across the eight instructors and courses, audio was recorded and transcribed for 135 class sessions in total and 2021 instances of Instructor Talk were identified. Instructors were given pseudonyms, and each contributed data from the following number and percentage of class sessions from their courses: Gordon (n classes = 14, percent recorded = 61%), Luisa (11, 100%), Helen (21, 95%), Simone (16, 84%), Loretta (17, 85%), Ana (17, 85%), Jerry (22, 91%), and Mario (19, 86%). Example quotes for Positively Phrased Instructor Talk can be found in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Example instances of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk

| Subcategory | Example instance | |

|---|---|---|

| Building the Instructor/Student Relationship | Demonstrating Respect for Students | “I’m not going to give you 20 pages to read over the weekend. It’ll be short. Maybe one page, not 20 pages. No. Not 20 pages! 1–1.5 pages. It’s doable. The point is I’ll definitely do something that is doable, not impossible for you because everybody has other things to do, other classes, personal life, job, so I understand that as well.”—Study 1: Whole Course |

| “And in terms of textbooks, I don’t have you buy a book. I try to keep it on the cheap for you, because I know you’re all sort of literally starving students with tuition and having to take extra semesters and all of that.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Revealing Secrets to Success | “I can’t emphasize enough that going over those index cards and after that, getting a chance to talk to somebody else about this biology, even if it’s only about some of the stuff we studied, I think that’s really going to serve you well.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “Those of you who haven’t seen it, look at it. Start prepping. Start thinking about it. And what I recommend doing is first just thinking about the topics, and jotting down notes; building and sort of brainstorming. And then you can start sort of framing, and then you’re going to want to get the flow.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Boosting Self-Efficacy | “So I’ve seen all of you working hard in this class I’ve seen all of you reading critically and reading well through your reading reflections that I’ve been reading and I’ve seen you addressing sort of broad open-ended questions and making arguments for things in your index cards, so I know that you’re very well set up to do well on this so, if you can bring all those skills to bear, you’ll be in very very good shape.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “So you have done a lot of writing at this point. I’m sure it feels like it. So I want to take a few minutes at the beginning of class to highlight some of your progress, because I think it’s really easy to just keep doing it and keep doing it and not realize that you’re actually making progress and that things are looking good.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Establishing Classroom Culture | Preframing Classroom Activities | “Take a moment now to check in with somebody nearby, and compare what you’ve got, and make sure you’ve got something to fill in, some example to put in each of these locations. Because what I’ll do in a moment is I’ll randomly call on people to offer an example for each part of the table.”—Study 1: Whole Course |

| “One thing I like to do in these classes is have people talk to each other and discuss problems, and take apart problems that I show. So, just to get started, because you’re going to be talking to each other a lot, I’d like to start with this simple index card exercise that I always do.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Practicing Scientific Habits of Mind | “That was really fun to read because it’s interesting to see people really challenging the text and not just taking for granted what they’re reading but interacting with it and saying like, ‘Well Ok, what do I really buy of this? What evidence do I take away?’”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “You’re going to use the evidence and ask questions with your card and be skeptical. Ask those questions.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Building a Biology Community among Students | “So, if you don’t have a note card, this is a great time to meet your neighbor. Introduce yourself and ask them if you can borrow a note card, and pay them back next week.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “We’re going to first try to understand this by having a common experience, because it’s often helpful to do something together here in class and then talk about it, because then we all have the same experience.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Giving Credit to Colleagues | “I wrote my outline, I didn’t know exactly how (the guest lecturer) was going to present it. When you have a guest lecturer, you let them present the material. I just told her what she was going to present. And I know it’s a little different but it’s actually really cool to get other people’s way of explaining things and all of that in my opinion.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “It’s also written by one of my colleagues, so give her some props for that. She took my notes and a bunch of the other instructors’ notes and put them together—aggregating, as it were. Very well written.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Indicating It Is Okay to Be Wrong or Disagree | “These are the kind of activities we’re going to do all the time. So, I want you do like they did, and take a risk and go up there and who cares if it’s wrong, now’s the time to know if you have misconceptions or if something isn’t right.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “Do you agree or disagree, and why? And this is written so that they’re actually—neither answer is completely technically correct. So, you are totally advised to argue one way or the other on it.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Explaining Pedagogical Choices | Supporting Learning through Teaching Choices | “All of these are tools to try to get you a little bit more comfortable with something that you can’t normally see, so having an animation is really helpful for a lot of students.”—Study 1: Whole Course |

| “All right, learning outcomes. I’ll try and start classes with learning outcomes. These are the things that I am going to be testing on. These are the things that after you—after each class, and you leave this room, I want you to know.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Using Student Work to Drive Teaching Choices | “In a big class like this I usually don’t get to talk to every student every day when we have class. But if I have you write something down really quick, then I can actually hear from all of you, and it gives me a much more equal and equitable feel for what’s going on in the class and what’s going on in your heads. So it allows me to hear from everybody and adjust to what’s going on in the class and adjust to your needs.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “I looked over your index cards from last week, the review card, where I asked you guys what the difference is between DNA genes. And, again, came up with some common mistakes or misconceptions that people wrote down. So, I wanted to kind of go over a few of the more common ones here.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Connecting Biology to the Real World and Career | “Okay, so you can be an advocate for yourself and know how long it takes to get over a cold and how long it takes to get over a flu. And go see the doctor if you’re really nervous but make sure you ask the questions, ‘Oh do you actually see evidence of a bacterial infection?’ And watch their eyes go.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “The first semester I taught, we did extra credit, and I had you—I had people review an article from the news because I find that one of the things that I hope that you get out of this class, if you get nothing else out of this class, is a little bit more awareness of how science impacts your life.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Discussing How People Learn | “I think we learn best by our own experiences, more so than me talking about it. So experience all this.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “Some of the old ways that we think learning works or happens research is showing are not really very effective methods. For example, if I just stand up here for 2 hours and talk at you and lecture to you, and you sit there and listen to me, only ∼10% of what I say gets into your head. That’s a really, really small amount of information. And so, there’s a lot of new research out there, educational research that shows that there are different ways that make learning more effective.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Fostering Learning for the Long Term | “I like this example for a number of reasons. Because it gets at our theme of learning I guess for this first day and it relates to our goal to have authentic and lasting learning.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “If you couldn’t remember at the end of the class what you learned in the beginning, then the learning is really quite useless, right? Because we really hope that you’ll remember 5 years from now.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Sharing Personal Experiences | Recounting Personal Information/Anecdotes | “Sometimes, I don’t know if you guys have ever had this happen, but sometimes when I’m making salad at home and I cut open tomatoes, I see the inside of tomatoes, sometimes the seeds have started sprouting.”—Study 1: Whole Course |

