Abstract

Background and Aims

Polyploidy is an important driver of plant diversification and adaptation to novel environments. As a consequence of genome doubling, polyploids often exhibit greater colonizing ability or occupy a wider ecological niche than diploids. Although elevation has been traditionally considered as a key driver structuring ploidy variation, we do not know if environmental and phenotypic differentiation among ploidy cytotypes varies along an elevational gradient. Here, we tested for the consequences of genome duplication on genetic diversity, phenotypic variation and habitat preferences on closely related diploid and tetraploid populations that coexist along approx. 2300 m of varying elevation.

Methods

We sampled and phenotyped 45 natural diploid and tetraploid populations of Arabidopsis arenosa in one mountain range in Central Europe (Western Carpathians) and recorded abiotic and biotic variables at each collection site. We inferred genetic variation, population structure and demographic history in a sub-set of 29 populations genotyped for approx. 36 000 single nucleotide polymorphisms.

Key Results

We found minor effects of polyploidy on colonization of alpine stands and low genetic differentiation between the two cytotypes, mirroring recent divergence of the polyploids from the local diploid lineage and repeated reticulation events among the cytotypes. This pattern was corroborated by the absence of ecological niche differentiation between the two cytotypes and overall phenotypic similarity at a given elevation.

Conclusions

The case of A. arenosa contrasts with previous studies that frequently showed clear niche differentiation between cytotypes. Our work stresses the importance of considering genetic structure and past demographic processes when interpreting the patterns of ploidy distributions, especially in species that underwent recent polyploidization events.

Keywords: Alpine adaptation, Arabidopsis arenosa, genetic variation, multivariate statistics, niche differentiation, polyploidy, RAD-sequencing

INTRODUCTION

Polyploidy refers to the process of multiplication of the entire chromosome set leading to an increase in genome size (Adams and Wendel, 2005; Otto, 2007). It has long been recognized as a widespread phenomenon among eukaryotes in general and plants in particular (Stebbins, 1950; Otto and Whitton, 2000; Adams and Wendel, 2005), and considered as an important driver of plant diversification and adaptation to novel environments (Levin, 1983; Parisod et al., 2010; Van de Peer et al., 2017). Indeed, polyploids often differ in genetic, physiological or morphological features that may confer adaptive advantages compared with their diploid parents (Levin, 1983; Otto and Whitton, 2000; Comai, 2005). Consequently, polyploids may exhibit wider ecological ranges or occupy harsher environments (Brochmann et al., 2004), and the consequent shift in habitat preferences between the different cytotypes may facilitate their coexistence (Parisod et al., 2010; Kolář et al., 2017).

The factors promoting such niche differentiation remain unclear. In some cases, traits affected by ploidy may interact with the abiotic and biotic environment of the species; in other cases, ploidy-correlated differences may simply reflect non-adaptive processes such as history of spread, dispersal capacity and demographic stochasticity (Baack and Stanton, 2005; Hanzl et al., 2014; Otisková et al., 2014; Kirchheimer et al., 2016; Čertner et al., 2017). In most cases, however, evolutionary history and genetic relationships among the cytotypes remain unknown, leaving open questions as to what extent the divergence reflects the effects of gene doubling per se compared with subsequent genetic divergence (Petit et al., 1999; Kolář et al., 2017). So far, studies focusing on genetically close diploids and autopolyploids provided contrasting results, with either little or no niche differentiation between cytotypes (Hanzl et al., 2014; Simón-Porcar et al., 2017; Šingliarová et al., 2019) or clear separation along climatic gradients (Thompson et al., 2014; Sonnleitner et al., 2015; Zozomová‐Lihová et al., 2015).

The greater colonizing potential of polyploids, or their greater ecological span beyond the limits of their diploid relatives, is one of the classical views that has been recorded for decades (Hanelt, 1966; Löve and Löve, 1967; Brochmann et al., 2004). This assumption was based on the greater occurrence of polyploids towards higher latitude (Brochmann et al., 2004; Rice et al., 2019) or on the invasive success of polyploid over diploid species (te Beest et al., 2012), suggesting pre-adaptation of polyploids to colonize new or harsher environments. Such pre-adaptation is generally attributed to increased genetic variability of polyploids, as a result of polysomic inheritance and masking of mutations in autopolyploids (i.e. polyploids originating from a cross within a single species; Parisod et al., 2010), gene redundancy and heterosis in allopolyploids (i.e. polyploid hybrids; Comai, 2005) or a shift from sexual to asexual reproduction (Comai, 2005; Barringer, 2007). Increased variation may then provide ‘raw material’ for adaptation and/or buffer negative consequences of founder effects during colonization of a novel and challenging environment (Parisod et al., 2010).

The view of polyploids as prominent colonizers of extreme environments was supported by some empirical studies that demonstrated clear niche differentiation between cytotypes. For instance, it was demonstrated that polyploid populations occupied higher elevations and colder environments than diploid populations (Zozomová‐Lihová et al., 2015; Kirchheimer et al., 2016; Knotek and Kolář, 2018). It was also shown that polyploids may have wider ecological niches than their diploid relatives (Lowry and Lester, 2006; Regele et al., 2017) and were more likely to spread invasively in a new environment (Treier et al., 2009; te Beest et al., 2012). However, the general idea that polyploids had greater colonizing ability has been questioned since many studies reported exact opposite patterns, with diploids occurring at higher elevations (Vanderhoeven et al., 2002; Martin and Husband, 2013) or with diploids occupying a wider distribution than polyploid populations (Schönswetter et al., 2007; Sonnleitner et al., 2010). Finally, niche differentiation among cytotypes is not the rule, and some authors reported no relationship between ploidy level and spatial distribution (Gauthier et al., 1998; Raabová et al., 2008; Hanzl et al., 2014).

Here, we explored drivers and consequences of cytotype distribution in a mountain environment, an excellent system for studying ecological differentiation because it is associated with sharp environmental gradients. So far, the available studies usually recorded frequencies of cytotypes along the elevational gradient but did not provide direct comparison of ecological niches or genetic variation of different cytotypes coexisting at the same elevation. To examine further the interaction between ploidy and elevational gradient, we focus on closely related diploids and polyploids that both span the entire range of elevation and investigate both genetic and environmental variation associated with each ploidy. To do so, we study Arabidopsis arenosa whose diploid and autotetraploid (Arnold et al., 2015) populations span an elevation range of approx. 2300 m in one mountain range in central Europe (the Western Carpathians; Kolář et al. 2016a). Although a close relationship between both ploidy cytotypes in the Western Carpathians has recently been confirmed by genome resequencing (lowest intercytotype differentiation in the whole species’ range; Monnahan et al., 2019), detailed relationships among the diploid and tetraploid populations along the elevation gradient remain unknown. In particular, it is unclear whether populations from the highest (alpine) elevations, morphologically distinct from the foothill populations and sometimes treated as a distinct di-tetraploid species (‘Arabidopsis neglecta’; Měsíček and Goliašová, 2002), are more closely related to each other regardless of ploidy or whether alpine habitats have been colonized by each cytotype independently followed by phenotypic convergence.

To test for the consequences of chromosome doubling on genetic diversity, phenotypic variation and habitat preferences, we genotyped multiple natural populations of each ploidy and screened their morphological traits and the biotic and abiotic conditions in which they occur. First, we reconstructed the evolutionary history of both cytotypes in the area using genetic data to provide a baseline for our interpretations. Then we addressed the following specific questions. (1) Did alpine tetraploids originate from their diploid alpine counterparts or are they descendants of the foothill tetraploid populations? (2) Does an increase in ploidy lead to increased genetic diversity, larger morphological variation or different ecological niches? (3) Does the elevation gradient affect the genetic and morphological variation in a different way in each ploidy?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

Arabidopsis arenosa is a perennial and outcrossing plant widely distributed across Europe. While diploids are mainly found in Eastern and Southern Europe in the Balkan Peninsula, polyploids are located in Central and Northern Europe (Schmickl et al., 2012; Kolář et al., 2016b). In this study, we focused on one mountain range in Central Europe, the Western Carpathians, where diploid and tetraploid populations naturally co-occur at different elevations (from approx. 200 to approx. 2300 m asl) (Kolář et al., 2016a). This area is occupied by a single major diploid lineage of A. arenosa (‘W. Carpathian lineage’, Kolář et al., 2016a) and its genetically close tetraploid derivative that had diverged approx. 11 000–30 000 generations ago (Arnold et al., 2015).

