Abstract

Covalent macrocycles and three-dimensional cages were prepared by the self-assembly of di- or tritopic anilines and 2,6-diformylpyridine subcomponents around palladium(II) templates. The resulting 2,6-bis(imino)pyridyl-PdII motif contains a tridentate ligand, leaving a free coordination site on the PdII centers, which points inward. The binding of ligands to the free coordination sites in these assemblies was found to alter the product stability, and multitopic ligands could be used to control product size. Multitopic ligands also bridged metallomacrocycles to form higher-order supramolecular assemblies, which were characterized via NMR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and X-ray crystallography. An efficient method was developed to reduce the imine bonds to secondary amines, leading to fully organic covalent macrocycles and cages that were inaccessible through other means.

Introduction

Covalent organic macrocycles1 and cages2 have found wide application. These structures serve as hosts for guest recognition,3 in molecular separations,4 as catalysts,5 for surface modification6 and to enable the generation of new mechanically interlocked molecular architectures.7 The preparation of these species is not trivial, however, as many covalent bonds need to be formed in the correct geometry to enable macrocycles and cage structures to come together. Where bonds are not formed reversibly, the formation of off-pathway kinetic products can limit the yield of a desired species, rendering product isolation challenging. Higher yields and cleaner products may be obtained through the use of templates8 and reversibly formed linkages9 such as imines,10 boronic esters,11 and alkenes12 or alkynes13 (with appropriate catalysts). The use of such dynamic covalent bonds leads to the formation of thermodynamic products, but such products may show limited stability due to cleavage of the dynamic bonds, such as hydrolysis of imines.

Functional macrocycles and cages can also be prepared using metal–organic self-assembly.14 Palladium(II) is among the most frequently employed metals for metal–organic assemblies.15 PdII-based assemblies often incorporate two or four pyridine-based ligands coordinated to each palladium center. These assemblies benefit from the strong propensity of palladium(II) to adopt a square planar coordination geometry,16 allowing the 90° angles between ligands to translate into structural elements within larger assemblies, from two-dimensional macrocycles to three-dimensional cages.15a The use of PdII in subcomponent self-assembly, where intricate metal complexes are brought together at the same time as the multitopic ligands that compose them are templated, has provided access to small macrocycles, (pseudo)rotaxanes, and a catenane.17 Here we report the use of this technique to generate a new class of macrocycles, as well as cages and larger assemblies. These macrocycles and cages were demetalated and reduced, yielding large, complex organic structures whose preparation would be otherwise difficult to envisage.

Results and Discussion

Properties of the Bis(imino)pyridyl-PdII Building Block

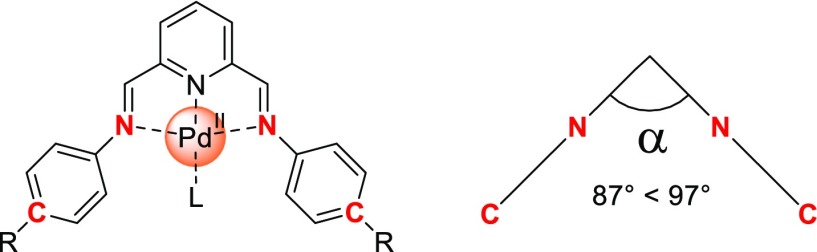

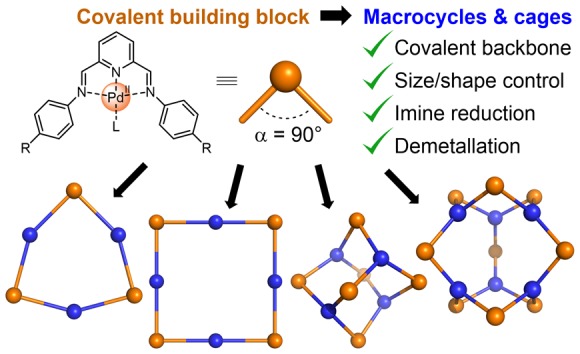

In order to elucidate the design principles for this class of Pd-templated architectures, we carried out a careful analysis of the crystal structures of complexes bearing a 2,6-bis(imino)pyridyl-PdII moiety.17 The angle between the aniline residues ranged from 87° to 97° [see Figures 1 and S83 (Supporting Information, SI)].18 This motif may thus be used to engender an angle close to 90° but displaying some flexibility. Moreover, the tridentate ligand leaves one free coordination site on PdII that can bind a chosen monodentate ligand. Nabeshima et al. recently used such free coordination sites within PdII complexes to control their conformation.19 Notably, the condensation of anilines and 2,6-diformylpyridine 1 with no metal template would result in an angle between aniline residues close to 120° and prone to torsion about the NCH–pyridyl bonds. These additional degrees of freedom could lead to the formation of mixtures of structures, as opposed to the single products observed in our study.

Figure 1.

The 2,6-bis(imino)pyridyl-PdII motif provides a 90° bend within higher-order structures.

Covalent Macrocycles

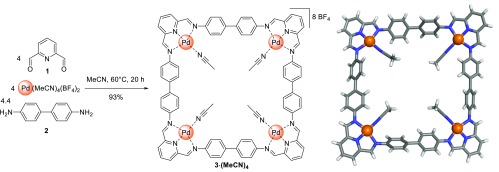

The reaction of 2,6-diformylpyridine 1, benzidine 2, and [Pd(MeCN)4](BF4)2 in a 1:1.1:1 ratio in acetonitrile afforded clean formation of PdII4[4 + 4] square complex 3·(MeCN)4 (Scheme 1). If a slight excess of 2 was not employed, traces of a secondary species were observed by 1H NMR spectroscopy. We infer that the excess 2 led to the disappearance of the secondary species, possibly as a consequence of dynamic imine exchange being catalyzed by the additional aniline present.

Scheme 1. Synthesis and Crystal Structure of Pd4[4 + 4] complex 3·(MeCN)4.

Anions and free solvent molecules are not shown for clarity.

Crystals of 3 were grown by slow diffusion of diisopropyl ether (iPr2O) into an MeCN solution in the presence of KAsF6 (20 equiv/Pd). Single-crystal X-ray diffraction revealed the structure of complex 3 (Scheme 1). Solid 3 adopts a conformation having angles between the phenylene rings at each corner of α = 89° and 95°.

Square complex 3 evokes the [(ethylenediamine)PdII]4(4,4′-bipyridine)4 structure originally reported by Fujita and co-workers20 and related square coordination macrocycles, including various linear divalent ligands later reported by Stang and co-workers.21 Differences between this key Fujita precedent and 3, and by extension the other structures reported herein, include (i) a longer distance between adjacent PdII centers in 3 (12.3 Å) than in the Fujita square (11.1 Å), (ii) a fully covalent skeleton in 3, (iii) trans coordination of imines around PdII in 3·(MeCN)4 vs cis coordination of pyridines in the Fujita structure, and (iv) a free coordination site for additional ligands pointing inside the macrocycle for 3, as opposed to two outward-facing coordination sites, necessarily occupied by bidentate ligands, in the relevant Fujita precedents.

The successful ESI-MS analysis of square 3 required the replacement of its acetonitrile ligands with 2,6-bis(trimethylsilylalkynyl)pyridines (Figures S6 and S7, SI). We infer that these stronger and more hindered monodentate ligands stabilized the PdII4 skeleton of 3, disfavoring monodentate ligand loss and the rearrangement reactions that follow under ESI-MS analysis conditions.

The more flexible 4,4′-oxydianiline 4 had been reported to self-assemble with 1 and [Pd(MeCN)4](BF4)2 to form the Pd3[3 + 3] macrocycle 5·(MeCN)3, which was isolated by size-exclusion chromatography (Scheme 2).17 The addition of the nBu4N+ salts of Cl–, Br–, I–, or SCN– resulted in the displacement of the acetonitrile ligands of 5 by these anions (Figure S69, SI). In contrast, the addition of fluoride led to degradation. The products 5·Cl3 and 5·Br3 were stable in solution and under ESI-MS conditions (Figures S70 and S71), whereas 5·I3 and 5·(SCN)3 degraded in acetonitrile over 2 days at room temperature.

