The number of cases of infection with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) has been increasing and has become a major clinical and public health concern. Production of metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) is one of the principal carbapenem resistance mechanisms in CRE. Therefore, developing MBL inhibitors is a promising strategy to overcome the problems of carbapenem resistance conferred by MBLs.

KEYWORDS: SMB-1, metallo-beta-lactamase inhibitor

ABSTRACT

The number of cases of infection with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) has been increasing and has become a major clinical and public health concern. Production of metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) is one of the principal carbapenem resistance mechanisms in CRE. Therefore, developing MBL inhibitors is a promising strategy to overcome the problems of carbapenem resistance conferred by MBLs. To date, the development and evaluation of MBL inhibitors have focused on subclass B1 MBLs but not on B3 MBLs. In the present study, we searched for B3 MBL (specifically, SMB-1) inhibitors and found thiosalicylic acid (TSA) to be a potent inhibitor of B3 SMB-1 MBL (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50], 0.95 μM). TSA inhibited the purified SMB-1 to a considerable degree but was not active against Escherichia coli cells producing SMB-1, as the meropenem (MEM) MIC for the SMB-1 producer was only slightly reduced with TSA. We then introduced a primary amine to TSA and synthesized 4-amino-2-sulfanylbenzoic acid (ASB), which substantially reduced the MEM MICs for SMB-1 producers. X-ray crystallographic analyses revealed that ASB binds to the two zinc ions, Ser221, and Thr223 at the active site of SMB-1. These are ubiquitously conserved residues across clinically relevant B3 MBLs. ASB also significantly inhibited other B3 MBLs, including AIM-1, LMB-1, and L1. Therefore, the characterization of ASB provides a starting point for the development of optimum B3 MBL inhibitors.

INTRODUCTION

The spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) has become a major clinical concern because of the limited choice of antimicrobial agents for the treatment of infections caused by CRE (1). The production of metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) is one of the strategies used by CREs to acquire carbapenem resistance (2). MBLs are classified into three subclasses, B1, B2, and B3, based on the amino acids that coordinate the zinc ions at the active sites (3).

IMP-1, a B1 MBL, was the first exogenously acquired MBL identified in CRE (4). Most of the recently identified MBLs found to date in CRE, including the NDM type and the VIM type, belong to subclass B1 (5). Our group reported the first emergence of an exogenously acquired subclass B3 MBL, named SMB-1, in Serratia marcescens in 2011 in Japan (6). The genes coding for subclass B3 MBL that have been identified to date had been found specifically in a variety of environmental microorganisms and human-opportunistic pathogens (7–9). Moreover, Lange et al. recently identified a new subclass B3 MBL, LMB-1, in Enterobacter cloacae (10). This indicates that B3 MBLs, as well as B1 MBLs, are now being acquired by clinically relevant Enterobacteriaceae.

Meanwhile, a variety of small-molecule compounds have been identified as MBL inhibitors, most of which occupy the active site of MBLs, where the substrate β-lactams bind (11, 12). These chemical compounds typically contain both thiol and carboxylic acid groups, which are known to play key roles in MBL inhibitors, either by binding to zinc ions or by causing withdrawal of zinc or both, resulting in broad-spectrum MBL inhibition (13, 14).

The studies of MBL inhibitors performed to date have focused on B1 MBLs, probably because the genes of B1 MBLs are more widespread among Enterobacteriaceae at present in clinical settings than the genes of B3 MBLs. However, it is necessary to develop inhibitors for both B1 and B3 subclasses because acquired B3 MBLs, including SMB-1 and LMB-1, have emerged among Enterobacteriaceae isolates as described above. Therefore, in the present study, we tried to develop potent inhibitors of B3 MBLs with a focus on SMB-1 and elucidated its inhibitory mechanism.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In silico screening for SMB-1 inhibitors.