Population sampling

Selection of populations

We sampled in total 45 populations distributed along an elevational gradient in the central highest part of the Western Carpathians (Fig. 1; Supplementary data Table S1) aiming to cover all mountain ranges in the area with distinct substrates and geomorphology. As this heliophilous species occurs on ‘islands’ of environmentally suitable conditions (rocky outcrops in lower elevations, rocks and screes in separated glacial cirques in the alpine zone), the population was defined as a set of individuals occurring in a spatially discrete area in a homogeneous vegetation type surrounded by habitats with unsuitable conditions for the species (forests, dense grasslands, arable land, etc.). The species does not colonize anthropogeneous stands within the study area; we thus sampled only populations from natural habitats. Individual plants were sampled in an area not exceeding 500 m in any direction but not closer than 2 m from each other (to avoid collecting siblings). The only exception was one site which was identified to be of mixed ploidy after initial screening but diploid and tetraploid individuals occupy spatially distinct ploidy-pure sections in the lower and upper end of the mountain valley, respectively. Individuals of each ploidy thus have been re-collected at their respective sites and are treated as separate populations (AA170_2 and AA170_4) hereafter.

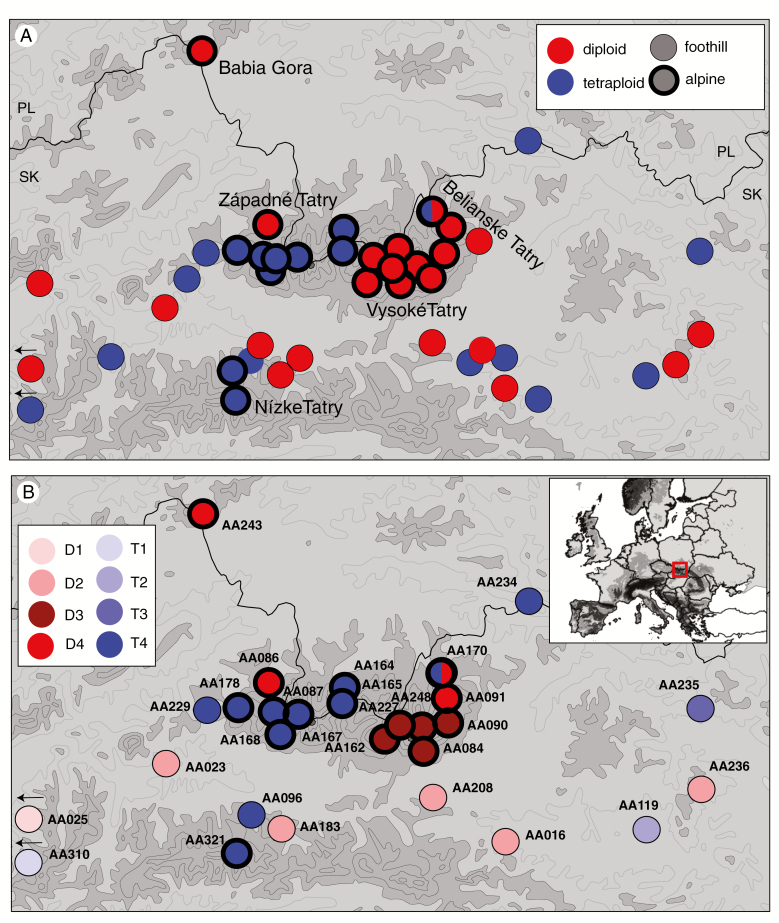

Fig. 1.

Distribution and genetic structure of diploid (red) and tetraploid (blue) A. arenosa populations in the Western Carpathians. Populations from alpine areas above the timberline are highlighted by a thick margin. (A) Ploidy distribution of all populations sampled. (B) Assignment of the 29 genotyped populations into the eight groups (different colours) inferred by K-means clustering that was run separately for each ploidy (diploid, D1–D4; tetraploid, T1–T4). A circle separated into halves denotes a ploidy-mixed population.

Our sampling was designed to cover the entire range of elevations (approx. 200–2300 m asl, except for a distribution gap around the timberline, approx. 1000–1500 m asl, where the species is absent; see also Supplementary data Fig. S1), environments (both acidic and calcareous soils, all types of habitats from rocks and screes to open gravely soils; Supplementary data Table S1) and morphotypes known from the area including the morphologically distinct populations from the alpine areas sometimes treated as ‘A. neglecta’ (Měsíček and Goliašová, 2002). For each population, we sampled on average 20 fresh individuals and determined their ploidy level using flow cytometry as described by Kolář et al. (2016b). For all except five populations (in which the plants were not fully flowering at the time of the visit), we sampled vouchers of the cytotyped individuals for morphological investigations. For 43 populations, we also recorded local environmental parameters (see below). Due to missing values for particular populations, the total set of populations for which both morphological and environmental data are available was 38 (see Supplementary data Table S1 for details). For genetic investigations, we used a sub-set of 29 populations: genome-wide data were available for seven populations from a range-wide A. arenosa study [Monnahan et al. (2019), available from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) code PRJNA484107] and we genotyped an additional 22 populations (3.5 individuals on average; a sub-set of the sampled and cytotyped individuals) using RAD (restriction site-associated DNA) sequencing.

Environmental variables

Local environmental conditions were characterized at each population sampling site by vegetation samples (phytosociological relevés, one per population) covering an area of 3 × 3 m at a microsite with abundant occurrence of A. arenosa. We recorded total vegetation cover (herb layer in %) and listed all accompanying vascular plant species (Supplementary data Table S2). We obtained additional ecological indicators from the absence–presence lists of species by computing Ellenberg indicator values (EIVs) (Ellenberg et al., 1991) using JUICE software (Tichý and Bruelheide, 2002). EIVs provide estimates of environmental characteristics of the sites inferred from species composition based on expert knowledge (Ellenberg et al., 1991). In total, we recorded 378 plant species of which 79 % have EIVs. Among the EIVs, only indices for moisture, nutrients and light were relevant here. We discarded temperature because it was strongly correlated with altitude (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.9), continentality because it is associated with very large geographic gradients and our populations exhibited little variation in continentality values, and soil reaction because soil pH was directly measured in the field. In addition, mixed rhizosphere soil samples were taken from five microsites within the area of the vegetation sample. Soil samples were air-dried, passed through a 2 mm sieve and analysed for pH (after 90 min stabilization of 5 mL of soil in 25 mL of deionized water, the pH was measured by thermo-corrected electrode, WTW Multilab 540, Ionalyzer, pH/mV meter, Germany) in the Analytical laboratory of the Institute of Botany, Průhonice, Czech Republic. In total, we recorded six environmental variables for our populations: elevation, soil pH, herb layer, moisture, nutrients and light.

Phenotypic measurements

For 40 populations, we collected on average 20 plants (range 10–40, n = 774 individuals in total; Supplementary data Tables S1 and S3) at the flowering stage. For each plant, we measured nine phenotypic characters related to flower and leaf morphology likely to vary between ploidy levels (Levin, 2002; Balao et al., 2011): petal length (PL), petal length/petal width ratio (ratio_PL_PW), height of the plant that corresponds to the height of the main stem measured from the rosette to the top of the plant (HP), stem leaf number of lobe pairs (SNLP), rosette leaf number of lobe pairs (RNLP), stem leaf length (SLL), stem leaf length/leaf width ratio (ratio_SLL_SLW), rosette leaf length (RLL) and rosette leaf length/leaf width ratio (ratio_RLL_RLW). Stem leaf was defined as the second leaf from the base; rosette leaf was the largest leaf in the rosette. Missing values in some populations for petal length (PL) (9.17 % of values) and height of the plant (HP) (6.33 % of values) were replaced by population means. For statistical analyses, all the characters, except PL, were log-transformed to approach normal distribution.

Genotyping

Sequencing, raw data processing, variant calling and filtration

We genotyped 2–4 individuals (Supplementary data Table S1) from 22 populations for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) using the double-digest RADseq protocol of Arnold et al. (2015). One methylation-insensitive restriction enzyme (HpyCH4V) was used to generate blunt-end DNA fragments, followed by an A-tailing step combined with ligation of constructed adaptors with T overhang and custom barcodes (Peterson et al., 2012). Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using 125 bp paired-end reads at the EMBL Genomics Core Facility, Heidelberg, Germany.

