Abstract

Eukaryotic cells have developed sophisticated mechanisms to ensure the integrity of the genome and prevent the transmission of altered genetic information to daughter cells. If this control system fails, accumulation of mutations would increase risk of diseases such as cancer. Ubiquitylation, an essential process for protein degradation and signal transduction, is critical for ensuring genome integrity as well as almost all cellular functions. Here, we investigated the role of the SKP1–Cullin-1–F-box protein (SCF)-[F-box and tryptophan-aspartic acid (WD) repeat domain containing 7 (FBXW7)] ubiquitin ligase in cell proliferation by searching for targets implicated in this process. We identified a hitherto-unknown FBXW7-interacting protein, p53, which is phosphorylated by glycogen synthase kinase 3 at serine 33 and then ubiquitylated by SCF(FBXW7) and degraded. This ubiquitylation is carried out in normally growing cells but primarily after DNA damage. Specifically, we found that SCF(FBXW7)-specific targeting of p53 is crucial for the recovery of cell proliferation after UV-induced DNA damage. Furthermore, we observed that amplification of FBXW7 in wild-type p53 tumors reduced the survival of patients with breast cancer. These results provide a rationale for using SCF(FBXW7) inhibitors in the treatment of this subset of tumors.—Galindo-Moreno, M., Giráldez, S., Limón-Mortés, M. C., Belmonte-Fernández, A., Reed, S. I., Sáez, C., Japón, M. Á., Tortolero, M., Romero, F. SCF(FBXW7)-mediated degradation of p53 promotes cell recovery after UV-induced DNA damage.

Keywords: ubiquitylation, proliferation, cancer, FBXW7 inhibitors

Protein degradation plays an essential role in maintaining cellular homeostasis. For that reason, its deregulation is associated with many pathologies, including tumorigenesis. The ubiquitin system controls the stability of innumerable proteins that are degraded by the proteasome or lysosome (1). Ubiquitylation requires the concerted action of 3 enzymes: ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2), and ubiquitin ligase (E3). E3s are responsible for substrate recognition (2). The mammalian genome encodes ∼1000 E3s. Among them, the anaphase-promoting complex or cyclosome and the S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 (SKP1)–Cullin-1–F-box protein (SCF) complex are the 2 main E3s involved in cell-cycle regulation (3). The F-box protein is the subunit of the SCF complex responsible for recruiting substrates. β-transducin repeat-containing protein (β-TrCP), F-box and tryptophan-aspartic acid (WD) repeat domain containing 7 (FBXW7), and S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (SKP2) are the best-characterized of these.

In mammalian cells, there are 3 FBXW7 isoforms, FBXW7-α, FBXW7-β, and FBXW7-γ, that have distinct patterns of subcellular localization. FBXW7-α is nucleoplasmic, FBXW7-β is cytoplasmic, and FBXW7-γ is nucleolar (4). FBXW7 is ubiquitously expressed (5) and targets multiple oncoproteins for proteolysis, such as cyclin E, c-JUN, c-MYC, myeloid cell leukemia 1 (MCL1), polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1), or notch (6). Therefore, it is considered an important tumor suppressor. In fact, FBXW7 is one of the most commonly mutated genes in cancer. It is frequently mutated in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, colorectal adenocarcinoma, uterine carcinosarcoma and endometrial carcinoma, and bladder carcinoma but also in stomach adenocarcinoma and lung, cervical, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (7). Approximately 6% of 1556 human cancers analyzed had inactivating mutations in FBXW7 (8). FBXW7 recognizes phosphorylated motifs, known as cell division control protein 4 (CDC4)-phosphodegrons (CPDs), within their substrates. The CPD consensus motif is (L)-X-pT/pS-P-(P)-X1-2{X≠K/R}-pT/pS/E/D, where X represents any amino acid (9–11). Frequently, glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) is responsible for phosphorylation of this motif, creating an FBXW7 binding site, thereby allowing ubiquitylation and degradation of substrates (12). In addition, FBXW7 dimerizes, which is especially important for those substrates with noncanonical phosphodegrons (13).

We previously reported a search for new SCF(FBXW7) substrates by identifying FBXW7-interacting proteins using tandem mass spectrometry (14). We found that PLK1 is ubiquitylated and degraded by SCF(FBXW7) and the proteasome, respectively. Interestingly, we showed that after DNA damage in S phase, FBXW7-induced PLK1 degradation impedes the formation of prereplication complexes required for DNA replication (15), thus preventing cell proliferation. Our results suggested that the tumor-suppressor function of FBXW7 might be related, at least in part, to its role in control of PLK1 levels.

In the current study, we continue our investigation of the role of FBXW7 in cell proliferation, specifically in the recovery from cell-cycle arrest caused by DNA damage. We found that SCF(FBXW7) promotes cell proliferation by reducing protein levels of tumor-suppressor p53 after DNA damage–induced long-term arrest. SCF(FBXW7)-dependent degradation of p53 is mediated by GSK3 phosphorylation. We show that this decrease in p53 levels results in increased proliferation as well as a reduction in cell death. Finally, we present evidence showing that FBXW7 status has potential consequences for patients with cancer because of this regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids, cloning, point mutations, and sequencing

Plasmids pFlagCMV2-FBXW7, pCMVHA-FBXW7, pCMVHA-FBXW7ΔF, pCS2HA-β−TrCP, pRcCMVhp53, pLexA-RasV12, pGAD-Raf, and empty vectors have been previously described (14, 16–20). p–enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-N1 and pCW7 (pRG4Myc-Ub) were from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA), respectively. pFlagCMV2-p53, pCMVHA-p53, pCMVHA-p53 S33G, and the 2-hybrid vectors pLex10-FBXW7 and pGAD-p53 were obtained by cloning the corresponding PCR fragments in pFlagCMV2, pCMVHA, pLex10, and pGAD-GH, respectively. p53 S33G, p53 S46A, p53 T81A, p53 S149A/T150A, and p53 L14Q/F19G were constructed using the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA, USA). The sequences of constructs and point mutations were verified on both strands with an automatic sequencer.

Yeast 2-hybrid methods

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain L40 was cotransformed with the indicated plasmids by the lithium acetate method (20). Double transformants were plated on yeast drop-out medium lacking Trp and Leu. They were grown for 3 d at 30°C, and then colonies were patched on the same medium and replica-plated on Whatman 40 filters to test for β-galactosidase activity (21) and on yeast drop-out medium lacking Trp, Leu, and His. Plasmids pLexA-RasV12 and pGAD-Raf carrying proteins that interact with each other were used as controls (20).