| “When it was raining, like the day after, my allergies just flare up.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Relating to Student Experiences | “I’m definitely somebody who, when I read a textbook, I definitely glaze over. I just end up reading the same paragraph 50 times before I even understand it at all.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “Everything is anonymous, so when I was a student, I hated to raise my hand and answer questions. This makes you not have to do that. Everybody answers the question and no one has to be like nervous to talk in front of the class, so I think it’s amazing.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Unmasking Science | Being Explicit about the Nature of Science | “It is absolutely a fool’s errand to think that politics, morals, etcetera, don’t play a role in the field of science.”—Study 1: Whole Course |

| “Part of science is standing on the shoulders of giants. Has anybody heard that term before? That means we are not the first ones that have started learning stuff, right? We are using the knowledge of other people.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Promoting Diversity in Science | “In the past, science has not been a terribly diverse place. And that’s not because it’s not meant to be a diverse place. In fact, there are a lot of well-known studies that show that teams of scientists from diverse backgrounds are better problem-solvers than a team of homogeneous scientists or from similar backgrounds. So, it turns out this is a critical piece to science.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “And not only that, you should be able to communicate effectively with diverse groups as well.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Fostering Wonder | “Every time I see the inside of the heart, see the AV valves, the semilunar valves, it just, I think they’re amazing to look at, and see the real thing.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “I think the labs are really, really cool, so I’m excited about them. And I’m excited for you guys to get to go through them.”—Study 2: Sampling Method |

Fostering Wonder: An Emergent Subcategory of Instructor Talk.

While the vast majority of the Instructor Talk identified in these eight courses could be categorized with the established Instructor Talk framework (87.7%; n = 1772/2021), some instances were coded as Other, because they could not be characterized as belonging to existing categories or subcategories. To characterize a subset of these Other instances (8.3%; n = 19/249), we created a new subcategory of Unmasking Science—Fostering Wonder—and added it to the original Instructor Talk framework. This new subcategory included instances that encouraged student excitement and curiosity about science. These included general statements about the wonders of science and interesting science ideas not directly related to course content. Below are two example instances coded in the new Fostering Wonder subcategory, two more can be found in Table 2:

“This is like the coolest area of research in my opinion right now, because it’s all new ways to look for disease probabilities. They’re finding really cool stuff.”—Loretta

“First let me give you the interesting biology fact of the day. It is not possible to tickle yourself. You can’t. You can, but you can’t laugh, you can’t enjoy it. Because your brain predicts the tickle happening before you actually do it.”—Mario

Overall Instructor Talk Use in Novel Course Contexts Compared with the Original Course Description using Whole-Course Analyses.