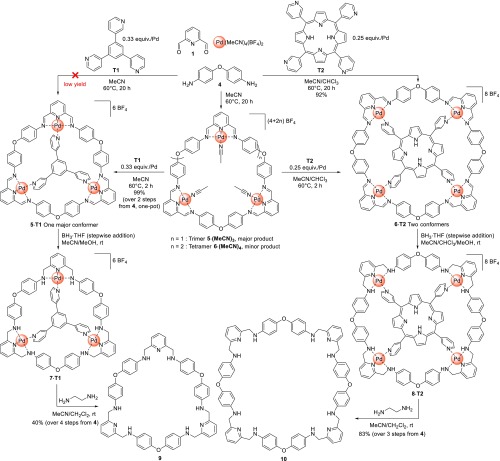

Scheme 2. Selective Templated Assembly, Reduction, and Demetallation of Macrocycles 5 and 6.

As-synthesized 5·(MeCN)3 showed a minor set of peaks in the 1H NMR spectrum (Figure S69, SI). We inferred these peaks to correspond to the PdII4[4 + 4] macrocycle 6·(MeCN)4 (Scheme 2). In order to obtain these macrocycles directly in a pure state, we employed the inward-facing coordination sites on the palladium centers to selectively form either the [3 + 3] or [4 + 4] macrocycles by using appropriate central templates. PM6-optimized models22,23 indicated that tris-pyridyl and tetrakis-pyridyl templates T1 and T2 would be a good size match for the macrocycles (Tables S2–S7, SI).

The addition of tris(pyridyl) template T1 (0.33 equiv/Pd) to the initially formed ca. 4:1 mixture of 5·(MeCN)3 and 6·(MeCN)4 afforded trimeric 5·T1 as the major species, in near-completion by NMR within 5 min at 25 °C. Further heating of the mixture to 60 °C resulted in the disappearance of all traces of tetrameric 6 in the NMR spectrum. In contrast, the addition of tetrakis(pyridyl) template T2 to the initial mixture of 5·(MeCN)3 and 6·(MeCN)4 required heating prior to the formation of 6·T2, which ended up as the exclusively observed product after 2 h at 60 °C. This difference in initial reaction speed can be explained by the fast replacement of acetonitrile by T1 inside 5·(MeCN)3, followed by the conversion of the minor tetrameric macrocycle 6 to 5 upon heating while addition of T2 requires the slow conversion of the major trimeric macrocycle 5 to tetrameric 6·T2.

Surprisingly, mixing and heating 1, 4, and PdII with T1 in the proportions required to generate 5·T1 led to a complex mixture containing only ca. 20% of the templated macrocycle. This outcome illustrated the importance of the order of addition for the subcomponents in this case. In contrast, the addition of template T2 either before or after the formation of macrocycles 5·(MeCN)3 and 6·(MeCN)4 resulted in the exclusive formation of 6·T2 after heating.

Control experiments elucidated the different behavior of the two templates toward PdII. When T1 or T2 was mixed with [Pd(MeCN)4](BF4)2 (0.75 or 1.0 equiv, respectively) in acetonitrile at 60 °C, no discrete species were observed by 1H NMR. Whereas T2 afforded a strongly colored solution, T1 gave a precipitate and colorless solution, suggesting the removal of soluble PdII species, which are usually colored. We thus infer that the one-step formation of 5·T1 is prevented by the initial precipitation of a PdII–T1 adduct. We note that T2 has already been reported to form heteroleptic complexes with PdII24 but that 5·T1 is the first report of a PdII complex involving T1 as a ligand.

The 1H NMR spectra of 5·T1 and 6·T2 showed several sets of signals [Figures S9 (SI) and 2], which were attributed to different conformers having distinct orientations of the pyridyl moieties of the templates (i.e., either above or below the plane of the PdII centers). DOSY analyses revealed the different sets of signals to correspond to species of similar sizes (Figures S14 and S22, SI). The 1H NMR spectrum of the major species observed for 5·T1 is consistent with Cs symmetry, which is expected from the conformer presenting one inverted pyridyl moiety, i.e., a partial cone;25 only traces of other conformers are observed.

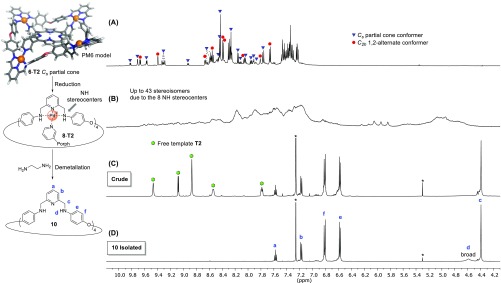

Figure 2.

Top left: PM6 model of 6·T2 partial cone. Right: 1H NMR spectra (500 MHz, 25 °C) of (A) 6·T2 in CD3CN, (B) 8·T2 in CD3CN (vertical scaling ×5), (C) 10 in CDCl3 (crude material after demetalation), and (D) isolated 10 in CDCl3. *Residual solvent peaks.

Two conformers were observed for 6·T2 [Figures 2 and S16 (SI)]: a Cs-symmetric (partial cone25) conformer with a single inverted pyridyl unit and a C2h symmetric (1,2-alternate25) conformer with two adjacent pyridyl units inverted. The conformers of 6·T2 were observed in a Cs/C2h ratio of ca. 3:2 in CD3CN at 25 °C. EXSY NMR experiments did not show exchange between the conformers, and variable-temperature (VT) 1H spectra showed only slight broadening of the peaks at 75 °C (Figure S23, SI), which indicates that conformational exchange occurs slowly on the NMR chemical shift time scale. We infer the slow conformer exchange to be a consequence of the necessity of breaking a coordinative bond between the template pyridyl and PdII.

PM6 models22,23 of the four possible conformers suggested that the remaining cone and 1,3-alternate conformers25 would lead to high-energy distortion, clarifying why they were not observed (Tables S4–S7, SI). The presence of the pyridyl-based templates increased the stability of complexes 5·T1 and 6·T2 under ESI-MS conditions compared to their acetonitrile-bound counterparts, thus allowing their characterization by mass spectrometry (Figures S15 and S24, SI).

Reduction and Demetalation of PdII-Templated Macrocycles

Large, covalent macrocycles are challenging to produce in high yields, often requiring high-dilution conditions.26 We thus explored the reduction and demetalation of 5·T1 and 6·T2 to produce organic macrocycles of 48 or 64 atoms in circumference.

Reducing conditions were screened for non-templated macrocycles 5·(MeCN)3 and 6·(MeCN)4 and showed that the reducing agent BH3·THF in acetonitrile at room temperature gave higher yields of the secondary-amine products than did NaBH4, LiAlH4, or NaH. Three changes to our initial experimental procedure were found to further optimize the yield of the reduced macrocycles. First, the BH3·THF was added in equal portions stepwise (0.25 equiv/imine) every 10 min, instead of all at once. Second, reduction was carried out in the presence of methanol as a cosolvent (MeCN/MeOH, 5:1, v/v) to quench excess BH3 after each addition, to avoid side reactions. Third, a stronger-field monodentate ligand than acetonitrile, such as a pyridine or chloride, served to protect the PdII center from reduction. Employing these optimized conditions were found to minimize the side reactions that produced undesired reduced products, such as palladium black and ring-opened macrocycles.

These optimized conditions on the mixture of 5·Cl3 and 6·Cl4 afforded a mixture of purely organic covalent macrocycles 9 and 10, which proved inseparable by chromatography. However, applying these conditions to 5·T1 and 6·T2 followed by demetalation afforded isolated macrocycles 9 and 10, respectively.

Reduced macrocycles 7·T1 and 8·T2 (Scheme 2) could withstand higher cone voltage and temperatures under ESI-MS conditions than the parent imine-based macrocycles 5·T1 and 6·T2. We infer that this greater stability in the absence of imine functionality results from the impossibility of hydrolysis of the reduced macrocycles under ESI-MS conditions. We note that the ESI-MS spectra of 7·T1 and 8·T2 were consistent with a +2 oxidation state for all Pd centers, despite the reducing conditions, as was observed for all metal–organic complexes reported herein (see the SI). Compounds 7·T1 and 8·T2 displayed complex 1H NMR spectra, which we infer to be a result of the large number of stereoisomers originating from the new NH stereocenters coordinated to the PdII cations (see Figures S25, S26, 2B, and S30). Thus, we could not assess product purity at this stage and proceeded with the demetalation of 7·T1 and 8·T2 after their precipitation by addition of Et2O to MeCN solutions.