Cell culture, transient transfections, drugs, and cell lysis

Routinely, Cos7, U2OS, and HEK293T [from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC)] were grown in DMEM (BioWest, Nuaillé, France) as previously described by Romero et al. (22). HCT116, HCT116FBXW7−/−, DLD1 and DLD1FBXW7−/− (23), and HCT116p53−/− (24) were grown in McCoy’s 5A medium (BioWest) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 U/ml penicillin from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). DNA constructs were transiently transfected by electroporation or by using a lipid transfection reagent (Xfect; Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan). Cells were harvested and lysed 18 or 48 h post-transfection, respectively. Where appropriate, transfected cells were retransfected with other plasmids. In indicated experiments, cells or extracts were pretreated with cycloheximide (50 μg/ml; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA), Nutlin 3a (20 μM; MilliporeSigma), LiCl (100 mM; MilliporeSigma), CHIR99021 (10 μM; MilliporeSigma), or GSK3-β inhibitor VII (100–200 μM; MilliporeSigma; Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) and harvested at various times.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared at 4°C in 420 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1% Nonidet P-40 (NP40), 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml chymostatin for 20 min. Extracts were centrifuged at 20,000 g for 20 min and supernatants frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Knockdown experiments

Cells were transfected with FBXW7-α or GSK3-α and β–small interfering RNA (siRNA) (25–27) using the oligofectamine method (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to suppress the expression of endogenous genes. EGFP-siRNA (25) was used as a nonspecific control. Cells were harvested 48 h post-transfection and the reduction of protein levels confirmed by Western blotting.

Electrophoresis, Western blot analysis, and antibodies

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and gels were electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes and probed with the following antibodies: anti–hemagglutinin (HA)-peroxidase mAb (Roche, Basel, Switzerland); anti–cyclin E, anti-murine double minute 2 (MDM2), anti-p53, and anti–GSK3-α and -β mAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA); anti–α-tubulin and anti-Flag mAb (MilliporeSigma); anti-GFP pAb (Immune Systems, Paignton, United Kingdom); anti–GSK3-β and anti-poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) mAb (BD Biosciences); anti-PLK1 mAb (MilliporeSigma); anti–p-p53 (Ser33) mAb (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom); and anti–p-GSK3-β (Ser9) and anti–cleaved caspase-3 mAb (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Peroxidase-coupled donkey anti-rabbit IgG and sheep anti-mouse IgG were obtained from GE Healthcare (Waukesha, WI, USA). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using the ECL Western blotting system (ECL; GE Healthcare).

Coimmunoprecipitation experiments

Whole-cell extracts from transfected cells diluted to 150 mM NaCl (1–2 mg) were incubated with normal mouse serum (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 30 min and subsequently with protein G sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) for 1 h at 4°C. After centrifugation, the beads were discarded and the supernatants incubated for 2 h with anti-p53 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti-Flag (MilliporeSigma) mouse mAb followed by protein G sepharose beads for 1 h. Alternatively, the supernatants were incubated with normal mouse serum. Beads were washed, and bound proteins were solubilized by the addition of SDS sample buffer heated at 95°C for 5 min.

In vitro and in vivo ubiquitylation assays

The in vitro ubiquitylation of p53 was performed in a volume of 10 μl containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 5 mM MgCl2, 0.6 mM DTT, 2 mM ATP, 2 μl in vitro–transcribed and –translated unlabeled F-box protein, 1.5 ng/μl E1 (His6-E1; Boston Biochem, Cambridge, MA, USA), 10 ng/μl His6-UbcH3 (E2; Boston Biochem), 10 ng/μl UbcH5a (E2; Boston Biochem), 2.5 μg/μl ubiquitin (MilliporeSigma), 1 μM ubiquitin aldehyde (Boston Biochem), and 1 μl [35S]-methionine–labeled in vitro–transcribed and –translated p53 as substrate. The reactions were incubated at 30°C for 1 h and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. For some experiments, the unlabeled F-box protein was substituted by a recombinant SCF(FBXW7) complex expressed in Sf21 insect cells.

The in vivo ubiquitylation experiments were performed in Cos7 cells transfected and treated with MG132 4 h before harvesting. Cells were washed in PBS, lysed at 95°C for 15 min in NP40 buffer (28) supplemented with 5% SDS and 10 mM iodoacetamide, and diluted in NP40 buffer supplemented with 10 mM iodoacetamide. Flag-p53 was immunoprecipitated, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, electroblotted, and probed with different antibodies.

In vitro kinase assay

In vitro–transcribed and –translated HA-p53 and HA-p53 S33G were incubated in the presence or absence of human recombinant GSK3-β (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with ATP 200 μM and GSK3-β buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 100 μM Na3VO4, and 2 mM DTT] for 30 min at 30°C. For some experiments, GSK3-β inhibitor VII was previously added. Reactions were terminated by adding SDS sample buffer, and proteins were analyzed by Western blot.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were cultured in 6-cm dishes at 5 × 105 cells per plate with the appropriate medium to ensure exponential growth for duration of the assay. After 24 h, cells were UV irradiated (60 J/m2, 254 nm) and harvested at the indicated times. The amount of protein in the extracts, quantified by the Bradford assay, was taken as a parameter to measure cell proliferation. Experiments were performed independently at least 3 times.

Crystal violet assay

Briefly, transfected cells were seeded in 6-well plates and, after 24 h, irradiated. At the indicated times, cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet solution in methanol for 20 min. After washing and air drying, stained cells were incubated with methanol for 20 min and absorbance at 570 nm measured with a plate reader. All assays were carried out in triplicate.

Patient dataset collection

Patients’ clinical data and copy number alterations of genes were downloaded from cBioPortal database (https://www.cbioportal.org/) [The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/ccg/research/structural-genomics/tcga) and Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium (METABRIC; http://molonc.bccrc.ca/aparicio-lab/research/metabric) for breast invasive carcinoma and breast cancer, respectively, TCGA and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center for bladder cancer, and TCGA for skin cutaneous melanoma] (29, 30) and are freely available. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical details of experiments (number of biologic replicates and use of sd) are included in the Figure Legends. Statistical analyses were done with unpaired Student’s t tests. Significance is indicated in figures as P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001.

Survival curves were calculated by the method of Kaplan and Meier. The comparison of the survival curves was done by the log-rank test of Mantel and Cox. Differences of P < 0.05 were considered significant. Calculations were performed using Prism 6.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA).