Raw reads were demultiplexed, quality trimmed (>30 Phred quality score) and mapped using BWA v. 0.7.5a on Arabidopsis lyrata reference v. 1.0.25 (Hu et al., 2011). Post-mapping alignment processing was performed using Picard Tools v. 1.119. The Genome Analysis Tool Kit v3.5 (GATK) (McKenna et al., 2010) was used for realignment around indels (IndelRealigner tool) and for simultaneous SNP discovery and genotyping (HaplotypeCaller and GenotypeGVCFs) following the recommended best practice (www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). Using GATK (VariantFiltration, SelectVariants and CoveredByNSamplesSites), we retained only bi-allelic sites that mapped to nuclear chromosome scaffolds with a minimum mapping quality of 40, which did not show mapping quality bias for the reads supporting the non-reference allele (ensured by keeping only variants with mapping quality rank sum test value higher than –12.5) and which were present in at least 50 % of our individuals at a sequencing depth of 8× or greater. In addition, we excluded potentially paralogous sites by masking genes that showed excess heterozygosity in a set of genome-resequenced populations from throughout the range of A. arenosa (Monnahan et al., 2019). We defined excess heterozygosity for a gene as being heterozygous in five or more individuals in two or more of the 12 diploid populations. We considered it unlikely for the majority of diploid individuals from at least two diploid populations to be heterozygous at five or more sites within a gene according to Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. At the same step, we also masked sites that had excess read depth that we defined as 1.6× the second mode of the read depth distribution (DP >6400) in the same genomic data set (Monnahan et al., 2019). Then we extracted genotypes from sites corresponding to the above called RAD loci from a set of published genome resequencing data (mapped to the same reference and scored in the same way as described above, available at the SRA, code PRJNA484107). To do so, we extracted co-ordinates of the RAD loci, i.e. variant and invariant sites that were called in at least 33 % of individuals in the data set of the RAD-sequenced individuals. Using these co-ordinates, we extracted the same sites from the filtered genome resequencing vcf, combined both vcfs into a single one (CombineVariants) and finally kept only those biallelic SNPs that had coverage of 8× or higher in at least 75 % of individuals (VariantFiltration, CoveredByNSampleSites, SelectVariants). The data set of filtered variants is provided as Supplementary data File S1.

Population genetic analyses

Inference of population diversity and genetic structure

The total data set comprised 130 individuals from 29 populations (4.5 individuals per population on average). We calculated nucleotide diversity (π) and Tajima’s D (Tajima, 1989) for each population with at least four individuals (n = 21, five individuals per population on average) using (1) all individuals genotyped per population and (2) randomly sub-sampled genotypes to contain three individuals per population (genotype count 6 for diploids and 12 for tetraploids) to correct for potential bias caused by unequal population sizes. All these calculations were done using custom python3 scripts (available at https://github.com/mbohutinska/ScanTools_ProtEvol), and the resulting values are provided in Supplementary data Table S4. To estimate interpopulation differentiation in a pairwise manner, we calculated Rho between all population pairs. Rho is an FST analogue suitable for comparing values of population differentiation across ploidy levels (Ronfort, 1999; Meirmans and Van Tienderen, 2013). Finally, we used hierarchical analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) implemented in the R package pegas (Paradis, 2010) to test for genetic differentiation (1) between ploidy levels and among populations within a ploidy level and (2) between elevational groups and among populations within an elevational group. Here, elevation was used as a factor and split the populations into two groups: foothill (from 235 to 990 m) and alpine (from 1472 to 2488 m), reflecting the distribution gap of approx. 500 m, that also corresponds to the timberline.

To infer relationships among the populations, we used several complementary approaches. First, we inferred the grouping of the populations (for each ploidy separately) using non-hierarchical K-means clustering, a non-parametric method with no assumption on ploidy, as implemented in adegenet, using 1000 random starts and further comment on groupings with a sequential increase of K until the partition with the lowest Bayesian information criterion (BIC) value. Secondly, we displayed genetic distances among individuals using principal component analysis (PCA) based on Euclidean distance (replacing the missing values, 1.99 % in total, by average allele frequency for that locus) as implemented in adegenet v1.4-2 (Jombart, 2008). Thirdly, we calculated Nei’s (Nei, 1972) distances among all individuals in StAMPP (Pembleton et al., 2013) and displayed them using the neighbour network algorithm in SplitsTree (Huson and Bryant, 2006).

Finally, we inferred relationships between the alpine tetraploids and other major groups of populations including potential admixture events using allele frequency covariance graphs implemented in TreeMix (Pickrell and Pritchard, 2012). Due to the small sample size of the individual populations, we lumped populations into groups that were defined by the clustering analysis in diploids (D1–D4; see the Results) and eco-spatial position in the target tetraploids (i.e. members of the core cluster T4) separated into foothill and the two spatially distinct alpine groups from Západné and Belianske Tatry Mts. We also ran an additional analysis in which all tetraploids from the T4 cluster were considered as a single group. We used custom python3 scripts (available at https://github.com/mbohutinska/TreeMix_input) to create the input files. We ran TreeMix analysis rooted with the genetically and spatially most distant diploid population, AA025, allowing for two migration events, as the additional migration events did not improve the residual variation. We bootstrapped these scenarios choosing a bootstrap block size of 150 bp (equivalent to RAD loci length) and 100 replicates, and summarized the replicates using the ‘SumTrees.py’ function in DendroPy (Sukumaran and Holder, 2010).

Coalescent simulation

We further addressed the origin of the alpine tetraploids using coalescent simulations implemented in fastsimcoal2 (Excoffier et al., 2013). We compared the fit of simulated tri-dimensional allele frequency spectra (AFS) with empirical spectra calculated from the observed 4-fold degenerate SNPs. To provide accurate estimates of the multidimensional allele frequency spectra, we used genome-wide SNPs from a sub-set of the whole-genome resequenced populations. We constructed joint AFS from population trios iterating individual populations belonging to the same target lineage, in order to minimize the population-specific effects while keeping the still relatively simple three population scenarios. As a first step, we searched whether our alpine tetraploid populations for which resequencing data were available (populations AA168 or AA170_4) are sister to the foothill diploid (D2; pop AA208) or an alpine diploid from either the D3 (AA084) or D4 cluster (AA170_2), with and without accounting for later admixture from the non-sister diploid lineage. Then, we tested for the relationships among the foothill and alpine tetraploids, potentially accounting for gene flow from parapatric diploids. Specifically, we contrasted a scenario of the origin of the alpine tetraploid from (1) the foothill tetraploid (AA119) with and without gene flow from alpine diploids or (2) a separate origin from the genetically closest alpine diploid population potentially followed by admixture from the foothill tetraploids.

For each scenario and population trio, we performed 50 independent fastsimcoal runs to overcome local maxima in the likelihood surface. We then extracted the best likelihood partition for each fastsimcoal run, calculated the Akaike information criteria (AICs) and summarized them across the 50 different runs, over the scenarios and different population trios. The scenario with the lowest mean AIC values within and across particular population trios was preferred. Finally, we used the mutation rate of 7.1e-9 (Exposito-Alonso et al., 2018) to calibrate coalescent simulations and obtain absolute values of population sizes and divergence times.

Statistical analyses

Constrained analysis of principal coordinates (capscale)

We computed a constrained analysis of principal coordinates to determine the amount of genetic variation, based on Nei’s genetic distances, explained by the set of the six environmental variables (elevation, soil pH, nutrients, moisture, light and herb layer). The analysis was based on a sub-set of 24 populations for which both genetic and environmental data were available (Oksanen et al., 2013; package vegan 2.4–6; ‘capscale’ function). Significance of the results was determined by permutation tests (number of iterations = 500, function ‘anova’ in the vegan package).

Generalized linear model analyses

We used linear mixed model (Pinheiro et al., 2012; package nlme 3.1–137, ‘lme’ function) to test for the effect of the six environmental variables and ploidy level on each of the nine phenotypic traits. We ran a distinct model for each phenotypic trait, and all analyses were run at the individual level; we had both phenotypic and environmental data for 696 individuals. Environmental variables (elevation, soil pH, nutrients, moisture, light and herb layer) were all treated as continuous variables, and ploidy level was a factorial variable. Fixed effects were the environmental variables and ploidy level, and the random effect was population.

We also tested for significant differences in environmental properties of the diploid and tetraploid populations (n = 38 in total) using a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) calculated using function ‘manova’ (package stats v3.5.2 in R). We used the six environmental variables (all treated as continuous), elevation, soil pH, nutrients, moisture, light and herb layer, as response and ploidy level as explanatory variable. Finally, we also tested for the effect of elevation and ploidy on genetic diversity of populations with at least four genotyped individuals (n = 21). We tested (1) for the association between nucleotide diversity and Tajima’s D and elevation (as a continuous variable) using a linear model and (2) for the differences in each measure of genetic diversity between populations of different ploidy using Wilcoxon’s rank sum test (functions ‘lm’ and ‘wilcox.test’, respectively, from R package stats v3.5.2).

Classificatory discriminant analysis (CDA)

We applied CDA to determine the percentage of all 774 phenotyped individuals from the 40 populations characterized by their morphology (the nine traits) that were correctly classified into a priori defined groups (ploidy levels). CDA was performed using Morphotools 1.1 (Koutecký, 2015) and the MASS package (Ripley et al., 2013).

Principal component analysis (PCA)

We used this to visualize morphological differentiation of the 40 populations based on the set of nine phenotypic characters (calculated on population means in Morphotools 1.1; Koutecký, 2015).

Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA)

We used CCA to investigate the relationship between the phenotypic and environmental variables at the population level (n = 38). CCA assumes independent variables to reduce multicollinearity issues. Therefore, we computed Pearson correlation coefficients for phenotypic characters (Supplementary data Table S5). We did not find any highly correlated pairs of characters; Pearson correlation coefficients were always below 0.9 (Hair et al., 2006). CCA was based on population means of phenotypic characters and was run on the complete data set and then with the diploid (n = 22) and tetraploid (n = 16) populations separately. We ran a distinct CCA for each of the six environmental proxies used as continuous explanatory variables: elevation, soil pH, nutrients, moisture, light and herb layer. Because the five latter environmental variables were significantly associated with elevation (Supplementary data Fig. S1), we ran the analysis with and without including elevation as a conditioning term (covariable). The significance of each CCA was tested using the ANOVA-like permutation function with 10 000 permutations (Oksanen et al., 2013; package vegan 2.4–6; ‘cca’ and ‘anova.cca’ functions). All analyses were performed in R version 3.4.0 (RStudio Team, 2015).

RESULTS

Ploidy-level distribution

All except one (AA170) A. arenosa populations comprised a single cytotype. Diploid and tetraploid individuals within the population AA170 were spatially distinct and we considered each sub-population as a separate ploidy-uniform unit for all the following analyses. Although populations of both ploidy levels generally span the entire study area and elevational range available (diploids, 480–2488 m; tetraploids, 235–1953 m), there were clear trends in cytotype distribution within the alpine areas. While the largely siliceous Vysoké Tatry Mts. and limestone Belianske Tatry were occupied exclusively by diploids (with the exception of the isolated tetraploid occurrence within the mixed-ploidy population, AA170, in the latter range), the substrate-variable Západné Tatry Mts. were dominated by tetraploids, with the exception of a single diploid population (AA086) (Fig. 1A).

Origin of the alpine populations

For the 130 individuals sequenced, we gathered 36 151 SNPs of average depth 17× (1.99 % missing data). Clustering analysis revealed that diploid populations split into four groups (Figs 1 and 2). Besides a spatially distinct westernmost population (AA025, cluster D1), one group was formed by the foothill populations in the central Western Carpathians (below the timberline, maximum 990 m asl, D2) while two groups occupied alpine habitats (above 1500 m asl) in two ecologically and spatially distinct areas: (1) siliceous Vysoké Tatry Mts. (D3) and (2) calcareous Belianske Tatry Mts. (D4; Fig. 1B). The latter group also encompassed two populations from spatially isolated calcareous outcrops of the Západné Tatry Mts. and Babia Gora Mts. In contrast, the foothill and alpine tetraploid populations were kept together (cluster T4) and only the geographically most distinct foothill populations separated [the western population AA310 (cluster T1) and eastern populations AA119, (cluster T2) and AA235 (cluster T3)]. PCA corroborated this pattern and separated the foothill and alpine diploid groups along the first axis (Fig. 2A). The three spatially distinct foothill tetraploid populations (T1–T3) separated along the second axis, keeping the remaining foothill and alpine tetraploids together.

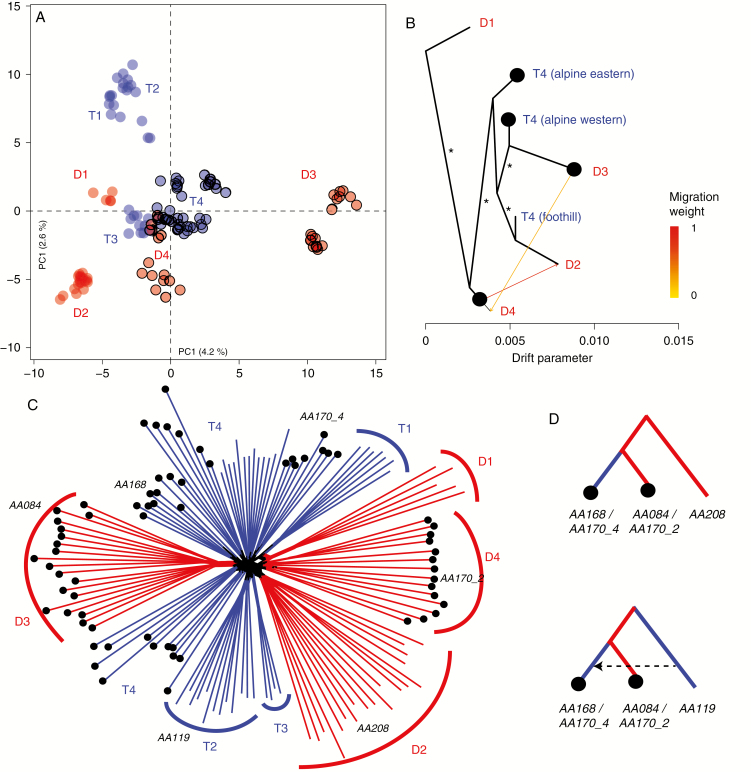

Fig. 2.

Genetic structure of diploid (red) and tetraploid (blue) A. arenosa populations in the Western Carpathians. Populations from alpine areas above the timberline are highlighted by thick margins (A) or black dots (B–D). (A) Principal component analysis of all 130 genotyped accessions based on 36 151 SNPs. (B) Maximum likelihood covariance graph showing relationships among the main spatio-genetic groups allowing for two migration edges denoted by the arrows (* bootstrap support >80 %). (C) Nei’s genetic distances among all individuals visualized by the Neighbor–Joining network. (D) Preferred scenario of the origin of the alpine tetraploid populations (AA168, AA170_4) from their diploid and foothill tetraploid counterparts inferred by coalescent simulations (see Supplementary data Fig. S2). Populations used for coalescent simulations are also highlighted in the Neighbor–Joining network.

The above-described genetic structure indicated that the alpine diploids split into two genetically distinct groups (D3 and D4) that are distinct from their foothill diploid counterparts (cluster D2). Yet, the origin of the alpine tetraploid populations appeared to be more intricate. In the Neighbor–Joining analysis, the majority of the alpine tetraploids (from Západné and Nizke Tatry Mts., termed ‘western alpine tetraploids’) were placed in between the alpine diploids from Vysoké Tatry Mts. (D3) and the foothill tetraploids. The only exception was the single disjunct ‘eastern alpine tetraploid’ population from the Belianske Tatry Mts. (AA170_4×) that was closer to its sympatric alpine diploids (D4; Fig. 2C). The distinct position of the western and eastern alpine tetraploids was corroborated by an allele frequency covariance graph where we displayed the relationships among the four diploid groups and the tetraploids a priori separated into the foothill and the two disjunct alpine groups. Foothill tetraploids and the western alpine tetraploids occupied sister position to the foothill (D2) and D3 alpine diploids, respectively, with a high bootstrap support (Fig. 2B; Supplementary data S2B). Alpine diploids from Belianske Tatry Mts. (D4) and their sympatric eastern alpine tetraploids (population AA170_4) then each occupied sister position to the remaining populations. The two migration edges connected alpine D4 diploids with the other two diploid groups (D2 and D3). When all tetraploids were lumped together, they occupied sister position to the alpine D3 diploids with low support, and this group was sister to the foothill diploids (D2; Supplementary data Fig. S2A).

We thus further tested for the involvement of distinct diploid gene pools and admixtures in the origin of the alpine tetraploids using coalescent simulations. We used a sub-set of genome resequenced populations that provided a sufficient number of approx. 200 000 four-fold-degenerated SNPs. In the first set of simulations, we aimed to infer a diploid sister lineage to each alpine tetraploid population. Here, the scenario of alpine tetraploid as sister to the alpine diploid was consistently preferred (Fig. 2D; Supplementary data Fig. S3); the alpine diploid from the D3 cluster (AA084) was the most likely sister for the western alpine tetraploids (AA168); and the alpine diploid from the D4 cluster (AA170_2) was reconstructed as sister to its sympatric eastern tetraploid population (AA170_4; Supplementary data Fig. S2). In the second set of the simulations, we addressed the relationships between the alpine tetraploids, alpine diploids and foothill tetraploids. In this analysis, the alpine tetraploids consistently occupied sister position to alpine diploids, leaving the foothill tetraploid at the basal position (Fig. 2D; Supplementary data Fig. S4). The scenario assuming later pulse of gene flow from the foothill tetraploid was, however, preferred over that with no migration. Altogether the simulations suggest that the alpine tetraploids originated by admixture between their spatially closer diploid alpine counterparts (either D3 or D4 cluster) and the foothill tetraploids.

Genetic, morphological and ecological differentiation among ploidy levels

Diploid and tetraploid populations harboured very similar levels of genetic diversity, but diploid populations exhibited larger differentiation among themselves than did their tetraploid counterparts, as quantified by pairwise Rho (Table 1). Hierarchical AMOVA showed that ploidy level had not contributed significantly to structuring genetic variation (0.4 % of total variance attributed to ploidy differentiation; Supplementary data Table S6). On the other hand, a significant proportion of genetic variation among the populations was explained by the six environmental variables (capscale analysis, proportion explained: 38 %, df = 6, F = 1.49, P = 0.021).

Table 1.

