Abstract

Background and Aims

The World Health Organization recommends increasing alcohol taxes as a ‘best‐buy’ approach to reducing alcohol consumption and improving population health. Alcohol may be taxed based on sales value, product volume or alcohol content; however, duty structures and rates vary, both among countries and between beverage types. From a public health perspective, the best duty structure links taxation level to alcohol content, keeps pace with inflation and avoids substantial disparities between different beverage types. This data note compares current alcohol duty structures and levels throughout the 28 European Union (EU) Member States and how these vary by alcohol content, and also considers implications for public health.

Design and Setting

Descriptive analysis using administrative data, European Union, July 2018.

Measurements

Beverage‐specific alcohol duty rates per UK alcohol unit (8 g ethanol) in pounds sterling at a range of different alcoholic strengths.

Findings

Only 50% of Member States levy any duty on wine and several levy duty on spirits and beer at or close to the EU minimum level. There is at least a 10‐fold difference in the effective duty rate per unit between the highest‐ and lowest‐duty countries for each beverage type. Duty rates for beer and spirits stay constant with strength in the majority of countries, while rates for wine and cider generally fall as strength increases. Duty rates are generally higher for spirits than other beverage types and are generally lowest in eastern Europe and highest in Finland, Sweden, Ireland and the United Kingdom.

Conclusions

Different European Union countries enact very different alcohol taxation policies, despite a partially restrictive legal framework. There is only limited evidence that alcohol duties are designed to minimize public health harms by ensuring that drinks containing more alcohol are taxed at higher rates. Instead, tax rates appear to reflect national alcohol production and consumption patterns.

Keywords: Alcohol duty, alcohol policy, pricing policies, public health, taxation, tax structures

Introduction

Controlling the price of alcohol, usually through taxation, has long been established as an effective approach to address the burden that alcohol places upon society, and it is listed by the World Health Organization as a ‘best buy’ policy 1. A public health perspective favours tax systems under which tax increases as alcohol content increases 2. It is important to recognize that alcohol taxation acts to raise revenue in addition to any public health purpose; however, evidence shows that different systems of alcohol taxation are not equally effective at reducing alcohol‐related harm and inequalities in that harm 3. Additional public health gains may be available by ensuring that taxation reflects changes in the cost of living and by taxing the strongest beverages (e.g. spirits) at higher rates, as they allow larger quantities of alcohol to be consumed within shorter time‐scales and therefore are associated with additional health risks. However, there is wide variation internationally in both the scale and the structure of alcohol taxation 2, with alcohol usually being taxed on one or more of three different bases:

The volume of product (so‐called unitary taxation);

The volume of alcohol contained in the product (specific or volumetric taxation) and

The value of the product (ad‐valorem taxation).

The European Union (EU) has a common legal framework for alcohol duty which incorporates elements of all of these approaches 4. Spirits are required to be taxed on a specific basis, as is beer, except in particular circumstances outlined below. Wine, sparkling wine, ‘other fermented beverages’ (which includes cider) and ‘intermediate products’ (such as fortified wines, including sherry and port) must be taxed on a unitary basis, not on their alcohol content. EU Member States are then free to levy additional ad‐valorem taxes on top of these duty rates although, in practice, ad‐valorem taxes affecting alcohol are usually general sales taxes, rather than alcohol‐specific taxes. The levying of duty itself on an ad‐valorem basis is not permitted.

Minimum duty rates are specified for beer, at £1.65 per hectolitre per degree of alcohol (equivalent to £0.04 on 500 ml of 5% alcohol by volume (ABV) beer), and for spirits, at £486.31 per hectolitre of ethanol (equivalent to £1.95 on a 1‐litre bottle of 40% ABV vodka) 5. There is no minimum duty rate for wine.

A small number of exceptions apply to these regulations. First, beer with an alcoholic strength of 2.8% or lower and wine with a strength of 8.5% or lower may be subject to a reduced rate of duty. Secondly, a small number of products produced in specific locations (such as Madeira) are explicitly exempted from the prescribed minimum duty rates. Finally, beer duty can be levied on the basis of either the alcohol content itself or degrees Plato—a measure based on sugar concentration prior to fermentation. If duty is levied on the basis of degrees Plato then additional duty bands are permitted, provided that these are no wider than 4 degrees Plato (approximately 1.6 percentage points ABV), within which duty can be levied on either a specific or unitary basis.