RESULTS

p53 is a substrate for SCF(FBXW7) E3

To find new SCF(FBXW7) substrates, we previously immunoprecipitated epitope-tagged FBXW7 and identified coprecipitating proteins using mass spectrometry (14). Among the peptides identified, 3 were unique peptides corresponding to p53 not present in control samples from nonimmune IgG immunoprecipitation (Fig. 1A). To verify the FBXW7-p53 interaction, we confirmed the presence of p53 within Flag-FBXW7 immunocomplexes by Western blot assay (Fig. 1B). Moreover, reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation analysis showed that Flag-FBXW7 also coprecipitated with endogenous p53 (Fig. 1C). Next, we cloned full-length human FBXW7 and TP53 cDNAs into 2-hybrid vectors to analyze this interaction in yeast, in which indirect association is less likely (31). Growth in the absence of histidine and expression of β-galactosidase activity indicated that FBXW7 interacts directly with p53 (Fig. 1D). Finally, we studied the E3 activity of SCF(FBXW7) on p53 both in vitro using reticulocyte extracts (Fig. 1E) or proteins produced in Sf21 insect cells (Fig. 1F) and in vivo (Fig. 1G). In all 3 cases, p53 was specifically ubiquitylated by SCF(FBXW7). Therefore, our data show that p53 is a substrate of SCF(FBXW7).

Figure 1.

Identification of p53 as a substrate of SCF(FBXW7). A) Amino acid sequence of p53 with matching peptides by mass spectrometry marked in yellow. B) Cos7 cells were transiently transfected with pFlagCMV2-FBXW7 and whole-cell extracts immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag mAb or normal mouse serum (PI). Immunoprecipitates materials were analyzed by Western blotting. Lys: whole-cell extracts from Cos7-transfected cells. C) The experiment was performed as in B, but proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-p53 mAb or normal mouse serum. D) FBXW7 interacts with p53 in a yeast 2-hybrid assay. L40 reporter strain was cotransformed with the indicated constructs. The interaction between the 2-hybrid proteins is indicated by growth in the absence of histidine, yeast drop-out medium lacking Trp, Leu, and His (DO-wlh; dark red patch) and by the induction of LacZ expression (blue patches). RasV12/Raf interaction was used as a positive control. E) In vitro ubiquitylation assay of [35S]-labeled in vitro–transcribed and –translated p53 was conducted in the presence or absence of the following products: cold in vitro–transcribed and –translated FBXW7 or β-TrCP, E1 (His6-E1), E2 (His6-UbcH3 and UbcH5a), and ubiquitin (Ub). Samples were incubated at 30°C for 1 h. The bracket on the right side marks a ladder of bands corresponding to polyubiquitylated p53. F) The experiment was performed as in E, except that the unlabeled F-box protein was substituted by a recombinant SCF(FBXW7) complex expressed in Sf21 insect cells. G) Cos7 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and treated with MG132 for 4 h before harvesting. Extracts were prepared as indicated in the Materials and Methods and polyubiquitylated p53 visualized after Western blots of the Flag immunoprecipitations. AD, fusion with the activation domain of Gal4; BD, fusion with the DNA-binding domain of LexA; IP, immunoprecipitation.

FBXW7 contributes to the regulation of p53 turnover in unstressed mammalian cells

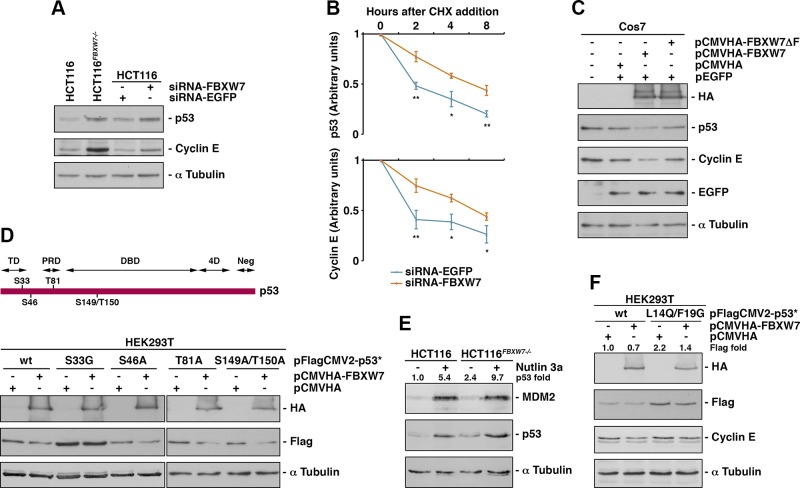

In order to test whether SCF(FBXW7) regulates p53 stability, we first assessed p53 levels in the absence of FBXW7 protein, either by using an FBXW7−/− cell line (HCT116FBXW7−/−) (23) or through RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated silencing experiments in HCT116 wild-type (WT) cells. In both cases, we observed an increase of p53 protein level that was similar to that obtained with cyclin E, a known FBXW7 substrate used as a control (32), in the FBXW7-siRNA–transfected cells (Fig. 2A). Consistent with this, the half-life of endogenous p53 in FBXW7-silenced cells was longer than in cells transfected with control siRNA targeting EGFP (Fig. 2B). Conversely, overexpression of FBXW7 in Cos7 cells induced a decrease in p53 protein. Figure 2C shows that FBXW7 overexpression caused a reduction of p53 levels that did not occur with overexpression of FBXW7-ΔF, a dominant-negative form of FBXW7 lacking the F-box domain that couples F-box protein to the SCF complex (33). Next, we analyzed the p53 protein sequence to identify potential FBXW7 binding sites. We found 4 possible CPDs, as defined by a serine or threonine followed by a proline, at positions 33, 46, 81, and 149 and 150 (Fig. 2D, upper panel). To ascertain whether any of these motifs is a functional CPD, we mutated the indicated residues to alanine or glycine and examined the degradation of these mutants by FBXW7 overexpression. Figure 2D (bottom panel) shows that only the mutation at Ser33 abrogated FBXW7-dependent p53 degradation. Therefore, FBXW7 is involved in p53 degradation in unstressed cells via an amino-terminal CPD including Ser33.

Figure 2.

