Abstract

Objective

Evidence-based screening, assessment, and intervention practices for youth with type 1 diabetes (T1D) are underutilized. Implementation science (IS) offers theoretical models and frameworks to guide rigorous mixed methods research to advance comprehensive care for children and families.

Methods

We conducted a targeted review of applications of IS to T1D.

Results

Pediatric T1D research offers initial, but still limited studies on implementation of evidence-based psychosocial care. IS designates approaches to understanding multi-level factors that influence implementation, ways to alter these factors, and methods to evaluate strategies to improve implementation.

Conclusions

IS is promising for advancing the translation of pediatric psychology approaches into clinical care. Following the science of implementation, further documentation of the reach of evidence-based care and establishing practice guidelines are important initial steps. Examining the barriers and facilitators of evidence-based psychosocial care can guide the development of testable implementation strategies to improve integration of care. Successful strategies can be evaluated through multi-site controlled implementation trials to explore their effectiveness. These lines of inquiry can be considered within pediatric populations, but may also be used to examine similarities and differences in effectiveness of implementation strategies across populations and settings. Such research has the potential to improve the health and well-being of children and families.

Keywords: evidence-based, implementation science, pediatric psychology, services

Evidence-based healthcare practices take an average of 17 years to reach direct clinical care (Morris, Wooding, & Grant, 2011) and there is growing evidence of research-to-practice gaps in pediatric psychology. For example, there are psychosocial standards of care for children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes (T1D; Delameter, de Wit, McDarby, Malik, & Acerini, 2014). However, few pediatric institutions currently meet these standards of care (de Wit, Pulgaron, Pattino-Fernandez, & Delameter, 2014).

Implementation science (IS) research is “the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services and care” (Eccles & Mittman, 2006). IS has yet to be utilized substantively in pediatric psychology despite its potential to improve the research-practice gap (Schurman, Gayes, Slosky, Hunter, & Pino, 2015).

The ultimate goal of IS research is to create generalizable knowledge that can be used broadly to improve implementation of evidence-based practices. A growing number of theoretical frameworks provide an organization to understanding the complex, multi-level factors that influence uptake of evidence-based care (Damschroder et al., 2009). IS offers the potential to facilitate the translation of pediatric psychology approaches into standard practice, ensuring families receive the level of psychosocial support that matches their individual need and optimizes health outcomes. There is strong evidence for the efficacy of screening, assessment and intervention practices for common psychosocial concerns (e.g., adherence, child behavior, family conflict) across health conditions and many youth experience moderate to significant psychosocial challenges that could benefit from evidence-based psychosocial intervention (Kazak, 2006). However, few youth receive these interventions. T1D research is ripe for IS studies given that there are established psychosocial care guidelines and evidence of a significant research-practice gap associated with poorer health outcomes.

The current topical targeted review proposes a model for integrating IS into pediatric psychology research. We provide an overview of IS theory and methods, using examples of potential lines of T1D research, and propose a model for theory-driven research on the implementation of evidence-based pediatric psychology practices in healthcare settings.

Implementation Science

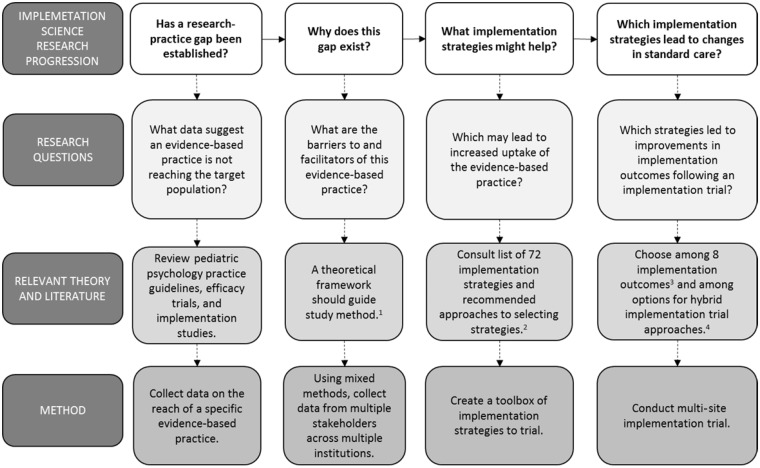

There are several sequential steps that can be taken to advance IS research in pediatric psychology (see Figure 1). We define each step and illustrate the potential T1D research questions that may be explored.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of lines of inquiry in implementation science and pediatric psychology research.

1 Damschroder et al. (2009); Nilsen (2015).2Powell et al. (2015).3Proctor et al. (2011).4Brown et al. (2017); Curran et al. (2012).

