Abstract

While neuronal loss has long been considered as the main contributor to age-related cognitive decline, these alterations are currently attributed to gradual synaptic dysfunction driven by calcium dyshomeostasis and alterations in ionotropic/metabotropic receptors. Given the key role of the hippocampus in encoding, storage, and retrieval of memory, the morpho- and electrophysiological alterations that occur in the major synapse of this network-the glutamatergic-deserve special attention. We guide you through the hippocampal anatomy, circuitry, and function in physiological context and focus on alterations in neuronal morphology, calcium dynamics, and plasticity induced by aging and Alzheimer's disease (AD). We provide state-of-the art knowledge on glutamatergic transmission and discuss implications of these novel players for intervention. A link between regular consumption of caffeine—an adenosine receptor blocker—to decreased risk of AD in humans is well established, while the mechanisms responsible have only now been uncovered. We review compelling evidence from humans and animal models that implicate adenosine A2A receptors (A2AR) upsurge as a crucial mediator of age-related synaptic dysfunction. The relevance of this mechanism in patients was very recently demonstrated in the form of a significant association of the A2AR-encoding gene with hippocampal volume (synaptic loss) in mild cognitive impairment and AD. Novel pathways implicate A2AR in the control of mGluR5-dependent NMDAR activation and subsequent Ca2+ dysfunction upon aging. The nature of this receptor makes it particularly suited for long-term therapies, as an alternative for regulating aberrant mGluR5/NMDAR signaling in aging and disease, without disrupting their crucial constitutive activity.

Keywords: aging, adenosine A2A receptor, synaptic plasticity, hippocampus, memory, NMDA receptor, mGluR5 receptor

Introduction

Aging has been widely associated with cognitive decline and synaptic dysfunction and is the main risk factor for Alzheimer's disease (AD). One brain region that is clearly crucial for normal episodic memory is the hippocampus. This medial temporal lobe (MTL) structure has been shown to undergo functional changes over the lifespan. During normal aging, the numbers of primary hippocampal glutamatergic neurons counted stereologically in humans, monkey, or rats do not change significantly (see Morrison and Hof1). If cell numbers are not affected, memory impairment is probably due to the subtle changes known to occur at the synapse that result in altered mechanisms of plasticity.

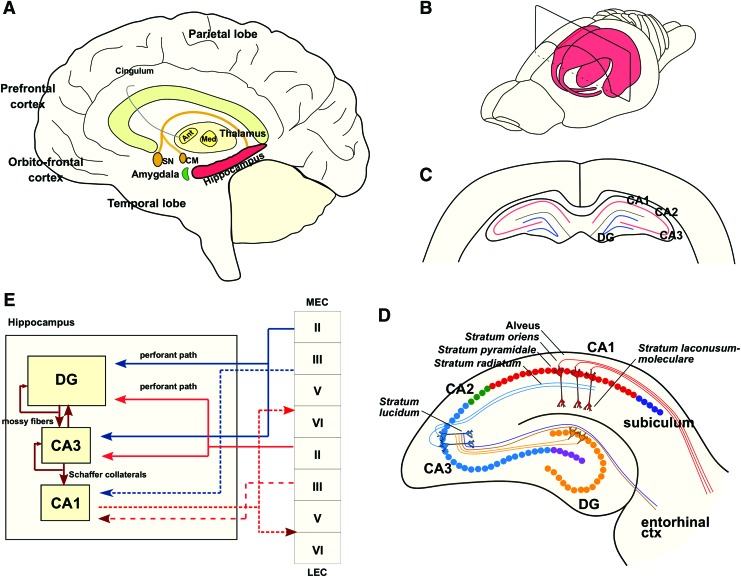

The Hippocampus

The hippocampus is a three-layered structure that is mutually connected to other cortical and subcortical areas (Fig. 1A, B). The trisynaptic pathway from the dentate gyrus (DG) to the CA3 via mossy fibers and onward to CA1 via Schaffer collaterals is the principal feed-forward circuit involved in the process of information through the hippocampus2 (Fig. 1C, D). The hippocampus receives unidirectional input from the entorhinal cortex (EC), where layer II neurons project to DG granule cells via the perforant path2,3 and layer III neurons project to CA1 neurons via the temporoammonic path (perforant path to CA1).2 CA1 pyramidal cells—the major output neurons—project back to deep layers of the EC and to various subcortical and cortical areas via the subicular complex.2

FIG. 1.

Hippocampal anatomy and circuitry. (A) Principal anatomy of the human hippocampal memory systems and the brain regions involved in learning and memory. (B) Schematic rat brain with the hippocampal formation highlighted. (C) Schematic hippocampal slice. (D) Hippocampal slice with different areas and layers. (E) Schematic representation of the hippocampal trisynaptic circuit. First, granule neurons in the hippocampal dentate gyrus receive afferent inputs, via the performant path, from the layer II of the lateral and MEC. Next, granule neurons project to the CA3 pyramidal neurons via mossy fibers and, ultimately, CA1 neurons receive inputs from the CA3 by the Schaffer collaterals, by the contralateral hippocampus through associational/commissural fibers or direct inputs from the performant path. To close the hippocampal synaptic loop, CA1 pyramidal neurons project back to the EC. Ant, anterior thalamic nuclei; CA, cornu ammonis; CM, corpus mammillaris; DG, dentate gyrus; EC, entorhinal cortex; LEC, lateral entorhinal cortex; LPP, lateral performant pathway; MEC, medial entorhinal cortex; Med, medial thalamic nuclei; MPP, medial performant pathway; Mtt, mamillothalamic tract; SN, septal nucleus. Adapted from Lavenex and Amaral.7 Color images are available online.

The DG has three distinct layers (molecular, granular, and polymorphic) and mainly consists of granule cells. The axons of the DG granule cells form the mossy fiber system and project both to the CA3 and back onto granule cells, thus forming a recurrent network.2,4 In addition, the DG receives inputs from the contralateral hippocampus via commissural projections.2,4 Axon collaterals of CA3 pyramidal neurons synapse onto other CA3 neurons, forming a recurrent autoassociative network, whereas CA3 neurons projecting back to the dentate network form a heteroassociative network.2,5 CA1 pyramidal neurons not only receive information which has been preprocessed in the subnetworks of the DG and CA3 but also receive direct projections from the EC, suggesting that the function of the CA1 neurons includes comparing new information from the EC with stored information via CA3 relevant in detection of error, mismatch, and novelty2,6 (Fig. 1E). The crucial role of this redundant feed-forward circuit is crucial for learning and memory and may also underlie its high vulnerability to insults2,7 (Fig. 1E).

Synaptic organization

The integrative properties of neurons depend strongly on the number, proportions, and distribution of excitatory and inhibitory inputs they receive. A single CA1 pyramidal cell has ∼12,000 μm dendrites and receives around 30,000 excitatory and 1,700 inhibitory inputs, of which 40% are concentrated in the perisomatic region and 20% on dendrites in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare.8 The density of dendritic spines and synapses on CA1 pyramidal neurons is highest in the stratum radiatum and stratum oriens.9

Hippocampal neurons mainly release glutamate or gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).9 These neuron types are, most of the times, easily identified due to significant differences in (a)symmetry of synapses, excitatory or inhibitory effect, relative somatic abundance within an area, presence of dendritic spines, and local or projecting nature of the axons.10

The cell bodies of glutamatergic pyramidal neurons are organized in a three-to-five cell-deep laminar arrangement in stratum pyramidale and have orthogonal dendrites from stratum oriens to stratum lacunosum moleculare, thus receiving afferent inputs from several intrinsic and extrinsic sources across well-defined dendritic domains.11 In contrast, inhibitory interneurons (approximately 10–15% of the total cell population), which release the neurotransmitter GABA, have their cell bodies distributed throughout all major strata but they integrate from a more restricted intrinsic and extrinsic afferent input repertoire. However, some interneurons possess axons that cross considerable distances to innervate distinct subcellular compartments or alternatively form long-range projections that extend beyond their original central location to ramify within both cortical and subcortical structures.11

Hippocampal interneurons can be divided into several types: neurogliaform family (32.2%), SOM expressing (9.3%), PV expressing (23.9%), CCK expressing (13.9%), and interneuron-specific (19.4%).11 Despite being the minority, this diverse neuronal population serves as a major determinant of virtually all aspects of neocortical circuit function and regulation.11

The hippocampus receives multiple direct and indirect projections that are crucial to hippocampal function regulation. Dopaminergic projections from both the substantia nigra pars compacta and the ventral tegmental area are important for memory processing.12,13 Also, activation of cholinergic projections activation from the medial septum/diagonal band is sufficient to induce 40-Hz network oscillations in the hippocampus in vitro, thus playing an important role in hippocampal memory processing.14 Serotonergic projections from the median raphe nucleus to the ventral hippocampus have also been consistently described15 and are involved in the retrieval of fear memories.16