We performed in silico screening with a focus on the compounds containing thiol groups to identify possible SMB-1 inhibitors, as it was previously reported that the thiol group could bind to zinc ions at the active site of various binuclear MBLs regardless of their subclasses (15, 16). We extracted a library of 500 thiol-containing compounds according to the score obtained among 4,200,000 chemical compounds, through structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) in combination with ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS), using the model of SMB-1 in a complex with mercaptoacetic acid (MCR) (PDB ID 3VQZ). We then chose 10 of them that corresponded to commercially available compounds and subjected them to in vitro tests using a spectrophotometric assay with a nitrocefin substrate to measure their inhibitory activity against SMB-1. The results are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Among the tested compounds, 4-fluoro-2-sulfanylbenzoic acid (compound 1, Table S1) was the most effective inhibitor (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50], 0.6 μM). This compound has the typical characteristics of an MBL inhibitor as it contains thiol and carboxylic acid groups on an aromatic ring. A similar molecular constitution is present in captopril and thiomandelic acid, two well-known broad-spectrum MBL inhibitors (13, 17).

Thiosalicylic acid is an effective inhibitor of SMB-1.

4-Fluoro-2-sulfanylbenzoic acid is a derivative of thiosalicylic acid (TSA) (compound 1a, Table S1). Therefore, we investigated the inhibitory effects of TSA on SMB-1 and found that TSA was an effective inhibitor (IC50, 0.2 μM), as was 4-fluoro-2-sulfanylbenzoic acid (Table S1). We hypothesized that the thiol and carboxylic acid groups, which are adjacent on the benzene ring, are the key chemical components exerting the inhibitory effect (Table S1).

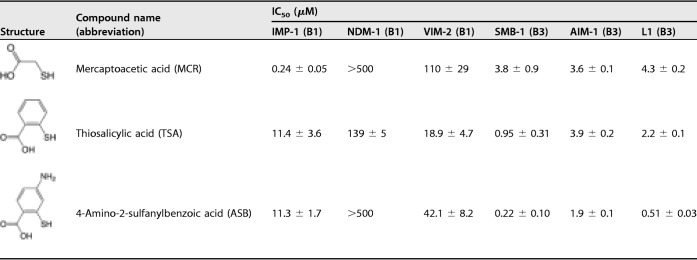

Previously, TSA was found to be a weak inhibitor of B1 MBL BcII (Ki, 237 μM) and showed no or very low inhibitory activity against clinically relevant B1 MBLs (IMP type, NDM type, and VIM type) produced by Gram-negative pathogens (13, 17). Consequently, TSA was considered a noneffective inhibitor for B1 MBLs. However, our results indicate that TSA would be a more effective inhibitor against B3 MBLs than against B1 MBLs. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated the TSA inhibitory effect against various clinically relevant MBLs: IMP-1 (B1), NDM-1 (B1), VIM-2 (B1), AIM-1 (B3), and L1 (B3). The IC50 values of TSA against B1 MBLs ranged between 11.4 and 139 μM while against B3 MBLs they ranged between 0.95 and 3.9 μM (Table 1). Collectively, TSA showed higher inhibitory activity in vitro against B3 MBLs than against B1 MBLs. Our results indicate that TSA has a superior inhibitory effect against B3 MBLs than against B1 MBLs.

TABLE 1.

IC50 values for 6 clinically relevant MBLsa

Measurements were performed using 100 μM imipenem as the substrate.

Inhibitory activity of thiol compounds against live bacterial cells.

The addition of TSA failed to significantly reduce the meropenem (MEM) MICs for the B3 MBL-producing Escherichia coli cells tested in this study, despite showing a high inhibitory effect against the purified enzymes (Table 1; see also Table 2). For example, the reduction of MEM MIC for SMB-1-producing E. coli was limited to 4-fold even under conditions of high concentrations (128 μg/ml) of TSA. Considering that TSA effectively inhibited SMB-1 in vitro (IC50, 0.95 μM) (Table 1), the low inhibitory effect observed in the E. coli cells was probably due to low impermeability of TSA across the outer membrane, a major barrier that disturbs various molecules that enter into the cells.

TABLE 2.

