Abstract

Tropomyosin receptor kinase (Trk) inhibitors have shown high response rates in patients with tumors harboring NTRK fusions. We identified four NTRK fusion-positive uterine sarcomas that should be distinguished from leiomyosarcoma and undifferentiated uterine sarcoma. NTRK rearrangements were detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and/or targeted RNA or DNA sequencing in four undifferentiated uterine sarcomas with spindle cell morphology. Due to histologic overlap with leiomyosarcoma, TrkA and pan-Trk immunohistochemistry was performed in 97 uterine leiomyosarcomas. NTRK1 and NTRK3 FISH was performed on tumors with TrkA or pan-Trk staining. We also performed whole transcriptome RNA sequencing of a leiomyosarcoma with TrkA expression, and targeted RNA sequencing of two additional undifferentiated uterine sarcomas. FISH and/or targeted RNA or DNA sequencing in the study group showed TPM3-NTRK1, LMNA-NTRK1, RBPMS-NTRK3, and TPR-NTRK1 fusions. All tumors were composed of fascicles of spindle cells. Mitotic index was 7-30 mitotic figures per 10 high power fields; tumor necrosis was seen in two tumors. Desmin, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor were negative in all tumors, while pan-Trk was expressed in all tumors with concurrent TrkA staining in three of them. TrkA and/or pan-Trk staining was also seen six leiomyosarcomas, but these tumors lacked NTRK fusions or alternative isoforms by FISH or whole transcriptome sequencing. No fusions were detected in two undifferentiated uterine sarcomas. NTRK fusion-positive uterine spindle cell sarcomas constitute a novel tumor type with features of fibrosarcoma; patients with these tumors may benefit from Trk inhibition. TrkA and pan-Trk expression in leiomyosarcomas is rare and does not correlate with NTRK rearrangement.

Keywords: NTRK, uterine sarcoma, fibrosarcoma

INTRODUCTION

Undifferentiated uterine sarcoma is a rare malignant mesenchymal neoplasm that is currently recognized as a subcategory of endometrial stromal tumors by the World Health Organization 1. Although they were referred to as undifferentiated endometrial sarcomas in prior editions of the World Health Organization classification of endometrial stromal tumors 2, they lack any histologic resemblance to proliferative phase endometrial stroma and may not involve or arise from the endometrium. Instead, they typically consist of sheets of tumor cells with significant cytologic atypia, brisk mitotic activity, tumor necrosis, and destructive myometrial invasion. Undifferentiated uterine sarcoma is considered a diagnosis of exclusion after ruling out more common uterine mesenchymal tumors (including leiomyosarcoma and high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma) that have characteristic morphologic features, immunohistochemical profiles, or recurrent chromosomal translocations resulting in gene rearrangement.

Undifferentiated uterine sarcomas likely comprise a morphologically and genetically heterogeneous group of uterine mesenchymal neoplasms similar to undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma of the soft tissues3. While most if not all undifferentiated uterine sarcomas have a reportedly dismal prognosis, the scope of clinicopathologic studies describing the entity has been severely limited due to the rarity of this tumor type and likely contamination by morphologically high-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas harboring various genetic aberrations, particularly gene fusions that are distinct from low-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas 4,5. Prior studies suggested that undifferentiated uterine sarcomas may be separable into monomorphic and pleomorphic types by morphologic assessment6; the former is characterized by isomorphic tumor cells, while the latter consists of neoplastic cells with marked nuclear pleomorphism. At least a subset of undifferentiated uterine sarcomas with monomorphic phenotype and less commonly with pleomorphic histology is in fact high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma, such as those harboring YWHAE 5, BCOR 7,8, or SUZ12 9 gene rearrangements. However, only limited molecular data exist among undifferentiated uterine sarcomas, which appear to have complex karyotypes and harbor TP53 mutations in approximately 30% of cases 6,10.

Using a combination of next-generation targeted RNA and DNA sequencing as well as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) screening in the clinical work-up of undifferentiated uterine sarcomas, we identified four spindle cell sarcomas harboring recurrent NTRK gene rearrangements and exhibiting unique morphologic and immunophenotypic features allowing their distinction from leiomyosarcoma and undifferentiated uterine sarcoma. In this study, we define the clinicopathologic and molecular genetic features of this novel tumor type that expands the spectrum of fusion-positive uterine sarcomas as well as the variety of tumors harboring NTRK rearrangement. We also assess the frequency of TrkA and pan-Trk expression and NTRK gene rearrangement among uterine spindle cell leiomyosarcomas which represents the most important differential diagnosis in the assessment of these rare spindle cell sarcomas.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case Selection

From 2014 to 2017, four undifferentiated uterine sarcomas with spindle cell morphology and lacking known genetic abnormalities were prospectively identified on the Gynecologic Pathology Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY. Hematoxylin and eosin and immunohistochemical stained slides were reviewed to delineate the morphologic and immunophenotypic features by two pathologists with expertise in gynecologic and soft tissue pathology (S.C., C.R.A.). Clinical data were reviewed for demographics, presentation, treatment, and outcome. Unstained 5 μm slides of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) whole-tissue sections from each tumor were obtained for TrkA and pan-TRK immunohistochemistry, next-generation targeted RNA or DNA sequencing, and FISH.