Genetic variation and differentiation of diploid and tetraploid A. arenosa populations in the Western Carpathians

| Genetic differentiation | Genetic variation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ploidy | No. of pops.* | AMOVA† | Rho‡ | Nucleotide diversity (π)§ | Tajima’s D§ |

| Diploids | 15/9 | 13/23 | 0.14 (0.05) | 0.072 (0.004)/0.072 (0.004) | –0.20 (0.16)/–0.08 (0.05) |

| Tetraploids | 14 /12 | 3/21 | 0.09 (0.05) | 0.072 (0.010)/0.073 (0.006) | –0.35 (0.40)/–0.19 (0.22) |

| Statistical significance | – | – | W = 6776, P < 0.0001 | W = 41, P = 0.38/W = 78, P = 0.10 | W = 46, P = 0.60/W = 96, P = 0.10 |

*Number of genotyped populations (all/with ≥4 individuals).†Among-elevational group (foothill vs. alpine)/among population component (in %).‡Averaged pairwise among-population values with the s.d. in parentheses. The differences between cytotypes were tested by Wilcoxon rank-sum test.§Averages, and s.d. in parentheses, of values for populations with ≥4 individuals calculated using (1) the original number of individuals genotyped or (2) down-sampled to the same number of individuals per population (three), before and after the solidus, respectively. The differences between cytotypes were tested by Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

We tested for the effect of ploidy level on morphology using linear mixed model analysis. None of the nine traits was significantly affected by the ploidy level (Supplementary data Table S7), indicating no clear phenotypic differentiation between the two cytotypes. In line with this, morphological classification of individual plants according to their ploidy level was totally unsuccessful (49 % of the individuals were correctly assigned as diploids or tetraploids based on the nine phenotypic characters), when assuming 50 % as a random classification.

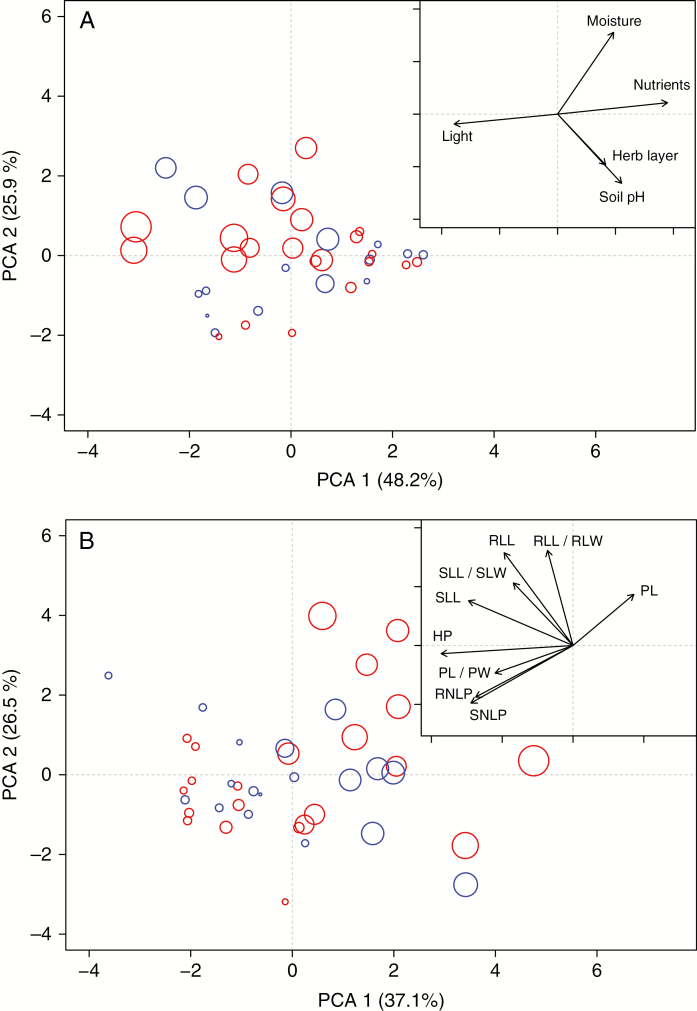

Finally, there was no difference in environmental conditions, as characterized by the six environmental variables, between the sites occupied by diploid and tetraploid populations (PCA, Fig. 3A; MANOVA, Pillai’s trace = 0.28, F-value = 1.98, df = 31, P = 0.098).

Fig. 3.

Environmental and morphological variation of the diploid (red) and tetraploid (blue) populations of A. arenosa. (A) Principal component analysis of five environmental variables (all except elevation) describing conditions at native sites of 38 A. arenosa populations with loadings of environmental traits depicted in the inset. (B) Principal component analysis of the nine phenotypic characters scored on 774 individuals from 40 populations (population means are displayed) with loadings of individual morphological traits depicted in the inset (see Supplementary data Table S10 for an explanation of the abbreviations). Symbol size is proportional to the elevation of the population.

Genetic and morphological differentiation along the elevational gradient in diploids and tetraploids

Sorting the populations according to the elevational group (foothill vs. alpine plants) was significant and accounted for 6 % of the total genetic variance in AMOVA. This differentiation was markedly greater for diploid than for tetraploid populations (13 % vs. 3 % of the total variance explained in AMOVA, respectively; Table 1; Supplementary data Table S8). On the other hand, altitude had no effect on population genetic diversity, regardless of whether the diversity has been calculated based on all genotyped individuals (F = 1.09, P = 0.31 and F = 0.67, P = 0.42 for nucleotide diversity and Tajima’s D, respectively) or on random down-sampling to three individuals (F = 1.72, P = 0.40 and F = 1.02, P = 0.35 for nucleotide diversity and Tajima’s D, respectively).

In regards to morphological differentiation, PCA based on the nine morphological traits revealed that individuals belonging to both cytotypes were fully intermingled and clearly sorted along the elevational gradient represented by the first axis of the ordination (explaining 37 % of variation; Fig. 3B). We thus tested the significance of the relationship between morphological traits and environmental variables using canonical correspondence analysis at a population level (Table 2). Phenotypic characters significantly correlated with elevation (explaining 45 % of the total variance) as well as with each other environmental variable, except for herb layer (Table 2). All the environmental variables were, however, significantly correlated with elevation (r2 from 0.10 to 0.28; Supplementary data Fig. S1). After accounting for the confounding effect of elevation (Table 2), only CCA with soil pH remained significant, and soil pH then explained 5 % of the total variance. We found similar results when the CCA was run with only diploid or tetraploid populations. Elevation explained a large part of the total phenotypic variance (50 % for diploids and 49 % for tetraploids; Supplementary data Table S9). The other environmental variables explained only a small proportion of the phenotypic variance after accounting for the elevational effect. In summary, among our set of environmental variables, the main driver of phenotypic variation was elevation.

Table 2.

Association of phenotypic variation and environmental variables in A. arenosa tested by canonical correspondence analyses (CCAs) separately for each environmental factor alone and when accounting for elevation (in parentheses)

| Elevation | Soil pH | Herb layer | Nutrients | Moisture | Light | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of variance explained (%) | 45.44 | 32.88 (4.66) | 8.14 (0.16) | 9.74 (0.92) | 9.31 (0.46) | 12.87 (1.30) |

| Significance (F-value) | 29.98*** | 17.64*** (3.27*) | 3.19(*) (0.10) | 3.89* (0.60) | 3.70* (0.30) | 5.32* (0.86) |

The table shows the proportion of variance explained and significance based on F-values with (in parentheses) and without accounting for the effect of elevation. The six environmental variables were: elevation, soil pH, total vegetation cover (herb layer), and Ellenberg indicator values for nutrients, moisture and light. Significance is indicated in bold: (*)P < 0.1, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Loading coefficients of the CCA of elevation and the phenotypic characters showed that elevation correlated with similar combinations of traits for diploid and tetraploid populations (Supplementary data Table S10; see Supplementary data Table S11 for the trait values in each group). Elevation correlated particularly with number of lobes on the stem (SNLP) and rosette leaf (RNLP), stem leaf length (SLL), petal length (PL), petal length/width ratio (PL/PW) and stem height (HP). All these characters except PL decreased towards higher elevations, demonstrating that the alpine plants, independently of their ploidy level, were generally smaller, with less divided leaves but with larger petals. These results were consistent with our mixed model analysis that showed a highly significant effect of elevation on these same phenotypic traits (Supplementary data Table S7).

DISCUSSION

Taking advantage of a unique natural set-up of two cytotypes spanning the entire available elevational range in one mountain area, we investigated potential drivers and consequences of ploidy variation along a strong environmental gradient in A. arenosa. First, we address the origin of the alpine populations within each ploidy and demonstrate the complex scenario of colonization and introgression among both cytotypes. Then, by combining morphological and ecological data, we demonstrate that genome duplication has no effect on environmental preferences and/or morphological variation along the elevation gradient in this species.