Within these parameters, the 28 current EU Member States are at liberty to determine their own levels of alcohol taxation. In this data note, we review the current levels and structures of alcohol duty throughout the EU, how the amount of tax paid varies with alcoholic strength and considers the extent to which this variation aligns with a public health perspective.

Methods

Using publicly available data reported by every EU Member State, including the United Kingdom 6, we converted alcohol duty rates effective on 1 July 2018 into the equivalent duty payable in pounds sterling per unit of alcohol (defined as 8 g, equivalent to 10 ml, of ethanol) at a range of different alcoholic strengths (defined in terms of percentage ABV). Currency conversion was undertaken using contemporaneous exchange rates included in the EU document. We excluded general ad‐valorem taxes affecting alcoholic and non‐alcoholic products, i.e. value‐added tax (VAT), which varies throughout the EU, from 17% in Luxembourg to 27% in Hungary. Duty rates on beer defined in terms of degrees Plato were converted to ABV equivalents (1 degree Plato = 0.4% ABV) in line with the EU's own assumptions 6. In order to assess whether differences in tax rates reflect variation in the cost of living between Member States, we performed a secondary analysis which accounted for differences in purchasing power using purchasing power parity (PPP) conversion rates from the World Bank 7.

Results

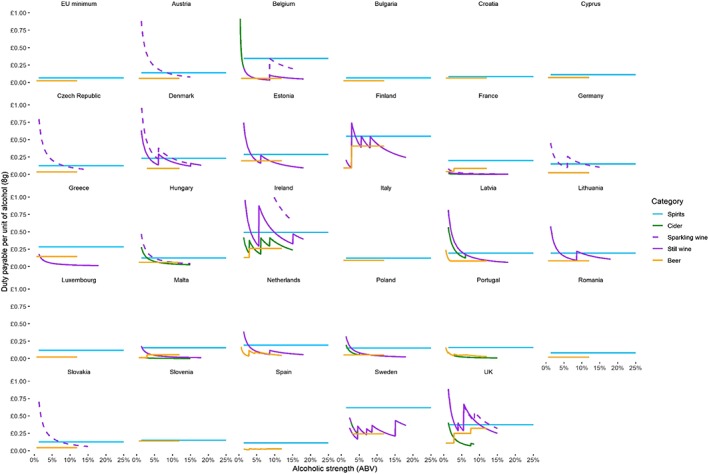

Figure 1 illustrates the comparative duty rates for beer, wine, sparkling wine, cider and spirits throughout the 28 EU Member States. Duty rates set to zero are not shown. Supporting information, Figure S1 contains more detailed graphs showing all beverage types for every Member State.

Figure 1.

Alcohol duty rates for common products across all 28 European Union Member States. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Three basic patterns are evident in the data. First, owing to the restrictions placed by the EU on duty structures, duty rates on spirits and beer do not rise with strength (beyond a reduced rate for low‐strength beer) and duty rates for wine and cider actually fall with strength, although this is mitigated to some extent by banded rates at lower strengths. Secondly, some countries, particularly those in eastern and southern Europe, set levels of taxation at or close to the EU minimum levels. This is particularly common for wine, with only half of the 28 EU nations, predominantly those in northern Europe, levying any form of duty on wine. In contrast, only five countries set taxes at the minimum level for beer and spirits. Thirdly, in the vast majority of countries, the effective duty per unit on spirits is higher than on other beverage types. This differential is particularly striking in Belgium and Sweden, where the tax per unit levied on spirits is 5.7 and 2.6 times higher, respectively, than the tax per unit on 12.5% wine.

Four Member States, Finland, Sweden, Ireland and the United Kingdom, stand out as having generally higher rates of taxation among all beverage types when compared to other countries. In three of these—Finland, Sweden and Ireland—banded rates of duty for wine and cider restrict the tax rate per unit within a narrow range across the majority of the ABV spectrum, rather than allowing it to fall as strength increases. This is in notable contrast to the other higher tax country, the United Kingdom, where duty on low‐strength ciders at 3.5% ABV is £0.15 per unit, while on ciders sold at 7.5% ABV it falls to £0.07 per unit. This approach means that the United Kingdom also has a strikingly large variation in its equivalent duty rates per unit for cider, beer, wine and spirits which, at 7.5% ABV, are £0.07, 0.25, 0.50 and 0.37, respectively.