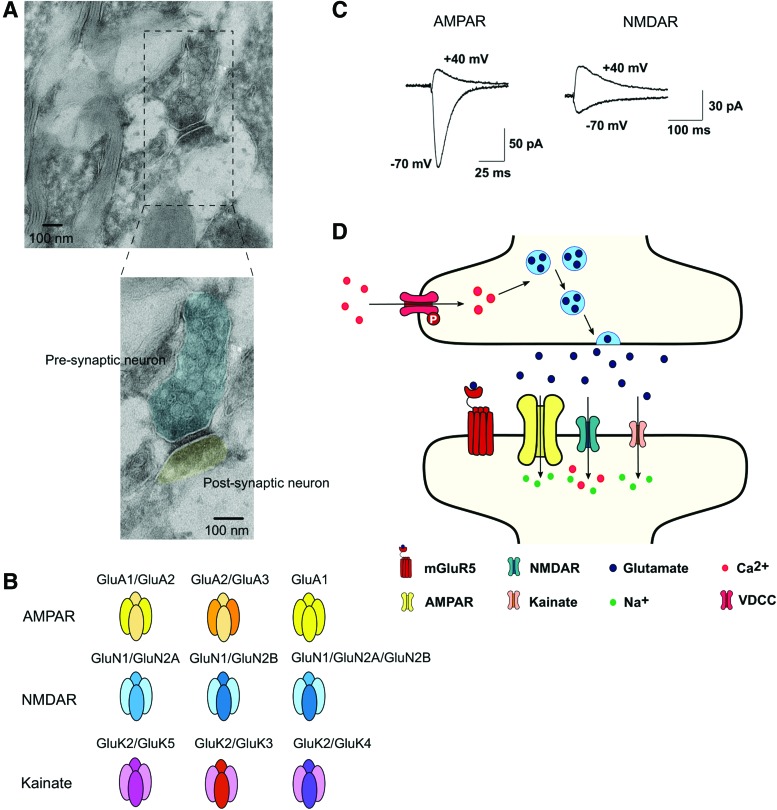

Glutamatergic synapses

Electron microscopy images reveal structural differences between the glutamatergic pre- and postsynaptic components (Fig. 2A). The presynaptic element is easily identified by the presence of neurotransmitter-containing vesicles, generally of relatively uniform size. These vesicles aggregate near a membrane specialization, identified by a more electrodense thickening, reflecting the presence of membrane proteins necessary for exocytosis—“active zone” (Fig. 2A). Among these are proteins that interact with vesicular partners (SNARE proteins), as well as voltage-dependent channels that mediate the influx of Ca2+, which ultimately triggers exocytosis upon an action potential. In addition, mitochondria are frequently present due to the local high energetic demands coupled to transmitter release (transmitter synthesis, vesicular packaging, exocytosis, and reuptake).9,17

FIG. 2.

Glutamatergic pre- and postsynaptic neurons are very distinct structurally and functionally. (A) Electron micrographs of the CA1 area of the hippocampus showing morphological differences between pre- and postsynaptic components. The presynaptic element is easily identified by the presence of neurotransmitter-containing vesicles, generally of relatively uniform size. These vesicles aggregate near a membrane specialization that can be identified as a thickening, reflecting the presence of membrane proteins necessary for exocytosis—“active zone.” On the postsynaptic side, there is also an increased density of the membrane—postsynaptic density, a relatively detergent-resistant structure containing glutamate receptors and associated macromolecules (image kindly provided by Andreia Pinto, IMM JLA). (B) Most abundant subunit composition of ionotropic receptors AMPA, NMDA, and kainate in the hippocampus.18 (C) Representative AMPAR and NMDAR excitatory postsynaptic currents measured in a rat CA1 hippocampal neuron at −70 and +40 mV.100 (D) Schematic diagram of a glutamatergic synapse. Calcium influx through activation of presynaptic VDCC drives docking of the glutamate vesicles to the membrane. Once released, glutamate acts on postsynaptic AMPA (sodium influx), NMDA (sodium and calcium influx), kainate (sodium influx), and metabotropic receptors; adapted from Hassel and Dingledine.18 AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; GluA, AMPA receptor subunit; GluK, kainate receptor subunit; GluN, NMDA receptor subunit; NMDA, N-methyl-d-aspartate; VDCC, voltage-dependent calcium channels. Color images are available online.

On the postsynaptic side, the membrane is more electrodense than the presynaptic membrane (Fig. 2A). This postsynaptic density, or PSD, is a relatively detergent-resistant structure, 50 nm thick, that scaffolds as many as 100 different proteins, among them the glutamate receptors.9,18,19 In inhibitory neurons gephyrin is the equivalent postsynaptic scaffolding molecule.20

Glutamate receptors

Glutamate is packaged into synaptic vesicles in the presynaptic terminals, and released into the synaptic cleft through the docking of synaptic vesicles to the membrane at the active zone. Glutamate then activates postsynaptic glutamate receptors to regulate several neuronal functions, from neuronal migration to excitability and plasticity.18 Glutamate receptors are highly complex transmembrane proteins that can be divided into two main categories: voltage-sensitive ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs; glutamate-gated ion channels) and ligand-sensitive metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs; glutamate-activated G protein-coupled receptors [GPCRs]) (Fig. 2B).

iGluRs mediate the fast excitatory transmission, acting as cation channels that open upon glutamate binding. AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid) receptors are the first iGluRs activated, leading to sodium influx and consequently postsynaptic membrane depolarization (Fig. 2B–D). Following the initial AMPAR-mediated depolarization, NMDA (N-methyl-d-aspartate) receptors become activated due to removal of the voltage-dependent physical occlusion by magnesium of the channel pore and are permeable to sodium and calcium ions (Fig. 2B–D).18 Kainate receptors also mediate synaptic transmission, at a smaller extent, through the entry of sodium and calcium (Fig. 2B–D). Generally, AMPA receptors mediate fast (<10 mseconds) synaptic transmission, while NMDA and kainate receptors mediate slow (10–100 mseconds) synaptic transmission.18

In addition, mGluRs activation also modulates neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission. mGluRs are slower players since they exert their effects through recruitment of second messenger systems, gene expression, and protein synthesis. Eight mGluR subtypes (mGluR1-8) are differentially expressed in specific regions in the central nervous system (CNS), being divided into three subgroups based on sequence homology, G protein-coupling, and ligand selectivity (Fig. 2D).18 Group I mGluRs (mGluR1 and 5) are widely expressed postsynaptically, being preferentially associated with Gq/Gs.18 Group I mGluRs trigger the activation of phospholipase C (PLC), which then leads to calcium mobilization from endoplasmic reticulum and protein kinase C (PKC) activation.18 Glutamatergic soma and synapses can be labeled by a wide variety of markers listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Glutamatergic Synaptic Markers, Localization, and Role

| Marker | Localization | Role |

|---|---|---|

| AMPAR GluA1 | PSD | AMPA receptor R1 subunit |

| CaMKII | Neuronal soma | Protein kinase regulated by the Ca2+/calmodulin complex; involved in Ca2+ homeostasis and in learning and memory processes32 |

| Glutaminase | Neuronal soma | Enzyme that generates glutamate from glutamine18 |

| Astrocytes | ||

| Glutamine synthase | Astrocytes | Enzyme that catalyzes the condensation of ammonia and glutamate to form glutamine18 |

| NMDAR | PSD | NMDA receptor N1 subunit |

| GluN1 | ||

| PSD95 | PSD | Fibrous specialization of the submembrane cytoskeleton that adheres to the postsynaptic membrane; regulation of adhesion, control of receptor clustering, and regulation of receptor function9,18,19 |

| vGluT | Pre-synaptic neuron | Transports cytoplasmic glutamate into vesicles35 |

AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; CaMKII, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II; NMDA, N-methyl-d-aspartate; PSD, postsynaptic density; vGluT, glutamate vesicular transporter.

Synaptic plasticity

Synaptic plasticity can be defined as activity-dependent modifications in the efficacy and strength of synaptic transmission of preexisting synapses.21 Long-term synaptic plasticity can last from minutes to several days and even years.22–24 These synaptic plasticity processes have long been correlated with memory performance and are proposed to be a main neurophysiological correlate of memory.21,25

Hebbian plasticity

The Schaffer collaterals-CA1 synapse is undoubtedly the most well-characterized and well-studied glutamatergic synapse of the hippocampus. In the last decades, many in vitro electrophysiological studies have described the events underlying long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) phenomena. These mechanisms, found and studied in animal models, have also been described in humans.26 Importantly, blockade of proteins involved in either LTP or LTD mechanisms disrupts learning.27–30

The most extensively studied and characterized forms of synaptic plasticity are the LTP and LTD in the Schaffer collaterals-CA1 region of the hippocampus. LTP is defined as the long-lasting enhancement in synaptic transmission between two neurons following a continuous and strong stimulation (high-frequency stimulation or theta-burst stimulation), while LTD reflects a long-lasting decrease in the efficiency of synaptic transmission following a continuous weak stimulation (LFS: low-frequency stimulation).