Results of the susceptibility testa

| Strain/plasmid | MBL (subclass) | β-Lactam | Drug MIC (μg/ml)b

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | MCR |

TSA |

ASB |

||||||

| 8 μg/ml | 128 μg/ml | 8 μg/ml | 128 μg/ml | 8 μg/ml | 128 μg/ml | ||||

| E. coli DH5α/pBC-IMP-1 | IMP-1 (B1) | MEM | 1 | 0.25 (4) | 0.03 (32) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.5 (2) |

| E. coli DH5α/pBC-NDM-1 | NDM-1 (B1) | MEM | 32 | 64 (1) | 16 (2) | 32 (1) | 16 (2) | 64 (1) | 8 (4) |

| E. coli DH5α/pBC-VIM-2 | VIM-2 (B1) | CAZ | 16 | 16 (1) | 8 (2) | 16 (1) | 16 (1) | 16 (1) | 8 (2) |

| E. coli DH5α/pCL-SMB-1 | SMB-1 (B3) | MEM | 32 | 16 (2) | 4 (8) | 32 (1) | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | ≤0.25 (≥128) |

| E. coli BL21(DE3)/pET-AIM-1 | AIM-1 (B3) | MEM | 32 | 16 (2) | 1 (32) | 16 (2) | 8 (4) | 16 (2) | 0.5 (64) |

| E. coli DH5α/pBC-LMB-1 | LMB-1 (B3) | MEM | 0.5 | 0.25 (2) | 0.03 (16) | 0.5 (1) | 0.25 (2) | 0.25 (2) | 0.03 (16) |

| E. coli DH5α/pBC-L1 | L1 (B3) | MEM | 4 | 0.5 (8) | 0.03 (128) | 2 (2) | 0.125 (32) | 1 (4) | 0.03 (128) |

MCR, mercaptoacetic acid; TSA, thiosalicylic acid; ASB, 4-amino-2-sulfanylbenzoic acid; MEM, meropenem; CAZ, ceftazidime.

Data in parentheses indicate fold reductions in MICs. The values indicating MICs that were reduced 16-fold or more are shown in bold.

Improvement of inhibitory activity of TSA against live bacterial cells.

TSA showed the desired activity against B3 MBLs, L1, AIM-1, and SMB-1 in vitro, with IC50 values lower than 5 μM, whereas the addition of TSA had little effect on the MEM MIC values for E. coli strains producing B3 MBLs (Table 1; see also Table 2). To overcome this problem, we attempted modifying the chemical structure of TSA to augment its permeability across the bacterial outer membrane, which would result in an improved inhibitory effect on live bacterial cells, and therefore in improved MEM MIC values in the presence of the modified compound.