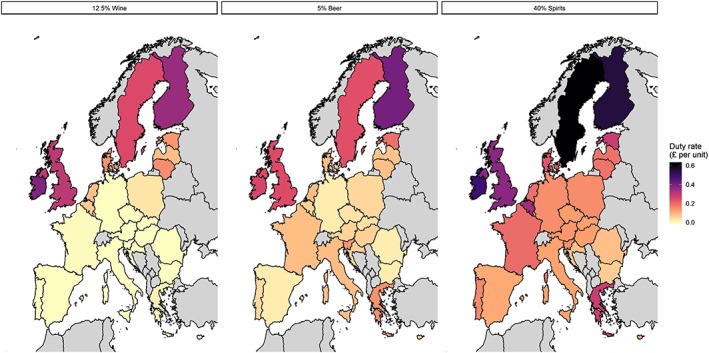

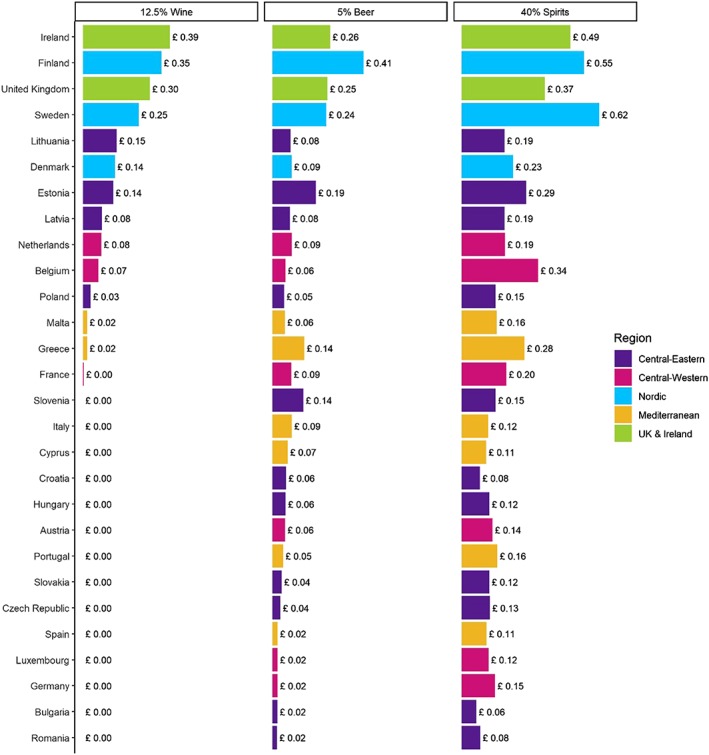

Figures 2 and 3 present the comparative duty levied throughout the EU on a unit of alcohol in three common products: 5.0% ABV beer, 12.5% ABV wine and 40.0% ABV spirits. Finland has the highest rate of duty on 5.0% beer, at £0.41/unit, while Spain, Luxembourg, Germany, Romania and Bulgaria all use the EU minimum rate for beer of £0.02/unit. Of the 14 EU countries who levy duty on wine, the effective rates for 12.5% still wine vary by a factor of 100, from £0.003/unit in France to £0.39/unit in Ireland. For spirits, only Bulgaria uses the EU minimum duty rate of £0.06/unit, while Sweden has the highest rate at £0.62/unit.

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of alcohol duty rates per unit for selected products. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 3.

Alcohol duty rates per unit for selected products by region. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The impact of adjusting duty rates for purchasing power is shown in Supporting information, Figs S2–S4. The main difference is an increase in the relative rates of alcohol taxation in eastern Europe, particularly in Greece, Poland and the Baltic states. This adjustment arguably provides a clearer sense of the effective rates of alcohol taxation relative to the incomes and living costs of citizens residing within each country. However, freedom of movement between EU countries means that caution must be applied when interpreting the figures. For example, the PPP‐adjusted rates of duty in neighbouring countries, Estonia and Finland, appear fairly similar (e.g. £0.42/unit for spirits compared to £0.49/unit), but the absolute rate of duty in Estonia is much lower (e.g. £0.29/unit for spirits compared to £0.55/unit). This helps to explain why approximately 20% of Finnish spirits consumption originates from tourist imports, predominantly from Estonia 8, 9.