Due to histologic overlap with leiomyosarcoma and undifferentiated uterine sarcoma, unstained 5 μm slides of triplicate 0.6 mm diameter core tissue microarrays of 97 FFPE uterine leiomyosarcomas and unstained 5 μm whole-tissue FFPE sections of two additional undifferentiated uterine sarcomas with spindle cell morphology and prominent myxoid stroma were obtained from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining for TrkA, TrkB, and TrkC expression and TrkA only was performed on the study cohort and tissue microarrays of leiomyosarcoma using a commercially available pan-Trk monoclonal antibody, clone EPR17341 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) at 6 μg/mL and a commercially available TrkA monoclonal antibody, clone (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) at 0.684 mg/mL, respectively. Staining was performed on a Leica-Bond-3 (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL) automated immunostaining platform using a heat-based antigen retrieval method and high pH buffer solution (ER2, Leica) as previously reported 11. Normal testis, ganglia, and brain tissues were used as positive controls. Results were interpreted independently by three pathologists (S.C., J.F.H., A.A.J.). Intensity (strong, moderate, weak, and negative) and estimated percentage of positive tumor cells were evaluated. Pan-Trk and TrkA immunohistochemistry was repeated on 5-μm whole tissue FFPE sections of leiomyosarcomas that showed any staining on the tissue microarray.

Targeted Massively Parallel Sequencing

In all four undifferentiated uterine sarcomas of the study cohort and two additional undifferentiated uterine sarcomas with spindle cell morphology and myxoid stroma, RNA was extracted from macrodissected FFPE tumor tissue mounted on charged glass slides and subjected to the Archer FusionPlex Custom Solid Panel, a next-generation targeted RNA-sequencing based assay utilizing the Anchored Multiplex PCR (AMP) technology 12. Unidirectional gene-specific primers were designed to several detect gene fusions and oncogenic isoforms in selected protein-coding exons of 62 genes and used in combination with adapter-specific primers to amplify known and novel fusion transcripts. Enriched amplicons were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq instrument.

For one of the undifferentiated uterine sarcomas in our study cohort for which normal tissue was available, DNA was extracted from macrodissected tumor and normal samples using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Tumor and matched germline DNA was subjected to the Memorial Sloan Kettering – Integrated Mutational Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT) sequencing assay targeting all exons and selected regulatory regions and introns of 468 key cancer genes on an Illumina HiSeq250013.

Whole Transcriptome RNA Sequencing

One uterine leiomyosarcoma showing TrkA-positivity by immunohistochemistry, for which sufficient RNA was available, was subjected to RNA sequencing. Total RNA was extracted from frozen tumor tissue using Rneasy Plus Mini (Qiagen), followed by mRNA isolation with oligo(dT) magnetic beads and fragmentation by incubation at 94 ºC in fragmentation buffer (Illumina) for 2.5 minutes. After gel size-selection (350 to 400 bp) and adapter ligation, the library was enriched by polymerase chain reaction for 15 cycles and purified. Paired-end RNA sequencing at read lengths of 50 or 51 bp was performed on an Illumina HiSeq2000 14.