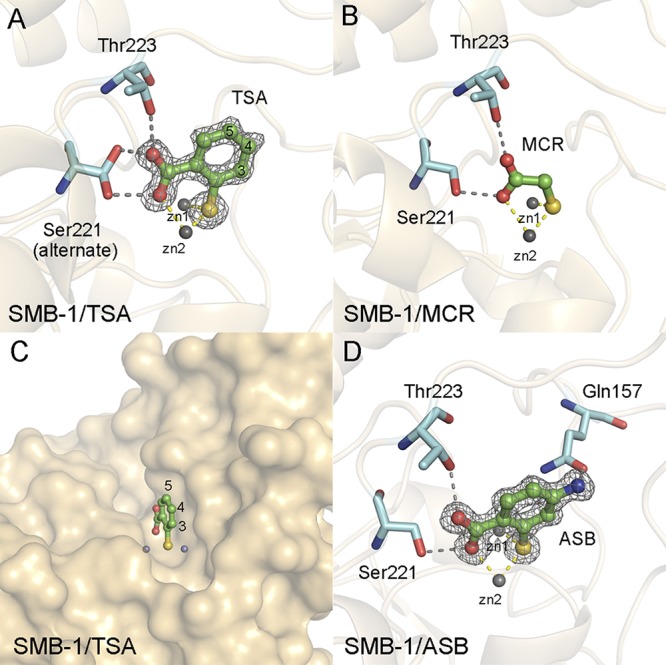

We first determined the structure of SMB-1 in complex with TSA (1.4-Å resolution) to determine the mode of binding between the two molecules (Fig. 1A). The resolved structure shows that TSA binds to two zinc ions, zn1 (2.2 Å) and zn2 (2.3 Å), and to the residues Ser221 (2.4 and 2.7 Å) and Thr223 (2.8 Å), via thiol and carboxylic acid groups (Fig. 1A). The binding mode of TSA is quite similar to that of MCR, a potent inhibitor regardless of the MBL subclass (Table 1), whose structure we have previously determined (Fig. 1B) (18). MCR is a very small compound that contains thiol and carboxylic acid groups similar to TSA and has shown sufficient inhibitory activity even on live bacterial cells (Table 2). MCR binds to B1 MBL IMP-1 through two zinc ions (zn1 and zn2) and Lys224 in IMP-1 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), in addition to binding to B3 MBL.

FIG 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the SMB-1 structure in complex with TSA. A |Fo|-|Fc| omit map of TSA contoured at 3.0 σ (gray mesh) is shown. TSA is depicted using green (carbon), red (oxygen), and yellow (sulfur) sticks. Amino acids Ser221 and Thr223 of SMB-1 are shown as cyan sticks. Zinc ions are illustrated as gray spheres. Gray and yellow dashed lines indicate hydrogen and coordination bonds, respectively. (B) Interactions between SMB-1 and MCR. The color code is the same as that described for panel A. The figure was constructed based on PDB data (PDB ID 3VQZ). (C) Surface representation of the structure of SMB-1 in complex with TSA (shown in ochre). (D) Interactions between SMB-1 and ASB. |Fo|-|Fc| omit maps of ASB contoured at 3.0 σ (gray mesh) are shown. ASB is shown in green sticks. The other molecules follow the color code described for panel A.

The TSA–SMB-1 interaction mode clearly discriminated the important functional groups in TSA, thiol and carboxylic acid, coordinating the zinc ions, which are invariable, as well as the positions that could be modified without lowering the affinity for SMB-1. The C3, C4, and C5 positions of the benzene ring of TSA are more likely to accept modifications without diminishing the affinity for SMB-1, because the upper sides of these carbon atoms are pointing to the solvent and do not interfere with any amino acids at the binding site of SMB-1 (Fig. 1A and C).

Recently, it was revealed that the presence of primary amines (-NH2) is a key factor for enhancing the accumulation of targeted compounds in E. coli cells (19). the presence of 3-aminophenylboronic acid, carrying a primary amine in its benzene ring, restored the MIC values of β-lactams toward KPC-producing and class C β-lactamase-producing Gram-negative pathogens; this was probably, to a certain extent, due to increased permeability across the bacterial outer membrane (20, 21). Therefore, we hypothesized that adding a primary amine to TSA would increase the amount of inhibitor that was taken into the bacterial cells.

We chose the C4 position for modification because 4-fluoro-2-sulfanylbenzoic acid and TSA have similar IC50 values for SMB-1 (Table S1). Therefore, we estimated that the presence of additional atoms at position C4 would not reduce the inhibitory activity of the resulting compound against SMB-1. We then synthesized 4-amino-2-sulfanylbenzoic acid (ASB), by adding a primary amine at position C4 of TSA. ASB showed a slightly improved inhibitory effect (IC50, 0.22 μM) against purified SMB-1 compared to TSA (0.95 μM) (Table 1). We determined the SMB-1 structure in complex with ASB (1.2-Å resolution). The mode of binding between SMB-1 and ASB was the same as that between SMB-1 and TSA (Fig. 1D). Additional hydrogen binding (3.5 Å) between the added primary amine and Gln157 was observed; this might have been the cause of the slightly improved inhibitory effect of ASB compared to TSA. The MEM MIC values for B3 MBL-producing E. coli cells in the presence of ASB became significantly lower than for those found in the presence of TSA (Table 2). When 128 μg/ml ASB was added to the bacterial cells, the MEM MIC for SMB-1 producers was 128-fold or more lower than that of nontreated cells, while the same concentration of TSA caused only a 4-fold reduction in the MEM MICs. ASB also showed improved inhibitory effects on E. coli cells producing AIM-1, LMB-1, and L1. Notably, in the presence of 128 μg/ml ASB, the reduction of MEM MIC values for B1 MBL-producing E. coli cells was limited to 4-fold. Considering the major discrepancy between the ASB IC50 values for B3 and B1 MBLs (Table 1), we classified ASB as an optimum inhibitor of B3 MBLs rather than of B1 MBLs. The selectivity of ASB (or TSA) for B3 MBLs rather than B1 MBLs might simply arise from the key interactions between the carboxylic acid group of ASB (or TSA) and the conserved Ser221/Thr223 (Ser223) residues of B3 MBLs. Since ASB targeted two zinc ions, Ser221, and Thr223 (Ser223), which are highly conserved residues in the clinically relevant B3 MBLs described to date (Fig. S2), ASB should ubiquitously inhibit B3 MBLs that present the previously described molecular characteristics. The specific action of ASB against B3 MBLs may be used to develop detection methods that discriminate B3 from B1 MBL-producing bacteria.