Discussion

This analysis illustrates that, even within a prescribed system of duty structures such as that mandated by the EU, there can be substantial between‐country variation in the levels and structures of alcohol duty. From the perspective of public health, alcohol tax systems should broadly seek to encourage consumption of lower, rather than high‐strength drinks, as this is likely to lead to reductions in overall levels of alcohol consumption. In this context, the EU‐mandated approach of levying duty on wine and cider on the basis of product volume, rather than strength, may act against the interests of public health, potentially encouraging production and consumption of higher strength products. This is exacerbated by the fact that duty bands are not permitted for wine at the strengths at which most wine is consumed (i.e. above 8.5%).

In contrast, the specific taxation approach used for both beer and spirits means that the tax payable on these products is proportional to the alcohol content of the product. A more progressive approach, however, would levy higher taxes on stronger products. The only current example of this is in the United Kingdom, which is unique in having a higher specific duty rate for high‐strength beers and a lower rate for those at low strength. This reflects a desire to encourage consumers to choose lower‐alcohol beers or to encourage producers to manufacture more low‐strength products and reduce the strength of existing products 10. Three other countries, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain, use multiple duty bands based on degrees Plato, which could potentially be used for the same purpose; however, in practice the rates of duty set mean that there is little variation in effective duty rate per unit of alcohol throughout the ABV spectrum.

As well as comparing duty rates across the ABV spectrum within drink types, it is also informative to consider the relative levels of duty on different products. Typically, spirits have a higher alcohol content than wine which is, in turn, stronger than beer. In most countries, spirits are taxed at a higher rate per unit than wine or beer, although the extent of this gap varies widely, with Belgium in particular standing out as having markedly higher taxation on spirits than other forms of alcohol. This is broadly in line with public health interests, which may view high‐strength spirits as a particular concern as they allow the consumption of a greater volume of alcohol in a shorter space of time. Going against this approach, however, is the fact that in all but six countries the duty rate on 12.5% ABV wine is lower than on 5.0% ABV beer. Finally, while in many countries there are low or, in the case of wine, zero rates of duty for some products, the United Kingdom is unique in having generally high levels of alcohol duty, with the exception of a single product, cider, which is taxed at much lower rates. This disparity is likely to be a key reason why cider consumption is particularly high among heavy and dependent drinkers in the United Kingdom 11, 12, 13.

An important limitation of this study is that we have considered only alcohol duty rates, rather than the on‐the‐shelf prices which are actually faced by consumers. The production and distribution costs associated with different types of alcohol may vary widely, and a truly public health‐orientated tax system should consider these variations. For example, if the production and distribution costs of a unit of alcohol in the form of spirits are vastly less than the equivalent costs for a unit of alcohol as beer, then the prices faced by consumers per unit of alcohol will be also considerably less, all else being equal. This may, in addition to concerns regarding harm potential, be a compelling argument for setting different rates of specific duty on different types of alcohol. We also do not examine how taxation policies interact with, and perhaps justify, other pricing policies. For example, differences in duty structures are likely to impact upon the potential effectiveness of pricing policies such as minimum unit pricing (MUP). MUP imposes a floor price below which a unit of alcohol cannot be sold while having no effect on prices above this level, whereas tax affects the prices of all products. MUP policies may therefore be more effective in countries where some beverages have a lower effective duty rate than others, as with cider in the United Kingdom, than in countries where existing duty structures already impose an effective minimum price in a practical sense, if not a legal one. Understanding the extent to which pricing policies and tax structures interact in this way is an important field for future research.

It is likely that differences in tax rates in EU countries, both across and within beverage types, are influenced by a wide range of contemporary and historical factors. These include the varying levels of production of different beverages within countries, cultural differences in drink preferences, national wealth, political considerations, levels of reliance by government on alcohol tax revenues, wider alcohol policies and the public salience of alcohol problems 14, 15. Perhaps the clearest evidence of such factors informing tax rates is that every EU country that produces significant volumes of wine levies extremely low or zero rates of duty on wine, while almost all non‐wine‐producing countries levy higher rates. The United Kingdom's low tax rate on cider has also been shaped by local production. Interestingly, the same does not appear to be true for beer, with similar rates of beer duty in high‐production countries (e.g. Belgium and the Netherlands) and lower‐production countries (e.g. Italy and France) 16. These discrepancies may be explained to some extent by the fact that local duty is only levied on alcohol purchased within the country and is not, therefore, applied to products exported to other markets.