Origin of the alpine populations

The colonization of alpine stands by A. arenosa was probably a complex multistep process involving parallel upward movement, admixture among distinct genetic groups and/or recurrent polyploidization. At least two distinct diploid lineages colonized the area above the timberline (i.e. above 1500 m asl; Fig. 1B); each of them is now occupying eco-spatially distinct parts of the Tatry mountain ranges (silicate-dominated Vysoké Tatry vs. calcareous Belianske Tatry; Fig. 1). In addition, tetraploid populations colonized two other mountain ranges, substrate-mixed Západné and Nízke Tatry Mts. This spatial aggregation fits well with the phytogeographical distinction of these regions (Futák, 1980) and, together with absence of ecological differentiation between the cytotypes (discussed below), suggests that historical factors were driving the current distribution of cytotypes and genetic lineages. Interestingly, clear divergence of the two alpine diploid groups from their nearby foothill counterparts rules out recent colonization of alpine stands from the extant foothill diploids. An alternative scenario explaining such genetic divergence by rapid recent colonization coupled with a bottleneck is less likely given no decrease of genetic diversity with elevation that would be an expected outcome of a bottleneck (e.g. Tribsch et al., 2002).

In contrast to the clear foothill–alpine divergence in the diploids, alpine tetraploids exhibit close links to multiple genetic lineages. Alpine tetraploids are genetically very close to their foothill tetraploid counterparts (3 % of the total variance explained by foothill–alpine divergence; Table 1), but tree graphs (Fig. 2B) and coalescent simulations (Fig. 2D) show their sister position to the alpine diploids (mostly group D3 with the exception of one tetraploid population, AA170_4, that is closer to its sympatric D4 diploid group). Such a pattern suggests that both foothill tetraploids and alpine diploids have been involved in the origin of the alpine tetraploid populations. This assumption was supported by a significant role for gene flow in their origin that was indicated by coalescent simulations (Fig. 2D). Although the simulations prefer the scenario of independent polyploid origin of the alpine tetraploids from alpine diploids followed by gene flow from foothill tetraploids (as opposed to a split from foothill tetraploids followed by interploidy gene flow), we suggest treating this interpretation with caution. Only a small sub-set of populations was tested, and the genetic similarity of both cytotypes in the area (Arnold et al., 2015) combined with presumably strong gene flow may reduce the power of the analysis in discrimination of the correct topology in a complex reticulate pattern.

Disregarding the particular topology of the reticulation, the admixed origin of alpine tetraploids highlights the interplay between polyploidization and gene flow in colonization of a novel harsh environment. While hybridization is usually the main focus only in allopolyploids (reviewed by Hegarty and Hiscock, 2008; Madlung, 2013), our study highlights that introgression also takes part at shallower evolutionary levels (among divergent intraspecific lineages in autopolyploid complexes) and the introgressed polyploid may colonize challenging high-elevation environments (similarly to the case of alpine tetraploids of Biscutella laevigata; Parisod and Besnard, 2007). Given the current spatial separation of the alpine and foothill populations, it is likely that the admixture happened in cold periods of the Pleistocene when the current alpine stands were glaciated (Lindner et al., 2010; Zasadni and Kłapyta, 2014), and A. arenosa has probably been persisting in the valleys of the Western Carpathians (Kolář et al., 2016a). In such refugia and/or in a sparse woodland landscape that opened up soon after the ice retreat (Jankovska and Pokorný, 2008; Jamrichová et al., 2017), spatial intermingling of populations was possible and could have promoted admixture and/or polyploidization, as has been detected in many other polyploid complexes from European mountains (Ehrendorfer, 1980; Parisod and Besnard, 2007; Winkler et al., 2017; Knotek and Kolář, 2018).

In summary, the alpine ecotype of A. arenosa in the Western Carpathians comprises a complex assemblage of at least three locally distinct genetic lineages and two ploidy cytotypes. Signatures of past gene flow in the origin of alpine tetraploids demonstrate the potential for transfer of potentially beneficial alleles among distinct lineages that might have enabled parallel colonization of the distinct alpine parts of the Tatry mountain range by multiple genetic groups. Determining the identity of the adaptive loci as well as quantifying the role of introgression in adaptation represent a fruitful area for further genome-wide surveys.

Weak niche differentiation between cytotypes

In line with the overall genetic similarity between both cytotypes (0.4 % of total variance explained by ploidy), we did not find evidence for ecological differentiation of one of the ploidy levels of A. arenosa in the studied range, at least based on our set of biotic and abiotic variables. Therefore, our findings contrasted with a body of empirical works that found clear niche differentiation between populations of different ploidy levels. Because genome doubling was often linked to a differential ability to cope with abiotic stress (Levin, 1983), niche differentiation was mainly found along climatic gradients, especially temperature gradients (Parisod et al., 2010) or in relation to water stress (Manzaneda et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 2014). Niche differentiation was also observed along non-climatic variables such as soil properties and vegetation composition in Aster amellus (Raabová et al., 2008) or competition (Hülber et al., 2009). In contrast to these studies, our investigation demonstrates that both diploids and autotetraploids can span a wide range of environmental conditions along the entire elevation gradient.

Our results point rather to a shared ecological niche of both cytotypes. Interestingly, a recent range-wide study of A. arenosa also found an important overlap in the climatic niche of the two cytotypes (based on temperature and precipitation data) but with a slightly different optimum and a greater ecological amplitude of tetraploids (Molina‐Henao and Hopkins, 2019). This range-wide difference, however, probably corresponds to human-mediated northwards expansion of an ecophysiologically (Baduel et al., 2016) and genetically (Arnold et al., 2015; Monnahan et al., 2019) distinct ‘Ruderal’ tetraploid lineage, which is absent in our study area. In contrast, we sampled in the Western Carpathians, the likely ancestral area of the tetraploid A. arenosa cytotype (Arnold et al., 2015). While the tetraploid climatic niche has significantly expanded compared with the diploid niche in the total area (Molina‐Henao and Hopkins, 2019), niche conservatism seems to have been retained in the ancestral area of the polyploid, not only in our sample from the central Western Carpathians, but also across the entire Western Carpathian ploidy contact zone, as was documented by our previous investigations of the climatic niche of A. arenosa in this area (Kolář et al., 2016b). A similar absence of niche differentiation at local scales has also been found in other species in which the diploid cytotype still co-occurs with its immediate polyploid descendant (so-called primary contact zones; Hanzl et al., 2014; Šingliarová et al., 2019).

Distinct genetic structure may further equalize the ecological differentiation of ploidies. A significant overall association of among-population genetic distances with environmental parameters suggests that genetic structure is an important factor of niche differentiation in A. arenosa, rather than ploidy per se. At the difference of the genetically homogeneous tetraploid cytotype, two genetically divergent lineages of diploids occupy ecologically distinct alpine regions (limestone vs. siliceous parts of the Tatry Mts.), thus increasing the overall ecological amplitude of the diploid cytotype. Niche differentiation may be also impeded by gene flow between the two cytotypes, that was mediated by local recurrent origins of the tetraploid followed by admixture among the divergent tetraploid lineages (as suggested by coalescent simulations; Fig. 2D). Indeed, the complex reticulation history of the cytotypes may have slowed down their adaptive divergence. Finally, current spatial separation of ploidy levels at the local scale (only a single ploidy-mixed population was found) does not impose selection pressures for niche displacement in contrast to species with frequently co-occurring cytotypes (Sonnleitner et al., 2015). To summarize, our investigation shows that in species with closely related diploid and autopolyploid populations, niche differentiation may follow the genetic structure of the populations, regardless of their ploidy.

No phenotypic effect of ploidy

Diploid and polyploid populations did not show any sign of differentiation based on the set of morphological traits investigated. This finding is in contrast to numerous experimental studies showing that polyploidy, through genome doubling and extensive changes in genome structure (although the latter is valid mostly for allopolyploids; Chen, 2007), had general effects on nuclear and cell size (Robinson et al., 2018). This translates to variation in some developmental processes and organ size such as rosette size at the time of bolting, leaf area or height of the main stem (Robinson et al., 2018; Corneillie et al., 2019) and in flower morphology and floral phenology (Segraves and Thompson, 1999; Balao et al., 2011), altogether promoting further divergence between ploidy levels (Segraves and Thompson, 1999). However, some internal compensatory mechanisms at a late developmental stage, i.e. reduction of cell number in response to an increase in cell size or earlier maturation of organs in polyploids, may also buffer phenotypic differences between cytotypes (Robinson et al., 2018). Hence, with our sampling design at a particular time point on adult plants, we cannot exclude differences in phenology or in growth rate between diploid and tetraploid populations of A. arenosa.

Instead we found a strong effect of elevation on the phenotype independently of the ploidy level and that the same combination of morphological traits co-varied with elevation in both diploid and tetraploid cytotype. This may suggest that both cytotypes respond in a similar way to their environment. We did not observe stronger phenotypic differentiation with elevation in one ploidy, despite markedly stronger genetic divergence in foothill–alpine diploids than in tetraploids. To what extent this reflects more efficient selection on phenotypic change in polyploids, consequences of introgression among both cytotypes and/or mere effects of phenotypic plasticity remains the subject of further experimental studies.