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

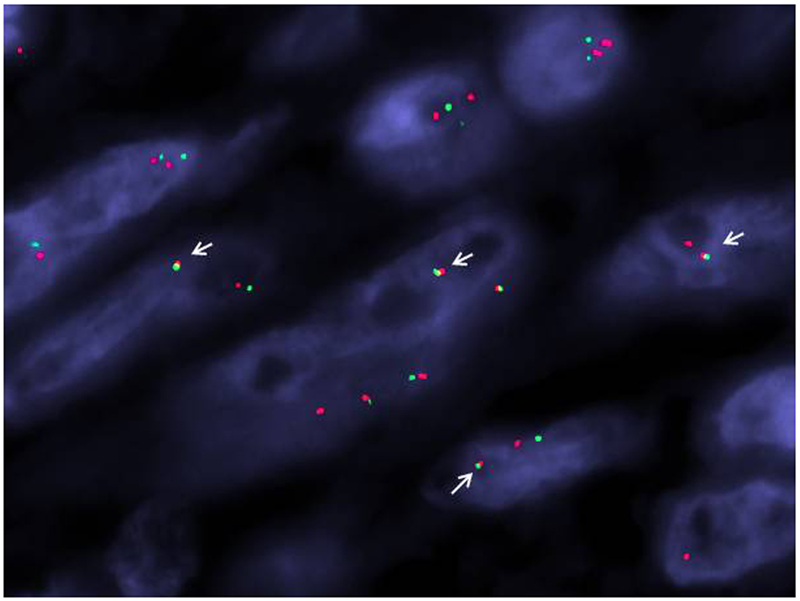

FISH was performed on interphase nuclei from FFPE tissue sections of three undifferentiated uterine sarcomas and all leiomyosarcomas with TrkA or pan-Trk expression. Custom probes using bacterial artificial chromosomes (BAC) flanking NTRK1, NTRK3, LMNA, TPR, and TPM3 genes were chosen according to the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu). BAC clones were retrieved from BACPAC sources of the Children’s Hospital of Oakland Research Institute (CHORI, Oakland, CA) (http://bacpac.chori.org) (Supplementary Table 1). The DNA from individual BACs were isolated according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, labeled with nick translation, and validated on normal metaphase chromosomes. Whole tissue 5 μm tumor sections mounted on charged slides were deparaffinized, pretreated, and hybridized with denatured probes overnight, followed by post-hybridization washes and counterstaining with DAPI. Slides were examined on a Zeiss fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplan, Oberkochen, Germany) using Isis 5 software (Metasystems). Two hundred tumor nuclei were counted, and gene rearrangement was confirmed if >20% of tumor nuclei demonstrated break-apart signals. As the NTRK1 gene on 1q25 is located in close proximity to its gene partners (LMNA, TPR and TPM3) on 1q21-23, we also applied a two color-fusion assay which can document the fusion with more confidence, as the standard break-apart assay may not be definitive due to the small gaps detected. Thus NTRK1 telomeric portion was labeled in green, while centromeric LMNA, TPR and TPM3 were labeled in red. A come-together signal (yellow), seen in >20% of tumor nuclei, was considered a positive result 14.

RESULTS

NTRK-fusion positive sarcomas affect premenopausal women with frequent cervical involvement

The four patients in our study cohort presented with a median age of 44 (range, 27-47) years and stage 1B disease using the 2009 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system for uterine sarcomas (Table 1). All patients presented with abnormal vaginal bleeding, three of whom had a large cervical mass upon pelvic examination. The remaining patient was found to have a fibroid uterus on pelvic ultrasound and a well-defined highly vascular intramural lesion without hemorrhage or necrosis on pelvic MRI. All four patients underwent total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. One patient had pulmonary lesions suspicious for metastases by imaging at the time of hysterectomy and was subsequently treated with gemcitabine and docetaxel. Seven months later, the patient developed progression of disease with a recurrence superior to the vagina by imaging. Another patient developed lung metastasis 12 months after initial presentation. She was treated with gemcitabine and docetaxel followed by doxorubicin, but developed new lung, pancreas, and brain metastases, and ultimately died of disease 78 months after initial presentation. The two remaining patients had no evidence of disease 11 and 2 months after initial presentation. None of the patients had a history of neurofibromatosis or prior radiation therapy.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the cohort.

| Case | Age, y | Signs and Symptoms | Disease Site | Stage | Treatment | Outcome, mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 46 | Vaginal bleeding | Cervix | 1B | Surgery, chemotherapy | Alive with disease, 7 |

| 2 | 27 | Fibroid uterus | Corpus | 1B | Surgery | No evidence of disease, 11 |

| 3 | 47 | Vaginal bleeding | Cervix | 1B | Surgery, chemotherapy | Died of disease, 78 |

| 4 | 42 | Vaginal bleeding | Cervix | 1B | Surgery | No evidence of disease, 2 |

NTRK-fusion positive sarcomas have unique spindle cell morphology and immunophenotype

Tumor size ranged from 2.6 to 16.3 cm, with a median of 11.7 cm. Three tumors were based in the cervix. Two of them were polypoid, tan-yellow, and necrotic lesions extending through the external os and confined to the cervix; the other was well-circumscribed, whorled, and tan-pink with limited extension into the lower uterine segment. The remaining tumor consisted of a tan-white whorled nodule within the myometrium and was confined to the corpus.