The analysis presented in this data note has shown that alcohol duty rates and structures within the EU are not currently well aligned with public health goals. On one hand, the considerable scope for countries to set their own duty rates leads to wide varieties in the extent to which alcohol taxes protect public health across Europe. On the other hand, the EU's prohibition of taxing wine and cider by alcoholic strength limits the ability of motivated countries to introduce such public health‐orientated taxes. Addressing these weaknesses is a priority for future EU‐level alcohol policy.

Declaration of interests

C. A., J. H. and P. M. have received funding for unrelated, commissioned research from Systembolaget and Alko, the Swedish and Finnish government‐owned alcohol retail monopolies.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Alcohol tax structure graphs for every EU Member State

Figure S2 PPP‐adjusted alcohol duty rates in 28 EU Member States

Figure S3 Map of PPP‐adjusted duty rates for selected products

Angus, C. , Holmes, J. , and Meier, P. S. (2019) Comparing alcohol taxation throughout the European Union. Addiction, 114: 1489–1494. 10.1111/add.14631.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO) . Scaling Up Action Against Noncommunicable Diseases: How Much Will It Cost? Geneva: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sornpaisarn B., Shield K. D., Osterberg E., Rehm J. Resource Tool on Alcohol Taxation and Pricing Policies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meier P. S., Holmes J., Angus C., Ally A. K., Meng Y., Brennan A. Estimated effects of different alcohol taxation and price policies on health inequalities: a mathematical modelling study. PLOS Med 2016; 13: e1001963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. European Commission . Harmonization of the Structures of Excise Duties on Alcohol and Alcoholic Beverages. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5. European Commission . Approximation of the Rates of Excise Duty on Alcohol and Alcoholic Beverages. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 6. European Commission . Excise Duty Tables: Part 1—Alcoholic Beverages. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7. The World Bank . PPP conversion factor [internet]. International Comparison Program database. 2018. [cited 2018 Dec 10]. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PA.NUS.PPP (accessed April 24, 2019) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/77sAYzGsa).

- 8. THL . Passenger Quotation for Alcoholic Beverages. (September 2017–August 2018) [internet]. Statistical Report 35/2018. 2018. [cited 2018 Dec 10]. Available from: https://thl.fi/fi/tilastot‐ja‐data/tilastot‐aiheittain/paihteet‐ja‐riippuvuudet/alkoholi/alkoholijuomien‐matkustajatuonti (accessed April 24, 2019) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/77sB0omFe).

- 9. THL . Alcoholic beverage consumption 2017 [internet]. Statistical report 10/2018. 2018. [cited 2018 Dec 10]. Available from: https://thl.fi/en/web/thlfi‐en/statistics/statistics‐by‐topic/alcohol‐drugs‐and‐addiction/alcohol/alcoholic‐beverage‐consumption (accessed April 24, 2019) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/77sBBOPu2).

- 10. HM Treasury . Review of Alcohol Taxation. London: HM Treasury; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Black H., Gill J., Chick J. The price of a drink: levels of consumption and price paid per unit of alcohol by Edinburgh's ill drinkers with a comparison to wider alcohol sales in Scotland. Addiction 2011; 106: 729–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holmes J., Meng Y., Meier P. S., Brennan A., Angus C., Campbell‐Burton A., et al Effects of minimum unit pricing for alcohol on different income and socioeconomic groups: a modelling study. Lancet 2014; 383: 1655–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sheron N., Chilcott F., Matthews L., Challoner B., Thomas M. Impact of minimum price per unit of alcohol on patients with liver disease in the UK. Clin Med 2014; 14: 396–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nicholls J. The Politics of Alcohol: A History of the Drink Question in England. Manchester: Manchester University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Room R., Mäkelä K. Typologies of the cultural position of drinking. J Stud Alcohol 2000; 61: 475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anderson K, Pinilla V. Annual Database of Global Wine Markets, 1835 to 2016. Working Paper no. 0417. Adelaide, Australia: University of Adelaide; 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Alcohol tax structure graphs for every EU Member State

Figure S2 PPP‐adjusted alcohol duty rates in 28 EU Member States

Figure S3 Map of PPP‐adjusted duty rates for selected products