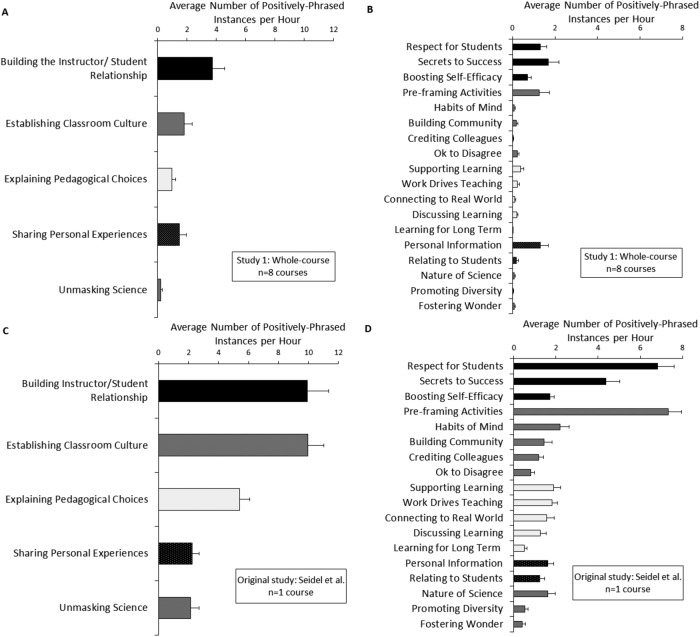

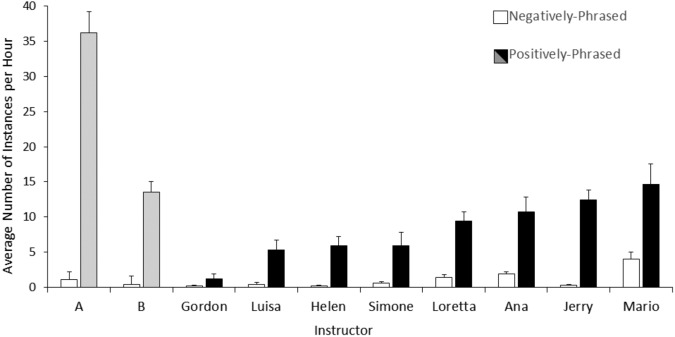

The amount and type of Instructor Talk found in the novel eight course contexts as compared with the original Seidel et al. (2015) study is shown in Figure 1 and Table 3. To make these comparisons, we needed to account for differences in class session length among the courses under study. As such, we calculated the number of Instructor Talk instances per unit time and have presented these Instructor Talk measurements as instances per hour in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Prevalence of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk categories and subcategories in eight novel courses compared with the original Instructor Talk course. The average number of instances per hour for the whole-course analyses for eight novel courses and instructors for the categories (A) and subcategories (B) of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk. Data from the original description of Instructor Talk in a single course (Seidel et al., 2015) at the category level (C) and subcategory (D) levels are reprinted for comparison. Patterns and colors of bars represent associations between subcategories and their parent categories: Building the Instructor/Student Relationship (black bars), Establishing Classroom Culture (hatched bars), Explaining Pedagogical Choices (light gray bars), Sharing Personal Experiences (black bars with dots), and Unmasking Science (gray bars). Error bars represent SEM.

TABLE 3.

Quantification of class sessions containing category of Instructor Talk in course of the whole-course study

| Overall Instructor Talk | Building the Instructor/Student Relationship | Establishing Classroom Culture | Explaining Pedagogical Choices | Sharing Personal Experiences | Unmasking Science | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous study | Instructor A (n = 17) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 76% |

| Instructor B (n = 8) | 100% | 88% | 100% | 75% | 38% | 38% | |

| Class sessions containing category | Gordon (n = 14) | 50% | 36% | 14% | 21% | 21% | 0% |

| Luisa (n = 11) | 100% | 82% | 82% | 27% | 36% | 9% | |

| Helen (n = 21) | 100% | 95% | 95% | 43% | 81% | 14% | |

| Simone (n = 16) | 100% | 94% | 25% | 63% | 69% | 19% | |

| Loretta (n = 17) | 100% | 88% | 100% | 88% | 65% | 18% | |

| Ana (n = 17) | 100% | 100% | 65% | 76% | 88% | 29% | |

| Jerry (n = 20) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 85% | 80% | 20% | |

| Mario (n = 19) | 100% | 100% | 37% | 37% | 95% | 74% | |

| Average ± SEM | 94 ± 6% | 87 ± 8% | 65 ± 12% | 55 ± 9% | 67 ± 9% | 23 ± 8% |

Each of the five categories of Instructor Talk was detected in each of the eight novel course contexts, with the exception of one category (Unmasking Science), which was absent for only one instructor (Gordon). However, there were differences in the relative frequency of category use across the eight instructors as compared with the original Seidel et al. (2015) data set (see below). The two most prevalent Instructor Talk categories were the same in these new course contexts as in the original study: Building the Instructor/Student Relationship followed by Establishing Classroom Culture. However, the relative rate of use of Instructor Talk in these categories was lower on average in the new course contexts (3.7 and 1.8 instances per hour, respectively) than they were in the original study (9.9 and 10.0 instances per hour, respectively) (Figure 1, A and C). In contrast to the original Seidel et al. (2015) study, in this study, Sharing Personal Experiences was the third most prevalent category in the novel course contexts, followed by Explaining Pedagogical Choices. Unmasking Science was the least prevalent category in all analyses and was rarely detected in the novel course contexts (Figure 1, A and C). In addition, all 17 subcategories of the five major categories of Instructor Talk were present in the whole-course analyses of the eight novel course contexts (Figure 1, B and D).

Comparison of Instructor Talk across Individual Instructors: Overall Production, Category Use, and Presence over the Course Term.

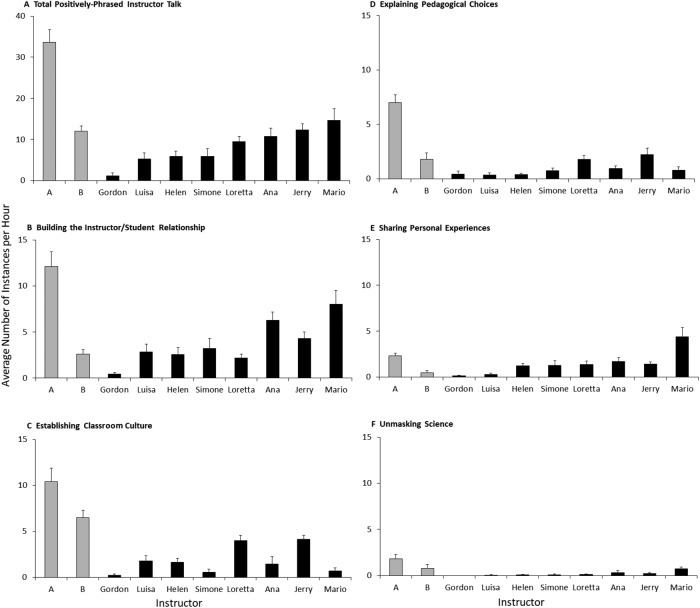

Instructor Talk analyses for each individual instructor from the eight novel course contexts, as well as for the two instructors in the original Seidel et al. (2015) study, are shown in Figures 2 and 3 and Table 3. Rates of Instructor Talk across instructors ranged from 1.4 instances per hour to 37.3 instances per hour (overall) or 1.2 instances per hour to 36.2 instances per hour (Positively Phrased Instructor Talk only). By all measures, Instructor A from the Seidel et al. (2015) study used more Instructor Talk than any other instructor examined to date (37.3 instances per hour; one-way ANOVA Fs = 22.255, p = 1.21E-23; and Tukey-Kramer test). Instructor B from the original study appeared more similar to most of the instructors in the novel course contexts. Among these instructors, Mario used the most overall Instructor Talk (18.7 instances per hour) and tended to produce the highest rates in several categories of Instructor Talk, whereas Gordon consistently used Instructor Talk the least (1.18 instances per hour) and had the lowest rates of use across most categories (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of rates of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk at the category level across eight courses. The rates of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk (average number of instances per hour across class sessions) were measured for each of the eight instructors in the whole-course analysis (black bars) and for the two instructors in the original Instructor Talk study (gray bars; Seidel et al., 2015) for (A) total Positively Phrased Instructor Talk, (B) Building the Instructor/Student Relationship, (C) Establishing Classroom Culture, (D) Explaining Pedagogical Choices, (E) Sharing Personal Experiences, and (F) Unmasking Science. Error bars represent SEM.