Step 1: Understand the Research-Practice Gap in Pediatric Psychology

A first step is to identify the evidence-based T1D practice(s) that are ready for implementation. Recent epidemiological data show that only 28% of youth with T1D achieve the recommended level of glycemic control (Carlsen et al., 2017). Multiple evidence-based pediatric psychology interventions are efficacious in improving metabolic control and addressing barriers to non-adherence (Ellis et al., 2005; Wysocki et al., 2008).

The International Society of Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes guidelines for psychosocial care state that all patients with T1D should have access to behavioral health providers who have expertise in T1D and who provide screening, assessment, and intervention services as part of the multidisciplinary care team (Delameter et al., 2014). However, access to care with a provider who has expertise in behavioral intervention for youth with T1D and their families is often limited. This is a major barrier to improving health outcomes (Zgibor & Songer, 2001).

Only 43% of clinics have a behavioral health provider participate in routine endocrinology visits and only 25% of behavioral health providers see all patients with T1D (de Wit et al., 2014). Even in settings with organized access to evidence-based behavioral interventions with qualified professionals, engagement and follow through with clinic visits and referrals to these services are often poor (Schwartz, Cline, Axelrad, & Anderson, 2011). For example, only 18% of families of children with T1D attend at least one psychology visit across a 2-year period (Markowitz, Volkening, & Laffel, 2014). Thus, a gap exists between what the research suggests are best practices for youth with T1D and the actual delivered services.

Step 2: Establish Evidence Around Facilitators and Barriers of Pediatric Psychology Care

Research in pediatric psychology can employ IS theory and methods to explicate the multi-level barriers and facilitators of evidence-based psychosocial care.

Theories, Models, and Frameworks

IS offers theory and methods to facilitate the spread of evidence-based practices into routine care. There are multiple categories of theory that guide different lines of IS research, from those focused on translating research into practice and those aiming to test the effectiveness of implementation (Nilsen, 2015). Determinant frameworks guide understanding of multi-level factors that influence implementation, an area in which pediatric psychology has a dearth of research (Nilsen, 2015). Such frameworks offer support for understanding facilitators and barriers to implementing evidence-based practices.

To examine the factors that influence uptake of evidence-based intervention for youth with T1D and their families, a determinant framework, such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR; Damschroder et al., 2009)1 would be appropriate. CFIR highlights five domains of factors that influence the implementation of evidence-based practices. Domains delineate factors across (1) those within and (2) outside an organization, (3) characteristics of the individuals involved with implementation, (4) intervention (or evidence-based practice) characteristics, and the (5) implementation process. For example, within the individual characteristics domain, beliefs and attitudes endocrinology providers have about the effectiveness of behavioral intervention to improve adherence to a diabetes care regimen will likely affect implementation of this care. In the domain of implementation process, the level of burden and clarity in the processes for referring and scheduling behavioral intervention services likely influences endocrinology provider and family follow-through with care. Factors within an institution, such as clinic space and amount of support staff to facilitate scheduling, comprise the inner setting domain and also influence uptake (see Table I).

Table I.

Five Domains of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research: Examples of Factors that Influence the Delivery of Pediatric Psychology Care within Each Domain (Damschroder et al., 2009)

| Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Domains |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outer Setting | Inner Setting | Characteristics of the Individual | Intervention Characteristics | Process | |

| Definition of Domain | Factors of economic, political, and social context within which the organization resides | Features of structural, political, and cultural contexts through which implementation process occurs | Attributes of the individuals involved with the intervention and/or implementation process | Characteristics of the intervention being implemented | Factors related to enacting implementation |

| Factors within Domain | Patient Needs and Resources; Cosmopolitanism; Peer Pressure; External Policies and Incentives | Structural Characteristics, Networks and Communications; Culture Implementation Climate; Readiness for Implementation | Knowledge and Beliefs about the Intervention; Self-efficacy; Individual Stage of Change; Individual Identification with Organization; Other Personal Attributes | Intervention Source; Evidence Strength and Quality; Relative Advantage; Adaptability; Trialability; Complexity; Design Quality and Packaging; Cost | Planning; Engaging; Executing; Reflecting and Evaluating |

| Pediatric Psychology Example(s) | Standards for psychosocial care; Payment models for psychosocial care | Quality of electronic health record; Clinic space; Staffing resources | Medical provider belief in own capability to talk with families about pediatric psychology referral | Length and number of sessions of a pediatric psychology intervention | Explicit plan for implementing pediatric psychology care within a medical group |

Methods for Examining Contextual Factors Related to Implementation

IS and pediatric psychology research methods have commonalities. For example, to address IS research questions around barriers and facilitators of evidence-based practice integration into standard care, a mixed qualitative-quantitative approach is the gold standard. Mixed methods and qualitative studies are becoming more common in pediatric psychology as a means to gain a deeper understanding of patient and family experience and perspectives. In contrast to many studies in pediatric psychology, the participant groups in IS research are more varied and go beyond patients and family members to include multiple stakeholders relevant to the study question. This approach affords rich data for optimal understanding of the multi-level factors related to implementation.