Conclusions

We demonstrated shared ecological niches and phenotypic similarity among wild diploid and tetraploid A. arenosa populations, despite marked environmental and phenotypic sorting along the approx. 2300 m long elevational gradient. Our results contrast with laboratory studies documenting the effect of experimentally induced ploidy change in the leading plant model genus Arabidopsis (reviewed in del Pozo and Ramirez-Parra, 2015) but add to the recently growing body of evidence that ploidy per se may not necessarily have immediate effects on environmental preferences in nature (Glennon et al., 2014; Hanzl et al., 2014; Šingliarová et al., 2019). A negligible genetic differentiation among both A. arenosa cytotypes in the study area, as an effect of either interploidy reticulation and/or further genetic sub-structure within one ploidy, suggests that the effect of ploidy may be overestimated in systems with genetically divergent ploidy cytotypes that had undergone a long time of independent evolution. Thus, our study argues for the importance of considering genetic structure and historical events when interpreting the patterns of ploidy distributions.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. File S1: vcf file of 36 151 filtered SNPs used in the genetic analyses. Table S1: locality details and environmental parameters of the 45 A. arenosa populations used in the study. Table S2: absence–presence list of accompanying species. Table S3: phenotypic trait values for each individual sampled. Table S4: genetic diversity of A. arenosa populations with at least four individuals genotyped inferred from genome-wide SNP data. Table S5: Pearson correlation coefficients for the set of nine phenotypic characters. Tables S6 and S8: results of the hierarchical analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA). Table S7: results of the linear mixed model. Table S9: canonical correspondence analyses (CCAs) for diploids and tetraploids. Table S10: loading coefficients of the CCA. Table S11: ranges of values of the nine morphological traits. Figure S1: linear regression of the nine environmental variables with elevation. Figure S2: results of TreeMix analysis. Figures S3 and S4: results of the fastsimcoal2 analysis.

FUNDING

This work was funded by the grant agency of Charles University (GAUK 708216 to A.K.) and by the Czech Science Foundation (project 16-10809S to K.M.). Additional support was provided by the Czech Science Foundation (project 17-20357Y to F.K.), Charles University (project Primus/SCI/35 to F.K.) and the Norwegian Research Council (FRIPRO mobility project 262033 to F.K.).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Jana Smatanová, Martin Kolník, Kateřina Knotková, Veronika Vlčková and Eva Kolářová for help with field collections. We thank the Slovak Conservation authorities (no. 2012/536–2892/RD) and Tatransky Park Narodowy authorities (no. DOP3.503/87/15) for collection permits. This study was supported as a long-term research development project no. RVO 67985939. Computational resources were provided by the CESNET LM2015042 and the CERIT Scientific Cloud LM2015085, provided under the programme ‘Projects of Large Research, Development, and Innovations Infrastructures’.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adams KL, Wendel JF. 2005. Polyploidy and genome evolution in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 8: 135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold B, Kim S-T, Bomblies K. 2015. Single geographic origin of a widespread autotetraploid Arabidopsis arenosa lineage followed by interploidy admixture. Molecular Biology and Evolution 32: 1382–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baack EJ, Stanton ML. 2005. Ecological factors influencing tetraploid speciation in snow buttercups (Ranunculus adoneus): niche differentiation and tetraploid establishment. Evolution 59: 1936–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baduel P, Arnold B, Weisman CM, Hunter B, Bomblies K. 2016. Habitat-associated life history and stress-tolerance variation in Arabidopsis arenosa. Plant Physiology 171: 437–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balao F, Herrera J, Talavera S. 2011. Phenotypic consequences of polyploidy and genome size at the microevolutionary scale: a multivariate morphological approach. New Phytologist 192: 256–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barringer BC. 2007. Polyploidy and self-fertilization in flowering plants. American Journal of Botany 94: 1527–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- te Beest M, Le Roux JJ, Richardson DM, et al. 2012. The more the better? The role of polyploidy in facilitating plant invasions. Annals of Botany 109: 19–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochmann C, Brysting AK, Alsos IG, et al. 2004. Polyploidy in arctic plants. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 82: 521–536. [Google Scholar]

- Čertner M, Fenclová E, Kúr P, et al. 2017. Evolutionary dynamics of mixed-ploidy populations in an annual herb: dispersal, local persistence and recurrent origins of polyploids. Annals of Botany 120: 303–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZJ. 2007. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms for gene expression and phenotypic variation in plant polyploids. Annual Review of Plant Biology 58: 377–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comai L. 2005. The advantages and disadvantages of being polyploid. Nature Reviews. Genetics 6: 836–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneillie S, Storme ND, Acker RV, et al. 2019. Polyploidy affects plant growth and alters cell wall composition. Plant Physiology 179: 74–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrendorfer F. 1980. Polyploidy and distribution. In: Lewis WH, ed. Polyploidy. New York: Plenum Press, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ellenberg H, Weber H, Düll R, Wirth V, Werner W, Paulissen D. 1991. Zeigwerte von Pflanzen in MittelEuropa. Scripta Geobotanica 18: 248. [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Dupanloup I, Huerta-Sánchez E, Sousa VC, Foll M. 2013. Robust demographic inference from genomic and SNP data. PLoS Genetics 9: e1003905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exposito-Alonso M, Becker C, Schuenemann VJ, et al. 2018. The rate and potential relevance of new mutations in a colonizing plant lineage. PLoS Genetics 14: e1007155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futák J. 1980. Phytogeographical division of Slovakia (1:1 000 000). In: Mazúr E, ed. Atlas Slovenskej socialistickej republiky. Bratislava: Slovenské pedagogické nakladateľstvo. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier P, Lumaret R, Bédécarrats A. 1998. Genetic variation and gene flow in Alpine diploid and tetraploid populations of Lotus (L. alpinus (D.C.) Schleicher/L. corniculatus L.). I. Insights from morphological and allozyme markers. Heredity 80: 683–693. [Google Scholar]

- Glennon KL, Ritchie ME, Segraves KA. 2014. Evidence for shared broad-scale climatic niches of diploid and polyploid plants. Ecology Letters 17: 574–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair J, Anderson R, Tatham R, Black W. 2006. Multivariate data analysis, 6th edn. Pearson: New Jersey. [Google Scholar]

- Hanelt P. 1966. Polyploidie – frequenz und geographische verbreitung bei höheren pflanzen. Biologische Rundschau 4: 183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hanzl M, Kolář F, Nováková D, Suda J. 2014. Nonadaptive processes governing early stages of polyploid evolution: insights from a primary contact zone of relict serpentine Knautia arvensis (Caprifoliaceae). American Journal of Botany 101: 935–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty MJ, Hiscock SJ. 2008. Genomic clues to the evolutionary success of polyploid plants. Current Biology 18: R435–R444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu TT, Pattyn P, Bakker EG, et al. 2011. The Arabidopsis lyrata genome sequence and the basis of rapid genome size change. Nature Genetics 43: 476–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hülber K, Sonnleitner M, Flatscher R, et al. 2009. Ecological segregation drives fine-scale cytotype distribution of Senecio carniolicus in the Eastern Alps. Preslia 81: 309–319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson DH, Bryant D. 2006. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 23: 254–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamrichová E, Petr L, Jiménez‐Alfaro B, et al. 2017. Pollen-inferred millennial changes in landscape patterns at a major biogeographical interface within Europe. Journal of Biogeography 44: 2386–2397. [Google Scholar]

- Jankovska V, Pokorný P. 2008. Forest vegetation of the last full-glacial period in the Western Carpathians (Slovakia and Czech Republic). Preslia 80: 307–324. [Google Scholar]

- Jombart T. 2008. adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24: 1403–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchheimer B, Schinkel CCF, Dellinger AS, et al. 2016. A matter of scale: apparent niche differentiation of diploid and tetraploid plants may depend on extent and grain of analysis. Journal of Biogeography 43: 716–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knotek A, Kolář F. 2018. Different low-competition island habitats in Central Europe harbour similar levels of genetic diversity in relict populations of Galium pusillum agg. (Rubiaceae). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 125: 491–507. [Google Scholar]

- Kolář F, Fuxová G, Záveská E, et al. 2016. a Northern glacial refugia and altitudinal niche divergence shape genome-wide differentiation in the emerging plant model Arabidopsis arenosa. Molecular Ecology 25: 3929–3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolář F, Lučanová M, Záveská E, et al. 2016. b Ecological segregation does not drive the intricate parapatric distribution of diploid and tetraploid cytotypes of the Arabidopsis arenosa group (Brassicaceae). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 119: 673–688. [Google Scholar]