The demetalated trimeric (9) and tetrameric (10) macrocycles were obtained by treating 7·T1 and 8·T2, respectively, with ethylenediamine (2 equiv/Pd) as a competing ligand (Scheme 2). 1H NMR analysis of the crude products showed the desired species 9 or 10 with the corresponding free templates T1 or T2 and traces of side products (Figures S38 and 2C). Separation of the final products from the templates and side products was achieved by preparative-layer chromatography to isolate either 9 (40% yield) or 10 (83% yield). The isolated yield of 10 corresponds to a yield of at least 98% per imine reduction from 6·T2 to 8·T2 if the other steps proceeded quantitatively. The isolated yield of 9 is lower despite the ca. 68% yield by 1H NMR analysis of the crude product (Figure S38, SI) because lengthy purification was necessary to remove traces of impurities with similar polarity and solubility to the desired product 9. The purification process allowed for the clean recovery of the free templates T1 and T2 for future use. When the one-pot syntheses of 9 or 10 starting from 4 were attempted, the final separation proved extremely challenging, lowering the isolated yields. Thus, the precipitation of 7·T1 and 8·T2 after reduction was a crucial step to remove side products. The final covalent organic macrocycles 9 and 10 were stable over weeks when stored in the solid state but slowly degraded in chlorinated solvents. Despite the fast and efficient reduction of imine bonds reported herein with only limited equivalents of borane (2.0–2.5 equiv of BH3/imine), only rare examples of imine reduction with this inexpensive and easy-to-handle reducing agent have been reported.27

Higher-Order Supramolecular Assembly of Macrocycles

When 1, 4, and PdII reacted in the presence of naphthalene diimide (NDI)-based template T3, a triply bridged dimer of trimeric macrocycles 52·T33 was observed to form (Scheme 3). When less T3 was employed, free 5·(CD3CN)3 and 52·T33 were observed as the principal products (see 1H NMR spectra in Figure S53, SI). This observation suggests the presence of positive cooperativity in the binding of T3 by 5.28 Crystals of 52·T33 were grown by slow diffusion of benzene into an MeCN solution in the presence of KSbF6 (10 equiv/Pd). The single-crystal X-ray structure (Scheme 3) shows that the macrocycles adopt a cone conformation, similar to the crystal structure of 5·(MeCN)3,17 with the concave face pointing outward. The three bridging T3 ligands twist around the central C3 axis, lending helicity to the complex in the solid state. Both right-handed and left-handed helices were present in the crystal, related by inversion symmetry. The three NDI units enclose a tubular 98 Å3 cavity that contains a BF4– anion despite crystallization in the presence of excess SbF6–.29 The angles between phenylene rings around PdII centers are in the range α = 85°–91°, which shows that the bis(imino)pyridyl-PdII moiety again adopts an angle close to 90°. The 1H NMR spectrum of 52·T33 in CD3CN at 25 °C corresponds to a D3h structure, which does not reflect the helicity observed in the solid state. VT NMR (Figure S51, SI) showed desymmetrization at −40 °C, with a 1H NMR spectrum corresponding to the D3-symmetric species observed in the solid state. Conversion between enantiomers thus occurred in solution with an activation barrier ΔG⧧ = 52 ± 2 kJ mol–1 at 0 °C (Figure S51, SI). VT 19F NMR showed that the inclusion and release of BF4– is rapid on the chemical shift time scale at 25 °C but slow at −40 °C, as indicated by the appearance of a peak for the included BF4– at low temperature (Figure S52, SI).

Scheme 3. Synthesis and Crystal Structure of the Bridged [3 + 3] Macrocycles 52·T33.

Anions and free solvent molecules are not shown for clarity; only the right-handed helix is shown, but both enantiomers are present in the crystal. The cavity of 98 Å3 is shown in green.

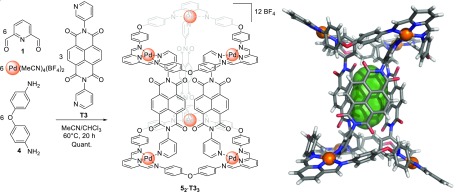

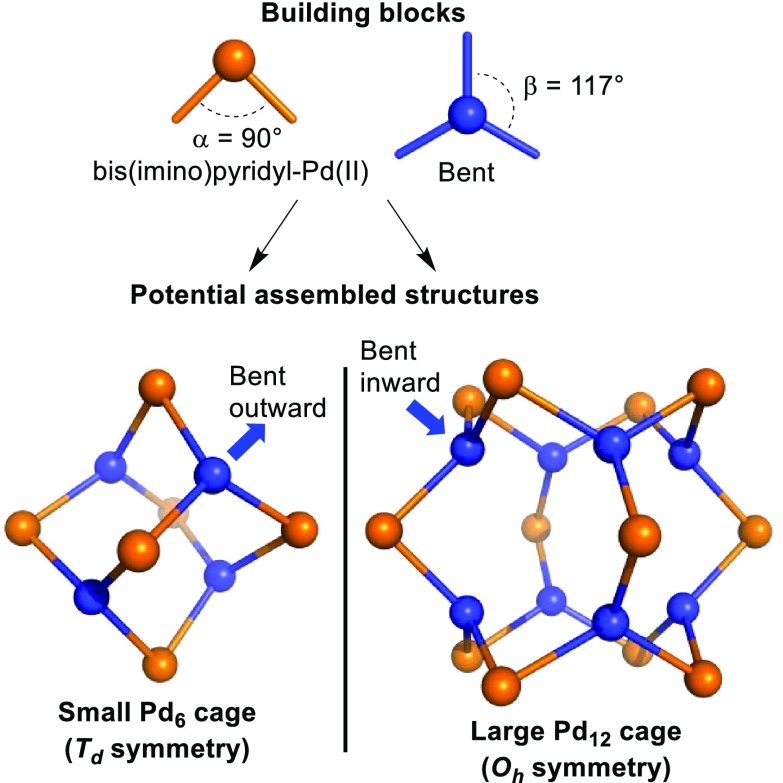

Three-Dimensional Covalent Cages

Considering the bis(imino)pyridyl-PdII motif as a 90° 2-fold connector, a corresponding 3-fold connector with ∼117° angles30 could generate two distinct three-dimensional high-symmetry cages: a Pd6 structure with Td symmetry and a larger Pd12 architecture with Oh symmetry (Figure 3).31

Figure 3.

Expected structures for the assembly of 90° bis(imino)pyridyl-PdII moiety with corresponding tris-anilines of appropriate geometry. The small Pd6 cage approximates a truncated tetrahedron, and the large Pd12 cage is cuboctahedral.

Considering that the ideal angle30 of 117° is close to the 120° of planar tris-anilines, we tested four planar tris-anilines and a pyramidal one [Figures 4 and S73 (SI)]. The more rigid tris-anilines gave only traces of discrete species along with oligomeric products, as suggested by the presence of small sharp 1H NMR signals along with more intense broad signals (Figure S73, SI). This result is not surprising, as a fully planar tris-aniline, with an angle β of 120°, would require an angle α of either 71° or 109° to form the small or large cage structures proposed in Figure 3, respectively.30 Such α values are outside of the range of angles adopted by the bis(imino)pyridyl-PdII building block studied herein.

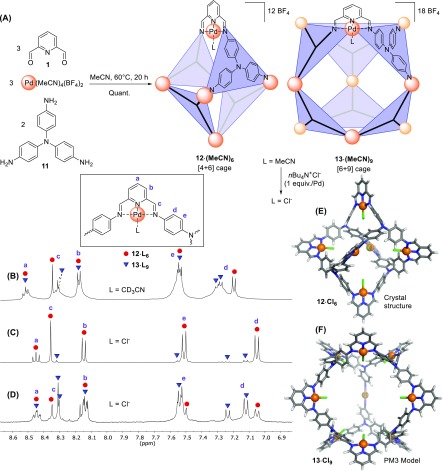

Figure 4.

(A) Synthesis of 12 ([4 + 6] cage) and 13 ([6 + 9] cage). 1H NMR spectra (CD3CN, 25 °C) of (B) 12·(MeCN)6 and 13·(MeCN)9 (anion = BF4–, 500 MHz), (C) enriched 12·Cl6 from the first extraction (anion = NTf2–, 400 MHz), and (D) enriched 13·Cl9 from the fifth extraction (anion = NTf2–, 400 MHz). (E) Crystal structure of 12·Cl6: anions and free solvent molecules are not shown for clarity; right-handed propellers are arbitrarily shown. (F) PM3 model of 13·Cl9: right-handed propellers were chosen arbitrarily for the optimization.