SCF(FBXW7) induces p53 degradation in normal growing cells. A) Expression of p53 and cyclin E was studied in HCT116 and HCT116FBXW7−/− cells and in HCT116 cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs. An immunoblot for α-tubulin is shown as a loading control. B) U2OS cells were transfected with EGFP- or FBXW7-siRNA and, after 48 h, cycloheximide (CHX) was added to the medium, and cells were collected at the indicated times. Extracts were analyzed by Western blotting. p53 and cyclin E protein levels were quantified using ImageJ and normalized to α-tubulin levels. C) Cos7 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and, 18 h later, extracts were subjected to Western blot. D) Serines and threonines of the putative CPDs of p53 protein are indicated in the upper panel. In the lower panel, the overexpression of FBXW7 on WT or mutant p53 is shown. HEK293T cell were transfected with pFlagCMV2-p53 (WT or mutant) and 18 h later retransfected with pCMVHA-FBXW7 or empty vector. Extracts were analyzed by Western blot. E) HCT116 and HCT116FBXW7−/− cells were treated or not treated with Nutlin 3a for 24 h and extracts analyzed by immunoblot analysis. The quantitative fold change in p53 was determined relative to the loading control. F) Similarly to D, HEK293T were transfected with pFlagCMV2-p53 or pFlagCMV2-p53 L14Q/F19G and 18 h later retransfected with pCMVHA-FBXW7 or empty vector. Extracts were analyzed by Western blotting. The quantitative fold change in Flag-p53 or Flag-p53 L14Q/F19G was determined relative to the loading control. 4D, oligomerization domain; DBD, DNA-binding domain; Neg, negative regulation domain; PRD, proline-rich region; TD, transactivation domain. Error bars represent the sd (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Student’s t test).

MDM2 is probably the most significant E3 responsible for p53 degradation under conditions in which p53 is otherwise stabilized (34). To rule out that FBXW7 acts through MDM2 to regulate p53 levels, we followed 2 independent approaches. On the one hand, we evaluated the effect of Nutlin 3a, a small-molecule inhibitor of MDM2, on the level of p53 in WT and FBXW7−/− cells. We observed that, although the p53 levels increased significantly after Nutlin 3a treatment, there was still more p53 protein in FBXW7−/− than in the WT cells (Fig. 2E). On the other hand, we constructed a p53 mutant unable to bind to MDM2 (35) and tested whether its levels could be reduced by the overexpression of FBXW7. Figure 2F shows that the p53 mutant can still be degraded by SCF(FBXW7). These data, together with those obtained in yeast showing a direct interaction between FBXW7 and p53, indicate that FBXW7 has a role in the degradation of p53 independent of MDM2.

SCF(FBXW7) plays a critical role in the recovery of cell proliferation after DNA damage

A number of E3s have a role in p53 degradation after DNA damage (36–38). To determine whether FBXW7 is also involved in this process, we compared the increase of p53 protein levels after UV irradiation in both HCT116 and HCT116FBXW7−/− cell lines. We found that the presence of FBXW7 did not reduce p53 levels, at least within 24 h after DNA damage (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Next, we studied p53 stability and cell proliferation in the long term after UV irradiation in WT and FBXW7-deficient cells. We detected an increase of cell proliferation 3 d after UV irradiation in HCT116 cells (Fig. 3A) matching with a decrease of p53 protein (Fig. 3B, C). However, cells lacking FBXW7 began to proliferate 7 d after irradiation, consistent with persistence of high levels of p53 protein. Similar experiments were performed using DLD1 and DLD1FBXW7−/− cell lines, a cell model that is negative for functional p53 protein, unlike the HCT116 model (39). Using the DLD1 cell model, we did not observe proliferation differences after UV in the presence or absence of FBXW7. However, p53 was degraded in an FBXW7-dependent manner in this cell line (Supplemental Fig. S2). Together, these results indicate that FBXW7 is required for the recovery of cell proliferation after DNA damage and suggest specifically that the degradation of a functional p53 by SCF(FBXW7) is required for this process.

Figure 3.

FBXW7 is involved in the recovery of cell proliferation after DNA damage. A) Cell proliferation assay of HCT116 and HCT116FBXW7−/− cells after UV radiation. The amount of protein in extracts was taken as a measure of cell proliferation. B) Extracts were also used to analyze p53 expression by Western blotting. C) Quantification of protein levels in B using ImageJ and normalized to α-tubulin level. D, days after UV irradiation. U, nonirradiated cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. Error bars represent the sd (n = 4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t test).

Therefore, we can conclude that FBXW7 controls long-term p53 levels after DNA damage promoting cell proliferation.

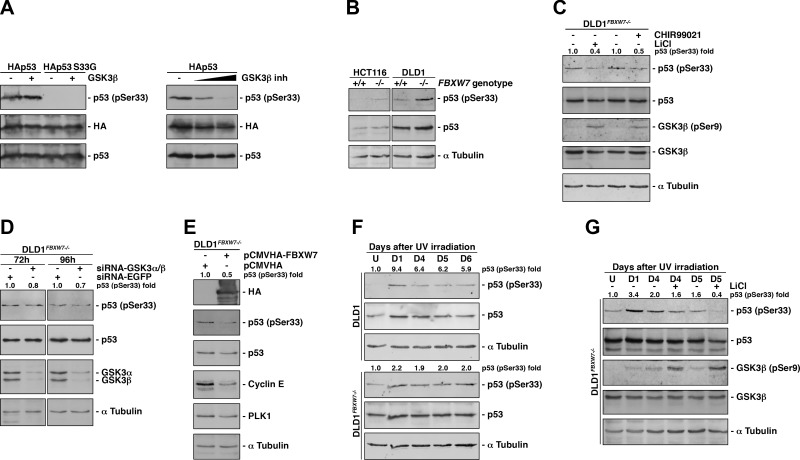

Phosphorylation of p53 by GSK3 triggers its degradation by SCF(FBXW7)

GSK3-β is a major kinase involved in the phosphorylation of SCF(FBXW7) substrates (12). In addition, it has been previously reported by Turenne et al. (40) that GSK3-β phosphorylates Ser33 of p53. Therefore, we sought to determine whether GSK3 was responsible for the degradation of p53 by SCF(FBXW7). We first verified that GSK3-β phosphorylates p53 Ser33 in vitro. Using a coupled in vitro transcription and translation system and a specific anti–phosphorylated p53 (Ser33) antibody, we observed that GSK3-β phosphorylated p53 at Ser33 and that this phosphorylation was prevented by a GSK3-β inhibitor (Fig. 4A). Then, we compared phosphorylated Ser33 levels in WT and FBXW7-deficient cells. We found that the absence of FBXW7 allowed detection of Ser33 phosphorylation, especially in DLD1 cells (Fig. 4B). To ascertain whether this p53 phosphorylation was mediated by GSK3, we employed GSK3 inhibitors and silencing experiments (Fig. 4C, D), confirming that GSK3 is largely responsible for the phosphorylation of p53 Ser33 under basal conditions. Lastly, we overexpressed HA-FBXW7 in DLD1FBXW7−/− cells, which led to a decrease in phosphorylated Ser33 levels (Fig. 4E). Together, these data show that GSK3 triggers p53 degradation by SCF(FBXW7) in normally growing cells.