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk usage throughout the term across eight courses. Rates (instances per hour) of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk were calculated for each class session in each of the eight courses in the whole-course analysis and are shown for each instructor: (A) Gordon, (B) Luisa, (C) Helen, (D) Simone, (E) Loretta, (F) Ana, (G) Jerry, and (H) Mario. ND (no data) indicates no recording was available for the class session.

When the relative presence of Instructor Talk during each class session over the course term was analyzed, seven of the eight instructors in novel course contexts—as well as both Instructor A and Instructor B from the original study—used Instructor Talk in every recorded class session (see Figure 3 and Table 3), evidencing widespread use of Instructor Talk. The one exception, Gordon, used Instructor Talk in only 50% of recorded classes (Figure 3 and Table 3). The use of Instructor Talk was variable over the course of the semester, with prevalence of Instructor Talk being highest in the first class session of the term for five of the eight instructors (Figure 3).

Emergence of a Parallel Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk Framework.

Review of the remaining Other instances from the eight instructors in novel course contexts suggested that this language was of a different and more negative nature that could be perceived as disrespectful, discouraging, or counterproductive to promoting student learning or building classroom culture. While not nearly as prevalent as instances coded as Positively Phrased Instructor Talk (n = 1791), language coded as Negatively Phrased Framework represented ∼10% (n = 230) of all Instructor Talk instances that were identified in these courses. Given the very different character of these instances, we decided that a second, parallel Instructor Talk framework was warranted, and we chose to refer to this second, parallel framework as a “Negatively Phrased” Instructor Talk framework to contrast with the original framework, which we now refer to as the “Positively Phrased” Instructor Talk framework. Table 4 shows the resulting parallel framework of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk alongside the originally published Positively Phrased Instructor Talk framework. Example instances of Negatively Phrased correlates for all five categories of Positively Phrased Talk were identified among Instructor Talk collected in the eight novel course contexts (see Table 5). Additionally, we hypothesized that this language could be further characterized using parallel Negatively Phrased subcategories for each existing subcategory of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk, and example instances were identified for 15 of the 18 hypothesized parallel Negatively Phrased subcategories (see Table 5). The three Positively Phrased Instructor Talk subcategories for which we did not find parallel Negatively Phrased examples were: Practicing Scientific Habits of Mind, Connecting Biology to the Real World and Career, and Fostering Wonder (see gray boxes in second column of Table 4).

TABLE 5.

Example instances of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk

| Subcategory | Example instance | |

|---|---|---|

| Dismantling the Instructor/Student Relationship | Ignoring Student Challenges | “I was hoping that we could work on these questions. We don’t have lab tonight so I’m going to hold you a little later. Is that okay? Anyone have to leave because they have work or something? If you absolutely have to leave, leave.”—Study 1: Whole Course |

| “Some people find that if you haven’t had a basic biology class before coming in here, it’s a little harder. You’ve got to learn some of those basic concepts a little faster than other folks.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Assuming Poor Behaviors from Students | “The reason I have one [make-up exam] is because people lie. A lot of them are flus. Or food poisoning. Food poisoning is the number one choice. Oh, food poisoning, you get over it so quickly … But, anyway, I allow one make-up, one. Otherwise, you get a zero.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “The other thing that I want to go back to, because I haven’t exactly shown it in a while and some of you are going to be like, I’m so sick of this, I’m so sick of this, it’s central dogma.”—Original study | ||

| Making Public Judgments about Students | “Is there someone named Glitter here? Yeah, ok. I have no idea who she is. She took the test. I don’t even know who she is. [Laughter] But I see a test from Glitter. I have no idea who she is. I don’t think she’s ever come to lecture. So anyway, if you see her in lab, please let me know. I have no idea who she is. So you know. I don’t even have a card for her. I see a test from Glitter, I thought it was a joke! Like, ‘My name is Glitter.’ So if you see her, tell her to come to lecture, that’s that. I don’t know who she is.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “And so, when you’re plotting something that’s 0.5 and you put it here, I don’t think you know what the hell you’re doing, okay? And so, a lot of people lost points last time because they were plotting things, you know, casually.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Disestablishing Classroom Culture | Expecting Students to Know What to Do | “Count 1 through 7, nice and loud. You guys, I don’t care how you do it, I just want it done.”—Study 1: Whole Course |

| “So, I stood here on Wednesday and told you point-blank there would be no questions about plants on your lab quiz. Were there any questions about plants on your lab quiz? There were seven questions about plants on your lab quiz. Not one person complained, okay? So, that makes you all very sweet, but seriously, you should have complained.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Discouraging Community among Students | “I guess on one end of the spectrum, it would be ignore it completely. The other end of the spectrum I guess would be to chop somebody’s hand off or head. We won’t do the last one, I guarantee. So, I’d like to know your opinion.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | |

| Criticizing Colleagues | “You know that you can ace the lab very easily, right? [Lab Instructor]’s nothing, ugh. Too easy.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “Wow, notice I’m saying the word with an -es at the end. This is actually something that is—it’s contentious. And a lot of people are confused about this, even journal editors. We recently published a paper, and the editor, which is probably a secretary with a bachelor’s degree or something—she kept on correcting us on the use of the plural. And so, it took several emails, and we’re like, no, actually, the word can be singular or plural referring to more than one. But, if there’s more than one species, it’s with an -es. And that is the correct use of the word.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Encouraging Only the Right Answer | “So look at your lecture participation exercises, look at pre and post lab exercises, online quizzes, things of that nature, because I know you’ve seen the right answer. So I can stack the deck in favor of you getting a good grade, and me grading less, if I give you something that I know that you know what the right answer is. Or at least you should know what the right answer is.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “If you do a good job, you could get a really pretty picture. You do a poor job, you’ll just get a really black looking structure that may not be easily able to help you see things.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Compromising Pedagogical Choices | Expressing Doubt in Pedagogical Choice | “I’m going to open this up to a class discussion. I don’t know if this seems fun or not, but I’m going to let you guys take turns coming up and saying things.”—Study 2: Sampling Method |

| Using Convenience to Drive Teaching Choices | “And so if you go to my website, I don’t use [class site], so for those of you who are familiar with that system, you’ve been [at CC] for a few quarters, I don’t use [class site], I use just my own website to post information. I can load it really easily at home. I put lots of links on there. So that just works best for me.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| Teaching to a Subset of Students | “And it’s not like oh, my God, I can’t do any of this. And I think for when I was walking around, there were a couple of things that people were struggling, but other people seemed like you were guys were doing fine.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | |

| Focusing on the Grade/Short Term | “So make sure you understand this. It’s going to be very very valuable for scoring high points there.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “That’s my job, and I take credit for your grade only 5% or less than that. Your grade, with that A, B, C—whatever it is—95% is yours—your contribution.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Sharing Self-Judgment | Sharing Self-Judgment/Self-Pity | “Sorry, I taught all day, so I’m, someone was sick, so I talked to them, so I’ve basically been teaching since 9:30. Straight. And I’m just kinda. My brain is like fried. So, forgive me for today.”—Study 1: Whole Course |

| “Yeah, sorry. If you guys don’t eat these, I will, and I’ll hate myself, so please come eat these.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Distancing from Student Experiences | “And I hated those people with photographic memory. They’re lucky, I’ll tell you. I don’t think they were smarter than me, but there were able to memorize a lot quicker than me and they were able to just know things better than me.”—Study 1: Whole Course | |

| “Small because men are weak.”—Study 2: Sampling Method | ||

| Masking Science | Being Implicit about the Nature of Science | “It’s all kind of a crazy process. If you think about the last two chapters, I just kind of accept it and move on. If I ever think, how do these hydrogen ions move? What is the end? I have no freaking idea, and I kind of just accept it and move on with my life.”—Study 1: Whole Course |

| Intimidating Students from Science | “So, we’ll see if this is our new class size, if I’ve managed to scare people away, or if this is just people being tardy.”—Study 2: Sampling Method |

Categories and Subcategories of the Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk Framework.

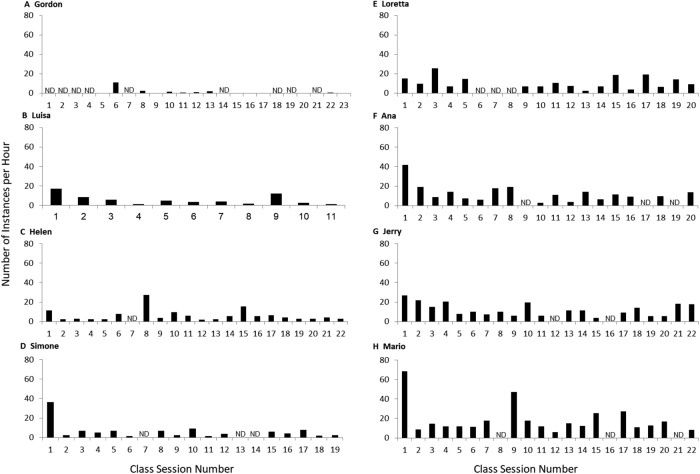

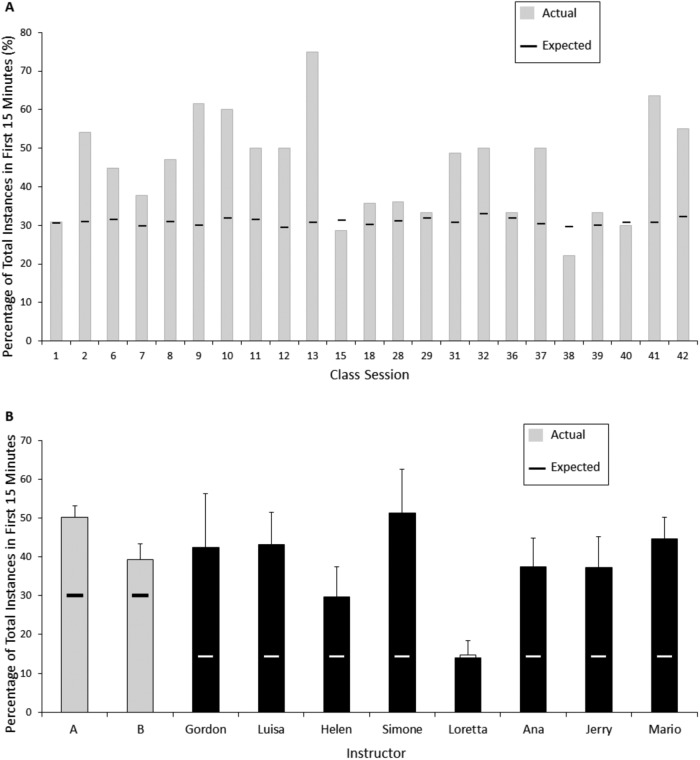

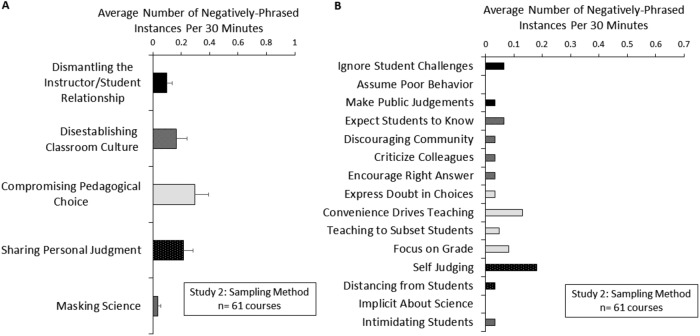

To introduce the categories of the Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk framework, we describe each below, in order of their prevalence as observed in the eight novel course contexts. Additionally, we articulate the subcategories for each category, and specific instances from each subcategory can be seen in Table 5. The average prevalence of each Negatively Phrased category and subcategory across the eight novel course contexts is shown in Figure 4, A and B.