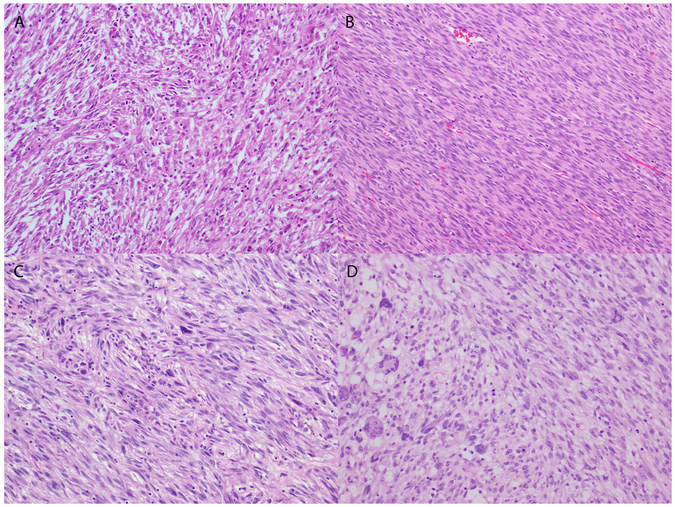

The tumor border was evaluable in two cases, and was pushing (n=1) and irregularly infiltrative (n=1). All four tumors consisted of haphazard fascicles of spindle cells with intermediate-sized nuclei, clumped chromatin, small nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Table 2, Figure 1). One of the tumors also showed numerous foci of spindle cells with marked nuclear pleomorphism and smudgy chromatin (Figure 1). The stroma was edematous in one tumor and focally myxoid in another. Three of the tumors demonstrated delicate, thin-walled vasculature, while the remaining tumor with marked pleomorphism exhibited large, thick-walled blood vessels. Tumor necrosis was present in two of four tumors. Lymphovascular invasion was not seen in any of the four tumors. Mitotic activity was brisk in all tumors, ranging from 7 to 30 mitotic figures per 10 high power fields with a median of 13.5 mitotic figures per 10 high power fields.

Table 2.

Gross, morphologic, and immunophenotypic features of the cohort.

| Gross and Morphologic features | Immunohistochemical profile | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Size, cm | Atypia | Necrosis | LVI | MI | Desmin | SMA | ER | PR | CD34 | S100 | SOX10 | H3K27me3 |

| 1 | 9.3 | Moderate | Present | Absent | 15 | Neg | Pos (F) | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos (R) | Neg | Pos |

| 2 | 16.3 | Moderate | Absent | Absent | 7 | Neg | Pos (F) | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos (R) | Neg | Pos |

| 3 | 14.0 | Moderate | Present | Absent | 12 | Neg | Pos(F) | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos (R) | Neg | Pos |

| 4 | 2.6 | Severe | Absent | Absent | 30 | Neg | Pos (F) | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos (R) | Neg | Pos |

ER indicates estrogen receptor; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; MI, mitotic index (# of mitotic figures/10 high power fields); PR, progesterone receptor; SMA, smooth muscle actin.

Figure 1.

Morphologic features of four NTRK fusion-positive uterine sarcomas. A) Haphazard fascicles of spindle cells arranged in a storiform pattern and associated with scattered lymphocytes. Herringbone pattern of spindle cells with mild nuclear atypia in one tumor (B) and rare pleomorphic cells in another (C). D) Spindle cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia forming fascicles (right) adjacent to cells with marked pleomorphism and multinucleation.

All four tumors showed focal SMA staining, but absent desmin, estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) expression. S100 was focally positive in <10% of cells in all four tumors, but negative for SOX10 (Table 2). CD34 staining was negative, while H3K27me3 expression was retained in all tumors. CD10 was performed in three tumors and was focally positive in two and negative in one other. Pan-cytokeratin was also performed in three tumors and was negative.

Two tumors were initially classified as leiomyosarcoma despite the absence of desmin expression. The other two were diagnosed as undifferentiated uterine sarcoma.

Uterine sarcomas with NTRK rearrangement have various fusion partners and demonstrate TrkA and/or pan-Trk expression

