Abstract

A continuous‐flow, visible‐light‐promoted method has been developed to overcome the limitations of iron‐catalyzed Kumada–Corriu cross‐coupling reactions. A variety of strongly electron rich aryl chlorides, previously hardly reactive, could be efficiently coupled with aliphatic Grignard reagents at room temperature in high yields and within a few minutes’ residence time, considerably enhancing the applicability of this iron‐catalyzed reaction. The robustness of this protocol was demonstrated on a multigram scale, thus providing the potential for future pharmaceutical application.

Keywords: cross-coupling, flow chemistry, iron catalysis, Kumada coupling, photocatalysis

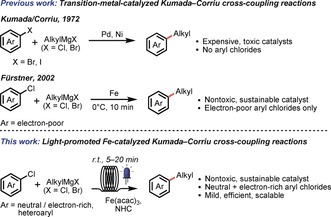

Over the past three decades, transition‐metal‐catalyzed cross‐coupling reactions have emerged as one of the most important classes of C−C bond‐forming reactions.1 One of the oldest and most important transformations is the coupling of aryl halides with Grignard reagents. This chemistry has been extensively studied using Pd2 and Ni3 catalysis since its first discovery by Kumada and Corriu in 1972.4 Despite the efficiency of these reactions, these metals are toxic and expensive, and more and more research has been devoted to the development of efficient catalytic methods using cheap, earth‐abundant, and nontoxic alternative catalysts.5 In this regard, iron catalysis has been extensively investigated.6, 7 In 2002, based on pioneering studies by, among others, Kharasch,8 Kochi,9 and Cahiez,10 Fürstner and co‐workers developed the first efficient iron‐catalyzed Kumada–Corriu coupling between aryl chlorides and alkyl Grignard reagents.11 Key to this advancement was the use of N‐methyl‐2‐pyrrolidone (NMP) as a cosolvent in the reaction. This method provided a very attractive alternative to the palladium/nickel‐catalyzed reaction, as aryl chlorides could be more efficiently employed as starting materials instead of aryl bromides and iodides (Scheme 1).12 Nonetheless, this and subsequent protocols13 are limited to electron‐deficient aryl chlorides, triflates, and tosylates, and to primary aliphatic Grignard reagents. Electron‐neutral (e.g. chlorobenzene) and electron‐rich aryl chlorides could only later be successfully employed in the reaction when N‐heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligands were used, but still required high temperatures and/or long reaction times.14 Despite further notable advancements in the field of iron‐catalyzed cross‐coupling reactions,15 to date the coupling of electron‐rich aryl chlorides with aliphatic Grignard reagents remains challenging, and the number of reports is still considerably limited.

Scheme 1.

C(sp2)−C(sp3) bond formation through Kumada–Corriu cross‐coupling reactions.

Recently, Alcázar and co‐workers developed visible‐light‐promoted palladium/nickel‐catalyzed Negishi cross‐coupling reactions, demonstrating the advantage of irradiation on this type of cross‐coupling reaction.16 Inspired by these results, and following our continuous interest in metal‐catalyzed coupling reactions in flow,17 we report herein a light‐promoted iron‐catalyzed Kumada–Corriu coupling for C(sp2)−C(sp3) bond formation in continuous flow.18 Considering the present limitations on the scope of aryl chloride reaction partners typical for this reaction, this method allows broadening of the substrate scope under very mild and scalable conditions.