Postsynaptically, LTP and LTD processes begin with a depolarization of the membrane due to Na+ influx through AMPAR activation, which releases the Mg2+ block from NMDAR. Although both forms require AMPAR and NMDAR activation, it is the spatiotemporal nature of the intracellular Ca2+ rise that dramatically impacts the direction of plasticity.31 The huge increase in Ca2+ influx elicited by strong activation of NMDAR activates calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), a key component of the molecular machinery for LTP, since LTP induction was prevented in knockout (KO) mice lacking a critical CaMKII subunit.32 The modest increase in Ca2+ influx observed upon weak stimulation instead drives activation of phosphatases, such as protein phosphatase 1 and 2.33 Thus, the probability of a given synapse to undergo LTP or LTD is a function of kinases versus phosphatases activation. Consequently, in LTP or LTD AMPAR phosphorylation can be regulated bidirectionally, with LTP increasing phosphorylation and LTD decreasing phosphorylation.34–37

Homeostatic plasticity

Most studies of long-term changes in synaptic strength have focused on Hebbian mechanisms, where these changes occur in a synapse-specific manner. Although Hebbian mechanisms are necessary for modulating neuronal circuitry selectively, they might not be sufficient since they tend to destabilize the activity of neuronal networks. An increase in synaptic strengths, such as in LTP, would increase the excitatory drive on to a postsynaptic cell, making it more likely to fire. This in turn would increase the likelihood of more LTP; thus positive feedback would quickly saturate the system, resulting in a hyperactive state with saturated synaptic inputs. Conversely, excessive LTD would also proliferate, resulting in a silent state with inputs fully depressed.38

Homeostatic plasticity acts as a compensatory stabilizing mechanism that, using a negative feedback system, keeps the activity of the network within a dynamic range.39,40 Several forms of homeostatic plasticity have been identified and include mechanisms that regulate neuronal excitability, stabilize total synaptic strength, and influence the rate and extent of synapse formation.41 These forms of homeostatic plasticity are likely to complement Hebbian mechanisms to allow the modification of neuronal networks selectively.41 In essence, the whole synaptic population is equally affected, such that the overall sum of synaptic strengthening and therefore activity of a neuron is changed but the relative weighed differences between synapses is preserved: the computational and storage capacity of the network is not compromised and homeostatic plasticity will not be in conflict with or erase the information set by Hebbian plasticity.41

The Aged Glutamatergic Synapse

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), by 2020, the number of people aged 60 years and older will outnumber children younger than 5 years. Moreover, between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world's population over 60 years will nearly double from 12% to 22%. Aging is, in fact, the main risk factor for AD.42 These profound demographic changes have placed “the aging process” as one of the big challenges for scientific research nowadays. Although aging affects the entire body, its impact on brain and cognition has a profound effect on quality of life of the individuals. Much work has been focused on the hippocampus, as age-related decline in performance dependent on this region is consistently found across species and tasks.43–48

These age-related memory impairments can be explained, in part, by changes in neural plasticity or cellular alterations that directly affect mechanisms of plasticity.49 Although several age-related neurological changes have been identified during normal aging, these tend to be subtle compared with the ones observed in age-associated disorders, such as AD and Parkinson's disease (PD).49 Consequently, understanding age-related changes in cognition sets a background against which it is possible to assess the effects of the disease.49

For a long time, aging had been associated with neuronal loss independently of the brain region.50–53 However, the methods used in those studies question the accuracy of such results1,49 and subsequent studies have conclusively shown that the cell number is preserved in aging in several brain areas, including the hippocampus.54–59 These data highlight the differences between normal aging, characterized by structural preservation in the MTL, versus AD, which is associated with neuronal and synaptic loss in the MTL and in the hippocampus in particular.60

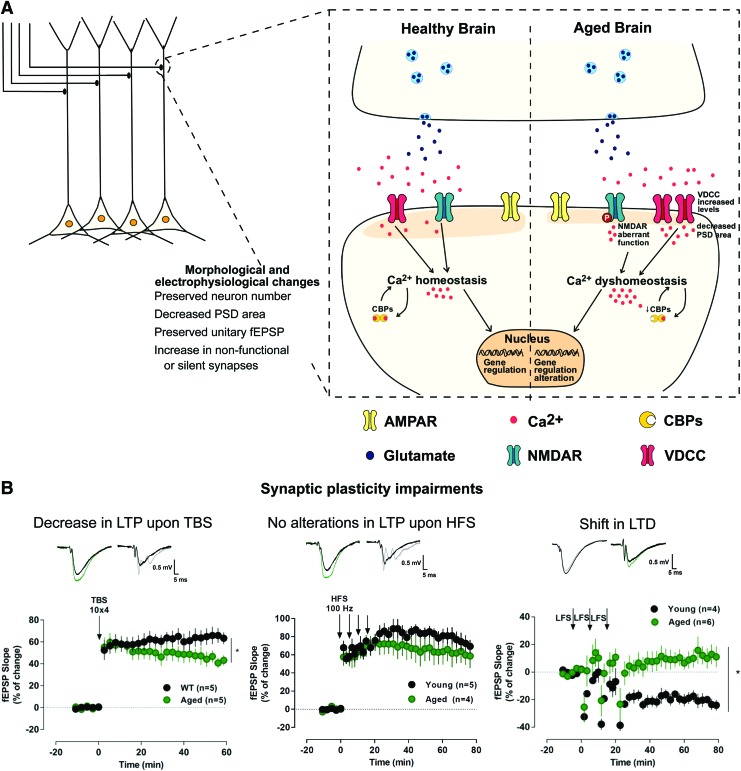

Although the total number of Schaffer collaterals-CA1 synapses is preserved across different age groups,61 the amplitude of the Schaffer collaterals-induced field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSP) recorded in CA1 is reduced in aged memory-impaired animals.62–64 Furthermore, the PSD area of axospinous synapses is significantly reduced in aged learning-impaired rats65 (Fig. 3A). However, at the CA3-CA1 synapse, the size of the unitary EPSP remains constant during aging66 (Fig. 3A). Together, these data suggest that aging might not be associated with alterations in the strength of individual synaptic connections but instead with an increase in nonfunctional or silent synapses in the hippocampus49,67 (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Morphological and synaptic alterations upon aging in the CA1 area of the hippocampus. (A) Morphological and electrophysiological impairments observed upon aging in CA1; increased VDCC and aberrant NMDA receptor function impair calcium homeostasis, further enhanced by a decrease in activity of calcium buffering proteins, driving alterations in gene regulation. (B) Examples of LTP and LTD time courses upon different stimulation protocols (TBS: 10 trains with 4 pulses at 100 Hz, separated by 200 mseconds; HFS: 4 trains of 100 pulses at 100 Hz, separated by 5 minutes; low-frequency stimulation: 3 trains of 1200 pulses at 2 Hz, separated by 10 minutes); representative traces of fEPSPs before (black) and 50–60 minutes after (gray, green) LTD or LTP induction in young and aged rats.100 *p < 0.05. CBPs, calcium-binding proteins; fEPSPs, field excitatory postsynaptic potentials; HFS, high-frequency stimulation; LFS, low-frequency stimulation; LTD, long-term depression; LTP, long-term potentiation; TBS, theta-burst stimulation. Color images are available online.

Recently, transcriptomic analysis of the human aged brain revealed robust negative associations of genes encoding pre- and postsynaptic proteins with age, likely related to functional changes in synaptic integrity seen with aging (for a complete review see Burke and Barnes49,67). Interestingly, these changes occur across inhibitory and excitatory synapses and some of the strongest effects were observed in the hippocampus, consistent with the increased vulnerability of this structure to the aging process.68

Alterations in glutamate metabolism have also been described upon aging. In the hippocampus of mice and rats, the glutamate content in tissue samples decreases at 24–29 months,69–71 which may explain age-related changes in hippocampal neuron function during aging. However, basal extracellular concentrations of glutamate in aged rodents were reported to be either greater or lower, providing contradictory results,71,72 and glutamate uptake, which terminates its action in the synapse, does not seem to be altered in aging.73–75 These results are difficult to reconcile, but this may be due to the fact that the concentration of glutamate sampled in most of these studies results from the release and uptake processes. Also, since most of these techniques cannot differentiate between neuronal and glial sources, the cellular origin of the glutamate released is still uncertain.76 In addition, age-related decreases in presynaptic release of glutamate may be compensated by changes in uptake and may also reflect alterations in the density of postsynaptic glutamate receptors.

In rodents, one of the well-characterized markers of physiological aging is an age-related decrease in action potential firing rates of CA1 pyramidal cells, with a concomitant decrease in the amplitude of the postburst after hyperpolarization responsible for spike frequency adaptation,77 reviewed by Wu et al.78 Besides intrinsic properties, the excitatory synaptic transmission is altered during aging, being mainly studied in the hippocampus of old rats, and/or cortex of primates.78

Such alterations observed at individual synapses have a significant impact on synaptic plasticity. Age-associated memory deficits correlate with impairments in either LTP or LTD.28,79 In aged animals, LTP has been found to be reduced43,80–82 (Fig. 3B), not altered81,83–87 (Fig. 3B) or even strengthened.83,88–91 The latter is inconsistent with the classical correlation between increased LTP magnitude and better performance on hippocampal-dependent memory tasks. Differences in the synaptic circuit that is being potentiated81 or in the stimulation protocol49,83 may account for the observed discrepancies in LTP magnitude. Generally, age-associated alterations in LTP are only observed when weaker stimulus protocols are used, resulting in either an increase83,88,89,91 or in a decrease79 of LTP (Fig. 3B).

Given the key role of AMPAR in LTP and LTD, synaptic plasticity alterations observed upon aging may be related with alterations in AMPAR expression and function, although very few studies have addressed that. Administration of AMPAR positive allosteric modulators restores age-related memory and synaptic potentiation deficits,92,93 suggesting an increase in silent AMPAR rather than alterations in the expression of synaptic AMPAR.94

The transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) has been shown to have fundamental roles in cognition and cellular excitability.95,96 The first study that identified an age-related CREB signaling dysfunction showed a reduction in LTP and performance in Barnes test that was ameliorated upon treatment with compounds that activate the cAMP/PKA pathway, possibly by increasing CREB activity.97 Levels of phosphorylated CREB (pCREB) are decreased in aged versus young animals after training in the Morris water maze, and strongly correlated with individual learning performance, whereas CREB expression itself does not change.98 These results suggest that alterations in activation rather than expression contribute to the age-related changes in cognition.