FIGURE 4.

Prevalence of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk categories and subcategories in eight novel courses compared with the original instructor talk course. The average number of instances per hour for the whole-course analyses for eight novel courses and instructors for the categories (A) and subcategories (B) of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk. Re-examination of the original Instructor Talk course (Seidel et al., 2015) and detection of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk at the category level (C) and subcategory (D) levels are also shown. Patterns and colors of bars represent associations between subcategories and their parent categories: Dismantling the Instructor/Student Relationship (black bars), Disestablishing Classroom Culture (hatched bars), Compromising Pedagogical Choices (light gray bars), Sharing Personal Judgments (black bars with dots), and Masking Science (dark gray bars). Error bars represent SEM.

Dismantling the Instructor/Student Relationship.

Similar to its parallel category in the Positively Phrased Instructor Talk framework, Dismantling the Instructor/Student Relationship was the most prevalent category (n = 98 instances) of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk observed in the eight novel course contexts (see Figure 4, A and B, as well as Table 5), representing 42.6% of the Negatively Phrased instances identified. The most prevalent subcategory was Making Public Judgments of Students, which included instances in which the instructor used judgmental language about one or more students in front of the entire class. The second most prevalent subcategory was Assuming Poor Behavior from Students, which included language that alluded to instructor assumptions that students were unmotivated to learn or did not want to succeed. The final subcategory was Ignoring Student Challenges, which included instructor language that minimized or dismissed difficulties that students may face in succeeding in the course.

Compromising Pedagogical Choice.

The second most prevalent category of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk observed in the eight novel course contexts was Compromising Pedagogical Choices (see Figure 4, A and B, as well as Table 5), representing 24.3% of the Negatively Phrased instances identified (n = 56). Within this category, the most prevalent subcategory observed was Using Convenience to Drive Teaching Choices, in which instructors discussed having students do things in ways advantageous to the instructor, even if it made the class more difficult for students. This second most prevalent subcategory was Focusing on the Grade/Short Term, which included instructor language that focused students on grades more so than learning.

While not present in the eight novel course contexts, two other subcategories of Compromising Pedagogical Choice were discovered while analyzing the larger 61-course data set collected in service of developing a sampling strategy in study 2 (see below). One of these was the subcategory of Teaching to a Subset of Students, in which the instructor appeared to express the intention to focus on a certain group of students and not others in the classroom. Another subcategory discovered in developing a sampling strategy in study 2 was Expressing Doubt in Pedagogical Choices, in which instructors questioned whether new teaching methods that they were attempting would be effective in their courses.

Sharing Personal Judgment.

The third most prevalent category of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk in the eight novel course contexts was Sharing Personal Judgment (see Figure 4, A and B, as well as Table 5), representing 21.7% of the Negatively Phrased instances identified (n = 50). The most prevalent subcategory was Sharing Self-Judgment/Self-Pity, which included instances when instructors disparaged themselves in front of students. The only other subcategory was Distancing from Student Experiences, which consisted of instances when instructors asserted differences between their experiences and those of students.

Disestablishing Classroom Culture.

The fourth most prevalent category of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk across the eight novel course contexts was Disestablishing Classroom Culture (see Figure 4, A and B, as well as Table 5), representing 10% of the Negatively Phrased instances identified (n = 23). The most prevalent subcategory was Criticizing Colleagues, in which instructors would disparage colleagues in class. The second most prevalent subcategory was Encouraging Only the Right Answer, which included language that conveyed that an instructor valued only correct answers in the classroom. The third most prevalent subcategory was Expecting Students to Know What to Do, when instructors appeared to be impatient with students’ lack of understanding of classroom norms. And the final subcategory was Discouraging Community among Students, which included instructor language that appeared to discourage students from working together.

Instances of Discouraging Community among Students were only found in analyzing the 61-course data set that was collected in service of developing a sampling strategy in study 2 (see below).

Masking Science.

Finally, just like its parallel Positively Phrased category, Masking Science was the least prevalent category of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk observed in the eight novel course contexts (see Figure 4, A and B, as well as Table 5), representing 1.3% of the Negatively Phrased instances identified (n = 3). The most prevalent subcategory was Being Implicit about the Nature of Science, which included language that discouraged students from being curious about underlying scientific ideas and encouraged them to just accept information. The other subcategory was Intimidating Students from Science, which included language that suggested that students leave science if they were unable to keep up with the material. Instances of Intimidating Students from Science were only found in analyzing the 61-course data set that was collected in service of developing a sampling strategy in study 2 (see below).

Comparison of Whole-Course Analysis and Original Study for Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk.

Since our original investigation and description of Instructor Talk (Seidel et al., 2015) did not detect Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk, we reanalyzed that data set to investigate whether there was such language present, and if so, how much and what categories could be observed. Indeed, we did detect instances of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk present the original study upon re-examination (see Figure 4). However, the relative frequencies of different categories of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk were different in the whole-course analysis data set compared with the original Seidel et al. (2015) data set (Figure 4, A and C). While Dismantling the Instructor/Student Relationship was the most prevalent category in both data sets, Seidel et al. (2015) did not contain any Disestablishing Classroom Culture or Masking Science. In addition, examination at the subcategory level revealed that there were several subcategories of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk present in the whole-course analysis data set that were not found in the Seidel et al. (2015) data set, including: Expecting Students to Know What to Do, Criticizing Colleagues, Encouraging Only the Right Answer, Using Convenience to Drive Teaching Choices, Distancing from Students, and Being Implicit about the Nature of Science (Figure 4, B and D).