Figure 4.

GSK3 phosphorylates p53 on Ser33 and promotes its ubiquitylation by SCF(FBXW7) and degradation. A) In vitro kinase assay of cold in vitro–transcribed and –translated HAp53 and a p53 mutant on Ser33 (HAp53 S33G) incubated with recombinant GSK3-β. Proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti–phosphorylated-p53 (Ser33) antibody (left panel). In the right panel, basal in vitro–transcribed and –translated HAp53 phosphorylation was inhibited with increasing amount of a specific GSK3-β inhibitor. B) Determination of phosphorylated p53 (Ser33) status of WT and FBXW7−/− HCT116 and DLD1 cells. C) Analysis of phosphorylated p53 (Ser33) status of DLD1FBXW7−/− cells treated or not treated with 2 GSK3 inhibitors (CHIR99021 and LiCl). D) DLD1FBXW7−/− cells were transfected with GSK3-α and -β or EGFP-siRNA, and 72 or 96 h later, cell extracts were blotted with the indicated antibodies. E) DLD1FBXW7−/− cells were transfected with pCMVHA-FBXW7 or pCMVHA, and extracts analyzed by Western blotting. F) Expression of phosphorylated p53 (Ser33) in DLD1 and DLD1FBXW7−/− cells after UV radiation. G) Effect of LiCl on p53 S33 phosphorylation of DLD1FBXW7−/− cells after UV irradiation. Inhibitor was added 24 h before harvesting. The quantitative fold change in phosphorylated p53 (Ser33) was determined relative to total p53 protein. Experiments were repeated 3 times with similar results. D, days after UV irradiation; U, untreated cells.

Next, we wondered whether GSK3 was also involved in the degradation of p53 during the recovery of cell proliferation. We therefore compared the phosphorylation level of Ser33 after UV irradiation in DLD1 and DLD1FBXW7−/− cells. We observed that the phosphorylated Ser33 level remained constant after UV irradiation in cells lacking FBXW7, whereas it decreased in WT cells (Fig. 4F). These results suggest that p53 must be phosphorylated by GSK3 after UV to be degraded by SCF(FBXW7). Furthermore, the inhibition of GSK3 enzymatic activity after irradiation reduced Ser33 phosphorylation (Fig. 4G), implicating this kinase in the recovery of cell proliferation. Therefore, our results strongly support a role for GSK3-dependent phosphorylation of serine 33 in p53 degradation by SCF(FBXW7) both under basal conditions and in the recovery of cell proliferation after DNA damage.

Involvement of FBXW7 on cell proliferation recovery after UV is mediated by p53 degradation

To validate the direct involvement of p53 degradation by SCF(FBXW7) in the recovery of cell proliferation after UV damage, we transfected HCT116p53−/− cells with p53 or p53 S33G, the mutated form of p53 resistant to degradation by SCF(FBXW7). We compared the ability of these lines to proliferate after UV irradiation by using a clonal survival assay for determining cell viability. As a control, we used HCT116FBXW7−/− cells transfected with empty vector. Figure 5A shows that, whereas HCT116p53−/−(pFlagCMV2p53) formed colonies a few days after being irradiated, the number of colonies formed by HCT116p53−/−(pFlagCMV2p53 S33G) or HCT116FBXW7−/−(pFlagCMV2) was significantly reduced. Thus, cells lacking FBXW7 behave similarly to those expressing p53 that is resistant to degradation by SCF(FBXW7) (Fig. 5B). These results show that the role carried out by FBXW7 in the recovery of cell proliferation after DNA damage is mediated by the degradation of p53.

Figure 5.

The role of FBXW7 in the recovery of cell proliferation after DNA damage is mediated by the degradation of p53. A) HCT116FBXW7−/− and HCT116p53−/− cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and 24 h later irradiated (60 J/m2) or not. Crystal violet assay was performed from d 3 to 7 post-UV. Images show data from d 5 after irradiation. B) Quantification of crystal violet assay described in A. Error bars represent the sd (n = 3). The significance was obtained by comparing values of HCT116p53−/− pFlagCMV-p53 vs. HCT116p53−/− pFlagCMV-p53 S33G. Expression level of transfected plasmids is also shown. Scale bar, 400 μm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t test).

FBXW7 reduces UV-induced p53-dependent cell death

To further evaluate the pivotal role of FBXW7 in recovery of proliferation after DNA damage, we assessed the level of apoptosis induced by UV irradiation in cells lacking FBXW7 vs. WT HCT116 cells. We observed a lower level of cleaved PARP and activated caspase-3 at 48 h after UV irradiation in HCT116 cells compared with HCT116FBXW7−/− cells (Fig. 6A, left panels), suggesting that the presence of FBXW7 also confers a reduction of UV-induced apoptosis in the HCT116 cell line. Again, similar experiments performed using the DLD1 cell model, in which apoptosis is p53-independent (41), did not show apparent differences between the WT or FBXW7−/− cells (Fig. 6A, right panels). Therefore, we conclude that FBXW7 accelerates the recovery of cell proliferation by also reducing p53-mediated apoptosis after damage.

Figure 6.

Influence of FBXW7 on apoptosis induced by p53 after DNA damage and its role in the survival of patients with breast cancer. A) HCT116 and DLD1 WT and FBXW7−/− cells were irradiated and collected at the indicated times. Extracts were analyzed by Western blotting. The quantitative fold change in cleaved PARP was determined relative to the loading control. Experiments were repeated 3 times with similar results. B) Kaplan-Meier analysis of patients with WT p53 breast cancer with WT FBXW7 (n = 1453; orange line) compared with increased levels of FBXW7, FBXW7amp (n = 68; blue line). Tick marks represent censored patients. The P values were obtained from the log-rank test of Mantel and Cox. C) Similar to B, but comparing patients with breast cancer with tumors p53loss/FBXW7wt (n = 852; orange line) vs. p53loss/FBXW7amp (n = 73; blue line). U, untreated control cells.