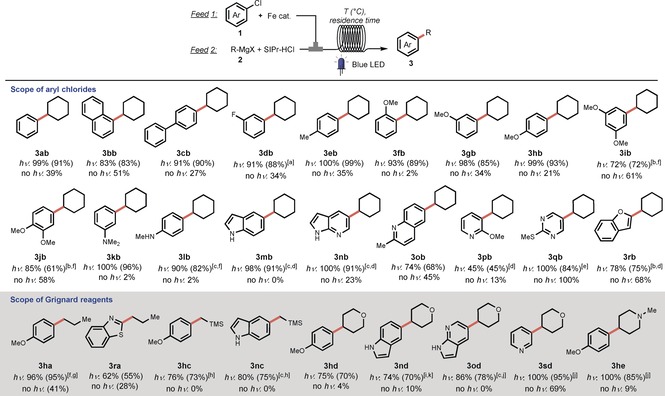

At the beginning of our study, we treated model substrates chlorobenzene (1 a) and n‐propylmagnesium bromide (2 a) with FeCl2⋅4 H2O (1 mol %) and 3‐bis(2,6‐diisopropylphenyl)imidazolinium chloride (SIPr⋅HCl; 2 mol %) as the ligand under irradiation with blue LEDs (450 nm) at 20 °C. To our delight, n‐propylbenzene (3 aa) was obtained in 76 % yield using a residence time of 20 min, whereas the reaction without light only furnished 3 aa in 5 % yield (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). This result shows that visible light indeed significantly accelerates the Kumada cross‐coupling. At 25 °C, the reaction proceeded more efficiently, giving 84 % yield (entry 3). Different iron halides, such as FeF3 and FeCl3, gave moderate to good yields, while the use of Fe(acac)3 (acac=acetylacetonate) resulted in an excellent 89 % yield of 3 aa (entries 4–6). Increasing the catalyst loading (2 mol %) and concentration resulted in 98 % yield within a residence time of only 15 min (entry 7). Control experiments in the absence of Fe or NHC gave no product, while the reaction in the dark under these conditions produced 3 aa in only 11 % yield (entries 8–10). Interestingly, when cyclohexylmagnesium chloride (CyMgCl, 2 b) was employed in the reaction, full conversion was observed within only 5 min residence time (entry 11). This reagent was thus selected for further studies.

Table 1.

Optimization of the reaction conditions.[a]

| Entry | Catalyst | R | t [min][b] | Yield [%][c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1[d,e] | FeCl2⋅4 H2O | n‐propyl (2 a) | 20 | 76 (3 aa) |

| 2[d–f] | FeCl2⋅4 H2O | n‐propyl (2 a) | 20 | 5 (3 aa) |

| 3[d] | FeCl2⋅4 H2O | n‐propyl (2 a) | 20 | 84 (3 aa) |

| 4[d] | FeF3 | n‐propyl (2 a) | 20 | 45 (3 aa) |

| 5[d] | FeCl3 | n‐propyl (2 a) | 20 | 73 (3 aa) |

| 6[d] | Fe(acac)3 | n‐propyl (2 a) | 20 | 89 (3 aa) |

| 7 | Fe(acac)3 | n‐propyl (2 a) | 15 | 98 (3 aa) |

| 8 | – | n‐propyl (2 a) | 15 | 0 (3 aa) |

| 9[g] | Fe(acac)3 | n‐propyl (2 a) | 15 | 0 (3 aa) |

| 10[f] | Fe(acac)3 | n‐propyl (2 a) | 15 | 11 (3 aa) |

| 11 | Fe(acac)3 | cyclohexyl (2 b) | 5 | 96 (3 ab) |

[a] Reaction conditions: Feed 1: chlorobenzene (1 a; 2 mmol), Fe(acac)3 (0.04 mmol), THF (5 mL); feed 2: Grignard reagent (3 mmol), SIPr⋅HCl (0.08 mmol), THF, 25 °C, 24 W blue LEDs. [b] Residence time. [c] The yield was determined by GC. [d] Fe(acac)3 (0.02 mmol), SIPr⋅HCl (0.04 mmol), [e] T=20 °C. [f] No light. [g] No ligand.

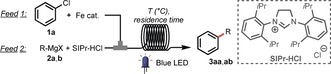

Having established optimal reaction conditions, we investigated the scope of this transformation (Scheme 2). Unfunctionalized aryl chlorides in the coupling with Grignard 2 b already show large differences in yields between irradiation and non‐irradiation conditions (3 ab–3 cb, 83–91 vs. 27–51 %). Substrates containing a fluorine or methyl moiety also reacted smoothly, giving 3 db and 3 eb in 88 and 99 % yield under irradiation. Furthermore, functionalization with one or two strongly electron donating methoxy groups, including at very challenging ortho positions, also resulted in high isolated yields of compounds 3 fb–3 jb (61–93 %). For compounds 3 ib and 3 jb, 5 mol % Fe(acac)3 and 10 mol % NHC were required for full conversion within a residence time of 20 min. The strongly electron donating groups NMe2 and NHMe were also tolerated in the reaction and furnished 3 kb and 3 lb in high yields (82–96 %). The presence of a free NH moiety in 3 lb is particularly noteworthy, as the reaction avoids the introduction of protecting groups. Unprotected NH functionalities in medicinally relevant7c indoles and pyrrolopyridines were also tolerated (3 mb, 3 nb, 91 %). Other functionalized heterocyclic chlorides, such as 2‐methylquinoline, 2‐methoxypyridine, 2‐methylthiopyrimidine, and benzofuran chlorides reacted with 2 b in modest to good yields (3 ob–3 rb, 45–84 %).