The product mixture formed from the more flexible tris(4-aminophenyl)amine 11 had two sets of sharp peaks in the 1H NMR spectrum, suggesting that the nitrogen atom in the ligand core can rehybridize in order to adopt the geometry required to form stable cages (Figure 4). DOSY analysis indicated that the two sets of peaks correspond to structures having different sizes (Figure S61, SI). As with their smaller congeners, the products having MeCN bound to the internally facing PdII coordination site were unstable under ESI-MS conditions. Replacement of MeCN with chloride increased the stability, which allowed successful analysis by ESI-MS (Figure S62, SI).

We initially expected these products to correspond to the Pd6 and Pd12 cages shown in Figure 3. The 1H NMR and ESI-MS analyses indicated that the major species corresponded to the expected highly symmetrical (Td) Pd6 cage 12, but the minor species corresponded instead to an intermediate Pd9 cage 13 with D3h symmetry (Figure 4), having two sets of 1H NMR peaks in a 2:1 ratio.

Crystals of 12·Cl6 were grown from the mixture of 12·Cl6 and 13·Cl9 by slow diffusion of benzene into an MeCN solution in the presence of KAsF6 (10 equiv/Pd) (Figure 4). The single-crystal X-ray data were of lower quality than for the other complexes reported herein, which we attributed partly to disorder around the phenylene rings. The three phenylene rings around each central nitrogen adopt a propeller shape with disorder observed between the right-handed and left-handed propellers. This propeller geometry has been observed for other self-assembled cages incorporating tris-aniline 11.32 The X-ray data did not allow us to differentiate whether the crystal of 12·Cl6 contained pure enantiomers (i.e., entirely right-handed and left-handed cages) randomly scattered or if each cage within the crystal contained a random mixture of right- and left-handed propellers. For clarity, the crystal structure in Figure 4 is shown with only right-handed propeller units. The 1H NMR spectra of cages 12 and 13 in acetonitrile at 25 °C (400 and 500 MHz) were consistent with fast rotation of the phenylene moieties on the NMR chemical shift time scale in solution.

The framework of 12 can be viewed as a truncated tetrahedron bearing four trigonal aromatic panels and four empty panels, with PdII centers describing the vertices of an octahedron. These features recall the PdII6(tris(4-pyridyl)-1,3,5-triazine)4 coordination cages first reported by Fujita et al. in 1995 and intensively studied since then.33 In comparison, 12·Cl6 shows shorter Pd–Pd distances than the purely coordination cage studied by Fujita (15.0–16.0 Å between antipodal Pd centers and 10.9–11.5 Å for adjacent pairs of Pd ions in 12·Cl6 vs 18.1–18.8 and 12.7–13.4 Å for PdII6(tris(4-pyridyl)-1,3,5-triazine)4 with various bidentate peripheral ligands33). In addition to the smaller size of 12, it differs from the Fujita cage in having a covalent framework, trans-coordinated imines around each PdII, and an extra single binding site per PdII center, all oriented toward the central cavity of 12. The angles between phenylene rings around PdII centers are in the range α = 90°–95°, in common with the other structures that incorporate this motif. We could not obtain single crystals of the larger 13·Cl9 cage, but a PM3 model minimized to a structure having α = 89°–95° [Figure 4, and Table S8 (SI)].23

In addition to chloride, the anions bromide, iodide, and thiocyanate were also tested as prospective inner ligands. Solutions of 12·(MeCN)6 and 13·(MeCN)9 were treated with these anions as nBu4N+ salts (Figure S72, SI). Bromide provided 12·Br6 and 13·Br9, which had sharp 1H NMR spectra at similar chemical shifts to 12·Cl6 and 13·Cl9, but the bromide adducts were not stable enough for ESI-MS analyses. Both the chloride and bromide adducts of 12 and 13 remained stable in solution in MeCN over weeks at 25 °C and overnight at 60 °C; heating for longer was not tested. In contrast, iodide and thiocyanate led to broadened 1H NMR signals and precipitation over a period of hours. We infer that the larger sizes of these two anions may lead to steric clashes with the proximate phenyl groups, thus destabilizing the structures.

We were not able to separate cages 12 and 13 using a size-exclusion column due to their poor solubility in the solvents used as eluents. The mixture of 12·(MeCN)6 and 13·(MeCN)9 with BF4– as counteranions could be isolated in the solid state and subsequently dissolved in MeCN, but the mixture of 12·Cl6 and 13·Cl9 did not redissolve after drying. This lack of solubility was surprising considering that the complexes were not observed to precipitate from MeCN over 1 month at 25 °C, suggesting slow kinetics of dissolution for the dry material rather than low solubility. We therefore replaced the BF4– counteranions with bulkier NTf2– to accelerate dissolution. Intriguingly, the triflimide salt of 12·Cl6 dissolved more rapidly than 13·Cl9, which allowed sample enrichment through multiple washes with fresh MeCN (see Figure 4C,D and Supporting Information, section 1.11). Although 12·(MeCN)6 and 13·(MeCN)9 exhibited dynamic imine exchange (see below), no conversion was observed between 12·Cl6 and 13·Cl9 at 25 °C in MeCN over 1 month.

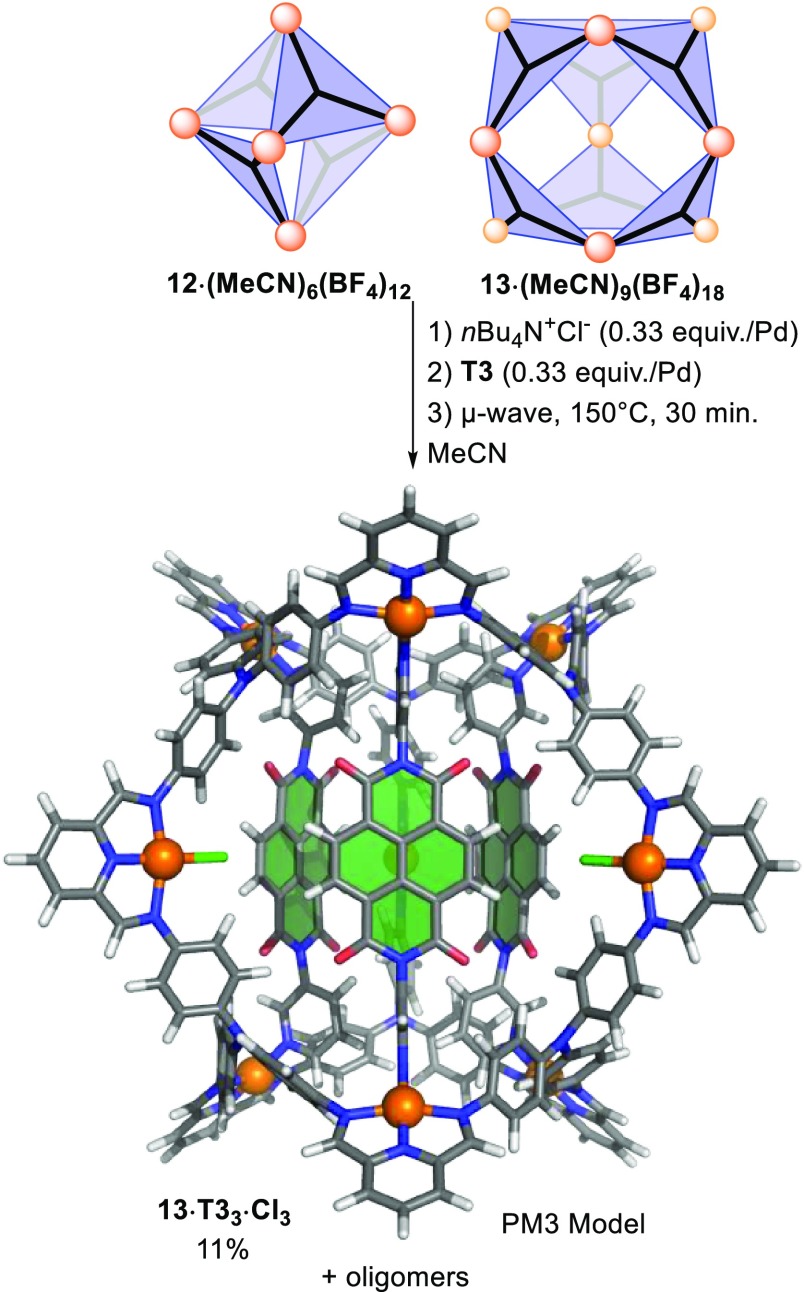

We then investigated the effects of multivalent templates coordinating to the inward-facing PdII sites of these three-dimensional cage structures. Mixtures of 12·(MeCN)6 and 13·(MeCN)9 were treated with T1 and T2 to see if they would selectively template Pd6 cage 12, Pd9 cage 13, or the larger Pd12 cage of Figure 3, which contain faces consisting of trimeric and tetrameric macrocycles. Numerous attempts using different amounts of template did not induce selectivity, leading instead to highly complex NMR and ESI-MS spectra (see Table S1, SI). As the 5·T1 and 6·T2 macrocycles described above adopted non-cone conformers, we infer that the analogous macrocyclic subunits of the structures formed from 11 with templates T1 and T2 would also form non-cone conformers, which are not configured for cage formation.

We then tested the ability of NDI-based bis(pyridine) T3 to selectively template cage 13·T33 (Scheme 4), because cage 13 contains a pair of Pd3 rings that are held in a similar configuration as in the bridged macrocycles of 52·T33. Our initial attempts at mixing 1, 11, [Pd(MeCN)4](BF4)2, and T3 in a 9:6:6:3 ratio were unsuccessful (see Table S1), but addition of nBu4N+Cl– (0.33 equiv/Pd) provided 13·T33·Cl3 in ca. 10% yield according to NMR and ESI-MS analyses [Scheme 4 and Figures S64 and S65 (SI)]. PM3 models of 13·T33·(MeCN)3 and 13·T33·Cl3 suggested that the internal MeCN ligands in the former would clash with the three central T3, whereas chloride in the latter complex would not [Scheme 4 and Table S9 (SI)].23 We infer that this lack of clash in 13·T33·Cl3 underpins the importance of chloride for the formation of this cage.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of Templated Cage 13·T33·Cl3.

The PM3 model was optimized with right-handed triphenylamine propellers, arbitrarily.

The 1H NMR spectrum of crude 13·T33·Cl3 clearly shows the 17 signals expected for the D3h-symmetric product, along with a set of broad signals that could correspond to oligomeric byproducts. Comparison between the integrals of the 13·T33·Cl3 product and nBu4N+ signals was used to gauge the yield, which was never observed to increase beyond 11%. Different attempted optimizations included running the reaction at 150 °C in a microwave reactor and changing the order of addition of the starting materials (Table S1, SI). Isolation of 13·T33·Cl3 from the putative oligomer coproducts by size-exclusion column was prevented by the lack of product solubility in the solvents used as eluents. The templated formation of a single discrete species nonetheless shows the potential for templation involving the bis(imino)pyridyl-PdII building block for the construction of covalent metallocages. Careful optimization of template geometry may enable the yields of specific cage products to be further improved.

The mixture of 12·Cl6 and 13·Cl9 was subjected to the optimized imine reduction conditions used for macrocycles 5·T1 and 6·T2 (Figures S66–S68, SI). ESI-MS monitoring of the reaction showed effective reduction of all imine bonds, but NMR spectra of the crude product were indecipherable, as expected considering the numerous stereoisomers originating from the NH stereocenters of the reduced cages, as was observed in the cases of 7·T1 and 8·T2. Treatment with ethylenediamine in DMSO led to species with broad 1H NMR signals in the anticipated chemical shift regions for the demetalated and reduced cages (Figure S68, SI). We infer the broadness to be a consequence of slow interconversion between different hydrogen-bonded conformers. Precipitation of the demetalated cages by adding water afforded a solid that only dissolved in highly acidic aqueous solutions [i.e. > 4 M HCl(aq)]. Degradation appeared to accompany dissolution, as no trace of the product was observed by 1H NMR in DCl/D2O. The product was also suspended in 17 organic solvents, including chlorinated, aromatic, aliphatic, polar, apolar, protic, and aprotic solvents, with no evidence of dissolution (see Supporting Information, section 1.13). This lack of solubility prevented further characterization, purity, and yield determination. Building blocks that incorporate solubilizing moieties may allow for soluble covalent organic cages to be prepared.

Aniline Exchange

Dynamic covalent imines can exchange aniline residues with free anilines.35 The side of the equilibrium favored depends upon the stoichiometry and relative nucleophilicities of the anilines. Aniline exchange was previously used to modify the periphery of self-assembled structures36 but, to the best of our knowledge, has not yet been applied to the construction of assemblies whose cores consist of multitopic aniline residues displacing monoanilines, as reported herein. For the previously reported peripheral modifications, excess aniline could be added to ensure complete exchange. In the present case, however, such an excess would be impractical as it would result in a mixture of products that incorporated multitopic anilines that had not fully reacted.

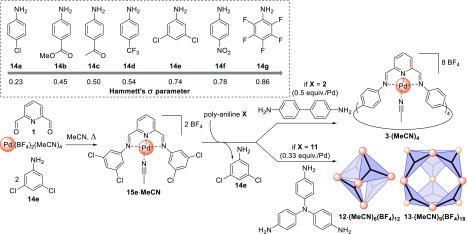

We thus screened several electron-poor monoanilines 14a–14g (Figure 5) for the formation of the corresponding bis(imino)pyridyl-PdII complexes 15a–15g. We then evaluated the efficiency of the displacement of these different electron-poor aniline residues by the more electron-rich bis-aniline 2 to form macrocycle 3. Aniline 14e (Figure 5) was observed to give the best result; full details are provided in Figures S74–S77 and the accompanying text (SI).

Figure 5.

Imine exchange by polyanilines on mononuclear bis(imino)pyridyl-PdII15e led to larger assemblies. Inset: List of electron-poor monoanilines tested and their Hammett σ parameters;34 for 14g, the unreported fluorine σortho value was approximated by the known σpara.

The electron densities of the monoanilines were assessed on the basis of the Hammett σ parameters of their substituents.34 Monoanilines 14a–14f formed the corresponding bis(imino)pyridyl-PdII complexes 15a–15f cleanly, as gauged by 1H NMR (Figure S74, SI). The most electron-deficient aniline, 14g, failed to generate the imine complex, however.

The displacement of the aniline residues 14a–14f by benzidine 2 occurred in better yield as the electron-deficiency of the leaving aniline increased (Figure S77, SI). The monoanilines that yielded macrocycle 3 the most efficiently were thus 3,5-dichloroaniline 14e and 4-nitroaniline 14f, which possess a similar degree of electron-deficiency according to their Hammett σ parameters (σ14e = 0.74 vs σ14f = 0.78).

The corresponding mononuclear complexes 15e and 15f were treated with tris-aniline 11 to evaluate the formation of cages 12 and 13 through aniline exchange. Both reactions afforded the desired cages (Figures S78 and S79, SI), but 15f also led to an extra set of unidentified 1H NMR peaks. Aniline 14e was therefore selected as the best aniline leaving group for aniline exchange. Templated cage 13·T33·Cl3 was also successfully prepared through aniline exchange, albeit in low yield, similarly to the direct synthesis (Figure S80, SI).

Conclusions

The bis(imino)pyridyl-PdII motif thus serves as a 90° building block to generate a wide variety of dynamic covalent metal-containing macrocycles and cages. This motif provides some flexibility, adopting angles that range from 85° to 97°. The free coordination site on the PdII center oriented to the inside of the assemblies allows the stability and shape of the covalent assemblies to be tuned, as well as permitting covalent assemblies to be bridged by multitopic ligands in order to form more complex supramolecular assemblies. Efficient imine reduction conditions were developed to afford covalent organic macrocycles in good yields from these multi-imino PdII complexes. Future work will focus upon the extension of these methods to generate larger structures and the use of other metal cations with similar tridentate building blocks,37 which could lead to different angles and more free coordination sites. The imine-containing macrocycles and cages reported herein could also be good candidates to undergo oxidation to amides, as recently reported by Mastalerz et al. in the context of another imine-based covalent cage.38 Furthermore, we will explore the potential of the new reduced and demetalated macrocycles and cages for guest recognition, including anionic guests via hydrogen bonding and metal cations via coordination to the tridentate sites.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the European Research Council (695009) and the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC, EP/P027067/1). R.L. was funded by the Fondation Wiener-Anspach postdoctoral fellowship. We thank Diamond Light Source for time on Beamline I19 (MT15768). We thank the National Mass Spectrometry Facility at the University of Swansea for high-resolution mass spectrometry analyses of 7·T1, 8·T2, 9, and 10.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.9b06182.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Szejtli J. Introduction and General Overview of Cyclodextrin Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 1743–1753. 10.1021/cr970022c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lagona J.; Mukhopadhyay P.; Chakrabarti S.; Isaacs L. The Cucurbit[n]uril Family. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4844–4870. 10.1002/anie.200460675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Xue M.; Yang Y.; Chi X.; Zhang Z.; Huang F. Pillararenes, A New Class of Macrocycles for Supramolecular Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 1294–1308. 10.1021/ar2003418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Calixarenes and Beyond; Neri P., Sessler J. L., Wang M.-X., Eds.; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]; e Hiroto S.; Miyake Y.; Shinokubo H. Synthesis and Functionalization of Porphyrins through Organometallic Methodologies. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 2910–3043. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Assaf K. I.; Nau W. M. Cucurbiturils: from synthesis to high-affinity binding and catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 394–418. 10.1039/C4CS00273C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Lee S.; Chen C.-H.; Flood A. H. A pentagonal cyanostar macrocycle with cyanostilbene CH donors binds anions and forms dialkylphosphate [3]rotaxanes. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 704–710. 10.1038/nchem.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Šolomek T.; Powers-Riggs N. E.; Wu Y.-L.; Young R. M.; Krzyaniak M. D.; Horwitz N. E.; Wasielewski M. R. Electron Hopping and Charge Separation within a Naphthalene-1,4:5,8-bis(dicarboximide) Chiral Covalent Organic Cage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 3348–3351. 10.1021/jacs.7b00233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang X.; Wang Y.; Yang H.; Fang H.; Chen R.; Sun Y.; Zheng N.; Tan K.; Lu X.; Tian Z.; Cao X. Assembled molecular face-rotating polyhedra to transfer chirality from two to three dimensions. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12469. 10.1038/ncomms12469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Collins M. S.; Phan N.-M.; Zakharov L. N.; Johnson D. W. Coupling Metaloid-Directed Self-Assembly and Dynamic Covalent Systems as a Route to Large Organic Cages and Cyclophanes. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 3486–3496. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Greenaway R. L.; Santolini V.; Bennison M. J.; Alston B. M.; Pugh C. J.; Little M. A.; Miklitz M.; Eden-Rump E. G. B.; Clowes R.; Shakil A.; Cuthbertson H. J.; Armstrong H.; Briggs M. E.; Jelfs K. E.; Cooper A. I. High-throughput discovery of organic cages and catenanes using computational screening fused with robotic synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2849. 10.1038/s41467-018-05271-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Song Q.; Jiang S.; Hasell T.; Liu M.; Sun S.; Cheetham A. K.; Sivaniah E.; Cooper A. I. Porous Organic Cage Thin Films and Molecular-Sieving Membranes. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 2629–2637. 10.1002/adma.201505688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Mukhopadhyay R. D.; Kim Y.; Koo J.; Kim K. Porphyrin Boxes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2730–2738. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Mastalerz M. Porous Shape-Persistent Organic Cage Compounds of Different Size, Geometry, and Function. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2411–2422. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Tozawa T.; Jones J. T. A.; Swamy S. I.; Jiang S.; Adams D. J.; Shakespeare S.; Clowes R.; Bradshaw D.; Hasell T.; Chong S. Y.; Tang C.; Thompson S.; Parker J.; Trewin A.; Bacsa J.; Slawin A. M. Z.; Steiner A.; Cooper A. I. Porous organic cages. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 973–978. 10.1038/nmat2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Giri N.; Del Pópolo M. G.; Melaugh G.; Greenaway R. L.; Rätzke K.; Koschine T.; Pison L.; Costa Gomes M. F.; Cooper A. I.; James S. L. Liquids with permanent porosity. Nature 2015, 527, 216–220. 10.1038/nature16072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Zhang G.; Mastalerz M. Organic cage compounds – from shape-persistency to function. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 1934–1947. 10.1039/C3CS60358J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Zhang D.; Martinez A.; Dutasta J.-P. Emergence of Hemicryptophanes: From Synthesis to Applications for Recognition, Molecular Machines, and Supramolecular Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 4900–4942. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Acharyya K.; Mukherjee P. S. A fluorescent organic cage for picric acid detection. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 15788–15791. 10.1039/C4CC06225F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kang S. O.; Day V. W.; Bowman-James K. Fluoride: Solution- and Solid-State Structural Binding Probe. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 277–283. 10.1021/jo901581w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Rios P.; Carter T. S.; Mooibroek T. J.; Crump M. P.; Lisbjerg M.; Pittelkow M.; Supekar N. T.; Boons G.-J.; Davis A. P. Synthetic Receptors for the High-Affinity Recognition of O-GlcNAc Derivatives. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3387–3392. 10.1002/anie.201510611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Tromans R. A.; Carter T. S.; Chabanne L.; Crump M. P.; Li H.; Matlock J. V.; Orchard M. G.; Davis A. P. A biomimetic receptor for glucose. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 52–56. 10.1038/s41557-018-0155-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Akine S.; Miyashita M.; Nabeshima T. A Metallo-molecular Cage That Can Close the Apertures with Coordination Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 4631–4634. 10.1021/jacs.7b00840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Liu Y.; Shen J.; Sun C.; Ren C.; Zeng H. Intramolecularly Hydrogen-Bonded Aromatic Pentamers as Modularly Tunable Macrocyclic Receptors for Selective Recognition of Metal Ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 12055–12063. 10.1021/jacs.5b07123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Yawer M. A.; Havel V.; Sindelar V. A Bambusuril Macrocycle that Binds Anions in Water with High Affinity and Selectivity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 276–279. 10.1002/anie.201409895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Kang S. O.; Llinares J. M.; Powell D.; VanderVelde D.; Bowman-James K. New Polyamide Cryptand for Anion Binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 10152–10153. 10.1021/ja034969+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Shi Y.; Cai K.; Xiao H.; Liu Z.; Zhou J.; Shen D.; Qiu Y.; Guo Q.-H.; Stern C.; Wasielewski M. R.; Diederich F.; Goddard W. A. III; Stoddart J. F. Selective Extraction of C70 by a Tetragonal Prismatic Porphyrin Cage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13835–13842. 10.1021/jacs.8b08555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Delahousse G.; Lavendomme R.; Jabin I.; Agasse V.; Cardinael P. Calixarene-based stationary phases for chromatography. Curr. Org. Chem. 2015, 19, 2237–2249. 10.2174/1385272819666150713180425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Roy B.; Devaraj A.; Saha R.; Jharimune S.; Chi K.-W.; Mukherjee P. S. Catalytic Intramolecular Cycloaddition Reactions by Using a Discrete Molecular Architecture. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 15704–15712. 10.1002/chem.201702507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Das P.; Kumar A.; Howlader P.; Mukherjee P. S. A Self-Assembled Trigonal Prismatic Molecular Vessel for Catalytic Dehydration Reactions in Water. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 12565–12574. 10.1002/chem.201702263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mondal B.; Acharyya K.; Howlader P.; Mukherjee P. S. Molecular Cage Impregnated Palladium Nanoparticles: Efficient, Additive-Free Heterogeneous Catalysts for Cyanation of Aryl Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1709–1716. 10.1021/jacs.5b13307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Mondal B.; Mukherjee P. S. Cage Encapsulated Gold Nanoparticles as Heterogeneous Photocatalyst for Facile and Selective Reduction of Nitroarenes to Azo Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12592–12601. 10.1021/jacs.8b07767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattiuzzi A.; Jabin I.; Mangeney C.; Roux C.; Reinaud O.; Santos L.; Bergamini J.-F.; Hapiot P.; Lagrost C. Electrografting of calix[4]arenediazonium salts to form versatile robust platforms for spatially controlled surface functionalization. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1130. 10.1038/ncomms2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a The Nature of the Mechanical Bond: From Molecules to Machines; Bruns C. J., Stoddart J. F., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2017. [Google Scholar]; b Collin J.-P.; Dietrich-Buchecker C.; Gaviña P.; Jimenez-Molero M. C.; Sauvage J.-P. Shuttles and Muscles: Linear Molecular Machines Based on Transition Metals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001, 34, 477–487. 10.1021/ar0001766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Jamieson E. M. G.; Modicom F.; Goldup S. M. Chirality in rotaxanes and catenanes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 5266–5311. 10.1039/C8CS00097B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Template Synthesis of Macrocyclic Compounds; Gerbeleu N. V., Arion V. B., Burgess J., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]; b Mirzaei S.; Wang D.; Lindeman S. V.; Sem C. M.; Rathore R. Highly Selective Synthesis of Pillar[n]arene (n = 5, 6). Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 6583–6586. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b02937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Bols P. S.; Anderson H. L. Template-Directed Synthesis of Molecular Nanorings and Cages. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2083–2092. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Jin Y.; Wang Q.; Taynton P.; Zhang W. Dynamic Covalent Chemistry Approaches Toward Macrocycles, Molecular Cages, and Polymers. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1575–1586. 10.1021/ar500037v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ono K.; Iwasawa N. Dynamic Behavior of Covalent Organic Cages. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 17856–17868. 10.1002/chem.201802253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mastalerz M. Shape-Persistent Organic Cage Compounds by Dynamic Covalent Bond Formation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5042–5053. 10.1002/anie.201000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Acharyya K.; Mukherjee P. S. Organic Imine Cages: Molecular Marriage and Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 8640–8653. 10.1002/anie.201900163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lauer J. C.; Zhang W.-S.; Rominger F.; Schröder R. R.; Mastalerz M. Shape-Persistent [4 + 4] Imine Cages with a Truncated Tetrahedral Geometry. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 1816–1820. 10.1002/chem.201705713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Beaudoin D.; Rominger F.; Mastalerz M. Chiral Self-Sorting of [2 + 3] Salicylimine Cage Compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1244–1248. 10.1002/anie.201610782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Jiao T.; Chen L.; Yang D.; Li X.; Wu G.; Zeng P.; Zhou A.; Yin Q.; Pan Y.; Wu B.; Hong X.; Kong X.; Lynch V. M.; Sessler J. L.; Li H. Trapping White Phosphorus within a Purely Organic Molecular Container Produced by Imine Condensation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 14545–14550. 