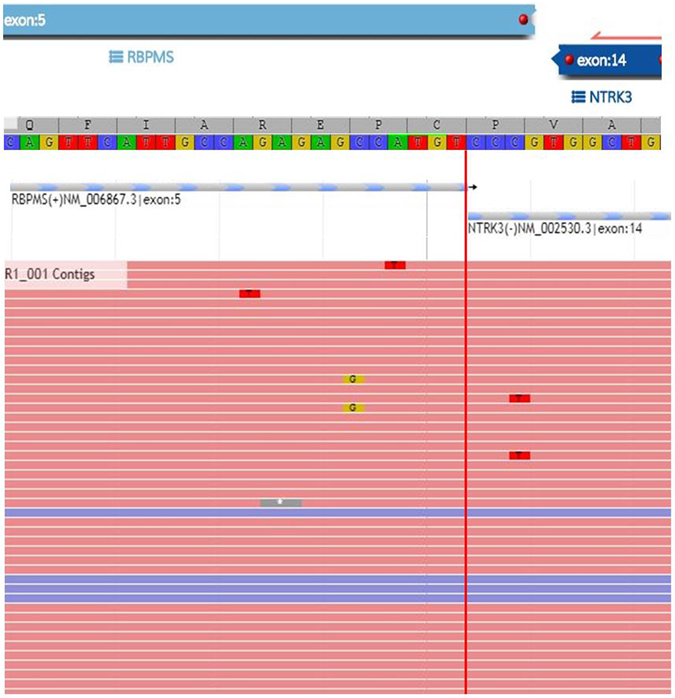

RBPMS-NTRK3, TPR-NTRK1, LMNA-NTRK1, and TPM3- NTRK1 gene fusions were detected in four tumors by targeted RNA sequencing (Table 2, Figure 2). The TPR-NTRK1 fusion was also confirmed by targeted DNA sequencing in one tumor, while the other fusions in the three remaining tumors were confirmed by FISH (Figure 3). No fusions were detected in two additional undifferentiated uterine sarcomas with spindle cell morphology and prominent myxoid stroma.

Figure 2.

Confirmation of RBPMS-NTRK3 fusion in a uterine sarcoma by targeted RNA sequencing.

Figure 3.

LMNA-NTRK1 gene fusion demonstrated by FISH. A two-color fusion assay was applied showing the NTRK1 (green, telomeric) and LMNA (red, centromeric) signals come together as a yellow fused signal (white arrows).

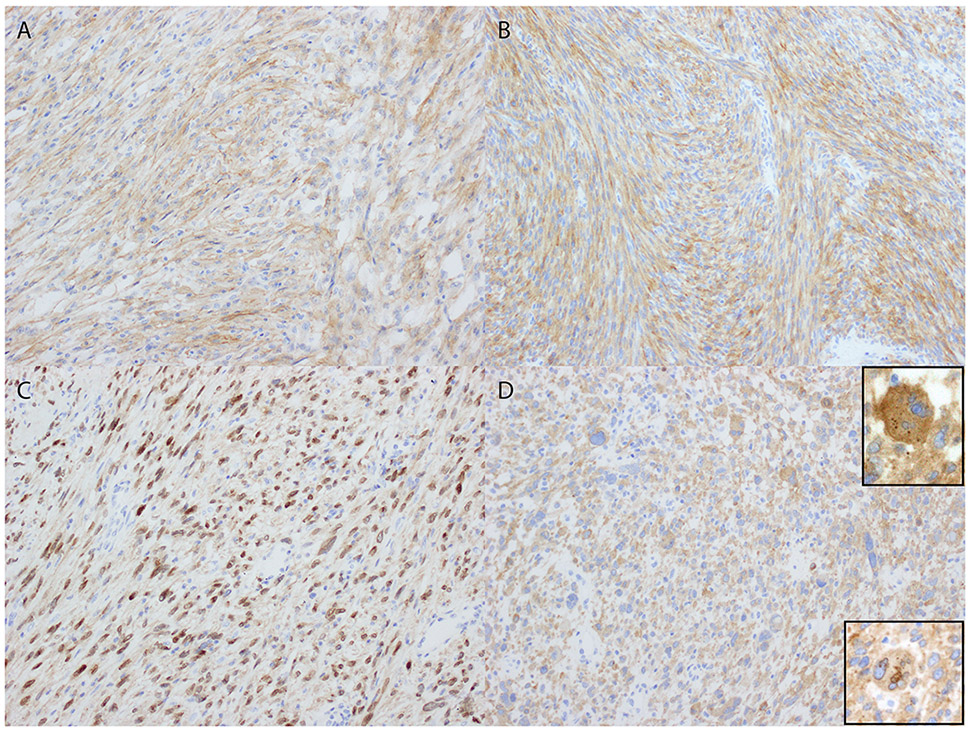

TrkA expression was diffuse, defined as >95% of cells staining, with weakly cytoplasmic and strongly perinuclear staining in the tumor harboring LMNA-NTRK1 fusion (Figure 4). There was strong and diffuse cytoplasmic TrkA staining in the tumor harboring TPM3-NTRK1 fusion. Pan-Trk expression was strong and diffuse with mostly cytoplasmic staining and dot-like aggregates as well as rare nuclear staining and accentuation of the nuclear envelope in the tumor harboring TPR-NTRK1 fusion. The tumor with RBPMS-NTRK3 fusion showed diffuse moderate to strong cytoplasmic pan-Trk expression.

Figure 4.

Trk expression patterns in uterine sarcomas with NTRK gene rearrangement. A and B) Diffuse cytoplasmic TrkA and pan-Trk expression in tumors with TPM3-NTRK1 and RBPMS-NTRK3 fusions, respectively. C) Weakly cytoplasmic and strongly perinuclear staining in the tumor harboring LMNA-NTRK1 fusion. D) Strong and diffuse pan-Trk expression with mostly cytoplasmic and dot-like aggregates (top inset) as well as rare nuclear staining accentuation of the nuclear envelope (bottom inset) in the tumor harboring TPR-NTRK1 fusion.

TrkA and pan-Trk expression may be seen in a subset of NTRK fusion-negative leiomyosarcomas

Among 97 uterine spindle cell leiomyosarcomas, only four showed weak and diffuse cytoplasmic TrkA staining, while two showed strong and diffuse cytoplasmic pan-Trk expression on both tissue microarray and whole tissue sections; the remaining tumors were negative for both TrkA and pan-Trk expression. No NTRK rearrangements were detected by FISH in any of the leiomyosarcomas demonstrating TrkA or pan-Trk immunoreactivity. In addition, no NTRK rearrangements or novel isoforms were detected by whole transcriptome sequencing of one of the TrkA-positive tumors for which frozen tumor tissue was available.

DISCUSSION

We report for the first time the presence of NTRK gene rearrangements in a subset of undifferentiated uterine sarcomas with fibrosarcoma-like morphology. All four tumors in our cohort occurred in premenopausal women with a median age of 44 years who presented with abnormal vaginal bleeding. All had FIGO stage 1B disease with three tumors arising in the cervix and one in the corpus; two patients recurred 7 and 12 months after initial presentation, one of whom died of disease. All four tumors shared distinct morphologic features of relatively monomorphic spindle cells with focal and moderate nuclear pleomorphism arranged in long intersecting fascicles; one tumor also showed scattered foci of marked nuclear pleomorphism. Mitotic activity was brisk in all tumors with tumor necrosis present in two. While focal SMA expression was seen in all tumors, desmin, ER and PR were consistently negative in all. S100 was focally positive in all tumors, but all lacked SOX10 and CD34 expression; H3K27me3 expression was retained in all tumors. All tumors expressed either TrkA or pan-Trk by immunohistochemistry.

The tropomyosin receptor kinase (Trk) family includes TrkA, TrkB, and TrkC proteins which are encoded by Neurotrophic Tyrosine Kinase Receptors NTRK1, NTRK2 and NTRK3 genes, respectively 15,16. Binding of neurotrophins to Trk proteins induces receptor dimerization, phosphorylation, and activation of the downstream signaling cascades via PI3K, RAS/MAPK/ERK, and PLC-gamma 17. Trk pathway aberrations, including gene fusions, protein overexpression, and single nucleotide alterations, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of many human cancers, with NTRK gene fusions being the most commonly validated oncogenic events to date. NTRK gene fusions are infrequent among most common cancers, such as lung and colorectal carcinomas in which the prevalence of the NTRK rearrangements is well below 5% 18. However, certain rare tumor types are characterized by NTRK fusions. Among soft tissue sarcomas, ETV6-NTRK3 fusions and NTRK1 gene rearrangements appear to define the vast majority of infantile fibrosarcomas 19 and lipofibromatosis-like neural tumors 14, respectively. Interestingly, rare NTRK3-negative infantile fibrosarcomas have been reported to instead harbor NTRK1 gene rearrangements 20,21, suggesting that oncogenic activation of various NTRK genes through chromosomal translocations are involved interchangeably in the pathogenesis of certain soft tissue sarcomas. This phenomenon has also been observed among our cohort of uterine sarcomas in which three tumors showed NTRK1 fusion with various gene partners, while one tumor harbored an NTRK3 gene rearrangement.

NTRK rearrangements appear to underpin a subset of high-grade uterine sarcomas with spindle cell morphology. We identified a novel RBPMS-NTRK3 fusion in a uterine sarcoma that has not been previously reported in other tumor types with NTRK rearrangement. Among tumors with NTRK1-related fusions, there are numerous gene partners involved, with three in particular emerging as recurrent, such as TPR, TMP3 and LMNA, all located on the long arm of chromosome 1 (1q21-q23), in the vicinity of NTRK1. Based on reported NTRK fusion-positive tumors to date, the NTRK1 breakpoints include exon 9 (TPM3-NTRK1 or TPR-NTRK1) or exon 12 (LMNA-NTRK1)14. Among the uterine sarcomas with NTRK1 rearrangements, breakpoints include exon 10 (TPR-NTRK1) and exon 12 (LMNA-NTRK1). Despite the variability in genomic breakpoints and fusion transcripts, all reported cases to date, including our cohort of uterine sarcomas, retain the full-length coding sequence of the tyrosine kinase domain of NTRK1 (exons 13-17) and NTRK3 (exons 13-18). This is further confirmed in our study group by TrkA or pan-Trk protein overexpression in all tumors, regardless of the NTRK1 and NTRK3 breakpoint and gene partner, since the TrkA and pan-Trk antibodies bind to portions of TrkA and TrkC retained in the fusions. A recent study from our group suggested that pan-Trk immunoreactivity is associated with a fusion partner-specific pattern of staining, with cytoplasmic expression and nuclear membrane accentuation in tumors with LMNA-NTRK1 fusions and cellular membrane accentuation in all TPM3/4 fusions, while half of tumors with ETV6-NTRK3 fusions display nuclear staining 11. While cytoplasmic and nuclear membrane TrkA staining was seen in one of our tumors with LMNA-NTRK1 fusion, only cytoplasmic TrkA and pan-Trk expression was present in the tumors harboring TPM3-NTRK1 and RBPMS-NTRK3 fusions, respectively.