Comparison of the overall amounts of Positively Phrased versus Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk used in each course is shown in Figure 5. For each course studied, Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk was a smaller percentage of overall Instructor Talk than Positively Phrased Instructor Talk. When comparing amounts of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk used across instructors, Mario was found to have used significantly more Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk than other instructors using pairwise comparison (one-way ANOVA Fs = 8.389, p = 4.37E-10; and Tukey-Kramer test).

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of rates of Positively Phrased and Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk by individual instructor. Rates of Instructor Talk (average number of instances per hour) are shown for each of the instructors of the eight courses in the whole-course analysis for Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk (white bars) and Positively Phrased Instructor Talk (black bars). Additionally, data are shown for the two instructors from the original Instructor Talk study (Seidel et al., 2015) for both Negatively Phrased (white bars) and Positively Phrased Instructor Talk (gray bars). Error bars represent SEM.

Study 2: Developing a Sampling Method for Analysis of Instructor Talk

Establishing a Sampling Method for Analyzing Instructor Talk in Large Data Sets.

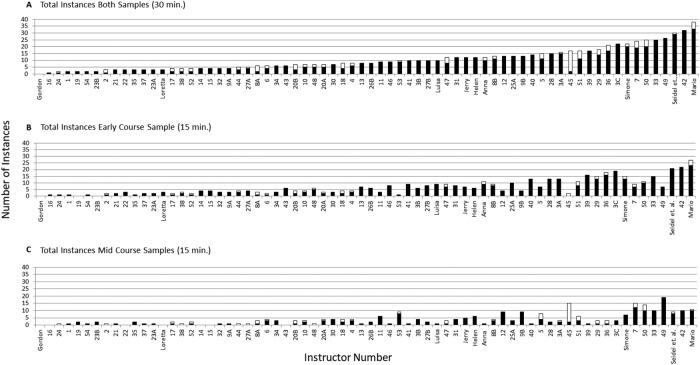

To enable investigation of Instructor Talk in a large number of courses, we developed a sampling method in which the quantity of Instructor Talk instances would be representative or enriched in the samples examined. To validate the sampling method, we examined the proportion of Instructor Talk instances identified in the first 15 minutes of every class period in the original Seidel et al. (2015) study to test whether this would yield a representative sample of the amount of Instructor Talk present across the class entire period (see Figure 6). We found that the proportion of Instructor Talk instances present in the first 15 minutes of class either represented or overrepresented the amount of Instructor Talk present for that whole class session in 20 of the 23 class sessions examined (Figure 6A). In examining how this sampling method related to overall amounts of Instructor Talk for each of the two instructors in the original Seidel et al. (2015) study, as well as for the eight instructors in study 1 presented here, we found that sampling the first 15 minutes of each class session either represented or overrepresented the overall quantity of Instructor Talk for the course for all instructors (Figure 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Developing a strategy to sample Instructor Talk by evaluating representation of Instructor Talk in the first 15 minutes of class sessions. (A) The percentage of Instructor Talk instances that would be expected in the first 15 minutes of each 50-minute class session (black lines; assuming uniform distribution of Instructor Talk) is compared with the actual percentage present in the 15-minute sample from the beginning of each class session (light gray bars) for the 23 class sessions in the original Instructor Talk study (Seidel et al., 2015). While the course met for 50-minute class sessions, the expected Instructor Talk was calculated based on the specific minutes of recording for each particular class session. (B) Similarly, the average percentage of Instructor Talk instances that would be expected in the first 15 minutes of courses with either 50- or 90-minute class sessions (black or white lines; assuming uniform distribution of Instructor Talk) is compared with the actual average percentage present in the 15-minute samples from the beginning of each class session for Instructors A and B from the original Instructor Talk study (light gray bars; Seidel et al., 2015) and for the instructors of the eight courses in the whole-course analysis (black bars).

Positively Phrased Instructor Talk appeared to be represented or overrepresented using the sampling method for all but one instructor (9/10). At the category level of Instructor Talk, we observed that the sampling method did either represent or overrepresent the amount of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk for all categories for the majority of instructors: Building the Instructor/Student Relationship (for 10 of 10 instructors), Establishing Classroom Culture (for 7 of 10 instructors), Explaining Pedagogical Choices (for 9 of 10 instructors), Sharing Personal Experiences (for 9 of 10 instructors), and Unmasking Science (for 7 of 10 instructors; see Appendix Table B in the Supplemental Material). At the subcategory level, the sampling method varied between over- and underrepresenting the amount of these specific subtypes of Instructor Talk among the 10 instructors examined, based on their individual frequency of use of different subcategories of Instructor Talk. Similarly, Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk appeared to be represented or overrepresented using the sampling method for all instructors (10/10). At the category level of Instructor Talk, we observed that the sampling method did either represent or overrepresent the amount of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk for all categories for the majority of instructors: Dismantling the Instructor/Student Relationship (for 9 of 10 instructors), Disestablishing Classroom Culture (for 10 of 10 instructors), Compromising Pedagogical Choices (for 10 of 10 instructors), Sharing Personal Judgment (for eight of 10 instructors), and Unmasking Science (for 10 of 10 instructors; see Appendix Table C in the Supplemental Material). It is important to note that, for many instructors, there were no instances of Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk overall for several categories. For additional details on the accuracy of this initial sampling strategy, please see the Supplemental Material.

Applying the Developed Sampling Strategy to Investigate Instructor Talk among Large Numbers of Instructors and Courses.