Some authors report increased susceptibility to LTD during aging,87 whereas others fail to observe alterations in LTD magnitude in aged animals.84,99 These discrepancies can be explained by differences in animal strain, stimulation pattern, or Ca2+/Mg2+ ratio. Accordingly, paired-pulse LFS (PP-LFS) does not induce changes in LTD between young and aged animals,99 suggesting that different mechanisms may be involved in the induction of LTD by LFS and PP-LFS. Also, age-related differences in LTD induction could be rescued by manipulating the extracellular Ca2+/Mg2+ ratio. Indeed, the fact that induction of LTD is both a function of age and the levels of Ca2+ in the recording medium, strongly support an age-related Ca2+ dysregulation, and a shift in Ca2+-dependent induction mechanisms rather than in the LTD intrinsic capacity.84,99 Data produced by our group are consistent with this hypothesis, since we showed that aging is associated with a shift in the form of plasticity induced by a weak stimulus (LFS elicited LTP instead of LTD), as a consequence of increased NMDAR activation and Ca2+ influx100 (Fig. 3B).

It has been hypothesized that postsynaptic intracellular levels of Ca2+ are involved in setting a synaptic modification curve, which determines the probability that a synapse will be depressed or potentiated for a given pattern of input.61,101 Accordingly, since Ca2+ homeostasis is disrupted in aged animals (discussed further below),102,103 we can expect alterations in the probability for a given synapse to undergo potentiation or depression. All these observations support the calcium hypothesis of aging, which implicates raised intracellular Ca2+ as the major source of functional impairment and degeneration in aged neurons.104–106

To avoid excessive intracellular levels of calcium ([Ca2+]i) elevations, neurons are equipped with complex machinery that permanently modulates the temporal and spatial patterns of Ca2+ signaling.107,108 Brief elevations of [Ca2+]i are essential in controlling membrane excitability and modulating synaptic plasticity mechanisms, gene transcription, and other major cellular functions.107,108 However, long-lasting elevation of [Ca2+]i triggers neurotoxic signaling pathways that ultimately will drive cell death.107,108

Several studies reported an age-associated increase in basal [Ca2+]i levels109,110 as a result of increased voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx,103,111,112 aberrant buffering113–115 (Fig. 3A), extrusion,110,116–118 and uptake capacity.119 Furthermore, given the key role of NMDAR in synaptic plasticity and memory,120 putative alterations in NMDAR may also account for Ca2+ dysregulation.

In aged CA1 pyramidal neurons, there is an increased duration of NMDAR-mediated responses.121 Consistent with this hypothesis, aged animals display an NMDAR overactivation upon glutamate or glycine stimulation, despite a decrease in the density of these receptors122 (Fig. 3A). However, such alteration in NMDAR-mediated responses may be due to the previously described increase in nonfunctional synapses with aging. The fact that there is an increased binding of the NMDAR antagonist MK-801 in animals with learning and retention deficits123,124 suggest that an increase in NMDAR channel open-time happens as a compensatory mechanism for the apparent decrease in receptor number,125 since MK-801 only binds open channels.

The age-associated synaptic dysfunction can also be a consequence of alterations in astrocytes and microglia, as the aging process has also been described as inflammaging, a status of chronic inflammation that contributes to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases.126 Although the number of astrocytes remains unaffected127–129 in aged humans, in rats there seems to be an increase in the astrocytic size, described in the hippocampus.129 In mice, age decreases the expression of ionotropic and purinergic receptors130 and neurotransmitter-induced Ca2+ signaling.131 Importantly, age is also associated with reduced expression of water channels (aquaporins 4) in astroglial perivascular processes and markedly diminished clearance of the brain parenchyma through the glymphatic pathway,132 a key process in the prevention of the accumulation of misfolded protein aggregates.

Microglia alterations upon aging have also been described in several species. Age-dependent microglia activation was found in aged rodents, nonhuman primates, and humans,133–135 characterized by increased expression of MHCII, CD68, TLRs, and proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and IL-6.136–140 However, other studies unravel a microglial dystrophic/senescent phenotype in aged individuals,141,142 thus supporting the hypothesis that, rather than induction of microglial activation, progressive microglial degeneration and loss of microglial neuroprotection are associated with aging and further contribute to the onset and progression of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD.

The Modulation of Aged Synapse by Adenosine A2A Receptors

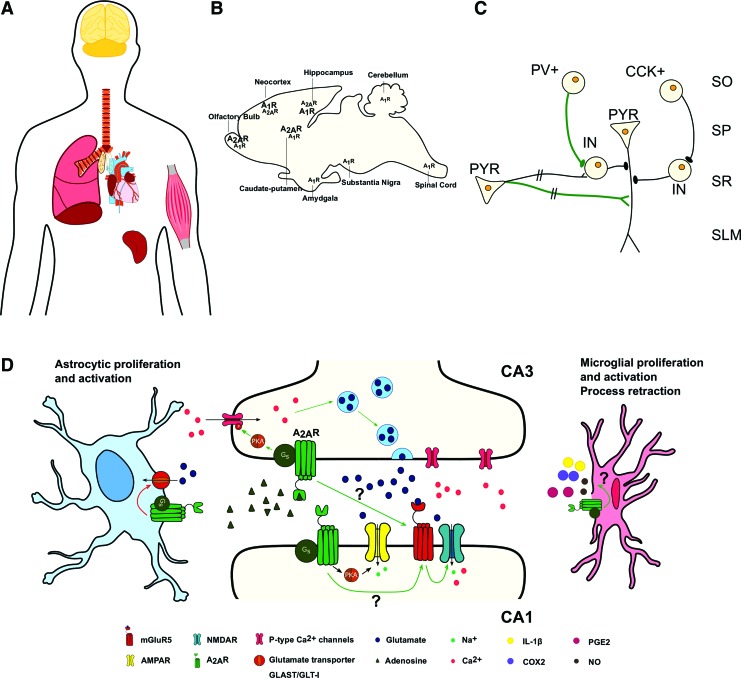

Adenosine influences many functions in the CNS. Besides the neuromodulatory actions, adenosine acts as a fine-tuner of synaptic communication, as it is a relevant player in neuron–glia communication and can affect the release and action of many neurotransmitters and other neuromodulators.143–147 Accordingly, the neuromodulatory role of adenosine is mediated by a balance between the inhibitory and excitatory actions via A1R (usually coupled to adenylate cyclase inhibitory proteins, Gi/Go) and A2A receptors (A2AR; coupled to adenylate cyclase inhibitory proteins Gs), the most relevant adenosine receptors in the CNS.148 The effects of adenosine depend on the receptors expression pattern and signaling, the brain region, and pathophysiological condition. A1R are widely distributed, being more abundant in the cortex, cerebellum, and hippocampus.149 On the opposite, A2AR display a more restricted expression pattern: A2AR are highly expressed in the olfactory bulb and striatum,150 whereas in the neocortex and hippocampus they are present at residual levels151,152 (Fig. 4A, B). A2AR are mostly located in glutamatergic synapses,153 although they have been shown in other synapses, such as GABAergic146,154,155 (Fig. 4C), dopaminergic,156,157 cholinergic,158,159 serotoninergic,160,161 or noradrenergic synapses.162

FIG. 4.

Adenosine A2AR, distributed heterogeneously throughout the body, have important physiological functions in neurons, astrocytes, and microglia. (A) A2AR are particularly expressed in the lungs, spleen, thymus, heart, blood vessels, muscle, and brain.267 (B) A2AR are highly expressed in the olfactory bulb and striatum, whereas in the neocortex and hippocampus, they are present at residual levels. (C) Exogenous A2AR activation induces a presynaptic enhancement of phasic GABAergic inputs from parvalbumin-expressing neurons to other GABAergic INs, driving disinhibition of PYR (green line), whereas A2AR activation in PYR, presynaptically located, enhances glutamatergic inputs to other glutamatergic neurons (green line); A2AR do not affect neither monosynaptic inhibitory inputs to excitatory neurons nor monosynaptic glutamatergic inputs to INs (black line). (D) A2AR, predominantly presynaptic, increase the release of glutamate in the hippocampus, possibly by inducing Ca2+ uptake and PKA-dependent Ca2+ currents through P-type Ca2+ channels in the presynaptic CA3 neurons that project onto the CA1 PYR. Postsynaptically, A2AR facilitates AMPAR-evoked currents via PKA and increases mGluR5-dependent NMDAR phosphorylation and NMDAR-responses in CA1. However, pre- or postsynaptic localization of A2AR and whether this is a direct or indirect interaction is lacking. In astrocytes, A2AR activation induces astrocytic proliferation and activation and decreases glutamate uptake by controlling the expression levels of glutamate transporters subtypes GLT-I and GLAST.220,279,280 Microglial A2AR drive proliferation and activation, process retraction and release of important immune mediators, particularly cyclooxygenase, PGE2, NO, and IL-1β.281–286 A2AR, A2A receptors; CA1 and CA3, cornu ammonis 1 and 3; CCK+, cholecystokinin-positive interneuron; COX2, cyclooxygenase 2; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IN, interneuron; NO, nitric oxide; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PV+, parvalbumin-positive interneuron; PYR, pyramidal cell; SLM, stratum lacunosum-moleculare; SO, stratum oriens; SP, stratum pyramidale; SR, stratum radiatum. Color images are available online.

Adenosine levels are tightly controlled by a complex machinery of enzymes. However, in the aged rat, the activity of the enzymes that form adenosine from ATP (5′-nucleotidases) and terminate adenosine actions by phosphorylation to AMP (adenosine kinase, ADK) have been reported to be increased, possibly leading to the reported elevation of adenosine levels in the brain163–165 and interference with the transmethylation pathway. This can at least explain the decrease in global DNA methylation observed upon aging.