It is notable that two of our tumors were initially considered high-grade leiomyosarcoma based on the spindle cell morphology and limited myogenic differentiation by immunohistochemistry. Since leiomyosarcoma is the most common uterine malignant mesenchymal tumor, this remains an important differential diagnostic consideration when assessing atypical spindle cell neoplasms of the uterus. All of our tumors showed morphologic features that were unusual for leiomyosarcoma; while there was brisk mitotic activity with more than 10 mitotic figures per 10 high power fields in three of our lesions, the cytologic atypia was only mild to moderate in most tumors, and tumor necrosis was seen in only two. Our tumors also consisted of haphazard fascicles of spindle cells, while the fascicles of leiomyosarcoma appear uniform, often crossing at 90-degrees. These unusual morphologic features prompted immunohistochemistry in all four sarcomas. All expressed only focal SMA without evidence of desmin expression. In addition, all of them lacked ER and PR expression which is found in approximately 40% of high grade uterine leiomyosarcomas 22. While immunohistochemistry is not routinely used for the diagnosis of uterine spindle cell leiomyosarcoma, our findings raise the possibility that some tumors diagnosed as leiomyosarcoma may in fact represent NTRK fusion-positive sarcomas. Although TrkA and/or pan-Trk expression was seen in only 6% of uterine spindle cell leiomyosarcomas, none of them harbored underlying genetic abnormalities involving NTRK genes. While TrkA and pan-Trk expression is present in normal smooth muscle and may account for the staining seen in leiomyosarcoma, it is unclear why only a small subset of tumors shows immunoreactivity. This highlights a potential pitfall in using TrkA or pan-Trk immunohistochemistry alone, and fusion status must be confirmed in all tumors with Trk expression. Our findings also suggest that in the absence of desmin expression in any uterine spindle cell sarcoma, the diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma should be reconsidered, and NTRK fusion-positive sarcoma must be clinically excluded by immunohistochemistry and if positive, FISH, targeted DNA or RNA sequencing, or RT-PCR confirmation of the fusion status.

Our tumors bear some morphologic and immunohistochemical resemblance to rare cervical lesions described as endocervical fibroblastic malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor or neurofibrosarcoma that reportedly showed focal S100 and CD34 positivity, but lacked desmin, SOX10, ER, and PR expression 23. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor does not typically show the degree of cytologic atypia seen in one of our tumors and two of the previously reported neurofibrosarcomas. The absence of SOX10 staining along with retained H3K27me3 expression is also unusual, the latter particularly in sporadic and radiation-associated cases 24. Based on the spindle cell morphology and immunophenotype, along with insufficient evidence for peripheral nerve sheath derivation, we propose classifying these tumors as NTRK fusion-positive uterine spindle cell sarcomas.

While our study cohort of NTRK fusion-positive uterine sarcomas is limited, it is notable that all four tumors arose in premenopausal women with an increased incidence of cervical involvement. The trend towards disease presentation at a young age in our tumors contrasts with that of uterine leiomyosarcoma as well as low- and high-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas in which the average age at presentation is 55.4, 48, and 59 years 25,26. The clinical behavior of NTRK fusion-positive uterine sarcomas is uncertain based on only four cases in our small cohort; however, all patients presented to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center at the time of primary diagnosis, and two patients recurred despite optimal surgical resection at 7 and 12 months after initial presentation, one of whom died of disease, indicating the clinically aggressive behavior of these sarcomas. Several Trk-targeting compounds are currently in clinical development with two leading Trk inhibitors, larotrectinib and entrectinib, in ongoing clinical trials, with promising results 27. Patients with NTRK fusion-positive uterine sarcomas who develop progressive disease may benefit from enrollment in clinical trials with Trk inhibition. Since NTRK fusion-positive uterine sarcomas appear to affect premenopausal women, early identification of NTRK fusions in limited tissue samples also raises the possibility for neoadjuvant Trk inhibition in the setting of fertility preservation.