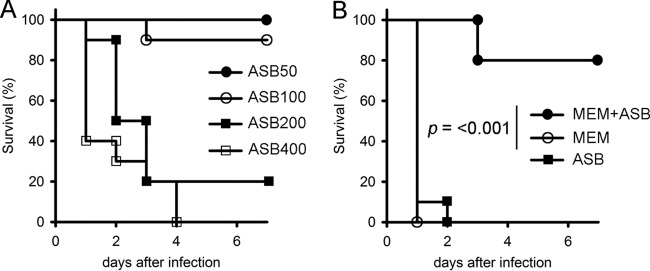

In vivo effect of ASB on mouse survival.

To assess the in vivo effect of the inhibitors studied here, ASB or MEM or a combination of the two chemicals was intraperitoneally injected into mice, together with a lethal dose of SMB-1-producing E. coli strain ATCC 25922. Initially, we used the original SMB-1-producing S. marcescens strain (6), but this strain showed low pathogenicity and failed to cause the death of mice a week after intraperitoneal administration of 108 CFU. Therefore, we used SMB-1-producing E. coli strain ATCC 25922 (MEM MIC = 128 μg/ml, MEM plus ASB [128 μg/ml] MIC = 4 μg/ml) in our in vivo assays.

First, we determined the limiting dose of ASB that could be intraperitoneally injected without lethality (Fig. 2A). Then, when we injected ASB at 100 mg/kg of body weight, the survival rate after 7 days was 90%, indicating that the limiting dose of ASB was close to this value. Injected alone, neither MEM (2.5 mg/kg) nor ASB (100 mg/kg) improved survival, and the mice died within 48 h of infection (Fig. 2B). However, the MEM (2.5 mg/kg)-ASB (100 mg/kg) combination increased survival to 80% at the endpoint, 7 days after infection (Fig. 2B). Effective coadministration of MEM and ASB in mice could translate to in vivo efficacy.

FIG 2.

(A) Mouse survival curves representing the toxicity of ASB (50 to 400 mg/kg). We used 10 mice for each group. (B) Mouse survival curves representing the therapeutic effects of MEM (2.5 mg/kg) or ASB (100 mg/kg) used alone or in combination. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with SMB-1-producing E. coli (E. coli ATCC 25922 carrying pCL-SMB-1) (107 CFU). We used 10 mice for each group. The groups were analyzed using a Mantel-Cox test.

Conclusions.

In contrast to serine β-lactamases, no clinically available MBL inhibitor has been developed thus far, despite the urgent need to overcome carbapenem resistance due to production of MBLs. Although the development of MBL inhibitors has been mainly aimed at clinically relevant B1 MBLs, it would be also necessary to consider B3 MBL inhibitors, because of the recent emergence of exogenously acquired new B3 MBLs. Here, we revealed that the thiol-based small compound ASB was a potent inhibitor against B3 MBLs, SMB-1, AIM-1, and L1. ASB showed a preference for B3 MBLs over B1 MBLs, indicating that ASB could be applied in the differentiation of MBL subclasses. We evaluated ASB with only three acquired B3 MBLs, namely, SMB-1, AIM-1, and LMB-1. Therefore, we need to further assess its action against other B3 MBL-producing clinically relevant isolates. However, our results for the ASB molecule provide a starting point for developing a B3 MBL-specific inhibitor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In silico screening.