Glucose metabolism impairment or mitochondria dysfunction, common features observed in aging, and AD may lead to the reduction of cellular ATP levels and trigger the process of ATP production from adenosine. Accordingly, ATP levels are significantly reduced in the brain of APPswe/PS1dE9 mice166 and can lead to a reduction in adenosine levels and mitochondria dysfunction.167–169 Adenosine acts as a cellular sensor of intracellular ATP levels: elevation of adenosine in response to falling ATP levels has cytoprotective effects, whereas when decoupled from ATP levels can be cytotoxic to the cell.168 In AD, adenosine levels have been categorized according to AD stage.167 Alonso-Andrés et al. showed that adenosine is the most affected purine in AD, being decreased since early stage,167 possibly as a result of a decrease in 5′-nucleotidases.170 Adenosine augmentation has been found beneficial in multiple neurological disorders, including AD.171,172 However, further comprehension of the mechanism and the putative effects on adenosine receptors and downstream signaling pathways are crucial at this stage.

In glutamatergic synapses, under physiological conditions and basal activity, adenosine preferentially stimulates A1R, leading to inhibition of glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the hippocampus.173,174 Adenosine can also activate A2AR, which decreases A1R binding and thus an inhibition of A1R actions.143 Several studies addressed the cellular mechanisms triggered by A2AR activation, either by modulating the adenosine endogenous levels pharmacologically and/or by applying its specific agonist, such as CGS21680, allowing a comprehensive knowledge of its action, as follows. A2AR, predominantly presynaptic,153 increase the release of glutamate in the hippocampus,143,175 possibly by inducing Ca2+ entry176 and PKA-dependent Ca2+ currents through P-type Ca2+ channels in the presynaptic CA3 neurons177 that project onto the CA1 pyramidal cells (Fig. 4C, D). Postsynaptically, A2AR facilitates AMPAR-evoked currents via PKA in CA1 pyramidal neurons, independent of NMDAR and GABAA receptor activation or synaptic activity178 (Fig. 4D). In mossy fiber synapses, A2AR activation along the extrasynaptic plasma membrane of CA3 dendritic spines is essential for LTP of NMDAR-EPSCs.179 This LTP is dependent on postsynaptic Ca2+ rise, NMDAR, mGluR5, and Src tyrosine kinases family activation.179 This was the first article that provided electrophysiological evidence and biological relevance for a A2AR-mGluR5-NMDAR interaction.

Other studies also hinted at a possible A2AR-NMDAR interaction, since A2AR activation increases mGluR5-dependent NMDAR phosphorylation and NMDAR-responses in CA1.180–182 However, the exact pre- or postsynaptic localization of A2AR and whether this is a direct or indirect interaction is yet to be clarified (Fig. 4D). Also, A2AR seem to act as fine-tuners of other neuromodulatory systems, since A2AR activation is required to observe synaptic effects of neuropeptides145,183–185 or growth factors, namely for the facilitatory actions of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) on synaptic transmission145,185,186 and on LTP.187 Furthermore, A2AR activation decreases the efficiency of presynaptic inhibitory systems, namely cannabinoid CB1 receptors.188,189 However, whether these effects are mediated by neuronal or glial A2AR is still a matter of debate. As indicated, some of the above mentioned effects of A2AR on glutamate transmission were observed upon exogenous activation with agonists, such as CGS 21630.143,175,176,178 However, this may not replicate exactly the endogenous activation-mediated actions.

The comprehensive characterization of the full A2AR KO mice allowed to study the role of these receptors under physiological conditions. These mice display reduced exploratory activity, increased anxiety, and aggressiveness.190 Furthermore, mice lacking A2AR show improved spatial recognition memory191 and preferential enhancement of working memory.192

However, chronic or acute blockade of A2AR does not alter neither basal glutamate transmission nor the magnitude of LTP or LTD,100,193,194 and knocking-out the A2AR does not impact on LTD,195 strongly suggesting a lack of A2AR constitutive activation in young glutamatergic synapses. This idea is further supported by the absence of effect of A2AR chronic blockade or genetic deletion in the Morris water maze and Y-maze tests.100,193,195,196 A question might be raised: How could A2AR behavioral phenotypes, which suggest some memory processes, are upon the control of A2AR, be reconciled with the absence of an A2AR constitutive activation in young glutamatergic synapses? Novel mice models with neuronal circuitry/cell type selective A2AR deletion will allow to dissect which synapses/cells are implicated in the mechanisms underlying these memory phenotypes, excluding artefacts/compensations due to full genetic ablation of the receptor.

A2AR expression and signaling is profoundly altered in the hippocampus upon aging. A2AR density and coupling to G protein is increased,100,144,164,197–199 probably enhancing the action of this receptor to facilitate neurotransmitters release in glutamatergic synapses by a presynaptic mechanism.197 However, whether this increase in G protein coupling is due to receptors covalent modifications or other alterations is not known yet.144,197 This age-related enhanced A2AR-mediated facilitation of synaptic transmission is dependent on PKA and is associated to an increase in cAMP accumulation.144 Other authors also observed an enhanced role of A2AR in the modulation of LTP, since A2AR antagonist SCH58261-induced decrease in LTP is increased in aged animals,199 either due to alterations in A2AR or changes in dynamic range of LTP.

Although at physiological levels, the expression of A2AR in the hippocampus seems to be protective, by fine-tuning the function of other protein-partners, such as the BDNF-TrKB signaling,145,185–187 the fact is that A2AR overexpression, in a similar magnitude, to the one observed in human aging, is deleterious, as it is sufficient to trigger synaptic and cognitive deficits. This effect involves a mGluR5-dependent NMDAR overactivation, leading to enhanced Ca2+ influx,100 which recapitulates the main synaptic alterations observed upon aging (see previous section). The way mGluR5 activates NMDAR is still unclear, and several alternatives are plausible. mGluR5 are linked to NMDAR via a Homer/Shank/PSD-95 complex of proteins200–202 and several studies have found that mGluR5 enhances NMDAR currents through a PKC/IP3-calcium-dependent mechanism.203–206 Our group provided evidence that A2AR activation mediates mGluR5-dependent NMDAR phosphorylation of the residue Tyr1472 of GluN2B subunit by Fyn kinases activation in a PD model193 (Fig. 5), as previously reported by others in physiological conditions.181

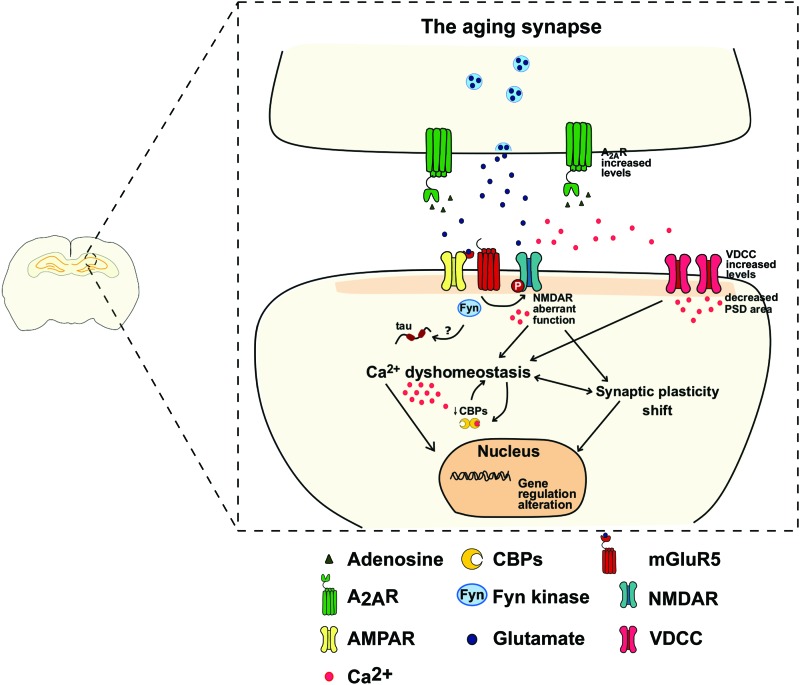

FIG. 5.

The aging synapse: in the CA1 area of the hippocampus, A2AR increased levels are associated with postsynaptic impairments, such as a mGluR5-dependent NMDAR activation, possibly through Fyn Kinases. NMDAR aberrant activation and VDCC increased expression trigger an increase in Ca2+ influx. Associated with a dysfunction of CBPs, this mechanism shifts Ca2+-dependent induction mechanism, which explains the alterations observed in LTP and LTD upon aging. Ca2+ dyshomeostasis and the associated synaptic plasticity shift impair gene regulation, further exacerbating synaptic dysfunction. Color images are available online.

Whether mGluR5 activates NMDAR by multiple pathways in the same synapses or if each pathway is region-specific is still unclear. Another important target of the kinase activity of Fyn is tau, and this interaction was already shown to be important in the AD-related tau hyperphosphorylation207,208 (Fig. 5). Physiologically, Fyn regulates NMDAR activity.209,210 On the contrary, tau-Fyn interaction leads to Fyn accumulation in the soma, preventing Fyn from migrating to postsynaptic site,208 possibly leading to aberrant NMDAR signaling observed in aging and AD.