To investigate the presence, prevalence, and nature of Instructor Talk among 53 instructors teaching 61 courses, we analyzed transcripts of two, 15-minute samples of course language (Figure 7). As a reminder, the first transcript was of the first 15 minutes of the first class session recorded at the beginning of the term (early-course sample), and the second transcript was of the first 15 minutes of a class session recorded midterm, approximately 8 weeks later for semester-system instructors and approximately 5 weeks later for quarter-system instructors (midcourse sample). Instructors were labeled with a random number, and those instructors having multiple courses were identified by different letters following their numbers. Example quotes can be found in Tables 2 and 5.

FIGURE 7.

Profile of Instructor Talk present in two, 15-minute samples across 61 courses. (A) The total number of Instructor Talk instances across two, 15-minute samples (both early-course and midcourse samples combined) for 53 instructors in the sampled data set (numbers), eight instructors from the whole-course data set (pseudonyms), and the original Instructor Talk study (Seidel et al., 2015). Each bar represents the number of instances per individual instructor of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk (black) and Negatively Phrased Instructor Talk (gray). Instructors are ordered by total number of Instructor Talk instances observed in the combined samples. Instructors with multiple courses in this analysis were given a letter designation after their numbers to identify different courses. (B) Number of Instructor Talk instances found for each instructor only in the early-course sample, which was the first 15 minutes of the first class session recorded. (C) Number of Instructor Talk instances found for each instructor only in the midcourse sample, which was the first 15 minutes of a midterm class session ∼8 weeks later.

The rates of Instructor Talk found among the 53 instructors and 61 courses varied widely in the amount of Instructor Talk used overall (Figure 7A; n = 565 instances total), in the early-course samples (Figure 7B; n = 372 instances total), and in the midcourse samples (Figure 7C; n = 193 instances total), arranged by instructor from least to most overall Instructor Talk detected. The eight instructors from the whole-course analysis data set and the Seidel et al. (2015) data set were included for comparison. The amount of Instructor Talk detected using this sampling method ranged from 0 (Gordon) to 38 instances (Mario), cumulatively, in the 30 minutes sampled. All instructors examined exhibited at least one instance of Instructor Talk in their samples. There was statistically more Instructor Talk detected on average in the early-course samples compared with the midcourse samples (6.7 vs. 3.8 instances, p < 0.0001, t test).

Category and Subcategory Analyses of Instructor Talk in the Sampled Courses.

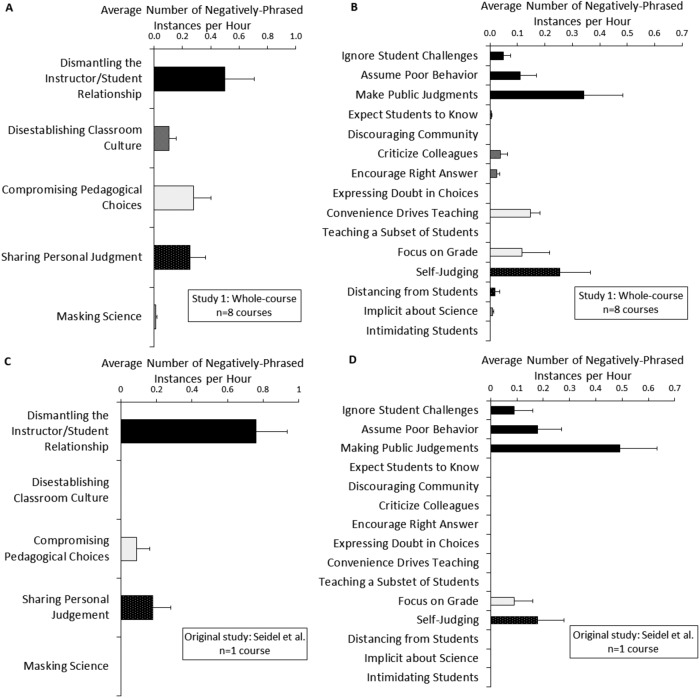

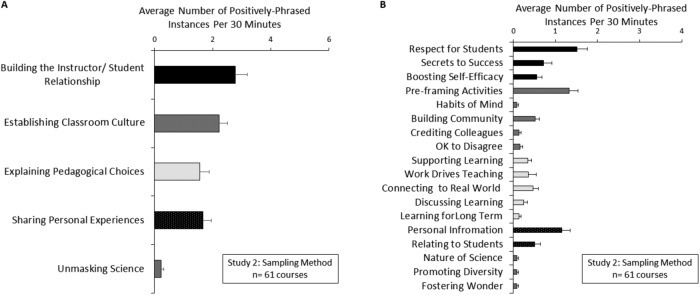

The relative prevalence of different categories of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk found in the 61 sampled courses was similar to that found in the whole-course analysis data set from study 1 (Figure 8 compared with Figure 1). The most prevalent category found overall was Building the Instructor/Student Relationship (32.9%, n = 170 instances; see Figure 8A compared with Figure 1A), followed by Establishing Class Culture (26.3%, n = 136 instances), Sharing Personal Experiences (19.5%, n = 101 instances), Explaining Pedagogical Choices (18.4%, n = 95 instances), and Unmasking Science (2.7%, n = 14 instances). Analysis at the subcategory level revealed that all subcategories of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk were present in the sampled courses data set (Figure 8B compared with Figure 1B).

FIGURE 8.

Prevalence of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk categories and subcategories in samples from 53 instructors in 61 courses. The average number of instances of the categories (A) and subcategories (B) of Positively Phrased Instructor Talk for the 30-minute samples from the 53 instructors of 61 courses in the sampled data set. Patterns and colors of bars represent associations between subcategories and their parent categories: Building the Instructor/Student Relationship (black bars), Establishing Classroom Culture (hatched bars), Explaining Pedagogical Choices (light gray bars), Sharing Personal Experiences (black bars with dots), and Unmasking Science (gray bars). Error bars represent SEM.