The molecular docking of chemical compound libraries targeted for SMB-1 MBL was performed by Kyoto Constella Technologies Co., Ltd. (Kyoto, Japan). In silico screening was performed using myPresto software (22). Initially, a library of approximately 4,200,000 chemical compounds listed in the chemical structure database of Namiki Shoji Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), was prepared for in silico docking simulation. Next, we selected 100,000 compounds based on the results of LBVS using the model of SMB-1 in a complex with MCR (PDB ID 3VQZ). From among these 100,000 compounds, we further selected 15,801 compounds containing a thiol group or hydroxamic acid or carboxylic acid, all of which represent key groups known to exert MBL inhibitory activity. Finally, the 15,801 compounds were subjected to SBVS targeted to the SMB-1 model, which was first optimized via molecular dynamics simulation.

Chemical compounds.

MEM and sodium mercaptoacetate were purchased from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan) (Wako). Ceftazidime (CAZ) and TSA were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). ASB was synthesized by Enamine Ltd. (Kyiv, Ukraine), and its purity was determined by quantitative nuclear magnetic resonance (qNMR) analysis to be over 90%. The other compounds listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material were purchased from Enamine and Tokyo Chemical Industry.

Plasmids.

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S2. The genes for IMP-1, NDM-1, VIM-2, L1, AIM-1, and LMB-1 were amplified with the primers listed in Table S3 and were ligated into the corresponding vectors. The templates of the AIM-1 and LMB-1 genes were artificially synthesized. Plasmid pCL-SMB-1 (6) was introduced into the E. coli ATCC 25922 strain, after which the resulting strain was used for the animal experiments.

Protein expression and purification.

The methodology for expression and purification of SMB-1 was described in a previous study (23). The methodologies for expression and purification of IMP-1, NDM-1, VIM-2, AIM-1, and L1 are described in the supplemental material.

X-ray crystallography.

The native SMB-1 crystals were generated as described previously (23) using the following reservoir solution: 0.2 M lithium sulfate, 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), and 20% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 4000. To obtain the enzyme-inhibitor complexes, 10 mM concentrations of inhibitors (TSA and ASB) dissolved in the reservoir solution were added to drops of solution containing single crystals, and the mixture was incubated for 24 h before collecting diffraction data. The IMP-1–MCR-complexed crystals were obtained by soaking native IMP-1 crystals in a reservoir solution containing 1 mM MCR for 10 min before collecting diffraction data. The native IMP-1 crystals were obtained as follows: 1 μl of 60 mg/ml IMP-1 was mixed with 1 μl of reservoir solution (0.1 M sodium acetate, 0.1 M sodium HEPES buffer [pH 7.5], 25% PEG 3350), and the mixture was incubated at 20°C for crystallization by the sitting vapor-diffusion method. Plate-shaped clusters were obtained. These clustered crystals were manually crushed and subjected to microseeding using 15 mg/ml of IMP-1 solution and the same reservoir solution to obtain single crystals. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the BL2S1 beamline of the Aichi Synchrotron Radiation Center (Aichi, Japan) and beamlines of the Photon Factory (Tsukuba Japan). The data were processed and scaled using iMosfilm/SCALA software (24, 25). Structures were revealed by performing molecular replacement in MOLREP (26). Models were built and refined using Coot and REFMAC5, respectively (27, 28). The data used for structural statistics are summarized in Table S4.

Inhibition assay.

To determine the IC50 values at the screening stage, SMB-1 was preincubated with different concentrations of the thiol compounds at 30°C, after which we measured the hydrolysis of 100 μM nitrocefin in 20 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.5) buffer. To determine the IC50 values of MCR, TSA, and ASB, the enzymes were preincubated with different concentrations of the inhibitors at 30°C for 10 min; we then measured hydrolysis of 100 μM imipenem. We used buffer A (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.5] buffer containing 200 mM NaCl and 50 μg/ml BSA) for the assays with IMP-1, NDM-1, VIM-2, and SMB-1 and used buffer B (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.5] buffer containing 200 mM NaCl, 20 μM ZnSO4, and 50 μg/ml BSA) for the assays with L1 and AIM-1. The enzyme concentration was fixed at 10 nM.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test.