One of the hypothetic mechanisms for these age-associated alterations in A2AR is a shift in dimerization process. In physiological conditions, A1R and A2AR are coexpressed in CA1 pyramidal neurons153 and A2AR activation decreases presynaptic A1R binding and functional responses in aged animals via PKC.211 Importantly, attenuation of A1R responses elicited by A2AR activation is larger in amplitude than the direct facilitatory effect of A2AR agonist CGS21680, suggesting that the main role of A2AR in young animals is to modulate A1R responses rather than to directly facilitate neuronal excitability.211 These age-associated A1R-A2AR cross talk loss and amplification of A2AR-mediated responses suggest alterations in the organization and relative densities of GPCR and intracellular pathways, namely change in nature of the interaction, that is, homodimer A2AR-A2AR rather than heterodimer A2AR-A1R formation.

In the striatum, A2AR and A1R form heteromers and, under physiological conditions, adenosine preferentially activate A1R,212,213 which controls glutamatergic neurotransmission, namely by a decrease in NMDAR-mediated responses.214,215 If a stoichiometric upsurge favoring nonheteromer forming A2ARs results in Gs-dominant signaling,177 then an A2AR assembly switch could be the primary event driving this pathological glutamate output. However, due to the physiological residual levels of A2AR in the hippocampus and lack of experimental tools and techniques, the question of A1R-A2AR heterodimerization in glutamatergic synapses or a putative age-associated dimerization switch has not been yet solved.

Alzheimer's disease

An increase in hippocampal A2AR expression is also observed in several other pathologies in humans, in which there is a clear correlation of hippocampal A2AR upregulation with cognitive deficits, such as in Alzheimer's100,217 and Pick's disease.218 Interestingly, adenosine levels are significantly increased in parietal and temporal cortices from the early stages of AD postmortem brains, alterations that occur independently of neurofibrillary tangles and β-amyloid plaques,167 which would further enhance A2AR activation and signaling.

Neuronal and astrocytic primary cultures incubated with Aβ-oligomers point out the therapeutic effect of A2AR blockade. Either caffeine (nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist) or ZM241385 (selective A2AR antagonist) prevented neuronal loss caused by incubation of Aβ25–35 in rat cultured cerebellar granule neurons.219 In cortical primary astrocytes, treatment with SCH58261 rescues the decreased expression of glutamate transporters GLAST and GLT-1 and increased GFAP immunoreactivity caused by incubation with Aβ1–42, suggesting that astrocytic A2AR can therapeutically modulate the AD-associated increased levels of extracellular glutamate and astrocytic reactivity.220 Importantly, these effects seem to be dependent of A2AR since Aβ1–42 can no longer induce such astrocytic alterations in global-A2AR-KO220 and, in this case, we cannot rule out neuronal A2AR contribution in this Aβ-induced astrocytic dysfunction.

There is also compelling evidence from animal models of an aberrant A2AR expression and signaling in AD. Intercerebroventricular injection of Aβ1–42 in mice and rats induces loss of nerve terminal markers and memory impairments, which were rescued upon either pharmacological blockade or genetic inactivation.221 Neuronal A2AR play an important role in this synaptic dysfunction, since SCH58261 also has a beneficial effect in preventing loss of synaptic markers in cultured hippocampal neurons incubated with the same Aβ fragment.221 Opposite to what is described,211 A2AR-mediated effects are dependent on p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and independent of cAMP/PKA,221 suggesting that A2AR may activate parallel and independent pathways that ultimately converge to induce synaptotoxicity.

The A2AR-mediated effects on synaptic dysfunction are particularly visible in a mouse model of tauopathy, Thy-Tau22. A2AR deletion is sufficient to prevent memory defects, LTD impairments, and Tau hyperphosphorylation observed in these animals.195 Importantly, chronic treatment with the A2AR antagonist MSX-3 rescued hippocampal-dependent memory even after onset of the pathology,195 further emphasizing the central role of A2AR in synaptic and memory dysfunction. Whether this is an astrocytic or neuronal A2AR role remains inconclusive. The fact that Thy-Tau22-A2AR−/− mice exhibit decreased astrogliosis further supports the hypothesis of an astrocytic contribution to the A2AR-mediated deficits, but does not discard a putative neuronal role. Consistent with this view, astrocytic A2AR overexpression in AD human samples was assessed by correlation between A2AR-encoding gene (ADORA2A) and GFAP messenger RNA (mRNA) levels and immunohistochemistry,217 although neuronal expression was not addressed. Chemogenetic activation of astrocytic Gs-coupled signaling increases cAMP and CREB and reduces long-term memory in mice217 and conditional ablation of A2AR in astrocytes reduces memory deficits in 15–18 m.o. hAPP animals.217

In APP/PS1 animals (double transgenic mice expressing a chimeric mouse/human amyloid precursor protein [Mo/HuAPP695swe] and a mutant human presenilin 1 [PS1-dE9]), an AD mouse model, lack of associative NMDAR-independent LTP in an early stage and cognitive impairments in the Y-maze test222 are rescued upon pharmacological and viral A2AR blockade in neurons.222 Interestingly, either A2AR or mGluR5 blockade rescues LTP back to wildtype (WT) levels, suggesting that A2AR and mGluR5 operate through a common pathway to impair LTP, as we also observed.100,193 The crucial neuronal A2AR role on synaptic dysfunction was further highlighted by us and others, since neuronal A2AR overexpression is sufficient to trigger CREB-dependent synaptic and memory dysfunction.100,223 We found that aged animals could be divided into two subsets: age-impaired animals, which performed worse than young rats in the Y-maze test, revealing no preference for the novel arm, and age-unimpaired animals performed within the range of young rats. Age-impaired animals seem to be distinguished by an LTD-to-LTP shift, whereas age-unimpaired animals could be distinguished by their lack of response to LFS. Consistent with an enhanced role of A2AR upon aging, SCH 58261 decreased basal transmission in hippocampal slices of aged animals, while no effect was observed in young animals. A tendency toward an increased effect of SCH 58261 in age-impaired subset, when compared with age-unimpaired animals, suggests an increased A2AR activation in age-impaired animals.100

More specifically, a 3-week treatment with the selective A2AR antagonist KW6002 restored memory impairments.100 The fact that an acute A2AR blockade is sufficient to rescue the LTD-to-LTP shift favors the hypothesis that A2AR blockade reestablishes the physiological signaling of adenosine, rather than the receptor expression, which is unlikely to occur at such a short time frame. Accordingly, we have prior data showing that chronic KW6002 treatment rescues cognitive and synaptic impairments induced by stress, without altering A2AR levels.224

Also, A2AR activation increases Ca2+ influx via mGluR5 and NMDAR in primary neuronal cultures, discarding any major A2AR astrocytic contribution.100 Furthermore, we observed neuron-specific A2AR staining and aged humans and AD patients' hippocampus,100 consistent with previous data, in which single-cell polymerase chain reaction of laser-dissected cells of young rats revealed no A2AR transcripts in GFAP positive cells.153 Plus, in some brain pathological conditions, characterized by astrogliosis or increases in excitability, such as mesial temporal lobe epilepsy, there is a profound increase in A2AR in astrocytes that is not related with Aβ or any other features of neurodegenerative disease.225 Interestingly, a recent study showed that deletion of A2AR selectively in forebrain neurons prevented convulsions-induced neurodegeneration (decreased synaptic plasticity, loss of synaptic markers, and neuronal loss) in a kainate model of temporal lobe epilepsy.226 Altogether, these data strongly suggest that it is a synergism of astrocytic and neuronal A2AR-mediated effects that defines the robust ability to control synaptic and memory dysfunction: synaptic dysfunction in aging and early AD may be driven predominantly by a neuronal A2AR progressive dysfunction, whereas at later Braak stages of AD, astrocytic AD and inflammation may become more relevant.

Most importantly, this A2AR pathological role was also observed in humans: AD patients exhibit an increase in A2AR expression100,227 and a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in ADORA2A was recently associated with episodic memory performance, hippocampal volume, and total tau in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD patients,228 suggesting that this variation may affect A2AR production. However, this still needs to be confirmed in future studies. Also, multiple prospective and retrospective studies emphasize the role of caffeine, a nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist, in slowing down cognitive decline in aged population and reducing the risk of developing AD.

Regulation of ADORA2A gene expression

An important question yet to be clarified is the mechanism by which A2AR expression increases upon aging and AD on the hippocampus. Given the role of A2AR in multiple brain regions, the regulation of its expression and signaling has received great attention. A 4.8 kb promoter-proximal DNA fragment in the ADORA2A confers selective expression in the CNS, but does not explain the strong expression observed in the striatum.229 These results suggest that the A2AR expression is also controlled by other (epi)genetic factors that regulate the expression in each brain structure.

In fact, the coding for the A2AR exists in two exons interrupted by one intron and has multiple promoters that lead to the production of various A2AR transcripts.230,231 Each A2AR transcript contains the same coding region plus an identical 3′untranslated region (UTR) and a distinct 5′UTR. This particular feature is conserved among species and might lead to the production of various transcripts with different 5′UTRs that control the transport, the translation efficiency, and the selection of the translational start site of the targeted transcript.232,233 Accordingly, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) shifts A2AR transcription from a longer 5′UTR to a shorter one, possibly increasing translation efficiency.231 Therefore, different strategies in the transcriptional control of A2AR may underlie differences in expression and signaling in physiological versus pathological conditions.