Finally, in order to assess the clinical implications of our findings, we analyzed the survival of patients with cancer depending on their FBXW7 and p53 statuses. Because FBXW7 is a well-documented tumor suppressor that is mutated or deleted in many tumors (most of them also mutated in p53), we wanted to explore the effect of an increase of FBXW7 (FBXW7amp) on survival of patients with WT p53 tumors. Using data from the cBioPortal database (from TCGA and the Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium (METABRIC) (29, 30), we compared the survival of patients with p53wt and FBXW7amp breast cancer (n = 68) vs. patients with p53wt and FBXW7wt breast cancer (n = 1453). Interestingly, we found poorer survival in patients who had tumors with amplified FBXW7 vs. those who did not (P = 0.001) (Fig. 6B). Conversely, the increase of FBXW7 did not significantly alter the survival of patients suffering breast cancer carrying p53 mutations (p53loss/FBXW7amp, n = 73 vs. p53loss/FBXW7wt, n = 852) (Fig. 6C), suggesting that the role of FBXW7 in survival of patients with breast cancer occurs through p53. Despite the above results, the survival analysis of patients with bladder cancer or skin cutaneous melanoma who had tumors with FBXW7amp did not show significant differences in survival relative to those who did not (unpublished results). The low number of patients under analysis (19 and 29 patients, respectively) may account for the lack of a significant correlation. Nevertheless, taken together, our results lead us to suggest that, depending on a patient’s genetic profile, FBXW7 inhibition might be a reasonable therapeutic approach.

DISCUSSION

The TP53 tumor-suppressor gene is the most frequently mutated gene in human cancer. In fact, it has been reported that at least 50% of human malignancies contain TP53 mutations, which are especially predominant in carcinomas of ovary and endometrium and in basal subtype breast tumors (42). This high frequency of mutation is consistent with its role in cell-cycle regulation, senescence, and apoptosis. p53 activates transcription of many genes, including those that encode proteins involved in cell-cycle arrest, such as CDK interacting protein 1 (p21WAF1/CIP1), or proapoptotic proteins, such as p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA), NOXA, or FAS (43, 44). In unstressed cells, the p53 protein level is low because of proteasomal degradation mainly mediated by MDM2 (34), although other E3s may also be involved (45). However, in response to many stress signals, such as DNA damage, aberrant oncogenic signaling, nutrient deprivation, or hypoxia, p53 accumulates in the nucleus and transactivates numerous target genes. Depending on the stress intensity, cells can resume proliferation after repairing the damage or die by apoptosis or necroptosis if the damage is irreparable. To successfully recover from the arrest, p53 must be inactivated. Because p53 activation is largely mediated by phosphorylation, several phosphatases have been described that are likely to be involved in p53 inactivation: WIP1, which dephosphorylates p53 at serine 15, reversing the G2/M cell-cycle arrest caused by DNA damage (46); dual-specificity phosphatase 26 (DUSP26), which inhibits the p53 tumor-suppressor function dephosphorylating serines 20 and 37 (47); protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), which also dephosphorylates serine 15 of p53 and stabilizes the p53 regulator murine double minute X (MDMX) (48); and protein phosphatase 4 (PP4), among others, which reverses the p53-mediated G1 arrest induced by DNA damage (49). These phosphatases dephosphorylate p53, thereby affecting its stability and/or its regulators or effectors. In this study, we identify a new mechanism involved in the release from p53 checkpoint arrest after UV irradiation. We found that FBXW7 is needed to support recovery of proliferation once DNA damage has been repaired. GSK3 phosphorylates p53 at serine 33, triggering its ubiquitylation and degradation by SCF(FBXW7). This reduction in p53 levels allows the recovery of cell proliferation. Interestingly, FBXW7 has been described as a p53 transcriptional target gene (50, 51), suggesting that FBXW7 likely operates as part of a negative feedback regulatory loop with p53. Thus, the stress-induced accumulation and activation of p53 up-regulates FBXW7, which in turn leads to ubiquitylation and degradation of p53 once the stress has been removed.

Because our results show that FBXW7 enhances proliferation under certain conditions, we analyzed survival of patients with p53wt and FBXW7amp cancer using the cBioPortal database. In this context, we found that increased FBXW7 reduced the survival of patients with breast cancer. Therefore, it may be reasonable to propose the use of FBXW7 inhibitors for the treatment of this subset of tumors. One could envision a treatment based on DNA-damaging agents to induce p53 and inhibitors of FBXW7 to prevent its degradation. In that way, perhaps p53-mediated apoptosis would promote tumor regression. Another situation in which it may be convenient to inhibit FBXW7 is in the maintenance of quiescence in the leukemia-initiating cells of chronic myeloid leukemia. Ablation of FBXW7 increased sensitivity of leukemia-initiating cells to imatinib, an anticancer drug that targets dividing cells. Thus, combination of FBXW7 inhibitors and imatinib may provide a promising therapeutic approach to chronic myeloid leukemia (52). Therefore, it seems increasingly clear that the classic distinction between oncogenes and tumor suppressors is dependent on cellular context. Thus, a tumor suppressor can promote tumorigenesis when mutated or deleted but perhaps also reduce survival when overexpressed. In agreement with this idea, other F-box proteins, such as β-TrCP, can also act as an oncoprotein or a tumor-suppressor protein in a cellular context–dependent manner, in this case mainly because of the diversity of substrates (53).

In the present work, we leave open an additional question that would be interesting to address in future studies. We have elucidated that once cells repair the damage induced by UV irradiation, SCF(FBXW7) degrades p53. However, immediately after the damage occurs, the presence of FBXW7 allows a rapid accumulation of p53. A plausible explanation would be that FBXW7 contributes to the degradation of a negative p53 regulator in response to DNA damage, although currently we have no evidence supporting this hypothesis.

Taken together, our findings provide evidence for a new mechanism of regulation of the p53-mediated DNA damage response through FBXW7. Specifically, we show that after DNA damage, FBXW7 contributes to arrest the cell cycle, allowing a rapid increase of p53, and when damage has been repaired, FBXW7-mediated degradation of p53 allows recovery of cell proliferation. Given the crucial role of FBXW7 in cell proliferation but also in growth and differentiation and its pivotal role in tumorigenesis, it is essential to know the context-dependent function of this protein. Such an endeavor could pave the way for development of personalized therapies, including treatments based on FBXW7 inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Spanish grants from the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO; SAF2014-53799 and SAF2017-87358) and Junta de Andalucía (2017/BIO-211), and U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Cancer Institute Grant CA078343, and NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant GM115170 (to S.I.R.). A.B.-F. is the recipient of a Ph.D. fellowship from the Vicerrectorado de Investigación Plan Propio de Investigación (VI PPI) from Universidad de Sevilla. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- β-TrCP