10.1002/anie.201708246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Elbert S. M.; Regenauer N. I.; Schindler D.; Zhang W.-S.; Rominger F.; Schröder R. R.; Mastalerz M. Shape-Persistent Tetrahedral [4 + 6] Boronic Ester Cages with Different Degrees of Fluoride Substitution. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 11438–11443. 10.1002/chem.201802123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ono K.; Shimo S.; Takahashi K.; Yasuda N.; Uekusa H.; Iwasawa N. Dynamic Interconversion between Boroxine Cages Based on Pyridine Ligation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 3113–3117. 10.1002/anie.201713221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaglio D.; Zappia G.; De Paolis E.; Balducci S.; Botta B.; Ghirga F. Olefin metathesis reaction as a locking tool for macrocycle and mechanomolecule construction. Org. Chem. Front. 2018, 5, 3022–3055. 10.1039/C8QO00728D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang Q.; Yu C.; Zhang C.; Long H.; Azarnoush S.; Jin Y.; Zhang W. Dynamic covalent synthesis of aryleneethynylene cages through alkyne metathesis: dimer, tetramer, or interlocked complex?. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 3370–3376. 10.1039/C5SC04977F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lee S.; Yang A.; Moneypenny T. P. II; Moore J. S. Kinetically Trapped Tetrahedral Cages via Alkyne Metathesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2182–2185. 10.1021/jacs.6b00468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fujita M. Metal-directed self-assembly of two- and three-dimensional synthetic receptors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1998, 27, 417–425. 10.1039/a827417z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Leininger S.; Olenyuk B.; Stang P. J. Self-Assembly of Discrete Cyclic Nanostructures Mediated by Transition Metals. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 853–908. 10.1021/cr9601324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Seidel S. R.; Stang P. J. High-Symmetry Coordination Cages via Self-Assembly. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 972–983. 10.1021/ar010142d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Chakrabarty R.; Mukherjee P. S.; Stang P. J. Supramolecular Coordination: Self-Assembly of Finite Two- and Three-Dimensional Ensembles. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6810–6918. 10.1021/cr200077m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Zhang D.; Ronson T. K.; Nitschke J. R. Functional Capsules via Subcomponent Self-Assembly. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2423–2436. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f McConnell A. J.; Wood C. S.; Neelakandan P. P.; Nitschke J. R. Stimuli-Responsive Metal-Ligand Assemblies. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7729–7793. 10.1021/cr500632f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Zhou X.-P.; Liu J.; Zhan S.-Z.; Yang J.-R.; Li D.; Ng K.-M.; Sun R. W.-Y.; Che C.-M. A High-Symmetry Coordination Cage from 38- or 62-Component Self-Assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8042–8045. 10.1021/ja302142c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Han Y.-F.; Jin G.-X. Half-Sandwich Iridium- and Rhodium-based Organometallic Architectures: Rational Design, Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 3571–3579. 10.1021/ar500335a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Zhang Y.-Y.; Shen X.-Y.; Weng L.-H.; Jin G.-X. Octadecanuclear Macrocycles and Nonanuclear Bowl-Shaped Structures Based on Two Analogous Pyridyl-Substituted Imidazole-4,5-dicarboxylate Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 15521–15524. 10.1021/ja5096914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Debata N. B.; Tripathy D.; Chand D. K. Self-assembled coordination complexes from various palladium(II) components and bidentate or polydentate ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 1831–1945. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Fujita M.; Tominaga M.; Hori A.; Therrien B. Coordination Assemblies from a Pd(II)-Cornered Square Complex. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005, 38, 369–378. 10.1021/ar040153h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sakata Y.; Yamamoto R.; Saito D.; Tamura Y.; Maruyama K.; Ogoshi T.; Akine S. Metallonanobelt: A Kinetically Stable Shape-Persistent Molecular Belt Prepared by Reversible Self-Assembly Processes. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 15500–15506. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b02804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Samanta D.; Gemen J.; Chu Z.; Diskin-Posner Y.; Shimon L. J. W.; Klajn R. Reversible photoswitching of encapsulated azobenzenes in water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 9379–9384. 10.1073/pnas.1712787115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Yamashina M.; Kusaba S.; Akita M.; Kikuchi T.; Yoshizawa M. Cramming versus threading of long amphiphilic oligomers into a polyaromatic capsule. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4227. 10.1038/s41467-018-06458-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Fujita D.; Ueda Y.; Sato S.; Mizuno N.; Kumasaka T.; Fujita M. Self-assembly of tetravalent Goldberg polyhedra from 144 small components. Nature 2016, 540, 563–566. 10.1038/nature20771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Zhu R.; Regeni I.; Holstein J. J.; Dittrich B.; Simon M.; Prévost S.; Gradzielski M.; Clever G. H. Catenation and Aggregation of Multi-Cavity Coordination Cages. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 13652–13656. 10.1002/anie.201806047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albéniz A. C.; Espinet P.. Palladium: Inorganic & Coordination Chemistry. In Encyclopedia of Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry; Scott R. A., Ed.; Wiley, 2011; 10.1002/9781119951438.eibc0164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browne C.; Ronson T. K.; Nitschke J. R. Palladium-Templated Subcomponent Self-Assembly of Macrocycles, Catenanes, and Rotaxanes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 10701–10705. 10.1002/anie.201406164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Related 2,6-bis(ketimino)pyridyl–PdII mononuclear complexes reported by Liu et al. show similar structural properties; see the following:; a Liu P.; Zhou L.; Li X.; He R. Bis(imino)pyridine palladium(II) complexes: Synthesis, structure and catalytic activity. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009, 694, 2290–2294. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2009.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Liu P.; Yan M.; He R. Bis(imino)pyridine palladium(II) complexes as efficient catalysts for the Suzuki-Miyaura reaction in water. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2009, 24, 131–134. 10.1002/aoc.1591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai A.; Nakamura T.; Nabeshima T. A twisted macrocyclic hexanuclear palladiumcomplex with internal bulky coordinating ligands. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2421–2424. 10.1039/C8CC09643K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fujita M.; Yazaki J.; Ogura K. Preparation of a macrocyclic polynuclear complex, [(en)Pd(4,4′-bpy)]4(NO3)8 (en = ethylenediamine, bpy = bipyridine), which recognizes an organic molecule in aqueous media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 5645–5647. 10.1021/ja00170a042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Fujita M.; Sasaki O.; Mitsuhashi T.; Fujita T.; Yazaki J.; Yamaguchi K.; Ogura K. On the structure of transition-metal-linked molecular squares. Chem. Commun. 1996, 0, 1535–1536. 10.1039/cc9960001535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stang P. J.; Cao D. H.; Saito S.; Arif A. M. Self-Assembly of Cationic, Tetranuclear, Pt(II) and Pd(II) Macrocyclic Squares. X-ray Crystal Structure of [Pt2+(dppp)(4,4′-bipyridyl)2–OSO2CF3]4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 6273–6283. 10.1021/ja00128a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. J. P. Optimization of parameters for semiempirical methods V: Modification of NDDO approximations and application to 70 elements. J. Mol. Model. 2007, 13, 1173–1213. 10.1007/s00894-007-0233-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCIGRESS; Fujitsu Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- a Fujita N.; Biradha K.; Fujita M.; Sakamoto S.; Yamaguchi K. A Porphyrin Prism: Structural Switching Triggered by Guest Inclusion. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 1718–1721. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bar A. K.; Mohapatra S.; Zangrando E.; Mukherjee P. S. A Series of Trifacial Pd6 Molecular Barrels with Porphyrin Walls. Chem. - Eur. J. 2012, 18, 9571–9579. 10.1002/chem.201201077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- By analogy with the conformers observed in calixarenes (concave oligomeric macrocycles that can also present inversion of separate units), we will name the conformers of the present macrocycles with the same nomenclature. For more details, see the following:Gutsche C. D. In Calixarenes: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Stoddart J. F., Ed.; Monographs in Supramolecular Chemistry; The Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Martí-Centelles V.; Pandey M. D.; Burguete M. I.; Luis S. V. Macrocyclization Reactions: The Importance of Conformational, Configurational, and Template-Induced Preorganization. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8736–8834. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Leung K. C.-F.; Aricó F.; Cantrill S. J.; Stoddart J. F. Template-Directed Dynamic Synthesis of Mechanically Interlocked Dendrimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 5808–5810. 10.1021/ja0501363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rowan S. J.; Stoddart J. F. Thermodynamic Synthesis of Rotaxanes by Imine Exchange. Org. Lett. 1999, 1, 1913–1916. 10.1021/ol991047w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Dancey K. P.; Dell A.; Henrick K.; Judd P. M.; Owston P. G.; Peters R.; Tasker P. A.; Turner R. W. Dinucleating octaaza macrocyclic ligands from simple imine condensations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 4952–4954. 10.1021/ja00406a053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Jackson T. W.; Kojima M.; Lambrecht R. M.; Marubayashi N.; Hiratake M. Reduction of 6,6,9,9-tetramethylhexahydroimidazo[2,1-d][1,2,5]dithiazepine with borane. Aust. J. Chem. 1994, 47, 2271–2277. 10.1071/CH9942271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Lu Z. H.; Bhongle N.; Su X.; Ribe S.; Senanayake C. H. Novel diacid accelerated borane reducing agent for imines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 8617–8620. 10.1016/S0040-4039(02)01905-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f De Kimpe N.; Stevens C. A convenient method for the synthesis of β-chloroamines by electrophilic reduction of α-chloroimines. Tetrahedron 1991, 47, 3407–3416. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)86404-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Nimse S. B.; Nguyen V.-T.; Kim J.; Kim H.-S.; Song K.-S.; Eoum W.-Y.; Jung C.-Y.; Ta V.-T.; Seelam S. R.; Kim T. Water-soluble aminocalix[4]arene receptors with hydrophobic and hydrophilic mouths. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 2840–2845. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.03.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Kerneghan P. A.; Halperin S. D.; Bryce D. L.; Maly K. E. Postsynthetic modification of an imine-based microporous organic network. Can. J. Chem. 2011, 89, 577–582. 10.1139/v11-014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Das U. K.; Daifuku S. L.; Iannuzzi T. E.; Gorelsky S. I.; Korobkov I.; Gabidullin B.; Neidig M. L.; Baker R. T. Iron(II) Complexes of a Hemilabile SNS Amido Ligand: Synthesis, Characterization, and Reactivity. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 13766–13776. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b01802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Akita S.; Nakano R.; Ito S.; Nozaki K. Synthesis and Reactivity of Methylpalladium Complexes Bearing a Partially Saturated IzQO Ligand. Organometallics 2018, 37, 2286–2296. 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Hunter C. A.; Anderson H. L. What is Cooperativity?. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7488–7499. 10.1002/anie.200902490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b von Krbek L. K. S.; Schalley C. A.; Thordarson P. Assessing cooperativity in supramolecular systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 2622–2637. 10.1039/C7CS00063D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavity volume calculated with PLATON software: probe radius = 1.2 Å; grid step = 0.1 Å; atomic radii: C = 1.70 Å; H = 1.20 Å; N = 1.55 Å; O = 1.52 Å; Pd = 1.63 Å. See the following:Spek A. L. Structure validation in chemical crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. 2009, D65, 148–155. 10.1107/S090744490804362X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranchemontagne D. J.; Ni Z.; O’Keeffe M.; Yaghi O. M. Reticular Chemistry of Metal–Organic Polyhedra. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 5136–5147. 10.1002/anie.200705008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A tetrafold connector [tetrakis(4-aminophenyl)porphyrin] was also considered for potential cage formation, but geometrical features of this building block prevented the formation of a discrete structure (see SI and Figures S81 and S82 for details).