ADORA2A is a dual coding gene: in addition to the A2AR protein, a 134-amino acid protein (uORF5) can be translated from an upstream open reading frame of the rat A2AR gene.234–236 Expression of uORF5 was detected in rat striatum, associated with high A2AR mRNA levels.237 In a rat pheochromocytoma line (PC12), uORF5 suppresses the activity of the transcription activator protein 1 (AP1) and regulates expression of proteins implicated in MAPK pathway.237 Interestingly, A2AR activation led to a PKA-dependent increase in uORF5 protein levels at the posttranscriptional level, suggesting that uORF5 might act downstream of A2AR and regulate A2AR activity.237

Epigenetic A2AR regulation

Several agents have been implicated in the epigenetic regulation of ADORA2A, including transcription factors (CREB, NF-1, NFκB, PPARgamma, YY-1, and ZBP-89), proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-alpha), microRNA (miRNAs; miRNA-214, miRNA-34b, miRNA-15, and miRNA-16), and DNA methylation.238–251

In polymorphonuclear leukocytes, the increase in A2AR mRNA expression upon LPS stimulation correlates inversely with the expression levels of miRNA-214, miRNA-15, and miRNA-16.247 Reduced miRNA-34b levels were related to increased A2AR levels in the putamen of PD patients, although alterations in miRNA-214, miRNA-15, and miRNA-16 were not found.243

Both genetic and pharmacological approaches revealed that DNA methylation by adenosine is receptor-independent. Genetic removal of ADK in the mouse forebrain, which leads to the elevation of intracellular adenosine, causes the reduction of DNA methylation. Chronic administration of an ADK inhibitor (5-iodotubercidin) in mice decreased global DNA methylation in the hippocampus of WT or A1R KO mice.252 Besides, liver-rescued adenosine deaminase (ADA) KO mice show elevated adenosine level and DNA hypomethylation in the placenta. A similar phenomenon is observed in liver-rescued ADA and ADORA2B double KO mice.253 Furthermore, an in vitro study showed that A2AR (ZM 241385) and A2BR (MRS1754) antagonism does not change adenosine-induced hypomethylation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells.254

Interestingly, although epigenetic effect of adenosine is receptor-independent, adenosine receptor gene(s) could also be epigenetically modified through global methylation. A previous study has identified three CpG islands in the 5′UTR region of human ADORA2A, which regulates its gene and protein expression. Buira et al. used different types of cell lines, including HeLa (epithelial cells), SH-SY5Y (neuroblastoma cells), and U87-MG (glioblastoma cells), which have distinct A2AR mRNA expression levels to demonstrate the impact of DNA methylation on A2AR expression. The endogenous A2AR mRNA expression levels are inversely correlated with DNA methylation level in these cells.241 DNA-methylation inhibitor (5-azacytidine) or activator (S-adenosyl-L-methionine) treatments increase or decrease A2AR expression, respectively.241 Furthermore, the same group observed the same phenomenon in the two cerebral regions (putamen and cerebellum) of the human brain.242

Besides DNA methylation, histone acetylation is a mechanism that allows tight but transient regulation of gene expression. Histone H3 acetylation is one of the most frequent epigenetic mechanism that increases the expression of the target genes by chromatin opening. We observed that chronic A2AR blockade with KW6002 increased ADORA2A acetylation (unpublished data), consistent with the increase in A2AR expression observed upon treatment,100,224 providing new insights into KW6002 mechanism of action.

In conclusion, these aspects of gene regulation upon aging are still poorly understood and surely deserve much more attention if one wants to pinpoint the age-related A2AR expression shift which impacts on cognition. Very relevant steps were taken recently, when for the first time, a SNP in the ADORA2A gene was associated with episodic memory performance, hippocampal volume, and total tau in CSF in MCI and AD patients.228 This polymorphism occurs in a noncoding region, upstream to the coding sequence and it was just suggested, but not studied, that it could imply alterations in A2AR expression.

Caffeine effects in aging and AD

Caffeine is the world's most popular psychoactive drug and is consumed by millions of people. While short-term CNS stimulating effects of caffeine are well-known,255 the long-term impact remains not completely clear. The Finland, Italy, and the Netherlands Elderly (FINE) Study showed that coffee intake was inversely associated with cognitive decline. In fact, elderly men (70 ± 10 years) who consumed coffee had a two times smaller 10-year cognitive decline than nonconsumers.256 Accordingly, there was also an inverse association between the number of cups of coffee consumed per day and 10-year cognitive decline, with the least decline for men consuming three cups per day.256 Furthermore, in the Three City Study, with a sample of subjects aged 65 years and older, consumption of at least three cups of coffee per day was associated with less decline in verbal memory in women.257 On the opposite, coffee had no significant protective effect in women with less than two daily units.257

Importantly, other studies support a role for caffeine in the prevention of AD. A retrospective study reported an inverse correlation between coffee consumption and disease onset—AD patients had an average daily caffeine intake of 73.9 ± 97.9 mg during the 20 years before AD diagnosis, whereas the control had an average daily caffeine intake of 198.7 ± 135.7 mg during the corresponding 20 years of their lifetimes.258 In a prospective study, daily coffee drinking decreased the risk of AD by 31% during a 5-year follow-up.259 In line with those findings, moderate coffee drinkers (three to five cups of coffee per day) had a 65–70% decreased risk of dementia and a 62–64% decreased risk of AD compared with low coffee consumers.260 Furthermore, another prospective study showed that plasma caffeine levels at study onset were substantially lower (−51%) in MCI subjects who later progressed to dementia compared to levels in stable MCI subjects. Also, plasma caffeine levels >1200 ng/mL (≈6 μM) in MCI subjects were associated with no conversion to dementia during the ensuing 2/4-year follow-up period.261 However, coffee and caffeine intake in midlife were not associated with cognitive impairment, dementia, or individual neuropathologic lesions.262 It is noteworthy that higher caffeine intake was associated with lower odds of having any neuropathological lesions at autopsy, including AD-related lesions, microvascular ischemic lesions, cortical Lewy bodies, hippocampal sclerosis, or generalized atrophy.262

The beneficial effects of caffeine in humans are not confined to AD. Epidemiological studies show an inverse relationship between the consumption of caffeine and the risk of developing PD263,264 and two ADORA2A polymorphisms (r71651683 and rs5996696) were inversely associated with PD risk.265 Although the mechanism was not directly addressed, the beneficial effects seem to be achieved via A2AR blockade.266,267 Caffeine is metabolized primarily by cytochrome P450 1A2 (CYP1A2). An A to C substitution at position 163 in the CYP1A2 decreases enzyme inducibility. However, there is no association between this genetic alteration and caffeine consumption. In the brain, A2AR activation has an important role in the stimulating and reinforcing properties of caffeine190,268 and A2AR KO mice have less appetite for caffeine than WT littermates.269 A C to T substitution at position 1083 in the ADORA2A gene was associated with caffeine-induced anxiety among nonhabitual caffeine consumers270 and the probability of having such mutation decreases as the caffeine intake increases in a population, and people with that genotype are more likely to limit their caffeine intake.271

Caffeine consumption has been shown to improve the memory performance in multiple AD mice models, ascertaining its protective properties against cognitive impairment and in favor of improved memory retention (see Kolahdouzan and Hamadeh 272). In aged rodents, perfusion of caffeine rescued neuronal A2AR-driven synaptic plasticity shift in the hippocampus,100 while having no effects in excitatory CA1 currents in young animals.194 In aged animals, chronic intake of caffeine for 12 months prevents age-associated recognition memory decline, possibly by restoring BDNF signaling.273 Chronic caffeine consumption also rescued synaptic and memory impairments in a mouse model of chronic unpredictable stress in a manner similar to selective A2AR antagonist (KW6002) administration or A2AR genetic deletion selectively in neurons,274 being that stress is a physiopathological condition associated with upsurge of A2AR and hippocampal dysfunction.224,274 Memory deficits were prevented by caffeine in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease, both amyloid and Tau-based.195,275–277

The caffeine-mediated beneficial effects also included decrease in several proinflammatory (CD68, CD45, TLR2, CCL4, and TNFα) and oxidative stress (Nrf2, MnSOD, and EAAT3) markers found upregulated in the hippocampus of THY-Tau22 animals.278 Interestingly, caffeine reduces tau phosphorylation in different residues from the ones observed with A2AR antagonist genetic deletion195,278 and decreases the amount of Tau proteolytic fragments,278 a pathological feature that is not influenced by genetic deletion.195 These results suggest that regulation of Tau by caffeine may result from a wider range of actions than from inhibition of A2AR function alone.

Conclusion

In summary, age-related memory impairments are explained by changes in neuronal and synaptic morphology and function, namely reduction in the amplitude of the Schaffer collaterals-induced fEPSP and in PSD area in CA1.62–64 These results, associated with maintenance of the unitary EPSP size,66 suggest that aging might not be associated with alterations in the strength of individual synaptic connections, but instead with an increase in nonfunctional or silent synapses in the hippocampus.