Our results reveal a novel subset of high-grade uterine sarcomas with features reminiscent of soft tissue fibrosarcoma and characterized by oncogenic activation of Trk through recurrent NTRK gene fusions, certifying these lesions as a unique clinicopathologic entity. Based on their morphologic features, we propose classifying these tumors as NTRK-fusion positive uterine spindle cell sarcomas, distinct from more common malignant mesenchymal neoplasms such as leiomyosarcoma. Evaluation of Trk expression and NTRK fusion status in these tumors may allow patients to benefit from enrollment in clinical trials for selective inhibition of Trk signaling.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Kurman RJ, Carcangiu M, Herrington CS, et al. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs. Lyon, France: WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Genest DR, Berkowitz RS, Fisher RA, et al. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours, Pathology and Genetics, Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollowood K, Fletcher CD. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: morphologic pattern or pathologic entity? Semin Diagn Pathol 1995;12:210–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sciallis AP, Bedroske PP, Schoolmeester JK, et al. High-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas: a clinicopathologic study of a group of tumors with heterogenous morphologic and genetic features. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38:1161–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gremel G, Liew M, Hamzei F, et al. A prognosis based classification of undifferentiated uterine sarcomas: identification of mitotic index, hormone receptors and YWHAE-FAM22 translocation status as predictors of survival. Int J Cancer 2015;136:1608–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurihara S, Oda Y, Ohishi Y, et al. Endometrial stromal sarcomas and related high-grade sarcomas: immunohistochemical and molecular genetic study of 31 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:1228–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoang LN, Aneja A, Conlon N, et al. Novel High-grade Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma: A Morphologic Mimicker of Myxoid Leiomyosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41:12–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiang S, Lee CH, Stewart CJR, et al. BCOR is a robust diagnostic immunohistochemical marker of genetically diverse high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma, including tumors exhibiting variant morphology. Mod Pathol 2017;30:1251–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koontz JI SA, Nucci M, Kuo FC et al. Frequent fusion of the JAZF1 and JJAZ1 genes in endometrial stromal tumors. PNAS 2001;98:6348–6353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halbwedl I, Ullmann R, Kremser ML, et al. Chromosomal alterations in low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma and undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma as detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Gynecol Oncol 2005;97:582–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hechtman JF, Benayed R, Hyman DM, et al. Pan-Trk Immunohistochemistry is an Efficient and Reliable Screen for the Detection of NTRK Fusions. Am J Surg Pathol 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng Z, Liebers M, Zhelyazkova B, et al. Anchored multiplex PCR for targeted next-generation sequencing. Nat Med 2014;20:1479–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A Hybridization Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Clinical Assay for Solid Tumor Molecular Oncology. J Mol Diagn 2015;17:251–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agaram NP, Zhang L, Sung YS, et al. Recurrent NTRK1 Gene Fusions Define a Novel Subset of Locally Aggressive Lipofibromatosis-like Neural Tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:1407–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan DR, Martin-Zanca D, Parada LF. Tyrosine phosphorylation and tyrosine kinase activity of the trk proto-oncogene product induced by NGF. Nature 1991;350:158–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbacid M Structural and functional properties of the TRK family of neurotrophin receptors. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1995;766:442–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Neurotrophin signal transduction in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2000;10:381–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khotskaya YB, Holla VR, Farago AF, et al. Targeting TRK family proteins in cancer. Pharmacol Ther 2017;173:58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knezevich SR, McFadden DE, Tao W, et al. A novel ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion in congenital fibrosarcoma. Nat Genet 1998;18:184–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kao YC, Fletcher CDM, Alaggio R, et al. Recurrent BRAF Gene Fusions in a Subset of Pediatric Spindle Cell Sarcomas: Expanding the Genetic Spectrum of Tumors With Overlapping Features With Infantile Fibrosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong V, Pavlick D, Brennan T, et al. Evaluation of a Congenital Infantile Fibrosarcoma by Comprehensive Genomic Profiling Reveals an LMNA-NTRK1 Gene Fusion Responsive to Crizotinib. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leitao MM Jr., Hensley ML, Barakat RR, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors and outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed uterine leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol 2012;124:558–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mills AM, Karamchandani JR, Vogel H, et al. Endocervical fibroblastic malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (neurofibrosarcoma): report of a novel entity possibly related to endocervical CD34 fibrocytes. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:404–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prieto-Granada CN, Wiesner T, Messina JL, et al. Loss of H3K27me3 Expression Is a Highly Sensitive Marker for Sporadic and Radiation-induced MPNST. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:479–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosh M, Antar S, Nazzal A, et al. Uterine Sarcoma: Analysis of 13,089 Cases Based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2016;26:1098–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seagle BL, Shilpi A, Buchanan S, et al. Low-grade and high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: A National Cancer Database study. Gynecol Oncol 2017;146:254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyman DM, Kummar S, Dubois SG, et al. The efficacy of larotrectinib (LOXO-101), a selective tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) inhibitor, in adult and pediatric TRK fusion cancers [abstract] . American Society for Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. Chicago, IL: ASCO, April 2-6, 2017. Abstract no LBA2501. 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.