β-transducin repeat-containing protein

- CPD

cell division control protein 4 (CDC4)-phosphodegron

- E1

ubiquitin-activating enzyme

- E2

ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme

- E3

ubiquitin ligase

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- FBXW7

F-box and tryptophan-aspartic acid (WD) repeat domain containing 7

- GSK3

glycogen synthase kinase 3

- HA

hemagglutinin

- MDM2

murine double minute 2

- NP40

Nonidet P-40

- PARP

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

- SCF

S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 (SKP1)–Cullin-1–F-box protein

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M. Galindo-Moreno and S. Giráldez performed the main experiments and analyzed data; M. C. Limón-Mortés and A. Belmonte-Fernández designed and contributed to perform proliferation experiments; S. I. Reed conceived and mentored some experiments; C. Sáez and M. Á. Japón performed cell-cycle and Kaplan-Meier analysis and contributed to the discussion of the results; and M. Tortolero and F. Romero designed the research and wrote the manuscript with input from all other authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ji C. H., Kwon Y. T. (2017) Crosstalk and interplay between the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy. Mol. Cells 40, 441–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser P., Huang L. (2005) Global approaches to understanding ubiquitination. Genome Biol. 6, 233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakayama K. I., Nakayama K. (2006) Ubiquitin ligases: cell-cycle control and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 369–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welcker M., Orian A., Grim J. E., Eisenman R. N., Clurman B. E. (2004) A nucleolar isoform of the Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase regulates c-Myc and cell size. Curr. Biol. 14, 1852–1857; erratum: 15, 2285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grim J. E., Gustafson M. P., Hirata R. K., Hagar A. C., Swanger J., Welcker M., Hwang H. C., Ericsson J., Russell D. W., Clurman B. E. (2008) Isoform- and cell cycle-dependent substrate degradation by the Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase. J. Cell Biol. 181, 913–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heo J., Eki R., Abbas T. (2016) Deregulation of F-box proteins and its consequence on cancer development, progression and metastasis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 36, 33–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis R. J., Welcker M., Clurman B. E. (2014) Tumor suppression by the Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase: mechanisms and opportunities. Cancer Cell 26, 455–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akhoondi S., Sun D., von der Lehr N., Apostolidou S., Klotz K., Maljukova A., Cepeda D., Fiegl H., Dafou D., Marth C., Mueller-Holzner E., Corcoran M., Dagnell M., Nejad S. Z., Nayer B. N., Zali M. R., Hansson J., Egyhazi S., Petersson F., Sangfelt P., Nordgren H., Grander D., Reed S. I., Widschwendter M., Sangfelt O., Spruck C. (2007) FBXW7/hCDC4 is a general tumor suppressor in human cancer. Cancer Res. 67, 9006–9012; erratum: 68, 1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nash P., Tang X., Orlicky S., Chen Q., Gertler F. B., Mendenhall M. D., Sicheri F., Pawson T., Tyers M. (2001) Multisite phosphorylation of a CDK inhibitor sets a threshold for the onset of DNA replication. Nature 414, 514–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orlicky S., Tang X., Willems A., Tyers M., Sicheri F. (2003) Structural basis for phosphodependent substrate selection and orientation by the SCFCdc4 ubiquitin ligase. Cell 112, 243–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang X., Orlicky S., Liu Q., Willems A., Sicheri F., Tyers M. (2005) Genome-wide surveys for phosphorylation-dependent substrates of SCF ubiquitin ligases. Methods Enzymol. 399, 433–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welcker M., Clurman B. E. (2008) FBW7 ubiquitin ligase: a tumour suppressor at the crossroads of cell division, growth and differentiation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 83–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welcker M., Larimore E. A., Swanger J., Bengoechea-Alonso M. T., Grim J. E., Ericsson J., Zheng N., Clurman B. E. (2013) Fbw7 dimerization determines the specificity and robustness of substrate degradation. Genes Dev. 27, 2531–2536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giráldez S., Herrero-Ruiz J., Mora-Santos M., Japón M. A., Tortolero M., Romero F. (2014) SCF(FBXW7α) modulates the intra-S-phase DNA-damage checkpoint by regulating Polo like kinase-1 stability. Oncotarget 5, 4370–4383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leman A. R., Noguchi E. (2013) The replication fork: understanding the eukaryotic replication machinery and the challenges to genome duplication. Genes (Basel) 4, 1–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J., Wu X., Lin J., Levine A. J. (1996) mdm-2 inhibits the G1 arrest and apoptosis functions of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 2445–2452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukuda T., Naiki T., Saito M., Irie K. (2009) hnRNP K interacts with RNA binding motif protein 42 and functions in the maintenance of cellular ATP level during stress conditions. Genes cells 14, 113–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klotz K., Cepeda D., Tan Y., Sun D., Sangfelt O., Spruck C. (2009) SCF(Fbxw7/hCdc4) targets cyclin E2 for ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. Exp. Cell Res. 315, 1832–1839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margottin F., Bour S. P., Durand H., Selig L., Benichou S., Richard V., Thomas D., Strebel K., Benarous R. (1998) A novel human WD protein, h-beta TrCp, that interacts with HIV-1 Vpu connects CD4 to the ER degradation pathway through an F-box motif. Mol. Cell 1, 565–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romero F., Dargemont C., Pozo F., Reeves W. H., Camonis J., Gisselbrecht S., Fischer S. (1996) p95vav associates with the nuclear protein Ku-70. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 37–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breeden L., Nasmyth K. (1985) Regulation of the yeast HO gene. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 50, 643–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romero F., Gil-Bernabé A. M., Sáez C., Japón M. A., Pintor-Toro J. A., Tortolero M. (2004) Securin is a target of the UV response pathway in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 2720–2733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajagopalan H., Jallepalli P. V., Rago C., Velculescu V. E., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B., Lengauer C. (2004) Inactivation of hCDC4 can cause chromosomal instability. Nature 428, 77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bunz F., Hwang P. M., Torrance C., Waldman T., Zhang Y., Dillehay L., Williams J., Lengauer C., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1999) Disruption of p53 in human cancer cells alters the responses to therapeutic agents. J. Clin. Invest. 