The changes observed at individual synapses directly affect synaptic plasticity mechanisms, namely an alteration in the susceptibility to induce LTP and LTD due to a shift in Ca2+-dependent induction mechanisms.84,99 Together with impairments in calcium buffering and influx mechanisms, such as via NMDAR and L-type VDCC (voltage-dependent calcium channels),103,111,112,121–125 these observations support the calcium hypothesis of aging, which implicates raised intracellular Ca2+ as the major source of functional impairment and degeneration in aged neurons.104–106

Caffeine is the world's most popular psychoactive drug and is consumed by millions of people. Multiple prospective and retrospective studies emphasize the role of caffeine, adenosine receptor antagonist, in slowing down cognitive decline in aged population and reducing the risk of developing AD. Although the mechanism is not yet disclosed, the beneficial effects seem to be achieved via A2AR blockade.266,267

A2AR expression and signaling is profoundly altered in the hippocampus upon aging. A2AR density and coupling to G protein is increased,100,144,197–199 probably enhancing the efficiency of this receptor to facilitate neurotransmitters release in glutamatergic synapses by a presynaptic mechanism.197 Interestingly, neuronal A2AR overexpression in the same magnitude to the one observed in human aging is sufficient to trigger synaptic and cognitive deficits, due to a mGluR5-dependent NMDAR overactivation and linked to enhanced Ca2+ influx,100 which recapitulates the main synaptic alterations observed upon aging. Importantly, either A2AR pharmacological blockade or genetic deletion prevents synaptic and memory impairments in aged rodents and several AD models.100,222,223,278

Because of the diversity and complexity of the adenosine receptor-dependent and independent regulatory mechanisms, a better understanding of the precise mechanism of adenosine and its receptors in pathophysiological conditions in different brain regions and CNS cell types will allow the development of novel therapeutic strategies for synaptic and memory dysfunction upon aging and AD.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge Ching-Pang Chang for the important contribution for the section on the regulation of ADORA2A gene expression.

Authors' Contributions

M.T.-F. has written the article. M.T.-F., J.E.C., P.A.P., and L.V.L. discussed the article. All authors have reviewed and approved the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

M.T.-F. and J.E.C. were supported by a fellowship from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT, Portugal); L.V.L is an Investigator CEEC-FCT. P.A.P. is supported by EU Joint Program—Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND) project CIRCPROT (jointly funded by BMBF, MIUR, and EU Horizon 2020 grant agreement no. 643417). This study was also funded by Santa Casa da Misericórdia - Mantero Belard 2018 (MB-7-2018) and by UID/BIM/50005/2019, project funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT)/ Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior (MCTES) through Fundos do Orçamento de Estado.

References

- 1. Morrison JH, Hof PR. Life and death of neurons in the aging brain. Science. 1997;278:412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bartsch T, Wulff P. The hippocampus in aging and disease: From plasticity to vulnerability. Neuroscience. 2015;309:1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Strange BA, Witter MP, Lein ES, et al. Functional organization of the hippocampal longitudinal axis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:655–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amaral DG, Scharfman HE, Lavenex P. The dentate gyrus: Fundamental neuroanatomical organization (dentate gyrus for dummies). Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:3–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lisman JE. Relating hippocampal circuitry to function: Recall of memory sequences by reciprocal dentate-CA3 interactions. Neuron. 1999;22:233–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lisman JE, Otmakhova NA. Storage, recall, and novelty detection of sequences by the hippocampus: Elaborating on the SOCRATIC model to account for normal and aberrant effects of dopamine. Hippocampus. 2001;11:551–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lavenex P, Amaral DG. Hippocampal-neocortical interaction: A hierarchy of associativity. Hippocampus. 2000;10:420–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Megías M, Emri Z, Freund TF, et al. Total number and distribution of inhibitory and excitatory synapses on hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Neuroscience. 2001;102:527–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andersen P, ed. The Hippocampus Book. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wheeler DW, White CM, Rees CL, et al. Hippocampome.org: A knowledge base of neuron types in the rodent hippocampus. ELife. 4 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.09960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11. Bezaire MJ, Soltesz I. Quantitative assessment of CA1 local circuits: Knowledge base for interneuron-pyramidal cell connectivity: Quantitative assessment of ca1 local circuits. Hippocampus. 2013;23:751–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gasbarri A, Sulli A, Packard MG. The dopaminergic mesencephalic projections to the hippocampal formation in the rat. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1997;21:1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McNamara CG, Dupret D. Two sources of dopamine for the hippocampus. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40:383–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fisahn A, Pike FG, Buhl EH, et al. Cholinergic induction of network oscillations at 40 Hz in the hippocampus in vitro. Nature. 1998;394:186–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moore RY, Halaris AE. Hippocampal innervation by serotonin neurons of the midbrain raphe in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1975;164:171–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ohmura Y, Izumi T, Yamaguchi T, et al. The serotonergic projection from the median raphe nucleus to the ventral hippocampus is involved in the retrieval of fear memory through the corticotropin-releasing factor type 2 receptor. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1271–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shepherd GM, Harris KM. Three-dimensional structure and composition of CA3—>CA1 axons in rat hippocampal slices: Implications for presynaptic connectivity and compartmentalization. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8300–8310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hassel B, Dingledine R. Glutamate and glutamate receptors. In: Basic Neurochemistry. Siegel G.J., Agranoff B.W., Albers R.W., Fisher S.K. and Uhler M.D. (Eds). Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2012: pp. 342–366 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kennedy MB. The postsynaptic density at glutamatergic synapses. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:264–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Uchigashima M, Ohtsuka T, Kobayashi K, et al. Dopamine synapse is a neuroligin-2-mediated contact between dopaminergic presynaptic and GABAergic postsynaptic structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:4206–4211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Citri A, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity: Multiple forms, functions, and mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:18–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abraham WC, Christie BR, Logan B, et al. Immediate early gene expression associated with the persistence of heterosynaptic long-term depression in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10049–10053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abraham WC, Logan B, Greenwood JM, et al. Induction and experience-dependent consolidation of stable long-term potentiation lasting months in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9626–9634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Staubli U, Scafidi J. Studies on long-term depression in area CA1 of the anesthetized and freely moving rat. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4820–4828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lynch MA. Long-term potentiation and memory. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:87–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ziemann U, Ilić TV, Iliać TV, et al. Learning modifies subsequent induction of long-term potentiation-like and long-term depression-like plasticity in human motor cortex. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1666–1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dong Z, Bai Y, Wu X, et al. Hippocampal long-term depression mediates spatial reversal learning in the Morris water maze. Neuropharmacology. 2013;64:65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ge Y, Dong Z, Bagot RC, et al. Hippocampal long-term depression is required for the consolidation of spatial memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16697–16702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stevens CF. A million dollar question: Does LTP = memory? Neuron. 1998;20:1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Squire LR, Kandel ER. Memory: From Mind to Molecules. 2nd ed. Greenwood Village, CO: Roberts; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huganir RL, Nicoll RA. AMPARs and synaptic plasticity: The last 25 years. Neuron. 2013;80:704–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Silva AJ, Stevens CF, Tonegawa S, et al. Deficient hippocampal long-term potentiation in alpha-calcium-calmodulin kinase II mutant mice. Science. 1992;257:201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mulkey RM, Endo S, Shenolikar S, et al. Involvement of a calcineurin/inhibitor-1 phosphatase cascade in hippocampal long-term depression. Nature. 1994;369:486–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barria A, Muller D, Derkach V, et al. Regulatory phosphorylation of AMPA-type glutamate receptors by CaM-KII during long-term potentiation. Science. 1997;276:2042–2045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kameyama K, Lee HK, Bear MF, et al. Involvement of a postsynaptic protein kinase A substrate in the expression of homosynaptic long-term depression. Neuron. 1998;21:1163–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee HK, Kameyama K, Huganir RL, et al. NMDA induces long-term synaptic depression and dephosphorylation of the GluR1 subunit of AMPA receptors in hippocampus. Neuron. 1998;21:1151–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee HK, Barbarosie M, Kameyama K, et al. Regulation of distinct AMPA receptor phosphorylation sites during bidirectional synaptic plasticity. Nature. 2000;405:955–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Turrigiano G. Homeostatic synaptic plasticity: Local and global mechanisms for stabilizing neuronal function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:1–17. DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. von der Malsburg C. Self-organization of orientation sensitive cells in the striate cortex. Kybernetik. 1973;14:85–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Miller KD, MacKay DJC. The role of constraints in Hebbian learning. Neural Comput. 1994;6:100–126 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hobbiss AF, Ramiro-Cortés Y, Israely I. Homeostatic plasticity scales dendritic spine volumes and changes the threshold and specificity of Hebbian plasticity. iScience. 2018;8:161–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Reitz C, Brayne C, Mayeux R. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:137–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Barnes CA. Memory deficits associated with senescence: A neurophysiological and behavioral study in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1979;93:74–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Colombo PJ, Wetsel WC, Gallagher M. Spatial memory is related to hippocampal subcellular concentrations of calcium-dependent protein kinase C isoforms in young and aged rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14195–14199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Erickson CA, Barnes CA. The neurobiology of memory changes in normal aging. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38:61–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mabry TR, McCarty R, Gold PE, et al. Age and stress history effects on spatial performance in a swim task in Fischer-344 rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1996;66:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Oler JA, Markus EJ. Age-related deficits on the radial maze and in fear conditioning: Hippocampal processing and consolidation. Hippocampus. 1998;8:402–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tanila H, Shapiro M, Gallagher M, et al. Brain aging: Changes in the nature of information coding by the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5155–5166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Burke SN, Barnes CA. Neural plasticity in the ageing brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:30–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ball MJ. Neuronal loss, neurofibrillary tangles and granulovacuolar degeneration in the hippocampus with ageing and dementia. A quantitative study. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 1977;37:111–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Brizzee KR, Ordy JM, Bartus RT. Localization of cellular changes within multimodal sensory regions in aged monkey brain: Possible implications for age-related cognitive loss. Neurobiol Aging. 1980;1:45–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Brody H. Organization of the cerebral cortex. III. A study of aging in the human cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1955;102:511–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Coleman PD, Flood DG. Neuron numbers and dendritic extent in normal aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1987;8:521–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gazzaley AH, Thakker MM, Hof PR, et al. Preserved number of entorhinal cortex layer II neurons in aged macaque monkeys. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:549–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]