- Kolář F, Čertner M, Suda J, Schönswetter P, Husband BC. 2017. Mixed-ploidy species: progress and opportunities in polyploid research. Trends in Plant Science 22: 1041–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutecký P. 2015. MorphoTools: a set of R functions for morphometric analysis. Plant Systematics and Evolution 301: 1115–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Levin DA. 1983. Polyploidy and novelty in flowering plants. The American Naturalist 122: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Levin DA. 2002. The role of chromosomal change in plant evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner L, Dzierżek J, Marciniak B, Nitychoruk J. 2010. Outline of Quaternary glaciations in the Tatra Mts.: their development, age and limits. Geological Quarterly 47: 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Löve A, Löve D. 1967. Polyploidy and altitude: Mt. Washington. Biologisches Zentralblatt Suppl: 307–312. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry E, Lester SE. 2006. The biogeography of plant reproduction: potential determinants of species’ range sizes. Journal of Biogeography 33: 1975–1982. [Google Scholar]

- Madlung A. 2013. Polyploidy and its effect on evolutionary success: old questions revisited with new tools. Heredity 110: 99–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzaneda AJ, Rey PJ, Bastida JM, Weiss‐Lehman C, Raskin E, Mitchell‐Olds T. 2012. Environmental aridity is associated with cytotype segregation and polyploidy occurrence in Brachypodium distachyon (Poaceae). New Phytologist 193: 797–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Husband BC. 2013. Adaptation of diploid and tetraploid Chamerion angustifolium to elevation but not local environment. Evolution 67: 1780–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. 2010. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Research 20: 1297–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meirmans PG, Van Tienderen PH. 2013. The effects of inheritance in tetraploids on genetic diversity and population divergence. Heredity 110: 131–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Měsíček J, Goliašová K. 2002. Cardaminopsis (CA Mey.) Hayek. In: Goliašová K, Šípošová H, eds. Flóra Slovenska. Bratislava: Veda, 388–415. [Google Scholar]

- Molina‐Henao YF, Hopkins R. 2019. Autopolyploid lineage shows climatic niche expansion but not divergence in Arabidopsis arenosa. American Journal of Botany 106: 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnahan P, Kolář F, Baduel P, et al. 2019. Pervasive population genomic consequences of genome duplication in Arabidopsis arenosa. Nature Ecology & Evolution 3: 457–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M. 1972. Genetic distance between populations. The American Naturalist 106: 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, et al. 2013. Vegan: community ecology package. R Package Version. 2.0–10. CRAN. [Google Scholar]

- Otisková V, Koutecký T, Kolář F, Koutecký P. 2014. Occurrence and habitat preferences of diploid and tetraploid cytotypes of Centaurea stoebe in the Czech Republic. Preslia 86: 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Otto SP. 2007. The evolutionary consequences of polyploidy. Cell 131: 452–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto SP, Whitton J. 2000. Polyploid incidence and evolution. Annual Review of Genetics 34: 401–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis E. 2010. pegas: an R package for population genetics with an integrated–modular approach. Bioinformatics 26: 419–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisod C, Besnard G. 2007. Glacial in situ survival in the Western Alps and polytopic autopolyploidy in Biscutella laevigata L. (Brassicaceae). Molecular Ecology 16: 2755–2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisod C, Holderegger R, Brochmann C. 2010. Evolutionary consequences of autopolyploidy. New Phytologist 186: 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pembleton LW, Cogan NOI, Forster JW. 2013. StAMPP: an R package for calculation of genetic differentiation and structure of mixed-ploidy level populations. Molecular Ecology Resources 13: 946–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BK, Weber JN, Kay EH, Fisher HS, Hoekstra HE. 2012. Double digest RADseq: an inexpensive method for de novo SNP discovery and genotyping in model and non-model species. PLoS One 7: e37135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit C, Bretagnolle F, Felber F. 1999. Evolutionary consequences of diploid–polyploid hybrid zones in wild species. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 14: 306–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell JK, Pritchard JK. 2012. Inference of population splits and mixtures from genome-wide allele frequency data. PLoS Genetics 8: e1002967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, Team RC. 2012. nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3. [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo JC, Ramirez-Parra E. 2015. Whole genome duplications in plants: an overview from Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany 66: 6991–7003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raabová J, Fischer M, Münzbergová Z. 2008. Niche differentiation between diploid and hexaploid Aster amellus. Oecologia 158: 463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regele D, Grünebach M, Erschbamer B, Schönswetter P. 2017. Do ploidy level, morphology, habitat and genetic relationships in Alpine Vaccinium uliginosum allow for the discrimination of two entities? Preslia 89: 291–308. [Google Scholar]

- Rice A, Šmarda P, Novosolov M, et al. 2019The global biogeography of polyploid plants. Nature Ecology & Evolution 3: 265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripley B, Venables B, Bates DM, et al. 2013. Support functions and datasets for Venables and Ripley’s MASS. Package MASS; http://cran. r-project.org/web/packages/MASS/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DO, Coate JE, Singh A, et al. 2018. Ploidy and size at multiple scales in the Arabidopsis sepal. The Plant Cell 30: 2308–2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronfort J. 1999. The mutation load under tetrasomic inheritance and its consequences for the evolution of the selfing rate in autotetraploid species. Genetics Research 74: 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- R Studio Team 2015. RStudio: integrated development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA, USA: http://www.rstudio.com/. [Google Scholar]

- Schmickl R, Paule J, Klein J, Marhold K, Koch MA. 2012. The evolutionary history of the Arabidopsis arenosa complex: diverse tetraploids mask the Western Carpathian center of species and genetic diversity. PLoS One 7: e42691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönswetter P, Lachmayer M, Lettner C, et al. 2007. Sympatric diploid and hexaploid cytotypes of Senecio carniolicus (Asteraceae) in the Eastern Alps are separated along an altitudinal gradient. Journal of Plant Research 120: 721–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segraves KA, Thompson JN. 1999. Plant polyploidy and pollination: floral traits and insect visits to diploid and tetraploid Heuchera grossulariifolia. Evolution 53: 1114–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simón-Porcar VI, Silva JL, Meeus S, Higgins JD, Vallejo-Marín M. 2017. Recent autopolyploidization in a naturalized population of Mimulus guttatus (Phrymaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 185: 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- Šingliarová B, Zozomová-Lihová J, Mráz P. 2019. Polytopic origin and scale-dependent spatial segregation of cytotypes in primary diploid–autopolyploid contact zones of Pilosella rhodopea (Asteraceae). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 126: 360–379. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnleitner M, Flatscher R, Escobar García P, et al. 2010. Distribution and habitat segregation on different spatial scales among diploid, tetraploid and hexaploid cytotypes of Senecio carniolicus (Asteraceae) in the Eastern Alps. Annals of Botany 106: 967–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnleitner M, Hülber K, Flatscher R, et al. 2015. Ecological differentiation of diploid and polyploid cytotypes of Senecio carniolicus sensu lato (Asteraceae) is stronger in areas of sympatry. Annals of Botany 117: 269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins GL. 1950. Variation and evolution in plants. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sukumaran J, Holder MT. 2010. DendroPy: a Python library for phylogenetic computing. Bioinformatics 26: 1569–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. 1989. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123: 585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson KA, Husband BC, Maherali H. 2014. Climatic niche differences between diploid and tetraploid cytotypes of Chamerion angustifolium (Onagraceae). American Journal of Botany 101: 1868–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tichý L, Bruelheide H. 2002. JUICE, software for vegetation classification. Journal of Vegetation Science 13: 451–453. [Google Scholar]

- Treier UA, Broennimann O, Normand S, et al. 2009. Shift in cytotype frequency and niche space in the invasive plant Centaurea maculosa. Ecology 90: 1366–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribsch A, Schönswetter P, Stuessy TF. 2002. Saponaria pumila (Caryophyllaceae) and the Ice Age in the European Alps. American Journal of Botany 89: 2024–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Peer Y, Mizrachi E, Marchal K. 2017. The evolutionary significance of polyploidy. Nature Reviews. Genetics 18: 411–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderhoeven S, Hardy O, Vekemans X, et al. 2002. A morphometric study of populations of the Centaurea jacea complex (Asteraceae) in Belgium. Plant Biology 4: 403–412. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler M, Escobar García P, Gattringer A, et al. 2017. A novel method to infer the origin of polyploids from Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism data reveals that the alpine polyploid complex of Senecio carniolicus (Asteraceae) evolved mainly via autopolyploidy. Molecular Ecology Resources 17: 877–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zasadni J, Kłapyta P. 2014. The Tatra Mountains during the Last Glacial Maximum. Journal of Maps 10: 440–456. [Google Scholar]

- Zozomová‐Lihová J, Malánová‐Krásná I, Vít P, et al. 2015. Cytotype distribution patterns, ecological differentiation, and genetic structure in a diploid–tetraploid contact zone of Cardamine amara. American Journal of Botany 102: 1380–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.