104, 263–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J. Y., Yu S. J., Park Y. G., Kim J., Sohn J. (2007) Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta phosphorylates p21WAF1/CIP1 for proteasomal degradation after UV irradiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 3187–3198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phiel C. J., Wilson C. A., Lee V. M., Klein P. S. (2003) GSK-3alpha regulates production of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-beta peptides. Nature 423, 435–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Drogen F., Sangfelt O., Malyukova A., Matskova L., Yeh E., Means A. R., Reed S. I. (2006) Ubiquitylation of cyclin E requires the sequential function of SCF complexes containing distinct hCdc4 isoforms. Mol. Cell 23, 37–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romero F., Multon M. C., Ramos-Morales F., Domínguez A., Bernal J. A., Pintor-Toro J. A., Tortolero M. (2001) Human securin, hPTTG, is associated with Ku heterodimer, the regulatory subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 1300–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cerami E., Gao J., Dogrusoz U., Gross B. E., Sumer S. O., Aksoy B. A., Jacobsen A., Byrne C. J., Heuer M. L., Larsson E., Antipin Y., Reva B., Goldberg A. P., Sander C., Schultz N. (2012) The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2, 401–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao J., Aksoy B. A., Dogrusoz U., Dresdner G., Gross B., Sumer S. O., Sun Y., Jacobsen A., Sinha R., Larsson E., Cerami E., Sander C., Schultz N. (2013) Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal. 6, pl1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fields S., Song O. (1989) A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature 340, 245–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strohmaier H., Spruck C. H., Kaiser P., Won K. A., Sangfelt O., Reed S. I. (2001) Human F-box protein hCdc4 targets cyclin E for proteolysis and is mutated in a breast cancer cell line. Nature 413, 316–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welcker M., Orian A., Jin J., Grim J. E., Harper J. W., Eisenman R. N., Clurman B. E. (2004) The Fbw7 tumor suppressor regulates glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation-dependent c-Myc protein degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 9085–9090; erratum: 103, 504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haupt Y., Maya R., Kazaz A., Oren M. (1997) Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature 387, 296–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin J., Chen J., Elenbaas B., Levine A. J. (1994) Several hydrophobic amino acids in the p53 amino-terminal domain are required for transcriptional activation, binding to mdm-2 and the adenovirus 5 E1B 55-kD protein. Genes Dev. 8, 1235–1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hakem A., Bohgaki M., Lemmers B., Tai E., Salmena L., Matysiak-Zablocki E., Jung Y. S., Karaskova J., Kaustov L., Duan S., Madore J., Boutros P., Sheng Y., Chesi M., Bergsagel P. L., Perez-Ordonez B., Mes-Masson A. M., Penn L., Squire J., Chen X., Jurisica I., Arrowsmith C., Sanchez O., Benchimol S., Hakem R. (2011) Role of Pirh2 in mediating the regulation of p53 and c-Myc. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia Y., Padre R. C., De Mendoza T. H., Bottero V., Tergaonkar V. B., Verma I. M. (2009) Phosphorylation of p53 by IkappaB kinase 2 promotes its degradation by beta-TrCP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 2629–2634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang W., Rozan L. M., McDonald E. R., III, Navaraj A., Liu J. J., Matthew E. M., Wang W., Dicker D. T., El-Deiry W. S. (2007) CARPs are ubiquitin ligases that promote MDM2-independent p53 and phospho-p53ser20 degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3273–3281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Connor P. M., Jackman J., Bae I., Myers T. G., Fan S., Mutoh M., Scudiero D. A., Monks A., Sausville E. A., Weinstein J. N., Friend S., Fornace A. J., Jr., Kohn K. W. (1997) Characterization of the p53 tumor suppressor pathway in cell lines of the National Cancer Institute anticancer drug screen and correlations with the growth-inhibitory potency of 123 anticancer agents. Cancer Res. 57, 4285–4300 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turenne G. A., Price B. D. (2001) Glycogen synthase kinase3 beta phosphorylates serine 33 of p53 and activates p53's transcriptional activity. BMC Cell Biol. 2, 12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martinico S. C., Jezzard S., Sturt N. J., Michils G., Tejpar S., Phillips R. K., Vassaux G. (2006) Assessment of endostatin gene therapy for familial adenomatous polyposis-related desmoid tumors. Cancer Res. 66, 8233–8240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kandoth C., McLellan M. D., Vandin F., Ye K., Niu B., Lu C., Xie M., Zhang Q., McMichael J. F., Wyczalkowski M. A., Leiserson M. D. M., Miller C. A., Welch J. S., Walter M. J., Wendl M. C., Ley T. J., Wilson R. K., Raphael B. J., Ding L. (2013) Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature 502, 333–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El-Deiry W. S., Tokino T., Velculescu V. E., Levy D. B., Parsons R., Trent J. M., Lin D., Mercer W. E., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1993) WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 75, 817–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakano K., Vousden K. H. (2001) PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol. Cell 7, 683–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sane S., Rezvani K. (2017) Essential roles of E3 ubiquitin ligases in p53 regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, E442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu X., Nannenga B., Donehower L. A. (2005) PPM1D dephosphorylates Chk1 and p53 and abrogates cell cycle checkpoints. Genes Dev. 19, 1162–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shang X., Vasudevan S. A., Yu Y., Ge N., Ludwig A. D., Wesson C. L., Wang K., Burlingame S. M., Zhao Y. J., Rao P. H., Lu X., Russell H. V., Okcu M. F., Hicks M. J., Shohet J. M., Donehower L. A., Nuchtern J. G., Yang J. (2010) Dual-specificity phosphatase 26 is a novel p53 phosphatase and inhibits p53 tumor suppressor functions in human neuroblastoma. Oncogene 29, 4938–4946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu Z., Wan G., Guo H., Zhang X., Lu X. (2013) Protein phosphatase 1 inhibits p53 signaling by dephosphorylating and stabilizing Mdmx. Cell. Signal. 25, 796–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shaltiel I. A., Aprelia M., Saurin A. T., Chowdhury D., Kops G. J., Voest E. E., Medema R. H. (2014) Distinct phosphatases antagonize the p53 response in different phases of the cell cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 7313–7318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kitade S., Onoyama I., Kobayashi H., Yagi H., Yoshida S., Kato M., Tsunematsu R., Asanoma K., Sonoda K., Wake N., Hata K., Nakayama K. I., Kato K. (2016) FBXW7 is involved in the acquisition of the malignant phenotype in epithelial ovarian tumors. Cancer Sci. 107, 1399–1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mao J. H., Perez-Losada J., Wu D., Delrosario R., Tsunematsu R., Nakayama K. I., Brown K., Bryson S., Balmain A. (2004) Fbxw7/Cdc4 is a p53-dependent, haploinsufficient tumour suppressor gene. Nature 432, 775–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takeishi S., Matsumoto A., Onoyama I., Naka K., Hirao A., Nakayama K. I. (2013) Ablation of Fbxw7 eliminates leukemia-initiating cells by preventing quiescence. Cancer Cell 23, 347–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frescas D., Pagano M. (2008) Deregulated proteolysis by the F-box proteins SKP2 and beta-TrCP: tipping the scales of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 438–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.