Antimicrobial susceptibility was measured using the microdilution method with 96-well flat-bottom plates according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institutes guidelines (29). bacterial cells (a total of 5 × 105 CFU/ml) were inoculated in 100 μl of Mueller-Hinton (MH) II broth (Becton, Dickinson) containing adjusted an antimicrobial agent, i.e., MEM or CAZ, and inhibitors. The plates were incubated at 35°C for 18 h.

Animal studies.

All experiments were approved by the Nagoya University Animal Ethics Committee and were performed with the aim of minimizing animal suffering. Male CD1 mice (4 weeks old, 20 to 25 g) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, in Japan. The E. coli ATCC 25922/pCL-SMB-1 strain was inoculated on LB agar plates and grown for 18 h at 37°C. Bacteria were scraped from the plates, and the concentrations were adjusted in saline solution containing 5% mucin. The mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 107 CFU. At 1 and 3 h after infection, MEM or ASB or a combination of MEM and ASB was injected i.p. Mice were monitored for 7 days to formulate survival curves and, finally, euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation. Various doses of ASB were injected to assess toxicity.

Data availability.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors of the IMP-1–MCR, SMB-1–TSA, and SMB-1–ASB complexes have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank database under accession numbers 6JED, 6K4T, and 6K4X, respectively.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ayumi Saito and Natsumi Yoshimi for technical assistance. We also thank Hiroyuki Yoshida for providing the SMB-1-producing S. marcescens clinical isolate.