Scheme 2.

Scope of the reaction the reaction with respect to the aryl chloride: Feed 1: 1 (2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), Fe(acac)3 (0.04 mmol), THF 5 mL; feed 2: 2 b (1.5 equiv), SIPr⋅HCl (0.08 mmol); 25 °C, residence time: 5 min, 24 W blue LEDs. Yields were determined by GC/LC; yields for the isolated products are reported in brackets. [a] Residence time: 2 min. [b] Fe(acac)3: 5 mol %, SIPr⋅HCl: 10 mol %. [c] Grignard reagent: 2.5 equivalents. [d] Residence time: 15 min. [e] Residence time: 1 min. [f] Residence time: 20 min. Scope of the reaction with respect to the Grignard reagent: Feed 1: 1 (2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), Fe(acac)3 (5 mol %); feed 2: 2 (1.5 equiv), SIPr⋅HCl (15 mol %), 25 °C, residence time: 20 min. [g] Fe(acac)3: 2 mol %, SIPr⋅HCl: 4 mol %. [h] [h] Fe(acac)3: 10 mol %, SIPr⋅HCl: 30 mol %, in batch with 34 W blue LED irradiation at 45 °C for 4 h. [i] 40 °C. [j] iPrMgBr (0.3 equiv) was added to feed 2. [k] Substrate 2 d: 2.0 equivalents.

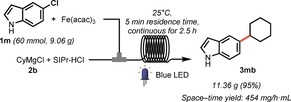

Next, we studied the reactivity of different Grignard reagents. A few generally less reactive alkyl Grignard reagents, such as n‐propylmagnesium and (trimethylsily)methylmagnesium chlorides,19 were successfully employed in the coupling with electron‐rich or heterocyclic aryl chlorides, affording the coupling products 3 ha, 3 ra, 3 hc, and 3 nc in good isolated yields (55–95 %). Encouraged by these results, some new Grignard reagents decorated with medicinally important moieties, such as tetrahydropyran and N‐methylpiperidine,20 were prepared21 and tested in the reaction. Compounds 3 hd, 3 nd, 3 od, 3 sd, and 3 he, featuring electron‐rich or heteroaromatic moieties, were obtained under mild reaction conditions in 70–95 % yield.22 As expected, most of these compounds were only obtained in trace amounts in the absence of light. Finally, the scalability of this protocol was demonstrated in a multigram scale synthesis of unprotected indole 3 mb (Scheme 3). With a residence time of only 5 min, after running continuously for 2.5 h, 11.36 g of 3 mb were isolated (95 %), with the space–time yield reaching 454 mg h−1 mL−1.

Scheme 3.

Reaction scale‐up. Feed 1: 1 m (9.06 g, 60 mmol), Fe(acac)3 (423.6 mg, 2 mol %), THF (150 mL); feed 2: 2 b (150 mL, 1.0 m in THF, 2.5 equiv), SIPr⋅HCl, (1.02 g, 4 mol %); 25 °C, residence time: 5 min.

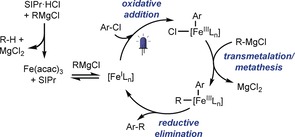

Despite the recent interest in iron‐catalyzed cross‐coupling reactions, the elucidation of their mechanism is not straightforward.23 The current mechanistic understanding of iron‐catalyzed Kumada coupling using β‐hydrogen‐containing Grignard reagents24 supports an initial reduction of FeIII to a lower‐oxidation‐state species [Fered] by the Grignard reagent, leading to FeXn or Fe(MgX)n intermediates. Different oxidation states for [Fered] have been suggested, ranging from Fe−II to FeI.15d, 24, 25 This initial necessary step is followed by the rate‐determining oxidative addition of the aryl chloride, and transmetalation with further Grignard reagent, or vice versa. The final reductive elimination is suggested to be fast and restore the [Fered] species.11b, 25