To examine multi-layered contextual factors related to the implementation of psychosocial care in T1D, guided by CFIR (Damschroder et al., 2009), studies may collect qualitative and quantitative data from patients and caregivers, as well as insurance payers and hospital leadership. At the outer setting, patient needs, patient and family perspectives, stigma associated with psychological care, and insurance coverage may all be important in understanding the services youth with T1D receive. Inner setting factors also likely play a role, such as those related to staffing and space. For example, clinics need to employ mental health providers and have space available for psychosocial care delivery in order to deliver psychosocial care. Lack of awareness of the effectiveness of pediatric psychology care among patients, families, providers, and payers may contribute to low rates of referrals and minimal follow through with evidence-based intervention.

Step 3: Develop Implementation Strategies

Based on this formative work, implementation strategies to bolster facilitators of evidence-based pediatric psychology practices and address barriers can be designed and tested. Implementation strategies are methods to improve the process of integration (Powell et al., 2015) and draw on formative research around factors that influence implementation.

Methods for Developing Implementation Strategies

The Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (Powell et al., 2015) project defined 72 conceptually unique strategies that may be used in isolation or in combination. Guidelines for the development of evidence-based implementation strategies designate three steps: (1) identify the barriers and facilitators to implementation of an evidence-based clinical practice, (2) design implementation strategies based on these barriers and facilitators, and (3) apply and evaluate these implementation strategies (Flottorp et al., 2013).

For example, information about factors influencing the uptake of pediatric psychology services can be used to design a toolbox of implementation strategies. This toolbox could include electronic health record (EHR)-based reminders for providers about placing appropriate referrals and development and dissemination of educational materials about evidence-based behavioral intervention to providers and/or youth with T1D and their families. Facilitating the relay of clinical data to providers about the percentage of patients with T1D referred for behavioral intervention relative to those eligible is another potential strategy.

Step 4: Evaluate Implementation Outcomes

Once determined, implementation strategies can be systematically evaluated (Brown et al., 2017; Curran, Bauer, Mittman, Pyne, & Stetler, 2012). The outcomes of implementation trials differ from traditional clinical trials.

Methods for Testing Implementation Strategies

Implementation outcomes are defined as “the effects of deliberate and purposive actions to implement new treatments, practices, and services” (Proctor et al., 2011). For example, two of these outcomes, acceptability and penetration, may be particularly important in pediatric psychology, where psychologists aim to become fully integrated into and accepted by medical teams in pediatric hospital settings that are driven by EHRs and complex scheduling and rooming processes. The implementation outcome of acceptability is defined as the perception among stakeholders (e.g., medical providers) that the strategies are palatable or agreeable (Proctor et al., 2011) and is often measured using qualitative interviews with providers. Penetration is defined as the level of integration of the implementation strategy into standard clinic operations. An example of the measurement of penetration involves leveraging EHR data for calculation of the ratio of number of patients with T1D referred to behavioral intervention divided by the number of patients appropriate for referral. Other implementation outcomes may also be relevant, such as fidelity or cost (Proctor et al., 2011).

The most appropriate type of implementation trial will be determined in part by the amount of research supporting the effectiveness of the evidence-based practice. For example, if there is limited effectiveness data for the practice, hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial designs may be indicated. Such trials involve measurement of patient-level health outcomes in addition to traditional implementation outcomes (Curran et al., 2012). Evidence-based pediatric psychology interventions for youth with T1D have ample efficacy data but there have been fewer studies examining outcomes associated with this care as part of standard practice (i.e., minimal effectiveness data). Thus, a hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial evaluating both the penetration of the pediatric psychology intervention into standard care (implementation outcome) and patient’s glycemic control (patient-level outcome) may be indicated.

For example, once the aforementioned toolbox of implementation strategies is designed, it may be tested via a multi-site controlled implementation trial. Specifically, a set of strategies to improve the integration of an evidence-based practice could be systematically introduced across rural, urban, and variably sized and resourced children’s hospitals and ambulatory pediatric care centers with sites, rather than patients, representing participants.

Conclusion

Although the current targeted review employed T1D as an example of how IS can be integrated into pediatric psychology research, similar IS research questions can be explored in other areas of pediatric psychology. These lines of research, and others within the broad field of IS that were outside the scope of this targeted review, have the potential to improve the reach of evidence-based psychosocial care across institutions and thus, improve the overall health of many pediatric populations. A recent study of the financial viability of an integrated clinic serving youth with T1D and their families highlighted the critical importance of service utilization to the survival of such clinics (Yarbro & Mehlenbeck, 2016). Empirically supported implementation strategies to improve the reach of evidence-based psychosocial care may increase the sustainability of integrated care. Moreover, as healthcare payment models move towards pay-for-performance, evidence of psychosocial care improving outcomes and feasibility of delivering this care as standard practice could further solidify the role of pediatric psychologists as integral members of medical teams.

Funding

Dr. Price was supported by a Mentored Research Development Award through an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (U54-GM104941; PI: Binder-Macleod). Dr. Wolk is an investigator with the Implementation Research Institute (IRI), at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis; through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (5R25MH08091607) and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI).

Footnotes

There are many implementation theories. We selected CFIR as an example but there are others that are could be applied to pediatric psychology.

Reference list

- Brown C. H., Curran G., Palinkas L. A., Aarons G. A., Wells K. B., Jones L., Cruden G. (2017). An overview of research and evaluation designs for dissemination and implementation. Annual Review of Public Health, 38, 1–22.s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen S., Skrivarhaug T., Thue G., Cooper J. G., Goransson L., Lovaas K., Sandberg S. (2017). Glycemic control and complications in patients with type 1 diabetes – A registry-based longitudinal study of adolescents and young adults. Pediatric Diabetes, 18, 188–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran G. M., Bauer M., Mittman B., Pyne J. M., Stetler C. (2012). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical Care, 50, 217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder L. J., Aron D. C., Keith R. E., Kirsh S. R., Alexander J. A., Lowery J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4, 50–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delameter A. M., de Wit M., McDarby V., Malik J., Acerini C. L. (2014). Psychological care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes, 15, 232–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit M., Pulgaron E. R., Pattino-Fernandez A. M., Delameter A. M. (2014). Psychological support for children with diabetes: Are the guidelines being met? Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 21, 190–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles M. P., Mittman B. S. (2006). Welcome to Implementation Science. Implementation Science, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis D. A., Frey M., Naar-King S., Templin T., Cunningham P., Cakan N. (2005). Use of multisystemic therapy to improve regimen adherence among adolescents with Type 1 diabetes in chronic poor metabolic control: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care, 28, 1604–16010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flottorp S. A., Oxman A. D., Krause J., Musila N. R., Wensing M., Godycki-Cwirko M., Eccles M. P. (2013). A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: A systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implementation Science, 8, 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A. (2006). Pediatric Psychosocial Preventative Health Model (PPPHM): Research, practice, and collaboration in pediatric family systems medicine. Family Systems Health, 24, 381–395. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz J. T., Volkening L. K., Laffel L. M. B. (2014). Care utilization in a pediatric diabetes clinic: Cancellations, parental attendance, and mental health appointments. Journal of Pediatrics, 164, 1384–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris Z. S., Wooding S., Grant J. (2011). The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 104, 510–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models, and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10, 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B. J., Waltz T. J., Chinman M. J., Damschroder L. J., Smith J. L., Matthieu M. M., Kirchner J. E. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the expert recommendations for implementation change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science, 10, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E., Silmere H., Raghavan R., Hovmand P., Aarons G., Bunger A., Hensley M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38, 65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurman J. V., Gayes L. A., Slosky L., Hunter M. E., Pino F. A. (2015). Publishing quality improvement work in Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology: the “Why” and “How To”. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 3, 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D. D., Cline V. D., Axelrad M. E., Anderson J. (2011). Feasibility, acceptability, and predictive validity of a psychosocial screening program for children and youth newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 28, 186–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki T., Harris M. A., Buckloh L. M., Mertlich D., Lochrie A. S., Taylor A., White N. H. (2008). Randomized, controlled trial of behavioral family systems therapy for diabetes: maintenance and generalization of effect on parent-adolescent communication. Behavior Therapy, 39, 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarbro J. L., Mehlenbeck R. (2016). Financial analysis of behavioral health services in a pediatric endocrinology clinic. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41, 879–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zgibor J. C., Songer T. J. (2001). External barriers to diabetes care: Addressing personal and health systems. Diabetes Spectrum, 14, 23–28. [Google Scholar]