This study was supported by grants from the JSPS KAKENHI (grants JP16K15516 and JP18K08430) and from AMED (grants JP16fk0108122h001 to JP18fk0108022h003).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01197-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gupta N, Limbago BM, Patel JB, Kallen AJ. 2011. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: epidemiology and prevention. Clin Infect Dis 53:60–67. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordmann P, Dortet L, Poirel L. 2012. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: here is the storm! Trends Mol Med 18:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meini MR, Llarrull LI, Vila AJ. 2015. Overcoming differences: the catalytic mechanism of metallo-ß-lactamases. FEBS Lett 589:3419–3432. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osano E, Arakawa Y, Wacharotayankun R, Ohta M, Horii T, Ito H, Yoshimura F, Kato N. 1994. Molecular characterization of an enterobacterial metallo ß-lactamase found in a clinical isolate of Serratia marcescens that shows imipenem resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 38:71–78. doi: 10.1128/AAC.38.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potter RF, D’Souza AW, Dantas G. 2016. The rapid spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Drug Resist Updat 29:30–46. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wachino J, Yoshida H, Yamane K, Suzuki S, Matsui M, Yamagishi T, Tsutsui A, Konda T, Shibayama K, Arakawa Y. 2011. SMB-1, a novel subclass B3 metallo-ß-lactamase, associated with ISCR1 and a class 1 integron, from a carbapenem-resistant Serratia marcescens clinical isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:5143–5149. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05045-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walsh TR, Hall L, Assinder SJ, Nichols WW, Cartwright SJ, MacGowan AP, Bennett PM. 1994. Sequence analysis of the L1 metallo-ß-lactamase from Xanthomonas maltophilia. Biochim Biophys Acta 1218:199–201. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossolini GM, Condemi MA, Pantanella F, Docquier JD, Amicosante G, Thaller MC. 2001. Metallo-ß-lactamase producers in environmental microbiota: new molecular class B enzyme in Janthinobacterium lividum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:837. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.3.837-844.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellais S, Aubert D, Naas T, Nordmann P. 2000. Molecular and biochemical heterogeneity of class B carbapenem-hydrolyzing ß-lactamases in Chryseobacterium meningosepticum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:1878–1886. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.7.1878-1886.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lange F, Pfennigwerth N, Hartl R, Kerschner H, Achleitner D, Gatermann SG, Kaase M. 2018. LMB-1, a novel family of class B3 MBLs from an isolate of Enterobacter cloacae. J Antimicrob Chemother 73:2331–2335. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rotondo CM, Wright GD. 2017. Inhibitors of metallo-ß-lactamases. Curr Opin Microbiol 39:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Docquier JD, Mangani S. 2018. An update on ß-lactamase inhibitor discovery and development. Drug Resist Updat 36:13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tehrani K, Martin NI. 2017. Thiol-containing metallo-ß-lactamase inhibitors resensitize resistant Gram-negative bacteria to meropenem. ACS Infect Dis 3:711–717. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klingler FM, Wichelhaus TA, Frank D, Cuesta-Bernal J, El-Delik J, Muller HF, Sjuts H, Gottig S, Koenigs A, Pos KM, Pogoryelov D, Proschak E. 2015. Approved drugs containing thiols as inhibitors of metallo-ß-lactamases: strategy to combat multidrug-resistant bacteria. J Med Chem 58:3626–3630. doi: 10.1021/jm501844d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lassaux P, Hamel M, Gulea M, DelbrüCk H, Mercuri PS, Horsfall L, Dehareng D, Kupper Ml, Frère Jean-Marie, Hoffmann K, Galleni M, Bebrone C. 2010. Mercaptophosphonate compounds as broad-spectrum inhibitors of the metallo-ß-lactamases. J Med Chem 53:4862–4876. doi: 10.1021/jm100213c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brem J, van Berkel SS, Zollman D, Lee SY, Gileadi O, McHugh PJ, Walsh TR, McDonough MA, Schofield CJ. 2016. Structural basis of metallo-ß-lactamase inhibition by captopril stereoisomers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:142–150. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01335-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mollard C, Moali C, Papamicael C, Damblon C, Vessilier S, Amicosante G, Schofield CJ, Galleni M, Frere JM, Roberts GC. 2001. Thiomandelic acid, a broad spectrum inhibitor of zinc ß-lactamases: kinetic and spectroscopic studies. J Biol Chem 276:45015–45023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107054200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wachino J, Yamaguchi Y, Mori S, Kurosaki H, Arakawa Y, Shibayama K. 2013. Structural insights into the subclass B3 metallo-beta-lactamase SMB-1 and the mode of inhibition by the common metallo-beta-lactamase inhibitor mercaptoacetate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:101–109. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01264-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richter MF, Drown BS, Riley AP, Garcia A, Shirai T, Svec RL, Hergenrother PJ. 2017. Predictive compound accumulation rules yield a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Nature 545:299–304. doi: 10.1038/nature22308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doi Y, Potoski BA, Adams-Haduch JM, Sidjabat HE, Pasculle AW, Paterson DL. 2008. Simple disk-based method for detection of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-type ß-lactamase by use of a boronic acid compound. J Clin Microbiol 46:4083–4086. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01408-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yagi T, Wachino J-i, Kurokawa H, Suzuki S, Yamane K, Doi Y, Shibata N, Kato H, Shibayama K, Arakawa Y. 2005. Practical methods using boronic acid compounds for identification of class C ß-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol 43:2551–2558. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2551-2558.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukunishi Y, Mikami Y, Nakamura H. 2003. The filling potential method: a method for estimating the free energy surface for protein-ligand docking. J Phys Chem B 107:13201–13210. doi: 10.1021/jp035478e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wachino J, Yamaguchi Y, Mori S, Jin W, Kimura K, Kurosaki H, Arakawa Y. 2016. Structural insights into recognition of hydrolyzed carbapenems and inhibitors by subclass B3 metallo-ß-lactamase SMB-1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:4274–4282. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03108-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Battye TG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AG. 2011. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67:271–281. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910048675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans P. 2006. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. 2010. Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:22–25. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. 2010. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murshudov GN, Skubak P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F, Vagin AA. 2011. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67:355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2014. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: twenty-fourth informational supplement, M100-S24. CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The atomic coordinates and structure factors of the IMP-1–MCR, SMB-1–TSA, and SMB-1–ASB complexes have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank database under accession numbers 6JED, 6K4T, and 6K4X, respectively.