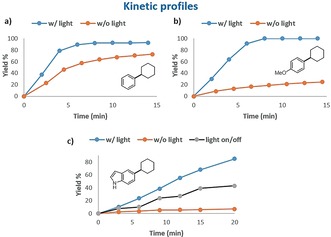

We performed some experiments to understand the effect of irradiation in this reaction. Kinetic profiles for the coupling of chlorobenzene (1 a) and p‐chloroanisole (1 h) with CyMgCl (2 b) with and without irradiation showed a clear beneficial effect of light on the rate of the reaction. In particular, the effect of irradiation is much more pronounced for the coupling of electron‐rich 1 h than for chlorobenzene 1 a (Figure 1 a,b). This result might suggest an effect of light in facilitating the oxidative addition, although other effects cannot as yet be excluded. A strong effect of light was also observed for the coupling with chloroindole 1 m, which resulted in almost no reaction in the absence of light. Light on/off experiments on this reaction showed that light is needed during the whole process (Figure 1 c), so its role in the mere generation of an active catalytic species (off‐cycle) can be excluded.

Figure 1.

a,b) Batch reaction profiles for the coupling of CyMgCl (2 b) with chlorobenzene (1 a) and p‐chloroanisole (1 h) with or without blue‐light irradiation. c) Reaction profiles for the coupling of 2 b with chloroindole 1 m with or without light, and in a light on/off experiment.

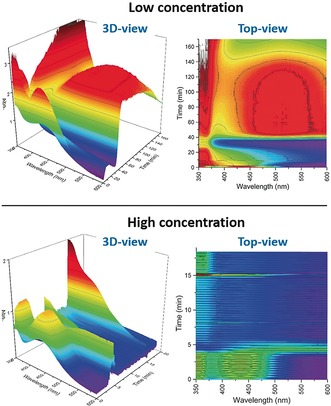

In‐line UV/Vis analysis of the reaction between CyMgCl (2 b) and chloroindole 1 m (under irradiation) was performed at low concentration (0.01 m) to study the first step of the reaction (Figure 2, top). Upon addition of 2 b and 1 m to a solution of Fe/NHC in THF, the characteristic absorption band of Fe(acac)3 (ca. 450 nm) immediately disappeared, and a broad, stable band in the visible range (450–600 nm) appeared after approximately 30 min. This band remained almost unchanged for the following 100 min. Similar results were obtained without irradiation (see the Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

In‐line UV/Vis analysis of the reaction between CyMgCl (2 b) and chloroindole 1 m. Top: 0.01 m in THF; bottom: 0.1 m.

The same experiment under more concentrated conditions (0.1 m, Figure 2, bottom) also showed the disappearance of Fe(acac)3 and the formation of the large band at 450–600 nm upon addition of the Grignard reagent and chloroindole. Under such conditions, this band appeared and disappeared quickly, and a new weak band at approximately 450 nm briefly appeared after a short time. After turning the light on, the same band appeared with a much higher intensity (see the Supporting Information for more details). Full conversion was observed within several minutes from this event.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations (see the Supporting Information) suggest the broad band at 450–600 nm might be related to a FeI species, and that at 450 nm to a FeIII species. Therefore, we propose a catalytic cycle in which an FeI intermediate is formed upon reduction of the precatalyst by the Grignard reagent at the beginning of the reaction, followed by slow oxidative addition to give a FeIII species (Scheme 4). The higher intensity of the sudden peak at 450 nm upon irradiation suggests an effect of light in promoting an aerobic oxidation process (or analogous) yielding the FeIII species. This hypothesis is in agreement with the kinetic measurements shown in Figure 1. As almost no difference was observed in the dark and light experiments at low concentration, it seems the initial formation of the reduced FeI species (off‐cycle process) is not particularly influenced by light, which is instead essential during the real catalytic process (Figure 1 c).

Scheme 4.

Proposed mechanism.

In conclusion, we have reported a scalable, visible‐light‐accelerated coupling of unactivated and electron‐rich aryl chlorides with alkylmagnesium compounds in continuous‐flow conditions. The use of blue light was demonstrated to considerably accelerate the coupling reaction, and allowed the use of mild conditions and very short reaction times even for previously very stubborn substrates, and provides a competitive alternative to commonly used Pd or Ni catalysts for this transformation. Preliminary mechanistic studies suggested an FeI/FeIII catalytic cycle.26 Further mechanistic studies are being undertaken in our laboratory.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

X.‐J.W., I.A., J.A., and T.N. acknowledge the European Union for a Marie Curie ITN Grant (Photo4Future, Grant No. 641861). C.S. acknowledges the European Union for a Marie Curie European post‐doctoral fellowship (FlowAct, Grant No. 794072). We thank the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council for financial support (EP/M02105X/1). C.L. is grateful for a Prof. and Mrs Purdie Bequests Scholarship and to AstraZeneca for his PhD Studentship. Finally, we thank Dr. J. P. Hofmann for useful discussions.