- a Bilbeisi R. A.; Clegg J. K.; Elgrishi N.; de Hatten X.; Devillard M.; Breiner B.; Mal P.; Nitschke J. R. Subcomponent Self-Assembly and Guest-Binding Properties of Face-Capped Fe4L48+ Capsules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 5110–5119. 10.1021/ja2092272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rizzuto R. J.; Wu W.-Y.; Ronson T. K.; Nitschke J. R. Peripheral Templation Generates an MII6L4 Guest-Binding Capsule. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 7958–7962. 10.1002/anie.201602135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Rizzuto R. J.; Kieffer M.; Nitschke J. R. Quantified structural speciation in self-sorted CoII6L4 cage systems. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 1925–1930. 10.1039/C7SC04927G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fujita M.; Oguro D.; Miyazawa M.; Oka H.; Yamaguchi K.; Ogura K. Self-assembly of ten molecules into nanometre-sized organic host frameworks. Nature 1995, 378, 469–471. 10.1038/378469a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Yoshizawa M.; Tamura M.; Fujita M. Diels-Alder in Aqueous Molecular Hosts: Unusual Regioselectivity and Efficient Catalysis. Science 2006, 312, 251–254. 10.1126/science.1124985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Yoshizawa M.; Kusukawa T.; Kawano M.; Ohhara T.; Tanaka I.; Kurihara K.; Niimura N.; Fujita M. Endohedral Clusterization of Ten Water Molecules into a “Molecular Ice” within the Hydrophobic Pocket of a Self-Assembled Cage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 2798–2799. 10.1021/ja043953w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Furusawa T.; Kawano M.; Fujita M. The Confined Cavity of a Coordination Cage Suppresses the Photocleavage of α-Diketones To Give Cyclization Products through Kinetically Unfavorable Pathways. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 5717–5719. 10.1002/anie.200701250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Takezawa H.; Murase T.; Resnati G.; Metrangolo P.; Fujita M. Recognition of Polyfluorinated Compounds Through Self-Aggregation in a Cavity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 1786–1788. 10.1021/ja412893c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Belowich M. E.; Stoddart J. F. Dynamic imine chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2003–2024. 10.1039/c2cs15305j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Vardhan H.; Mehta A.; Nath I.; Verpoort F. Dynamic imine chemistry in metal–organic polyhedra. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 67011–67030. 10.1039/C5RA10801B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Kovaříček P.; Lehn J.-M. Merging Constitutional and Motional Covalent Dynamics in Reversible Imine Formation and Exchange Processes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 9446–9455. 10.1021/ja302793c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hristova Y. R.; Smulders M. M. J.; Clegg J. K.; Breiner B.; Nitschke J. R. Selective anion binding by a “Chameleon” capsule with a dynamically reconfigurable exterior. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 638–641. 10.1039/C0SC00495B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Wood C. S.; Ronson T. K.; Belenguer A. M.; Holstein J. J.; Nitschke J. R. Two-stage directed self-assembly of a cyclic [3]catenane. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 354–358. 10.1038/nchem.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Roberts D. A.; Pilgrim B. S.; Sirvinskaite G.; Ronson T. K.; Nitschke J. R. Covalent Post-assembly Modification Triggers Multiple Structural Transformations of a Tetrazine-Edged Fe4L6 Tetrahedron. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9616–9623. 10.1021/jacs.8b05082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansch C.; Leo A.; Taft R. W. A survey of Hammett substituent constants and resonance and field parameters. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 165–195. 10.1021/cr00002a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Hogg L.; Leigh D. A.; Lusby P. J.; Morelli A.; Parsons S.; Wong J. K. Y. A Simple General Ligand System for Assembling Octahedral Metal–Rotaxane Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 1218–1221. 10.1002/anie.200353186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastalerz M.; Bhat A.; Elbert S.; Rominger F.; Zhang W.-S.; Schröder R.; Dieckmann M. Transformation of a [4 + 6] Salicylbisimine Cage to Chemically Robust Amide Cages. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 8819–8823. 10.1002/anie.201903631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.