X.-J. Wei, I. Abdiaj, C. Sambiagio, C. Li, E. Zysman-Colman, J. Alcázar, T. Noël, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 13030.

Contributor Information

Xiao‐Jing Wei, http://www.noelresearchgroup.com.

Dr. Jesús Alcázar, Email: jalcazar@its.jnj.com.

Dr. Timothy Noël, Email: t.noel@tue.nl.

References

- 1. Busch M., Wodrich M. D., Corminboeuf C., ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 5643–5653. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johansson Seechurn C. C. C., Kitching M. O., Colacot T. J., Snieckus V., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5062–5085; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 5150–5174. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tasker S. Z., Standley E. A., Jamison T. F., Nature 2014, 509, 299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Corriu R. J. P., Masse J. P., J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1972, 144a–144a; [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Tamao K., Sumitani K., Kumada M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 4374–4376. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hockin B. M., Li C., Robertson N., Zysman-Colman E., Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 889–915. [Google Scholar]

- 6.For general reviews on iron catalysis, see:

- 6a. Gopalaiah K., Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 3248–3296; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Jia F., Li Z., Org. Chem. Front. 2014, 1, 194–214; [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Bauer I., Knölker H.-J., Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 3170–3387; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6d. Fürstner A., ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2, 778–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.For reviews on iron-catalyzed cross-coupling, see:

- 7a. Kuzmina O. M., Steib A. K., Moyeux A., Cahiez G., Knochel P., Synthesis 2015, 47, 1696–1705; [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Guérinot A., Cossy J., Top. Curr. Chem. 2016, 374, 49; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7c. Piontek A., Bisz E., Szostak M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 11116–11128; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 11284–11297. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kharasch M. S., Tawney P. O., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1941, 63, 2308–2316. [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Kwan C. L., Kochi J. K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 4903–4912; [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Smith R. S., Kochi J. K., J. Org. Chem. 1976, 41, 502–509; [Google Scholar]

- 9c. Tamura M., Kochi J. K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 1487–1489. [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Cahiez G., Avedissian H., Synthesis 1998, 1199–1205; [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Dohle W., Kopp F., Cahiez G., Knochel P., Synlett 2001, 1901–1904. [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a. Fürstner A., Leitner A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 609–612; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2002, 114, 632–635; [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Fürstner A., Leitner A., Méndez M., Krause H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 13856–13863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pd-catalyzed Kumada couplings with aryl chlorides are typically limited: Tatsuo K., Masayuki U., Chem. Lett. 1991, 20, 2073–2076. [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Rushworth P. J., Hulcoop D. G., Fox D. J., J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 9517–9521; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Cahiez G., Lefèvre G., Moyeux A., Guerret O., Gayon E., Guillonneau L., Lefèvre N., Gu Q., Zhou E., Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 2679–2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a. Perry M. C., Gillett A. N., Law T. C., Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 4436–4439; [Google Scholar]

- 14b. Agata R., Iwamoto T., Nakagawa N., Isozaki K., Hatakeyama T., Takaya H., Nakamura M., Synthesis 2015, 47, 1733–1740; [Google Scholar]

- 14c. Agata R., Takaya H., Matsuda H., Nakatani N., Takeuchi K., Iwamoto T., Hatakeyama T., Nakamura M., Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 92, 381–390. [Google Scholar]

- 15.

- 15a. O'Brien H. M., Manzotti M., Abrams R. D., Elorriaga D., Sparkes H. A., Davis S. A., Bedford R. B., Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 429–437; [Google Scholar]

- 15b. Jin M., Adak L., Nakamura M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 7128–7134; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15c. Bedford R. B., Carter E., Cogswell P. M., Gower N. J., Haddow M. F., Harvey J. N., Murphy D. M., Neeve E. C., Nunn J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 1285–1288; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 1323–1326; [Google Scholar]

- 15d. Guisán-Ceinos M., Tato F., Buñuel E., Calle P., Cárdenas D. J., Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 1098–1104; [Google Scholar]

- 15e. Adams C. J., Bedford R. B., Carter E., Gower N. J., Haddow M. F., Harvey J. N., Huwe M., Cartes M. Á., Mansell S. M., Mendoza C., Murphy D. M., Neeve E. C., Nunn J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 10333–10336; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15f. Hatakeyama T., Okada Y., Yoshimoto Y., Nakamura M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 10973–10976; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 11165–11168; [Google Scholar]

- 15g. Hatakeyama T., Hashimoto T., Kondo Y., Fujiwara Y., Seike H., Takaya H., Tamada Y., Ono T., Nakamura M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10674–10676; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15h. Hatakeyama T., Hashimoto S., Ishizuka K., Nakamura M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 11949–11963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a. Abdiaj I., Fontana A., Gomez M. V., de la Hoz A., Alcázar J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 8473–8477; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 8609–8613; [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Abdiaj I., Huck L., Mateo J. M., de la Hoz A., Gomez M. V., Díaz-Ortiz A., Alcázar J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 13231–13236; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 13415–13420. [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Casnati A., Gemoets H. P. L., Motti E., Della Ca’ N., Noël T., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 14079–14083; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Gemoets H. P. L., Laudadio G., Verstraete K., Hessel V., Noël T., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7161–7165; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 7267–7271; [Google Scholar]

- 17c. Sharma U. K., Gemoets H. P. L., Schröder F., Noël T., Van der Eycken E. V., ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 3818–3823; [Google Scholar]

- 17d. Gemoets H. P. L., Hessel V., Noël T., Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 5800–5803; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17e. Noël T., Kuhn S., Musacchio A. J., Jensen K. F., Buchwald S. L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 5943–5946; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 6065–6068; [Google Scholar]

- 17f. Noël T., Naber J. R., Hartman R. L., McMullen J. P., Jensen K. F., Buchwald S. L., Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 287–290. [Google Scholar]

- 18.For reviews on cross-coupling reactions in flow, see:

- 18a. Noël T., Buchwald S. L., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 5010–5029; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18b. Cantillo D., Kappe C. O., ChemCatChem 2014, 6, 3286–3305. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The (trimethylsilyl)methyl group was shown not to be reactive in iron-catalyzed Negishi coupling reactions:

- 19a. Nakamura M., Ito S., Matsuo K., Nakamura E., Synlett 2005, 1794–1798; [Google Scholar]

- 19b. Bedford R. B., Huwe M., Wilkinson M. C., Chem. Commun. 2009, 600–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.For recent examples, see:

- 20a. Campbell P. S., Jamieson C., Simpson I., Watson A. J. B., Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 46–49; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20b. Mayol-Llinàs J., Farnaby W., Nelson A., Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 12345–12348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huck L., de la Hoz A., Díaz-Ortiz A., Alcázar J., Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 3747–3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.For compounds 3 od, 3 sd, and 3 he, the addition of iPrMgBr (0.3 equiv) at the beginning of the reaction was found to be beneficial. We believe iPrMgBr acts as a base to deprotonate the NHC precursor.

- 23.For reviews on the mechanisms of iron-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, see:

- 23a. Cassani C., Bergonzini G., Wallentin C.-J., ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 1640–1648; [Google Scholar]

- 23b. Parchomyk T., Koszinowski K., Synthesis 2017, 49, 3269–3280; [Google Scholar]

- 23c. Sears J. D., Neate P. G. N., Neidig M. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 11872–11883; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23d. Bedford R. B., Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1485–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reactions with Grignard reagents without β-hydrogen atoms might have different outcomes; see: Fürstner A., Martin R., Krause H., Seidel G., Goddard R., Lehmann C. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 8773–8787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.

- 25a. Kleimark J., Hedström A., Larsson P.-F., Johansson C., Norrby P.-O., ChemCatChem 2009, 1, 152–161; [Google Scholar]

- 25b. Kleimark J., Larsson P.-F., Emamy P., Hedström A., Norrby P.-O., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 448–456. [Google Scholar]

- 26.As the spectroscopic studies could not be accurately performed under the typical reaction conditions, and no well-defined Fe species were employed for such investigations (reaction components were treated in situ with the catalyst precursor), the proposed catalytic cycle is not certain. Under such conditions, a variety of Fe species might be present in solution with different coordination, ligand environment, and/or oxidation state, most likely very dynamic under the reaction conditions. Different mechanistic pathways might also be possible, such as the excitation of a Fe species, which then acts as a photoredox catalyst; see: Kancherla R., Muralirajan K., Sagadevan A., Rueping M., Trends Chem. 2019, 10.1016/j.trechm.2019.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary